Submitted:

28 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell line and culture conditions

2.2. Rod OS isolation

2.3. Oxygen consumption rate evaluation

2.4. Aerobic ATP synthesis evaluation

2.5. Evaluation of lipofuscin accumulation in ARPE-19 cells by confocal microscopy

2.6. Lipoperoxidation evaluation

2.7. Antioxidants enzymes activity evaluation

2.8. Western Blot analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

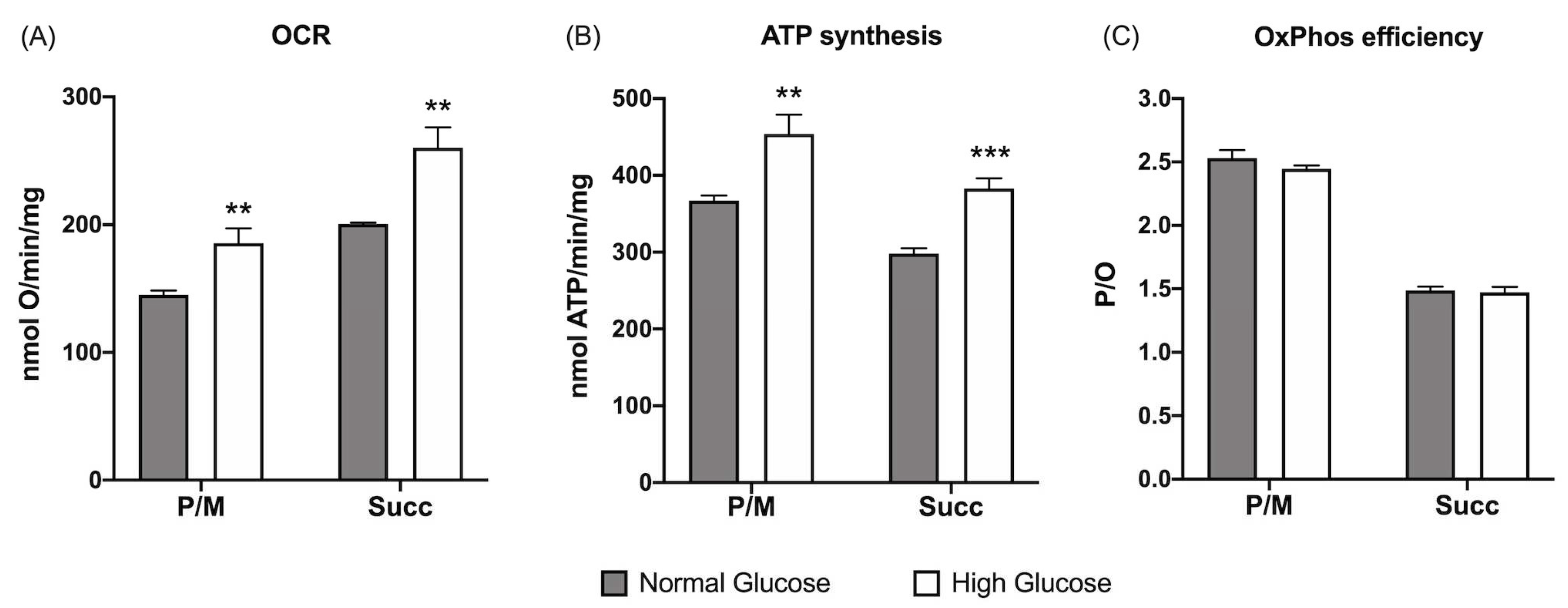

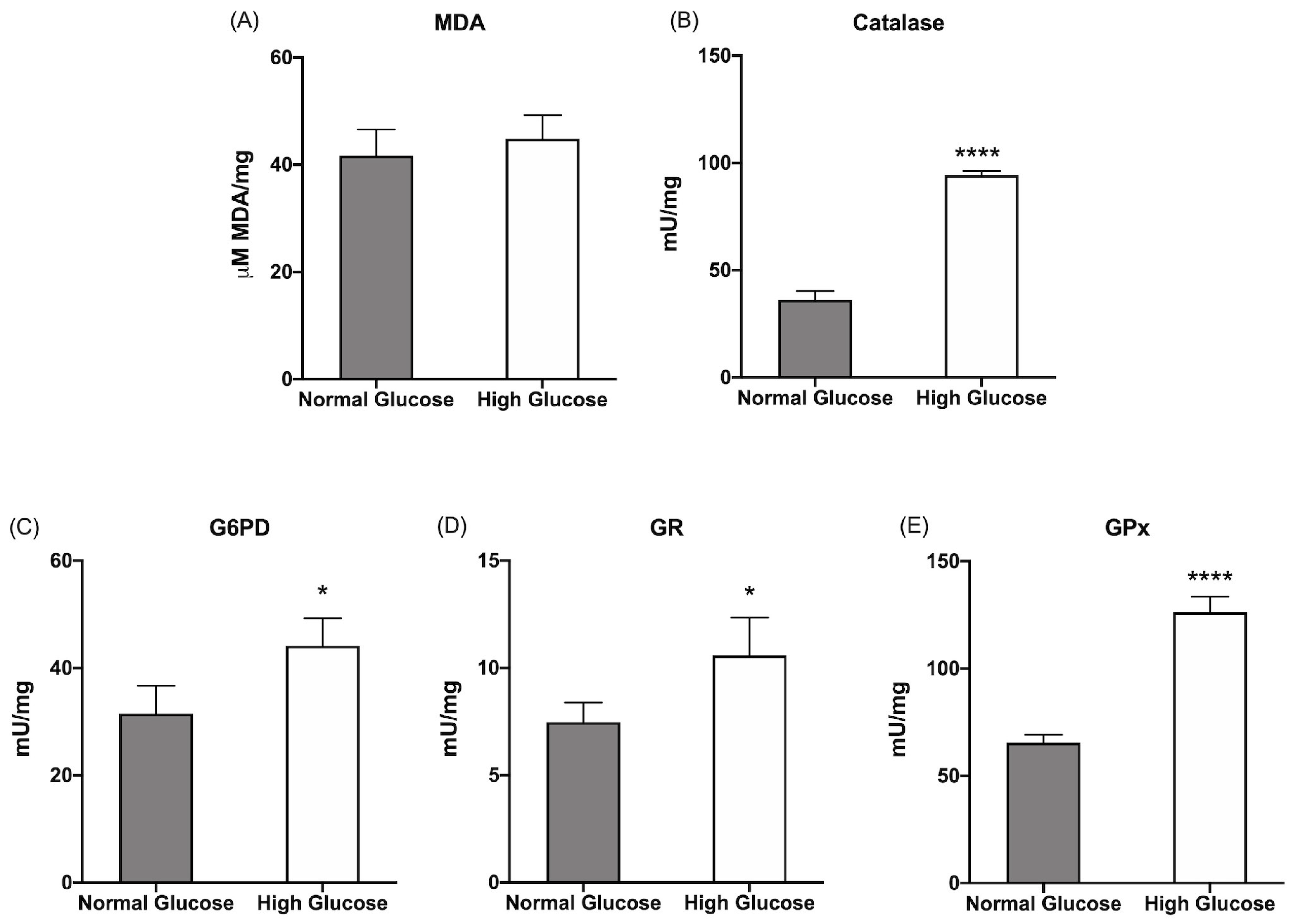

3.1. ARPE-19 cells increase the aerobic energy metabolism proportionally to glucose concentration without causing an increase in oxidative damage due to the activation of endogenous antioxidant defenses.

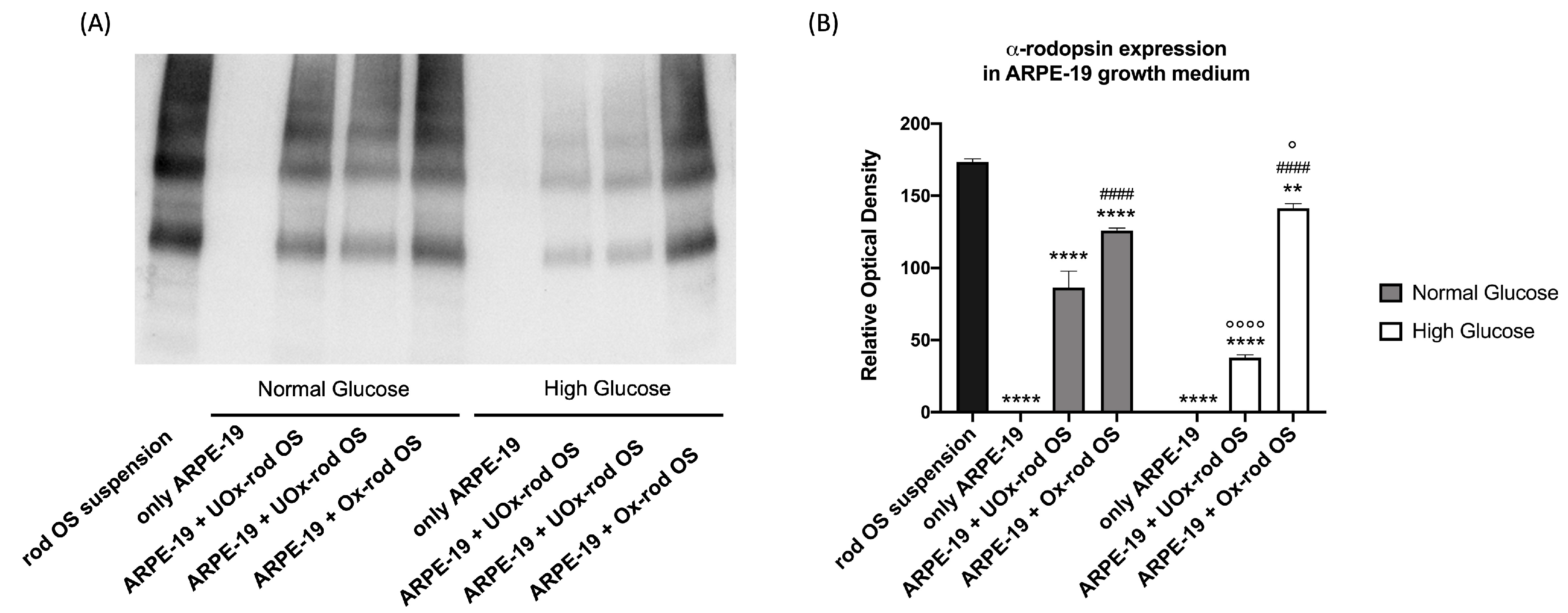

3.2. The phagocytizing capacity of ARPE-19 cells depends on the glucose concentration in the medium and the rod outer-segments oxidative state.

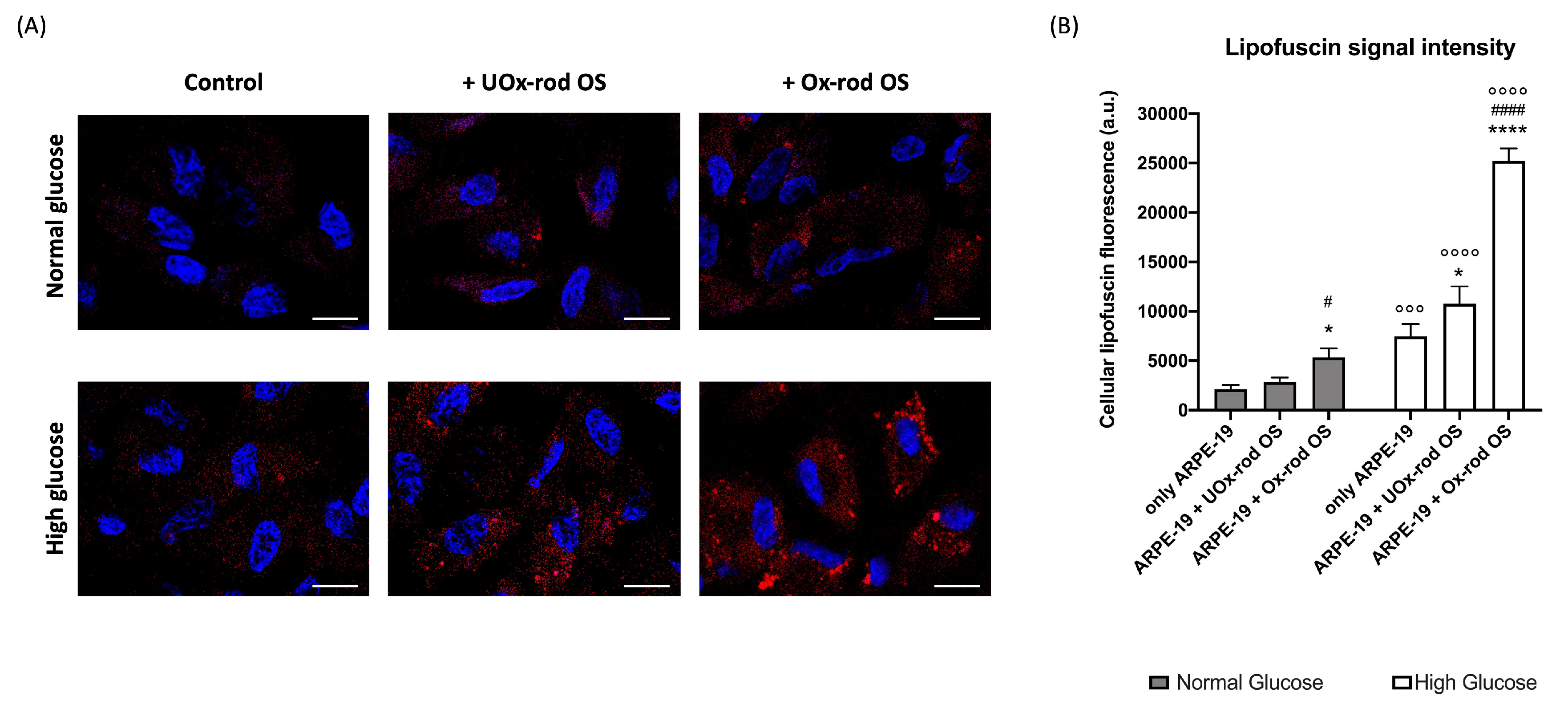

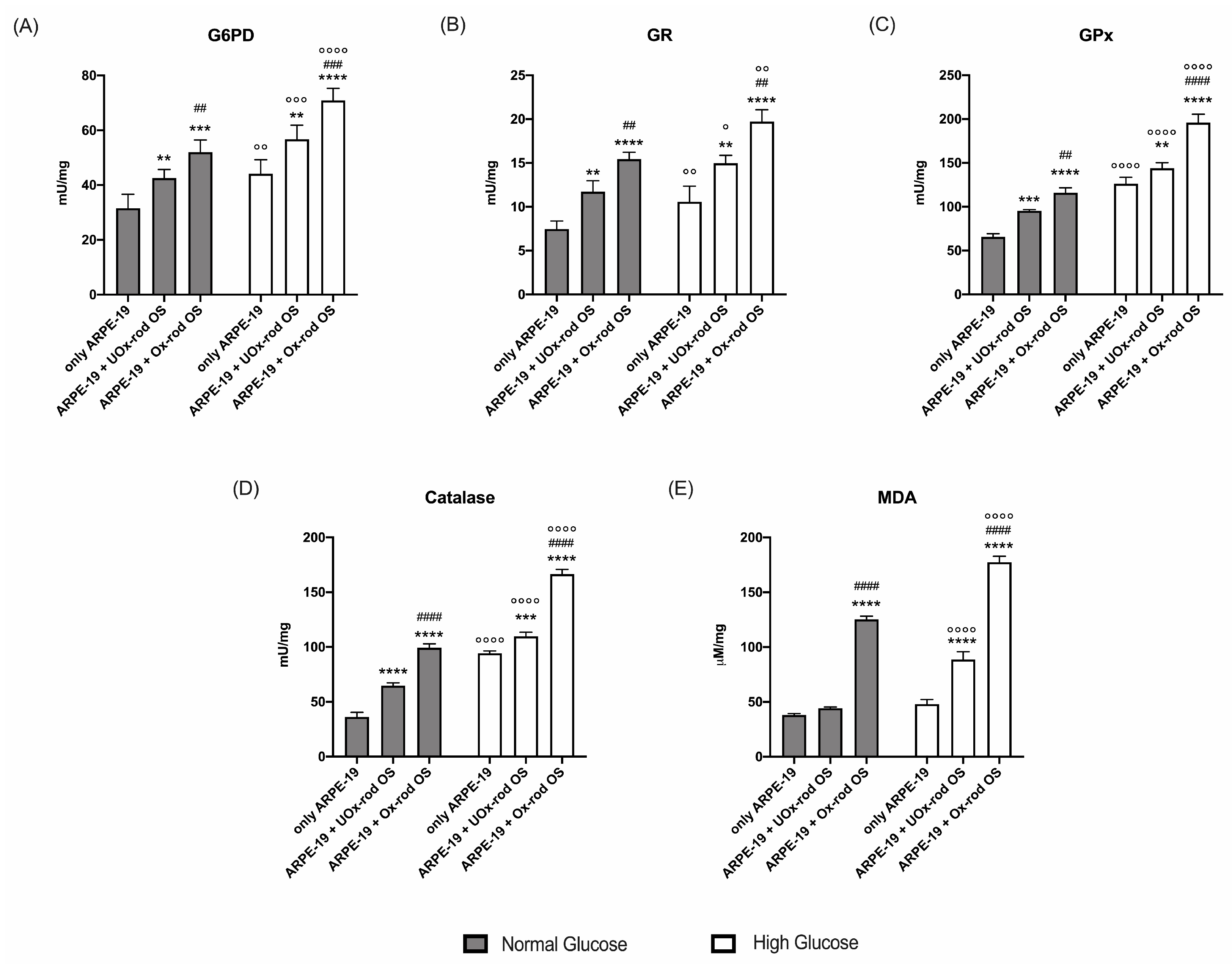

3.3. The altered ARPE-19 cells phagocytosis capacity depends on the accumulation of oxidative stress.

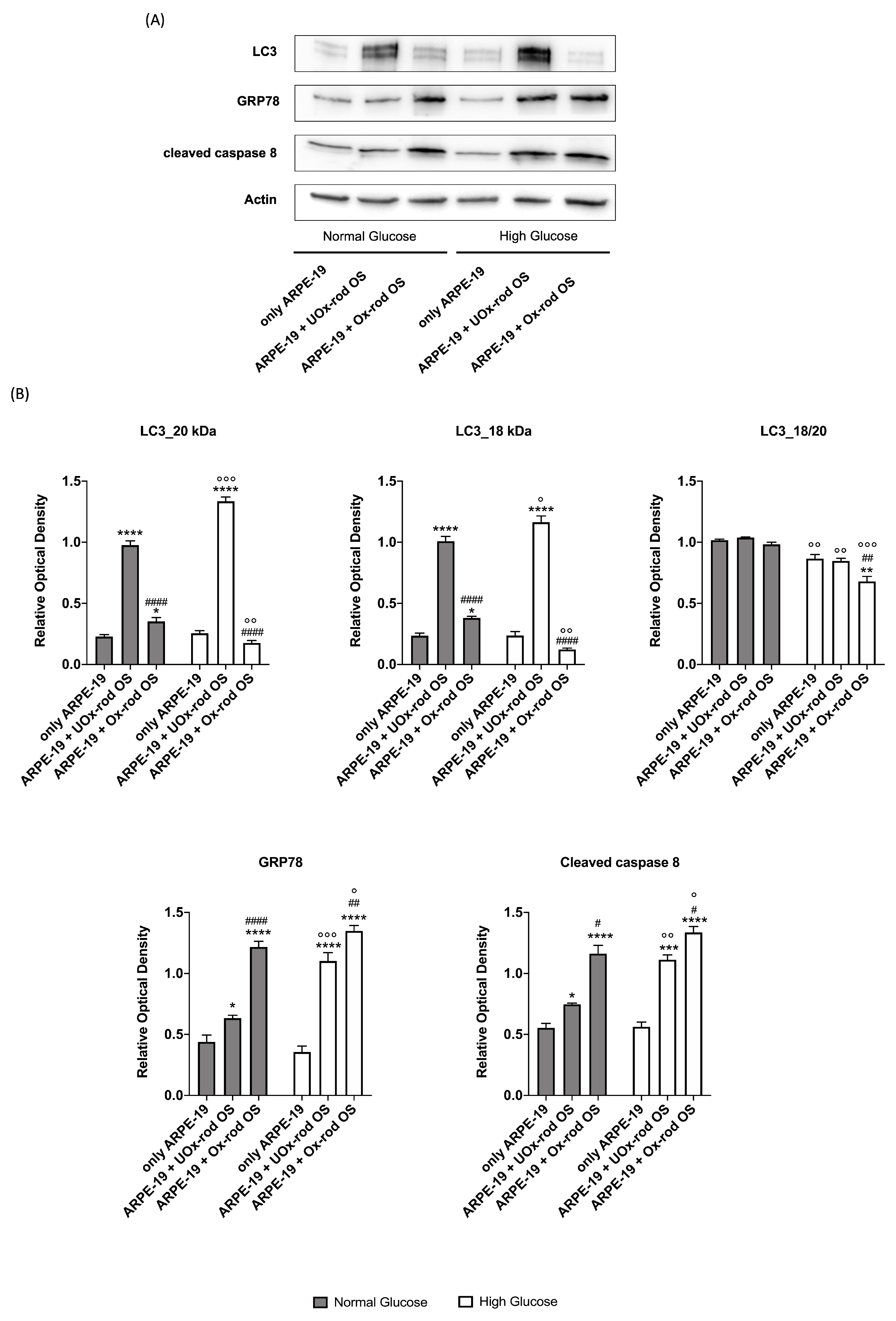

3.4. The accumulation of oxidative stress due to phagocytosis of Ox-rod OS causes an increase in the expression of markers of the unfolding protein response and pro-apoptotic signal and reduces the autophagy process.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caceres, P.S.; Rodriguez-Boulan, E. Retinal Pigment Epithelium Polarity in Health and Blinding Diseases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2020, 62, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lo, A.C.Y. Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiology and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q, K.; C, Y. Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Retinopathy: Molecular Mechanisms, Pathogenetic Role and Therapeutic Implications. Redox Biol 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.X.; Stiles, T.; Douglas, C.; Ho, D.; Fan, W.; Du, H.; Xiao, X. Oxidative Stress, Innate Immunity, and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. AIMS Mol Sci 2016, 3, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutto, I.; Lutty, G. Understanding Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): Relationships between the Photoreceptor/Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Bruch’s Membrane/Choriocapillaris Complex. Mol Aspects Med 2012, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, E.P.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Sapieha, P.; Smith, L.H.; Ma, J.X. Neurovascular Cross Talk in Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiological Roles and Therapeutic Implications. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016, 311, H738–H749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, O. The Retinal Pigment Epithelium in Visual Function. Physiol Rev 2005, 85, 845–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, C.A. Photoreceptor Topography in Ageing and Age-Related Maculopathy. Eye (Lond) 2001, 15, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.D.; Curtin, J. Photoreceptor Physiology and Evolution: Cellular and Molecular Basis of Rod and Cone Phototransduction. J Physiol 2022, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Chuang, J.Z.; Sung, C.H. Light Regulates the Ciliary Protein Transport and Outer Segment Disc Renewal of Mammalian Photoreceptors. Dev Cell 2015, 32, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, B.S. An Hypothesis to Account for the Renewal of Outer Segments in Rod and Cone Photoreceptor Cells: Renewal as a Surrogate Antioxidant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008, 49, 3259–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, A.L.; Parinot, C.; Chatagnon, J.; Gravez, B.; Sahel, J.A.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Nandrot, E.F. Cleavage of Mer Tyrosine Kinase (MerTK) from the Cell Surface Contributes to the Regulation of Retinal Phagocytosis. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 4941–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandrot, E.F.; Silva, K.E.; Scelfo, C.; Finnemann, S.C. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Use a MerTK-Dependent Mechanism to Limit the Phagocytic Particle Binding Activity of Avβ5 Integrin. Biology of the cell / under the auspices of the European Cell Biology Organization 2012, 104, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddu, A.; Ravera, S.; Panfoli, I.; Bertola, N.; Maggi, D. High Glucose Impairs Expression and Activation of MerTK in ARPE-19 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazour, G.J.; Baker, S.A.; Deane, J.A.; Cole, D.G.; Dickert, B.L.; Rosenbaum, J.L.; Witman, G.B.; Besharse, J.C. The Intraflagellar Transport Protein, IFT88, Is Essential for Vertebrate Photoreceptor Assembly and Maintenance. J Cell Biol 2002, 157, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinna, C.; Besharse, J.C. Intraflagellar Transport and the Sensory Outer Segment of Vertebrate Photoreceptors. Dev Dyn 2008, 237, 1982–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, R.D.; Linsenmeier, R.A.; Goldstick, T.K. Oxygen Consumption in the Inner and Outer Retina of the Cat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995, 36, 542–554. [Google Scholar]

- Wangsa-Wirawan, N.D.; Linsenmeier, R.A. Retinal Oxygen: Fundamental and Clinical Aspects. Arch Ophthalmol 2003, 121, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdeaux, O.; Juaneda, P.; Martine, L.; Cabaret, S.; Bretillon, L.; Acar, N. Identification and Quantification of Phosphatidylcholines Containing Very-Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid in Bovine and Human Retina Using Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2010, 1217, 7738–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: A Concept in Redox Biology and Medicine. Redox Biol 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, E.B.; Marfany, G. The Relevance of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Retinal Dystrophies. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellezza, I. Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: NRF2 as Therapeutic Target. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léveillard, T.; Mohand-Saïd, S.; Lorentz, O.; Hicks, D.; Fintz, A.C.; Clérin, E.; Simonutti, M.; Forster, V.; Cavusoglu, N.; Chalmel, F.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Rod-Derived Cone Viability Factor. Nat Genet 2004, 36, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, E.H.; van Dijk, H.W.; Jiao, C.; Kok, P.H.B.; Jeong, W.; Demirkaya, N.; Garmager, A.; Wit, F.; Kucukevcilioglu, M.; van Velthoven, M.E.J.; et al. Retinal Neurodegeneration May Precede Microvascular Changes Characteristic of Diabetic Retinopathy in Diabetes Mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E2655–E2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, B.A. Preventing Diabetic Retinopathy by Mitigating Subretinal Space Oxidative Stress in Vivo. Vis Neurosci 2020, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, B.A. Preventing Diabetic Retinopathy by Mitigating Subretinal Space Oxidative Stress in Vivo. Vis Neurosci 2020, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Bek, T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Diabetic Retinopathy. Mitochondrion 2017, 36, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Musante, L.; Bachi, A.; Ravera, S.; Calzia, D.; Cattaneo, A.; Bruschi, M.; Bianchini, P.; Diaspro, A.; Morelli, A.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of the Retinal Rod Outer Segment Disks. J Proteome Res 2008, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Calzia, D.; Morelli, A.M.; Panfoli, I. Efficient Extra-Mitochondrial Aerobic ATP Synthesis in Neuronal Membrane Systems. J Neurosci Res 2021, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzia, D.; Garbarino, G.; Caicci, F.; Pestarino, M.; Manni, L.; Traverso, C.E.; Panfoli, I.; Candiani, S. Evidence of Oxidative Phosphorylation in Zebrafish Photoreceptor Outer Segments at Different Larval Stages. J Histochem Cytochem 2018, 66, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Calzia, D.; Bianchini, P.; Ravera, S.; Diaspro, A.; Candiano, G.; Bachi, A.; Monticone, M.; Aluigi, M.G.; Barabino, S.; et al. Evidence for Aerobic Metabolism in Retinal Rod Outer Segment Disks. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2009, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzia, D.; Garbarino, G.; Caicci, F.; Manni, L.; Candiani, S.; Ravera, S.; Morelli, A.; Traverso, C.E.; Panfoli, I. Functional Expression of Electron Transport Chain Complexes in Mouse Rod Outer Segments. Biochimie 2014, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzia, D.; Degan, P.; Caicci, F.; Bruschi, M.; Manni, L.; Ramenghi, L.A.; Candiano, G.; Traverso, C.E.; Panfoli, I. Modulation of the Rod Outer Segment Aerobic Metabolism Diminishes the Production of Radicals Due to Light Absorption. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzia, D.; Oneto, M.; Caicci, F.; Bianchini, P.; Ravera, S.; Bartolucci, M.; Diaspro, A.; Degan, P.; Manni, L.; Traverso, C.E.; et al. Effect of Polyphenolic Phytochemicals on Ectopic Oxidative Phosphorylation in Rod Outer Segments of Bovine Retina. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, K.C.; Aotaki-Keen, A.E.; Putkey, F.R.; Hjelmeland, L.M. ARPE-19, a Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell Line with Differentiated Properties. Exp Eye Res 1996, 62, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeling, E.; Culling, A.J.; Johnston, D.A.; Chatelet, D.S.; Page, A.; Tumbarello, D.A.; Lotery, A.J.; Ratnayaka, J.A. An In-Vitro Cell Model of Intracellular Protein Aggregation Provides Insights into RPE Stress Associated with Retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, S.A.; Ward, G.; Keeling, E.; Scott, J.A.; Cree, A.J.; Johnston, D.A.; Page, A.; Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Bhaskar, A.; Grossel, M.C.; et al. Ex-Vivo Models of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) in Long-Term Culture Faithfully Recapitulate Key Structural and Physiological Features of Native RPE. Tissue Cell 2017, 49, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Calzia, D.; Ravera, S.; Bianchini, P.; Diaspro, A. Maximizing the Rod Outer Segment Yield in Retinas Extracted from Cattle Eyes. Bio Protoc 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnetkamp, P.P.M.; Daemen, F.J.M. Isolation and Characterization of Osmotically Sealed Bovine Rod Outer Segments. Methods Enzymol 1982, 81, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, E.; Cuccarolo, P.; Stroppiana, G.; Miano, M.; Bottega, R.; Cossu, V.; Degan, P.; Ravera, S. Defects in Mitochondrial Energetic Function Compels Fanconi Anaemia Cells to Glycolytic Metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, E.; Degan, P.; Bruno, S.; Pierri, F.; Miano, M.; Raggi, F.; Farruggia, P.; Mecucci, C.; Crescenzi, B.; Naim, V.; et al. The Passage from Bone Marrow Niche to Bloodstream Triggers the Metabolic Impairment in Fanconi Anemia Mononuclear Cells. Redox Biol 2020, 36, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, P.C. P/O Ratios of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2005, 1706, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenov, A.N.; Maksimov, E.G.; Moysenovich, A.M.; Yakovleva, M.A.; Tsoraev, G. V.; Ramonova, A.A.; Shirshin, E.A.; Sluchanko, N.N.; Feldman, T.B.; Rubin, A.B.; et al. Protein-Mediated Carotenoid Delivery Suppresses the Photoinducible Oxidation of Lipofuscin in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, T.; Höhn, A.; Grune, T. Lipofuscin: Detection and Quantification by Microscopic Techniques. Methods Mol Biol 2010, 594, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Ravera, S.; Traverso, C.; Amaro, A.; Piaggio, F.; Emionite, L.; Bachetti, T.; Pfeffer, U.; Raffaghello, L. Curcumin Induces a Fatal Energetic Impairment in Tumor Cells in Vitro and in Vivo by Inhibiting ATP-Synthase Activity. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, A.; Cossu, V.; Marini, C.; Castellani, P.; Raffa, S.; Donegani, M.I.; Bruno, S.; Ravera, S.; Emionite, L.; Orengo, A.M.; et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography Tracks the Heterogeneous Brain Susceptibility to the Hyperglycemia-Related Redox Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Bertola, N.; Pasquale, C.; Bruno, S.; Benedicenti, S.; Ferrando, S.; Zekiy, A.; Arany, P.; Amaroli, A. 808-Nm Photobiomodulation Affects the Viability of a Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma Cellular Model, Acting on Energy Metabolism and Oxidative Stress Production. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How Mitochondria Produce Reactive Oxygen Species. Biochemical Journal 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchia, A.; Biondi, A.; Genova, M.L.; Lenaz, G.; Falasca, A. The Various Sources of Mitochondrial Oxygen Radicals: A Minireview. Toxicol Mech Methods 2004, 14, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaz, G. The Mitochondrial Production of Reactive Oxygen Species: Mechanisms and Implications in Human Pathology. IUBMB Life 2001, 52, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaz, G. Role of Mitochondria in Oxidative Stress and Ageing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1998, 1366, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, L.; Tancreda, G.; Iobbi, V.; Caicci, F.; Bruno, S.; Esposito, A.; Calzia, D.; Benini, S.; Bisio, A.; Manni, L.; et al. The Flavone Cirsiliol from Salvia x Jamensis Binds the F1 Moiety of ATP Synthase, Modulating Free Radical Production. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, B.A.; Qian, H. OCT Imaging of Rod Mitochondrial Respiration in Vivo. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/15353702211013799. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Kowluru, A.; Mishra, M.; Kumar, B. Oxidative Stress and Epigenetic Modifications in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res 2015, 48, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Musante, L.; Bachi, A.; Ravera, S.; Calzia, D.; Cattaneo, A.; Bruschi, M.; Bianchini, P.; Diaspro, A.; Morelli, A.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of the Retinal Rod Outer Segment Disks. J Proteome Res 2008, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, M.; Petretto, A.; Caicci, F.; Bartolucci, M.; Calzia, D.; Santucci, L.; Manni, L.; Ramenghi, L.A.; Ghiggeri, G.; Traverso, C.E.; et al. Proteome of Bovine Mitochondria and Rod Outer Segment Disks: Commonalities and Differences. J Proteome Res 2018, 17, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, M.; Bartolucci, M.; Petretto, A.; Calzia, D.; Caicci, F.; Manni, L.; Traverso, C.E.; Candiano, G.; Panfoli, I. Differential Expression of the Five Redox Complexes in the Retinal Mitochondria or Rod Outer Segment Disks Is Consistent with Their Different Functionality. FASEB Bioadv 2020, 2, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panfoli, I.; Calzia, D.; Bruschi, M.; Oneto, M.; Bianchini, P.; Ravera, S.; Petretto, A.; Diaspro, A.; Candiano, G. Functional Expression of Oxidative Phosphorylation Proteins in the Rod Outer Segment Disc. Cell Biochem Funct 2013, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzia, D.; Barabino, S.; Bianchini, P.; Garbarino, G.; Oneto, M.; Caicci, F.; Diaspro, A.; Tacchetti, C.; Manni, L.; Candiani, S.; et al. New Findings in ATP Supply in Rod Outer Segments: Insights for Retinopathies. Biol Cell 2013, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzia, D.; Garbarino, G.; Caicci, F.; Manni, L.; Candiani, S.; Ravera, S.; Morelli, A.; Traverso, C.E.; Panfoli, I. Functional Expression of Electron Transport Chain Complexes in Mouse Rod Outer Segments. Biochimie 2014, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Calzia, D.; Bianchini, P.; Ravera, S.; Diaspro, A.; Candiano, G.; Bachi, A.; Monticone, M.; Aluigi, M.G.; Barabino, S.; et al. Evidence for Aerobic Metabolism in Retinal Rod Outer Segment Disks. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2009, 41, 2555–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfoli, I.; Calzia, D.; Ravera, S.; Morelli, A.M.; Traverso, C.E. Extra-Mitochondrial Aerobic Metabolism in Retinal Rod Outer Segments: New Perspectives in Retinopathies. Med Hypotheses 2012, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olchawa, M.M.; Szewczyk, G.M.; Zadlo, A.C.; Sarna, M.W.; Wnuk, D.; Sarna, T.J. The Effect of Antioxidants on Photoreactivity and Phototoxic Potential of RPE Melanolipofuscin Granules from Human Donors of Different Age. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.Q.; Godley, B.F. Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial DNA Damage in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: A Possible Mechanism for RPE Aging and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Exp Eye Res 2003, 76, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).