Submitted:

26 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw materials

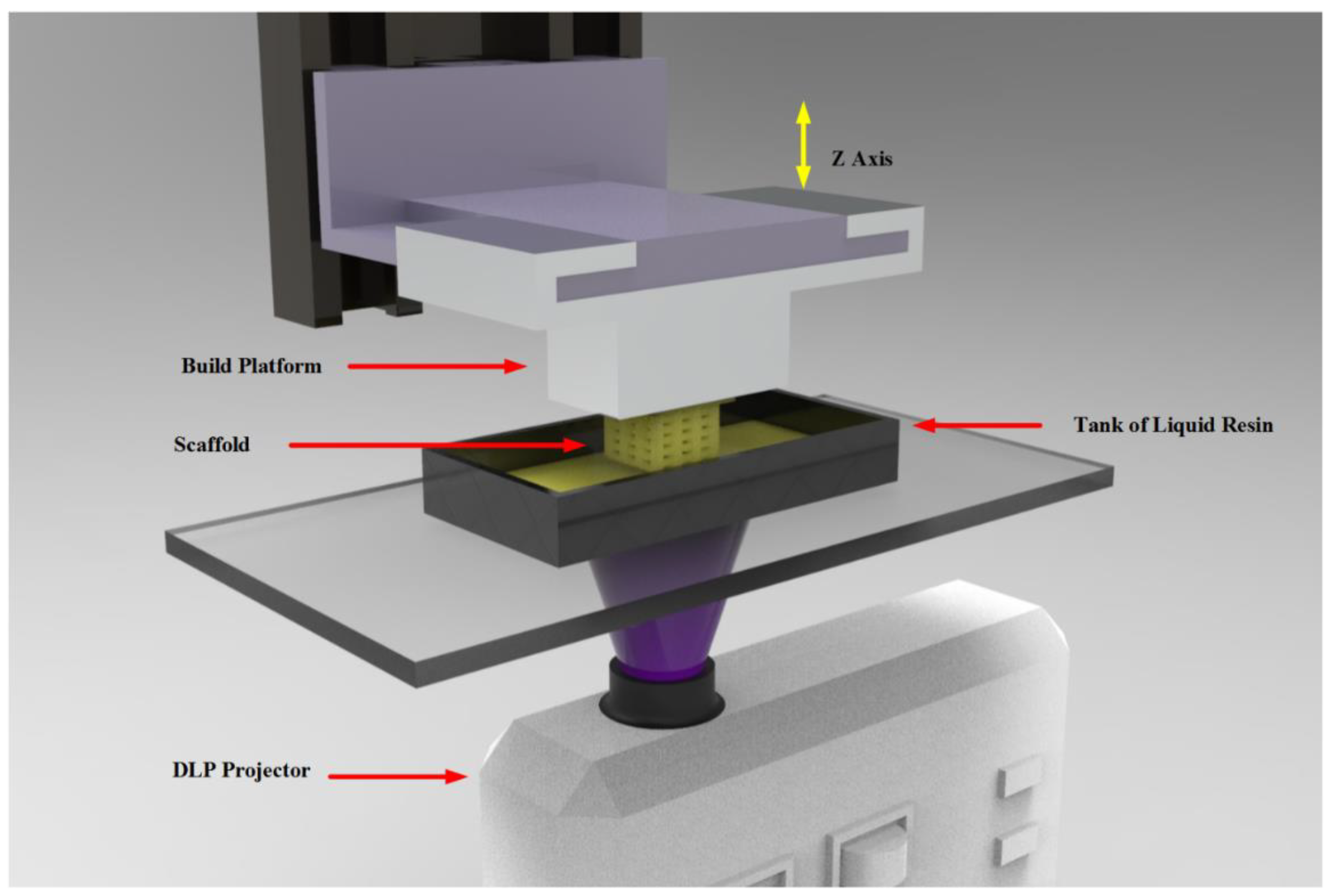

2.2. Equipment and procedure

2.2.1. Working resin preparation

2.2.2. Printing parameters

2.2.3. Samples manufacture

2.3. Printed parts characterization

3. Results and Discussion

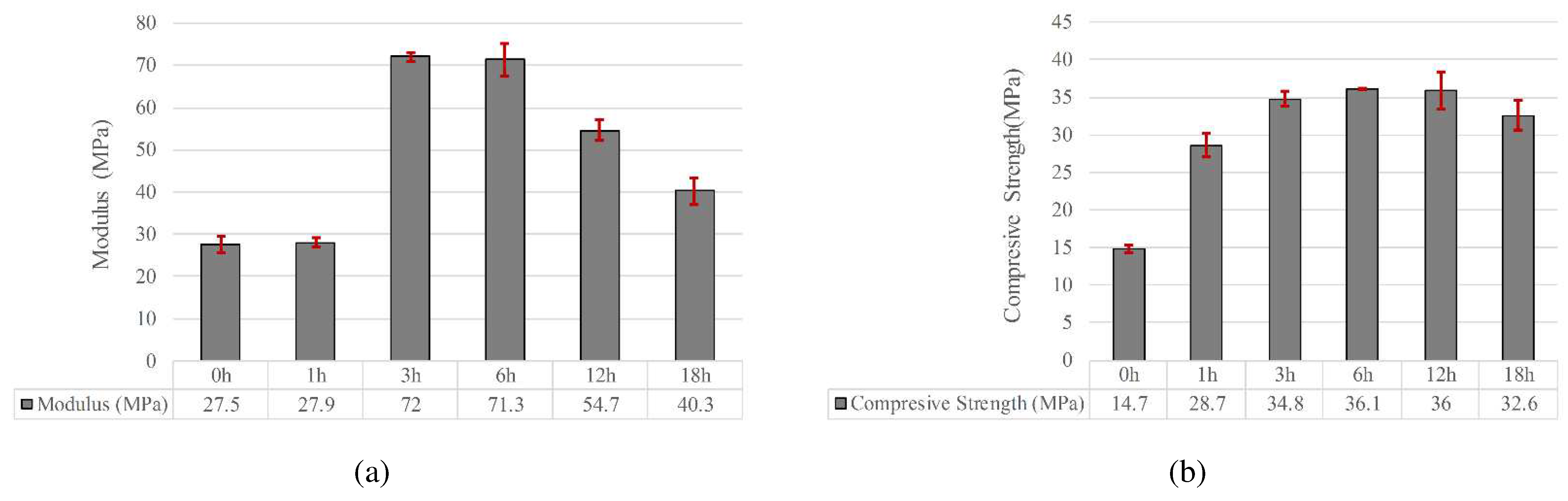

3.1. Mechanical Properties

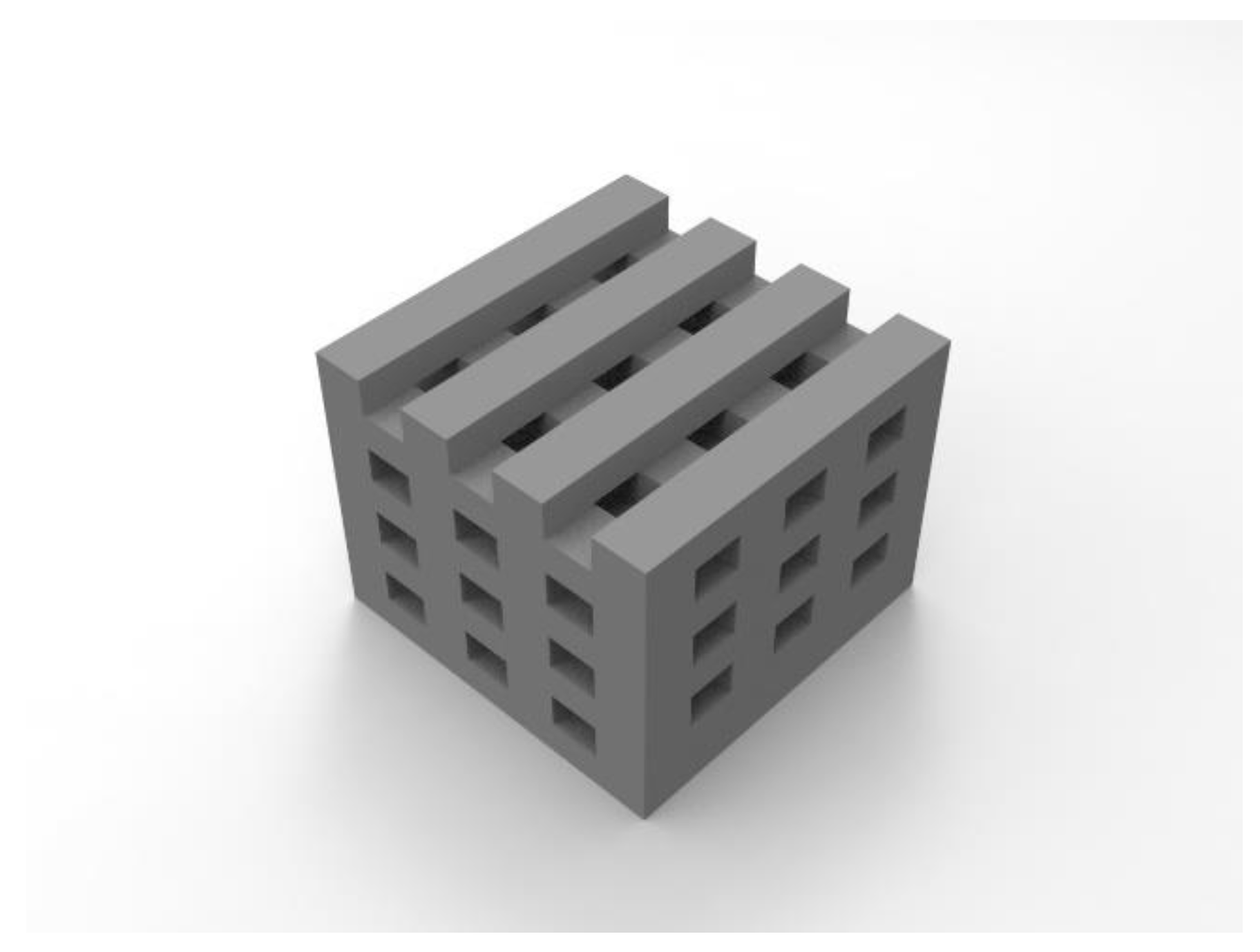

3.2. Scaffold morphology

3.3. MTT assay

3.4. Water contact angle

3.5. In vitro Degradation

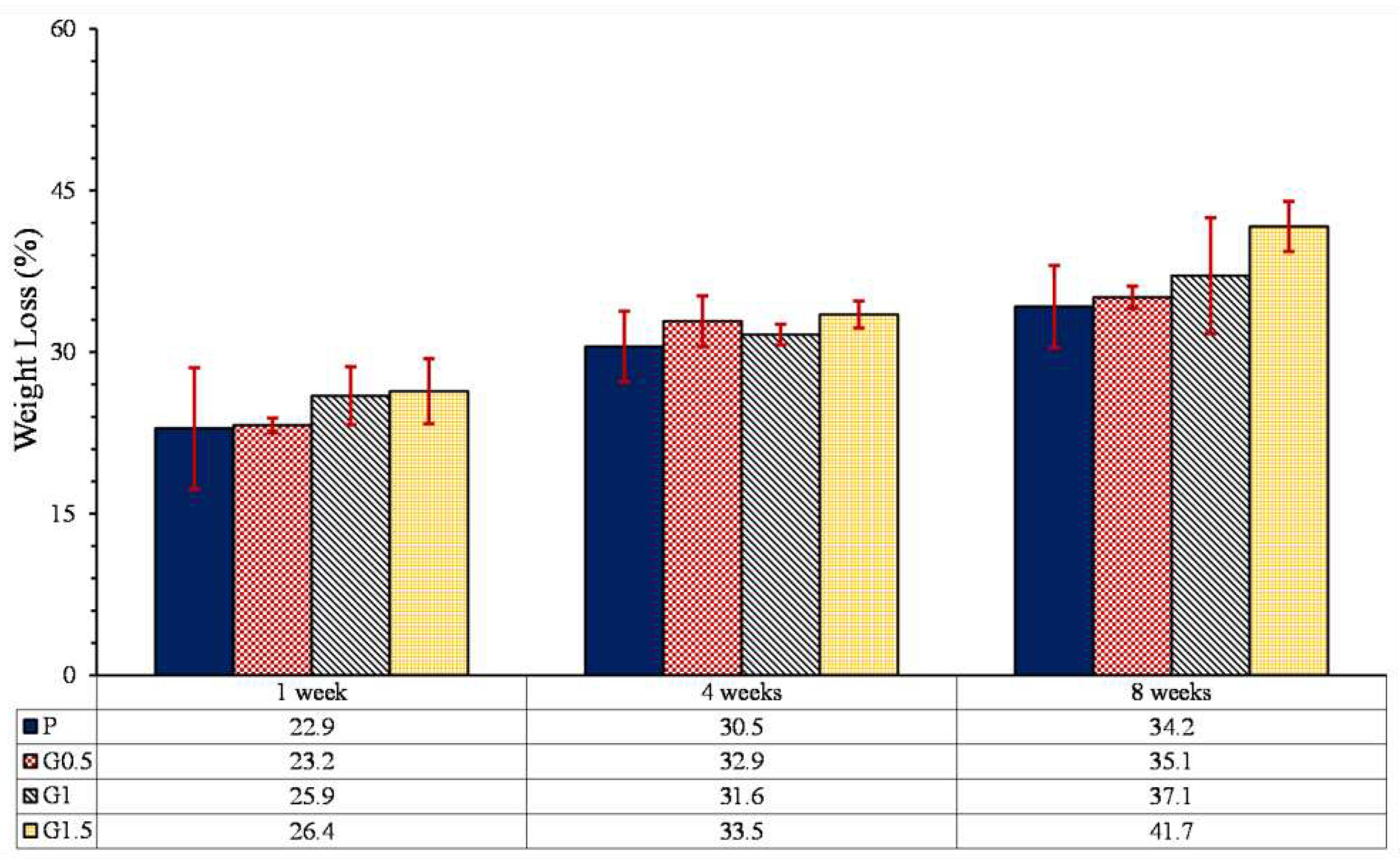

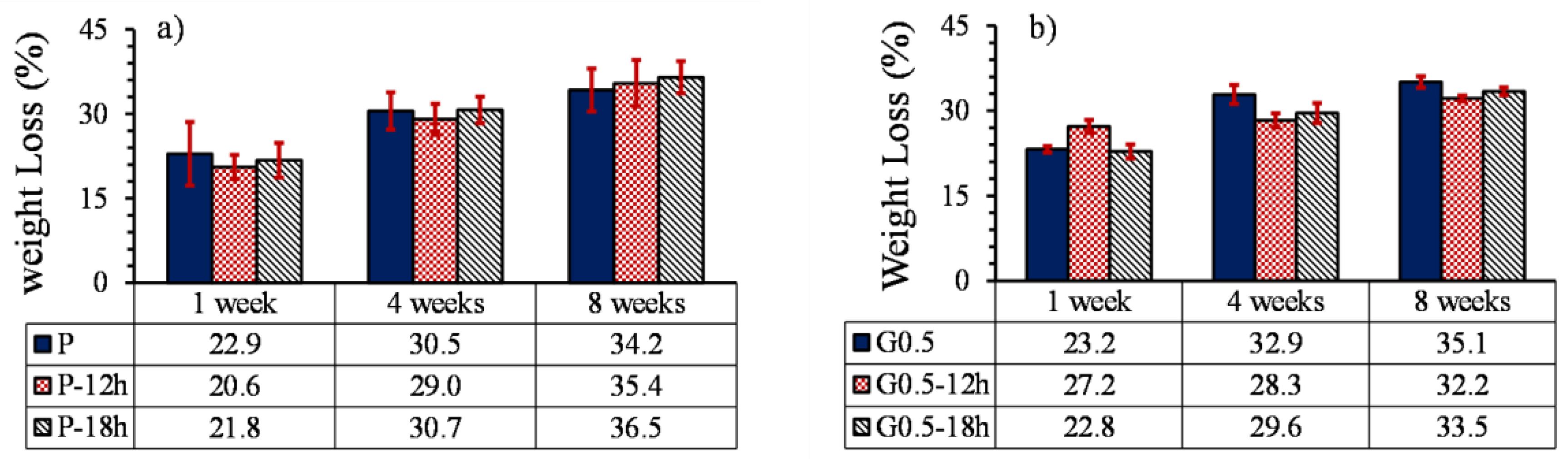

3.5.1. Weight loss

3.5.2. Degradation mechanism

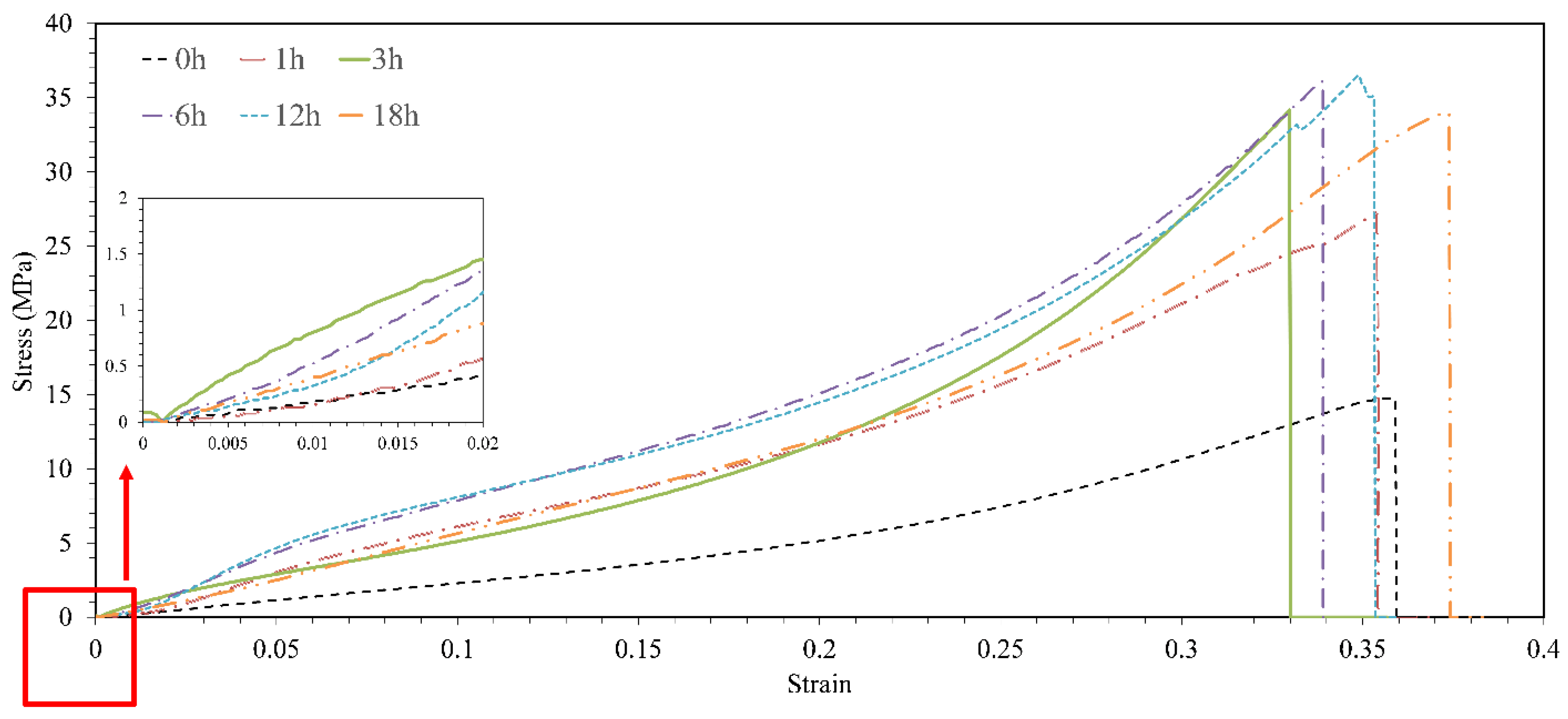

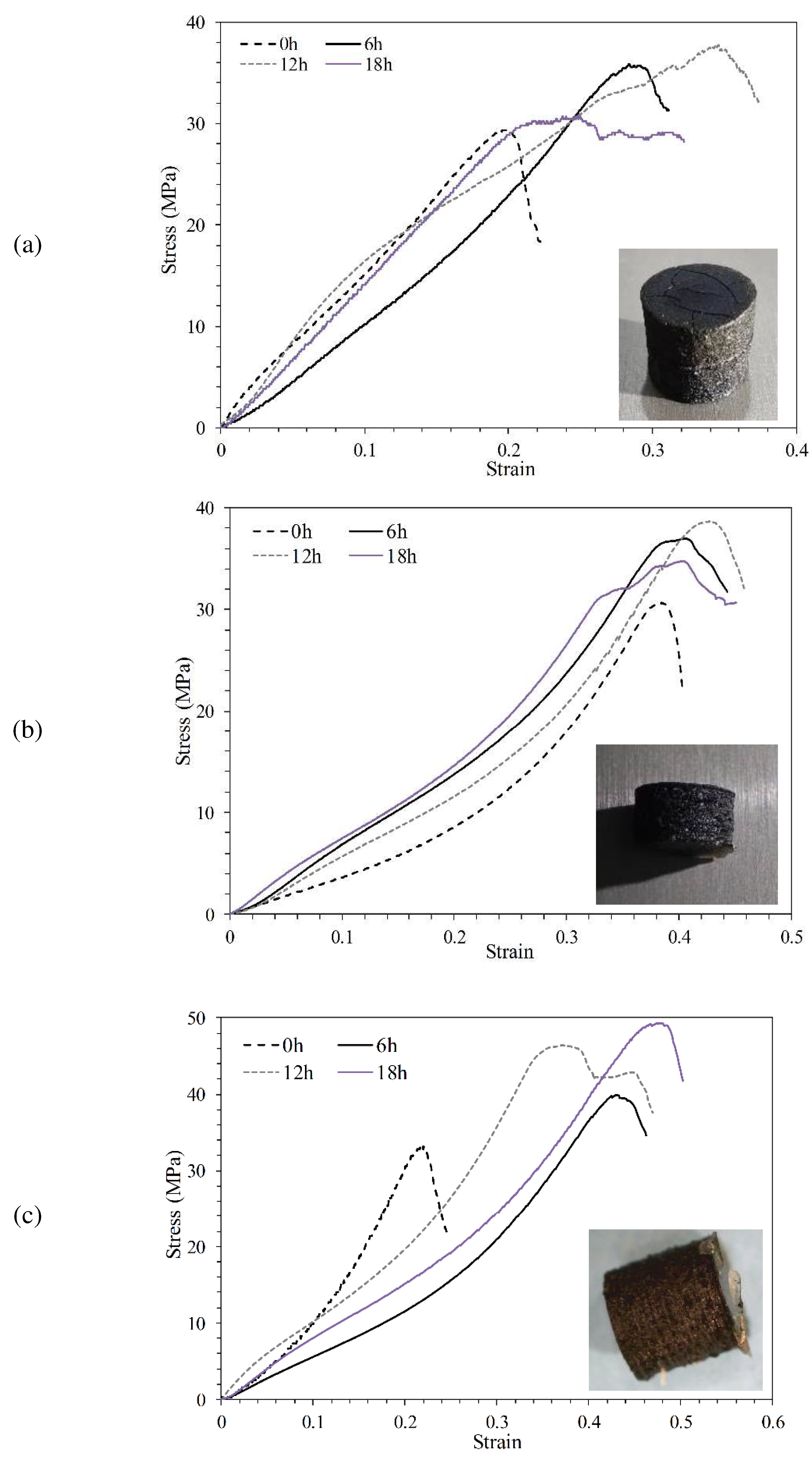

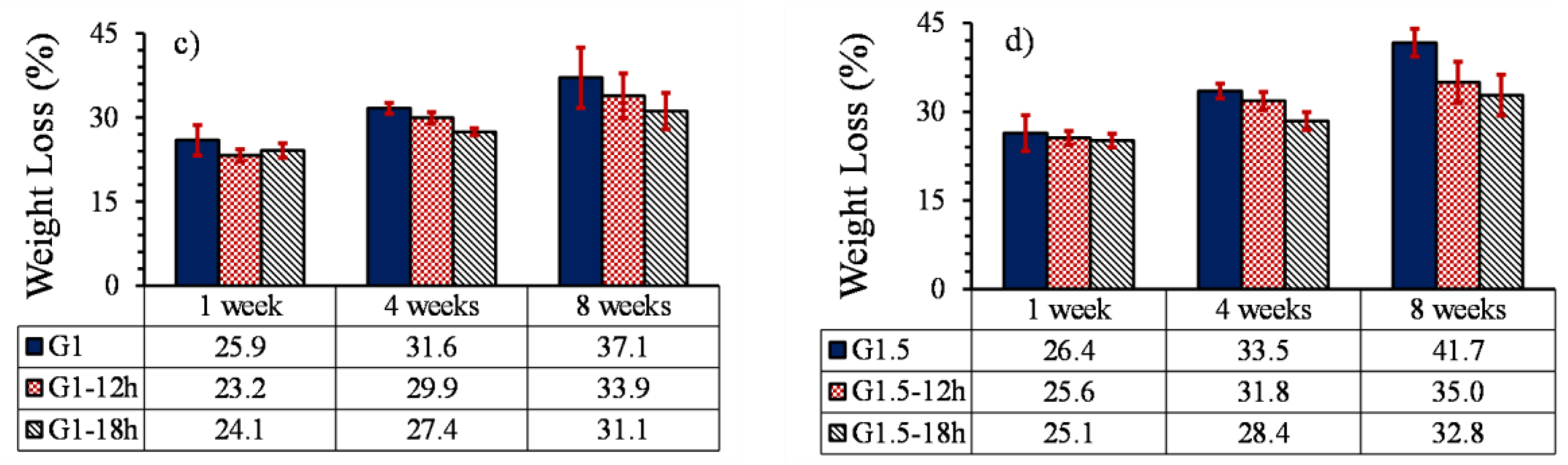

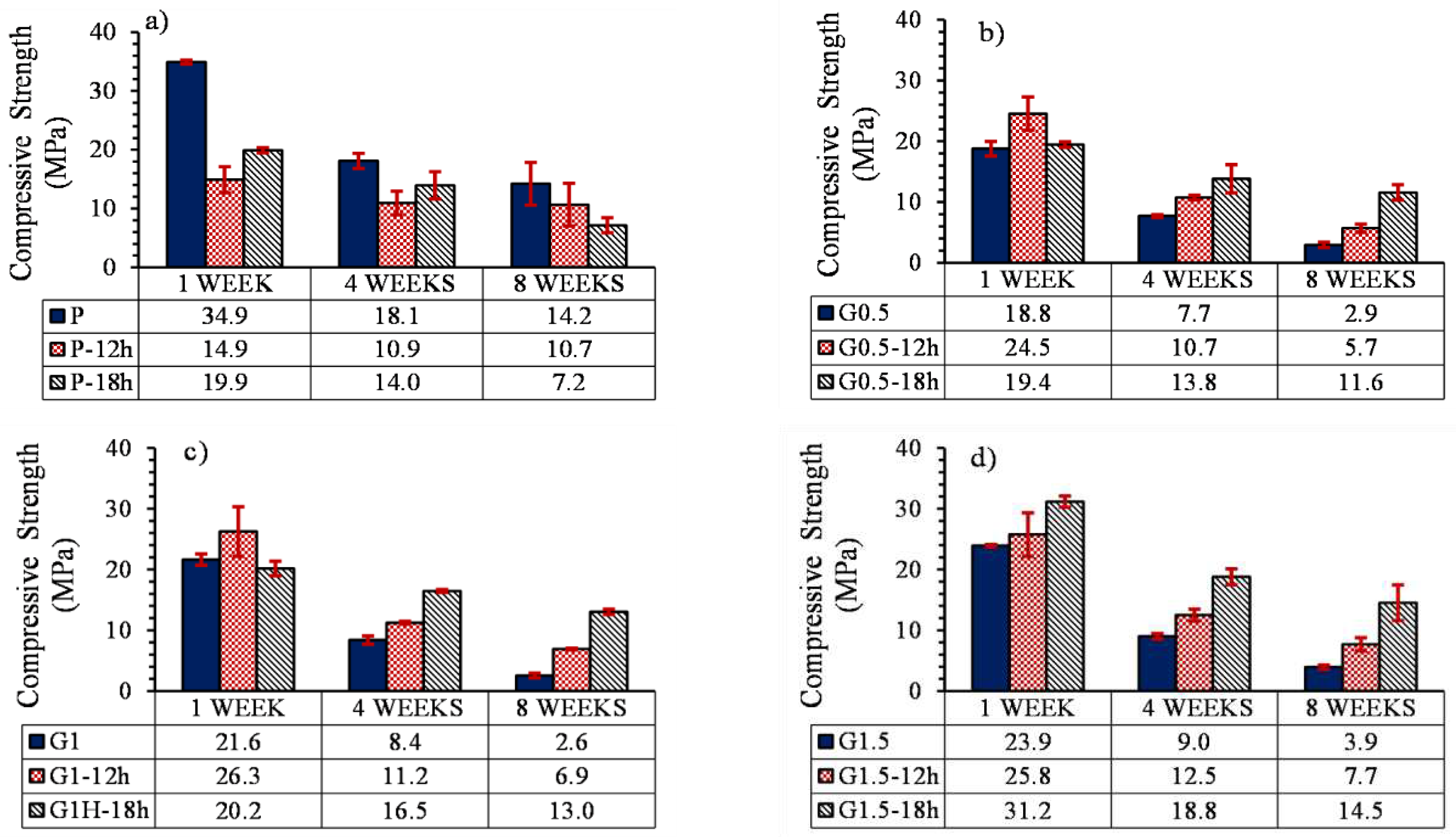

3.5.3. Compressive profile

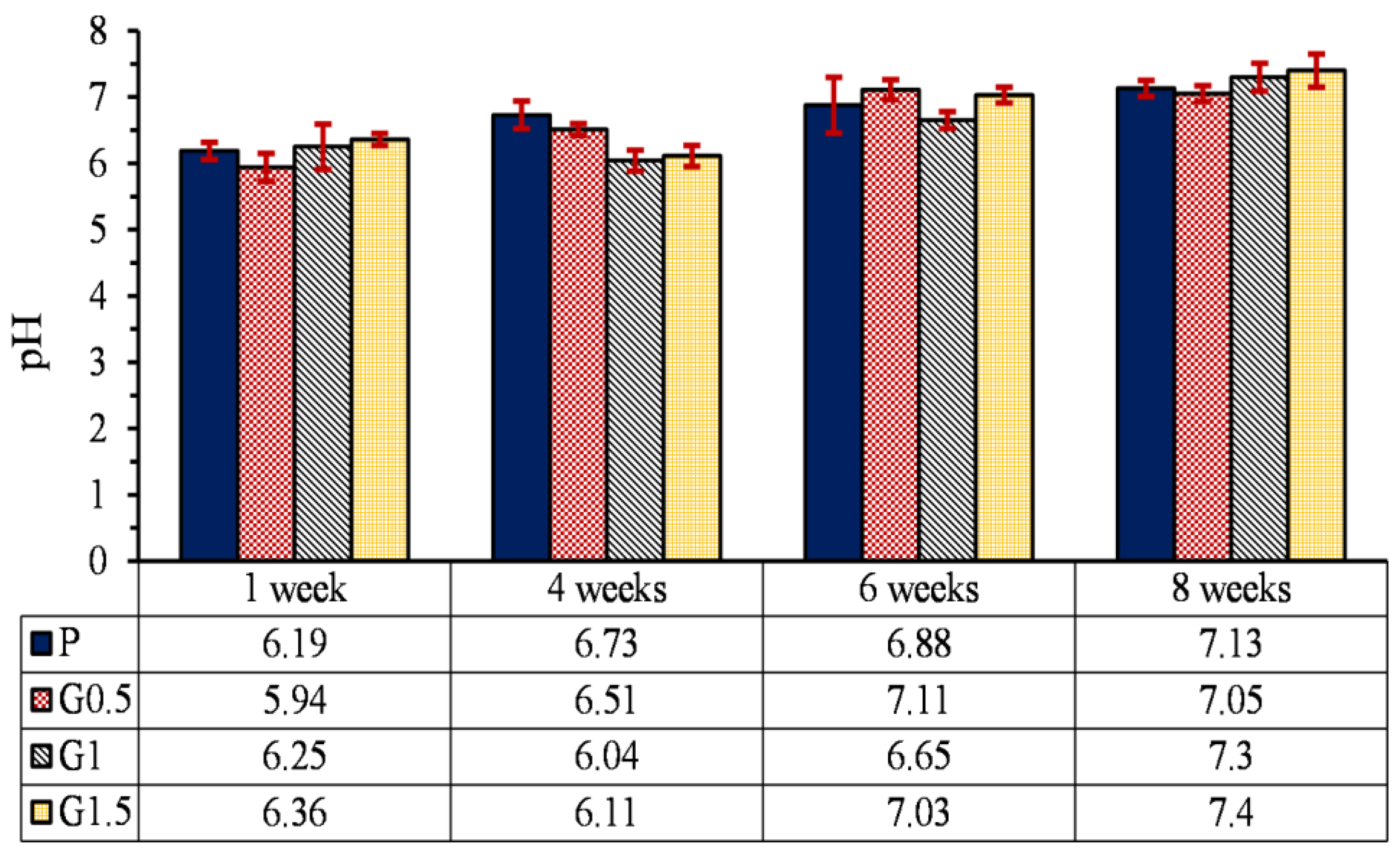

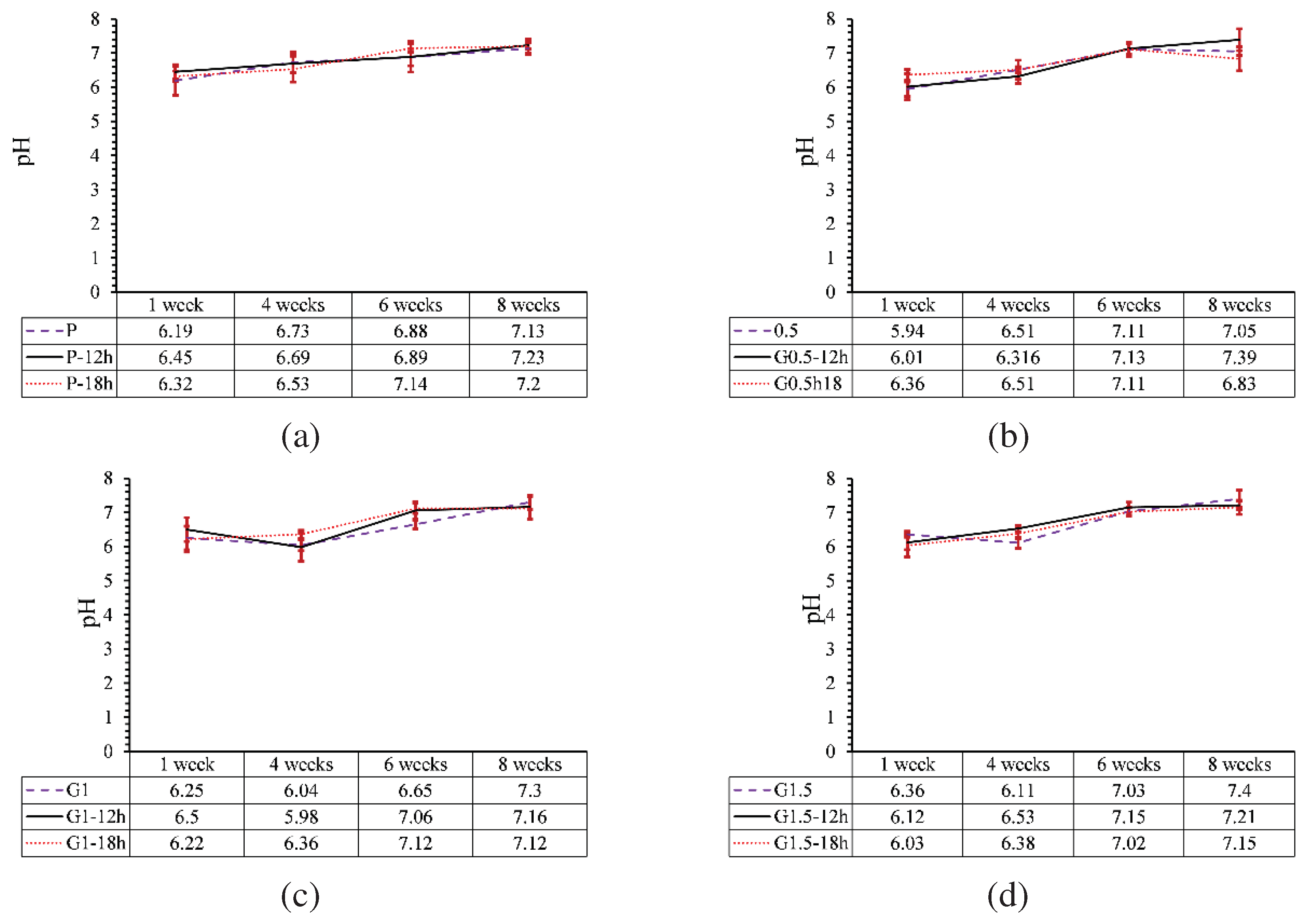

3.5.4. pH changes

4. Conclusion

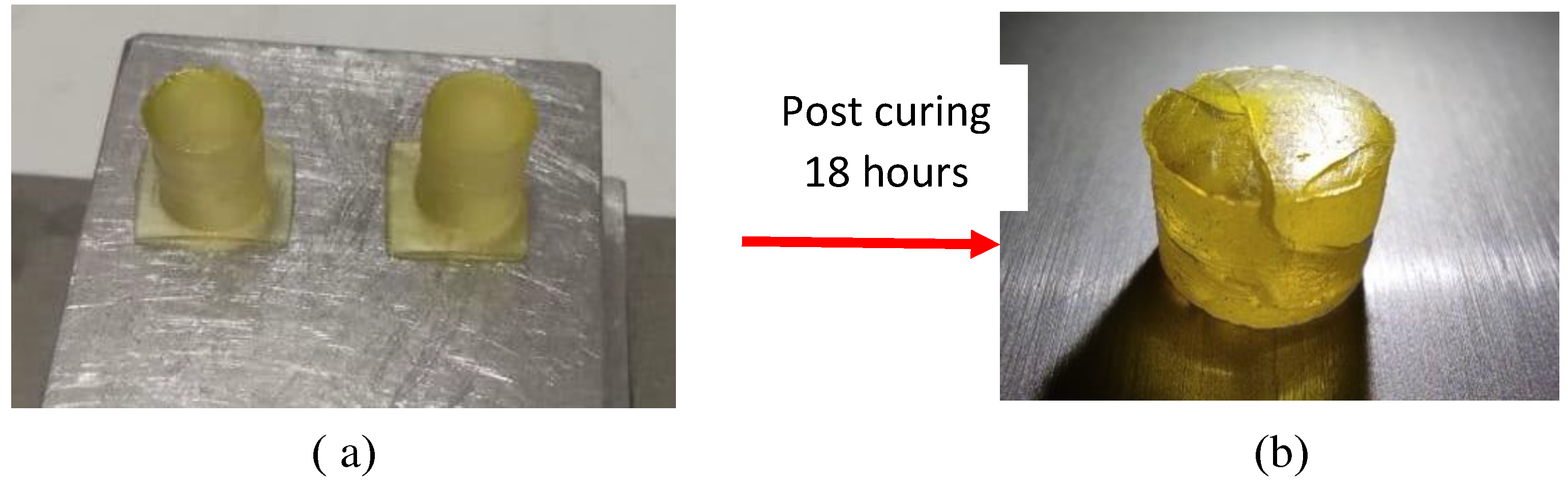

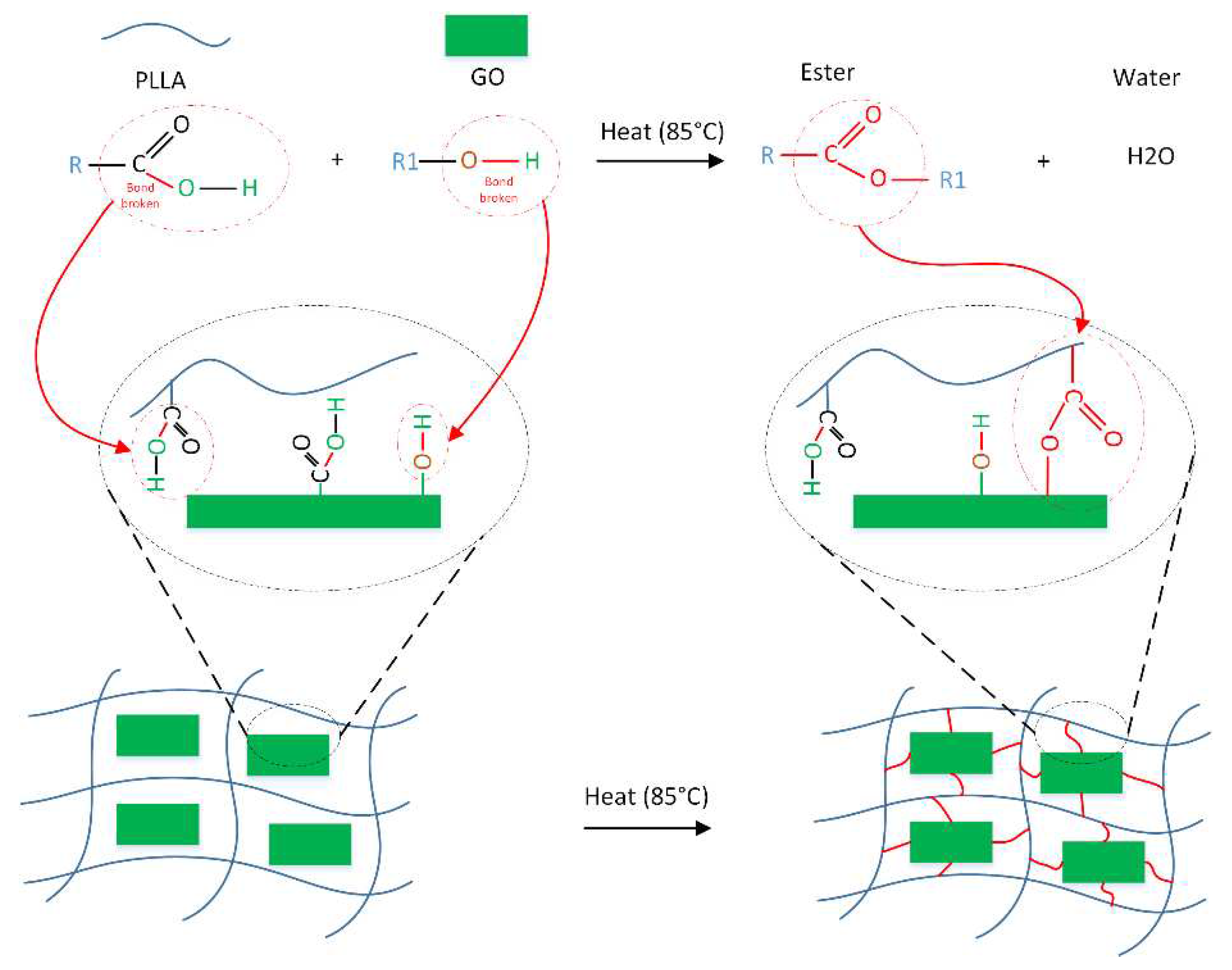

- The compression strength of parts containing 0, 0.5, 1, and 1.5% GO with heat treatment increased by 119, 151, 162 and 235%, respectively. Increasing the mechanical strength of samples containing GO was attributed to the esterification, which caused the formation of ester bonds between GO and PLLA.

- The hydrophilicity of PLLA increased with increasing GO percentage and the water contact angle had an 18% reduction.

- With the increase of GO nanoparticles, weight loss increased, which is due to increasing of hydrophilicity, and formation of microchannels between GO particles and PLLA.

- Heat treatment on samples without GO particles increased the degradation profile by 7% due to the formation of cracks in the parts.

- The effect of heat treatment on the degradation of printed parts reinforced with GO nanoparticles was opposed to the parts without GO and reduced the degradation profile of samples by 17%. Moreover, due to the low percentage of GO particles, the increase in GO content and heat treatment did not have much effect on the pH of the environment of the part.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Bose, S., M. Roy, and A. Bandyopadhyay, Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends in biotechnology, 2012. 30(10): p. 546-554.

- Pinto, P., et al., Therapeutic strategies for bone regeneration: the importance of biomaterials testing in adequate animal models. Adv Compos Mater, 2016: p. 275-319.

- Agarwal, R. and A.J. García, Biomaterial strategies for engineering implants for enhanced osseointegration and bone repair. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 2015. 94: p. 53-62.

- Fillingham, Y. and J. Jacobs, Bone grafts and their substitutes. The bone & joint journal, 2016. 98(1_Supple_A): p. 6-9.

- Florencio-Silva, R., et al., Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed research international, 2015. 2015.

- Marenzana, M. and T.R. Arnett, The key role of the blood supply to bone. Bone research, 2013. 1(1): p. 203-215.

- Gruskin, E., et al., Demineralized bone matrix in bone repair: history and use. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 2012. 64(12): p. 1063-1077.

- Shegarfi, H. and O. Reikeras, Bone transplantation and immune response. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery, 2009. 17(2): p. 206-211.

- Bouët, G., et al., In vitro three-dimensional bone tissue models: from cells to controlled and dynamic environment. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews, 2015. 21(1): p. 133-156.

- Henkel, J., et al., Bone regeneration based on tissue engineering conceptions—a 21st century perspective. Bone research, 2013. 1(1): p. 216-248.

- Abou Neel, E.A., et al., Tissue engineering in dentistry. Journal of dentistry, 2014. 42(8): p. 915-928.

- Aravamudhan, A., et al., Natural and synthetic biomedical polymers. 2014, Elsevier Amsterdam, The Netherlands:.

- Chan, B. and K. Leong, Scaffolding in tissue engineering: general approaches and tissue-specific considerations. European spine journal, 2008. 17(4): p. 467-479.

- O'brien, F.J., Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Materials today, 2011. 14(3): p. 88-95.

- Gil-Castell, O., et al., In vitro validation of biomedical polyester-based scaffolds: Poly (lactide-co-glycolide) as model-case. Polymer Testing, 2018. 66: p. 256-267.

- Thavornyutikarn, B., et al., Bone tissue engineering scaffolding: computer-aided scaffolding techniques. Progress in biomaterials, 2014. 3(2-4): p. 61-102.

- Cao, H. and N. Kuboyama, A biodegradable porous composite scaffold of PGA/β-TCP for bone tissue engineering. Bone, 2010. 46(2): p. 386-395.

- Bajaj, P., et al., 3D biofabrication strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Annual review of biomedical engineering, 2014. 16: p. 247-276.

- Torabi, K., E. Farjood, and S. Hamedani, Rapid prototyping technologies and their applications in prosthodontics, a review of literature. Journal of Dentistry, 2015. 16(1): p. 1.

- Hedayati, S.K., et al., 3D printed PCL scaffold reinforced with continuous biodegradable fiber yarn: A study on mechanical and cell viability properties. Polymer Testing, 2020. 83: p. 106347.

- Roseti, L., et al., Scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: state of the art and new perspectives. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2017. 78: p. 1246-1262.

- Bhattacharjee, N., et al., The upcoming 3D-printing revolution in microfluidics. Lab on a Chip, 2016. 16(10): p. 1720-1742.

- Fiedler, B., et al., Fundamental aspects of nano-reinforced composites. Composites science and technology, 2006. 66(16): p. 3115-3125.

- Lee, C., et al., Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. science, 2008. 321(5887): p. 385-388.

- Terrones, M., et al., Interphases in graphene polymer-based nanocomposites: achievements and challenges. 2011, Wiley Online Library.

- Lin, D., A laser sintered layer of metal matrix consisting of 0D, 1D and 2D nanomaterials and its mechanical behaviors. 2013, Purdue University.

- Dasari, B.L., et al., Mechanical properties of graphene oxide reinforced aluminium matrix composites. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2018. 145: p. 136-144.

- Saed, A.B., et al., Functionalized poly l-lactic acid synthesis and optimization of process parameters for 3D printing of porous scaffolds via digital light processing (DLP) method. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 2020. 56: p. 550-561.

- Saed, A.B., et al., An in vitro study on the key features of Poly L-lactic acid/biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds fabricated via DLP 3D printing for bone grafting. European Polymer Journal, 2020. 141: p. 110057.

- Hedayati, S.K., et al., Additive manufacture of PCL/nHA scaffolds reinforced with biodegradable continuous Fibers: Mechanical Properties, in-vitro degradation Profile, and cell study. European Polymer Journal, 2022. 162: p. 110876.

- Manapat, J.Z., et al., High-strength stereolithographic 3D printed nanocomposites: graphene oxide metastability. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2017. 9(11): p. 10085-10093.

- Karageorgiou, V. and D. Kaplan, Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials, 2005. 26(27): p. 5474-5491.

- Morales-Narváez, E., et al., Graphene-based biosensors: going simple. Advanced Materials, 2017. 29(7): p. 1604905.

- Kaniyoor, A., T.T. Baby, and S. Ramaprabhu, Graphene synthesis via hydrogen induced low temperature exfoliation of graphite oxide. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2010. 20(39): p. 8467-8469.

- Geng, L.-H., et al., Investigation of poly (L-lactic acid)/graphene oxide composites crystallization and nanopore foaming behaviors via supercritical carbon dioxide low temperature foaming. Journal of Materials Research, 2016. 31(3): p. 348-359.

- Shuai, C., et al., Graphene oxide induces ester bonds hydrolysis of poly-l-lactic acid scaffold to accelerate degradation. International Journal of Bioprinting, 2020. 6(1).

- Eckhart, K.E., et al., Covalent conjugation of bioactive peptides to graphene oxide for biomedical applications. Biomaterials science, 2019. 7(9): p. 3876-3885.

- Salvo, P., et al., Graphene-based devices for measuring pH. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2018. 256: p. 976-991.

| Thermal Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature | -27° C |

| Degradation Temperature | 100° C |

| Label | PC-0h | PC-1h | PC-3h | P-6h | PC-12h | PC-18h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post curing time (h) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 18 |

| Label | Percentage of GO (wt%) | Heat treatment period (h) |

|---|---|---|

| P | 0 | 0 |

| P-6h | 0 | 6 |

| P-12h | 0 | 12 |

| P-18h | 0 | 18 |

| G0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| G0.5-6h | 0.5 | 6 |

| G0.5-12h | 0.5 | 12 |

| G0.5-18h | 0.5 | 18 |

| G1 | 1 | 0 |

| G1-6h | 1 | 6 |

| G1-12h | 1 | 12 |

| G1-18h | 1 | 18 |

| G1.5 | 1.5 | 0 |

| G1.5-6h | 1.5 | 6 |

| G1.5-12h | 1.5 | 12 |

| G1.5-18h | 1.5 | 18 |

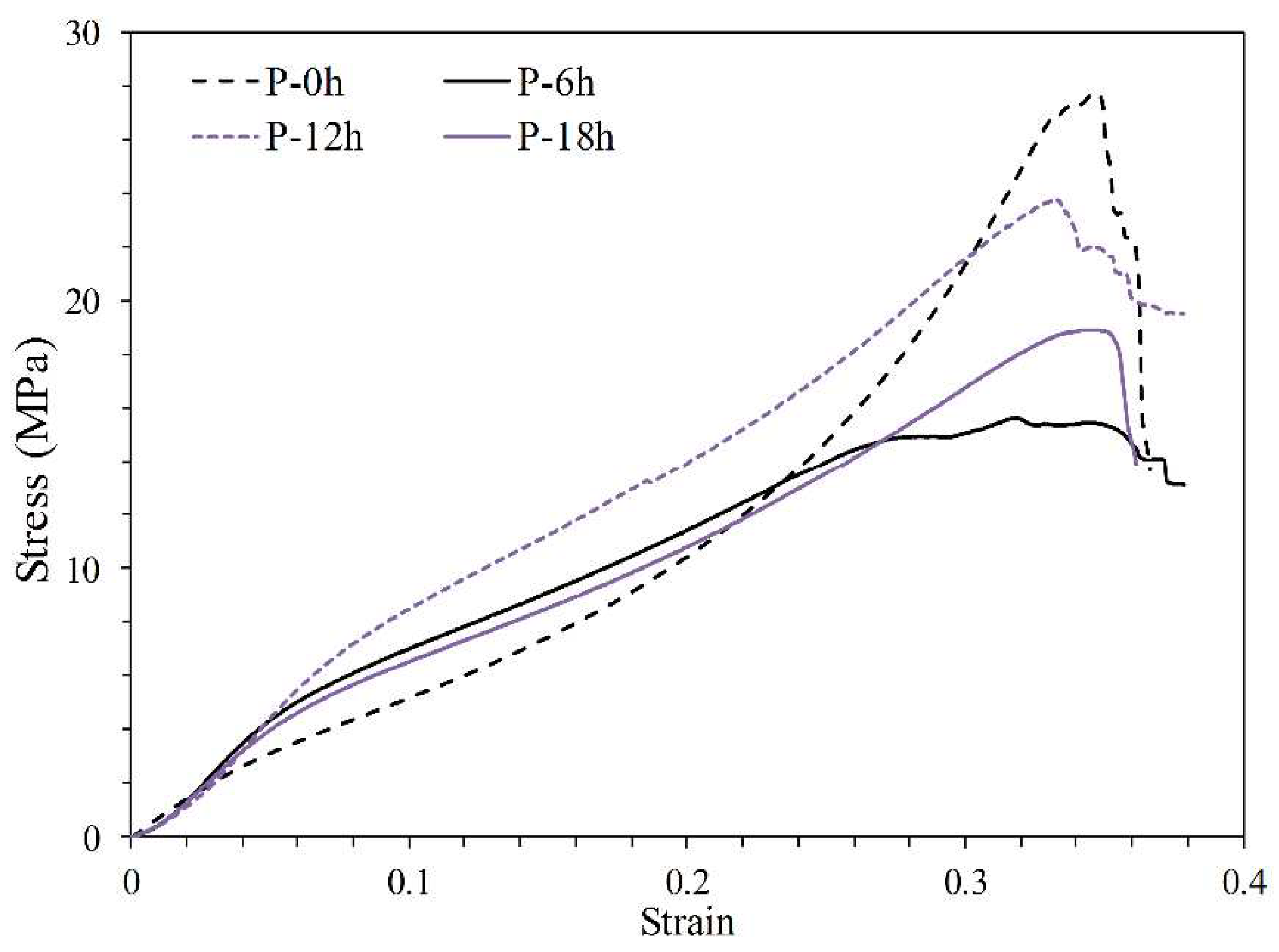

| Label | Compressive strength (MPa) | Young modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| P | 27.7 | 62.3 |

| P-6h | 15.6 | 86.8 |

| P-12h | 23.8 | 89.1 |

| P-18h | 18.9 | 79.6 |

| Percentage of GO (wt%) |

Pore size (µm) |

Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 740-760 | 40 |

| 0.5 | 520-560 | 37 |

| 1 | 550-590 | 36 |

| 1.5 | 500-524 | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).