Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and culture conditions

2.2. Preparation of inoculum and experiments

2.3. Quantification of microorganisms

2.4. Mathematical models

2.4.1. Modelling the microbial interaction in co-cultures

2.4.2. Parameter determination and evaluation of model performance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. One-Step Analysis of Competitive Growth

| Parameters | E. coli (strain BR) | E. coli (strain PS2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | In milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | |

| xmax,Lab | 9.34 ±0.04 | 9.32 ±0.03 | 9.36 ±0.04 | 9.33 ±0.04 |

| xmax,Ec | 4.17 ±0.16 | 3.95 ±0.10 | 5.14 ±0.17 | 5.14 ±0.10 |

| xmax,Gc | 5.96 ±0.08 | 6.09 ±0.10 | 5.72 ±0.08 | 6.04 ±0.17 |

| ILE | 1.158 ±0.093 | 1.254 ±0.100 | 0.957 ±0.059 | 0.951 ±0.054 |

| IEL | 0.526 ±0.045 | 0.536 ±0.049 | 0.588 ±0.042 | 0.513 ±0.035 |

| kGc | 0.850 ±0.038 | 0.710 ±0.025 | 0.931 ±0.048 | 0.749 ±0.046 |

| kref | 0.101 ±0.006 | 0.101 ±0.006 | 0.133 ±0.006 | 0.081 ±0.006 |

| xres,Ec | 0.4a | 0.42 ±0.16 | 1.20 ±0.29 | 0.5d |

| zEc | 30.67 ±5.68 | 32.25d | 6.38 ±0.70 | 28.21 ±5.76 |

| bλ,Gc | 0.0109 ±0.0003 | 0.0101 ±0.0003 | 0.0096 ±0.0002 | 0.0085 ±0.0002 |

| bT,Gcb | 0.0228b | 0.0228b | 0.0228a | 0.0228a |

| Tmin,Gcb | 0.00b | 0.00b | 0.00a | 0.00a |

| bλ,Labc | 0.0343c | 0.0343c | 0.0343b | 0.0343b |

| bT,Labc | 0.0384c | 0.0384c | 0.0384b | 0.0384b |

| Tmin,Lab | 1.11c | 1.11c | 1.11b | 1.11b |

| bλ,Ec | 0.0493c | 0.0493c | 0.0365 ±0.0045 | 0.0366 ±0.0044 |

| bT,Ec | 0.0421c | 0.0421c | 0.052c | 0.052c |

| Tmin,Ec | 4.16c | 4.16c | 4.80c | 4.80c |

| Parameters | S. aureus (strain 2064) | S. aureus (strain 14733) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | In milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | |

| xmax,Lab | 9.43 ±0.03 | 9.40 ±0.05 | 9.34 ±0.03 | 9.25 ±0.03 |

| xmax,Sa | 3.83 ±0.15 | 4.17 ±0.11 | 4.43 ±0.12 | 4.43 ±0.16 |

| xmax,Gc | 5.65 ±0.12 | 5.82 ±0.17 | 5.85 ±0.11 | 6.04 ±0.15 |

| ILS | 1.262 ±0.056 | 1.083 ±0.057 | 1.064 ±0.044 | 0.912 ±0.043 |

| ISL | 0.308 ±0.144 | 0.174 ±0.089 | 0.705 ±0.079 | 0.526 ±0.054 |

| cLS | - | - | - | - |

| cSL | - | - | - | - |

| kGc | 0.995 ±0.067 | 0.778 ±0.058 | 0.906 ±0.048 | 0.850 ±0.055 |

| kref | 0.133 ±0.022 | 0.102 ±0.007 | 0.107 ±0.007 | 0.094 ±0.006 |

| xres,Sa | 1.47 ±0.13 | 0.3c | 0.5c | 0.5c |

| zSa | 9.46 ±1.21 | 10.44 ±0.51 | 11.49 ±1.18 | 13.79 ±1.67 |

| bλ,Gc | 0.0092 ±0.0002 | 0.0086 ±0.0003 | 0.0104 ±0.0003 | 0.0086 ±0.0002 |

| bT,Gc | 0.0228 a | 0.0228 a | 0.0228 a | 0.0228 a |

| Tmin,Gc | 0.00a | 0.00a | 0.00a | 0.00a |

| bλ,Lab | 0.0343b | 0.0343b | 0.0384b | 0.0384b |

| bT,Lab | 0.0384b | 0.0384b | 1.11b | 1.11b |

| Tmin,Lab | 1.11b | 1.11b | 0.0302b | 0.0302b |

| bλ,Sa | 0.0302b | 0.0302b | 0.0409b | 0.0409b |

| bT,Sa | 0.0409b | 0.0409b | 5.02b | 5.02b |

| Tmin,Sa | 5.02b | 5.02b | ||

| Indices | E. coli BR | E. coli PS2 | S. aureus 2064 | S. aureus 14733 | ||||

| in milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | in milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | in milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | in milk | 1 % NaCl in milk | |

| SSE | 14.719 | 16.080 | 19.450 | 25.719 | 10.625 | 11.725 | 15.184 | 17.592 |

| R2 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.987 | 0.986 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.988 |

| pE | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| RMSE | 0.251 | 0.254 | 0.289 | 0.324 | 0.280 | 0.284 | 0.270 | 0.282 |

3.2. Model validation

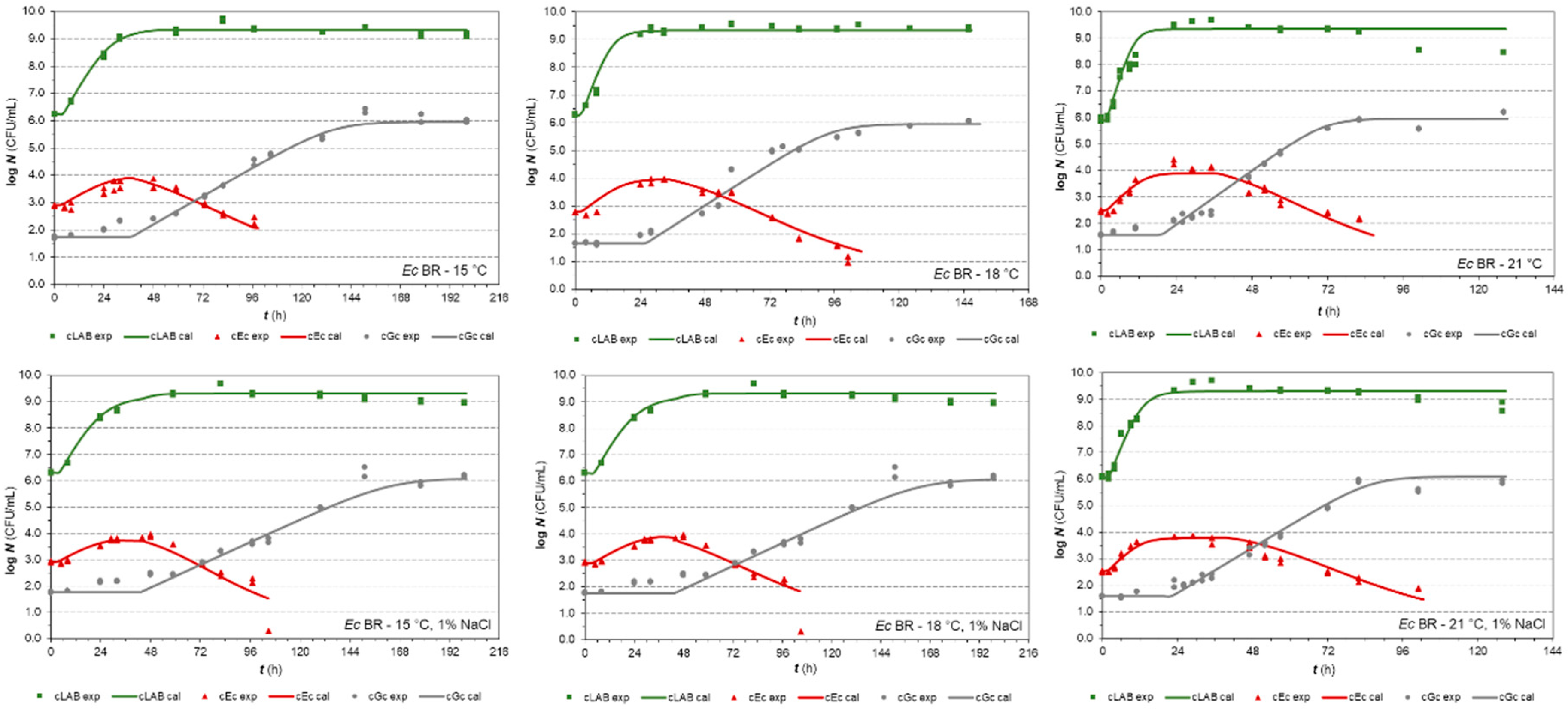

3.2.1. E. coli strains in co-cultures

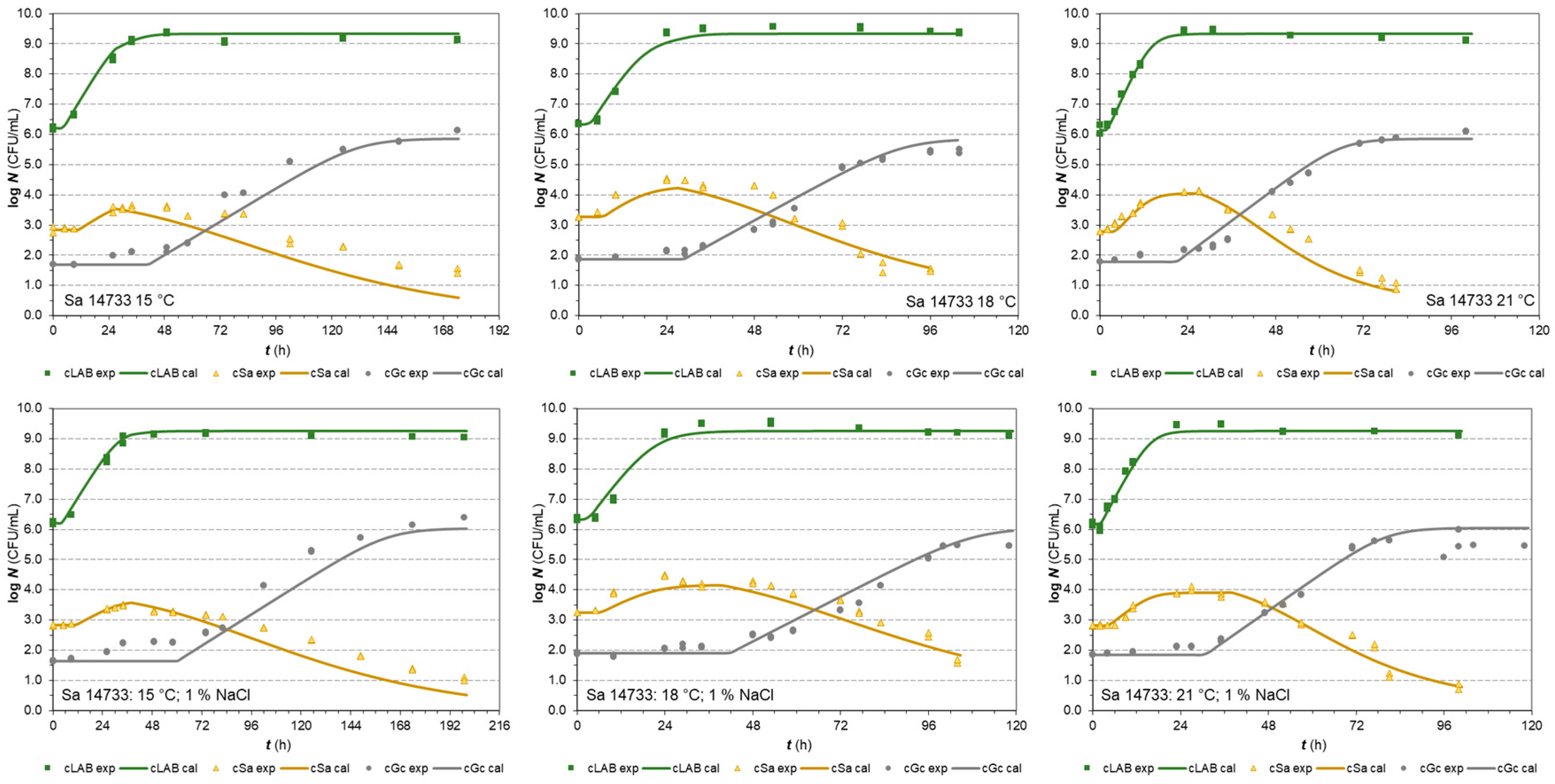

3.2.2. S. aureus strains in co-cultures

4. Conclusions

References

- Licitra, G.; Caccamo, M.; Lortal, S. Artisanal Products Made With Raw Milk. In Raw Milk: Balance Between Hazards and Benefits; Nero, L.A., De Carvalho, A.F., Eds., Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 175–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šipošová, P.; Lehotová, V.; Valík, Ľ.; Medveďová, A. Microbiological quality assessment of raw milk from a vending machine and of traditional Slovakian pasta filata cheeses. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2020, 59, 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lehotová, V.; Antálková, V.; Medveďová, A.; Valík, Ľ. Quantitative Microbiological Analysis of Artisanal Stretched Quantitative Microbiological Analysis of Artisanal Stretched. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs de Souza, C.; Angioletti, B.L.; Hoffmann, T.G.; Bertoli, S.L.; Reiter, M.G. Promoting the appreciation and marketability of artisanal Kochkäse (traditional German cheese): A review. International Dairy Journal 2022, 126, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettera, L.; Levante, A.; Bancalari, E.; Bottari, B.; Gatti, M. Lactic acid bacteria in cow raw milk for cheese production: Which and how many? Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 13, 1092224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoustra, S.; van der Zon, C.; Groenenboom, A.; Moonga, H.B.; Shindano, J.; Smid, E.J.; Hazeleger, W. Microbiological safety of traditionally processed fermented foods based on raw milk, the case of Mabisi from Zambia. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2022, 113997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras, J.; Chassard, C.; Callon, C.; Rifa, E.; Rifa, S.; Lebecque, A.D. Lactic Starter Dose Shapes S. aureus and STEC O26:H11 Growth, and Bacterial Community Patterns in Raw Milk Uncooked Pressed Cheeses. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medveďová, A.; Koňuchová, M.; Kvočiková, K.; Hatalová, I.; Valík, Ľ. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Addition on the Microbiological Safety of Pasta-Filata Types of Cheeses. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 612528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medveďová, A.; Valík, Ľ. Staphylococcus aureus: Characterisation and Quantitative Growth Description in Milk and Artisanal Raw Milk Cheese Production. In Structure and Function of Food Engineering, Ayman Amer Eissa (Ed.); InTech: Rijeka, 2012; pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Palo, V.; Kaláb, M. Slovak sheep cheeses. Milchwissenshaft 1984, 39, 518–521. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Akabanda, F.; Agyei, D.; Jespersen, L. Microbial Safety of Milk Production and Fermented Dairy Products in Africa. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Zotta, T.; Ricciardi, A. A review of methods for the inference and experimental confirmation of microbial association networks in cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2022, 368, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, N.; Ceniti, C.; Santoro, A.; Clausi, M.T.; Casalinuovo, F. Foodborne Pathogen Assessment in Raw Milk Cheeses. International Journal of Food Science 2020, 2020, 3616713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possas, A.; Bonilla-Luque, O.M.; Valero, A. From Cheese-Making to Consumption: Exploring the Microbial Safety of Cheeses through Predictive Microbiology Models. Foods 2021, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales-Barron, U.; Gonçalves-Tenório, A.; Rodrigues, V.; Cadavez, V. Foodborne pathogens in raw milk and cheese of sheep and goat origin: a meta-analysis approach. Current Opinion in Food Science 2017, 18, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M.; Sheehan, J.; Feng, P.C.H. Use of indicator bacteria for monitoring sanitary quality of raw milk cheeses – A literature review. Food Microbiology 2020, 85, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarchelier, P.; Fegan, N. Pathogens in Milk: Escherichia coli. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 2nd ed.; Fuquay, J.W., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2011; pp. 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati, F.; Andrighetto Ch Bottero, M.T.; Dalmasso, A. Microbial characterization of an artisanal production of Robiola di Roccaverano cheese. Journal of Dairy Science 2020, 103, 4056–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penland, M.; Falentin, H.; Parayre, S.; Pawtowski, A.; Maillard, M.-B.; Thierry, A.; Mounier, J.; Coton, M.; Deutsch, S.-M. Linking Pélardon artisanal goat cheese microbial communities to aroma compounds during cheese-making and ripening. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2021, 345, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellino, S.N.; Benson, D.R. The good, the bad, and the ugly: tales of mold-ripened cheese. In Cheese and Microbes, 1st ed.; Donnelly, C.W., Ed., ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, T.P.; Evangelista, S.R.; Passamani, F.R.F.; Bertechini, R.; de Abreu, L.R.; Batistade, L.R. Mycobiota of Minas artisanal cheese: Safety and quality. International Dairy Journal 2021, 120, 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant'Anna, F.M.; Wetzels, S.U.; Cicco, S.H.S.; Figueiredo, R.C.H.; Sales, G.A.; Figueiredo NCh Nunes, C.A.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Mann, E.; Wagner, M.; Souza, M.R. Microbial shifts in Minas artisanal cheeses from the Serra do Salitre region of Minas Gerais, Brazil throughout ripening time. Food Microbiology 2019, 82, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig-Sagués, A.X.; Molina, A.P.; Hernández-Herrero, M.M. Histamine and tyramine-forming microorganisms in Spanish traditional cheeses. European Food Research and Technology 2002, 215, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, N.; Mayo, B.; Fernández, E.; Fresno, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E.; Castro, J.M. Molecular study of Geotrichum strains isolated from Armada cheese. Food Microbiology 2013, 36, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangallo, D.; Šaková, N.; Koreňová, J.; Puškárová, A.; Kraková, L.; Valík, Ľ.; Kuchta, T. Microbial diversity and dynamics during the production of May bryndza cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2014, 170, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šaková, N.; Sádecká, J.; Lejková, J.; Puškárová, A.; Koreňová, J.; Kolek, E.; Valík, Ľ.; Kuchta, T.; Pangallo, D. Characterization of May bryndza cheese from various regions in Slovakia based on microbiological, molecular and principal volatile odorants examination. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2015, 54, 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kačániová, M.; Kunová, S.; Štefániková, J.; Felšöciová, S.; Godočíková, L.; Horská, E.; Nagyová, Ľ.; Haščík, P.; Terentjeva, M. Microbiota of the traditional Slovak sheep cheese “Bryndza”. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences 2019, 9, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sádecká, J.; Čaplová, Z.; Tomáška, M.; Šoltys, K.; Kopuncová, M.; Budiš, J.; Drončovský, M.; Kolek, E.; Koreňová, J.; Kuchta, T. Microorganisms and volatile aroma-active compounds in bryndza cheese produced and marketed in Slovakia. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2019, 58, 382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Koňuchová, M.; Valík, Ľ. Modelling the Radial Growth of Geotrichum candidum: Effects of Temperature and Water Activity. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutrou, R.; Guéguen, M. Interests in Geotrichum candidum for cheese technology. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2005, 102, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich-Wyder, M.T.; Arias-Roth, E.; Jakob, E. Cheese yeasts. Yeast 2019, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliskases-Lechner, F.; Guéguen, M.; Panoff, J.M. Geotrichum candidum. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; Mcsweeney, P.L.H., McNamara, J.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2022; Volume 4, pp. 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, B.; Rodríguez, J.; Vázquez, L.; Flórez, A.B. Microbial Interactions within the Cheese Ecosystem and Their Application to Improve Quality and Safety. Foods 2021, 10, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, V.; Chieffi, D.; De Angelis, M. Fresh pasta filata cheeses: Composition, role, and evolution of the microbiota in their quality and safety. Journal of Dairy Science 2022, 105, 9347–9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valík, Ľ.; Ačai, P.; Medveďová; A. Application of competitive models in predicting the simultaneous growth of Staphylococcus aureus and lactic acid bacteria in milk. Food Control 2018, 87, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobacz, A.; Kowalik, J.; Zulewska, J. Determination of the survival kinetics of Salmonella spp. on the surface of ripened raw milk cheese during storage at different temperatures. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2020, 55, 610–618. [Google Scholar]

- Ačai, P.; Valík, Ľ.; Medveďová, A. One- and Two-Step Kinetic Data Analysis Applied for Single and Co-Culture Growth of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Lactic Acid Bacteria in Milk. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valík, Ľ.; Görner, F.; Sonneveld, C. Fermentácia (kysnutie) ovčieho hrudkového syra v podmienkach salašnej výroby (Fermentation of ewe's lump cheese under conditions of artisan production). Chov oviec a kôz (Breeding of sheep and goats) 2004, 24, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ačai, P.; Valík, Ľ.; Medveďová, A.; Rosskopf, F. Modelling and predicting the simultaneous growth of Escherichia coli and lactic acid bacteria in milk. Food Science and Technology International 2016, 22, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ačai, P.; Medveďová, A.; Mančušková, T.; Valík, Ľ. Growth prediction of two bacterial populations in co-culture with lactic acid bacteria. Food Science Technology International 2019, 25, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šipošová, P.; Koňuchová, M.; Valík, Ľ.; Medveďová, A. Growth dynamics of lactic acid bacteria and dairy microscopic fungus Geotrichum candidum during their co-cultivation in milk. Food Science Technology International 2020, 27, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveďová, A.; Kočiš-Kovaľ, M.; Valík, Ľ. Effect of salt and temperature on the growth of Escherichia coli PSII. Acta Alimentaria 2021, 50, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 15214. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs. Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Mesophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Colony-Count Technique at 30 °C. International Organization of Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- EN ISO 21527-1. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs - Horizontal method for the enumeration of yeasts and moulds - Part 1: Colony count technique in products with water activity greater than 0.95. International Organization of Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- National Standard Method F23. Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae by the Colony Count Technique, Standards Unit, Evaluations and Standards Laboratory, Health Protection Agency, 2005, p. 23. (n.d.).

- EN ISO 6888-1. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs. Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species). Part 1: Technique Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium. International Organization of Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Huang, L. Optimization of a new mathematical model for bacterial growth. Food Control 2013, 32, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, B.; Dalgaard, P. Modelling and predicting the simultaneous growth of Listeria monocytogenes and spoilage micro-organisms in cold-smoked salmon. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2004, 96, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkowsky, D.A.; Olley, J.; McMeekin, T.A.; Ball, A. Relationship Between Temperature and Growth Rate of Bacterial Cultures. Journal of Bacteriology 1982, 149, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.L. Predictive food microbiology. Trends in Food Sciences and Technology 1993, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwietering, M.H.; Jongenburger, I.; Rombouts, F.M.; Van't Riet, K. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1990, 56, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L. Mathematical modeling and validation of growth of Salmonella Enteritidis and background microorganisms in potato salad - One-step kinetic analysis and model development. Food Control 2016, 68, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, J.; Pin, C.; Ross, T. Validating and comparing predictive models. International Journal of Food Microbiology 1999, 48, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Hwang, C.; Liu, Y.; Renye, J.; Jia, Z. Growth competition between lactic acid bacteria and Listeria monocytogenes during simultaneous fermentation and drying of meat sausages - A mathematical modeling. Food Research International 2022, 158, 111553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalcanton, F.; Carrasco, E.; Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; Posada-Izquierdo, G.D.; Falcão de Aragão, G.M.; García-Gimeno, R.M. Modeling the Combined Effects of Temperature, pH, and Sodium Chloride and Sodium Lactate Concentrations on the Growth Rate of Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014. Journal of Food Quality 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveďová, A.; Šipošová, P.; Mančušková, T.; Valík, Ľ. The effect of salt and temperature on the growth of Fresco culture. Fermentation 2019, 5, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, S.; Ramos, I.M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Poveda, J.M.; Seseña, S.; Palop, M.L. Lactic acid bacteria as biocontrol agents to reduce Staphylococcus aureus growth, enterotoxin production and virulence gene expression. LWT 2022, 170, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, O.; Hosono, A. Immediate effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus on the intestinal flora and fecal enzymes of rats and the in vitro inhibition of Escherichia coli in coculture. Journal of Dairy Science 2000, 83, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveďová, A.; Liptáková, D.; Hudecová, A.; Valík, Ľ. Quantification of the growth competition of lactic acid bacteria: a case of co-culture with Geotrichum candidum and Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Chimica Slovaca 2008, 1, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Aldarf, M.; Fourcade, F.; Amrane, A.; Prigent, Y. Diffusion of lactate and ammonium in relation to growth of Geotrichum candidum at the surface of solid media. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2004, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveďová, A.; Havlíková, A.; Lehotová, V.; Valík, Ľ. Staphylococcus aureus 2064 growth as affected by temperature and reduced water activity. Italian Journal of Food Safety 2019, 8, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canon, F.; Nidelet, T.; Guédon, E.; Thierry, A.; Gagnaire, V. Understanding the Mechanisms of Positive Microbial Interactions That Benefit Lactic Acid Bacteria Co-cultures. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šipošová, P.; Koňuchová, M.; Valík, Ľ.; Trebichavská, M.; Medveďová, A. Quantitative Characterization of Geotrichum candidum Growth in Milk. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T. Indices for performance evaluation of predictive models in food microbiology. Journal of Applied Microbiology 1996, 81, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).