1. Introduction

Anemia is a common complication of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and can significantly impact the quality of life of affected individuals. Treatment for anemia in CKD has focused on administering erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESA) and iron supplementation. Mircera (methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta) and Aranesp (darbepoetin alfa) are two of the most commonly used ESAs. They work by increasing the production of red blood cells, which helps alleviate anemia symptoms. However, these drugs can also increase the risk of cardiovascular and thromboembolic events, particularly in patients with advanced CKD [

1,

2].

Recently, new treatments offer additional options for managing erythropoietin (EPO) deficiency anemia in CKD. One such treatment is modifying conventional iron therapy [

3]. Intravenous iron, oral iron, and erythropoietin-iron combination therapy have all been used to improve iron stores and support red blood cell production. However, oral ferrous (Fe2+) compounds can cause gastrointestinal side effects, and intravenous iron (IV) therapy can be associated with a risk of anaphylaxis [

4]. Therefore, newer formulations of IV iron utilising slow release and low dosages are being considered.

Another novel approach is the hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (HIF-PHI), Roxadustat and Daprodustat. HIF-PHIs increase endogenous erythropoietin production and red blood cell production, which can improve the symptoms of anemia without the risks associated with exogenous erythropoietin. Clinical trials; OLYMPUS and DOLOMITIES have shown that Roxadustat is effective in treating anemia of various comorbidity, with a favourable safety profile [

5,

6].

One of the most unmet needs in EPO-deficiency is the identification of causative genetic mutations that can facilitate personalised medicine. EPO-deficiency encompasses a broad range of genetic involvement. However, molecular diagnosis needs to be established in clinical setting to avoid unnecessary costly and invasive treatments. Out of the many genes involved in this mechanism, we focused on erythropoietin gene (EPO), Interleukin-β gene (IL-β) and hypoxia-inducible factor gene (HIF).

This review article focuses on the three approaches in treating EPO-deficient anemia in CKD. We will discuss current treatment options; practical advantages and shortcomings, precision molecular medicine targeting genetic components, and emerging alternative therapy.

2. Overview of Pharmacogenetics

Pharmacogenetics focuses on the influence of single gene polymorphism on drug response. It speaks of the variation in how people respond to medicinal therapy, which is a rapidly expanding field in molecular biology and clinical medicine. With the advent of genetic testing, pharmacogenetics, a word that gained popularity in the 1930s, has now been rediscovered [

7]. Up to 95% of the variability in treatment response can be attributed to genetic variables. However, other elements including culture, behaviour, and environment may significantly impact how many of these variants vary. When members of the same family with the same inherited condition respond differently to the same medical treatment, this is an example of genetic factors playing a role in the process [

8].

A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), often known as a genetic variation, is a change in the nucleotide sequence that affects the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic characteristics of medications [

9]. Pharmacogenomics testing are designed to find patients who respond or do not respond to treatment, interact with other drugs, experience side effects, or need their dosage adjusted [

8]. Pharmacogenetics has become a vital subject due to the idea of individualized medication. In the field of medicine known as "personalized medicine," treatment choices are based on the entire patient's data, taking into account their individuality. This data consists of genetic, environmental, and quality of life information.

3. Impact of Iron Deficiency and Treatment

Chronic kidney disease is largely considered an inflammatory disease which affect hematopoietic function and pathway [

10]. There are two types of iron deficiency which disrupts the EPO production, namely absolute and relative [

11]. Absolute iron deficiency occurs when there is diminished level of iron in the body due to halted iron absorption or severe blood loss. Individual will typically present with decreased iron, ferritin, transferrin saturation and increased total iron binding capacity (TIBC). Relative iron deficiency is on the contrary due to inefficient use of stored iron which occurs due to inflammation, genetic mishap or EPO deficiency [

4].

Iron supplementation therapy typically given in the form of iron-containing oral supplements such as Ferric maltol; non salt based iron. Ferric maltol has been shown to be more effective than other iron salts, with fewer side effects in its phase III trial. Evidences from the 1-year AEGIS-CKD [

12], trial shows this compound is able to normalise and sustain Hb level with much lower rate of gastrointestinal disorders as compared to ferrous sulfate [

13]. Although this compound has been licensed in US and Europe for iron-deficiency anemia [

14], its efficacy and safety profile is still under assessment in CKD patients. Newer intravenous iron supplementation treatments such as Ferric Carboxymaltose (FCM), also known as "Ferinject" or "Injectafer" and Ferric Derisomaltose (FDM) also known as Monofer were formulated to improve safety and reduce hypersensitivity reaction. FCM and FDM is a highly-concentrated form of iron that utilizes a unique iron-carbohydrate complex and can be administered quickly in a single or few IV doses [

15,

16]. However, it is important to note that the use of IV iron in patients with CKD requires careful monitoring and close collaboration between the patient's nephrologist and hematologist. This is because patients with CKD may have other underlying conditions that can affect the absorption and utilization of iron [

17]. Additionally, patients with advanced CKD may have difficulty excreting excess iron, which can lead to iron overload and further complications. In the case of functional iron deficiency which is usually caused by underutilization of EPO due to hepcidin upregulation, IV iron may cause iron overload toxicity and enhance oxidative stress. In an attempt to compare the safety profile of FCM, FDM and iron sucrose in terms of hypersensitivity using robust and reliable method, Pollock and Biggar [

18] concluded the risk of hypersensitivity in FDM is relatively lower compared to the other two compounds.

4. Erythropoietin

In the normal kidney, renal EPO-producing cells (REPs) are peritubular interstitial fibroblast-like cells and pericytes [

19] which control EPO gene expression primarily through the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway [

20]. EPO acts as the primary hormone regulator of erythrocytes production or erythropoiesis in the bone marrow. It is also being synthesized by the liver [

21] and the brain, however the amount synthesized by these tissues alone is insufficient to maintain adequate erythropoiesis [

22]. According to Nangaku

et al [

23], EPO deficient may be due to constant inflammatory cell infiltration. At cellular level, production of EPO in REPs is regulated by the number of EPO-producing cells by “on’’ or “off’’ mechanism, which changes explicitly responding to hypoxia and or anemia . Under normal conditions, the REPs possess EPO-producing ability but do not produce EPO (OFF-REPs). In healthy individuals, when oxygen supplies decrease or oxygen demands rise, the OFF-REPs begin to produce EPO through HIF-mediated EPO-gene transcription (ON-REPs) [

24]. In CKD patients, however, sustained inflammation in renal fibrosis become the major contributor to EPO deficiency as fibrotic kidneys with damaged REPS transform into myofibroblasts, causing the concomitant repression of their ability to produce EPO [

24]. Pathophysiology of inflammation and linked genetic factors.

5. Pathophysiology of inflammation and linked genetic factors

Serum erythropoietin in anaemic patients without renal failure but inflammation due to other reasons was lower as compared to levels in similarly anaemic patients without inflammation demonstrated the relationship between inflammation and impaired erythropoiesis [

25,

26]. Signalling mediators of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways such as GATA-2 , NF-KB, TGFβ/Smad often play a role in direct and indirect suppression effect on EPO-regulatory mechanism [

26,

27].

GATA family's transcription factor, GATA-2, binds to the GATA-motif in the vicinity of the transcriptional initiation site of the EPO promoter in the -30 region [

28]. Some evidence showed that functional activation of the GATA-2 signalling pathway by pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to impairment of EPO production. Observations from a study revealed that GATA-2 suppresses EPO gene expression in cell culture. When the TATA element was transfected, EPO gene promoter activity rose 2.5-fold, however pro-inflammatory cytokines decreased EPO gene promoter activity in cells transfected with pGATAwt relative to control cells [

27]. This result suggests that signal transduction pathways of the cytokines may be modulated by GATA-2 causing lower production of EPO in inflammation conditions.

NFκB signalling is also responsible for negative regulation of EPO gene transcription due to competition with co-activators of hypoxia-induced EPO gene expression [

29]. The activity of transcription factor NF-kB is closely related to the processes of activation, proliferation and cells differentiation into myofibroblasts [

24]. Souma

, et al. [

24] revealed that the sustained activation of NFκB signals in renal erythropoietin-producing cells results in a phenotypic transition. These findings showed that despite NFκB signal being important for repressing erythropoietin production, it is also attributed to transforming EPCs to myofibroblasts.

Another major signalling pathway involved in the pathogenesis of fibrosis with concomitant loss of EPO is TGFβ/Smad3 [

30]. Activated TGFβ functions via Smad-dependent and independent signalling pathways as a major pathway in many pathophysiological processes of kidney diseases [

31]. It is well-recorded Smad3 is a strong downstream mediator of renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy [

32] hypertensive nephropathy [

33], obstructive kidney disease and glomerulonephritis [

34]. In contrast, Smad2 acts as reno-protective by competing with Smad3 signalling through phosphorylation and nuclear translocation [

33].

Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammation-related indicators, define renal fibrosis in CKD and loss of EPO production [

35]. Gene transcription and cytokine release may be affected by cytokine gene polymorphisms, which could modulate the renal fibrosis and EPO-deficient anemia progression risk [

36].

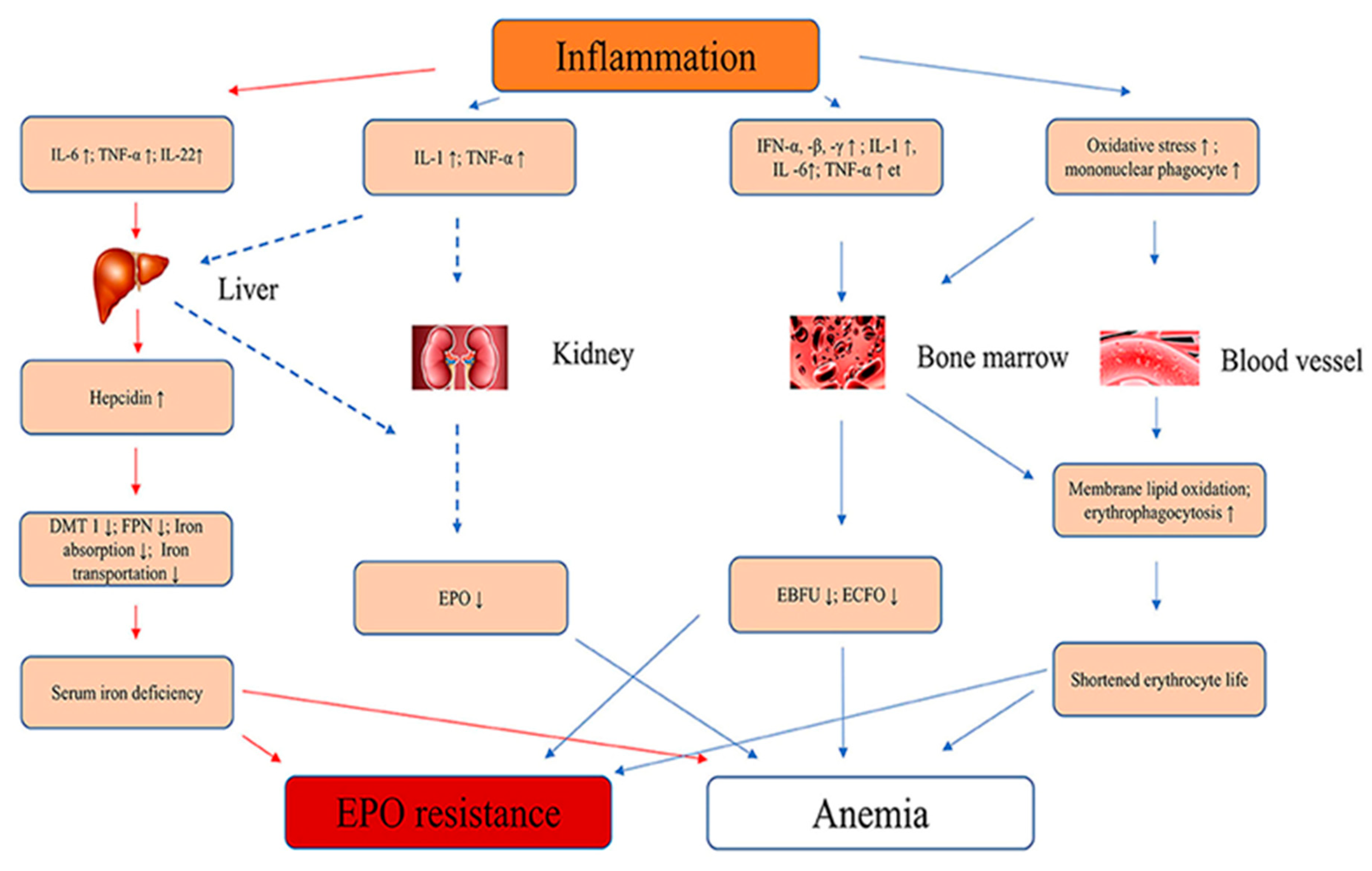

Figure 1 summarise the pathophysiology of inflammatory cytokine that causes anemia and EPO resistance.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene is found in chromosome 7p21, and consists of five exons and four introns. IL-6 has several polymorphisms in the promoter region -174 G to C and -597 G to A. IL-6 is rapidly expressed in a highly transient manner during inflammation. Mutation at rs2228145 has been associated to renal disease due to inflammation and causes renal fibrosis [

37]. Previous study in dialysis patients by Sharples

, et al. [

38] have shown the influence of IL-6 (-174 G/C) polymorphism on ESAs responsiveness. They observed that there was a significantly higher ESAs requirement in the GG and GC ACE genotypes compared with the CC group, which remained an independent association.

Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by immune cells and adipocytes. In CKD, there is an increased production of TNF as a result of inflammation and oxidative stress. Elevated TNF levels can have multiple effects on the body, including the suppression of EPO production by the kidneys [

10]. TNF-α inhibits the production of EPO in the kidneys by interfering with the transcription of the EPO gene and by promoting the destruction of EPO-producing cells. This inhibitory effect of TNF on EPO production contributes to the development of renal anemia in CKD patients [

39].

The IL-1 gene cluster on chromosome 2q contains 3 related genes within a 430-kb region, IL- 1α, IL-1B, and IL-1RN, which encode the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β The IL-1β-511C/T (rs1143627) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) has been associated with a variety of diseases in which inflammation plays an important role [

40]. Jeong

, et al. [

41] reported that the IL-1β-511CC genotype was significantly associated with lower ERI values in haemodialysis patients. In this study, patients with the IL-1β-511 TT genotype also showed a significantly higher mean IL-1β level (0.9 ± 0.6 pg/mL), compared to those with the IL-1β-511CC genotype (0.3 ± 0.3 pg/mL; P = 0.02) [

41].

6. Erythropoietin Treatment and Resistance

According to KDIGO guidelines (2013) [

42], it is recommended that for anemic patients with CKD not on dialysis, Erythropoietin Stimulating Agent (ESA) treatment should be considered when the haemoglobin level is < 10 g/dL. It must be individualized based on the rate of fall of haemoglobin, prior response to iron therapy, the risk of needing a transfusion, the risks related to ESA therapy, and the presence of symptoms attributable to anemia [

43]. A third generation ESA; darbepoetin alpha that is modified from EPO by insertion of a large pegylation chain to make it longer acting, called continuous EPO receptor activator has been approved for marketing [

44]. Although ESA has been said to improve patient’s quality of life, reduced hematopoietic response to ESA treatment has been associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes [

45,

46]. Patient with heart condition is often linked to higher erythropoietin resistance [

45,

47]. Safety concerns regarding ESA therapies have paved the way for the development of a new class of drugs.

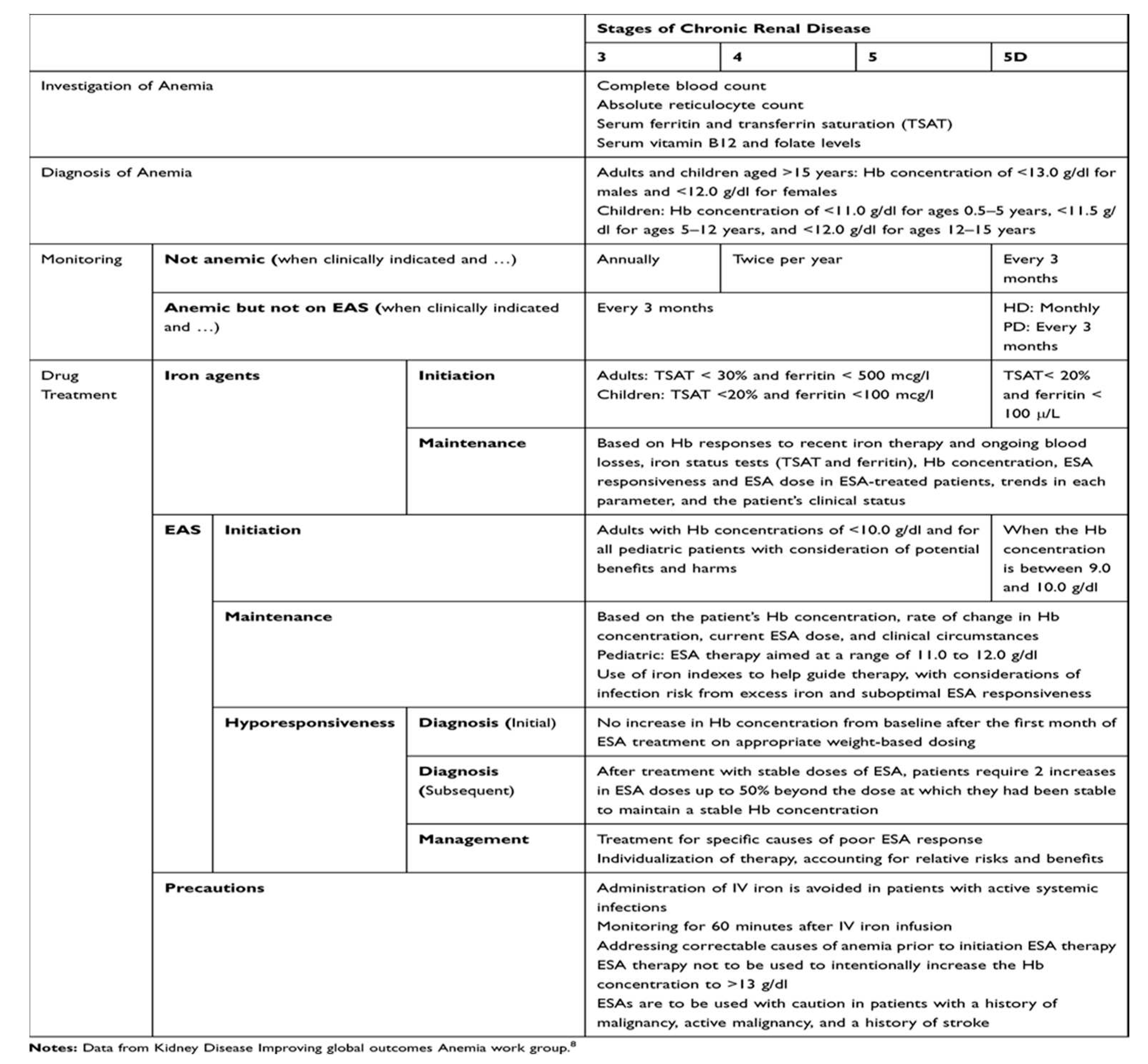

Table 1 lists the current treatment approach [

8].

7. Precision Medicine in EPO Deficiency and Treatment Resistance

There has been substantial amount of interest in creating a gene therapy approach to deliver EPO in a way single infusion of the EPO gene would guarantee EPO delivery for long term. An attempt was made and the investigators manage to establish the hypoxia regulatory mechanism in line with homeostatic system giving it a natural approach. They have also spelled out the promotor OBHRE region increases the hematocrit level gradually and safely in the relevant anemic mouse model [

48].

In a different approach, EPO from human cells (hEPO) was manufactured to directly secrete EPO without any further formulation to reduce risk of antibody production. This study was carried out by Lippin

, et al. [

49] using Biopump transduced with the clinical-grade Ad-MG/EPO-1 (Ad5 E1/E3 deleted) expressing hEPO yielded a promising result.

However, it is important to note that gene therapy is still an emerging field and is not yet widely available for clinical use. Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of gene therapy for various genetic conditions, including EPO deficiency caused by mutations in the EPO gene.

8. Genetic Factors of EPO Deficiency and Treatment Resistance

The human EPO gene is located on chromosome 7q21 which is well known for harbouring increased susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy [

50]. Endogenous and recombinant EPO stimulates erythropoiesis by binding to the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR). The mRNA alternative splicing can give rise to the soluble form of the receptor (sEpoR) which lacks the transmembrane domain. sEpoR acts as an antagonist of EPO due to its higher affinity for EPO which can lead to resistance towards ESA. Moreover, in vitro experiments by Tong

et al [

51] have shown that a single nucleotide polymorphism from G to T in EPO promoter (rs1617640) can alter the EPO mRNA levels [

52]. The predisposition in this promoter region might also contribute to EPO-deficiency in pre-dialysis patients therefore needs to be investigated.

Pro-inflammatory genes are widely studied for their role in anemia of chronic diseases and known to cause ESA resistance [

53]. Jeong

, et al. [

41] reported that the IL-1β-511CC genotype was significantly associated with lower erythropoietin resistance values in haemodialysis patients. Polymorphism in this region has shown to reduce EPO mRNA expression and erythropoietin secretion in the human hepatoma cell lines. According to Nangaku and Eckardt [

23], this EPO deficient may be due to constant inflammatory cell infiltration led to decreased production of EPO. Several pathways have been identified for their role in attributing the inflammatory conditions in renal fibrosis and eventually leads to EPO deficiency anemia (

Figure 2).

The Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF) was first discovered during the identification of hypoxia responsive element (HRE) in the erythropoietin gene in 1991 [

54]. Besides regulating oxygen by signalling EPO gene, it also plays a role in stem cell maintenance, growth factor signalling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and metabolism [

55,

56]. Under normoxic conditions, HIF is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded, a process primarily controlled by a family of oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases (PH). However, hypoxia triggers stabilization of HIF-1α, gets translocated from cytoplasm to nucleus and heterodimerizes with HIF-1β which protects it from VHL-mediated proteasomal degradation. Transcriptionally active HIF complex formed by heterodimerization associates with HRE in the regulatory regions of target genes and binds to transcriptional coactivators to induce EPO gene expression [

57,

58].

9. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors (HIF-PH)

HIF-PH inhibitors target the activity of prolyl hydroxylase (PH) enzymes, which play a key role in regulating the stability and activity of HIF [

59]. PHs belong to the iron and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenase superfamily and it has several identified isoforms; PH 1, 2 and 3 [

60]. It exhibits overlapping but different tissue expression levels, and their subcellular localisation varies [

61]. PH 2 is often associated with HIF-1α in normoxia regulation and any loss of function towards PH 2 causes familial erythrocytosis [

62]. PH 3 on the other hand, is the regulator of HIF-2α and found to be overexpressed in hypoxic conditions [

63]. There have been several recent studies investigating the potential use of HIF-PH inhibitors as a treatment for CKD [64-66]. By blocking the activity of these enzymes, HIF-PH inhibitors can increase the activity of HIF and trigger the cellular responses to low oxygen levels that it regulates and stimulate erythrocyte production, potentially alleviating symptoms of anemia .

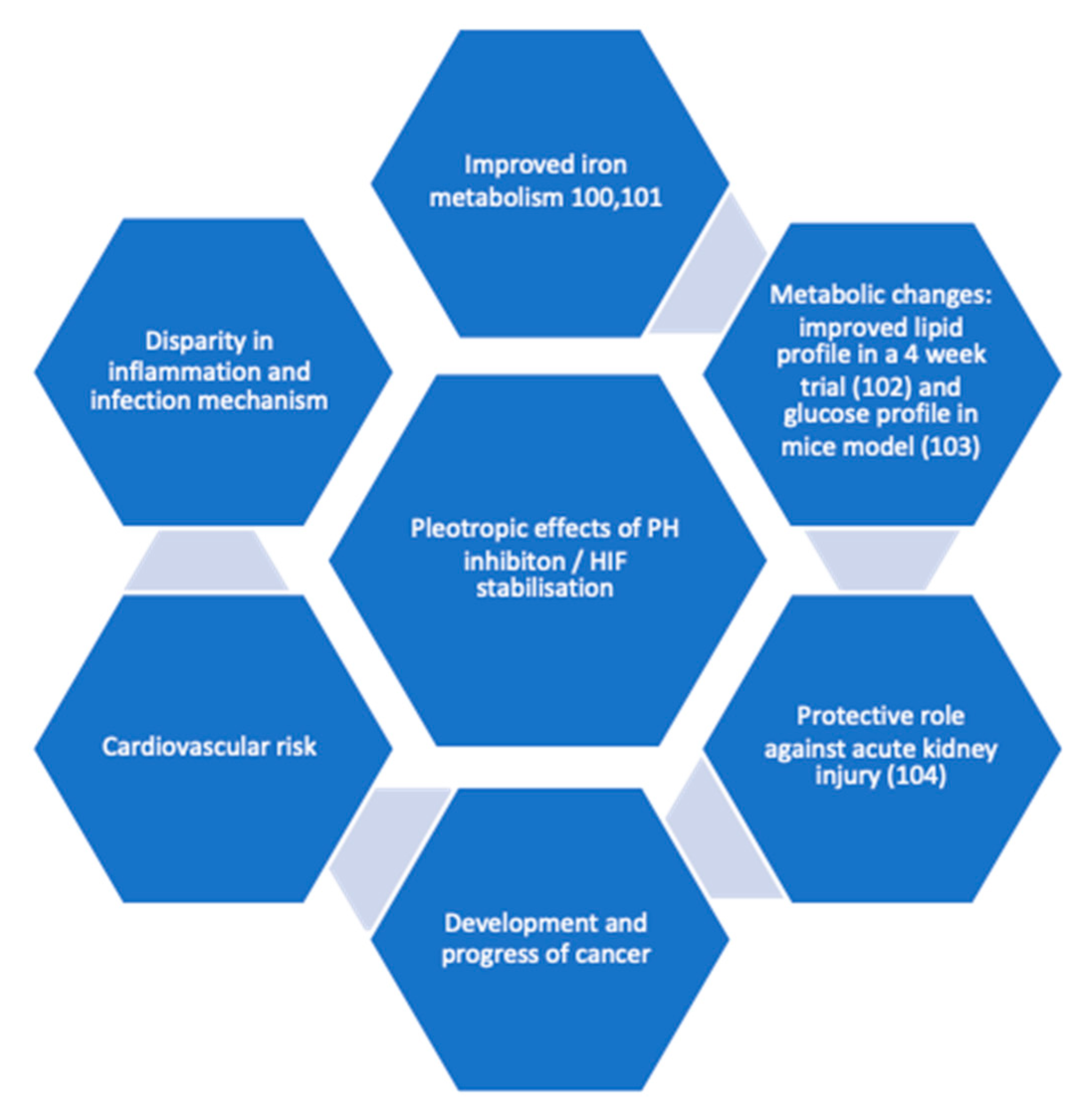

CKD is associated with inflammation, which in turn causes functional iron deficiency and ESA hypo-responsiveness. HIF is believed to improve these two factors since it plays a crucial role in regulation of cellular response to low oxygen levels and reportedly reduced serum hepcidin [

66]. It was also noted by researchers that HIF-1α and its isoform 2α has a role to play in clear cell renal carcinoma (ccRC) but its functional significance is not clear in the development stage [

67]. Earlier investigation revealed tumour cells often present with over expression of HIF-1α. The overexpression of either of the isoform was also associated with cardiomyopathy [

68]. However recent evidence shows these two isoforms have opposing outcomes [

69]. Pleotropic effects (

Figure 2) of HIF also lead to metabolic changes investigation, for instance improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in mouse model was observed by Sugahara

et al [

70]. Both isoforms for HIF are shown to be expressed in innate immunity [

71] and HIF-1α in adaptive immunity [

72].

In clinical trials, Roxadustat users experienced higher rates of upper respiratory infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections than the control group, which may be related to immunological regulation brought on by PH inhibition [

5]. While it is true that HIF-PHIs have been tolerated well in clinical trials, there may still be some worries on copper toxicity. Nakamura

, et al. [

73] first describe four cases of individuals with renal anemia who had elevated serum copper levels. HIF-PHI medication, which returned to normal following switching from HIF-PHI to darbepoetin alfa, indicates that HIF-PHI may be linked to elevated serum copper levels. Since genomewide analysis of HIF transcriptome shows at least 500-1000 genes are under the control of HIF, stabilising this factor to improve oxygen sensing mechanism might affect other complex pathophysiology in the long term.

Fishbane [

5,

74] has reported in his phase 3 trial namely OLYMPUS and ROCKIES that regardless of inflammation, Roxadustat improved haemoglobin level in comparison to placebo and epotin alfa group. Daprodustat or Duvroq is another potent HIF-PH 1-3 inhibitor which was first approved in Japan for renal anemia treatment on June 2020 (GlaxoSmithKline) [

75]. However, this molecule is still under investigation in many countries (NCT03029247; 205665; ASCEND-BP and NCT03457701; 201771; ASCEND-Fe) and FDA after reluctancy, finally approved it in February 2023. There are several other HIF-PH inhibitors are being developed and studied in order to target several patient cohorts for example dialysed dependent patients. Vadadustat (AKB-6548) developed by Akebia therapeutics, inhibits all 3 PHs with increased affinity towards PHD3 [

76]. Molidustat and enarodustat are also under phase III clinical trial by different pharmaceutical companies with considerable efficacy and safety profile in phase 2 trial. Several review articles have summarised the phase 3 clinical trial evaluating efficacy of HIF-stabilisers for non-dialysis population and the table can be found in [

77] and [

78].

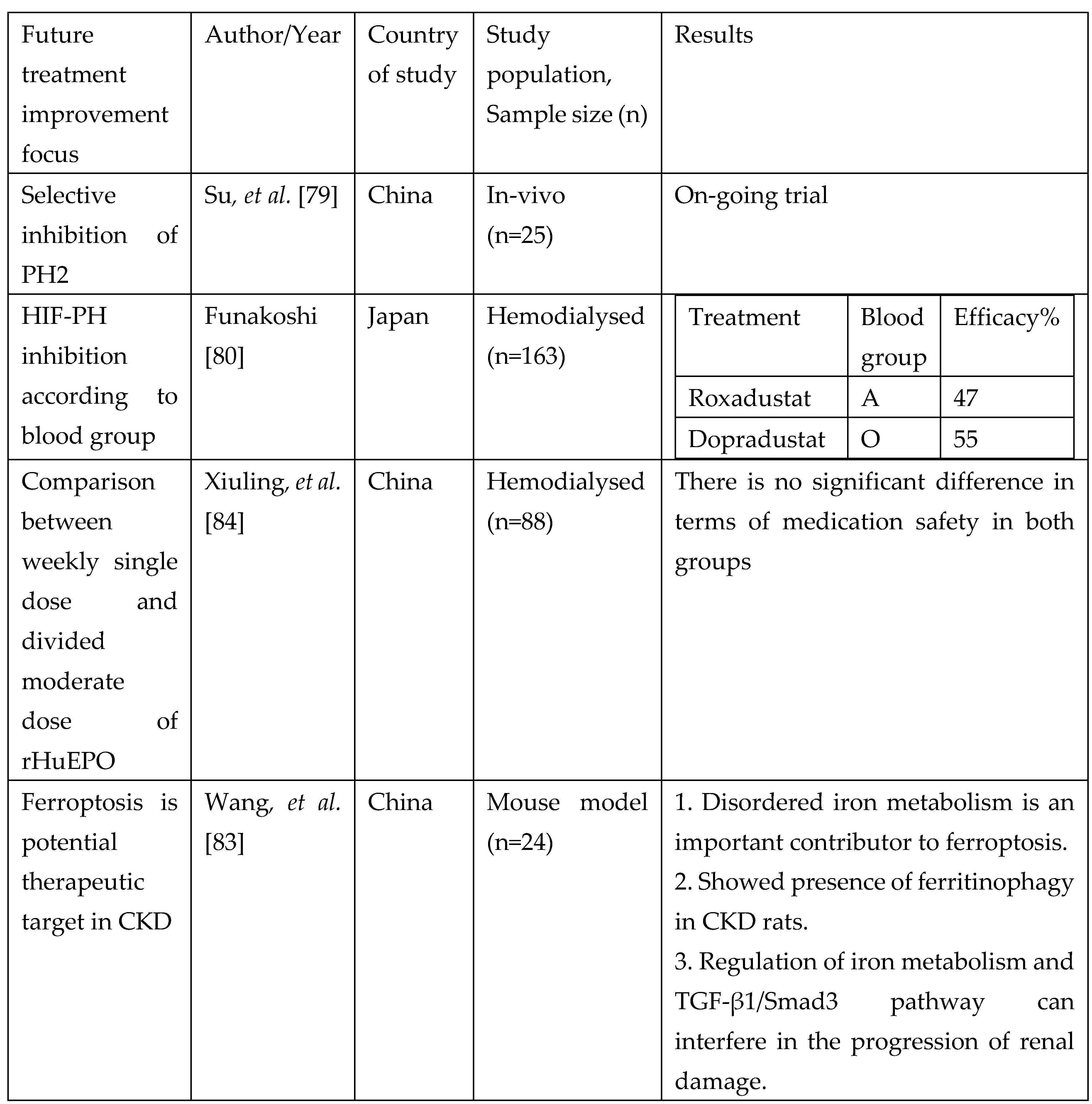

10. Future Treatment Approachess

The latest molecule that is being researched is known as Tetrahydropyridin-4-ylpicolinoylglycines and this target to inhibit PH-2 [

79]. This targeted approach might improve selective binding and reduce some of the undesirable pleotropic effect of HIF stabilisers. In the context of personalised medicine, association between ABO blood group and HIF PH showed that Roxadustat have a better therapeutic efficacy in A blood group and Daprodustat in O blood group hemodialysed individuals [

80]. While recombinant EPO treatment is not entirely disadvantageous to all patients, a more personalised approach treatment target will be beneficial. For instance according to Joksimovic Jovic

, et al. [

81], elevated serum ferritin, increased catalase activity contributes to short acting EPO resistance. Oxidative stress, poor nutrition, chronic inflammation and vitamin D deficiency increase risk of long-acting EPO resistance. Kidney cells are prone to iron overload which causes ferroptosis; regulated cell death due to iron overload. This aggravates CKD and renal anemia causing irregular iron metabolism [

82]. It is believed that anemia in CKD develops as the number of renal EPO-producing cells and the production of fibroblast-derived erythropoietin is decreased despite the tissue hypoxia caused by anemia . As a result, EPO deficiency anemia becomes the major cause of anemia in CKD [

19]. Wang

, et al. [

83] attempted to demonstrate ferroptosis could be a novel target approach in delaying CKD which eventually led to renal anemia.

11. Potential Approach from the Perspective of Drug Design and Development for Treatment Resistance in Erythropoietin Deficiency Anemia : Receptor modification

Receptor modification can occur through a variety of mechanisms, such as changes in the receptor's gene expression, post-translational modifications (such as phosphorylation, glycosylation, or acetylation), or alterations in the receptor's structure or conformation. These modifications can affect the receptor's sensitivity or specificity to certain ligands (molecules that bind to the receptor), its signalling efficiency or duration, or even its ability to interact with other proteins or downstream effectors. For example, the EpoR can be engineered to have a higher affinity for EPO, allowing it to bind EPO more effectively and stimulate erythropoiesis more efficiently. Alternatively, the EpoR can be modified to have a longer half-life, which would prolong its activity and allow it to stimulate erythropoiesis for a longer period of time. Utilizing computational techniques to model the erythropoietin receptor and perform molecular simulations. These simulations can help identify potential binding sites, predict conformational changes, and assess the impact of specific modifications on receptor function [

85].

12. Conclusions

EPO-deficiency is a complex mechanism involving many pathways. Comorbidities such as dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes are also contributing factor to this condition. Besides that, concomitant drug usage such as ACE inhibitors, statins, diuretics, anti-platelets, oral diabetic agents and so on are also widely investigated as potential biomarkers. The identified or known pathway is being extensively researched to provide a more personalised treatment and achieve good treatment efficiency. For example, drugs that target specific molecular pathways involved in EPO production or response. These targeted therapies may be identified through genetic testing and personalized treatment plans. Investigation on the biomarkers is also on the rise and genetic contribution to the pathophysiology should also be investigated. Some genetic polymorphism and expression may result in variation of individual response to ESA treatment. Delivering EPO based on physiological demand will also reduce adverse events and unnecessary cost for the patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nava Yugavathy, Bashar Mudhaffar Abdullah and Hasniza Zaman Huri; writing—original draft preparation, Nava Yugavathy; writing—review and editing, Bashar Mudhaffar Abdullah, Hasniza Zaman Huri, Lim Soo Kun, Abdul Halim Bin Abdul Gafor, Wong Muh Geot, Sunita Bavanandan, Wong Hin Seng.; supervision, Hasniza Zaman Huri, Lim Soo Kun.; project administration, Hasniza Zaman Huri, Lim Soo Kun.; funding acquisition, Hasniza Zaman Huri, Lim Soo Kun, Abdul Halim Bin Abdul Gafor, Wong Muh Geot, Sunita Bavanandan, Wong Hin Seng.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), FP020-2016.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bonomini, M.; Del Vecchio, L.; Sirolli, V.; Locatelli, F. , New Treatment Approaches for the Anemia of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drüeke, T.B.; Massy, Z.A. , Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents and Mortality. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.-H.; Ho, Y.; Tarng, D.-C. , Iron Therapy in Chronic Kidney Disease: Days of Future Past. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, E.K.; Kapitsinou, P.; Pergola, P.E.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Jalal, D.I. , Iron Deficiency in Chronic Kidney Disease: Updates on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbane, S.; El-Shahawy, M.A.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Pham van, B.; Houser, M.T.; Frison, L.; Little, D.J.; Guzman, N.J.; Pergola, P.E. , OLYMPUS: A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, International Study of Roxadustat Efficacy in Patients with Non-Dialysis-Dependent (NDD) CKD and Anemia [Abstract TH-OR023]. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, J.; Andric, B.; Tataradze, A.; Schömig, M.; Reusch, M.; Valluri, U.; Mariat, C. , Roxadustat for the treatment of anaemia in chronic kidney disease patients not on dialysis: a Phase 3, randomized, open-label, active-controlled study (DOLOMITES). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1616–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.A. , Personalizing medicine with clinical pharmacogenetics. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, J.T.; Lopez, D. , Pharmacogenetics: An Important Part of Drug Development with A Focus on Its Application. Int. J. Biomed. Investig. 2018, 1, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Ho, R.H. , Interindividual and interethnic variability in drug disposition: polymorphisms in organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1; SLCO1B1). Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Xu, G. , A Novel Choice to Correct Inflammation-Induced Anemia in CKD: Oral Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor Roxadustat. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, N.; Takasawa, K. , Impact of Inflammation on Ferritin, Hepcidin and the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, P.E.; Kopyt, N.P. , Oral Ferric Maltol for the Treatment of Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Patients With CKD: A Randomized Trial and Open-Label Extension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 78, 846–856.e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolkien, Z.; Stecher, L.; Mander, A.P.; Pereira, D.I.A.; Powell, J.J. , Ferrous Sulfate Supplementation Causes Significant Gastrointestinal Side-Effects in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Allen, S.; Kopyt, N.; Pergola, P. , Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barish, C.F.; Koch, T.; Butcher, A.; Morris, D.; Bregman, D.B. , Safety and Efficacy of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose (750 mg) in the Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia: Two Randomized, Controlled Trials. Anemia 2012, 2012, 172104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charytan, C.; Bernardo, M.V.; Koch, T.A.; Butcher, A.; Morris, D.; Bregman, D.B. , Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose versus standard medical care in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized, active-controlled, multi-center study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boots, J.M.M.; Quax, R.A.M. , High-Dose Intravenous Iron with Either Ferric Carboxymaltose or Ferric Derisomaltose: A Benefit-Risk Assessment. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.F.; Biggar, P. , Indirect methods of comparison of the safety of ferric derisomaltose, iron sucrose and ferric carboxymaltose in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2020, 13, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, M.J.; Haase, V.H. , Anaemia in kidney disease: harnessing hypoxia responses for therapy. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, I.; Berchner-Pfannschmidt, U.; Freitag, P.; Wotzlaw, C.; Rössler, J.; Frede, S.; Acker, H.; Fandrey, J. , Hypoxia-inducible erythropoietin gene expression in human neuroblastoma cells. Blood 2002, 100, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, M.J.; Bondurant, M.C. , Maintenance by erythropoietin of viability and maturation of murine erythroid precursor cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1988, 137, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molineux, G. ; Foote, M.A. ; Elliott, S.G., Erythropoietins and Erythropoiesis: Molecular, Cellular, Preclinical, and Clinical Biology. Birkhäuser Basel: Basel, 2005.

- Nangaku, M.; Eckardt, K.-U. , Pathogenesis of Renal Anemia. Semin. Nephrol. 2006, 26, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souma, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Moriguchi, T.; Suzuki, N.; Hirano, I.; Pan, X.; Minegishi, N.; Abe, M.; Kiyomoto, H.; Ito, S. , et al., Plasticity of Renal Erythropoietin-Producing Cells Governs Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, A.N.; Dessypris, E.N.; Goldwasser, E.; Krantz, S.B. , Blunted erythropoietin response to anaemia in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Haematol. 1987, 66, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.B.; Jones, R.J.; Piantadosi, S.; Abeloff, M.D.; Spivak, J.L. , Decreased Erythropoietin Response in Patients with the Anemia of Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ferla, K.; Reimann, C.; Jelkmann, W.; Hellwig-Bürgel, T. , Inhibition of erythropoietin gene expression signaling involves the transcription factors GATA-2 and NF-κB. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, K.M.; Duffy, S.M.; Coward, W.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Wulff, H.; Bradding, P. , The K+ Channel KCa3.1 as a Novel Target for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLOS ONE 2014, 8, e85244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmunkh, C.; Krajewski, J.; Jelkmann, W.; Hellwig-Bürgel, T. , Erythropoietin production: Molecular mechanisms of the antagonistic actions of cyclic adenosine monophosphate and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3153–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttinger, E.P. , TGF-β in Renal Injury and Disease. Semin. Nephrol. 2007, 27, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. , Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.C.K.; Zhang, H.; Kong, Y.-Z.; Tan, J.-J.; Huang, X.R.; Kopp, J.B.; Lan, H.Y. , Advanced Glycation End-Products Induce Tubular CTGF via TGF-β–Independent Smad3 Signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, X.R.; Canlas, E.; Oka, K.; Truong, L.D.; Deng, C.; Bhowmick, N.A.; Ju, W.; Bottinger, E.P.; Lan, H.Y. , Essential Role of Smad3 in Angiotensin II–Induced Vascular Fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.R.; Chung, A.C.K.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.J.; Lan, H.Y. , Latent TGF-β1 Protects Against Crescentic Glomerulonephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-M. Inflammatory Mediators and Renal Fibrosis. In Renal Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Therapies; Liu, B.-C.; Lan, H.-Y.; Lv, L.-L., Eds. Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp 381-406.

- Petreski, T.; Piko, N.; Ekart, R.; Hojs, R.; Bevc, S. , Review on Inflammation Markers in Chronic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F. , Innate Immunity System in Patients With Cardiovascular and Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, E.J.; Varagunam, M.; Sinnott, P.J.; McCloskey, D.J.; Raftery, M.J.; Yaqoob, M.M. , The Effect of Proinflammatory Cytokine Gene and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Polymorphisms on Erythropoietin Requirements in Patients on Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2006, 26, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Divvi, V.S.S.R.; Shah, T. , Assessment of Cytokine (α-TNF) with Erythropoietin and their Correlation in Pulmonary Tuberculosis with Anaemia. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, J.; Török, H.-P.; Schneider, A.; Brünnler, G.; Kopp, R.; Albert, E.D.; Stolte, M.; Folwaczny, C. , Allele 2 of the Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Gene Is Associated With Early Gastric Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4746–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-H.; Lee, T.-W.; Ihm, C.-G.; Lee, S.-H.; Moon, J.-Y. , Polymorphisms in two genes, IL-1B and ACE, are associated with erythropoietin resistance in Korean patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2008, 40, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDIGO, KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 5–14.

- Locatelli, F.; Bárány, P.; Covic, A.; De Francisco, A.; Del Vecchio, L.; Goldsmith, D.; Hörl, W.; London, G.; Vanholder, R.; Van Biesen, W. , et al., Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines on anaemia management in chronic kidney disease: a European Renal Best Practice position statement. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, A.; Haria, D.; Salifu, M.O. , Erythropoietin stimulating agents in the management of anemia of chronic kidney disease. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2008, 2, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López-Gómez, J.M.; Portolés, J.M.; Aljama, P. , Factors that condition the response to erythropoietin in patients on hemodialysis and their relation to mortality: New strategies to prevent cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Kidney. Int. 2008, 74, S75–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossert, J.; Gassmann-Mayer, C.; Frei, D.; McClellan, W. , Prevalence and predictors of epoetin hyporesponsiveness in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero Riscos, M.Á.; Guerrero-Riscos, M.Á.; Montes Delgado, R.; Montes-Delgado, R.; Seda Guzmán, M.; Seda-Guzmán, M.; Praena-Fernández, J.M.; Praena-Fernández, J.M. , Erythropoietin resistance and survival in non-dialysis patients with stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease and heart disease. Nefrología 2012, 32, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binley, K.; Askham, Z.; Iqball, S.; Spearman, H.; Martin, L.; de Alwis, M.; Thrasher, A.J.; Ali, R.R.; Maxwell, P.H.; Kingsman, S. , et al., Long-term reversal of chronic anemia using a hypoxia-regulated erythropoietin gene therapy. Blood 2002, 100, 2406–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippin, Y.; Dranitzki-Elhalel, M.; Brill-Almon, E.; Mei-Zahav, C.; Mizrachi, S.; Liberman, Y.; Iaina, A.; Kaplan, E.; Podjarny, E.; Zeira, E. , et al., Human erythropoietin gene therapy for patients with chronic renal failure. Blood 2005, 106, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.K.; Abboud, H.E.; Goddard, K.A.B.; Saad, M.F.; Adler, S.G.; Arar, N.H.; Bowden, D.W.; Duggirala, R.; Elston, R.C.; Hanson, R.L. , et al., Genome-Wide Scans for Diabetic Nephropathy and Albuminuria in Multiethnic Populations: The Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND). Diabetes 2007, 56, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Yang, Z.; Patel, S.; Chen, H.; Gibbs, D.; Yang, X.; Hau, V.S.; Kaminoh, Y.; Harmon, J.; Pearson, E. , et al., Promoter polymorphism of the erythropoietin gene in severe diabetic eye and kidney complications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 6998–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Koka, V.; Lan, H.Y. , Transforming growth factor-β and Smad signalling in kidney diseases. Nephrology 2005, 10, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.J.F.; Dias, R.S.C.; Brito Lima, J.F.d.; Salgado Filho, N.; Santos, A.M.d. , Erythropoietin resistance in patients with chronic kidney disease: Current perspectives. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2020, 13, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L.; Nejfelt, M.K.; Chi, S.M.; Antonarakis, S.E. , Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3' to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991, 88, 5680–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, L.; Semenza, G.L. , Hypoxia-Inducible Factors: Master Regulators of Cancer Progression. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L. , Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin Jr., W. G., HIFα Targeted for VHL-Mediated Destruction by Proline Hydroxylation: Implications for O<sub>2</sub> Sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, P.; Mole, D.R.; Tian, Y.M.; Wilson, M.I.; Gielbert, J.; Gaskell, S.J.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Hebestreit, H.F.; Mukherji, M.; Schofield, C.J. , et al., Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanghani, N.S.; Haase, V.H. , Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Activators in Renal Anemia: Current Clinical Experience. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariazi, J.L.; Duffy, K.J.; Adams, D.F.; Fitch, D.M.; Luo, L.; Pappalardi, M.; Biju, M.; DiFilippo, E.H.; Shaw, T.; Wiggall, K. , et al., Discovery and Preclinical Characterization of GSK1278863 (Daprodustat), a Small Molecule Hypoxia Inducible Factor–Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor for Anemia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 363, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieb, M.E.; Menzies, K.; Moschella, M.C.; Ni, R.; Taubman, M.B. , Mammalian EGLN genes have distinct patterns of mRNA expression and regulation. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002, 80, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, M.J.; Zhao, Q.; Flores, A.; Harrison, C.; Lappin, T.R.J.; Maxwell, P.H.; McMullin, M.F.; Lee, F.S. , A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelhoff, R.J.; Tian, Y.-M.; Raval, R.R.; Turley, H.; Harris, A.L.; Pugh, C.W.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Gleadle, J.M. , Differential Function of the Prolyl Hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the Regulation of Hypoxia-inducible Factor *. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 38458–38465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besarab, A.; Provenzano, R.; Hertel, J.; Zabaneh, R.; Klaus, S.J.; Lee, T.; Leong, R.; Hemmerich, S.; Yu, K.-H.P.; Neff, T.B. , Randomized placebo-controlled dose-ranging and pharmacodynamics study of roxadustat (FG-4592) to treat anemia in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD) patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Liu, B.-C.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Xing, C.; Liang, X.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, X. , et al., Roxadustat Treatment for Anemia in Patients Undergoing Long-Term Dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Peng, X.; Lin, H.; Yin, A.; Hao, L.; Tao, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Xing, C. , et al., Roxadustat for Anemia in Patients with Kidney Disease Not Receiving Dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schödel, J.; Grampp, S.; Maher, E.R.; Moch, H.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Russo, P.; Mole, D.R. , Hypoxia, Hypoxia-inducible Transcription Factors, and Renal Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslehi, J.; Minamishima, Y.A.; Shi, J.; Neuberg, D.; Charytan, D.M.; Padera, R.F.; Signoretti, S.; Liao, R.; Kaelin, W.G. , Loss of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Activity in Cardiomyocytes Phenocopies Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2010, 122, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.; Johnson, R.S.; Simon, M.C. , HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, M.; Tanaka, S.; Tanaka, T.; Saito, H.; Ishimoto, Y.; Wakashima, T.; Ueda, M.; Fukui, K.; Shimizu, A.; Inagi, R. , et al., Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain Inhibitor Protects against Metabolic Disorders and Associated Kidney Disease in Obese Type 2 Diabetic Mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, S.R.; Print, C.; Farahi, N.; Peyssonnaux, C.; Johnson, R.S.; Cramer, T.; Sobolewski, A.; Condliffe, A.M.; Cowburn, A.S.; Johnson, N. , et al., Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1α–dependent NF-κB activity. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Eric V. ; Barbi, J.; Yang, H.-Y.; Jinasena, D.; Yu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Bordman, Z.; Fu, J.; Kim, Y.; Yen, H.-R., et al., Control of TH17/Treg Balance by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Cell 2011, 146, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Kurihara, S.; Anayama, M.; Makino, Y.; Nagasawa, M. , Four Cases of Serum Copper Excess in Patients with Renal Anemia Receiving a Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor: A Possible Safety Concern. Case Rep. Nephrol. Dial. 2022, 12, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbane, S.; Pollock, C.A.; El-Shahawy, M.A.; Escudero, E.T.; Rastogi, A.; Pham van, B.; Frison, L.; Houser, M.T.; Pola, M.; Guzman, N.J. , et al., ROCKIES: An International, Phase 3, Randomized, Open-Label, Active-Controlled Study of Roxadustat for Anemia in Dialysis-Dependent CKD Patients [Abstract TH-OR022]. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Duvroq (Daprodustat): Japanese prescribing information. https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/340278_39990D4F1024_1_01 (Accessed 14 August 2020).

- Sanghani, N.S.; Haase, V.H. , Anemia in CKD. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara, M.; Tanaka, T.; Nangaku, M. , Future perspectives of anemia management in chronic kidney disease using hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 239, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Minutolo, R.; De Nicola, L.; Del Vecchio, L. , Evolving Strategies in the Treatment of Anaemia in Chronic Kidney Disease: The HIF-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors. Drugs 2022, 82, 1565–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Fang, S.; Mao, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X. , Tetrahydropyridin-4-ylpicolinoylglycines as novel and orally active prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) inhibitors for the treatment of renal anemia. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, S. , Difference in Therapeutic Effects between Roxadustat and Daprodustat, HIF-Ph Inhibitors, Depending on the Blood Type in Hemodialysis (HD) Patients. Blood 2021, 138, 4147–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimovic Jovic, J.; Antic, S.; Nikolic, T.; Andric, K.; Petrovic, D.; Bolevich, S.; Jakovljevic, V. , Erythropoietin Resistance Development in Hemodialysis Patients: The Role of Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9598211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L. , The Cross-Link between Ferroptosis and Kidney Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6654887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, X.; Huang, X.; Fu, W.; Wang, L.; Qiu, L.; Li, J.; Sun, L. , Ferroptosis, a new target for treatment of renal injury and fibrosis in a 5/6 nephrectomy-induced CKD rat model. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiuling, W.; Jianjun, L.; Ying, Y.; Rong, X.; Lu, W.; Xuedong, W.; Fubin, T. , Safety of Weekly Single versus Divided Administration of Moderate-dose Erythropoietin in the Treatment of Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients with Renal Anemia. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2023, 26, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mravic, M. ; He, L. ; Kratochvil, H. ; Hu, H. ; Nick, S.E. ; Bai, W. ; Edwards, A. ; Jo, H. ; Wu, Y. ; DiMaio, D., et al., Designed Transmembrane Proteins Inhibit the Erythropoietin Receptor in a Custom Binding Topology. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.2002.2013.526773.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).