Submitted:

23 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental animals

2.2. Experimental design and treatment

2.3. Clinical examination of dairy cows

| Score | Description | Assessment criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | The cow walks and stands with a level-backed stance. It has a normal gait. |

| 2 | Mildly lame | The cow stands with a straight back and walks with a stretched back. It has a normal gait. |

| 3 | Moderately lame | An arched back can be seen whether standing or walking. Cows walk in a short stride with one or more limbs/hoofs. |

| 4 | Lame | An arched back is constantly visible, and gait is best described as one purposeful step at a time. The cow favors one or more limbs or hooves. |

| 5 | Severely lame | The cow also exhibits an incapability or reluctance to transfer weight on one or more of its limbs or hoofs. |

2.4. Laminar tissue sampling

2.5. RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

2.6. RT-qPCR

| Genes | Ref Seq accession No. | Primer sequences (5`-3`) |

|---|---|---|

| ATG-5 | NM_001034579.2 | Forward: ACACCTTTGCAGTGGCTGAGTG Reverse: TCTGTTGGTTGCGGGATGATGC |

| ATG-12 | NM_001076982.1 | Forward: GAGCGAACCCGAACCATCCAAG Reverse: AGGGTCCCAACTTCCTGGTCTG |

| Becilin-1 | NM_001033627.2 | Forward: GCAGGTGAGCTTCGTGTGTCAG Reverse: GCTGGGCTGTGGCAAGTAATGG |

| mTOR | XM_002694043.6 | Forward: GCACGTCAGCACCATCAACCTC Reverse: CAGCCGCCGCAGCCATTC |

| P-62 | NM_176641.1 | Forward: CCAGGAGGTGCCCAGAAACATG Reverse: AGGCGGAGCATAGGTCGTAGTC |

| GAPDH | DQ402990 | Forward: GGGTCATAAGTCCCTCCACGA Reverse: GGTCATAAGTCCCTCCACGA |

2.7. Western blot

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical manifestation of dairy cow laminitis

| Time | Control cows (n=6) | OF-treated cows (n=6) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| -72h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 12h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 18h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 24h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 36h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 48h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 60h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 72h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

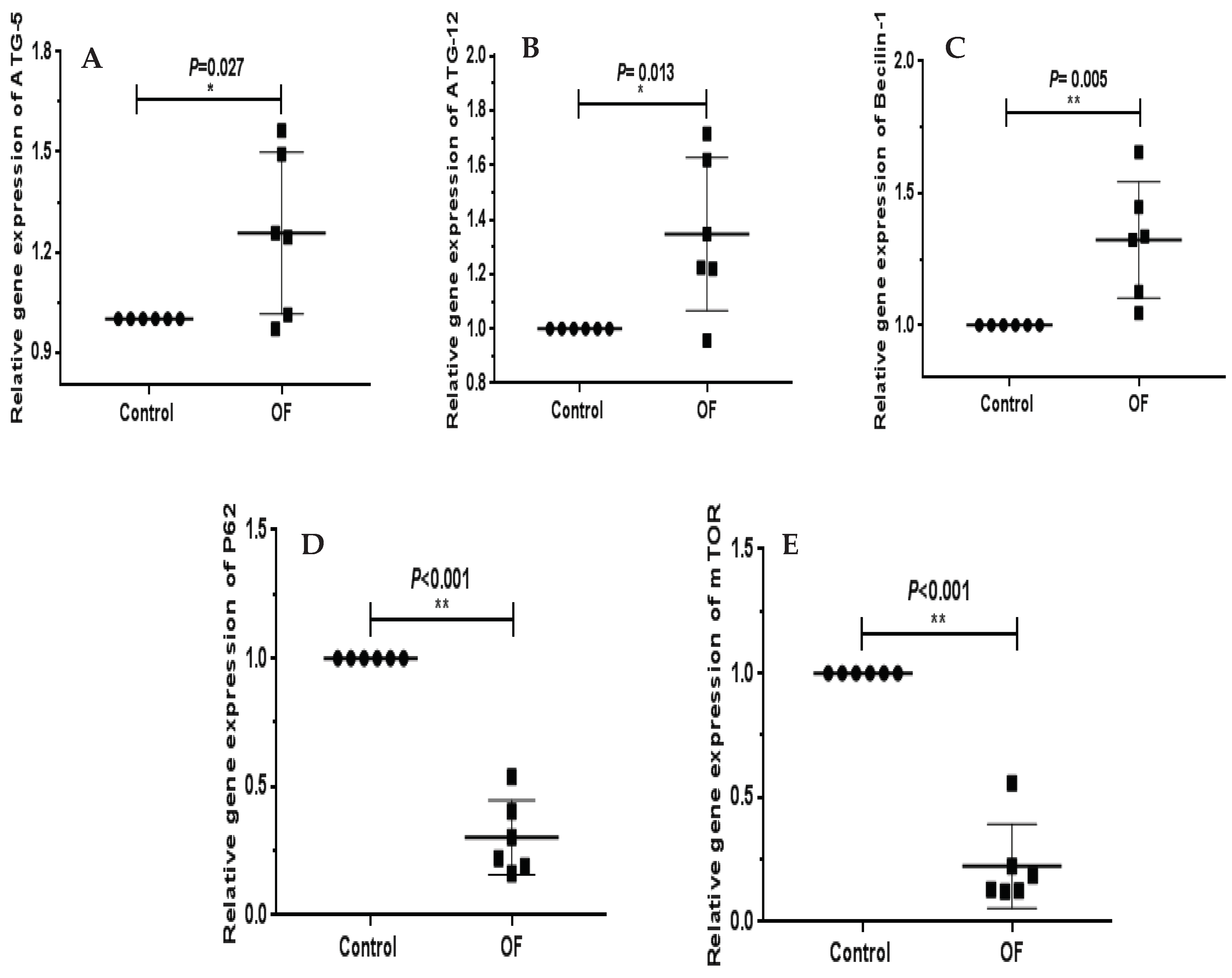

3.2. Autophagy-associated genes expression in laminar tissue of laminitis dairy cow

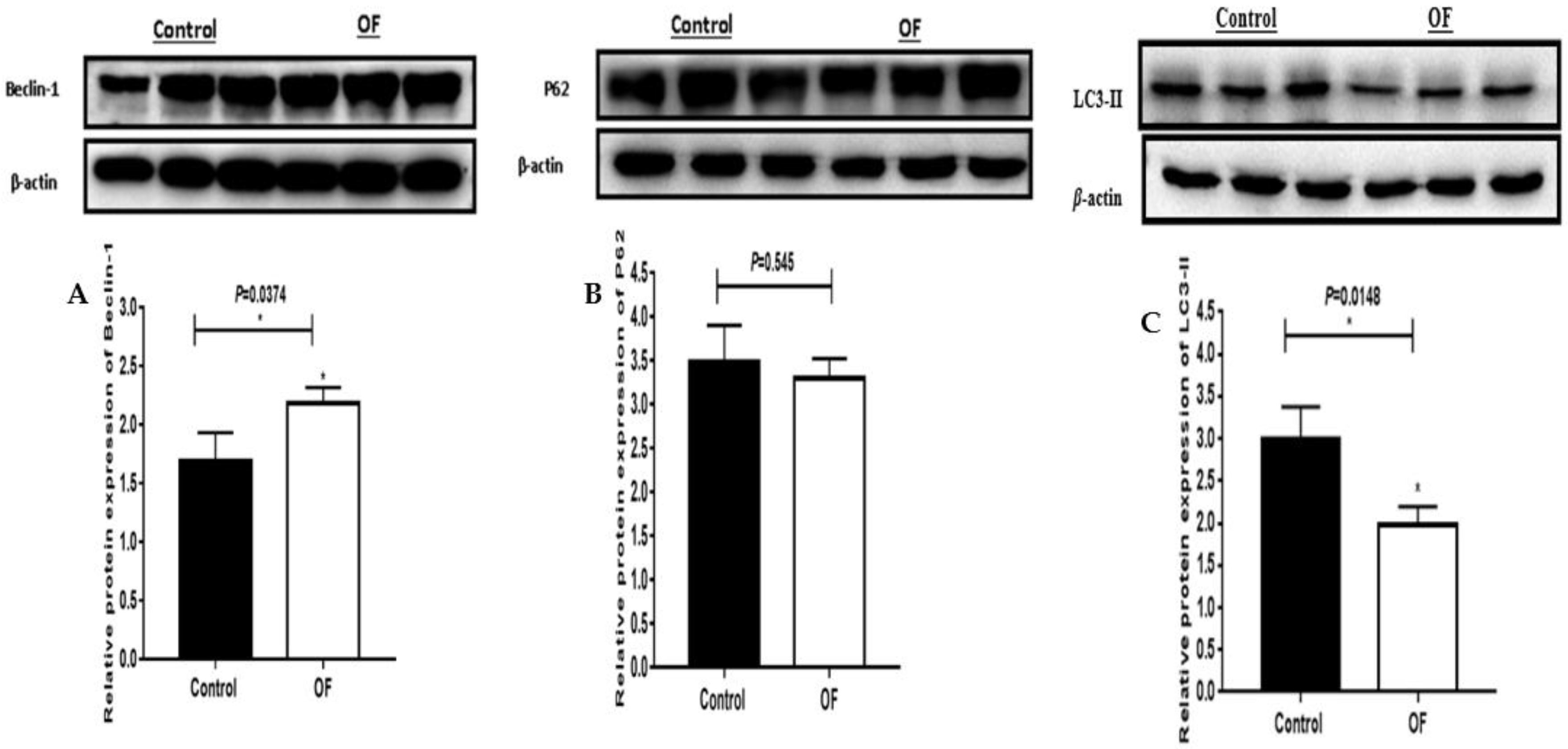

3.3. Autophagy-associated proteins expression in laminar tissue of laminitis dairy cow

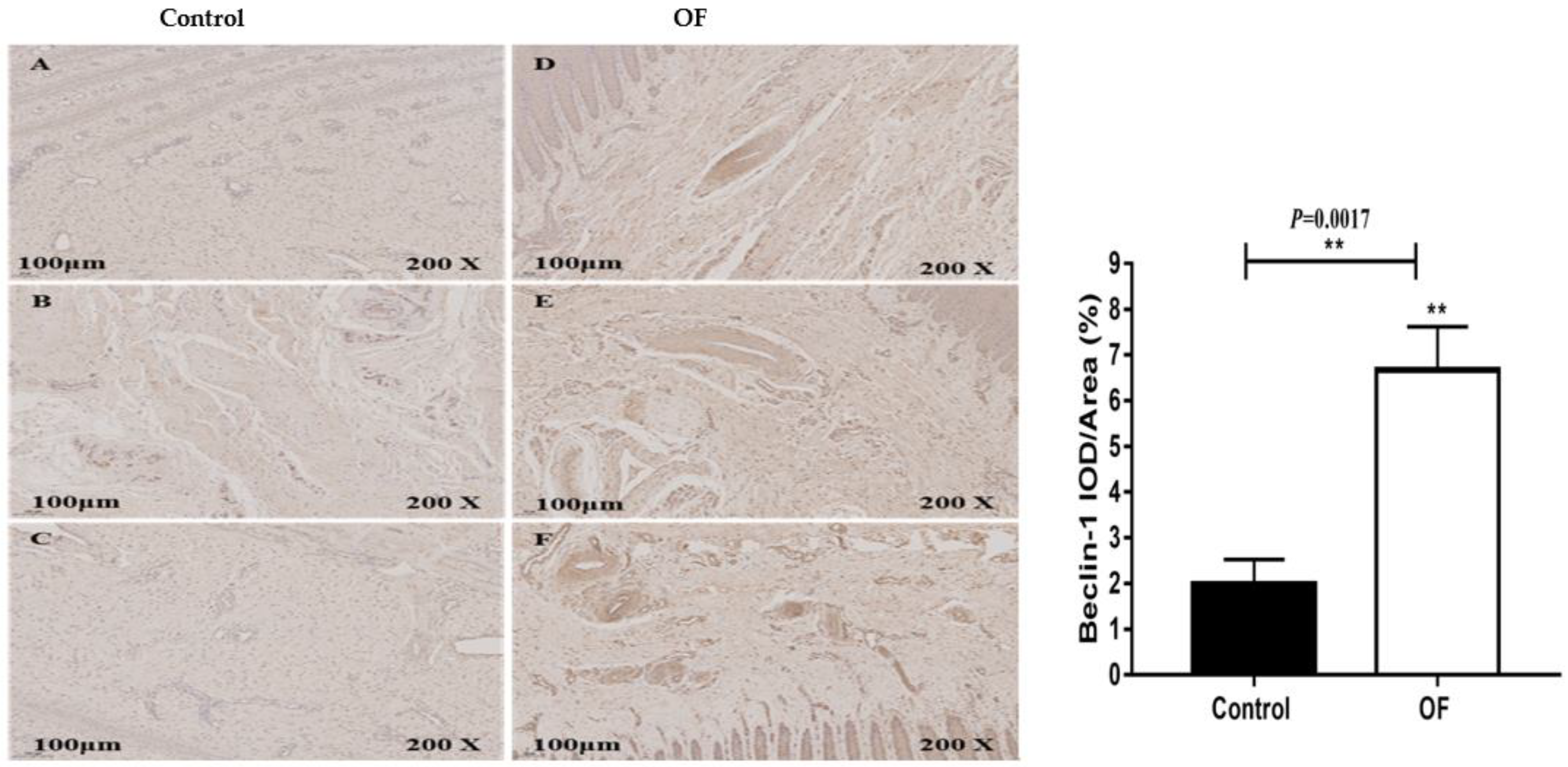

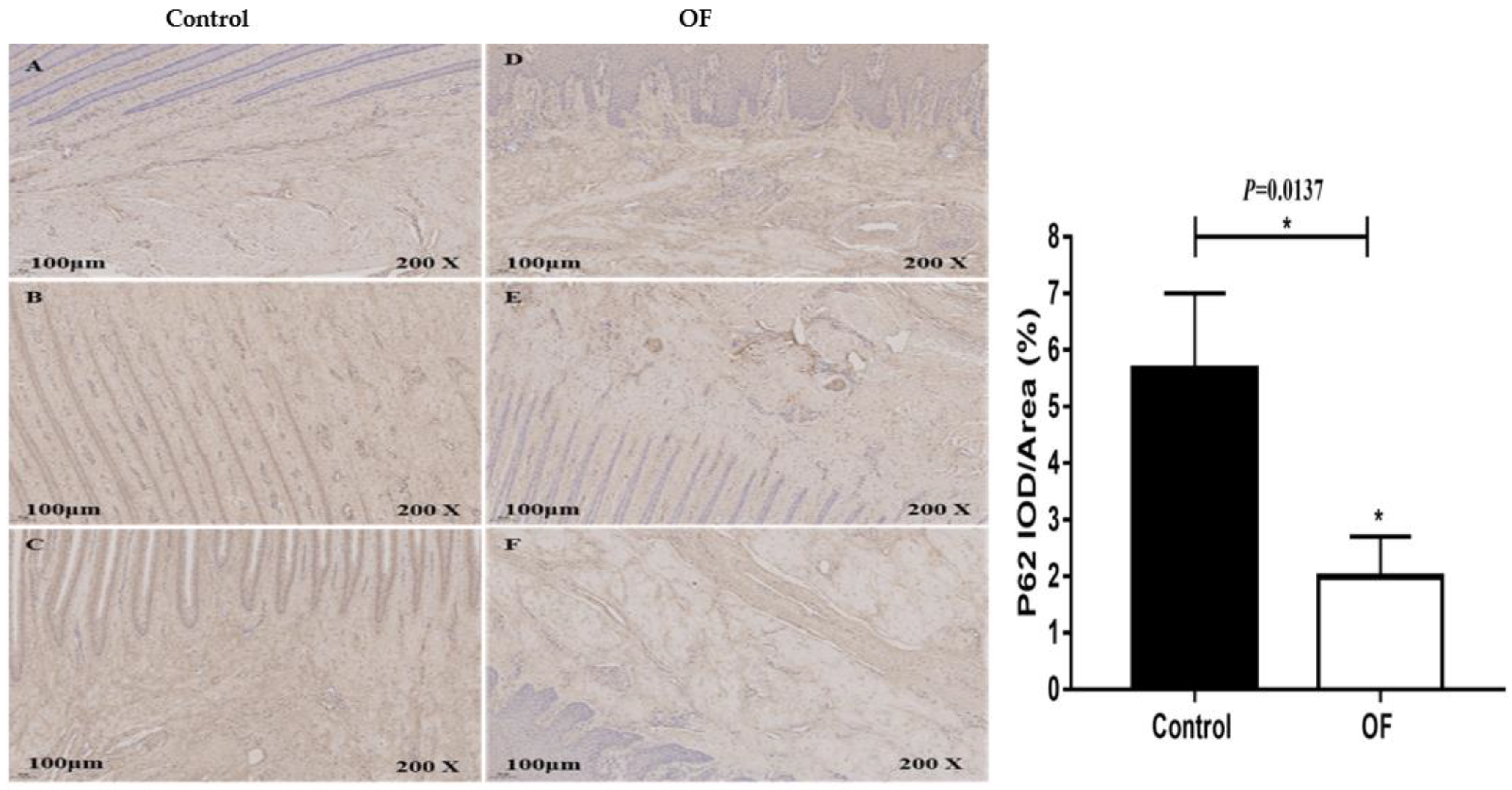

3.4. Immuno-expression of Becilin1 and P62 proteins in laminar tissue of laminitis dairy cow

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author’s Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- Boosman, R.; Nemeth, F.; Gruys, E. Bovine laminitis: Clinical aspects, pathology and pathogenesis with reference to acute equine laminitis. Vet. Q. 1991, 13, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolecheck, K.; Bewley, J. Animal board invited review: Dairy cow lameness expenditures, losses and total cost. Animal. 2018, 12, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyaw-Tanner, M.; Pollitt, C.C. Equine laminitis: increased transcription of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) occurs during the developmental phase. Equine. Vet. J. 2004, 36, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermunt, J. “Subclinical” laminitis in dairy cattle. N. Z. Vet. J. 1992, 40, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvergnas, M.; Strabel, T.; Rzewuska, K.; Sell-Kubiak, E. Claw disorders in dairy cattle: effects on production, welfare and farm economics with possible prevention methods. Livest. Sci. 2019, 222, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterton, S.L.; Bell, N.J.; Whay, H.R.; Berry, E.A.; Atkinson, O.C.; Dean, R.S.; Main, D.C.; Huxley, J.N. A descriptive review of the peer and non-peer reviewed literature on the treatment and prevention of foot lameness in cattle published between 2000 and 2011. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenough, P.R. Bovine Laminitis and Lameness: A Hands on Approach. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2007.

- Tian, M.Y.; Fan, J.H.; Zhuang, Z.W.; Dai, F.; Wang, C.Y.; Hou, H.T.; Ma, Y.Z. Effects of silymarin on p65 NF-κB, p38 MAPK and CYP450 in LPS-induced hoof dermal inflammatory cells of dairy cows. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoefner, M.B.; Pollitt, C.C.; Van-Eps, A.W.; Milinovich, G.J.; Trott, D.J.; Wattle, O.; Andersen, P.H. Acute bovine laminitis: a new induction model using alimentary oligofructose overload. J. Dairy. Sci. 2004, 87, 2932–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danscher, A.M.; Enemark, J.M.D.; Telezhenko, E.; Capion, N.; Ekstrom, C.T.; Thoefner, M.B. Oligofructose overload induces lameness in cattle. J. Dairy. Sci. 2009, 92, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoefner, M.B.; Wattle, O.; Pollitt, C.C.; French, K.R.; Nielsen, S.S. Histopathology of oligofructose-induced acute laminitis in heifers. J. Dairy. Sci 2005, 88, 2774–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, H.M.; Casagrande, F.P.; Lima, I.R.; Souza, C.H.; Gontijo, L.D.; Alves, G.E.; Vasconcelos, A.C.; Faleiros, R.R. Histopathology of dairy cows' hooves with signs of naturally acquired laminitis. Pesquisa. Vet. Brasil. 2013, 33, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.D.S.; Oliveira, F.L.C.; Dias, M.R.B.; Minami, N.S.; Amaral, L.; Santos, J.A.A.D.; Barreto, J.R.A.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Ortolani, E.L. Characterization of oligofructose-induced acute rumen lactic acidosis and the appearance of laminitis in zebu cattle. Animals. 2020, 10, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leise, B.S.; Faleiros, R.R.; Watts, M.; Johnson, P.J.; Black, S.J.; Belknap, J.K. Laminar inflammatory gene expression in the carbohydrate overload model of equine laminitis. Equine. Vet. J. 2011, 43, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dern, K.; van-Eps, A.; Wittum, T.; Watts, M.; Pollitt, C.; Belknap, J. Effect of continuous digital hypothermia on lamellar inflammatory signaling when applied at a clinically-relevant timepoint in the oligofructose laminitis model. J. Vet. Int. Med. 2018, 32, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Cuervo. A. M. Autophagy in the cellular energetic balance. Cell. Metab. 2011, 13, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikic, I.; Elazar, Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Xu, F.; Fang, Z.; Loor, J.J.; Ouyang, H.; Chen, M.; Jin, B.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, Y. Hepatic autophagy and mitophagy status in dairy cows with subclinical and clinical ketosis. J. Dairy. Sci. 2021, 104, 4847–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Loor, J.J.; Zhai, Q.; Liang, Y.; Yu, H.; Du, X.; Shen, T.; Fang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y. Enhanced autophagy activity in liver tissue of dairy cows with mild fatty liver. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 3628–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; White, E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010, 330, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008, 132, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AM, M.N.L.B.C.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008, 451, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Chang, G.; Shen, X. Subacute ruminal acidosis downregulates FOXA2, changes oxidative status, and induces autophagy in the livers of dairy cows fed a high-concentrate diet. J. Dairy. Sci. 2023, 106, 2007–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprecher, D.E.; Hostetler, D.E.; Kaneene, J.B. A lameness scoring system that uses posture and gait to predict dairy cattle reproductive performance. Theriogenology. 1997, 47, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonson, A.J.; Lean, I.J.; Weaver, L.D.; Farver, T.; Webster, G. A body condition scoring chart for Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 1989, 72, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, S.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, Q.; Hayat, M.A.; Zhang, J.T.; Wang, H. Laminar inflammation responses in the oligofructose overload induced model of bovine laminitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, L.; Qi, D.; Tao, Z.; Hayat, M.A.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.T.; Wang, H. Gene Expression of Metalloproteinases and Endogenous Inhibitors in the Lamellae of Dairy Heifers With Oligofructose-Induced Laminitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 597827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, M.A.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.U.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.I.; Li, S.; Wang, H.B. Determination of the activity of selected antioxidant enzymes during bovine laminitis, induced by oligofructose overload. Med Weter. 2020, 76, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.A. Clinical, morphological and experimental studies of laminitis in cattle. Acta. Vet. Scand. 1963, 4, 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E.; Li, S.; Gozho, G.N.; Krause, D.O. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), endotoxins and health consequences. Animal. Feed. Ence. Technol. 2012, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafipour, E.; Krause, D.O.; Plaizier, J.C. A grain-based subacute ruminal acidosis challenge causes translocation of lipopolysaccharide and triggers inflammation. J. Dairy. Ence. 2009, 92, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Sun, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Inflammatory mechanism of Rumenitis in dairy cows with subacute ruminal acidosis. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.I.; Carretta, M.D.; Alarcón, P.; Manosalva, C.; Müller, A.; Navarro, M.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Kaehne, T.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.R.; Burgos, R.A. Pro-inflammatory mediators and neutrophils are increased in synovial fluid from heifers with acute ruminal acidosis. BMC Vet Res. 2019, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Cao, D. An overview of autophagy: Mechanism, regulation and research progress. Bulletin. Du. Cancer. 2021, 108, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; Levine, B.; Cuervo, A.M.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008, 451, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Klionsky, D.J. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Develop. Cell. 2004, 6, 463-–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Codogno, P. Regulation and role of autophagy in mammalian cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 2445–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Changotra, H. The beclin 1 interactome: Modification and roles in the pathology of autophagy-related disorders. Biochimie 2020, 175, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wuniqiemu, T.; Tang, W.; Teng, F.; Bian, Q.; Yi, L.; Qin, J.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Dong, J. Luteolin inhibits autophagy in allergic asthma by activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and inhibiting Beclin-1-PI3KC3 complex. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 94, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Fang, C.; Russell, R.C.; Kim, J.H.; Fan, W.; Liu, R.; Zhong, Q.; Guan, K.L. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013, 152, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Park, H.W.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Neufeld, T.P.; Dillin, A.; Guan, K.L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nature. Cell. Bio. 2013, 15, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, T.; Noda, N.N.; Satomi, Y.; Ichimura, Y.; Fujioka, Y.; Takao, T.; Inagaki, F.; Ohsumi, Y. The Atg12-Atg5 conjugate has a novel E3-like activity for protein lipidation in autophagy. J. Bio. Chemi. 2007, 282, 37298–37302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Klionsky, D.J. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Ann. Rev. Gen. 2009, 43, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, J.H.; Young, L.N. Mechanisms of autophagy initiation. Ann. Rev. Bio. 2017, 86, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, A.; Mayoral, R.; Agra, N.; Valdecantos, M.P.; Pardo, V.; Miquilena-Colina, M.E.; Vargas-Castrillón, J.; Lo-Iacono, O.; Corazzari, M.; Fimia, G.M.; Piacentini, M. Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell. Death. Disease. 2014, 5, e1179–e1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, J.; Walker, S.J.; Brugge, J.S. Akt activation disrupts mammary acinar architecture and enhances proliferation in an mTOR-dependent manner. J. Cell. Bio. 2003, 163, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Loor, J.J.; Zhai, Q.; Liang, Y.; Yu, H.; Du, X.; Shen, T.; Fang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y. Enhanced autophagy activity in liver tissue of dairy cows with mild fatty liver. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 3628–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Du, X.; Sun, X.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, C.; Xu, Q.; Abdelatty, A.M.; Mohamed, F.F.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G. Increased autophagy mediates the adaptive mechanism of the mammary gland in dairy cows with hyperketonemia. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 2545–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).