1. Introduction

Meningiomas are intracranial growths that emerge from the meninges, which are defensive layers that encompass the mind and spinal string. They represent roughly 30% of all essential mind cancers, making them one of the most widely recognized types of cerebrum growth in adults. Meningiomas are overwhelmingly harmless; however, a few cases show a forceful way of behaving or repeating after the introductory treatment [

1]. Although medical procedures and radiation treatment are the backbone of therapy, there is a developing requirement for powerful fundamental treatments, particularly for patients with repetitive or forceful meningiomas [

2,

3].

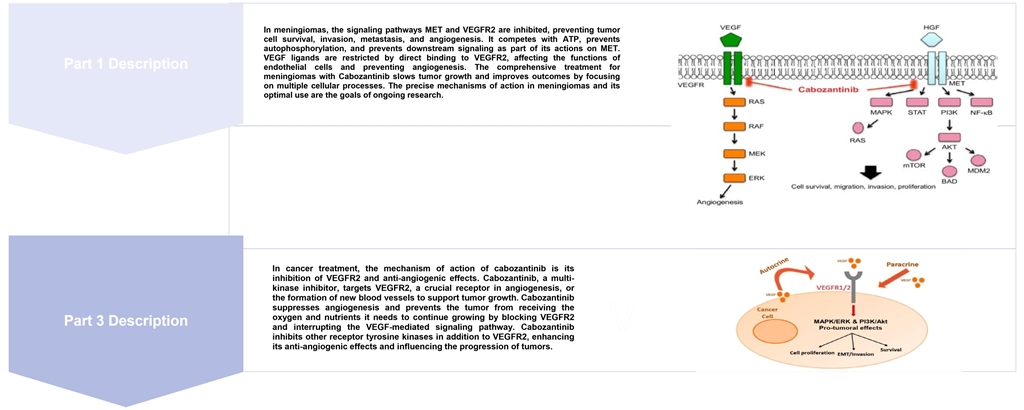

Recent advances in atomic science and genomics have revealed insights into the fundamental sub- atomic adjustments and flagging pathways involved in meningioma improvement. These revelations have opened new roads for designated treatments that plan to disturb explicit sub-atomic targets answerable for cancer development and movement [

4]. One such treatment that guarantees the treatment of meningiomas is cabozantinib, a multikinase inhibitor.

Cabozantinib applies its pharmacological impacts by restraining numerous receptor tyrosine kinases, including vascular endothelial development factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), MET, and AXL. The restraint of these flagging pathways has been related to cancer impacts in different malignancies, making cabozantinib an alluring contender for meningioma therapy [

5,

7]. Preclinical examinations exploring the utilization of cabozantinib in meningioma models have shown its capacity to hinder angiogenesis, reduce cancer development, and prompt cell passage, providing areas of strength for clinical examination.

2. Pathophysiology of Intracranial Meningiomas

Intracranial meningiomas are cerebral cancers that arise from unusual cell development in the meninges and defensive layers covering the mind and spinal line. While the exact reason for meningiomas remains unclear, analysts have distinguished a few hereditary and sub-atomic elements involved in their pathophysiology. Hereditary modifications assume a critical part, with changes in qualities, for example, NF2 being habitually noticed [

1]. NF2 quality regularly functions as a growth silencer, and its inactivation is tracked down in approximately 50% of all meningiomas. Moreover, different qualities of AKT1, SMO, TRAF7, and KLF4 have been shown to improve meningioma. Chemicals, especially estrogen and progesterone, are related to meningioma development, with a higher pervasiveness of growth in women. Hormonal elements, such as pregnancy, chemical substitution treatment, and certain hormonal problems, can expand the gambling of meningioma arrangement and movement [

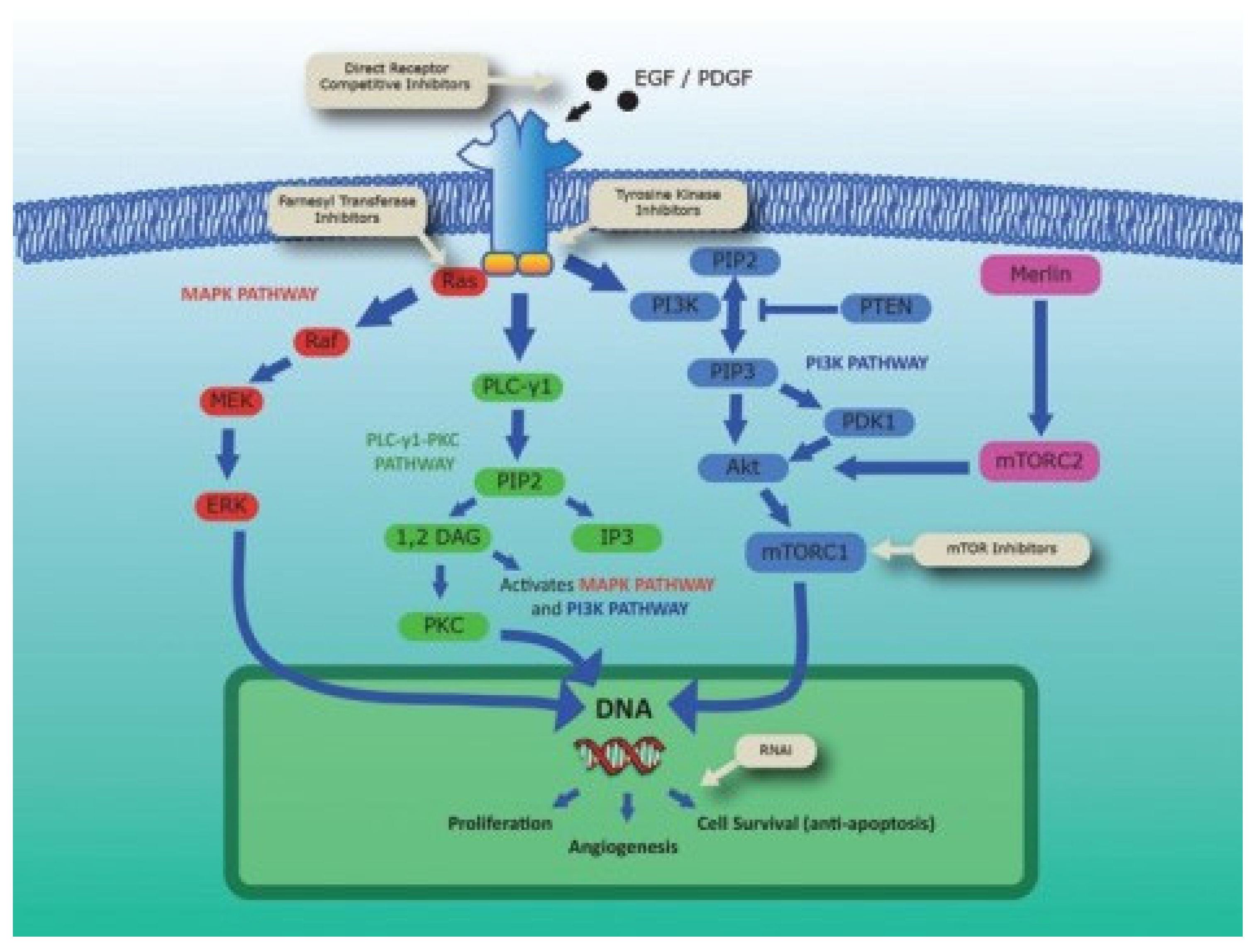

2]. Unusual flagging pathways contribute to the pathophysiology of intracranial meningioma. Dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt/β- catenin, and Sonic Hedgehog pathways can result in uncontrolled cell multiplication and growth development. Angiogenesis, which is the development of fresh blood vessels, is imperative for the supported development of meningiomas [

3]. Growth cells discharge angiogenic factors such as VEGF, which animate the improvement of veins in the cancer microenvironment, providing essential oxygen and supplements for cancer extension.

As intracranial meningiomas develop, they can attack areas close to the cerebrum tissue and apply tension to neighboring designs, prompting different neurological side effects. Meningiomas can penetrate the cerebrum parenchyma, veins, and dural sinuses [

4]. In addition, they can pack close to nerves, bringing about utilitarian debilitation. Meningiomas are characterized into various grades based on the World Wellbeing Association (WHO) evaluation framework. Grade I meningiomas are ordinarily harmless and slow-developing, whereas grades II and III show a higher threat and more forceful behaving [

5]. Understanding the pathophysiology of intracranial meningiomas is essential for the advancement of designated treatments and development of treatment results [

6]. Progress in atomic science and hereditary qualities has provided significant knowledge of the fundamental components of meningioma improvement, prompting possible restorative targets and customized treatment [

7]. By unwinding the intricacies of meningioma pathophysiology, scientists intend to work on quiet considerations and to improve visualization [

8].

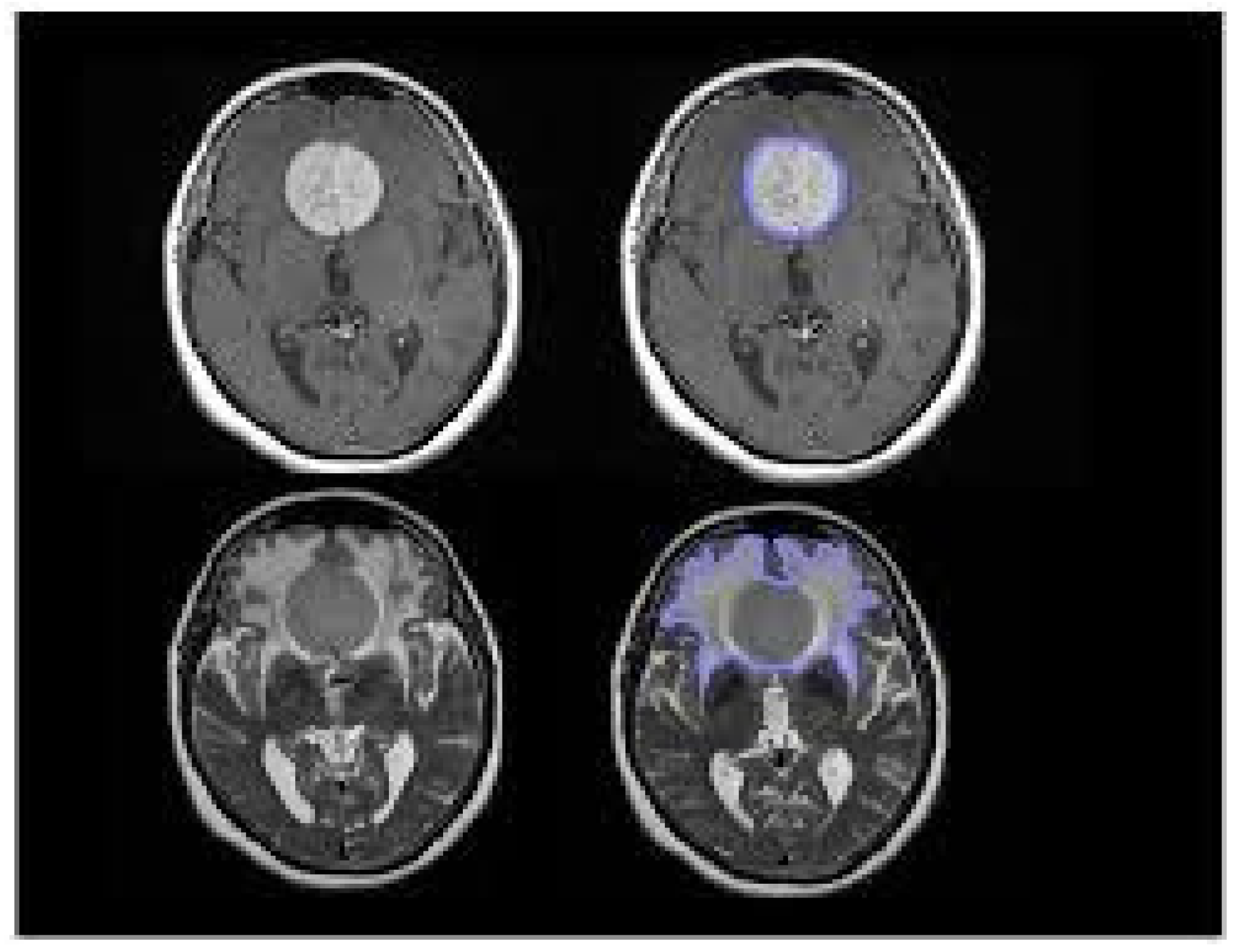

Enhanced lesion on 3D T1-weighted sequences and to identify its relative hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences using Horos software [30].

Enhanced lesion on 3D T1-weighted sequences and to identify its relative hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences using Horos software [30].

3. Potential Therapeutic Targets

As of late, broad exploration has zeroed in distinguishing possible restorative focuses for meningioma, fully intent on growing more viable medicines for this difficult mind cancer. A few promising targets have arisen, offering new routes for remedial mediation, such as the Epidermal Development Component Receptor (EGFR) [

9]. EGFR overexpression has been observed in a subset of meningiomas, suggesting its true capacity as a remedial objective [

10]. Hindrance of EGFR utilizing designated inhibitors, such as gefitinib or erlotinib, has shown promising outcomes in preclinical examinations and early stage clinical preliminaries [

11]. Be that as it may, further examinations are expected to decide the viability and wellbeing of EGFR inhibitors as a treatment choice for meningioma [

12].

Another appealing objective is the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway, which plays a significant role in angiogenesis. Meningiomas are known to depend on angiogenesis for their development and movement [

13]. Focusing on VEGF-utilizing monoclonal antibodies such as bevacizumab has shown that empowering brings about clinical preliminaries, exhibiting its true capacity as a remedial choice for meningioma [

14]. Notwithstanding, extra examinations are expected to completely grasp the ideal dosing, treatment term, and potential unfavorable impacts related with VEGF-designated treatment in meningiomas [

15].The dysregulation of the mammalian Objective of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is habitually seen in meningiomas and offers a promising remedial objective [

16]. Inhibitors of mTOR, such as everolimus, have shown viability in preclinical examinations and early stage clinical preliminaries. Notwithstanding, further examination is required to determine the advantages and potential opposition components related to mTOR hindrance in meningioma treatment [

17].

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have likewise arisen as expected helpful specialists for meningiomas. These inhibitors can adjust the quality of articulation designs, prompt cell cycle capture, and advance apoptosis in meningioma cells [

18]. Vorinostat, an HDAC inhibitor, has shown promising outcomes in early stage clinical preliminaries. In any case, greater clinical examination is important to determine its potential and assess its blend with other treatment modalities. In addition, somatostatin receptors have been identified as the focus of meningioma treatment [

19]. Meningioma cells frequently express somatostatin receptors, making them vulnerable to treatment with somatostatin analogs such as octreotide or pasireotide [

20]. These analogs have exhibited viability in controlling cancer development and overseeing the side effects in specific cases [

21]. Nonetheless, further studies are required to determine the ideal use and possible symptoms of somatostatin analogs in meningioma treatment.

Finally, evidence suggests that immunotherapy might hold a guarantee for the treatment of meningiomas. Resistant designated spot inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have shown action in meningiomas with high mutational weights or safe penetrates [

22]. Additionally, peptide-based immunization and supportive cell treatments are being investigated in preclinical and early stage clinical examinations [

23]. In any case, additional exploration is justified to explain the ideal patient determination rules, treatment regimens, and potential mixed ways to augment the viability of immunotherapeutic methodologies in meningioma [

24].

Illustration illustrating the many interactions between VEGF/VEGFR and the compounds that block their signaling pathways. PIGF, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D are the five members of the mammalian VEGF family. VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3 are the three members that bind VEGFR. The surface of the numerous cells listed under the receptor has these receptors. The VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathways can be targeted by a variety of agents [62].

Illustration illustrating the many interactions between VEGF/VEGFR and the compounds that block their signaling pathways. PIGF, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D are the five members of the mammalian VEGF family. VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3 are the three members that bind VEGFR. The surface of the numerous cells listed under the receptor has these receptors. The VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathways can be targeted by a variety of agents [62].

4. Current Treatment Approaches and Limitations

4.1. Surgical Resection

Careful resection is an essential treatment methodology for meningiomas and assumes an urgent role in the treatment of these cancers. It includes the careful expulsion of the meningioma mass from the mind or spinal string, intending to accomplish total cancer resection while saving neurological capability [

25].The objective of careful resection is to accomplish maximal safe evacuation of the cancer while limiting harm to encompassing sound mind tissue [

26]. The degree of resection relies on different elements, including the area, size, and grade of the meningioma, as well as the patient's general well-being and neurological status [

27]. For meningiomas situated in available and non-basic areas, complete resection is frequently possible and is associated with ideal results. Complete growth expulsion can prevent long-haul infections and may offer the potential for a fix. In such cases, medical procedures alone may be adequate, particularly for second-rate meningiomas [

28]. Notwithstanding, accomplishing total resection can be used to treat meningiomas situated in basic or articulate mind districts, for example, those close to significant neurovascular designs or firmly established growths [

28]. In these cases, the objective might be to accomplish maximal safe resection, which implies eliminating much of the growth as could be expected without causing significant neurological deficiencies. In certain cases, fractional resection or debulking of the cancer might be performed to ease side effects and diminish growth trouble, followed by adjuvant therapies such as radiation treatment or clinical treatments [

30,

31].

The careful methodology for meningioma resection differs depending on the cancer area and specialist's mastery [

32]. Strategies such as craniotomy, skull-base medical procedures, endoscopic- assisted medical procedures, and stereotactic techniques might be utilized [

33]. Propels in imaging innovation, intraoperative neuronavigation, and neurophysiological observation have worked on careful exactness and well-being, considering more exact growth evacuation [

34]. Careful resection is frequently associated with likely dangers and confusions, including disease, death, neurological deficiencies, and the chance of growth repeat or regrowth. Cautious preoperative assessment and arrangement, as well as close joint efforts among neurosurgeons and multidisciplinary groups, are fundamental to streamline careful results and limit postoperative confusion [

35].

4.2. Radiation Therapy

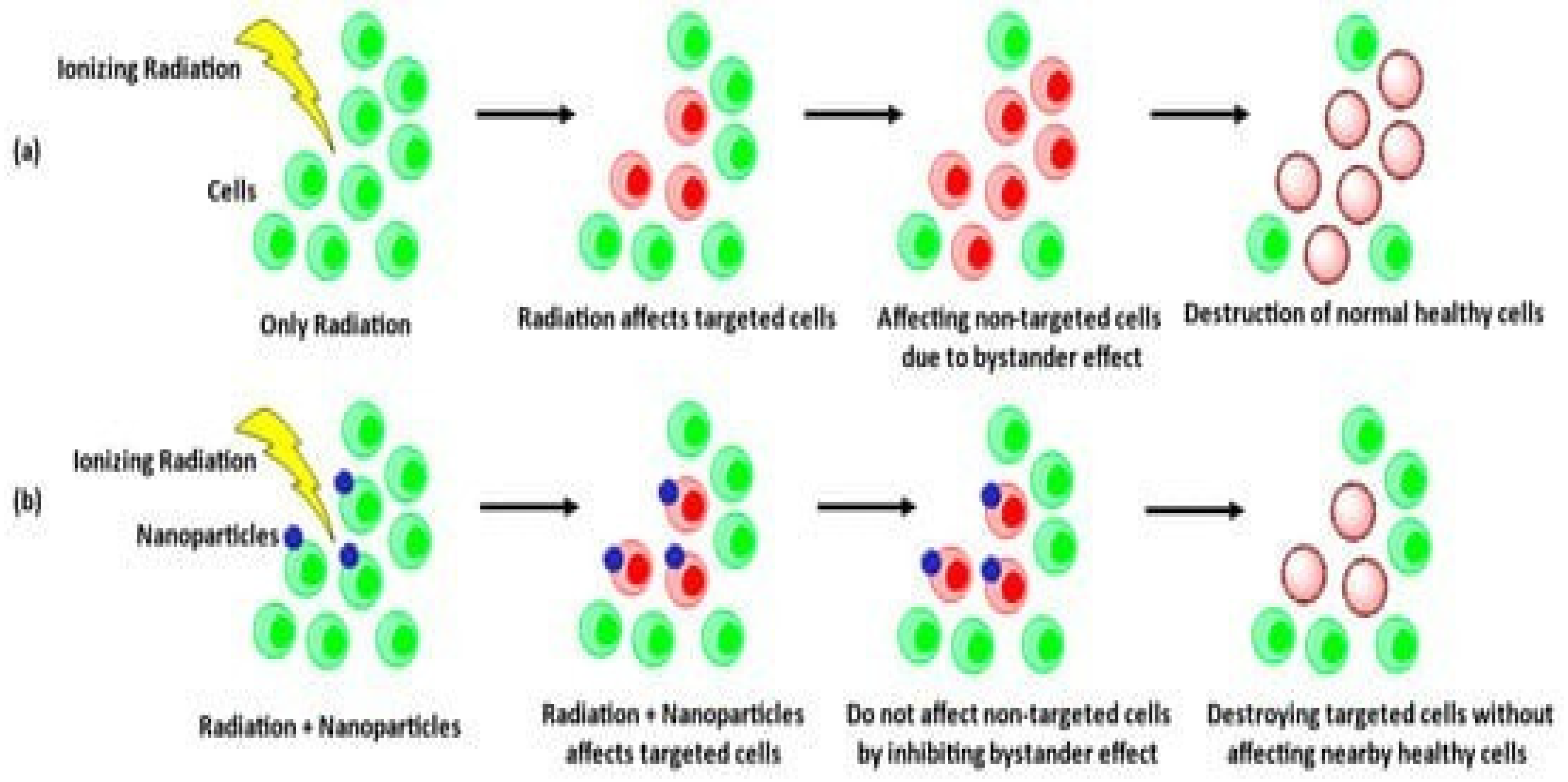

Radiation treatment, otherwise called radiotherapy, is a significant therapeutic methodology for meningiomas, both as an adjuvant treatment following careful resection and as an essential therapy choice for unresectable or repetitive cancers [

36]. This includes the utilization of high-energy radiation to target and obliterate cancer cells, hindering their development and advancing growth control. Radiation treatment is normally conveyed utilizing outer-pillar radiation, where an engaged light emission is aimed at the cancer site from outside the body [

37]. The treatment is painstakingly arranged and conveyed over different meetings, for the most part traversing half a month, to limit harm to encompassing the sound tissues [

38].

Effects on bystanders brought on by radiation. (a) Radiation exposure to cancer cells kills both targeted and non-targeted cells. (b) Radiation combined with NPs only destroys the tumor tissues, leaving the surrounding healthy cells unharmed.

Effects on bystanders brought on by radiation. (a) Radiation exposure to cancer cells kills both targeted and non-targeted cells. (b) Radiation combined with NPs only destroys the tumor tissues, leaving the surrounding healthy cells unharmed.

The utilization of radiation treatment for meningiomas relies on different variables, including cancer grade, area, size, and patient-explicit contemplations [

39]. The choice to utilize radiation treatment might be impacted by the presence of lingering cancer after medical procedures, growth repeats, or as an essential therapy choice for inoperable growth [

40]. For higher-grade or forceful meningiomas, radiation treatment is often prescribed after careful resection to further develop growth control and lessen the gamble of repeat [

41]. Adjuvant radiation treatment has been demonstrated to be especially useful for growths with horrible histological highlights or those situated in testing physical districts where complete resection cannot be achieved [

42].

In situations where complete resection is not possible, or in repetitive meningiomas, radiation treatment can be utilized as an essential therapy methodology [

43]. It plans to control cancer development, mitigate side effects, and achieve generally quiet results. Stereotactic radiosurgery, a procedure that conveys profoundly engaged radiation in a solitary meeting, might be utilized for small meningiomas or as rescue therapy for repetitive cancers [

44]. The adequacy of radiation treatment for meningiomas has been deeply grounded, with high paces announced by neighborhood growth control. Nonetheless, it is critical to consider the possible secondary effects and long-haul gambles related to radiation treatment. Normal intense aftereffects might include weakness, skin bothering, and going bald in the treated region [

45]. Long-haul dangers might imply radiation- actuated changes in the mind tissue, such as radiation rot or radiation-prompted auxiliary malignancies, although these entanglements are somewhat uncommon.

The choice to involve radiation treatment in meningiomas requires complete assessment by a multidisciplinary group, including neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, and neuro-oncologists. Factors such as cancer quality, patient age, general well-being status, and individual inclinations should be considered when deciding the ideal therapeutic approach [

46].

4.3. Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapies

Chemotherapy and designated treatments are emerging therapeutic choices for meningiomas, particularly in situations where careful resection and radiation treatment are not achievable or have restricted viability [

47]. While meningiomas have customarily been thought of as less receptive to regular chemotherapy, late progressions in the interpretation of the atomic attributes of these growths have opened up new roads for focused and customized treatment [

48]. Chemotherapy, which includes the use of medications to kill or hinder the development of malignant cells, has shown restricted viability as an independent treatment for meningiomas. However, certain chemotherapy specialists, such as hydroxyurea, temozolomide, and mifepristone, exhibit humble movements in unambiguous subsets of meningioma patients, especially those with forceful or repetitive cancers [

49]. These specialists might be utilized as a feature of blend treatment regimens or related to other treatment modalities to upgrade cancer reactions.

Designated treatments then explicitly target and restrain atomic pathways or proteins that are basic for cancer development and endurance. The recognizable proof of explicit subatomic changes in meningiomas has been prepared for the advancement of designated treatments customized to individual growth qualities [

50]. For example, somatostatin analogs such as octreotide or pasireotide have shown viability in subsets of meningioma patients with somatostatin receptor articulation. These specialists can bind to somatostatin receptors on cancer cells, repressing their development and reducing chemical discharge [

51]. They are especially useful in controlling cancer development and overseeing the side effects in patients with hormonally dynamic meningiomas.

Simplified diagram of the cell signaling pathways involved in the pathophysiology of meningiomas. PTEN stands for phosphatase and tensin homolog, IP3 stands for inositol 1,4,5- triphosphate, RNAi stands for RNA interference, and 1,2-DAG is for 1,2- diacylglycerophosphate [26].

Simplified diagram of the cell signaling pathways involved in the pathophysiology of meningiomas. PTEN stands for phosphatase and tensin homolog, IP3 stands for inositol 1,4,5- triphosphate, RNAi stands for RNA interference, and 1,2-DAG is for 1,2- diacylglycerophosphate [26].

Notwithstanding somatostatin analogs, other designated treatments are being investigated in preclinical and early stage clinical preliminaries [

52]. For instance, inhibitors focusing on unambiguous flagging pathways embroiled in meningioma pathogenesis, such as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway or the Sonic Hedgehog pathway, are being examined. These designated specialists intended to disturb the unusual flagging fountain and repress cancer development. In addition, immunotherapy, which outperforms the body's resistant framework to perceive and obliterate diseased cells, is also being investigated as a potential treatment choice for meningiomas [

53]. Resistant designated spot inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have shown movement in a subset of meningioma patients with high mutational weights or safe penetrates [

54]. Other immunotherapeutic methodologies, such as peptide-based antibodies and supportive cell treatments, are concentrated on preclinical and early stage clinical preliminaries [

55].

It is essential to note that while designated treatments and immunotherapy show guarantee, their adequacy in meningiomas is yet to be assessed, and further exploration is expected to determine ideal patient determination standards, treatment regimens, and potential mix draws [

56]. Moreover, the recognizable proof of extra subatomic adjustments and the advancement of novel designated specialists might provide further opportunities for customized treatment methodologies for meningiomas [

57].

5. Cabozantinib: Mechanism of Action and Pharmacokinetics

Cabozantinib is a medication for targeted therapy that is used to treat some types of cancer. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are the drugs in this class. Cabozantinib specifically inhibits several receptor tyrosine kinases, including AXL, MET, and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). By obstructing these kinases, cabozantinib disturbs the flagging pathways that advance cancer development, angiogenesis (arrangement of fresh blood vessels), and metastasis (spread of disease to different pieces of the body) [

58,

59].

Cabozantinib has been shown to be effective in the treatment of a number of different kinds of cancer, including renal cell carcinoma in the kidney, hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver, and some types of thyroid cancer. When other treatment options have failed or are inappropriate for the patient, it is frequently used [

60]. Cabozantinib may also affect bone metabolism in addition to its anticancer effects. It has been approved for use in patients with bone metastases to treat a rare bone disorder known as metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). In these patients, cabozantinib aids in the reduction of bone pain and the prevention of further bone damage. Depending on the type of cancer being treated and the patient's condition, cabozantinib's precise dosage and administration can vary [

61,

62]. It is typically taken orally as a tablet and should be used under the supervision of a healthcare provider who is knowledgeable about the use of anticancer drugs. Cabozantinib, like any other medication, can cause side effects like fatigue, diarrhea, high blood pressure, hand-foot syndrome, which is redness, swelling, and pain in the palms and soles of the feet, among other things [

63].

5.1. Inhibition of VEGFR2 Signaling

Cabozantinib suppresses tumor angiogenesis through its inhibitory effects on VEGFR signaling through multiple pathways. First, cabozantinib prevents VEGF ligands from binding by directly binding to the extracellular domain of VEGFR [

64]. This binding interaction prevents the initiation of subsequent signaling events by interfering with VEGFR activation. Cabozantinib further disrupts VEGFR signaling by inhibiting the tyrosine kinase activity of the VEGFR protein [

65]. It prevents VEGFR's autophosphorylation and subsequent phosphorylation of signaling molecules downstream.

Cabozantinib disrupts various angiogenesis-related downstream signaling pathways as a result of its inhibition of VEGFR. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which is essential for the survival and proliferation of endothelial cells, is one important pathway that is affected [

66]. Cabozantinib blocks this pathway, making it harder for endothelial cells, which are what make new blood vessels, to live and grow. Additionally, the MAPK/ERK pathway, which controls cell growth and migration, is disrupted by cabozantinib [

67]. The proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, which are necessary for angiogenesis, are further hampered if this pathway is disrupted [

68].

Additionally, pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF are reduced as a result of cabozantinib's inhibition of VEGFR. Angiogenesis and the formation of blood vessels are both helped along by VEGF [

69]. Cabozantinib suppresses tumor angiogenesis further by reducing the production and release of VEGF. Cabozantinib hinders the development of new blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment and restricts the stimulation of VEGFR by reducing the availability of pro-angiogenic factors [

70]. Cabozantinib effectively disrupts VEGFR signaling through these multiple inhibition pathways, reducing tumor angiogenesis [

71]. Cabozantinib's anti-angiogenic effects and overall anti-tumor activity in particular cancer types are largely due to its inhibition of VEGFR [

72]. Cabozantinib is a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis that targets VEGFR and its associated signaling pathways. This makes it a useful treatment option for cancer patients [

73].

5.2. Inhibition of MET Signaling

Cabozantinib inhibits MET signaling, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in the survival, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells. Cabozantinib's overall anti-tumor activity relies heavily on its ability to inhibit MET [

74]. Cabozantinib inhibits MET signaling through a number of different mechanisms: First, cabozantinib competes with MET to bind, preventing MET's natural ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), from binding [

75]. The activation of MET and subsequent downstream signaling events are disrupted by this competitive binding.

Additionally, treatment with cabozantinib has been shown to lower MET expression in tumor cells. The reduced availability of MET receptors on the cell surface as a result of this downregulation further restricts receptor activation and signaling [

76]. Additionally, cabozantinib is a potent MET kinase activity inhibitor. Cabozantinib binds to the MET kinase domain's ATP-binding site, preventing the phosphorylation of signaling molecules downstream [

77,

78]. The activation of signaling pathways involved in cell survival, proliferation, and migration is impeded by this inhibition [

79].

Cabozantinib's anti-tumor effects are also aided by the suppression of MET activation-related downstream signaling pathways [

80]. This incorporates the restraint of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which is basic for cell endurance and multiplication, as well as the MAPK/ERK pathway, which directs cell development and movement [

81].Cabozantinib effectively blocks MET signaling through these mechanisms, reducing tumor cell survival, invasion, and metastasis. Cabozantinib's inhibition of MET, in addition to its inhibition of VEGFR, provides a comprehensive strategy for preventing tumor progression and metastasis [

82,

83]. Cabozantinib is a promising treatment option for certain types of cancers in which MET signaling plays a significant role because it targets MET [

84].

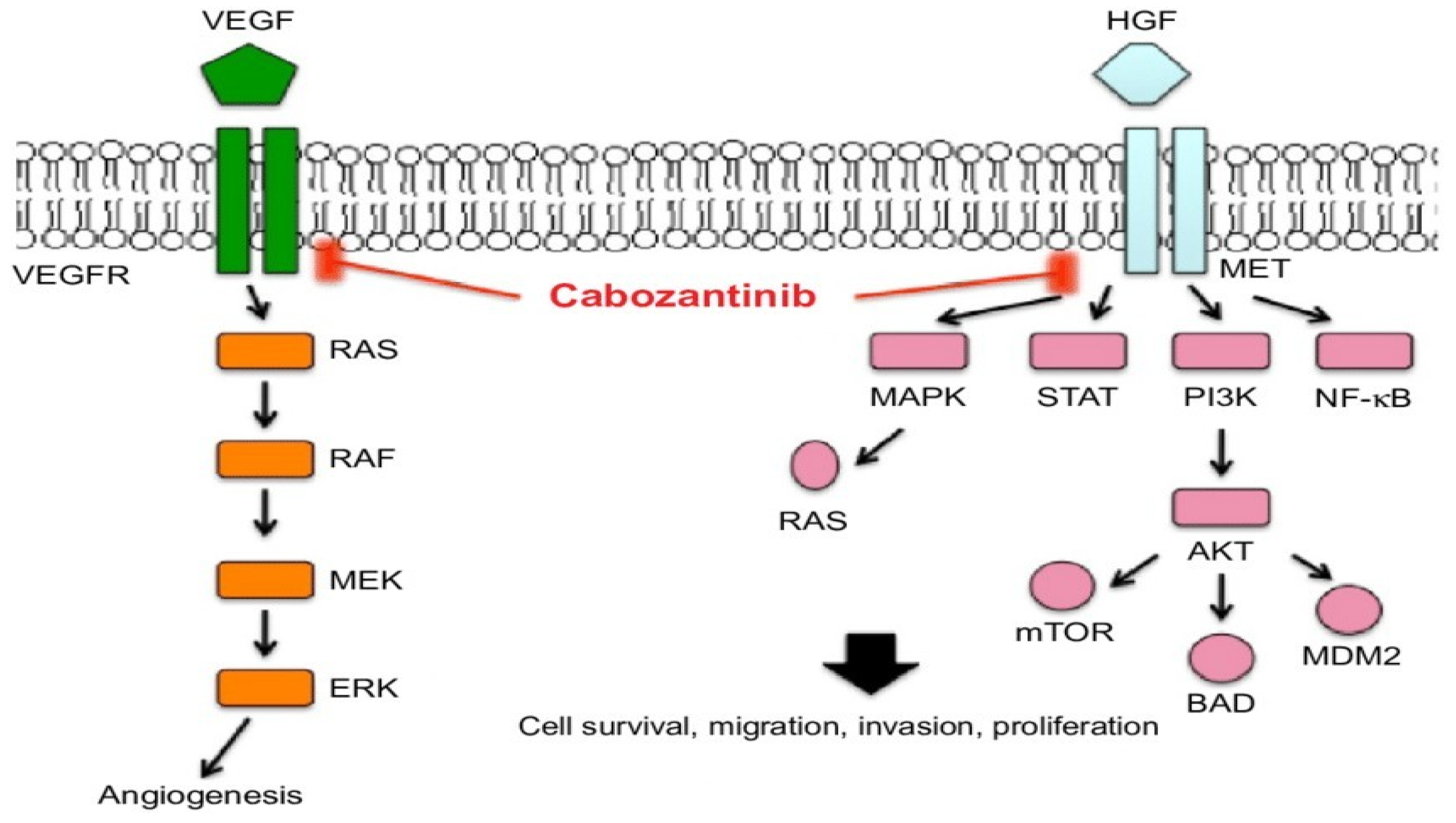

5.3. Inhibition of MET and VEGFR2 Signaling by Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib inhibits specific cellular pathways in meningiomas by inhibiting the MET and VEGFR2 signaling pathways. There are a number of ways that cabozantinib interferes with the MET pathway [

85]. First, it competes with ATP to bind to the MET kinase domain's ATP-binding site, preventing MET autophosphorylation and subsequent signaling pathway activation. The activation of pathways like PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/ERK, which are necessary for the survival, proliferation, and invasion of tumor cells, is impeded by this inhibition [

86]. Also, cabozantinib-actuated MET restraint slows down flagging fountains associated with angiogenesis, relocation, and metastasis, eventually blocking the growth's capacity to spread and attack encompassing tissues.

Cabozantinib directly targets and binds to the VEGFR2 receptor in the case of VEGFR2 signaling. By restricting to VEGFR2, cabozantinib forestalls the limiting of VEGF ligands, especially VEGF- A, which are essential for the inception of angiogenesis [

87]. Endothelial cell survival, proliferation, migration, and tube formation are all impacted by this interference with VEGFR2 activation [

88]. As a result, tumor angiogenesis is hindered by the suppression of new blood vessel formation. Meningiomas can't grow or spread as far as they could without oxygen and essential nutrients [

89].

Figure: Cabozantinib prevents the MeT pathway from acting as a secondary mechanism in the emergence of veGF TKi resistance by simultaneously inhibiting MeT and veGFR2 [82].

Figure: Cabozantinib prevents the MeT pathway from acting as a secondary mechanism in the emergence of veGF TKi resistance by simultaneously inhibiting MeT and veGFR2 [82].

A comprehensive strategy for treating meningiomas is provided by cabozantinib's inhibition of both MET and VEGFR2 signaling [

100]. Tumor cell survival, invasion, and metastasis are impaired when the MET pathway is disrupted, and tumor angiogenesis is stifled when VEGFR2 signaling is inhibited [

101]. Cabozantinib blocks important cellular processes that drive meningioma progression by targeting these pathways. This ultimately slows the growth of the tumor and improves patient outcomes. It is important to note that the precise mechanisms and subsequent effects of MET and VEGFR2 pathway inhibition mediated by cabozantinib in meningiomas are still the subject of ongoing research [

102]. Optimizing the use of cabozantinib as a targeted therapy for meningiomas and further elucidating these pathways are the goals of ongoing research and clinical trials [

103].

6. Preclinical Studies Highlighting Cabozantinib's Effects on Meningiomas

Cabozantinib's effects on meningiomas have been the subject of several preclinical studies, which have shed light on its potential as a treatment option for this kind of tumor. The efficacy of cabozantinib in meningioma tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis has been highlighted by these promising results.

In one preclinical study, in vitro and in vivo meningioma models were used to test cabozantinib. Meningioma cell proliferation and viability were significantly reduced after treatment with cabozantinib, according to the researchers [

104]. Additionally, decreased microvessel density found in tumor tissues indicates that cabozantinib prevented the development of blood vessels associated with the tumor. These results demonstrated that cabozantinib has potent anti-angiogenic properties in meningiomas [

105].Cabozantinib and radiation therapy as a combination in meningioma models were the subject of another study. When compared to either treatment alone, the researchers found that the combination treatment inhibited tumor growth more effectively [

106]. The combination treatment not only made the tumor smaller, but it also made more tumor cells die off and made less angiogenesis. Cabozantinib and radiation therapy might work together in meningiomas, according to these findings [

107].

Preclinical research has also looked into how cabozantinib affects meningioma metastasis and invasive behavior. Treatment with cabozantinib inhibited meningioma cell migration and invasion, which may have slowed the spread of the tumor [

108]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are essential for tumor invasion and metastasis, were also inhibited in expression by cabozantinib, which is associated with tumor invasiveness. Cabozantinib has been shown to be effective at preventing meningioma growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis in preclinical studies. Cabozantinib's therapeutic potential in meningioma patients should be further investigated and evaluated through clinical trials based on these findings [

109]. The importance of cabozantinib as a promising targeted therapy for meningiomas is emphasized by the preclinical evidence, paving the way for its potential clinical application [

110].

7. Molecular Targets and Pathways Impacted by Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib is a potent inhibitor of multiple kinases that targets a variety of proteins and pathways that are essential for the growth and progression of cancer [

111]. Multiple molecular targets, including MET, AXL, VEGFR, RET, FGFR1, ROS1, TYRO3, KIT, TRKB, FLT-3, and TIE-2, are inhibited by it. The angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, and modulation of the tumor microenvironment all depend on these proteins [

112]. Cabozantinib inhibits tumor angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, and immunomodulation by targeting MET. Oncologic pathways associated with T-cell exclusion and immune evasion are disrupted when the AXL receptor is inhibited [

113]. Tumor angiogenesis is slowed down by inhibiting VEGFR1, and RET targeting is especially effective in treating medullary thyroid cancer. Additionally, cabozantinib affects tumor angiogenesis and invasiveness by inhibiting FGFR1 [

114]. Cabozantinib has inhibited ROS1, TYRO3, MER, KIT, TRKB, FLT-3, and TIE-2 in preclinical models. These results point to a possibility of broad- spectrum activity against various types of cancer. By inhibiting tyrosine kinase receptor signaling, cabozantinib also affects the tumor microenvironment, making tumor cells more susceptible to immune-mediated cell death [

115].

7.1. MET Signaling Pathway and its Role in Meningioma Growth

Meningioma development relies heavily on the MET signaling pathway. A receptor tyrosine kinase that is activated by its ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), MET is also known as the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) [

116]. MET dimers and autophosphorylates upon HGF binding, triggering a series of intracellular signaling events that control various cellular processes.

Abnormal activation of the MET pathway has been observed in meningiomas and has been linked to tumor growth and invasion [

117]. Meningioma tissues have been found to have elevated levels of MET expression and activation, particularly in tumors that are higher-grade and recurrent [

118]. Meningioma cell proliferation, survival, and migration are all aided by MET activation, which contributes to tumor growth and progression.In meningiomas, MET signaling plays a crucial role in angiogenesis, which is the development of new blood vessels to support tumor growth [

119]. The production of pro-angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which encourage the formation of new blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment, is sped up when MET is activated. The tumor's expansion and survival are aided by this enhanced angiogenesis, which supplies it with vital oxygen and nutrients [

120].

Meningioma cell motility and invasion have also been linked to the HGF-MET signaling axis. Meningioma cells are better able to move around when MET is activated, allowing them to invade surrounding tissues and potentially spread to other locations. The infiltrative growth pattern of meningiomas makes it difficult to treat them effectively because of their invasive nature [

120]. Complete surgical resection may not always be possible. As a result, focusing on the MET pathway might be a way to prevent meningioma invasion and improve patient outcomes.

Figure: Select signaling pathways are activated and bound by HGF/MET, resulting in significant cancer survival-promoting pathways [122].

Figure: Select signaling pathways are activated and bound by HGF/MET, resulting in significant cancer survival-promoting pathways [122].

In addition, the development of resistance to targeted therapies like cabozantinib has been linked to the activation of the MET pathway. To circumvent the inhibitory effects of cabozantinib, meningiomas can activate the HGF-MET pathway as a compensatory mechanism, resulting in treatment resistance and disease progression [

121]. Effective therapeutic strategies for overcoming this resistance require an understanding of the mechanisms that underlie it. Due to the significance of the MET pathway in meningioma growth, targeted therapies against MET are being investigated for use in the treatment of these tumors [

122]. Preclinical and clinical studies are being conducted on a number of MET inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The goal of these inhibitors is to prevent meningioma cell growth, migration, and invasion by inhibiting MET activation and subsequent signaling [

123].

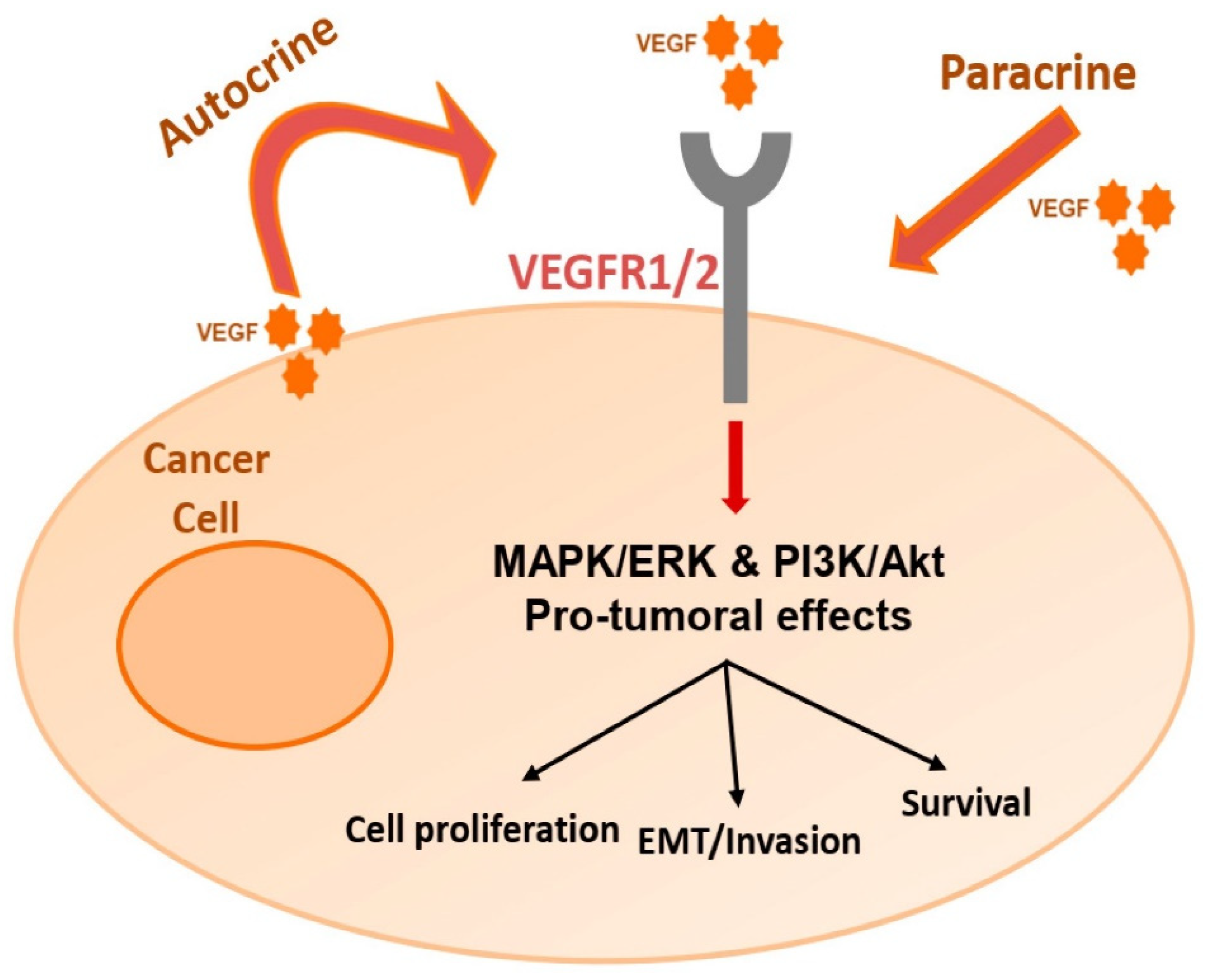

7.2. VEGFR2 Inhibition and Anti-Angiogenic Effects

Cabozantinib's anti-angiogenic and inhibition of VEGFR2 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2) effects are crucial components of its cancer treatment mechanism. Cabozantinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that also inhibits other receptor tyrosine kinases and targets VEGFR2. An important receptor in the regulation of angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from existing ones, is VEGFR2. By providing oxygen and nutrients to the expanding tumor mass, angiogenesis is essential to tumor growth and progression [

124]. The activation of VEGFR2 by its ligands, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), initiates signaling pathways that encourage the proliferation, migration, and formation of vessels in endothelial cells [

125].

Cabozantinib suppresses angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFR2, interfering with the VEGF-mediated signaling cascade [

126]. By preventing the formation of new blood vessels in the tumor's microenvironment, this blockade of VEGFR2 signaling prevents the tumor from receiving the oxygen and nutrients it needs to continue growing. Cabozantinib has anti-angiogenic effects that go beyond inhibiting VEGFR2 [

127]. Other receptor tyrosine kinases that are involved in angiogenesis and tumor progression, such as MET and AXL, are also inhibited by cabozantinib. Cabozantinib's anti-angiogenic effects are further enhanced by its inhibition of these additional targets [

128].

Figure: effects of the VEGF-VEGFR relationship in cancer cells that are not angiogenic. Autocrine-paracrine loops mediated by VEGF directly affect and encourage tumor cell survival, proliferation, and invasion. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor); mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt [130].

Figure: effects of the VEGF-VEGFR relationship in cancer cells that are not angiogenic. Autocrine-paracrine loops mediated by VEGF directly affect and encourage tumor cell survival, proliferation, and invasion. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor); mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt [130].

Cabozantinib has the potential to enhance the efficacy of other anticancer treatments by disrupting the tumor's blood supply, preventing metastasis and promoting tumor regression [

129]. Additionally, as the development of new blood vessels is necessary for tumors to obtain nutrients and for cancer cells to escape the effects of therapy, it has been recognized that targeting angiogenesis is an important strategy for preventing the development of drug resistance [

130]. Cabozantinib's anti-angiogenic properties and inhibition of VEGFR2 justify its use in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, among other types of cancer. It is common knowledge that these tumors are extremely vascularized and rely on angiogenesis for growth and progression [

131]. Cabozantinib has the potential to halt tumor growth and disrupt tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFR2 and other important receptor tyrosine kinases.

7.3. Other Potential Targets and Combinatorial Approaches

Cabozantinib has been found to target a number of other proteins and pathways involved in the development and progression of cancer. This is in addition to its effects on VEGFR2 and other receptor tyrosine kinases [

132]. Cabozantinib's therapeutic potential is increased by these additional targets, which also open up possibilities for cancer treatment combinations. MET, a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis, is one of cabozantinib's most important targets [

133]. In a variety of cancers, MET activation is frequently associated with a poor prognosis and resistance to therapy. Cabozantinib's anticancer effects can be enhanced by inhibiting MET signaling, which blocks the pathways involved in tumor progression.

Cabozantinib has another target in AXL. AXL is associated with tumor immune evasion, treatment resistance, and oncogenic pathways. Cabozantinib's inhibition of AXL has the potential to boost the immune response against the tumor and defeat these resistance mechanisms [

134]. In preclinical models, cabozantinib has also been shown to inhibit FGFR1, ROS1, TYRO3, MER, KIT, TRKB, FLT-3, and TIE-2. These targets are involved in a number of signaling pathways that have been linked to the onset and progression of cancer [

135]. Cabozantinib's anticancer effects may be enhanced and resistance mechanisms associated with these targets may be overcome by inhibiting these proteins.

Cabozantinib's ability to target multiple targets makes it an appealing option for combination therapies. It is possible to simultaneously target multiple pathways by combining cabozantinib with other targeted agents or conventional chemotherapy drugs, enhancing the anti-tumor effects and potentially overcoming resistance [

136]. The tumor's specific molecular characteristics and the underlying resistance mechanisms can be tailored to combinational approaches. In addition, preclinical studies have demonstrated promising outcomes when cabozantinib is used in conjunction with immunotherapies [

137]. Cabozantinib's immunomodulatory effects, such as its influence on the tumor microenvironment and immune cell functions, have the potential to enhance the immune response against the tumor when combined with immunotherapies like immune checkpoint inhibitors [

138].

Generally, the multi-target nature of cabozantinib encompasses not only its effects on VEGFR2, but also MET, AXL, FGFR1, and other signaling proteins. Combinatorial approaches, such as combining therapies with other targeted agents or immunotherapies, are made possible by these additional targets [

139]. Cabozantinib's therapeutic efficacy can be enhanced and outcomes in cancer treatment can be improved by investigating these potential targets and combinatorial strategies.

8. Mechanisms of Cabozantinib Resistance

Cabozantinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor that targets MET, Axl, RET, and the VEGF receptor, has shown promise in the treatment of RCC and HCC. However, cabozantinib resistance eventually develops in almost all patients [

140]. Although the mechanisms behind cabozantinib resistance are still poorly understood, they may be comparable to those of other TKIs.The immune cells' compensatory upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors in response to VEGFR blockade, activation of the HGF-MET pathway, transcriptional activation of FGF/FGFR1 expression, YAP/TBX5-driven mechanism of FGFR1 and FGF overexpression, involvement of cancer stem cells (CSCs), overexpression of FGFR1, and factors affecting the systemic exposure of cabozantinib, such as a high-fat diet or Combination therapy is being looked at as a way to get past resistance [

141]. It is possible to minimize tumor resistance without overlapping toxicities by combining cabozantinib with other medications. This allows for the simultaneous targeting of various cellular signaling pathways [

142].

8.1. Acquired Resistance in Meningiomas

In the treatment of meningiomas, acquired resistance to cabozantinib presents a significant obstacle. Cabozantinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to be effective against meningiomas and other types of cancer [

143]. However, resistance to cabozantinib can develop over time, limiting its therapeutic efficacy and accelerating the progression of the disease [

144]. The activation of alternative signaling pathways is one mechanism by which cabozantinib resistance in meningiomas occurs. To circumvent the inhibition of the primary targets of cabozantinib, such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), meningioma cells can activate these alternative pathways [

145]. Cabozantinib's effectiveness is reduced because tumor cells can use these alternative pathways to boost their own growth and survival [

146]. Cabozantinib's target genes undergo genetic alterations as an additional mechanism. Resistance can develop as a result of, for instance, mutations in genes like MET and VEGFR2. These mutations may alter cabozantinib's ability to bind to its intended target, reducing its inhibitory activity and hindering its ability to inhibit the targeted pathway [

147].

To increase the efflux of cabozantinib from within the cells, meningioma cells can also upregulate the expression of drug efflux pumps, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) [

148]. Cabozantinib's effectiveness as a treatment for cancer decreases as a result of this active pumping out of the drug into the tumor cells. Meningioma cabozantinib resistance may also be caused by the activation of survival pathways. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which promotes cell survival and resistance to apoptosis (programmed cell death), can be activated by meningioma cells [

149]. Cabozantinib's cytotoxic effects can be countered and its efficacy reduced by activating survival pathways. Resistance formation is also significantly influenced by the tumor microenvironment. Phenotypic changes in meningiomas include the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is associated with increased invasiveness and therapy resistance [

150]. Resistance to cabozantinib may be exacerbated by these alterations in the tumor microenvironment.

Researchers are actively investigating a variety of approaches to overcome resistance to cabozantinib in meningiomas. Utilizing combination therapies, in which cabozantinib is paired with other targeted agents or standard chemotherapy drugs, is one strategy [

151]. Combination therapies aim to overcome resistance and enhance antitumor effects by simultaneously targeting multiple signaling pathways [

152]. The creation of novel cabozantinib derivatives is yet another strategy. The drug is currently being modified by researchers to increase its selectivity and potency. To overcome acquired resistance, these novel derivatives may be able to target additional signaling pathways or circumvent resistance mechanisms [

153]. In resistant meningiomas, alternative pathways that are activated are also being investigated. The growth and survival of resistant tumor cells can be inhibited by identifying and blocking these alternative pathways, potentially restoring cabozantinib sensitivity. Additionally, attempts are being made to circumvent drug efflux mechanisms. To prevent the active removal of cabozantinib from the cells, researchers are investigating inhibitors of drug efflux pumps like P-gp [

154]. Cabozantinib's intracellular concentration can be increased by inhibiting drug efflux, enhancing its effectiveness against resistant meningioma cells [

155].

Figure: Microenvironment immune to meningiomas. Illustration showing the interactions between various immune cells seen in the tumor microenvironment of meningiomas and tumor cells [157].

Figure: Microenvironment immune to meningiomas. Illustration showing the interactions between various immune cells seen in the tumor microenvironment of meningiomas and tumor cells [157].

Different mechanisms such as the activation of alternative signaling pathways, genetic mutations, drug efflux, activation of survival pathways, and changes in the tumor microenvironment, are involved in the development of acquired resistance to cabozantinib in meningiomas [

156]. Combination therapy, the creation of novel derivatives, the targeting of alternative pathways, and the inhibition of drug efflux mechanisms are some of the strategies that are being actively investigated by researchers to combat resistance [

157,

158].

8.2. Potential Strategies to Overcome Resistance

Researchers are actively investigating a variety of potential strategies to enhance the drug's efficacy or develop combination therapies in order to overcome cabozantinib resistance in meningiomas:

Combination therapy, in which cabozantinib is used in conjunction with other targeted agents or conventional chemotherapy drugs, is one promising strategy [

159]. Combination therapies aim to overcome resistance and enhance antitumor effects by simultaneously targeting multiple signaling pathways. In preclinical studies, for instance, the combination of cabozantinib with immunotherapies or inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has demonstrated synergistic effects [

160]. The resistance mechanisms may be circumvented and treatment outcomes may be enhanced by this synergy.

The creation of novel cabozantinib derivatives is one more area of investigation. In order to produce derivatives with increased selectivity and potency, researchers are actively modifying the drug's structure [

161]. In order to overcome acquired resistance, these novel derivatives may be able to target additional signaling pathways or circumvent the resistance mechanisms that are present in meningiomas [

162]. Another promising strategy is to target alternative pathways that are activated in resistant meningiomas. It is possible to stop resistant tumor cells from growing and staying alive by finding and stopping these other signaling pathways [

163]. Cabozantinib's effectiveness can be restored through such interventions, resulting in improved therapeutic outcomes.

Researchers hope to overcome the acquired resistance to cabozantinib in meningiomas by investigating these potential strategies [

164]. In order to improve the efficacy of cabozantinib and broaden the range of treatment options available to patients with resistant meningiomas, new cabozantinib derivatives, combination therapies, and the identification and targeting of alternative pathways all hold promise [

165]. Improved therapeutic outcomes for patients with this challenging form of cancer are the ultimate goals of ongoing research in this field, which aims to optimize these strategies and further advance our comprehension of the mechanisms by which cabozantinib resistance develops [

166].

9. Safety and Tolerability of Cabozantinib in Meningiomas

Cabozantinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that has been approved by the FDA to target MET, Axl, RET, and the VEGF receptor [

167]. It has been approved for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and progressive metastatic medullary thyroid cancer [

168]. Cabozantinib's safety and tolerability in patients with recurrent or progressive meningioma are currently the subject of a phase II clinical trial. Cabozantinib's safety and tolerability in meningiomas are unknown, but a case study showed that intracranial meningiomas regressed after treatment with the drug [

169].

Cabozantinib has been shown to be effective in treating metastatic progressive thyroid cancer and intracranial meningiomas in a patient, in addition to the approved indications [

170]. It is important to note that cabozantinib is metabolized by CYP3A4 and multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2), so its systemic exposure can be increased by inhibitors of these enzymes and other factors like a high- fat diet or hepatic impairment [

171]. To reduce tumor resistance to cabozantinib, combination therapy is being investigated. It may be possible to target various cellular signaling pathways, overcome resistance, and avoid overlapping toxicities by combining cabozantinib with other medications [

172].

9.1. Common Adverse Events and Management Strategies

Cabozantinib, a medication used to treat cancer, has been linked to a number of common side effects that patients may experience during their treatment. It is fundamental for patients and medical services suppliers to know about these unfavorable occasions and carry out fitting administration systems to guarantee ideal patient consideration [

173]. Cabozantinib treatment is frequently associated with fatigue as a side effect. Rest and getting enough sleep should be the top priorities for tired people [

174]. Managing fatigue can also be made easier by conserving energy and not working too hard. Additionally, mild exercises or walks, as well as regular, within their capabilities, physical activity, may help alleviate symptoms. Patients should seek guidance and additional evaluation from their healthcare provider if their fatigue becomes severe or persistent [

175].

Diarrhea is another frequent side effect of cabozantinib. By drinking a lot of fluids, patients should concentrate on staying hydrated. Avoid spicy or fatty foods, caffeine, alcohol, and other foods and drinks that can exacerbate diarrhea. If needed, healthcare professionals may recommend over-the- counter antidiarrheal medications [

176]. Redness, swelling, pain, and sometimes peeling of the hands and feet are all symptoms of hand-foot syndrome, also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Patients should keep their hands and feet clean and dry in order to manage this condition [

177]. Symptoms can be reduced by avoiding extreme temperatures and wearing shoes that are comfortable. To alleviate discomfort, healthcare professionals may recommend moisturizers and topical corticosteroids; however, patients should consult their healthcare provider prior to applying any creams or ointments [

178].

Taking cabozantinib can also raise blood pressure. During treatment, it is important to monitor blood pressure on a regular basis. Patients with hypertension may need to adjust their medications or start antihypertensive therapy [

178]. Alterations to one's way of life, such as a low-sodium diet, regular exercise, and stress management strategies, may also be helpful in controlling hypertension. Treatment with cabozantinib has the potential to cause nausea and vomiting [

179]. Patients can try eating smaller meals more often and avoiding foods that are greasy, spicy, or heavy. To help manage these symptoms and improve overall well-being, healthcare providers may prescribe antiemetic medications [

180]. During treatment with cabozantinib, additional side effects include decreased appetite and weight loss. Patients should concentrate on eating meals and snacks that are small and high in nutrients. A dietitian can be of great assistance in addressing concerns regarding weight loss and maintaining a healthy diet during treatment [

181].

Lastly, cabozantinib may cause adverse skin reactions like rash, dryness, or itchiness. Good skincare practices should be followed by patients, such as regularly moisturizing their skin and avoiding products or soaps that can irritate the skin even more [

182]. Healthcare professionals may suggest mild topical corticosteroids or antihistamines to ease skin discomfort. When it comes to managing side effects of cabozantinib treatment, patients and healthcare providers must communicate openly and actively [

183]. Because each patient's situation is unique, different approaches to management may be used. By speedily announcing any unfriendly occasions or aftereffects to their medical services supplier, patients can get customized proposals and vital changes in accordance with their therapy plan, at last upgrading their general therapy experience [

184].

10. Future Perspectives on Safety Monitoring

There are exciting opportunities for advancements in the safety monitoring of cabozantinib and other cancer treatments in the future that have the potential to significantly improve patient care. The following are some possible future perspectives on safety monitoring:

Pharmacogenomics is a rapidly developing field in which variations in a person's genetic make-up are looked for in order to determine how they respond to particular medications [

185]. Patients who may be at a higher risk of developing adverse events or not responding to cabozantinib optimally could be identified by incorporating pharmacogenomic testing into safety monitoring protocols [

186]. Using this individualized approach, healthcare providers would be able to optimize both safety and efficacy by modifying dosages and treatment plans based on a patient's genetic profile.

Biomarkers that can predict an individual's susceptibility to certain cabozantinib-related toxicities are currently being investigated [

187]. If biomarkers that indicate toxicity risk are discovered, healthcare professionals would be able to proactively monitor and manage patients, potentially minimizing or preventing adverse events. Strategies for safety monitoring that are more specific and individualized would result from this approach [

188]. Technology advancements like wearable devices and remote monitoring platforms have the potential to significantly alter safety monitoring procedures. A continuous stream of information would be provided to healthcare providers by real- time monitoring of vital signs, symptoms, and other relevant data. This would make it possible for adverse events to be detected and treated early on [

189]. By enabling timely adjustments to treatment plans or interventions, remote monitoring would increase patient safety by facilitating prompt communication between patients and healthcare providers. The incorporation of computerized reasoning (artificial intelligence) and AI calculations into security checking frameworks can possibly change the location and expectation of unfavorable occasions [

190]. AI algorithms are capable of identifying patterns in large amounts of patient data, predicting individual patient risks, and so on. Healthcare providers can proactively identify patients who may require closer monitoring by utilizing AI capabilities, allowing for early intervention and personalized safety management [

190,

191].

Long-term safety monitoring is just as important as short-term safety monitoring during treatment to catch any delayed or late adverse events linked to cabozantinib [

192]. Future safety monitoring strategies would be informed by the establishment of robust surveillance programs that continue to monitor patients after they have completed their treatment [

193]. The growing emphasis on personalized medicine and the incorporation of cutting-edge technologies into healthcare practices are reflected in these future perspectives on safety monitoring. Safety monitoring can become more tailored, proactive, and comprehensive by utilizing genetic information, biomarkers, remote monitoring, artificial intelligence, and long-term surveillance [

194]. In the end, these advancements have the potential to enhance the overall safety profile of cabozantinib and other cancer treatments and improve patient outcomes.

11. Conclusions

In conclusion, the oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib appears to have potential as a treatment option for recurrent meningiomas. A comprehensive strategy for dealing with the complicated biology of these tumors is provided by its mechanism of action, which targets multiple signaling pathways involved in tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Case reports and small studies show that cabozantinib can prolong responses and improve outcomes in some patients with recurrent meningiomas. Tumor sizes were reduced and survival rates were increased in these patients.

However, in order to validate these findings and determine the most effective application of cabozantinib in recurrent meningiomas, additional research involving larger-scale clinical trials is required. To ensure patient tolerance and adherence, it is essential to manage side effects of cabozantinib treatment effectively. To increase cabozantinib's efficacy, future research should focus on improving treatment protocols, discovering predictive biomarkers, and investigating combination therapies. In conclusion, cabozantinib has the potential to be an efficient treatment option for recurrent meningiomas, giving patients battling this difficult condition hope. Its efficacy, safety, and optimal application will be established through ongoing research and clinical trials, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.

Funding

There was no specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, private, or non-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Not relevant.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) of this review declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- C. L. Arteaga, “Overview of epidermal growth factor receptor biology and its role as a therapeutic target in human neoplasia,” Seminars in Oncology, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 3–9, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang and P. M. Harari, “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition in Cancer Therapy: Biology, Rationale and Preliminary Clinical Results,” Investigational New Drugs, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 259–269, Aug. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. Woodburn, “The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Its Inhibition in Cancer Therapy,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 82, no. 2–3, pp. 241–250, May 1999. [CrossRef]

- L. Rogers, M. R. Gilbert, and M. A. Vogelbaum, “Intracranial meningiomas of atypical (WHO grade II) histology,” Journal of Neuro-oncology, vol. 99, no. 3, pp. 393–405, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Claus, M. L. Bondy, J. M. Schildkraut, J. L. Wiemels, M. Wrensch, and P. McL. Black, “Epidemiology of Intracranial Meningioma,” Neurosurgery, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1088–1095, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Buerki, C. Horbinski, T. J. Kruser, P. M. Horowitz, C. D. James, and R. V. Lukas, “An overview of meningiomas,” Future Oncology, vol. 14, no. 21, pp. 2161–2177, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Drummond, J.-J. Zhu, and P. McL. Black, “Meningiomas: Updating Basic Science, Management, and Outcome,” The Neurologist, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 113–130, 04. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- L. Rogers, M. R. Gilbert, and M. A. Vogelbaum, “Intracranial meningiomas of atypical (WHO grade II) histology,” Journal of Neuro-oncology, vol. 99, no. 3, pp. 393–405, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Woodburn, “The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Its Inhibition in Cancer Therapy,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 82, no. 2–3, pp. 241–250, May 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang and P. M. Harari, “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition in Cancer Therapy: Biology, Rationale and Preliminary Clinical Results,” Investigational New Drugs, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 259–269, Aug. 1999. [CrossRef]

- D. Norden, J. Drappatz, and P. Y. Wen, “Advances in meningioma therapy,” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 231–240, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Kim, “A narrative review of targeted therapies in meningioma,” Chinese Clinical Oncology, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 76, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Dedes, D. Wetterskog, A. Ashworth, S. B. Kaye, and J. S. Reis-Filho, “Emerging therapeutic targets in endometrial cancer,” Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 261–271, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Schneider and G. W. Sledge, “Drug Insight: VEGF as a therapeutic target for breast cancer,” Nature Clinical Practice Oncology, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 181–189, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. Ferrara, K. J. Hillan, H.-P. Gerber, and W. Novotny, “Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 391–400, 04. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Sledge, “VEGF-Targeting Therapy for Breast Cancer,” Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 319–323, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Galanis, “Targeting angiogenesis: Progress with anti-VEGF treatment with large molecules,” Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 507–518, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Wen, E. C. Quant, J. Drappatz, R. Beroukhim, and A. D. Norden, “Medical therapies for meningiomas,” Journal of Neuro-oncology, vol. 99, no. 3, pp. 365–378, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Kim, “A narrative review of targeted therapies in meningioma,” Chinese Clinical Oncology, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 76, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Kim, Y.-J. Bang, and K. D. Robertson, “Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy,” Epigenetics, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 15–24, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Wagle, and G. Zada, “Recent developments in chemotherapy for meningiomas: A review,” Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 35, no. 6, p. E18, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Kim, “A narrative review of targeted therapies in meningioma,” Chinese Clinical Oncology, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 76, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Han et al., “Expression and prognostic impact of immune modulatory molecule PD-L1 in meningioma,” Journal of Neuro-oncology, vol. 130, no. 3, pp. 543–552, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Preusser, P. K. Brastianos, and C. Mawrin, “Advances in meningioma genetics: Novel therapeutic opportunities,” Nature Reviews Neurology, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 106–115, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Chen et al., “Antibody–Drug Conjugate to Treat Meningiomas,” Pharmaceuticals, 21. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Pardalos, H. R. Van Loveren, and J. M. Tew, “The Surgical Resectability of Meningiomas of the Cavernous Sinus,” Neurosurgery, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 238–247, Feb. 1997. [CrossRef]

- D. Kondziolka, J. C. Flickinger, and B. Perez, “Judicious Resection and/or Radiosurgery for Parasagittal Meningiomas: Outcomes from a Multicenter Review,” Neurosurgery, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 405–413, Sep. 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. G. O. Sullivan, H. R. Van Loveren, and J. G. Tew, “The Surgical Resectability of Meningiomas of the Cavernous Sinus,” Journal of Neuro-ophthalmology, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 288, Dec. 1997. [CrossRef]

- L. N. Sekhar, G. Juric-Sekhar, H. B. Da Silva, and J. S. Pridgeon, “Skull Base Meningiomas,” Neurosurgery, vol. 62, no. Supplement 1, pp. 30–49, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Winther and S. H. Torp, “Significance of the Extent of Resection in Modern Neurosurgical Practice of World Health Organization Grade I Meningiomas,” World Neurosurgery, vol. 99, pp. 104–110, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Ichinose, T. Goto, K. Ishibashi, T. Takami, and K. Ohata, “The role of radical microsurgical resection in multimodal treatment for skull base meningioma,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 113, no. 5, pp. 1072–1078, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Sanai, M. E. Sughrue, G. Shangari, K. K. K. Chung, M. S. Berger, and M. W. McDermott, “Risk profile associated with convexity meningioma resection in the modern neurosurgical era,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 112, no. 5, pp. 913–919, 10. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Mirimanoff, D. E. Dosoretz, R. M. Linggood, R. G. Ojemann, and R. L. Martuza, “Meningioma: Analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 18–24, Jan. 1985. [CrossRef]

- C. Jackson, K. S. Tadokoro, E. W. Wang, G. A. Zenonos, C. H. Snyderman, and P. A. Gardner, “Approach selection for resection of petroclival meningioma,” Neurosurgical Focus: Video, vol. 6, no. 2, p. V9, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Pardalos, H. R. Van Loveren, and J. M. Tew, “The Surgical Resectability of Meningiomas of the Cavernous Sinus,” Neurosurgery, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 238–247, Feb. 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Wayhs, G. Lepski, L. Frighetto, and N. N. Rabelo, “Petroclival meningiomas: Remaining controversies in light of minimally invasive approaches,” Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, vol. 152, pp. 68–75, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Lunsford, “Contemporary management of meningiomas: Radiation therapy as an adjuvant and radiosurgery as an alternative to surgical removal?,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 187–190, Feb. 1994. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Barbaro, P. H. Gutin, C. B. Wilson, G. E. Sheline, E. B. Boldrey, and W. M. Wara, “Radiation Therapy in the Treatment of Partially Resected Meningiomas,” Neurosurgery, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 525–528, Apr. 1987. [CrossRef]

- M. Petty, L. E. Kun, and G. A. Meyer, “Radiation therapy for incompletely resected meningiomas,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 502–507, Apr. 1985. [CrossRef]

- R. Baskar, K. H. Lee, R. Yeo, and K. W. Yeoh, “Cancer and Radiation Therapy: Current Advances and Future Directions,” International Journal of Medical Sciences, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 193– 199, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Kondziolka and L. D. Lunsford, “Radiosurgery of Meningiomas,” Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 219–230, Jan. 1992. [CrossRef]

- H. Rodolfo et al., “Results of Linear Accelerator-based Radiosurgery for Intracranial Meningiomas,” Neurosurgery, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 446–454, Mar. 1998. [CrossRef]

- P. Metellus et al., “Evaluation of Fractionated Radiotherapy and Gamma Knife Radiosurgery in Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas: Treatment Strategy,” Neurosurgery, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 873–886, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Tanaka, T. Kobayashi, and Y. Kida, “Growth Control of Cranial Base Meningiomas by Stereotactic Radiosurgery with a Gamma Knife Unit,” Neurologia Medico-chirurgica, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 7–10, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Engelhard, “Current status of radiation therapy and radiosurgery in the treatment of intracranial meningiomas,” Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 2, no. 4, p. E8, Apr. 1997. [CrossRef]

- D. Kondziolka, L. D. Lunsford, R. J. Coffey, and J. C. Flickinger, “Stereotactic radiosurgery of meningiomas,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 552–559, Apr. 1991. [CrossRef]

- C. Cordova and S. Kurz, “Advances in Molecular Classification and Therapeutic Opportunities in Meningiomas,” Current Oncology Reports, vol. 22, no. 8, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Nigim, H. Wakimoto, E. M. Kasper, L. Ackermans, and Y. Temel, “Emerging Medical Treatments for Meningioma in the Molecular Era,” Biomedicines, vol. 6, no. 3, p. 86, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Jagannathan, R. J. Oskouian, H. K. Yeoh, D. Saulle, and A. S. Dumont, “Molecular Biology of Unreresectable Meningiomas: Implications for New Treatments and Review of the Literature,” Skull Base Surgery, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 173–187, May 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Rogers et al., “Meningiomas: Knowledge base, treatment outcomes, and uncertainties. A RANO review,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 4–23, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Rogers et al., “Meningiomas: Knowledge base, treatment outcomes, and uncertainties. A RANO review,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 4–23, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Wagle, and G. Zada, “Recent developments in chemotherapy for meningiomas: A review,” Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 35, no. 6, p. E18, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Preusser, P. K. Brastianos, and C. Mawrin, “Advances in meningioma genetics: Novel therapeutic opportunities,” Nature Reviews Neurology, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 106–115, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Tatman et al., “High-Throughput Mechanistic Screening of Epigenetic Compounds for the Potential Treatment of Meningiomas,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 10, no. 14, p. 3150, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Johnson and S. A. Toms, “Mitogenic Signal Transduction Pathways in Meningiomas: Novel Targets for Meningioma Chemotherapy?,” Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, vol. 64, no. 12, pp. 1029–1036, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. De Stricker Borch, J. Haslund-Vinding, F. Vilhardt, A. B. Maier, and T. Mathiesen, “Meningioma–Brain Crosstalk: A Scoping Review,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 17, p. 4267, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Tollefsen, O. Solheim, P. Mjønes, and S. H. Torp, “Meningiomas and Somatostatin Analogs: A Systematic Scoping Review on Current Insights and Future Perspectives,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 5, p. 4793, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Yakes et al., “Cabozantinib (XL184), a Novel MET and VEGFR2 Inhibitor, Simultaneously Suppresses Metastasis, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Growth,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 2298–2308, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Grüllich, “Cabozantinib: A MET, RET, and VEGFR2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor,” in Springer eBooks, 2014, pp. 207–214. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Yakes et al., “Cabozantinib (XL184), a Novel MET and VEGFR2 Inhibitor, Simultaneously Suppresses Metastasis, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Growth,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 2298–2308, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Rathi, B. L. Maughan, N. Agarwal, and U. Swami, “Mini-Review: Cabozantinib in the Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” Cancer Management and Research, vol. Volume 12, pp. 3741–3749, 20. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- C. Grüllich, “Cabozantinib: A MET, RET, and VEGFR2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor,” Springer eBooks, pp. 207–214, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Shao, and K. Wang, “Incidence and risk of hypertension associated with cabozantinib in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1109–1115, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Yu, D. I. Quinn, and T. B. Dorff, “Clinical use of cabozantinib in the treatment of advanced kidney cancer: Efficacy, safety, and patient selection,” OncoTargets and Therapy, vol. Volume 9, pp. 5825–5837, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Smith et al., “Cabozantinib in Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer: Results of a Phase II Randomized Discontinuation Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 412–419, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Nguyen, N. Benrimoh, Y. Xie, E. Offman, and S. Lacy, “Pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib tablet and capsule formulations in healthy adults,” Anti-Cancer Drugs, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 669–678, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. R. Belum, C. Serna-Tamayo, S. L. Wu, and M. E. Lacouture, “Incidence and risk of hand- foot skin reaction with cabozantinib, a novel multikinase inhibitor: A meta-analysis,” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 8–15, 15. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- R. Elisei et al., “Cabozantinib in Progressive Medullary Thyroid Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 31, no. 29, pp. 3639–3646, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Choueiri et al., “Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 373, no. 19, pp. 1814–1823, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Yakes et al., “Cabozantinib (XL184), a Novel MET and VEGFR2 Inhibitor, Simultaneously Suppresses Metastasis, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Growth,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 2298–2308, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiang et al., “Cabozantinib Suppresses Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by a Dual Blockade of VEGFR2 and MET,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 2959–2970, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Rathi, B. L. Maughan, N. Agarwal, and U. Swami, “Mini-Review: Cabozantinib in the Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” Cancer Management and Research, vol. Volume 12, pp. 3741–3749, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Santoni, R. Iacovelli, V. Colonna, S. G. Klinz, G. Mauri, and M. Nuti, “Antitumor effects of the multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib: A comprehensive review of the preclinical evidence,” Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 1029–1054, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., “Cabozantinib, a Multityrosine Kinase Inhibitor of MET and VEGF Receptors Which Suppresses Mouse Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization,” Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 2020, pp. 1–16, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Grüllich, “Cabozantinib: Multi-kinase Inhibitor of MET, AXL, RET, and VEGFR2,” in Recent results in cancer research, Springer Science+Business Media, 2018, pp. 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Prete, A. Cammarota, N. Personeni, and L. Rimassa, “The Role of Cabozantinib as a Therapeutic Option for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Landscape and Future Challenges,” Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, vol. Volume 8, pp. 177–191, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Markowitz and K. S. Fancher, “Cabozantinib: A Multitargeted Oral Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor,” Pharmacotherapy, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 357–369, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Small, “Treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma patients with cabozantinib, an oral multityrosine kinase inhibitor of MET, AXL and VEGF receptors,” Future Oncology, vol. 15, no. 20, pp. 2337–2348, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Vesque, M. Decraecker, and J.-F. Blanc, “Profile of Cabozantinib for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Patient Selection and Special Considerations,” Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, vol. Volume 7, pp. 91–99, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Vesque, M. Decraecker, and J.-F. Blanc, “Profile of Cabozantinib for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Patient Selection and Special Considerations,” Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, vol. Volume 7, pp. 91–99, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Mannsåker et al., “Cabozantinib Is Effective in Melanoma Brain Metastasis Cell Lines and Affects Key Signaling Pathways,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 22, p. 12296, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Lolli et al., “Impressive reduction of brain metastasis radionecrosis after cabozantinib therapy in metastatic renal carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 13, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiang et al., “Cabozantinib Suppresses Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by a Dual Blockade of VEGFR2 and MET,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 2959–2970, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Yakes et al., “Cabozantinib (XL184), a Novel MET and VEGFR2 Inhibitor, Simultaneously Suppresses Metastasis, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Growth,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 2298–2308, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Sameni et al., “Cabozantinib (XL184) Inhibits Growth and Invasion of Preclinical TNBC Models,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 923–934, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. Saydam et al., “Downregulated MicroRNA-200a in Meningiomas Promotes Tumor Growth by Reducing E-Cadherin and Activating the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway,” Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 29, no. 21, pp. 5923–5940, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Daudigeos-Dubus et al., “Dual inhibition using cabozantinib overcomes HGF/MET signaling mediated resistance to pan-VEGFR inhibition in orthotopic and metastatic neuroblastoma tumors,” International Journal of Oncology, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 203–211, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Elisei et al., “Cabozantinib in Progressive Medullary Thyroid Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 31, no. 29, pp. 3639–3646, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Vesque, M. Decraecker, and J.-F. Blanc, “Profile of Cabozantinib for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Patient Selection and Special Considerations,” Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, vol. Volume 7, pp. 91–99, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Kotecha et al., “Regression of Intracranial Meningiomas Following Treatment with Cabozantinib,” Current Oncology, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 1537–1543, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Prete, A. Cammarota, N. Personeni, and L. Rimassa, “The Role of Cabozantinib as a Therapeutic Option for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Landscape and Future Challenges,” Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, vol. Volume 8, pp. 177–191, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Personeni, T. Pressiani, and L. Rimassa, “Cabozantinib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma failing previous treatment with sorafenib,” Future Oncology, vol. 15, no. 21, pp. 2449– 2462, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Mannsåker et al., “Cabozantinib Is Effective in Melanoma Brain Metastasis Cell Lines and Affects Key Signaling Pathways,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 22, p. 12296, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]