1. Introduction

The potential of mechanochemistry, both in terms of basic research and technological application, is rapidly expanding [

1,

2,

3,

4]. With a deeper understanding of mechanisms [

5,

6,

7], concepts of precision mechanosynthesis are growing in many different technical genres. The involvement of organic chemists, e.g., organic synthesis with controlled chirality [

8], or the inclusion of high-entropy compounds containing a large number of cationic species [

9,

10,

11] has accelerated the popularity of mechanochemistry. Materials with even more complicated structures, such as double perovskites [

12] or metal organic frameworks (MOFs) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], have been mechanosynthesized. Very fine structural details, such as controlling anti-site disorder in double perovskites, have also been challenged. [

18,

19]. Increasing interest in downstream mechanochemistry is aimed at greener chemical processes, in line with the UN-led SDGs [

20,

21,

22]. Representative effects are found in industry, typically in pharmaceuticals [

3,

23,

24,

25].

The vast majority of raw materials and end products are in the form of particulate solids. However, related discussions in materials science are not always based on the powder technology point of view. The focus of this review is on the stress-induced physicochemical phenomena at the interparticle boundaries when the powder mixture is stressed. They are often based on charge transfer across the interparticle interface. Charge transfer phenomena involving solid organic species are relatively less studied, although they may play a crucial role in the synthesis of complex metal oxides. Precision control of the microstructure is also dominated by the proper choice of starting materials in conjunction with the fine redox reactions that take place within a reaction mixture under mechanical stress.

In pharmaceuticals, better dissolution and absorption of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is always explored for higher bioavailability with controlled release of the API. Many attempts have been made to amorphize the API under mechanical stress [

26,

27]. The chemical interaction at the organic-inorganic grain boundaries can be used not only for rational amorphization of the API, but also for stabilization of molecular dispersion states. Pharmaceutical technology may seem far removed from materials synthesis. However, there are many similarities when it comes to chemical interaction across the inorganic-organic particle interface under mechanical stress.

Effects of either added liquids or mechanochemical auto-liquefaction are another new perspective. Mechanisms of apparent stabilization of mechanically activated states of products are also being elucidated. Solid-state chemists know that when powdered materials are introduced into a grinding mill, not only brittle fragmentation but also inelastic, irreversible structural changes occur, accompanied by the formation of lattice defects [

28,

29,

30,

31]. These irreversible non-geometrical factors are associated with mechanochemical phenomena. However, mechanochemical phenomena are now far beyond classical crystallography. This is not only due to the assumption of amorphous or glassy states. Single-molecule mechanochemistry is one of the topics beyond the scope of classical concepts. [

4,

32,

33].

Despite such remarkable progress in mechanosynthesis at laboratory scale, we still face several difficulties to bring such technology to industrial level. Just to address this problem, a new action has been launched in 2019, funded by the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) as Action: CA18112—Mechanochemistry for Sustainable Industry (MechSustInd) [

34]. This pan-European action, which has now been extended to a global scale, has a great dynamism, especially in the field of organic synthesis-based pharmaceutical industry. Scaling up from gram to tonnage orders is sensational [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Scalability and affordability are particularly important, e.g., mechanochemistry of cellulose. [

39].

The present review focuses on some new concepts focused on those at organic-inorganic powder particle boundaries, aiming at optimizing mechanochemical processes for nanocomposites in various fields including electromagnetic functional materials and pharmaceutical technology. Emphasis is placed on the common features of chemical and electronic interactions in seemingly exotic domains. In addition, the mechanisms of apparent stabilization of nanocomposites prepared via a mechanochemical route are discussed.

2. Diversity of Mechanisms in Mechanochemistry

In recent decades, the mechanistic issues of mechanochemistry have been extensively developed. One of the major issues is the mentality of organic chemistry in the interest of rationalization of organic synthesis procedures. [

15,

22,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Most of this outstanding work has been done by organic chemists. Although the conventional boundary between organic and inorganic chemistry is becoming more and more diffuse, differences in the mental background still remain. Therefore, it is extremely important to study the change in stability and state of migration of chemical species on the surface of each society when the dissimilar particles are brought into contact and an external force is applied.

The migration of charged species is ideally dominated by the electric potential field. One of the oldest related findings of charge transfer across solid interfaces is contact electrification (CE). Phenomenologically, CE has long been known, but the mechanisms remain controversial. A recent study on the system of carbon and silicon dioxide showed that CE is partly driven by the surface dipole induced potential during contact [

44]. They further discuss the existence of a separation-dependent potential barrier at the contact interface. It has also been pointed out that CE is closely related to mechano-luminescence, i.e., the light-emitting behavior of materials upon application of mechanical stimuli [

45]. Strain-induced CE has also been reported [

46]. All these reports unequivocally indicate that charge transfer across the solid interface under mechanical stress is associated with the fundamental mechanisms of CE.

Sophisticated discussions have been made in electrochemistry. The actual electrochemical charge transfer is significantly influenced by the overpotential, whose components are very complicated. They are studied especially in the interest of all-solid rechargeable batteries [

47,

48,

49]. These works discuss charge transfer in an electrochemical context, forcing the question of how to avoid obstacles against smooth transfer of charge-bearing species, mostly Li

+, across the electrolyte-electrode interface. Plastic deformation plays an important role in interfacial charge transfer, but is mostly ignored in such an electrochemical discussion [

50].

Under mechanical stress, an additional component appears due to local deformation and associated lattice imperfections [

51,

52]. Plastic deformation is irreversible if it is highly localized, so charge transfer is inevitably affected by the resulting change in electron density distribution. Recognizing this is particularly important in mechanochemical processes, since the electrical driving force of charged species is dominated by the local electrical potential gradient and hence by the local electron density distribution. Lee et al. discussed this point in detail using in-situ compression neutron diffraction (ND) measurements [

53].

A comprehensive review of mechanochemistry with guiding terminology has been published, starting from a hierarchical representation of the main effects of mechanical action on different systems, ranging from single molecules to multiphase solid powder mixtures [

5]. Basic mechanisms of mechanochemical phenomena are also observed from the point of view of different channels of stress field relaxation [

2]. In fact, relaxation takes place during periodic stressing by different milling devices [

3]. These parallel phenomena cannot be expressed by a linear equation because they can be interpreted as multiple overlapping localized reactions [

54].

The coexistence of strong intramolecular covalent bonds and weak non-covalent intermolecular interactions characterizes the mechanochemical phenomena in organic molecular crystals [

2]. Another important concept in organic synthesis is chirality. In pharmaceutically active compounds, enantiomerically pure form is of vital importance to avoid coexistence of undesired or ineffective enantiomer, distomer with the desired one, eutomer [

55]. The control of chirality related to mechanochemistry has been studied [

56]. It is noteworthy that the control of enantiomer is associated with the near equilibrium deracemization. The latter is related to a classical concept of solution chemistry, Ostwald ripening [

57]. The control of Ostwald ripening can be controlled by grinding, a primitive action of mechanochemistry [

58].

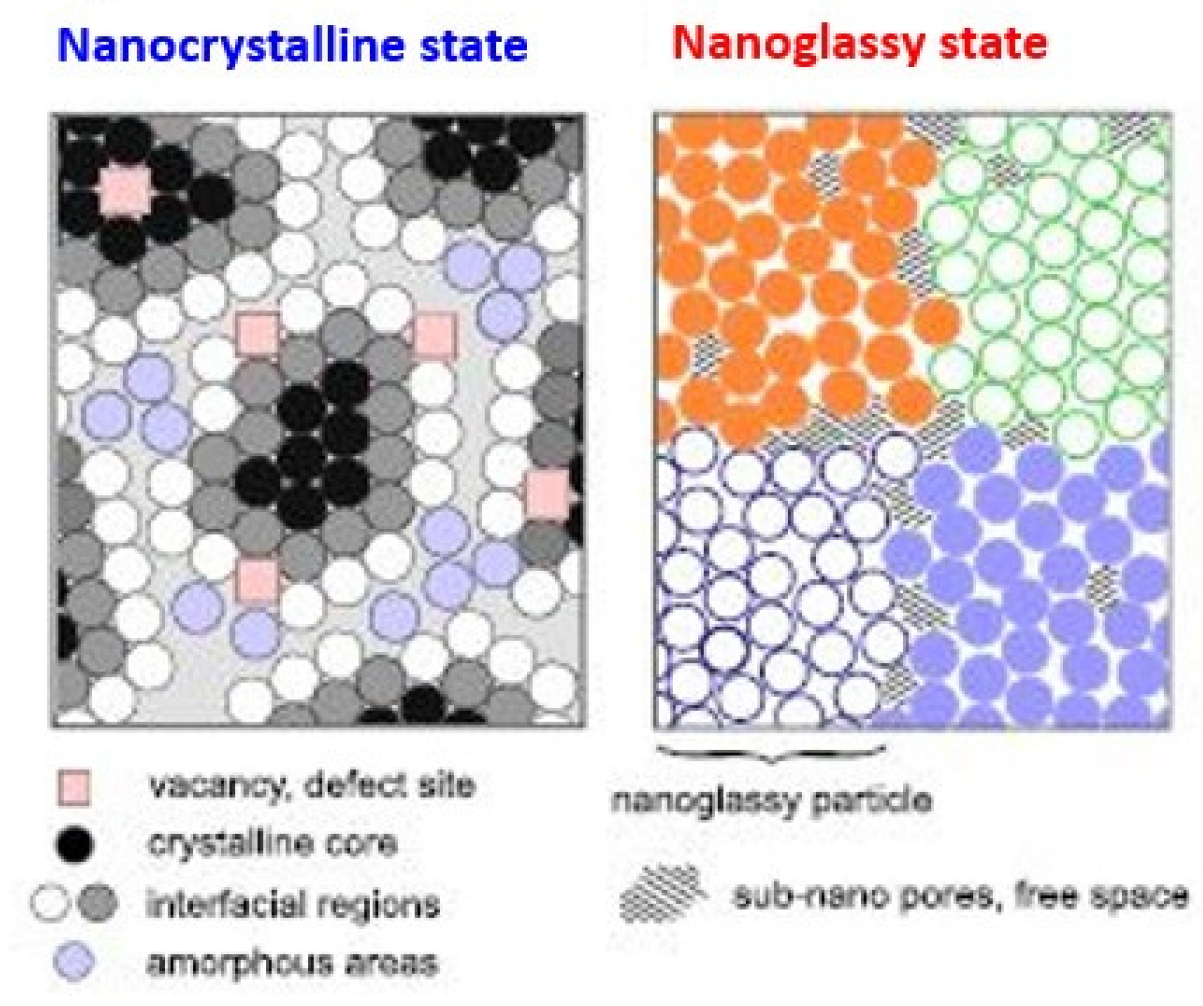

3. Nanoglassy and nanocrystalline states of complex oxides

Mechanochemical technology is developed from the formation of new complex oxides visible by conventional X-ray diffraction. More light is shed on the finer control of nanostructures. A typical example is the introduction of the concept of nanoglasses, where a solid consists of nanometer-sized glassy regions connected by interfaces of reduced density. Such glassy states could exist at room temperature due to the presence of boundaries around which nanoglass clusters are dispersed. Since nanoglass materials have been primarily associated with alloys, preparative methods have also been used in alloy preparation, such as inert gas condensation [

59] or arc melting [

60]. Since mechanochemical alloying, or mechanical alloying, has been found to be versatile for the preparation of bulk amorphous alloys [

61,

62], it is natural to prepare nanoglass materials by a mechanochemical route as well. The present author, together with his colleagues, has demonstrated some examples of this possibility [

63,

64].

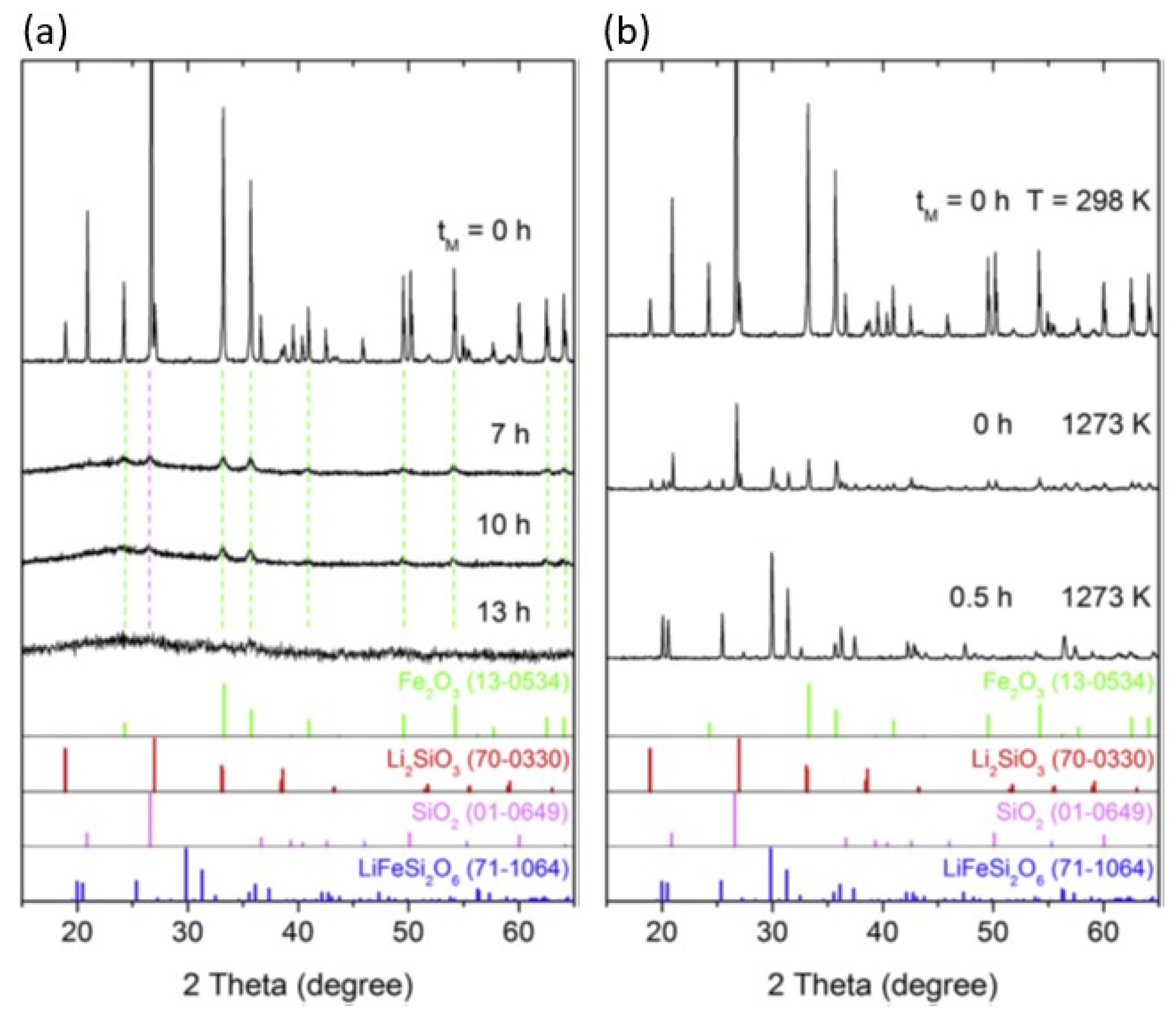

In a case study discussed below, a stoichiometric mixture for pyroxene LiFeSi

2O

6 consisting of α-Fe

2O

3, Li

2SiO

3 and SiO

2 was ground together. Mechanosynthesis proceeds with simultaneous amorphization after grinding for 13 h, as shown in

Figure 1(a) [

63]. By stopping the mechanochemical treatment for only a short time, 0.5 h, and then heating at 1000

oC in the thermal analyzer at a heating rate of 10K/min and then cooling the furnace, we obtained well-crystallized pyroxene LiFeSi

2O

6, as shown in

Figure 1(b).

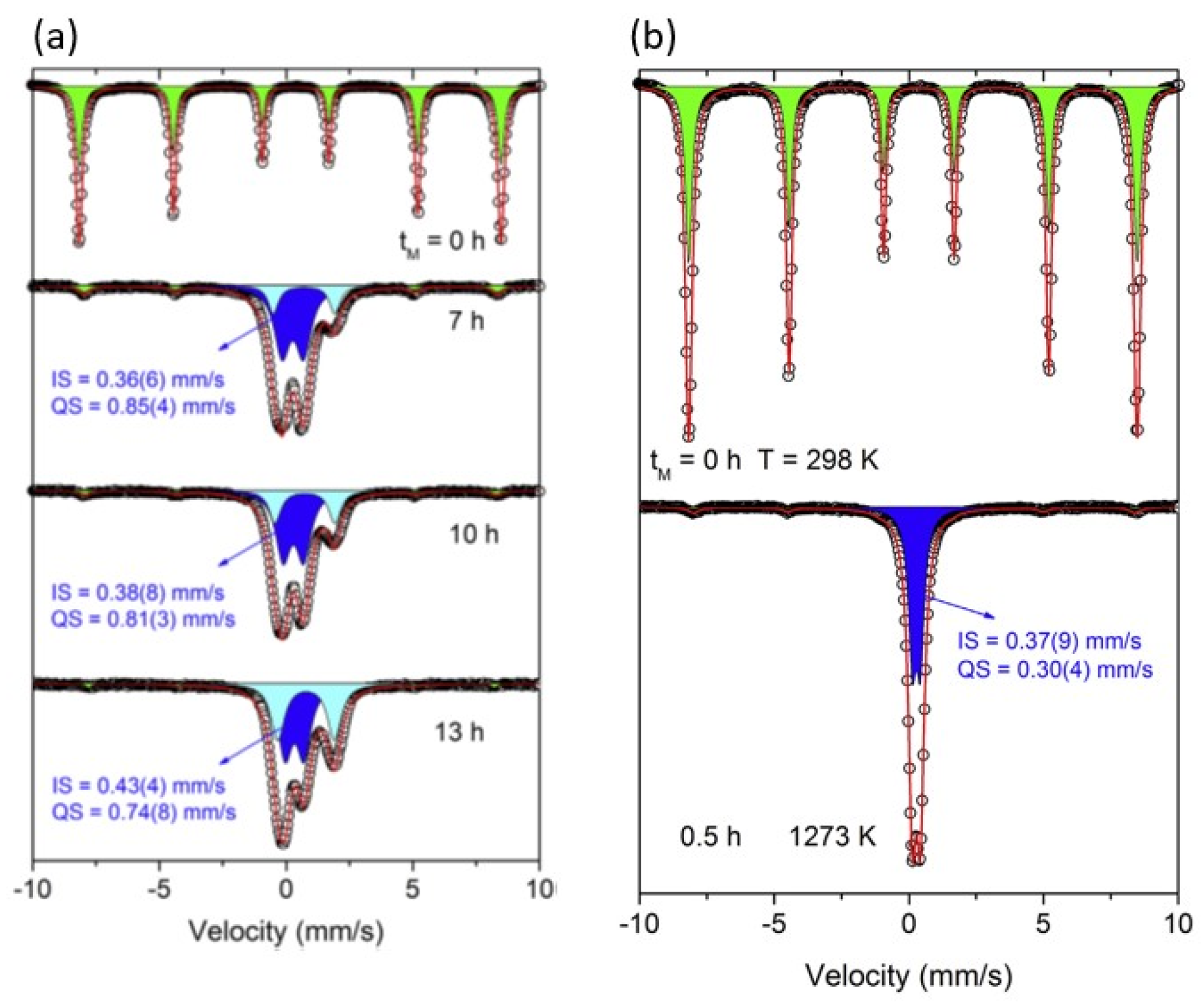

Although the milling time is short, the effect of the mechanical pre-treatment is clear. When we heated the intact mixture under the same conditions, we did not obtain the same crystalline state. A clear difference between these two products was observed in the short-range ordering around Fe by Mössbauer spectroscopy. As shown in

Figure 2(a), the mechanosynthesis products after prolonged milling exhibit significantly higher quadrupole splitting (QS) compared to that of well-crystallized pyroxene (

Figure 2(b)). This is a clear indication of highly distorted local, short-range atomic ordering and hence the glassy state.

4. Spinel and perovskite compounds with varying anti-site disorder

An even finer structural view is atomic disorder or anti-site disorder. Traditional examples are found in ferrites, where normal and inverse spinel structure are controlled during mechanosynthesis [

65,

66,

67]. Note that the products are understood as non-equilibrium states. A more complicated example can be found in perovskite. The structural control between normal and anti or reverse perovskite involves similar problems [

68,

69].

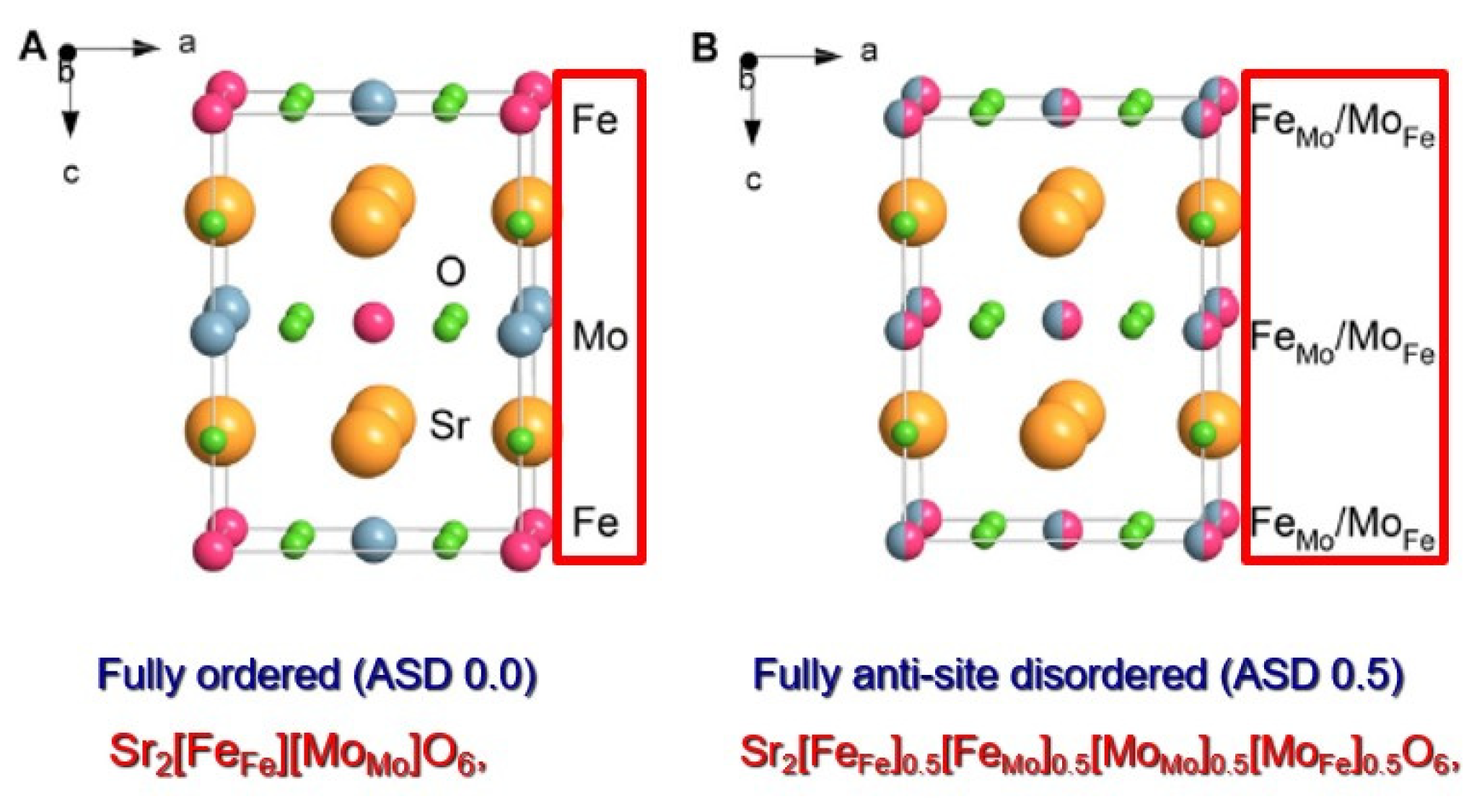

Double perovskites, A

2BB’O

6 (DPVs), are much more complicated in structure than conventional spinels. They are now under the spotlight mainly for magneto-optical or spintronic applications [

12]. Here, the specific concept of anti-site disorder (ASD) plays an important role in their attractive functional properties. Stabilization and control of ASD is one of the main issues in DPV synthesis. Baranowski et al. stated [

70] that the stability of high anti-site disorder has been discussed in terms of entropy-driven cation clustering. A further step towards the control of ASD is also being studied intensively [

71]. An explicit example of ASD is explained in

Figure 3 for Sr

2FeMoO

6 (SFMO) from our recent study [

18].

When two transition metal atoms, Fe and Mo, occupy their reserved positions, we count the ASD as zero (

Figure 3a). When they share two positions half and half, we recognize the total disorder and count ASD 0.5 (

Figure 3b).

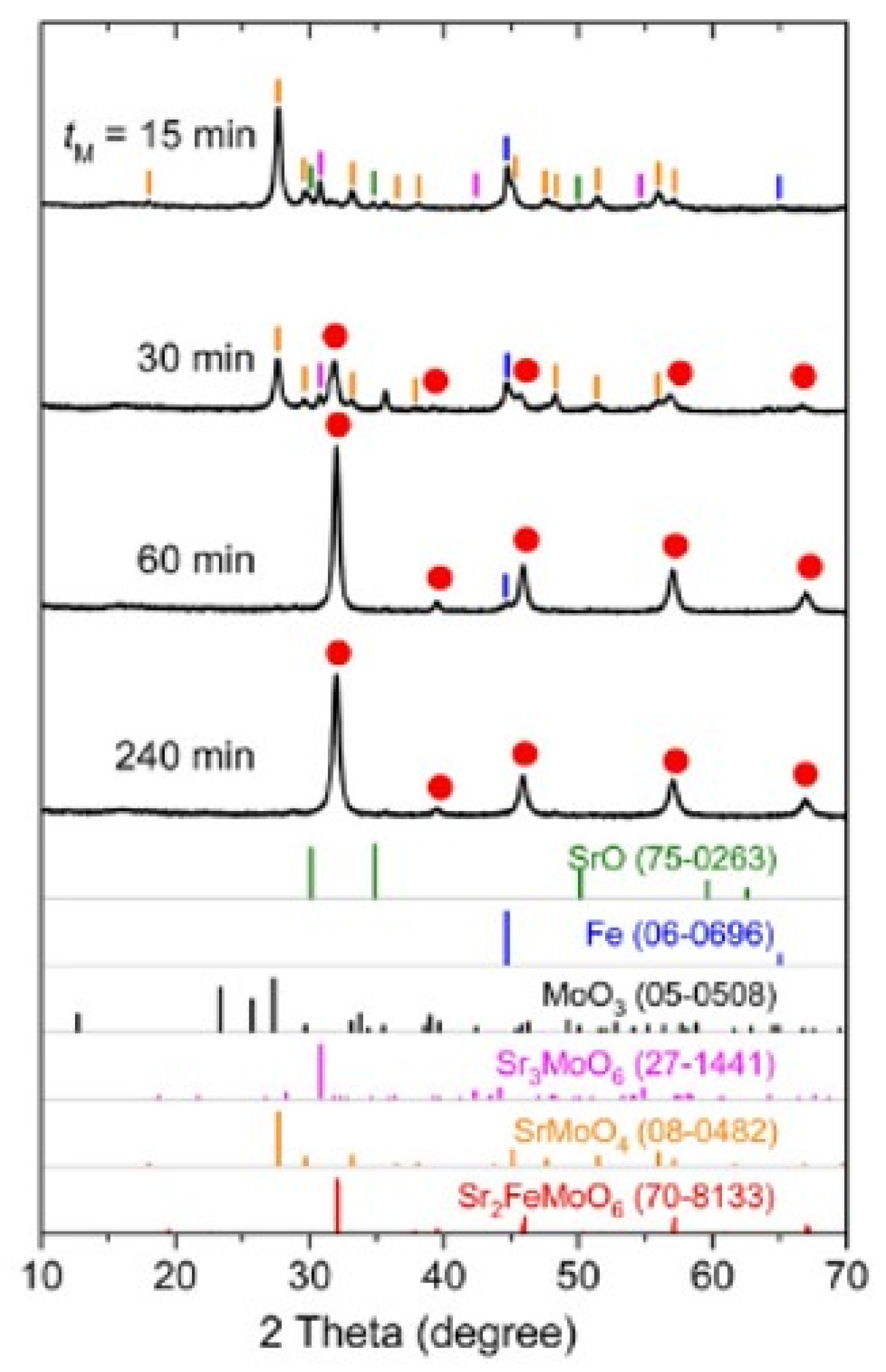

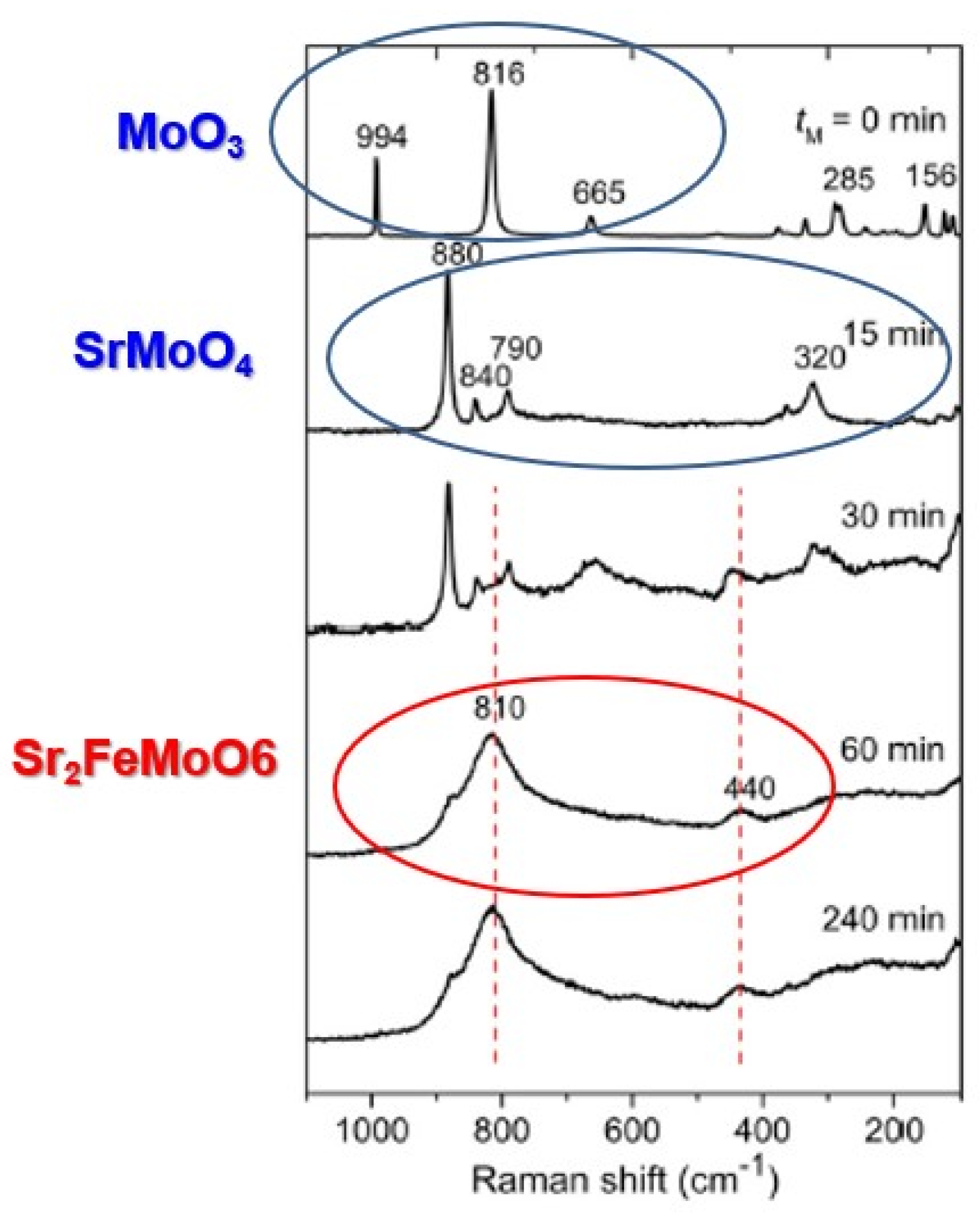

When we ground a mixture of SrO, α-Fe and MoO

3 in an exact stoichiometric ratio of SFMO in a conventional planetary mill for only 60 min, we obtained almost phase-pure SFMO as shown in

Figure 4. This was further verified by Raman lattice mode spectra as shown in

Figure 5.

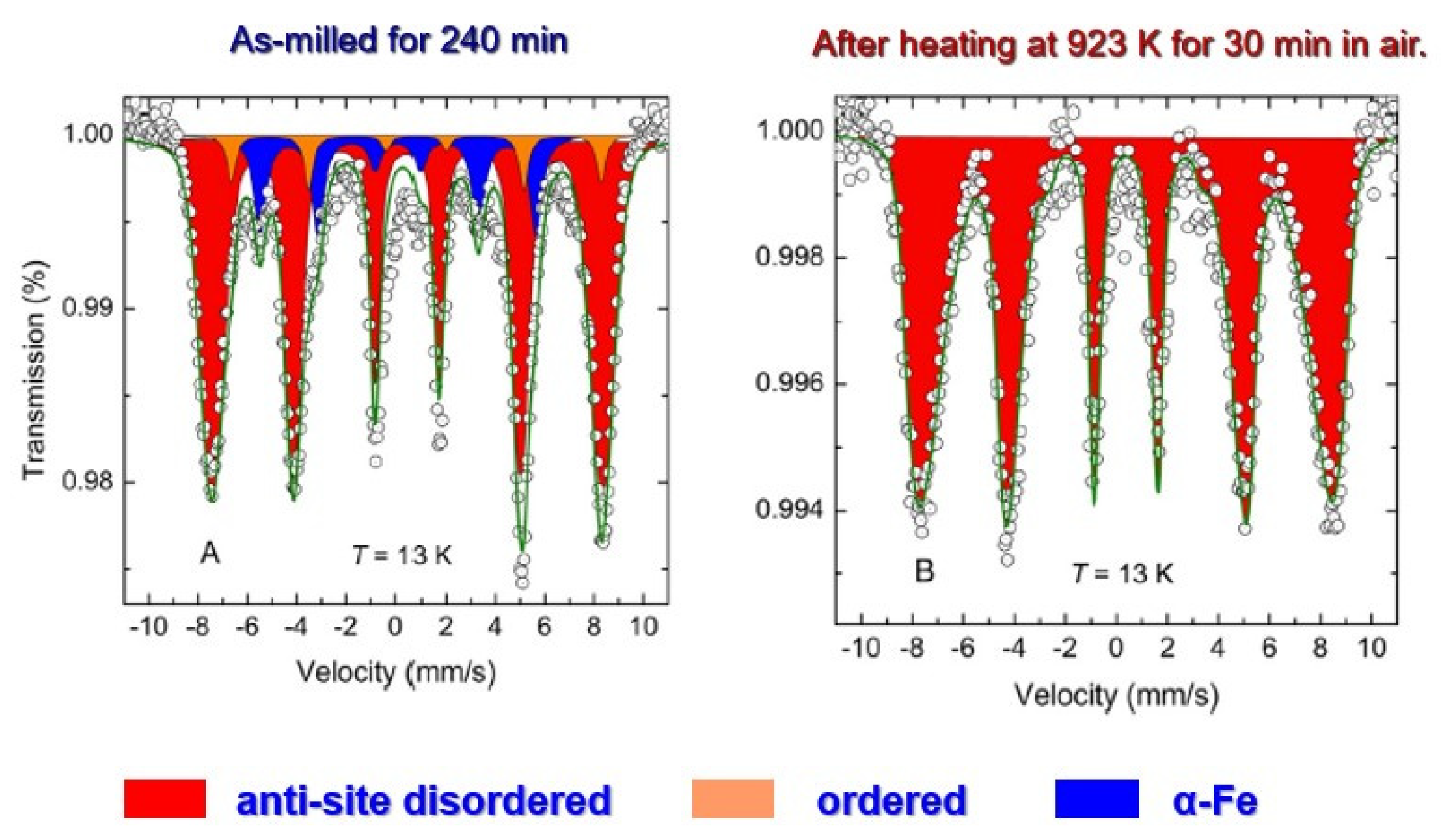

However, Mössbauer spectroscopy revealed that the as-ground product was not phase pure even after 240 min of milling (

Figure 6a). After heating the ground product at 923 K for 30 min in air, it became phase pure (

Figure 6b). The average particle size was about 20 nm even after post heat treatment. The degree of anti-site disorder was close to 0.5, indicating full disorder, independently and consistently estimated by XRD, Mössbauer spectra and magnetization data. This kind of structural state, far from equilibrium and highly disordered, has never been achieved by any previously reported method.

5. Stabilized molecular dispersion in pharmaceutic technology

As mentioned in the introduction, the application of mechanochemistry-related technology to pharmaceutics and pharmacology is a rapidly growing strong driving force of its industrialization. While the greener processing of organic synthesis for active materials is the main stream of the top-running trend of mechanochemistry to pharmaceutical technology [

34,

72], the issue of scale-up is becoming increasingly attractive [

4,

36]. The traditional stream of mechanochemical technology in pharmaceutics, i.e., amorphization of active ingredients, also needs to be re-evaluated.

In pharmaceuticals, people almost always try to make active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as amorphous as possible for the purpose of faster dissolution and bioavailability and efficiency of drug absorption [

73]. When the API is dispersed at the molecular level, i.e., in the extremes of the amorphous state, we could expect the highest possible bioavailability. The latter states, called amorphous solid dispersion [

44,

45], are achieved via a mechanochemical route [

74,

75,

76]. However, amorphous states are less stable than crystalline states. Stabilization of the state of molecular dispersion is therefore very important, but much less studied. Highly deformed, activated states are stabilized to some extent when such a state is fixed to neighboring substances, excipients [

77,

78,

79]. They are mostly based on the choice of excipient species. However, there are other ways of thinking about how to stabilize the state of molecular dispersion with a fixed excipient. Here, mechanochemical processing plays a different role.

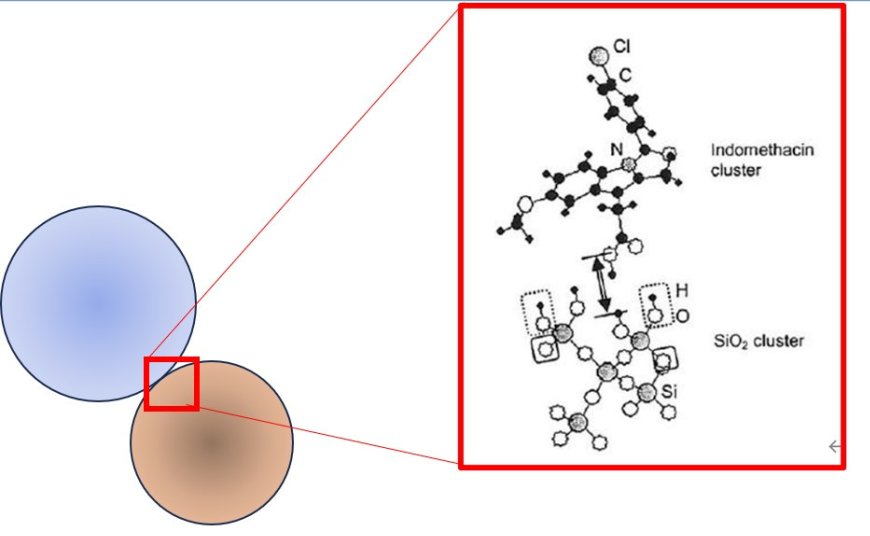

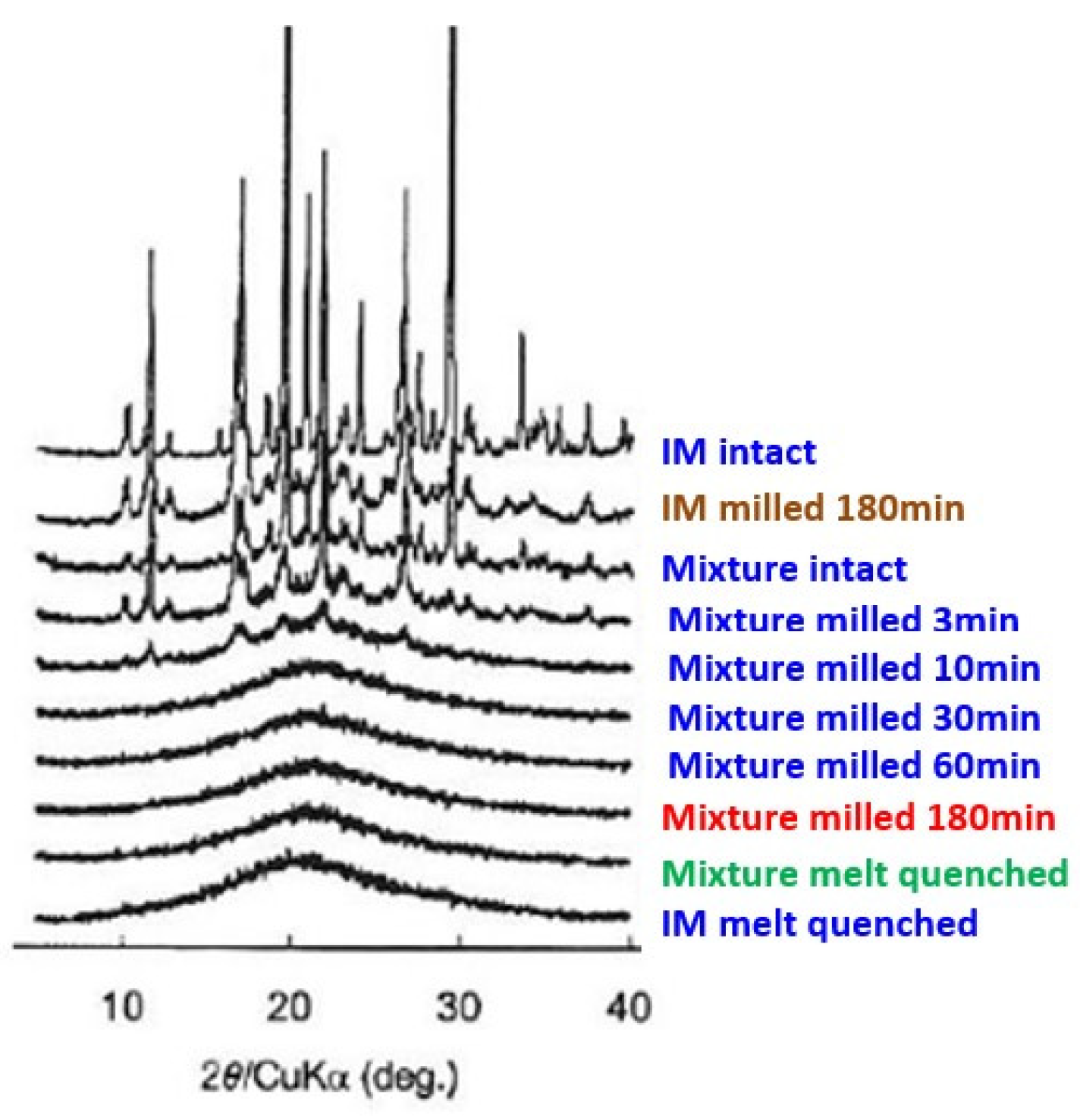

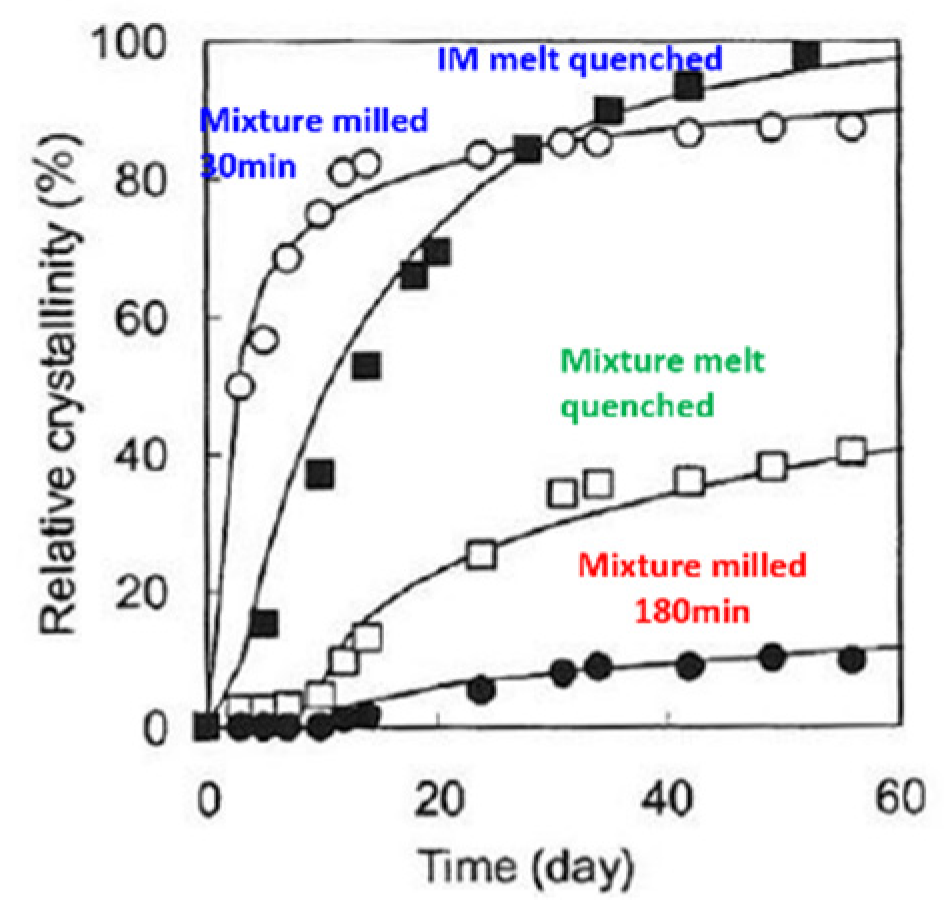

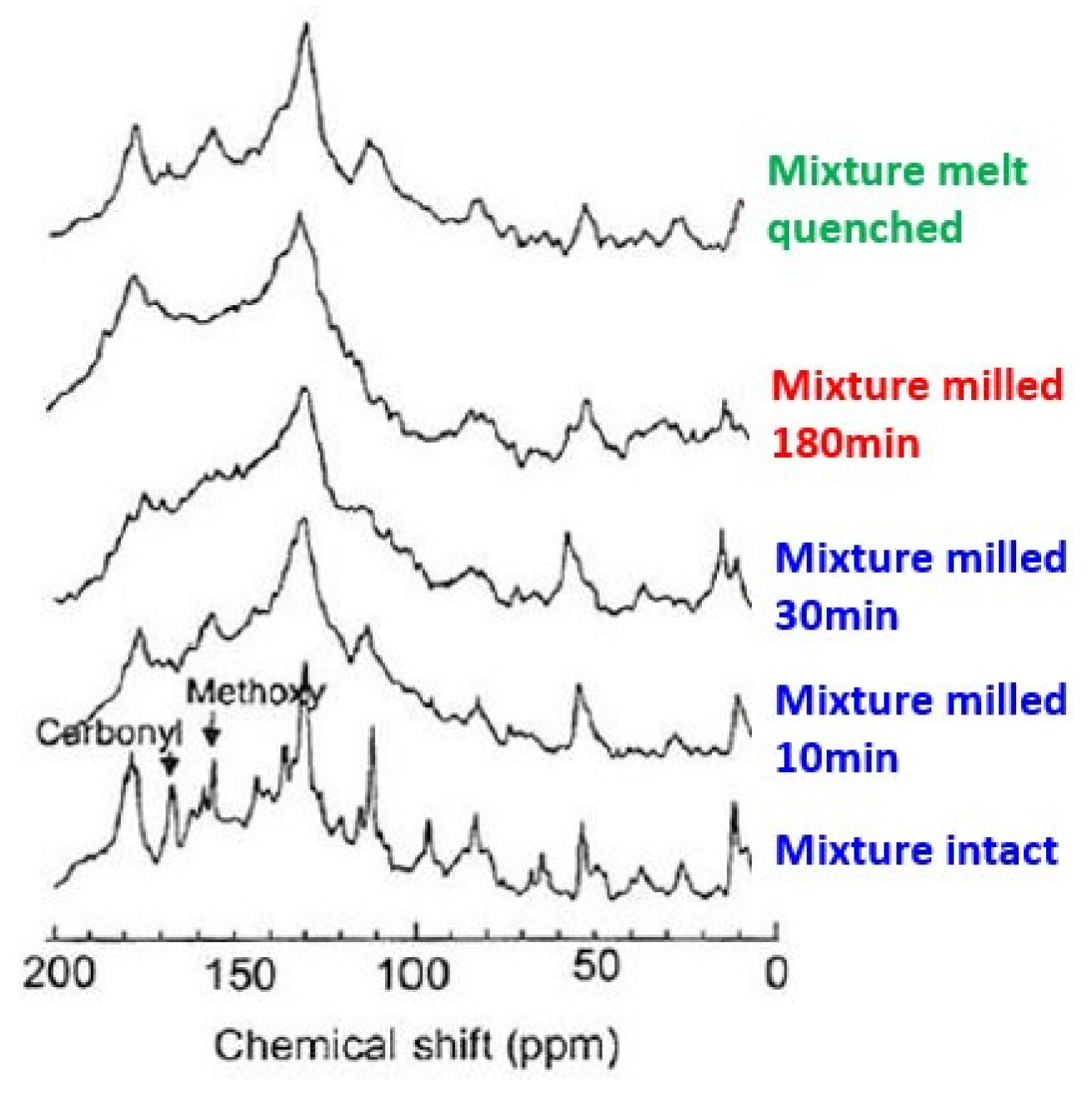

Amorphization and molecular dispersion of a popular anti-inflammatory drug, indomethacin, was subjected to amorphization via a conventional melt-quench and a mechanochemical route and compared [

74]. Crystallized indomethacin (IM) could not be amorphized when milled alone for 180 min, as shown in

Figure 7. When IM was ground together with fumed silica, it apparently amorphized after 30 min of grinding. The state of amorphization by conventional melt quenching was also shown for comparison. In the latter case, the coexistence of fumed silica did not play a significant role.

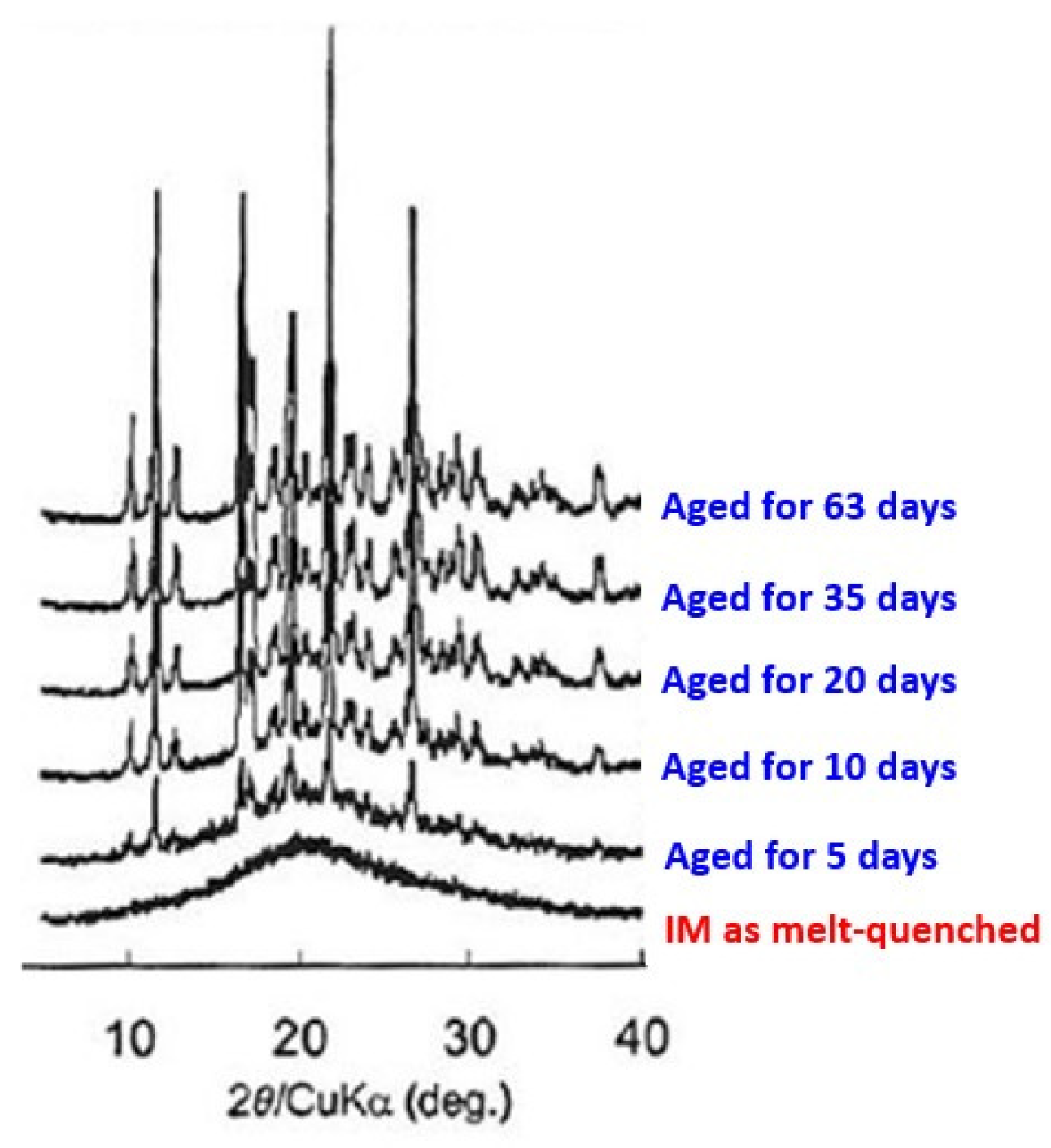

Upon exposure of once amorphized compounds, the amorphized drugs tend to recrystallize. When amorphized IM was exposed via melt quenching in the well-controlled environment of 30

oC and 11% relative humidity, recrystallization became apparent after 5 days and was completely recrystallized after 3 days, as shown in

Figure 8.

As shown in

Figure 9, the recrystallization kinetics of amorphized IM was very different depending on the amorphization method. The degree of crystallinity was suppressed to about 10% even after 3 months when co-milling was extended to 180 min.

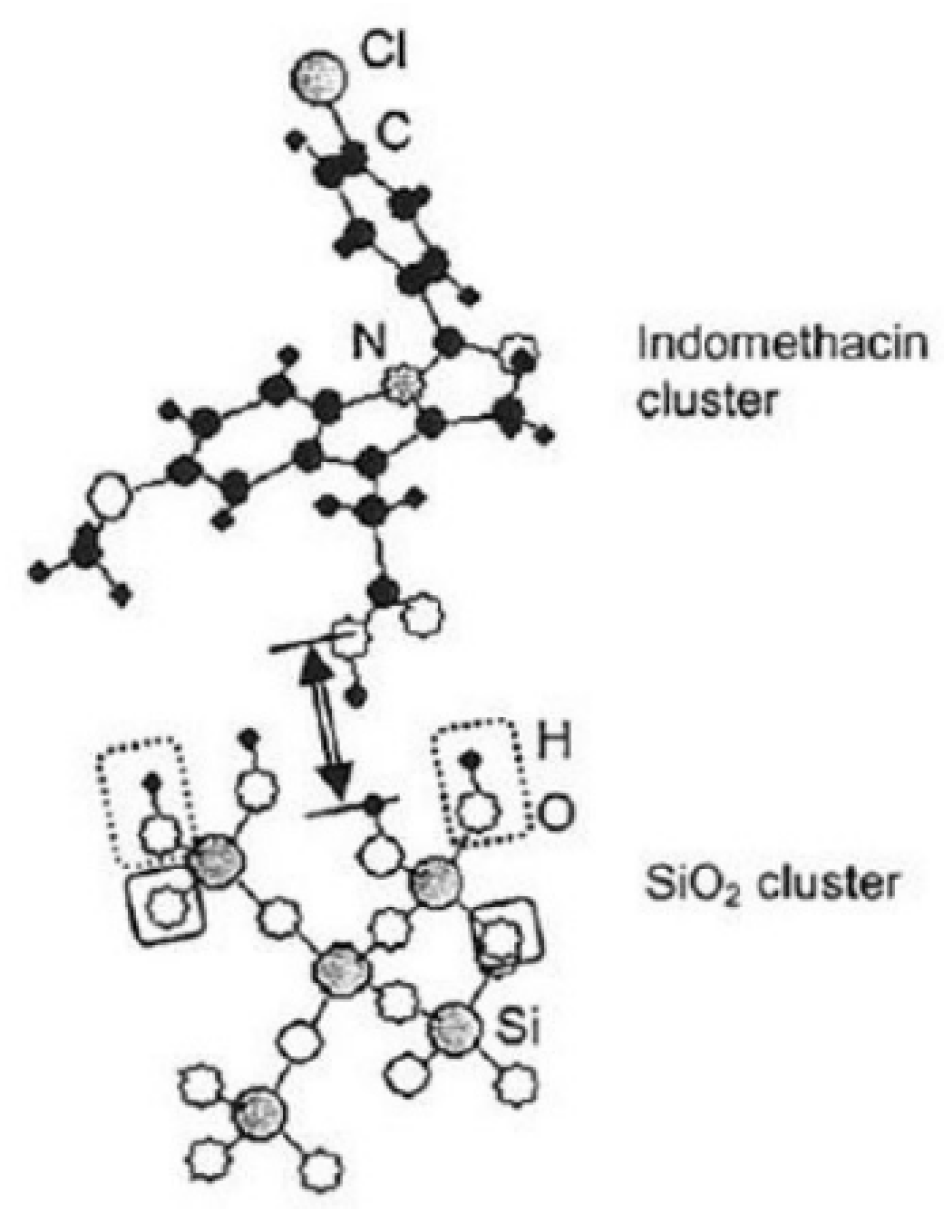

Unfavorable fast recrystallization is associated with the debris of the surviving crystallite region, which serves as the active site for recrystallization. A closer look is needed to elucidate the state of specific chemical interaction between the active drag materials and the excipients, i.e., IM and fumed silica in this case. Hydrogen bonding is the main chemical interaction between them, as shown schematically in

Figure 10 [

80].

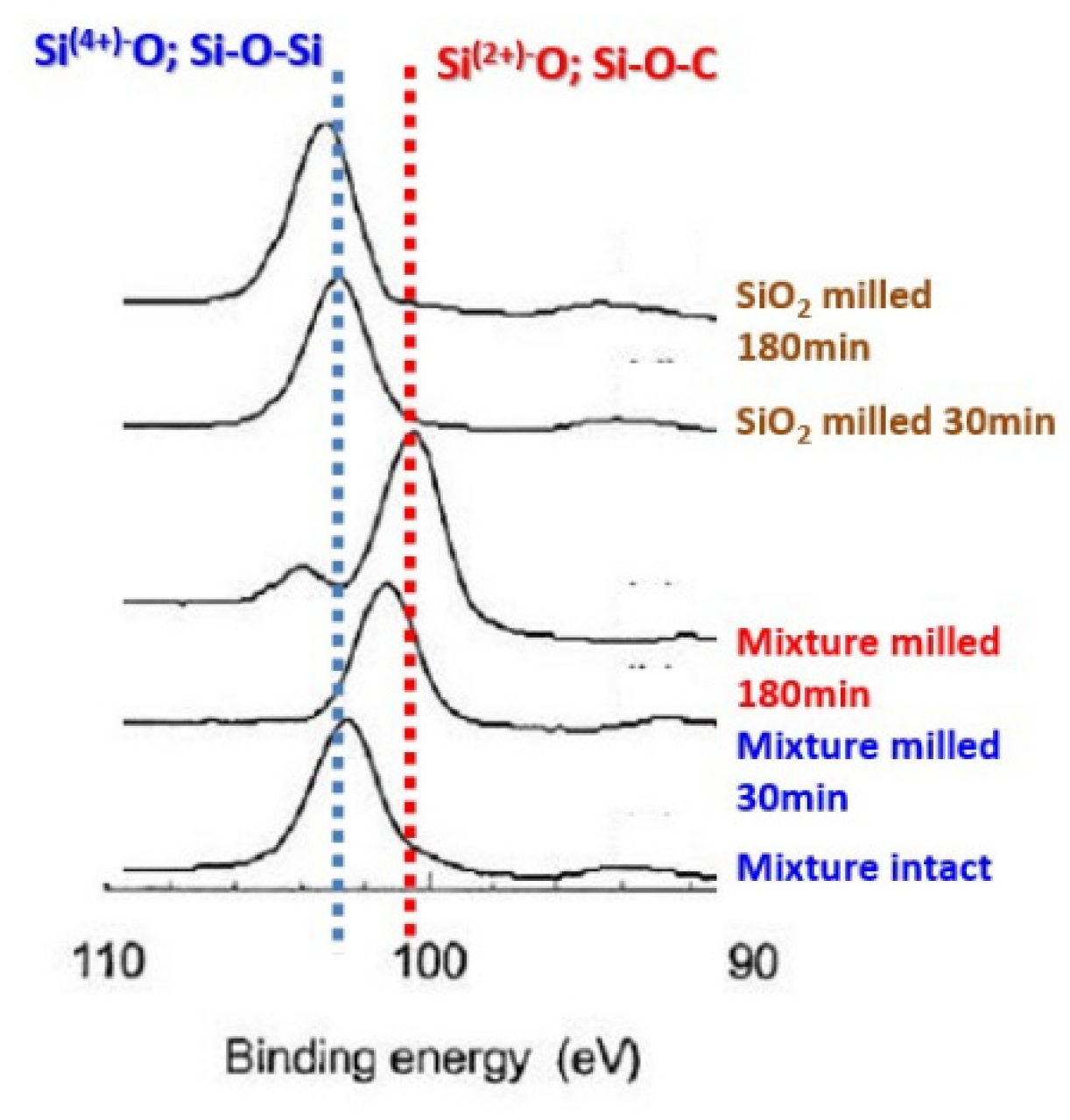

The interaction state also changes with the milling time of the mixture. As shown in

Figure 11 [

81], XPS profiles indicate the decrease of Si2p binding energy, which indicates the gain of electron density, i.e., the apparent reduction of silicon ionic states. The difference was further confirmed by

13C-CP/MAS NMR as shown in

Figure 12 [

39].

6. Involvement of liquids and auto-liquefaction

A mechanochemical process is considered green, especially in organic synthesis, mainly due to the absence of solvents. On the other hand, the addition of small amounts of liquids, not always considered as solvents, often shows positive effects [

2]. Since most of the mechanochemical processing is carried out with a milling machine, it is worthwhile to briefly compare dry and wet milling. There are several aspects related to mechanochemical effects.

The type and amount of mechanical stress is common to particle size reduction, which is the primary purpose of conventional milling. A detailed simulation study discusses the velocity dependence of the coefficient of friction, which was similar to the variation of the coefficient of friction with sliding velocity as described using the lubrication theory [

82]. The intensity of the mechanochemical effects is easily comparable to those of conventional mechanical milling of powders. The energy efficiency of the pilot mill has been discussed to obtain the power demand during wet and dry grinding processes [

83]. This is also common to all processes that use grinding equipment. A more specific comparison between wet and dry grinding has been made in the pharmaceutical industry and has provided useful information in this area [

84]. Attention has also been paid to electrostatic charging in dry grinding. Even finer processing, such as DNA extraction from fungal spores, the merits of selecting dry versus wet milling was thoroughly discussed [

85].

The concept of liquid assisted grinding (LAG), proposed by Friscic et al., [

86,

87], is associated with the mechanosynthesis of cocrystals. The role of liquid is far more than that as lubricant. Effects of liquid addition are particularly remarkable for cocrystals with more than two components, due to acceleration of inclusion of participating molecular species and subtle difference in the phase stability with a partial dissolution of particular constituent.

There are quite different aspects of liquid phase involvement in organic mechanosynthesis, i.e., the emergence of the liquid phase during mechanochemical synthesis starting from dry powder mixtures. An example of this is the solid-solid cocrystal formation between thymol and hexamethylenetetramine, which proceeds by the formation of a metastable binary low-melting eutectic [

88,

89]. The use of the in situ formed liquid phase has another advantage for solvent-insoluble solid phases, since the liquid phase appears only as an intermediate during the mechanochemical process, while the solid phase is the final product [

90]. Mechanically induced reactions between triphenylphosphine and organic halides are also suspected of passing through the low-temperature eutectics, e.g., triphenylphosphine-organic bromide systems during ball milling. Formation of the eutectic liquid phase may be local and transient in the grinding jars. However, the participation of such a liquid phase can significantly accelerate the mechanochemical reactions [

91,

92]. Similar mechanochemical reactions by the participation of eutectic liquid phase are also found for wider genres of organic synthesis, such as Diels-Alder reactions [

43].

Liquid phase intermediates are interpreted as charge transfer complexes (CTCs) in liquid or solid states. The formation of such CTCs is often attributed to the π - π interaction being dominated by the orbital overlap rather than the electron density on the molecular orbital, which is verified experimentally by the process of CTC and DFT calculations. The intensity of the π - π interaction is further influenced by the cationic properties of the functional groups [

93].

7. Apparent stabilization of mechanochemical products

Products of mechanosynthesis are categorically unstable or metastable if we follow the classical thermodynamic definition. On the other hand, all solid powdery substances are unstable or metastable because they have surfaces where the original states of coordination are disturbed. A perfect single crystal of infinite size is the only stable solid that does not exist. In this section, relative stability or kinetic stability is discussed in connection with the products of mechanochemical processing, some of which are shown above.

As for the explicit case studies mentioned in sections 3, 4 and 5, three different mechanisms of apparent stabilization could be demonstrated. In the case of exterior tiles, their joints play an important role. As shown in

Figure 13, nanoglass materials consist of glassy nanograins surrounded by grain boundaries, just like the tiles and joints [

53]. While glassy states are always less stable than crystalline states, coexisting grain boundaries buffer the recrystallization of the glassy parts, so the nanoglass states maintain their metastability.

Increase in the anti-site disorder to its full disorder after heating cannot be fully explained on the theoretical basis. One possible explanation is the contribution of configurational entropy [

70,

95,

96]. In fact, the concept of High Entropy Alloy (HEA) is rapidly gaining acceptance, where alloys with more than three cationic species remain stable simply because of the entropy contribution to the thermodynamics of multicomponent alloys. [

97]. It should be noted, however, that there are many factors involved, including differences in atomic size or the amount of deformation. The concept is also extended from alloys to complex oxides, nitrides or other complex compounds under the concept of High Entropy Materials (HEM). [

11]. A similar concept is applicable to more complex interfacial phenomena including biomaterials [

98]. Mechanosynthesis of HEM has also been reported [

53].

In the case of molecular dispersion, the molecular crystal of the drug is gradually disintegrated under mechanical stress. Its debris is further broken down into the states of independent molecules, which inevitably interact with the coexisting excipient. The drug-excipient bond is non-covalent, typically hydrogen bonds (HBs) as extensively studied in the interest of controlled release of drugs [

99,

100,

101]. The strength of HBs varies greatly depending on the structural disorder of the excipient solid and/or coexisting OH groups or hydronium ions. This is similar to those discussed for molecular sieves, where molecules are trapped and confined in the micropores of the zeolite. [

102]. These molecular-substrate interactions hinder the recrystallization of molecular crystals and thus stabilize the highly active molecular dispersion state. It should also be noted that the mechanochemical process not only facilitates the formation of HBs, but also provides different options for their intensity.

8. Concluding remarks and outlook

Microscopic transport of chemical species in and across particulate solids is promoted under applied external mechanical stress. Combined with other parameters such as temperature and exposure to electromagnetic radiation, the control of short- and long-range ordering in nanostructured materials via a mechanochemical process becomes widely available in an affordable manner. With a step-by-step understanding of the actual processes involved, these processing technologies will become even more affordable to produce the products we need today and in the near future in more environmentally benign ways. Of particular importance are the proper selection of starting materials and well-targeted characterization techniques to know what is really happening in a grinding pot. The importance of their appropriate combination was emphasized by referring to three case studies from the authors’ recent works. Thus, we can anticipate a bright future of application of mechanochemical principles in line with the concept of SDGs in a really affordable way.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks the coworkers appeared in the case studies introduced, among others, Dr. Tomoyuki Watanabe (Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited), Dr. Vladimir Šepelák (Institute of Nanotechnology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology), and Dr. Erika Tóthová (Institute of Geotechnics, SAS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sepelak, V.; Duvel, A.; Wilkening, M.; Becker, K.D.; Heitjans, P. Mechanochemical reactions and syntheses of oxides. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42, 7507–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldyreva, E. Mechanochemistry of inorganic and organic systems: what is similar, what is different? Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42, 7719–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaz, P.; Achimovicova, M.; Balaz, M.; Billik, P.; Cherkezova-Zheleva, Z.; Criado, J.M.; Delogu, F.; Dutkova, E.; Gaffet, E.; Gotor, F.J.; et al. Hallmarks of mechanochemistry: from nanoparticles to technology. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42, 7571–7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagola, S. Outstanding Advantages, Current Drawbacks, and Significant Recent Developments in Mechanochemistry: A Perspective View. Crystals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. , M.A.A.; V., B.E.; M., B.A.; F., E.; V., B.V. Tribochemistry, Mechanical Alloying, Mechanochemistry: What is in a Name? Front Chem 2021, 9, 685789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaz, M.; Balema, V.; Blair, R.G.; Boldyreva, E.; Bolm, C.; Braunschweig, A.B.; Carpick, R.W.; Craig, S.L.; Emmerling, F.; Ewen, J.P.; et al. Shear processes and polymer mechanochemistry: general discussion. Faraday Discuss 2023, 241, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradipta, M.F.; Watanabe, H.; Senna, M. Semiempirical computation of the solid phase Diels–Alder reaction between anthracene derivatives and p-benzoquinone via molecular distortion. Solid State Ion. 2004, 172, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Li, J.; Fei, J.; Ji, Q.; Hill, J.P. Nanoarchitectonics for Dynamic Functional Materials from Atomic-/Molecular-Level Manipulation to Macroscopic Action. Adv Mater 2016, 28, 1251–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea I, F.R. , Baltatescu O, Soare V, Chelariu R, Carcea I. High entropy alloys. J. Optoelectornics Adv. Mater. 2013, 15, 761–767. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Xing, Y.; Dai, F.-z.; Wang, H.; Su, L.; Miao, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, X.; Yao, L.; et al. High-entropy ceramics: Present status, challenges, and a look forward. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 385–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Ma, X.; Zhao, K.; Li, X.; Su, D. High-entropy materials for energy-related applications. iScience 2021, 24, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha-Dasgupta, T. Double perovskites with 3d and 4d/5d transition metals: compounds with promises. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangu, K.K.; Maddila, S.; Mukkamala, S.B.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. A review on contemporary Metal–Organic Framework materials. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2016, 446, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, X.; Huang, H.; Guo, X.; Qiao, Z.; Zhong, C. Solvent-free mechanochemical route for the construction of ionic liquid and mixed-metal MOF composites for synergistic CO2 fixation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 3180–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T. New opportunities for materials synthesis using mechanochemistry. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amery, N.; Abid, H.R.; Al-Saadi, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, S. Facile directions for synthesis, modification and activation of MOFs. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 17, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, B.; Zilic, D.; Huskic, I.; Germann, L.S.; Fidelli, A.M.; Muratovic, S.; Loncaric, I.; Etter, M.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Barisic, D.; et al. Controlling the Polymorphism and Topology Transformation in Porphyrinic Zirconium Metal-Organic Frameworks via Mechanochemistry. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 19214–19220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tothova, E.; Duvel, A.; Witte, R.; Brand, R.A.; Sarkar, A.; Kruk, R.; Senna, M.; Da Silva, K.L.; Menzel, D.; Girman, V.; et al. A Unique Mechanochemical Redox Reaction Yielding Nanostructured Double Perovskite Sr2FeMoO6 With an Extraordinarily High Degree of Anti-Site Disorder. Front Chem 2022, 10, 846910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Hou, Y.-J.; Wang, J.-F. Anti-site Defect Versus Grain Boundary Competitions in Magnetoresistance Behavior of Sr2FeMoO6 Double Perovskite. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2021, 34, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Sajna, K.V.; Satoh, Y.; Sato, K.; Shimada, S. By-Product-Free Siloxane-Bond Formation and Programmed One-Pot Oligosiloxane Synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2017, 56, 3168–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Han, L.; Bai, H.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zai, M.; Ma, H.; Li, Y. Introducing Mechanochemistry into Rubber Processing: Green-Functionalized Cross-Linking Network of Butadiene Elastomer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8053–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Adams, C.J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friscic, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K.D.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; et al. Mechanochemistry: opportunities for new and cleaner synthesis. Chem Soc Rev 2012, 41, 413–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, M.; König, B. Organic Synthesis without Conventional Solvents. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 4213–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankrushina NA, L.O. , Shakhtschneider TP. Physical Activation of Extraction and Organic Synthesis Processes. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandichhor, R.B., A.; Diorazio, L.; Dunn, P.; Fraunhoffer, K.; Gallou, F.; Hayler, J.; Hickey, M.; Hinkley, B.; Humphreys, L.e.a. Green Chemistry Articles of Interest to the Pharmaceut. Org. Prog. Res. Dev. 2010, 14, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baghel, S.; Cathcart, H.; O'Reilly, N.J. Polymeric Amorphous Solid Dispersions: A Review of Amorphization, Crystallization, Stabilization, Solid-State Characterization, and Aqueous Solubilization of Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II Drugs. J Pharm Sci 2016, 105, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumondor, A.C.F.; Dhareshwar, S.S.; Kesisoglou, F. Amorphous Solid Dispersions or Prodrugs: Complementary Strategies to Increase Drug Absorption. J Pharm Sci 2016, 105, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazesh, S.; Grasjo, J.; Berggren, J.; Alderborn, G. Comminution-amorphisation relationships during ball milling of lactose at different milling conditions. Int J Pharm 2017, 528, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpotyuk, O.; Bujňáková, Z.L.; Baláž, P.; Shpotyuk, Y.; Demchenko, P.; Balitska, V. Impact of grinding media on high-energy ball milling-driven amorphization in multiparticulate As4S4/ZnS/Fe3O4 nanocomposites. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 3610–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, F.P.; Ciarbonetti, A.; Sánchez, P.J.; Huespe, A.E. A phase-field/gradient damage model for brittle fracture in elastic–plastic solids. Int. J. Plast. 2015, 65, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, K.R.; Srinivasa, A.R. On the thermomechanics of materials that have multiple natural configurations Part I: Viscoelasticity and classical plasticity. Zeitschrift für angewandte Mathematik und Physik ZAMP 2004, 55, 861–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avvakumov, E. , Senna, M. , Kosova, N.,. Softmechanochemical_Synthesis. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Suslick, K.S. Mechanochemistry and sonochemistry: concluding remarks. Faraday Discuss 2014, 170, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, J.G.; Halasz, I.; Crawford, D.E.; Krupicka, M.; Baláž, M.; André, V.; Vella-Zarb, L.; Niidu, A.; García, F.; Maini, L.; et al. M: Research in Focus.

- ). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 8–9. [CrossRef]

- Gomollon-Bel, F. Mechanochemists Want to Shake up Industrial Chemistry. ACS Cent Sci 2022, 8, 1474–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colacino, E.; Isoni, V.; Crawford, D.; García, F. Upscaling Mechanochemistry: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Industry. Trends Chem. 2021, 3, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin Pedrazzo, A.; Cecone, C.; Trotta, F.; Zanetti, M. Mechanosynthesis of β-Cyclodextrin Polymers Based on Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 14881–14889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekalo, I.; Martinez, V.; Karadeniz, B.; Orešković, P.; Drapanauskaite, D.; Vriesema, H.; Stenekes, R.; Etter, M.; Dejanović, I.; Baltrusaitis, J.; et al. Scale-Up of Agrochemical Urea-Gypsum Cocrystal Synthesis Using Thermally Controlled Mechanochemistry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 6743–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuga, S.; Wu, M. Mechanochemistry of cellulose. Cellulose 2019, 26, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.; Eddleston, M.D. Introductory lecture: Mechanochemistry, a versatile synthesis strategy for new materials. Faraday Discuss 2014, 170, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friscic, T.; James, S.L.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Bolm, C.; Jones, W.; Mack, J.; Steed, J.W.; Suslick, K.S. Highlights from Faraday Discussion 170: challenges and opportunities of modern mechanochemistry, Montreal, Canada, 2014. Chem Commun (Camb) 2015, 51, 6248–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Matsui, E.; Ishiyama, Y.; Senna, M. Solvent free mechanochemical oxygenation of fullerene under oxygen atmosphere. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 8132–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Hiraoka, R.; Senna, M. A Diels–Alder reaction catalyzed by eutectic complexes autogenously formed from solid state phenols and quinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 4481–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulbago, B.J.; Chen, J. Nonlinear potential field in contact electrification. J. Electrost. 2020, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Wang, Y. Contact electrification induced mechanoluminescence. Nano Energy 2022, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, M.; Widenor, R.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.W.; Lacks, D.J.; Sankaran, R.M. Strain-induced reversal of charge transfer in contact electrification. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2012, 51, 2695–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, L.H.J.; Danilov, D.L.; Eichel, R.A.; Notten, P.H.L. An advanced all-solid-state Li-ion battery model. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, D.; Niessen, R.A.H.; Notten, P.H.L. Modeling All-Solid-State Li-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sångeland, C.; Mindemark, J.; Younesi, R.; Brandell, D. Probing the interfacial chemistry of solid-state lithium batteries. Solid State Ion. 2019, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.H.; Ciucci, F. Electro-chemo-mechanical modeling of solid-state batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, S.

- interface at room temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, A304-306, 39–44.

- M, S. Charge transfer and hetero-bonding across the solid–solid interface at room temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 304-306, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Song, G.; Gao, M.C.; Ouyang, L.; An, K.; Fensin, S.J.; Liaw, P.K. Effects of Zr addition on lattice strains and electronic structures of NbTaTiV high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. : A 2022, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, S. Chemical powder technology—a new insight into atomic processes on the surface of ne particles. Adv. Powder Technol. 2002, 13, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xie, W.; Jiao, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.A.; Lei, H.; Shen, X. Conformational adaptability determining antibody recognition to distomer: structure analysis of enantioselective antibody against chiral drug gatifloxacin. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 39534–39544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellogg, R.M. Practical Stereochemistry. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorduin, W.L.; Vlieg, E.; Kellogg, R.M.; Kaptein, B. From Ostwald ripening to single chirality. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009, 48, 9600–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwaha, M.; Katsuno, H. Mechanism of Chirality Conversion by Grinding Crystals: Ostwald Ripening vs Crystallization of Chiral Clusters. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.X.; Vainio, U.; Puff, W.; Würschum, R.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, D.; Ghafari, M.; Jiang, F.; Sun, J.; Hahn, H.; et al. Correction to Atomic Structure and Structural Stability of Sc75Fe25 Nanoglasses. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 5058–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Kong, F.L.; Zhu, S.L.; Shalaan, E.; Al-Marzouki, F.M. Production methods and properties of engineering glassy alloys and composites. Intermetallics 2015, 58, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Q. Size dependence of nanostructures: Impact of bond order deficiency. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2007, 35, 1–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleos CM, T.D. Liquid crystals from hydrogen-bonded amphiphiles. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 6, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turianicová, E.; Witte, R.; Da Silva, K.L.; Zorkovská, A.; Senna, M.; Hahn, H.; Heitjans, P.; Šepelák, V. Combined mechanochemical/thermal synthesis of microcrystalline pyroxene LiFeSi2O6 and one-step mechanosynthesis of nanoglassy LiFeSi2O6−based composite. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 707, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Jhung, S.H. Applications of metal-organic frameworks in adsorption/separation processes via hydrogen bonding interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 310, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šepelák, V.; Indris, S.; Bergmann, I.; Feldhoff, A.; Becker, K.D.; Heitjans, P. Nonequilibrium cation distribution in nanocrystalline MgAl2O4 spinel studied by 27Al magic-angle spinning NMR. Solid State Ion. 2006, 177, 2487–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šepelák, V.; Indris, S.; Heitjans, P.; Becker, K.D. Direct determination of the cation disorder in nanoscale spinels by NMR, XPS, and Mössbauer spectroscopy. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 434-435, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiraju, G.R. Crystal engineering: a holistic view. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2007, 46, 8342–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Zhu, J.; Lin, Z.; Braga, M.H.; Daemen, L.L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y. High pressure-high temperature synthesis of lithium-rich Li3O(Cl, Br) and Li3−xCax/2OCl anti-perovskite halides. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2014, 48, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumar, M.K.; Yamamoto, T.; Motoyama, M.; Iriyama, Y. Room temperature synthesis of anti-perovskite structured Li2OHBr. Solid State Ion. 2020, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, L.L.; Zawadzki, P.; Lany, S.; Toberer, E.S.; Zakutayev, A. A review of defects and disorder in multinary tetrahedrally bonded semiconductors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 123004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloaro, M.; Liedke, M.O.; Angervo, I.; Butterling, M.; Hirschmann, E.; Wagner, A.; Huhtinen, H.; Paturi, P. Exploring the anti-site disorder and oxygen vacancies in Sr2FeMoO6 thin films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Barbadillo, C.; González, J.F.; Porcheddu, A.; Virieux, D.; Menéndez, J.C.; Colacino, E. Benign synthesis of therapeutic agents: domino synthesis of unsymmetrical 1,4-diaryl-1,4-dihydropyridines in the ball-mill. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2022, 15, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schittny, A.; Huwyler, J.; Puchkov, M. Mechanisms of increased bioavailability through amorphous solid dispersions: a review. Drug Deliv 2020, 27, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe T, W.N. , Usui F, Ikeda M, Isobe T, Senna M. Stability of amorphous indomethacin compounded with silica. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 226, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe T, O.I. , Wakiyama N, Kusai A, Senna M. Stabilization of amorphous indomethacin by co-grinding in a ternary mixture. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 241, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T. , Wakiyama, N., Kusai, A., Senna, M. Drug-Carrier Interaction in Solid Dispersions Prepared by Co-grinding and Melt-quenching. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mater. 2004, 29, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, A.S.; Desai, D.; Badawy, S. Impact of excipient interactions on solid dosage form stability. Pharm Res 2012, 29, 2660–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, T.M.; Quadir, A.; Obara, S.; Hoag, S.W. Impact of formulation excipients on the thermal, mechanical, and electrokinetic properties of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate (HPMCAS). Int J Pharm 2018, 542, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, R.; Lobmann, K.; Grohganz, H.; Strachan, C.; Rades, T. Amino acids as co-amorphous excipients for simvastatin and glibenclamide: physical properties and stability. Mol Pharm 2014, 11, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Wakiyama, N.; Kusai, A.; Senna, M. A molecular orbital study on the chemical interaction across the indomethacin/silica interparticle boundary due to mechanical stressing. Powder Technol. 2004, 141, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Wakiyama, N.; Usui, F.; Kusai, A.; Isobe, T.; Senna, M. Solid State Radical Recombination and Charge Transfer across the Boundary between Indomethacin and Silica under Mechanical Stress. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 164, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Yamanouchi, H. Ball-impact energy analysis of wet tumbling mill using a modified discrete element method considering the velocity dependence of friction coefficient. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 163, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo, B.C.; Valenzuela, M.A. Experimental Evaluation of Power Requirements for Wet Grinding and Its Comparison to Dry Grinding. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 3953–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Worku, Z.A.; Gao, Y.; Kamaraju, V.K.; Glennon, B.; Babu, R.P.; Healy, A.M. Comparison of wet milling and dry milling routes for ibuprofen pharmaceutical crystals and their impact on pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical properties. Powder Technol. 2018, 330, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Matsuzaka, Y.; Kimura, M.; Matsuki, H.; Yanagisawa, Y. Comparison of dry- and wet-based fine bead homogenizations to extract DNA from fungal spores. J Biosci Bioeng 2009, 107, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friscic T, T.A. , Jones W, Motherwell WDS. Guest-Directed Assembly of Caffeine and Succinic Acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7546–7550. [Google Scholar]

- Friscic, T.; Trask, A.V.; Jones, W.; Motherwell, W.D. Screening for inclusion compounds and systematic construction of three-component solids by liquid-assisted grinding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2006, 45, 7546–7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, P.P.; Prencipe, M.; Feiler, T.; Emmerling, F.; Bacchi, A. On the Mechanism of Cocrystal Mechanochemical Reaction via Low Melting Eutectic: A Time-Resolved In Situ Monitoring Investigation. Cryst Growth Des 2022, 22, 4260–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, R.; Watanabe, H.; Senna, M. A solvent-free organic synthesis from solid-state reactants through autogenous fusion due to formation of molecular complexes and increasing alcohol nucleophilicity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3111–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialek, K.; Wojnarowska, Z.; Skotnicki, M.; Twamley, B.; Paluch, M.; Tajber, L. Submerged Eutectic-Assisted, Solvent-Free Mechanochemical Formation of a Propranolol Salt and Its Other Multicomponent Solids. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balema, V.P.; Wiench, J.W.; Pruski, M.; Pecharsky, V.K. Solvent-free mechanochemical synthesis of phosphonium salts. Chem Commun (Camb), 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolotko, O.; Wiench, J.W.; Dennis, K.W.; Pecharsky, V.K.; Balema, V.P. Mechanically induced reactions in organic solids: liquid eutectics or solid-state processes? New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, R.; Senna, M. Rational chemical reactions from solid-states by autogenous fusion of quinone–phenol systems via charge transfer complex. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2009, 87, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanje, B.; Bottke, P.; Breuer, S.; Hanzu, I.; Heitjans, P.; Wilkening, M. Ion dynamics in a new class of materials: nanoglassy lithium alumosilicates. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadio, A.; Escanhoela, C.A.; Sabino, F.P.; Sombrio, G.; de Paula, V.G.; Ferreira, F.F.; Janotti, A.; Dalpian, G.M.; Souza, J.A. Entropy-driven stabilization of the cubic phase of MaPbI3 at room temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.H.; Liu, G.Y.; Feng, X.M.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, J.K. Entropy contribution to the stability of double perovskite Sr2FexMo2−xO6. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2005, 6, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.R.; Knecht, M.R. Biointerface Structural Effects on the Properties and Applications of Bioinspired Peptide-Based Nanomaterials. Chem Rev 2017, 117, 12641–12704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose in biomedicine: Current status and future prospect. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 59, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, P.; Tan, A.; Whitby, C.P.; Prestidge, C.A. The role of porous nanostructure in controlling lipase-mediated digestion of lipid loaded into silica particles. Langmuir 2014, 30, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokarev, A.N.; Plastun, I.L. Possibility of drug delivery due to hydrogen bonds formation in nanodiamonds and doxorubicin: molecular modeling. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2018, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, E.; Piccini, G.; Lercher, J.A.; Glezakou, V.A.; Rousseau, R.; Parrinello, M. Confinement effects and acid strength in zeolites. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).