Submitted:

21 June 2023

Posted:

22 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

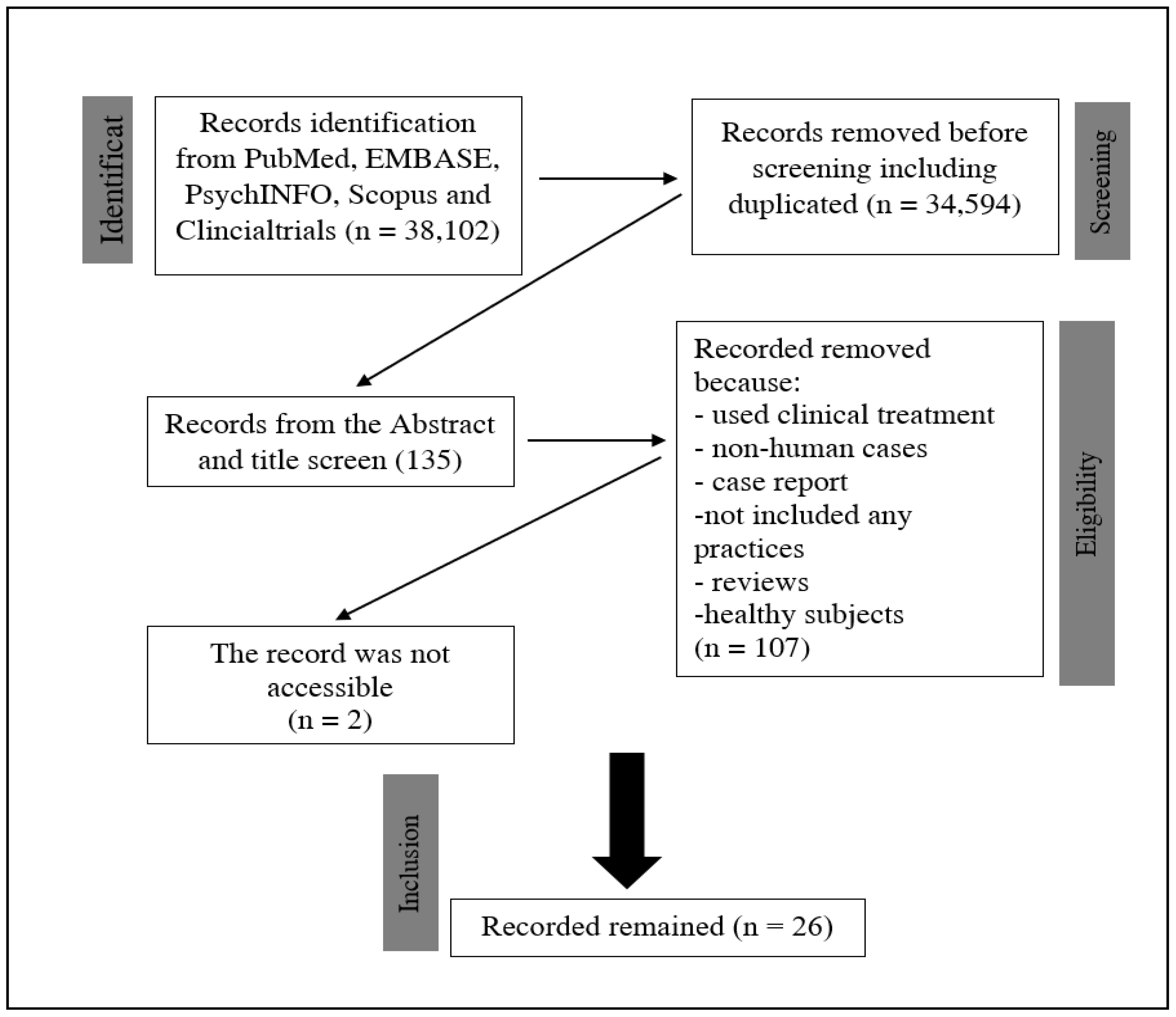

2. Method

3. Results

| # | Ref | Y | number of patients | subject description | Technique | Parameters | Environment | Outcome/s |

| 1 | [64] | 2003 | 5 patients | chronic stroke patients | computer-based design | not mentioned | static and kinetic perimetry improvement | |

| 2 | [2] | 2005 | 8 patients | PT's with chronic visual field defects participated in the study | sensory stimulations were used | three stimuli were presented: unimodal visual, unimodal auditory, and crossmodally visuo-auditory.presenting a visual target in different spatial positions within 120 trials and some targets without visual stimulihemianopia hemifield was more intensively stimulated than the intact hemifield | Laboratory setting | the difference between the baseline and each training session was significantSignificant post-hoc comparisons were reported |

| 3 | [65] | 2008 | 19 patients | subjects with damage to the retina or optic nerve disorders | VRT | not mentioned | visual field size is increased; also some cognitive factors were improvedvisual field size increased, | |

| 4 | [45] | 2008 | 12 patients | hemianopia with more than 2 months after diagnosis or incident | visual and auditory stimulation, unimodal auditory condition, unimodal visual catch-trial, and cross-modal condition | Laboratory setting | decrease localization error, improvement in the blind field was better than intact hemifield, | |

| 5 | [66] | 2009 | 12 patients and 12 control subjects | patients with chronic visual field deficits due to a postchiasmatic lesion | Control Visual Training and, subsequently, Audio-Visual Training. | Audio-Visual Training comprised systematic audio-visual stimulation of the intact and affected visual fields for 4 h daily over 2 weeks | Laboratory setting | Visual detection and perceptual sensitivity significantly increased in one of the cases compared to the other.The accuracy significantly improved in the triangle test between subjects. Compared to S1, the daily life activities were significantly reduced. A significant reduction in the length of the scan bathimprovement in ocular exploration characterized by fewer fixations and refixations, quicker and larger saccades, and reduced scan path lengthReading was improved |

| 6 | [67] | 2009 | 8 as the main and 12 control group | All patients had complete or nearly complete hemianopia | eye movement training and physical and occupational therapies | two daily training sessions of 30 min each for a total of 4 weeksAll patients also received 90 min daily of complementary physical and occupational therapy to facilitate the transfer of compensatory visual strategies into ADL functions | clinical-lab settings | stable visual field defectNo differences in the size of visual field defects were found after the training. |

| 7 | [68] | 2010 | 20 patients | patients with either left- or right-sided visualfield deficits | audio-visual exploration training | visual and acousticstimuli, 48 red light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and piezoelectricloudspeakers were positioned in 3 rows at different angles, and the same apparatus for visual exploration training | in a dimly illuminated room | significant improvements after audio-visual training for the number of detected targets in the visual exploration test, reading time, search time, amplitude and number of saccades in the EOG, and total score on the questionnaire of activities of daily living.the detection rate of target stimuli improved by about 46% in patients |

| 8 | [69] | 2010 | 20 patients | left or right visual field deficits after a stroke | Patients were randomly assigned to separate groups performing either audio-visual or visual stimulation training (20 sessions, each lasting 30 minutes). | lab settings / clinical environment | compensatory eye movement training, greater improvement for all outcome variables for the audio-visual group | |

| 9 | [70] | 2012 | 13 patients | patients with hemianopia | NVT vision rehabilitation over a 3-month intervention | laboratory setting | Target improvements were missing improvement in their quality of life, but the visual field was not improved significantly. | |

| 10 | [71] | 2012 | 10 patients | chronically 5 months after the first stroke | audio-visual training | controlled environment | increasing visual detection, increasing hemifield in visual detection | |

| 11 | [72] | 2013 | 10 patients and 10 control | chronically 6 months after lesion or diagnosis | audio-visual stimuli, including acoustic stimuli with visual target | controlled environment | visual space is compressed on the intact side compared to the anopic side | |

| 12 | [73] | 2015 | 14 patients | homonymous hemianopia | a fixed-base driving simulator by testing RT and speed while detecting a hazardous parameter | lab with simulator | The low-performance group missed more hazardous objects than the high-performance group, but there were no changes in the HP and control groups. Reaction times in the blind hemifield (patients) and right hemifield (healthy controls) differed significantly between the groups. Healthy controls reacted significantly faster in the right hemifield than either the HP. | |

| 13 | [73] | 2015 | 33 patients | reading text application | using a reading text application in different settings to evaluate their reading and improve it | Home-based training | reading right showed improvement in time. Improvement in the visual field of patients over time.no significant change in right hemifield vision | |

| 14 | [74] | 2015 | 8 patients | at least 26 months after the lesion | unimodal auditory, bimodal coincident spatially and temporally, bimodal disparate | lab settings | saccade improvement in patients in the intact field, | |

| 15 | [75] | 2015 | 8 patients | hemianopia with minimum 3 months after the lesion | visual and multisensory training | controlled environment | daily improvement of attentional allocation and visual exploration in the blind field improves the quality of life scale. | |

| 16 | [76] | 2015 | 3 patients | chronically 1 or more than one year after the lesion | unimodal visual, unimodal auditory, cross-modal audio-visual training | controlled environment | ||

| 17 | [77] | 2016 | 32 patients | either left or right homonymous hemianopia | NeuroEyeCoach™ | lab settings | improvement of time (RT) for cancellation task, decreased time in visual search, positive outcome in scanning | |

| 18 | 2016 | 24 patients | either left or right homonymous hemianopia | Home-based training | ||||

| 19 | [78] | 2016 | 10 patients | more than 3 months after diagnosis or lesion | unisensory training, multi-Audio-visual sensory training, unisensory Audio training | controlled environment | visual search improvement in audio-visual search, improving fixation and oculomotor performance, increased accuracy | |

| 20 | [79] | 2017 | 3 patients | the first subject after 3 months of stroke, the second subject was with HH on the right side, the third subject with partial left HH | visual and acoustic stimuli, audio-visual stimulation | a plastic arch-shaped device fixed horizontally on the table surface, two horizontal rows of visual stimuli (LEDs) for a total length of 192 cm, height of 32 cm, and thickness of 1.2 cm in which the instrument covered 180 Degrees as the entire visual field. Training includes 12 visual stimuli (24 LEDs) with a diameter of 0.5 and 12 acoustic stimuli | Laboratory setting | significant improvement in visual detection rates in the affected hemifield in both the Fixed-Eyes Condition, improved eye-movement pre and post-conditional, and improved visual detection in hemifield. The percentage of responses to audio-visual stimuli in the hemianopia hemifield improved |

| 21 | [80] | 2017 | 87 patients | stable hemianopia patients | Fresnel prisms, 30—visual search training, and 30—standard care | not mentioned | change in visual field area; improving reading abilities in both speed and accuracy;Visual function improved at 26 weeks in the visual search training arm compared to other interventions. | |

| 22 | [81] | 2018 | 22 patients – Kids | different reasons such as perinatal ischemia, tumor, stroke, hemispherectomy, hemiatrophy | computer-based visual search training (VST) for children | trained at home for 15 minutes twice/day, 5 days/week, for 6 weeks. | Home-based training | search times (STs) decreased significantly during the training and all search performance tests. This improvement persisted 6 weeks after the end of the training. Saccade amplitudes increased, the total number of saccades to find the target decreased, and the proportional number of saccades to the non-seeing side increased. During free viewing, saccades were equally distributed to both sides before and after training |

| 23 | [82] | 2018 | 24 patients | adult stroke patients | efficacy open-label investigation using vision therapies techniques | one lesson a week for 12 weeks carried out by an optometrist and a vision therapist. Between lessons, patients were to train at home for a minimum of 15-20 min daily. | Laboratory setting | Significant improvements in visual performance were measured for all test parameters from the baseline to the evaluation after the last lesson of vision training. Tracing test results improved, reading speed in words increased, peripheral awareness of visual markers improved |

| 24 | [83] | 2018 | 1 patient | visual area seizure | Visual neurorehabilitation therapy (NRT) | administered for 3 hours each week | Laboratory setting | ocular movements improved, visual search became more organized, the reading reached a level without mistakes, with rhythm and goog intonation |

| 25 | [84] | 2018 | 10 patients | Trained in detecting low contrast Gabor patches randomly presented in the blind field, which refers to regions of 0 dB sensitivity, and along the hemianopia boundary between absolute (0 dB) and partial blindness (>0 dB) | Laboratory setting | NRT led to significant visual field enlargement (≈5 deg), and the restored area acquired new visual functions such as small letter recognition and perception of moving shapes; for some patients, NRT also improved detection, either aware or not, of high contrast flickering grating and recognition of geometrical shapes entirely presented within the blind field. | ||

| 26 | [85] | 2019 | 14 patients | patient with a history of stroke | computer-based cognitive rehabilitation (CBCR) | visuospatial neglect or homonymous hemianopia in the subacute phase of the following stroke | Hospital- no natural ecology | CBCR improved visuospatial symptoms after a stroke |

3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- F. Criado-Boado et al., “Coevolution of visual behaviour, the material world and social complexity, depicted by the eye-tracking of archaeological objects in humans,” Sci. Rep., vol. 9, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “Hemianopia, spatial neglect, and their multisensory rehabilitation - ScienceDirect”. 17 May. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012812492500019X?via%3Dihub (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- S. Kedar, “Pediatric homonymous hemianopia.,” J. AAPOS Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus, 2006.

- X. Zhang, S. Kedar, M. J. Lynn, N. J. Newman, and V. Biousse, “Natural history of homonymous hemianopia,” Neurology, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 901–905, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. X. Zhang, S. Kedar, M. J. Lynn, N. J. Newman, and V. Biousse, “Natural history of homonymous hemianopia,” Neurology, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 901–905, Mar. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. B. Welch and D. H. Warren, “Immediate perceptual response to intersensory discrepancy.,” Psychol. Bull., vol. 88, no. 3, p. 638, 1980.

- M. O. Ernst and H. H. Bülthoff, “Merging the senses into a robust percept,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 162–169, 2004.

- L. M. Pambakian and C. Kennard, “Can visual function be restored in patients with homonymous hemianopia?,” Br. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 81, no. 4, pp. 324–328, Apr. 1997. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Sabel and E. Kasten, “Restoration of vision by training of residual functions,” Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol., vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 430–436, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Posner, M. J. Nissen, and R. M. Klein, “Visual dominance: an information-processing account of its origins and significance.,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 83, no. 2, p. 157, 1976.

- M. Mather and M. R. Sutherland, “Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory,” Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 114–133, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Gupta, A. C. Ireland, and B. Bordoni, “Neuroanatomy, Visual Pathway,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2023. Accessed: Jun. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553189/.

- J. B. Jonas, R. A. Jonas, M. M. Bikbov, Y. X. Wang, and S. Panda-Jonas, “Myopia: Histology, clinical features, and potential implications for the etiology of axial elongation,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res., p. 101156, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Harb, “Hyperopia☆,” in Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology, Elsevier, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Al-khersan, H. W. Flynn, and J. H. Townsend, “Retinal Detachments Associated With Topical Pilocarpine Use for Presbyopia,” Am. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 242, pp. 52–55, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. F. Tan et al., “Colour vision restrictions for driving: an evidence-based perspective on regulations in ASEAN countries compared to other countries,” Lancet Reg. Health - Southeast Asia, p. 100171, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. W. Svaerke, K. V. Omkvist, I. B. Havsteen, and H. K. Christensen, “Computer-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation in Patients with Visuospatial Neglect or Homonymous Hemianopia after Stroke,” J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc., vol. 28, no. 11, p. 104356, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. A. de Haan, J. Heutink, B. J. M. Melis-Dankers, O. Tucha, and W. H. Brouwer, “Spontaneous recovery and treatment effects in patients with homonymous visual field defects: a meta-analysis of existing literature in terms of the ICF framework,” Surv. Ophthalmol., vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 77–96, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Chen et al., “Vision-related quality of life in patients with complete homonymous hemianopia post stroke,” Top. Stroke Rehabil., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 445–453, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Berthold-Lindstedt, J. Johansson, J. Ygge, and K. Borg, “How to assess visual function in acquired brain injury—Asking is not enough,” Brain Behav., vol. 11, no. 2, p. e01958, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. de Munter, S. Polinder, R. J. M. Havermans, E. W. Steyerberg, and M. A. C. de Jongh, “Original research: Prognostic factors for recovery of health status after injury: a prospective multicentre cohort study,” BMJ Open, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Perez and S. Chokron, “Rehabilitation of homonymous hemianopia: insight into blindsight,” Front. Integr. Neurosci., vol. 8, p. 82, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Sahraie, C. T. Trevethan, M. J. MacLeod, A. D. Murray, J. A. Olson, and L. Weiskrantz, “Increased sensitivity after repeated stimulation of residual spatial channels in blindsight,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 103, no. 40, pp. 14971–14976, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Huxlin, “Perceptual plasticity in damaged adult visual systems,” Vision Res., vol. 48, no. 20, pp. 2154–2166, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Ajina, K. Jünemann, A. Sahraie, and H. Bridge, “Increased Visual Sensitivity and Occipital Activity in Patients With Hemianopia Following Vision Rehabilitation,” J. Neurosci., vol. 41, no. 28, pp. 5994–6005, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Cavanaugh and K. R. Huxlin, “Visual discrimination training improves Humphrey perimetry in chronic cortically induced blindness,” Neurology, vol. 88, no. 19, pp. 1856–1864, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Wright, A. T. Sabin, Y. Zhang, N. Marrone, and M. B. Fitzgerald, “Enhancing Perceptual Learning by Combining Practice with Periods of Additional Sensory Stimulation,” J. Neurosci., vol. 30, no. 38, pp. 12868–12877, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Trauzettel-Klosinski, “Current Methods of Visual Rehabilitation,” Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int., vol. 108, no. 51–52, p. 871, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Giorgi, “Clinical and Laboratory Evaluation of Peripheral Prism Glasses for Hemianopia,” Optom. Vis. Sci., 2009.

- M. Pikhart, B. Klimova, A. Cierniak-Emerych, and S. Dziuba, “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Through Intervention by Second Language Acquisition in Older Adults,” J. Psycholinguist. Res., vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 1181–1196, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gopi, E. Wilding, and C. R. Madan, “Memory rehabilitation: restorative, specific knowledge acquisition, compensatory, and holistic approaches,” Cogn. Process., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 537–557, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. W. Park and J. L. Ingles, “Effectiveness of attention rehabilitation after an acquired brain injury: A meta-analysis,” Neuropsychology, vol. 15, pp. 199–210, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosa, M. F. Silva, S. Ferreira, J. Murta, and M. Castelo-Branco, “Plasticity in the Human Visual Cortex: An Ophthalmology-Based Perspective. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 568354. [CrossRef]

- G. Kerkhoff, “Restorative and compensatory therapy approaches in cerebral blindness - a review,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 15, no. 2–3, pp. 255–271, 1999.

- D. A. Poggel, I. Mueller, E. Kasten, and B. A. Sabel, “Multifactorial predictors and outcome variables of vision restoration training in patients with post-geniculate visual field loss,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 26, no. 4–5, pp. 321–339, Jan. 2008.

- M. Scheiman et al., “A randomized clinical trial of vision therapy/orthoptics versus pencil pushups for the treatment of convergence insufficiency in young adults,” Optom. Vis. Sci., vol. 82, no. 7, pp. 583–593, 2005. [CrossRef]

- C. Jicol et al., “Efficiency of Sensory Substitution Devices Alone and in Combination With Self-Motion for Spatial Navigation in Sighted and Visually Impaired,” Front. Psychol., vol. 11, 2020, Accessed: Jun. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01443.

- R. M. van Nispen et al., “Low vision rehabilitation for better quality of life in visually impaired adults,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., vol. 2020, no. 1, p. CD006543, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Norton, R. K. McBain, D. Ongur, and Y. Chen, “Perceptual training strongly improves visual motion perception in schizophrenia,” Brain Cogn., vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 248–256, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Kerkhoff, U. Münßinger, E. Haaf, G. Eberle-Strauss, and E. Stögerer, “Rehabilitation of homonymous scotomata in patients with postgeniculate damage of the visual system: saccadic compensation training,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 245–254, Jan. 1992. [CrossRef]

- S. Trauzettel-Klosinski, “[Rehabilitation of lesions in the visual pathways],” Klin. Monatsbl. Augenheilkd., vol. 226, no. 11, pp. 897–907, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Trauzettel-Klosinski, “Rehabilitative techniques,” Handb. Clin. Neurol., vol. 102, pp. 263–278, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Julkunen, O. Tenovuo, S. Jääskeläinen, and H. Hämäläinen, “Rehabilitation of chronic post-stroke visual field defect with computer-assisted training: a clinical and neurophysiological study,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 21, no. 1–2, pp. 19–28, 2003.

- N. Bolognini, F. Rasi, M. Coccia, and E. Làdavas, “Visual search improvement in hemianopic patients after audio-visual stimulation,” Brain, vol. 128, no. 12, pp. 2830–2842, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- F. Leo, N. Bolognini, C. Passamonti, B. E. Stein, and E. Làdavas, “Cross-modal localization in hemianopia: new insights on multisensory integration,” Brain, vol. 131, no. 3, pp. 855–865, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Passamonti, C. Bertini, and E. Làdavas, “Audio-visual stimulation improves oculomotor patterns in patients with hemianopia,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 546–555, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- G. Nelles et al., “Eye-movement training-induced plasticity in patients with post-stroke hemianopia,” J. Neurol., vol. 256, no. 5, pp. 726–733, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- I. Keller and G. Lefin-Rank, “Improvement of visual search after audiovisual exploration training in hemianopic patients,” Neurorehabil. Neural Repair, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 666–673, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Hayes, C. S. Chen, G. Clarke, and A. Thompson, “Functional improvements following the use of the NVT Vision Rehabilitation program for patients with hemianopia following stroke,” NeuroRehabilitation, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 19–30, 2012,. [CrossRef]

- J. Lewald, M. Tegenthoff, S. Peters, and M. Hausmann, “Passive Auditory Stimulation Improves Vision in Hemianopia,” PLOS ONE, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e31603, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Bahnemann et al., “Compensatory eye and head movements of patients with homonymous hemianopia in the naturalistic setting of a driving simulation,” J. Neurol., vol. 262, no. 2, pp. 316–325, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Brink, T. C. W. Nijboer, D. P. Bergsma, J. J. S. Barton, and S. V. der Stigchel, “Lack of Multisensory Integration in Hemianopia: No Influence of Visual Stimuli on Aurally Guided Saccades to the Blind Hemifield,” PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e0122054, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Dundon, E. Làdavas, M. E. Maier, and C. Bertini, “Multisensory stimulation in hemianopic patients boosts orienting responses to the hemianopic field and reduces attentional resources to the intact field,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 405–419, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Tinelli, G. Purpura, and G. Cioni, “Audio-Visual Stimulation Improves Visual Search Abilities in Hemianopia due to Childhood Acquired Brain Lesions,” Multisensory Res., vol. 28, no. 1–2, pp. 153–171, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Sahraie, N. Smania, and J. Zihl, “Use of NeuroEyeCoachTM to Improve Eye Movement Efficacy in Patients with Homonymous Visual Field Loss,” BioMed Res. Int., vol. 2016, p. e5186461, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Grasso, E. Làdavas, and C. Bertini, “Compensatory Recovery after Multisensory Stimulation in Hemianopic Patients: Behavioral and Neurophysiological Components,” Front. Syst. Neurosci., vol. 10, p. 45, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Tinelli, G. Cioni, and G. Purpura, “Development and Implementation of a New Telerehabilitation System for Audiovisual Stimulation Training in Hemianopia,” Front. Neurol., vol. 8, 2017, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00621.

- F. J. Rowe et al., “A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing effectiveness of prism glasses, visual search training and standard care in hemianopia,” Acta Neurol. Scand., vol. 136, no. 4, pp. 310–321, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Ivanov et al., “Effects of visual search training in children with hemianopia,” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 7, p. e0197285, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Smaakjær, S. T. Tødten, and R. S. Rasmussen, “Therapist-assisted vision therapy improves outcome for stroke patients with homonymous hemianopia alone or combined with oculomotor dysfunction,” Neurol. Res., vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 752–757, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Pineda-Ortíz, G. Pacheco-López, M. Rubio-Osornio, C. Rubio, and J. Valadez-Rodríguez, “Neurorehabilitation of saccadic ocular movement in a patient with a homonymous hemianopia postgeniculate caused by an arteriovenous malformation,” Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 97, no. 11, p. e9890, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Casco, M. Barollo, G. Contemori, and L. Battaglini, “Neural Restoration Training improves visual functions and expands visual field of patients with homonymous visual field defects,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 275–291, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Svaerke, K. V. Omkvist, I. B. Havsteen, and H. K. Christensen, “Computer-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation in Patients with Visuospatial Neglect or Homonymous Hemianopia after Stroke,” J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis., vol. 28, no. 11, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Julkunen, O. Tenovuo, S. Jääskeläinen, and H. Hämäläinen, “Rehabilitation of chronic post-stroke visual field defect with computer-assisted training,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 21, no. 1–2, pp. 19–28, Jan. 2003.

- D. A. Poggel, E. M. Mueller-Oehring, E. Kasten, U. Bunzenthal, and B. A. Sabel, “The topography of training-induced visual field recovery: Perimetric maps and subjective representations,” Vis. Cogn., vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 1059–1077, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Passamonti, I. Frissen, and E. Làdavas, “Visual recalibration of auditory spatial perception: two separate neural circuits for perceptual learning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 1141–1150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Nelles et al., “Eye-movement training-induced plasticity in patients with post-stroke hemianopia,” J. Neurol., vol. 256, no. 5, pp. 726–733, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- I. Keller and G. Lefin-Rank, “Improvement of Visual Search After Audiovisual Exploration Training in Hemianopic Patients,” Neurorehabil. Neural Repair, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 666–673, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- I. Keller and G. Lefin-Rank, “Repair,” 2010.

- M. Crotty, M. van den Berg, A. Hayes, C. Chen, K. Lange, and S. George, “Hemianopia after stroke: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a standardised versus an individualized rehabilitation program, on scanning ability whilst walking1,” NeuroRehabilitation, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 201–209, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Lewald, M. Tegenthoff, S. Peters, and M. Hausmann, “Passive Auditory Stimulation Improves Vision in Hemianopia,” PLOS ONE, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e31603, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Lewald, R. W. Kentridge, S. Peters, M. Tegenthoff, C. A. Heywood, and M. Hausmann, “Auditory-visual localization in hemianopia.,” Neuropsychology, vol. 27, no. 5, p. 573, 2013.

- M. Bahnemann et al., “Compensatory eye and head movements of patients with homonymous hemianopia in the naturalistic setting of a driving simulation,” J. Neurol., vol. 262, no. 2, pp. 316–325, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Brink, T. C. W. Nijboer, D. P. Bergsma, J. J. S. Barton, and S. V. der Stigchel, “Lack of Multisensory Integration in Hemianopia: No Influence of Visual Stimuli on Aurally Guided Saccades to the Blind Hemifield,” PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e0122054, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Dundon, E. Làdavas, M. E. Maier, and C. Bertini, “Multisensory stimulation in hemianopic patients boosts orienting responses to the hemianopic field and reduces attentional resources to the intact field,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 405–419, 2015. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Tinelli, G. Purpura, and G. Cioni, “Audio-Visual Stimulation Improves Visual Search Abilities in Hemianopia due to Childhood Acquired Brain Lesions,” Multisensory Res., vol. 28, no. 1–2, pp. 153–171, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sahraie, N. Smania, and J. Zihl, “Use of NeuroEyeCoachTM to Improve Eye Movement Efficacy in Patients with Homonymous Visual Field Loss. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5186461. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Grasso, E. Làdavas, and C. Bertini, “Compensatory Recovery after Multisensory Stimulation in Hemianopic Patients: Behavioral and Neurophysiological Components,” Front. Syst. Neurosci., vol. 10, 2016, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00045.

- F. Tinelli, G. Cioni, and G. Purpura, “Development and Implementation of a New Telerehabilitation System for Audiovisual Stimulation Training in Hemianopia,” Front. Neurol., vol. 8, 2017, Accessed: May 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00621. 24 May.

- F. J. Rowe et al., “A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing effectiveness of prism glasses, visual search training and standard care in hemianopia,” Acta Neurol. Scand., vol. 136, no. 4, pp. 310–321, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Ivanov et al., “Effects of visual search training in children with hemianopia. PloS One 2018, 13, e0197285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Smaakjær, S. T. Tødten, and R. S. Rasmussen, “Therapist-assisted vision therapy improves outcome for stroke patients with homonymous hemianopia alone or combined with oculomotor dysfunction,” Neurol. Res., vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 752–757, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Pineda-Ortíz, G. Pacheco-López, M. Rubio-Osornio, C. Rubio, and J. Valadez-Rodríguez, “Neurorehabilitation of saccadic ocular movement in a patient with a homonymous hemianopia postgeniculate caused by an arteriovenous malformation: A Case Report,” Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 97, no. 11, p. e9890, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Casco, M. Barollo, G. Contemori, and L. Battaglini, “Neural Restoration Training improves visual functions and expands visual field of patients with homonymous visual field defects,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci., vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 275–291, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Svaerke, K. V. Omkvist, I. B. Havsteen, and H. K. Christensen, “Computer-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation in Patients with Visuospatial Neglect or Homonymous Hemianopia after Stroke,” J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis., vol. 28, no. 11, p. 104356, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Hamel, A. Kraft, S. Ohl, S. De Beukelaer, H. J. Audebert, and S. A. Brandt, “Driving Simulation in the Clinic: Testing Visual Exploratory Behavior in Daily Life Activities in Patients with Visual Field Defects,” J. Vis. Exp. JoVE, no. 67, p. 4427, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Lanyon and J. J. S. Barton, “Visual Search and Line Bisection in Hemianopia: Computational Modelling of Cortical Compensatory Mechanisms and Comparison with Hemineglect,” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 2, p. e54919, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Schuett, R. W. Kentridge, J. Zihl, and C. A. Heywood, “Are hemianopic reading and visual exploration impairments visually elicited? New insights from eye movements in simulated hemianopia,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 733–746, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Pambakian, D. S. Wooding, N. Patel, A. B. Morland, C. Kennard, and S. K. Mannan, “Scanning the visual world: a study of patients with homonymous hemianopia,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 751–759, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- E. L. SAIONZ, A. BUSZA, and K. R. HUXLIN, “Rehabilitation of visual perception in cortical blindness,” Handb. Clin. Neurol., vol. 184, pp. 357–373, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Bocanegra and R. Zeelenberg, “Dissociating emotion-induced blindness and hypervision,” Emot. Wash. DC, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 865–873, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Wood et al., “Hemianopic and Quadrantanopic Field Loss, Eye and Head Movements, and Driving,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 1220–1225, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Roth, A. N. Sokolov, A. Messias, P. Roth, M. Weller, and S. Trauzettel-Klosinski, “Comparing explorative saccade and flicker training in hemianopia: A randomized controlled study,” Neurology, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 324–331, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Bock and I. Fine, “Anatomical and functional plasticity in early blind individuals and the mixture of experts architecture,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., vol. 8, p. 971, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Kwon, B. K. Fahrenthold, M. R. Cavanaugh, K. R. Huxlin, and J. F. Mitchell, “Perceptual restoration fails to recover unconscious processing for smooth eye movements after occipital stroke,” eLife, vol. 11, p. e67573, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Huxlin and T. Pasternak, “Training-induced Recovery of Visual Motion Perception after Extrastriate Cortical Damage in the Adult Cat,” Cereb. Cortex, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 81–90, 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Huxlin, J. M. Williams, and T. Price, “A neurochemical signature of visual recovery after extrastriate cortical damage in the adult cat,” J. Comp. Neurol., vol. 508, no. 1, pp. 45–61, 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. Huxlin et al., “Perceptual Relearning of Complex Visual Motion after V1 Damage in Humans,” J. Neurosci., vol. 29, no. 13, pp. 3981–3991, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Barbot et al., “Changes in perilesional V1 underlie training-induced recovery in cortically-blind patients.” bioRxiv, p. 2020.02.28.970285, Mar. 21, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Das and K. R. Huxlin, “New approaches to visual rehabilitation for cortical blindness: outcomes and putative mechanisms,” Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 374–387, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).