Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results & Discussion

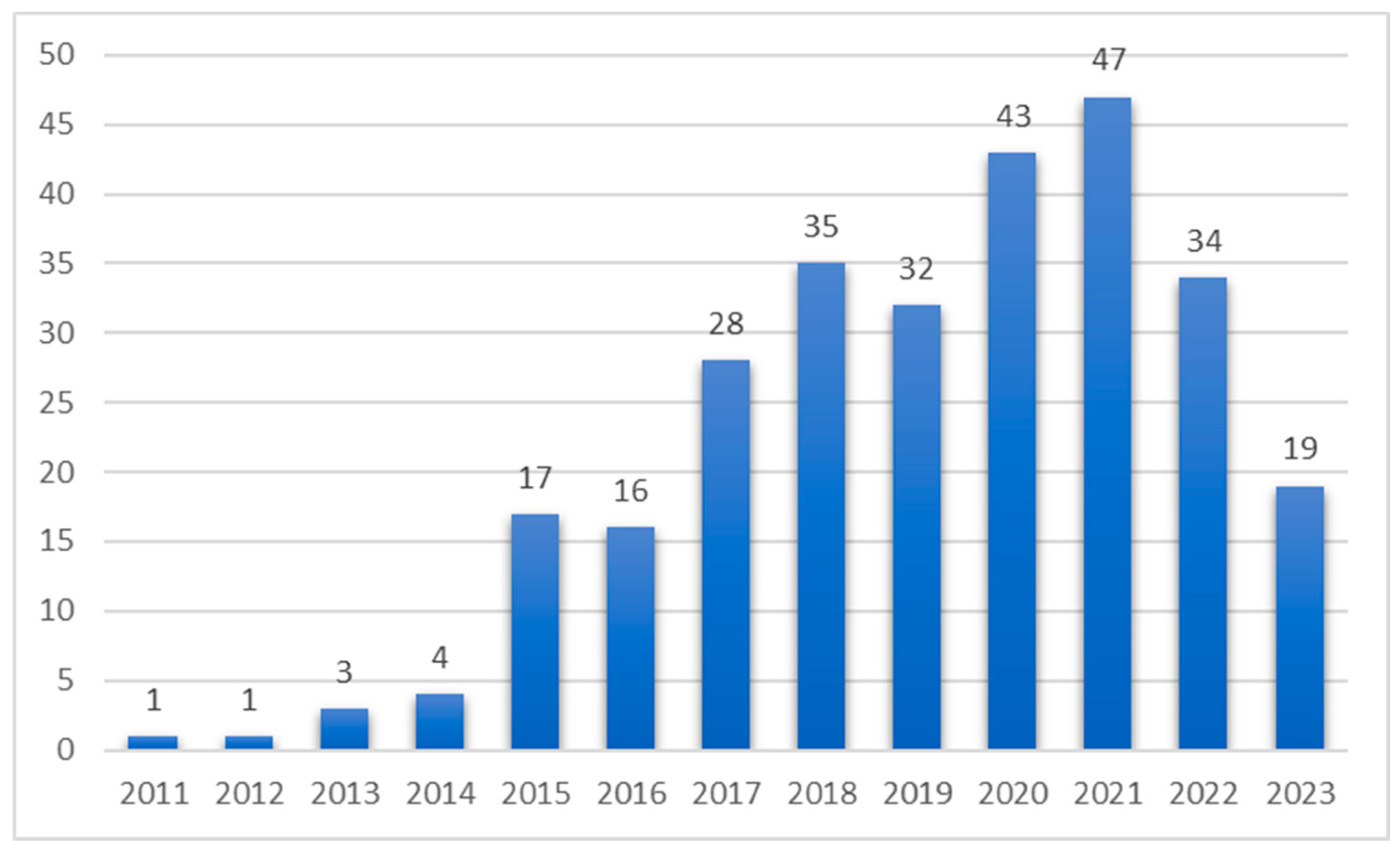

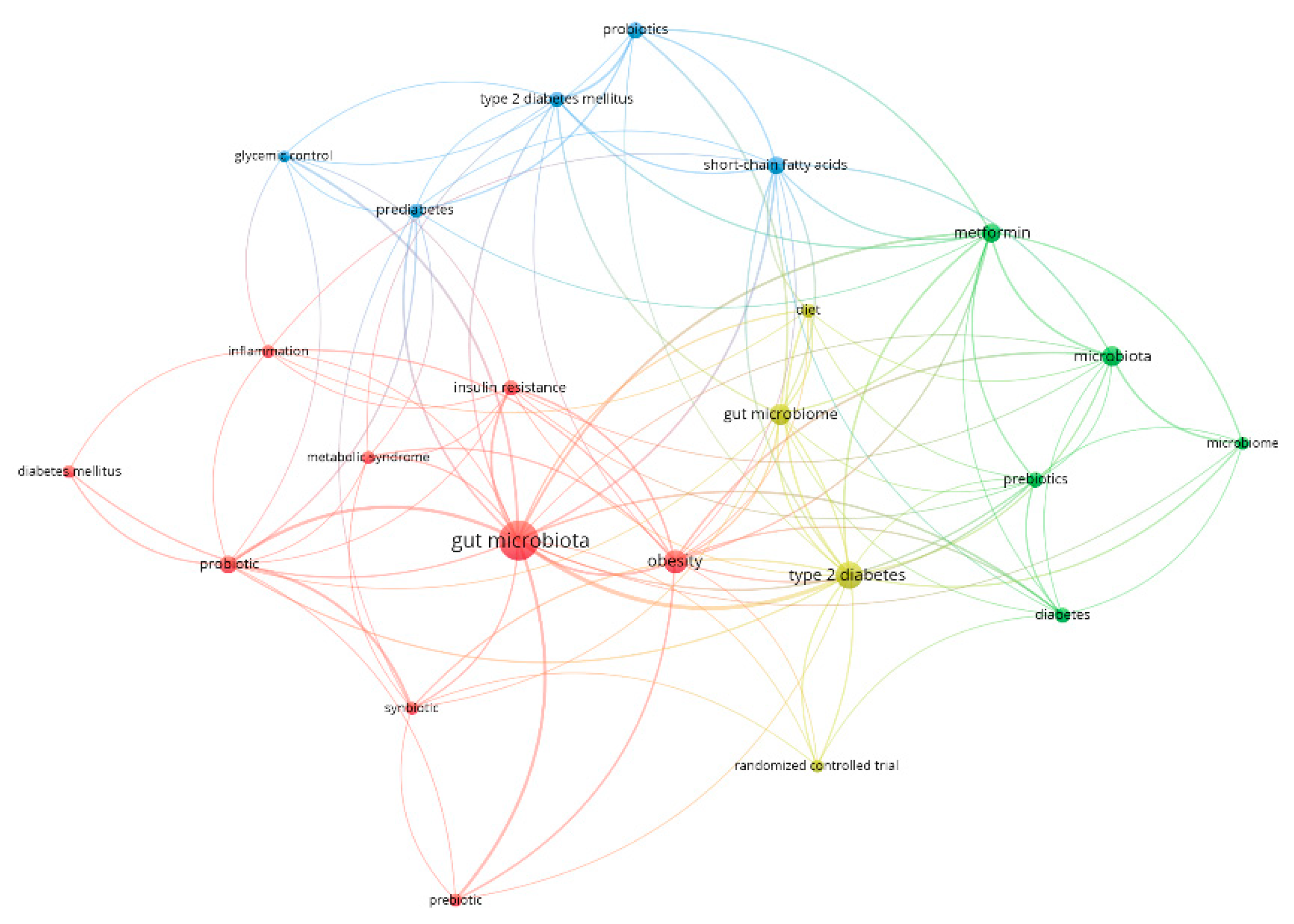

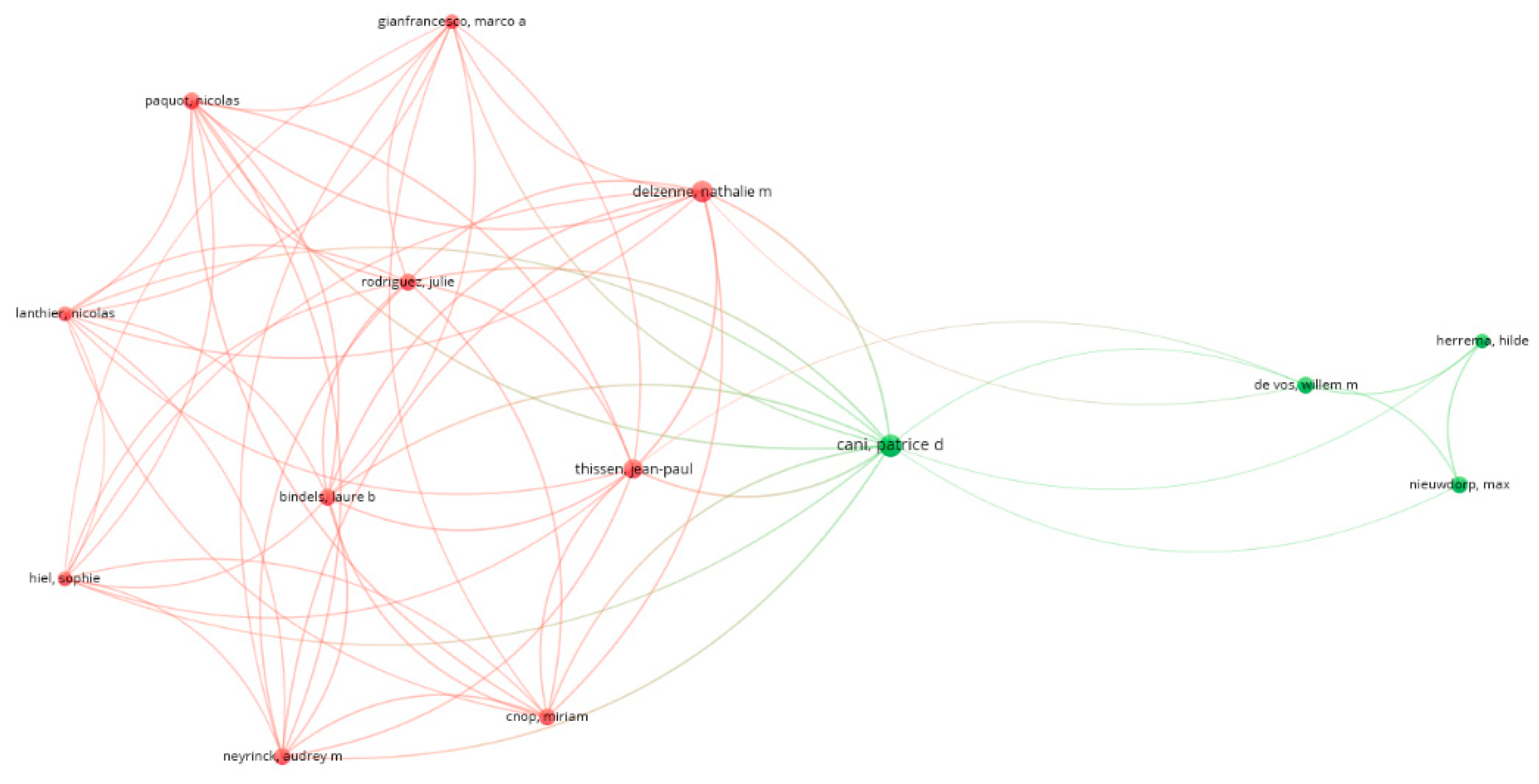

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis on Gut Microbiome in Diabetes

3.2. A Primer on Gut Microbiome in Diabetes

3.2.1. Introduction of Gut Microbiome

3.2.2. Role of Microbiota in Healthy Individuals

3.2.3. Pathophysiological Alteration in Gut Microbiome and Metabolomes

3.2.4. Mechanistic Abnormality Linking Dysbiosis to Type 2 Diabetes

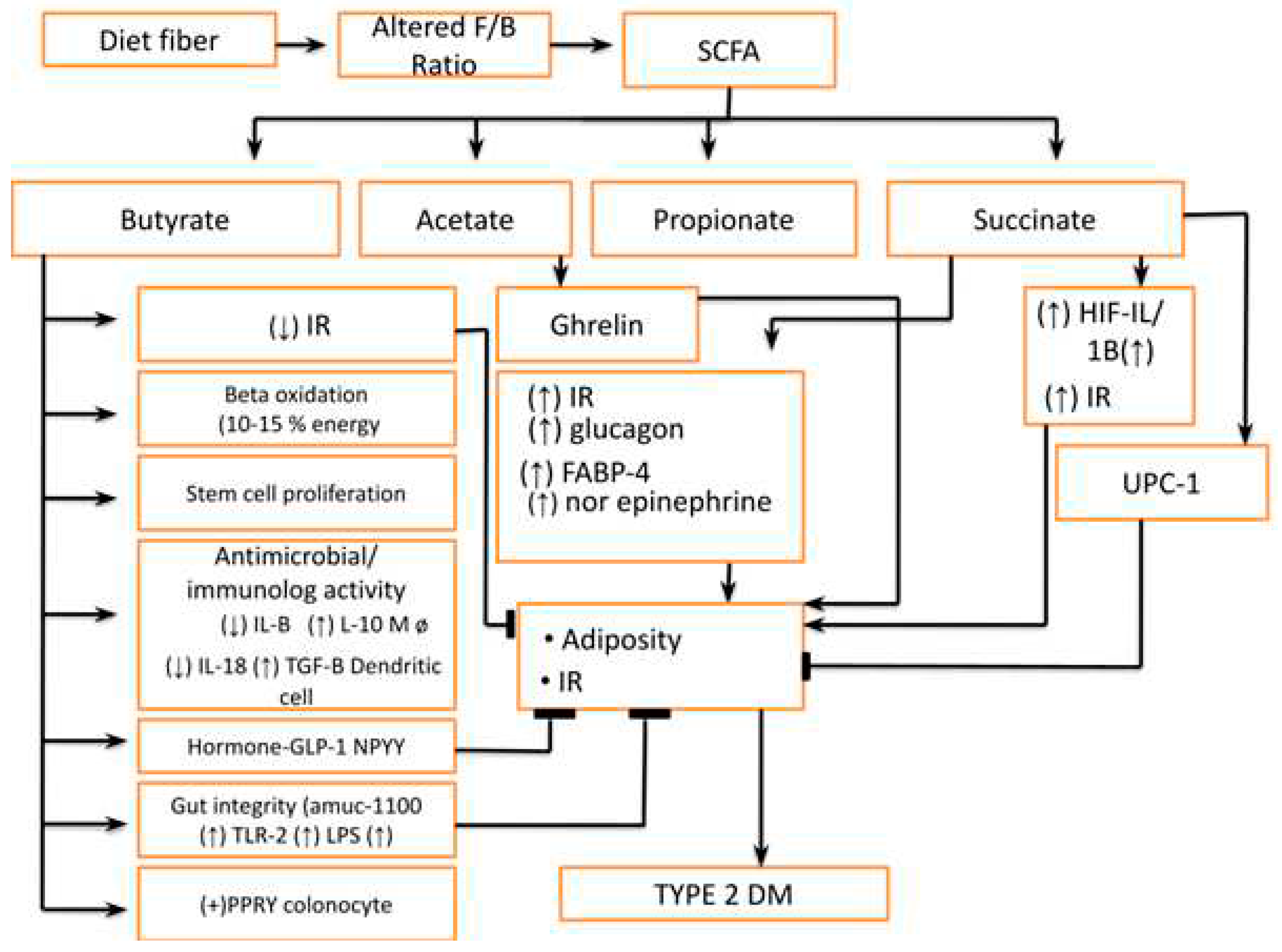

- Increase Famicutis/Bacteroides ratio leading to an abnormality in short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)production e.g.: Butyrates, Acetate, Propionates, and Succinates (Figure 5) The dietary fiber is fermented into SCFA by gut microbiota to produce either beneficial or deleterious effects. These short-chain fatty acids, mainly butyrate, are responsible for providing energy to host approximately 10-15% by beta-oxidation. The higher concentration of butyrate also inhibits stem cell proliferation by Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition and stimulates these cells to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, their role is very crucial in regulating healthy and deep crypts and villi in the intestine and they also regulate the blood vessel density in crypts and villi. Butyrate is also important in maintaining the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects in the intestine. The butyrate decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL1 beta, IL-18 &TNF alfa) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10, TGF-beta) [13]. Apart from this it also modifies immunity by regulating the gene expression in macrophages by HDAC inhibition. The butyrate also acts on surface receptors like G protein-coupled receptors (GPR) 41 & GPR 43 to release Glucagon-like Peptide-1(GLP-1) and NPPY (N-terminal dipeptide sequence )apart from IL-18. The butyrate also corrects adiposity by inhibition of Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) leading to unbinding of the histone protein complex of DNA. Butyrates also improve gut integrity in goblet cells by binding to Amuc-100 surface receptors leading to an increase in TLR-2. Furthermore, butyrate can also stimulate the Pancreatic Polypeptide YY (PPYY) legends in colonocytes. In summary, we can infer that SCFA has both deleterious and protective effects on metabolic health and local immunity in the intestine [14].

- 2.

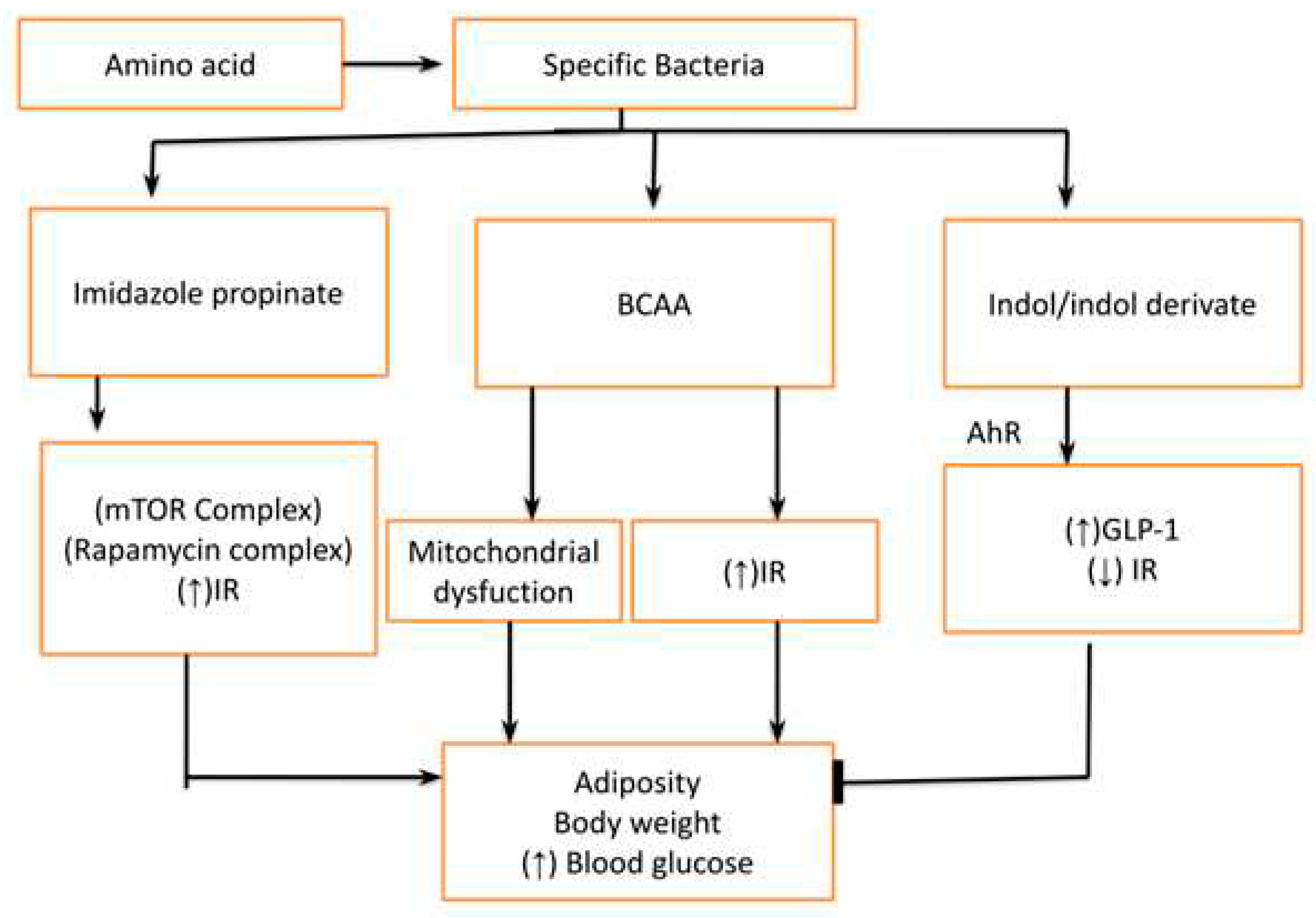

- Abnormal Tryptophan and other amino acid metabolites like branch chain amino acids (BCAA, Indol & Indol derivatives): The amino acid can also be degraded by specific bacteria to produce different metabolites which have an impact on metabolic health. The tryptophan is converted into imidazole propionate which activates mTORC1(Rapamycin complex) to cause insulin resistance at the level of muscle liver and adipose tissue. Furthermore, the bacteria also degrade different proteins into branch-chain amino acids (BCAA) which leads to insulin resistance (by mTORC1) and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, amino-acid derivatives like Indol/ Indol derivatives have a protective effect on metabolic health by reducing glucose intolerance and insulin resistance [15].

- 3.

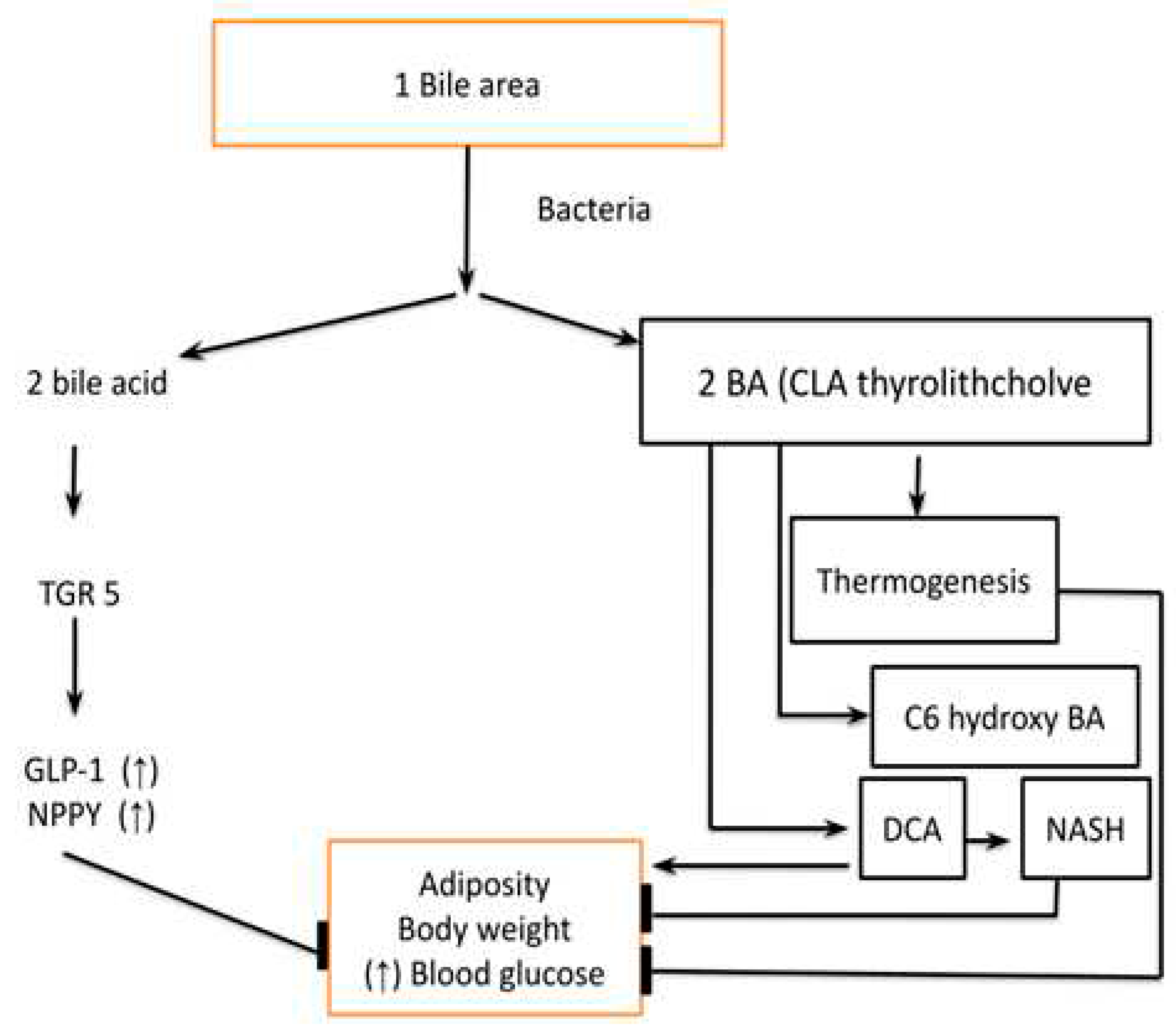

- Primary and Secondary bile acids have a role in regulating host metabolism, Figure 6. They act by binding to the Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) which is a nuclear receptor and the Takeda G protein-coupled receptor-5 (TGR-5). Both FXR and TGR-5 regulate the GLP-1 and NPYY secretion regulating host metabolism. The binding affinity of secondary bile acid is increased after deconjugation, dehydrogenation, and dihydroxylation by gut microbiota and gut microbiota diversity is an important regulator of the secondary bile acid pool. Apart from the above-mentioned receptors vitamin D receptor (VDR), Sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) also play an important role in metabolic regulation by these bile acids. Other important metabolites which are produced from bile acids are Thyro-lithocholic acid and 6 c hydro-bile acid which are important regulators of thermogenesis. Deoxycholic acid, which is a secondary bile acid causes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis by the FXR receptor. In summary, the FXR receptor is associated with both positive as well as negative effects on metabolism while the TGR-5 receptor has a predominantly positive effect. Furthermore, the bile acid also affects the type of microbiota and microbiota modifies the type and pool of bile acids, hence they have reciprocal relations [16].

- 4.

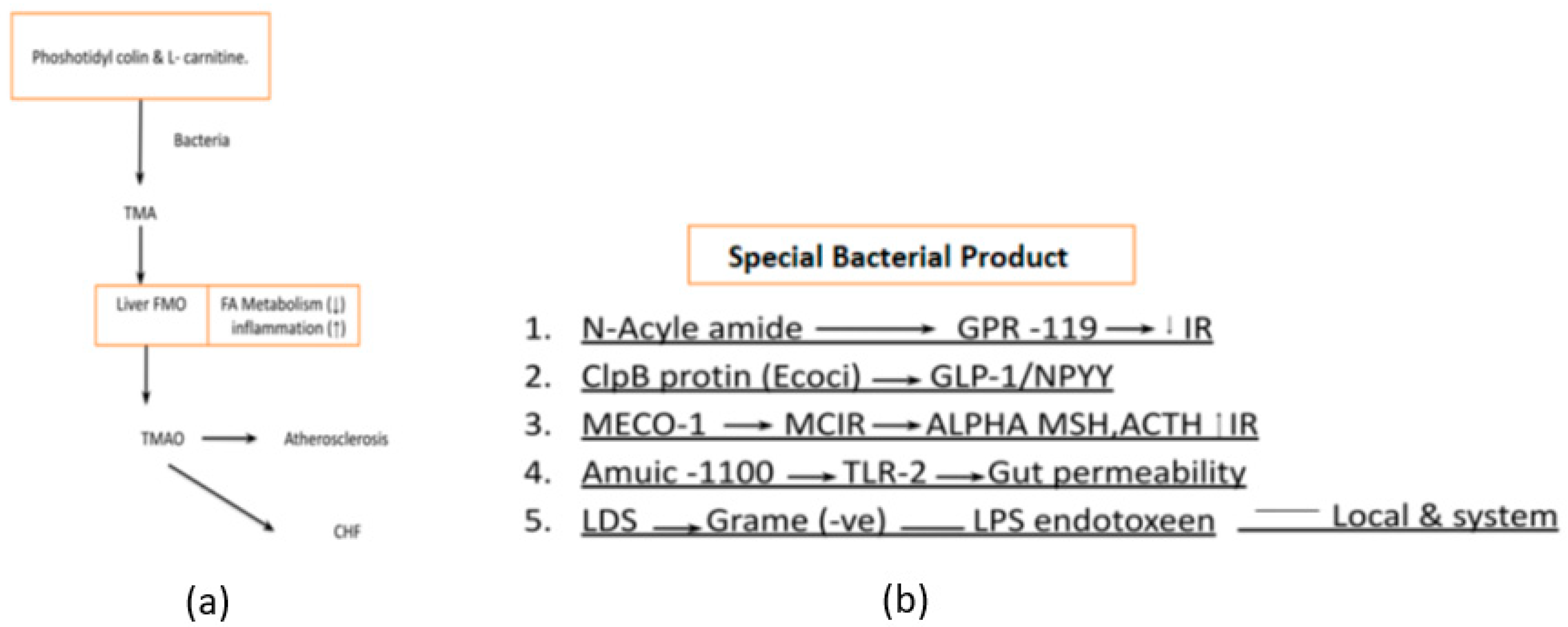

- Phosphatidylcholine and L-carnitine-derived metabolites like trimethylamine (TMA) which are later transformed into trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) by the liver are the main culprits of atherosclerosis and heart failure [17] Figure 7a. Bacterial products have diverse functions and are studied for their roles in various research fields, including immunology, microbiology, and infectious diseases They play significant roles in bacterial physiology, host-microbe interactions, and disease pathogenesis. Specific bacterial products like Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), ClpB protein, MECO-1(Mitochondrial Etiology and Cognitive Function-1), etc. are critical in the management of diabetes [18] Figure 7b.

- 5.

- Bacterial by-products also play an important role in regulating host metabolism. N acyl-amide & N acyl-serinol are two important products that act on G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) to improve glucose tolerance. Apart from this E Coli also produces ClpB protein which stimulates alfa-MSH (α-melanotropin), GLP-1, and NPY to decrease food intake. Furthermore, the patients with anorexia nervosa, the ClpB protein level is markedly increased as compared to normal individuals. MECO-1 is another bacterial product that has a resemblance to alfa-MSH and ACTH (Adrenocorticotropic Hormone) which increase anti-inflammatory activity locally to suppress anti-inflammatory cytokines. The last but most important bacterial lysis product of gram-negative bacteria is LPS (Lipopolysaccharide), which acts as a pro-inflammatory cytokine stimulator not only this but in the presence of increased gut permeability, it also leads to bacterial endotoxemia. This induces a chronic inflammatory state which eventually leads to obesity and diabetes [19].

- 6.

- Alterations in innate immunity, such as TLR5 receptor deficiency-mediated changes in gut microbiota and inflammasome-mediated TLR4 and TLR9 agonists, have been implicated in the context of diabetes. The interplay between innate immunity, gut microbiota, and diabetes is a complex and active area of research. Disruptions in the immune system, such as TLR5 receptor deficiency and inflammasome activation, can influence the composition of the gut microbiota and trigger inflammatory responses that may contribute to diabetes pathogenesis [20].

3.2.5. Therapeutic Alteration of Gut Microbiota and Diabetes Management

3.2.6. Interaction between Drugs Used in Diabetes and Gut Microbiota

3.2.7. Future of Gut Microbiota Therapeutic and Research Directions

- 1.

- What is the optimal composition of the gut microbiota for human health?

- The dominant gut microbial phyla are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes

- Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, with the two phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes representing 90% of gut microbiota.

- The relative abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in the gut microbiota has been associated with health and disease markers, with a higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes being associated with obesity and metabolic disorders.

- The relative abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in the gut microbiota has been associated with health and disease markers, with a higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes being associated with obesity and metabolic disorders.

- A healthy gut microbiota is capable of fermenting non-digestible substrates like dietary fibers and endogenous intestinal mucus, producing short-chain fatty acids that provide energy for the host and have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.

- The composition of the gut microbiota can be influenced by diet, with a high intake of fiber, fruits, and vegetables being associated with more diverse and beneficial gut microbiota.

- 2.

- How do different factors, such as diet, antibiotics, and probiotics, affect the gut microbiota?

- A high-fiber diet, particularly one that includes fruits and vegetables, can promote diverse and beneficial gut microbiota. On the other hand, a diet high in fat and sugar can lead to less diverse and less beneficial gut microbiota.

- Antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota by reducing species diversity, altering metabolic activity, and promoting the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

- Probiotics are live microorganisms that can provide health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. Probiotics can help to restore the balance of the gut microbiota and promote health.

- The gut microbiota changes with age, with a decrease in diversity and stability in older adults.

- Environmental factors, such as exposure to pollutants and toxins, can affect the gut microbiota.

- Some medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can alter the gut microbiota.

- 3.

- How can we manipulate the gut microbiota to prevent or treat specific diseases?

- Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that selectively stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria in the gut. Prebiotics can be found in foods such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

- Probiotics are live microorganisms that can provide health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. Probiotics can help to restore the balance of the gut microbiota and promote health. Probiotics can be found in foods such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut, or taken as supplements.

- Fecal microbiota transplantation involves the transfer of fecal material from a healthy donor to a recipient with a disrupted gut microbiota. FMT ( Fecal Microbiota Transplantation) is effective in treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections and may have the potential in treating other diseases associated with gut dysbiosis.

- Antibiotics can be used to selectively target harmful bacteria in the gut microbiota. However, antibiotics can also disrupt the balance of the gut microbiota and promote the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

- A healthy diet that is high in fiber and low in fat and sugar can promote diverse and beneficial gut microbiota. On the other hand, a diet high in fat and sugar can lead to less diverse and less beneficial gut microbiota.

- Prophylactic probiotics are used to prevent the development of diseases associated with gut dysbiosis. Prophylactic probiotics can be used in high-risk populations, such as premature infants and patients undergoing chemotherapy.

- 4.

- What are the long-term effects of manipulating the gut microbiota?

- Manipulating the gut microbiota with prebiotics, probiotics, or fecal transplants can improve digestive health and alleviate symptoms of functional gastrointestinal disorders.

- Manipulating the gut microbiota has been suggested as a potential strategy to prevent or treat various diseases, including metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and Clostridioides difficile infection.

- The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the development and regulation of the immune system. Manipulating the gut microbiota can alter immune function and potentially affect susceptibility to infections and autoimmune diseases.

- The gut microbiota is involved in the metabolism of nutrients and can affect energy balance and glucose metabolism. Manipulating the gut microbiota can potentially affect metabolism and contribute to the prevention or treatment of metabolic disorders.

- 5.

- How can we ensure the safety and efficacy of gut microbiota-related treatments?

- Preclinical studies can help to evaluate the safety and efficacy of gut microbiota-related treatments before they are tested in humans. Preclinical studies can include animal studies, in vitro studies, and computational modeling.

- Clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the safety and efficacy of gut microbiota-related treatments in humans. Clinical trials can include randomized controlled trials, open-label trials, and observational studies.

- The composition of gut flora is known to impact metabolism and glucose homeostasis. The relationship between gut microbiota and glycemic agents is considerably less well understood and is becoming a prominent topic of research.

- Adverse effects of gut microbiota-related treatments should be monitored closely to ensure patient safety. Adverse effects can include gastrointestinal symptoms, allergic reactions, and antibiotic resistance.

- Combining precision medicine and gut microbiota can improve drug efficacy and reduce drug toxicity. This approach involves identifying the gut microbiota composition of individual patients and tailoring treatments accordingly.

3.2.8. Challenges Associated with Gut Microbiota Therapies and Ethical Considerations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramires LC, Santos GS, Ramires RP, da Fonseca LF, Jeyaraman M, Muthu S, Lana AV, Azzini G, Smith CS, Lana JF. The Association between Gut Microbiota and Osteoarthritis: Does the Disease Begin in the Gut? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 27;23(3):1494. [CrossRef]

- Andoh A. Physiological role of gut microbiota for maintaining human health. Digestion. 1960;93(3):176-81. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck NJ, Waltman L. VOSviewer manual. Manual for VOSviewer version. 2011.

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of general psychology. 1997 ;1(3):311-20.

- Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome medicine. 2016;8(1):1-1. [CrossRef]

- Bashir A, Miskeen AY, Bhat A, Fazili KM, Ganai BA. Fusobacterium nucleatum. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2015;24(5):373-85.

- Reiss A, Jacobi M, Rusch K, Andreas S. Association of dietary type with fecal microbiota and short chain fatty acids in vegans and omnivores. J. Int. Soc. Microbiota. 2016; 1:1-9.

- Stokholm J, Blaser MJ, Thorsen J, Rasmussen MA, Waage J, Vinding RK, Schoos AM, Kunøe A, Fink NR, Chawes BL, Bønnelykke K. Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of asthma in childhood. Nature communications. 2018 ;9(1):141. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2019;17(6):383-90. [CrossRef]

- Tobin CA, Hill C, Shkoporov AN. Factors Affecting Variation of the Human Gut Phageome. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2023;77. [CrossRef]

- Levine A, Boneh RS, Wine E. Evolving role of diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2018 ;67(9):1726-38. [CrossRef]

- Siddik MA, Shin AC. Recent progress on branched-chain amino acids in obesity, diabetes, and beyond. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2019;34(3):234-46.

- Salvi PS, Cowles RA. Butyrate, and the intestinal epithelium: modulation of proliferation and inflammation in homeostasis and disease. Cells. 2021;10(7):1775. [CrossRef]

- Gasaly N, Hermoso MA, Gotteland M. Butyrate, and the fine-tuning of colonic homeostasis: implication for inflammatory bowel diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(6):3061. [CrossRef]

- Yang W, Cong Y. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2021;18(4):866-77. [CrossRef]

- Pushpass RA, Alzoufairi S, Jackson KG, Lovegrove JA. Circulating bile acids as a link between the gut microbiota and cardiovascular health: Impact of prebiotics, probiotics, and polyphenol-rich foods. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2021:1-20. [CrossRef]

- Rajakovich LJ, Fu B, Bollenbach M, Balskus EP. Elucidation of an anaerobic pathway for metabolism of l-carnitine–derived γ-butyrobetaine to trimethylamine in human gut bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(32): e2101498118. [CrossRef]

- Kobyliak N, Conte C, Cammarota G, Haley AP, Styriak I, Gaspar L, Fusek J, Rodrigo L, Kruzliak P. Probiotics in prevention and treatment of obesity: a critical view. Nutrition & metabolism. 2016;13(1):1-3. [CrossRef]

- Fan Y, Pedersen O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2021;(1):55-71. [CrossRef]

- Twycross J, Aickelin U. Towards a conceptual framework for innate immunity. In Artificial Immune Systems: 4th International Conference, ICARIS 2005, Banff, Alberta, Canada, August 14-17, 2005. Proceedings 4 2005 (pp. 112-125). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Wu H, Esteve E, Tremaroli V, Khan MT, Caesar R, Mannerås-Holm L, Ståhlman M, Olsson LM, Serino M, Planas-Fèlix M, Xifra G. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nature medicine. 2017 ;23(7):850-8. [CrossRef]

- Kant R, Chandra L, Verma V, Nain P, Bello D, Patel S, Ala S, Chandra R. Gut microbiota interactions with anti-diabetic medications and pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. World Journal of Methodology. 2022;12(4):246. [CrossRef]

- Khan I, Ullah N, Zha L, Bai Y, Khan A, Zhao T, Che T, Zhang C. Alteration of gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): cause or consequence? IBD treatment targeting the gut microbiome. Pathogens. 2019 ;8(3):126. [CrossRef]

- Liang D, Leung RK, Guan W, Au WW. Involvement of gut microbiome in human health and disease: a brief overview, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities. Gut pathogens. 2018;10(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, He X, Huang J. Diet effects in gut microbiome and obesity. Journal of food science. 2014;79(4): R442-51. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita T, Emoto T, Sasaki N, Hirata KI. Gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. International heart journal. 2016;57(6):663-71. [CrossRef]

- Scott KP, Jean-Michel A, Midtvedt T, van Hemert S. Manipulating the gut microbiota to maintain health and treat disease. Microbial ecology in health and disease. 2015;26(1):25877. [CrossRef]

- Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019;16(11):690-704. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Cai X, Zheng X. Gut microbiome-oriented therapy for metabolic diseases: challenges and opportunities towards clinical translation. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2021;42(12):984-7. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Liu J, Rhodes C, Nie Y, Zhang F. Ethical issues in fecal microbiota transplantation in practice. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2017 ;17(5):34-45. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Zhang T, Zhu H, Borody TJ. Evolution of fecal microbiota transplantation in methodology and ethical issues. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2019 ;49:11-6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).