1. Introduction

Although in a continuously decreasing number due to economic progress and demographic decline, many children in Romania continue to enter and live in the child protection system due to the risk situations in which they find themselves in their biological families. Protection should not only mean ensuring the necessities of life but also a construction and a reconstruction of the meanings according to which children and young people in these situations orient themselves in life and interpret their condition. Here, meaning is not just a philosophical concept to concern scholars in its "meaning of life" form. In the more mundane, psychological form of "meaning in life" [

1], the term can explain how individuals give meaning, purpose, and value to what happens to them, with beneficial effects on their development, maturation, and health.

Even so understood, the source and dimensions of meaning remain debated among researchers. There seems to be agreement, however, that one cannot talk about meaning without bringing up the purpose of the individual. Some authors consider the purpose the source of meaning. For example, the existence of a purpose - understood here as the cognitive process that defines goals in life - is the condition for the emergence of personal meaning [

2]. For example, suppose a person is a volunteer (he or she has a purpose). In that case, this activity somehow structures how he lives and, very importantly, manages the resources he has at his disposal. "Purpose gives direction just as a compass gives direction to a navigator" [

2] (p. 242). Thus, the goal is the one that can generate both understandings (depending on the goals, the perspective on oneself, and things that want to be changed) and also the value and significance of one’s person (when the objectives pursued are socially valued). Another definition of meaning holds that it is the necessary condition in which goals can develop: "Meaning is a network of connections, understandings, and interpretations that help us make sense of our experiences and formulate plans that direct energies toward achieving desired futures" [

3] (p. 165). A broad review of the differences and similarities between meaning and purpose is in [

4].

As a dimension of meaning [

5,

6], the purpose is the mission everyone believes they have to accomplish and for which it is worth living. Purpose consists of long-term aspirations, self-concordant and motivating relevant activities that one carries out [

7], giving a specific direction to one’s life and particular activities. The motivational force of the goal would lie in the fact that the activities of the present are related and connected with the projection of future events [

8]: "I study to get a degree," "I work for the promotion". The goal can also refer to one’s person, not only to external projects. Individuals project images of the people they want to become in the future or who, on the contrary, they do not want to be, and these images can represent landmarks in the paths they choose to follow or avoid at a given moment [

9]. In a comprehensive definition that also refers to the Self and its projects, "purpose is a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something meaningful to the self and leads to productive engagement with some aspects of the world beyond oneself" [

10] (p. 32).

Psychologically, individuals who experience purpose have a clear sense of their life’s direction and the goals they are pursuing, resulting in a motivation to achieve them. On the contrary, those who experience a low sense of purpose feel that things are pointless and nothing in the future seems valuable and, therefore, not worth the effort of involvement [

5].

The presence of purpose in life would act beneficially through several elements [

2]:

determines, through motivational mechanisms, a greater consistency of behavior that manifests itself through the determination to overcome obstacles, search for alternatives, and to maintain focus on objectives despite environmental changes;

encourages psychological flexibility;

encourages efficient resource management and leads to more productive activity;

encourages higher than basal cognitive processing (such as procuring food, safety, and pleasure).

Research conducted among young people has highlighted [

4] associations between the perception of having purpose/goals in life and increased social well-being, courage, and desire to acquire adult status. At the same time, a goal constitutes a resource for supporting resilience in overcoming some adversities. A sense of purpose correlates with a greater capacity for action and positive emotions; the purpose can provide youth with a protective buffer that mitigates the negative outcomes associated with poverty, strengthens motivation and sense of participation, and facilitates identity development.

On the other hand, the presence of meaning as purpose only sometimes guarantees success and social integration. Some researchers associate teleological thinking (which is the basis of the perception of phenomena in terms of purpose) and teleological error (seeing purposes where they are not) with the perception of meaning [

11].

Meaning-mattering refers to valuing one’s life as meaningful and valuable, that it matters because it adds to the world. It is expressed by the feeling that the individual lives a life worth living [

1] and that what you do is relevant to others. Those with a low sense of significance believe their existence has little relevance and their disappearance would make a negligible difference in the world [

5].

Our research aims to explore two dimensions of meaning for adolescents and young people who are in or have grown up in the protection system from Iași County, Romania, respectively the way they perceive themselves and the value they think they have and on the other hand, how they design their future through the goals and objectives. A qualitative approach can contribute to a better understanding of how those in this situation make sense of what happened to them and how these components of meaning have been influenced by experience in the protection system so that this knowledge helps to improve the means of intervention, the living non-material, symbolic, conditions of those in the protection system, and the social integration efforts in their case.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is part of more extensive research carried out in 2023 that follows the mechanisms of interaction between the individual and the environment in the case of adolescents and young people who grew up for different periods in residential homes in Iași County, Romania. The county is in the northeast of the country, in Moldova, the country’s poorest region, with about 700 children and young people protected in public residential care and approximately 1500 children in foster care. Currently, the national policy is to make efforts to keep children in the family of origin, but this is not always possible. However, the number of those cared for in the residential system has fallen dramatically, from a few thousand in the 2000s to a few hundred today.

2.1. Study Setting and Sample

Data were drown obtained during three focus groups attended by N = 35 pre-adolescents, adolescents, and young adults between the ages of 13 and 21 (M1 = 17.27 years). The periods in the protection system vary from a few months to 20 years (M2 = 10.35 years). On gender, 21 (60%) respondents were girls, and as studies, most (20) attended high school courses while the rest were working or looking for a job.

The respondents came from residential protection and post-protection services in the Municipality of Iași (approximately 350,000 inhabitants), the capital city of the county: two residential houses (FG1 and FG2) and two multifunctional centers (FG3), post-residential service where there were young people who left the protection system, being, at the time discussion, engaged or looking for a job. The interviews unfolded in the respective organizations, and the selection of the interlocutors was based on their availability at the time of the research and was voluntary. Although the ages are close, their educational and social situations differ, which makes the groups quite heterogeneous: most of the respondents in FG1 had a relatively good social condition; that is, they generally came from responsible families, and the protection necessary to be instituted because the parents did not have the means to keep them in school, despite good academic results. On the other hand, FG2 members were victims of abuse (some severe) and neglect. Finally, the young people from the multifunctional centers (FG3) had left the child protection system, were no longer attending any school, and were looking for a job or were already employed being in a transition period of a maximum of two years between the residential care and integration into society.

2.2. Procedure

Before each interview, the participants received an explanation of the research purpose and settings and confirmed their consent. The legal guardians gave their consent to the minors before conducting the interview. Discussions lasted 2-2.5 hours and were audio-recorded, a procedure for which agreement was sought in the informed consent. The Scientific Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social-Political Sciences from "Al. I. Cuza" University of Iași approved the study.

2.3. Measures

The interview guide was built based on the review of specialized literature and the researchers’ experience. It covered the subjects’ experience in the protection system, how they relate to the past, their families and other people, and their plans. The discussions were unstructured; the young people had great freedom in leading the debate and describing their experiences. The fact that the members of each group knew each other helped the flow of the discussion. However, at some moments, it generated the manifestation of latent resentments, which required the intervention of the interview coordinators.

The interview questions, and the discussion topics proposed to our interlocutors from which the particular questions emerged during the meeting, were built on a model of resilience, understood as survival in adverse conditions [

12] where what matters is overcoming risk situations and not recording outstanding results. Another model envisioned is one in which the delivery of resources, experiences, and relationships in culturally intelligible (meaningful) ways to the individual [

13] is at least as important as their presence. From the beginning, the methodological orientation was an interpretivist one in which we followed how our interlocutors evaluate and value experiences, resources, and themselves being less interested in their objective accuracy. However, the discussions started from the facts and their descriptions; details and evidence were requested when the statements were vague or accusatory. Only after these aspects became apparent their interpretation and evaluation were requested.

The interview mainly aimed at developing a relaxed and honest discussion about their experience in the protection system, the narrative following a chronological logic (past-present-future). In this development, the opening questions asked the interlocutors to describe the reasons and circumstances in which they arrived at the center in an attempt to assess the adversity they faced at that time as well as the role of the family in this situation. Later, in the course of the discussion, questions were asked about life and experience in the placement center, focusing on social resources (even though the respondents, especially the younger ones, preferred to focus on material resources) within and outside this organization, such as relationships with employees and the development of friendships, but also any significant experiences during this period.

Regarding the relationship with those outside the center, we asked how they see them and how they see others if they consider that they have advantages and or disadvantages compared to them. For those who were still students (FG1 and FG2), we paid particular attention to the importance and role given to the school. This vital resource contributes to charting the future trajectory of development. A central question that evolved from all of these experiences and resources was "When it was hardest for you, who or what did you turn to?" which sought to capture the source but also the interpretation and personal use of the resources and development opportunities available to them during the period they are in the protection system. Finally, at the end of the discussion, we asked the interlocutors to tell us their short-term and long-term plans, including the opportunities and the obstacles they imagined they would face.

2.4. Data analysis

The type of data analysis was thematic. We transcribed and coded the interviews using the QDA Miner Lite v. 2.0.9 application. The data coding strategy focused on description, an approach "appropriate for studies with the main purpose of identifying or describing specific behaviors, settings, phenomena, experiences and events" [

14] (p.29).

The type of coding was In Vivo, where a code is expressed by a word or a short phrase extracted from the participants’ language. [

15] This coding technique identifies the relevant information as it appears in the respondents’ accounts and preserves the language and meanings without being affected by the beliefs and biases of the researcher. Each team member developed a list of codes, starting from a series of 10 agreed-upon anchor codes. We later analyzed both lists and merged them without measuring our agreement, resulting in a final list of 81 items. We have had situations where "family is a good thing" and other situations where "some things happen in the family that are not good". Later, we grouped these codes into categories such as "family as a resource" and "family as adversity," and after that, more general categories such as "resources and support" (what supports positive development) and "threats" (perceived obstacles) or "we are similar to others" and "we are different from others". This process of ordering and classifying the information was done considering the purpose of the research and the theoretical framework, overcoming the descriptive level of the codes expressed in the words of the interlocutors towards a theoretical and analytical level of data explanation [

16].

Further, once these categories were established, connections could be made between them [

17], thus foreshadowing the themes obtained. For example, a particular way of being young (an attitude of superiority) is not (only) a temporal succession of past events but can be a reaction to these experiences.

3. Results

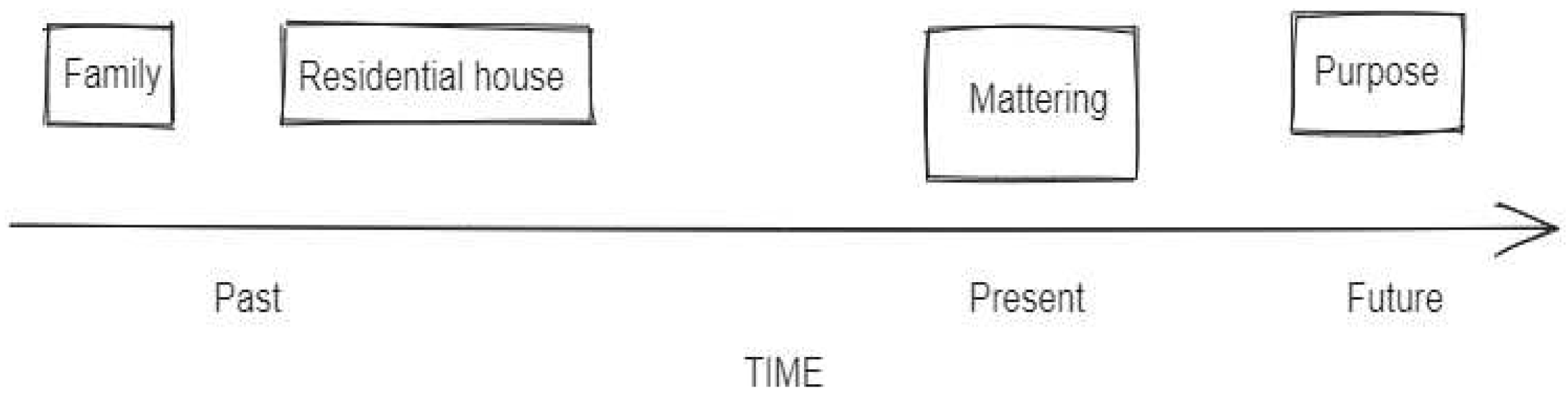

Through the approach described in the previous section, the (chronological) stories of teenagers and young people were analyzed from the perspective of the research goal: finding out how the research participants perceive themselves and how they project their future through objectives, goals, and plans. The initial chronological logic is supported by the fact that the components of meaning - mattering and purpose - are not theoretical, abstract constructions but result from interpreting particular experiences situated to a large extent in the past (

Figure 1).

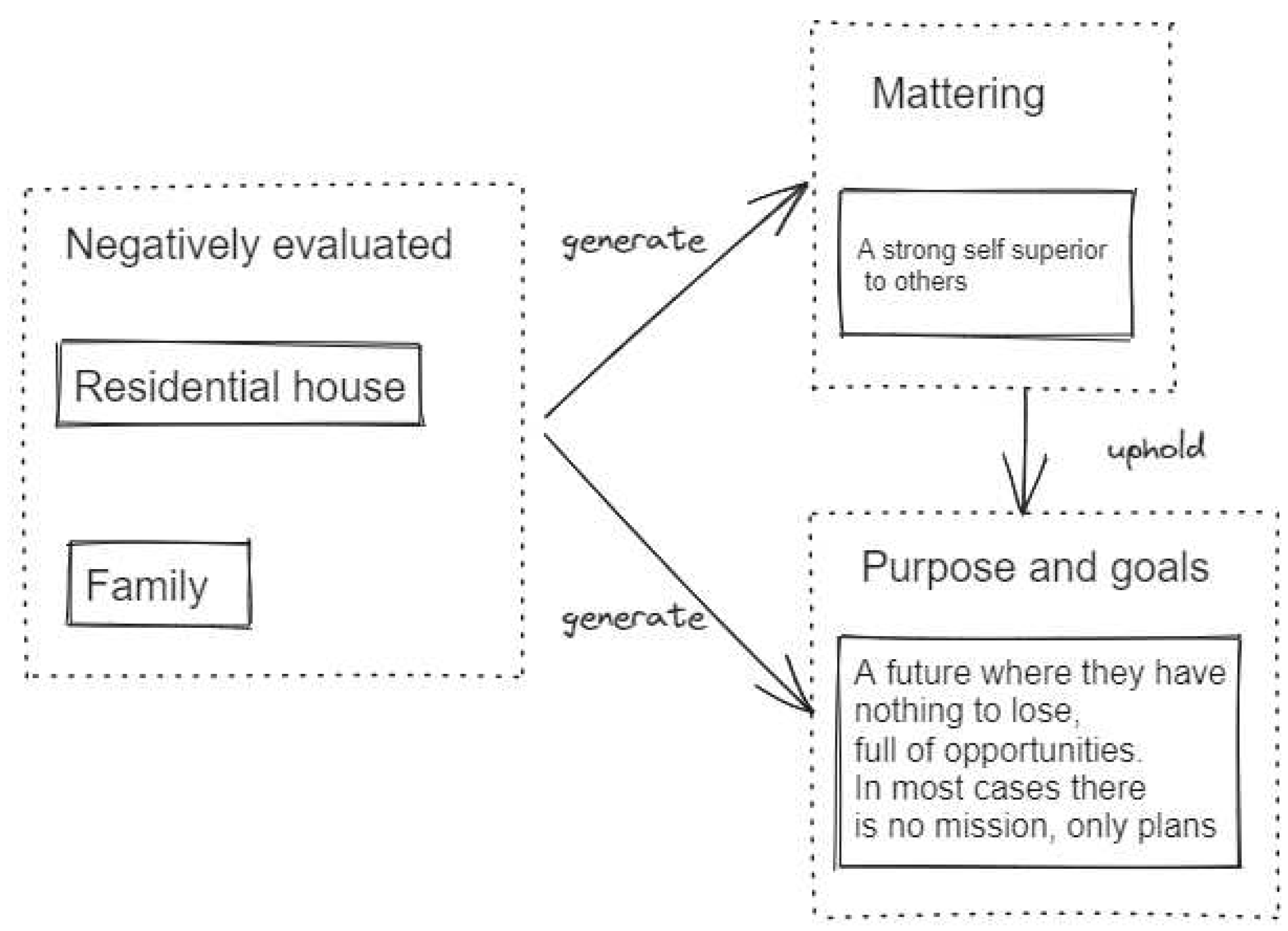

Further, the data analysis aimed to understand the processes by which the past influences the life course of young people. In the case of this study, we have situations of abandonment or neglect by the biological family and the need for protection in the residential system. The protection system thus became the second home. However, the birth family also continued to exist and exert its influence, these being the main elements that contributed over the years to their development. One of the emerging themes of the study is that both instances, the residential care, and the family, have largely failed to support our interlocutors, who, for this reason, see themselves as the primary source of resilience. This conviction also comes from a comparison with young people who have not gone through their experiences and who would thus be weaker and less prepared in the face of life’s vicissitudes. Given the perception of one’s superiority, the future appears in a favorable light, full of opportunities. It is a positive fact that does not consider the multiple risks to which they are exposed given the lack of support - relational and material - of this category of people. Emergent themes and codes appear in

Table 1.

3.1. Social resources: the family and the foster home

For the teenagers and young people, we spoke with, the assessment of the family and the placement center is permanent because they continue to represent their projects’ current and potential future resources. However, they are disappointed with how the two actors have done their duty.

Our interlocutors were excited to talk about their experience in residential care. On the whole, they are dissatisfied with it, but unlike what specialized literature records about such services in other historical periods, now the dissatisfaction is generated by the way the residential house activity is organized, by the lack of variety of meals ("Could we eat fries more often?"), in general, by the bureaucratic way of purchasing hygiene items and clothes. These products ultimately lead to waste because children and young people reject and throw away the products thus purchased because they do not suit their wants and needs and are of poor quality.

A recurring dissatisfaction in the answers regards the attitude of the employees accused of formalizing relations. This distance is perceived as indifference or even ill will by the beneficiaries. There is and is perpetuated a state of conflict in "factions" that do not understand each other.

Teenagers and young people do not seem happy with the residential care situation, but things seem good compared to the family situation. The attitude towards the family is ambivalent. As for anyone, the family is a support and a benchmark, but in this case, many families did not fulfill their mission, and the law protected the children. One interlocutor told us that the family is not an unconditional resource, regardless of the situation.

(The worst thing that can happen to a child is) the loss of important people: parents, friends, and close relatives. OK, this only happens when you are attached to them. You are unaffected if you have some of these things in your family.

(FG2)

These "happenings" that have occurred completely change the role of the family for them. However, those speakers do not generally hold grudges against the families of origin. They try to keep in touch with the parents, but this is not always possible because there are complicated situations that they cannot control: they were born out of wedlock, the parents have (re)married, and often the new partner does not want to hear, or he really does not know about them, or the families have disappeared altogether.

Looking back, young people feel, at best, indifferent to family and the protection system. The families had and still have problems, and in the residential home, they encountered a lot of indifference and bureaucracy. They do not reject these experiences but are neither a source of inspiration.

3.2. Self-image and self-worth

The self-image was evaluated in two directions: how the young person sees himself and positions himself to others in the peer group (colleagues/acquaintances of the same age). The intention was to capture the value the young man gives to himself, the importance he considers to have after he has passed, and was still passing through at the time of the interview, through difficult experiences.

3.2.1. Self as a benchmark

Looking with distrust at the residential house’s employees and the families they come from leads to extreme situations where the only perceived marker of their resilience is themselves. Young people accept themselves with indulgence and understanding, a conclusion that arose due to disappointments and lack of support.

I am proud of myself. Very much! I feel that despite everything that happens, I still come out happy; I keep smiling, I try not to let be overwhelmed by all the bad things happening around me, and I try to be more and more positive. That motivates me to do what I set out to do. Anyway, I am so happy with myself; I feel that way. Other times I don’t feel it, but for the most part, I feel it.

(FG2)

When it is harder, I look in the mirror and say, "You are all you have!". I learned that I am the only person for whom I develop myself!

(FG3)

I would not want to change anything about my past because the things of the past shaped me and made me the person I am today.

(FG1)

I cannot say that we have surpassed that problem, let us say. But I try. It cannot pass, but you learn to live with it, which is the reality. I just saw that things don’t stop like that, or it cannot pass, and I said, "That is it, that is me; I accept myself as I am. If it suits you well; if not, no!" I love myself as I am.

(FG2)

I get laughed at because I stumbled upon those walls and had to learn and manage in their absence (of adults). I had the strength to get up, start over again, see if things (worked) and adapt to the situation.

(FG2)

To the essential question of the interview, "When it was more difficult for you, who or what helped you?" the most frequently formulated answer was "Me". Thus, a personal definition of the Self emerges, built on mistrust of others, in which trials, vicissitudes, adversities, and risk situations (overcame or not) have contributed to the person’s formation. A feeling of inner strength and self-confidence emerges, becoming a sense of superiority over others.

3.2.2. Self to others

In this framework of meaning, having a family is not an advantage but a disability because those who have families with parental support are less prepared for life.

On the one hand, it is good that I didn’t grow up in a family because I did it that way, out of everything! I tried to handle it even though sometimes I would have difficulty saying, "Oh, that is it! I cannot do it anymore!" I kept succeeding later, but I was succeeding.

(FG2)

From the need for identity and to give meaning to one’s experiences, there eventually even emerges a feeling that "we" (those who have faced such experiences) are better than "them" (those in the family).

We, kids in the system, are much better than some kids growing up in families. We are much more educated, much more open in mentality.

(FG2)

(We are) More mature. And more mature than adults. Many people have told me that I am more mature than my mother.

(FG2)

I am more prepared in socializing, understanding, and conversing with people. That is because, sitting with more people, I had to communicate and get along with those around me.

(FG3)

The fact that he had to take care of himself turned into responsibility, obviously only in the case of some.

We are somehow on our path; we don’t depend on our parents. When someone asks us what we are going to do in the future, "Yes, I am going to finish school, and then I am going to get a job, and then I am going to have a family", the people in the family don’t always think that way. "My mother keeps me, (...)" And so on.

(FG2)

It is different from being on your own feet; if I make a mistake, that it’s, and I bear the consequences. I have to go to work, earn money to eat, support myself, and pay utilities; no one has to help anymore.

(FG3)

This feeling of superiority comes in response to contempt and discrimination from others. The highly negative attitude towards others comes along in one’s self-narrative, describing himself as a person forced to manage by his powers. This self-story is supported and supplemented by the narrative describing others as unhappy.

I am OK at the residential house, but you, who judge me for staying here, at your home, maybe worse. You (can) have difficulties when your mother and father beat you. I may be doing better than you, and yet you are the one who judges me as "Oh, you are staying at the residential house!" but you are doing worse at your house than I am doing it here.

(FG2)

They have everything they need materially. Nevertheless, they have no affection.

(FG2)

In vain, you have the phone. I don’t know if it does not love you and does not listen to you when you have problems.

(FG2)

However, when they look more closely at their situation, some interlocutors notice that they are not as good as they describe themselves and that the lives of others are not as miserable as their peers describe them.

What I find bad about the fact that I stayed where I stayed is that I felt that way a few years ago about how the world talks, how they dress, the opinions of people, and how much the world develops. For example, I don’t know simple things for normal people, like files and taxes. Nevertheless, their parents still explain them in more detail. They have someone to turn to; they can ask the parents.

(FG3)

The need for personal meaning makes these young people describe themselves as the heroes of their own lives, even if they need negative characters to oppose them. The past (trauma of separation from family, family) and the present (life in the residential house) are gradually integrated into stories that make sense to those who tell them, stories with a tragic-optimistic touch: "It was and still is hard, but all this they made me who I am, different from others who had everything in life! Despite everyone and everything, I am a person I am proud of!". These self-beliefs foreshadow the future through fixed goals and plans, a future that is exclusively personal and outside the restrictions but also far from the support of the protection system.

3.3. Purpose and objectives

Young people do not consider themselves inferior to their peers brought up and educated in their families, or even in many cases, they consider themselves superior. The future projects do not differ from those of ordinary children. Younger children in FG1 and FG2 generally have school-related plans, while older participants in FG3 were more concerned with work and money. On a case-by-case basis, the respondents wanted to take the qualification, finish high school, and take the college entrance exam (Medicine, Military Academy, Arts). On the other hand, there is a desire for success, a success to be expressed by ostentatious material "evidence".

I want much money, a big villa, and a man.

(FG1)

In the future, I would see myself as a very wealthy person. I dream about it, and maybe, if it were to come out to me, to be a businessman.

(FG1)

To work to get a big car to brag to the gentiles, not to make me "poor" anymore.

(FG2)

I want to work abroad to get a car and a house to brag!

(FG2)

I hope this dental medicine thing comes out to me. I always dreamed of having a lot of money, buying many clothes, and having pets.

(FG1)

Even fulfillment, which is an inner feeling that accompanies the achievement of a goal [

19], is also wanted to be proven by reaching these social and external indicators of well-being:

I will do certain things to show myself that I did it and could do that. Not to prove to anyone that I did that thing or succeeded! To be successful, to be able to be myself well! First, to be healthy, then the rest! I want to be fulfilled, have my car and home to afford the things I want, and travel! This stuff I make them be for me, not to prove.

(FG1)

In many cases, abroad is the miracle solution, a shortcut for fulfilling dreams, desires, and projects. Although he had met his mother on Facebook, one of the young people was looking to go to Germany at her invitation to start working and earn money. His enthusiasm, not based on many concrete things, may also show the vulnerability of these people who are not enough to have goals, as the theory suggests. Moreover, individuals or organizations can exploit the desire to fulfill some worthy goals and thus become a danger to its holder.

To me, they are not dreams; they are real realities. I am leaving outside in the first month that comes. I am going to Germany, where my mother is. I want to see what working and earning a penny is like. Because here the salaries are not right, I want to see something more.

(FG3)

Young people do not lack goals and plans. This ability to set goals as high as possible is a virtue.

Some people tried to discourage me but failed, and they said, "Do not think so far!" "But what is the problem? I think because I want that object! I want to aim up there!" When asked and I started bragging about what I had in my head, she would say, "Yes, but it is not as easy as it seems!" "I am going to make it seem easy! What is the problem?"

(FG2)

The interlocutors intuit the connection between goal and achievement but do not question the means and resources necessary to achieve these goals.

Probably even adults don’t trust them or their dreams because, at a certain age, they have a hard time and say, "Oh, I cannot!" but I don’t put that ambition "Let us shoot a little bit more of myself, I will succeed, I will have it!"

(FG2)

When asked what they think would stand in the way of completing their projects, children and adolescents believe that it depends only on their involvement without thinking about any inherent social obstacles, not only for those in this position but for any young person their age.

[What would you need to fulfill these plans?] I don’t know! Simply my work. It is all up to me and how much I want that.

(FG1)

These beliefs create an unrealistic model of success in which all that matters is setting a goal and wanting to succeed.

Often, the aims and the means used to achieve them are mismatched. In this case, the goals are dreams, burning desires for the fulfillment of which not much is done because one does not know what or out of convenience.

(I want to become) The greatest doctor. I don’t know in what field, but doctor.

(FG1)

I also wanted to become a policewoman, but only with the thought (because) I remembered that I had to learn! College, I don’t need it anymore! So far, I have to learn much and dislike learning! I don’t like to sit with the book in my hand. I am learning just to pass the class and give my baccalaureate!

(FG2)

Too many requirements. It makes you mentally tired.

(FG2)

Yeah, in college, only that thought. Too much to learn.

(FG2)

I was thinking of starting to write something myself, I have many ideas, but I am a lax professional and can never finish anything.

(FG2)

Many personal projects are already affected; they attend non-prestigious or even low-level schools that have nothing to do with the projection of their future. There is always the solution of further schooling in the desired field, but these people already have the available resources reduced.

I wanted to be a fashion designer but became a confectioner-pastry chef. I don’t like it. I wanted something else.

(FG2)

Environmental protection, but I don’t like that I have to learn. I would not give up if I knew I had learned so much.

(FG2)

However, a few real examples integrate plans with young people’s skills, training, and experience, making these projections more convincing about future developments.

I want to become an excellent barber and get an enormous salary because at the salon that I am... I am new, and I am already taking a decent salary. If I have experience, not experience because I have experience; if I have seniority, if I stay longer, I start to know my clients, and the more clients, the more money. After I get a decent salary, as I want, and I will have the experience to do something else, I will focus on another field to bring me extra money.

(FG3)

I would not change anything in the past, at the moment, to be stronger, and in the future, I would like to save the country and enter the Land Forces Academy. I was in a camp organized by the army and met a military family supporting me in this project.

(FG2)

I want to finish school, give to a chef’s course, love the kitchen, have a good job, and buy a house.

(FG2)

All three respondents in the paragraph above have benefited/taken advantage of opportunities offered by the protection system: the first young man enrolled in a barbering course paid for by Child Protection, and the second was in a camp organized by the army while she was in the residential care. The third takes remedial courses, which he is unlikely to have attended if he had stayed home.

4. Discussion

It follows from the above that there is a wide variety of ways in which young people in the protection system relate to themselves and give meaning to the reality they live in, the past, the present, and the future.

Residential care, at least at first glance, is an organization where those who arrive here, people who have suffered various deprivations or were victims of abuse, receive the same resources - material and social. However, this statement can suffer many nuances: the traumas suffered by children are never identical, just as neither are the residential houses, social resources differ in the provision and the way the personality receives them, the way of being of the child [

19,

20], the time of hospitalization with effects on children’s development [

21] is also different.

In general, the protection system did - with some concessions that at some point may be important for the quality of life of the beneficiaries - what it was supposed to do: it protected those concerned from much more serious harm that they would have suffered if would have remained in the biological families. The children admit that it was better for them in the residential care; however, many still feel that others (colleagues, teachers) a kind inconsideration, to which they respond with an arrogant attitude of contempt, even transferred into a specific identity: "We are not like them, we are better because they did not go through what we went through!".

To a large extent, these children and young people consider that they have nothing in the minus but some advantages compared to those raised in families. Their life appears to these young people as meaningful, not by what they add to the world but by the sufferings and negative experiences they have overcome. This attitude justifies them developing a thorough understanding of the experiences they have gone through and even generates a culture of superiority determined by the management of uncertainty [

22].

They consider themselves as entitled as anyone their age to hope for a positive future, focusing on goals that express, especially materially, the success and overcoming of their condition as marginalized children. Unfortunately, many essential choices about choosing a school or acquiring skills have already been made, potentially narrowing their options for the future. They aim to succeed in life, primarily materially, relying on their image of survivors. Surviving in a partially hostile world seems to be their purpose, and money and success are the means to that end. Few aim for personal achievement, and none of the interview participants let it be understood that they had a "mission" above him. We illustrated the development of this process in

Figure 2: The self-image of the survivor and the strong individual feeds into that of the individual who succeeds in all circumstances and is convinced of future success in his endeavors.

We have noticed that these young people are not lacking in goals but in methods and concrete plans for their implementation. Between two people who are on a path of development and one of whom has bold goals (he wants to become a lawyer) but does nothing to achieve them, and another person who has more modest goals (he wants to become a popular barber) but already applies them and evolves in achieving them every day, the development towards success belongs, most likely, to the latter. An unrealistic goal for the achievement of which the individual does nothing can be dangerous because interested persons can maintain this illusion and manipulate the child into harmful situations (trafficking, abuse). The goal and objectives can thus become, from a potential resource, a risk factor for the one in question.

The perception of these young people is that they have all the options open without considering the constraints and limitations of their particular situation. For example, our interlocutors did not observe or ignore the family’s role as a safety net. A child in the family allows himself to fail several times in his attempts because he has the support of those close to him. The capacity of the public child protection system to support young people after they leave school is close to zero, so they have much less opportunity to fail/try than others. However, the young people we have discussed mainly see only the advantages of the trials they went through, which is very good, without considering the possible social handicaps with which they enter the labor market.

The explicit desire to have money or other external signs of well-being (villa, swimming pool, car) to the detriment of projects aimed at fulfillment can be a self-limitation of future projects to real constraints: it seeks to he goes abroad to make money because this is the only model available to him when he is in a position to make concrete decisions.

On the other hand, everyone we talked to has goals and objectives to achieve, which gives them some meaning in life as long as they have something to do. The fact that the young ones have goals related more to school and the older ones to jobs may also mean that the latter have adapted their objectives to the means, which is okay. Further, as long as they do not involve involvement in criminal activities and as long as they are realistic (in the sense that they are appropriate to the means), these alternative paths of development are in no way inferior to others and constitute goals that give meaning to life.

The research is helpful because it explicitly shows how young people think about themselves, the world, and their opportunities, a representation that makes them act in specific ways. This way of understanding, from the inside, can be extended to other groups of teenagers and young people and can contribute to understanding other phenomena, such as career choice, juvenile delinquency, or human trafficking.

A continuation of this research may consist in the effort to answer why some children/youth take advantage of the opportunities in residential care more than others. Our research would be helpful to be continued by following the elements that influence meanings and goals (individual characteristics, experiences, time spent in the protection system, family history) as well as by interviews with adolescents and young people in these situations to decode the particular way in which they represent their trajectories and how they connect with future projects. Another possible research direction would be to analyze specific resources (such as school or family) by considering them as factors in parallel with how adolescents interpret them. As we stated, development is not only a problem of resources but also a problem of interpretation. The ideal research that captures the relationship between development and meaning would measure the variables involved, not just describing them but also longitudinal research that follows the specific process and interaction of the two components tracked here.

5. Conclusions

The empirical research findings can be a part of the broader discussion about development and resilience in a framework that goes beyond the provision of resources (material, social, financial) and refers to how these resources are perceived, valued, and given meaning. At the highest level, our findings conclude that meaning (understood as purpose and mattering) can be both a tool for knowing the other’s reality and understanding their behavior, emphasizing young people’s relationship with the future and themselves.

At the individual level, meaning is an unconscious tool with which individuals operate to represent and orient themselves in the world. Nevertheless, as with any device or feature, it must be used with discernment and considering as many implications as possible. As with intelligence, for example, the ability to make sense of available resources can be dangerous to the individual and society when directed in socially unacceptable directions. Under the environment considered here - the residential protection - where supervision, counseling, and support are lower than in the family, the danger of misinterpreting reality and projecting unrealistic goals is permanent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B. and D.C.; methodology, O.B. and D.C; formal analysis, O.B. and D.C; investigation, O.B. and D.C; resources, O.B. and D.C; data curation, O.B. and D.C; writing—original draft preparation, O.B. and D.C; writing—review and editing, O.B.; visualization, O.B. and D.C; supervision, D.C.; project administration, O.B.; funding acquisition, O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was co-funded by the European Social Fund, through Operational Programme Human Capital 2014-2020, project number POCU/993/6/13/153322, project title «Educational and training support for PhD students and young researchers in preparation for insertion into the labor market».

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social-Political Sciences from "Al.I. Cuza" University of Iasi (Protocol code 97/01.02.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Informed consent was obtained from adults; for the minor participants in the study, legal consent was obtained from the legal guardians. The consent stated that the information could be used to publish scientific materials.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was co-funded by the European Social Fund, through Operational Programme Human Capital 2014-2020, project number POCU/993/6/13/153322, project title «Educational and training support for PhD students and young researchers in preparation for insertion into the labor market».

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Martela, F.; Steger, M.F. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology 2016, 11, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Kashdan, T.B. Purpose in Life as a System that Creates and Sustains Health and Well-Being: An Integrative, Testable Theory. Review of General Psychology 2009, 13, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Making Meaning in Life. Psychological Inquiry 2012, 23, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, K.; Burrow, A.L.; Burd, K.A.; Hill, P.L. On the conflation of purpose and meaning in life: A qualitative study of high school and college student conceptions. Applied Developmental Science 2021, 25, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.S.; Park, C.L. Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Review of General Psychology 2016, 20, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinzing, M. The meaning of "life’s meaning". Philosophers’ Imprint 220, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F. Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. In The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, US, 2012; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, M.J.; Baumeister, R.F. Meaning in Life: Nature, Needs, and Myths. In Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology; Batthyany A., Russo-Netzer P. (Eds.), Springer: New York, US, 2014; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A. The ’Long Winding Road’ to Adulthood: A Risk-filled Journey for Young People in Stockholm’s Marginalized Periphery. YOUNG 2011, 19, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk, K.C. The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: A grounded model. New Directions for Youth Development 2011, 132, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routledge, C. Supernatural: Death, meaning, and the power of the invisible world; Oxford University Press, U.S., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, A.J.; Chandler, G.E. Adolescent Resilience. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1999, 31, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M. Pathways to Resilience Among Children in Child Welfare, Corrections, Mental Health and Educational Settings: Navigation and Negotiation. Child and Youth Care Forum 2005, 34, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, P. A step-by-step guide to qualitative data coding; Routledge: New York, US, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers; Sage: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Analyzing qualitative data; Sage: Los Angeles, US, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Qualitative data analysis: A user-friendly guide for social scientists; Routledge: New York, US, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F. Sensuri ale vieții (Meanings of Life); ASCR Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy 1999, 21, pp–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.L.; Kreppner, J.M.; O’Connor, T.G. Specificity and heterogeneity in children’s responses to profound institutional privation. British Journal of Psychiatry 2001, 179, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, N.A.; Almas, A.N.; Degnan, K.A. , Nelson, C.A.; Zeanah, C.H. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at eight years of age: Findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project: Institutionalization, foster care and I.Q. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2011, 52, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, I.; Zanna, M.P.; Holmes, J.G.; Spencer, S. J. Compensatory conviction in the face of personal uncertainty: Going to extremes and being oneself. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2001, 80, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).