1. Introduction

Management of pulmonary dysfunction is one of the most prominent problems in medical practice [

1]. A global pandemic of the novel respiratory infection Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has contributed to the complexity of this problem tremendously [

2]. Although the acute phase is the most severe, the long-term consequences of this disease can persist and need to be addressed [

3,

4]. Most patients who developed COVID-19-induced pneumonia have bilateral lung lesions, respiratory failure, and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [

5] leading to significant changes in lung function, mostly restrictive, which can persist after recovery and are associated with an increased risk of life-threatening comorbidities [

6,

7]. Therefore, the development of rehabilitation methods to maintain adequate respiratory function are critical in this population [

8].

Currently, there are no effective therapeutic strategies to improve respiratory motor function after COVID-19 that are accepted as a standard of care. A fundamental reason for this is that the pathophysiological mechanisms of respiratory motor dysfunction after COVID-19 are not known. Although the primary pathogenic target is the respiratory system, a growing number of studies have reported central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19 [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Increasing reports have shown that COVID-19 infection affecting central and peripheral nervous systems by direct or indirect damage of neurons and respiratory neural networks may lead to long-term respiratory deficits [

15]. Respiratory neuroplasticity, defined as a persistent morphological and functional change in neural control based on behavioral experience, is critically dependent on the establishment of necessary preconditions, the stimulus paradigm, and a balance of complementary neuromodulation through hypoxia, hypercapnia, exercise, stress, and/or other factors [

16,

17,

18]. These speculations suggest that neuromodulation through spinal cord stimulation has potential for respiratory rehabilitation in this patient population. Recently, we reported that non-invasive spinal cord transcutaneous stimulation (scTS) may be a viable neuromodulatory approach to affect locomotor behavior [

19] and cardiovascular function [

20]. The results of these studies as well as our previous observations [

21,

22,

23] and the work of others [

24], led us to the idea that the activity of respiratory neural networks affected by COVID-19 can be neuromodulated by scTS with the goal to be utilized for respiratory rehabilitation. We hypothesized that scTS of respiratory neuronal networks results in increased spinal excitability leading to immediate increase in respiratory functional effectiveness. Here, for the first time, we propose that scTS configured for the activation of respiratory neuronal networks will result in increased respiratory functional performance in patients with post-acute COVID-19 respiratory deficits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pavlov’s Institute of Physiology, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation (protocol #20-02 dated December 18th, 2020) and was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation "On the activities of organizations subordinate to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the conditions of preventing the spread of the COVID-19 infection in the territory of the Russian Federation" (order #692 dated May 28th, 2020).

Data collection occurred between December 2020 and March 2022. Data sets were collected in a physiological laboratory environment during a single visit for each participant. The outcome measures were assessed prior to the intervention (“pre-Intervention” time point) and 15 minutes after the twenty-minute exposure (“post-Intervention” time point) to the simultaneous two-channel scTS applied over the T5 and T10 spinal cord segments. Eight healthy controls and ten post-acute COVID-19 participants have been recruited. Five female and five male COVID-19 participants 55 ± 13 years of age previously hospitalized with severe COVID-19 in association with pneumonia were recruited after 59 ± 48 days post-diagnosis (

Table 1). Prior to entering this study, all participants were PCR-tested negative for COVID-19. The following inclusion criteria were applied: at least 21 years of age; post-acute COVID-19 syndrome; no ventilatory dependence; respiratory functional deficit defined as a decrease in predicted FVC values at least 20%; no tobacco or drug use; and no cardiovascular or respiratory conditions unrelated to COVID-19. All individuals reported episodes of shortness of breath and fatigue at the time of the study. Besides experimental procedures, all participants maintained their normal daily routines. No participants withdrew from the study.

2.2. Research procedures

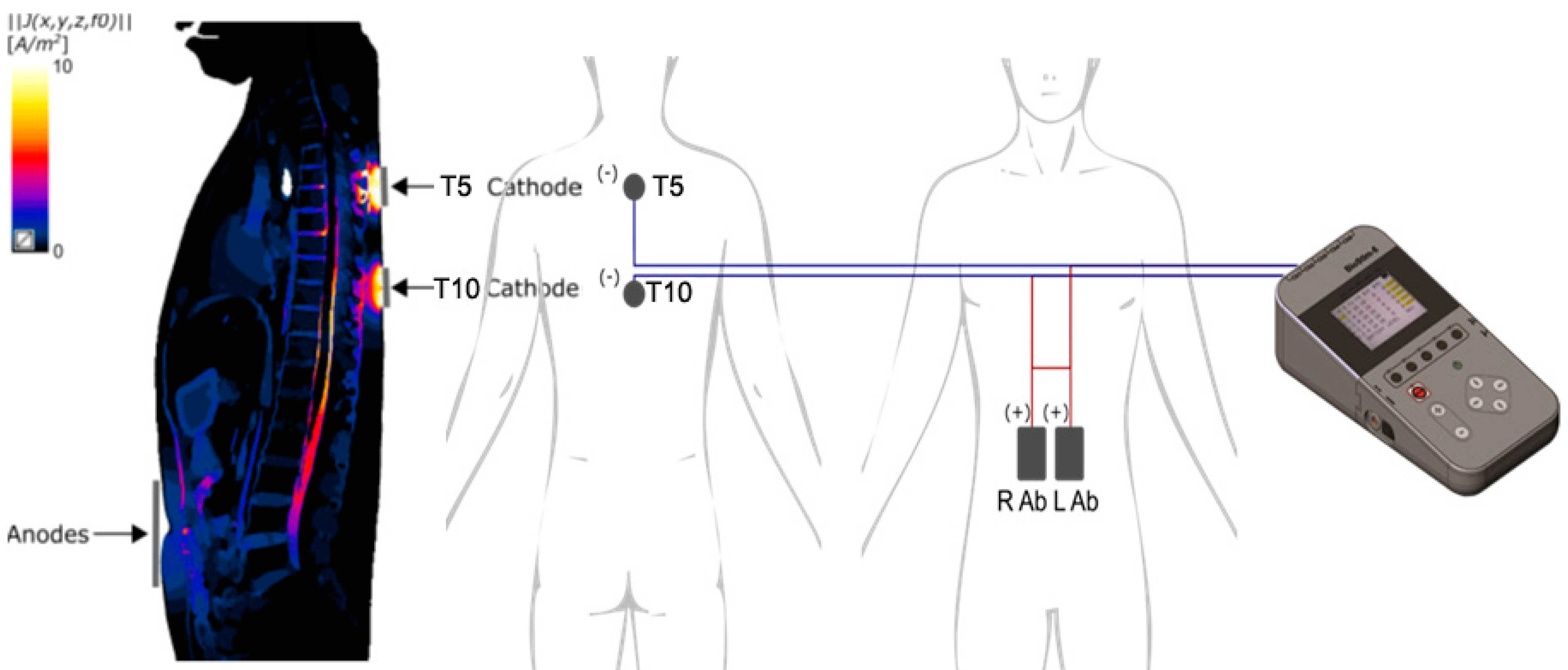

Multi-site scTS was delivered by a Biostim-5 device (Cosyma Inc., Denver, CO) over the midline between the third and fourth and between the eighth and nineth thoracic spinous processes (Th3-Th4 and Th8-Th9) corresponding to the T5 and T10 spinal cord segments via self-adhesive electrodes (cathodes) with a diameter of 32 mm (ValueTrode, Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., LTD, Fallbrook, CA) [

24]. Two 5×9 cm interconnected self-adhesive rectangular electrodes (ValueTrode, Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., LTD, Fallbrook, CA) served as anodes, were placed bilaterally along the rectus abdominus muscles centered at the umbilical level (

Figure 1). Stimulation consisted of 5 kHz-modulated, monophasic, 1-ms pulses delivered with a frequency of 30 Hz to activate dorsal roots as reported previously [

25], providing afferent input to the spinal cord segments involved in the activation of the accessory respiratory muscles. During the stimulation intensity mapping phase, starting at 10 mA, the current was gradually increased up to 40.1 ± 11.9 mA at Th3/Th4 and up to 40.3 ± 13.7 mA at Th8/Th9 until twitching of intercostal or abdominal muscles were noted indicating the motor threshold. For interventional stimulation, these values were decreased -10 mA to the sub-motor threshold levels. Brachial arterial blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation, and pain sensation using a visual analogue scale of pain (VASp) were monitored 20 min before, during, and 20 min after the intervention.

2.3. Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Respiratory function outcome measures: Forced Vital Capacity (FVC, L), Peak Forced Inspiratory Flow (PIF, L/min), Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF, L/min), Time-To-Peak of Inspiratory Flow (tPIF, sec), and Time-To-Peak of Expiratory Flow (tPEF, sec), were obtained from flow-volume curves recorded in the seated position during standard spirometry using a Powerlab 16/35 data acquisition system with Human Respiratory Kit (AD Instruments, Denver, CO) [

26].

Data values were analyzed in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and represented by descriptive statistics (Mean ± Standard Deviation). Pre- to post-intervention changes for each outcome measure were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and the Shapiro-Wilk tests. A paired t-test and Signed Rank test were used to assess normally and non-normally distributed outcomes, respectively. The statistical significance threshold was set to α = .05.

3. Results

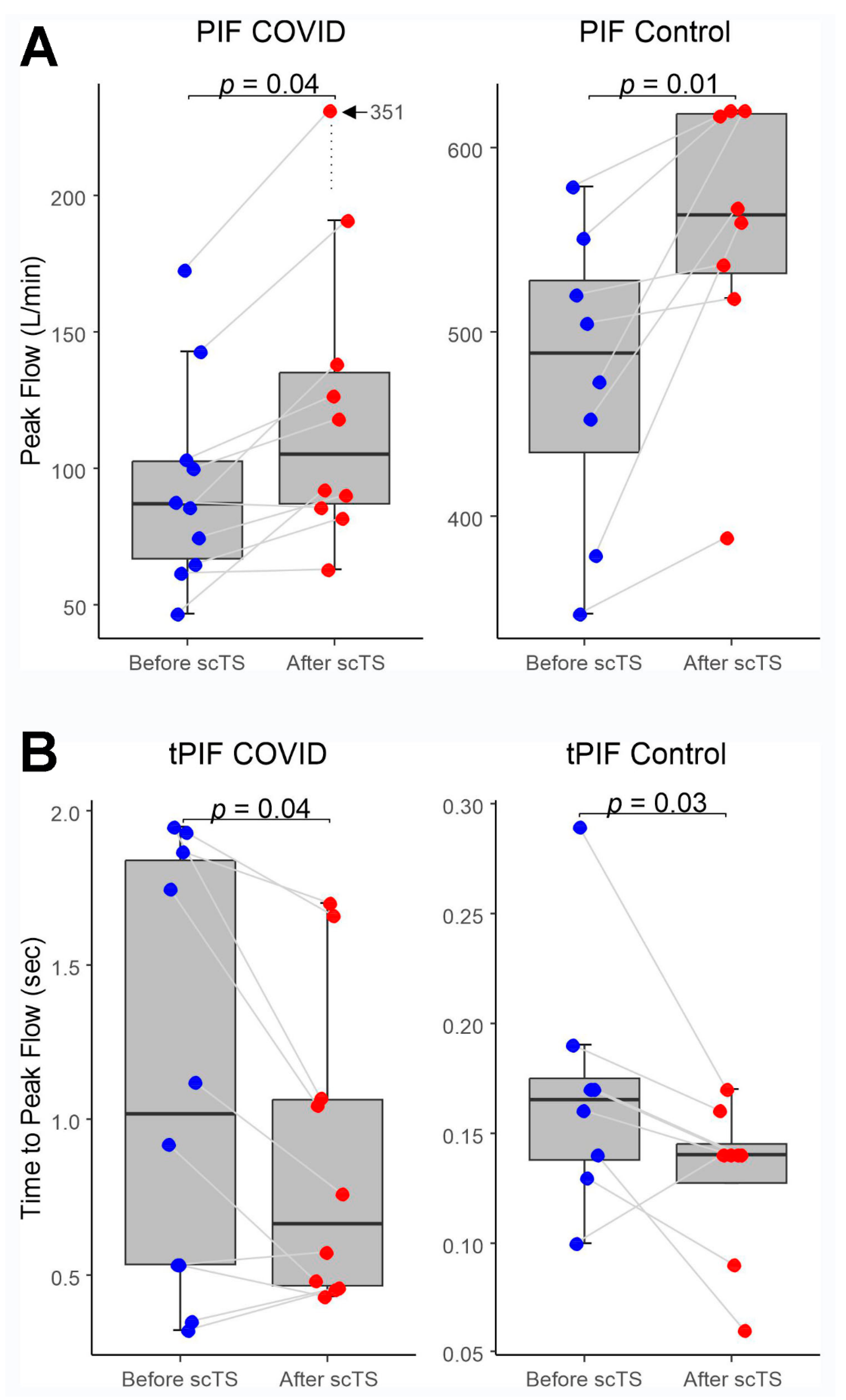

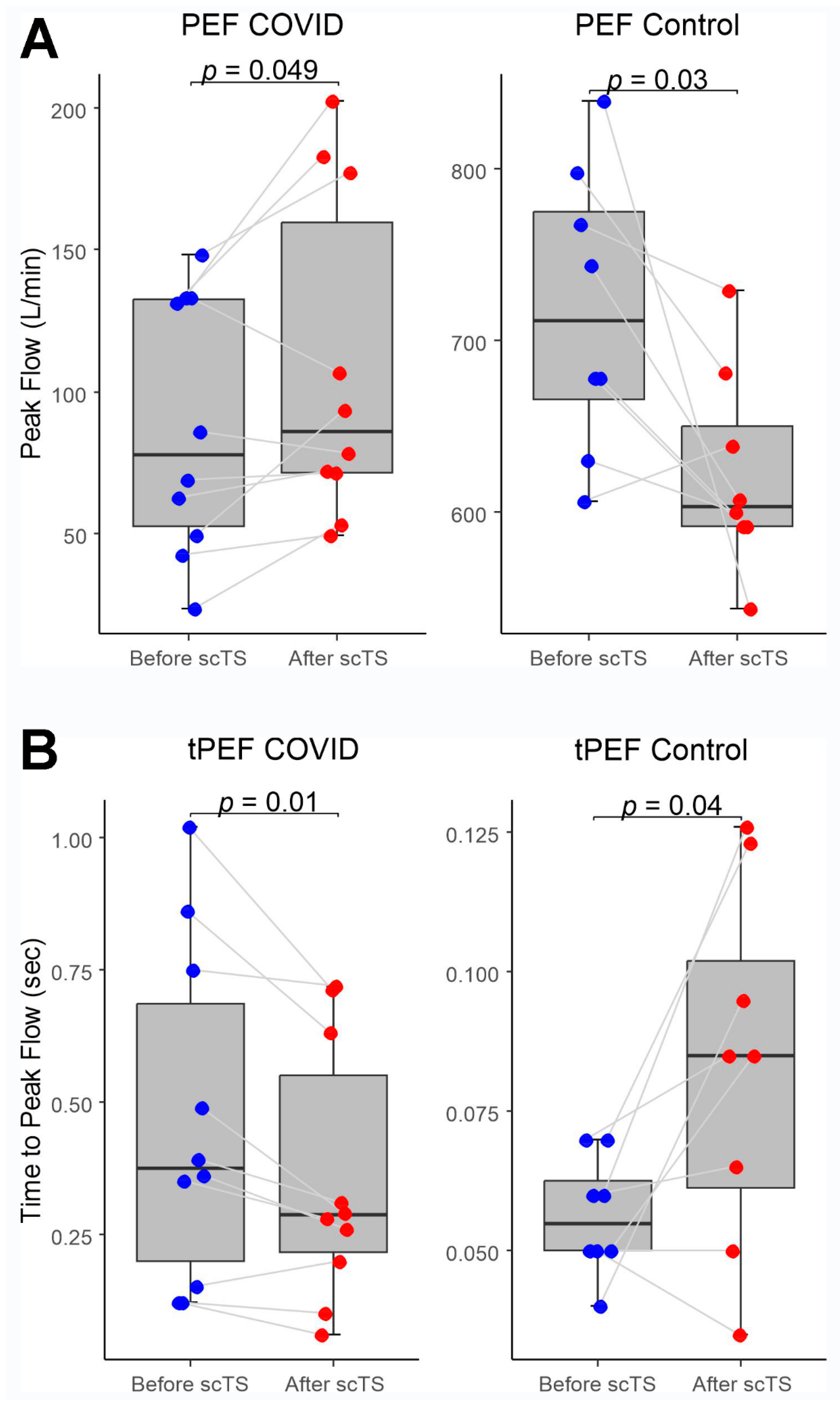

In the COVID-19 group, application of scTS led to significantly increased PIF (93.99 ± 38.26 vs. 133.67 ± 84.54 L/min, Mean ± SD; p= .040) and PEF (87.84 ± 45.05 vs 108.85 ± 57.31 L/min; p= .049) in association with significantly decreased tPIF (1.13 ± .69 vs .86 ± .49 sec; p= .035) and tPEF (.46 ± .32 vs .35 ± .24 sec; p= .013). In the Control group, exposure to the scTS resulted in significantly increased PIF (475.80 ± 80.79 vs. 553.76 ± 77.76 L/min, p= .010) and significantly decreased tPIF (.17 ± .06 vs .13 ± .04 sec; p= .031). In contrast to the results for the COVID group, there were significant decrease in PEF (717.75 ± 82.76 vs 622.76 ± 58.53 L/min; p= .028) in association with significantly increased tPEF (.06 ± .02 vs .08 ± .03 sec; p= .036) (

Figure 2 and

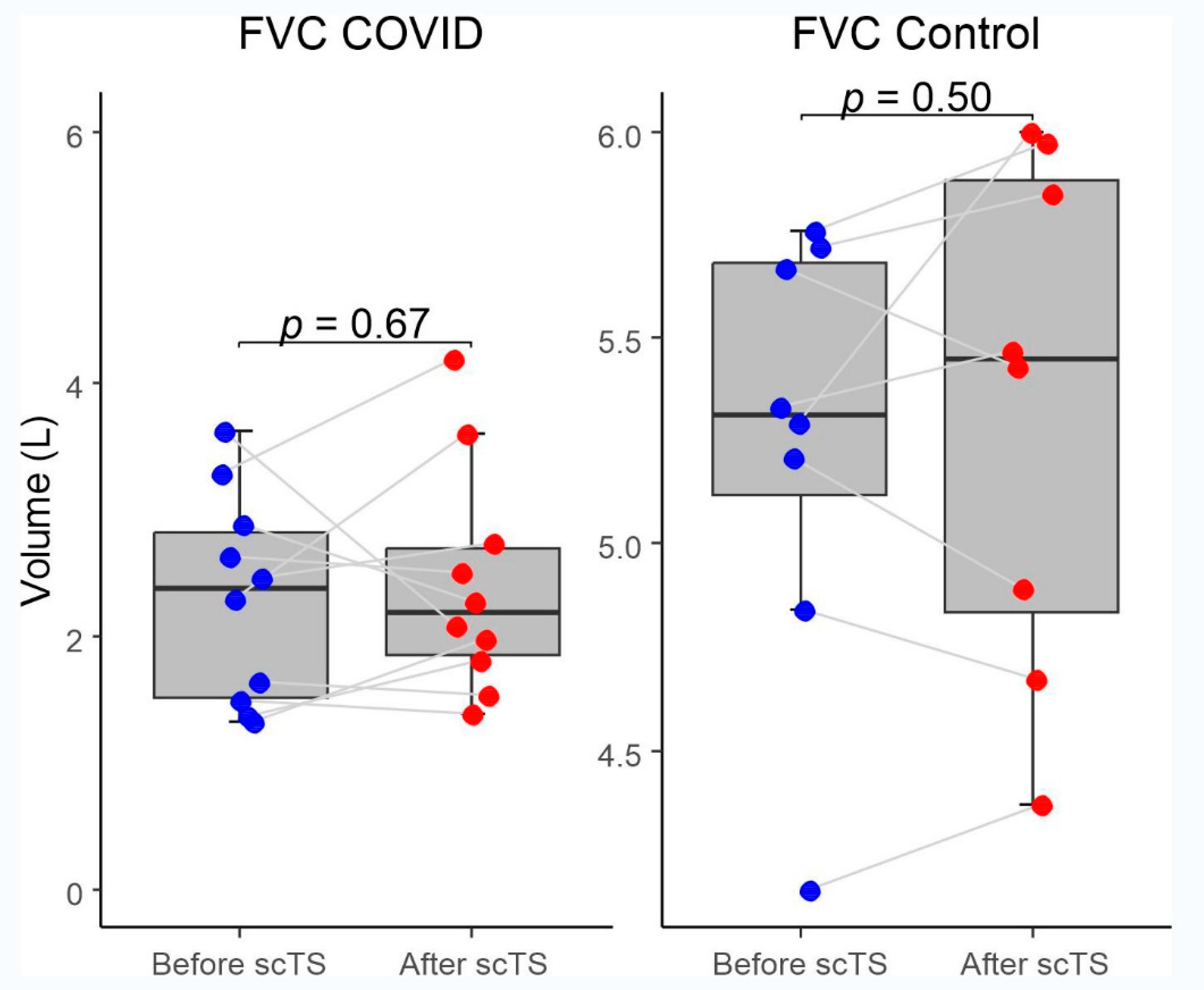

Figure 3). There were no changes for FVC after scTS in both groups (2.31 ± .83 vs 2.42 ± .89 L; p= .67 /COVID group/ and 5.25 ± .54 vs 5.33 ± .62 L; p= .503 /Control group/) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This is the first publication demonstrating the implementation of scTS as a neuromodulation technique in patients with COVID-19 respiratory deficits. The significant scTS-induced changes in PIF and PEF indicate increased respiratory neuromuscular network activity for both inspiration and expiration in individuals with post-COVID-19 respiratory deficits. In addition, a significant decrease in tPIF and tPEF in these patients indicates improved inter-neuronal activity of the respiratory networks. There were no changes for FVC after scTS in both groups indicating that pulmonary component was not affected by scTS. This report is aimed to present the initial finding regarding the potential of spinal neuromodulation in post-acute COVID-19 population using simple “pre-/post- acute effect” study design where baseline data sets served as self-controls in combination with evaluation of the healthy controls underwent the same intervention. The results of this study suggest that non-invasive scTS targeting respiratory neuronal networks [

27] can be a valuable element of a successful respiratory rehabilitation strategy for these patients.

In the present study, to affect the spinal structures responsible for accessory respiratory motor control [

28], scTS was delivered using two cathodes placed over the T5 and T10 spinal cord segments and two interconnected anodes positioned at the umbilical level. To exclude respiratory muscle contraction during the intervention, the intensity of scTS was maintained at a sub-motor threshold level. In addition, to exclude the direct effect of scTS, post-intervention testing was performed after a 15-min “wash out” period. Our group has pioneered the use of epidural spinal cord stimulation to activate spinal networks in patients with severe spinal cord injury [

29]. In individual with cervical motor-discomplete injury, we observed that intercostal muscles are activated when the respiratory effort was assisted by the epidural stimulation is applied at the lumbar segments [

30]. Recently, we demonstrated that a single twenty-minutes session of scTS exposure over the cervical spinal cord resulted in increased excitability of not only spinal but also cortical networks lasting for 75 min after cessation of stimulation [

31]. These findings suggest that scTS delivered to T5 and T10 spinal segments may also have a facilitatory effect on supraspinal respiratory structures and further contribute to the increased respiratory activity via descending pathways.

One might expect that scTS could also activate the autonomic network associated with innervation of the airways and subsequently increase lung capacity. Our results showed that FVC was not altered by stimulation. This finding indirectly indicates that there was no autonomic activation component of the intervention. Our previous work showed that scTS can induce autonomic activation in association with increase in BP in individuals with spinal cord injury-induced autonomic deficits [

19]. In the present study, we did not observe scTS-induced changes in BP. These effects might be linked to the different pathophysiological mechanisms of these two populations and specific parameters of scTS that were used in the two distinct protocols.

This study revealed that in healthy individuals the scTS differently affects inspiratory and expiratory motor networks. As well as in the COVID-19 group, in the control individuals we observed activation of inspiratory motor circuitry manifested by significantly increased PIF in association with significantly decreased tPIF, however, there were opposite effect on the expiratory circuitry: significant decrease in PEF accompanied by significantly increased tPEF which indicates suppression of expiratory neuromuscular activity. Observed for the first time, these phenomena indicate that intact spinal network uses self-regulatory mechanisms to mountain homeostasis.

The therapeutic potential of non-invasive spinal cord stimulation for patients with respiratory deficits has not yet been studied [

23]. Further research is needed to define specific pathophysiological mechanisms related to neural dysfunction in patients with COVID-19, which is a key element for the creation of appropriate rehabilitative strategies for this patient population. It should be noted that respiratory-related data from patients with COVID-19 are currently limited to a single randomized controlled study showing that 6-weeks of general respiratory rehabilitation can improve respiratory function, quality of life, and mental health of elderly patients [

32]. A study of respiratory function during clinical recovery and 6 weeks after discharge in COVID-19 -induced pneumonia survivors found that although pulmonary function had improved, some restrictive deficits persisted [

33]. Based on the results of our previous work [

34], we propose that combined with scTS, a specific use-dependent rehabilitative intervention in the form of respiratory training, could result in the enhanced plasticity of respiratory neuronal networks leading to the improved respiratory motor function needed to overcome the restrictive respiratory deficits developed in individuals with post-acute COVID-19.

Limitations

For the future full-scale clinical trials, matched control groups, including healthy controls, and/or experimental controls, and/or controls with non-specific scTS configuration, will be needed. In addition, based on our experience of using scTS for locomotor rehabilitation [

18,

31,

35], this initial scTS protocol for respiratory neuromodulation can be improved. For example, relocation or addition of the anodes to the anterior upper thoracic region might be more effective due to closer proximity to the cathodes. These questions should be addressed by investigating computational and functional effects of different scTS electrical parameters and electrode positioning.

5. Conclusions

A single session of scTS applied over the thoracic spinal cord in post-COVID-19 patients leads to improved respiratory functional performance via activation of the spinal neural networks. These findings indicate that a specifically configurated non-invasive spinal cord stimulation paradigm could be utilized for rehabilitation to reduce persistent respiratory motor deficits in patients recovering from COVID-19.

Author Contributions

A. Ovechkin and Y. Gerasimenko: study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing; T. Moshonkina, N. Shandybina, V. Lyakhovetskii, R. Gorodnichev, S. Moiseev, and R. Siu: data acquisition, processing, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation under the agreement # 075-15-2020-921 to support the development of a world-class research center “Pavlov Center for Integrative Physiology for Medicine, High-tech Healthcare, and Stress Tolerance Technologies” and supported by the National Institutes of Health R01NS102920 and R01HL168294 grants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pavlov’s Institute of Physiology, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation (protocol #20-02 dated December 18th, 2020) and was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation "On the activities of organizations subordinate to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the conditions of preventing the spread of the COVID-19 infection in the territory of the Russian Federation" (order #692 dated May 28th, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We express our appreciation to the research participants; to Natalia Krutikova and Ekaterina Dudnitskaya for the clinical support; and to Sofiia Kozyreva, Alexander Puhov, and Valeria Markevich for participation in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. Yury Gerasimenko holds shareholder interest in NeuroRecovery Technologies and Cosyma (producer of a Biostim-5 device used in this study). He holds certain inventorship rights on intellectual property licensed by the regents of the University of California to NeuroRecovery Technologies and its subsidiaries.

References

- W.W. Labaki, and M.K. Han, Chronic respiratory diseases: a global view. Lancet Respir Med 8 (2020) 531-533. [CrossRef]

- M. Pagnesi, M. Adamo, and M. Metra, 21 at a glance: focus on epidemiology, prevention and COVID-19. Eur J Heart Fail 23 (2021) 347-349. 20 March. [CrossRef]

- M. Polastri, M. Lazzeri, C. Jacome, M. Vitacca, S. Costi, E. Clini, and A. Marques, Rehabilitative practice in Europe: Roles and competencies of physiotherapists. Are we learning something new from COVID-19 pandemic? Pulmonology (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Nalbandian, K. Sehgal, A. Gupta, M.V. Madhavan, C. McGroder, J.S. Stevens, J.R. Cook, A.S. Nordvig, D. Shalev, T.S. Sehrawat, N. Ahluwalia, B. Bikdeli, D. Dietz, C. Der-Nigoghossian, N. Liyanage-Don, G.F. Rosner, E.J. Bernstein, S. Mohan, A.A. Beckley, D.S. Seres, T.K. Choueiri, N. Uriel, J.C. Ausiello, D. Accili, D.E. Freedberg, M. Baldwin, A. Schwartz, D. Brodie, C.K. Garcia, M.S.V. Elkind, J.M. Connors, J.P. Bilezikian, D.W. Landry, and E.Y. Wan, Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 27 (2021) 601-615. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhu, P. Ji, J. Pang, Z. Zhong, H. Li, C. He, J. Zhang, and C. Zhao, Clinical characteristics of 3062 COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. J Med Virol 92 (2020) 1902-1914. [CrossRef]

- A. Sanyaolu, C. Okorie, A. Marinkovic, R. Patidar, K. Younis, P. Desai, Z. Hosein, I. Padda, J. Mangat, and M. Altaf, Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med (2020) 1-8. [CrossRef]

- W.J. Guan, W.H. Liang, J.X. He, and N.S. Zhong, Cardiovascular comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. Eur Respir J 55 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Petraglia, M. Chiavilli, B. Zaccaria, M. Nora, P. Mammi, E. Ranza, A. Rampello, A. Marcato, F. Pessina, A. Salghetti, C. Costantino, A. Frizziero, P. Fanzaghi, S. Faverzani, O. Bergamini, S. Allegri, F. Roda, R. Brianti, and T.C. Rehabilitation Group, Rehabilitative treatment of patients with COVID-19 infection: the P.A.R.M.A. evidence based clinical practice protocol. Acta Biomed 91 (2020) e2020169. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, X. Xu, Z. Chen, J. Duan, K. Hashimoto, L. Yang, C. Liu, and C. Yang, Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun 87 (2020) 18-22. [CrossRef]

- S. Soltani, A. Tabibzadeh, A. Zakeri, A.M. Zakeri, T. Latifi, M. Shabani, A. Pouremamali, Y. Erfani, I. Pakzad, P. Malekifar, R. Valizadeh, M. Zandi, and R. Pakzad, COVID-19 associated central nervous system manifestations, mental and neurological symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Neurosci 32 (2021) 351-361. [CrossRef]

- D. Nuzzo, S. Vasto, L. Scalisi, S. Cottone, G. Cambula, M. Rizzo, D. Giacomazza, and P. Picone, Post-Acute COVID-19 Neurological Syndrome: A New Medical Challenge. J Clin Med 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. Nazari, A. Azari Jafari, S. Mirmoeeni, S. Sadeghian, M.E. Heidari, S. Sadeghian, F. Assarzadegan, S.M. Puormand, H. Ebadi, D. Fathi, and S. Dalvand, Central nervous system manifestations in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav 11 (2021) e02025. [CrossRef]

- Y.C. Li, W.Z. Bai, and T. Hashikawa, The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 92 (2020) 552-555. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Asadi-Pooya, and L. Simani, Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review. J Neurol Sci 413 (2020) 116832. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang, R.M. F. Wang, R.M. Kream, and G.B. Stefano, Long-Term Respiratory and Neurological Sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit 26 (2020) e928996. [CrossRef]

- G.S. Mitchell, and S.M. Johnson, Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J Appl Physiol 94 (2003) 358-74. [CrossRef]

- G.C. Sieck, and C.B. Mantilla, Foreword to special issue: spinal cord injury-neuroplasticity and recovery of respiratory function. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology 169 (2009) 83-4. [CrossRef]

- A. Tadjalli, and J. Peever, Role of neurotrophic signaling pathways in regulating respiratory motor plasticity. adv exp med biol 669 (2010) 293-6. [CrossRef]

- T. Moshonkina, A. Grishin, I. Bogacheva, R. Gorodnichev, A. Ovechkin, R. Siu, V.R. Edgerton, and Y. Gerasimenko, Novel Non-invasive Strategy for Spinal Neuromodulation to Control Human Locomotion. Front Hum Neurosci 14 (2021) 622533. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Phillips, J.W. Squair, D.G. Sayenko, V.R. Edgerton, Y. Gerasimenko, and A.V. Krassioukov, An Autonomic Neuroprosthesis: Noninvasive Electrical Spinal Cord Stimulation Restores Autonomic Cardiovascular Function in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 35 (2018) 446-451. [CrossRef]

- A. Minyaeva, S. Moiseev, A. Pukhov, N. Shcherbakova, Y. Gerasimenko, and T. Moshonkina, Dependence of Respiratory Reaction on the Intensity of Locomotor Response to Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation of the Spinal Cord. Human Physiology 45 (2019) 262-270. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Minyaeva, S.A. Moiseev, A.M. Pukhov, A.A. Savokhin, Y.P. Gerasimenko, and T.R. Moshonkina, Response of external inspiration to the movements induced by transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation. Human Physiology 43 (2017) 524-531. [CrossRef]

- Y.P. Gerasimenko, D.C. Lu, M. Modaber, S. Zdunowski, P. Gad, D.G. Sayenko, E. Morikawa, P. Haakana, A.R. Ferguson, R.R. Roy, and V.R. Edgerton, Noninvasive Reactivation of Motor Descending Control after Paralysis. J Neurotrauma 32 (2015) 1968-80. [CrossRef]

- J.T. Hachmann, P.J. Grahn, J.S. Calvert, D.I. Drubach, K.H. Lee, and I.A. Lavrov, Electrical Neuromodulation of the Respiratory System After Spinal Cord Injury. Mayo Clin Proc 92 (2017) 1401-1414. [CrossRef]

- A. Mendez, R. Islam, T. Latypov, P. Basa, O.J. Joseph, B. Knudsen, A.M. Siddiqui, P. Summer, L.J. Staehnke, P.J. Grahn, N. Lachman, A.J. Windebank, and I.A. Lavrov, Segment-Specific Orientation of the Dorsal and Ventral Roots for Precise Therapeutic Targeting of Human Spinal Cord. Mayo Clin Proc 96 (2021) 1426-1437. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Grishin, T.R. Moshonkina, I.A. Solopova, R.M. Gorodnichev, and Y.P. Gerasimenko, A Five-Channel Noninvasive Electrical Stimulator of the Spinal Cord for Rehabilitation of Patients with Severe Motor Disorders. Biomedical Engineering 50 (2017) 300-304. [CrossRef]

- B.L. Graham, I. Steenbruggen, M.R. Miller, I.Z. Barjaktarevic, B.G. Cooper, G.L. Hall, T.S. Hallstrand, D.A. Kaminsky, K. McCarthy, M.C. McCormack, C.E. Oropez, M. Rosenfeld, S. Stanojevic, M.P. Swanney, and B.R. Thompson, Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200 (2019) e70-e88. [CrossRef]

- D.G. Terson de Paleville, W.B. McKay, R.J. Folz, and A.V. Ovechkin, Respiratory motor control disrupted by spinal cord injury: mechanisms, evaluation, and restoration. Transl Stroke Res 2 (2011) 463-73. [CrossRef]

- K. Ikeda, K. Kawakami, H. Onimaru, Y. Okada, S. Yokota, N. Koshiya, Y. Oku, M. Iizuka, and H. Koizumi, The respiratory control mechanisms in the brainstem and spinal cord: integrative views of the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. The journal of physiological sciences : JPS 67 (2017) 45-62. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gerasimenko, R.R. Roy, and V.R. Edgerton, Epidural stimulation: comparison of the spinal circuits that generate and control locomotion in rats, cats and humans. Exp.Neurol. 209 (2008) 417-425. [CrossRef]

- S. Harkema, Y. Gerasimenko, J. Hodes, J. Burdick, C. Angeli, Y. Chen, C. Ferreira, A. Willhite, E. Rejc, R.G. Grossman, and V.R. Edgerton, Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet 377 (2011) 1938-47. [CrossRef]

- F.D. Benavides, H.J. Jo, H. Lundell, V.R. Edgerton, Y. Gerasimenko, and M.A. Perez, Cortical and Subcortical Effects of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation in Humans with Tetraplegia. J Neurosci 40 (2020) 2633-2643. [CrossRef]

- K. Liu, W. Zhang, Y. Yang, J. Zhang, Y. Li, and Y. Chen, Respiratory rehabilitation in elderly patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 39 (2020) 101166. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Salem, N. Al Khathlan, A.F. Alharbi, T. Alghamdi, S. AlDuilej, M. Alghamdi, M. Alfudhaili, A. Alsunni, T. Yar, R. Latif, N. Rafique, L. Al Asoom, and H. Sabit, The Long-Term Impact of COVID-19 Pneumonia on the Pulmonary Function of Survivors. International journal of general medicine 14 (2021) 3271-3280. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Ovechkin, D.G. Sayenko, E.N. Ovechkina, S.C. Aslan, T. Pitts, and R.J. Folz, Respiratory motor training and neuromuscular plasticity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A pilot study. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 229 (2016) 59-64. [CrossRef]

- M. Rath, A.H. Vette, S. Ramasubramaniam, K. Li, J. Burdick, V.R. Edgerton, Y.P. Gerasimenko, and D.G. Sayenko, Trunk Stability Enabled by Noninvasive Spinal Electrical Stimulation after Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma (2018). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).