Submitted:

19 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. PRP and its cytokine constituents

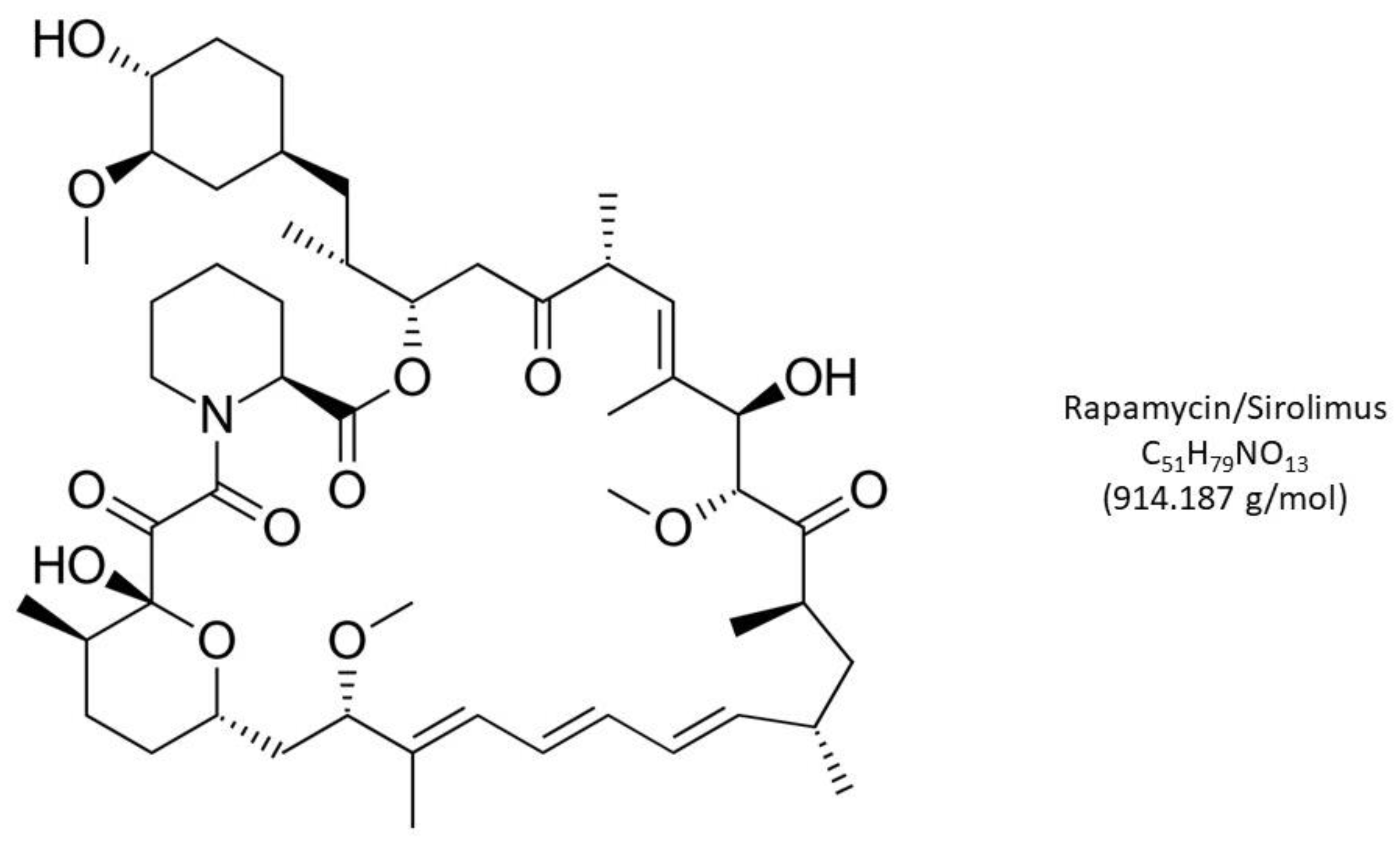

3. Rapamycin, mTOR, and reproductive biology

4. PLT cytokine augmentation by rapamycin?

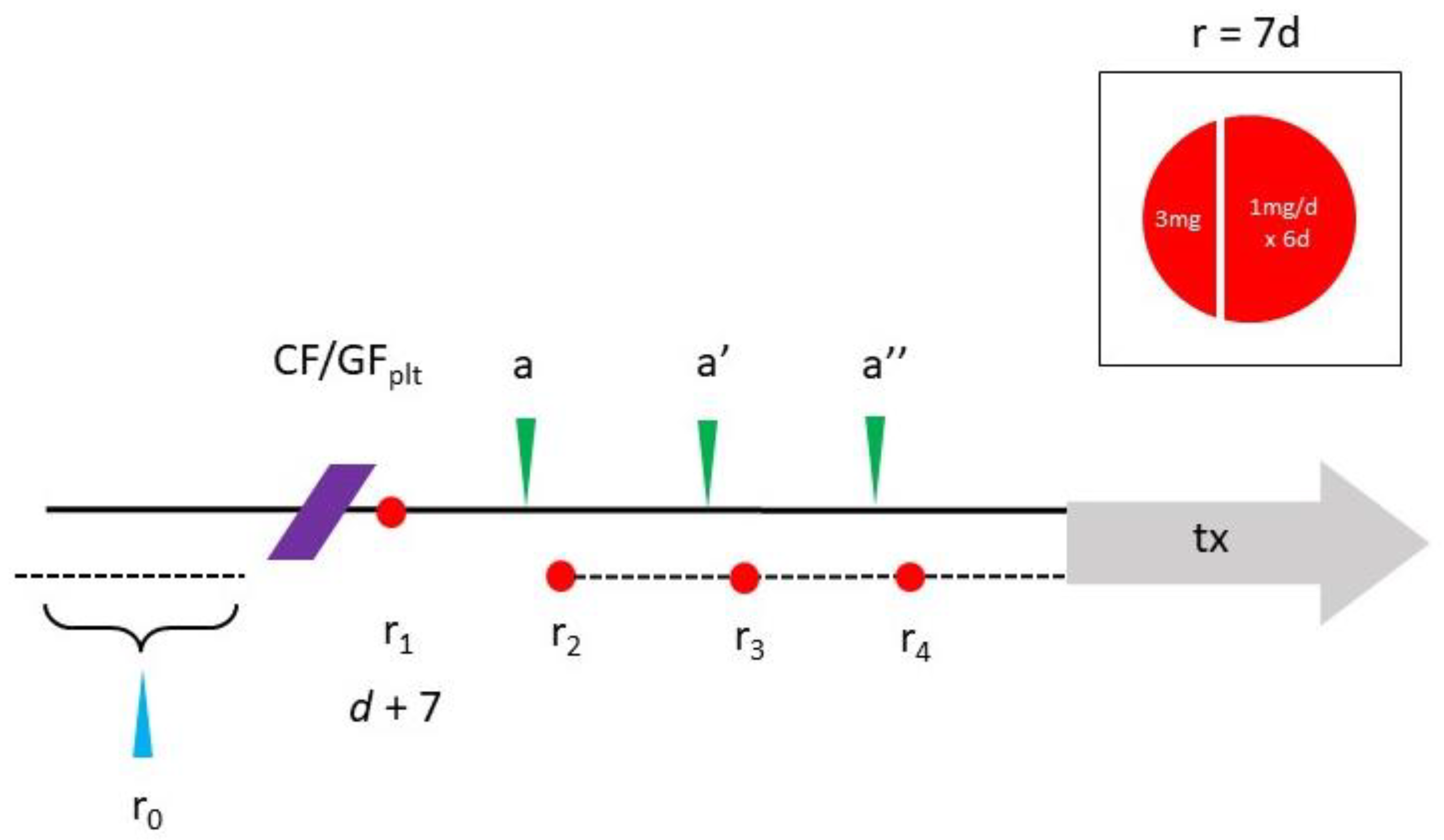

5. Rapamycin—Scheduling & toxicity issues

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kallen A, Polotsky AJ, Johnson J. Untapped reserves: Controlling primordial follicle growth activation. Trends Mol Med 2018;24(3):319-31. [CrossRef]

- Ford EA, Beckett EL, Roman SD, McLaughlin EA, Sutherland JM. Advances in human primordial follicle activation and premature ovarian insufficiency. Reproduction 2020;159(1):R15-29. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha D, La X, Feng HL. Comparison of different stimulation protocols used in in vitro fertilization: A review. Ann Transl Med 2015;3(10):137. [CrossRef]

- Mehta BN, Chimote NM, Chimote MN, Chimote NN, Nath NM. Follicular fluid insulin like growth factor-1 (FF IGF-1) is a biochemical marker of embryo quality and implantation rates in in vitro fertilization cycles. J Hum Reprod Sci 2013;6(2):140-6. [CrossRef]

- Ji Z, Quan X, Lan Y, Zhao M, Tian X, Yang X. Gonadotropin vs. follicle-stimulating hormone for ovarian response in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization: A retrospective cohort comparison. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2019;92:100572. [CrossRef]

- Banu J, Tarique M, Jahan N, Lasker N, Sultana N, Alamgir CF, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma for ovarian rejuvenation in infertile women having poor ovarian reserve. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2022;11:2948-53. [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu Y, Yuceturk A, Karaosmanoglu O, Kopuk SY, Korun ZEU, Herlihy N, et al. Ovarian reserve parameters and IVF outcomes in 510 women with poor ovarian response (POR) treated with intraovarian injection of autologous platelet rich plasma. Aging (Albany NY) 2022;14(6):2513-23. [CrossRef]

- Herlihy NS, Seli E. The use of intraovarian injection of autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP) in patients with poor ovarian response and premature ovarian insufficiency. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2022;34(3):133-7. [CrossRef]

- Grosbois J, Demeestere I. Dynamics of PI3K and Hippo signaling pathways during in vitro human follicle activation. Hum Reprod 2018;33(9):1705-14. [CrossRef]

- Gareis NC, Huber E, Hein GJ, Rodríguez FM, Salvetti NR, Angeli E, et al. Impaired insulin signaling pathways affect ovarian steroidogenesis in cows with COD. Anim Reprod Sci 2020;192:298-312. [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou K, Mastora E, Zikopoulos A, Grigoriou ME, Georgiou I, Michaelidis TM. Interplay between mTOR and Hippo signaling in the ovary: Clinical choice guidance between different gonadotropin preparations for better IVF. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:702446. [CrossRef]

- Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV, Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2009;8(12):1888-95. [CrossRef]

- Hambright WS, Philippon MJ, Huard J. Rapamycin for aging stem cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(15):15184-5. [CrossRef]

- Shindyapina AV, Cho Y, Kaya A, Tyshkovskiy A, Castro JP, Deik A, et al. Rapamycin treatment during development extends life span and health span of male mice and Daphnia magna. Sci Adv 2022;8(37):eabo5482. [CrossRef]

- Smits MAJ, Janssens GE, Goddijn M, Hamer G, Houtkooper RH, Mastenbroek S. Longevity pathways are associated with human ovarian ageing. Hum Reprod Open 2021;2021(2):hoab020. [CrossRef]

- Rosenwaks Z, Veeck LL, Liu HC. Pregnancy following transfer of in vitro fertilized donated oocytes. Fertil Steril 1986;45(3):417-20. [CrossRef]

- Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem AC. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet 1992;340(8810):17-8. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006;126(4):663-76. [CrossRef]

- Khadivi F, Koruji M, Akbari M, Jabari A, Talebi A, Ashouri Movassagh S, et al. Application of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) improves self-renewal of human spermatogonial stem cells in two-dimensional and three-dimensional culture systems. Acta Histochem 2020;122(8):151627. [CrossRef]

- Parte S, Bhartiya D, Telang J, Daithankar V, Salvi V, Zaveri K, et al. Detection, characterization, and spontaneous differentiation in vitro of very small embryonic-like putative stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. Stem Cells Dev 2011;20(8):1451-64. [CrossRef]

- Bhartiya D, Singh P, Sharma D, Kaushik A. Very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) regenerate whereas mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) rejuvenate diseased reproductive tissues. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2022;18(5):1718-27. [CrossRef]

- Virant-Klun I, Skutella T. Stem cells in aged mammalian ovaries. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2(1):3-6. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Lu Z, Zhu Q, Ma L, Xue L, Li Y, et al. DDX04+ stem cells in the ovaries of postmenopausal women: Existence and differentiation potential. Stem Cells 2022;40(1):88-101. [CrossRef]

- Woods DC, Tilly JL. Revisiting claims of the continued absence of functional germline stem cells in adult ovaries. Stem Cells 2023;41(2):200-4. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Y, Peng X, Peng Y, Zhang C, Liu W, Yang W, et al. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles regulate follicular activation and improve ovarian function in old mice by modulating local environment. Clin Transl Med 2022;12(10):e1071. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Guilloty F, Saeed AM, Echegaray JJ, Duffort S, Ballmick A, Tan Y, et al. Infiltration of proinflammatory M1 macrophages into the outer retina precedes damage in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Int J Inflam 2013;2013:503725. [CrossRef]

- Peltier J, O'Neill A, Schaffer DV. PI3K/Akt and CREB regulate adult neural hippocampal progenitor proliferation and differentiation. Dev Neurobiol 2007;67(10):1348-61. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda L, Gao J, Hooten KG, Wang E, Thonhoff JR, Dunn TJ, et al. Critical role of PI3K/Akt/GSK3β in motoneuron specification from human neural stem cells in response to FGF2 and EGF. PLoS One 2011;6(8):e23414. [CrossRef]

- Marck RE, Gardien KLM, Vlig M, Breederveld RS, Middelkoop E. Growth factor quantification of platelet-rich plasma in burn patients compared to matched healthy volunteers. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20(2):288. [CrossRef]

- Pantos K, Nitsos N, Kokkali G, Vaxevanoglou T, Markomichali C, Pantou A, et al. Ovarian rejuvenation and folliculogenesis reactivation in peri-menopausal women after autologous platelet-rich plasma treatment (abstract) ESHRE 32nd Annual Meeting [Helsinki] 3-6 July, 2016. Hum Reprod 2016:i301. https://sa1s3.patientpop.com/assets/docs/111052.pdf.

- Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:721-6. [CrossRef]

- Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blenis J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70kd S6 protein kinases. Cell 1992;69:1227-36. [CrossRef]

- Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 1991;253(5022):905-9. [CrossRef]

- Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: A mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell 1994;78: 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 2017;168(6):960-76. [CrossRef]

- Śledź KM, Moore SF, Durrant TN, Blair TA, Hunter RW, Hers I. Rapamycin restrains platelet procoagulant responses via FKBP-mediated protection of mitochondrial integrity. Biochem Pharmacol 2020;177:113975. [CrossRef]

- Meng D, Frank AR, Jewell JL. mTOR signaling in stem and progenitor cells. Development 2018;145(1):dev152595. [CrossRef]

- Murakami M, Ichisaka T, Maeda M, Oshiro N, Hara K, Edenhofer F, et al. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24(15):6710-8. [CrossRef]

- Alhasan BA, Gordeev SA, Knyazeva AR, Aleksandrova KV, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV, et al. The mTOR pathway in pluripotent stem cells: Lessons for understanding cancer cell dormancy. Membranes (Basel) 2021;11(11):858. [CrossRef]

- Garbern JC, Helman A, Sereda R, Sarikhani M, Ahmed A, Escalante GO, et al. Inhibition of mTOR signaling enhances maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells via p53-induced quiescence. Circulation 2020;141(4):285-300. [CrossRef]

- Takayama K, Kawakami Y, Lavasani M, Mu X, Cummins JH, Yurube T, et al. mTOR signaling plays a critical role in the defects observed in muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells isolated from a murine model of accelerated aging. J Orthop Res 2017;35(7):1375-82. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoli D, Boulay K, Kazak L, Pollak M, Mallette F, Topisirovic I, et al. mTOR as a central regulator of lifespan and aging. F1000Res 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-998. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami Y, Hambright WS, Takayama K, Mu X, Lu A, Cummins JH, et al. Rapamycin rescues age-related changes in muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells from progeroid mice. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;14:64-76. [CrossRef]

- Tian D, Zeng X, Wang W, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Protective effect of rapamycin on endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in HUVECs through the Notch signaling pathway. Vascul Pharmacol 2019;113:20-6. [CrossRef]

- Gordon LB, Norris W, Hamren S, Goodson R, LeClair J, Massaro J, et al. Plasma progerin in patients with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: Immunoassay development and clinical evaluation. Circulation 2023: in press. [CrossRef]

- Mosevitsky, MI. Progerin and Its role in accelerated and natural aging. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2022;56(2):181-205. [CrossRef]

- Neupane B, Pradhan K, Ortega-Ramirez AM, Aidery P, Kucikas V, Marks M, et al. Personalized medicine approach in a DCM patient with LMNA mutation reveals dysregulation of mTOR signaling. J Pers Med 2022;12(7):1149. [CrossRef]

- Palozzi JM, Hurd TR. The role of programmed mitophagy in germline mitochondrial DNA quality control. Autophagy 2023:1-2. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang Y, Kim E, Beemiller P, Wang CY, Swanson J, et al. Bnip3 mediates the hypoxia-induced inhibition on mammalian target of rapamycin by interacting with Rheb. J Biol Chem 2007;282(49):35803-13. [CrossRef]

- Bar DZ, Charar C, Dorfman J, Yadid T, Tafforeau L, Lafontaine DL, et al. Cell size and fat content of dietary-restricted Caenorhabditis elegans are regulated by ATX-2, an mTOR repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113(32):E4620-9. [CrossRef]

- Silva E, Rosario FJ, Powell TL, Jansson T. Mechanistic target of rapamycin is a novel molecular mechanism linking folate availability and cell function. J Nutr 2017;147(7):1237-42. [CrossRef]

- Park HJ, Heo GD, Yang SG, Koo DB. Rapamycin encourages the maintenance of mitochondrial dynamic balance and mitophagy activity for improving developmental competence of blastocysts in porcine embryos in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev 2023: in press. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Xi Q, Wang M, Liu J, Li Z, Hu J, Jin L, Zhu L. Rapamycin improves the developmental competence of human oocytes by alleviating DNA damage during IVM. Hum Reprod Open 2022;2022(4):hoac050. [CrossRef]

- Allan, S. Seeing mTOR in a new light. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:904. [CrossRef]

- Sills ES, Wood SH. Epigenetics, ovarian cell plasticity, and platelet-rich plasma: Mechanistic theories. Reprod Fertil 2022;3(4):C44-C51. [CrossRef]

- Bae IH, Lim KS, Park DS, Shim JW, Lee SY, Jang EJ, et al. Sirolimus coating on heparinized stents prevents restenosis and thrombosis. J Biomater Appl 2017;31(10):1337-45. [CrossRef]

- Babinska A, Markell MS, Salifu MO, Akoad M, Ehrlich YH, Kornecki E. Enhancement of human platelet aggregation and secretion induced by rapamycin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13(12):3153-9. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Huang KS, Chen M, Huang DJ. Rapamycin enhances platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate in vitro. Platelets 2009;20(6):428-31. [CrossRef]

- López E, Berna-Erro A, Bermejo N, Brull JM, Martinez R, Garcia Pino G, et al. Long-term mTOR inhibitors administration evokes altered calcium homeostasis and platelet dysfunction in kidney transplant patients. J Cell Mol Med 2013;17(5):636-47. [CrossRef]

- Sills ES, Rickers NS, Svid CS, Rickers JM, Wood SH. Normalized ploidy following 20 consecutive blastocysts with chromosomal error: Healthy 46, XY pregnancy with IVF after intraovarian injection of autologous enriched platelet-derived growth factors. Int J Mol Cell Med 2019;8(1):84-90. [CrossRef]

- Goldman KN, Chenette D, Arju R, Duncan FE, Keefe DL, Grifo JA, et al. mTORC1/2 inhibition preserves ovarian function and fertility during genotoxic chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017;114(12):3186-91. [CrossRef]

- Escobar KA, Cole NH, Mermier CM, VanDusseldorp TA. Autophagy and aging: Maintaining the proteome through exercise and caloric restriction. Aging Cell 2019;18(1):e12876. [CrossRef]

- Lamming DW, Ye L, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors as anti-aging therapeutics. J Clin Invest 2013;123(3):980-9. [CrossRef]

- Mannick JB, Del Giudice G, Lattanzi M, Valiante NM, Praestgaard J, Huang B, et al. mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(268):268ra179. [CrossRef]

- Ceschi A, Heistermann E, Gros S, Reichert C, Kupferschmidt H, Banner NR, et al. Acute sirolimus overdose: A multicenter case series. PLoS One 2015;10(5):e0128033. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, MV. Rapamycin for longevity: Opinion article. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(19):8048-67. [CrossRef]

- Foster DA, Toschi A. Targeting mTOR with rapamycin: One dose does not fit all. Cell Cycle 2009;8(7):1026-9. [CrossRef]

- Sills ES, Wood SH, Walsh APH. Intraovarian condensed platelet cytokines for infertility and menopause-Mirage or miracle? Biochimie 2023;204:41-7. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy BK, Lamming DW. The mechanistic target of rapamycin: The grand conducTOR of metabolism and aging. Cell Metab 2016;23(6):990-1003. [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic Health Information (Drugs & Supplements) – Sirolimus DRG-20068199. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education & Research, 1 March 2023 https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sirolimus-oral-route/proper-use/drg-20068199 [accessed 15 May 2023].

- U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://clinicaltrials.gov [accessed ]. 15 May.

- Sills ES, Wood SH. Progress in human ovarian rejuvenation: Current platelet-rich plasma and condensed cytokine research activity by scope and international origin. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2021;48(4):311-5. [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M. Rapamycin and ageing: When, for how long, and how much? J Genet Genomics 2014;41(9):459-63. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, MV. Fasting and rapamycin: Diabetes versus benevolent glucose intolerance. Cell Death Dis 2019;10(8):607. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson L, Martin F, Sturmey RG. Intraovarian injection of platelet-rich plasma in assisted reproduction: Too much too soon? Hum Reprod 2021;36(7):1737-50. [CrossRef]

- Sills, ES. Ovarian recovery via autologous platelet-rich plasma: New benchmarks for condensed cytokine applications to reverse reproductive aging. Aging Med (Milton) 2022;5(1):63-7. [CrossRef]

- Garavelas A, Mallis P, Michalopoulos E, Nikitos E. Clinical benefit of autologous platelet-rich plasma infusion in ovarian function rejuvenation: Evidence from a before-after prospective pilot study. Medicines (Basel) 2023;10(3):19. [CrossRef]

- Papapanou M, Syristatidi K, Gazouli M, Eleftheriades M, Vlahos N, Siristatidis C. The effect of stimulation protocols (GnRH agonist vs. antagonist) on the activity of mTOR and Hippo pathways of ovarian granulosa cells and its potential correlation with the outcomes of in vitro fertilization: A hypothesis. J Clin Med 2022;11(20):6131. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).