1. Introduction

Urban water infrastructure (UWI) comprises three primary components, i.e., water distribution systems (WDS), drainage/stormwater systems and wastewater systems. These components are essential for delivering clean water to customers, collecting surface runoff from urban areas and sanitary sewage from households in cities. While providing these essential services, these systems also offer opportunities to implement strategies that can enhance urban resilience. However, these systems face various challenges and stresses that can result in technical failures or performance losses, leading to exorbitant costs (World bank, 2020). Some of these challenges include ageing infrastructure and insufficient investment in infrastructure rehabilitation, which can reduce system capacity, population growth and rapid urbanisation that increase system loads, inadequate water infrastructure maintenance, climate change, and extreme weather events such as flooding and drought. Addressing these challenges is crucial for maintaining the functionality of UWI and avoiding costly disruptions (Pamidimukkala et al., 2021; Piadeh et al., 2022a).

To address the challenges and stresses faced by UWI, it is crucial to establish a robust and resilient system that can withstand significant disruptions, dynamically reorganise itself, and continue to perform essential functions without any interruptions (Duin et al., 2021). This resilience can be achieved through various measures such as incorporating redundant capacity in the infrastructure, adopting flexible design principles, implementing advanced monitoring and control systems, and promoting community engagement and awareness. By constructing a more resilient UWI and ensuring that residents have access to clean water, cities can better withstand the challenges and stresses they face (Leigh and Lee, 2019).

Resilience in urban infrastructure is defined by its ability to maintain essential functions while adapting to external changes, promoting sustainability. Extensive research has been conducted in recent years to understand, analyse and enhance resilience in urban infrastructure including the development of resilient systems and the measurement of experimental resilience, and improvements to various resilience infrastructure to overcome uncertainty related to future drivers (García et al., 2017; Momeni et al., 2021).

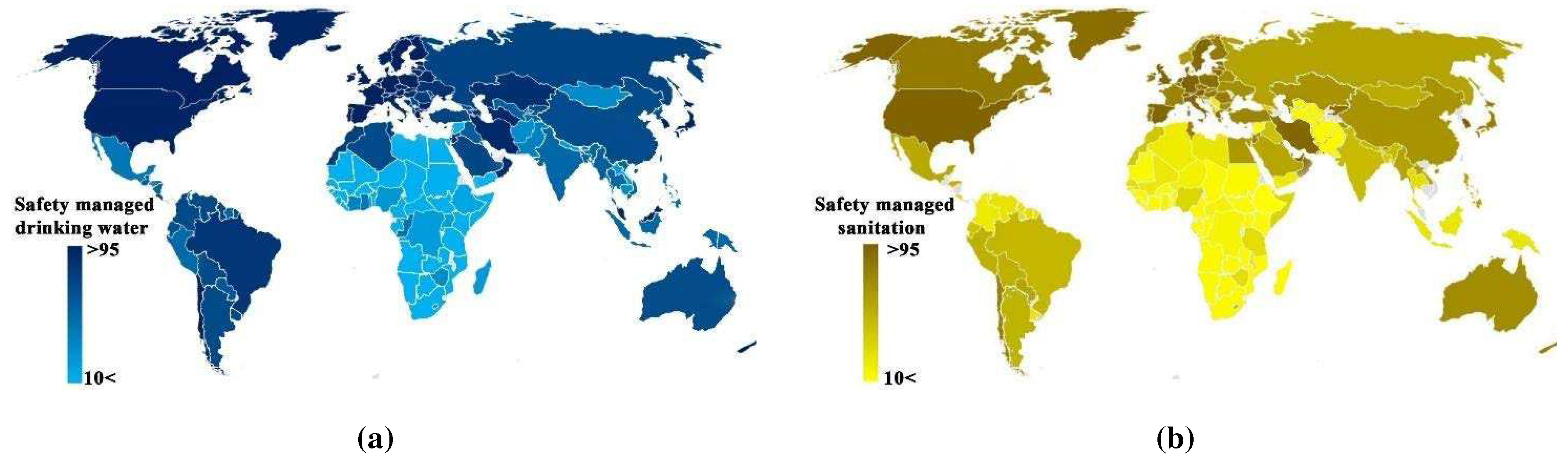

However, measuring global resilience is challenging and requires the use of multiple indicators and metrics. Some common metrics used to measure resilience in UWI include the availability of clean and safe drinking water, the efficiency and reliability of sewage collection systems, and the implementation of United Nations safety management facilities (UN-Water, 2022) as shown in

Figure 1. There are significant differences in the level of investment given to the main components of UWI across the world. Although access to drinking water has improved in the Middle East, water recycling in urban water systems requires more investment. African countries suffer greatly from a lack of investment in both access to drinking water and proper collection of stormwater and wastewater. Furthermore, unequal investments in UWI components can have severe consequences, not only for UWI resilience but also for the health and well-being of society. In addition, the currently employed to measure resilience may not accurately reflect the intricacies and complexities of UWI services and performance. This is partly due to the absence of globally recognised standards, clear methodologies, and consistent metrics for assessing resilience, which can make it challenging to compare different regions and systems (O’Donnell et al., 2020).

While the literature offers several perspectives and frameworks for understanding and improving UWI resilience, there is a need for further critical analysis and methodological classification of these approaches. Some review papers have attempted to provide this type of assessment. For example, García et al. (2017) developed a quantitative resilience theory that incorporates the benefits of green infrastructure, whilst also Staddon et al. (2018) highlighted the contributions of green infrastructure to enhancing urban resilience more broadly. Fu et al., (2020) and Fu and Butler (2020) evaluated the resilience of green infrastructures in terms of integrated flood risk and resilience management, climate change and water management, and sustainable pathways. Russo et al. (2021) emphasised the role of grated inlets in urban drainage systems for improving urban flood resilience. García et al. (2017) and Fu and Butler (2020) reviewed both quantitative and qualitative aspects of decentralised systems in the context of UWI resilience. Laitinen et al. (2020) discussed the role of resilient urban water services in resolving societal and stakeholder conflicts, while Mehvar et al. (2021) presented various challenges and adaption strategies. However, additional research is needed to further evaluate and classify these different resilience perspectives and frameworks.

Although many studies have looked at different aspects and strategies for promoting resilience in UWI, there are gaps in the areas such as comprehensive comparisons and documenting approaches and strategies, software applications, and metrics. Therefore, additional research and analysis are needed to fully understand the developed framework of resilience concepts in UWI, as well as develop a comprehensive and unified understanding about UWI resilience. This would involve blending frameworks and perspectives and developing tools and methods for measuring and assessing resilience in every aspect of the system. Hence, this study aims to critically review frameworks and concepts of resilience assessment in various UWI components by analysing four main steps: (1) bibliometric analysis to highlight hot topics and main drivers, (2) describing various developed frameworks and associated approaches and characteristics, (3) identifying main strategies designed to make the frameworks effective, and (4) listing evaluation metrics and software used for developing resilience frameworks.

2. Research design and bibliometric analysis

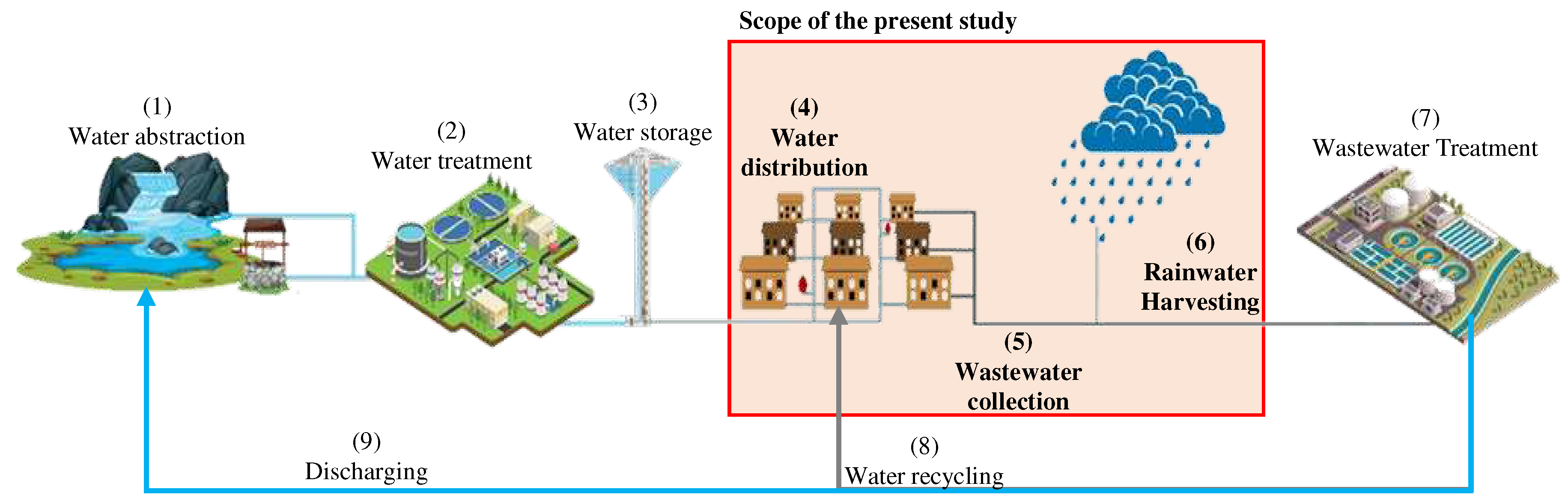

The UWI components consists of various components as shown in

Figure 2 ranging from water abstraction to wastewater treatment and more. These components are categorised into three groups: abstraction (parts 1 and 9 in

Figure 2), treatment and storage (parts 2, 3 and 7), and distribution of water supply or stormwater/wastewater collection (parts 4,5, and 6). Water abstraction is often evaluated at the watershed or basin level (Zhang et al., 2020), while resilience assessment in treatment and storage sections focuses on failure events (Piadeh et al., 2018). This study concentrates on the distribution of water supply or stormwater/wastewater collection (i.e., resilience assessment of WDS and UDS), which is referred to as UWI hereafter. These components are grouped together as they share similarities and, in some cases, complement each other.

The research database of this study was gathered from the Scopus search engine using the recommended method of searching in titles, abstracts, and keywords, as suggested by Moher et al. (2009). A set of seven search and screening strategies (S1-S7) as shown in

Table 1, were used to narrow down the search results. In total, 76 relevant studies were found and classified into four categories. The search begun with 871 publications in the first stage (S1) and gradually narrowed down in steps S2 and S3. Due to the limited scope of this study, research on wastewater abstraction, treatment, storage consumption and wastewater treatment were excluded in these stages. Ultimately, 76 studies were selected and classified as four groups: 37 studies for applied analytical approaches for resilience in UWI (S4), 68 studies for new resilience strategies (S5), 28 studies for software tools assessing resilience (S6), and 13 studies for proposed existing resilience metrics (S7).

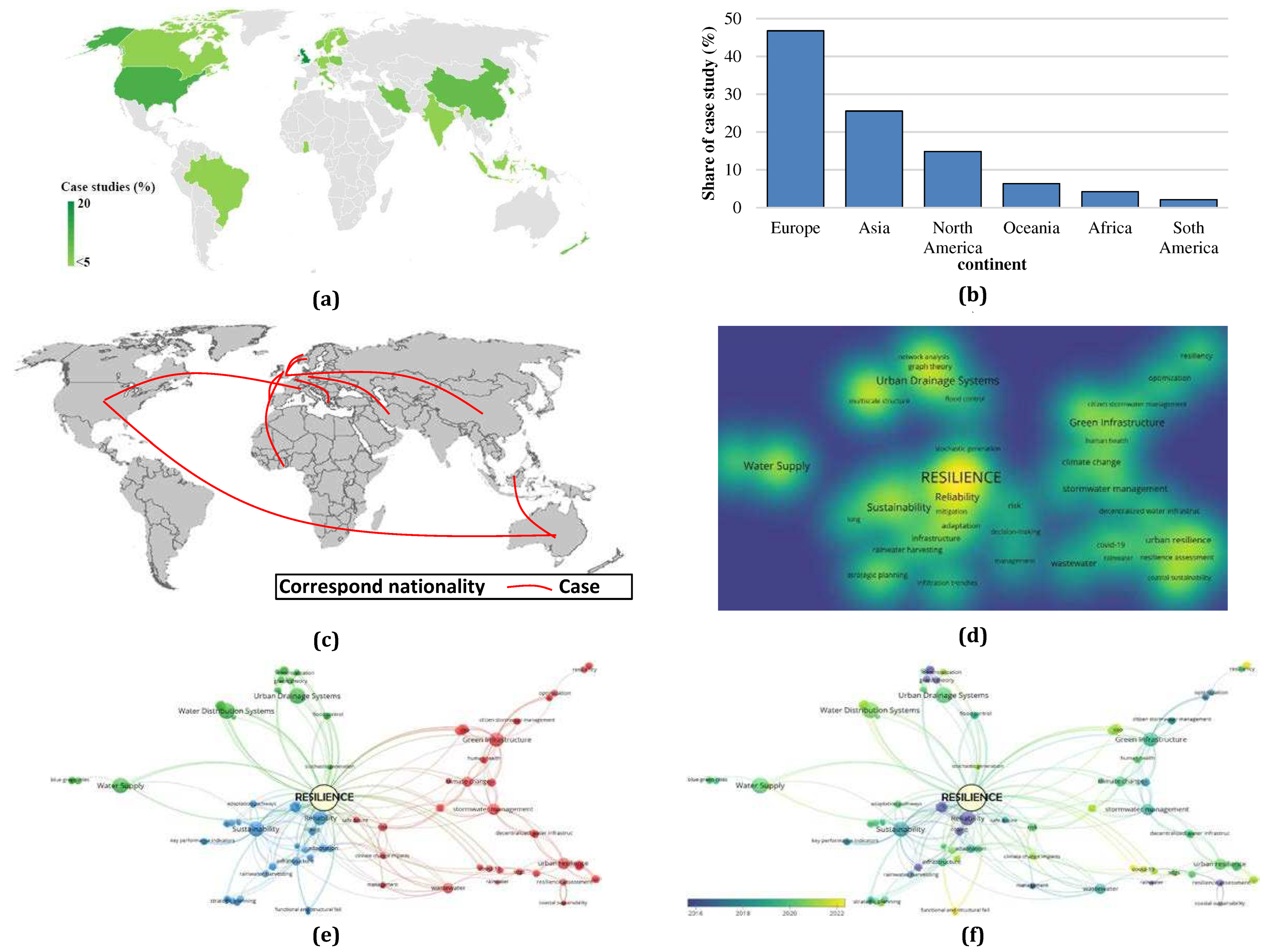

This study began by examining the retrieved publications, which included an evaluation of the geographical distribution of resilience studies. Figures 3a–3c illustrates that majority of relevant studies (33.6%) are from Europe, and there is a clear correlation between the number of publications and the level of economic development of the countries. The top three countries in terms of the number of publications are the USA (31.5%), China (12%), and the UK (10.4%) all of which have some of the world’s largest economies. This trend highlights the importance of resilience studies in the regions with high economies, both currently and in the future. As urbanisation continues to increase and climate change poses new challenges, the need for financial supports for a resilient UWI will become even more critical.

Figure 3b focuses on the accessibility of national research works and highlights a significant challenge faced by African, South American, and Oceania countries, where only a small percentage of studies (less than 20% overall) are documented. This finding underscores the need for more efforts, particularly from low- and middle-income countries, to support research and inform decision-making on UWI resilience. International collaboration is also an important factor in advancing research and promoting knowledge and expertise exchange, as evidenced by the fact that 20% of the selected articles (see

Figure 3c) are the result of such collaboration which is a positive sign that researchers have international cooperation to address the challenges of resilience in UWI.

However, as previously stated, more research is required in countries where the concept of resilience has yet to be localised. This highlights the significance of promoting capacity-building and knowledge-sharing initiatives in these regions to foster the development of research and expertise on UWI resilience. Such initiatives would ensure that the benefits of resilience are available to all communities, regardless of their geographic location or level of development.

VOS viewer software was also used to analyse the knowledge domain bibliometric track based on the co-occurrence of key terms for a specific unit of analysis (keywords titles and abstracts), type of analysis (co-occurrence) and counting method (full counting). Figures 4d to 4f shows the results of this analysis.

Figure 3d highlights the close relationship between the concepts of “reliability” and “sustainability” with “resilience” while also revealing the clear distinctions between “water supply”, “urban drainage systems”, “green infrastructure”, and “resilience” indicating that these components are well-defined individually.

Based on the content of the selected studies,

Figure 3e identifies three major clusters: the red cluster focuses on green infrastructure, the green cluster on physical components such as the distribution system, and the blue cluster on sustainability and reliability. The green cluster is dominated by research on water system design, such as risk assessment and systems optimisation. The blue cluster connects resilience to other concepts such as sustainability and reliability, and focuses on key performance indicators, adaptive plans, and failure analysis of various strategies such as rainwater harvesting. The timeline flow shown in

Figure 3f demonstrates how the research topics have evolved over time, with an initial emphasis on the interaction of sustainability, reliability, and resilience, shifting towards more practical and functional concepts, such as evaluating the performance of water system management or urban resilience. This suggests that the research community is moving towards more action-oriented approaches to resilience evaluation, which can have a greater impact on field applications. The findings of this analysis can provide insights into the current state of research on this as well as inform future research and policymaking.

3. Resilience assessment approaches

Resilience approaches are frameworks that help identify chronic or acute stressors, their link to different factors, and other aspects of resilience (Fu et al., 2020).

Table 2 summarises the two mains approaches to resilience: holistic and technical. The holistic approach emphasises the social, economic, and environmental factors that impact resilience, while the technical approach focuses on the physical and technological components of resilience. Both approaches are crucial in addressing different aspects of resilience, and the choice depends on the specific context and goals of the study.

The holistic approach involves integrating resilience as a fundamental design feature of the system, considering socio-ecological-technical factors to address chronic stressors. It evaluates the system’s capacity to withstand, adapt, and recover from shocks and stresses. This approach can be used to identify the potential risks and vulnerabilities in the system, prioritise investments in resilience-enhancing measures, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions (Rahimi-Golkhandan et al., 2022).

The holistic approach involves examining the physical, social, and environmental dimensions of UWI and their interactions. The physical infrastructure which includes the design, construction, and maintenance of water distribution, urban drainage systems, and wastewater collection, as well as the condition and durability of pipelines, pumps, and other components, is a critical aspect of resilience assessment since it forms the backbone of water infrastructure systems (Zuloaga et al., 2021). The assessment should consider the physical infrastructure’s capacity to withstand various hazards and requires an understanding of its vulnerability to these hazards and how they may affect the system’s functionality (Raj Pokhrel et al., 2023).

In addition to physical infrastructure, the assessment should also focus on social and institutional systems, which involves examining policies, regulations, and governance structures that govern water management, as well as the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, including water utilities, government agencies, and community organisations (Poch et al., 2023). Social and institutional systems are an essential aspect of resilience assessment since they influence the system’s ability to respond to and recover from shocks and stresses. The assessment should evaluate the effectiveness of the social and institutional systems in terms of coordination, communication, and collaboration among stakeholders. It should also examine the system’s capacity to mobilise resources and implement interventions to enhance resilience (Ma et al., 2020). Additionally, the natural environment’s focus should be on the ecological processes that support water infrastructure systems, such as the availability of required urban water and impacts of climate change on these systems. The natural environment influences the system’s ability to adapt and respond to changing conditions, especially droughts, floods, and sea-level rise (Quitana et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Applied resilience assessment approaches in urban water infrastructures.

Table 2.

Applied resilience assessment approaches in urban water infrastructures.

| Approach/Frameworks |

|

Description |

|

Major used application |

|

Reference |

| Holistic approaches |

| |

Safe & Sure |

|

Assessing measures of mitigation, adaptation, coping and learning, and exploring organisational and operational responses. |

|

Intermittent water supply utilities |

|

Butler et al. (2014) |

| |

S-FRESI1

|

|

Specifying major potential investment and greatest positive effect area |

|

Drainage systems |

|

Bertilsson et al. (2019a) |

| |

PESTEL2

|

|

Evaluating based on different political, economic, social, technical, legal, and environmental aspects |

|

Drainage systems |

|

Kordana and Słyś (2020) |

| |

RAF3

|

|

Following the resilience of the city from perspective of urban storm water control through NBS solutions. In this framework, three degrees (the essential, complementary, and comprehensive) are defined for resilience. |

|

City resilience |

|

Beceiro et al. (2020) |

| Technical approaches |

| |

SAF6

|

|

Systematically identifying flood impact and flood source areas along with opportunity areas for integration of different infrastructure systems to manage surface water |

|

Urban drainage system |

|

Vercruysse et al. (2019) |

| |

GRA7

|

|

Assessing potential failure, regardless of the threats. without the need to develop a scenario or identify the root of all fractures |

|

Infrastructure system |

|

Rodriguez et al. (2021) |

| |

MODM8

|

|

Multi-objective optimisation and structural resilience analysis framework, Demonstrates the relationship between these algorithms (proposed framework). |

|

Urban drainage system |

|

Bakhshipour et al. (2021a) |

| |

Smart city framework |

|

The Internet of Things concept as part of smart cities assists the development of communicating ‘items’ integrated into the overall system. This development enables new possibilities for the management of urban water infrastructure in a smart city framework. |

|

City resilience |

|

Oberascher et al. (2021) |

| 1: Spatialised Urban Flood Resilience Index |

2: Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal |

| 3: Resilience Assessment Framework |

4: Flood Resilience Framework |

5: Urban Water Optioneering tool |

| 6: Spatial Analysis Framework |

7: Global Resistance Analysis |

8: Multi Objective Decision-Making |

The technical approach focuses on improving the engineering and technical aspects of the system to increase its capacity and resilience to acute stressors or shocks (Diao et al. 2016). Unlike the holistic approaches, many technical resilience frameworks have been introduced so far (See

Table 2) but they typically aim to increase the capacity and robustness of specific system components or infrastructure to withstand and recover quickly from acute stressors such as natural disasters or system failures through targeted engineering solutions such as reinforcing pipes, and is more concerned with the physical aspects of the system rather than the social or ecological components (Fu and Butler, 2020). A technical framework for resilience assessment typically includes several elements (Valizadeh et al., 2019; Oberascher et al., 2021). The first step is to identify critical infrastructure, mapping out the infrastructure and assets to understand how they are interconnected and dependent on one another. Next, risk assessment is conducted using scenario planning and modelling to better understand the potential impacts of different hazards. A vulnerability assessment is then conducted at different levels of the system, such as individual assets, subsystems, and the overall system. Capacity assessment is conducted under different scenarios and stressors to better understand the system’s capacity for resilience. Performance evaluation involves using performance indicators to measure the effectiveness of different resilience strategies. Based on the results of the risk, vulnerability, and capacity assessments, risk management strategies are prioritised. Finally, a process for continual improvement is established, involving regular monitoring, evaluation, and review of the system’s resilience to identify areas for improvement and implement changes accordingly.

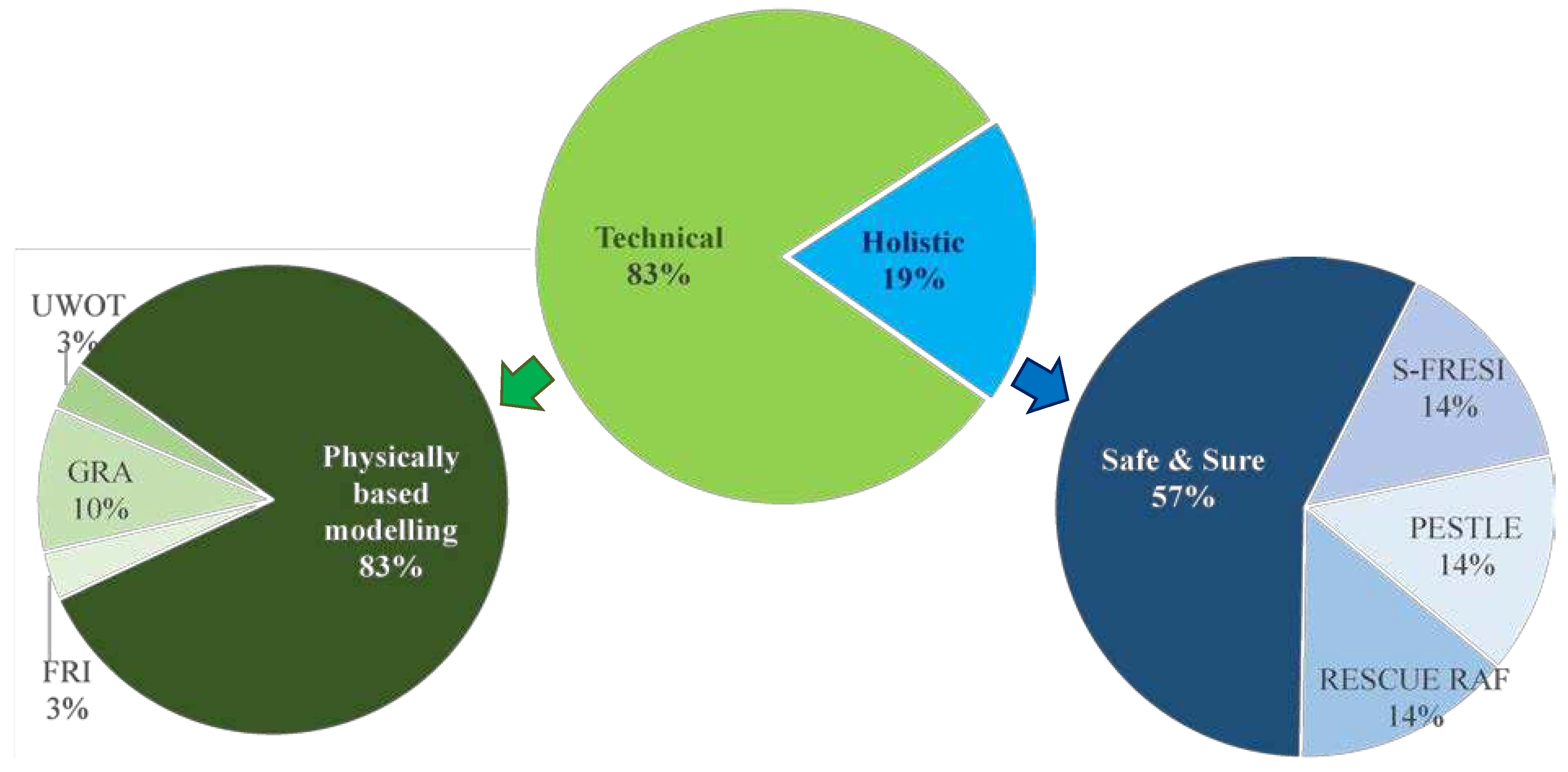

Table 2 and

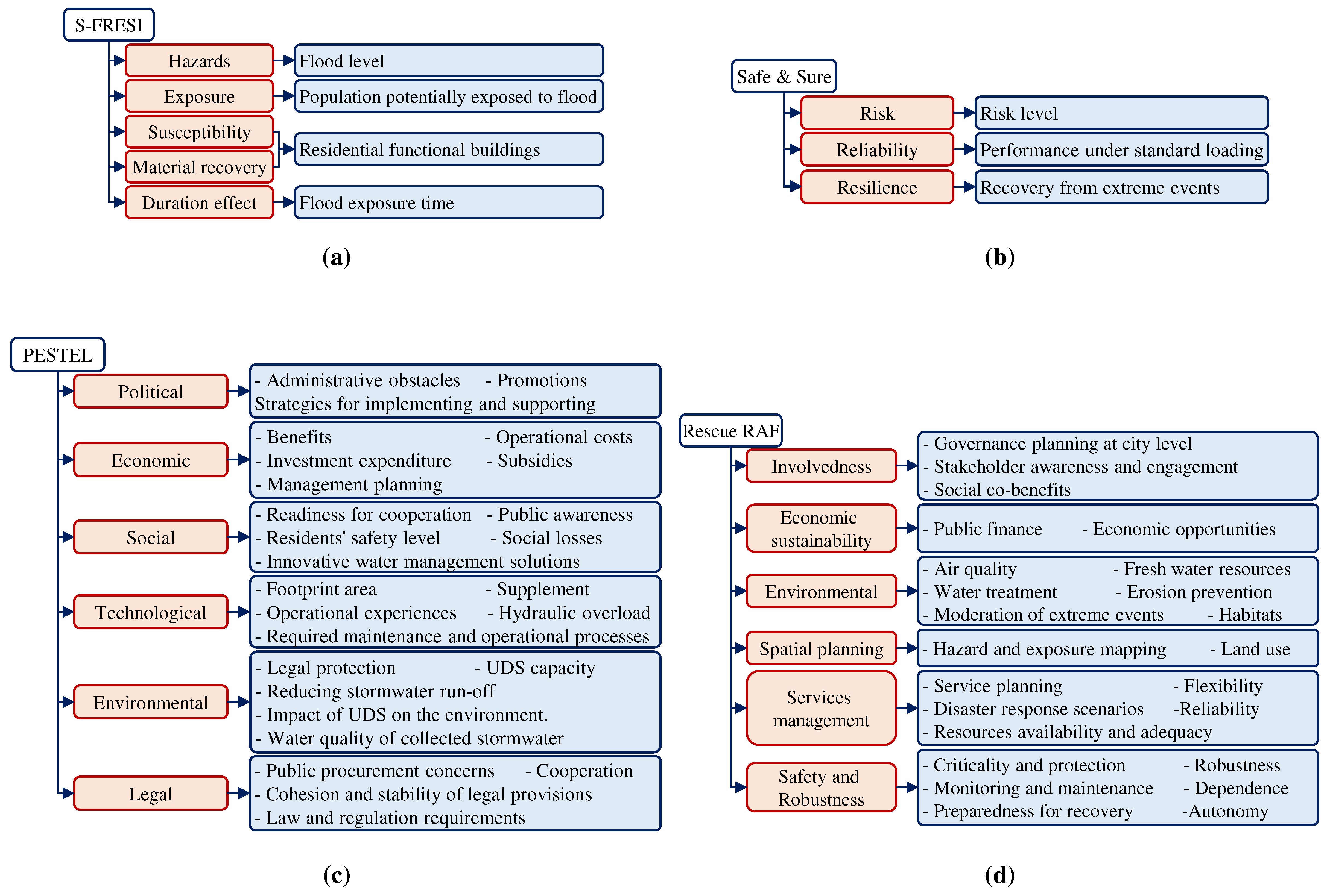

Figure 4 shows that resilience studies in the technical part are five times more common than in the holistic part. The Safe & Sure framework is the most widely used holistic framework because it assesses risk and reliability as well as calculating resilience and promotes system resilience towards urban sustainability through a circular economy-based management perspective (Fu and Butler, 2020). Physically based modelling is widely used as a part of the technical approach, particularly in urban drainage and stormwater management, because of its ability to simulate various hydraulic processes and support decision-making in the design and operation of drainage systems. It can also consider various types of disturbances and elementary failures that can system failure, including both natural and man-made hazards (Valizadeh et al. 2019).

The “S-FRESI” framework employs indices to assess urban flood resilience before, during, and after a flood. The framework is composed of three main components: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Exposure refers to the likelihood and severity of flooding, sensitivity measures the degree of susceptibility of urban systems and populations to flooding, and adaptive capacity assesses the ability of cities to recover from floods and build resilience for the future (Cea and Costabile, 2022). The sensitivity component is focused on identifying areas of risk and vulnerability in urban systems and populations to flooding. It helps to identify populations and infrastructure that may be particularly susceptible to flooding. The adaptive capacity component is used to assess the ability of cities to prepare for and recover from floods. it helps to identify areas where improvements could lead to increased resilience in the face of flooding (Ji and Chen, 2022). The accuracy and reliability of the S-FRESI depend on the availability and quality of data used. The index requires detailed information on the physical, social, and environmental characteristics of urban areas, as well as historical flood events and their impacts.

However, the availability and reliability of data required for the S-FRESI framework may be limited, especially in low- and middle-income countries where data collection and management systems may be weak or non-existent (Ro and Garfin, 2023). In addition, the accuracy and relevance of the assessment results can be impacted by the spatial scale and resolution of the assessment, which may not provide enough detail for local-level decision-making (Francisco et al., 2023). Moreover, the subjective judgments and weighting of indicators based on expert opinions and stakeholder inputs can lead to inconsistencies in results across different locations and times. This weighting of indicators may also vary depending on the context and objectives of the assessment. Furthermore, stakeholder engagement (e.g., community members, local governments, and other relevant actors) may not always be adequate, which can result in a limited understanding of local needs and priorities, as well as a lack of ownership and commitment to the assessment outcomes and recommendations (Zheng and Huang, 2023).

RAF is an extension of the S-FRESI approach and concentrates on nature-based solutions for managing and controlling stormwater. It has several critical components, such as economic sustainability, environmental factors, spatial planning, involvedness, system robustness, and level of service management. These components are then assessed and validated by external factors such as contributions and stakeholders (Cardoso et al., 2020). However, similar to S-FRESI, RAF is subject to the subjective nature of the evaluation process, and the weighting of indicators may vary depending on the context and goals of the assessment. This subjectivity may lead to inconsistencies and variations in results across different locations and times. Furthermore, involving different stakeholders can make it challenging to reach a consensus on the indicators to be included and their relative importance (Cheng et al., 2021). Although designed to assess the resilience of nature-based solutions, it may not be suitable for evaluating other water infrastructure components (Gue et al., 2021).

The PESTEL framework takes a broader view in comparison to the other two frameworks by adding policy and law factors to the assessment factors. This helps identify potential risks and opportunities that may be missed by a narrower focus. PESTEL analysis is a flexible tool that can be adjusted to different contexts and applied at different scales, from individual projects to entire cities. The insights obtained from a PESTEL analysis can inform strategic planning for urban water management by identifying priorities and focusing resources where they are most needed (Fonseca et al., 2022). However, PESTEL analysis focuses on external factors, such as political and economic conditions, which may limit its usefulness in identifying internal factors that may be contributing to resilience challenges. Furthermore, PESTEL analysis may result in inconsistencies and variations in results across different contexts and stakeholders. The external factors that impact urban water resilience are constantly changing, which can make it difficult to keep the analysis up-to-date and relevant over time (Naghedi et al., 2020).

The “Safe & Sure” framework measures the resilience of UWI using three risk-based parameters, i.e., risk assessment, risk management, and recovery assessment. Risk assessment involves identifying potential hazards and assessing their likelihood and consequences. The risk management component focuses on developing and implementing strategies to reduce the likelihood and consequences of hazards, while the recovery assessment component evaluates the effectiveness of risk management strategies and measures the overall system resilience (Butler et al., 2014). The Safe & Sure framework emphasises stakeholder engagement and collaboration in the resilience assessment process, which includes involving system operators, regulators, customers, and other stakeholders in the development and implementation of risk management strategies. One of the strengths of the Safe & Sure framework is its flexibility and adaptability to different types of critical infrastructure systems and contexts. However, like other holistic resilience assessment frameworks, the Safe & Sure framework is subject to the involvement of stakeholders and the need for comprehensive and accurate data, which may be difficult to obtain, particularly for complex and interconnected systems (Francisco et al., 2023).

“SAF” is a robust methodology designed to assess the resilience of urban areas to natural disasters. Its objective is to promote and facilitate interoperability by systematically identifying flood impact and flood source areas and identifying opportunities for integration of different infrastructure systems to manage surface water (Vercruysse et al., 2019). SAF relies heavily on the data collected and prepared for analysis using geographic information system (GIS). It uses spatial analysis to identify areas of high and low resilience based on the spatial distribution of various factors. The results of the analysis are then integrated and interpreted to identify the factors that contribute most strongly to resilience, as well as areas where interventions may be needed to improve resilience (Zhou et al., 2022).

“MODM”, alternatively, is used to assess the resilience of systems to natural disasters, especially urban flooding (Bakhshipour et al., 2021a). The approach involves identifying multiple objectives, such as minimising economic losses, social impacts, and environmental impacts, and then evaluating potential strategies for achieving these objectives. It is particularly useful in resilience assessment because it can account for the complexity and uncertainty of the systems being assessed (Liu et al., 2022). The Smart city framework for Resilience Assessment is a robust methodology designed to evaluate the resilience of cities to various shocks and stresses, including critical UWI. The framework considers the complex and interconnected nature of urban systems and aims to provide a holistic approach to resilience assessment (Oberascher et al., 2021). It incorporates a range of tools and techniques to facilitate the resilience assessment process, such as GIS mapping, stakeholder engagement, scenario planning, and risk assessments. The framework emphasises the importance of collaboration and communication between stakeholders and the need for adaptive and flexible strategies to address the changing nature of urban risks and uncertainties. However, while the framework is comprehensive, it primarily focuses on the resilience assessment of the entire city rather than specifically on UWI (Yuan et al., 2021).

Overall, technical approaches offer targeted solutions to identified problems, providing a clear focus for addressing specific issues. They often rely on data and quantitative analysis, which can lead to more objective and reliable decision-making (Büyüközkan et al., 2022). Additionally, they can be efficient in terms of time and resources since they are narrowly focused on specific issues rather than the entire system (Saikia et al., 2022). However, technical approaches can be narrow in their scope, potentially overlooking important interconnections and interdependencies within the system. Their reductionist approach may break down complex systems into their constituent parts, missing the broader picture (Balaei et al., 2020). Additionally, they may not fully engage stakeholders or consider their perspectives and needs, leading to solutions that are not sustainable in the long run (Assad and Bouferguene, 2022). In contrast, holistic approaches consider the system as a whole, considering interconnections and interdependencies between its different parts. This can lead to more comprehensive solutions that address multiple issues and are more resilient to unexpected shocks and stresses (Rasoulkhani et al., 2019). Holistic approaches also prioritise stakeholder engagement, considering their perspectives and needs in the decision-making process (Pokhrel et al., 2022). However, holistic approaches can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring a broad and detailed understanding of the system. They may also rely on subjective assessments and qualitative analysis, potentially leading to biased or incomplete decision-making (Quitana et al., 2020). Additionally, the complexity of holistic approaches may make it difficult to communicate findings to stakeholders who may not have a technical background (Zeng et al., 2022).

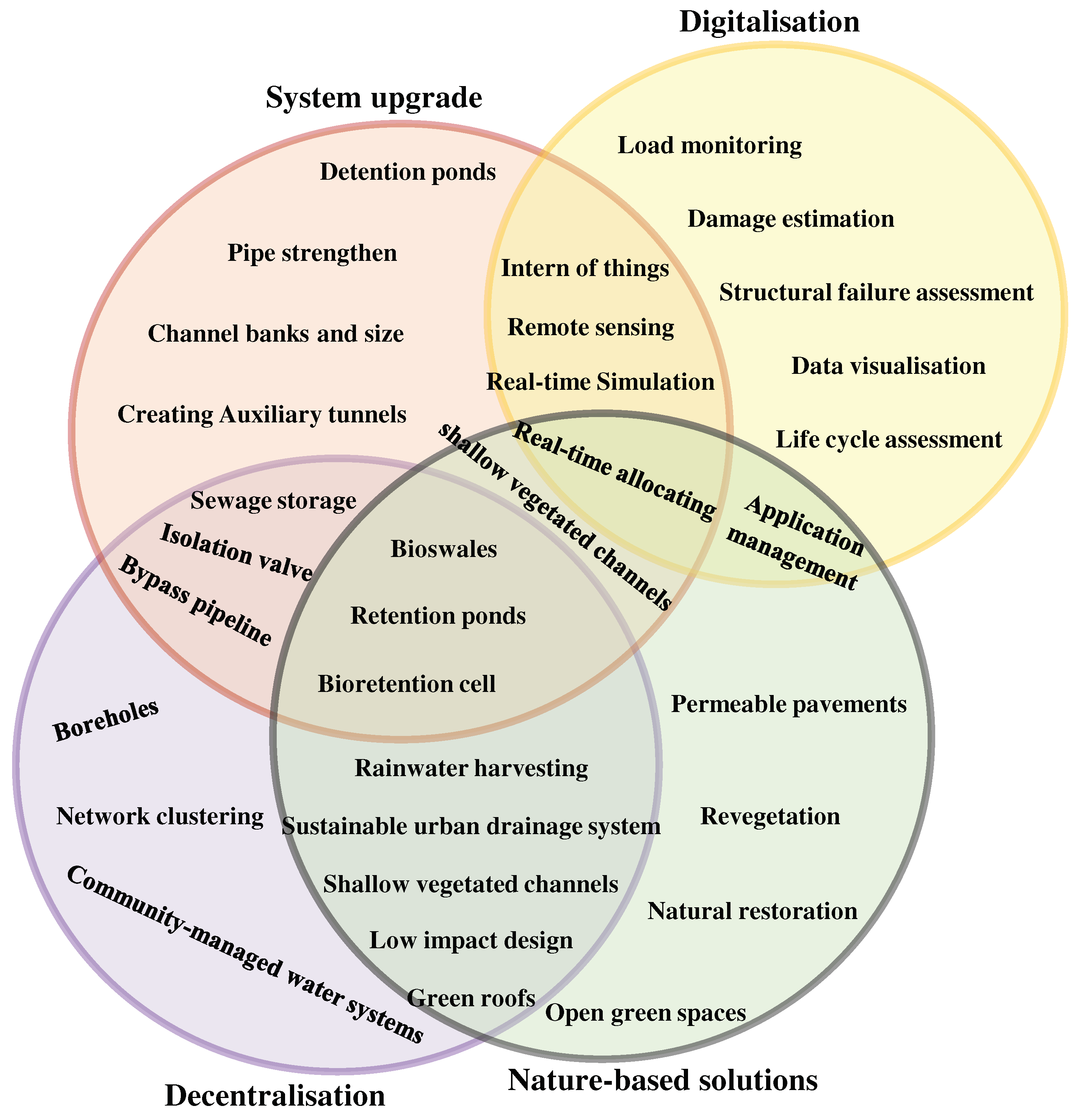

4. Resilience assessment approaches

Figure 5 depicts the four main strategies proposed to improve the resilience of urban water systems. These strategies include: (1) system upgrade involving a wide range of installation and configuration, improving and constructing physical infrastructure of the UWI, such as pipe strengthening, increasing channel banks, creating auxiliary tunnels or constructing detention ponds, (2) decentralisation where possible by introducing small-scale water related facilities or community-managed water systems, (3) nature-based solutions (NBS) integrating natural elements, such as wetlands or open green spaces into the urban water system, and (4) Smart network using digital technologies, such as sensors, computational devices and big data analytics to improve the monitoring, control and management of UWI.

System upgrade is a strategy for improving the robustness and redundancy of water infrastructure to increase it resilience. While investing in physical structures, this strategy is still widely regarded as a primary solution for increasing resilience, owing to the high investment and long-term performance that water infrastructure is expected to provide (Valizadeh et al., 2019). The majority of system upgrade involve centralised systems, which are criticised for their high energy requirements, changes to the natural hydrological system, and the long-term costs associated with their maintenance and operation (Casal-Campos et al., 2018). Decentralisation is another strategy proposed to improve UWI’s resilience. The system becomes more flexible and reduces water loss due to cutting leakage in long-distance piping networks by distributing the water and wastewater distribution network across the city (Cecconet et al., 2020). Furthermore, decentralised water systems can facilitate the circular economy of water and resources by allowing treated wastewater to be reused. Nutrients in wastewater, for example, can be recycled and used as fertiliser in agriculture, and biogas produced from organic matter can be used as a renewable energy source (Naghedi et al., 2020). This can help to reduce freshwater and energy demand, as well as waste and pollution in the environment. Decentralised systems, on the other hand, may necessitate more complex management and maintenance because they involve a greater number of smaller systems distributed throughout a city rather than a single centralised system (Leigh and Lee, 2019). This may necessitate additional resources for operation and maintenance, as well as specialised expertise.

NBS are yet another type of resilience that combines natural elements and ecosystem services to provide cost-effective solutions such as increased infiltration, evapotranspiration, and stormwater runoff storage (UN-Water, 2018). They have gained traction as an alternative or supplement to traditional UWI (Ashley et al., 2020). NBS is also known by the terms Low Impact Development (LID) and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) (See

Figure 5). This strategy can be combined with other traditional approaches, particularly flood management, to form a comprehensive strategy for long-term sustainable urban drainage (Fu and Butler, 2020). Sponge City, for example, combines LID techniques with other measures such as permeable pavements, green roofs, and rain gardens to manage stormwater and improve urban resilience (O’Donnell et al., 2020). However, the installation and maintenance of NBS can be more expensive and take up more space than traditional solutions (Rentachintala et al., 2022). Furthermore, professional education and training may be required for their successful implementation (D’ambrosio et al., 2021). Furthermore, more research is needed to determine the efficacy of these strategies, particularly for unpredictable extreme weather events, and limitations in the availability of suitable green spaces and land for implementation may also pose a challenge (Jato-Espino et al., 2022).

Recent advances in smart network modelling have played an important and expanding role in addressing the challenges. The use of real-time data, advanced analytics, and modelling techniques to improve the management and operation of urban drainage networks is referred to as smart network modelling. It can assist decision makers and engineers in identifying potential issues before they become major issues, optimising system performance, and making more informed infrastructure investments decisions (Piadeh et al., 2022b). Smart network modelling can also help improve urban drainage network resilience by providing better insights into the impact of extreme weather events and other potential disruptions (Boulos, 2017). The integration of IoT devices, wireless sensors, and remote sensing applications with existing systems (See

Figure 5) can allow for the development of smart systems that use forecasting models. Smart rainwater harvesting systems, for example, can release stored stormwater automatically before rainy events to provide additional enclosed volumes and reduce the risk of flooding (Behzadian et al., 2018). Such can also be used to monitor and manage water quality, detect leaks and blockages in near real-time, and provide operators with the information needed to take appropriate actions (Oberascher et al., 2021). This can aid in the prevention and resolution of issues, lowering the risk of water contamination, flooding, and other UWI-related issues (Tuptuk et al., 2021).

As illustrated in

Figure 5, while each of these strategies provides valuable information on its own, these strategies can be interrelated. Integrating various strategies can result in more effective and long-lasting UWI. Also, this would improve their ability to provide excellent customer service in the event of unanticipated system failures (Mugume et al., 2015). Within this context, creating an emergency response plan and setting up backup water distribution systems can help with swift action in the event of water-related disasters thus, increasing UWI resilience-based resistance. Alternatively, upgraded systems can combine digital technology like smart sensors and monitoring systems to aid in the detection of leaks and faults, resulting in a smarter regime and faster system repairs and maintenance (Oberascher et. al., 2022). Moreover, neighbourhood water recycling facilities and rainwater harvesting systems can be integrated with digital technology, decentralised systems can become flexible and adaptable to changing water demands, assisting in water rationing during disruptions and thus increasing resilience in situations where UWI systems resistance fail (Oberascher et al., 2021). Digitalisation and nature-based solutions can be also coupled to increase the resilience of urban water infrastructure. For instance, digital technologies and nature-based solutions can be integrated to strengthen UWI resilience through smart green roof (Busker et al., 2022). These systems use sensors to track weather conditions, soil moisture levels, and plant water requirements to optimise irrigation schedules. Flood monitoring and warning systems can also be combined with green infrastructure to serve as a preparedness and emergency response mechanism, increasing UWI’s resilience. These alert systems or devices sensors keep track of rainfall patterns and water levels to provide early flood warnings (Liu et al., 2021). Additionally, decision-makers can gain a better understanding of the water system by combining data from various sources such as sensors, weather forecasts, and water quality monitoring systems. It can also reduce unnecessary infrastructure and costs by providing real-time data that allows for more efficient and targeted system maintenance and operation (Rodriguez et al., 2021).

Figure 5 also shows integration of decentralisation and NBS n bring several benefits, including surface runoff control in decentralised distribution network settings thus, reducing load on centralised systems. For example, during high precipitation, integrating rain gardens, wetlands, rainwater harvesting, and permeable pavements near the decentralised network system can improve biodiversity and urban cooling, hence boosting UWI resilience. (Hartmann et. al., 2019). Furthermore, adding permeable pavement to a decentralisation network, can allow precipitation to sink into the ground through its porous materials, improving stormwater management in decentralised network settings. Using this integration strategy in the parking lot or pathways of decentralised distribution system surroundings will reduce surface water runoff and improve water quality in and around decentralised network infrastructure (Judeh et. al., 2022). Besides, the risk of flooding in decentralised distribution network settings can be reduced by employing wetlands, which aid with stormwater management and reduce the risk of flooding in UWI facilities. Further to this, green roofs can also be employed to treat and filter water, lessening the pressure on decentralisation facilities (Moises and Kunguma, 2023).

Another integrated strategy is to advance the upgraded systems by NBS and decentral systems. This strategy has experienced development constraints due to a lack of tools and collated information to determine or uncover its long-term value. However, the method of combining NBS solutions with system upgrades has the potential to increase and contribute to UWI resilience in urbanised areas from the perspectives of resource efficiency, societal, economic, and environmental gains (Beceiro et. al., 2022). In UWI settings, the integration of system upgrades and infiltration trenches, vegetative swales, and rain gardens would help to regulate stormwater runoff, alleviating demand on UWI and, as a result, pressure on urban drainage assets in urbanised areas. Replacing old drainage network pipes with newer ones, can be an expensive upgrade work that many communities cannot afford, so integrating NBS techniques will assist communities that cannot afford such expensive UWI improvement or upgrade works to have a more affordable and resilient UWI. Another strategy can be integration of a piped combined sewer network along with detention pond to relieve stress on the piped network in the case of a failure (Chakraborty et al., 2022).

The advantages of combining a decentralised distribution network and a system upgrade also include increased system efficacy, persistency, adaptability, transformability, and sustainability of service provision, demonstrating UWI resilience by proactively providing new infrastructure to the decentralised system at a lower cost (Hall et. al., 2019). For example, replacing old pipes in a decentralised system may be less expensive than doing the same improvement works to modernise a centralised distribution system. Additionally, such improvement works in a decentralised system will necessitate shorter length pipes. In this context, system upgrades and decentralisation would more effectively manage water loss owing to leaks in long pipe networks and other wastage, strengthening the efficacy and resilience of urban water infrastructure (McClymont et. al., 2020).

However, cooperation and coordination among the numerous stakeholders, is required for the successful implementation of such integrated UWI resilience strategies. Different objectives and priorities, for instance, can make it challenging to align their efforts towards the common goal of the resilience strategy. Power imbalances between stakeholders can also lead to conflicts and hinder cooperation and coordination. Furthermore, lack of trust between stakeholders can be challenging to share information and resources, and conflicts may arise. Although effective communication is crucial for successful cooperation and coordination, communication barriers such as language differences, cultural differences, and technical jargon can make it difficult for stakeholders to understand each other. Finally, implementing integrated UWI resilience strategy may require significant financial and human resources, which may not be available to all stakeholders (Mehvar et al., 2021; Patra et al., 2021).

5. Resilience indicators

Measuring and assessing system resiliency is critical for effective decision-making and sustainable management. While holistic approaches evaluate resilience using quantitative or descriptive indicators, technical approaches use quantitative metrics.

Figure 6 depicts the various aspects and indicators defined for each framework of the holistic approach. S-FRESI, which focuses on measuring resilience in the face of flood occurrence, demonstrates resilience based on hazard level, population potentially exposed to flooding, density of residential building, and duration of water exposure with the population (Bertilsson et al., 2019a). The exposure component is determined by a range of factors, including the frequency and magnitude of flooding events, the spatial distribution of flood risk across the urban area, and the potential consequences of flooding for people and infrastructure. The sensitivity component evaluates factors such as the density and demographics of the population, the quality and age of infrastructure, and the availability of emergency response resources. Adaptive capacity, including susceptibility, material recovery and duration effect, involves evaluating factors such as the availability and quality of emergency management plans and resources, the effectiveness of disaster response systems, and the capacity of local government and civil society to coordinate and respond effectively to flood events (Cea and Costabile, 2022; Ji and Chen, 2022).

The framework includes two stages, where the first stage focuses on measuring the nature-based solution at the planning level, stakeholder awareness, public finance, economic opportunities, citizens’ engagement and accessibility, social co-benefits, freshwater provision, water treatment, erosion prevention and maintenance of soil fertility, and habitats for species promotion. The second stage assesses the role of selected nature-based solutions at the city level by measuring hazard and exposure mapping, land use and inclusion, service management and planning, resource availability and adequacy, flexible service, scenarios relevance for disaster response, infrastructure assets criticality and protection, infrastructure assets robustness, infrastructure monitoring and maintenance, infrastructure preparedness for recovery and build back, infrastructure dependence, and infrastructure autonomy (Cardoso et al., 2020). The RAF framework emphasises the involvement of stakeholders in UWI’s resilience, measuring their awareness and participation, and social co-benefits. However, the subjectivity of the assessment process and the involvement of different stakeholders can lead to divergent views and objectives, making it challenging to reach a consensus on the indicators to be included and their relative importance (Cheng et al., 2021).

Alternatively, the PESTEL method measures a variety of indicators, as shown in

Figure 6c, ranging from level of administrative obstacles and the degree of promotion of a sustainable solution to the readiness of various stakeholders and the potential for using innovative solutions. Political factors refer to the influence of government policies and regulations on the urban water system. This includes issues such as water governance, water pricing policies, and regulations related to water safety. Economic factors refer to the impact of economic conditions on the urban water system. This includes issues such as funding for water infrastructure, the cost of water treatment and distribution, and the impact of economic shocks such as recessions on the system. Sociocultural factors refer to the influence of social and cultural factors on the UWI. This includes issues such as public attitudes, the impact of demographic changes, and the influence of social norms and values (Kordana and Słyś 2020). Technological factors refer to the impact of technological innovations and developments on the UWI. This includes issues such as the use of smart technologies for water management, the development of new technologies, and the impact of climate change on the technological infrastructure of the system. Environmental factors refer to the impact of natural and environmental factors on the UWI. This includes issues such as the impact of climate change on water availability and quality, the impact of natural disasters such as floods and droughts on the system, and the impact of environmental degradation on the resilience of the system. Legal factors refer to the impact of laws and regulations on UWI. This includes issues such as water rights, water allocation policies, and regulations related to water quality and safety (Lee and Jepson, 2020).

The “Safe & Sure” approaches to assessing UWI’s resilience employs three key indicators: risk level, reliability degree, and recovery rate from extreme events. Risk assessment involves analysing the physical, technological, and operational vulnerabilities of the system, as well as its dependencies on other systems and stakeholders. The risk management component includes measures such as redundancy, diversity, and robustness, as well as plans for emergency response and recovery. The recovery assessment involves evaluating the system’s ability to absorb and recover from disruptions, adapt to changing conditions, and maintain essential services and functions.

Table 3 includes a list of the most used metrics for assessing the effectiveness of technical frameworks. Most of the introduced metrics are applicable flood evaluation in conjunction with nature-based-solutions. Flood volume reduction is often considered in these models. Other models concentrate on disruption and recovery time. For example, robustness, pipe failure, and floods are all measured as part of resilience index based on duration of disruption or recovery. However, one of the most difficult aspects using these metrics is determining metrics are appropriate for a given system or application, as different metrics may be relevant depending on the context. Another challenge is ensuring that the data used to calculate the metrics is accurate and up to date, which may necessitate significant data collection and analysis resources. Finally, some metrics may be difficult to measure directly, necessitating the use of proxies or estimates, adding uncertainty to the analysis.

As a result, it appears that measuring and quantifying resilience can be difficult, with no single universally accepted method. There are numerous frameworks and models that attempt to capture the various dimensions of resilience, but each has limitations and potential biases. Furthermore, because resilience is a complex and dynamic concept, developing metrics and models that accurately capture all the relevant factors and interactions can be difficult. Nonetheless, efforts to measure and evaluate resilience are critical for better understanding the concept and guiding decision-making in areas such as urban water management.

“FRI” is another technical approach that investigates resilience in two stages: response and recovery time. In response phase water depth and flood duration are measured and in recovery phase flood severity, total water depth, and total flood are measured. Furthermore, rate of affected elderly population, women households, and children in collaboration with household income will also be measured.

6. Resilience-simulating tools

Several technical frameworks used to assess the resilience of UWI are provided in

Table 2 and

Figure 4. Physically based modelling is an effective tool that can predict how UWI behaves under different stressors and scenarios. It can simulate the impacts of natural disasters, such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes, on UWI, and assess the effectiveness of various resilience measures. For example, it can predict the behaviour of water distribution networks under different scenarios, such as power outages, pipe failures, and extreme weather events, and identify areas that require resilience measures (Ebrahimi et al., 2022). Furthermore, physically based modelling can evaluate the effectiveness of different adaptation strategies, such as green infrastructure, in reducing the vulnerability of UWI to natural disasters. This approach is linked to global resilience analysis (GRA), which assesses the resilience of systems and communities at a global level (Hochrainer-Stigler et al., 2020). GRA involves identifying the key drivers and indicators of resilience, analysing their interconnections, and assessing the resilience of systems and communities based on their ability to adapt and respond to shocks and stresses (Diao et al., 2016).

Four software tools that are commonly used in the selected research works for modelling the UWI and simulating the resilience performance (

Table 4) are (1) Storm Water Management Model (SWMM), (2) MIKE Urban, (3) WaterMet

2, and (4) System for Infrastructure Modelling and Assessment (SIMBA). The first two tools (SWMM and MIKE URBAN) are physically based models that are typically data demanding and hence their applications are limited to those components that access to all physical data is available. However, WaterMet

2 and SIMBA are conceptually based models that are less data demanding with a simplified system components used for modelling purposes. Although MIKE Urban allows the integration of real-time data, such as weather forecasts and sensor measurements, to provide more accurate modelling and predictions (Valizadeh et al., 2019), SWMM is more popular due to its free availability and greater capabilities in simulating single flood events or long-term runoff (Guptha et al., 2022). WaterMet

2 is a software tool used for both technical and holistic approaches in an integrated UWI. It can also combine hydrological, hydraulic, and water quality models to simulate and optimise UWI performance (Behzadian and Kapelan 2015). SIMBA is a comprehensive tool that models various UWI components and uses a simulation-based holistic approach to assess the performance of UWI under various scenarios, such as changing population or climate conditions (Sweetapple et al., 2019). This software supports decision-making in the planning, design, and operation of UWI.

“UWOT” (Urban Water Optioneering tool) is a conceptually based modelling tool for performance assessment of UWS and can be efficiently used to estimate resilience indicators of various water management options (e.g., household appliances and fittings or rainwater harvesting schemes) under various scenarios/stressors. UWOT also estimates energy required by water appliances, evaluates water and wastewater reuse and other green technologies (Nikolopoulos et al. 2019).

7. Conclusions

In the current scope, this study aimed to map recent attempts in resilience assessment of urban water systems (i.e., urban water distribution and urban drainage systems). The study included a brief bibliometric and scientometric analysis, as well as a discussion of major approaches, applied strategies, and associated relevant indicators and metrics. The current study highlights the following research findings:

- -

Most of the research in this area has been conducted in developed countries with strong economics, highlighting the importance of these systems from a macroeconomic perspective and highlighting the need for in-depth localised research in many parts of the world.

- -

The study’s findings reveal three major research areas: (1) system design, which includes risk assessment and system optimisation, (2) resilience in relation to other concepts such as sustainability and reliability, (3) green infrastructure implementation.

- -

Although that the concepts of “reliability” and “sustainability” are closely related to the concept of resilience, there are clear boundaries between “water supply,” “urban drainage systems’, “green infrastructure,” and “resilience. This finding suggests that in the future, more emphasis should be placed on integrating these systems as comprehensive approaches.

- -

This study identified two major approaches to assessing the resilience of urban water systems: (1) holistic approach and (2) technical approach. Approximately 80% of the research was conducted using technical approaches, the majority of which involved physically based modelling of the UWI. While technical approaches introduced nine different frameworks, holistic approaches identified only four major frameworks. The Safe & Sure framework was chosen by half of the papers that used the holistic approach because of its high ability to assess resilience based on system responsiveness, as well as its ability to assess risk and reliability.

- -

While the identified strategies of (1) system upgrade, (2) decentralisation, (3) digitalisation, and (4) nature-based solutions may contribute to promoting resilience in urban water systems, they may not be sufficient to achieve all resilience goals on their own. As a result, multifaceted and integrated solutions that combine digital technologies and nature-based options for instance should be tested to upgrade current systems while focusing on decentralisation. This comprehensive and integrated concept appears to be required for further investigation.

- -

While each holistic approach introduces some aspects of UWI resilience assessment, there is no significant correlation between these indicators. When various metrics are introduced into technical frameworks, the same problem arises. This problem results in an inability to properly compare different implemented resilience options in different case studies, which can lead to a lack of relatively universal solutions. As a result, introducing comprehensive and qualified indicators (for the holistic approach) or quantified metrics (for technical approaches) can help effectively address this problem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization & methodology, Asghari, Piadeh, Egyir and Behzadian; methodology, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Asghari, Piadeh and Egyir; writing—review and editing, Behzadian; supervision, Yousefi, Rizzuto and Campos. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ashley, R., Gersonius, B., Horton, B. (2020). Managing flooding: From a problem to an opportunity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 378 (2168), p.20190214. [CrossRef]

- Assad, A., Bouferguene, A. (2022). Resilience assessment of water distribution networks—Bibliometric analysis and systematic review. Journal of Hydrology, 607, p.127522. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshipour, A., Hespen, J., Haghighi, A., Dittmer, U., Nowak, W. (2021). Integrating structural resilience in the design of urban drainage networks in flat areas using a simplified multi-objective optimisation framework. Water, 13(3), p.269. [CrossRef]

- Balaei, B., Wilkinson, S., Potangaroa, R., McFarlane, P. (2020). Investigating the technical dimension of water supply resilience to disasters, Sustainable Cities and Society, 56, p.102077. [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, P., Brito, R., Galvão, A. (2020). The contribution of NBS to urban resilience in stormwater management and control: A framework with stakeholder validation. Sustainability, 12(6), p.12062537. [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, P., Brito, R. S., Galvao, A. (2022) Nature-based solutions for water management: insights to assess the contribution to urban resilience. Blue-Green Systems, 4 (2), pp. 108–134. [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, K., Kapelan, Z. and Morley, M.S. (2014) Resilience-based performance assessment of water-recycling schemes in urban water systems. Procedia Engineering, 89, pp.719-726. [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, K. and Kapelan, Z. (2015) Modelling metabolism-based performance of an urban water system using WaterMet2. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 99, pp.84-99. [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, K., Mousavi, J., Kapelan, Z., Alani, A. (2018). Resilience of Integrated Urban Water Systems. 44(0). Water Efficiency Conference, pp. 5-7, Aveiro, Portugal, [Online] available at repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/5374 [Accessed 28/02/2023].

- Bertilsson, L., Wiklund, K., Tebaldi, I., Rezende, O., Veról, A., Miguez, M. (2019). Urban flood resilience—A multi-criteria index to integrate flood resilience into urban planning. Journal of Hydrology, 573, pp. 970–982. [CrossRef]

- Busker, T., Moel, H., Haer, T., Schmeits, M., Hurk, B., Myers, K., Cirkel, D., Aerts, J. (2022). Blue-green roofs with forecast-based operation to reduce the impact of weather extremes. Journal of Environmental Management, 301, p.113750. [CrossRef]

- Butler, D., Farmani, R., Fu, G., Ward, S., Diao, K., and Astaraie-Imani, M. (2014). A new approach to urban water management: Safe and sure. Procedia Engineering, 89, pp. 347–354. [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G., Ilıcak, Ö. Feyzioğlu, O. (2022). A review of urban resilience literature. Sustainable Cities and Society, 77, p.103579. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M., Brito, R., Pereira, C., Gonzalez, A., Stevens, J., Telhado, M. (2020). RAF Resilience Assessment Framework—A Tool to Support Cities’ Action Planning. Sustainability, 12, p.2349. [CrossRef]

- Casal-Campos, A., Sadr, S., Fu, G., Butler, D. (2018). Reliable, Resilient and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems: An Analysis of Robustness under Deep Uncertainty. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(16), pp. 9008–9021. [CrossRef]

- Cea, L., Costabile, P. (2022). Flood Risk in Urban Areas: Modelling, Management and Adaptation to Climate Change. A Review. Hydrology, 9, p.50. [CrossRef]

- Cecconet, D., Raček, J., Callegari, A., Hlavínek, P. (2020). Energy recovery from wastewater: A study on heating and cooling of a multipurpose building with sewage-reclaimed heat energy. Sustainability, 12(1), p.12010116. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T., Biswas, T., Campbell, L., Franklin, B., Parker, S., Tukman, M. (2022). Feasibility of afforestation as an equitable nature-based solution in urban areas. Sustainable Cities and Society, 81, p.103826. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Leandro, J. (2019). A Conceptual Time-Varying Flood Resilience Index for Urban Areas: Munich City. Water, 11(4), p.830. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y, Elsayed, E, Huang, Z. (2021). Systems resilience assessments: a review, framework and metrics, International Journal of Production Research, 60(2), pp. 595-622. [CrossRef]

- D’ambrosio, R., Longobardi, A., Balbo, A., Rizzo, A. (2021). Hybrid approach for excess stormwater management: Combining decentralized and centralized strategies for the enhancement of urban flooding resilience. Water, 13(24), p.3635. [CrossRef]

- Diao, K., Sweetapple, C., Farmani, R., Fu, G., Ward, S., Butler, D. (2016). Global resilience analysis of water distribution systems. Water Research, 106, pp. 383-393. [CrossRef]

- Duin, B., Zhu, D., Zhang, W., Muir, R., Johnston, C., Kipkie, C., Rivard, G. (2021). Toward More Resilient Urban Stormwater Management Systems-Bridging the Gap From Theory to Implementation. Frontiers in Water, 3, p.671059. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A., Mortaheb, M., Hassani, N., Taghizadeh-yazdi M. (2022). A resilience-based practical platform and novel index for rapid evaluation of urban water distribution network using hybrid simulation. Sustainable Cities and Society, 82, p.103884. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, K., Espitia, E., Breuer, L., Correa, A. (2022). Using fuzzy cognitive maps to promote nature-based solutions for water quality improvement in developing-country communities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 377, p.134246. [CrossRef]

- Francisco, T., Menezes, O., Guedes, A., Maquera, G., Neto, D., Longo, O., Chinelli, C., Soares, C. (2023). The Main Challenges for Improving Urban Drainage Systems from the Perspective of Brazilian Professionals. Infrastructures, 8, p.5. [CrossRef]

- Fu, G., Butler, D. (2020). Pathways towards sustainable and resilient urban water systems. Water-Wise Cities and Sustainable Water Systems: Concepts, Technologies, and Applications, pp. 3–24. [CrossRef]

- Fu, G., Meng, F., Casado, M., Kalawsky, R. (2020). Towards integrated flood risk and resilience management. Water, 12(6), p.1789. [CrossRef]

- García, P., Butler, D., Comas, J., Darch, G., Sweetapple, C., Thornton, A., Corominas, L. (2017). Resilience theory incorporated into urban wastewater systems management. State of the art. Water Research, 115, pp. 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Gue, D., Shan, M., Owusu, E. (2021). Resilience Assessment Frameworks of Critical Infrastructures: State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings, 11, p.464. [CrossRef]

- Guptha, G., Swain, S., Al-Ansari, N., Taloor, A., Dayal, D. (2022). Assessing the role of SuDS in resilience enhancement of urban drainage system: A case study of Gurugram City, India. Urban Climate, 41, p.101075. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J., Borgomeo, E., Bruce, A., Di Mauro, M., Mortazavi-Naeini, M. (2019) Resilience of Water Resource Systems: Lessons from England. Water Security, 8, p.100052. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T., Slavíková, L., McCarthy, S. (2019) Nature-Based Solutions in Flood Risk Management. 1st Ed., Nature-Based Flood Risk Management on Private Land, Springer, pp. 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Laurien, F., Velev, S., Keating, A., Mechler, R. (2020). Standardized disaster and climate resilience grading: A global scale empirical analysis of community flood resilience. Journal of Environmental Management, 276, p.111332. [CrossRef]

- Jato-Espino, D., Toro-Huertas, E., Güereca, L. (2022). Lifecycle sustainability assessment for the comparison of traditional and sustainable drainage systems. Science of the Total Environment, 817, p.152959. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J., Chen, J. (2022). Urban flood resilience assessment using RAGA-PP and KL-TOPSIS model based on PSR framework: A case study of Jiangsu province, China. Water Science & Technology, 86(12), pp. 3264–3280. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J., Chang, N., Harji, R., Ruppert, T. (2018). Coupling infrastructure resilience and flood risk assessment via copulas analyses for a coastal green-grey-blue drainage system under extreme weather events. Environmental Modelling & Software, 100, pp. 82–103. [CrossRef]

- Judeh, T., Shahrour, I., Comair, F. (2022) Smart Rainwater Harvesting for Sustainable Potable Water Supply in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas. Sustainability, 14, p.9271. [CrossRef]

- Kordana, S., Słyś, D. (2020). An analysis of important issues impacting the development of stormwater management systems in Poland. Science of the Total Environment, 727, p.138711. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K., Jepson, W. (2020). Drivers and barriers to urban water reuse: A systematic review. Water Security, 11, p.100073. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N., Lee, H. (2019). Sustainable and resilient urban water systems: The role of decentralization and planning. Sustainability, 11(3), p.918. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Lin, Z., Chiueh, P. (2022). Improving urban sustainability and resilience with the optimal arrangement of water-energy-food related practices. Science of The Total Environment, 812, p.152559. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Engel, B., Feng, Q. (2021). Modelling the hydrological responses of green roofs under different substrate designs and rainfall characteristics using a simple water balance model. Journal of Hydrology, 602, p.126786. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Jiang, Y., Swallow, S. (2020). China’s sponge city development for urban water resilience and sustainability: A policy discussion. Science of The Total Environment, 729, p.139078. [CrossRef]

- McClymont, K., Morrison, D., Beevers, L., Carmen, E. (2020) Flood resilience: a systematic review, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63(7), pp. 1151-1176. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6(7), p.e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Moisès, D., Kunguma, O. (2023) Strengthening Namibia’s Flood Early Warning System through a Critical Gap Analysis. Sustainability, 15, p.524. [CrossRef]

- Momeni, M., Behzadian, K., Yousefi, H. and Zahedi, S. (2021). A Scenario-Based Management of Water Resources and Supply Systems Using a Combined System Dynamics and Compromise Programming Approach. Water Resources Management, 35(12), pp. 4233–4250. [CrossRef]

- Mugume, S., Gomez, D., Fu, G., Farmani, R., Butler, D. (2015). A global analysis approach for investigating structural resilience in urban drainage systems. Water Research, 81, pp. 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Naghedi, R., Alavi Moghaddam, M., Piadeh F. (2020). Creating functional group alternatives towards integrated industrial wastewater recycling system: Case study of Toos Industrial Park (Iran). Journal of Cleaner Production, 257, p.120464. [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D., Alphen, H., Vries, D., Palmen, L., Koop, S., Thienen, P., Medema, G., Makropoulos, C. (2019). Tackling the “New Normal”: A resilience Assessment Method Applied to Real-World Urban Water Systems. Water, 11(2), p.330. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E., Thorne, C., Ahilan, S., Arthur, S., Birkinshaw, S., Butler, D., Dawson, D., Everett, G., Fenner, R., Glenis, V., Kapetas, L., Kilsby, C., Krivtsov, V., Lamond, J., Maskrey, S., O’Donnell, G., Potter, K., Vercruysse, K., Vilcan, T. and Wright, N. (2020). Sustainable Flood Risk and Stormwater Management in Blue-Green Cities; an Interdisciplinary Case Study in Portland, Oregon. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 56(5), pp. 757–775. [CrossRef]

- Oberascher, M., Dastgir, A., Li, J., Hesarkazzazi, S., Hajibabaei, M., Rauch, W. and Sitzenfrei, R. (2021). Revealing the challenges of smart rainwater harvesting for integrated and digital resilience of urban water infrastructure. Water, 13(14), p.13141902. [CrossRef]

- Oberascher, M., Rauch, W., Sitzenfrei, R. (2022). Towards a smart water city: A comprehensive review of applications, data requirements, and communication technologies for integrated management. Sustainable Cities and Society, 76, p.103442. [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A., Kermanshachi, S., Adepu, N., Safapour, E. (2021). Resilience in water infrastructures: A review of challenges and adoption strategies. Sustainability, 13(23), 12986. [CrossRef]

- Patra, D., Chanse, V., Rockler, A., Wilson, S., Montas, H., Shirmohammadi, A., Leisnham, P. (2021). Towards attaining green sustainability goals of cities through social transitions: Comparing stakeholders’ knowledge and perceptions between two Chesapeake Bay watersheds, USA. Sustainable Cities and Society, 75, p.103318. [CrossRef]

- Piadeh, F., Ahmadi, M., Behzadian, K. (2018). Reliability Assessment for Hybrid Systems of Advanced Treatment Units of Industrial Wastewater Reuse Using Combined Event Tree and Fuzzy Fault Tree Analyses. Journal of Cleaner Production, 201, pp. 958-973. [CrossRef]

- Piadeh, F., Ahmadi, M., Behzadian, K. (2022a). A Novel Planning Policy Framework for the Recognition of Responsible Stakeholders in the of Industrial Wastewater Reuse Projects. Journal of Water Policy, 24(9), pp. 1541–1558. [CrossRef]

- Piadeh, F., Behzadian, K. Alani, A.M. (2022b). A Critical Review of Real-Time Modelling of Flood Forecasting in Urban Drainage Systems. Journal of Hydrology, 607, p.127476. [CrossRef]

- Poch, M., Aldao, C., Godo-Pla, L., Monclús, H., Popartan, L., Comas, J., Cermerón-Romero, M., Puig, S., Molinos-Senante, M. (2023). Increasing resilience through nudges in the urban water cycle: An integrative conceptual framework to support policy decision-making. Chemosphere, 317, p.137850. [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S., Chhipi-Shrestha, G., Hewage, K., Sadiq, R. (2022). Sustainable, resilient, and reliable urban water systems: making the case for a “one water” approach. Environmental Reviews, 30(1), pp.10-29. [CrossRef]

- Quitana, G., Molinos-Senante, M., Chamorro, A. (2020). Resilience of critical infrastructure to natural hazards: A review focused on drinking water systems. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 48, p.101575. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Golkhandan, A., Aslani, B., Mohebbi, S. (2022). Predictive resilience of interdependent water and transportation infrastructures: A sociotechnical approach. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 80, p.101166. [CrossRef]

- Raj Pokhrel, S., Chhipi-Shrestha, G., Mian, H., Hewage, K., Sadiq, R. (2023). Integrated performance assessment of urban water systems: Identification and prioritization of one water approach indicators. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 36, pp. 62-74. [CrossRef]

- Rasoulkhani, K., Mostafavi, A., Cole, J., Sharvelle, S. (2019). Resilience-based infrastructure planning and asset management: Study of dual and singular water distribution infrastructure performance using a simulation approach. Sustainable Cities and Society, 48, p.101577. [CrossRef]

- Ravadanegh, S., Jamali, S., Vaniar, A. (2022). Multi-infrastructure energy systems resiliency assessment in the presence of multi-hazards disasters. Sustainable Cities and Society, 79, p.103687. [CrossRef]

- Rentachintala, L., Reddy, M., Mohapatra, P. (2022). Urban stormwater management for sustainable and resilient measures and practices: A review. Water Science and Technology, 85(4), pp. 1120–1140. [CrossRef]

- Ro, B., Garfin, G. (2023). Building urban flood resilience through institutional adaptive capacity: A case study of Seoul, South Korea, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 85, p.103474. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M., Fu, G., Butler, D., Yuan, Z., Sharma, K. (2021). Exploring the spatial impact of green infrastructure on urban drainage resilience, Water, 13(13), p. 3131789. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, P., Beane, G., Garriga, R., Avello, P., Ellis, L., Fisher, S., Leten, J., Ruiz-Apilánez, I., Shouler, M., Ward, R., Jiménez, A. (2022). City Water Resilience Framework: A governance based planning tool to enhance urban water resilience, Sustainable Cities and Society, 77, p.103497. [CrossRef]

- Schoen, M., Hawkins, T., Xue, X., Ma, C., Garland, J., Ashbolt, N. (2015). Technologic resilience assessment of coastal community water and wastewater service options. Sustainability of Water Quality and Ecology, 6, pp. 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Sweetapple, C., Fu, G., Farmani, R., Butler, D. (2019). Exploring wastewater system performance under future threats: Does enhancing resilience increase sustainability?. Water Research, 149, pp. 448–459. [CrossRef]

- Tuptuk, N., Hazell, P., Watson, J., Hailes, S. (2021). A systematic review of the state of cyber-security in water systems. Water, 13(1), p.13010081. [CrossRef]

- United Nation World Water Assessment Programme (UN-Water). (2022). Strong systems and sound investments evidence on and key insights into accelerating progress on sanitation, drinking water and hygiene. The UN-Water global analysis and assessment of sanitation and drinking-water (GLAAS) 2022 report. Geneva: World Health Organization, [Online] Available at unwater.org, [Accessed 14/02/2023].

- United Nations World Water Assessment Programme (UN-Water). (2018). Nature-Based Solutions for Water. The United Nations World Water Development Report, Paris, UNESCO [Online] Available at unwater.org, [Accessed 14/02/2023].

- Valizadeh, N., Shamseldin, A., Wotherspoon, L. (2019). Quantification of the hydraulic dimension of stormwater management system resilience to flooding. Water Resources Management, 33(13), pp. 4417–4429. [CrossRef]

- Vercruysse, K., Dawson, D., Wright, N. (2019). Interoperability: A conceptual framework to bridge the gap between multifunctional and multisystem urban flood management. Journal of Flood Risk Management. 12(2), e12535. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2020). Resilient Water Infrastructure Design Brief. WB Official Website [Online] Available at reliefweb.int, [Accessed 01/01/2023].

- Yuan, F., Liu, R., Mao, L., Li, M. (2021). Internet of people enabled framework for evaluating performance loss and resilience of urban critical infrastructures. Safety Science, 134, p.105079. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., Yu, Y., Yang, S., Lv, Y., Sarker, M. (2022). Urban resilience for urban sustainability: Concepts, dimensions, and perspectives. Sustainability, 14(5), p.2481. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Zheng, F., Kapelan, Z., Savic, D., He, G., Ma, Y. (2020). Assessing the global resilience of water quality sensor placement strategies within water distribution systems. Water Research, 172, p.115527. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Huang, G. (2023). Towards flood risk reduction: Commonalities and differences between urban flood resilience and risk based on a case study in the Pearl River Delta, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 86, p.103568. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Hou, Q., Li, W. (2022). Spatial resilience assessment and optimization of small watershed based on complex network theory, Ecological Indicators, 145, 109730. [CrossRef]

- Zuloaga, S., Puneet, K., Vittal, V., Mays, L. (2021). Quantifying Power System Operational and Infrastructural Resilience Under Extreme Conditions Within a Water-Energy Nexus Framework, IEEE Open Access Journal of Power and Energy, 8, pp. 229-238. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).