Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Occurrence of Emerging Organic Contaminants in Drinking Water Systems

3.1. Pharmaceuticals

| Country | EOCs | Drinking Water System | Key results and Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Antibiotics (trimethoprim, sulfadimidine, sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole, sulfachloropyridazine, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin) | Groundwater | Antibiotics (0.44 -45.40 ng/L), at detection rates from 1.23%-95.06%. Contaminated groundwater with mixes of pharmaceuticals can act as potential drivers of antibiotic resistance in human beings | [20] |

| Zambia | Caffeine | Groundwater (shallow wells and boreholes) | Caffeine was detected in both shallow wells and borehole water at concentrations less than 0.17ng/L. The findings could not pose any risk but continuous exposure to the contaminant even at low concentrations is a cause for concern | [24] |

| China | Sulfamethoxazole | Tap water | The highest concentrations of 0.69 ng/L were detected. Detection frequencies ranged between 20–100% of sampled water. Water treatment methods failed to remove the EOCs. Long term exposure through ingestion is a concern for antibiotic resistance | [21] |

| China | Erythromycin, roxithromycin, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole, oxytetracycline, ibuprofen, and naproxen. | Drinking water sources | All 9 pharmaceuticals were detected with frequencies of 20–100% and concentrations of <LOQ–118.60 ng/L. Long-term ingestion and exposure to the compounds raises concerns about antibiotic resistance. | [48] |

| Malaysia | Dexamethasone, Primidone, Propranolol, Ciprofloxacin, Sulfamethoxazole, Diclofenac | Tap water and river water | Pharmaceuticals were detected in both river water and tap water. Dexamethasone (2.11ng/L), Primidone (2.99 ng/L), Propranolol (0.69 ng/L), Ciprofloxacin (8.69 ng/L), Sulfamethoxazole (0.90 ng/L), and Diclofenac (21.39 ng/L) detected in tap water. | [34] |

| Nigeria | Amoxicillin, acetaminophen, nicotine, ibuprofen, and codeine | Surface waters, groundwater samples (wells and boreholes) and drinking bottled water samples | Amoxicillin: 238, 358, and 1614 ng/L in groundwater, drinking water, and surface water. Detection frequencies for acetaminophen, codeine, ibuprofen, and nicotine exceeded 70%. Chronic exposure to these drug mixtures warrants more inquiry into the potential health consequences of such inadvertent exposure. | [45] |

| South Africa | Ibuprofen, caffeine, paracetamol, efavirenz, paraxanthine | Influent water, WWTP effluent water | The pharmaceuticals present in influent and effluent, with concentrations ranging from < ILOQ-14.2 μg L−1 and < ILOQ - 2.45 μg L−1, respectively. The maximum concentrations recorded in the effluent water including river water samples were for ibuprofen, (4.14 μg L−), caffeine (2.98 μg L−1), paraxanthine (1.22 μg L−1), and efavirenz (0.58 μg L−1). These findings show that the contaminants were not completely removed by the conventional water treatment methods. | [47] |

| South Africa | Antibiotics, antipyretics, atenolol, bezafibrate, and caffeine | river water | All the pharmaceuticals were present in discharged treated water (river water) with concentrations of most drugs below 10 μg/L. | [49] |

| South Africa | Naproxen, ibuprofen | treated effluent water | The compounds were detected with average concentrations in the treated effluent ranging from 10.7 - 24.6 µgl.-1 | [50] |

| South Africa | Antiretroviral drugs (ribavirin, famciclovir) | influent water, treated drinking Water | Both drugs were found in both influent water and treated drinking water. The concentrations of ribavirin and famciclovir in influent water were 19.60 ng/mL and 19.00 ng/mL, respectively. In treated water it was 0.042 ng/mL and 0.055 ng/mL, respectively. | [46] |

| China | Different pharmaceuticals (e.g., antibiotics, angiotensin ii receptor blockers, diuretics, anticonvulsants) | tap water | Detection frequencies exceeded 80%. 4-acetaminopyrine (48.16 ng/L), florfenicol (84.56 ng/L), hydrochlorothiazide (33.13 ng/L), irbesartan (38.35 ng/L), primidone (32.85 ng/L, thiamphenicol (101.54 ng/L), and valsartan (66.84 ng/L), | [32] |

| Czech Republic | Ibuprofen, carbamazepine, naproxen, and diclofenac | WWTP effluent | Detection frequency: ibuprofen > carbamazepine > naproxen > diclofenac. Concentrations: 0.5-20.7 ng/L. Sampling points were at public water systems that serve 50.5% of the Czech population, and this could pose health risks to over half of the population. | [37] |

| Germany | Diclofenac | river water samples | Detected in 10 out of 27 water samples in concentrations of up to 15 μg/L. The concentrations are very low not to cause pharmacological effects in man but continuous exposure could have some potential risks. | [39] |

| Germany | Clofibric acid, Ibuprofen, Gemfibrocil, Fenoprofen, Indomethacin, Ketoprofen and Sarkosin-N-(phenylsulfonyl) (SPS) ng/L | pond and river water samples | At least one of the compounds was detected in 25 of 27 water samples in ng/L. The most frequently detected substance was SPS. Most are excreted after oral intake and were mostly found in rivers with direct connection to sewage plants. | [39] |

| Malaysia | Ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin | drinking water | Ciprofloxacin was found at the greatest quantity (0.667 ng/L), whereas amoxicillin was found at the lowest (0.001 ng/L). The long exposure through consumption of such water has potential risks | [33] |

| Hungary | Pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) | tap water | 19 PhACs were detected in tap water samples with a total mean concentration exceeding 30 ng L−1 only at 5 sites. The frequently detected PhAC, carbamazepine (54 % of the samples) had 8.9 ng L−1 as the mean concentration. Travel distance between drinking water wells decreased the PhAC concentrations. | [35] |

| Brazil | Pharmaceutically active compounds | surface and drinking water samples | Trace concentrations detected. Betamethasone, fluconazole, and prednisone, were most frequent, and had the greatest concentrations. Some PhACs were linked to significant toxicological hazards; as a result, such water consumption could be harmful to people's health. | [36] |

| China | Ibuprofen | tap water | The highest concentrations of 1.28 ng/L were detected. Detection frequencies ranged between 20–100% of sampled water. | [21] |

| Pakistan | Ibuprofen | ground water | Detected at 154 ng/L. Domestic wastewater discharge, hospital waste, and animal husbandry have all been identified as major sources of groundwater contamination. | [28] |

| Colombia | Ibuprofen | water reservoirs | Ibuprofen was detected in almost 60% of the reservoir water samples. The analgesic was still present in the treated water from the reservoir but at low doses (40 ng/L). Conventional treatment methods cannot remove all the EOCs. | [38] |

| China | Psychiatric pharmaceuticals (carbamazepine, diazepam, oxazepam, lorazepam, and alprazolam) | River water; treated water | Oxazepam, diazepam, lorazepam, and carbamazepine were at ng L−1 -75.5 ng L−1 in river water. Alprazolam (2.3 ng L−1), diazepam (0.5–3.2 ng L−1), and carbamazepine (0.8–2.5 ng L−1) were detected in treated water. | [29] |

| Brazil | Caffeine | drinking water | Caffeine concentrations in drinking water ranged from 1.8 ng L− 1 to 2.0 μg L− 1, while source water concentrations were at 40 ng L− 1 - 19 μg L− 1. Since caffeine is a substance with anthropogenic origins, its presence in treated water shows that domestic sewage was present in the source water. | [30] |

| Poland | Antidepressants (citalopram, mianserin, sertraline, moclobemid and venlafaxine) | tap water | citalopram (≤1.5 ng/L), moclobemid (≤0.3 ng/L), sertraline (<3.1 ng/L), mianserin (≤0.9 ng/L), and venlafaxine (≤1.9 ng/L). Their presence in tap water demonstrates an insufficient removal in the drinking water treatment facility and this could have long-term consequences, since pharmaceutical pollutants can synergize. | [31] |

| United Kingdom | Pharmaceutical of abuse (Fluoxetine, methamphetamine, ketamine) | drinking water | Concentration was between 0.14 and 2.81 ng/L. Since the presence of these pharmaceuticals has an impact on public health, identifying them is crucial when examining water quality. | [51] |

| Uganda | Various pharmaceuticals | surface water, and groundwater samples | Detected in water samples with concentrations similar to previous documented studies in SA. | [52] |

| Uganda | Ampicillin and benzylpenicillin | shallow groundwater | Both antibiotics were detected although at low concentrations to cause direct harm to human health. However, chronic exposure could lead to a proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes. | [53] |

| Kenya | pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) | groundwater wells | Fourteen PhACs were detected. Anti(retro)virals, were more prevalent PhACs, with nevirapine concentrations ≤700 ng/L. | [54] |

| Zimbabwe | Topiramate, thiabendazole-13C6, p-hydroxynobenzphetamine-2TFA, 4-imadazolidinone, and 5-(phenylmrthyl)-2-thioxo | river water and sediment | Topiramate was detected in river water, whilst the other drugs were found in the river sediment. The concentration of pharmaceuticals especially in sediments was at 0.01 to 0.29 mol/µl. | [55] |

3.2. Personal Care Products

| Country | EOCs | Drinking Water System | Key Results and Remarks | References. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal care products | ||||

| Brazil | Triclosan and bisphenol A | drinking water, source water | Bisphenol A and Triclosan detected in at least one sample. | [30] |

| Brazil | Methylparaben | drinking water, surface water | Detected at concentrations ranging from 15 up to 840 ng L-1 in surface waters. In tap water methylparaben was at 17 ng L-1. The treatment significantly reduced the concentration but still, chronic exposure to tap water may have potential risks. | [56] |

| Colombia | Methyl paraben, benzophenone | reservoirs for drinking water treatment plants, treated water samples | Both compounds detected in raw. Both compounds were still present in the samples although at low concentrations (<40 ng/L) in treated water. This shows they persisted after treatment. | [38] |

| South Africa | Triclosan | treated effluent water | The compound was detected with an average concentration ranging from 10.7 - 24.6 µgl.-1. The compound was not completely removed during the wastewater treatment processes. | [50] |

| Malaysia | Triclosan and Bisphenol A | drinking water supply system (tap water) | Bisphenol A (66.40 ng/L) and triclosan (9.74ng/L) in tap water. These findings show that the conventional water treatment methods were not effective in removing all the contaminants. | [34] |

| China | Propylparaben, bisphenol A, dicyclohexylamine, | tap water | Detection frequencies were over 80% and concentrations of 47.50 ng/L, 31.51 ng/L, and 42.33 ng/L, respectively. | [32] |

| Kenya | Methylparaben and other PCPs | groundwater wells | Five PCPs detected. Methylparaben was the predominant at ≤10 μg/L. | [54] |

| Musks and fragrances | ||||

| USA | tonalide (AHTN) galaxolide (HHCB) |

bottled water, tap water, WWTP, surface water |

All the contaminants detected in the water samples, AHTN (490 ng/L) and HHCB (82 ng/L). | [57] |

| USA | tonalide (AHTN) galaxolide (HHCB) |

river water | HHCB (1 - 20 ng L−1), AHTN (0.5 -10 ng L−1). Both contaminants showed weak estrogenic activity in human cells. |

[58] |

| Serbia |

HHCB | drinking water | The highest concentration of 90 ng/L was found in drinking | [59] |

| China | celestolide (ADBI), phantolide (AHMI), AHTN, traseolide (ATII), HHCB |

tap water | All the contaminants were found to range in concentration from 0.3– 2.1 ng/L. The EOCs can bioaccumulate and have eco-toxicological effects on specific organisms, as well as cause endocrine disruption in humans. | [60] |

| China | AHTN, HHCB |

river water | HHCB (18.7ng/L) and AHTN (11.7 ng/L) were found in the water samples. | [60] |

| Portugal | Cashmeran, ADBI, HHCB, Musk Ketone, Musk xylene, AHMI, AHTN, ATII | drinking water | All chemicals detected in the range of ng/L–μg/L. Exposure to some of the contaminants is linked to diseases such as cancer, cognitive disorders in children, asthma, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and infertility. | [61] |

| Germany | HHCB, AHTN, HHCB-lactone |

surface water | About 60 ng L−1 (HHCB), 10 ng L−1 (AHTN) and 20–30 ng L−1 (HHCB-lactone) were found as typical riverine concentrations. | [62] |

| France | Tonalide (AHTN) | tap water, water reservoirs, borehole water |

Less than 1ng/L of the pollutant was detected in the water samples. | [63] |

| Ultraviolet (UV) or sunscreening agents or UV blockers/filters | ||||

| Spain | UV filters: 2-ethylhexyl 4-(dimethylamino) benzoate (OD-PABA), benzophenone-3 (BP3), 2-ethylhexyl 4-methoxycinnamate (EHMC), octocrylene (OC), and 3-(4-methylbenzylidene) camphor (4MBC) | tap water, clean waters | All UV filters were detected in all water samples. There were low detection limits for clean waters (0.02 - 8.42 ng/L). Maximum concentrations were detected in tap water: BP3 (290 ng/L), 4MBC (35 ng/L), OD-PABA (110 ng/L), EHMC (260 ng/L), and OC (170 ng/L). | [64] |

| Spain | UV filters | groundwater | 20- 55 ng/L. | [65] |

| Spain | UV filter benzophenone-4 (BP-4) | surface water, drinking water | The compound was detected in the 20–200 ng L−1 range. The findings show that the contaminant was not removed by conventional methods. | [66] |

| Brazil | UV filters: octocrylene (OC), ethylhexyl salicylate (ES), (benzophenone-3 (BP-3), and ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate (EHMC) | raw water, drinking water (treated and chlorinated water) | All compounds were detected, but only BP-3 (18-115 ng L−1) and EHMC (55 to 101 ng L−1) were quantifiable. | [67] |

| Zambia | Homosalate, Octocrylene |

Groundwater (shallow wells and borehole water) | The compounds were found at low concentrations, Homosalate (0.05ng/L) and Octocrylene (0.04ng/L). Chronic exposure to such waters especially through ingestion might pose potential health risks. | [24] |

| Country | EOCs | Drinking Water System | Key Results and Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasticizers | ||||

| Pakistan | Different types of plasticizers | drinking water | 30 types of plasticizers detected in drinking water. Hence, there is a need for regular monitoring of water quality. | [68] |

| Malaysia | 4-octylphenol | drinking water supply system | 0.44 ng/L detected in tap water. | [34] |

| Spain | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate and phthalate esters | tap water, commercial mineral water, river water | The compounds were detected and their limits of detection were between 0.006 and 0.17 μg l−1. | [69] |

| Mexico | Phthalic acid esters | bottled water | PAEs detected in bottled water. The dominant pollutant was dibutyl phthalate at 20.5-82.8 μg L−1. 0.7 < LOD < 2.4 μg L−1. |

[70] |

| Jordan | Phthalates (dibutyl-, di-2-ethylhexyl- and di-n-octyl-phthalate) | bottled water | The water was contaminated with dibutyl-, di-2-ethylhexyl- and di-n-octyl-phthalate, with total phthalate concentrations between 8.1 and 19.8 µg/L. Increasing the storage temperature of the bottled water increased the content of leached phthalates in the water (total concentration of 23–29.2 µg/L). | [71] |

| Saudi Arabia | Dialkyl phthalates | PET bottled water samples | The six phthalates at concentrations between 6.3 and 112.2 ng mL−1 were detected. The highest level was observed for di-n-butyl phthalate, followed by DEHP, DiBP, DMP, DEP and DiPP. LOD of detection was in the range between 0.3 and 2.6 ng mL−1. Phthalate residues leach from PET bottles into water and prolonged consumption of such waters is a public health concern | [72] |

| India | Phthalate esters | PET bottled water | Phthalate esters in bottled water, 0.03< LOD < 0.08 nmol L−1. Consumption of PET bottle-stored water or drinks is a cause for concern since PEs tends to exhibit endocrine disruption. | [73] |

| India | Bisphenol A | plastic-bottled water and household water tanks | LOD = 0.46 pg/mL and LOQ = 1.52 pg/mL. Bisphenol A traces detected in plastic-bottled water with concentrations ranging from 60-90 pg/mL. In plastic water tanks it was nondetectable-12 pg/mL. Consumption of bottled and storing water in plastic tanks may have a bad impact on humans since they can also interfere with reproductive systems. | [74] |

| South Africa | Total plasticizers | bottled water, drinking water treatment plants | Total plasticizers in the water. The frequent detection of these substances in drinking water calls for additional research into their environmental and public health impacts. | [75] |

| Kenya | Plasticizers | surface water (Lake Victoria) | Plasticizers were found in the surface water systems with concentrations of up to 6.5 μg L−1. The pollutant revealed high chronic and acute risk for toxicity in crustaceans, and the same can be true in humans. | [76] |

| Zambia | 1,6-Dioxacyclododecane-7,12-dione, Bis (4-chlorophenyl) sulfone, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, Bisphenol A, Cyclohexanone, Diisobutyl phthalate , Diethyl phthalate, Dimethyl phthalate, N-butyl Benzenesulfonamide, Triphenyl phosphate, |

groundwater (shallow wells and boreholes) | The contaminants were detected in both water systems at 0.03 - 34 ng/L. The findings indicate that the contaminants are capable of leaching from the various sources into the ground water drinking sources | [24] |

| Surfactants | ||||

| South Africa | 4-nonylphenol (NP) | water samples from boreholes, shallow wells and surface water | NP in water samples. The presence of NP in water samples might pose ecotoxicological risks to aquatic life as well as communities. | [77] |

| Brazil | linear alkylbenzene sulfonate (LAS) and its metabolite, sulfophenyl carboxylates | drinking and surface waters | The LAS concentrations in river water ranged between 14 and 155 μg l−1 and the levels of their metabolic intermediates were found from 1.2 to 14 μg l−1. LAS levels detected in the drinking water ranged between 1.6 and 3.3 μg l−1. The self-purification capacity of the water was demonstrated by the degradation of LAS in river water but still it was present even in drinking water. | [78] |

| Philippines | alkylbenzenesulfonates (ABS) and linear alkylbenzenesulfonates (LAS) | water source (freshwater lake) | Concentrations of ABS (1.1–75 and 1–66 μg L−1) and LAS (1.2–73 and 2.2–102 μg L−1) were detected in the tributaries. | [79] |

| Spain | non-ionic surfactants, linear alkylbenzene sulfonates (LASs) and alkyl ethoxysulfates (AESs) | wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), drinking-water treatment plants (DWTPs) | Non-ionic surfactants were detected in raw waters (0.2 -100 μg L−1) , effluents (0.1 to 5 μg L−1). LASs and AESs found in all waters. Up to 32,000 μg L−1 of AESs and 3900 μg L−1 of LASs in WWTP feed; up to 114 μg L−1 of AESs and 25 μg L−1 of LASs in DWTPs. Thus conventional treatment processes are inadequate. |

[80] |

| Flame retardants | ||||

| China | Organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs) | water sources, DWTPs, tap water | OPFRs were detected at 9.25 - 224.74 ng/L. A reduction in concentration was noted in treated water. Residuals and the potential risk of OPFRs is concerning. | [81] |

| Korea | OPFRs | tap water, purified water, and bottled water | Predominant OPFRs detected were tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate, tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate, and tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate. | [82] |

| China | OPFRs | tap water | tap water (85.1 ng/L - 325 ng/L), and triphenyl phosphate (TPP), tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP), and tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP) were predominant. | [83] |

| Spain | OPFRs | influent waters | Detected in influent waters at levels of 0.32–0.03 μg L−1. Efficient technologies should be developed to remove the compounds during water treatment. | [84] |

| South Africa | Brominated flame retardants (BFRs) | river water | Both BFRs were detected in Jukskei River water. | [85] |

| Pakistan | OPFRs, dechlorane plus (DP), polybrominated diphenylethers (PBDEs), and novel brominated flame retardants (NBFRs) | potable water in industrial and rural zones | FRs were detected with concentrations of OPFRs (71.05 ng/L), PBDEs (0.82 pg/L), NBFRs (1.39 pg/L) and DP (0.29 pg/L) in both zones. However, consumers of the water were found to be at low risk of FRs exposure through potable water consumption. | [86] |

| Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) | ||||

| Malaysia | Hormones, diethylstilbestrol |

river water and tap water | The drinking water supply system was observed to contain testosterone, progesterone, estrone, 17α-ethynylestradiol, and 17β-estradiol, with respective concentrations in the tap water of 2.52ng/L, 0.92 ng/L, 3.42 ng/L, 6.34 ng/L, and 11.68 ng/L. | [34] |

| South Africa | dichlorophenol (DCP), bisphenol A (BPA), 17β-oestradiol (E2) octylphenol (OP) |

freshwater, wastewater and treated effluents | Detected in concentrations of 0.127 and 0.261 μg/L for DCP. BPA present in all samples at 1.684 μ/L - 1.468 μg/L. E1 and E2 were detected in most samples at 0.135 μg/L - 1.06 μg/L, and OP at 1.683 μg/L. | [48] |

| Nigeria | 2,4-dinitrophenol, 2-nitrophenol, bisphenol A, 2,4-ichlorophenol, nonylphenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol | shallow ground water sources | 2-nitrophenol (0.0077ppm), 2,4- dinitrophenol (0.0554 ppm), 2,4-dichlorophenol (0.0111 ppm). |

[87] |

| Nigeria | bisphenol A (BPA), 4-nonylphenol (NP), and 4-tert-octylphenol (OP) | surface water (River) | BPA (1.20 - 63.64 μg/L), NP (< 0.20 - 2.15 μg/L) and OP (< 0.10 - 0.68 μg/L) were all detected in river water. | [88] |

| Morocco | nonylphenol, 2-phenylphenol, 4-tert-octylphenol, 4-phenylphenol, estrone, 17β-estradiol, triclosan, and bisphenol A |

River water | All the EDCs detected at 2.5 - 351 ng/L in all samples | [89] |

| USA | carbamazepine, iodinated contrast media, -blockers, antibiotics | Waste water, Tap water |

All the pollutants detected. The occurrence of the compounds especially in tap water shows that the traditional water treatment methods used failed to completely remove all the contaminants. | [90] |

| South Africa | bisphenol A, nonylphenol, di(2-ethylhexyl) adipate, dibutyl phthalate, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, diisononylphthalate, 17β-estradiol, estrone, and ethynylestradiol | municipal drinking water | EDCs detected at distribution point water samples with EEq values ranging from 0.002 - 0.114 ng/L. | [91] |

| South Africa | Estradiol | influent water, WWTP effluent water (river water) | The compound was detected in both influent and effluent water (river water). The maximum concentrations recorded in river water samples was 2.45 μg L−1. | [47] |

| South Africa | bisphenol-A (BPA), estradiol | drinking bottled water | Estrogenic activity of the bottled water samples was detected at 20 °C and 40 °C. Equivalents of estradiol (0.001- 0.003 ng/L) and BPA (0.9 ng/L - 10.06 ng/L) were found. However, the concentrations of drugs posed an acceptable risk for a lifetime of exposure. | [92] |

| Mexico | ethylbenzene, 2-chlorophenol | groundwater, surface water | The concentration of the compounds ranged from ng/L to 140 mg/L. | [93] |

| France | carbamazepine, iodinated contrast media, -blockers, antibiotics diethylstilbestrol |

tap water | Concentrations in the ng/L range were detected. Exposure to such waters via consumption is associated with abnormalities in the structure and function of reproductive organs. | [94] |

| China | Lindane, heptachlor epoxide | ground water, surface water, tap water | Both compounds detected in concentration ranging from 0.17–860 ng/L and 0.11–10 ng/L. The compounds can bioaccumulate and magnify along the food chain with a huge impact on top predator species, including humans. |

[95,96] |

| United Kingdom | Nonylphenol Estrone (E1), and Estradiol (E2) |

municipal wastewater |

The EDCs were detected in concentrations of nonylphenol (1.2–2.7ng/L), E1 (15–220ng/L), and E2 (7–88ng/L). The EDCs cause feminization in fish in sewage treatment as they can mimic estrogenic even to non-target species. The same can impact humans. | [97] |

| Germany | Nonylphenol Estrone (E1) Estradiol (E2) |

drinking water, surface water |

Significant amounts of nonylphenol (8 ng/L), E1 (0.4 ng/L) and E2 (0.3 ng/L). An increase in vitellogenin levels, as well as the number of eggs produced by Pimephales promelas was observed. The same impact can affect humans through the ingestion of contaminated water. |

[98] |

| Zimbabwe | oestrogenic and androgenic chemicals | dam water (Umguza and Khami) | the contaminants were detected in both dam waters and were expressed as 17β-oestradiol equivalent (EEq), with concentrations as high as 237 ng l–1. | [99] |

| Tanzania | endocrine disrupting estrogens (ethinylestradiol, estrone and estradiol) | dam and river water | The presence of estrogens in the waters was revealed, with levels ranging from non-detectable levels to 16.97 ng/L. The detected concentrations, as reported in previous literature, were not significant enough to cause adverse health effects to humans. | [100] |

| Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances | ||||

| China | PFAS | water source, DWTPs, and tap water | Concentrations: 13.4 ng/L - 17.6 ng/L. This highlights that PFAS are present in the treatment train and effective removal technologies should be employed. | [52] |

| Sweden | PFAS | ground water aquifer, surface water, drinking water. | PFAS detected in all water samples. For example, in surface water PFAS concentration reached 15 ng L−1 while ranged between 1 ng L−1 and 8 ng L−1 in drinking water. Water treatment reduced the concentration of PFAS. | [101] |

| USA | PFAS (e.g., Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA)) | drinking water | 14 PFAS were detected in drinking water. For example, maximum concentrations of 268 ng/L for PFHxA, 213 ng/L for PFOA, and 75.7 ng/L for PFHpA were recorded. PFOA, perfluorodecanoic acid, and PFHpA were each detected in at least one drinking water sample at concentrations > 20 ng/L. | [102] |

| USA | Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), Perfluorobutanoic acid, and Perfluorononanoic acid |

groundwater, surface water. and tap water | The contaminants were detected in all the water samples in a concentration ranging from 5–174 ng/L. PFAS can disrupt the female reproductive system by altering menstrual cycle, hormone secretion, and fertility. | [103,104] |

| China | Perfluorocarboxylic acids and Perfluorosulfonic acids | tap water | PFAS in the concentration ranged between 4.10 and 17.6 ng/L were detected in the water samples. | [32,52] |

| South Africa | Perfluorosulfonic acids, perfluorocarboxylic, Perfluoro-n-decane sulfonic acid, perfluoro-n-heptyl sulfonate |

surface water | The contaminants were detected in the range 0.14–89.04 ng/g. Single or mixtures of PFAS causes female reproductive tract dysfunction and disease. |

[105] |

| Uganda | perfluorohexanesulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) |

drinking water reservoir (Lake Victoria). | PFOA and PFHxS were detected in the drinking water reservoir | [106] |

| Ethiopia | PFAS | surface water (river, lake) | Found at concentrations ranging from 0.073- 5.6 ng /L. | [107] |

| Ghana | perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, perfluoroalkane sulphonic acids |

river water, tap water | Both contaminants were found at concentrations between 281 and 398 ng/L in river water and between 197 and 200 ng/L in tap water. | [108] |

| Gasoline additives | ||||

| Italy, Belgium, and Luxembourg |

ethyl-tert-butylether (ETBE), methyl-tert-butylether (MTBE) | surface water, ground water, and tap water |

All the contaminants were detected in all the drinking water samples with concentration ranging from 10 - 100 ng/L. ETBE and MTBE are recalcitrant to treatment and their exposure via ingestion is very high, hence its risks may be also high. | [3] |

| USA | MTBE | groundwater, municipal drinking water supplies, private wells, and reservoirs. |

The pollutant was detected at concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 20 μg/L. Its complete removal requires more time, complicated and expensive treatment technologies. | [109] |

| Dutch | MTBE, methyl-tert-amyleter (TAME), and ETBE |

Groundwater and surface water | MTBE concentrations below 0.1 μg/L were detected. | [110] |

| Artificial food sweeteners | ||||

| USA | Sucralose | drinking water treatment plants | Sucralose detected in finished water samples. | [111] |

| Germany | Cyclamate, Acesulfame, saccharin, sucralose |

wastewater treatment plant | Detected in influents of the sewage treatment plants i.e., 190 μg/L for cyclamate, 40 μg/L for acesulfame and saccharin, and less than 1 μg/L for sucralose. | [112] |

| Switzerland | Acesulfame | surface water, ground water, and tap water |

Detected in influent and effluent (12−46 μg/L). The contaminant was not removed during treatment. Persistent concentrations in surface water samples, whilst groundwater concentrations of up to 4.7 μg/L. |

[113] |

| Switzerland | acesulfame, saccharin, cyclamate and sucralose. | surface water, tap water. | Saccharin and cyclamate were present in raw water for treatment but absent in tap water. Acesulfame ≤ 0.76 μg L−1 in tap water. | [114] |

| Switzerland | aspartame, acesulfame (ACE), neohesperidine dihydrochalcone, saccharin (SAC), neotame, cyclamate (CYC), and sucralose (SUC) | surface water, groundwater, and drinking water | The contaminants were detected in all water samples. ACE ≤ 7 μg/L and SUC ≤ 2.4 μg/L were detected in tap water. | [115] |

| Canada | Acesulfame, saccharin |

groundwater, |

All pollutants were detected but acesulfame was μg/L scale. | [116] |

| Food colourants or dyes | ||||

| Poland | Crystal violet, methyl violet 2 B, rhodamine B |

water reservoirs | Detected in the following concentrations: methyl violet 2 B (0.0571 μg/L), crystal violet (0.0122–0.0209 μg/L), rhodamine B (0.0594 μg/L). |

[117] |

| Poland | crystal violet, rhodamine B, and methyl violet | water reservoirs | Concentrations: 0.017 - 0.0043 μg/L. The contaminants have carcinogenetic, mutagenic and teratogenic properties. | [117] |

| Brazil | C.I. Disperse Blue 373, C.I. Disperse Orange 37 and Disperse Violet 93 | treated industrial effluent, raw river water, treated river water | The dyes were detected in concentrations ranging from 1.65 - 316ng/L. Water treatment processes failed to completely remove the dyes. |

[118] |

3.3. Plasticizers

3.4. Surfactants

3.5. Flame Retardants

3.6. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

3.7. Gasoline Additives

3.8. Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances

3.9. Artificial food Sweeteners

3.10. Food colourants or Dyes

3.11. Ultraviolet or Sunscreening Agents or UV Blockers

3.12. Musks and Fragrance

3.12. Disinfection by-Products

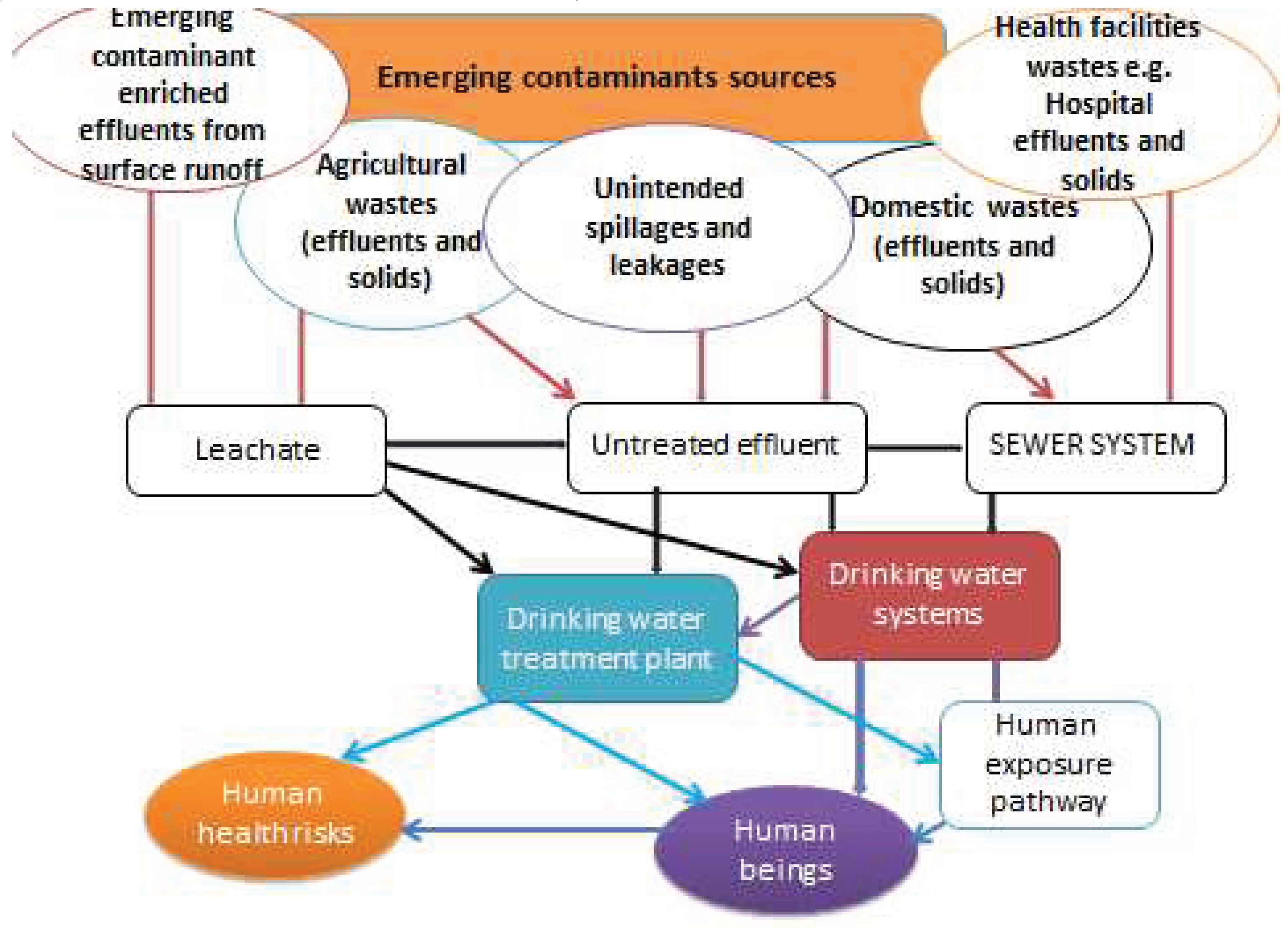

4. Behaviour and Fate

5. Human Exposure Risks

5.1. Risk Factors and Behaviours

5.2. High-risk Environments

5.3. Human Exposure Pathways

6. Human Health Risks

6.1. Evidence of Human Health Risks

| Type of EOC | Organism | Concentrations | Major Findings and Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pharmaceuticals | ||||

| sulfonamides | humans | 20.06 μg/L- 1281.50 μg/L | Human health risk for age groups less than 12 months was reported. | [218] |

| Chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, sulfapyridine, doxycycline, enrofloxacin, florfenicol, levofloxacin, metronidazole, norfloxacin, sulfamethoxazole | humans | 0.5 -21.4 ng/L | Resistance election. | [219] |

| estrogen and sulfapyridine | Human | 0.09 - 304 ng/L | -Resistance selection. | [220] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Human | -Ciprofloxacin resistance. | [221] | |

| Bromate, perchlorate and chlorate | Human | -A potential cancer risk. | [222] | |

| fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, macrolides, phenicols, sulfonamides, tetracyclines | Human | concentrations at 0.0064 ng/mL -0.0089 ng/mL | -Accumulations in the body and detected in the urine. | [223] |

| 30 common antibiotics | Humans | 226.8~498.1ng/L | - The non-carcinogenic risk of different groups of people was reported. | [224] |

| 2. Personal care products | ||||

| Cyclic siloxanes D4(octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane) and D5 (decamethylcyclopentasiloxane) (personal care products) | Humans | -Affects the liver and also induces liver cell enzymes. -Primary target organ for D5 exposure by inhalation is the lung. |

[225] | |

| Nitro Musk (personal care products) | Humans | 5-10mmol/litre in surrounding media | Competitive binding capability to estrogen receptors. | [226] |

| Fragrances (personal care products) | Human | Facial dermatitis. | [227] | |

| Glycol ether (personal care products) | Human | Motile sperm count and infertility. | [228] | |

| Glycol ether metabolites (personal care products) | Human | Negative impact on the neurodevelopment of infants and children. | [229] | |

| Insect repellents (personal care products) | Human | Cause vomiting. | [230] | |

| Butylparaben & propylparaben (Personal care products) Parabens |

Human | Adverse birth outcomes decreased gestational age birth weight & body length of neonates. | [231] | |

| Methylparaben & propylparaben (personal care products) Parabens | Human | Increases gestational age. | [232] | |

| 3. Plasticizers | ||||

| plasticizers | Humans | 13.42–265.48 ng/L | -potential cancer risk. | [198] |

| Polyethylene terephthalate bottles | 0.046 and 0.71 μg/L | - Carcinogenic risk of 2.8 × 10−7. | [233] | |

| Plasticizers | Humans | Bio accumulation in the blood plasma and urine | [234] | |

| 4. Surfactants | ||||

| Alkyl sulfates (AS), linear alkylbenzene sulfonates (LAS), alcohol ethoxylates (AE), alkyl phenol ethoxylates (APE), alcohol ethoxy sulfates (AES), alpha olefin sulfonates (AOS) and secondary alkane sulfonates (SAS) | adult vertebrates | 1 to 20 mg/L. | -Acute toxic effects in adult vertebrates. -Acute oral toxicity to occur at doses of 650 to > 25,000 mg/kg. -No evidence for carcinogenic, mutagenic. |

[235] |

| 5. Flame retardants | ||||

| OPFRs | humans | 85.1 ng/L -325 ng/L, | - OPFRs in drinking water did not pose a major health concern for adults and children. | [83] |

| Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) | Humans | -Rapidly bioaccumulating-doubling every two to five years. | [236] | |

| Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) | humans | median: 48.7 ng/L | estimated daily OPFRs intake was less than the oral reference dose values. | [82] |

| triphenyl phosphate, tris(1,3-dichloropropyl) phosphate | humans | 1.1 ng/mL and 1.2 ng/mL |

- endocrine-disrupting, reproductive toxins, carcinogens, neurotoxins -Flame retardants were detected in all urine samples, suggesting bio- accumulation. |

[237] |

| Organophosphate esters (OPEs) | humans | 13.42–265.48 ng/L | -potential cancer risk (>1.00E-6), no non-carcinogenic effects (<1). -Total OPEs in advanced DWTPs were much lower than those in conventional DWTPs. Relative to conventional DWTPs, advanced DWTPs removed approx. 65.6% and 36.5% of the carcinogenic risk and non-carcinogenic risk of OPEs, respectively. |

[32] |

| Flame retardants (FRs) | humans | Upto 71.05 ng/L | -The estimated daily intake (EDI) for all FRs was higher in children than adults. Both children and adults were at low risk (HQ < 1) | [86] |

| Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) | humans | EDI through drinking water was ≤9.65 ng/kg body weight/day. | [238] | |

| 6 Endocrine disrupting chemicals | ||||

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | human | 0.4 to 25.5 μg/L | -Caused oocyte aneuploidy and reduced production of oestradiol decreased ovarian response including decreased peak oestradiol levels, decreased number of oocytes retrieved decreased pregnancy rates. |

[239] |

| BPA | human | <LOD to 65.3 μg/L. | -Unexplained infertility was present in 29% of the subjects decrease in peak oestradiol. |

[240] |

| 7. Gasoline additives | ||||

| MTBE | humans | 8 μM MTBE | -Insulin formed a molten globule -like structure. This shows MTBE promotes protein oxidation and the production of reactive oxygen species. | [241] |

| 8. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | ||||

| Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | Human (human liver HepaRG cell line) | concentrations of 40−50 ng/L | -No significant alterations in its activity were observed. | [242] |

| 9. Artificial food sweeteners | ||||

| Artificial sweeteners | human | 0.5-25 ng/L | -ASWs in groundwater did not appear to pose human a health risk. | [2] |

| Artificial sweeteners | human | Upto 21 µg/L | -Bio- accumulation detected in human waste. | [243] |

| 10. Food colourants or dyes | ||||

| tartrazine | human | 1 - 50 mg | -Irritable and restless and had sleep disturbance. | [244] |

| 11. Ultraviolet sunscreening agents or UV blockers/filters | ||||

| Benzophenone-3 (BP-3) | humans, rats | -Decline in male birth weight and decreased gestational age in humans. -Decrease in epididymal sperm density and a prolonged oestrous cycle for females were observed in rats. |

[245] | |

| Benzophenone-3 | human breast epithelial cells, | 1μM -5μM BP-3 |

-DNA damage in epithelial cells. | [246] |

| UV-B filter octylmethoxycinnamate (OMC) | human | 1, 10, and 50 μmol/L | -A decrease in vasorelaxation of human umbilical arteries was revealed. Possibility of OMC acting as an inductor of pregnancy hypertensive disorders. | [247] |

| 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone; 4-methylbenzylidene camphor; 2-ethylhexyl 4-methoxycinnamate; and butyl-methoxydibenzoylmethane, | human macrophages | -mRNA expression of cytokines up-regulated. UV filters may alter the immune system functions of humans and may lead to the development of asthma or allergic diseases. | [248] | |

| Type of EOC | Organism | Concentrations | Major Findings and Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal care products | ||||

| Cyclic siloxanes D4(octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane) and D5 (decamethylcyclopentasiloxane) (personal care products) | rats | -D4 is considered to impair fertility in rats. | [225] | |

| Musk ambrette, musk ketone and musk xylene | Rats and mice | dose level of 0.5 mg/kg (11 μg/cm2 of skin) | - Affects liver tissues. | [249] |

| Flame retardants | ||||

| Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) | mice | -Rapidly bioaccumulating-doubling every two to five years. | [236] | |

| Endocrine disrupting chemicals | ||||

| Estradiol benzoate Aroclor 1221 PCBs |

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats | 50 μg/kg | -Irregular oestrous cycles. | [250] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | mice | 1μg /kg to 10 mg /kg | -Number of primordial follicles in the primordial follicle pool decreases significantly. | [251] |

| Estradiol and diethylstilbestrol | mice | 0.02, 0.2, and 2.0 ng/g of body weight | -Prostate weight first increased then decreased with dose, resulting in an inverted-U dose-response. | [252] |

| Gasoline additives | ||||

| MTBE | mice and rats | -Cause testicular, uterine, and kidney cancer, as well as harm the kidney, immune system, liver, and central nervous system. | [119] | |

| MTBE | Sprague- Dawley rats | 1000, 250, or 0 mg/kg b.w | -The contaminant caused an increase in Leydig interstitial cell tumors of the testes and a dose-related increase in lymphomas and leukemias in the female rats. | [253] |

| Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | ||||

| PFOA, PFOS or N-EtFOSE | rats and mice | Injection at 100 mg/kg | -Decrease cytochrome oxidase activity in liver tissue. -Hepatomegaly as indicated by the increase in liver weight. |

[254] |

| PFOA | mice | 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg body weight orally | -Trigger inflammatory markers e.g, HGF, IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α, and hepatic enzymes ALT and AST. | [255] |

| Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | Mice | 1, 3, 5 or 10 mg/kg | -Could not carry their pregnancy successfully. -The majority of the PFNA-exposed pups survived a few days longer after birth. |

[256] |

| Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | Mice | exposed orally to 0.3 mg PFOA/kg/day | -Showed increased femoral periosteal area as well as decreased mineral density of tibias. | [257] |

| Artificial food sweeteners | ||||

| Artificial sweeteners | Mice | maximum Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) ad libitum | -Increased body weight; food intake remained unchanged. | [258] |

| Artificial sweeteners | Mice | -Development of glucose intolerance through the induction of compositional and functional modifications to intestinal microbiota. | [259] | |

| Artificial sweeteners | rat | aspartame (3 mg/kg/day) or saccharin (3 mg/kg/day) or sucralose (1.5 mg/kg/day) | -Chronic intake of sweeteners significantly impaired PAL performance, lowered neuronal count in aspartame and increase Brain lipid peroxides. | [260] |

| Food colourants or dyes | ||||

| Amaranth, Sunset Yellow, Curcumin | Rats | an oral dose of 47-157.5 mg/kg | -Significantly decreased the weight of the thymus gland, a significant decrease in neutrophils and monocytes and a compensatory increase in lymphocytes. | [261] |

| Tartrazine and carmoisine, saccharin | Rats | -Alter biochemical markers in vital organs e.g. liver and kidney not only at higher doses but also at low doses | [262] | |

| Carmoisine, | Rats | 100 -1200 mg/kg body weight | -Increased incidences of adrenal blood/fibrin cysts or internal hyperplasia/medial hypertrophy of the pancreatic blood vessels and reduced body-weight gain. |

[263] |

| Ultraviolet sunscreening agents or UV blockers/filters | ||||

| Benzophenone-3 | mice | 1μM -5μM BP-3 |

R-loops and DNA damage were also detected in mammary epithelial cells of mice. | [246] |

| Benzophenone-3 | rats | BP-3 raised oxidative stress and induced apoptosis in the brain, as well as impaired spatial memory. | [264] | |

6.1.1. Pharmaceuticals

6.1.2. Personal Care Products

6.1.3. Plasticizers

6.1.4. Surfactants

6.1.5. Flame Retardants

6.1.6. Endocrine Disrupting chemicals

6.1.7. Gasoline Additives

6.1.8. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

6.1.9. Artificial Food Sweeteners

6.1.10. Food Colourants or Dyes

6.1.11. Ultraviolet Sunscreening Agents or UV Blockers/Filters

6.1.12. Musks and Fragrances

6.2. Linking EOCs in Drinking Water to Human health Risks: A Critique and Look Ahead

- (1)

- A dire lack of quantitative evidence based on case-control epidemiological or toxicological studies establishing the link between the detection of EOCs in DWS, and even other environmental matrices to specific adverse human health outcomes.

- (2)

- Human dose-response models for EOCs that account for multiple exposure sources and routes, fate and behaviour in the human body, receptors, and toxicity mechanisms are still lacking. Moreover, the fate and behaviour of EOCs in human bodies is relatively under-studied [1].

- (3)

- Rather, human exposure and health risks are simply based on inferential evidence, where detection in drinking water or other media relevant to human exposure is interpreted to constitute a significant human health hazard.

- (1)

- Research on EOCs and their health risks continues to be dominated by environmental scientists, with limited expertise in conducting case-control epidemiological studies to link EOCs in environmental matrices, including drinking water, to adverse human health outcomes.

- (2)

- Medical researchers including human epidemiologists and toxicologists with expertise in conducting case-control epidemiological studies predominantly focus on human morbidity and mortality associated with pathogens, while paying limited attention to contaminants including emerging ones. In addition, medical researchers tend to focus on clinical settings, and rarely track the epidemiological origins of diseases in the environment outside clinical settings.

- (3)

- Research entailing the use of humans as experimental objects also suffers from serious ethical and safety approval issues [284]. Such stringent conditions may constrain the acquisition of direct evidence on the human health risks of EOCs.

7. Future Directions and Conclusions

7.1. Future Directions and Perspectives

- (1) Mass loads of EOCs from delivered into drinking water systems from various sources

- (2) Removal of EOCs in low-cost drinking water treatment systems

- (3) Human exposure and intake of EOCs via drinking water

- (4) Human health risks of EOCs in drinking water systems

- (5) Comparative human health risks of legacy and emerging organic contaminants

7.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- A diverse range of EOCs belonging to the following classes was detected: pharmaceuticals, personal care products, solvents, plasticizers, endocrine disrupting compounds, gasoline additives, food colourants, artificial sweeteners, and musks and fragrances have been detected in drinking water systems.

- (2)

- The anthropogenic sources of EOCs detected in DWS including wastewater systems and industrial emissions were summarized, but data on mass loading from the various sources are currently unavailable

- (3)

- The behaviour and fate of EOCs in drinking water systems including removal processes in conventional and advanced drinking water systems were discussed. Limited data exist on the capacity of low-cost point-of-use drinking water treatment systems to remove EOCs, yet such methods are commonly used in LICs where human exposure and health risks could be high.

- (4)

- Human exposure to EOCs in drinking water systems may occur predominantly via ingestion of contaminated drinking water, and possibly via cooked foods, possibly dermal contact, and inhalation (e.g, during bathing). However, limited evidence exists on the relative contribution of the various human intake routes and intake rates.

- (5)

- The high-risk environments such as informal settlements (squatter camps, refugee camps slums) in LICs, and risk factors and behaviours predisposing humans to EOC exposure are discussed.

- (6)

- Existing data on the human health risks of the various EOCs are presented and critiqued. Overall, although EOCs pose potential human health risks, the evidence base remains weak, with the bulk of it being inferential data. This requires further research to produce quantitative epidemiological evidence directly relating the occurrence of EOCs in drinking water systems to specific adverse human health outcomes is still scarce.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwenzi, W., Emerging contaminants: A handful of conceptual and organizing frameworks, in Emerging Contaminants in the Terrestrial-Aquatic-Atmosphere Continuum:. 2022, Elsevier. p. 3-15.

- Sharma, B.M., et al., Health and ecological risk assessment of emerging contaminants (pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and artificial sweeteners) in surface and groundwater (drinking water) in the Ganges River Basin, India. 2019. 646: p. 1459-1467. [CrossRef]

- Houtman, C.J.J.J.o.I.E.S., Emerging contaminants in surface waters and their relevance for the production of drinking water in Europe. 2010. 7(4): p. 271-295.

- Gwenzi, W. and N.J.S.o.t.T.E. Chaukura, Organic contaminants in African aquatic systems: current knowledge, health risks, and future research directions. 2018. 619: p. 1493-1514.

- Ouda, M., et al., Emerging contaminants in the water bodies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): A critical review. 2021. 754: p. 142177. [CrossRef]

- Selwe, K.P., et al., Emerging contaminant exposure to aquatic systems in the Southern African Development Community. 2022. 41(2): p. 382-395. [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y., D.J.A. Barceló, and b. chemistry, Emerging contaminants in biota. 2012, Springer. p. 2525-2526. [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W., et al., Sources, behaviour, and environmental and human health risks of high-technology rare earth elements as emerging contaminants. 2018. 636: p. 299-313. [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M., et al., Emerging contaminants in waste waters: sources and occurrence. 2008: p. 1-35.

- Tran, N.H., M. Reinhard, and K.Y.-H.J.W.r. Gin, Occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants in municipal wastewater treatment plants from different geographical regions-a review. 2018. 133: p. 182-207. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R., et al., Emerging contaminants in the environment: Risk-based analysis for better management. 2016. 154: p. 350-357. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M., et al., Review of risk from potential emerging contaminants in UK groundwater. 2012. 416: p. 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Jardim, W.F., et al., An integrated approach to evaluate emerging contaminants in drinking water. 2012. 84: p. 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Schriks, M., et al., Toxicological relevance of emerging contaminants for drinking water quality. 2010. 44(2): p. 461-476. [CrossRef]

- Webb, S., et al., Indirect human exposure to pharmaceuticals via drinking water. Toxicol Lett, 2003. 142(3): p. 157-67. [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S.J. and M.J.W.r. Chaithanya Sudha, Treatment technologies for emerging organic contaminants removal from wastewater. 2018: p. 91-115.

- Wee, S.Y., et al., Tap water contamination: Multiclass endocrine disrupting compounds in different housing types in an urban settlement. 2021. 264: p. 128488. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., et al., Neonicotinoid insecticides in the drinking water system–Fate, transportation, and their contributions to the overall dietary risks. 2020. 258: p. 113722.

- Luoma, S.N.J.T.p.o.e.n.r., Silver nanotechnologies and the environment. 2008. 15: p. 12-13.

- Shi, J., et al., Groundwater antibiotics and microplastics in a drinking-water source area, northern China: Occurrence, spatial distribution, risk assessment, and correlation. 2022. 210: p. 112855. [CrossRef]

- He, P., et al., Pharmaceuticals in drinking water sources and tap water in a city in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River: occurrence, spatiotemporal distribution, and risk assessment. 2022. 29(2): p. 2365-2374. [CrossRef]

- Offiong, N.-A.O., E.J. Inam, and J.B.J.C.A. Edet, Preliminary review of sources, fate, analytical challenges and regulatory status of emerging organic contaminants in aquatic environments in selected African countries. 2019. 2: p. 573-585. [CrossRef]

- Hellar-Kihampa, H.J.A.J.o.E.S. and Technology, Another decade of water quality assessment studies in Tanzania: status, challenges and future prospects. 2017. 11(7): p. 349-360.

- Sorensen, J., et al., Emerging contaminants in urban groundwater sources in Africa. 2015. 72: p. 51-63.

- Hirsch, P., et al., National interests and transboundary water governance in the Mekong. 2006: Australian Mekong Resource Centre, in collaboration with Danish ….

- Gwenzi, W., et al., Occurrence, human health risks, and removal of pharmaceuticals in aqueous systems: Current knowledge and future perspectives. 2021: p. 63-101.

- Gwenzi, W.J.S.o.t.T.E., Leaving no stone unturned in light of the COVID-19 faecal-oral hypothesis? A water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) perspective targeting low-income countries. 2021. 753: p. 141751.

- Khan, H.K., et al., Occurrence, source apportionment and potential risks of selected PPCPs in groundwater used as a source of drinking water from key urban-rural settings of Pakistan. 2022. 807: p. 151010. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., et al., Occurrence and fate of psychiatric pharmaceuticals in the urban water system of Shanghai, China. 2015. 138: p. 486-493. [CrossRef]

- Machado, K.C., et al., A preliminary nationwide survey of the presence of emerging contaminants in drinking and source waters in Brazil. 2016. 572: p. 138-146. [CrossRef]

- Giebułtowicz, J., G.J.E. Nałęcz-Jawecki, and E. Safety, Occurrence of antidepressant residues in the sewage-impacted Vistula and Utrata rivers and in tap water in Warsaw (Poland). 2014. 104: p. 103-109.

- Liu, J., et al., Formation of perfluorocarboxylic acids from photodegradation of tetrahydroperfluorocarboxylic acids in water. 2019. 655: p. 598-606. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, F.A.M., et al., Public awareness level and occurrence of pharmaceutical residues in drinking water with potential health risk: A study from Kajang (Malaysia). 2019. 185: p. 109681. [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.Y., et al., Occurrence of multiclass endocrine disrupting compounds in a drinking water supply system and associated risks. 2020. 10(1): p. 17755. [CrossRef]

- Kondor, A.C., et al., Occurrence and health risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in riverbank filtrated drinking water. 2021. 41: p. 102039. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.V., et al., Occurrence and risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in water supply systems in Brazil. 2020. 746: p. 141011. [CrossRef]

- Kozisek, F., et al., Survey of human pharmaceuticals in drinking water in the Czech Republic. 2013. 11(1): p. 84-97. [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal-Ciro, C., et al., Monitoring pharmaceuticals and personal care products in reservoir water used for drinking water supply. 2017. 24: p. 7335-7347. [CrossRef]

- Jux, U., et al., Detection of pharmaceutical contaminations of river, pond, and tap water from Cologne (Germany) and surroundings. 2002. 205(5): p. 393-398. [CrossRef]

- Ślósarczyk, K., et al., Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the water environment of Poland: A review. 2021. 13(16): p. 2283.

- Oluwalana, A.E., et al., The screening of emerging micropollutants in wastewater in Sol Plaatje Municipality, Northern Cape, South Africa. 2022. 314: p. 120275. [CrossRef]

- Moodley, B., G. Birungi, and P. Ndungu, Detection and quantification of emerging organic pollutants in the Umgeni and Msunduzi Rivers. 2016.

- Tahrani, L., et al., Occurrence of antibiotics in pharmaceutical industrial wastewater, wastewater treatment plant and sea waters in Tunisia. 2016. 14(2): p. 208-213. [CrossRef]

- Chaib, O., et al., Occurrence and Seasonal Variation of Antibiotics in Fez-Morocco Surface Water. American Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2019. 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Ebele, A.J., et al., Occurrence, seasonal variation and human exposure to pharmaceuticals and personal care products in surface water, groundwater and drinking water in Lagos State, Nigeria. 2020. 6: p. 124-132. [CrossRef]

- Osunmakinde, C.S., et al., Verification and validation of analytical methods for testing the levels of PPHCPs (pharmaceutical & personal health care products) in treated drinking water and sewage: report to the Water Research Commission. 2013: Water Research Commission Pretoria.

- Mhuka, V., S. Dube, and M.M.J.E.C. Nindi, Occurrence of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) in wastewater and receiving waters in South Africa using LC-Orbitrap™ MS. 2020. 6: p. 250-258. [CrossRef]

- Farounbi, A.I., N.P.J.E.S. Ngqwala, and P. Research, Occurrence of selected endocrine disrupting compounds in the eastern cape province of South Africa. 2020. 27(14): p. 17268-17279. [CrossRef]

- Agunbiade, F.O., B.J.E.m. Moodley, and assessment, Pharmaceuticals as emerging organic contaminants in Umgeni River water system, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. 2014. 186: p. 7273-7291. [CrossRef]

- Amdany, R., L. Chimuka, and E.J.W.S. Cukrowska, Determination of naproxen, ibuprofen and triclosan in wastewater using the polar organic chemical integrative sampler (POCIS): A laboratory calibration and field application. 2014. 40(3): p. 407-414. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., L. Gautam, and S.W.J.C. Hall, The detection of drugs of abuse and pharmaceuticals in drinking water using solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. 2019. 223: p. 438-447. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., Suspect screening to support source identification and risk assessment of organic micropollutants in the aquatic environment of a Sub-Saharan African urban center. 2022. 220: p. 118706. [CrossRef]

- Twinomucunguzi, F.R., et al., Emerging organic contaminants in shallow groundwater underlying two contrasting peri-urban areas in Uganda. 2021. 193: p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- K'oreje, K., et al., Occurrence patterns of pharmaceutical residues in wastewater, surface water and groundwater of Nairobi and Kisumu city, Kenya. 2016. 149: p. 238-244. [CrossRef]

- Rutanhira, C., Occurrence of organic compounds in water and sediments in Sebakwe river. 2019.

- Caldas, S.S., et al., Occurrence of pesticides and PPCPs in surface and drinking water in southern Brazil: Data on 4-year monitoring. 2019. 30: p. 71-80. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S., V. Homem, and L.J.J.o.C.A. Santos, Simultaneous determination of synthetic musks and UV-filters in water matrices by dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction followed by gas chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry. 2019. 1590: p. 47-57. [CrossRef]

- Wombacher, W.D. and K.C.J.J.o.E.E. Hornbuckle, Synthetic musk fragrances in a conventional drinking water treatment plant with lime softening. 2009. 135(11): p. 1192-1198.

- Relić, D., et al., Occurrence of synthetic musk compounds in surface, underground, waste and processed water samples in Belgrade, Serbia. 2017. 76: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., et al., Graphene-derivatized silica composite as solid-phase extraction sorbent combined with GC–MS/MS for the determination of polycyclic musks in aqueous samples. 2018. 23(2): p. 318. [CrossRef]

- Arruda, V., M. Simões, and I.B.J.W. Gomes, Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Water Systems and Their Impact on Microbial Communities. 2022. 14(5): p. 692. [CrossRef]

- Bester, K.J.A.o.E.C. and Toxicology, Fate of triclosan and triclosan-methyl in sewage treatmentplants and surface waters. 2005. 49: p. 9-17.

- Bruchet, A., et al., Analysis of drugs and personal care products in French source and drinking waters: the analytical challenge and examples of application. 2005. 52(8): p. 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cruz, M.S., et al., Analysis of UV filters in tap water and other clean waters in Spain. 2012. 402: p. 2325-2333. [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A., et al., Urban groundwater contamination by residues of UV filters. J Hazard Mater, 2014. 271: p. 141-9. [CrossRef]

- Rodil, R., et al., Emerging pollutants in sewage, surface and drinking water in Galicia (NW Spain). 2012. 86(10): p. 1040-1049.

- Da Silva, C.P., et al., The occurrence of UV filters in natural and drinking water in São Paulo State (Brazil). 2015. 22: p. 19706-19715. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.u., et al., Heavy Metals, Pesticide, Plasticizers Contamination and Risk Analysis of Drinking Water Quality in the Newly Developed Housing Societies of Gujranwala, Pakistan. 2022. 14(22): p. 3787. [CrossRef]

- Penalver, A., et al., Determination of phthalate esters in water samples by solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography with mass spectrometric detection. 2000. 872(1-2): p. 191-201. [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Beltrán, D., et al., Determination of phthalates in bottled water by automated on-line solid phase extraction coupled to liquid chromatography with UV detection. 2017. 168: p. 291-297.

- Zaater, M.F., Y.R. Tahboub, and A.N.J.J.o.c.s. Al Sayyed, Determination of phthalates in Jordanian bottled water using GC–MS and HPLC–UV: environmental study. 2014. 52(5): p. 447-452.

- Alshehri, M.M., et al., Determination of phthalates in bottled waters using solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. 2022. 304: p. 135214. [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, J. and N.J.A.C.A. Vasudevan, Detection of phthalate esters in PET bottled drinks and lake water using esterase/PANI/CNT/CuNP based electrochemical biosensor. 2020. 1135: p. 175-186.

- Kumar, A., et al., Bisphenol A in canned soft drinks, plastic-bottled water, and household water tank from Punjab, India. 2023. 9: p. 100205. [CrossRef]

- Struzina, L., et al., Occurrence of legacy and replacement plasticizers, bisphenols, and flame retardants in potable water in Montreal and South Africa. 2022. 840: p. 156581. [CrossRef]

- Kandie, F.J., et al., Occurrence and risk assessment of organic micropollutants in freshwater systems within the Lake Victoria South Basin, Kenya. 2020. 714: p. 136748. [CrossRef]

- Wanda, E.M., et al., Occurrence of emerging micropollutants in water systems in Gauteng, Mpumalanga, and North West Provinces, South Africa. 2017. 14(1): p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, P., et al., Incomplete degradation of linear alkylbenzene sulfonate surfactants in Brazilian surface waters and pursuit of their polar metabolites in drinking waters. 2002. 284(1-3): p. 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, P., et al., Occurrence and fate of linear and branched alkylbenzenesulfonates and their metabolites in surface waters in the Philippines. 2001. 269(1-3): p. 75-85. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, V., et al., Determination of non-ionic and anionic surfactants in environmental water matrices. 2011. 84(3): p. 859-866.

- Zhang, Q., et al., Organophosphate flame retardants in Hangzhou tap water system: Occurrence, distribution, and exposure risk assessment. 2022. 849: p. 157644. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., et al., Occurrence and exposure assessment of organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) through the consumption of drinking water in Korea. 2016. 103: p. 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Occurrence of organophosphate flame retardants in drinking water from China. 2014. 54: p. 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Cristale, J., et al., Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry comprehensive analysis of organophosphorus, brominated flame retardants, by-products and formulation intermediates in water. 2012. 1241: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Olukunle, O., et al., Determination of brominated flame retardants in Jukskei River catchment area in Gauteng, South Africa. 2012. 65(4): p. 743-749. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U., et al., First insight into the levels and distribution of flame retardants in potable water in Pakistan: an underestimated problem with an associated health risk diagnosis. 2016. 565: p. 346-359. [CrossRef]

- Onyekwere, O., et al., Occurrence and risk assessment of phenolic endocrine disrupting chemicals in shallow groundwater resource from selected Nigerian rural settlements. 2019. 30(2): p. 101-107. [CrossRef]

- Inam, E.J., et al., Ecological risks of phenolic endocrine disrupting compounds in an urban tropical river. 2019. 26: p. 21589-21597. [CrossRef]

- Chafi, S., A. Azzouz, and E.J.C. Ballesteros, Occurrence and distribution of endocrine disrupting chemicals and pharmaceuticals in the river Bouregreg (Rabat, Morocco). 2022. 287: p. 132202. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., A.A.J.A.S.C. Keller, and Engineering, Magnetic nanoparticle adsorbents for emerging organic contaminants. 2013. 1(7): p. 731-736. [CrossRef]

- Van Zijl, M.C., et al., Estrogenic activity, chemical levels and health risk assessment of municipal distribution point water from Pretoria and Cape Town, South Africa. 2017. 186: p. 305-313. [CrossRef]

- Aneck-Hahn, N.H., et al., Estrogenic activity, selected plasticizers and potential health risks associated with bottled water in South Africa. 2018. 16(2): p. 253-262. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Tapia, I., et al., Occurrence of emerging organic contaminants and endocrine disruptors in different water compartments in Mexico–A review. 2022: p. 136285. [CrossRef]

- Touraud, E., et al., Drug residues and endocrine disruptors in drinking water: risk for humans? Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2011. 214(6): p. 437-41.

- Gao, J., et al., Occurrence and distribution of organochlorine pesticides–lindane, p, p′-DDT, and heptachlor epoxide–in surface water of China. 2008. 34(8): p. 1097-1103.

- Jones, K.C. and P.J.E.p. De Voogt, Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): state of the science. 1999. 100(1-3): p. 209-221. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers-Gray, T.P., et al., Long-term temporal changes in the estrogenic composition of treated sewage effluent and its biological effects on fish. 2000. 34(8): p. 1521-1528. [CrossRef]

- Kuch, H.M., K.J.E.s. Ballschmiter, and technology, Determination of endocrine-disrupting phenolic compounds and estrogens in surface and drinking water by HRGC−(NCI)− MS in the picogram per liter range. 2001. 35(15): p. 3201-3206. [CrossRef]

- Teta, C., et al., Occurrence of oestrogenic pollutants and widespread feminisation of male tilapia in peri-urban dams in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. 2018. 43(1): p. 17-26.

- Msigala, S.C., et al., Pollution by endocrine disrupting estrogens in aquatic ecosystems in Morogoro urban and peri-urban areas in Tanzania. 2017. 11(2): p. 122-131.

- Sörengård, M., et al., Long-distance transport of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in a Swedish drinking water aquifer. 2022. 311: p. 119981. [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, C.S. and B.A.J.J.o.C.A. Logue, Ultratrace analysis of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in drinking water using ice concentration linked with extractive stirrer and high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. 2021. 1659: p. 462493.

- Appleman, T.D., et al., Treatment of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances in US full-scale water treatment systems. 2014. 51: p. 246-255. [CrossRef]

- Post, G.B., et al., Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds in raw water from New Jersey public drinking water systems. 2013. 47(23): p. 13266-13275.

- Batayi, B., et al., Poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in sediment samples from Roodeplaat and Hartbeespoort Dams, South Africa. 2020. 6: p. 367-375. [CrossRef]

- Dalahmeh, S., et al., Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water, soil and plants in wetlands and agricultural areas in Kampala, Uganda. 2018. 631: p. 660-667.

- Ahrens, L., et al., Poly-and perfluoroalkylated substances (PFASs) in water, sediment and fish muscle tissue from Lake Tana, Ethiopia and implications for human exposure. 2016. 165: p. 352-357.

- Essumang, D.K., et al., Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in the Pra and Kakum River basins and associated tap water in Ghana. 2017. 579: p. 729-735. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.E. and M. Tiemann, MTBE in gasoline: clean air and drinking water issues. 2006.

- van Wezel, A., et al., Odour and flavour thresholds of gasoline additives (MTBE, ETBE and TAME) and their occurrence in Dutch drinking water collection areas. 2009. 76(5): p. 672-676.

- Mawhinney, D.B., et al., Artificial sweetener sucralose in US drinking water systems. 2011. 45(20): p. 8716-8722. [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, M., et al., Analysis and occurrence of seven artificial sweeteners in German waste water and surface water and in soil aquifer treatment (SAT). 2009. 394: p. 1585-1594. [CrossRef]

- Buerge, I.J., et al., Ubiquitous occurrence of the artificial sweetener acesulfame in the aquatic environment: an ideal chemical marker of domestic wastewater in groundwater. 2009. 43(12): p. 4381-4385.

- Scheurer, M., et al., Performance of conventional multi-barrier drinking water treatment plants for the removal of four artificial sweeteners. 2010. 44(12): p. 3573-3584. [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.T., et al., Artificial sweeteners—a recently recognized class of emerging environmental contaminants: a review. 2012. 403(9): p. 2503-2518. [CrossRef]

- Van Stempvoort, D.R., et al., Artificial sweeteners as potential tracers in groundwater in urban environments. Journal of Hydrology, 2011. 401(1): p. 126-133. [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk-Wlizło, A., K. Mitrowska, and T. Błądek, Quantification of twenty pharmacologically active dyes in water samples using UPLC-MS/MS. Heliyon, 2022. 8(4): p. e09331. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, P.A., et al., Assessment of water contamination caused by a mutagenic textile effluent/dyehouse effluent bearing disperse dyes. J Hazard Mater, 2010. 174(1-3): p. 694-9.

- Lei, M., et al., Overview of emerging contaminants and associated human health effects. 2015. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.Q., et al., Environmental impact of the presence, distribution, and use of artificial sweeteners as emerging sources of pollution. 2021. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Praveena, S.M., et al., Non-nutritive artificial sweeteners as an emerging contaminant in environment: A global review and risks perspectives. 2019. 170: p. 699-707. [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk-Wlizło, A. and K. Mitrowska, Occurrence and ecotoxicological risk assessment of pharmacologically active dyes in the environmental water of Poland. Chemosphere, 2023. 313: p. 137432. [CrossRef]

- Stackelberg, P.E., et al., Persistence of pharmaceutical compounds and other organic wastewater contaminants in a conventional drinking-water-treatment plant. 2004. 329(1-3): p. 99-113.

- Bond, T., et al., Occurrence and control of nitrogenous disinfection by-products in drinking water–a review. 2011. 45(15): p. 4341-4354. [CrossRef]

- Bond, T., M.R. Templeton, and N.J.J.o.h.m. Graham, Precursors of nitrogenous disinfection by-products in drinking water––a critical review and analysis. 2012. 235: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Chaukura, N., et al., Contemporary issues on the occurrence and removal of disinfection byproducts in drinking water-a review. 2020. 8(2): p. 103659.

- Yang, X., et al., Identification of key precursors contributing to the formation of CX3R-type disinfection by-products along the typical full-scale drinking water treatment processes. 2023. 128: p. 81-92. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., et al., Prevalence, production, and ecotoxicity of chlorination-derived metformin byproducts in Chinese urban water systems. 2022. 816: p. 151665. [CrossRef]

- Trček, B., et al., The fate of benzotriazole pollutants in an urban oxic intergranular aquifer. 2018. 131: p. 264-273.

- Gowd, S.S., M.R. Reddy, and P.J.J.o.h.m. Govil, Assessment of heavy metal contamination in soils at Jajmau (Kanpur) and Unnao industrial areas of the Ganga Plain, Uttar Pradesh, India. 2010. 174(1-3): p. 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Simazaki, D., et al., Occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals at drinking water purification plants in Japan and implications for human health. 2015. 76: p. 187-200. [CrossRef]

- Sorlini, S., et al., Technologies for the control of emerging contaminants in drinking water treatment plants. 2019. 18(10).

- Valbonesi, P., et al., Contaminants of emerging concern in drinking water: Quality assessment by combining chemical and biological analysis. 2021. 758: p. 143624. [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M., S. Gonzalez, and D.J.T.T.i.A.C. Barceló, Analysis and removal of emerging contaminants in wastewater and drinking water. 2003. 22(10): p. 685-696.

- Ternes, T.A., et al., Removal of pharmaceuticals during drinking water treatment. 2002. 36(17): p. 3855-3863.

- Sillanpää, M., et al., Removal of natural organic matter in drinking water treatment by coagulation: A comprehensive review. 2018. 190: p. 54-71.

- Finkbeiner, P., et al., Understanding the potential for selective natural organic matter removal by ion exchange. 2018. 146: p. 256-263. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., et al., Removal of intermediate aromatic halogenated DBPs by activated carbon adsorption: a new approach to controlling halogenated DBPs in chlorinated drinking water. 2017. 51(6): p. 3435-3444. [CrossRef]

- McCleaf, P., et al., Removal efficiency of multiple poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in drinking water using granular activated carbon (GAC) and anion exchange (AE) column tests. 2017. 120: p. 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M., et al., Legacy and emerging perfluoroalkyl substances are important drinking water contaminants in the Cape Fear River Watershed of North Carolina. 2016. 3(12): p. 415-419. [CrossRef]

- Khatibikamal, V., et al., Optimized poly (amidoamine) coated magnetic nanoparticles as adsorbent for the removal of nonylphenol from water. 2019. 145: p. 508-516. [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C., et al., Occurrence and fate of emerging pollutants in water environment and options for their removal. 2021. 13(2): p. 181. [CrossRef]

- Maier, R.M. and T.J. Gentry, Microorganisms and organic pollutants, in Environmental microbiology. 2015, Elsevier. p. 377-413.

- Caracciolo, A.B., et al., Degradation of a fluoroquinolone antibiotic in an urbanized stretch of the River Tiber. 2018. 136: p. 43-48.

- Wu, D., et al., The occurrence and risks of selected emerging pollutants in drinking water source areas in Henan, China. 2019. 16(21): p. 4109. [CrossRef]

- Schlüter-Vorberg, L., et al., Toxification by transformation in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: the antiviral drug acyclovir. 2015. 2(12): p. 342-346.

- Wang, S. and J. Wang, Degradation of emerging contaminants by acclimated activated sludge. Environ Technol, 2018. 39(15): p. 1985-1993. [CrossRef]

- Gabarrón, S., et al., Evaluation of emerging contaminants in a drinking water treatment plant using electrodialysis reversal technology. 2016. 309: p. 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., et al., Endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) and pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in the aquatic environment: implications for the drinking water industry and global environmental health. 2009. 7(2): p. 224-243. [CrossRef]

- Clara, M., et al., Removal of selected pharmaceuticals, fragrances and endocrine disrupting compounds in a membrane bioreactor and conventional wastewater treatment plants. 2005. 39(19): p. 4797-4807. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.D., Disinfection by-products: formation and occurrence in drinking water. 2011.

- Sorlini, S., et al., CONTROL MEASURES FOR Cyanobacteria AND Cyanotoxins IN DRINKING WATER. 2018. 17(10). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Occurrences and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in drinking water and water/sewage treatment plants: A review. 2017. 596: p. 303-320. [CrossRef]

- Program, N.T., Haloacetic Acids Found as Water Disinfection Byproducts (Selected), in 15th Report on Carcinogens [Internet]. 2021, National Toxicology Program.

- Petrovic, M., et al., Occurrence and removal of estrogenic short-chain ethoxy nonylphenolic compounds and their halogenated derivatives during drinking water production. 2003. 37(19): p. 4442-4448. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Sand and sand-GAC filtration technologies in removing PPCPs: A review. 2022: p. 157680.

- Xu, L., Drinking water biofiltration: Removal of antibiotics and behaviour of antibiotic resistance genes. 2020, UCL (University College London).

- Zearley, T.L., R.S.J.E.s. Summers, and technology, Removal of trace organic micropollutants by drinking water biological filters. 2012. 46(17): p. 9412-9419. [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.Y. and A.Z.J.N.C.W. Aris, Occurrence and public-perceived risk of endocrine disrupting compounds in drinking water. 2019. 2(1): p. 4. [CrossRef]

- Bayabil, H., F. Teshome, and Y.J.E.S. Li, Emerging Contaminants in Soil and Water. Front. 2022. 10: p. 1-8.

- Schaider, L.A., et al., Pharmaceuticals, perfluorosurfactants, and other organic wastewater compounds in public drinking water wells in a shallow sand and gravel aquifer. 2014. 468: p. 384-393. [CrossRef]

- Law, I.B., et al., Validation of the Goreangab reclamation plant in Windhoek, Namibia against the 2008 Australian guidelines for water recycling. 2015. 5(1): p. 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Tortajada, C. and P.J.N. van Rensburg, Drink more recycled wastewater. 2020. 577(7788): p. 26-28.

- Muñiz-Bustamante, L., N. Caballero-Casero, and S.J.E.i. Rubio, Drugs of abuse in tap water from eight European countries: Determination by use of supramolecular solvents and tentative evaluation of risks to human health. 2022. 164: p. 107281. [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O., et al., Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PPCPs) and pesticides in African water systems: A need for timely intervention. Heliyon, 2022. 8(3): p. e09143. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, D.J., et al., Human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in the European Vecht River. 2022. 18(6): p. 1639-1654. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S., F. Bano, and A. Malik, Pharmaceuticals and personal care product (PPCP) contamination—a global discharge inventory, in Pharmaceuticals and personal care products: waste management and treatment technology. 2019, Elsevier. p. 1-26.

- Paulsen, L., The health risks of chemicals in personal care products and their fate in the environment. 2015.

- Covaci, A., et al., Human exposure and health risks to emerging organic contaminants. 2012: p. 243-305.

- Becker, J.A. and A.I. Stefanakis, Pharmaceuticals and personal care products as emerging water contaminants, in Pharmaceutical Sciences: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice. 2017, IGI Global. p. 1457-1475.

- Mokra, K.J.I.J.o.M.S., Endocrine disruptor potential of short-and long-chain perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)—A synthesis of current knowledge with proposal of molecular mechanism. 2021. 22(4): p. 2148.

- Kumawat, M., et al., Occurrence and seasonal disparity of emerging endocrine disrupting chemicals in a drinking water supply system and associated health risk. 2022. 12(1): p. 9252. [CrossRef]

- Gonsioroski, A., V.E. Mourikes, and J.A.J.I.j.o.m.s. Flaws, Endocrine disruptors in water and their effects on the reproductive system. 2020. 21(6): p. 1929.

- Slama, R., S.J.E.i.o.r.h. Cordier, and fertility, Environmental contaminants and impacts on healthy and successful pregnancies. 2010.

- Fromme, H., et al., Perfluorinated compounds–exposure assessment for the general population in Western countries. 2009. 212(3): p. 239-270. [CrossRef]

- Herrick, R.L., et al., Polyfluoroalkyl substance exposure in the Mid-Ohio River Valley, 1991-2012. Environ Pollut, 2017. 228: p. 50-60. [CrossRef]

- Kibuye, F.A., et al., Influence of hydrologic and anthropogenic drivers on emerging organic contaminants in drinking water sources in the Susquehanna River Basin. 2020. 245: p. 125583. [CrossRef]