1. Introduction

The pioneering effort of Wichterle and Lim was first reported on cross-linked HEMA polymeric hydrogels in 1960 [

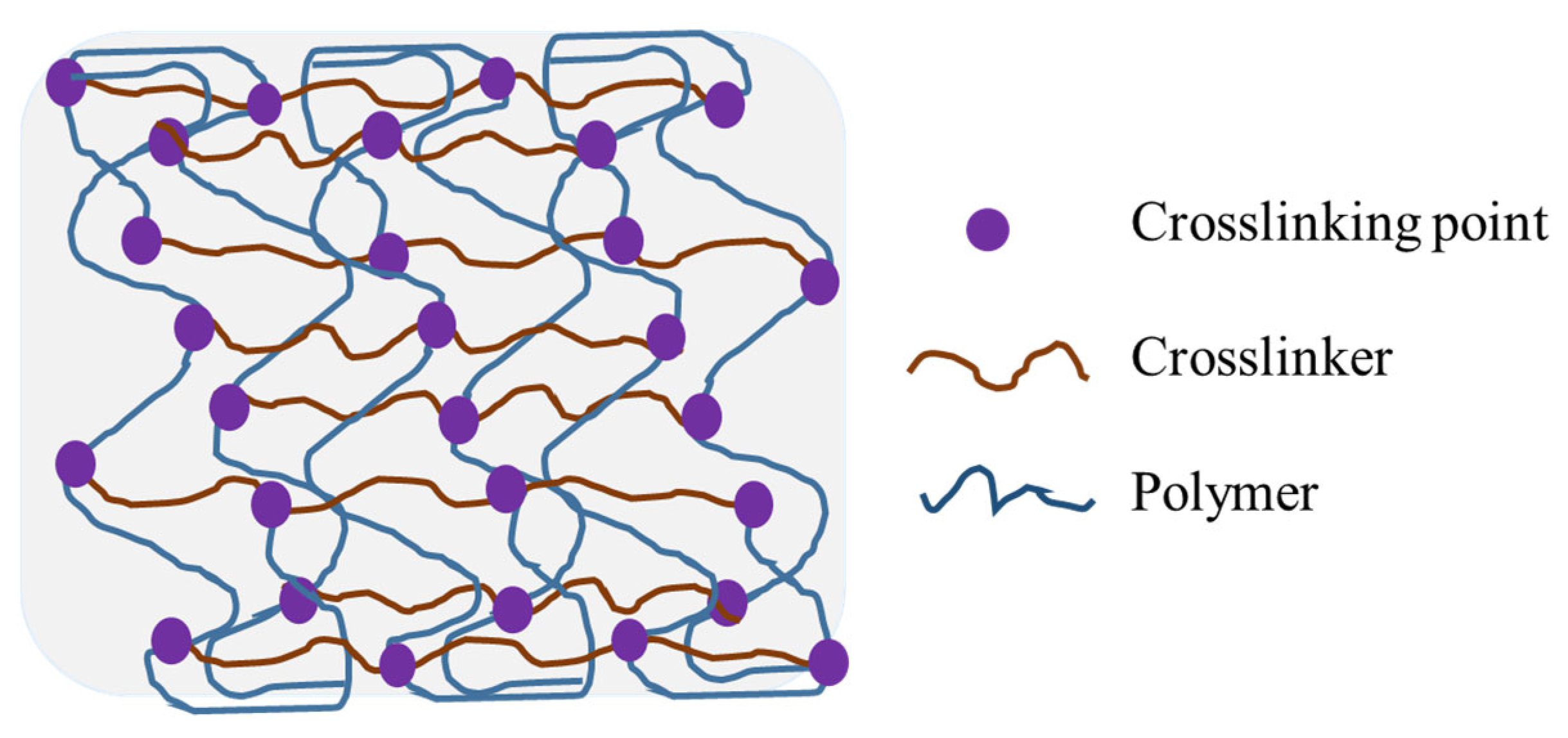

1]. It has been one of the greatest interests to biomaterial scientists which has led to the development of a new class of functional polymeric material having a three-dimensional network structure constructed by physical, chemical, or both physical and chemical cross-linking of hydrophilic macromolecules (

Figure 1.) [

2]. Polymeric hydrogels absorb large volumes of water, swell, and maintain their original structures without being dissolved; the surfaces of the polymeric hydrogels become wet and malleable [3-6]. Polymeric hydrogels reduce irritation to the surrounding tissues and improve biocompatibility by combining with the stable organization of the material significantly [

7,

8]. Polymeric hydrogels possess a dynamic balance with biological fluids or water. The absorption of biological fluid in the polymeric hydrogel matrix leads to swelling that creates a loose network that releases drugs from the polymeric hydrogel matrix [

9]. Polymeric hydrogels can be injectable, [

10] which represents an appreciable advantage over conventional surgical procedures.

Polymeric hydrogels are delicate to little change in external stimuli [

11] such as physical stimuli (temperature, magnetic field electric fields, etc.) and chemical stimuli (pH, ionic strength), and in response to that, they expand or contract their volume. In this manner, polymeric hydrogels are similar to living soft tissue, the cell lattice external film, then some other as of now well-known manufactured biomaterials, and these properties bring about decreasing grating and mechanical properties on the neighboring tissues, that together improves the material properties [12-14]. Since polymeric hydrogels produce tremendous monetary and social advantages, the exploration, the turn of events, the application, and the creation of hydrogels speak to a significant zone of the biomaterial field.

2. Properties of Polymeric Hydrogels

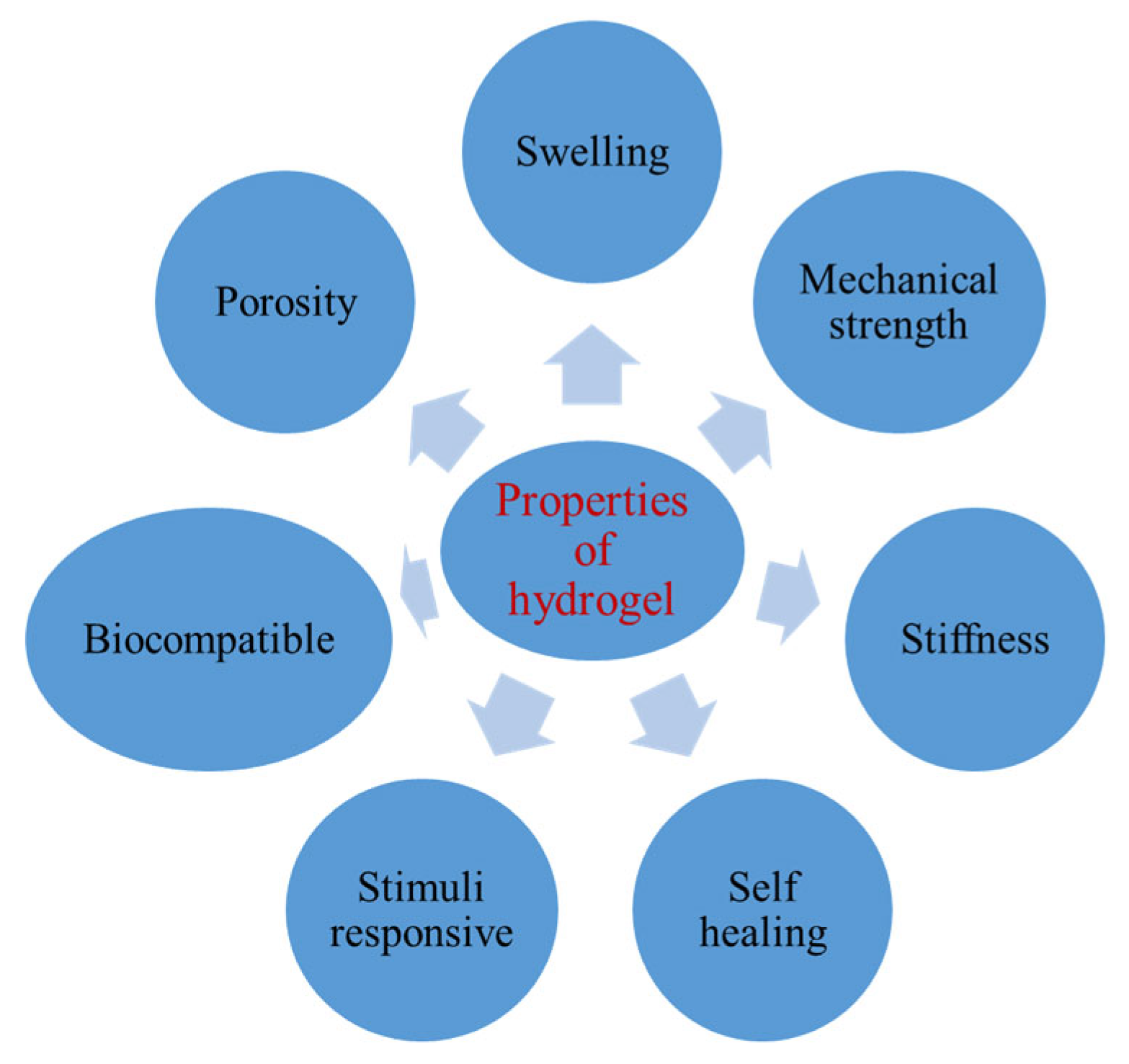

Polymeric hydrogels also called hydrophilic gels to receive significant attention for their use in the field of pharmaceutical sciences and biomedical engineering. Instead of abundant advancement, a simple understanding of polymeric hydrogel properties is not yet adequate for a truthful design of novel polymeric hydrogel systems. Properties of polymeric hydrogels can be classified into physical and chemical properties (

Figure 2.) [

15]. Polymeric hydrogels have: [

11,

16,

17]

Solid and liquid-like properties

Biocompatibility and biodegradability

Maximum absorption capacity

Desired porosity and preferred particle size

Shrink on drying

Stimuli-responsive

2.1. Swelling

The equilibrium swelling of polymeric hydrogels depends on the charge densities and crosslinking of the polymer network as well as the concentration of cross-linked polymer. One of the most important factors that affect swelling is the crosslinking ratio. Highly cross-linked polymeric hydrogels swell less compared with low cross-linked polymeric hydrogels because of their tight structure. Stimuli-sensitive polymeric hydrogels can be affected by a small change in external parameters such as pH, temperature, and enzyme that lead to a fast and reversible modification in the physical property of the polymeric hydrogel [

18].

2.2. Mechanical Strength

In a polymeric hydrogel system, mechanical strength is important to maintain its stability so it can tolerate loads and recover the failings macroscopically [

19]. The mechanical strength of the polymeric hydrogel can be achieved by changing the degree of crosslinking. As the crosslinking degree increases, the percentage elongation of the polymeric hydrogels decreases which creates a more hard and brittle structure [

19,

20]. Traditional polymeric hydrogels cannot be utilized for specific tissue engineering applications due to their hard and breakable characteristics. Two effective strategies have been developed to overcome this issue; one is the hybridization of polymeric hydrogels with other polymers and the other strategy is to prepare interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) hydrogels.

2.3. Stiffness

Stiffness is defined as the extent to which a polymeric hydrogel fights distortion in response to an applied force. Flexibility or pliability is the complementary concept of stiffness. The higher flexibility of polymeric hydrogel represents low stiffness and vice versa. Polymeric hydrogel stiffness can be altered by changing the cross-linker length, crosslinking density, and molecular weight of the precursors [

21,

22].

2.4. Stress Relaxation

In polymeric hydrogel, stress relaxation is defined as the material’s tendency to decrease its stress in response to applied strain or deflection. Stress relaxation should not be confused with creep, which is a constant state of stress with an increasing amount of strain. The study of stress relaxation is very useful to understand the change in the viscoelastic properties of the materials over a long time [

23].

2.5. Self-Healing

Self-healing is the ability of a polymeric hydrogel to sense environmental alterations and adjust to them by changing its properties and function [

24]. There are two types of self-healing mechanisms based on self-healing chemistry namely extrinsic and intrinsic.

Extrinsic self-healing does not show healing capability naturally after the damage. It occurs when some additional healing agents and a catalyst are incorporated into the matrix. Microvascular and micro capsulation is used frequently to prepare such types of materials and in both cases; an external healing agent is used self-healing process [

25].

Intrinsic self-healing shows healing capability naturally without any external healing agent or external interference. The chemistry [

26] behind intrinsic self-healing is non-covalent interaction (metal ligands interactions, hydrogen bonding, and host-guest interaction) and dynamic interaction (Diels Alder’s (DA) bond [

27], disulfide exchange, and ester exchange).

2.6. Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility of a material is defined as the ability to perform a sufficient response to the host in a particular application without producing any toxicity or immunological response [

15,

28]. It consists of two elements (

Figure 3):

- (i)

Bio functionality - the ability to perform the specific task for which it is intended.

- (ii)

Biosafety - the ability to perform adequate systemic and local (the surrounding tissue) host response without causing mutagenesis, cytotoxicity, and carcinogenesis.

The biocompatibility of injectable polymeric hydrogel is of special concern as the gel is injected in the prepolymer state. The leaching of by-products and unreacted crosslinkers reduces biocompatibility. The generation of heat during in-situ gel formation should be minimum. Leaching of degraded mass from the gel should not show any toxicity. Determination of in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of a polymeric hydrogel is important to assess its suitability in a particular application.

2.7. Porosity

Porosity is the measurement of the void spaces in a polymeric hydrogel and is defined as a fraction of the void space over the total space [

29,

30]. Porosity in polymeric hydrogels can be created by mainly two different approaches:

Tortuosity, the important aspects of a hydrogel matrix such as average pore size, distribution, and interconnections are difficult to calculate. There are three main factors, which effectively influence the pore-size distributions of hydrogel:

The concentration of crosslinkers in polymer chains

Physical entanglements concentration of the polymer chains

Polyelectrolytes net charge

3. Advantages of Polymeric Hydrogels [31,32]

High water content provides flexibility like natural tissue

Loading and release of therapeutics

Biocompatible, Biodegradable, and Injectable

Smart polymeric hydrogels are responsive to external stimuli

Easy to modify and good transport property

4. Disadvantages of Polymeric Hydrogels [31,32]

5. Classification of Polymeric Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogel products can be classified on different bases as detailed below [

33] (

Figure 4).

5.1. Based on Their Source and Synthesis

Polymeric hydrogels are mainly classified into three groups based on their source of origin and synthesis.

o Natural polymeric hydrogels

o Synthetic polymeric hydrogels

o Hybrid polymeric hydrogels

5.1.1. Natural Polymeric Hydrogels

Natural polymeric hydrogels are made up of polymers, which are obtained from natural sources and do need not to synthesize. This makes hydrogels naturally biocompatible and probably appropriate in different biomedical applications as they support many cellular functions. The structure and properties of this type of polymeric hydrogel are like the soft biological tissues. Natural hydrogels are mainly obtained from three types of materials: protein-based, polysaccharide-based, and those derived from decellularized tissue [

34,

35].

5.1.2. Synthetic Polymeric Hydrogels

Synthetic polymeric hydrogels are made up of synthetic polymers and have similar properties to that of a natural hydrogel. Compared to natural hydrogels, they are more useful because they can be tuned to a much wider variety of mechanical properties as well as chemical properties. One of the widely used materials in biomedical application is polyethene glycol (PEG) based hydrogels [

36].

5.1.3. Hybrid Polymeric Hydrogels

Hybrid polymeric hydrogels are a mixture of both natural and synthetic polymers needed to synthesize when the precursor molecule is structurally too complex or costly. Numerous natural polymers such as chitosan and dextran have been pooled with synthetic polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol and poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) to combine their beneficial properties [

37].

Figure 4.

Classification of hydrogel.

Figure 4.

Classification of hydrogel.

5.2. Based on Polymeric Composition

Polymeric hydrogels can be classified into three groups based on their polymeric compositions (

Figure 5).

o Homopolymeric hydrogels

o Co-polymeric hydrogels

o Interpenetrating polymeric network hydrogel

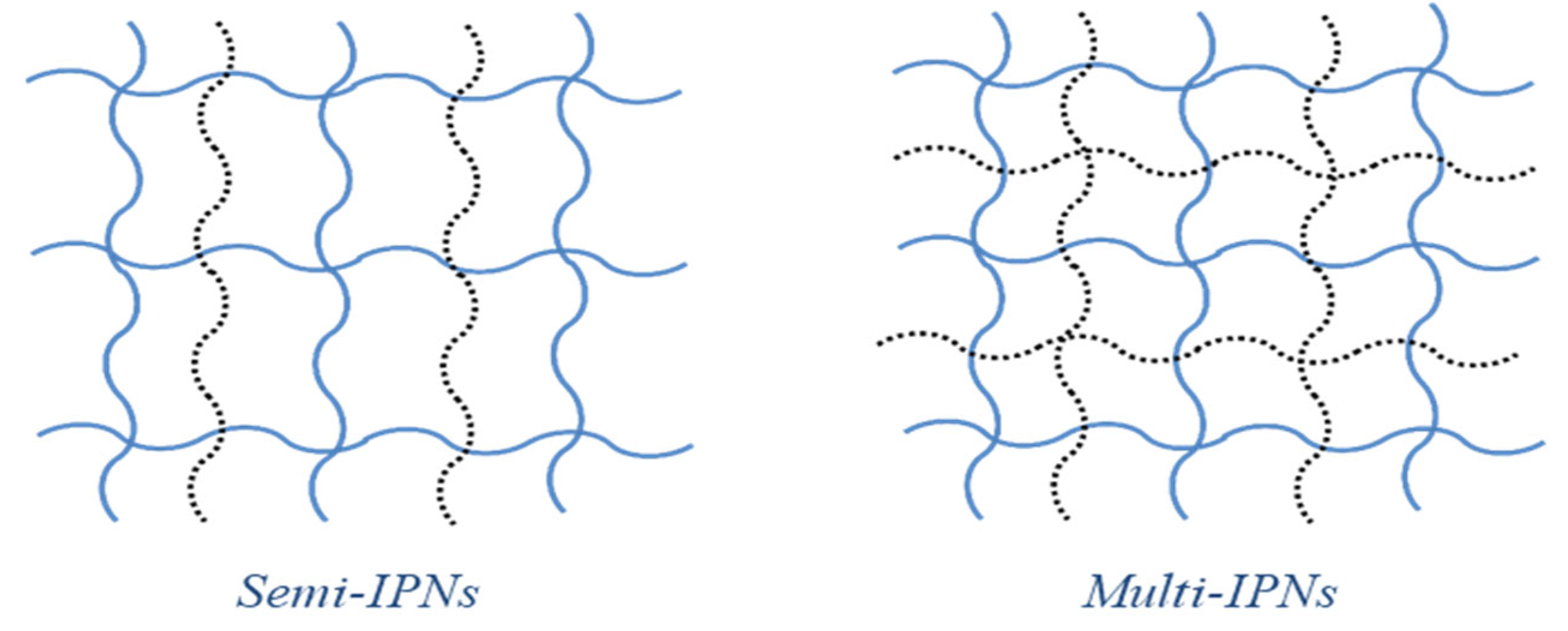

➢ Semi-interpenetrating polymer network

➢ Multi-interpenetrating polymer network

5.2.1. Homopolymeric Hydrogels

Homopolymeric hydrogels are a basic structural unit consisting of any polymeric network resulting from only one type of monomer. Homopolymers may have cross-linked structures based on nature and polymerization technique. It can be applied in contact lenses, artificial skin manufacturing, cell regeneration, burn dressings, promoting cell adhesion, bone marrow, and cartilage production [

38].

5.2.2. Co-polymeric hydrogels

Co-polymeric hydrogels are made up of two or more two dissimilar monomers in which at least one hydrophilic component should be present. These hydrogels were pH and temperature-sensitive and characterized for drug delivery application [

39].

5.2.3. Interpenetrating polymeric network (IPN)

Interpenetrating polymer network is a polymer mixture consisting of two or more polymer networks where a partial interlacing is present on a polymer scale. There is no covalent bonding therefore the polymer network cannot be separated unless chemical bonds are broken [

40]. Interpenetrating polymeric networks are of different types in which two of which are discussed below.

5.2.3.1. Semi-interpenetrating polymeric hydrogel

Semi-interpenetrating polymeric hydrogel is formed when one linear polymer penetrates another cross-linked polymer network without chemical bonding. All the types of IPN listed earlier are found in vegetable oil-based polymers. These IPNs have some advantages over polymer blends or cross-linked polymers.

5.2.3.2. Multi-Interpenetrating Polymeric Hydrogel

Multi-interpenetrating polymeric hydrogel is made of two independent cross-linked polymer components, contained in a network form. The problem of thermodynamic incompatibility can be overcome by limited phase separation and permanent interlocking of the polymer network. The interlocked polymer arrangement of the cross-linked IPN is believed to confirm bulk and surface morphological stability.

Advantages

• Compact hydrogel matrix

• Controllable physical properties

• More efficient drug loading.

5.3. Based on Degradability

5.3.1. Biodegradable Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogels that are capable of being decomposed by living organisms and thereby avoiding toxic substances are called biodegradable hydrogels. Many natural polymers (Chitosan, fibrin, and agar), as well as synthetic polymers such as poly (aldehyde gluconate), polyanhydrides and poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide), are biodegradable [

41].

5.3.2. Non-Biodegradable Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogels that are not capable of being decomposed by living organisms and thereby produce toxic substances are called non-biodegradable hydrogels. For the preparation of non-biodegradable polymeric hydrogels, numerous vinylated monomers such as 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate and acrylamide are used [

42].

5.4. Based on Configuration

Polymeric hydrogels can be classified into four types amorphous, semi-crystalline, crystalline, and hydrocolloid aggregates based on their physical structure and chemical composition.

5.4.1. Amorphous Hydrogel

Amorphous hydrogels also known as non-crystalline hydrogels are unshaped gel formulations used in dressing material. It consists of water, glycerin, polymer, and other products with no shape, primarily designed for wound hydration to a dry wound. Typically, they cannot absorb large amounts of exudate because of the high-water content of hydrogels. It promotes wound healing, granulation, and epithelialization, and facilitates autolytic debridement by providing a moist wound-healing environment. Amorphous hydrogel dressings are also available in sheet and non-woven sponges or impregnated gauzes [

43].

5.4.2. Semi-Crystalline Hydrogel

Semi-crystalline hydrogel, first developed in 1994, are moderately water-swollen hydrogels containing a complex mixture of amorphous and crystalline phases [

44].

5.4.3. Crystalline Hydrogels

Crystalline hydrogels are made up of covalently cross-linked hydrophilic polymer materials, distributed throughout a liquid medium in a crystalline lattice of periodically stacked nanoparticles. The crystalline lattice displays visible opalescence by Bragg diffraction from the crystalline hydrogel material [

45].

5.4.4. Hydrocolloid Aggregates

Hydrocolloid aggregates are made up of hydrophilic polymers mainly contains many hydroxyls group and polyelectrolytes. Due to their soft-solid texture, biocompatibility, and perception as a natural material, hydrocolloid aggregates of micron and sub-micron size are useful in many applications such as food, agricultural, pharmaceutical and chemical industries [

46].

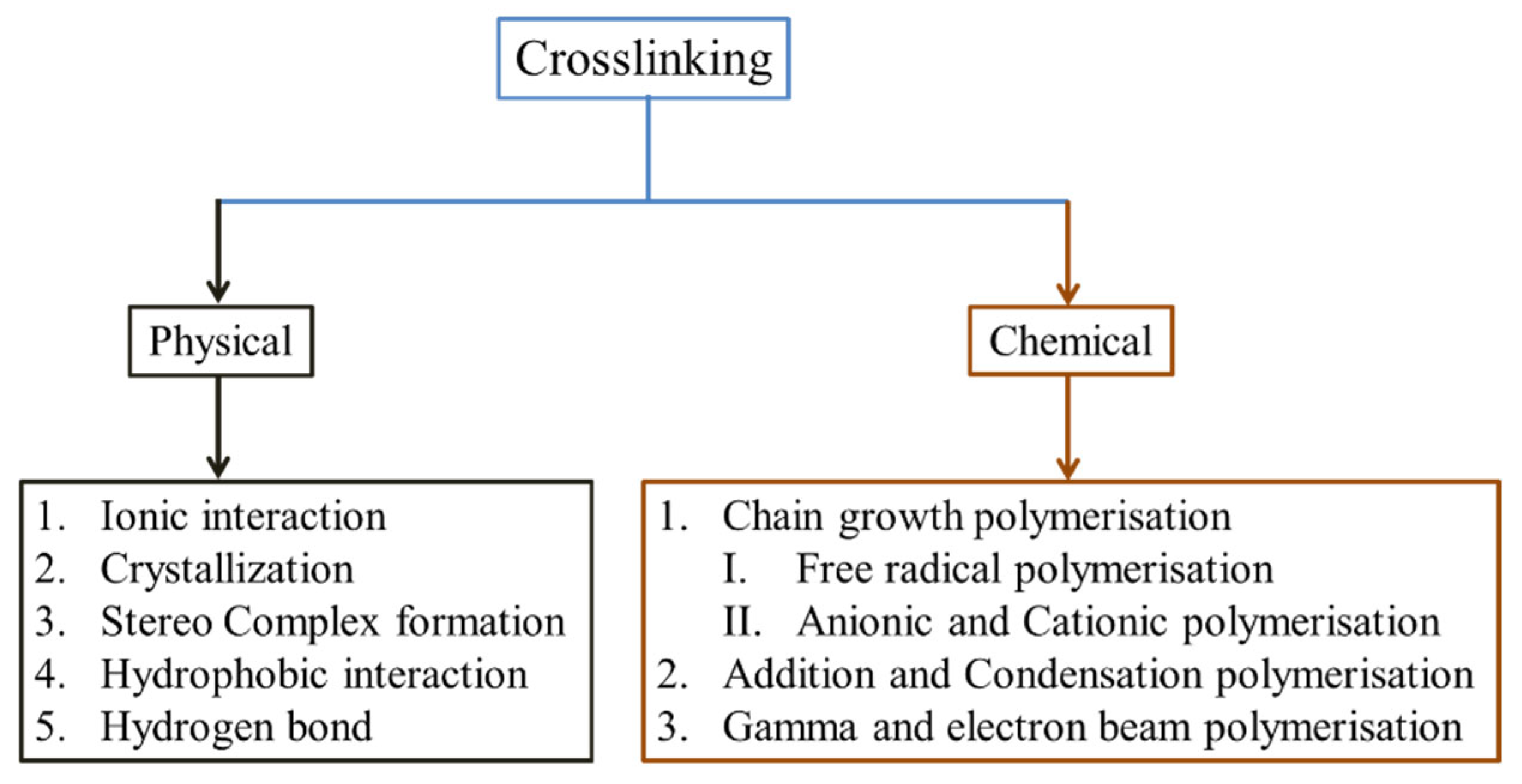

5.5. Based on Type of Crosslinking

Based on the nature of the crosslinking hydrogels are divided into physical and chemical hydrogels. Physical crosslinking is not permanent, but sufficient to make hydrogels. It includes entangled chains, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interaction, and crystallite formation. These crosslinking give reversible hydrogels. Chemical crosslinks are permanent and are formed by covalent crosslinking of polymers by polymerizing end-functionalized macromers (

Figure 6) [

47].

5.5.1. Physically Cross-Linked Hydrogels

Physically cross-linked hydrogels have temporary and weak cross-linked connections, which are formed by either polymer chain entanglements or physical interactions such as hydrogen bonding. There are different ways to synthesize physically cross-linked hydrogels such as ionic interaction, crystallization, complex formation, protein interaction, and hydrogen bonding [

48].

5.5.2. Chemically Cross-Linked Hydrogels

Chemically cross-linked hydrogels have permanent junctions and are synthesized by addition and condensation polymerization, chain-growth polymerization, and gamma and electron beam polymerization [

49].

5.6. Based on Physical Appearance

Depending on the technique of polymerization involved in the preparation process, hydrogels can be classified as matrix, film, or microsphere

5.7. Based on Charge

Based on the electrical charge located on the cross-linked chains polymeric hydrogels are classified into four types:

Neutral (Nonionic)

Anionic

Cationic

Ampholytic

Zwitter ionic

5.8. Based on Physical Property

5.8.1. Conventional Polymeric Hydrogels

Conventional hydrogels are the cross-linked network of polymer chains, which absorb a high amount of water when put in an aqueous media, and there is no change in the equilibrium swelling and other physical properties with the change in their surrounding environment. Due to high water contents similar to body tissues hydrogels are of special interest in the biological field and they are easily washed to remove impurities [

50].

5.8.2. Smart Polymeric Hydrogels

Smart polymeric hydrogels are cross-linked hydrogels capable of to respond external stimuli through immediate changes in the physical nature of the network. It can be planned in such a way as to undergo volume change in response to minute variations of environmental stimuli. For the development of stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems with reduced toxicity and enhanced therapeutic efficacy, smart hydrogels are perfect candidates. The most commonly used stimuli to trigger the hydrogel’s curative action are temperature and pH because they have biological and physiological relevance [

51]. The swelling of hydrogels in response to the external environment depend on two factors: (1) Polymer and solvent interaction and (2) Polymer elasticity

6. Technologies Adopted in Hydrogel Preparation

Polymeric hydrogels are cross-linked three-dimensional polymer networks having hydrophilic and viscoelastic properties. Sometimes hydrophobic monomers are used in the preparation of hydrogel to control its specific properties such as swelling and degradation for various applications. The preparation of polymeric hydrogels takes place by reacting polymers with multifunctional cross-linkers. There are several ways by which linear polymers are cross-linked to form hydrogels [

52].

Free radicals generation by ionizing radiation that combines as crosslink junctions.

Linking of polymer chains by chemical crosslinking.

Linking of polymer chains by physical interactions.

Generally, monomers, initiators, and cross-linker are three integral parts of the preparation of polymeric hydrogels.

6.1. Bulk Polymerization

Polymeric hydrogels can be formed by bulk polymerization or mass polymerization in which one or more types of monomers mainly vinyl monomers are used with a small amount of cross-linking agent. The initiation of the bulk polymerization reaction takes place by radiation, light, or catalysts. For polymerization reactions, the choice of initiator depends upon the type of monomers and solvents. Polymeric hydrogels prepared by bulk polymerization can be shaped in different forms such as particles, emulsions, rods, films, and membranes [

53].

6.2. Free Radical Polymerization

Polymeric hydrogels are prepared mainly from acrylates, vinyl lactams, and amide monomers because these polymers have suitable functional groups. The chemistry involved in this method is free-radical polymerizations, which include initiation, propagation, and termination steps. Initiation starts with radical generation by using a wide variety of initiators such as heat, light (UV and visible), and chemicals. Inactivated monomers are converted into activated form by reacting with radicals. Polymer chain elongation takes place when an activated form of monomers reacts with each other and finally, termination stops the reaction [

54].

6.3. Solution Polymerization or Cross-Linking

Solution polymerization or cross-linking is advantageous over bulk polymerization in presence of solvent serving as a heat sink. Water–ethanol mixture and water-ethanol-benzyl alcohol mixture are the examples of mostly used solvents in this method. In this type of crosslinking, polymeric hydrogels are formed when monomers are mixed with the multifunctional crosslinking agent, and polymerization is initiated thermally or by a redox initiator system. Polymeric hydrogels are washed several times with distilled water to remove the impurities from the gel matrix [

3].

7. Method of Crosslinking

Hydrogels are formed by the crosslinking of polymers such as alginate, chitosan, polyethene glycol, polymethacrylate, and polylactic acid. There are numerous known techniques available for the synthesis of polymeric hydrogels such as chemical crosslinking, physical crosslinking, and radiation cross-linking [

3].

7.1. Physical Crosslinking

Polymeric hydrogels made from physical crosslinking have been a topic of great interest because they are reversible, relatively easy to produce, and they do not need crosslinking agents. There are several known methods available such as heating or cooling, ionic interaction, hydrogen bonding, freeze-thawing, etc. for crosslinking to produce physical hydrogels [

3,

48].

Heating or Cooling: In this method, hydrogels are formed because of the intramolecular coil formation and association between the coils by applying heat. Hydrogels formed by carrageenan or gelatin are an example of this method.

Ionic Interactions: In this method, hydrogels are formed by the addition of counter ions as a crosslinker. Hydrogels formed by chitosan-glycerol phosphate salt and chitosan-polylysine are examples of this method.

Hydrogen Bonding: In this method, hydrogels are formed by hydrogen bonding that, involves reducing the pH of carboxyl groups containing polymer solutions. The hydrogel formed by CMC hydrogel is an example of this method.

Freeze Thawing: The principle behind this method is the microcrystal formation after freeze-thawing. The polymeric hydrogel formed by the cryogelation of xanthan is an example of this method.

7.2. Chemical Cross-Linking

The polymeric hydrogel formed by chemical crosslinking is permanent, irreversible, and needs a crosslinking agent. There are several known methods for chemical cross-linking such as the grafting process or polymer chain linkage by a crosslinking agent [

49].

Chemical cross-linkers- In this technique, a new molecule is added as a chemical cross-linking agent such as glutaraldehyde and epichlorohydrin for cross-linking of polymer chains to synthesize hydrogels.

Grafting- Grafting is a technique in which a monomer polymerizes on a preformed polymer support. There are two types of grafting: chemical grafting and radiation grafting.

Chemical grafting- In this method polymer chains are activated by chemical reagents such as N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone to graft starch with acrylic acid.

Radiation grafting- This method involves the formation of free radicals by exposing high-energy radiation onto the polymeric chain. There are three ways to perform this method: simultaneous or direct, pre-irradiation and pre-irradiation oxidative.

Advantages

- I.

Does not require the use of catalyst nor additives to initiate the reaction

- II.

Unchanged mechanical properties concerning the pristine polymeric matrix

7.3. Radiation Crosslinking

This method of crosslinking is very important and cost-effective because it does not require any chemical additives for cross-linking. Biopolymers used for biomedical applications are modified by the production of free radicals by exposure to a high-energy source [

49].

8. Characterization of Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogels are characterized mainly in two forms of hydrogel (1) swelled hydrogel (with water) and (2) dried hydrogel (without water). The structure of the swelled hydrogel might differ from the dried hydrogels due to the presence of water. In dried hydrogel, evaporated or sublimated water molecules leave void spaces between the cross-linked chains that result in structure collapse or shrinking. Characterization of Hydrogel consists of quantifying the composition, crosslinking density, space between the cross-linked chain, strength, orientation, and free and bound water in the hydrogel. Evaluating the structural behavior and hydrogel strength at changed concentrations, pH, temperatures, and ions is too important. Hydrogels are characterized by different parameters such as morphology, mechanical property, and swelling behavior. The structure of the hydrogel and its porosity is determined by morphological characterization. The mechanism of drug release from the hydrogel is characterized by swelling property and the strength and stability of the hydrogel and drug carriers are characterized by the third parameter elasticity [

49,

55].

8.1. Morphological Characterization

Morphological characterization is one of the most significant parameters in the evaluation of polymeric hydrogel properties. Numerous morphological properties of a polymeric hydrogel depend on the chemically cross-linked structure, its orientation in the matrix, and the pores formed between the polymer chains after crosslinking. The structure and morphology of a polymeric hydrogel can be revealed by both direct imaging and indirect scattering methods. A complete arrangement of polymeric hydrogels structural and morphological information can be provided by the combination of both microscopy and scattering methods with higher accuracy and at a fine resolution [

3,

49,

56].

8.1.1. Direct Imaging

Microscopy is a direct method that provides real-space images of the hydrogel structure that can be analyzed directly. On the other hand, the high-water content of polymeric hydrogels causes it difficult to probe them directly. Polymeric hydrogels are analyzed by high-resolution microscopy (SEM/TEM) in which samples are dried in a low-pressure chamber by simple evaporation or freeze-drying method [

57].

Drawback:

(1) Drying process of polymeric hydrogel in this process brings the high possibility of forming structural artifacts hence not trustworthy.

(2) The structural information in high-resolution microscopy is limited to a small area.

8.1.2. Indirect Imaging

Indirect imaging is a great method used to study the local structure of polymeric hydrogel over a larger volume of the original sample by X-ray diffraction or neutron scattering. The hydrogel structure can be resolved in the length scale ranging from 1 nm -1000 nm by scattering methods [58].

Drawback:

(1) Requirement of pre-knowledge or assumptions of the polymeric hydrogel structure to demonstrate broad data modeling by using fundamental models.

8.2. Mechanical Property of Hydrogels

Rheological characterization has become an increasingly important tool to obtain more information about the viscoelastic and flow properties of hydrogels based on peptides, proteins, and polymers. Common rheological studies conducted on hydrogel materials include measurement of shear storage modulus (G') (qualitatively the material stiffness), loss modulus (G'') (qualitatively the material liquid-like flow properties), and loss factor tan (δ) (the ratio of liquid-like behavior to solid-like behavior), measured as functions of time, oscillatory frequency, and oscillatory strain. Such studies can provide insight about gelation kinetics, linear viscoelastic regions, and relaxation timescales relevant to the studied hydrogels. Rheological characterization is the best method to measure the changes in the structures of polymeric hydrogel during phase transition i.e. formation (sol to gel) and breaking (gel to sol) of hydrogel assemblies [

59].

A commonly conducted measurement for studying the shear-thinning and reheeling behavior of physical hydrogels is the storage modulus evolution of a hydrogel immediately after it has been subject to steady-state shear of large amplitude by the upper plate of a bench-top rheometer [

60].

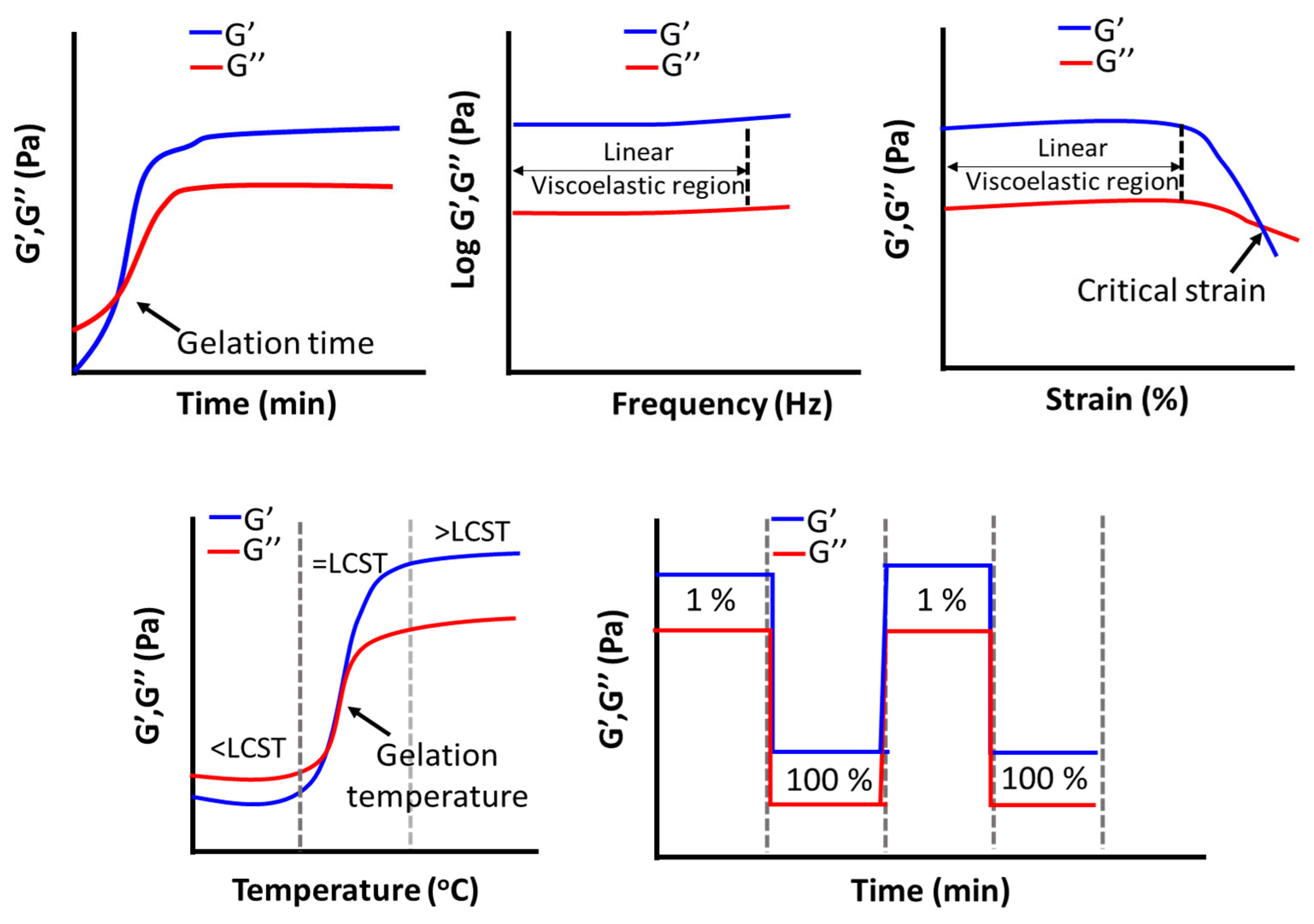

Figure 7. Shows the commonly measured rheological property to assess shear-thinning [

61].

Such a measurement often shows a significant reduction in the value of the storage modulus upon shearing and subsequent gradual storage modulus evolution post-shear cessation [

62]. Solid injectable hydrogels are subject to shear treatment usually using a rheometer and also, but less often, a syringe or capillary to study their under shear and post-shear behavior [

63].

8.2.1. Yield Stress of Hydrogel

Yield stress can be defined as the minimum stress that must be applied before the material really starts to flow [

64]. This is an important parameter for topical gels. Yield stress of these materials should be high enough so that they do not flow away on ejection out of tubes. It should not be too high to offer significant resistance during application by hand pressure. The cross-linked microgel structure where individual particles are closely packed with their neighbors is responsible for the yield stress [

65]. The magnitude of the yield stress is a measure of the strength of the closed-pack structure that must be exceeded for the material to flow appreciably [

66]. Four different methods were explored to measure the yield stress of the materials. The most convenient method for determining yield stress is from stress sweep test [

67].

Time Sweep: A time sweep test at constant frequency and constant at temperature 37

oC is used to monitor sol-to-gel transition for in-situ forming gel. The critical time at which the storage modulus is higher than the loss modulus is considered gelation time. The plateau time is the time when the storage modulus is constant [

68,

69].

Frequency & Strain Sweep: Both the frequency sweep and the strain sweep are well-known rheology tests that are regarded as essential for the comprehensive characterization of fluid and soft biological gels. These tests offer a fundamental insight into the physical strength and cohesion of the fluid and gels being evaluated. During these tests, the storage modulus, loss modulus, and complex viscosity are commonly determined as a function of frequency, with the frequency being given in radians or hertz. Experiments are carried out with the frequency being changed gradually while the amplitude remains the same throughout. The ability to determine the viscoelastic properties of soft materials as a function of timescale is one of the distinctive features of the frequency sweep test. The frequency sweep experiments are performed at constant strain and temperature with a change in frequency from 0.1 to 100 Hz. The graph is plotted with frequency on the x-axis and modulus (storage and loss) on the y-axis. The strain sweep experiment was performed at constant frequency and temperature with a change in strain (0.1 to 100 %). The graph is plotted with strain on the x-axis and log values of modulus (G' and G'') o the y-axis. The strain at which the storage modulus becomes less than the loss modulus is considered a critical strain [69-71].

Figure 7.

The schematic presentation of the graph plot represents the different experiments carried out in rheological study. Top panel- left to right: Time sweep, frequency sweep and strain sweep respectively. Bottom panel- left to right: Temperature sweep and creep recovery.

Figure 7.

The schematic presentation of the graph plot represents the different experiments carried out in rheological study. Top panel- left to right: Time sweep, frequency sweep and strain sweep respectively. Bottom panel- left to right: Temperature sweep and creep recovery.

Temperature Sweep: For thermos-responsive gel, the gelation temperature is measured by temperature sweep experiments. The gel undergoes changes from sol to gel at a specific temperature known as lower critical solution temperature (LCST). Here the modulus is measured as a function of change in temperature at a specific rate (1 to 2

OC per minute) at constant frequency and strain. The temperature at which the storage modulus becomes higher than the loss is noted as gelation temperature [

69,

71,

72].

Creep-recovery: In the process of selecting soft materials, some of the most important factors to take into consideration include, in addition to compressive strength, compressive resilience, and creep recovery capacity. Experiments involving creep and recovery are utilized so that the results of rheological measurements may be further validated, and the structures of hydrogels can be clarified [

71]. The lower strain and critical strain are applied in cyclic manner without break. The recovery in the modulus after applying critical strain indicates self-healing nature of materials.

Shear-Thinning Hydrogels

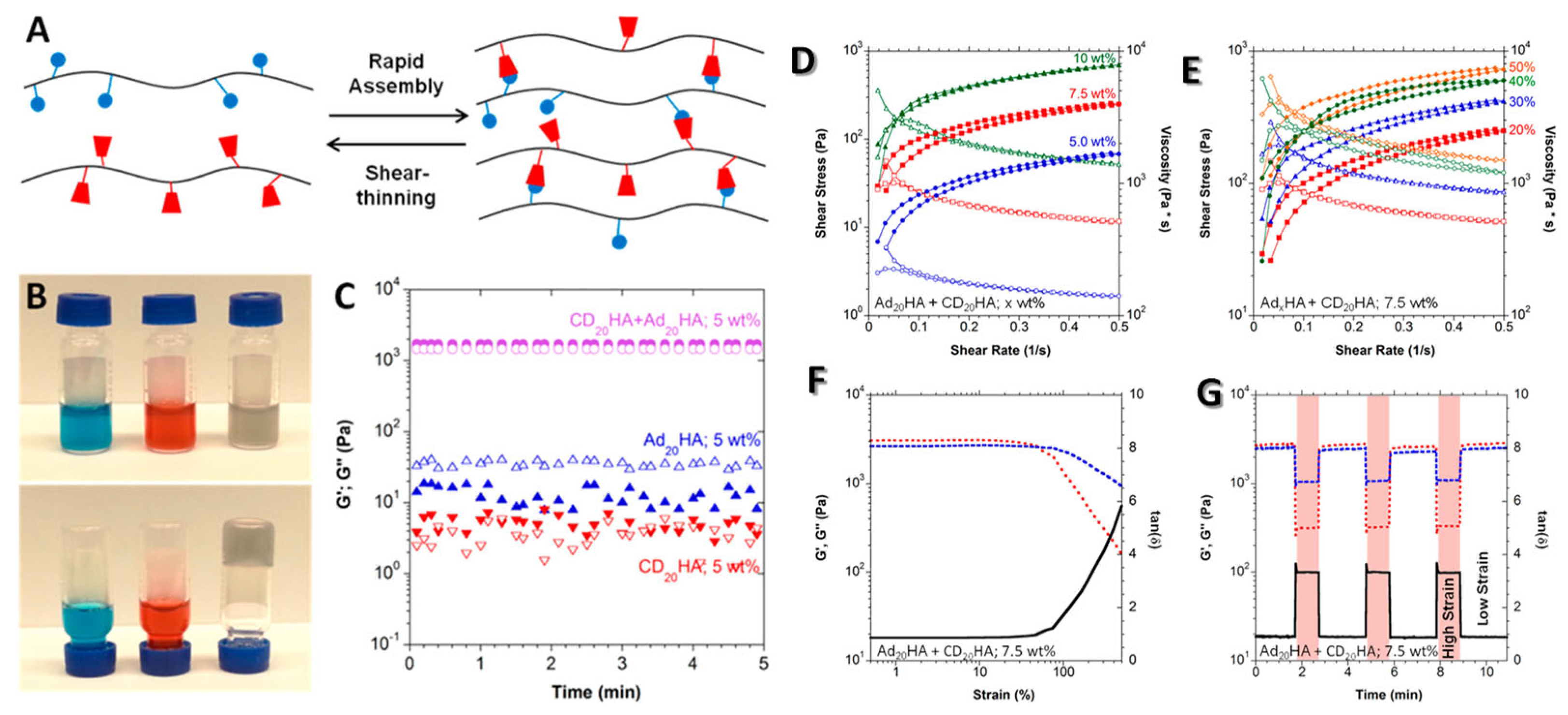

Hydrogels based on HA have been shown to develop when two macromer components are mixed together in water, as shown by Rodell et al. Interaction between adamantane- and -cyclodextrin-modified HA (guest macromer, Ad-HA, and host macromer, CD-HA) took place. The shear-thinning behavior and quick recovery of all the investigated hydrogel formulations made them simple to inject and helped keep the hydrogel and its possible therapeutic payload in the area of the injection. Hydrogel design showed amazing stability and tunability in the face of erosion and the release of model biomolecules. As a result of its demonstrated tunable mechanical properties, near-ideal flow and recovery characteristics, and remarkable stability toward erosion, which affords controlled long-term biomolecule release, the hydrogel system developed shows great poten-tial as a minimally invasive injectable material platform.

Figure 8.

Hydrogel formation. Guest–host complexation-based dynamic cross-link creation (A). (B) Qualitative inversion test: Ad20HA 5 wt % (blue, left), CD20HA (red, center), and CD20HA + Ad20HA (purple, right). (C) Oscillatory time sweeps of individual macromers and hydrogel produced at 5 wt%; storage modulus (G′, filled symbols) and loss modulus (G′′, unfilled symbols) at 10 Hz, 1.0% strain. Guest–host hydrogel recovery. Continuous flow studies of hydrogels with varying macromer concentrations (D) or Adx-HA modifications (E) as indicated by adjacent labels. Storage modulus (G′, red dotted line), loss modulus (G′′, blue dashed line), and loss tangent (tan(), black solid line) of a hydrogel during a strain sweep (F) or cyclic deformation (G) of 0.5% (low, unshaded regions) and 250% (high, shaded areas) strain at 10 Hz. 2013 ACS. [

73].

Figure 8.

Hydrogel formation. Guest–host complexation-based dynamic cross-link creation (A). (B) Qualitative inversion test: Ad20HA 5 wt % (blue, left), CD20HA (red, center), and CD20HA + Ad20HA (purple, right). (C) Oscillatory time sweeps of individual macromers and hydrogel produced at 5 wt%; storage modulus (G′, filled symbols) and loss modulus (G′′, unfilled symbols) at 10 Hz, 1.0% strain. Guest–host hydrogel recovery. Continuous flow studies of hydrogels with varying macromer concentrations (D) or Adx-HA modifications (E) as indicated by adjacent labels. Storage modulus (G′, red dotted line), loss modulus (G′′, blue dashed line), and loss tangent (tan(), black solid line) of a hydrogel during a strain sweep (F) or cyclic deformation (G) of 0.5% (low, unshaded regions) and 250% (high, shaded areas) strain at 10 Hz. 2013 ACS. [

73].

Shin et al. showed the multifunctionality of gallol moieties (three hydroxyl groups attached to benzene) (found in many vegetables and fruits) in the hydrogel network and developed gallol-rich hydrogels using HA-gallol conjugates and a gallol-rich cross-linker, oligo-epigallocatechin gallate OEG [

74]. Gallol-rich hydrogels had three unique properties: rapid and spontaneous gelation of gallol-containing polymers by multiple hydrogen bonds of gallol-togallol and gallol-to-polymeric backbone; shear-thinning by breaking and reforming the gal-lol-mediated extensive hydrogen bonds, yielding injectable hydrogels; and high protein loading and enzymatic degradation resistance due to gallol's high affinity to proteins. The gallol moieties will help biomedical applications achieve shear-thinning, injectable protein-encapsulated hydrogels with enzymatic resistance.

Figure 9.

(a) HA-Ga/OEGCG gallol-rich, shear-thinning hydrogels schematic. (b) Overlay of the HA-Ga/OEGCG bulk gel to show its transparency (400 μL) (top) and cross-sectional SEM image of the lyophilized gel (bottom). Frequency-sweep rheological investigation of the HA-Ga/OEGCG combination with a [d-glucuronic acid-d-N-acetylglucosamine]/[gallol in OEGCG] stoichiometric ratio of (c) 7, (d) 2, and (e) 0.5. Soft gels have 341.6 ± 53.6 Pa G′ modulus at 1 Hz at a ratio of 2. Gels have a G′ modulus of 1390.5 ± 128.0 Pa at 1 Hz at 0.5. (f) Shear rate-dependent viscosity for HA-Ga/OEGCG hydrogels with [HA unit]/[Gallol in OEGCG] ratios of 7 (blue), 2 (black), or 0.5 (red). (g) G′ recovery showing the hydrogel structure under alternate strain from 0.1% to 10% returning to 0.1%. The red arrow indicates G′ recovering to its starting value. (h) A 26 G needle (inner diameter = 0.26 mm) injects the HA-Ga/OEGCG hydrogel (ratio = 0.5). Copyright 2017 ACS, [

74]

.

Figure 9.

(a) HA-Ga/OEGCG gallol-rich, shear-thinning hydrogels schematic. (b) Overlay of the HA-Ga/OEGCG bulk gel to show its transparency (400 μL) (top) and cross-sectional SEM image of the lyophilized gel (bottom). Frequency-sweep rheological investigation of the HA-Ga/OEGCG combination with a [d-glucuronic acid-d-N-acetylglucosamine]/[gallol in OEGCG] stoichiometric ratio of (c) 7, (d) 2, and (e) 0.5. Soft gels have 341.6 ± 53.6 Pa G′ modulus at 1 Hz at a ratio of 2. Gels have a G′ modulus of 1390.5 ± 128.0 Pa at 1 Hz at 0.5. (f) Shear rate-dependent viscosity for HA-Ga/OEGCG hydrogels with [HA unit]/[Gallol in OEGCG] ratios of 7 (blue), 2 (black), or 0.5 (red). (g) G′ recovery showing the hydrogel structure under alternate strain from 0.1% to 10% returning to 0.1%. The red arrow indicates G′ recovering to its starting value. (h) A 26 G needle (inner diameter = 0.26 mm) injects the HA-Ga/OEGCG hydrogel (ratio = 0.5). Copyright 2017 ACS, [

74]

.

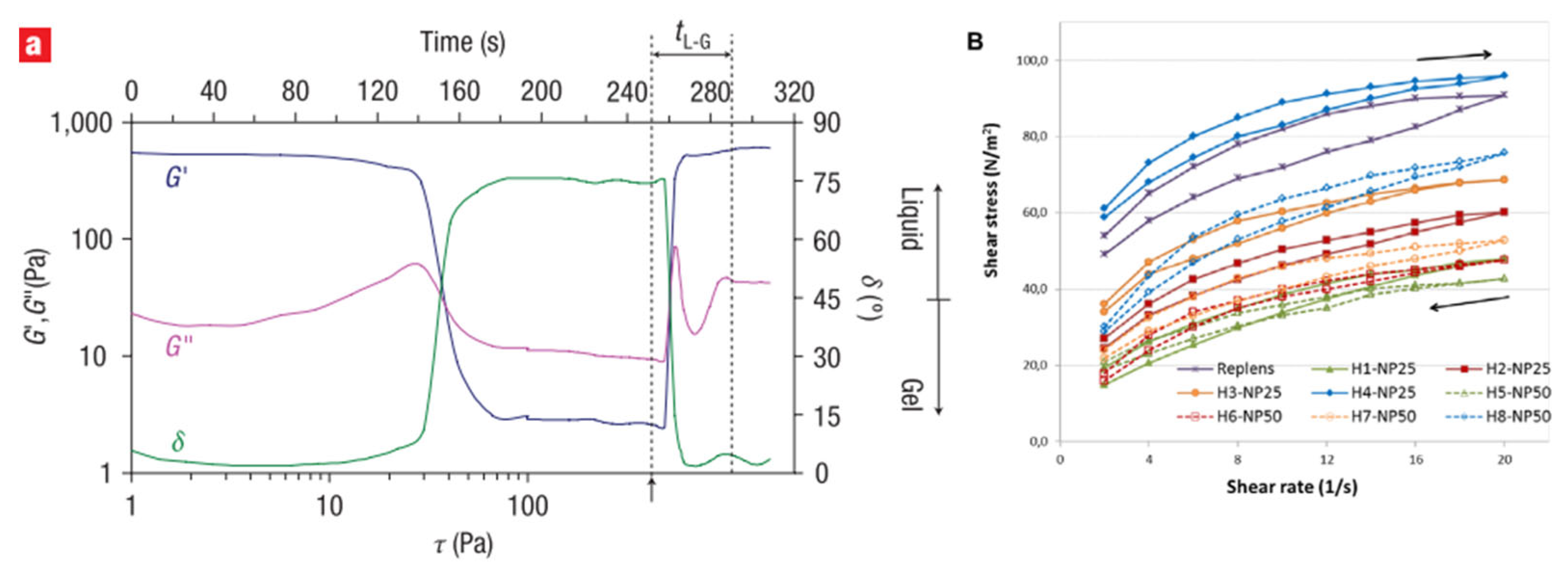

8.2.2. Determination of Thixotropic Behavior of Hydrogels

In dispersed systems, thixotropy arises when shear stress (viscosity) values measured by progressively increasing the shear rate are higher from those measured when one progressively decreases it [63]. Thixotropy is a kind of viscoelasticity that has a very long relaxation time caused by flow induced changes in structure that are generally erased after hours of quiescence (inactivity) [67,75]. In general, thixotropy has two main components: the shear thinning effect and the time dependence of viscosity [63]

Topical gels show thixotropy only at very high shear rates [65]. However, the amount of thixotropy is very low as evidenced by the proximity of the curves, although it must be noted that at such high shear rates, measurements become difficult and less reliable due to edge fracture and/or sample expulsion owing to high centrifugal forces. When the topical gels experience high shear rates, the network structure between neighboring microgel particles as well as the entanglements between long polymer chain segments break down. Therefore, the shear stresses or viscosities in decreasing shear rate curve are lower. The lower curve represents apparent shear stresses or viscosities of a long- lived metastable state induced by the highest shear rate in the samples recent past [67].

As thixotropy would also allow cells to be sub cultured without trypsinization, a process that has been reported to affect long-term cell quality, Pek et al conducted rheological method to determine thixotropic behavior of the PEG-silica hydrogels [76]. Typical G' and G'' of gels was determined as a function of increasing shear stress applied with time. It was found that when G'= G'', liquefaction occurred. The time taken for G' and G'' to return to their original levels when shear stress was removed was taken as the liquid-gel-transition time shown in

Figure 9(a) [77].

In another method to determine the thixotropic behavior of hydrogels, their structural breakdown on the increasing shear rate was assessed. As shown in figure 9(b) thixotropic properties of cabopol/TA-Ag nanocomposites, was evidenced by characteristic shifts of the lower curves in comparison to the upper ones which refers to ability to reverse viscosity loss and gel to sol transition. The observed facility of semi-solid formulations to recover more gradually after removing the shear stress followed with loss in their strength at body temperature might favor the uniform preparations’ spread ability over the mucosal surface after local application.

Figure 9.

(a) Determination of liquid-gel transition time of PEG-silica gel, (b) Hysteresis loops (expressed as shear stress vs. shear rate curves) of Carbopol 974P hydrogels with 25 ppm (H1-H4/NP25) or 50 ppm Ta-AgNPs concentration (H5–H8/NP50) and commercially available vaginal gel. Reproduced from [77].

Figure 9.

(a) Determination of liquid-gel transition time of PEG-silica gel, (b) Hysteresis loops (expressed as shear stress vs. shear rate curves) of Carbopol 974P hydrogels with 25 ppm (H1-H4/NP25) or 50 ppm Ta-AgNPs concentration (H5–H8/NP50) and commercially available vaginal gel. Reproduced from [77].

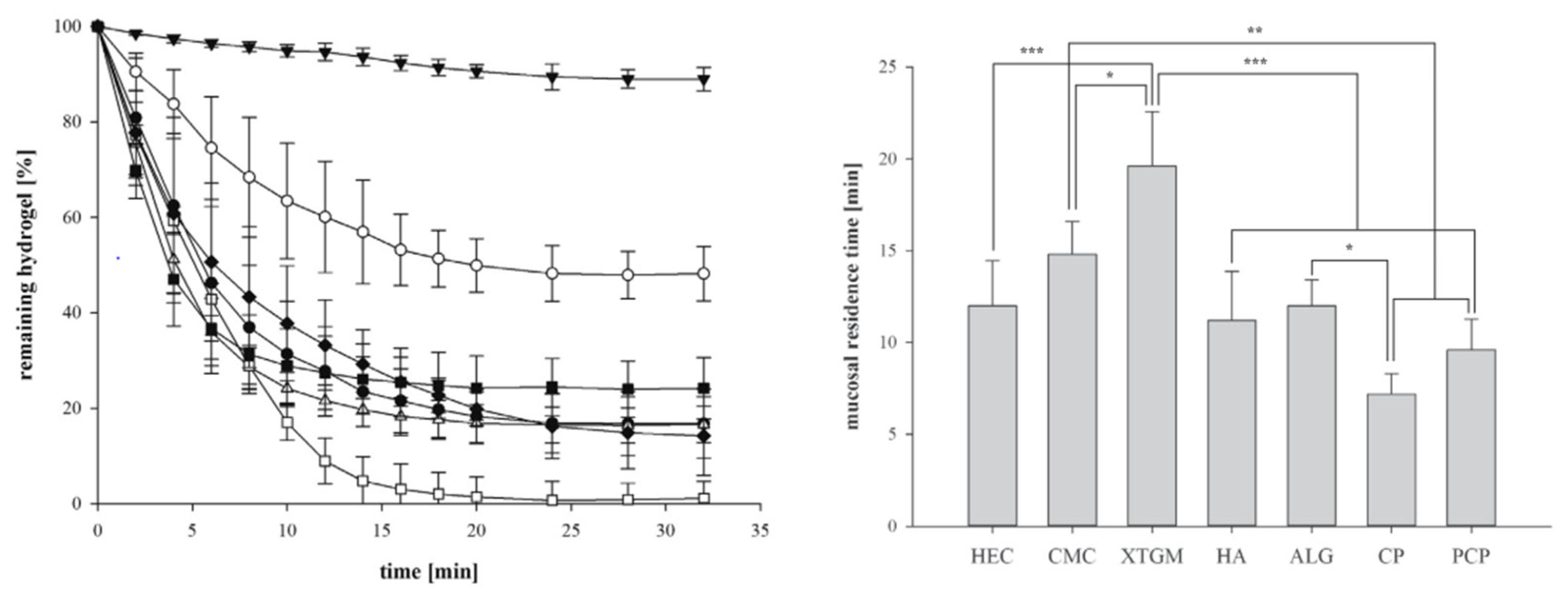

8.2.3. Determination of Mucoadhesive Property of Hydrogels

The extent of mucoadhesive properties of hydrogels, were assessed by means of different measurement principles, especially rheological as well as tensile studies [78]. Angela et al analyzed in vitro methods for the characterization of mucoadhesive hydrogels for their potential to predict the residence time on human buccal mucosa. Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), xanthan gum (XTGM), hyaluronic acid sodium salt (HA), sodium alginate (ALG), Carbopol (CP), and polycarbophil (PCP) were studied [79]. To assess the mucosal residence time of the hydrogel formulations, pieces of porcine buccal mucosa (3×3 cm) were mounted at an angle of 900 in an incubator with 100% humidity at 370C. When brought in contact with the excised buccal mucosa the hydrogels showed discrepancies in flow retention as shown in figure 10(a). Due to its in-situ gelling properties hydrogels comprising XTGM remained cohesive over the measurement period. A gradual wash off was observed for the other polysaccharide hydrogels. After dilution with artificial saliva the retention in the lower part of the mucosa is most pronounced for CMC. CP and PCP were dissolved and thereby removed from the site of application. Results of healthy volunteers revealed the same rank order of adhesion time as obtained for the percentage of remaining hydrogel from ex vivo studies figure. 10(b). Accordingly, XTGM remained significantly longer (p < 0.05) than other formulations on human buccal mucosa.

8.3. Swelling Behavior and Crosslinking Density

Water is the main constituent of the polymeric hydrogel system that is why swelling behavior is an important parameter in hydrogel characterization. The swelling ratio (SR) of the hydrogels determines the water content. Diffusion of water in polymeric hydrogels causes swelling that significantly changes the volume by expanding its network structure, which affects the mechanical property. The effect of swelling on the structure of polymeric hydrogels is mostly affected by crosslinking density, solvent nature, charge, pH, and polymer-solvent interaction [

80]. The swelling ratio of a polymeric hydrogel is determined by relating the dry mass to the wet mass of hydrogel and the percentage swelling is calculated by the below-given formula:

where WD: Dry mass of hydrogel and WS: Swollen mass of hydrogel

Figure 10.

(a)Ex vivo mucosal residence time of HEC (●), CMC (○), XTGM (▾), HA (△), ALG (■), CP (□), PCP (♦) on porcine buccal mucosa mounted in an angle of 90° at 37 °C, 100% humidity. (b) In vivo mucosal residence time of hydrogels on buccal mucosa. Values are means of five volunteers ± standard deviation. Copyright 2019 ELSEVIER [

79]

.

Figure 10.

(a)Ex vivo mucosal residence time of HEC (●), CMC (○), XTGM (▾), HA (△), ALG (■), CP (□), PCP (♦) on porcine buccal mucosa mounted in an angle of 90° at 37 °C, 100% humidity. (b) In vivo mucosal residence time of hydrogels on buccal mucosa. Values are means of five volunteers ± standard deviation. Copyright 2019 ELSEVIER [

79]

.

9. Applications of Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogels are flexible due to their water content. Its specific structure, function, and compatibility with different conditions make them a potential candidate to use in different fields such as industrial, biomedical, and pharmaceutical sciences [

81]. The applications of polymeric hydrogel in biomedical sciences are extended due to its chemical behavior in biological environments and the biocompatibility of the materials used to produce them[

82,

83]. Some major, not complete but most practical applications of polymeric hydrogel in medicine are listed below [

84].

9.1. Drug Delivery

The existence of some important structural requirements in polymeric hydrogel such as storage and release rate make them an effective drug delivery system. Polymeric hydrogels are used to overcome the limitations of regular drug formulations by delivering drugs at certain rates for predefined periods. Polymeric hydrogels can be used to mask the bitter taste and odor of pharmaceutical agents. The polymeric hydrogel can improve solubilization, sustained release, enhanced stability, and bioactivity of lipophilic drugs. Thus, polymeric hydrogels have great potential for drug delivery application [

85,

86].

9.2. Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering also defined as ''regenerative medicine'' is an emerging area in the 21

st century that focuses on life science research to produce biological alternatives of damaged tissues and organs to maintain, repair, or improve the morphology and function by applying principles and methods of cell biology and engineering. Precisely, donor cells are amplified and seeded on a biodegradable three-dimensional scaffold for growth. Then, the resulting scaffold cell complex is implanted at targeted sites into the body where they remain to multiply and display an extracellular matrix. As soon as the three-dimensional scaffold degrades, new tissues or organs will form in place of damaged tissues or organs bearing the same shape and function [

87].

9.3. Contact Lenses

Contact lenses, a small ophthalmic device positioned directly on the cornea for correcting vision or changing eye color are a key area to use polymeric hydrogels for bio applications. In 1508, Leonardo da Vinci first described the concept of contact lenses by immersing the eye in a bowl of water. At the end of 1960, Professor Otto Wichterle developed poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) lenses, the most important step in contact lens development because of their several advantages such as high water content, oxygen permeability, stability, and tunable mechanical properties. Contact lenses positioned directly on the cornea surface prevent the exchange of atmospheric oxygen causes hypoxic stress and mechanical stress. Polymeric hydrogels used for the preparation of contact lenses must be biocompatible, permeability towards oxygen, good mechanical property, comfortable to wear, hydrolytic stable, and can support in the treatment of eye diseases [

88].

9.4. Biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device that is used to sense and report a biophysical property of the system under analysis. The existence of a biological recognition component is a common feature of all biosensors that allows the analysis of biological data. Biosensors are becoming more widely used as functional methods in several fields, including point-of-care research, home diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. The bio element, or biological recognition component, is made up of various structures such as enzymes, antibodies, living cells, or tissues, but the point is that it is unique to one analyte and has no reaction to other interferents. Depending on the nature of the analyte, different types of sensing components are used, but they can be divided into two groups: molecular interactions and living sensors. Molecular interactions- Different pathways are involved in the molecular interactions that are used to detect analytes. Enzyme-substrate interactions, organic-phase alcohols, amino acids, ammonia, urea, glucose, hydrogen peroxide, and other sensors dependent on enzyme-substrate interactions in hydrogel matrices are only a few examples. Glucose-responsive hydrogels that can serve as long-term insulin depots and automatically release insulin doses at appropriate times in response to elevated blood glucose levels that eliminate the need for repeated injections [

89].

Another form of affinity-based devices is based on antigen-antibody molecular interactions, with coupling of immunochemical reactions. The general concepts of these sensors are to identify the antibodies (or antigens) which are immobilized on a transducer to generate signals in response to the concentration of the analyte. The analyte can be detected using quartz crystal microgravimetry (QCM), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), or electrochemical methods. There are some other examples of analyte sensing based on molecular interactions, such as nucleotide, oligonucleotide, DNA, and so on.

Living sensors are another type of sensing feature. They are living cell-polymer composites made up of hydrogels, living cells, and microorganisms for biosensing applications. Microorganisms are suitable as biological sensing materials because they can detect a wide variety of chemical compounds, are genetically modifiable, and have a wide pH and temperature operating range. The key advantages of hydrogels are their 3D structures, high water content, and biocompatibility, which allow them to entrap cells or bacteria within their networks, allowing them to exchange gases at high rates and nourish the entrapped cells, allowing cell-polymer composites to be used in biosensors.

Polymeric hydrogels can be used in biosensors in two ways: they can be coated on the surface of a sensing system, or they can be used as a 3D matrix to keep bio element alive. Other applications in this category include cell preservation in a hydrogel matrix for specific time periods and pathogen detection [

90].

9.5. Wound Dressing

Polymeric hydrogels, when used as a wound dressing, provide a physical barrier that keeps the wound moist and facilitates wound healing by retaining water and drugs in their cross-linked three-dimensional structure. They can hold and retain wound exudates due to their water-holding capacity. Hydrogel can also fill irregularly formed wounds perfectly and effectively cope with deep bleeding. When applied, gelatin and sodium alginate-based hydrogels will cover the wound and protect it from bacterial infection [

80].

10. Current Status Concerning their Synthesis and Formulations of Polymeric Hydrogels

Polymeric hydrogel is an important class of functional materials that can react to specific stimuli like pH and temperature [

11]. Polymeric hydrogels are the most appropriate functional materials that are identical to the natural extracellular matrix (ECM). Polymeric hydrogels are used as an artificial material for cell scaffolds, implantable devices, and artificial tissue. The versatility of manufacturing tactics is demonstrated using polymeric hydrogels as a structural material for chemotaxis applications, DNA recognition motifs, and improved synthetic methods. This area of biomaterials research has been revitalized by new approaches to hydrogel design [

11].

However, the precise design of the polymeric hydrogels remains a significant challenge for scientists. The construction of well-arranged, three-dimensional structures of polymeric hydrogel with broad scales range is especially challenging. Most polymeric hydrogels published so far have been based on microstructural dimensions and morphologies, rather than strength and stability. In comparison with natural biological tissue, the strength of the synthesized polymeric hydrogels is still weak [

91]. For synthesizing polymeric hydrogels with high strength can be developed with new techniques with in-situ cell encapsulation ability. A novel way, 3D bioprinting has unwrapped recently for manufacturing polymeric hydrogels with complex shapes, high strength, and dimensions in broad-scale range [

92]. Moreover, clinical research on producing polymeric hydrogel constructs in the nanoscale range should be more focused. On the way forward, there will be many obstacles, but the scientific potential of polymeric hydrogel makes it confident functional biomaterial in the future.

11. Limitations of Hydrogels

In the last few decades, hydrogels have played a significant role as an interesting material for drug delivery, cell delivery, regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering applications. Stimuli-responsive hydrogel releases the entrapped therapeutics from the hydrogel matrix when it is exposed to some stimuli. Apart from several advantages, there are many limitations of hydrogels [

93].

Hydrogels are difficult to handle and load since they tend to be fragile. The strength of the hydrogels is reduced by spatial inhomogeneity (the existence of an inhomogeneous crosslink density distribution) [

94]. Hydrogels need a secondary dressing due to their non-adherent property. Hydrogels are not preferred for the treatment of exudation wounds because they are not very absorptive. In contact lenses, hydrogels cause lens deposition, hypoxia, dehydration, and eye reaction. Due to soft structures, these classes of materials also have low mechanical strength. Polymeric hydrogels prepared from natural polymers are biodegradable and biocompatible. However, isolating them from the biological tissue is difficult because they mimic and resemble the biological tissue and they have limited flexibility [

95].

On the other hand, synthetic polymeric hydrogels may not be biocompatible or biodegradable. Sterilization of synthetic polymeric hydrogels can potentiate the harmful effects of the sterilizing processes due to the presence of water in these materials [

96]. Another challenge in the polymeric hydrogel system is coordinating the degradation rate according to the type of application. The method of crosslinking affects release profiles, and chemical cross-linkers pose a toxicity risk [

97]. Polymeric hydrogel systems, on the other hand, are one of the most complex systems with properties that can be changed, and they're useful in understanding the fundamentals of cell-matrix interactions, which are important for tissue regeneration.

12. Strategies to Overcome the Mechanical Limitations

Traditional hydrogels are mainly prepared by chemical cross-linking. A non-uniform gel network is formed due to the non-uniform dispersion of a chemical crosslinking and the resulting hydrogel is very weak and delicate, which significantly limits its application. Four major types of novel network structures have been investigated to overcome the mechanical limitations in traditional hydrogels [

98]:

- i.

Uneven distribution of covalent bonds causes damage in network structure that can be reduced by changing the covalent cross-linking points by active cross-linking sites.

- i.

ii. The strength and flexibility of polymeric hydrogels can be improved by the introduction of another network in a certain network system (e.g., double network polymeric hydrogels) [

71].

- i.

iii. The physical adsorption or chemical bonding between the polymer chains and nanoparticles as multifunctional crosslinking points can improve the mechanical properties of hydrogels by dissipating energy; on the other hand, the hydrogels are strengthened by the high surface area and modulus of nanoparticles.

- i.

iv. Strong, robust, and stimuli-responsive hydrogels made from polymers prepared through non-covalent interactions and supramolecular self-assembling structures [

99].

13. Future Perspectives

The characteristic feature of hydrogels makes them one of the pioneer components in healthcare applications. Over the last few decades, there is a change in strategies, construction, properties, and applications for the development of more sophisticated hydrogel systems in regenerative medicine [

22]. Present research on hydrogels is focused on modifying polymer’s chemistry that leads to a substantial development in the mechanical and biological properties. Continuous efforts were made to modify hydrogels for specific applications (such as stimuli-responsive hydrogel) by investigating their neighboring microenvironments and exploiting these functional improvements [

69,

100,

101].

Most of the literature shows a bright future for hydrogel studies. New ideas on hydrogel design with significantly improved mechanical properties, controlled degradation rate, super absorbent with fast-drying and genetically engineered copolymers hydrogel have a bright future [

69,

71,

82].

Finally, despite significant improvements in bioengineering methods to fabricate hydrogel, several factors (such as microstructures, time of reaction, surface hybridization, rate of degradation, inflammation, and immunological response) of these hydrogels need a careful assessment to synthesize hydrolytic stable and biocompatible hydrogels for various pharmaceutical and biomedical applications [

102,

103]. These hydrogels can be used in the treatment of numerous diseases in a much safer way [

104,

105].

14. Conclusions

The past few decades have shown the advancement of polymer-based hydrogel material supported by improvements in polymer chemistry, its fabrication methods, and vital understanding in the field of cell biology. Current research in the field of polymer-based hydrogel networks as a smart material has been designed and tailored with remarkable applications, especially in pharmaceutical and biomedical fields.

This review shows the literature concerning polymer-based hydrogel materials, properties, advantages, disadvantages, classification, preparation, characterization, and applications on different bases with their limitation and future aspects. It also highlights the technologies adopted in hydrogel construction together with the method of crosslinking and status concerning their synthesis and fabrication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization-A.K.; writing (original draft preparation)- A.K, P.P.; writing (review and editing)- A.K., N.B., D.V.B., A.K.S..; supervision-A.K.S.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

References

- Wichterle, O.; LÍM, D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature 1960, 185, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, J.; Shukla, V.K. Cross-linking in Hydrogels - A Review. 2014.

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. Journal of Advanced Research 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Sun, Y.; Kaplan, J.A.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Parquette, J.R. Photo-crosslinking of a self-assembled coumarin-dipeptide hydrogel. New Journal of Chemistry 2015, 39, 3225–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kaplan, J.A.; Shieh, A.; Sun, H.-L.; Croce, C.M.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Parquette, J.R. Self-assembly of a 5-fluorouracil-dipeptide hydrogel. Chemical Communications 2016, 52, 5254–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhulsel, M.; Vignes, M.; Descroix, S.; Malaquin, L.; Vignjevic, D.M.; Viovy, J.L. A review of microfabrication and hydrogel engineering for micro-organs on chips. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1816–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Tang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Z. Applications of Hydrogels with Special Physical Properties in Biomedicine. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroia, J.; Yan-en, W.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, K.; Lu, T.; Zhang, B. A review on biocompatibility nature of hydrogels with 3D printing techniques, tissue engineering application and its future prospective. Bio-Design and Manufacturing 2018, 1, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Song, C.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J. Hydrogel-Based Controlled Drug Delivery for Cancer Treatment: A Review. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2020, 17, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Bae, K.H.; Kurisawa, M. Recent advances in the design of injectable hydrogels for stem cell-based therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2019, 7, 3775–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakahata, M.; Linke, P.; Kaufmann, S. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels as a model of the dynamic cellular microenvironment. Polymer Journal 2020, 52, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.M.; Liu, X. Advancing biomaterials of human origin for tissue engineering. Prog Polym Sci 2016, 53, 86–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorković, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Hydrogels: Characteristics and Application as Delivery Systems of Phenolic and Aroma Compounds. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. L. Hukins, D.; C. Leahy, J.; J. Mathias, K. Biomaterials: defining the mechanical properties of natural tissues and selection of replacement materials. Journal of Materials Chemistry 1999, 9, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, M.C.; Sun, J.Y.; Mehta, M.; Johnson, C.; Arany, P.R.; Suo, Z.; Mooney, D.J. Performance and biocompatibility of extremely tough alginate/polyacrylamide hydrogels. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8042–8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariba, G.; Farahani, S.V.; Faraahani, E.V. THEORETICAL DESCRIPTION OF HYDROGEL SWELLING: A REVIEW. 2010.

- M.J.A.D., Z.M.; Kabiri, K. Superabsorbent Polymer Materials: A Review. 2008.

- Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Li, Q.; Kawazoe, N.; Chen, G. Functional Hydrogels With Tunable Structures and Properties for Tissue Engineering Applications. Frontiers in Chemistry 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.A.; Su, Y.; Wang, D. Mechanical properties of PNIPAM based hydrogels: A review. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 70, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.; Koh, R.H.; Shim, W.; Kim, H.D.; Yim, H.G.; Hwang, N.S. Riboflavin-induced photo-crosslinking of collagen hydrogel and its application in meniscus tissue engineering. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2016, 6, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragan, E.S. Design and applications of interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels. A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 243, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, B.V.; Khurshid, S.S.; Fisher, O.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Peppas, N.A. Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Advanced Materials 2009, 21, 3307–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; Ye, Y.N.; Yu, C.; Li, X.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J.P. Stress Relaxation and Underlying Structure Evolution in Tough and Self-Healing Hydrogels. ACS Macro Letters 2020, 9, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hsu, S.-h. Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Self-healing Hydrogels. Frontiers in Chemistry 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogsgaard, M.; Behrens, M.A.; Pedersen, J.S.; Birkedal, H. Self-Healing Mussel-Inspired Multi-pH-Responsive Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, J.H.; Zhou, J.; Xu, F.; Zrínyi, M.; Dussault, P.H.; Osada, Y.; Chen, Y.M. Self-healing gels based on constitutional dynamic chemistry and their potential applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43, 8114–8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Chuo, T.-W. Self-healing polymers based on thermally reversible Diels–Alder chemistry. Polymer Chemistry 2013, 4, 2194–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikada, Y. Section 11 - Biocompatibility of hydrogels. In Gels Handbook, Osada, Y., Kajiwara, K., Fushimi, T., Irasa, O., Hirokawa, Y., Matsunaga, T., Shimomura, T., Wang, L., Ishida, H., Eds.; Academic Press: Burlington, 2001; pp. 388–407. [Google Scholar]

- Annabi, N.; Nichol, J.W.; Zhong, X.; Ji, C.; Koshy, S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dehghani, F. Controlling the porosity and microarchitecture of hydrogels for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2010, 16, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastropietro, D.J.; Omidian, H.; Park, K. Drug delivery applications for superporous hydrogels. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2012, 9, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Systems; Pros and Cons. Trends in Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019, 5, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrade Del Olmo, J.; Perez Gonzalez, R.; Saez-Martinez, V. Injectable Hydrogels: From Laboratory to Industrialization. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M Khansari, M.; Sorokina, L.; Mukherjee, P.; Mukhtar, F.; Rezazadeh Shirdar, M.; Shahidi, M.; Shokuhfar, T. Classification of Hydrogels Based on Their Source: A Review and Application in Stem Cell Regulation. JOM 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catoira, M.C.; Fusaro, L.; Di Francesco, D.; Ramella, M.; Boccafoschi, F. Overview of natural hydrogels for regenerative medicine applications. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2019, 30, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.; da Silva Morais, A.; Silva-Correia, J.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L. Natural-Based Hydrogels: From Processing to Applications. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology; pp. 1-27.

- Kumar, A.C.; Erothu, H. Synthetic Polymer Hydrogels. In Biomedical Applications of Polymeric Materials and Composites; 2016; pp. 141-162.

- Cai, M.-H.; Chen, X.-Y.; Fu, L.-Q.; Du, W.-L.; Yang, X.; Mou, X.-Z.; Hu, P.-Y. Design and Development of Hybrid Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: Recent Trends in Anticancer Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Qiao, B.; Nguyen, T.D.; Vincent, M.P.; Bobbala, S.; Yi, S.; Lescott, C.; Dravid, V.P.; Olvera de la Cruz, M.; Scott, E.A. Homopolymer self-assembly of poly(propylene sulfone) hydrogels via dynamic noncovalent sulfone–sulfone bonding. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begam, T.; Nagpal, A.; Singhal, R. A study on copolymeric hydrogels based on acrylamide-methacrylate and its modified vinyl-amine-containing derivative. Designed Monomers and Polymers - DES MONOMERS POLYM 2004, 7, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E.S. Advances in interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels and their applications. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2014, 86, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, K.R.; Park, K. Biodegradable hydrogels in drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 1993, 11, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazato, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, R.; Thongthai, P.; Sasaki, J.I. Non-biodegradable polymer particles for drug delivery: A new technology for "bio-active" restorative materials. Dent Mater J 2017, 36, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agren, M.S. An amorphous hydrogel enhances epithelialisation of wounds. Acta Derm Venereol 1998, 78, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, O. Semicrystalline physical hydrogels with shape-memory and self-healing properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2019, 7, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Marquez, M.; Hu, Z. The formation of crystalline hydrogel films by self-crosslinking microgels. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burey, P.; Bhandari, B.; Howes, T.; Gidley, M. Hydrocolloid Gel Particles: Formation, Characterization, and Application. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2008, 48, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R. Cross-Linked Hydrogel for Pharmaceutical Applications: A Review. Adv Pharm Bull 2017, 7, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Gan, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, H. Physically Crosslinked Hydrogels Based on Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) and Fish Gelatin for Wound Dressing Application: Fabrication and Characterization. Polymers 2020, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Hanif, M.; Ranjha, N.M. Methods of synthesis of hydrogels … A review. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2016, 24, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Conventional and Environmentally-Sensitive Hydrogels for Medical and Industrial Uses: A Review Paper. In Polymer Gels: Fundamentals and Biomedical Applications, DeRossi, D., Kajiwara, K., Osada, Y., Yamauchi, A., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1991; pp. 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Samal, S.K.; Dash, M.; Dubruel, P.; Van Vlierberghe, S. 8 - Smart polymer hydrogels: properties, synthesis and applications. In Smart Polymers and their Applications, Aguilar, M.R., San Román, J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: 2014; pp. 237-270.

- Elsayed, M.M. Hydrogel Preparation Technologies: Relevance Kinetics, Thermodynamics and Scaling up Aspects. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2019, 27, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasundara, L.; Gabriele, B.; Figoli, A.; Ok, Y.S.; Bundschuh, J. Hydrogels: Novel materials for contaminant removal in water—A review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2020, 51, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantha, S.; Pillai, S.; Khayambashi, P.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, O.; Pham, H.; Tran, S. Smart Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Materials 2019, 12, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Garnier, G. Characterisation of hydrogels: Linking the nano to the microscale. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 274, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.S.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M.S.; Zaman, A.; Ahmed, T.; Biswas, S.; Sharmeen, S.; Rashid, T.U.; Rahman, M.M. Morphological Characterization of Hydrogels. In Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels, Mondal, M.I.H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 819–863. [Google Scholar]

- Kisley, L.; Miller, K.A.; Guin, D.; Kong, X.; Gruebele, M.; Leckband, D.E. Direct Imaging of Protein Stability and Folding Kinetics in Hydrogels. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 21606–21617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.C.; Goh, C.Y.; Jones, F.; Mocerino, M.; Skelton, B.W.; Becker, T.; Ogden, M.I. Investigating hydrogel formation using in situ variable-temperature scanning probe microscopy. Chemical Science 2015, 6, 6133–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marapureddy, S.G.; Thareja, P. Structure and Rheology of Hydrogels: Applications in Drug Delivery. In Biointerface Engineering: Prospects in Medical Diagnostics and Drug Delivery, Chandra, P., Pandey, L.M., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Raeburn, J.; Sutton, S.; Spiller, D.G.; Williams, J.; Sharp, J.S.; Griffiths, P.C.; Heenan, R.K.; King, S.M.; Paul, A.; et al. Tuneable mechanical properties in low molecular weight gels. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9721–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.-Y.; Shi, J.-M.; Chi, Y.-H. Tannic Acid Physically Cross-Linked Responsive Hydrogel. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2018, 219, 1800234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naé, H.N.; Reichert, W.W. Rheological properties of lightly crosslinked carboxy copolymers in aqueous solutions. Rheologica Acta 1992, 31, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno Contreras, M.J.; Ramírez Diéguez, A.; Jiménez Soriano, M.M. Rheological characterization of hydroalcoholic gels--15% ethanol--of Carbopol Ultrez 10. Farmaco 2001, 56, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H. A Brief History of the Yield Stress. Applied Rheology 2019, 9, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N.; Ciotti, S.; Ackermann, C. Rheological characterization of topical carbomer gels neutralized to different pH. Pharm Res 2004, 21, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavikutty, A.S.; Ohta, S.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Qi, P.; Ito, T. Analysis of endoscopic injectability and post-ejection dripping of yield stress fluids: Laponite, Carbopol and Xanthan Gum. Journal of Chemical Engineering of Japan 2021, 54, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M.; Vermant, J. The Structure and Rheology of Complex Fluids. Applied Rheology 2019, 10, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutan, B.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Biswas, A.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, A.; Maiti, P.; Jewrajka, S.K. Gold Nanoparticle Promoted Formation and Biological Properties of Injectable Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3782–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Anuradha; Biswas, A. ; Jewrajka, S.K. Injectable amphiphilic hydrogel systems from the self-assembly of partially alkylated poly(2-dimethyl aminoethyl) methacrylate with inherent antimicrobial property and sustained release behaviour. European Polymer Journal 2022, 179, 111559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutan, B.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Jewrajka, S.K. Liquid Prepolymer-Based in Situ Formation of Degradable Poly(ethylene glycol)-Linked-Poly(caprolactone)-Linked-Poly(2-dimethylaminoethyl)methacrylate Amphiphilic Conetwork Gels Showing Polarity Driven Gelation and Bioadhesion. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2018, 1, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nutan, B.; Jewrajka, S.K. Modulation of Properties through Covalent Bond Induced Formation of Strong Ion Pairing between Polyelectrolytes in Injectable Conetwork Hydrogels. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2021, 4, 3374–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Chandel, A.K.; Kannan, D.; Nutan, B.; Singh, S.; Jewrajka, S.K. Dually crosslinked injectable hydrogels of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly[(2-dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate]-b-poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) as a wound healing promoter. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2017, 5, 4955–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodell, C.B.; Kaminski, A.L.; Burdick, J.A. Rational design of network properties in guest-host assembled and shear-thinning hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 4125–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, H. Gallol-Rich Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels: Shear-Thinning, Protein Accumulation against Concentration Gradients, and Degradation-Resistant Properties. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salome Amarachi, C.; Attama, A.; Kenechukwu, F. Nanoemulsions — Advances in Formulation, Characterization and Applications in Drug Delivery. 2014.

- Pek, Y.S.; Wan, A.C.; Shekaran, A.; Zhuo, L.; Ying, J.Y. A thixotropic nanocomposite gel for three-dimensional cell culture. Nat Nanotechnol 2008, 3, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymańska, E.; Orłowski, P.; Winnicka, K.; Tomaszewska, E.; Bąska, P.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J.; Basa, A.; Krzyżowska, M. Multifunctional Tannic Acid/Silver Nanoparticle-Based Mucoadhesive Hydrogel for Improved Local Treatment of HSV Infection: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedevi Madhavikutty, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K.; Tsai, C.C.; Inagaki, N.F.; Ohta, S.; Ito, T. pH responsive cationic guar gum-borate self-healing hydrogels for muco-adhesion. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2023, 24, 2175586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus, R.A.; Zahir-Jouzdani, F.; Dünnhaupt, S.; Atyabi, F.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Mucoadhesive hydrogels for buccal drug delivery: In vitro-in vivo correlation study. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2019, 142, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, S.; Klar, A.S. Advanced Hydrogels as Wound Dressings. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K.; Uday Kumar, C.; Jewrajka, S.K. Degradable/cytocompatible and pH responsive amphiphilic conetwork gels based on agarose-graft copolymers and polycaprolactone. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2015, 3, 8548–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, A.K.S.; Nutan, B.; Raval, I.H.; Jewrajka, S.K. Self-Assembly of Partially Alkylated Dextran-graft-poly[(2-dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate] Copolymer Facilitating Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Drug Delivery and Improving Conetwork Hydrogel Properties. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutan, B.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Bhalani, D.V.; Jewrajka, S.K. Synthesis and tailoring the degradation of multi-responsive amphiphilic conetwork gels and hydrogels of poly (β-amino ester) and poly (amido amine). Polymer 2017, 111, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caló, E.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Biomedical applications of hydrogels: A review of patents and commercial products. European Polymer Journal 2015, 65, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, H.; Buksh, K.; Noreen, S.; Pervaiz, F.; Maqbool, I. Hydrogels as potential drug-delivery systems: network design and applications. Therapeutic Delivery 2021, 12, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K. Bioavailability Enhancement Techniques for Poorly Aqueous Soluble Drugs and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantha, S.; Pillai, S.; Khayambashi, P.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, O.; Pham, H.M.; Tran, S.D. Smart Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]