Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

15 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Approach

3. Results

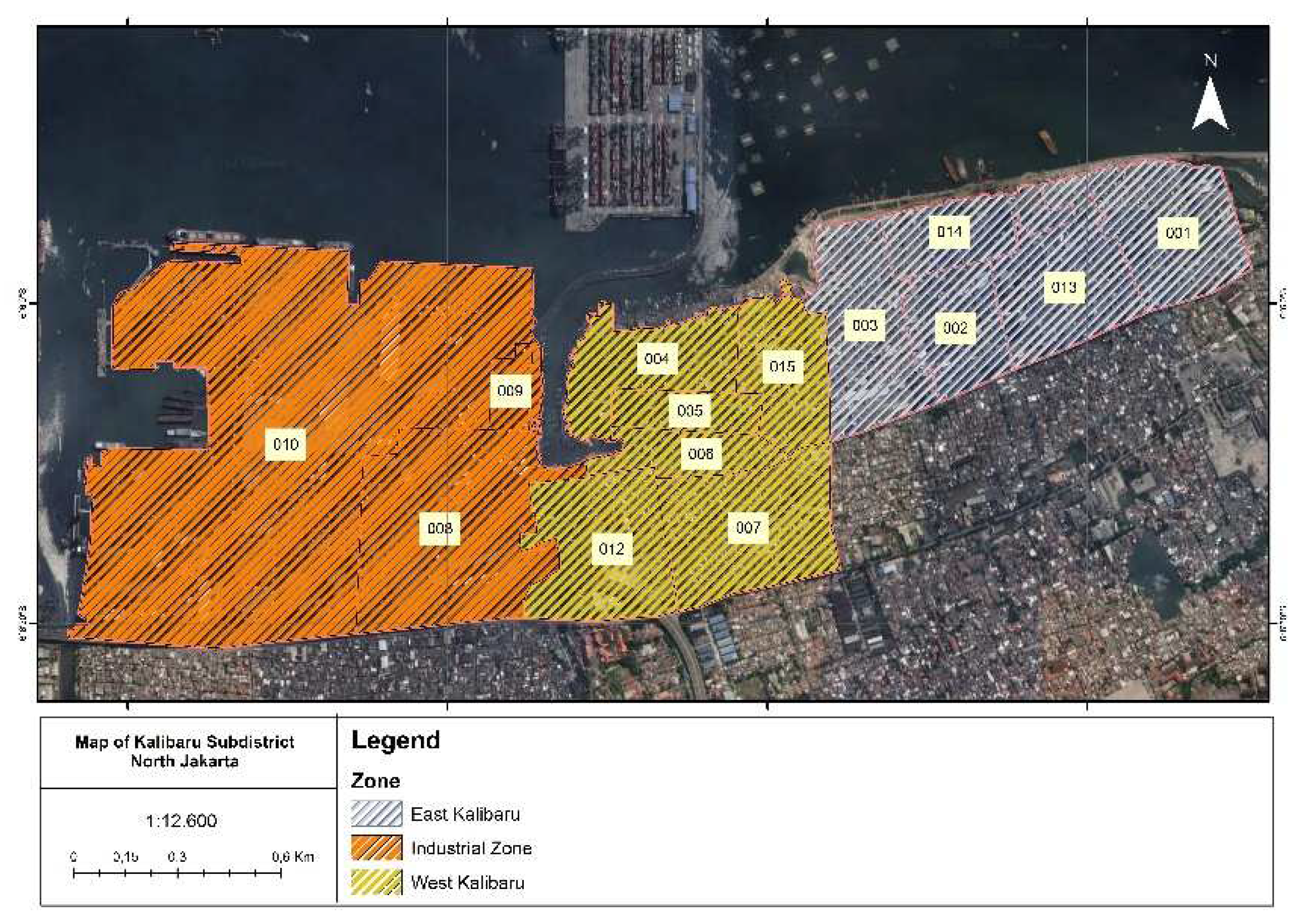

3.1. Geographic Boundaries

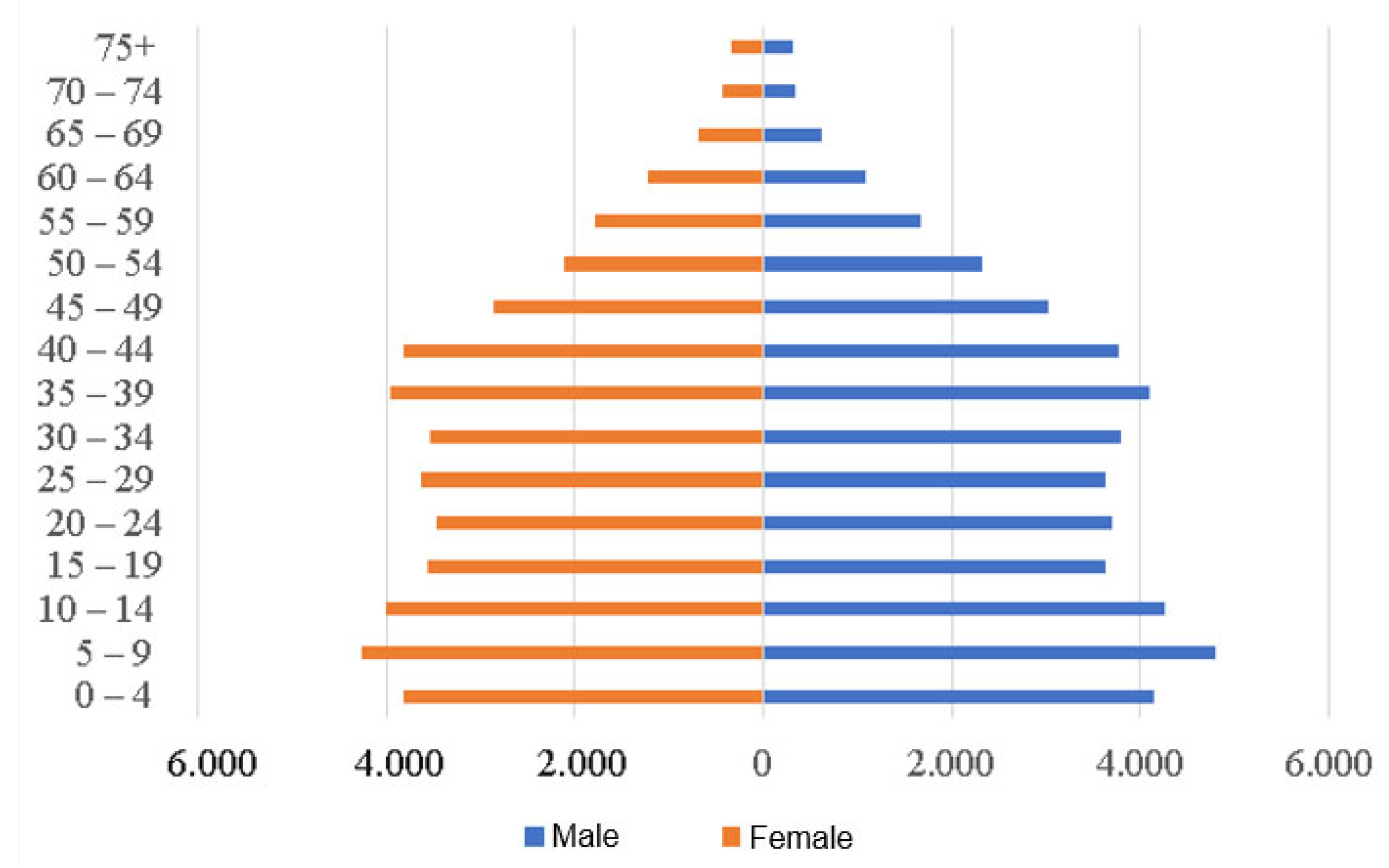

3.2. Demographic Character

| Level of education | Sex | Number of residents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Not/Not yet schooled |

2,960 | 2,724 | 5,684 |

| Not finished elementary school |

4,282 | 3,824 | 8,106 |

| Graduated from elementary school/equivalent | 7,706 | 10,067 | 17,773 |

| Middle school/Equivalent |

9,848 | 9,832 | 19,680 |

| High School/Equivalent |

12,257 | 9,395 | 21,652 |

| Diploma I/II |

38 | 62 | 100 |

| Academy/Diploma III |

234 | 314 | 548 |

| Diploma IV/ Undergraduate Degree | 593 | 461 | 1,054 |

| Graduate Degree |

17 | 12 | 29 |

| Postgraduate Degree |

2 | 2 | 4 |

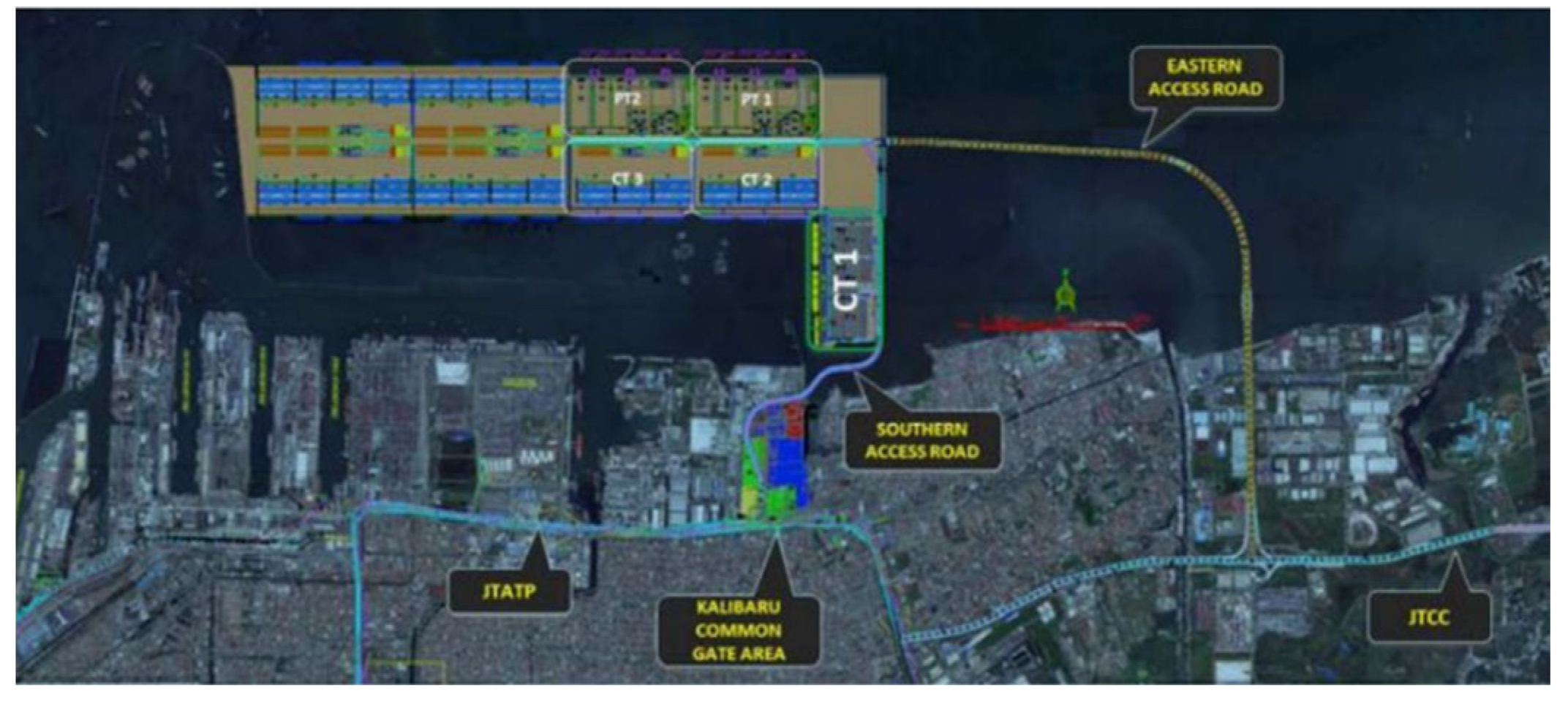

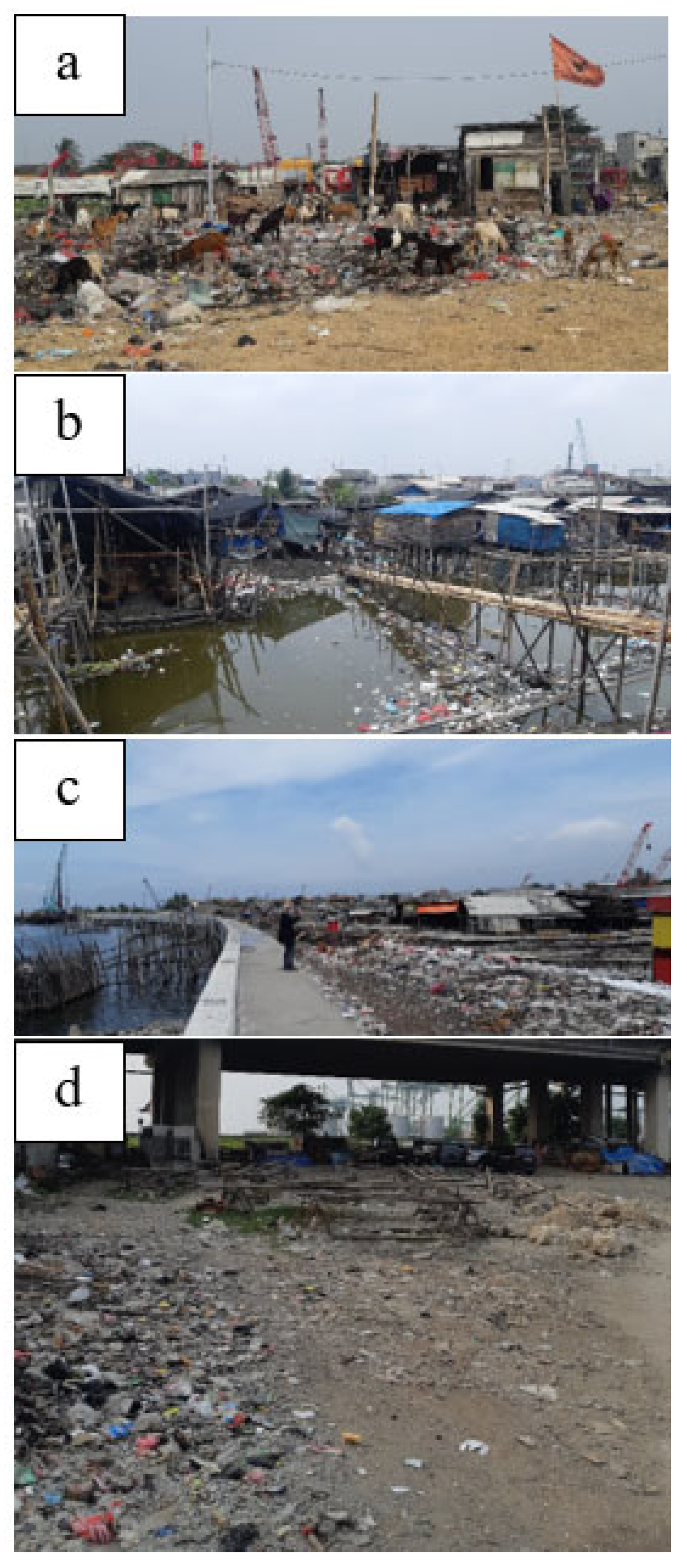

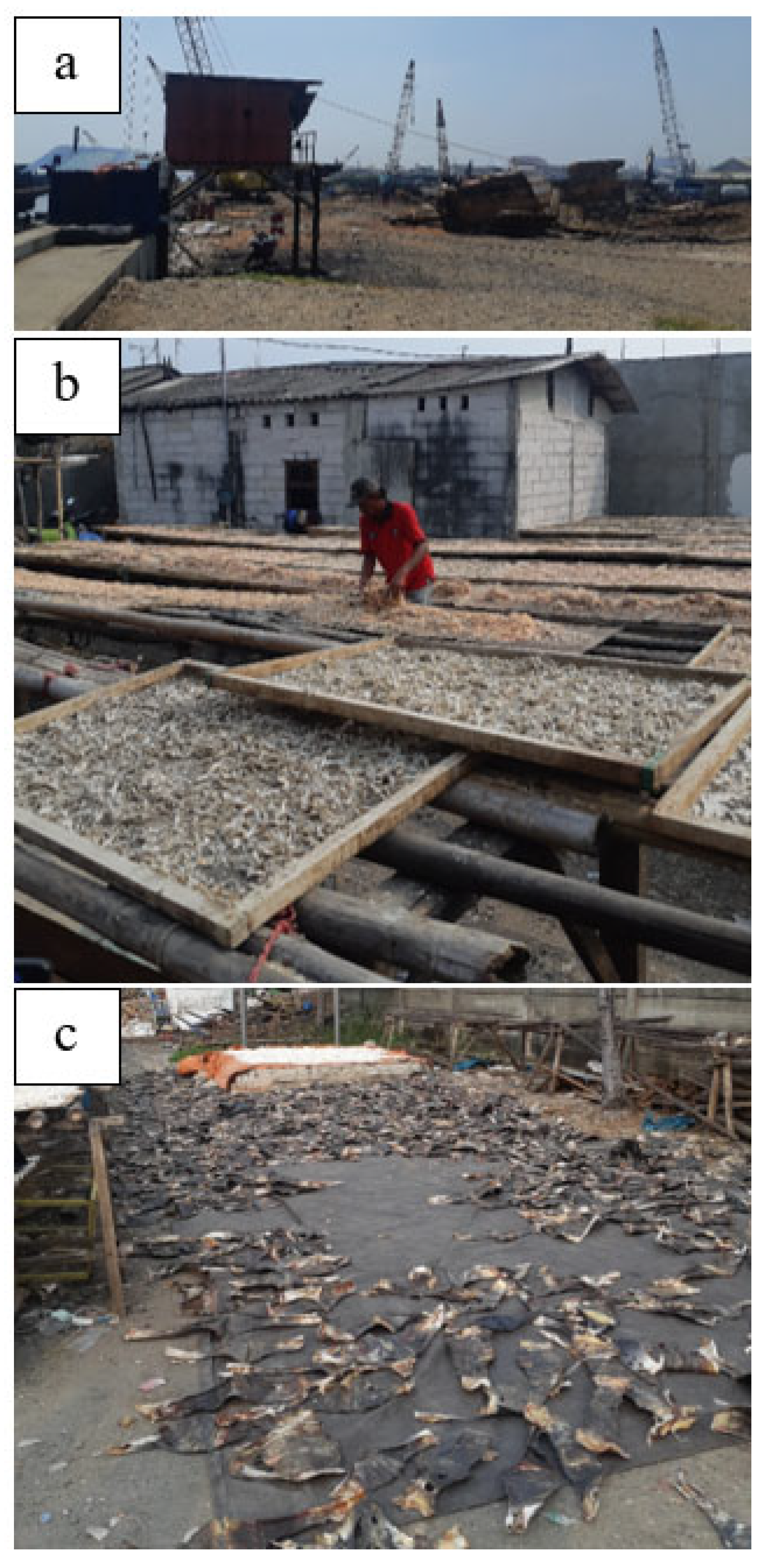

3.3. Development Conditions

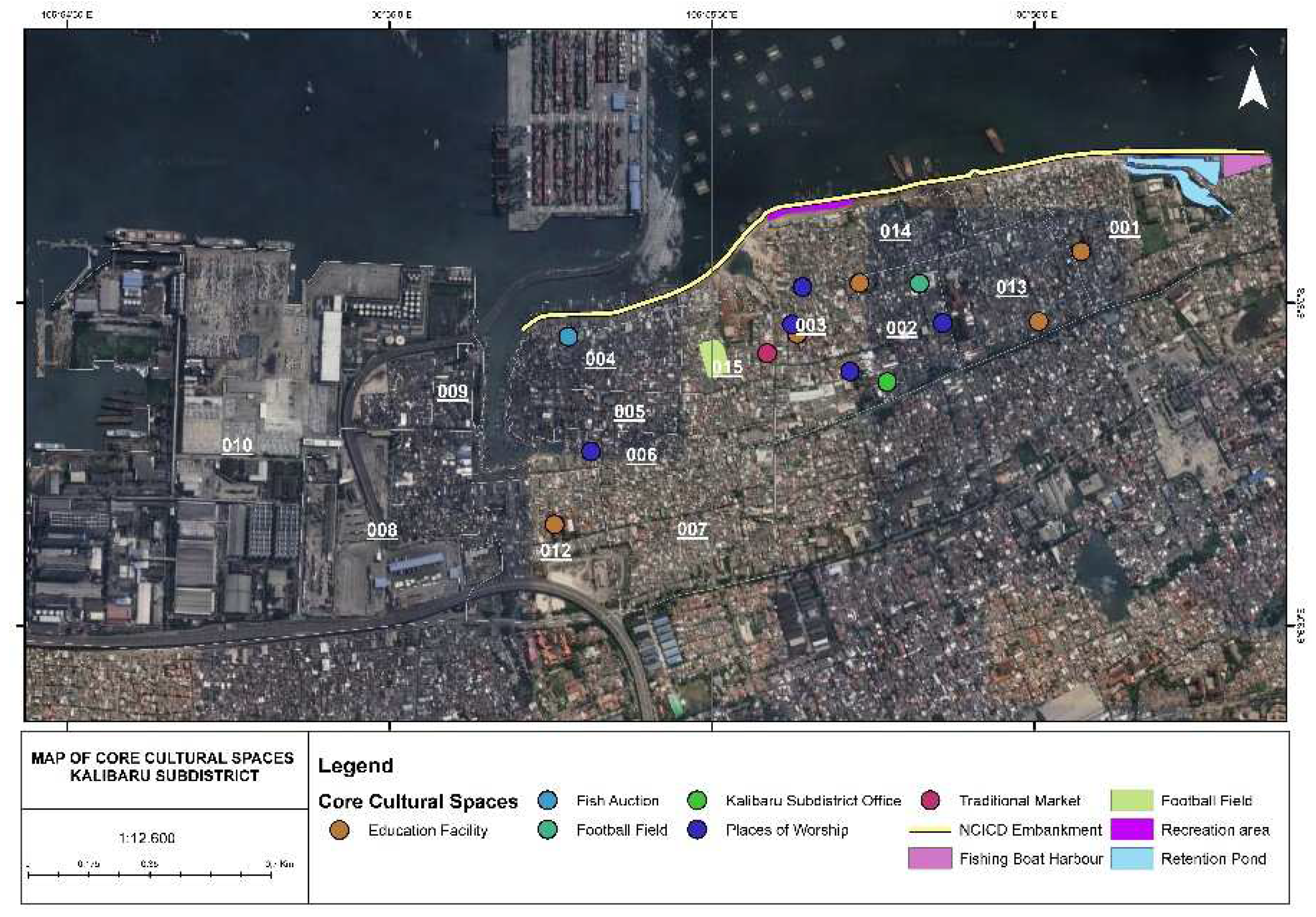

3.4. Core Cultural Spaces

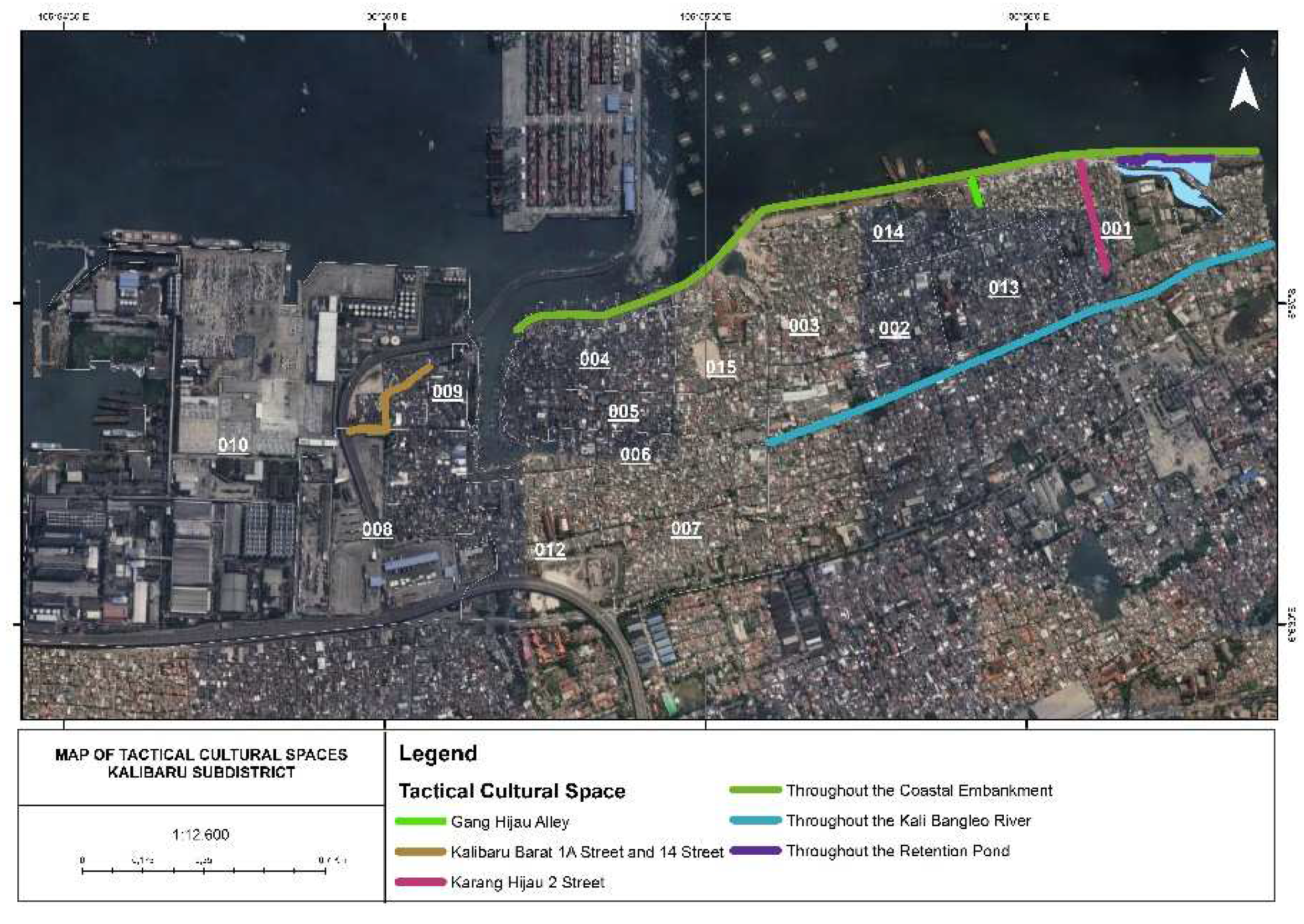

3.5. Tactical Cultural Spaces

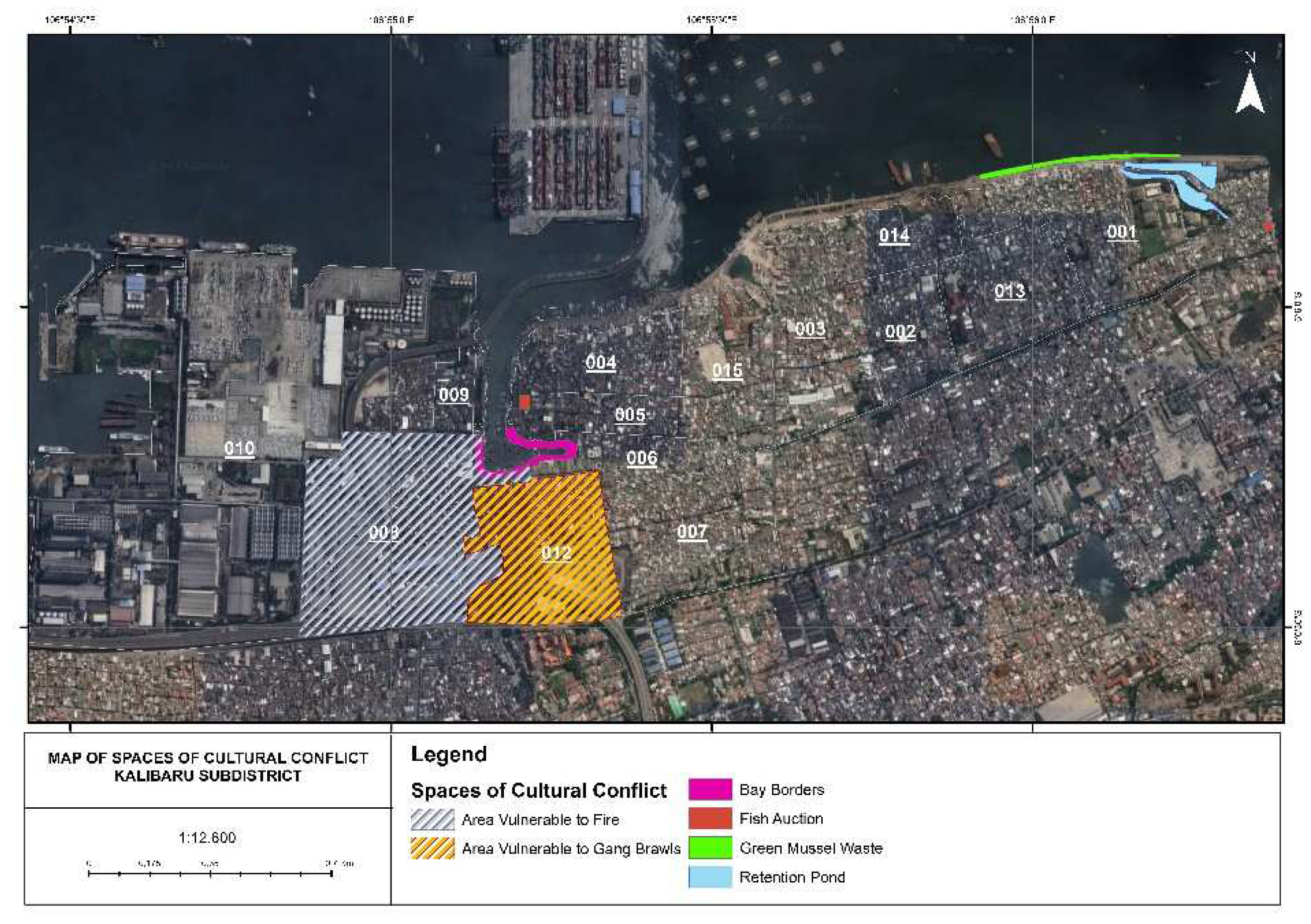

3.6. Cultural Spaces of Conflict

3.7. Specific Cultural Topics

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, A. K.; Sinha, R.; Koradia, D.; Patel, R.; Parmar, M.; Rohit, P.; Patel, H.; Patel, K.; Chand, V. S.; James, T. J.; Chandan, A.; Patel, M.; Prakash, T. N.; Vivekanandan, P. Mobilizing grassroots’ technological innovations and traditional knowledge, values and institutions: Articulating social and ethical capital. Futures 2003, 35, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, J. Understanding sustainable development; Routledge, 2018.

- Rogers, P.; Jalal, K.; Boyd, J. An introduction to sustainable development. In Earthscan; 2008.

- Ramos, T. B. Sustainability assessment: Exploring the frontiers and paradigms of indicator approaches. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, D. The role of indicator-based sustainability assessment in policy and the decision-making process: A review and outlook. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2017, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J. Cultural influences on implementing environmental impact assessment: Insights from Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 1998, 18, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Joas, M.; Sundback, S.; Theobald, K. Governing local sustainability. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2006, 49, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmana, D. The Change and Transformation of Indonesian Spatial Planning after Suharto’s New Order Regime: The Case of the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. International Planning Studies 2015, 20, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, C. Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development: An Action Planning Approach for Jakarta. Jurnal Perencanaan Wilayah Dan Kota 2014, 25, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, P.; Birnie, A. Is there a correct way of establishing sustainability indicators? The case of sustainability indicator development on the Island of Guernsey. Local Environment 2005, 10, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E. D. G.; Dougill, A. J.; Mabee, W. E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Re-thinking Sustainability Indicators: Local Perspectives of Urban Sustainability. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2013, 56, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllyviita, T.; Lähtinen, K.; Hujala, T.; Leskinen, L. A.; Sikanen, L.; Leskinen, P. Identifying and rating cultural sustainability indicators: A case study of wood-based bioenergy systems in eastern Finland. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2013, 16, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Degerman, E.; Teitelbaum, S.; Andersson, K.; Elbakidze, M.; Drotz, M. K. Social and cultural sustainability: Criteria, indicators, verifier variables for measurement and maps for visualization to support planning. Ambio 2013, 42, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, K.; Myllyviita, T. Cultural sustainability in reference to the global reporting initiative (GRI) guidelines. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2015, 5, 290–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Assessing cultural sustainability; United Cities and Local Governments, 2014.

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell, 1974.

- de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press, 1984.

- 20. Bappeda DKI Jakarta. Rencana Pembangunan Daerah 2023-2026; 2022.

- Sudaryono. Paradigma Lokalisme Dalam Perencanaan Spasial. Journal of Regional and City Planning 2006, 17, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Setiadi, H.; Yunus, H. S.; Purwanto, B. The metaphor of “center” in planning: Learning from the geopolitical order of swidden traditions in the land of sunda. Journal of Regional and City Planning 2017, 28, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybriwsky, R.; Ford, L. R. City profile Jakarta. Cities 2001, 18, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.; Masron, I. N. Jakarta: A city of cities. Cities, 2020; 106(June). [Google Scholar]

- Kusno, A. Runaway city: Jakarta Bay, the pioneer and the last frontier. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 2011, 12, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlambang, S.; Leitner, H.; Tjung, L. J.; Sheppard, E.; Anguelov, D. Jakarta’s great land transformation: Hybrid neoliberalisation and informality. Urban Studies 2019, 56, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudalah, D.; Firman, T. Beyond property: Industrial estates and post-suburban transformation in Jakarta Metropolitan Region. Cities 2012, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R. M.; Solecki, W. D. Consumption, inequity, and environmental justice: The making of new metropolitan landscapes in developing countries. Society and Natural Resources 2008, 21, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, A.; Spangenberg, J. H. A guide to community sustainability indicators. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2000, 20, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenthen, M. Environmental Hermeneutics and the Meaning of Nature 2017, May 2018, 1–15.

- Brennan-Horley, C.; Luckman, S.; Gibson, C.; Willoughby-Smith, J. Gis, ethnography, and cultural research: Putting maps back into ethnographic mapping. Information Society 2010, 26, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural Mapping: Intangible Values and Engaging with Communities with Some Reference to Asia. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 2013; 4, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Galehbakhtiari, S.; Hasangholi Pouryasouri, T. A hermeneutic phenomenological study of online community participation: Applications of fuzzy cognitive maps. Computers in Human Behavior 2015, 48, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage, 1992.

- Soja, E. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell, 1996.

- Soja, E. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Verso, 1989.

- Mumford, L. The Culture of Cities; Harvest Books, 1970.

| Letter | Male/ Female |

Age | Years of residence |

Identified ethnicity |

Field of work/ organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | 37 | 32 | Betawi |

Public facilities care/ Karang Taruna youth |

| B | M | 47 | 33 | Betawi- Indramayu |

Fisherman/ Kalibaru fishermen co-op |

| C | F | 42 | 42 | Sulawesi |

Housewife/ PKK women’s organization |

| D | M | 37 | 22 | Betawi- Indramayu |

Public facilities care/ Local mosque assembly |

| E | M | 36 | 36 | Betawi- Indramayu |

Fisherman/ Private social foundation |

| F | F | 51 | 26 | Makassar- Sulawesi |

Housewife/ PKK women’s organization |

| G | M | 37 | 37 | Bone- Sulawesi |

Karang Taruna youth |

| H | F | 49 | 39 | Bugis- Sulawesi |

Elementary schoolteacher/ PKK women’s organization |

| I | M | 36 | 36 | Indramayu |

Public facilities care/ Local mosque assembly |

| J | M | 28 | 28 | Betawi- Indramayu |

Shipping port worker/ Karang Taruna youth |

| RW | Number of RT |

Number of families |

Total population |

Area (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 15 | 2.766 | 8.784 | 14 |

| 02 | 13 | 1.382 | 4.311 | 8,9 |

| 03 | 17 | 2.813 | 8.660 | 14,8 |

| 04 | 14 | 2.171 | 7.076 | 11,3 |

| 05 | 13 | 1.536 | 4.765 | 4,9 |

| 06 | 12 | 1.838 | 5.695 | 6 |

| 07 | 15 | 4.109 | 12.595 | 17,3 |

| 08 | 11 | 2.092 | 6.025 | 28,4 |

| 09 | 6 | 524 | 1.604 | 2,5 |

| 10 | 9 | 1.116 | 3.441 | 97,7 |

| 12 | 14 | 2.660 | 7.729 | 15,6 |

| 13 | 13 | 2.466 | 7.863 | 14,1 |

| 14 | 8 | 1.520 | 4.841 | 8,4 |

| 15 | 12 | 1.639 | 5.233 | 9,9 |

| Total | 88.622 | 253,9 | ||

| Cluster | RW | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Zone | 08 | The Industrial Zone is marked by the presence of companies, mostly import-export, with offices or warehouses and business activities on site, including PT AIRIN, PT Bogasari, PT Indofood Sukses Makmur, PT Indonesia Vehicle Terminal, PT Pelabuhan Indonesia (Pelindo), and PT Pelayaran Bahtera Adhiguna. Pelindo, in particular, is the state-owned company managing the shipping container terminal in this area, namely New Priok Container Terminal One (NPCT1). Residential areas in this area are bordered by company fences and walls on the west, north, and south, and are bounded by Jakarta Bay on the east. The community organization with a significant presence in this area is the Kalibaru Port Temporary Workers Cooperative (TKBM), with most members also joining the Karang Taruna youth organization of Kalibaru Subdistrict. |

| 09 | ||

| 10 | ||

| West Kalibaru | 04 | West Kalibaru area is marked by Jalan Raya Cilincing road in the south, Jakarta Bay and the Jakarta Outer Ring Road tollroad in the west, Jakarta Bay in the north, and Jalan Cilincing Baru road in the east. Jalan Cilincing Baru road is the main marker between the West Kalibaru and East Kalibaru areas. Other markers are the fish auction (TPI) at West Kalibaru in RW 04 and TPI at East Kalibaru in RW 01. The community organization with a significant presence in the region is the West Kalibaru Fishermen Association. |

| 05 | ||

| 06 | ||

| 07 | ||

| 12 | ||

| 15 | ||

| East Kalibaru | 01 | East Kalibaru area is marked by Jalan Raya Cilincing road in the south, Jalan Cilincing Baru road in the west, Jakarta Bay in the north, and Jalan Cilincing Krematorium road in the east. This area includes most of the embankment construction on the border of Jakarta Bay and Kalibaru Subdistrict. The community organization with a significant presence in the region is the East Kalibaru Fishermen Association. This area is adjacent to the Cilincing Subdistrict which has its own fish auction (TPI) and fishermen association at the mouth of Kali Rawa Malang river. |

| 02 | ||

| 03 | ||

| 13 | ||

| 14 |

| Land use | Area (ha) |

|---|---|

| Shipyard | 0,74 |

| Open warehouse | 12,11 |

| Closed warehouse | 1,83 |

| Other green space | 0,52 |

| Industry | 2,60 |

| Small industry | 1,29 |

| Playgroup/Kindergarten | 0,01 |

| Clinic | 0,02 |

| Pool | 0,31 |

| Empty land | 3,21 |

| Sports field | 0,89 |

| Financial institution | 0,05 |

| Mosque | 0,55 |

| Minimarket | 0,07 |

| Musala/Prayer room | 0,07 |

| Motor vehicle parking | 0,83 |

| Truck and container parking | 5,45 |

| Central market | 0,41 |

| Traditional market | 1,61 |

| Motor vehicle washing | 0,09 |

| Basic education | 1,16 |

| Upper secondary education | 0,67 |

| Junior secondary education | 0,01 |

| Regional government office | 0,36 |

| National government office | 0,11 |

| Shop | 4,55 |

| Pesantren/Islamic boarding school | 0,06 |

| Pura/Temple | 1,07 |

| Public health centre | 0,12 |

| Small house | 14,89 |

| Boarding house | 0,38 |

| Very small house | 38,36 |

| Medium house | 0,01 |

| Environmental playground | 0,01 |

| Fish auction | 0,04 |

| Space | Description |

|---|---|

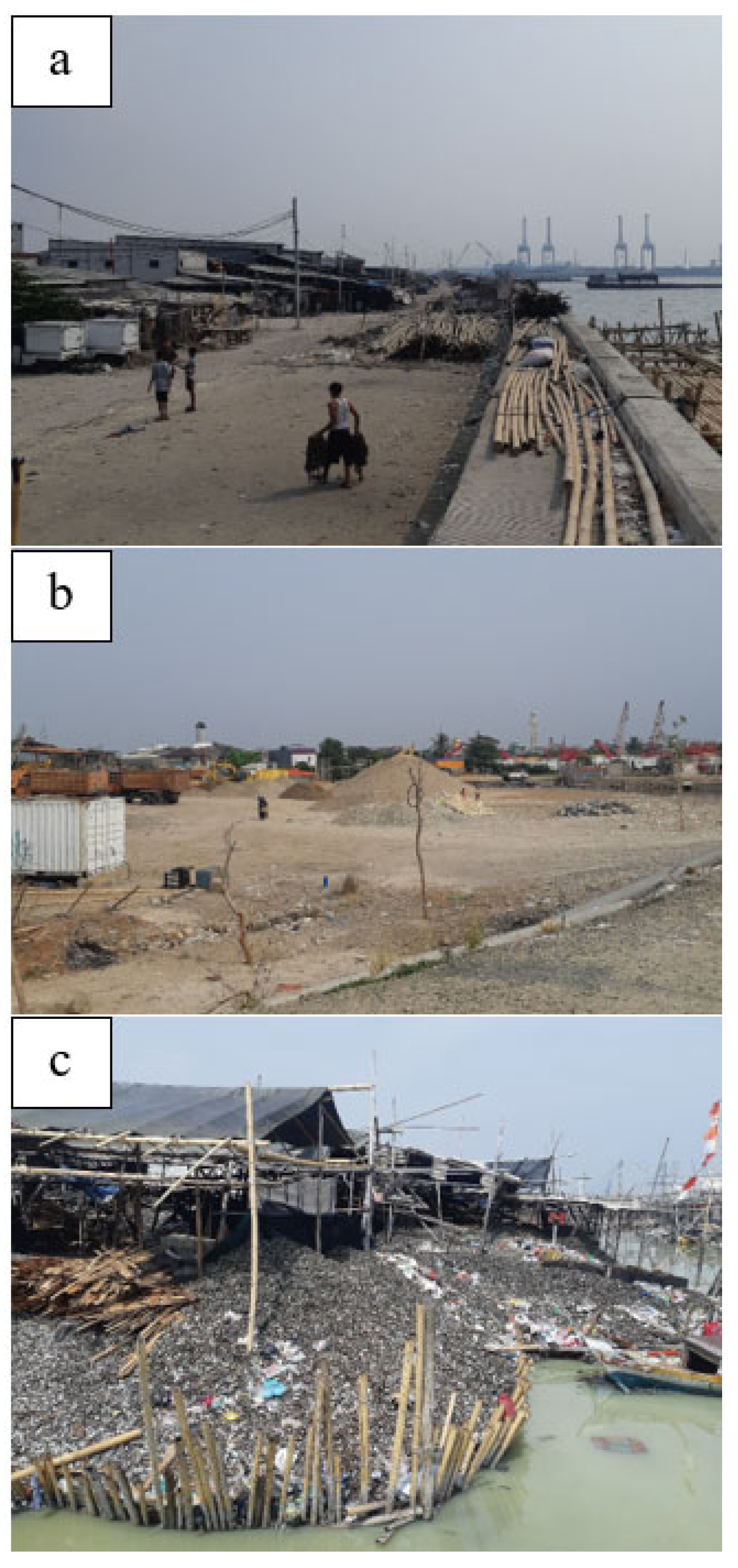

| Phase A NCICD embankment in Kalibaru Subdistrict along the coast of RW 01, RW 03, RW 04, RW 06, RW 13, RW 14, and RW 15 | The construction of embankments in the last 5 years has had a significant impact on people's daily lives. Fishing boat harbours that were previously located along the coast are now concentrated in RW 01 and RW 04. The fishing community makes bamboo structures as boat moorings, ladders, and bridges between the sea, embankments, and land. |

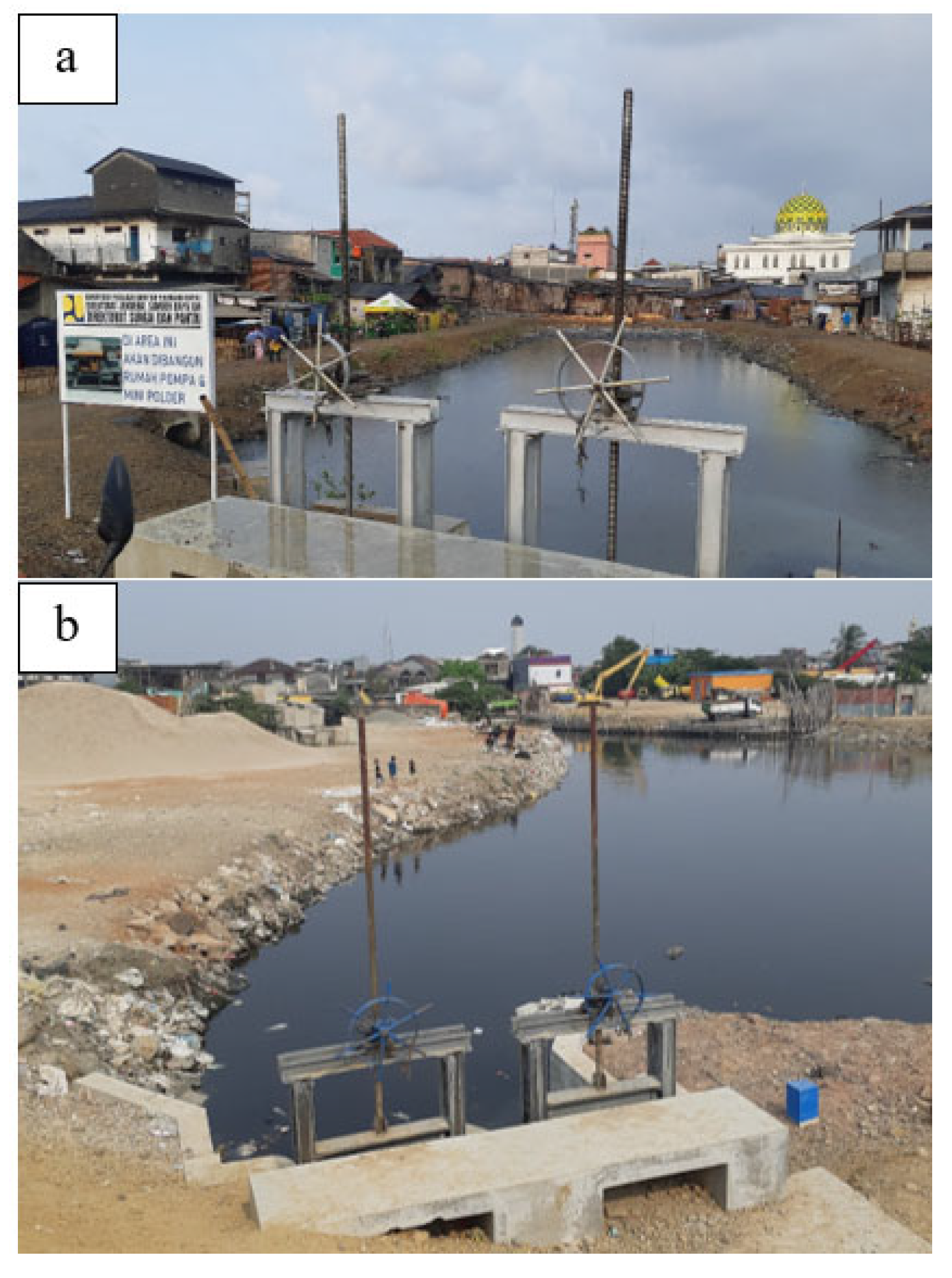

| Fishing boat harbour, retention pond, and pump house in RW 01 | The fishing boat port is planned to be concentrated only in RW 01 along with the next levee and container terminal construction phase. The pump house has been present in the last 2 years and has become a place of interest for the community in an effort to prevent flooding. |

| East Kalibaru Fishermen's Cooperative in RW 01 | The East Kalibaru Fishermen's Cooperative is one of the main stakeholders in resource management at the site including facilitating support for fishermen and waste treatment. |

| Fish Auction (TPI) in RW 01 and RW 04 | The fish auction in RW 04 is planned to be moved and concentrated only in RW 01 along with the relocation of the fishing boat harbours. |

| Kalibaru Subdistrict Office in RW 02 | The Subdistrict Office has spaces that are routinely used by the public for various social, cultural, and religious activities. |

| Plaza Kalibaru in RW 04 and RW 06 | Plaza Kalibaru was built in 2022 as a recreational space with parks, sports fields, and a jogging track along the embankment. It used to be the mooring centre for fishing boats in West Kalibaru and dirtied with piles of waste. Now, residents actively use it for activities such as children's playgrounds, gymnastics, and food stalls hawking. A specific section is planned to be built as a place for entertainment that is child-friendly and can function as an educational facility. The area around the plaza received assistance from the Ministry of Social Affairs in 2022 and facilities have been built to convert salt water into fresh water. |

| Wisata Kalibaru (WiKa) in RW 03 | WiKA was built in 2022 in East Kalibaru as a recreational space with the same facilities as Plaza Kalibaru. In the past it was part of the nearby sand barn and ship splitting area. |

| Football field in RW 15 | Since 2007, the football field in RW 15 has become the main space for community sports activities. The Karang Taruna youth organization regularly holds competitions on site, including an annual futsal tournament. |

| Futsal field in RW 02 | A futsal field nearby the RW office which has become an alternative sports location. |

| The main traditional markets in Kalibaru Subdistrict include the Jalan Baru Market in RW 02 and RW 03, as well as the Mencos Market on the border of RW 05 and RW 06 |

The traditional market is often mentioned by informants as their daily destination and has existed since they were born. |

| Schools, among others: • MI Miftahul Hikmah (Islamic school) in RW 05; • Elementary, Middle, and High School Complex in RW 12; • Public Elementary in RW 02, 03, 07, 13, 14 and 15; • Private Elementary Pantai Indah Kalibaru; • Private Elementary Dewi Sartika; • Muhammadiyah Islamic Boarding School in RW 04; • Learning Center in RW 08. |

Schools are a prevalent daily destination for informants when dropping off and picking up children. Each RW also has a playgroup centre near their respective offices, except for RW 01, 03, 05, 06, 09, and 14. |

| Mosques and prayer rooms, including: • Al Hidayah Mosque in RW 04; • Baitus Syukur Mosque in RW 05; • Baitul Mukminin Mosque in RW 06; • Al Mubasirin Mosque in RW 07; • Darussalam Lama Mosque in RW 10; • Musala/Prayer room in RW 13; • Musala At Taubah in RW 15. |

Mosques and prayer rooms are daily destination for most informants, especially at nighttime, with multiple social and religious activities including Koran recitations, lectures, and mutual cooperation to clean RW public premises. |

| Temporary landfill in RW 08 and Waste Bank in RW 06 | The PKK women's organization is active in separating and recycling waste in RW 06 and RW 08. The landfill in RW 08 was renovated in 2021. Piles of waste can also be found in RW 15 and RW 04. The highest amount of waste comes from RW 07 as the RW with the largest population. Most of the fishery waste, including shells, comes from RW 01 and RW 13, which are intensive fishery activity areas. |

| Temporary port workers (TKBM) cooperative office in RW 08 | Nearly 600 Kalibaru youth are temporary port workers who are required to fill in attendance at the TKBM office before leaving with the group to the container terminal. Access to the terminal is closed for TKBM except by shuttle bus. Most of the TKBM are also members of Karang Taruna youth organization. |

| Under the toll road at RW 09 and RW 12 | The space under the toll road has been initiated by residents to become a public space. There is a ball field, pigeon racing community area, and a fishing area. Music and martial arts events are also often held. |

| Space | Description |

|---|---|

| Along the coastal embankment | Even though the fishing harbours has been centralized in RW 01, the fishing community still uses the spaces under the embankment as a place to store boats (for boat repair and preparation activities) so they don't pile up in the harbour area. The fishermen store materials such as bamboo and rope along the embankment. As a result of deliberations with the developers, several points under the embankment have been agreed to be built for ship repair and material storage. |

| Around the RW 01 retention pond | The concentration of various activities has made the area lively. Residents began to aspire to build recreational and even tourism facilities, as well as facilities to ensure safety at the site. There are also hawkers who sell their wares around the location. |

| Around the retention ponds in RW 03/RW 15 and RW 04/RW 06 (WiKa and Plaza Kalibaru area) | With the recent bustle of activity, many residents peddle on the streets around the location. In the month of Ramadan, residents hold a culinary bazaar. Vacant land in the RW 15 and RW 04 areas has begun to be discussed as a park or street market area. |

| Throughout the Bangleo River | Residents use the Bangleo River for daily activities such as recreation, peddling, and fishing. Notably, the river segment in Gang Macan/Macan Alley in RW 12 is one of the points of blockage and accumulation of garbage in the river. |

| Along Jalan Kalibaru Barat 1A street and Jalan Kalibaru Barat 14 street in RW 10 | Along the way, the alley is a place where many children play until nighttime, as well as many street vendors. The lack of public space in RW 09 and RW 10 areas due to its location in between industrial areas has made residents maximize the use of existing space. |

| Along Jalan Karang Hijau 2 street in RW 01 | Several alleyways in the Kalibaru Subdistrict are used to hold “almsgiving for the earth” events which are generally held in conjunction with the Independence Day (17 August) festivities. Residents bring prepared food from their homes, gather in alleys, spread carpets, and pray together. |

| Gang Hijau alley in RW 13 and Gang Semprotan alley in RW 02 | Several alleyways were initiated by the PKK women’s organization as locations for “green alleys” with herbal plants that are jointly managed by residents. |

| Space | Description |

|---|---|

| Fish auction in RW 01 and RW 04 | The fish auction in RW 04 will be merged with the fish auction in RW 01 due to development. This has the potential to trigger conflict between the developer and the fishing community in East Kalibaru and West Kalibaru. |

| Retention pond in RW 01 | The retention pool area is dark at night because there is no lighting and is now prone to local gang brawls. |

| Around the border of the bay at RW 06, RW 08, and RW 12 | This area is still prone to inundation and flooding of up to 50 cm during heavy rains. |

| Stockpiling of materials and waste along the embankments of RW 01 and RW 13 | Green mussel waste is mostly found in RW 01 and RW 13, considering the large number of fishermen and their production activities there. Materials like bamboo and rope also cover the road. |

| Overspill of landfill trash around RW 08, RW 07, and RW 15 | Before the construction of Plaza Kalibaru, there were piles of trash around RW 08, RW 06, and RW 04. RW 07 has the highest population density in Kalibaru Subdistrict and the highest amount of waste. Piles of garbage occur in RW 15 due to the absence of landfills and the length of time for transportation (every 2 days). |

| Fire in RW 08 area | RW 08 is vulnerable to fires due to a port and wood storage centre nearby. A big fire happened in 2009 between RW 08 and RW 10 due to negligence of a polymer factory near the site. |

| Gang brawls in the RW 03 and RW 12 areas | RW 03 as one of the RWs with the highest population density, is prone to brawls on Jalan Baru street near the market and the Subdistrict office. RW 12 has the lowest level of participation in Karang Taruna youth organizations. |

| PT Pelindo's land development in the RW 10 area | Most of the residential land in RW 10 belongs to PT Pelindo company and is in preparation for demolition. Companies and developers try to establish good relations with residents through intensive CSR activities in the RW 08, RW 09, and RW 10 areas. |

| Shifts in fishermen's economic activities and environmental pollution along the embankment coast | All fishermen informants worry about their livelihoods and sea conditions with the NPCT2, NPCT3, and NPEA industrial development plans. Prior to 2016, it was known that the number of large vessels passing through fishing routes was still not many. Fishermen realize that most of the pollution in the sea comes from company factories and large ships. |

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Sea ceremonies | The sea ceremony (pesta laut) is a fishermen tradition that is carried out at least once a year. In practice, West Kalibaru fishermen and East Kalibaru fishermen formed a committee for the preparation of the event together with the Cilincing fishermen group. The location of the sea ceremony is centred at the mouth of Kali Rawa Malang river, nearby the Cilincing fish auction. Although the sea ceremony is a tradition characteristic of fishermen, all informants are of the opinion that the aspect of the tradition belongs to the parents (previous fishermen's generation) and the current generation of fishermen just join in for the festivities. There are those who also argue that sea ceremonies should not be held if current conditions for fishermen are difficult (e.g., lack of funds or a pandemic situation). The sea ceremony is open to the public and has become a tourist spot for city dwellers who want to know more about fishing culture. |

| Almsgiving for the earth | Alms for the earth (sedekah bumi) is usually done in conjunction with the celebration of Independence Day on August 17th. Residents usually gather with their neighbours in one RW, cook food, and hold prayers together in the alleyways. |

| Local system of shipping and harbouring | Management of ships, organizing departures to go to sea, and the data collection system is managed by fishermen groups. Ship registration and sailing and anchoring permits are managed by the harbourmaster (syahbandar). The Harbourmaster and Port Authority Office (KSOP) issues a Small Pass card for fishermen as a document in the form of a certificate of ownership and nationality of the ship and can be used as collateral for business credit or insurance. |

| Ethnic-based community associations | Majority of informants are the second generation of parents who migrated to Jakarta from West Java (Indramayu) or South Sulawesi (Bugis-Bone-Makassar). Some of their parents married Betawi people and now identify themselves as Betawi-Indramayu or Betawi-Sulawesi. There are ethnic-based community organizations or harmony such as the Bone Community Family Harmony (KKMB), the South Sulawesi Family Association (PKSS), the Betawi Rempug Forum (FBR), and ethnic-based arisan gathering groups or arts activities such as Betawi lenong and martial arts centres. All informants know the existence of the associations but are not actively involved in it. |

| Religious social activities | Majority of informants are active in social-religious activities at the mosque or prayer room near their residence. The subdistrict has a system for residents working together to manage the cleanliness of mosques. Every Friday, the subdistrict staff organizes cleaning activities at different RW mosques. There are 57 religious assemblies in the subdistrict with regular Koran recitation activities. The majority of large or subdistrict level activities are held at the subdistrict office. |

| Social activities supported by companies/foundations/outside agencies | Community groups often submit proposals for financial support to various large companies with offices in Kalibaru Subdistrict. These companies channel significant CSR due to the environmental impact of their business activities. Several social foundations are also active in assisting the social activities of Kalibaru residents, including the HOPE Indonesia Foundation, the Mitayani Foundation, and the Polar Social House. Other activities are supported by various political parties and government agencies. Educational institutions have also carried out various assistance or community service activities, such as the Jakarta Health Polytechnic, State Islamic University, and the University of Indonesia. |

| System of temporary port workers | Since 2017, the Kalibaru Subdistrict has around 600 youth working as Temporary Port Workers (TKBM) at container terminals. |

| Activities of the PKK women’s organization | As a social organization that aims to empower women, the Family Welfare Empowerment Group (PKK) in Kalibaru Subdistrict is very active in social activities in its area. The PKK is divided into several working groups: 1. Working Group 1 fosters religious activities, mutual cooperation, data collection, and counselling, 2. Working Group 2 fosters economic activities such as the Family Income Increase and Business (UP2K) program, cooperatives, and educational activities such as the establishment of playgroups in every RW, 3. Working Group 3 fosters food security program activities such as selling used cooking oil and channelling the proceeds for alms, 4. Working Group 4 fosters health and environmental sustainability activities such as Hatinya PKK (greening areas with food and medicinal plants) and programs with health centres such as reducing stunting rates. There are 26 Toddler health centres and 14 Elderly and Integrated health centres in the Subdistrict. The various PKK programs above have won awards and appreciation from the North Jakarta City government. |

| Activities of the Karang Taruna youth organization | The Karang Taruna youth organization in Kalibaru Subdistrict is also very active in holding social activities in the area. In the field of sports, Karang Taruna has an annual soccer tournament agenda which has been managed since 2005 and is held on the RW 15 football field. In the creative sector, Karang Taruna also has regular programs such as the Creative Sea Children's Group (KOPLAK) with handicraft exhibitions and magazines from young journalists. This group is also actively developing packaging products for MSMEs such as green mussel crackers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).