1. Introduction

With the rapid development in the field of deep learning, significant progress has been made in target detection. Many advanced detectors based on CNN and transformer [

28] have been proposed to drive the smooth development of target detection techniques. Among these detectors, FPN [

10] stands out as it can enhance detector performance in a straightforward and effective manner by propagating semantic information to establish a CNN feature hierarchy IRecently, transformer technology has gained increasing attention, leading to the development of several detectors [

21,

22,

27] that rely on transformers. These detectors have shown promising results compared to conventional CNN-based approaches. However, both the FPN structure and transformer-based detectors have some design flaws, which are described as follows:

Loss of texture information in FPNs. The classical FPN-based networks have greatly enhanced the performance of detection networks through multi-scale feature learning. Subsequent FPN structures [

11,

12,

13,

29], proposed based on this concept, have employed similar architectures to FPN. Multiple studies have shown that low-level features play a crucial role in recognizing larger instances. The abundant texture information present in the low-level feature map aids in target localization and precise framing. However, during the downsampling process, all features extracted from the backbone network inevitably suffer from a significant loss of texture information. This loss can potentially impact the accuracy of the location information acquired by the detection network.

Confounding effect of cross-level feature fusion. During the cross-level feature fusion process, overlaying the upsampled feature map onto the original feature map leads to feature discontinuity and confuses the fused features. This phenomenon is referred to as the feature confusion effect [

10]. The confounding effect becomes more pronounced as more feature maps are superimposed.

The limitation of interaction between windows in Shifted Window based Self-Attention.Utilizing a global attention mechanism on the feature map in a transformer-based detection network incurs a substantial computational burden. However, employing Shifted Window based Self-Attention significantly alleviates the computational complexity of the transformer. Nevertheless, the interaction between each window in the Shifted Window based Self-Attention is limited to its neighboring windows. This constraint imposes limitations and could potentially impair the model’s ability to perceive larger objects.

Our proposed solution, TIG-DETR, addresses these shortcomings by incorporating a backbone network, a new FPN (TE-FPN) network, and a DETR-based detector.

Our contributions:

1. To address this, we propose constructing a bottom-up path within the backbone using the low-level feature map. Unlike the downsampling approach used in the backbone, our path aims to preserve maximum texture information in the feature map and integrates it with the features at the corresponding level in the top-down path of the FPN. As a result, this path encompasses both rich semantic and texture information. It is worth noting that a similar bottom-up path has been explored in prior works [

11,

25,

26]. However, the downsampling path implemented through convolution still leads to significant loss of texture information.

2. We introduced a novel attention module called ’Feature-wise Attention’ to address the feature fusion confounding effect in FPNs. This lightweight attention module is applied after the standard attention module to enhance the final features obtained from the SRS [

12] feature fusion module.

3. To reduce the computational complexity of DETR, we replaced the multi-headed self-attention module with Shifted Window based Self-Attention [

26]. Additionally, we incorporated feature maps from different stages of the backbone network to enhance the final feature map with texture information. The image undergoes segmentation and fusion after a multi-headed attention module, and is then restored to its original size. This approach enhances the texture information of the image and enables the model to perceive instances in the image prior to performing more detailed self-attention. It facilitates information interaction between each window and improves the model’s ability to perceive large objects.

2. Related Work

FPN. Before the introduction of FPN, various approaches for feature processing existed, including featurized image pyramids, single feature maps, and Pyramidal feature hierarchy. SSD [

30] utilized Pyramidal feature hierarchy, specifically focusing on hierarchical feature prediction goals, to enable different level features to learn the same semantic information. FPN [

10] proposes a method for fusing features of different resolutions by element-wise addition of the feature map from each resolution with the up-sampled low-resolution feature map. This enhancement improves the features at different levels, and subsequent models have built upon the FPN foundation. PANet [

11] introduced a bottom-up path enhancement to shorten the information path by utilizing the precise localization signal stored in low-level features, thereby improving the performance of the feature pyramid architecture. EfficientDet borrowed the TopDown-BottomUp concept from PANet and incorporated residual structures in each block to reduce optimization difficulties; Furthermore, the authors recognize that features from different layers possess varying semantic information. Directly summing these features can lead to sub-optimal problems. To address this, the authors introduce a learnable parameter in front of each layer of features to automatically determine their weights. Aug-FPN [

12] proposes Soft ROI Selection, which involves pooling ROI features from different levels and fusing them to enhance the performance of the feature pyramid architecture. To mitigate the loss of texture information in high-level feature maps, Aug-FPN incorporates a residual enhancement branch specifically designed to enhance the texture information of these high-level feature maps. In CE-FPN [

13], sub-pixel enhancement and attention-guided modules are employed in FPN to fully leverage the rich channel information of each level feature map, while minimizing the loss of channel information during the downscaling process.

Target detector. Traditional image target detection can be categorized into two main types: two-stage detectors, with Faster R-CNN [

8] being the most representative example, and one-stage detectors such as YOLO [

9], YOLO9000 [

3] and YOLOV3 [

20]. r-CNN [

44] demonstrated for the first time the significant improvement in target detection performance by using CNN on the PASCAL VOC dataset [

4] compared to HOG-like feature-based systems. Fast R-CNN [

1], proposed subsequently, overcomes the time-consuming aspect of R-CNN’s SVMs [

49] classification by employing ConvNet forward propagation for each region without redundant computation. Fast R-CNN [

1]extracts features from the entire input image and passes them through the ROI pooling layer to obtain fixed-size features for subsequent classification and bounding box regression in the fully connected layer. Instead of extracting features for each region separately, Fast R-CNN extracts features once from the entire image, reducing both the processing time and the storage space required for a large number of features. Fast R-CNN [

1] adopts selective search to propose RoIs, but this approach is slower and has the same running time as the detection network. In contrast, Faster R-CNN [

8] introduces a new RPN (region proposal network) that is composed entirely of convolutional networks and efficiently predicts region proposals. The RPN shares the same set of common convolutional layers with the detection network, and the fully convolutional Mask R-CNN [

15] optimizes the model by integrating low-level and high-level features to enhance the classification task. YOLO [

9] pioneered one-stage target detection, and subsequent one-stage detectors have built upon its improvements. Generally, two-stage detectors achieve higher localization and target detection accuracy, while one-stage detectors offer faster inference speed. However, both types of detectors are influenced by post-processing steps like compressing redundant prediction results, anchor frame design, and heuristics for assigning target frames to anchor frames [

17]. In contrast, DETR [

22] achieves an end-to-end target detector by directly predicting without relying on intermediate methods.

Transformer. Transformer was initially introduced as a Seq2Seq [

16] model designed for machine translation. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that a pre-trained Transformer-based model (PTM) [

35] can achieve state-of-the-art performance on various tasks. Consequently, the Transformer has emerged as the preferred architecture for NLP tasks. Besides the NLP domain, the Transformer has gained significant adoption in areas such as computer vision, audio processing, etc. [

36]. The Non-local Network [

46] was the first to employ the self-attentive mechanism in the field of computer vision, achieving successful target detection. Several frameworks have been proposed in recent years [

6,

31,

32]to enhance the Transformer and optimize it from various perspectives. Visual transformers [

50] incorporate the Transformer into a CNN, enhancing the CNN network by allocating semantic information of the input image to different channels and closely correlating them through encoder blocks (referred to as VT blocks). VT blocks are employed as an alternative to partial convolution to improve the semantic modeling capacity of CNN networks. SWIN-T [

6]introduced Shifted Window based Self-Attention, significantly reducing the computational complexity of the transformer when processing images. Funnel Transformer [

42] employs a funnel-like encoder architecture that incorporates pooling along the sequence dimension to progressively decrease the length of the hidden sequence and then employs upsampling for reconstruction, effectively reducing FLOP and memory consumption. When employing the transformer in the computer vision (CV) domain, the feature space resolution is constrained, and the network encounters challenges in convergence during training. To address these issues, Zhu et al. [

20] introduced Deformable DETR, which accelerates model convergence by directing the attention module to concentrate on a subset of key sampling points surrounding the reference.

Attention mechanism. Attention plays a crucial role in human perception of external information, as humans selectively concentrate on the most salient parts when processing information in a scene to enhance the capture of relevant information [

38]. RAM [

47] integrates deep neural networks with an attention mechanism, enabling end-to-end updating of the entire network by iteratively predicting significant regions. This marks the first implementation of an attention mechanism in CNN networks. Numerous subsequent works have adopted comparable attention strategies. STN [

48] predicts the spatial transformation by incorporating a sub-network that identifies significant regions in the input. SE-Net [

8] introduces a compact module that enhances inter-channel relationships by utilizing global average pooling to compute attention across channels. GSoP-Net [

45]addresses the limitation of using global average pooling alone in SENet for collecting contextual information, which restricts the modeling capacity of the attention mechanism. To overcome this, GSoP-Net proposes the global second-order pooling (GSoP) block to capture higher-order statistics while incorporating global contextual information. CBAM [

9] incorporates global maximum pooling in addition to global average pooling, boosting the attention mechanism’s response to maximum gradient feedback. Furthermore, the combination of spatial attention and channel attention demonstrates superior performance compared to channel attention alone. And adding spatial attention to channel attention verifies that using both is better than using channel attention alone. In our Feature-wise Attention, we introduce soft pooling [

14] as a novel contextual information to provide distinct gradient feedback for individual features. This approach assigns different attention weights to different features, thereby enhancing the preservation of texture information in the image instances.

3. Materials and Methods

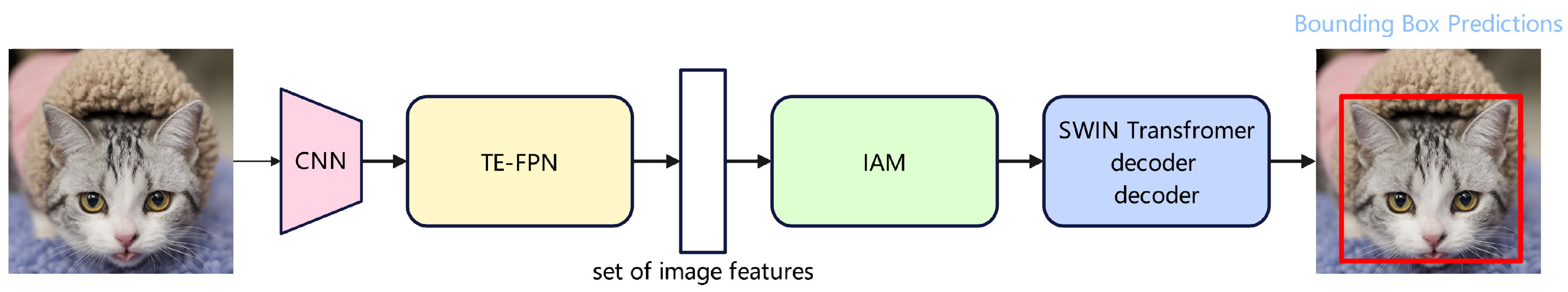

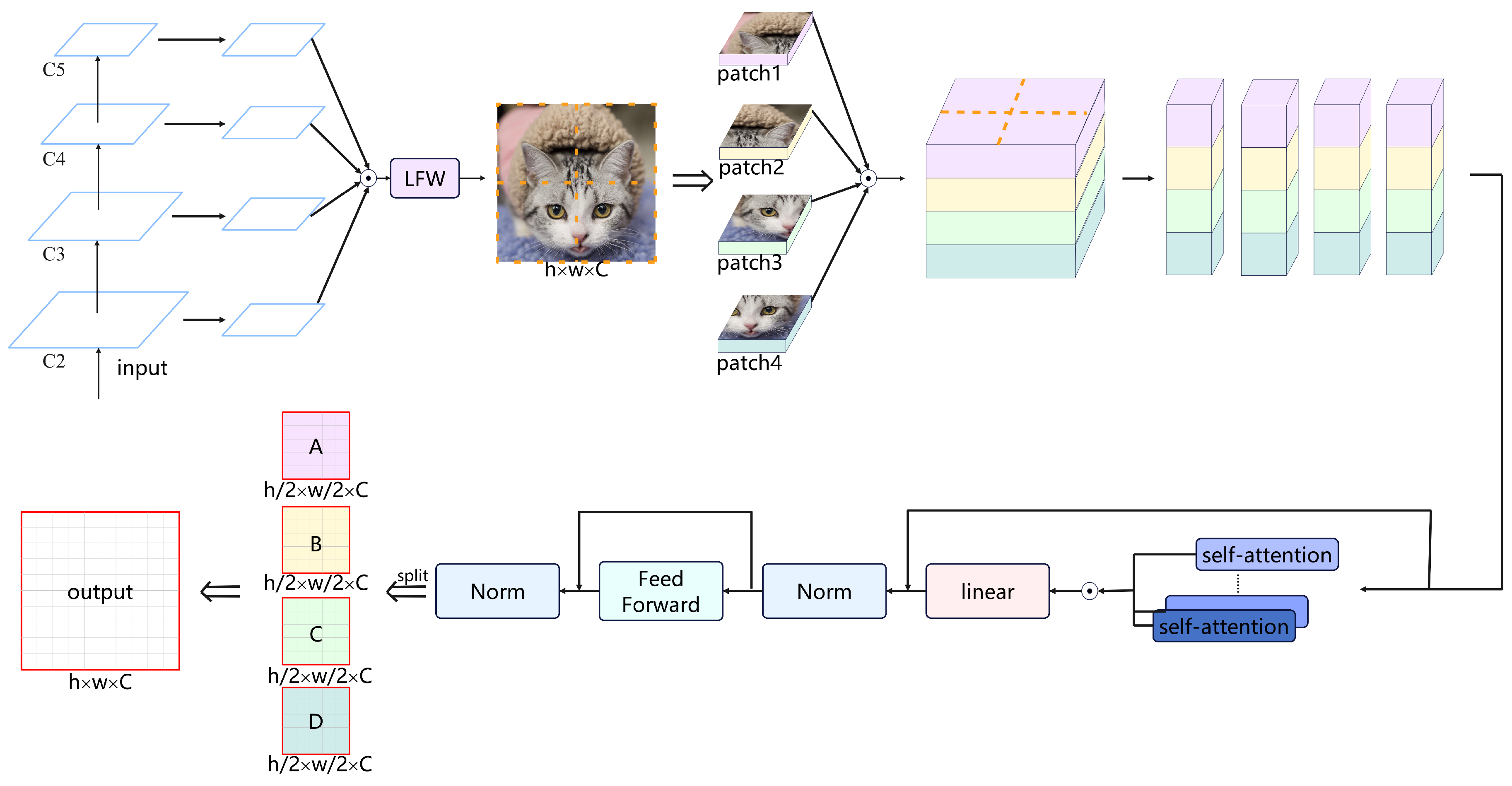

Figure 1.

TIG-DETR comprises a backbone network, a new pyramidal structure known as Texture-Enhanced FPN (TE-FPN), and an enhanced DETR detector.

Figure 1.

TIG-DETR comprises a backbone network, a new pyramidal structure known as Texture-Enhanced FPN (TE-FPN), and an enhanced DETR detector.

The proposed Texturized Instance Guidance DETR (TIG-DETR) architecture comprises a backbone, an FPN network, and a DETR-based detector. In order to enhance the model’s localization capability, we introduce a bottom-up path in the FPN that retains the texture information of the feature maps and combine it with the pyramidal features produced in the top-down path of the FPN. This fusion results in a feature map that contains both abundant semantic and texture information. The SRS module is employed to integrate the features produced at each level of the feature pyramid, and Feature-wise Attention is utilized to enhance the features of the resulting output feature map. Within the DETR-based detection model, we employ local self-attention to improve the recognition performance of small object instances and facilitate faster model convergence. Additionally, we introduce a module to address the limitations of local attention in perceiving large object instances, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to detect small object instances without compromising its performance in detecting large object instances.

3.1. TE-FPN

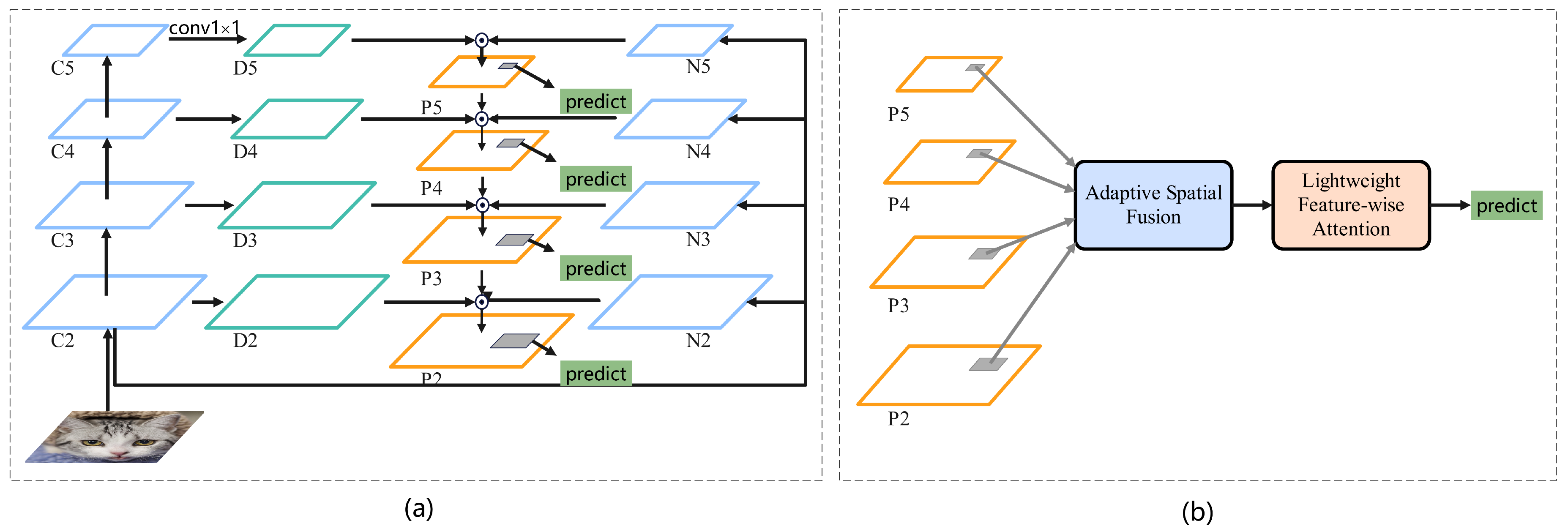

Figure 2.

Overview of TE-FPN. The proposed approach introduces an architecture called Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up architecture (ETA), which allows the input of low-level features to each level of the feature hierarchy. The lightweight Feature-wise Attention (LFA) is employed to extract channel weights using the channel attention module, which are then used to generate the final integrated features. The Feature-wise Attention (FWA) leverages multiple contextual information to acquire channel weights and enhance the features of the final output feature map. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the architecture of Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up approach. (b) Schematic diagram illustrating the enhanced features using Feature-wise Attention.

Figure 2.

Overview of TE-FPN. The proposed approach introduces an architecture called Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up architecture (ETA), which allows the input of low-level features to each level of the feature hierarchy. The lightweight Feature-wise Attention (LFA) is employed to extract channel weights using the channel attention module, which are then used to generate the final integrated features. The Feature-wise Attention (FWA) leverages multiple contextual information to acquire channel weights and enhance the features of the final output feature map. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the architecture of Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up approach. (b) Schematic diagram illustrating the enhanced features using Feature-wise Attention.

The top-down propagation of robust semantic information by FPN enhances the model’s ability to accurately classify features at all levels of the pyramid. The accurate localization of instances in the model relies on their high response to instance parts or edges, whereas the bottom-up path approach effectively propagates robust TEXTURE information, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to localize features at all levels of the feature pyramid. In this paper, we propose a new pyramid structure Texture-Enhanced FPN (TE-FPN), which contains a bottom-up path leading from the low level of the backbone network, so that the fused feature map has both strong semantic and texture information. Additionally, we introduce a novel channel attention mechanism to the Soft RoI Selection process, aiming to further enhance the fused features.

Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up architecture. FPN acquires features from the backbone, and a large amount of texture information is inevitably lost when the backbone is downsampled, a situation that may affect the accuracy of the detection network in obtaining information about the location of instances in the image. To address this limitation, we incorporate an ’Enhancing texture information with a bottom-up architecture’ (ETA) into FPN, aiming to enhance the texture information in the feature map at each level. Following the definition of FPN [

10], feature layers of the same size are generated in each network phase, and different feature layers correspond to different phases of the network. The Resnet-50 [

33] serves as the backbone network, and

represent the feature layers generated by the FPN.

represent the feature layers at different stages in the backbone network, and

represent the feature layers of

after dimensionality reduction using convolution. From C2 to C5, P2 to P5, and D2 to D5 spatial sizes are gradually downsampled with a downsampling factor of 2.

represent the feature maps newly generated by the bottom-up path, corresponding to

.

Specifically, the first step is to reduce N2 to C2 using convolution with a channel dimension of 256. This channel dimension aligns with the feature map in FPN and enables effective fusion between the two feature maps. Subsequently, the downsampled feature map is further downsampled with sampling coefficients of 2, 4, and 8 to generate

, preserving more texture information compared to conventional convolutional downsampling. The process is described as follows:

Where denotes the downsampling of the sampling factor of

Finally, depicted in

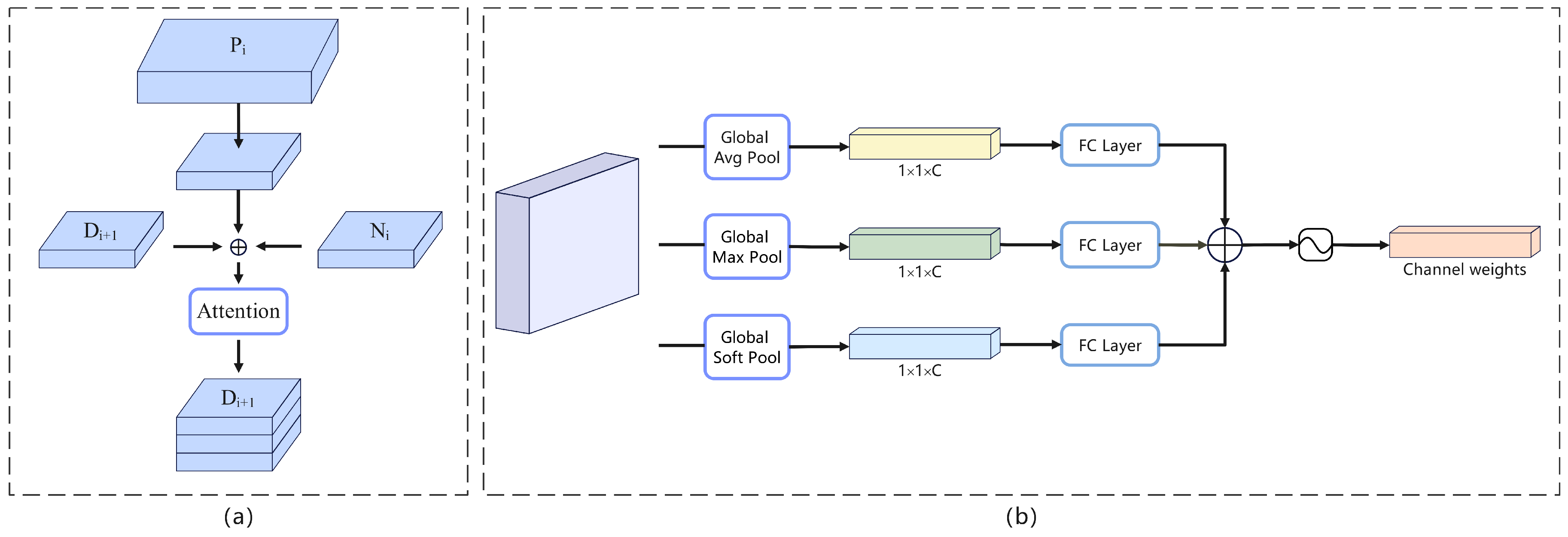

Figure 3(a), we up-sample Pi using a sampling factor of 2 and merge the up-sampled feature map with Ni+1 and Di+1, which have the same size, to generate Pi+1. Notably, P5 is obtained by merging only D5 and N5. The resulting fused feature map contains a combination of rich semantic and texture information. To mitigate the confounding effect after feature fusion, we employ a Lightweight Feature-wise Attention (LFA) module, as shown in

Figure 3(b). In this module, we implement a lightweight attention mechanism using FC layers instead of the more complex shared MLP layers, and combine the output feature vectors through element-wise summation with a sigmoid function. The process can be summarized as follows:

Where, denotes the lightweight channel attention function, denotes the sigmoid function, , , denotes the global average pooling, global maximum pooling and global soft pooling. Respectively, lightweight Feature-wise Attention is used to mitigate the confounding effect after feature fusion, rather than enhancing the features themselves.

Feature-wise Attention.During the target detection task, the detector heavily relies on the edge and texture information of the instances in the image to accurately delineate the instances. However, the multi-scale feature fusion can introduce a blending effect, leading to discontinuity in the fused feature map features. This can result in the detector acquiring incorrect edge and texture information of the instances, ultimately affecting the accuracy of instance localization and detection tasks.To mitigate the influence of the blending effect on the model, we introduce a novel attention module called ’Feature-wise Attention’ in its lightweight version, specifically designed to address the impact of the blending effect on model performance. In this work, we replace the ROI module with the Soft RoI Selection (SRS) module for feature fusion across different scales in the feature pyramid. Additionally, we incorporate the standard Feature-wise Attention to enhance the features in the final output.

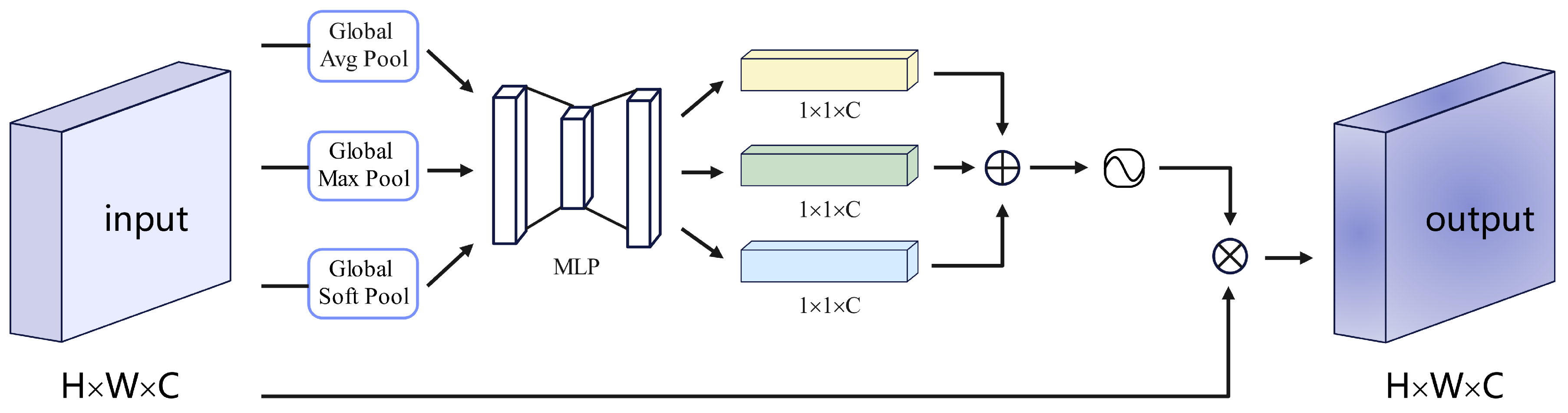

The Feature-wise Attention (FWA) is illustrated in

Figure 4. In this mechanism, we first utilize global average pooling, global soft pooling, and global maximum pooling to obtain three different spatial contexts. These contexts capture various aspects of the feature map. Next, each context is processed through an MLP layer with shared parameters. Finally, the resulting feature vectors are combined using element-wise summation followed by a sigmoid function. The channel attention in FWA focuses on identifying significant features within the graph. Global average pooling provides feedback for every pixel point on the feature map, while global maximum pooling focuses on gradients by considering only the areas with the highest response. On the other hand, soft pooling [

14] produces diverse gradient feedback for different pixel points during gradient backpropagation. Global average pooling tends to capture overall image features, global maximum pooling emphasizes instance edge information, and global soft pooling captures the overall texture information of the instance. By incorporating the global soft pooling contextual information and assigning higher weights to each pixel point of the instance, we enhance the texture information of the instance in the image. The Feature-wise Attention mechanism can be summarized as follows:

where denotes the

attention mechanism and

denotes the sigmoid function. By adding

, the texture information of the instances in the image is enhanced to obtain better localization.

3.2. Instance Based Advanced Guidance Module

The transformer used in our TIG-DETR detector follows the structure of Shifted Window based Self-Attention in SWIN-T. It replaces the multi-headed self-attentive module in DETR with W-MSA and SW-MSA in an alternating manner. The main goal is to reduce the computational complexity of the Transformer part in DETR, enhance the detection performance of small object instances, and speed up the model convergence. However, the limitation of interaction between windows in Shifted Window based Self-Attention affects the detection performance of large object instances. To address this, we introduce a new module called Instance Based Advanced Guidance Module (IAM) before the encoder. This module allows the model to perceive the instances in the image before performing local self-attention, compensating for the degraded detection performance of large object instances caused by the window interaction limitation.

Specifically, as shown in

Figure 5, the images from different stages in the backbone undergo a scale-invariant downsampling process to achieve a consistent channel dimension. They are then resized to the final output size. Afterwards, they are fused with the output image at multiple scales, enabling the fused feature map to combine information from different scales and enhance the texture information of the image.After undergoing an LFA, the fused feature map, originally of size

, is divided into

patches. In

Figure 5, we use M=2 as an example. These patches are fused together through concatenation, resulting in a patch of size

. The different colors within the fused patches represent the channel information of the patches at different locations. Each pixel within the fused patch contains positional information from the patches at different locations, allowing the model to extract global features, contextual relationships, and better perceive objects of varying sizes.The fused patch is then passed through the multi-headed self-attentive module, and the output patch is used to reconstruct the original feature map.We believe that this method is advantageous for improving Shifted Window based Self-Attention, as it enables the feature map to capture instances before window attention. Despite a slight increase in computational complexity compared to Shifted Window based Self-Attention, we have successfully implemented this approach. The details are as follows:

In the equation, N represents the edge length of the shifted window. It is observed that the computational complexity of the global MSA increases quadratically with . When N remains constant, the computational complexity of W-MSA becomes linear. In our IAM, with M fixed, the computational complexity of in this part is much smaller than . But for is only a linear increase, much smaller than the difference between the computation of and . Consequently, the computational complexity of IAM is still significantly lower compared to the global MSA.

By performing the mentioned operations, we enhance the texture information of the image and establish associations among individual pixel points within the image prior to applying movable window attention to the entire image. This allows the model to perceive instances in the image before the finer self-attention operation, thereby improving its ability to detect large object instances. A feedforward network (FFN) is employed after the IAM module.

We present the generalized Instance Based Advanced Guidance Module, which can be applied to various backbone networks without the need for FPNs. In the case of a backbone with FPNs, we utilize FPNs to replace the multiscale fusion component of the model.