1. Introduction

Especially with the prevalence of smartphones in the last decade, touch screens are everywhere in our daily life: mobile phones, kiosks, notebooks, tablet PCs, control interfaces of smart home appliances, etc. However, they mostly lack haptic feedback on their surface which as a supportive sensory channel could have a high potential to improve task performance and usability [

1,

2]. Over the last decades, 2 main methods to obtain haptic feedback on touch screens have stood out among others: 1) electrostatic actuation and 2) electromechanical actuation. In the former method, a conductive transparent layer (i.e. ITO films) embedded in the touch screen is excited with alternating voltage [

2,

3]. And the latter is performed using different types of electromechanical actuators such as vibration motors, linear actuators, piezoelectric patches, electroactive polymers etc. which are mechanically coupled to the touch screen [

4,

5]

Electrostatic actuation requires the relative movement of the user’s finger on the display at all times because it is mainly based on the change of the friction force between the display surface and the finger. On the other hand, electrostatic force and hence the friction force can be easily manipulated by varying the excitation voltage with a microcontroller. Moreover, touch interface systems actuated electrostatically do not include mechanically moving parts which would reduce the life span of the appliance.

Typically, researchers employ the well-known surface capacitive touch sensor (Model: 3M SCT3250) to implement the electrostatic actuation method [

1,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Here, the amplified excitation voltage is applied to the electrode embedded in the touch display, and the electric charges are distributed evenly on the entire conductive layer. So, during a time period there can be only one haptic effect to be sensed by the contacting finger on a surface capacitive glass (3M SCT3250). Suppose that we refer to a finger of the current/different user by saying “natural stylus”. It is actually an illusion that the user gets different haptic feedback on different locations of the electrostatically actuated display. A second natural stylus would perceive the same haptic feedback even if it had contacted a different location, simultaneously. At this point, one of the biggest drawbacks arises: there is actually no multi-haptic feedback in those studies. Multiple haptic effects felt via several natural styli interacting with the touch display can only be obtained by “separating” conductive surfaces or by specific electronic circuitry mounted to the natural styli. In a novel demo study, the ITO layer of a surface-capacitive touch sensor is partitioned by laser ablation method so that every “ITO-cell” can be excited individually [

12]. So, the haptic feedback is literally localized where users perceive different haptic effects via each individual natural stylus. However, any kind of localization of the haptic feedback using specific circuitry is not known to the authors.

Similar haptic localization issue applies also to the second method (electromechanical actuation) since the actuators vibrate the entire surface they are attached to. Moreover, in this method it is necessary to mount the actuators not beneath the display area, but rather under the peripheral edges (i.e. screen bezels or the surface borders excluding the visual area) since they would obviously block the visual information coming from the display. So, focusing of the produced vibration on the desired locations comes into play as the new research problem. Nevertheless, there are some signal-processing solutions to overcome the problem of haptic feedback localization [

13,

14]. This technique is called time-reversal focusing where the mechanical waves generated by multiple piezoelectric actuators are focused spatially and temporally. However, they are not easy to implement and might require considerable processing power.

In this study, we propose a simple but effective method where transparent piezoelectric polymer (PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride) films can be utilized to generate localized haptic feedback on touch displays. Furthermore, the optical transparency feature of the film actuators provides design flexibility since they can be mounted in any shape and location to the touch interface.

Electroactive polymers have various application areas as actuators. In a remarkable robotics application, the authors built a soft robot that mimics the movements of an insect [

15]. Here, high strain outputs of PVDF polymer actuator make the soft robot pace at a relative speed of 20 body lengths per second, carry lightweight loads, and climb slopes.

Another study is about active vibration control on plate structures where laminated PVDF actuators are utilized [

16]. The authors performed active control experiments by applying sinusoidal signals at multiple frequencies and reached a vibration reduction of 20 dB on the steel plate.

Chilibon et. al compared different types of bimorph transducers: PZT and PVDF-based piezoelectric materials in their work [

17]. Two PZT patches with 0.3 mm thickness produce more than 2 mm displacement at the cantilever tip. However, the same structure with a 25 μm thick PVDF polymer actuator provides more than 1 mm displacement at the tip of the beam. There is at least 5-fold supremacy when compared to the PZT actuator.

Perez et al. developed a PVDF-based bimorph actuator for laser scanners [

18]. This actuator is designed to induce vibrations on a small mirror located at the beam-tip, weighing 160 mg, at a frequency range of up to 3 kHz.

One of the interesting application areas is introduced by Chen et al. where PVDF-based piezopolymer actuators are used to adjust the surface accuracy of large-scale space antennas [

19]. The authors investigated also the task performance of several types of PVDF-polymers. Similar electrostrictive materials can also be utilized to control thin shell reflectors in space industry [

20].

Furthermore, PVDF-based piezoelectric materials can be used as pressure sensors and nanogenerators since they can respond to changes in physical quantities such as pressure, sound waves, temperature and air flow by converting mechanical energy into electrical energy [

21,

22]. In a similar manner, Jin and his collaborators embedded PVDF arrays inside a rubber cylinder to measure the internal stresses generated by several external factors [

23].

In their study, Hu et. al developed a finger-shaped haptic sensor using a thin PVDF-film which can evaluate fabric surfaces by measuring height and depth variations in surface textures through relative motion [

24].

PVDF-based electroactive polymers are also used to generate haptic feedback. Matysek et al. fabricated a 3x3 matrix array of multilayer dielectric elastomer actuators in their study [

25]. In another work accomplished by Stubning et al., a design procedure for a transparent EAP-stack actuator with multiple layers was introduced. However, neither of those actuators were implemented on a display interface [

26]. Additionally, the multilayer structure of the EAP-stack actuator may result in decreased transparency and therefore lower visual quality of the display.

2. Methods

To test the proposed concept, two transparent touch interfaces are designed and constructed. They consist of transparent plastic plates and multiple transparent PVDF-film actuators attached beneath the touch surface. Two different configurations are examined using analytical and experimental methods: a) First, the modal analysis is performed in order to identify the proper characteristic parameters such as actuation frequency and vibration amplitude considering human-factors principles. b) Afterward, these findings are utilized to evaluate subjects’ performances via experimental studies.

2.1. Hardware

Multiple transparent PVDF-film actuators (20x20x0,05 mm) are attached to the bottom of a transparent PVC (polyvinyl chloride) plastic layer (100x50x0.6 mm) which is constrained via a clamp mechanism along its rectangular perimeter. To ensure fixed boundary conditions, the plastic plate is clamped between two metal frames using several nuts and bolts on the sides. The structure stands on a 10-inch PC monitor which is placed horizontally on a desk. Vibration isolation between the structure and the monitor is provided with a 1 cm thick foam rubber.

Unipolar analog input signals are generated by a 32-bit microcontroller (STM32F407G). An executable program is developed in Unity software to communicate with the microcontroller for conveying indicators of the randomized signals. At the same time, it records the choice responses of the subjects via an interface. A custom-designed amplifier circuit with adjustable gain amplifies the unipolar signals and excites PVDF-film actuators. It hosts also a high-pass filter stage to eliminate DC components originating from the microcontroller. Hence, pure sinusoidal high-voltage signals are obtained on the amplifier output. Finally, the excitation voltage is directed to the relevant actuators by a multi-channel relay module which is controlled by the microcontroller board, as well. To ensure proper connection with transparent actuators, electrically conductive adhesive tapes are utilized. In case of incomplete connectivity silver paste is applied.

PVDF-film actuators are glued (clear epoxy adhesive) to the plate in such a way that the positive electrodes are positioned directly beneath the layer. Hence to prove the safety of the interface, electrical breakdown for the utilized PVC plate must be investigated. The dielectric strength of the PVC material is about 25 kV/mm [

27]:

Since operating excitation voltages are below 300 Vpp the setup is safe to conduct human experiments.

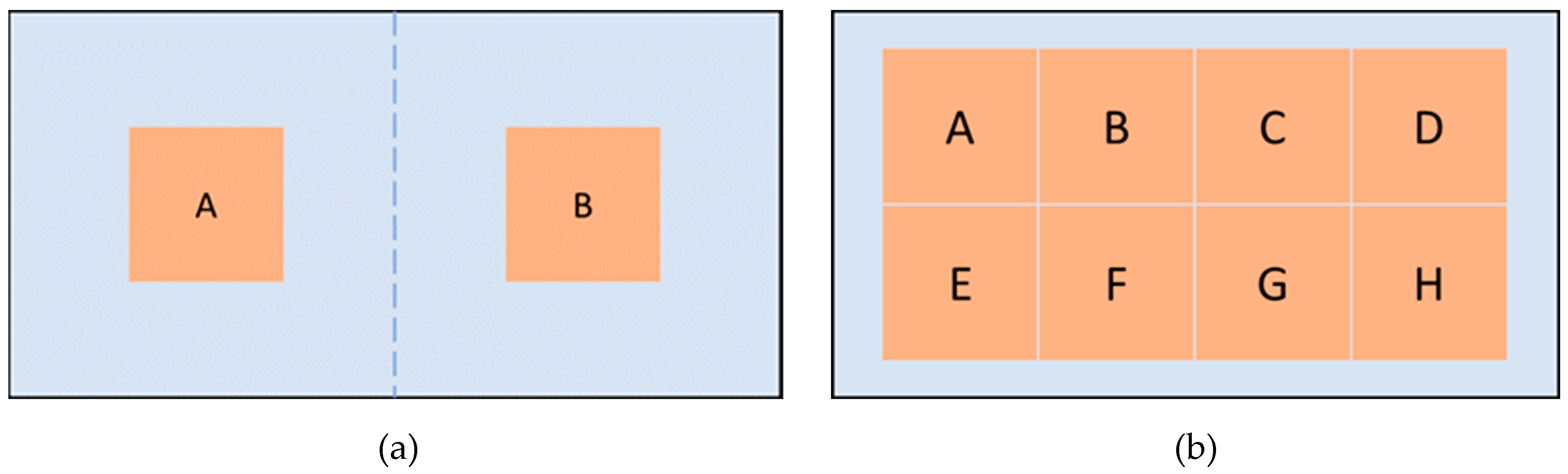

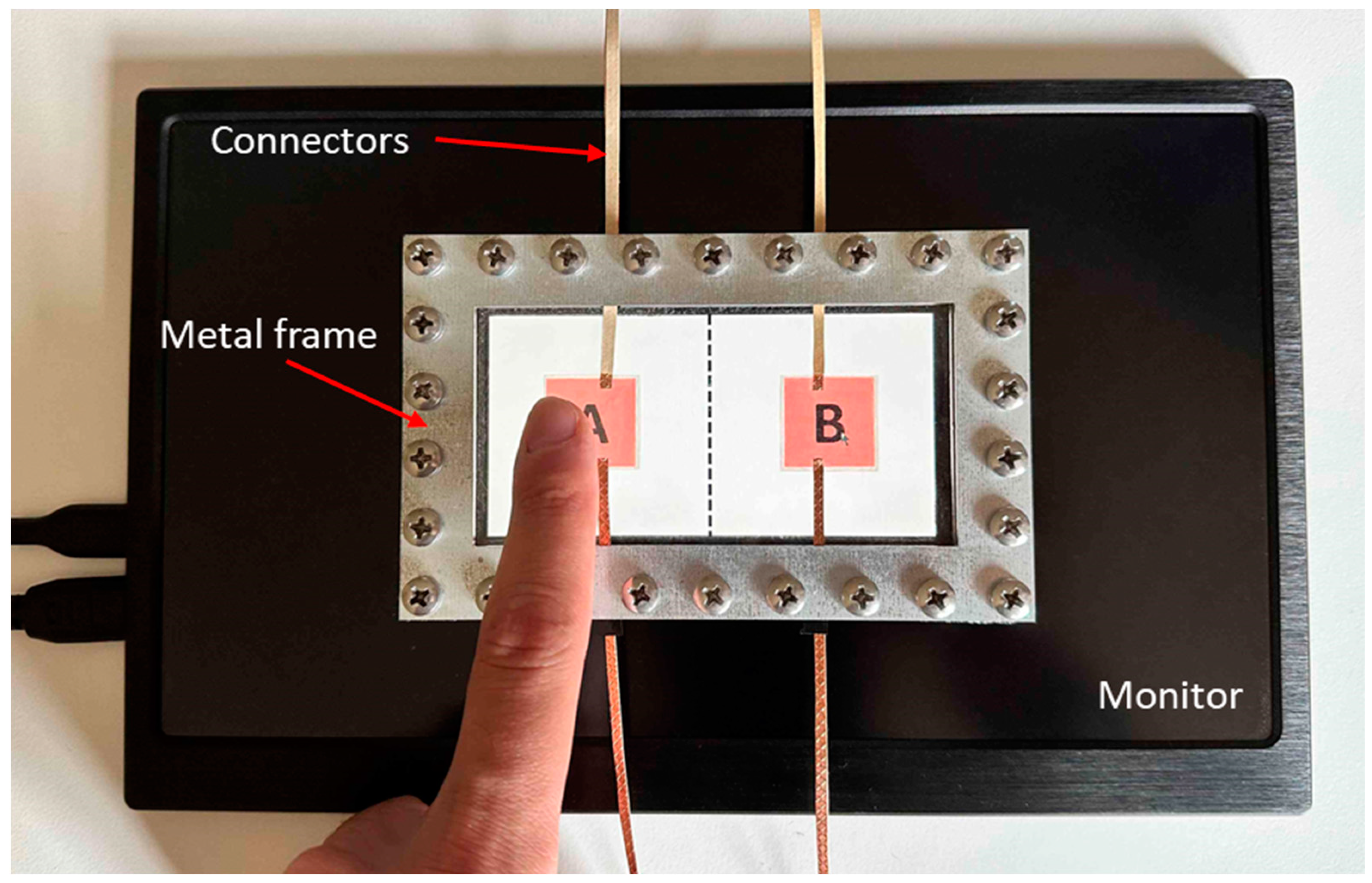

For the experiments, two identical touch interfaces with different actuator configurations are prepared. In the first configuration, two actuators are mounted to the right and left sides, respectively (

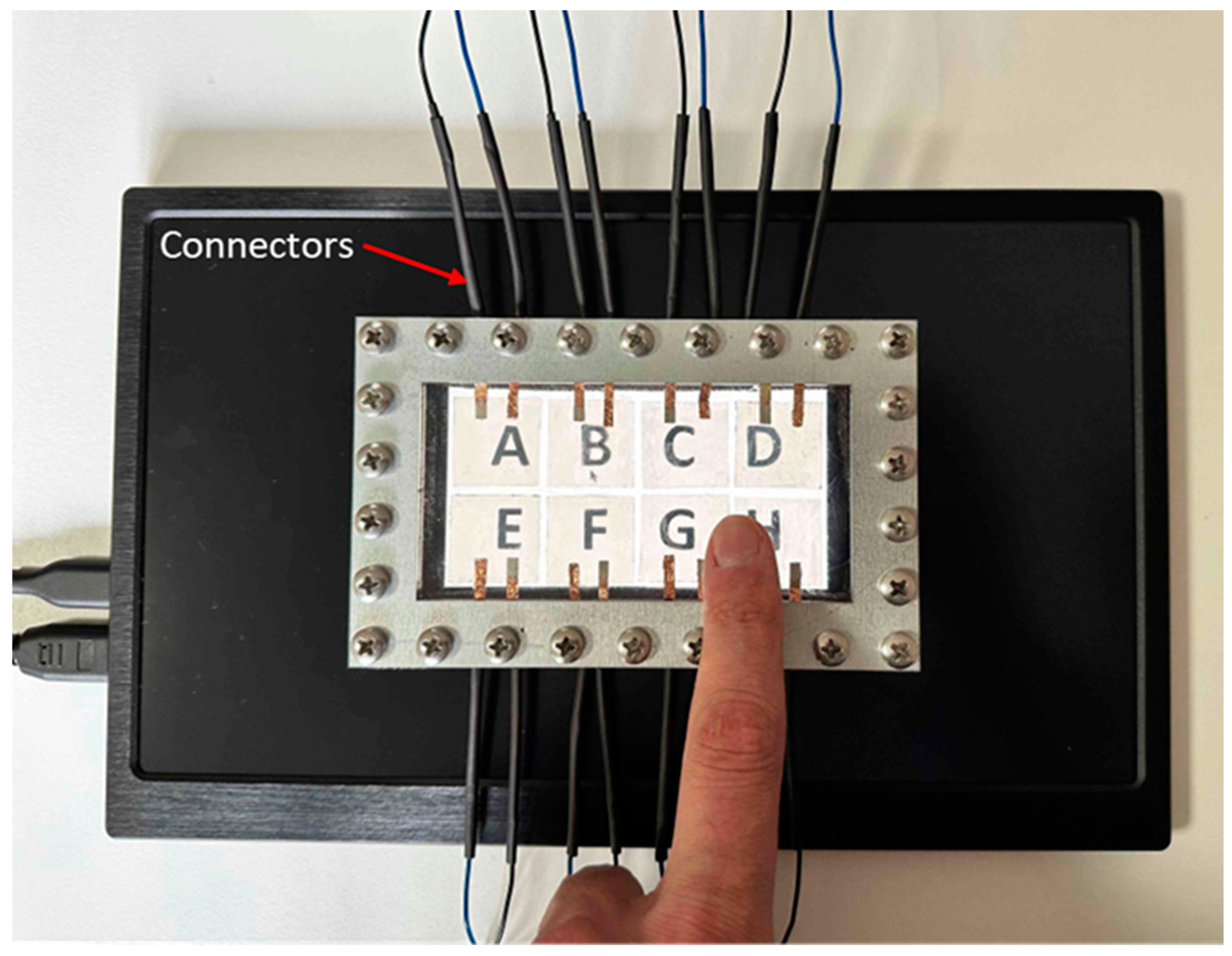

Figure 1a). The second configuration consists of 8 actuators which are mounted in a 2x4 array formation (

Figure 1b). Both configurations are arranged symmetrically with respect to the origin of the surface geometry.

2.2. Finite Element Analysis

2.2.1. General Information

The piezoelectric behavior for a general, anisotropic material is defined by two equations [

28,

29,

30]. Equation (1) is for the sensing and (2) is for the actuation mode:

where;

D: The electric displacement vector

T: The stress vector

E: The electric field vector

S: The deformation (strain) vector

s: Elastic compliance matrix

d: Piezoelectric charge constants matrix

ε: Dielectric constants matrix

and subscripts T and E indicate values at constant stress and electric field, respectively.

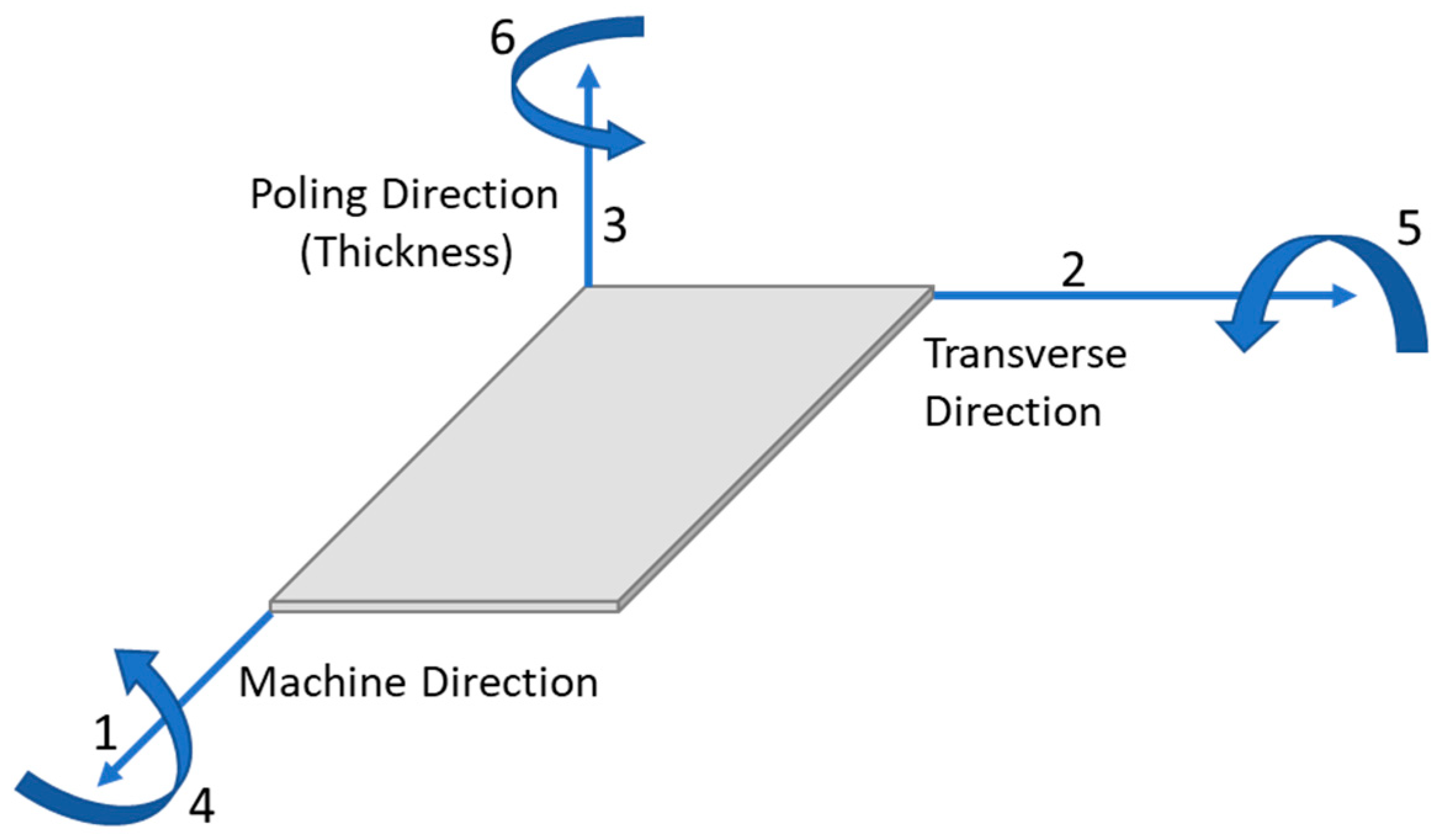

Generally, the non-zero and unique components of those piezoelectric coefficients, dielectric constants and elastic compliance tensors in piezoelectric materials are determined by different factors such as extrusion process or specific crystal symmetry [

31]. For instance, the transparent PVDF material (PolyK Technologies, LLC) used in this study is orthotropic. Orthotropic materials can exhibit different mechanical or electrical properties along 3 axes which are perpendicular to each other (

Figure 2).

Basically, governing piezoelectric equations can be rearranged for isotropic materials as follows [

21,

30,

32,

33,

34]:

where the variable d

ij means generated strain along j due to the electric field along i.

As anisotropic piezopolymers, PVDF materials generate different strain amplitudes under an electric field in the direction of polarization. Since the poling of PVDF-film sheet is in direction 3, d

24 and d

15 can be neglected [

22,

24,

34]. So, the matrix of piezoelectric charge coefficients is expressed as:

The required coefficients of the elastic compliance matrix are procured from several experimental studies [

27,

30,

32,

35,

36]. And the basic properties of the utilized PVDF material are given in

Table 1.

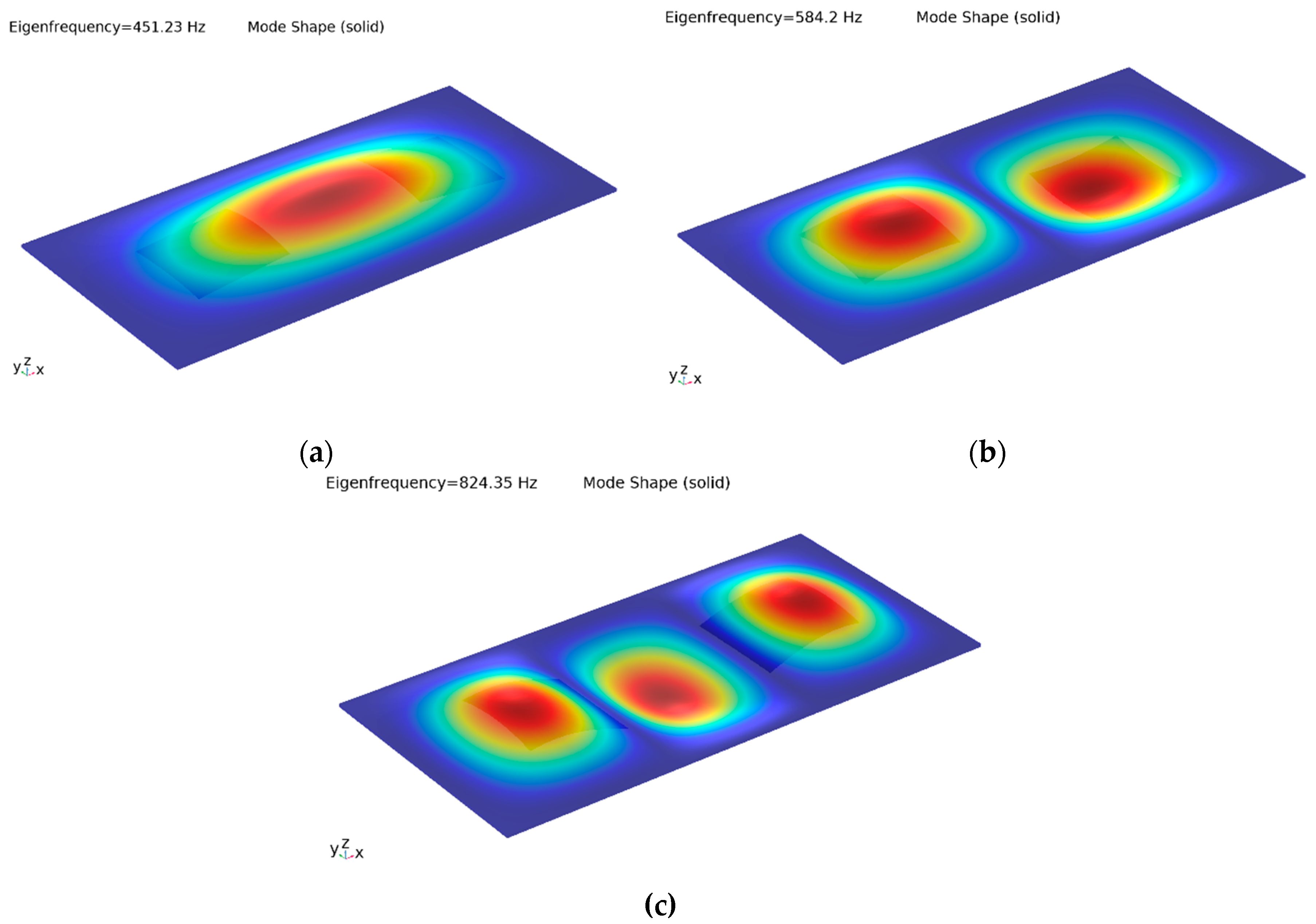

The structure is built and simulated in a finite element analysis program. After performing a modal analysis, the first 3 natural frequencies turned out to be ωn1 = 451.2 Hz, ωn2 = 584.2 Hz and ωn3 = 824.4 Hz.

Since each of the natural frequency values corresponds to a definite and distinctive mode shape of the structure (

Figure 3) according to basic modal analysis principles, natural frequencies must be avoided in order to generate localized vibrations at desired locations successfully. Thus, the frequency of the excitation voltage must not be selected in the vicinity of natural frequencies. Meanwhile, it should also be situated in the perception interval for human skin which can reach up to 800-1000 Hz [

37,

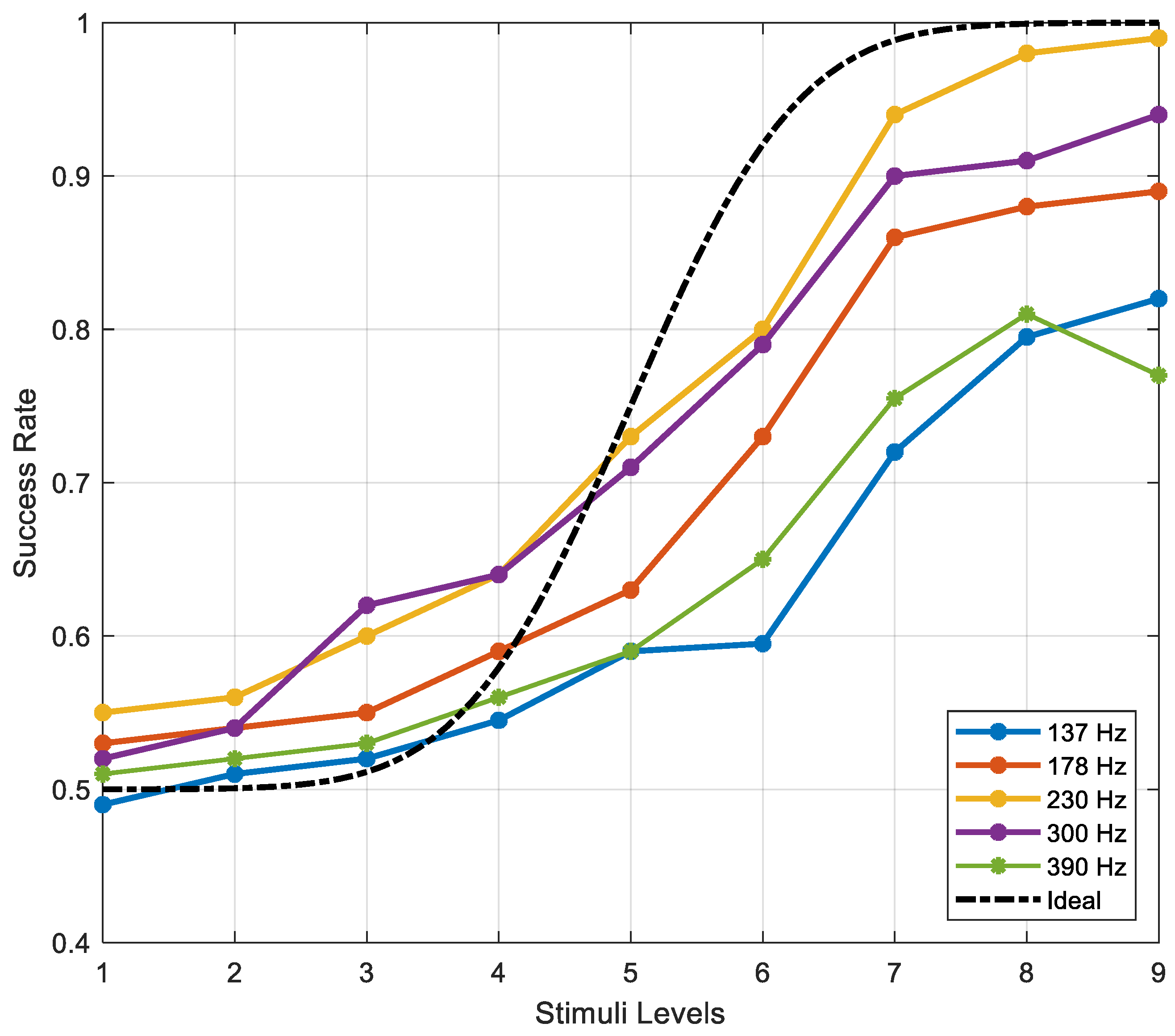

38]. Considering those design limitations, 5 frequency values equally spaced (%30) on logarithmic scale are selected: 137, 178, 230, 300 and 390 Hz [

39,

40].

2.2.2. A/B Configuration

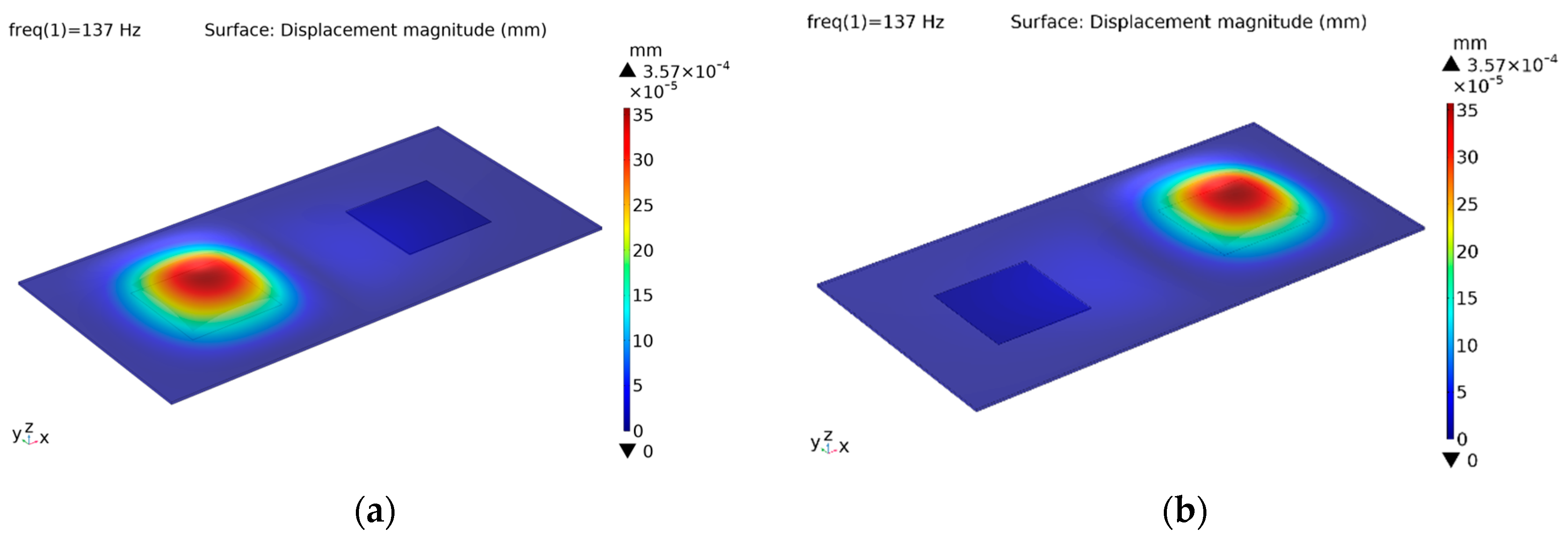

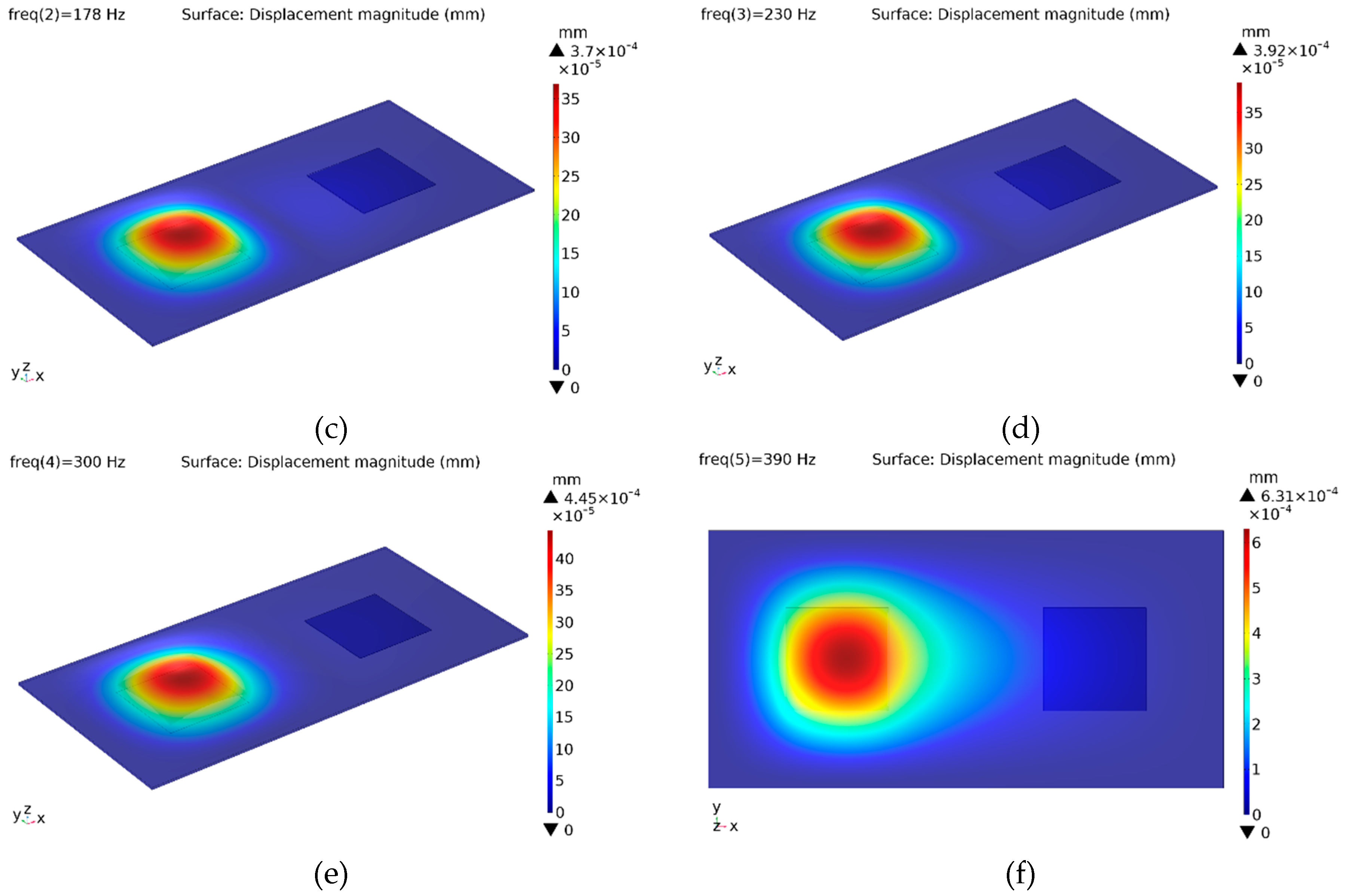

In the first configuration, both actuators are excited with a pure sinusoidal signal of 100 V peak-to-peak amplitude and with 5 different frequencies. Individual excitation of the PVDF-based actuators provides the localization of the vibration where the generated displacement amplitude reaches 0.36 μm, 0.37 μm, 0.39 μm, 0.45 μm and 0.63 μm depending on signal frequencies, respectively (

Figure 4). Those displacement amplitudes are higher than the absolute detection threshold for the human fingertip reported in literature [

41,

42]. Results obtained from the excitation at 137 Hz show the symmetry of the structure (

Figure 4a,b). The vibration patterns for the actuator-B at remaining frequencies are not given to save space.

It appears that the vibration pattern of the 390 Hz signal is pervasive to some degree due to its relative proximity to the first natural frequency, but it can still be considered localized.

2.2.3. Array Configuration

In the second configuration, each actuator is activated individually with 230 Hz sinusoidal signal. This value lies in the range of 200-300 Hz where the human fingertip is reported to be perceptually most sensitive to vibratory cues according to several studies [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Here, the vibration maps of only 2 conditions (actuators A and B are excited) are depicted (

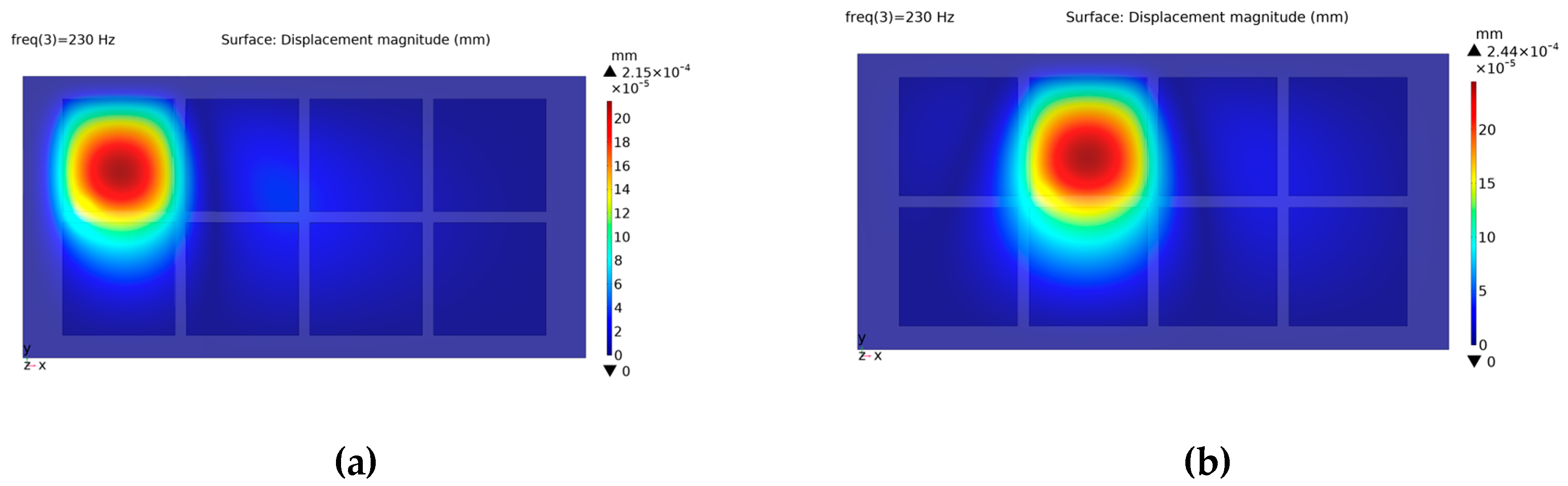

Figure 5). The other 6 vibration maps are not given because they are similar to the ones obtained by the excitation of the first 2 actuators due to the structural symmetry of the touch surface. In other words, the vibration maps formed by individually exciting actuators A, D, E, and H are similar in terms of shape and displacement magnitude. Likewise, the individual activation of the remaining actuators (B, C, F, and G) leads to the formation of similar vibration maps but with increased displacement magnitudes.

Finite element simulation results provide convincing evidence of distinct and prominent vibration patterns on the corresponding actuators, solidly proving the effectiveness of achieving localized haptic feedback (

Figure 5).

2.3. Experiments

2.3.1. A/B Configuration

The primary objective of the first experiment is to characterize the haptic interface by assessing and analyzing the key actuation parameters considering human factors: actuation frequency and detection threshold. For this, one of the classical psychophysical methods introduced by Fechner is used to estimate the absolute threshold value for detection: repeated-measures, within-subject method of constant stimuli [

47,

48]. It is accomplished with the one-interval, two-alternatives, forced-choice (1I-2AFC) paradigm since it can provide more objective psychophysical procedures.

Eight subjects (four female, four male) with a mean age of 28.9 took part in the experiment. All of them were right-handed and used the index finger of their dominant hand in the experiment. They did not report any sensorimotor impairment. Both experiments reported in this study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Gebze Technical University.

According to the well-known Weber’s rule, the just noticeable change in stimulus intensity is a constant fraction of the stimulus intensity [

47,

48]. Thus, both voltage and frequency levels used in human experiments are selected to be equally spaced on the logarithmic scale.

After some preliminary observations, 50 V is predicted to be the required voltage amplitude at 230 Hz to produce vibratory feedback at absolute detection threshold. Taking 50 V as the center value, 4 lower and 4 higher amplitudes of excitation voltage are added to the stimulus set which are equally spaced on logarithmic scale: 17 V, 22 V, 29 V, 38 V, 50 V, 65 V, 85 V, 110 V, 143 V.

The simulation outputs of the forced-vibration analysis for the A/B configuration have revealed that the excitation at each selected frequency produces similar vibration patterns, though with different displacement amplitudes (

Figure 4). So, the activation voltages are adjusted to eliminate the frequency effect and equalize the displacement amplitudes using proper gain coefficients (

Table 2).

For example, the amplitudes of the stimulus set are modified for 137 Hz:

The touch interface designed has a rectangular shape since lateral motion is the most effective method to explore the surface properties [

49]. Before the experiment, subjects were informed about their tasks and instructed to interact with the haptic interface as they would with a typical smart device equipped with a touch display. They were trained for approximately 3 minutes to become familiar with the haptic feedback effects generated by the touch-screen interface. In the training session, they were exposed to each stimulus twice (1 for each alternative side) at 230 Hz. In the experiment session, every subject conducted a set of 180 trials (9 stimuli) for each of 5 signal-frequency levels, a total of 900 trials. Hence, each stimulus appeared 20 times (10 times on A-side and 10 times on B-side). Those appearances were randomized block-wise: each stimulus was given once before any stimulus was given twice. This method helps to reduce the learning and carry-over effect and to increase statistical validity [

50]. The subjects’ task was to determine the side with the haptic feedback on it and to select it with a mouse located next to the monitor (

Figure 6). When they made the selection, the next trial was originated by the software immediately. The experiment for one subject lasted about 70 minutes.

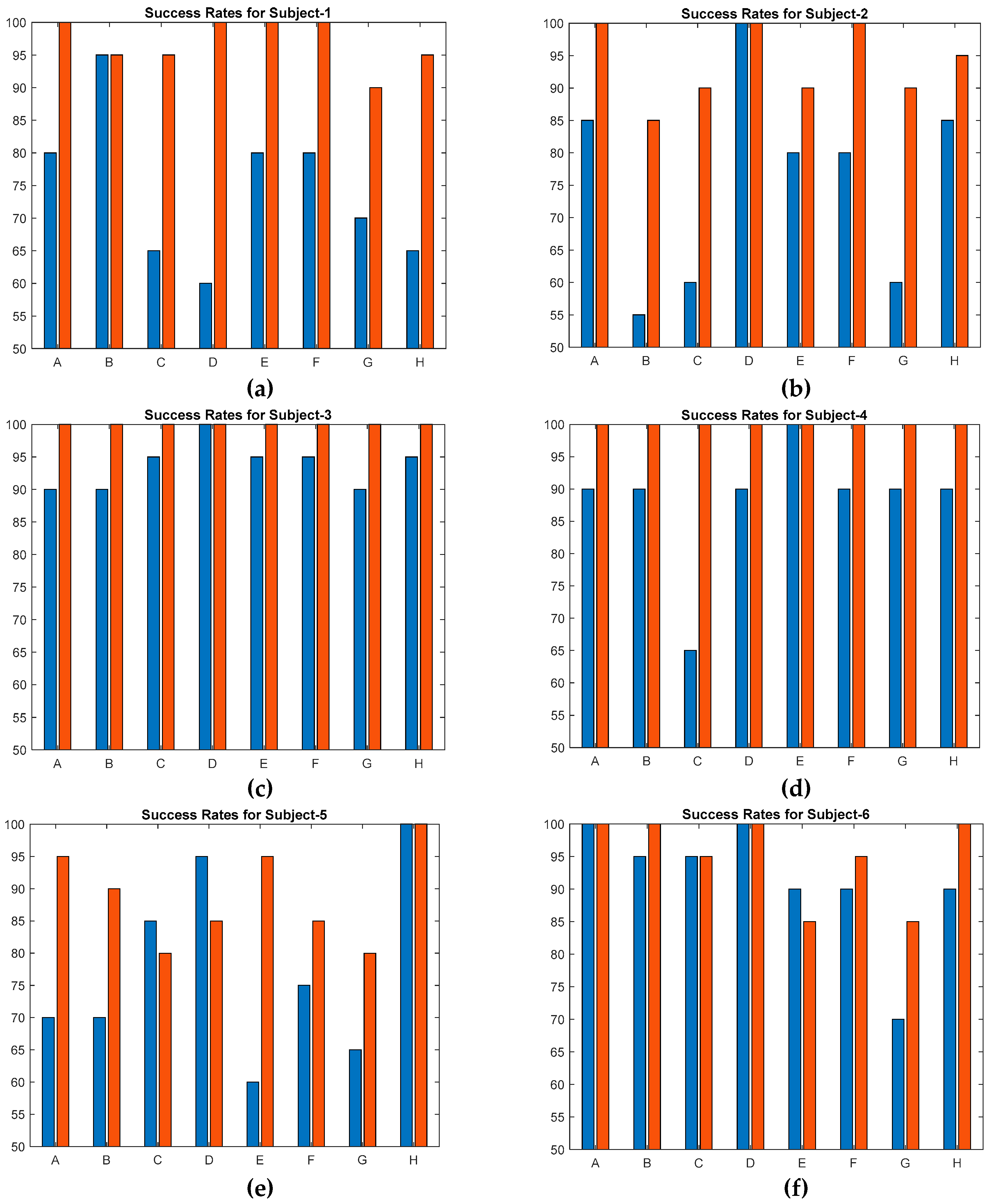

2.3.2. Array Configuration

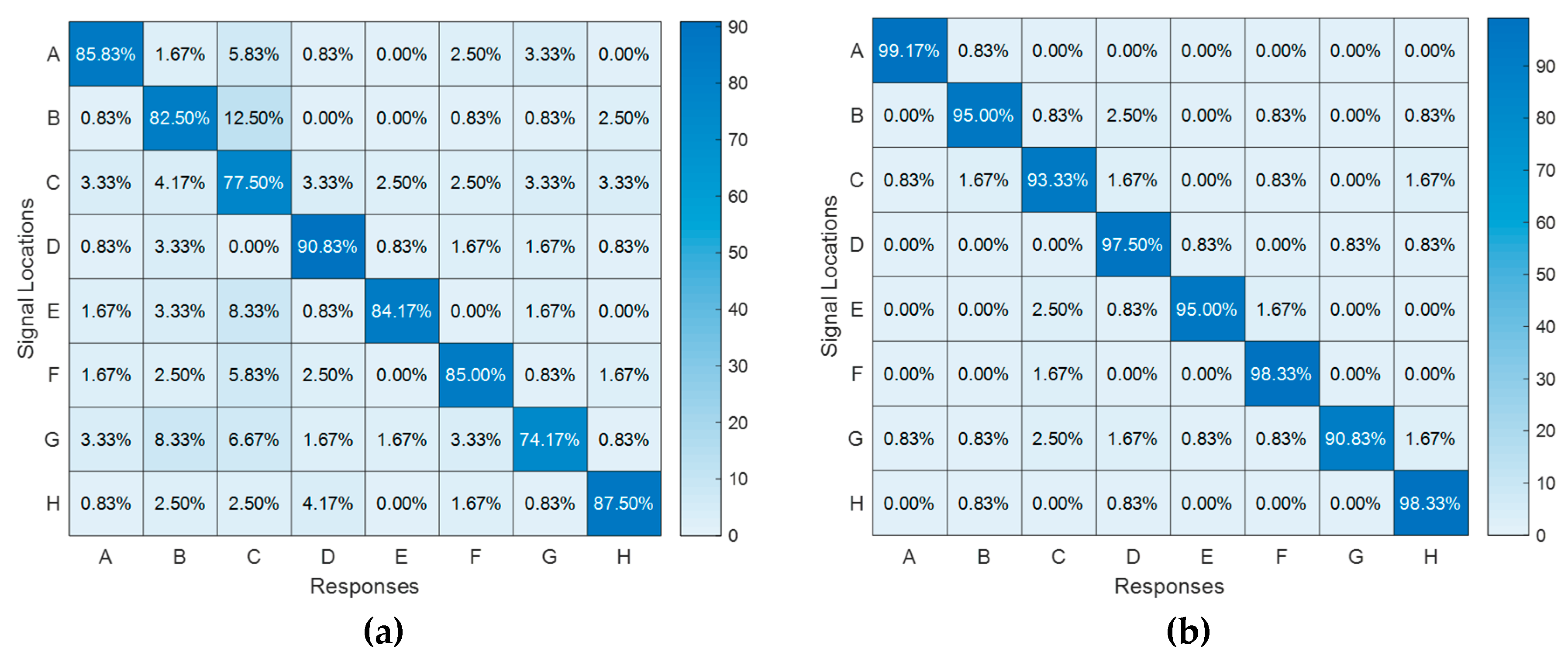

In the second experiment, a multiple-choice procedure is designed to prove the ability of the touch-screen interface to provide localized haptic feedback. Here, the subjects try to detect the one with haptic feedback out of 8 locations: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H (

Figure 7). 230 Hz is set to be the operating frequency for the pure sine signal, because according to the results of the human experiments with the A/B configuration, it is the critical member of the frequency set where the fingertips of the participants are most sensitive to vibratory feedback.

Two amplitudes are selected from the voltage stimuli set: one is the next greater one to the absolute detection threshold (65 V), and the other one is the highest level (143 V). Previous simulation results have shown that the generated displacement magnitude is higher when one of the actuators in the middle (B, C, F, or G) is actuated compared to the case when one of the actuators in the corners (A, D, E, or H) is actuated (

Figure 5). To compensate for this difference caused by the location effect, the gain coefficient 2.44/2.15 = 1.13 is used to increase the excitation voltage of the corner actuators.

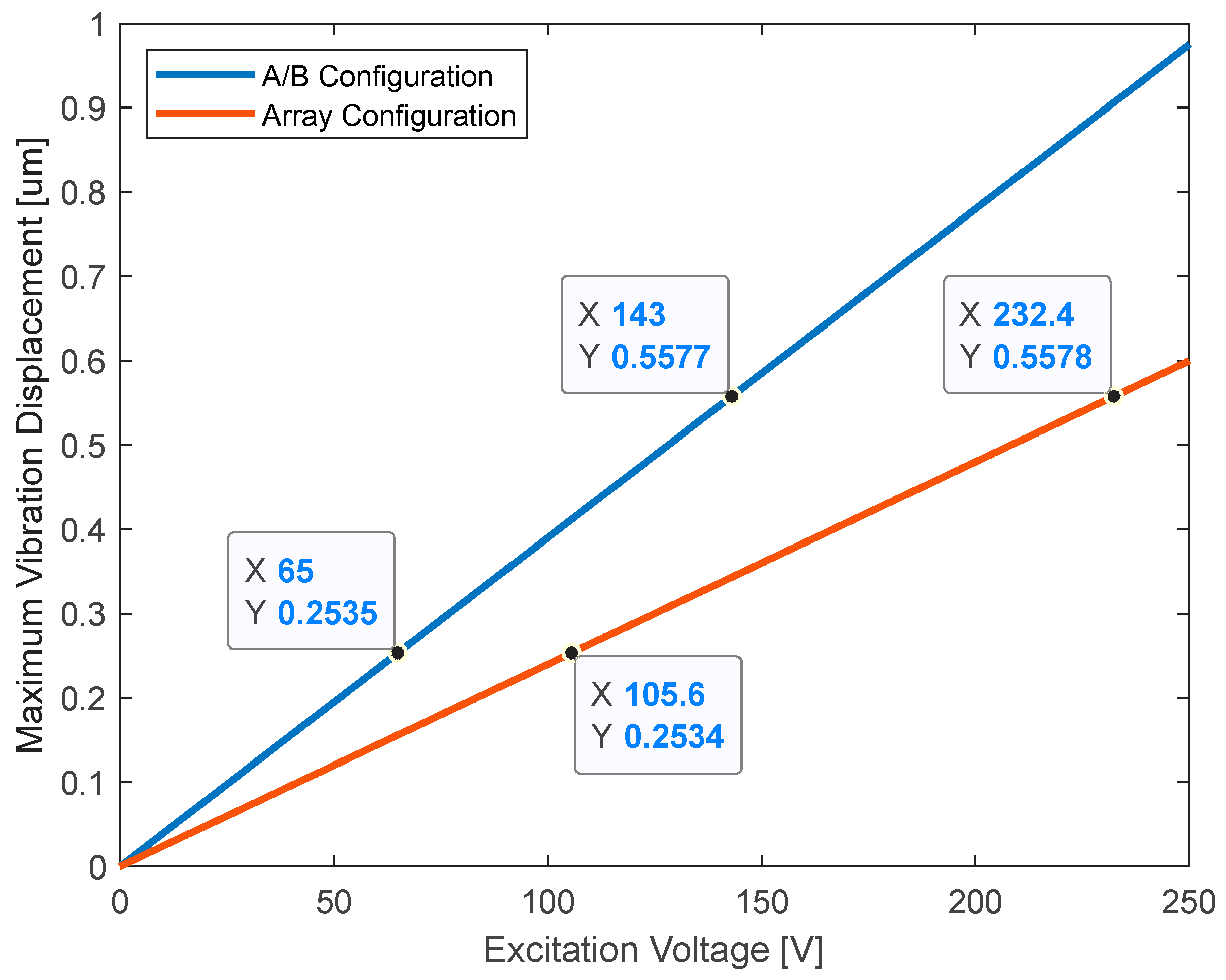

Additionally, the difference caused by the positioning of the actuators must also be eliminated. According to the finite element analysis results, two different configurations have led to maximum vibration magnitudes of 0.39 μm and 0.24 μm on the corresponding actuators at 100 V

pp and 230 Hz, respectively (

Figure 4 and 5). Since there is a directly proportional relation between excitation voltage and displacement amplitude of the generated vibration, the maximum displacement amplitudes produced in A/B configuration at 65 V and 143 V are 0.25 μm and 0.56 μm, respectively. To obtain the same displacement amplitudes in the array configuration, the excitation signals with voltage amplitudes of 106 V and 232 V shall be used (

Figure 8).

Six subjects with a mean age of 27.5 participated in the experiment which was conducted over two sessions. Before the experiment, subjects underwent a 4-minute training process. They were asked to explore the touch surface freely and to identify the specific location with the highest perceived haptic effect out of the eight available options with the mouse next to the monitor. In the training session, two different haptic cues (with amplitudes of 106 V and 232 V) appeared on each different location twice. In the experiment session, both signals are conveyed to each location 20 times. So, the experiment consists of totally 320 trials per participant. After each trial, the subject's response triggered the subsequent trial, in which haptic feedback stimuli were randomly delivered to different locations. Again, the stimuli are randomized block-wise. The multiple-choice experiment is completed approximately in 40 minutes.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, a haptic interface equipped with transparent PVDF actuators is introduced. In contrast to the work conducted by Stubning et al. in this study, the actuators are positioned beneath a transparent plastic plate [

26]. Moreover, unlike the approach of using a stack of actuators, this study accomplishes the goal of achieving accurate localized haptic feedback using only single actuators. Indeed, stack actuators can have the disadvantage of reducing the transmittivity of light, thus affecting the image quality coming from the display. This drawback underscores the efficiency of the proposed method in delivering precise haptic sensations while simultaneously simplifying the overall design. There are two more studies where researchers deploy transparent actuators to generate vibrotactile feedback. One of them involved the use of EAP (electroactive polymer) arrays and employed beat phenomenon to render haptic effects [

52]. The other one introduced transparent graphene-based stack actuators to generate bumps with high amplitudes on tactile displays [

53].

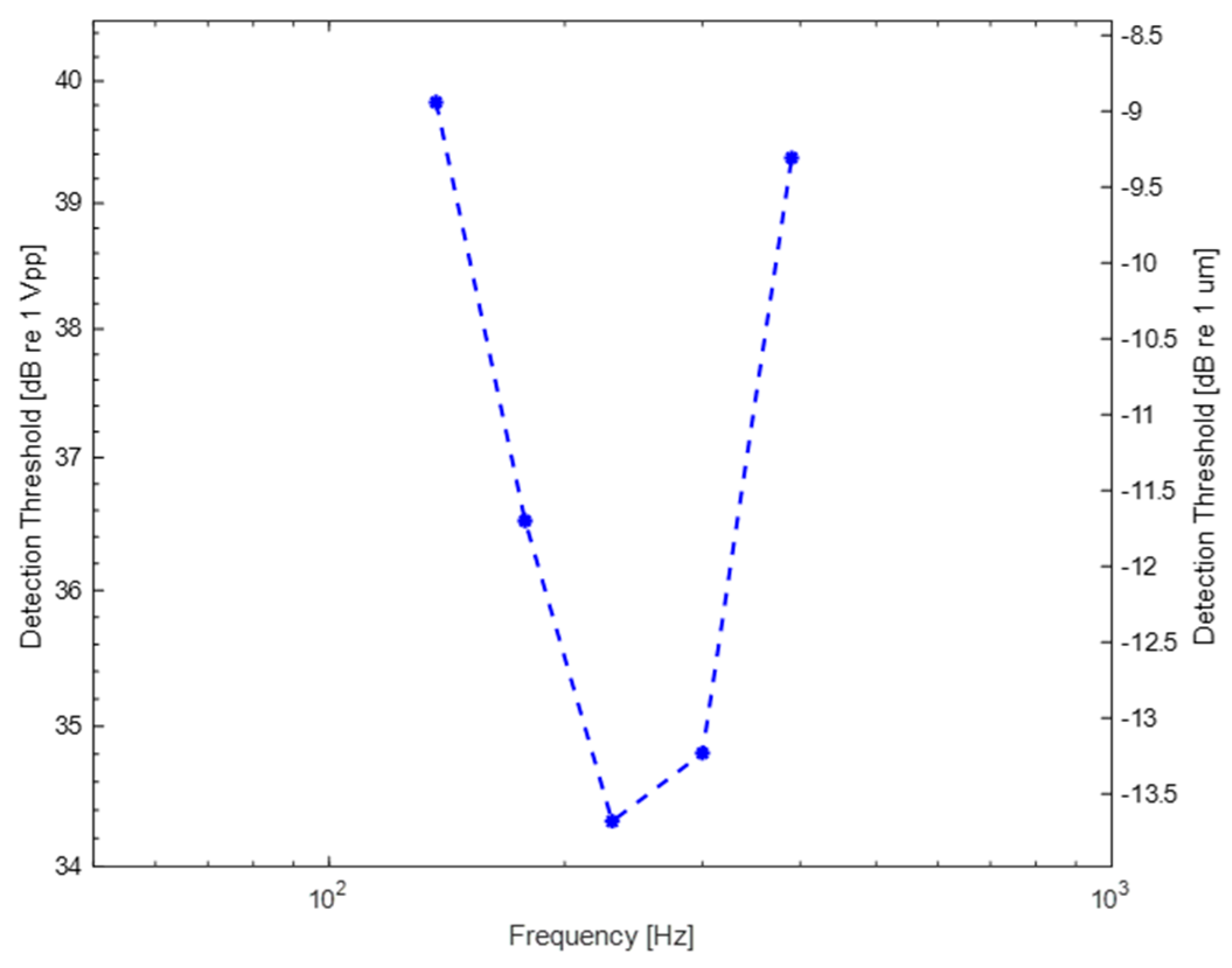

The concept of this study is introduced via two different arrangements: A/B- and array configuration. In the first configuration two actuators are mounted on the left and right sides of the rectangle plate. The Finite element analysis method is employed to simulate the structure and obtain information about relevant design parameters such as the frequency and amplitude of excitation signals and the generated amplitudes on the interface. Among the selected frequency set, 230 Hz is the frequency where vibration displacement threshold is at its minimum (34.3 dB re 1 V

pp). As expected, the human fingertip sensitivity represents a U-shaped curve: amplitude thresholds increase when the frequency is lower or higher than 200-300 Hz. Similar findings have been reported in many numerous previous studies as well [

2,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

51].

The second configuration consists of 8 actuators arranged in a 2x4 matrix formation and is designed to demonstrate the capability of generating localized haptic feedback on desired locations. The actuation frequency of 230 Hz is chosen based on the supportive findings from the first experiment. Two excitation amplitudes, 106 and 232 volts are selected: they generate maximum vibration displacements of 0.25 μm and 0.56 μm on the second setup, respectively. The success rates are averaged among 6 subjects and 8 different locations, resulting in an accuracy of 83% at low voltage and 96% at high voltage. Hence, the results, especially at higher voltage, strongly validate the localization process of the generated haptic feedback on touch displays, enhancing the overall user experience. Considering that the maximum amplitude used in this study is 232 V, it is evident that utilized transparent PVDF-based materials are suitable actuators for achieving localized and rich haptic effects since they are able to handle excitation ranges of up to 5000 V.

Although the application process of the actuators to touch surface poses challenges, this study serves as a good proof of the concept. In the future some microfabrication methods can be employed to produce touch interfaces with higher haptic resolution. It is important to note that a comprehensive vibration analysis will always be necessary in order to effectively implement this in real-life applications.