1. Introduction

A Native American proverb says: “Tell me a fact and I'll learn. Tell me a truth and I'll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever” [

1]. A story always tells a little more than just the story line. It leaves a reason for the listener to think and re-think, to try to understand better the people and the world, to share experience and knowledge, to scare and challenge, to plan and dream. A story is an anthropological vehicle from the teller to the listener to transmit a message or a lesson [

2]. According to [

3], a story is any connected narrative, in prose or poetry or a mixture of the two, that has one or more characters involved in a plot with some action and at least a partial resolution. It may or may not have fictional aspects. The use of storytelling can create a dramatic narrative that not only stirs the emotions but also adds to their cognitive power, making valuable contributions to moral learning [

4].

Storytelling is increasingly being used in educating and communicating for sustainability “to simultaneously convey information, explain problems and evoke emotions” [

5]. It is a powerful pedagogical tool in the classroom to either represent the reality or create an imaginary situation. The story stipulates with people (who), facts and situation (what), place (where), reason with consequences and resolution (why). Through the story and the teacher-learner interaction, the audience can smoothly relate a current situation, its facts, consequences and resolution while a moral lesson is transmitted. With the idea of sustainability often being traced to traditional cultures, storytelling can also build a bridge between the past and the future, combining different bodies of knowledge, values and practices – local and global, indigenous and scientific. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) specifically highlights the potential of storytelling for transformative engagement [

6], encouraging reflective discussions which deepen students’ understanding and promote critical thinking [

7]. Storytelling can have a transformative pedagogical role at all levels of education for sustainability – from kindergarten to university.

Notwithstanding this, storytelling is often overshadowed by other pedagogical tools [

7] and is not properly integrated in the classroom’s learning process. This could be a missed opportunity to link wisdom from the past with the search of solutions for today and tomorrow, particularly given the complex and multifaceted nature of sustainability that may be difficult to communicate to younger people. While storytelling is being rediscovered for teaching sustainability, the art is as old as time and has been used through history to influence human views and experience [

8]. It has become a way to counteract a content dominated by facts and figures to bring emotions and values [

8].

Nowhere is storytelling as important as at the beginner’s stage of formal education where it fosters imagination, creative thinking and cognitive skills as well as develops cultural and moral understanding [

9]. The stories, fables, myths, legends and songs used in storytelling come not only from the literature but also originally from folklore. Every culture has its own stories that explain natural phenomena, describe human behaviour, answer difficult questions, nurture values and develop emotional connections. They can be communicated orally and through the written word. Such stories are vivid and entertaining, they symbolise cultural beliefs and contain fundamental human truths by which people have lived for centuries [

10]. They are also brief and although they may contain elements of fantasy, they always hold a resolution or a moral learning about the problem.

Teachers as the storytellers play an essential role in this process through their knowledge and approach but also through the inter-personal relationships of trust and respect that facilitate communication in the classroom. Children are usually quick to separate fact from fantasy and are in a position to grasp the underlying message of the story [

11]. They can sort out the good from the evil and identify with the positive characters. This paper examines the power of storytelling within the context of primary education in Bangladesh with the aim to facilitate the development of sustainability values that can withstand the test of time and any influences contributing towards making our world untenable. The main argument of the study is that folklore-based storytelling can be a powerful tool in primary education in Bangladesh, a country that has embraced the achievement of the global Sustainable Development Goals [

12].

Given the age of the students and the formative importance of primary education, the emphasis of the study is on the development of moral and ethical reasoning related to sustainability. While morality and ethics are closely related, there are some differences. Ethics describes what is acceptable within certain social settings or a community while morality relates to a person’s individual judgement of what is good or bad [

13]. From this point of view, it is important to use ethical stories to teach moral lessons in primary schools.

3. Storytelling in the Primary School’s Classroom

Regarding the impact of oral storytelling on children’s self-concept, [

15,

16] found that it exposed children to “long-standing archetypal models” [

16] that engaged the imagination, stimulated sympathetic responses, and helped children to process their social experiences at school. Stories play a significant role in shaping children’s psychological development and have a pedagogical value in the classroom to develop critical reading skills [

17]. Valuable research and evidence on storytelling from around the world show that this ancient art can be blended with contemporary needs and tools to improve children’s development and skills 18-20], including values acquisition [

21], moral lessons [

22], development of identity and empathy [

23]. Moreover, research shows that the most engaging stories used in the classroom are those to which children could relate [

24].

Stories or folktales are considered a source of entertainment, able to create interest and excitement in children. Fables in particular present moral truths while certain characters can represent powerful symbols in themselves of the good and bad or weak and strong [

25,

26]. As one of the major forms of folk literature, folktales can help in evaluating the intrinsic relationship of humans with the natural world and can assist in developing a nature consciousness and responsibility towards Mother Earth.

However, research on storytelling in Bangladesh’s educational system, particularly the use of this educational tool in primary level education, has been scarce. On the other hand, Bangladesh is rich with folklore-based stories with traditional or folk values considered to be harnessing the principles of sustainability [

10]. In the past, children were entertained and instructed with folktales. This tradition has been overtaken by the written culture. Some writers have tried to preserve the oral tradition of Bangladesh in books aimed for children with the intention of instructing and entertaining them. The folk stories’ succinctness, action, fantasy elements, characters to whom children can relate combined with happy endings make them appealing to young listeners and help them in developing a sense of morality [

27]. They guide children in distinguishing the good and the evil in the world and encourage them to start identifying with the good.

The stories in the ‘Thakur Maa’r Jhuli’ by the legendary Sri Dakhhinaranjan Mitra Majumder published in 1907 [

28], have been inspiring the children of Bangladesh in the past. Many remember the famous story of the Rabbit and the Tiger, where the Rabbit could make a way to save its life and punish the Tiger only by the prompt intelligence, says that the Rabbit could do so because it “regularly eats vegetables”. Thus the message given is that having vegetables regularly makes you intelligent. The stories of the Prince and the Demons describe how the Prince fights the demons with massive courage and crosses thousands of hurdles to bring back the life the Princess or for other greater causes. They teach children to be confident, courageous and ready for sacrifices to reach the goal and to bring good to the journey of life.

Other Bengali folk stories have also survived the test of time. For example, the word “Bhombal Dass” [

29] taken from a folktale, is stipulated in our day-to-day life to give someone a name who is considered a fool. The story of “Tetan Buri and Boka Buri” (The Two Old Women) – a Bengali folk tale [

30] graciously inspires young children to share their belongings with each other. The story “takar apod” from the collection of Shukumar Roy’s [

31] stories can help realise that money cannot buy peace and happiness, and teach how to be happy with less with the famous tale “shukhi manusher golpo” (story of a happy man).

Although these folk stories are still alive in Bangladeshi culture, many children, especially those born and raised in the urban areas of the country, are not in touch with the oral traditions of their ancestors. In their city life, they are rarely exposed to the richness of the Bengali folklore. Using storytelling in the classroom can help establishing the connections between present-day life and the cultural heritage of the country. This however is not as simple as reading or telling a story as many folk stories also contain outdated ideas, such as recognizing the gender of the baby from the way the pregnant mother looks [

32], or patriarchal attitudes considered now misogynist, such as kings with multiple wives or male dominance [

33]. The art of using this precious folk material is to slightly tweak the story while preserving its goodness and conserving the right attitudes and honourable behaviours [

33]. As the award-winning author, educator, poet, storyteller and translator Sutapa Basu [

33], explains, if you bring the enchanted realms of the folk stories to the classroom, somewhere in the process they will change the way children view the world.

The intertwined aspects of sustainability are often present in folk stories. Developing a conceptual framework is essential for bringing any story into the primary school’s classroom as a tool for values education encouraging sustainability [

34]. For example, nature and the natural environment can be represented in different ways in folklore with negative (e.g. being frightening) or positive (e.g. offering shelter or beauty) messages to humans and other species [

35]. Stories are rememberable and entertaining [

36]; they develop the landscapes of action and consciousness [

37]; in the form of fairy-tale can improve language, creativity and also the self-expression of the students in the classroom [

38]. In addition to the development of basic skills, such as listening, speaking and reading, stories help young children’s emergent literacy outcomes [

39], analytical capacities [

40], make them more resilient and encourage their ability to make meaning and understand the world [

41] . It is this power of stories that needs to be brought out when educating for sustainability.

4. Conceptual Framework for Analysing Stories

With storytelling being a useful tool in primary education, the selection of stories and their suitability become a major decision for teachers to make. The conceptual framework for analysing the suitability for stories in teaching sustainability used in this study is synthesised from a constructivist perspective as a bridge between theory and practice [

42] based on the theoretical and empirical literature on storytelling. Scaffolding [

43] is used in this study as a framework for examining how stories in the classroom may facilitate moral or ethical reasoning. According to the constructivist perspective, the teacher does not directly present the knowledge but guides the students in the learning process to develop this knowledge [

44]. Scaffolding is a metaphor to describe the educational process similar to putting support in place in the construction of a building which is removed upon completion. The concept was first introduced in education by Wood, Bruner and Ross [

45] in the 1970s and since has been frequently used to explain the role of the teacher in the learning process from kindergarten to university [

46]. According to [

47], “educators engage in scaffolding by providing the necessary level and type of support that is well-timed to children’s needs”. In this way, they improve student engagement and motivation to achieve better cognitive outcomes [

46]. Supported by teachers, children can use storytelling as a scaffolding process in making meaning and comprehending the complexities of the surrounding environment.

In the literature, there is no agreed way how exactly scaffolding should be used [

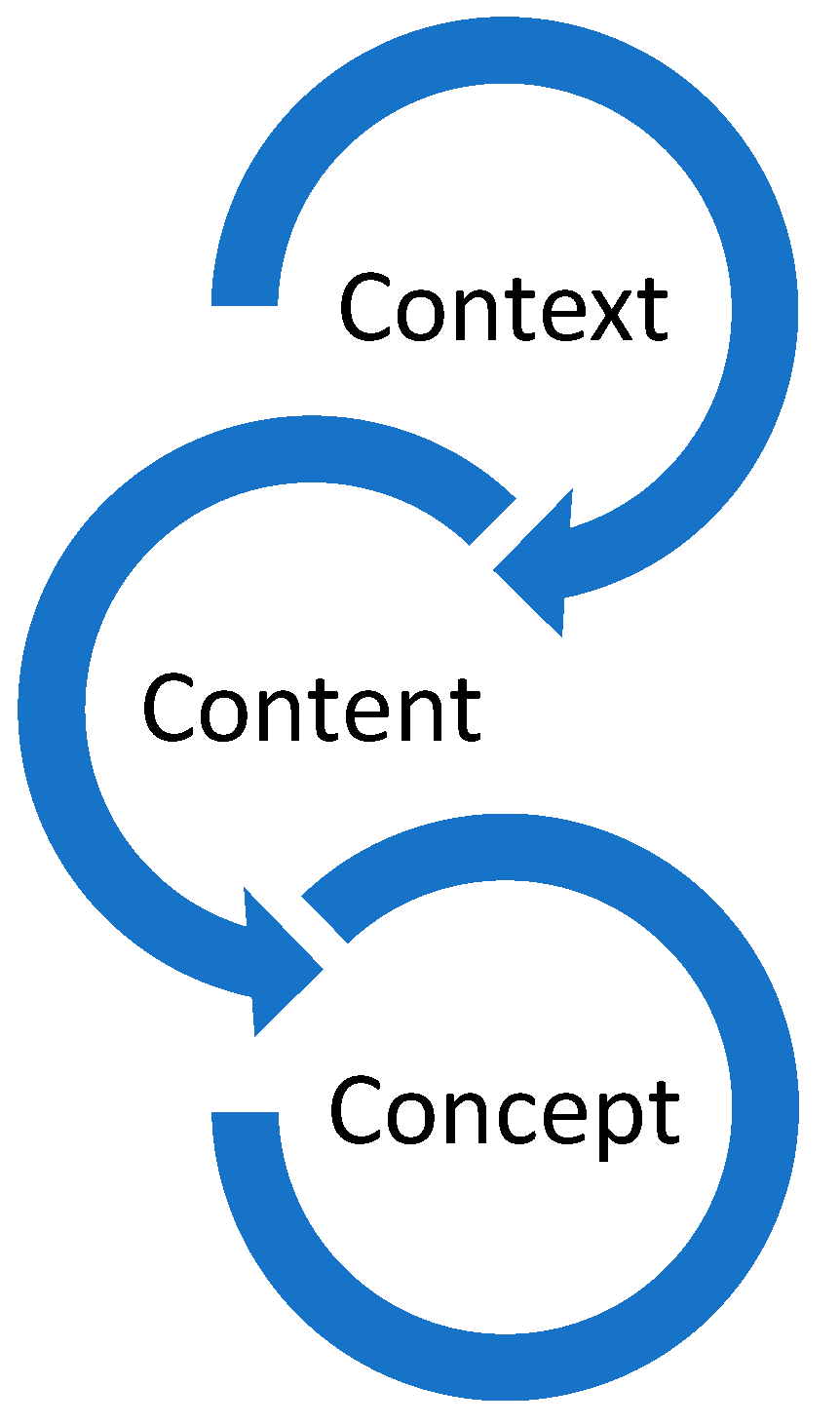

48] and different approaches have been put forward. The 3C approach – Context, Content, Concept [

49], is used as scaffolding to analyse the suitability of folk stories to teach sustainability (see

Figure 1). It allows the teacher/storyteller to determine the compatibility of the story with a sustainability perspective. The context represents the circumstances – theoretical or real-life, within which sustainability is introduced. This could describe a school within a particular community with a certain demographic and socio-cultural profile. Content refers to the matter of the story – what happened, including characters, their actions and consequences. The concept is the larger theoretical or practical sustainability issue which the story and its moral help explain.

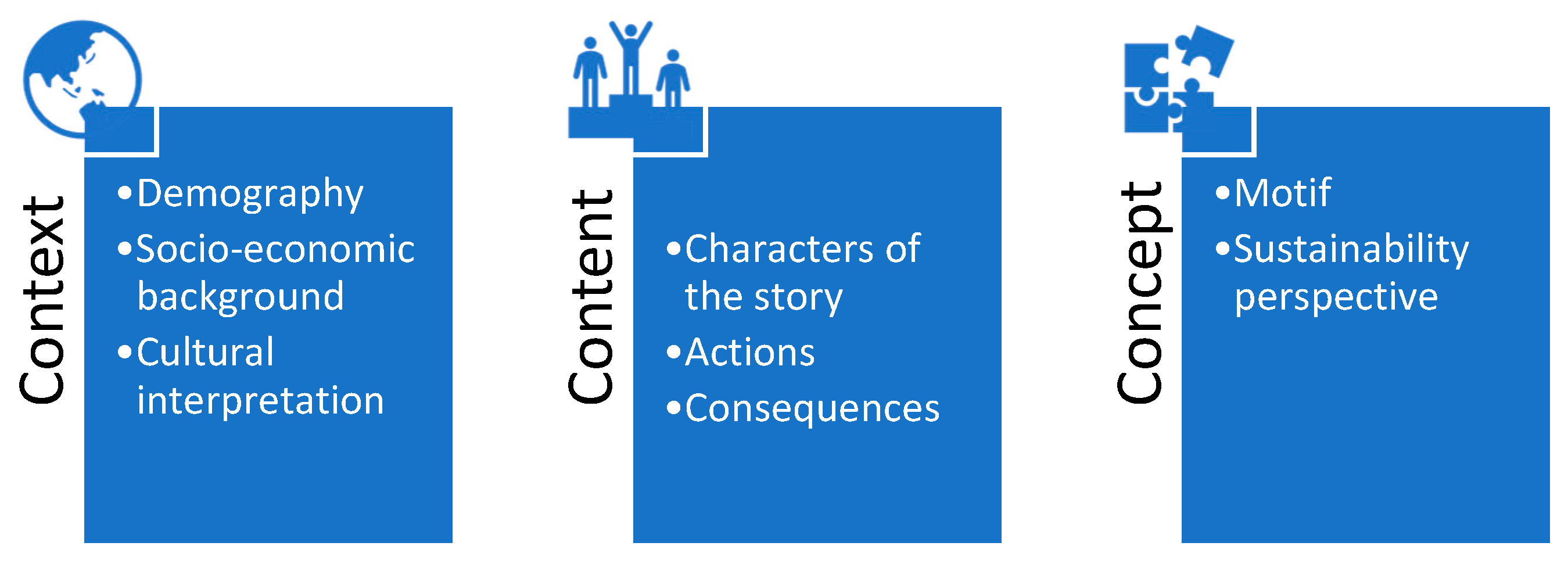

Figure 2 shows the application of the 3C approach attempts the link between the approach and mapping to create a comprehensive understanding of the sustainability perspective.

Figure 1 portrays the 3C approach (Concept, Content, Context) that will help the teacher/storyteller to predominantly determine the compatibility of the story with the sustainability perspective.

Figure 2 attempts the link between the approach and mapping to create a comprehensive understanding of the sustainability perspective. Pellowski [

3] defines a story as any connected narrative, in prose or poetry or a mixture of the two that has one or more characters involved in a plot with some action and at least a partial resolution. It may or may not have fictional aspects. Given the rationale and framework for the study, the research sought to outline the approach to analyse two commonly recognized stories from Bengali folk tale and mapping with the major aspects of sustainability (social, economic and environmental) to investigate how stories can influence children on building pro-sustainability attitude.

The selected stories can function as a linguistic resource in pragmatic interaction between the teacher and students [

34]. This process can create the web of interactions in the classroom and give the teacher an opportunity to bring sustainability into the conversation. Specifically (see

Figure 2), the context of the folk story will determine: the demographic understanding of the platform of the story (e.g. folks and place), the socio-economic rationale of the folks and the cultural interpretation of the folks where the story belongs. The content of the story will determine: the characters of the story, actions taken by the characters and consequences revealed from the actions. Finally, the concept of the story will determine: the ultimate motif of the story and the sustainability perspective carried out by the motif. This approach is used below for two commonly recognised Bengali folk stories after the process of their selection is explained.

5. Two Examples of Folklore-Based Stories

Two stories from Bengali childlore are selected for story telling in the classroom. According to Dundes [

50], folklore reflects the past and the present, but they it can be used in primary education is to also shape the future. Fairy tales are particularly appropriate as they are simpler and can be used as exemplum combining animal tales or fables and anecdotes, carrying a unique lesson or moral. They can illustrate certain moral points as is the case with Bengali folk stories, such as Lalkamal-Nilkamal, Byangoma-Byangomi or Duo rani – Suo rani. An objective of such stories is to help stimulate children’s imagination and relate the moral with their own lives and circumstances. They create avenues for thinking and questioning as well as adopting certain values.

There is no prescribed method that a storyteller or the teacher must follow to select and prepare a story for telling [

34]; each storyteller finds a method that works best for them. Mundy-Taylor [

34] emphasises the importance of devoting care and time to the selection of stories as the success of any storytelling relies on the acceptance and enjoyment of the stories by both, the teller and the listener. In our case, stories should originate from folklore and need to be published with their content appropriate for the 5-11 years age group. They should play with the themes of good and evil in order to provide a value judgment. Another consideration is the teacher’s personal knowledge and experience to be able to convey the context, content and concept of the story.

Any religious biasness or cultural taboos should be avoided or explained. The two selected stories, respectively from “Grandmother’s Bag of Tales” (Story 1: Shukhu and Dukhu) [

52] and “The Clever Jackal and the Foolish Jackal” (Story 2: Jackal, The Judge) are presented in

Box 1. The full story once translated by Sutapa Basu (2021) [

51] as Princesses, Monsters, and Magical Creatures, from the original book of 'Thakur Ma'r Jhuli' (Grandmother's bag of tales) by the Author Dakshinaranjan Mitra, 1907 [

52]. This paper rendered the full translation. It is very difficult to translate the texture of a language and the interlacing the words [

53] but care has been taken to adhere as closely to the original as possible.

Box 1. The two folklore-based stories.

Story 1: Shukhu and Dukhu

A weaver sadly passed away leaving behind two married daughters. The older daughter and her husband took all the wealth, the better places of the house while throwing the other pair into the dark, dingy chambers behind the house with no resources for surviving. The younger daughter Dukhu spins a little cotton and makes a towel or tablecloths from it, sells them in the market which is hardly enough for a meal for the two of them.

One day, Dukhu sits and looks after damp cotton dry in the sunlight. Suddenly, a mischievous little breeze swooped the cotton balls leaving Dukhu crying. Mother Wind, who was passing the crying Dukhu, said: 'Don't cry, dear Dukhu. Come with me. I will get your cotton back for you'. Wiping off the tears, Dukhu rushed after Mother Wind and soon was called out by a cow. 'Dukhu, Dukhu! Where are you going? My cowherd has forgotten to sweep my shed. Will you please do it for me?' The soft and kind-hearted Dukhu couldn't brush off the request and hurriedly swept out the cowshed, put fresh hay and water and started running again behind Mother Wind. Soon a banana tree called out: 'Dukhu! O Dukhu! Weeds are choking my roots, please pull them out for me.' Dukhu tugged out the weeds from the roots of the banana tree and rushed after Mother Wind. Soon she was called out again by a banyan tree to sweep away dry leaves from its branches and by a horse to give him a few handfuls of grass. Dukhu couldn't avoid either of them being stressed for her own agony. So, Dukhu swept the dry leaves, making the turf under the banyan tree neat and clean, pulled out clumps of green grass and placed them in front of the horse before she continued running behind Mother Wind until they came upon a silver-white mansion. Dukhu passed large clean halls, gleaming courtyards and sparkling windows until she reached a wide staircase where an old woman was sitting and spinning yarn on a wheel and weaving it so quickly on a loom that a pair of saris flowed out before Dukhu could blink. This enchanting old woman was nobody else but the Moon Lady or the Granny of the Moon. Heavily nervous Dukhu came close to Granny, bowed to her and pledged to return the cotton. Otherwise, she and her husband had to starve as these cottons were the only source of the little food they earned. With a honey-sweet voice and heart full of kindness, the Granny said: 'Oh my good child, bless you! You have come such a long way. Why don't you bathe, eat some lunch and rest, first? In the next chamber you will find a towel, some scented oil and soap. There are also saris for you to choose from. You can bathe in the pond behind the mansion. Once you feel fresh, go to the other chamber and have lunch. Then I will give your cotton back.'

Dukhu found the next chamber full of towels of all kinds, saris of silk, cotton, muslin in all colours, shelves full of oil and soaps. Despite all the fancy items, she only took a simple sari, a little towel, a few drops of oil and a little soap. The moment Dukhu dipped her head into the pond, she become more beautiful with long-thick hair, soft peach skin, large eyes and red lips. She found all covered by gold jewelry around her body after the second dip and wrapped with the silk sari. After finishing the bathe, Dukhu found a hall full of feast, but choose to eat very little. The Moon Lady then asked Dukhu to pick up her cotton casket from the next chamber. Out of all big caskets, Dukhu picked the smallest as she knew she didn't own any big casket. Amazed by the honesty of this poor girl, the Granny bestowed her blessings to Dukhu who happily started her way back home. Here came the horse, called her out and offered her his pakshiraj (little pony), the banyan tree gave her a large jar filled with gold coins, the banana tree gave her a large bunch of golden bananas and finally the cow gave her lucky calf to Dukhu.

Seeing her coming back home, her husband streamed down with joy and with surprise revealing his wife has become more beautiful with all the jewels and gifts. After hearing everything that has happened, Dukhu’s husband delightfully went to the older sister’s door, offered a good share of all jewels and gifts. Scowling, frowning, making ugly faces, Shukhu’s husband refused to take anything from them and slammed the door on his face. On the other hand, a beautiful baby came out from the casket and gave love and joy to the sweet and kind Dukhu. The lucky cow gave them bucketsful of creamy milk, they rode the Pakshiraj everywhere. Dukhu and her husband then lived in peace and comfort.

Greedy Shukhu and her husband couldn’t resist but stagged the same plot of drying cotton piles in the sunlight. Shukhu’s husband went to bathe leaving Shukhu with the cottons. Soon the wind blew and lifted Shukhu’s cotton pile. Wasting no time, Shukhu started following Mother Wind and she encountered the banana tree, banyan and the horse the same way Dukhu was called out. But the shellfish Shukhu paid no attention to them. She even didn’t show any respect to the Moon Lady when she arrived in the same mansion and rather yelled at her to give out the gifts. The Moon Lady felt intimidated and softly asked her the same she did with Dukhu.

Shukhu hurried into the next chamber, picked the best towel and sari for her to rush to the pond. She recalled Dukhu’s steps in the first dip gave her beauty, the second dip gave her ornaments. The greedy Shukhu dipped her head trice and was horrified looking at the mirror. Her face had swollen into a black balloon, ugly blisters had broken out on her skin. The Moon Lady calmed her that what is done can’t be undone, she should not have taken dip three times. The Moon Lady then asked her to have food and choose a casket from the next chamber. The greedy Shukhu ate full to the mouth and picked the largest casket. Bidding no farewell wish or greetings, she left the Moon Lady, showing no respect. On her way, she begged for help and everyone refused. The horse kicked her, the banyan dropped a thick branch on her, and the banana tree dropped a bunch of bananas on her back, the cow lowered its head to stab her. Stumbling and staggering, panting and gasping, Shukhu reached home. The devastated husband and wife than waited for the night when they were expecting a baby would come out from the casket and their misery would be over. Shukhu’s husband found out that Shukhu was gobbled by a huge python instead who was inside the casket. Sobbing and howling, Shukhu’s husband battered his head on the wall until he died.’

Story 2: Jackal, The Judge

The bravest amongst all beasts in the jungle, a tiger was trapped captive by a group of poachers. He was feeling tired and helpless after all his attempts to get out of the cage. A moment later the tiger requested a gentleman who was passing by, to open the locker for him to go out and drink some water from the riv. He promised to come back. ‘You will break my neck and eat me if I open it, I don’t trust you’, said the passer-by with fear and doubt. The tiger than made a gentleman’s promise and his heartfelt pled melted the traveller’s heart, he freed the tiger from the cage.

The nature of the wicked tiger said: ’I will eat you before having water. The traveller realised he had brought his own danger but there will be no use of force here, rather he was thinking of using his intelligence. ‘I know you will eat me, but before that, the opinion of four juries should be taken’, trickily said the man.

A moment later, they approached a gigantic banyan tree. The traveller asked the banyan tree and said this tiger was imprisoned in the cage of hunters. I freed him up at his request. Now he wants to eat me. How can he do so? The banyan tree sighs: ‘I stand in the sun and give shade to people; they sleep comfortably under me. Then they broke my branches, lit a fire at my base and cooked rice. Human is very ungrateful. Thus, this man should be fed.

‘Get ready for death’, said the proud tiger. ‘We are yet to ask three more juries before you eat me’, said the frightened man, looking for the second jury.

After going some distance, they met a dog. The dog heard everything and said, when I had strength, I used to guard the master's house without sleeping all night. Once I saved the life of the master's little son by lifting him out of the water. Now I'm old, I can't work like I used to. The master stops my food, chases me away when he sees me. Human is ungrateful and this man should go into the tiger's belly. Death was coming closer and then they come across a cow.

The traveller said to the cow, "I have done a favour to this tiger by freeing him from the hunter's cage." Now he wants to eat me. Is this the result of helping anyone? Hearing all this, the cow said, in my youth, I ploughed my master's field, pulled cartloads of goods, gave birth to five calves, the master fed my milk to all his children. Now I'm old, can't give milk, can't pull a car. The master has stopped feeding me, will sell me to the butchers. Human is ungrateful and this man deserves to be in tiger's belly.

The devastated traveller was looking for the last jury, the last hope and a jackal was passing by. After hearing everything, the jackal understood that the traveller could not be saved if he did not have a little wisdom. The jackal pretended not to understand the matter and said: "I can't make a proper judgment without seeing with my own eyes how the matter happened." The overjoyed tiger explicitly demonstrated the whole story: ‘I was sitting inside the cage when this man was passing by the back of the cage’.

‘How can the man open the door from behind the cage?”, pretending not to be understood, the jackal said with wonder. The tiger became impatient and jumped into the cage and said: ‘I was here.’

The jackal said: “What was the condition of the door? “

The tiger said: “The door was closed.”

The jackal said to the passer-by: ‘Close the door’ and the man closed the door without delay.

The jackal said to the tiger: ‘You are ungrateful. The man opened the cage door at your request and set you free as he felt pity of your suffering, and you wanted to eat him instead. Never harm those who make you a favour or benefit you.

6. Discussion

Both stories comply with the three criteria identified by Buell [

54] for evaluating a literary text for its sustainability educational value, namely: (i) The non-human dimension is an actual presence in the text and not merely a façade implying that the human and non-human worlds are integrated; (ii) The human interest is not privileged over everything else; and (iii) Humans are accountable to the environment and any actions they perform that damages the ecosystem [

54]. The moral messages conveyed in the two tales help instil an ethics in the mind of the young listeners that would help them grow as mature adults that are caring, considerate, responsible in consumption and free of greed. They encourage joy and satisfaction with life that can persist no matter how much people age. The pedagogical use of the stories however needs to be apprehended within the 3C scaffolding approach.

3C approach: Context

The analysis of each story begins by setting it within the respective geographical, socio-economic and cultural context, incorporating religious and other social aspects into its narrative [

55], while keeping the core objectives unchanged. A teacher has some freedom inside the classroom to make any adjustments of the content, background and other elements of the story as needed, taking into consideration the socio-economic status of the children, achievable competences and cultural, including religious characteristics. For example, when the story 'Shukhu and Dukhu' was originally written in 1907, having polygamy was culturally accepted and the main characters were the two wives and daughters of the weaver. However, in the modern context having two wives is not legally acceptable. Hence, these characters are replaced by two daughters and their husbands. The teacher (as everybody else) should have the freedom to make reasonable adjustments when narrating folk stories to the children while preserving the moral message. As Castle explains [

56], folk tales are continuously changing and have always done so, but they also exist in a story time where magic is possible. This magic brings hope and conveys the confidence in children that if they do the right thing, they will live in a beautiful world. Such values and attitude are extremely important for sustainability.

When a story is presented to children through a contextual agent, such as the teacher, its acceptance will increase, and the desired response or result will be obtained. Although stories are being translated and analysed from a research point of view, in a practical application it will be easier for a teacher to present his/her own re-arranged plot, if text is converted into the context. In fact, the story’s text is translatable while the context is not [

54] and this is essential in the scaffolding approach.

The story ‘Shukhu and Dukhu’ portrays the simplicity of rural Bengal as many other Bengali stories have done. Thy transmit cultural values of simplicity and living within one’s own accord. It also reveals that nature rewards or punishes humankind based on how humans treat the land, air, water or any other living beings that exist on this planet. The younger daughter-husband duo merely managed their ends meet, yet they were humble, thankful for what they had and were kind to other beings. Dukhu’s own misery couldn’t stop her from being kind to the animals seeking help on her way. Shukhu on the other hand is greedy and aspires for more possessions and wealth without due consideration of other living beings. This story conveys a picture of how rural people in Bangladesh find happiness in simple living and how greedless life brings ultimate joy, making the story relevant with an educational focus on sustainability. Unrestricted consumption and greed lead to an ugly, unhappy existence and ultimately, death. The story’s focus is intended to explore the moral understanding of the children in the classroom. It is presented as a metaphor of a naturalistic view of two sides of society where one group is overall more successful in finding peace and joy.

The second story begins by illustrating how poachers are hunting the tigers for their own satisfaction. Its plot can be used to explain to children how animal poaching is causing extinction of different species and is impacting biodiversity. The traveller was asking to take the opinion of four people before making a final decision and this represents how the justice system works as swell as how to give importance to other people’s opinion in social life. Furthermore, the story instigates young minds to keep patience in danger and still be tactful in the decision-making process.

3C approach: Content

Archetypal characters are pre-eminent in folk stories and their function is to harness a child’s understanding by establishing clear connections between the particular and the universal. In both stories, the characters of the humans and the animals are archetypal, but they are used to carry morally simplistic meanings. Giving non-human objects, such as plants and animals, a voice is intriguing. In many tales, horses and plants speak to people, warning them of dangers and about remaining loyal. This also provides such objects with significant importance. Without them, the traveller or Dukhu would not have made the journey. Dukhu was rewarded by every non-human character in the story for her kindness toward them while Shukhu received the opposite for her cruelty and selfishness. On the other hand, the man’s life was saved by the wisdom and spontaneous intelligence of the fox. For a child, this teaches it to take care of inanimate objects and other non-human living beings in the same way that they would care for a human.

It is conventionally acknowledged that good teachers are good storytellers [

57], but analysis of how stories function pedagogically lags behind this recognition. Close textual analysis of the content and process of storytelling is needed to grasp the full importance of teachers' storytelling [

58]. As the stories are mostly exempla, with the teacher and students using them to convey opinions and value judgements, they give an opportunity to create an avenue where the learner will be able to relate the content – characters, equipment, any specific event of the story, consequences etc., through the value inherent in the content, with real-life experience related to sustainability.

In most folktales, as in the two used here, a lesson of what happens if the human is grateful for the animal's aid and the consequences for being ungrateful, is also communicated. Children with an emotional attachment to non-human beings are likely to become more friendly towards the natural environment in adulthood. The beliefs, values and ways of life that have evolved from living close to nature, naturally have a stimulating effect on people in developing environmental ethics and creating ecological values and pro-environmental emotions.

3C approach: Concept

Moral principles are considered the fundamental gateway to achieving sustainability [

59]. According to Albert Einstein: “The most important human endeavour is the striving for morality in our actions. Our inner balance and even our very existence depend on it. Only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life” [in 60]. The reason for using folk stories for the purposes of moral education is they are archetypes, comprehensible and the values are accessible to be explored. Each story should represent an exemplum by being a ‘moral tale’. In each exemplum, a problematic incident is presented and then interpreted with children having the opportunity to comment on the behaviour of the characters involved [

61]. The students and teacher share the storytelling process using exchanges to bring out the moral values. These stories possess interrelated evaluative and social functions for the listener [

62] who has the ability to create a relational construct, not just based upon the characters in the story embedded in relationships but through the relationship of the listener to the characters themselves. Likewise, stories provide commentary upon significant life experiences and can be understood as a means of “constructing and seeing one’s self in relation to others, appreciating difference, and evaluating ourselves” in relation to others [

62].

The two stories offer the children a number of possibilities as to the intended implicit moral and values: if you are kind to nature, you will be rewarded; no matter how poor you are, you shouldn’t be greedy and live the simplest possible life even when you are offered abundant wealth. Children were given the example of a bad ethical decision and the consequences of the greedy pair who were unkind to the creatures seeking help. This will create an avenue for children to image the contribution of a tree, a cow or a dog in their everyday lives and how they should be treated in return. All living, non-living, human, non-human beings are crucial for a joyful co-existence on our planet and hence, for sustainability. Children are evidently capable of recognising a wide variety of good and bad ethical behaviours within the context of one simple story whose moral will persist in the primary school classroom.

The emergent themes from this research explore how the process of storytelling in the classroom can be used to scaffold moral/ethical deliberations. First, the storytelling process and facilitation offered complexity and multi-dimensionality to the discussion of ethical issues because students were asked to place themselves into the context of the story. Students demonstrated their own interpretations of the context as it applied to their real lives. It cannot be generalized how students will interpret and relate to individual stories because student interpretations and understandings of the morals were drawn from their own experiences. While children may be able to reason abstractly about the right thing to do, this does not necessarily equate to the ability to handle moral situations that arise in their daily lives. The narrative approach for moral education serves to create a situation in which the individual student reasons through the process of reflecting upon oneself in the place of a character that one has thought of metaphorically [

63].

3C approach: Scaffolding

A folkloristic approach [

58] demonstrates how a teacher can bring up the actual topic by using stories along with the textual content, for emphasising sustainability with the content of the story. Another aspect of a folkloristic approach is that just as different genres of folklore have been transmitted orally from one generation to another, through this approach a teacher can first introduce children to a pro-sustainability attitude which will persist through their education. The first stage brings the textbook story of the past into the present situation by removing the boundaries of time and space, and then draws the student in the present context into relevant sustainability behaviour. Teachers have limited authority in the classroom: they can only speak from their own experience, and their understanding of the experiences of others is filtered through their own experiences. Therefore, in the second part, the teacher narrates any story or tale and not only interprets the textual content, but brings together personal and local knowledge with professional, academic, nationalised knowledge of sustainability.

If the first of these exercises enables children to deconstruct the values embedded in the narrative, the latter allows them to begin to reconstruct the moral of the story in the light of the ethical sense they make of the characters’ actions. However, both the content and context used allow teachers to glean new insights into the children’s complex ethical dilemmas and how they reason through them. This is a benefit from the use of storytelling in the classroom. The complexity inherent in storytelling allows for interpretation. Students interpret their own meanings—those that are most relevant to their personal experience and most closely related to their own ethical deliberations. This interpretation by the students then provides insights for teachers to better understand how the students apply ethical reasoning in their everyday experience.

Education is considered the opportunity for change towards sustainability through values development. The teacher should be able to reach out to the children's hearts with sustainability messages and tell them they need to be gentle on earth, modest in living and kind to others.