Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

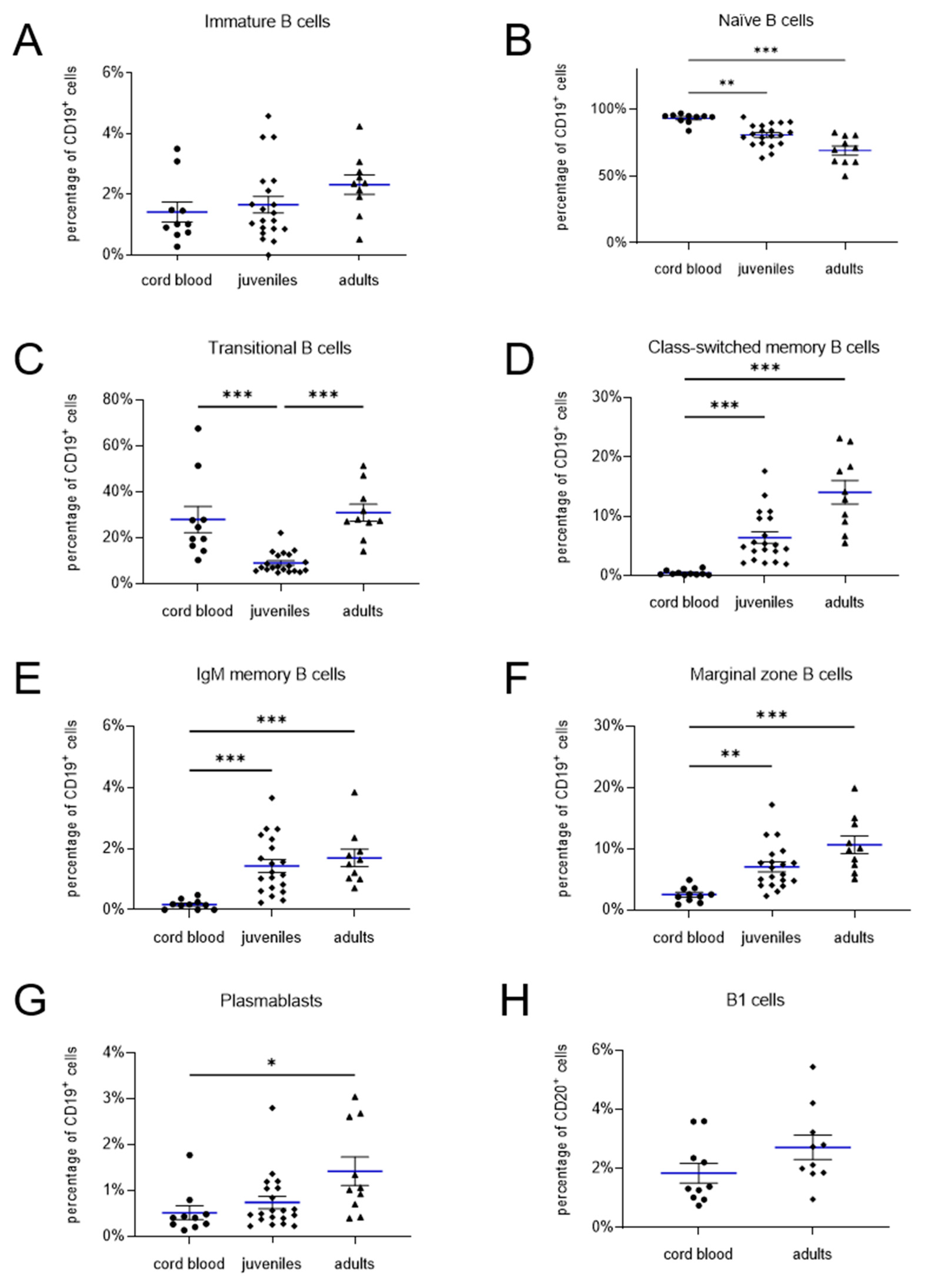

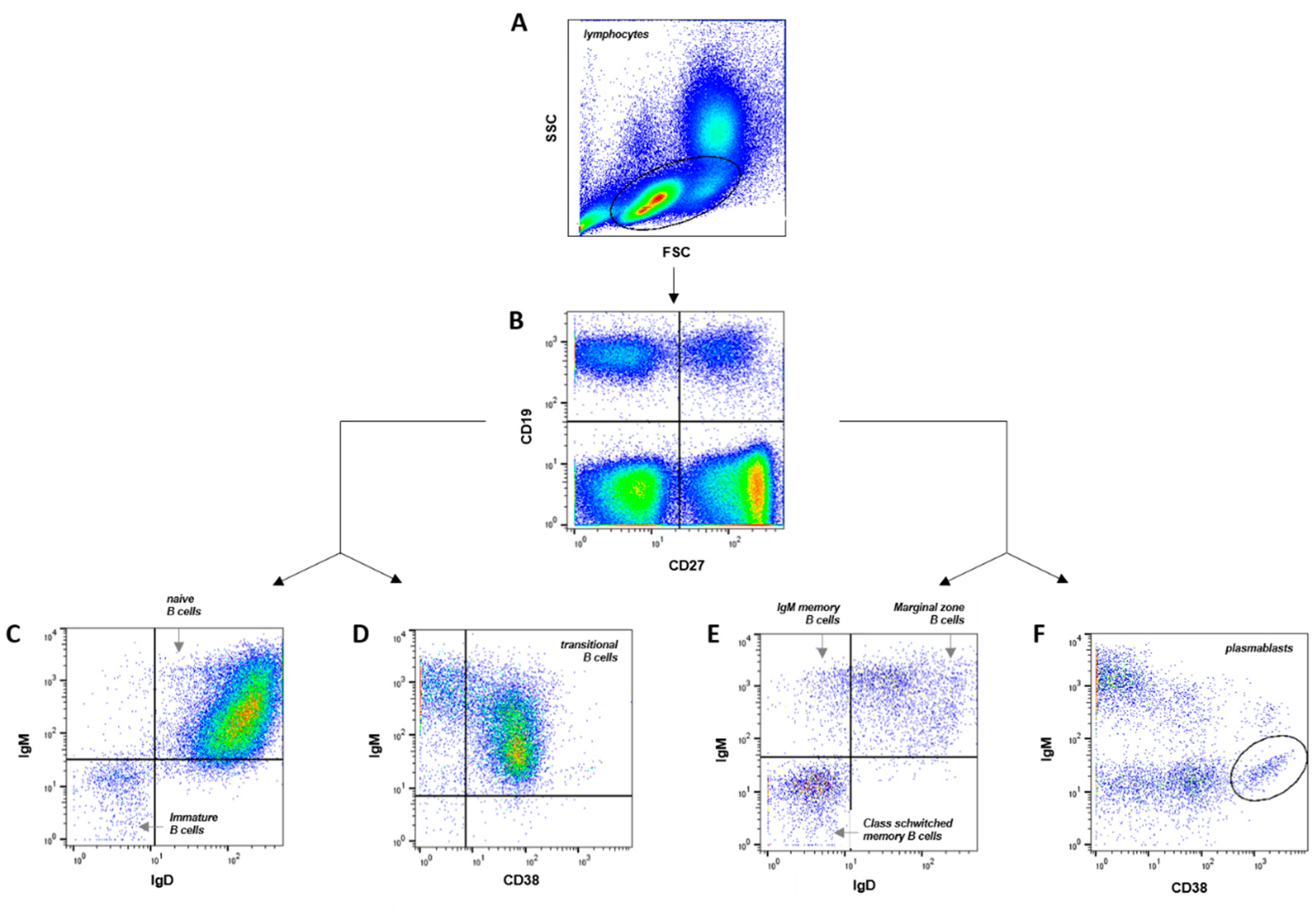

2.1. Phenotypic characterization of memory B cell subsets in healthy newborns, juveniles and adults

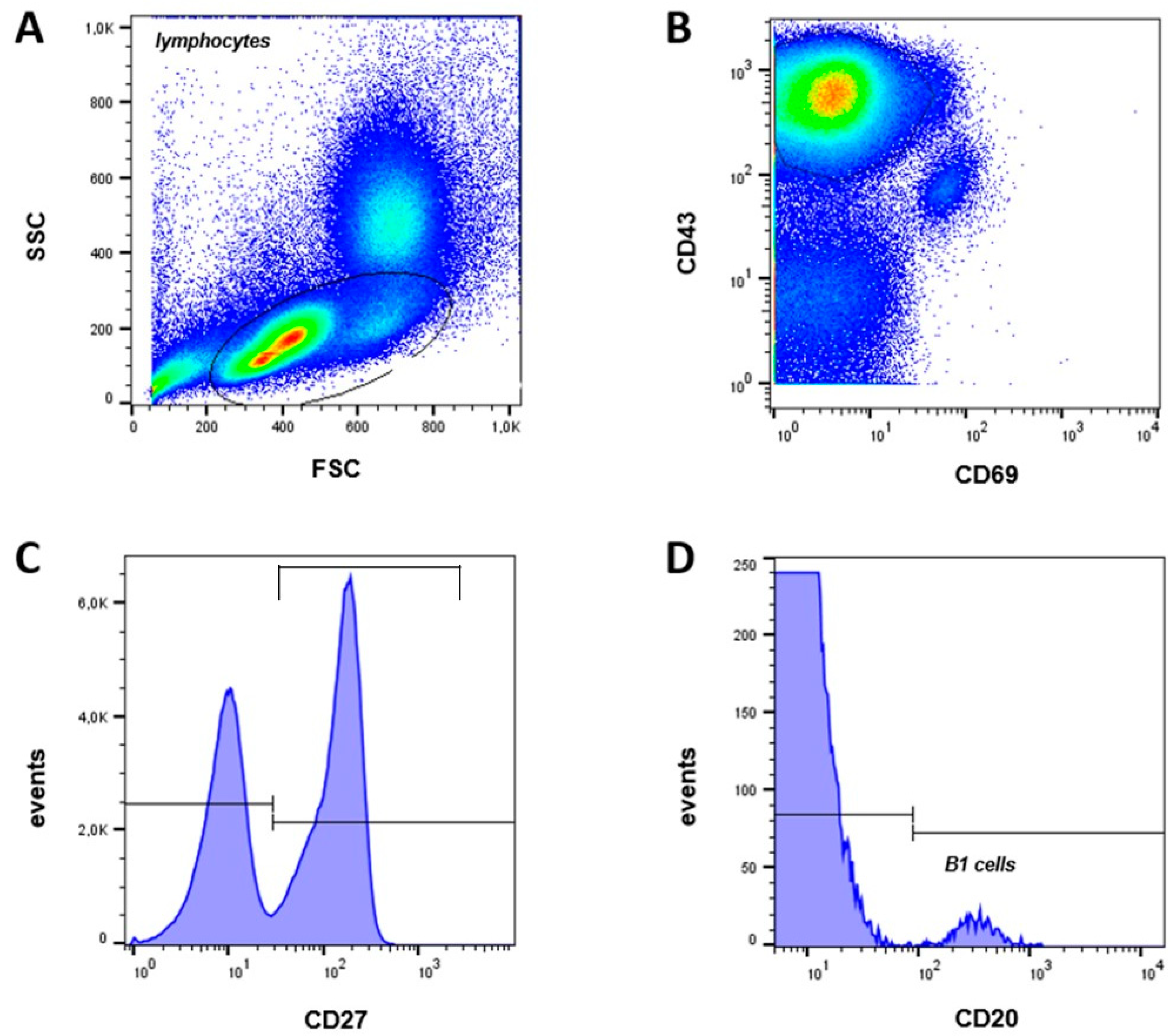

2.2. B1 cells in cord blood and peripheral blood of adults

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient samples

4.2. Cell isolation and B cell enrichment

4.3. Flow cytometry

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeBien, T.W.; Tedder, T.F. B lymphocytes: how they develop and function. Blood 2008, 112, 1570–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comans-Bitter, W.M.; de Groot, R.; van den Beemd, R.; Neijens, H.J.; Hop, W.C.; Groeneveld, K.; Hooijkaas, H.; van Dongen, J.J. Immunophenotyping of blood lymphocytes in childhood. Reference values for lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr 1997, 130, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufe, A.; Peters, M. Unterschiede zwischen kindlichem und erwachsenem Immunsystem. Haut (2013).

- Cerutti, A.; Cols, M.; Puga, I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrón-Ruíz, L.; López-Herrera, G.; Ávalos-Martínez, C.E.; Valenzuela-Ponce, C.; Ramírez-SanJuan, E.; Santoyo-Sánchez, G.; Mújica Guzmán, F.; Espinosa-Rosales, F.J.; Santos-Argumedo, L. Variations of B cell subpopulations in peripheral blood of healthy Mexican population according to age: Relevance for diagnosis of primary immunodeficiencies. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2016, 44, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Mei, H.; Dörner, T.; Hiepe, F.; Radbruch, A.; Fillatreau, S.; Hoyer, B.F. Memory B and memory plasma cells. Immunol Rev 2010, 237, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlinton, D.; Good-Jacobson, K. Diversity among memory B cells: origin, consequences, and utility. Science 2013, 341, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, N. The double life of a B-1 cell: self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.R. B-1 B Cell Development. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 177, 2749–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, U.; Rajewsky, K.; Küppers, R. Human immunoglobulin (Ig)M+IgD+ peripheral blood B cells expressing the CD27 cell surface antigen carry somatically mutated variable region genes: CD27 as a general marker for somatically mutated (memory) B cells. J Exp Med 1998, 188, 1679–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangye, S.G.; Liu, Y.J.; Aversa, G.; Phillips, J.H.; de Vries, J.E. Identification of functional human splenic memory B cells by expression of CD148 and CD27. J Exp Med 1998, 188, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazayeri, M.H.; Pourfathollah, A.A.; Jafari, M.E.; Rasaee, M.J.; Dargahi, Z.V. The association between human B-1 cell frequency and aging: From cord blood to the elderly. Biomedicine & Aging Pathology 2013, 3, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.O.; Holodick, N.E.; Rothstein, T.L. Human B1 cells in umbilical cord and adult peripheral blood express the novel phenotype CD20+ CD27+ CD43+ CD70-. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbach, H.; Eichhorn, E.M.; Liese, J.G.; Girschick, H.J. Reference values for B cell subpopulations from infancy to adulthood. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 162, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątosa, B.; Wolska-Kuśnierz, B.; Pac, M.; Siewiera, K.; Gałkowska, E.; Bernatowska, E. B cell subsets in healthy children: reference values for evaluation of B cell maturation process in peripheral blood. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2010, 78, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehne, J. Charakterisierung und Quantifizierung von Lymphozyten-Subpopulationen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit allergischen Erkrankungen. Marburg: Fachbereich Medizin der Philipps-Universität Marburg (2016).

- Marie-Cardine, A.; Divay, F.; Dutot, I.; Green, A.; Perdrix, A.; Boyer, O.; Contentin, N.; Tilly, H.; Tron, F.; Vannier, J.-P.; et al. Transitional B cells in humans: characterization and insight from B lymphocyte reconstitution after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Immunol 2008, 127, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.; Braun, M.C.; Tan, B.K.; Rosenwald, A.; Cordier, C.; Conley, M.E.; Plebani, A.; Kumararatne, D.S.; Bonnet, D.; Tournilhac, O.; et al. Human blood IgM “memory” B cells are circulating splenic marginal zone B cells harboring a prediversified immunoglobulin repertoire. Blood 2004, 104, 3647–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kuchen, S.; Fischer, R.; Chang, S.; Lipsky, P.E. Identification and characterization of a human CD5+ pre-naive B cell population. J Immunol 2009, 182, 4116–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, G.P.; Ettinger, R.; Shirota, Y.; Yarboro, C.H.; Illei, G.G.; Lipsky, P.E. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood 2005, 105, 4390–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanichamy, A.; Barnard, J.; Zheng, B.; Owen, T.; Quach, T.; Wei, C.; Looney, R.J.; Sanz, I.; Anolik, J.H. Novel human transitional B cell populations revealed by B cell depletion therapy. J Immunol 2009, 182, 5982–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huck, K.; Feyen, O.; Ghosh, S.; Beltz, K.; Bellert, S.; Niehues, T. Memory B-cells in healthy and antibody-deficient children. Clin Immunol 2009, 131, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau, M.; Zouali, M. B-lymphocytes, innate immunity, and autoimmunity. Clinical Immunology 2005, 114, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnatz, K.; Schlesier, M. Flowcytometric phenotyping of common variable immunodeficiency. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry 2008, 74B, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, C.; Kivioja, T.; Schmitt, C.; Ferry, B.; Witte, T.; Eren, E.; Vlkova, M.; Hernandez, M.; Detkova, D.; Bos, P.R.; et al. The EUROclass trial: defining subgroups in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood 2008, 111, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchereau, J.; Rousset, F. Human B lymphocytes: phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation. Adv Immunol 1992, 52, 125–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, U.; Goossens, T.; Fischer, M.; Kanzler, H.; Braeuninger, A.; Rajewsky, K.; Küppers, R. Somatic hypermutation in normal and transformed human B cells. Immunol Rev 1998, 162, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, I.; Wei, C.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Anolik, J. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Semin Immunol 2008, 20, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Hardy, R.R.; Parks, D.R.; Herzenberg, L.A. The “Ly-1 B” cell subpopulation in normal immunodefective, and autoimmune mice. J Exp Med 1983, 157, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, K.; Hardy, R.R.; Stall, A.M.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A. Immunoglobulin-bearing B cells reconstitute and maintain the murine Ly-1 B cell lineage. European Journal of Immunology 1986, 16, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidman, C.L.; Shultz, L.D.; Hardy, R.R.; Hayakawa, K.; Herzenberg, L.A. Production of immunoglobulin isotypes by Ly-1+ B cells in viable motheaten and normal mice. Science 1986, 232, 1423–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Jain, P.; Deo, S.V.S.; Sharma, A. Flow cytometric analysis of CD5+ B cells: a frame of reference for minimal residual disease analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol 2004, 121, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, N.J.; Macardle, P.J.; Zola, H. Blood group antibodies are made by CD5+ and by CD5- B cells. Immunol Cell Biol 1997, 75, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jego, G.; Bataille, R.; Pellat-Deceunynck, C. Interleukin-6 is a growth factor for nonmalignant human plasmablasts. Blood 2001, 97, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descatoire, M.; Weill, J.-C.; Reynaud, C.-A.; Weller, S. A human equivalent of mouse B-1 cells? J Exp Med 2011, 208, 2563–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Andres, M.; Grosserichter-Wagener, C.; Teodosio, C.; van Dongen, J.J.M.; Orfao, A.; van Zelm, M.C. The nature of circulating CD27+CD43+ B cells. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 2565–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, K.M.; Blevins, M.W.; High, K.P.; Pang, B.; Swords, W.E.; Yammani, R.D. Aging promotes B-1b cell responses to native, but not protein-conjugated, pneumococcal polysaccharides: implications for vaccine protection in older adults. J Infect Dis 2014, 209, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.O.; Rothstein, T.L. Human B1 Cell Frequency: Isolation and Analysis of Human B1 Cells. Front Immunol 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covens, K.; Verbinnen, B.; Geukens, N.; Meyts, I.; Schuit, F.; Van Lommel, L.; Jacquemin, M.; Bossuyt, X. Characterization of proposed human B-1 cells reveals pre-plasmablast phenotype. Blood 2013, 121, 5176–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, M.; Hirota, S.; Hirano, K.; Fujii, H.; Sugahara-Tobinai, A.; Ishii, T.; Harigae, H.; Takai, T. Human CD43+ B cells are closely related not only to memory B cells phenotypically but also to plasmablasts developmentally in healthy individuals. Int Immunol 2015, 27, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quách, T.D.; Rodríguez-Zhurbenko, N.; Hopkins, T.J.; Guo, X.; Hernández, A.M.; Li, W.; Rothstein, T.L. Distinctions among Circulating Antibody-Secreting Cell Populations, Including B-1 Cells, in Human Adult Peripheral Blood. J Immunol 2016, 196, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.B.; Rathore, D.K.; Nair, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Raza, S.; Kanodia, P.; Sopory, S.; George, A.; Rath, S.; Bal, V.; et al. Comparison of Human Neonatal and Adult Blood Leukocyte Subset Composition Phenotypes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeus, B.; Kibler, A.; Brauser, M.; Homp, E.; Bronischewski, K.; Ross, J.A.; Görgens, A.; Weniger, M.A.; Dunst, J.; Kreslavsky, T.; Vitoriano da Conceição Castro, S.; Murke, F.; Oakes, C.C.; Rusch, P.; Andrikos, D.; Kern, P.; Könin-ger, A.; Lindemann, M.; Johansson, P.; Hansen, W.; Lundell, A.C.; Rudin, A.; Dürig, J.; Giebel, B.; Hoffmann, D.; Küppers, R.; Seifert, M. Human Cord Blood B Cells Differ from the Adult Counterpart by Conserved Ig Re-pertoires and Accelerated Response Dynamics. J Immunol. 2021, 206, 2839–2851, Epub 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lymphocyte Subset | Neonates (Cord Blood) |

Juveniles (Peripheral Blood) |

Adults (Peripheral Blood) |

|---|---|---|---|

| immature B cells | 1.4 ± 0.3 % | 1.7 ± 0.3 % | 2.3 ± 0.3 % |

| naïve B cells | 93.2 ± 1.2 % | 80.8 ± 1.8 % | 69.1 ± 3.4 % |

| transitional B cells | 27.9 ± 5.7 % | 9.0 ± 1.0 % | 30.9 ± 3.7 % |

| marginal zone B cells | 2.5 ± 0.4 % | 7.1 ± 0.8 % | 10.7 ± 1.4 % |

| IgM memory B cells | 0.2 ± 0.1 % | 1.4 ± 0.2 % | 1.7 ± 0.3 % |

| class switched memory B cells | 0.5 ± 0.1 % | 6.4 ± 1.0 % | 14.1 ± 2.0 % |

| plasmablasts | 0.5 ± 0.2 % | 0.7 ± 0.1 % | 1.4 ± 0.3 % |

| B1 cells (% of CD20+ cells) | 1.8 ± 0.3 % | - | 2.7 ± 0.4 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).