Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient data collection

2.2. CT scanning and image interpretation

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sex distribution and age at diagnosis

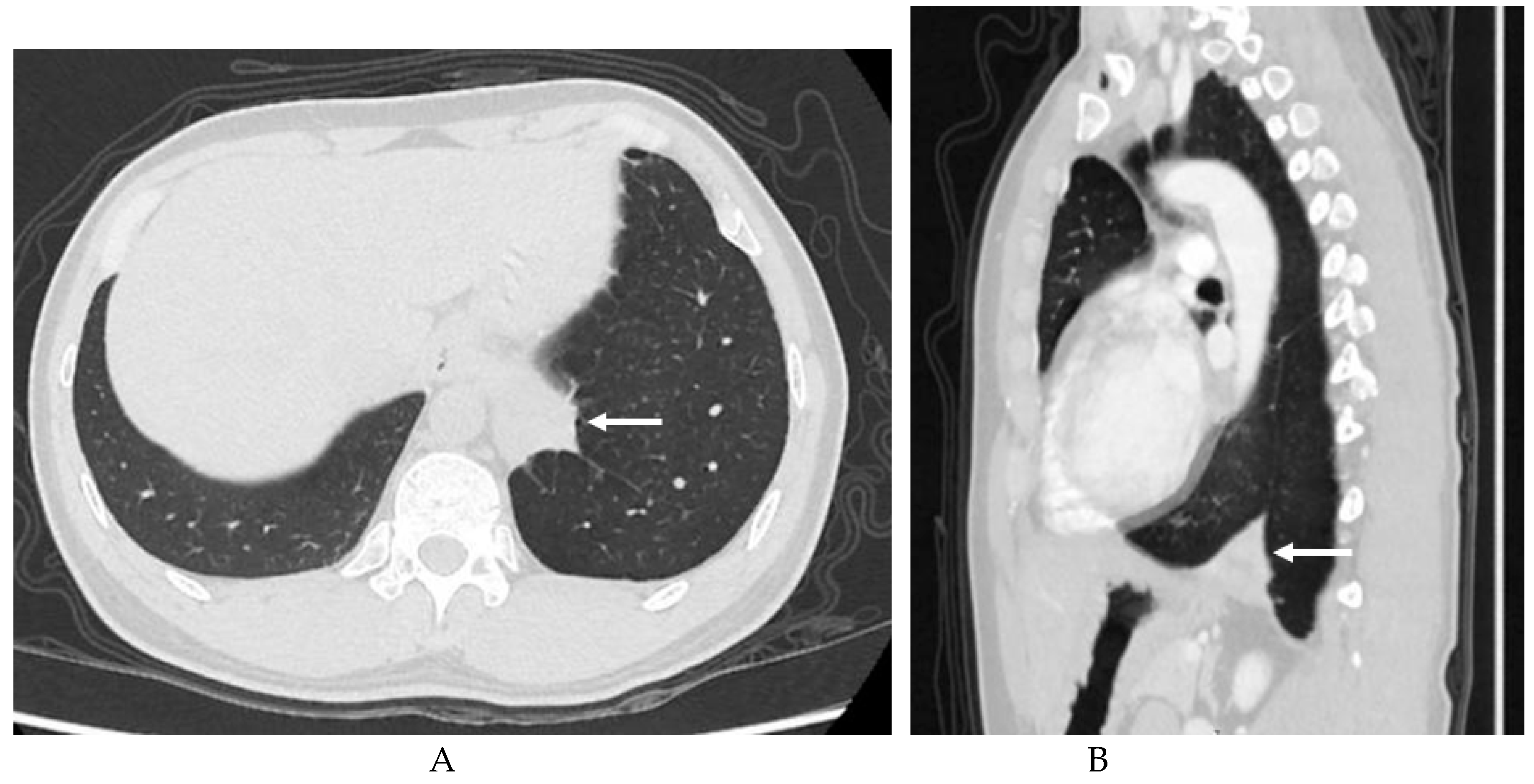

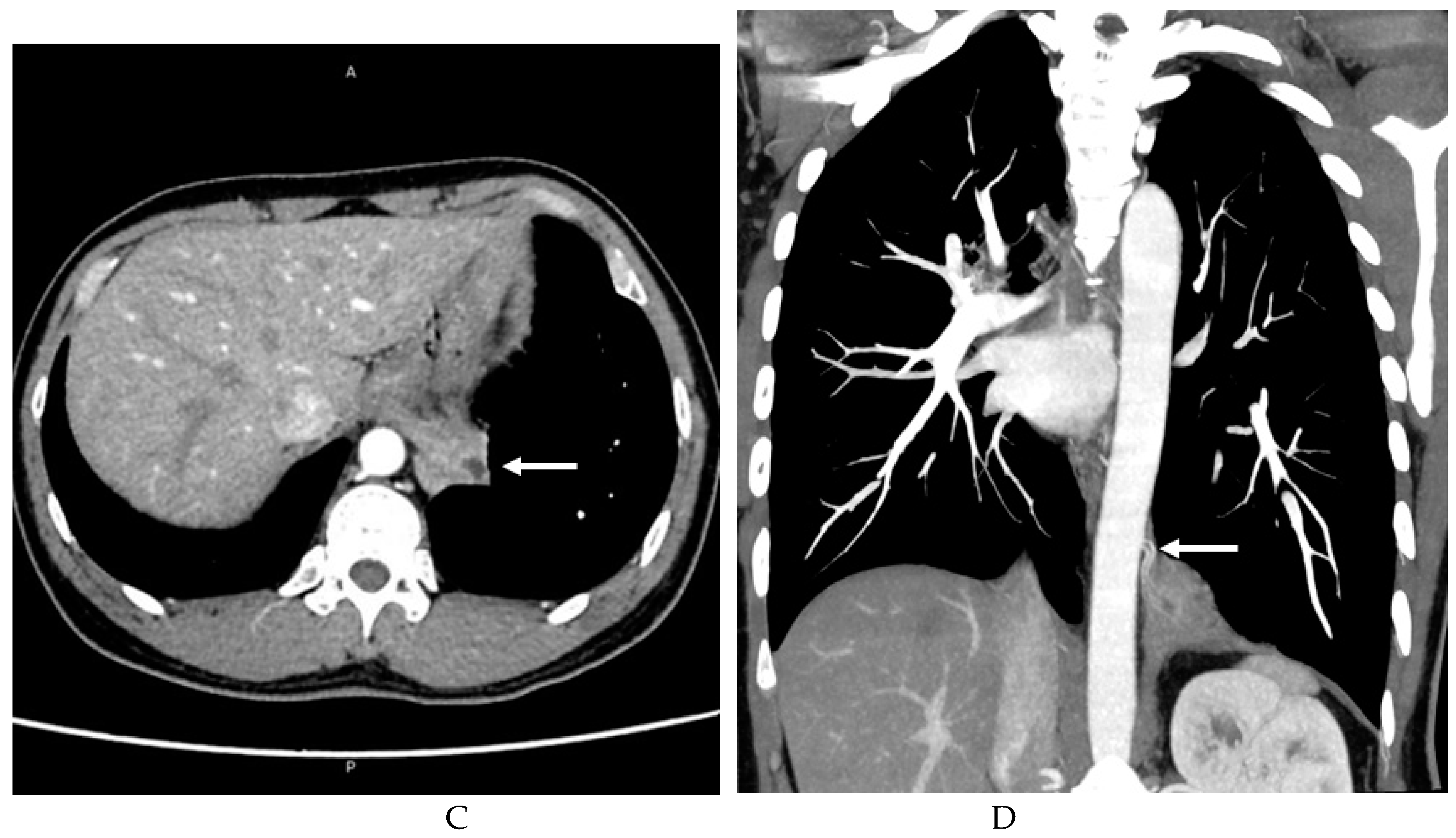

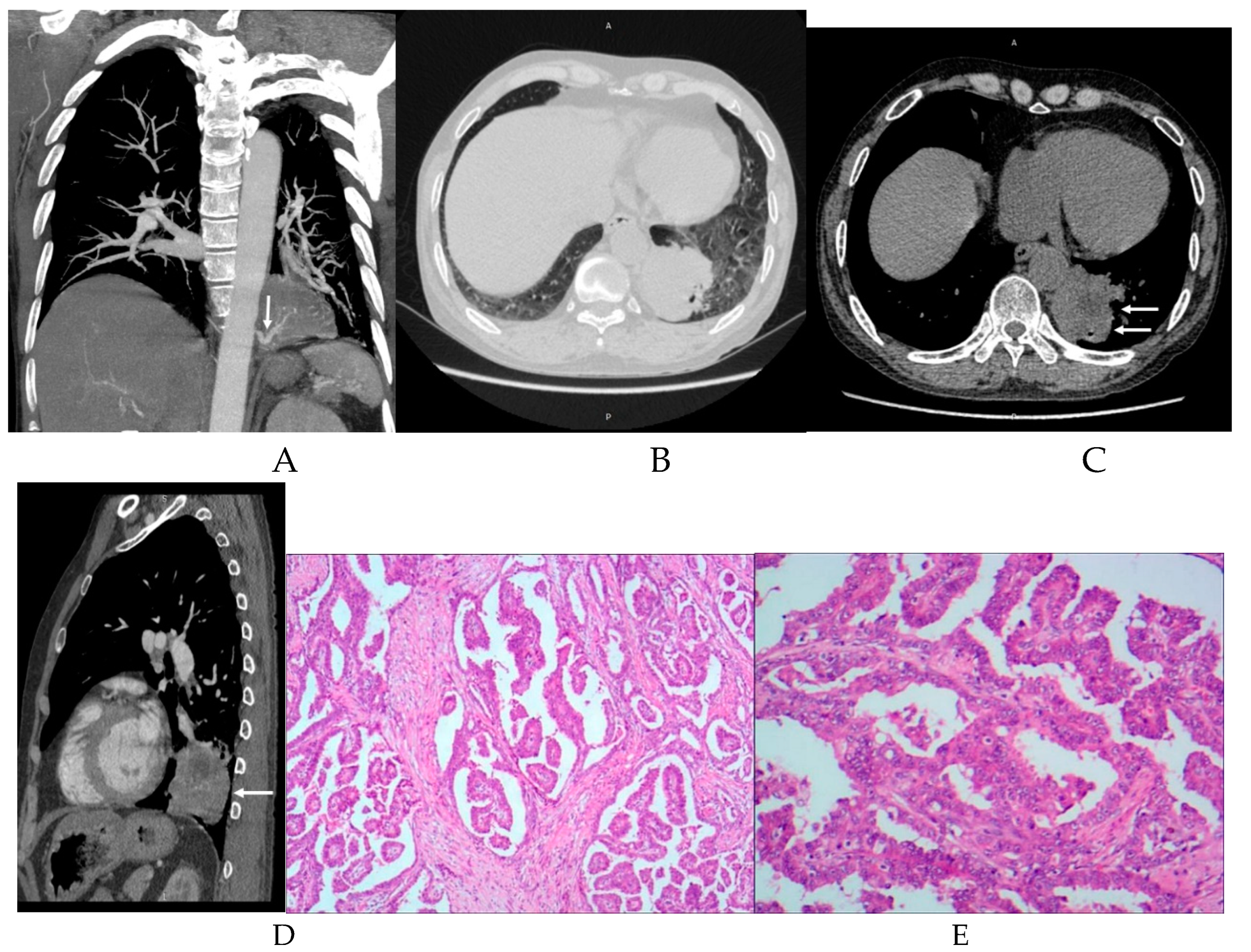

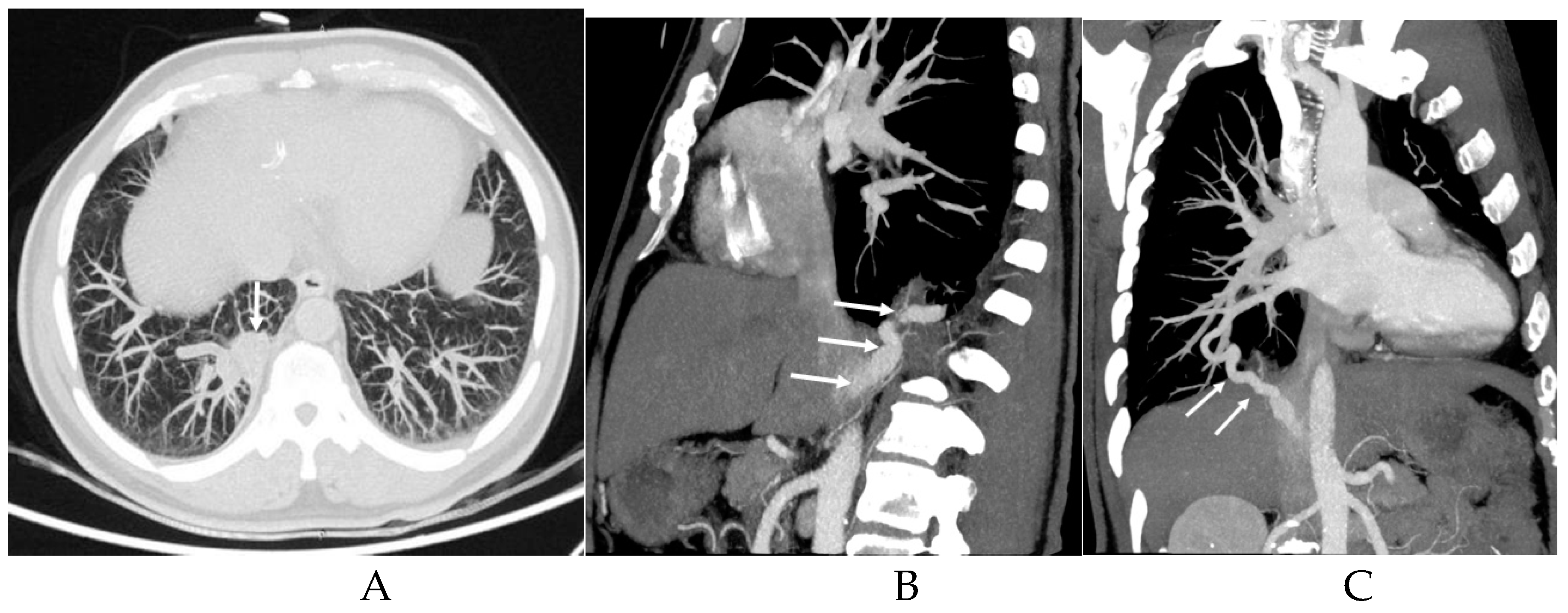

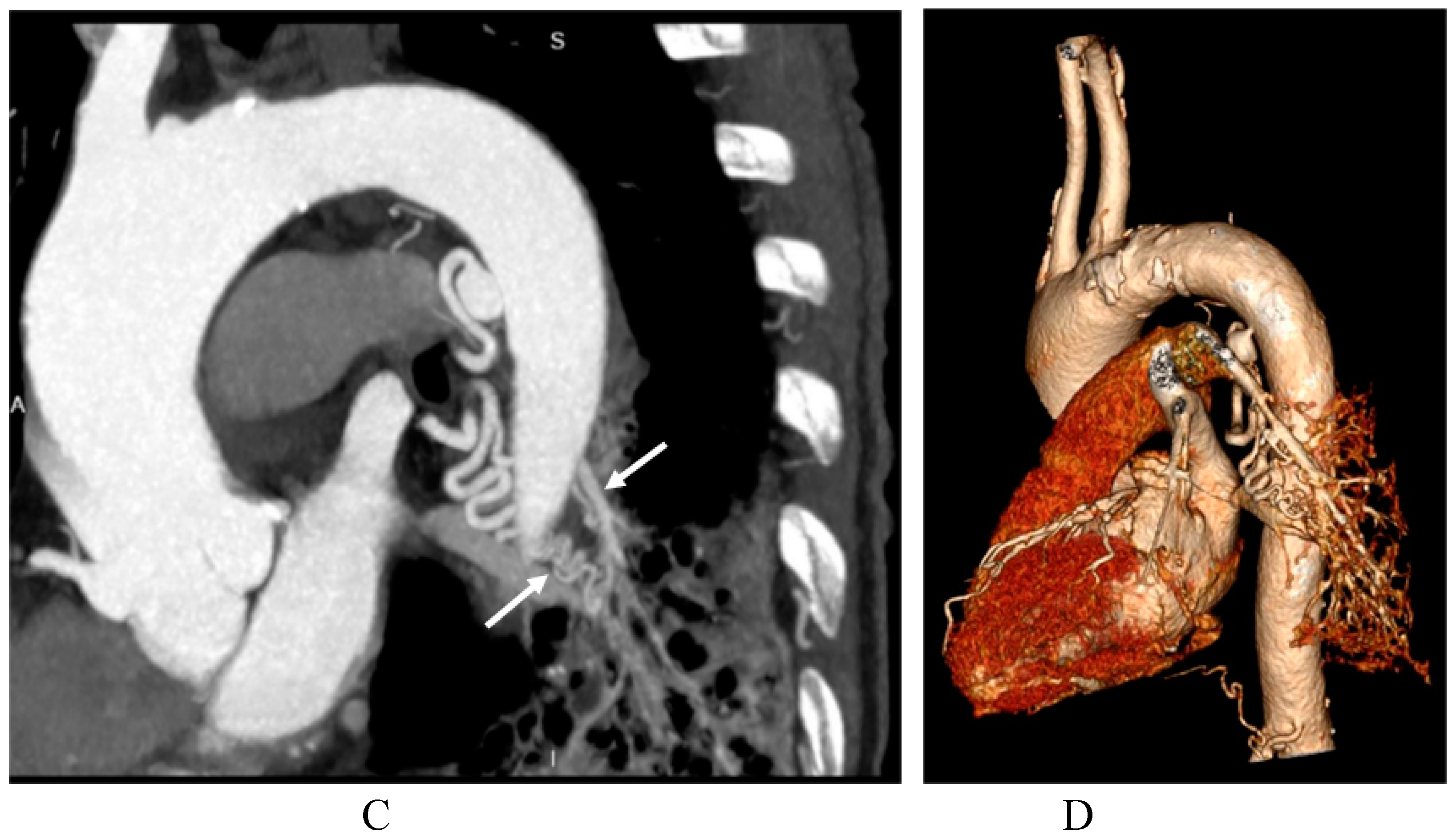

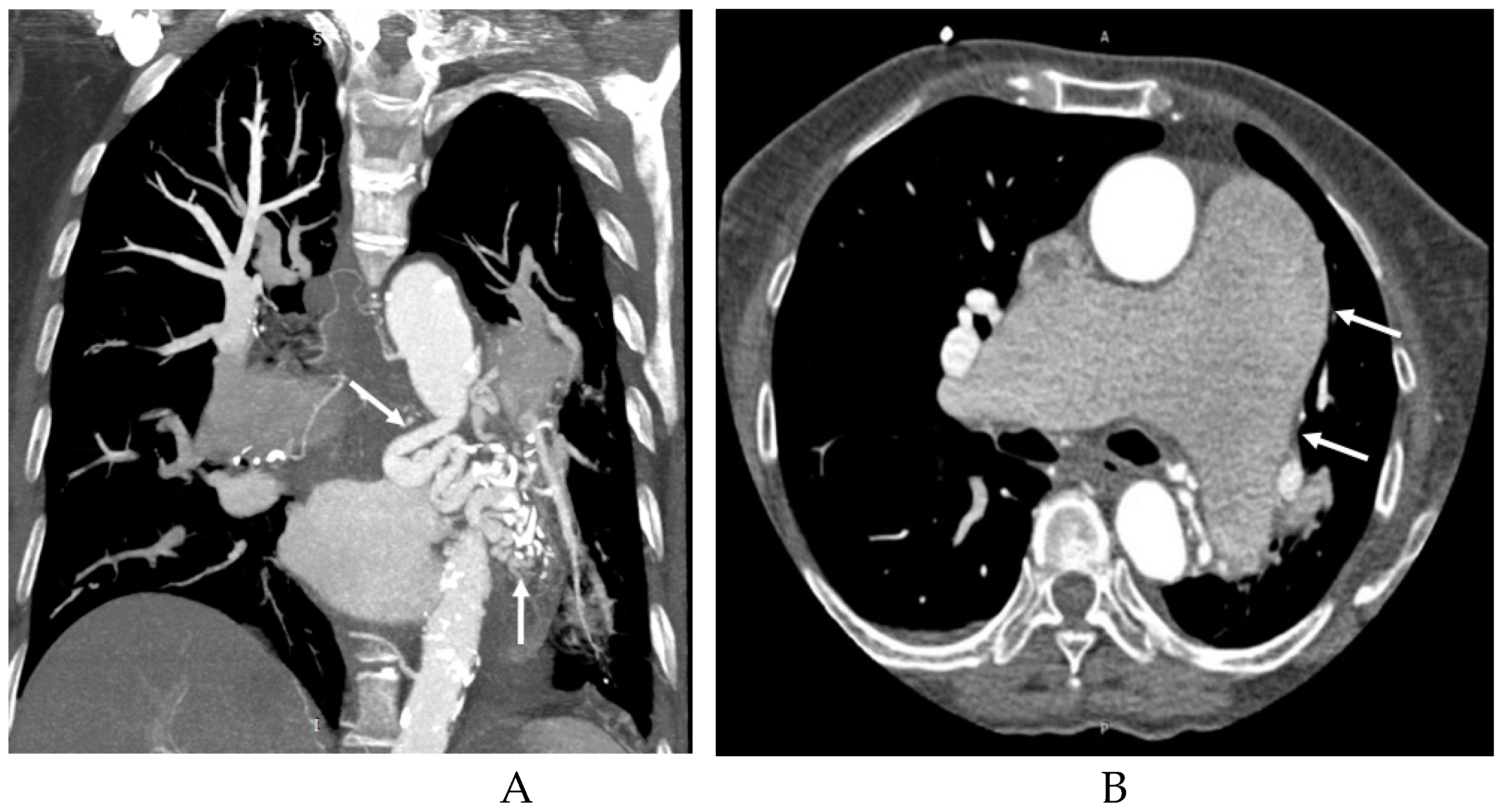

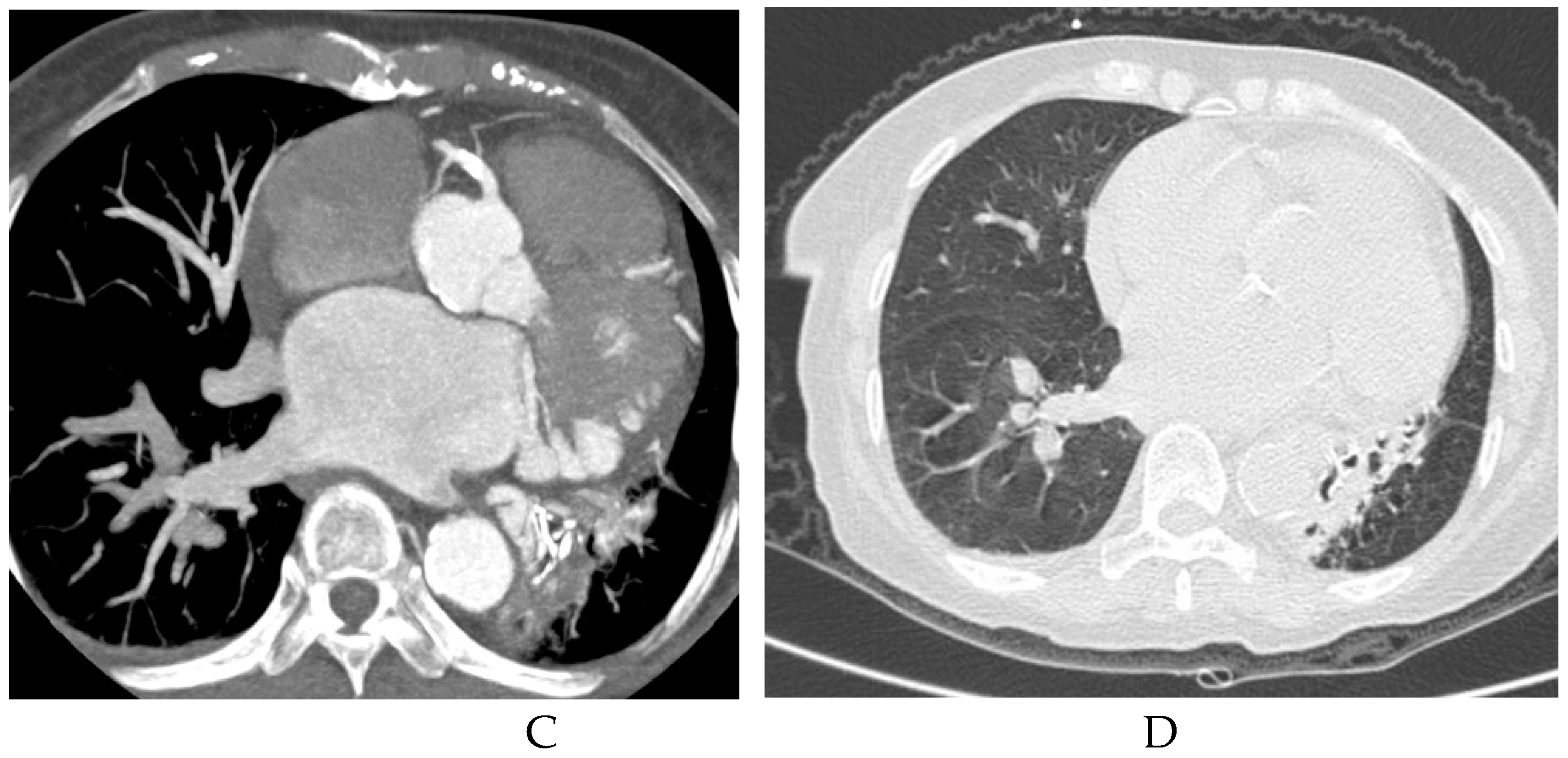

3.2. Imaging appearances of CTPA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabelloni, M.; Faggioni, L.; Accogli, S.; Aringheri, G.; Neri, E. Pulmonary sequestration: what the radiologist should know. Clin. Imaging. 2021, 73, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, C.C.; Kollias, V.D.; Panayotopoulos, P.P. Pulmonary sequestration. Experience with eight consecutive cases. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 1997, 31, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangui, F.; Charfi, M.; Abouda, M.; Charfi, M.R. Pulmonary sequestration in a healthy teenage girl. Tunis. Med. 2019, 97, 604–605. [Google Scholar]

- Berna, P.; Lebied, E.I.D.; Assouad, J.; Foucault, C.; Danel, C.; Riquet, M. Pulmonary sequestration and aspergillosis. Eur. J. Cardiothroac. Surg. 2005, 27, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvati, F. Cardiovascular, broncho-parenchima and neoplastic anomalies related to pulmonary sequestration: a critical review. Recenti. Prog. Med. 2018, 109, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franko, J.; Bell, K.; Pezzi, C.M. Intraabdominal pulmonary sequestration. Curr. Surg. 2006, 63, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulys, A.; Samalavicius, N.; Cicenas, S.; Petraitis, T.; Trakymas, M.; Sheinin, D.; Gatijatullin, L. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration. Int. Med. Case. Rep. J. 2011, 4, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirai, S.; Hamanaka, Y.; Mitsui, N.; Uegami, S.; Matsuura, Y. Surgical treatment of infected intralobar pulmonary sequestration: a collective review of patients older than 50 years reported in the literature. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 13, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adzic-Vukicevic, T.N.; Radovanovic, D.V.; Acimovic, B.D.; Popovic, M.P. Pulmonary sequestration mimicring lung cancer: A case report. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2016, 73, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashtoush, B.; Memarpour, R.; Gonzalez, J.; Gleason, J.B.; Hadeh, A. Pulmonary sequestration: A 29 patient case series and review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, AC05-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, C.V.; Ly, T.T.; Minh, N.M. Intralobar pulmonary sequestration supplied by vessel from the inferior vena cava: literature overview and case report. Radiol. Case. Rep. 2022, 17, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafig, M.; Ali, A.; Dawar, U.; Setty, N. Rare cause of haemoptysis: bronchopulmonary sequestration. BMJ. Case. Rep. 2021, 14, e239140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xiao, Y. Pulmonary sequestration in adult patients: a retrospective study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015, 48, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Zha, Y.; Yang, Z. Evaluation of pulmonary sequestration with multidetector computed tomography angiography in a select cohort of patients: A retrospective study. Clinics. 2016, 71, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X. Distribution, diagnosis, and treatment of pulmonary sequestration: Report of 208 cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, F. Pulmonary sequestration: a retrospective analysis of 2625 cases in China. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011, 40, 439-e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, T.; Hakiri, S.; Yokoi, K. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration in the middle mediastinum. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.W.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Gao, J.B.; Ma, X.X.; Ding, P.X. The clinical value of computer tomographic angiography for the diagnosis and therapeutic planning of patients with pulmonary sequestration. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013, 43, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoretti, F.; Cerillo, A.G.; Chiappino, D. The levoatriocardinal vein. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2005, 26, 494–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, P.P.; Mahani, M.G.; Lu, J.C.; Dorfman, A.L. Levoatriocardinal vein and mimics: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 205, W162-71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saremi, F.; Ho, S.Y. Extracardiac pulmonary-systematic connection via persistent levoatriocardinal vein in adults. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 34, e1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, N.; Maldjian, P. Levoatriocardinal vein: an unusual cause of right-left shunting. J. Clin. Imaging. Sci. 2014, 4, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Canan, A.; Aziz, M.U.; Abbara, S. A rate pulmonary-systemic connection: levoatriocardinal vein. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging. 2020, 2, e190228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karangelis, D.; Avramidis, D.; Mousiama, T.; Karamitsos, T.D.; Mitropoulos, F.; Tzifa, A. Levoatriocardinal vein: a rarely recognized cause of recurrent cardiac and cerebral thromboembolic events. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 589.e9–589.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzog, P.; Roujeau, J.; Marcou, J. Epidermoid cancer developed on a sequestration. J. Fr. Med. Chir. Thorac. 1963, 17, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Imaging appearances | Subtype | Number of cases |

| Subtype of disease | ILS | 54(98.18%) |

| ELS | 1(1.82%) | |

| Location of disease | LLL | 42(76.36%) |

| RLL | 12(21.82%) | |

| BLL | 1(1.82%) | |

| Supplying artery | Aorta A | 1(1.82%) |

| Aorta D | 47(85.45%) | |

| CA | 7(12.73%) | |

| BA | 1(1.82%) | |

| Draining vessels | PV | 49(89.09%) |

| UV | 1(1.82%) | |

| IV | 1(1.82%) | |

| PA | 11(20.00%) | |

| NF | 2(3.64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).