Submitted:

11 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

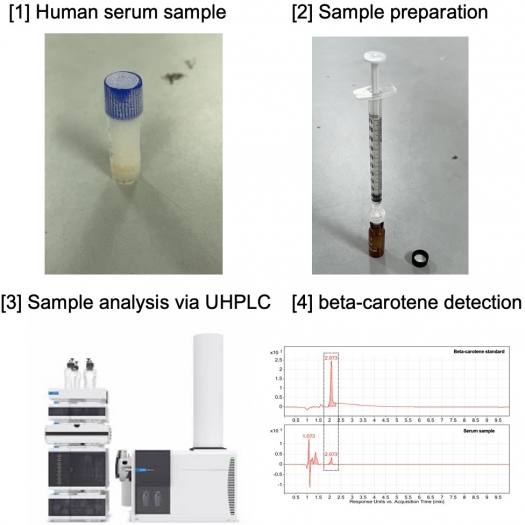

Human sera sample preparation

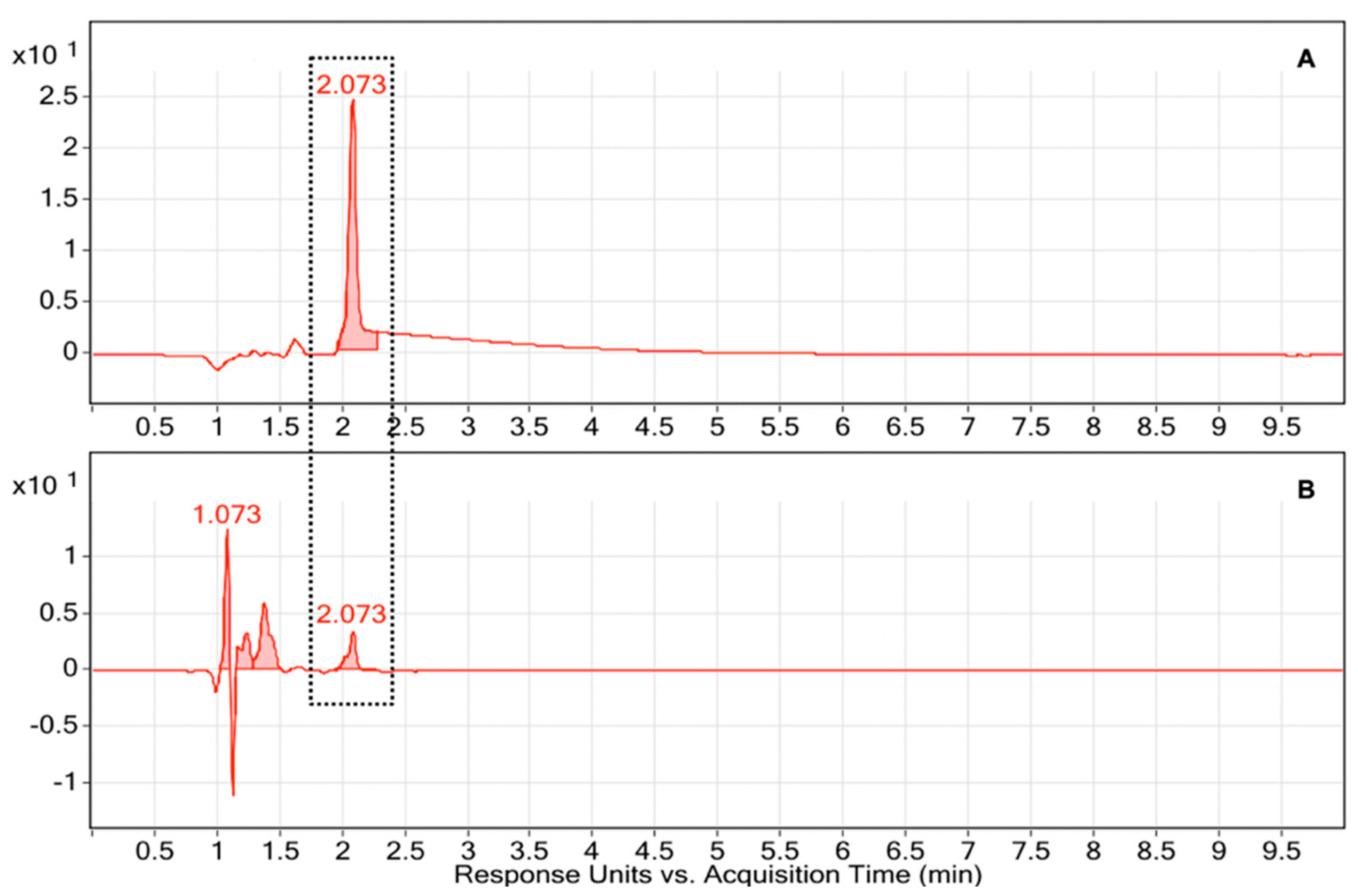

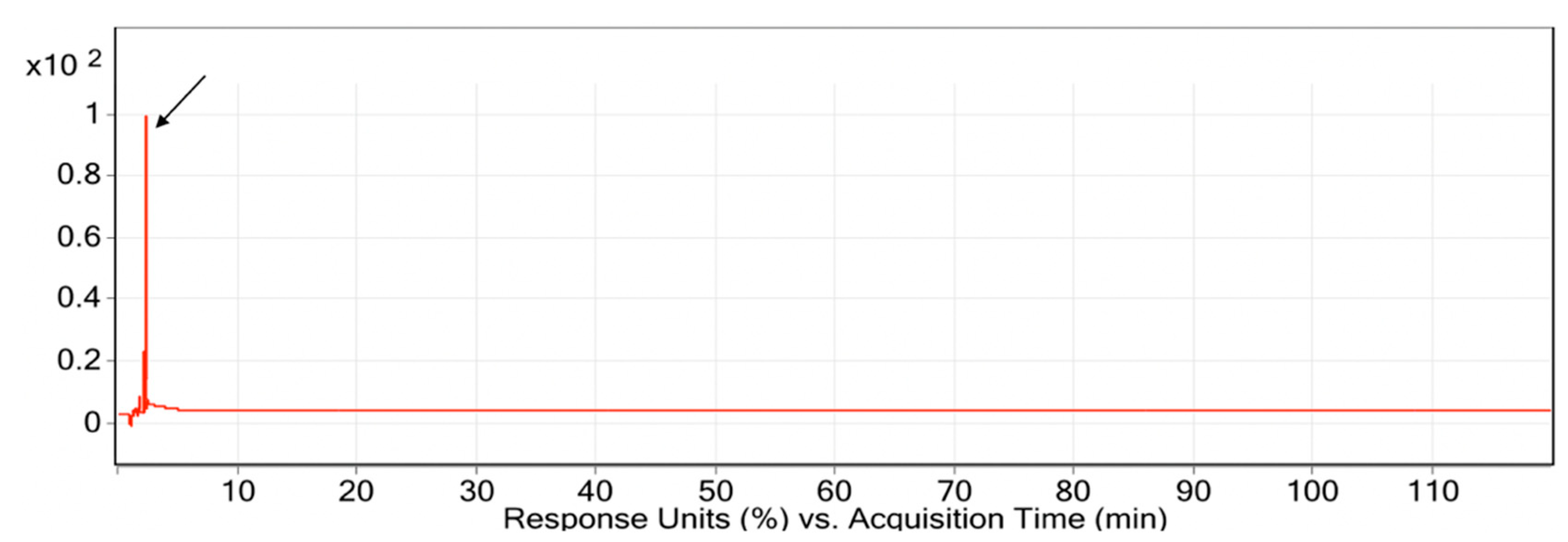

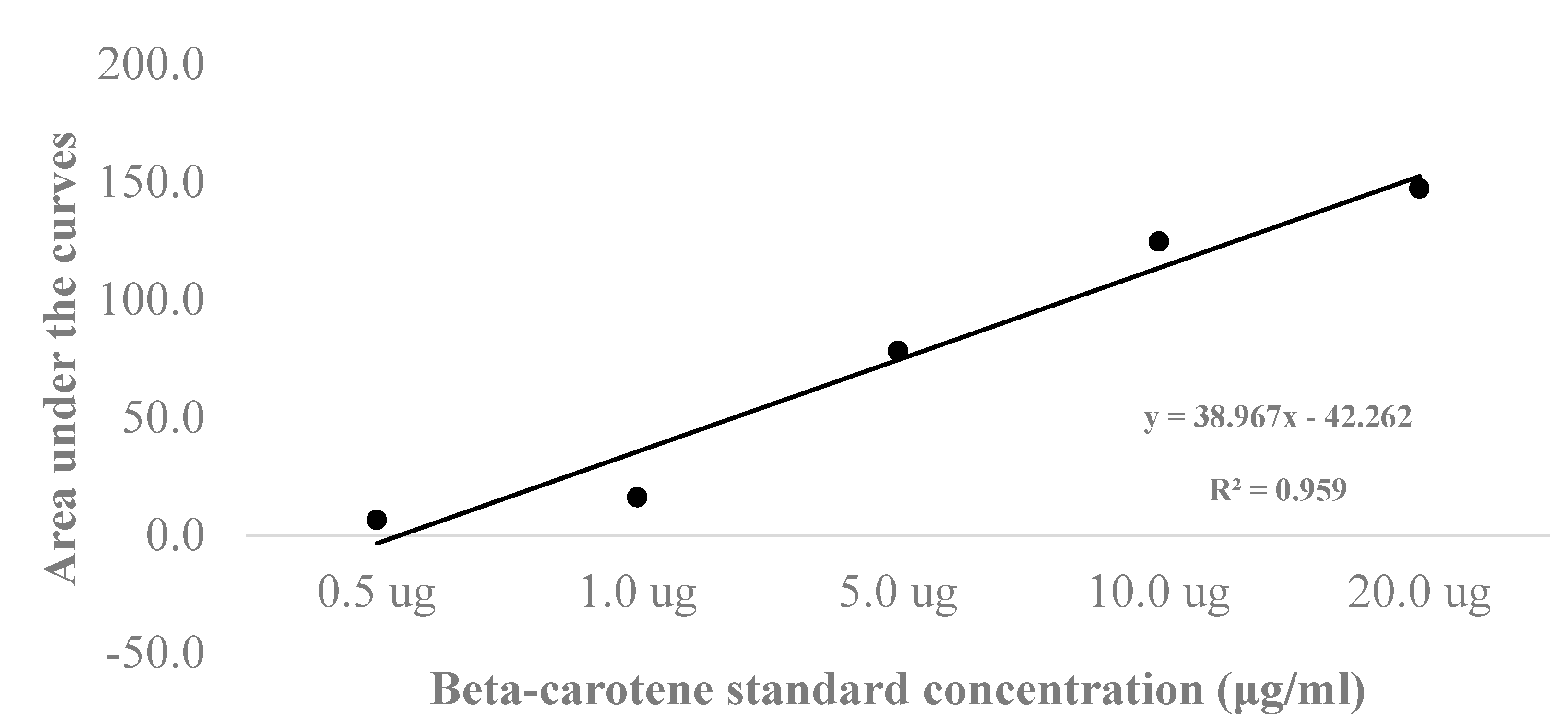

Optimizing protocol for detecting beta-carotene in human sera

Statistical analysis

Ethical consideration

Result and Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgement

Disclosure statement

References

- World Health Organization. (2021). Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases [Access online 14 February 2022].

- Lugrin, J., Rosenblatt-Velin, N., Parapanov, R., & Liaudet, L. (2014). The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biological chemistry, 395(2), 203-230. [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A., Rashidy-Pour, A., Parohan, M., Zargar, M. S., & Shab-Bidar, S. (2018). Dietary Antioxidants, Circulating Antioxidant Concentrations, Total Antioxidant Capacity, and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Observational Studies. Advances in Nutrition, 9(6), 701-716. [CrossRef]

- Yao, N., Yan, S., Guo, Y., Wang, H., Li, X., Wang, L., . . . Cui, W. (2021). The association between carotenoids and subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food & Function, 12(11), 4768-4782. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Weinstein, S. J., Yu, K., Männistö, S., & Albanes, D. (2018). Serum Beta Carotene and Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality. Circulation Research, 123(12), 1339-1349. [CrossRef]

- Langi, P., Kiokias, S., Varzakas, T., & Proestos, C. (2018). Carotenoids: From Plants to Food and Feed Industries. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1852, 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pozuelo, G., Navarro-González, I., González-Barrio, R., Santaella, M., García-Alonso, J., Hidalgo, N., . . . Periago, M. J. (2015). The effect of tomato juice supplementation on biomarkers and gene expression related to lipid metabolism in rats with induced hepatic steatosis. European Journal of Nutrition, 54(6), 933-944. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P., Sreelakshmi, Y., & Sharma, R. (2015). A rapid and sensitive method for determination of carotenoids in plant tissues by high performance liquid chromatography. Plant Methods, 11(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Deng, Z., Wu, T., Liu, R., Loewen, S., & Tsao, R. (2012). Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolics with maximal antioxidant activities in tomatoes. Food Chemistry, 130, 928–936. [CrossRef]

- Ligor, M., Kováčová, J., Gadzała-Kopciuch, R. M., Studzińska, S., Bocian, S., Lehotay, J., & Buszewski, B. (2014). Study of RP HPLC Retention Behaviours in Analysis of Carotenoids. Chromatographia, 77(15), 1047-1057. [CrossRef]

- Bower, K. (2018). The relationship between R2 and precision in bioassay validation. BioProcess International, 16(4), 26.

- UCSF Health. (2017). Beta-carotene blood test. Retrieved from https://www.ucsfhealth.org/medical-tests/beta-carotene-blood-test [Access online 15th February 2022].

- Paliakov, E. M., Crow, B. S., Bishop, M. J., Norton, D., George, J., & Bralley, J. A. (2009). Rapid quantitative determination of fat-soluble vitamins and coenzyme Q-10 in human serum by reversed phase ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography with UV detection. Journal of Chromatography B, 877(1), 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Granado-Lorencio, F., Herrero-Barbudo, C., Blanco-Navarro, I., & Pérez-Sacristán, B. (2010). Suitability of ultra-high performance liquid chromatography for the determination of fat-soluble nutritional status (vitamins A, E, D, and individual carotenoids). Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 397(3), 1389-1393. [CrossRef]

- Barua, A. B., & Olson, J. A. (1998). Reversed-phase gradient high-performance liquid chromatographic procedure for simultaneous analysis of very polar to nonpolar retinoids, carotenoids and tocopherols in animal and plant samples. Journal of Chromatography B Biomedical Sciences and Applications, 707(1-2), 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J. N., Madsen, P. L., Dragsted, L. O., & Arrigoni, E. (2017). Optimized, Fast-Throughput UHPLC-DAD Based Method for Carotenoid Quantification in Spinach, Serum, Chylomicrons, and Feces. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65(4), 973-980. [CrossRef]

- Hosotani, K., & Kitagawa, M. (2003). Improved simultaneous determination method of β-carotene and retinol with saponification in human serum and rat liver. Journal of Chromatography B, 791(1), 305-313. [CrossRef]

- 18. 11. Hsu, B. Y., Pu, Y. S., Inbaraj, B. S., & Chen, B. H. (2012). An improved high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection-mass spectrometry method for determination of carotenoids and their precursors phytoene and phytofluene in human serum. Journal of Chromatography B: Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences, 899, 36-45. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. L., New, A. L., & Ong, C. N. (2003). Simultaneous determination of tocotrienols, tocopherols, retinol, and major carotenoids in human plasma. Clinical Chemistry, 49(12), 2056-2066. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, V., Pu, Y. S., & Chen, B.-H. (2005). An improved HPLC method for determination of carotenoids in human serum. Journal of Chromatography B: Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences, 824, 99-106.

- Thibeault, D., Su, H., Macnamara, E., & Schipper, H. (2009). Isocratic rapid liquid chromatographic method for simultaneous determination of carotenoids, retinol, and tocopherols in human serum. Journal of Chromatography B: Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences, 877, 1077-1083. [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, M.-S., Yang, F.-L., Wang, G.-S., And, H., & Chen, B.-H. (2004). Determination of Major Carotenoids in Human Serum by Liquid Chromatography. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bohoyo-Gil, D., Dominguez-Valhondo, D., Parra, J., & Gonzalez-Gomez, D. (2012). UHPLC as a suitable methodology for the analysis of carotenoids in food matrix. European Food Research and Technology, 235, 1055. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A. (2018a). Differences between HPLC and UPLC. https://www.pharmaguideline.com/2018/04/differences-between-hplc-and-uplc.html [Access online 14 February 2022].

- Hopkins, T. (2019). The Role of Methanol and Acetonitrile as Organic Modifiers in Reversed-phase Liquid Chromatography. https://www.chromatographytoday.com/article/hplc-uhplc/31/advanced-chromatography-technologies/the-role-of-methanol-and-acetonitrile-as-organic-modifiers-in-reversed-phase-liquid-chromatography/2507 [Access online 14 February 2022].

- Choudhary, A. (2018b). Difference between C8 and C18 Columns Used in HPLC System. https://www.pharmaguideline.com/2018/05/difference-between-c8-and-c18-columns.html [Access online 14 February 2022].

- Dolan, J. (2014). How Much Retention Time Variation Is Normal? LCGC North America, 32(8), 546–551. https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/how-much-retention-time-variation-normal-0 [Access online 14 February 2022].

| Mean | Standard deviation | Coefficient of variation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra test (1) | 2.077 | 0.005 | 0.2% |

| Intra test (2) | 2.241 | 0.002 | 0.1% |

| Inter test | 2.159 | 0.004 | 0.2% |

| Human sera | Average area under the curve | Concentration (μg/ml) |

Concentration (μmol/l) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17.86 | 1.54 | 2.87 |

| 2 | 22.34 | 1.66 | 3.08 |

| 3 | 58.43 | 2.58 | 4.81 |

| 4 | 3.35 | 1.17 | 2.18 |

| 5 | 11.52 | 1.38 | 2.57 |

| Average | 1.67 | 3.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).