1. Introduction

Superhydrophobic surfaces, such as those observed in natural structures like lotus leaves and insect wings (e.g., geckos and desert beetles [

1] ), have served as inspiration for the engineering of diverse superhydrophobic surfaces. These surfaces are characterized by water droplets exhibiting contact angles exceeding 150°, accompanied by low contact angle hysteresis ranging from 2° to 10° [

2,

3]. In contrast, superoleophobic surfaces, which repel oils, are not commonly found in nature due to the lower surface tension exhibited by oils in comparison to water [

4,

5,

6]. This property of oils renders the construction of oil-repellent surfaces considerably more challenging than achieving superhydrophobicity. Achieving superoleophobicity necessitates precise control over adhesive and cohesive forces, as well as the consideration of mechanical durability [

3].

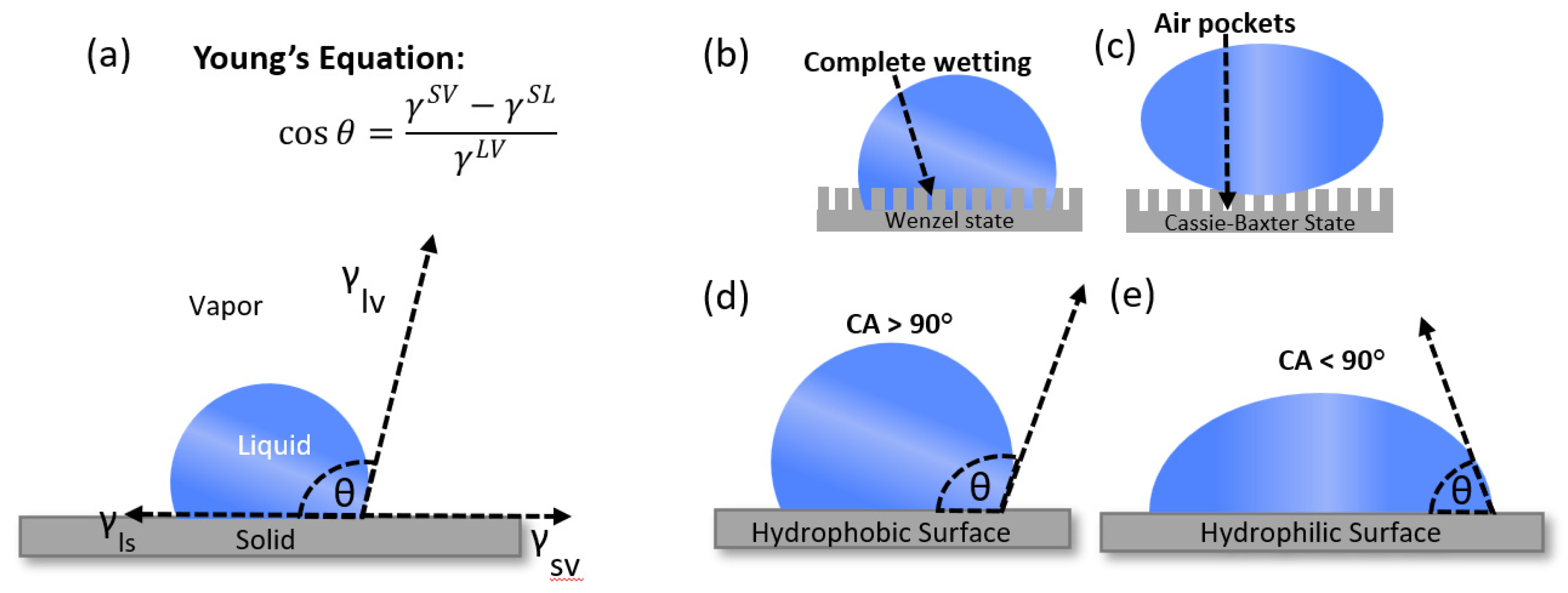

The concept of contact angle equilibrium was originally introduced by T. Young in 1805. The contact angle θ denotes the angle formed between the liquid's surface and the outline of the contact surface when a liquid droplet is placed upon a flat surface. The surface free energy of a solid surface can be mathematically described by Young's equation [

7]:

The wetting state of a liquid on a solid surface can be categorized as either the Cassie-Baxter state or the Wenzel state. [

5] (

Figure 1 (d) and (e)). In the Cassie-Baxter state, air pockets trapped beneath water droplets on the surface's grooves give rise to a solid-air hydrophobic interface (

Figure 1). In contrast, the Wenzel state occurs when the liquid infiltrates the indentations and protrusions of the solid surface, resulting in enhanced surface wettability attributable to an increased contact area. The Wenzel state is often referred to as a "fully wetted" interface.

Surface roughness plays a pivotal role in determining the contact angle hysteresis (CAH) exhibited by superhydrophobic surfaces [

3]. Furthermore, the static contact angle significantly influences surface wettability and adhesiveness [

9]. The surface tension of the testing materials also exerts a substantial influence on the achieved contact angle. As the surface tension of the oil used for testing decreases, attaining higher contact angles becomes increasingly challenging. Various techniques, such as electrochemical deposition [

10,

11], electrospinning method [

12,

13], wet chemical reaction[

14,

15,

16], hydrothermal synthesis [

17,

18,

19], phase separation method [

20,

21,

22] and chemical vapor deposition [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] have been employed in prior studies to achieve superhydrophobicity.

However, these techniques are often limited by their complexity, the need for expensive equipment, or protracted procedures. In this study, we present a technique for fabricating superoleophobic surfaces that offers simplicity, requires no expensive machinery or materials, and boasts a rapid drying process. Moreover, the resulting surfaces demonstrate exceptional durability during subsequent testing processes.

2. Experimental Section

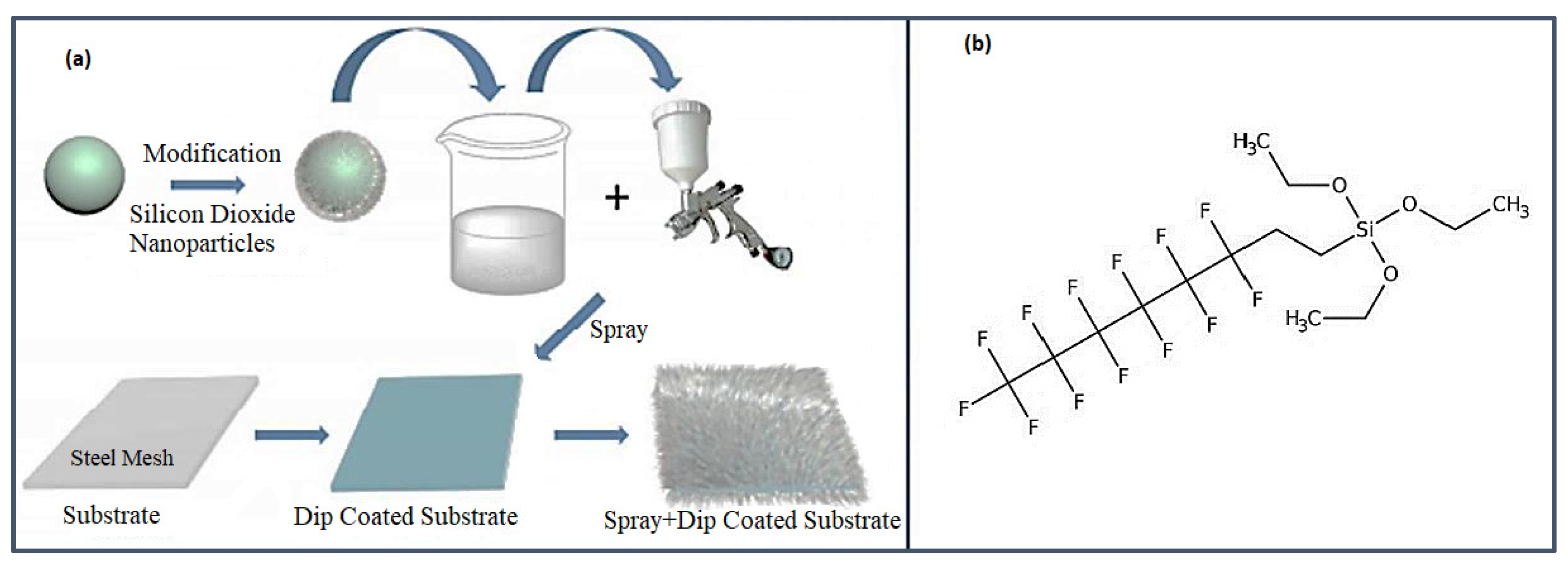

The fabrication of oil-repellent surfaces relies on the manipulation of surface tension. However, it is also possible to create water-repellent and oil-attractive surfaces based on the principles of surface tension theory. One such multifunctional fluorosilane and adhesion promoter used to achieve low surface energy surfaces is 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (C14H19F13O3Si). By incorporating fluorosilanes and testing materials with low surface tension, such as hexadecane (27.47 mN/m at 25 °C) and soybean oil (32.9 mN/m at 25 °C), it becomes challenging for oils to bond, resulting in what is commonly referred to as "nonstick surfaces."

2.1. Materials:

The materials utilized in the experiments included Perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (C14H19F13O3Si) 98% from Sigma Aldrich (density of 1.3299 g/mL at 25 °C), absolute ethanol from Sigma Aldrich, toluene of 99.8% purity from Sigma Aldrich, and silicon dioxide nanoparticles (>100 nm diameter, 2.33 g/mL at 25 °C). Before chemical modification, all substrates underwent cleaning with deionized water and isopropyl alcohol (IPA), followed by extraction with toluene to remove any potential impurities. This experimental setup involved various nano-sized materials and fluoroalkylsilane to achieve superhydrophobicity and superoleophobicity. Hexadecane and soybean oils were selected for evaluating the experiments due to their low surface tension values (17.90 and 32.9 mN/m, respectively). The equipment used for testing is SEM (ZEISS MERLIN Compact SEM), Goniometer (Drop Meter Element A-60, 0.5 mm flat syringe tip) and Mirka waterproof sandpaper with grit range from P600 to P10,000 sized 230x280mm.

2.2. Synthesis of Superhydrophobic Surface:

The initial series of experiments focused on fabricating superhydrophobic surfaces. To accomplish this, 1 g of 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (C

14H

19F

13O

3Si) was mixed with 100 mL of absolute ethanol and stirred magnetically for 20 minutes at room temperature (25 °C) to enable hydrolysis of the fluoroalkylsilane. SiO

2 nanoparticles were then added to the stirring solution and left for 1 hour to achieve a homogeneous suspension. The suspension was subsequently sprayed onto the substrates using a spray gun at 20 psi with a pressure of 0.6 MPa and a distance of approximately 15-20 cm (

Figure 2). The treated surfaces demonstrated superhydrophobicity once they were dried in an oven at 80 °C for 2 hours.

2.3. Synthesis of Superoleophobic Surface:

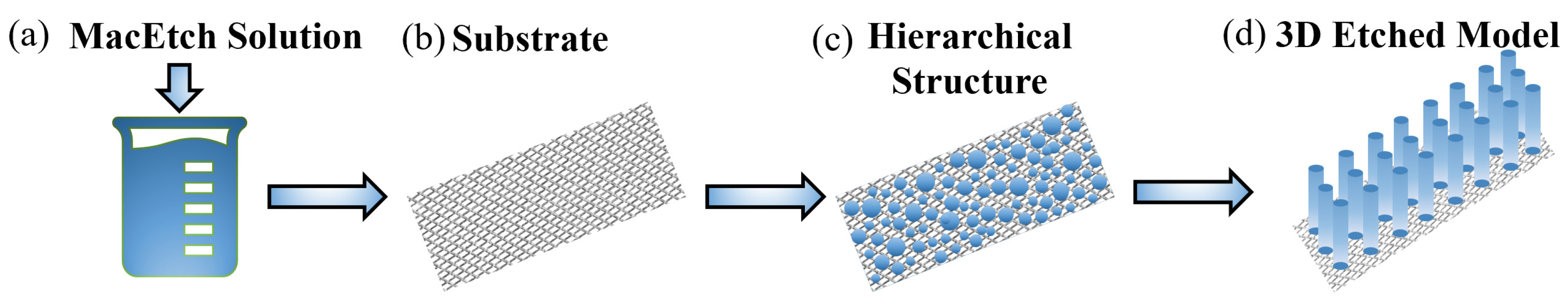

To achieve superoleophobicity, a similar methodology was employed due to the simplicity of the experimental technique. In this case, a hierarchical or re-entrant structure was introduced to attain the Cassie-Baxter state. The re-entrant structure was formed by conducting metal-assisted chemical Etching (MacEtch) before applying the PFOTES and SiO2 solution to the substrate. MacEtch process involved preparing an etching solution I containing HCl (37 wt. %), H2O2 (30 wt. %), and H3PO4 (85 wt. %) for the acidic etching of the steel substrate. Additionally, a solution II was prepared by mixing deionized water and FeCl3.6H2O under magnetic stirring until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. The solutions I and II were then combined in a beaker and left to form a suspension for 20 minutes in an airtight environment. Steel mesh substrates were immersed in this suspension for varying durations of 20 minutes, 40 minutes, and 1 hour to achieve three distinct levels of hierarchical structures on the steel, which were subsequently dried at 80 °C for 1 hour. The cylindrical structures formed by MacEtch served as the basis for the mechanical durability of the fabricated surfaces (

Figure 3).

Continuing from the previous experimental technique, another solution III was prepared by mixing tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and 1 g of 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H perfluorodecyltrichlorosilane (PFDTS) in a beaker containing 100 mL of ethanol. The mixture was magnetically stirred under sealed conditions for an hour. Finally, the three steel mesh samples with hierarchical structures were immersed in the suspension and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 2 hours. The nanostructures formed on these samples were assessed for contact angle and observed under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The sample immersed in the MacEtch solution for 60 minutes exhibited the best results in terms of the nanostructure formed on the steel mesh.

Figure 4 illustrates the analysis of metal-etched steel immediately after the hierarchical structure formation to observe the contact angle for soybean oil and evaluate the surface roughness.

2.4. Comparison of Amount of SiO2 for Oil-Repellency:

To understand the effect of SiO2 nanoparticles in the solution, 1 g, 2 g, and 3 g of SiO2 (100 nm) were added to 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H perfluorodecyltrichlorosilane (C8H4Cl3F17Si) and 99 g of ethanol. The substrates were soaked in the suspension for 30 minutes before being dried in the oven for dip coating. The surfaces fabricated with solutions A, B, and C exhibited remarkably similar hydrophobic performances, but solution C demonstrated the highest contact angle with soybean oil, making it ideal for further testing. Solution C was used throughout the experiments unless specified. The resulting surface coating provided the desired mechanical durability, as evidenced by the retention of the hierarchical structure and oil-repellent nature even after repetitive mechanical and wear abrasion tests. The resulting contact angle values are listed in

Table 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formation of Hierarchical Structures:

When using an MacEtch solution containing HCl, H2O2, and H3PO4, along with a suspension of FeCl3.6H2O, over a steel mesh substrate, several reactions and processes take place that contribute to form hierarchical structures. First, the acidic nature of the etching solution, particularly HCl, promoted the dissolution of the metal surface of the steel mesh substrate. HCl reacted with the metal, causing metal ions to be released into the solution.

Secondly, the presence of HCl in the MacEtch solution resulted in the formation of metal chloride compounds. The metal ions released from the steel substrate reacted with HCl, forming metal chloride complexes in solution. Thirdly, the combination of H3PO4 and H2O2 in the MacEtch solution facilitated oxidation reactions on the steel surface. The metal ions released from the steel mesh can undergo oxidation, resulting in the formation of metal oxide compounds.

Furthermore, the MacEtch process, aided by the acidic solution and suspension of FeCl3.6H2O, lead to the removal of material from the steel mesh surface. This removal created irregularities and surface roughness, contributing to the desired re-entrant structure and enhanced surface area.

Finally, phosphoric acid (H3PO4) present in the etching solution also passivated the steel surface. It formed a thin, protective phosphate layer that inhibited further corrosion of the steel substrate, adding to the cause of self-cleaning.

Overall, the combination of an acidic etching solution and FeCl3.6H2O suspension over a steel mesh substrate resulted in the dissolution of metal, the formation of metal chlorides and oxides, surface roughening, and surface passivation. These processes and reactions were crucial for creating the desired re-entrant structure and enhancing the surface properties of the steel mesh, ultimately leading to improved superoleophobicity.

Figure 3.

Visually depiction of the hierarchical structure formed on the stainless steel mesh surface after the MacEtch process, showcasing the key characteristics that support the Cassie-Baxter state and contribute to the surface's superhydrophobic properties (a) MacEtch solution (b) Stainless steel substrate (c) 2D hierarchical structures (d) 3D hierarchical structures.

Figure 3.

Visually depiction of the hierarchical structure formed on the stainless steel mesh surface after the MacEtch process, showcasing the key characteristics that support the Cassie-Baxter state and contribute to the surface's superhydrophobic properties (a) MacEtch solution (b) Stainless steel substrate (c) 2D hierarchical structures (d) 3D hierarchical structures.

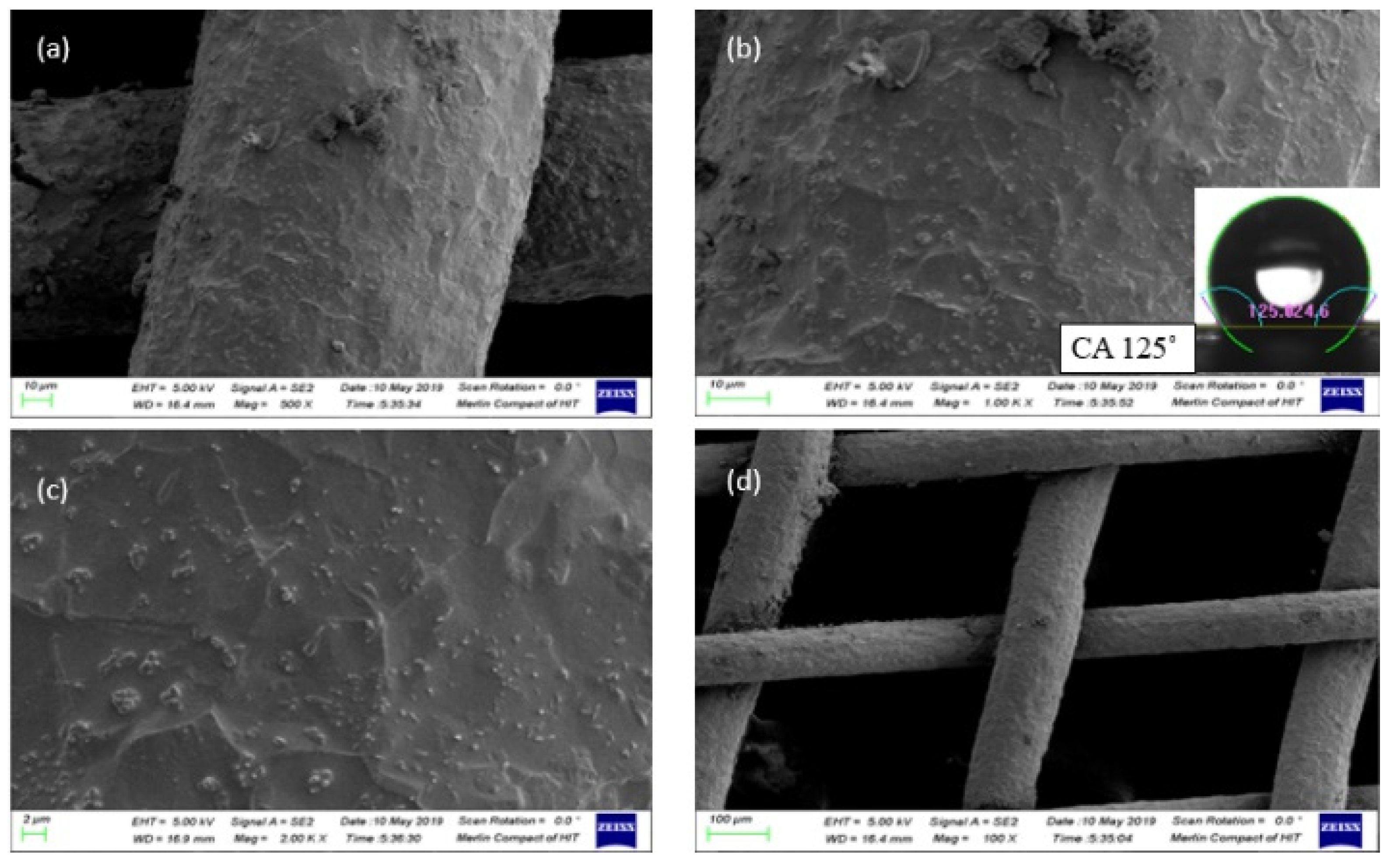

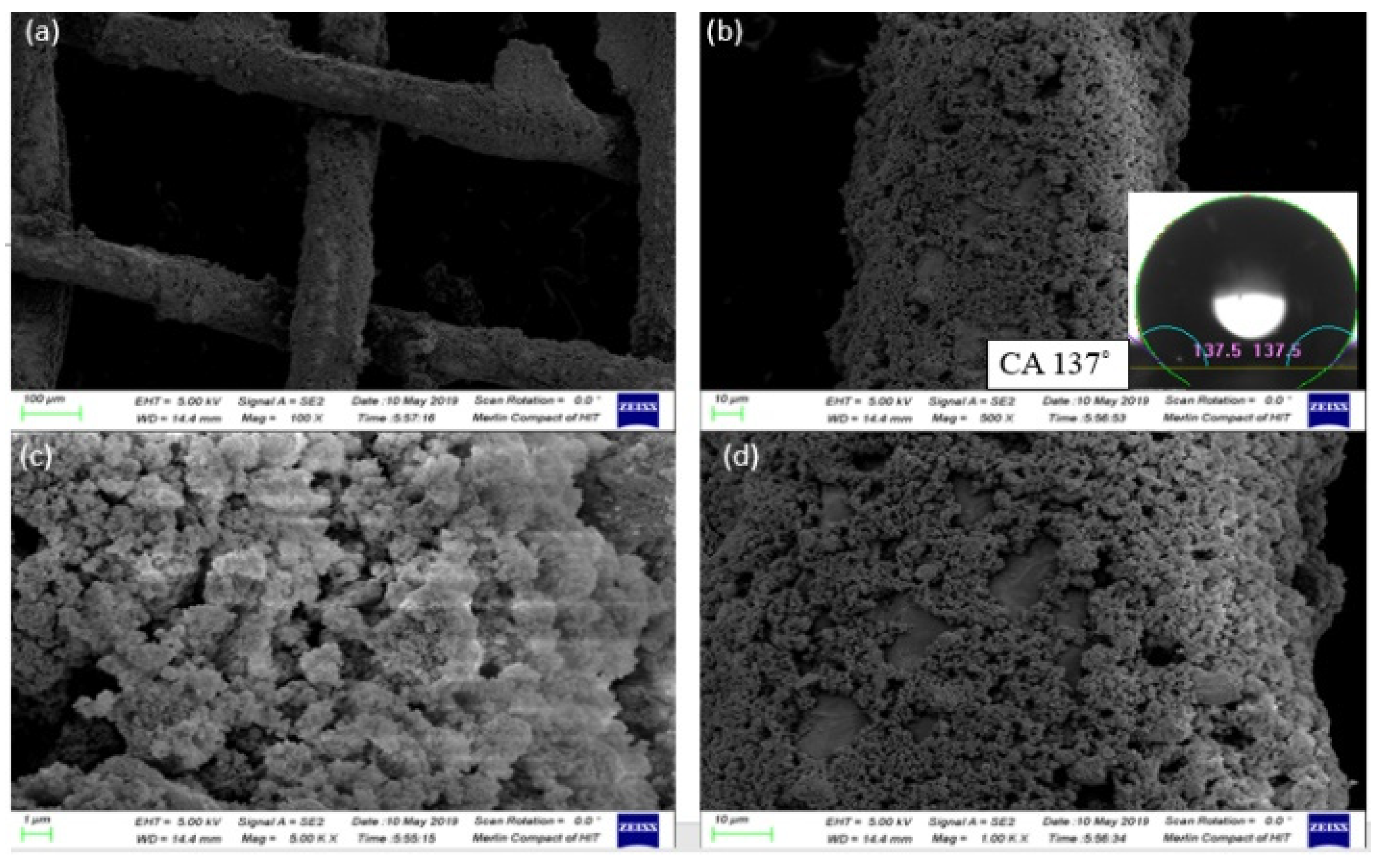

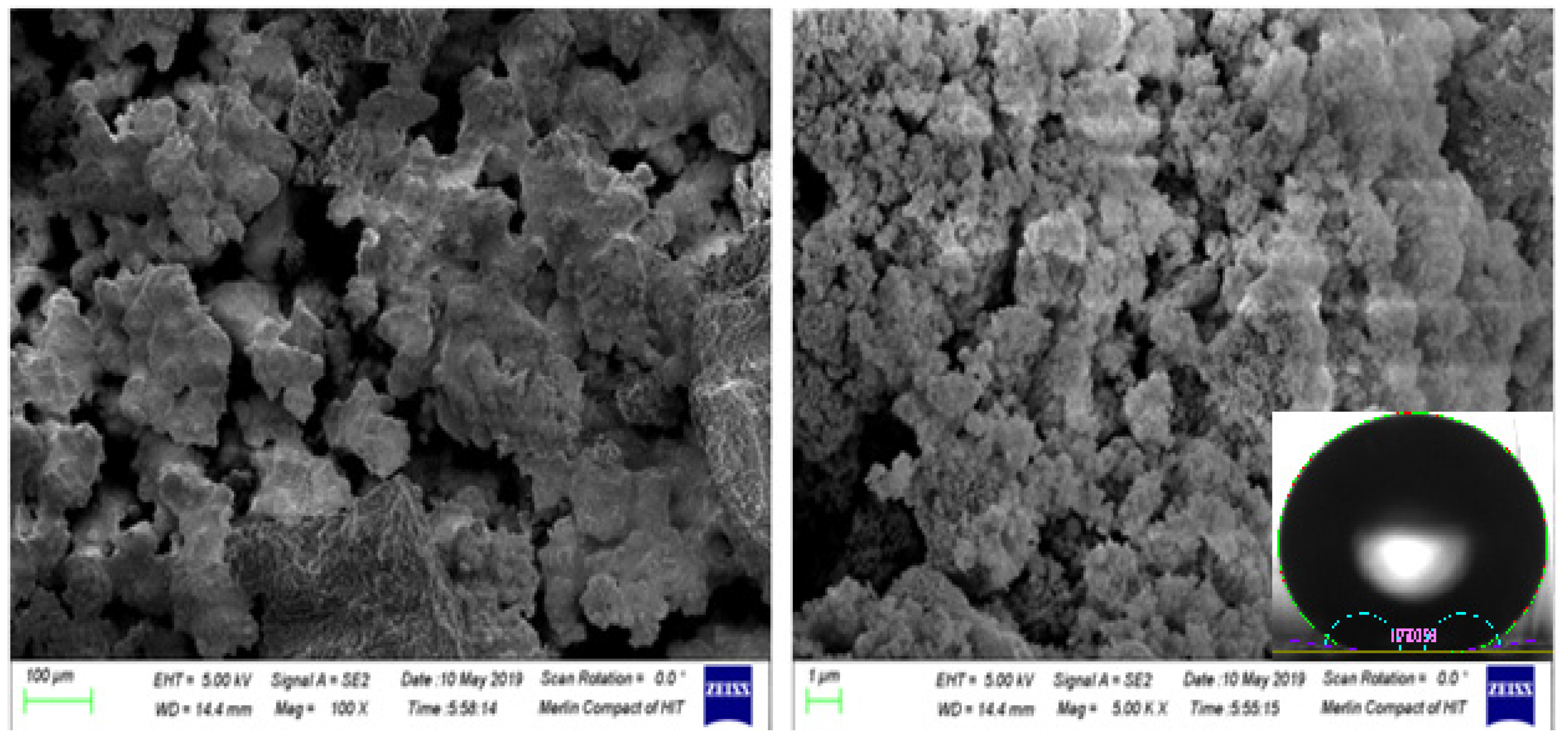

3.2. Surface Analysis via SEM:

Scanning electron microscopy SEM (ZEISS MERLIN Compact SEM) was used for topographical analysis. The specifications of SEM for analysis of the experiment are as follows. The scanning electron microscope magnification range was 100X-5000X. Its accelerating voltages were between 5-10kV since it had gold coating surface by metal sputter, and the resolution of the microscope varied from 1 µm to 100 µm. The sample size of the substrate for testing was 100 mm x 100 mm, and the samples were mounted at the height of 55 mm. The surface analysis from SEM is presented through

Figure 4 to Figure 6.

The metal-etched surface of the substrate was initially examined to evaluate the effect of MacEtch on surface roughness and contact angle. As shown in

Figure 4, the MacEtch process resulted in the development of a hierarchical structure, which significantly influenced the surface roughness and facilitated the formation of the Cassie-Baxter state. Consequently, the contact angle for water increased to 125º, indicating inherent hydrophobicity.

Figure 4.

Analysis of MacEtch prepared surface under SEM (a) Resolution value 500X (b) Resolution value 1KX (c) Resolution value 2KX (d) Resolution value 100X. This surface was assessed for contact angle with water. The output contact angle was little more than 125ᵒ.

Figure 4.

Analysis of MacEtch prepared surface under SEM (a) Resolution value 500X (b) Resolution value 1KX (c) Resolution value 2KX (d) Resolution value 100X. This surface was assessed for contact angle with water. The output contact angle was little more than 125ᵒ.

Following the MacEtch process, the stainless-steel mesh substrate was dip-coated in the PFOTES and SiO

2 solution for 60 minutes, and SEM analysis was performed to assess the contact angle and surface roughness.

Figure 5 illustrates the higher surface roughness observed, along with an increased contact angle, resulting in an overall improvement in water repellency. The contact angle rose to 137.5º, indicating enhanced water repellent properties.

To achieve superoleophobicity, the substrate underwent additional processes of dip coating and spray coating to deposit a higher concentration of hydrolyzed fluorides on the surface. This approach aimed to optimize both surface roughness and contact angle. As a result, the contact angle achieved in this methodology increased to 167° (

Figure 6), indicating a significant advancement towards superoleophobicity.

The SEM analysis provided valuable insights into the surface morphology, roughness, and contact angles of the fabricated surfaces. These findings confirm the successful development of hierarchical structures and the effectiveness of the coating techniques in enhancing the desired surface properties.

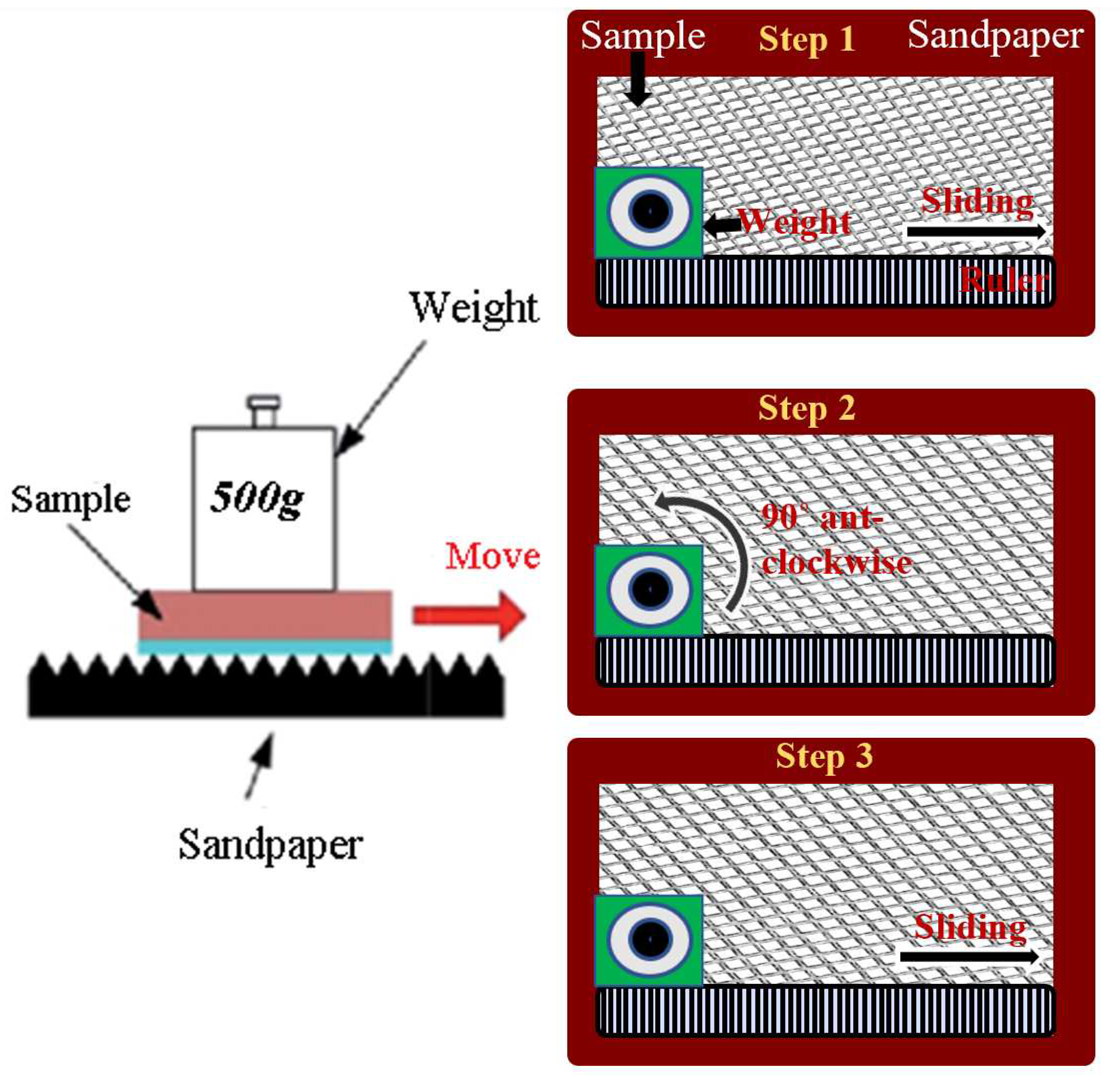

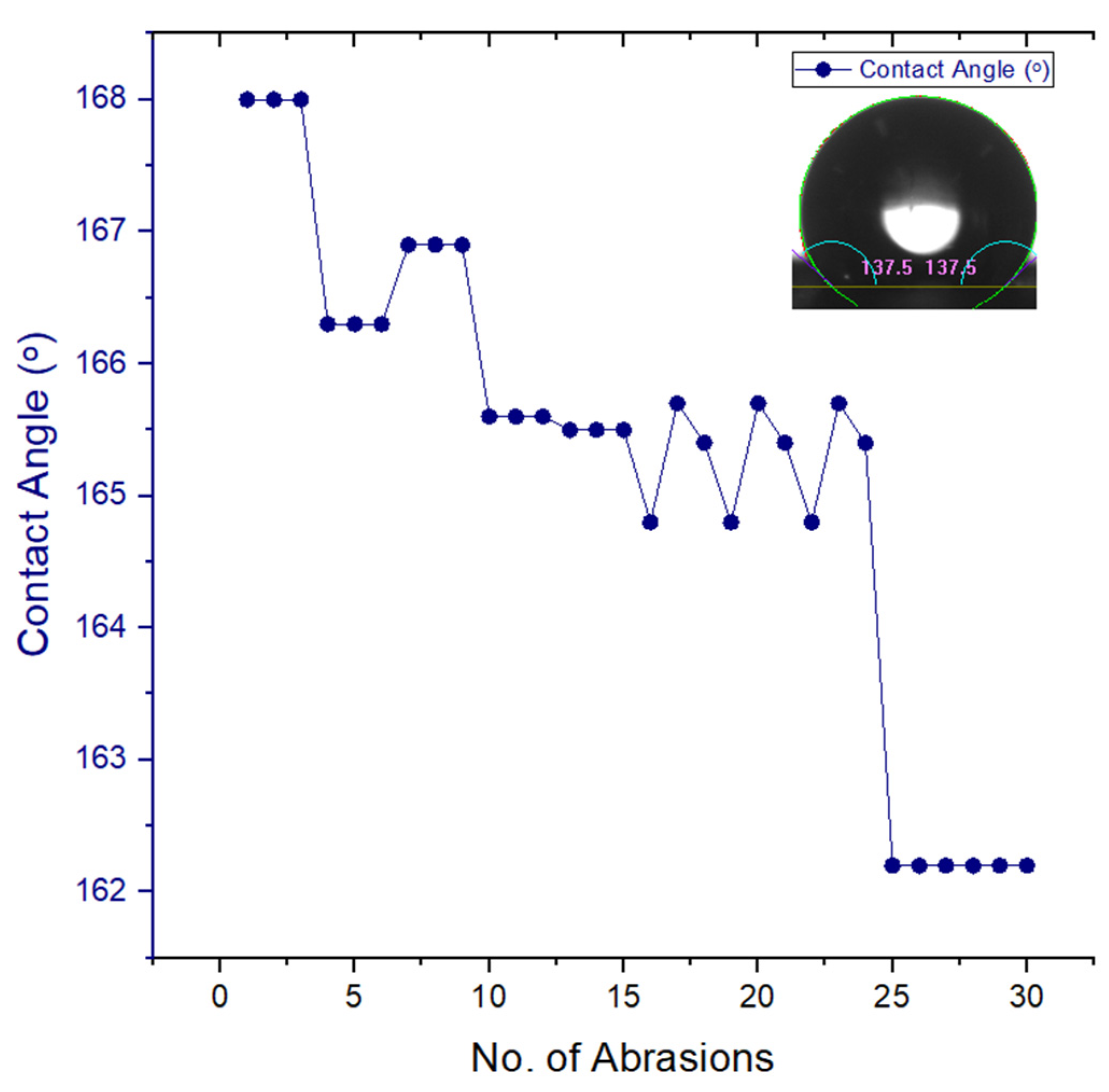

3.3. Wear Abrasion Testing:

For evaluating the mechanical durability, a wear abrasion test was conducted as depicted in (

Figure 7). The test involved placing weights on top of sandpaper, which was in direct contact with the fabricated surface. Weights ranging from 100g to 500g were used in 50g increments. Sandpaper with varying grit sizes, ranging from P10,000 to P600, was employed to induce mechanical wear and tear on the surface. The samples underwent cyclic loading for 30 minutes, and afterward, the contact angles were measured again. The contact angle measured after the cyclic loading were used to draw the graph in

Figure 8. The trend depicted in the

Figure 8 demonstrates the exceptional durability of the fabricated surface under wear and abrasion tests, effectively addressing the durability issues associated with superoleophobic surfaces, as outlined in the problem statement.

3.4. Contact angle Analysis via Goniometer:

Goniometer (Drop Meter Element A-60, 0.5 mm flat syringe tip) was used to analyze the contact angle values. For this texting procedure, 7µL droplet of testing liquids (deionized water and low surface tension oils, soybean and hexadecane) were placed on the substrate using a 0.5 mm flat syringe while mounted on the rotatable square platform. The contact angle was observed at ambient temperature.

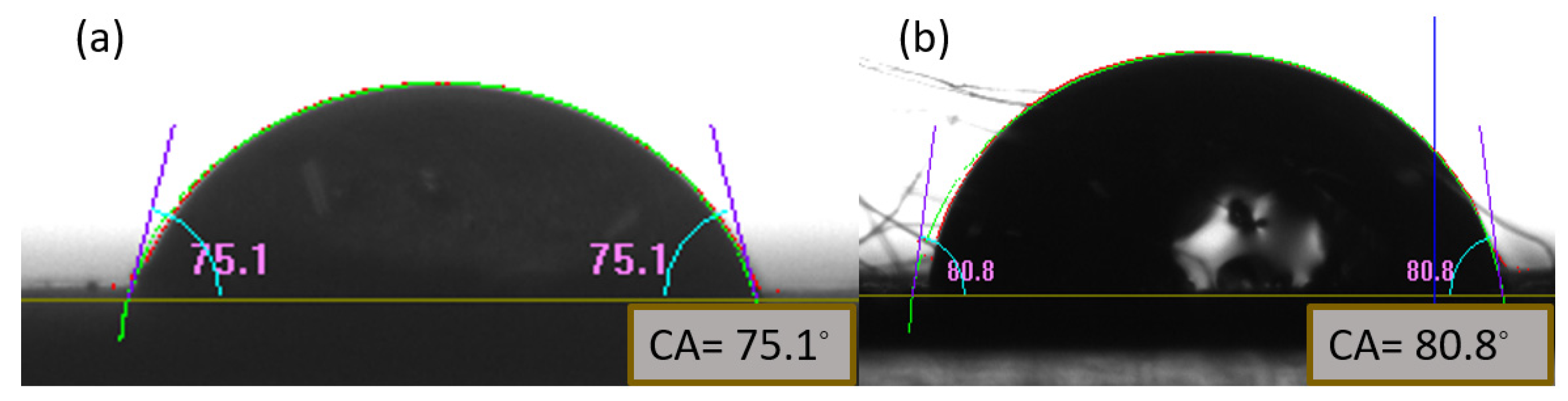

3.4.1. Cleaned, Dry and Untreated Surface Contact Angle:

Initially, the contact angles of water and hexadecane were observed on a clean and dry stainless-steel mesh substrate, yielding values of 80.8° and 75.1°, respectively. These measurements served as the baseline for further analysis, aiming to achieve contact angles above 150°(

Figure 9).

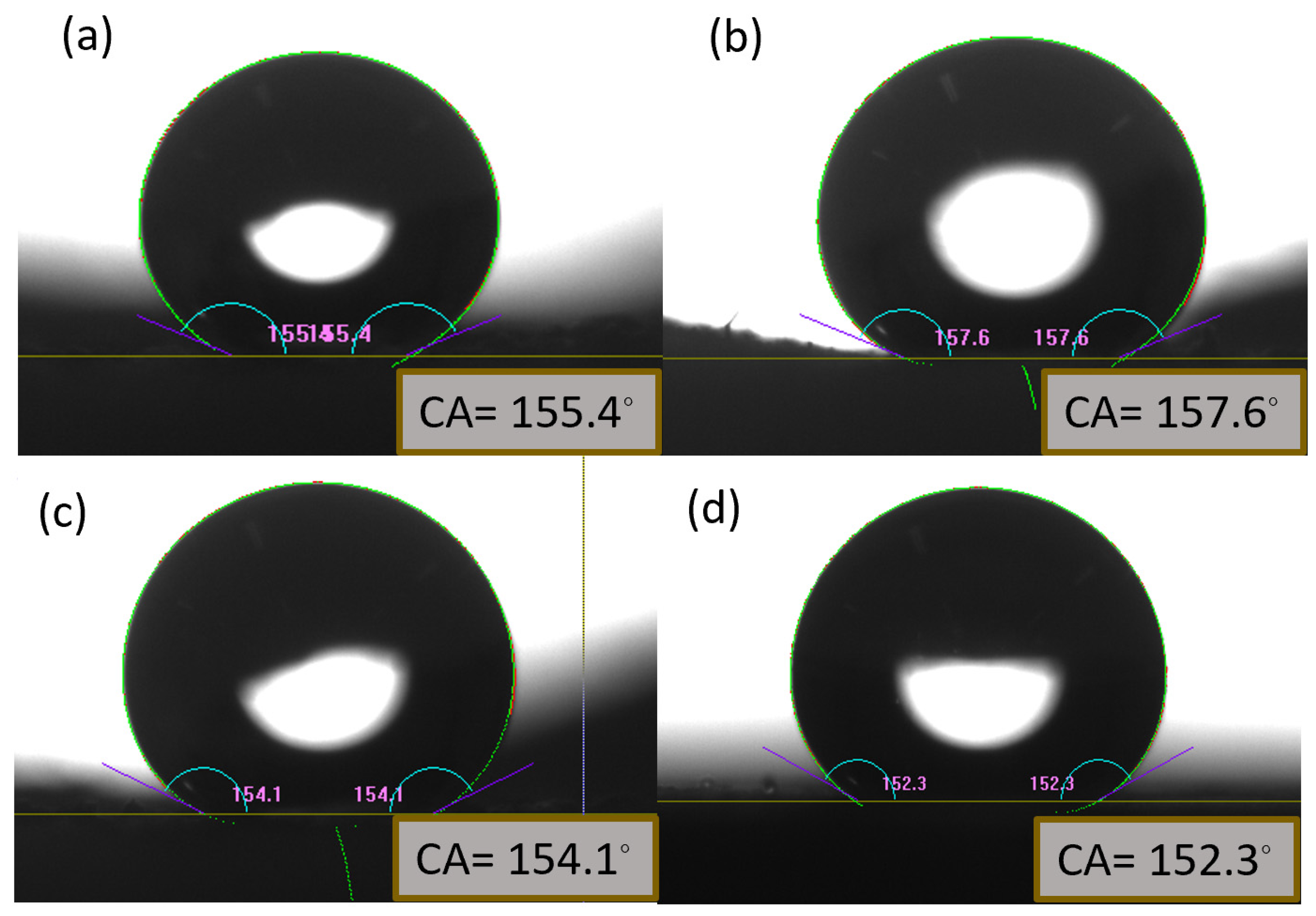

3.4.2. Superhydrophobic Surface Contact Angle:

To validate the superhydrophobicity of the treated surface, contact angle measurements were taken before and after conducting wear abrasion tests. The

Figure 10 presented in the results section demonstrates the mechanical durability of the surface, achieved through dip coating in the PFOTES and SiO2 solution for 60 minutes, on the steel mesh substrate.

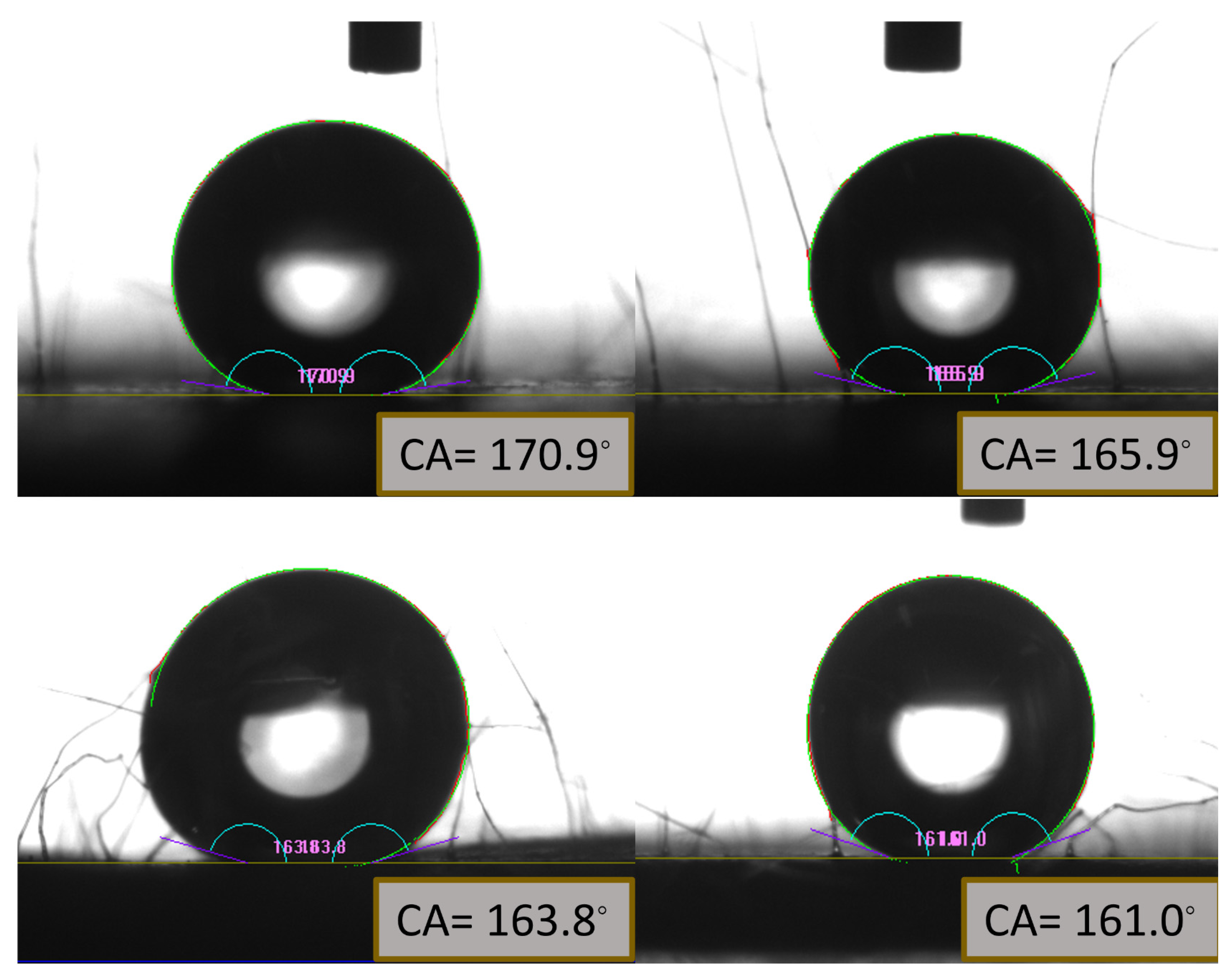

3.4.3. Superoleophobic Surface Contact Angle:

Similarly, contact angle measurements were performed before and after wear abrasion tests to assess the superoleophobicity of the treated surface. The

Figure 11 provided in the results section illustrates the mechanical durability of the surface achieved through a combination of dip coating and spray coating in the PFOTES and SiO2 solution for 60 minutes, applied to the steel mesh substrate. The obtained contact angles for hexadecane and soybean oil, prior to wear abrasion testing, were 170° and 163.8°, respectively. After the wear abrasion tests, the contact angles decreased to 165.9° and 161.0° for hexadecane and soybean oil, indicating a significant advancement towards achieving superoleophobicity.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study aimed to fabricate superhydrophobic and superoleophobic surfaces using a combination of chemical modification and surface coating techniques. The introduction highlighted the importance of such surfaces in various applications, including self-cleaning coatings, anti-fouling materials, and oil-repellent surfaces. The methodology involved the use of metal etching, dip coating, and spray coating processes to create hierarchical structures and deposit hydrophobic and hydrophobic coatings on stainless steel mesh substrates.

The results obtained from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis demonstrated the successful formation of hierarchical structures on the metal-etched surfaces. The SEM images revealed the presence of re-entrant structures, which are known to enhance surface roughness and promote superhydrophobicity and superoleophobicity. The contact angle measurements obtained through the goniometer analysis confirmed the hydrophobic and oleophobic nature of the fabricated surfaces. The contact angles for water and hexadecane on the cleaned and dry stainless-steel mesh were observed to be 80.8° and 75.1°, respectively, providing a baseline for further improvements.

The dip coating and spray coating processes using PFOTES and SiO2 solutions led to significant enhancements in surface properties. The contact angle measurements demonstrated a remarkable increase in contact angles, with values reaching 170° and 163.8° for hexadecane and soybean oil, respectively. These findings indicate the successful achievement of superoleophobic surfaces. The wear abrasion tests revealed the mechanical durability of the fabricated surfaces, as the contact angles remained relatively high even after exposure to cyclic loading and sandpaper abrasion.

Overall, the combination of metal etching, dip coating, and spray coating techniques proved to be effective in fabricating durable superhydrophobic and superoleophobic surfaces on stainless steel mesh substrates. The fabricated surfaces exhibited excellent repellence towards water and low surface tension oils, making them promising candidates for applications requiring self-cleaning, anti-fouling, and oil-repellent properties.

Future research can focus on further optimizing the fabrication process, exploring alternative materials, and investigating the long-term durability and performance of these surfaces under real-world conditions. Additionally, additional characterization techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) can provide valuable insights into the chemical composition and bonding mechanisms present on the fabricated surfaces.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the advancement of superhydrophobic and superoleophobic surface fabrication techniques, paving the way for their practical implementation in a wide range of industrial and everyday applications.

References

- M. Jin et al., "Superhydrophobic aligned polystyrene nanotube films with high adhesive force," Adv. Mater., vol. 17, no. 16, pp. 1977–1981, 2005. [CrossRef]

- F. Madidi, G. Momen, and M. Farzaneh, "Development of a stable TiO2 nanocomposite self-cleaning coating for outdoor applications," Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Brown and B. Bhushan, "Bioinspired, roughness-induced, water and oil super-philic and super-phobic coatings prepared by adaptable layer-by-layer technique," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, no. May, pp. 1–16, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Singh and J. K. Singh, "Fabrication of durable super-repellent surfaces on cotton fabric with liquids of varying surface tension: Low surface energy and high roughness," Appl. Surf. Sci., vol. 416, pp. 639–648, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Kleingartner, S. Srinivasan, Q. T. Truong, M. Sieber, R. E. Cohen, and G. H. McKinley, "Designing Robust Hierarchically Textured Oleophobic Fabrics," Langmuir, vol. 31, no. 48, pp. 13201–13213, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Yong, F. Chen, Q. Yang, J. Huo, and X. Hou, "Superoleophobic surfaces," Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 46, no. 14, pp. 4168–4217, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, Z. Wang, S. Huang, Y. Pan, and X. Zhao, "Flexible, Durable, and Unconditioned Superoleophobic/Superhydrophilic Surfaces for Controllable Transport and Oil–Water Separation," Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 28, no. 20, pp. 1–7, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Almilaji, "Fabricating Superhydrophobic and Superoleophobic Surfaces with Fabricating Superhydrophobic and Superoleophobic Surfaces with Multiscale Roughness Using Airbrush and Electrospray Multiscale Roughness Using Airbrush and Electrospray Downloaded from Downloa," Part Biol. Chem. Phys. Commons, Eng. Phys. Commons, 2016, [Online]. Available: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4460.

- P. S. Brown and B. Bhushan, "Mechanically durable, superoleophobic coatings prepared by layer-by-layer technique for anti-smudge and oil-water separation," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, pp. 1–9, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Zhang, Z. Cheng, T. Lv, L. Li, and Y. Liu, "The design of underwater superoleophobic Ni/NiO microstructures with tunable oil adhesion," Nanoscale, vol. 7, no. 45, pp. 19293–19299, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Zhang, Z. Cheng, T. Lv, Y. Qian, and Y. Liu, "Anti-corrosive hierarchical structured copper mesh film with superhydrophilicity and underwater low adhesive superoleophobicity for highly efficient oil-water separation," J. Mater. Chem. A, vol. 3, no. 25, pp. 13411–13417, 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Nuraje, W. S. Khan, Y. Lei, M. Ceylan, and R. Asmatulu, "Superhydrophobic electrospun nanofibers," J. Mater. Chem. A, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 1929–1946, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Meikandan and K. Malarmohan, "Fabrication of a superhydrophobic nanofibres by electrospinning," Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 11–17, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, L. Wang, H. Qian, and X. Li, "Superhydrophobic surfaces for corrosion protection: a review of recent progresses and future directions," J. Coatings Technol. Res., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 11–29, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, J. Fang, L. Wang, and W. Liu, "Fabrication of superhydrophobic copper by wet chemical reaction," Thin Solid Films, vol. 515, no. 18, pp. 7190–7194, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, W. Wang, L. Zhong, J. Wang, Q. Jiang, and X. Guo, "Superhydrophobic surface on pure magnesium substrate by wet chemical method," Appl. Surf. Sci., vol. 256, no. 12, pp. 3837–3840, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. Qian, S. Wang, X. Ye, and Z. Wu, "One-step hydrothermal synthesis method for the fabrication of superhydrophobic surface on magnesium alloy," AIP Conf. Proc., vol. 1794, no. January 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang et al., "A simple, one-step hydrothermal approach to durable and robust superparamagnetic, superhydrophobic and electromagnetic wave-absorbing wood," Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. July, pp. 2–11, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Puliyalil, G. Filipič, and U. Cvelbar, "Recent Advances in the Methods for Designing Superhydrophobic Surfaces," Surf. Energy, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, X. Xiao, Y. Shi, and C. Wan, "Fabrication of a superhydrophobic surface from porous polymer using phase separation," Appl. Surf. Sci., vol. 297, pp. 33–39, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Szczepanski, T. Darmanin, and F. Guittard, "Spontaneous, Phase-Separation Induced Surface Roughness: A New Method to Design Parahydrophobic Polymer Coatings with Rose Petal-like Morphology," ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 3063–3071, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Biria and I. D. Hosein, "Superhydrophobic Microporous Substrates via Photocuring: Coupling Optical Pattern Formation to Phase Separation for Process-Tunable Pore Architectures," ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 3094–3105, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Badv, I. H. Jaffer, J. I. Weitz, and T. F. Didar, "An omniphobic lubricant-infused coating produced by chemical vapor deposition of hydrophobic organosilanes attenuates clotting on catheter surfaces," Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, J. Deng, Y. Guo, W. Wang, R. Zhang, and J. Yu, "Fabrication of superhydrophobic cotton fabric by low-pressure plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition," Text. Res. J., vol. 89, no. 10, pp. 1853–1862, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Coclite, Y. Shi, and K. K. Gleason, "Superhydrophobic and oloephobic crystalline coatings by initiated Chemical Vapor Deposition," Phys. Procedia, vol. 46, no. Eurocvd 19, pp. 56–61, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Saini, K. Sautter, F. E. Hild, J. Pauley, and M. R. Linford, "Two-silane chemical vapor deposition treatment of polymer (nylon) and oxide surfaces that yields hydrophobic (and superhydrophobic), abrasion-resistant thin films," J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vacuum, Surfaces, Film., vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1224–1234, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Gleason, G. C. Rutledge, M. Gupta, M. Ma, and Y. Mao, "Superhydrophobic fibers produced by electrospinning and chemical vapor deposition.," U.S. Pat. Appl. Publ., p. 26pp., 2007.

Figure 1.

(a) Young's Equation (b) Wenzel State (c) Cassie-Baxter State (d) Hydrophobic Surface (Contact angle > 90°) (e) Hydrophobic Surface (Contact angle < 90°).

Figure 1.

(a) Young's Equation (b) Wenzel State (c) Cassie-Baxter State (d) Hydrophobic Surface (Contact angle > 90°) (e) Hydrophobic Surface (Contact angle < 90°).

Figure 2.

(a) Pictorial representation of the experimental methodology described to prepare superhydrophobic surface. The fluorate polymer contains amounts of fluoric group –CF2 and –CF3, leading to lower surface energy and low surface tension. (b) Triethoxy (1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluoro-1-octyl) silane structure.

Figure 2.

(a) Pictorial representation of the experimental methodology described to prepare superhydrophobic surface. The fluorate polymer contains amounts of fluoric group –CF2 and –CF3, leading to lower surface energy and low surface tension. (b) Triethoxy (1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluoro-1-octyl) silane structure.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Metal Etched and dip coated Surface under SEM (a) Resolution value 100X (b) Resolution value 500X (c) Resolution value 5KX (d) Resolution value 1KX. The surface was tested against water and the maximum contact angle observed was 137.5ᵒ.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Metal Etched and dip coated Surface under SEM (a) Resolution value 100X (b) Resolution value 500X (c) Resolution value 5KX (d) Resolution value 1KX. The surface was tested against water and the maximum contact angle observed was 137.5ᵒ.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Spray coated, and Dip coated substrate after Metal Etched Prepared Surface under SEM (a) Resolution Value 100X (b) Resolution Value 5KX. The surface was tested against hexadecane and soybean oils and the maximum repeatable contact angle observed was 167ᵒ.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Spray coated, and Dip coated substrate after Metal Etched Prepared Surface under SEM (a) Resolution Value 100X (b) Resolution Value 5KX. The surface was tested against hexadecane and soybean oils and the maximum repeatable contact angle observed was 167ᵒ.

Figure 7.

Schematics of wear abrasion test. The sliding weight includes both horizontal and vertical placement of the substrate.

Figure 7.

Schematics of wear abrasion test. The sliding weight includes both horizontal and vertical placement of the substrate.

Figure 8.

Wear and Abrasion Test for steel mesh with 500g weight P10,000 sandpaper for 10 cm distance. Testing material includes low surface tension materials, hexadecane. The contact angle stays above the 150º line after the testing which displays the higher mechanical durability of surface manufactured.

Figure 8.

Wear and Abrasion Test for steel mesh with 500g weight P10,000 sandpaper for 10 cm distance. Testing material includes low surface tension materials, hexadecane. The contact angle stays above the 150º line after the testing which displays the higher mechanical durability of surface manufactured.

Figure 9.

Measurement of Contact angle of (a)Hexadecane (b) water on stainless steel mesh surface. The low surface tension materials used during testing procedure include hexadecane and soybean oil.

Figure 9.

Measurement of Contact angle of (a)Hexadecane (b) water on stainless steel mesh surface. The low surface tension materials used during testing procedure include hexadecane and soybean oil.

Figure 10.

Measurement of contact angle of water on the fabricated water-repellent surface. Right after drying out the surface water contact angle is (a) 155.4ᵒ (b)157.6ᵒ. After wear abrasion test (c)154.1ᵒ (d)152.3ᵒ on stainless steel mesh surface. All of the images represent more than 150ᵒ before and after testing process proving durability of fabricated superhydrophobic surface.

Figure 10.

Measurement of contact angle of water on the fabricated water-repellent surface. Right after drying out the surface water contact angle is (a) 155.4ᵒ (b)157.6ᵒ. After wear abrasion test (c)154.1ᵒ (d)152.3ᵒ on stainless steel mesh surface. All of the images represent more than 150ᵒ before and after testing process proving durability of fabricated superhydrophobic surface.

Figure 11.

Measurement of contact angle of hexadecane and soybean oil on the fabricated oil-repellent surface on stainless steel mesh substrate. The oil contact angle for hexadecane (a) before and (b) after wear abrasion testing. For soybean oil contact angle (c)before and (d)after wear abrasion testing. All of the images represent more than 150ᵒ before and after testing process proving durability of fabricated superoleophobic surface.

Figure 11.

Measurement of contact angle of hexadecane and soybean oil on the fabricated oil-repellent surface on stainless steel mesh substrate. The oil contact angle for hexadecane (a) before and (b) after wear abrasion testing. For soybean oil contact angle (c)before and (d)after wear abrasion testing. All of the images represent more than 150ᵒ before and after testing process proving durability of fabricated superoleophobic surface.

Table 1.

Summary of Contact angle for different amounts of Silicon Dioxide and different Oils used for testing.

Table 1.

Summary of Contact angle for different amounts of Silicon Dioxide and different Oils used for testing.

|

Organic Solvent

|

Co-polymer

(alkylflourosilane)

|

Nanoparticles (SiO2)

|

Contact angle for

Soybean oil

|

Contact angle for

Hexadecane

|

|

Ethanol

|

C8H4Cl3F13Si |

1g |

137ᵒ |

148ᵒ |

|

Ethanol

|

C8H4Cl3F13Si |

2g |

155ᵒ |

160ᵒ |

|

Ethanol

|

C8H4Cl3F13Si |

3g |

161ᵒ |

170ᵒ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).