I. Introduction

This paper is the fifth in the series [

1,

2,

3,

4], devoted to a systematic exposition of the dynamics of a rigid body, considered as a system with kinematic constraints. In the previous works has been considered the dynamics of a free asymmetric body. Here we revise the problem of the motion of inclined heavy symmetric top with one fixed point.

Free asymmetric body. The evolution of a free rigid body in the center-of-mass system can be described by

Euler-Poisson equations [

1]

Here the functions

are components of angular velocity in the body, and

is orthogonal

-matrix. Given the solution

, the evolution of the body’s point

is restored according to the rule:

, where

is the initial position of the point. Due to this, the problem (

1) should be solved with the universal initial conditions:

,

. The solutions with other initial conditions are not related to the motions of a rigid body

1. Both columns and rows of the matrix

have a geometric interpretation. The columns

form an orthonormal basis rigidly connected to the body. The initial conditions imply that at

these columns coincide with the basis vectors

of the Laboratory system. The rows,

, represent the laboratory basis vectors

in the body-fixed basis. For example, the functions

are components of

in the basis

.

By

I in Eq. (

1) was denoted the inertia tensor. For the body considered as a system of

n particles with coordinates

and masses

,

, it is a numeric

-matrix defined as follows:

Generally,

is nondegenerate symmetric matrix transforming as the second-rank tensor under rotations of the Laboratory system. This can be used to simplify Eqs. (

1), assuming that at the instant

the Laboratory axes

have been chosen in the direction of eigenvectors of the matrix

. Then the inertia tensor in Eqs. (

1) has diagonal form:

. The initial conditions imply that the axes

of body-fixed basis at

also coincide with the inertia axes. Since these two systems of axes are rigidly connected with the body, they will coincide in all future moments of time.

Let’s consider an asymmetric rigid body, that is (

), and suppose that we describe it using the equations (

1), in which the inertia tensor is chosen to be diagonal. This implies that the position of the Laboratory system is completely fixed, as described above. As will be seen further, it is precisely this circumstance that is not taken into account in textbooks when formulating the equations of heavy symmetric top and solving them.

Heavy symmetric body with a fixed point. Let’s consider a rigid body with one fixed point. It is known [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] that by placing the origin of the Laboratory system at this point, we arrive at the same equations (

1) and (

2). Further, let the body is subject to the force of gravity, with the acceleration of gravity equal to

and directed opposite to the constant unit vector

, see

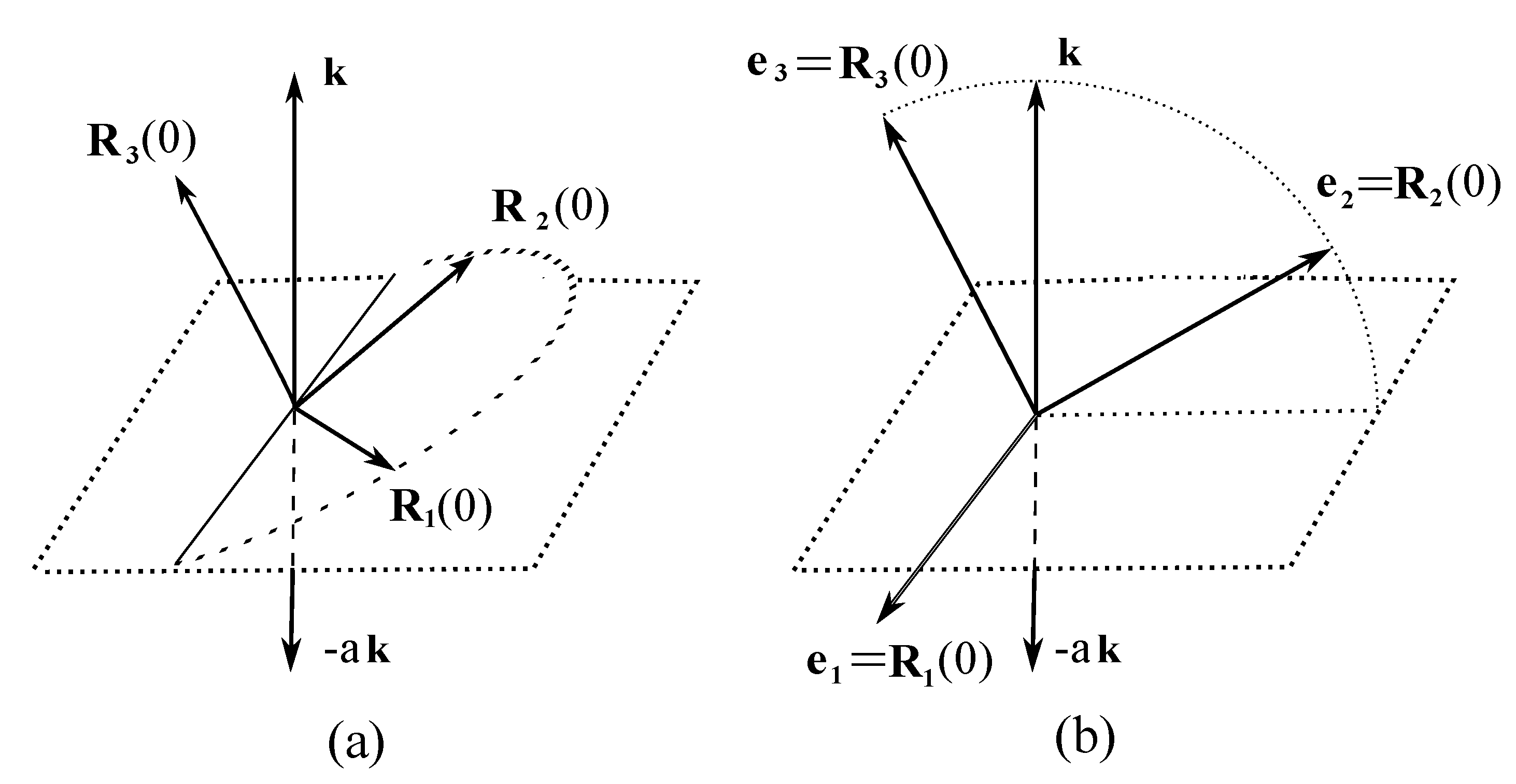

Figure 1a. Then the potential energy of the body’s particle

is

. Summing up the potential energies of the body’s points, we get the total energy

. Here

,

L is the distance from the center of mass to the fixed point,

is the total mass of the body and

is unit vector in the direction of center of mass at

. The potential energy give rise to the torque of gravity in the equations of motion, which read now as follows:

Let the initial position of the inertia axes

of the body be as shown in

Figure 1a. Assuming that the Laboratory axes

have been chosen in the direction of the inertia axes, the matrix

I in Eq. (

3) acquires the diagonal form. Let us denote components of the vector

in this basis as

.

If our body is a symmetric, that is

, our equations can be simplified as follows. Without loss of generality, we can assume that the vector

has the following form:

. Indeed, the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the inertia tensor

I obey the relations

. With

we have

and

, then any linear combination

also represents an eigenvector with eigenvalue

. This means that we are free to choose any two orthogonal axes on the plane

as the inertia axes. Hence, in the case

we can rotate the Laboratory axes in the plane

without breaking the diagonal form of the inertia tensor. Using this freedom, we can assume that

for our problem, see

Figure 1(b).

Symmetric (Lagrange) top. Let’s consider the symmetric body,

, and assume that its center of mass lies on the axis of inertia

. This body is called the symmetric (or Lagrange) top [

9]. This allows further simplify the equations of motion, since by construction

.

With these

and

, the potential energy acquires the form

. Using these

and

in Eqs. (

3), we get the final form of equations of motion of a heavy symmetric top for the variables

and

. To compare them with those given in textbooks, we rewrite our equations in terms of Euler angles

2

They follow as the conditions of extremum of the following Lagrangian:

In the textbooks, equations of motion of the heavy symmetric top follow from a different Lagrangian, the latter does not contain the term proportional to

[

9]

This term is discarded on the base of the following reasoning: to simplify the analysis, choose the Laboratory axis

in the direction of the vector

... . However, this reasoning does not take into account the presence in the equations of moments of inertia, which have the tensor law of transformation under rotations. Indeed, going back to Eqs. (

3), select

in

Figure 1(b) in the direction of

, and calculate the components of the inertia tensor. Since the axis of inertia

does not coincide with

, we obtain a symmetric matrix instead of a diagonal one, which should now be used in the equations of motion. That is, the attempt to simplify the potential energy leads to a Lagrangian with a complicated expression for the kinetic energy.

Thus, it seems to be necessary to revise the problem of the motion of a heavy symmetric top and correct this drawback.

II. Integrability in quadratures according to Liouville.

Effective Lagrangian with two degrees of freedom. Eq. (

4) states that

is the integral of motion of the theory (

7). Besides, the variable

does not enter into the remaining equations () and (). So we can look for the effective Lagrangian that implies the equations () and () for the variables

and

. This is as follows:

where

is considered as a constant. To apply the Liouville’s theorem, we need to rewrite the effective theory in the Hamiltonian formalism. Introducing the conjugate momenta

and

for the configuration-space variables

and

, we get

The Hamiltonian of the system is constructed according the standard rule:

. Its explicit form is as follows:

where it was denoted

The Hamiltonian equations can be obtained now according the standard rule: , where z is any one of the phase-space variables, and the nonvanishing Poisson brackets are , .

The effective theory admits two integrals of motion. They are the energy

and the projection of angular momentum on the direction of vector

The preservation in time of

can be verified by direct calculation

3. The remarcable property of the integrals of motion is that they have vanishing Poisson bracket,

, as it can be confirmed by direct calculation. Accoding to the Liouville’s theorem [

9,

10], this implies that a general solution to the equations of motion can be found in quadratures (that is calculating integrals of some known functions and doing the algebraic operations). Our aim now will be to present the explicit form of the integrals in question.

According to the algorithm used in the proof of Liouville’s theorem [

10], we need to resolve Eqs. (

13), (

14) with respect to

and

. Using the identities

we get the solution

where

. Next we need to integrate these functions along any curve connecting the origin of configuration space with a point

. Taking the curve to be a pair of intervals,

, we obtain the following function

Then the general solution to the equations of motion of the theory (

9) is obtained resolving Eqs. (

16) together with the equations

,

with respect to the phase-space variables

. Using (

18), the last two equations read as follows:

Calculating the partial derivatives indicated in these integrals, we get

These are elliptic integrals over the indicated integration variables.