FERRITIN: MORE THAN JUST AN IRON-STORAGE PROTEIN

Ferritin is traditionally considered an iron-binding protein, being strongly involved in iron homeostasis and in the physiology of iron metabolism(1), along with other molecules, such as transferrin, ferroportin and hepcidin. This particular molecule has fundamental roles in the storage of iron in a biological available form, which is essential for a variety of physiological cellular processes, whilst ensuring the structural and functional protection of proteins, lipids and also of DNA from the well-documented toxicity of this metal element. However, ferritin is also involved in several pathophysiological mechanisms of a wide range of pathological conditions, such as infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic diseases(2).

General functional roles of ferritin

Ferritin is essentially an intracellular iron-storage protein found in all multicellular organisms and synthesized in multiple cells, its biochemical structure and biological properties being well conserved through species. This molecule presents itself either as apoferritin, which is defined as the iron-free ferritin (the protein shell), or as holoferritin(3), which results from the chemical binding of apoferritin to the iron (Fe) element in its +3 oxidation state, known as the ferric cation: Fe3+. Apoferritin is comprised of a number of 24 polypeptide subunits or chains, some of them being of light (L) molecular weight (19 kilodaltons) and others being of heavy (H) molecular weight (21 kilodaltons). Therefore, apoferritin consists of two kinds of polypeptide subunits, called L-subunits or L-ferritin (FTL) and H-subunits or H-ferritin (FTH), respectively(3, 4). It should be noted that, the ratio of FTH to FTL varies widely, depending on the type of tissue in which it is expressed, but also on the functional status of the cell in which ferritin is synthesized; studies have shown that FTL are predominant in tissues such as the liver and spleen, whereas FTH are predominant in the heart and kidneys(4).

The amount of cytosolic ferritin is molecularly regulated by the translational process of H- and L-ferritin messenger RNAs (mRNAs), in direct response to a cytoplasmic pool of chelatable or labile Fe, which binds to apoferritin. Moreover, according to an old study from 2002, the intracellular biosynthesis of ferritin is also modulated by various cytokines at different levels: transcriptional, post-transcriptional and translational, during embryogenesis, cellular differentiation, proliferation and inflammatory phenomena(5). The same study has shown that the expression of ferritin may be enhanced by other factors as well, such as increased oxidative stress, the activity of thyroid hormones, various growth factors and secondary messengers, hypoxia-ischemia phenomena and hyperoxia(5).

Each apoferritin molecule has the capacity to bind up to 4500 Fe3+(6). As mentioned above, at the intracellular level there are free iron elements described in a labile pool; these free forms of iron are biologically active in cellular metabolism, although excesive amounts of these forms may generate cytotoxicity, which is detrimental to the physiology and structural integrity of the cell. By sequestering iron, ferritin is directly involved in iron homeostasis; through their ferroxidase activity, H-subunits of ferritin transform the toxic ferrous cation (Fe2+) into ferric cation (Fe3+), which is essentially less toxic to the cell(7).

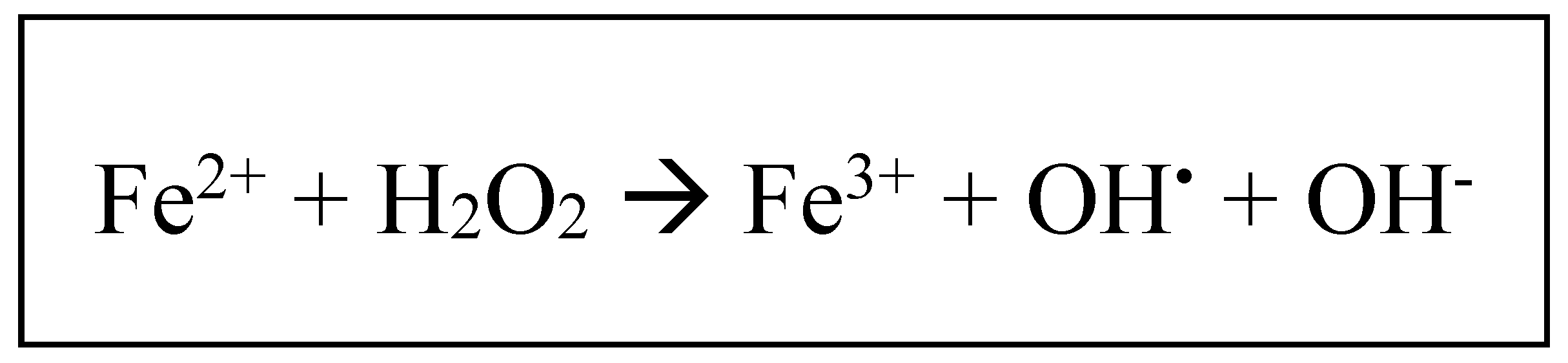

The physiological roles of ferritin are well documented, as this molecule is an essential molecular component of iron homeostasis and metabolism, along with transferrin, defined as the major iron-binding serum protein transporter. Due to its high toxicity, iron, after being transported by serum transferrin at the cellular level, once present within the intracellular environment, is biochemically associated with various cytosolic proteins, such as poly-(rC)-binding protein-1(8), which operates as a cytosolic chaperone involved in the delivery of iron to intracellular ferritin. Within the molecular structure of ferritin, Fe2+ is converted to Fe3+, due to the feroxidase activity of FTH, hence iron being stored in its ferric form, associated with hydroxide and phosphate anions(5). The biochemical conversion of Fe2+ to Fe3+ is an essential part of iron homeostasis, as it limits the deleterious reaction which may occur between Fe2+ and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) molecules, known as the Fenton reaction (Fig. 1), which may increase the intracellular levels of a highly cytotoxic reactive radical, represented by the hydroxyl radical (HO-)(9). Hence, the fundamental physiological role of ferritin is reflected in its capacity to store iron intracellularly in a non-toxic and biologically available form.

Figure 1.

The Fenton redox reaction: ferrous iron (Fe2+) reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), resulting in ferric iron (Fe3+), hydroxil radical (OH.) and hydroxide anion (OH-).

Figure 1.

The Fenton redox reaction: ferrous iron (Fe2+) reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), resulting in ferric iron (Fe3+), hydroxil radical (OH.) and hydroxide anion (OH-).

Although ferritin is mainly described at the intracellular level, operating as an iron-storage protein and having important roles in the physiology of iron metabolism, this molecule is also found in the serum

(10); however, under physiological conditions, its serum levels are clinically insignificant, whereas elevated serum levels of ferritin may suggest the presence of an underlying pathological condition, such as inflammatory syndromes with multiple etiologies or genetic and transfusion iron-overload diseases

(11), hemochromatosis being the most well studied. According to one source

(12), the normal values of serum ferritin, measured in nanograms per mililiter (ng/mL), may vary depending on sex and age (

Table 1).

Although the exact mechanisms by which ferritin is secreted into the bloodstream remain elusive, serum ferritin is frequently used in medical practice. In contrast to intracellular ferritin, serum ferritin is iron-poor, having only a fraction of the iron of the intracellular ferritin. According to ten Kate et al., in a study from 2001 regarding iron saturation of serum ferritin in patients diagnosed with AOSD, serum ferritin described in patients with iron-overload associated conditions may have as little as 2% of the iron content of the intracellular form of ferritin(13). Interestingly, according to an old study from 1979, except for terminal stages of chronic liver disease (for example, end-stage cirrhosis), the increased levels of serum ferritin cannot be associated with cell damage or necrosis, as the usual markers of necrosis, such as cytoplasmic enzymes, are not present in the plasma when serum ferritin levels are increased(14).

In clinical settings, serum ferritin is frequently used in differential diagnosis of anemia, but also as an essential indicator for multiple pathological conditions, including hereditary hemochromatosis, numerous inflammatory syndromes (infections, autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases), neurodegenerative disease and malignant processes(2, 3, 15), with macrophages being considered the main cellular source of serum ferritin in mice(14, 16, 17, 18). Studies in cellular and molecular biology have shown that the majority of proteins biosynthesized in eukaryotic cells, including ferritin, are secreted into the serum using the classical secretion pathway, which is comprised of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus(19, 20). Further studies proved that serum ferritin is mainly secreted by macrophages, its secretion being regulated by at least one non-classical pathway, which uses secretory lysosomes(16) and the interraction with the nuclear receptor coactivator-4 (NCOA4), a selective autophagy receptor, which may also mediate the entry of ferritin into the lysosomes for degradation. Furthermore, it has been proved that NCOA4 has increased intracellular levels when cellular iron levels are decreased, whereas serum ferritin levels are elevated when the systemic levels of iron are high(21, 22). However, the experimental knockdown of NCOA4 generated the increased secretion of ferritin from monocytic cells and macrophages, suggesting that other secretion pathways, including the ER-Golgi apparatus, may be involved in the cellular secretion process of ferritin; a potential NCOA4-independent secretory autophagy pathway has been described for both ferritin and interleukin-1β (IL-1β)(23) – one of the most important proinflammatory cytokines, along with tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6 and type I interferon (IFN). Further investigations concerning the biological mechanisms by which ferritin is secreted into the plasma should be performed.

Serum ferritin is currently considered, along with C reactive protein, fibrinogen and procalcitonin, an important acute phase reactant, its levels being increased during the course of inflammatory processes(24) and reflecting the degree of acute and chronic inflammation in various infectious, rheumatic, hematologic or malignant diseases, as it was experimentally proved that cultured cells released ferritin into surrounding environment when grown in the presence of IL-1β and TNF-α(24). Hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, proximal tubular renal cells and other tissue macrophages are strongly involved in the secretion of extracellular ferritin(16, 25, 26). Noteworthy is that some studies suggest that serum ferritin is mainly represented by L-subunits (FTL or L-ferritin)(5, 16, 25), which are N-glycosylated, secondary to a post-translational process that occurs at the level of the Golgi apparatus(27). Interestingly, the glycosylated fraction of serum ferritin was proved to be approximately 50% under normal conditions, although there are studies that have shown that in patients with AOSD glycosylated FTL is ≤20%(28, 29, 30, 31). Such decreases in the glycosylation fraction were also described during the course of various hemophagocytic syndromes(32, 33, 34), drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions(35, 36) and severe infections(33). The hypothesized mechanisms underlying the decreased glycosylated fraction of FTL include saturation of the normal glycosylation mechanisms within the cell(29). Worwood et al. showed in 1979 that hepatic injury and subsequent hepatocytolysis determined decreased glycosylation in the biochemical structure of serum ferritin(37), similar molecular modifications being observed in the setting of tumor lysis syndrome and various hematologic malignancies(38, 39).

As mentioned above, serum ferritin is iron-poor, which suggests that this molecule has a role beyond its involvement in iron sequestration for the plasma variant(40). Although it is highly unlikely that macrophages are the sole cellular sources of serum ferritin, there are evidence to support their fundamental role for its extracellular secretion; macrophage-mediated ferritin secretion has been proved to be directly connected with various human pathological conditions associated with inflammatory syndromes, as active secretion of ferritin by macrophages was decribed in the recovered bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the course of smoking-induced lung inflammation(41). Moreover, serum levels of CD163 (soluble CD163 or sCD163), an immunological marker of activated macrophages, are correlated with serum levels of ferritin in individuals diagnosed with AOSD and septic shock(42).

Although the exact functions of FTL remain to be established through future thorough investigations, there are studies suggesting that the L-subunits of ferritin have important roles in iron-binding in the plasma, but it may also manifest stimulatory effects on cellular proliferation, independent of iron availability(43).

Studies performed in the course of the last approximately 15 years suggest that ferritin may also operate as a bioactive mediator or as a signaling molecule, which, consequently, explains the existence of specific receptors expressed by various cells. Both FTL and FTH operate on particular cell surface receptors; hepatocytes express receptors which bind both FTL and FTH, while receptors expressed by other tissues show high afinity for FTH(44).

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-2 (TIM-2), a molecular member of the T-cell TIM gene family involved in the regulation of immune responses, has been described as the receptor for FTH endocytosis, being expressed by B and T cells, hepatocytes and nephrocytes(26, 45). Another identified cell surface receptor for ferritin is represented by Scara-5, defined as a scavenger receptor involved in binding various ligands; however, Scara-5, in contrast to TIM-2, mediates the preferential binding of FTL(46).

Serum increase of FTH during infectious processes

It appears that FTH expresses important roles during infections and, thus, during inflammation. It is well-known that iron is an important metabolic element necessary for the growth of various pathogenic agents, especially bacteria. Studies have proven that the increase in serum ferritin has the ability to limit the iron availability to various pathogenic agents during the course of an infectious process(47, 48, 49), thus restricting bacterial growth and the progression of the infection. This explains the high mortality rate in individuals who are diagnosed with a particular infectious disease who are given iron supplementation(50). Furthermore, it should be noted that in patients who express high pathogen loads there is a decrease in systemic iron levels, a state defined as hypoferremia, and elevated serum ferritin (hyperferritinemia)(51). According to a study performed by Alvarez-Hernádez et al., the aforementioned biological modifications during infectious processes may be generated experimentally by the injection with IL-1α or TNF-α, these proinflammatory cytokines having well documented effects on macrophage iron uptake, storage, but also on recirculation(52). The M1-macrophages, a potent proinflammatory phenotype of macrophages, possess essential roles in this regard, following their treatment with IFN-γ: the activity of iron-regulatory protein-1 and -2 (IRP-1 and IRP-2, respectively) is decreased, which determines the increase in FTH expression at the intracellular level; there is also an increase in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α(53, 54). Similar observations were made by Seifert et al., showing that there is an increase in macrophage biosynthesis of FTH in the presence of non-self agents, which not only limits the availability of iron to the pathogens, but also decreasing the intensity of the local oxidative stress during inflammation(55).

The intracellular mechanisms of ferritin biosynthesis are, as it was described, responsive to the effects of various proinflammatory cytokines, influencing both the transcriptional and the translational phases in different cells, such as hepatocytes, circulating monocytes and tissue macrophages(25, 56, 57). Fibroblasts who were exposed to various concentrations of TNF-α and IL-1α were shown to have an increase in FTH expression, by influencing the molecular activity of the NF-ҡB signaling pathway(56, 58, 59), while IL-1β induced an increase in the expression of FTH in hepatocytes, by binding to an enhancer region 70 bp from the start of the codon(60, 61).

The aforementioned functional roles of ferritin during infections prove that the increase in serum ferritin (FTH) represents an important host defense mechanism, which limits bacterial growth through iron deprivation.

The immunomodulatory roles of ferritin

While ferritin is a classic iron-binding protein, which is involved in human iron metabolism, and an important acute phase reactant along with C reactive protein and fibrinogen, there are currently multiple studies which focus on more complex functional roles that this particular molecule may possess in human pathology, some of which are yet to be unraveled.

1.1. The proinflammatory activity of ferritin

There are studies which suggest that ferritin may functionally manifest itself as a proinflammatory cytokine in certain hyperinflammatory states, thus postulating a direct causal role for ferritin in mediating inflammatory conditions. According to a study published in 2009 by Ruddell et al., which focused on experimentally activated hepatic stellate cells, FTH exhibits important immunoinflammatory properties, similar to those expressed by certain proinflammatory cytokines. FTH interacts with, and binds to, the TIM-2 receptor, which, at the intracellular level, activates mitogen-activated protein-kinase (MAPK)-induced NF-ҡB through an iron-independent mechanism, leading to an increase in mRNA and protein expression of multiple proinflammatory molecules, which include IL-1β (which was proven to be increased 50-fold), a 100-fold increase in inducible nitric-oxide (NO) synthase (iNOS) and RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed and Secreted, also known as chemokine C-C motif ligand-5 or CCL-5) – one of the most important proinflammatory chemokines, involved in the recruiting of multiple immunoinflammatory cells, such as T-lymphocytes, eosinophils, NK-cells, dendritic cells and mastocytes(62).

Furthermore, Ruscitti et al. experimentally proved, in a study published in 2020 regarding the pathophysiological involvement of ferritin in AOSD, that FTH increases the expression of NOD (Nucleotide-oligomerization domain)-like receptors-3 (NLRP-3), but also of mRNA in macrophages, leading to the increased synthesis and secretion of various potent cytokines, most of these being proinflammatory in nature, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and TNF-α; it also increased the expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)(63). Moreover, the same study showed that macrophages treated with FTH stimulated the proliferation of co-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells, but also enhanced the predominant secretion of mature IL-1β, which explains the clinical usefulness of IL-1 therapeutic inhibition (through the use of anakinra) in patients with hyperferritinemic syndromes, particularly with AOSD. Similar mechanisms could also be manifested in severe forms of COVID-19, in which FTH may enhance the macrophage biosynthesis and hyperproduction of IL-6, defined as an important marker for severe COVID-19, which may be therapeutically inhibited through the use of tocilizumab. These relatively recent observations suggest that ferritin may possess important pathogenic roles in the pathophysiology of hyperinflammatory conditions, such as AOSD, MAS and severe COVID-19. Regarding FTL, Ruscitti et al. showed that the L-chains of ferritin have insignificant effects on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines; in fact, according to a study from 2019 published by Zarjou et al., it appears that a compensatory increase in serum FTL, secondary to a decrease in FTH, may have important effects on lowering cytokine levels, associated with lowered mortality rate in sepsis(64). FTL was proven to induce the inhibition of the NF-ҡB intracellular activity, which explains the inhibitory effect of FTL on the expression of proinflammatory mediators in the pathophysiology of sepsis and other hyperinflammatory conditions(64).

It should also be noted that, according to a more recent study from 2022, published by Brands et al., higher serum levels of ferritin correlates with aberrant cytokine responses. Thus, according to the study, patients with serum ferritin levels > 500 ng/mL associated exagerrated cytokine production, such as IL-8, IL-10, IL-27 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), but also expressed increased levels of biomarkers indicative of endothelial dysfunction and activation, reflecting the proinflammatory phenotype of endothelial cells: soluble vascular cell adhession molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), von Willebdrand factor and s-thrombomodulin(65), which could generate a hypercoagulable state.

1.2. The immunosupressive effects of ferritin

Although the proinflammatory activity of FTH has been experimentally proven, several older studies have taken into consideration its immunosupressive roles. As such, FTH appears to induce the suppression of the delayed type of hypersensitivity, a phenomenon involved in the induction of anergy(66), but also in the inhibition of antibody production by B-cells(67), inhibition of phagocytosis mediated by granulocytes and in the regulation of granulocyto-monocytopoiesis(68).

Even though the immunosupressive molecular mechanisms of ferritin currently remain elusive, there are studies which suggest that FTH may operate on particular lymphocyte surface receptors that are yet to be identified(44) or through the down-regulation of CD2, a molecule that operates as a co-factor for lymphocyte stimulation(69). Furthermore, a study published by Gray et al. in 2001 suggested that ferritin may act as an immunosupressive agent through its property to determine the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in lymphocytes(70).

Other studies have suggested that FTH has the ability to interact with the CXC-chemokine receptor-4 (CXCR-4), which inhibits the intracellular activation of MAPK, thus imparing cell proliferation, differentiation and migration during inflammation(71).

Although there are currently multiple studies concerning the complex pathophysiological roles of ferritin and its molecular mechanisms through which it can mediate various inflammatory responses, many of these roles and pathogenic mechanisms are yet to be thoroughly described. However, it seems that ferritin possesses undeniable pathogenic roles within the spectrum of the hyperferritinemic syndromes, which proves that this molecule should be considered more than just a mere iron-storage protein.

CAUSAL ENTITIES OF HYPERFERRITINEMIC SYNDROME

Hyperferritinemia is currently considered a bio-pathological manifestation for a wide range of clinical conditions, some of which are (hyper-)inflammatory or malignant in nature. According to Sandnes et al., in a clinical overview concerning hyperferritinemia, this biological state may be classified based on the iron load status of the organism (

Table 2)

(6).

It should be emphasized that, while hyperferritinemia should not be considered a clinical entity in itself and is biologically defined as the mere increased serum levels of ferritin (most frequently, serum ferritin > 500 ng/dL)(72), which may or may not be associated with (hyper-)inflammatory conditions, hyperferritinemic syndromes define a group of complex pathophysiological and clinical entities, in which hyperferritinemia – the biological hallmark of these conditions – is invariably associated with systemic hyperinflammation and potentially fatal prognosis. It seems that in the context of a hyperferritinemic syndrome, ferritin possesses important pathophysiological roles(72), being frequently associated with systemic hyperproduction of cytokines, as mentioned above.

Dramatic elevations of serum ferritin (often elevated above 1,000 ng/dL)

(73) have been described in several hyperinflammatory conditions, such as autoimmune (for example, cAPS) and autoinflammatory diseases (particularly sJIA and AOSD), severe COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome of COVID-19 (MIS) – which could be considered long-COVID or the post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS)

(74, 75) –, HLH, sepsis and septic shock, as well as cancer, which includes malignant hemopathies, but also solid malignant tumors (

Table 3)

(76).

This present section focuses on several classic hyperferritinemic syndromes: HLH, cAPS, AOSD, septic shock and, more recently, severe COVID-19.

2. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH, hemophagocytic syndrome)

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytic syndrome, is a rare life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome, characterized by uncontrolled hyperactivation of immune cells, aberrant hyperferritinemia and gradual multiorgan damage(77). Although the pathophysiology of HLH is complex and yet to be completely understood, there are studies which have shown that the main pathogenic features of this pathological condition is the uncontrolled hyperactivity of T-cytotoxic lymphocytes and NK-cells, associated with hyperactivation of tissue macrophages (histiocytes) and with systemic hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, a state which was termed ”cytokine storm” or ”cytokine release syndrome” (CRS)(77).

In adults, the general clinical features of HLH include high fever, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathies, bleeding diathesis, sepsis-like syndrome, various degrees of neurological manifestations and gradual progression towards multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)(78). Biologically, patients with HLH generally exhibit high levels of acute phase reactants, such as elevated C reactive protein and hyperferritinemia, altered liver function, high serum levels of triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia), hypofibrinogenemia, bi- or pancytopenia, elevated serum levels of D-dimers and of lactate-dehydrogenase (LDH)(79).

2.1. Etiology

From an etiological perspective, HLH is divided into

primary HLH (pHLH) and

secondary HLH (sHLH). While pHLH is determined by various mutations in genes expressed by cytotoxic T-cells and NK-cells and clinically manifesting mainly during infancy and childhood

(80), sHLH may develop in the course of particular underlying pathological conditions, in which there is a violent immune or inflammatory response, such as infections, autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases and malignancy (hematological malignancies, solid malignant tumors) (

Table 3).

pHLH is determined by genetic mutations in immune cells, familial HLH (FHL) being considered the main subtype of pHLH(77). There are currently five identified types of FHL (FHL-1, -2, -3, -4 and -5), FHL-2 being the most common diagnosed type in Japan, according to one study(81); this subtype has been proved to be caused by a defect of perforin, a cytotoxic molecule secreted by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and/or NK-cell(82). In contrast to FHL-2, FHL-3, -4 and -5 are determined by genetic-induced defects in molecules which are involved in cytotoxic granule trafficking and in the release of perforin towards the target cells, such as Munc13-4, syntaxin-11 and Munc18-2(83, 84, 85). FHL has been associated with autosomal recessive inheritance, although FHL-5 has been proven to be associated with a single allele mutation in Munc18-2(86).

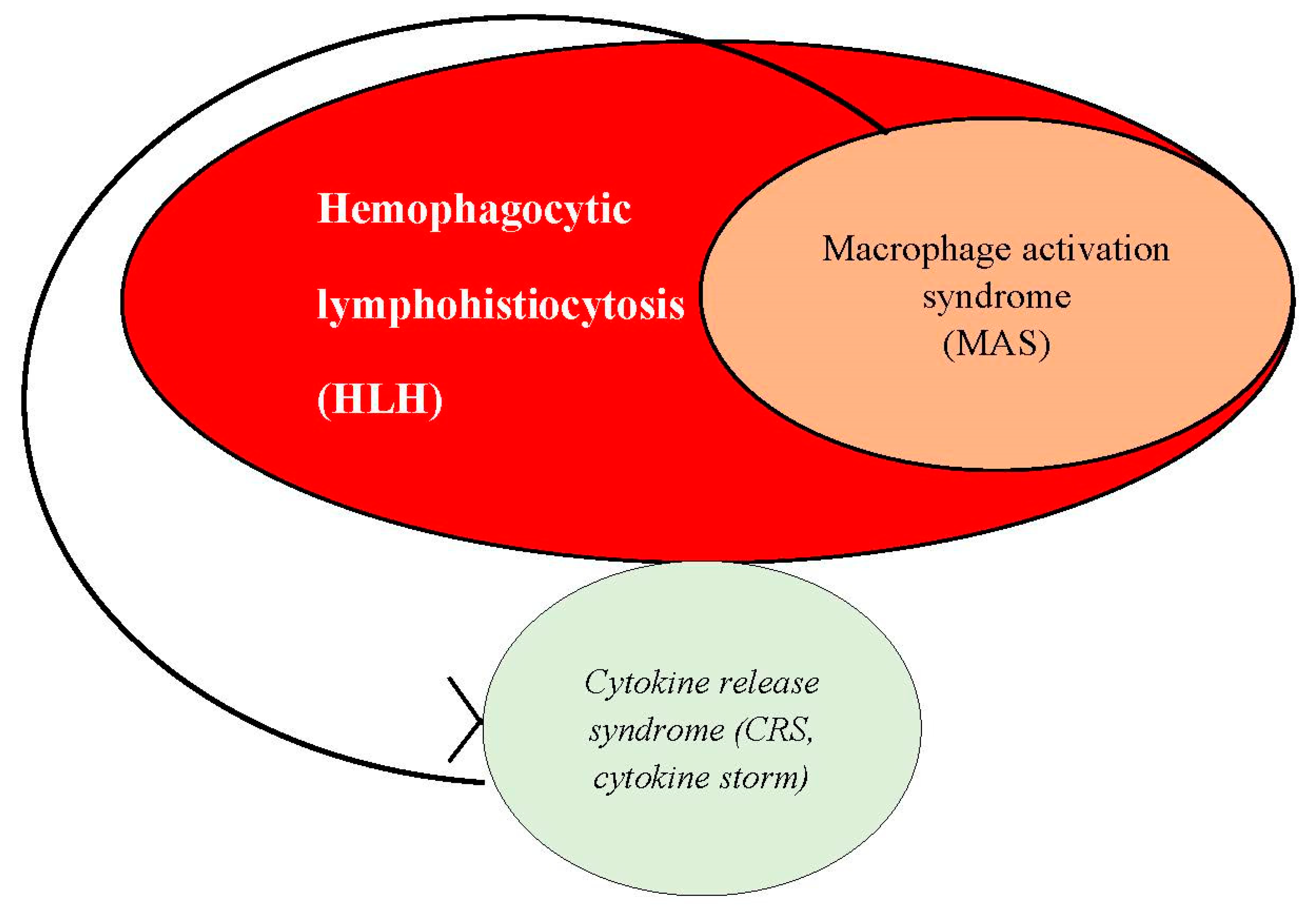

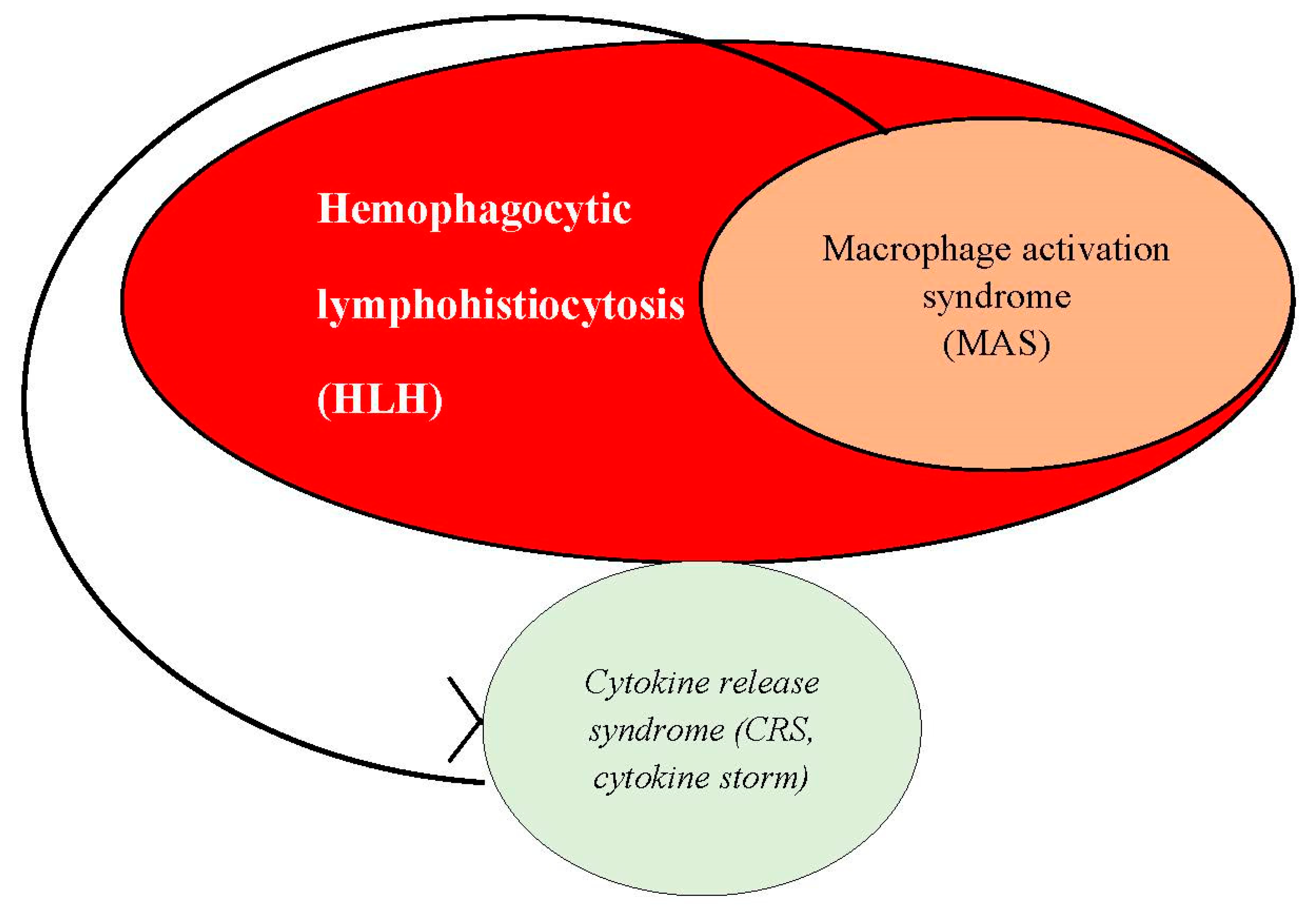

sHLH may be induced by multiple pathological conditions, such as infections, rheumatological diseases (autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders), as well as malignancies (hematological malignancies and solid malignant tumors)(77), being considered one of the most important hyperferritinemic syndromes. The common pathophysiological phenomenon of all of these underlying conditions is represented by the existence of a violent systemic immune or inflammatory response. Epidemiological studies have shown that infectious diseases, most frequently viral infections, account for the most frequently encountered causes of sHLH(87, 88, 89), whereas solid malignant tumors and malignant hemopathies represent 40 to 70% of sHLH in adults, closely followed by systemic autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. In all of these cases, taking into consideration that the main pathophysiological mechanism of sHLH is defined by uncontrolled hyperactivity of macrophages (or histiocytes), associated with systemic hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, sHLH is considered synonymous with the concept of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS or MAS-HLH), especially in the context of an underlying rheumatological (autoimmune or autoinflammatory) disease(90). Thus, MAS should be defined as a subset of HLH (sHLH), in which CRS constitutes the main pathophysiological phenomenon.

Table 3.

Hyperferritinemic syndromes: pressumed etiologies and main clinical features.

Table 3.

Hyperferritinemic syndromes: pressumed etiologies and main clinical features.

| Hyperferritinemic syndrome |

Etiology |

Main clinical features |

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

(sHLH)

|

- 1.

-

Infections:

Viruses Bacteria Parasites Fungi

- 2.

-

Malignancies

Mainly malignant lymphomas

- 3.

Autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases - 4.

-

Other causes (rare):

|

Fever, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathies, sepsis-like syndrome, variable degrees of neurological manifestations, potential progress towards multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) |

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome

(cAPS)

|

Potential infection(-s) operating as triggers in the context of existent antiphospholipid antibodies |

Microvascular thrombosis, manifesting as renal failure;

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), encefalopahty, stroke, seizures, coma, myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular defects, livedo reticularis, digital ischemia and skin necrosis, infarction of spleen, adrenal glands, pancreas, retina and bone marrow. |

Adult-onset Still’s disease

(AOSD)

|

Yet to be described, but supposedly:

-viral infections;

-bacterial infections;

-solid cancers;

-hematological malignancies. |

Reccurent fever, rash, myalgias, arthralgias, splenomegaly/hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathies, sore throat, pleural effusion, pericarditis, abdominal pain, aseptic meningitis, aseptic encephalitis, diseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), intravascular hemolysis. |

| Septic shock |

Infections:

-virus;

-bacteria;

-parasites;

-fungi |

High fever, arterial hypotension, DIC, variable degrees of neurological manifestations, progression towards MODS |

Severe coronavirus disease-2019

(COVID-19)

|

Infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) |

ARDS, microvascular thrombosis, DIC, viral sepsis, potential progression towards MODS |

Furthermore, it should be noted that the pathophysiology of sHLH or MAS overlaps with the pathophysiological mechanisms of the underlying or causal pathological conditions.

The most well known rheumatological disease that may determine the development of MAS-HLH are systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rhematoid arthritis (RA), Sjӧgren’s syndrome, cAPS, but also sJIA and AOSD(91).

Eventhough autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders possess important roles in potentially generating sHLH, studies show that various viral infections are considered the main causes of sHLH, most frequently Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), but also cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes-simplex virus (HSV)(92). One case report also showed that HIV infection may also generate HLH(93). Recent studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2, the causal agent of COVID-19, as well as PCS may also determine sHLH(94).

2.2. Pathophysiology

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that define the pathophysiology of HLH are yet to be completely understood, although there are several studies which focused on the general underlying phenomena.

Individuals with active HLH exhibit dramatic elevation of various serum proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-16, IL-18 and M-CSF, some of which are involved in the development of the clinical manifestations and biological modifications described in HLH, such as altered general state, high fever, vascular leak syndrome, (pan-)cytopenia, elevated serum levels of C reactive protein (CRP) and hyperferritinemia(95, 96, 97). Some of the aforementioned proinflammatory cytokines are also strongly involved in the development of endothelial dysfunction, a pathophysiological state in which endothelial cells molecularly modifies their phenotype towards a procoagulant and proinflammatory functional state, which further agravates the systemic pathological status of the organism. As such, coagulopathies are considered one of the main pathological features in HLH. Given the hyperinflammatory state associated with the dramatic elevation of serum proinflammatory cytokines (hypercytokinemia), this pathobiological phenomenon was termed “cytokine storm” or “cytokine release syndrome” (CRS), considered to be a violent systemic immuno-inflammatory response, which has been proven to be generated by uncontrolled activity of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and NK-cells, which, in turn, overstimulate the activity of reticuloendothelial macrophages(77). Subsequently, these histiocytes, once continuously hyperactivated, are involved in the development of hypercytokinemia, as well as of hemophagocytosis, which may be described on biopsies from the bone marrow, spleen, lymphnodes and/or liver in patients with HLH(72). Regarding hemophagocytosis, this pathophysiological phenomenon defines the engulfment or hyperreactive phagocytosis of erythrocytes, lymphocytes or other hematopoietic cellular precursors by (hyper-)activated reticuloendothelial macrophages or histiocytes, which may be described within the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or even liver(98), which may lead to different forms of cytopenia (anemia, leukopenia/lymphopenia and/or thrombocytopenia; if all hematopoietic cell lines are affected, the resultant phenomenon is defined as pancytopenia). As it is known, phagocytosis represents an immune process which involves attachment and binding of Fc antibody fragments and C3b complement fractions to particular receptors described on leukocyte membranes, engulfment and subsequent intracellular fusion of lysosomes with phagocytic vacuoles, followed by cellular biochemical digestion or non-self molecular elements(98). Hemophagocytosis should be considered an overactivated form of phagocytosis, in which the increased activity of histiocytes may be described in infections, various inflammatory diseases (such as autoimmune and autoinflammatory) and even in malignancies(99).

Although the precise pathophysiological pathways through which HLH develop and evolve are not well described and understood, recent studies hold the belief that NK-cells and cytotoxic T-lymphocytes become unable to lyse infected or otherwise activated antigen-presenting cells (APCs); prolonged interactions between activated lymphocytes and tissue macrophages gradually lead to the amplification of a violent systemic cytokine cascade (cytokine storm syndrome), this loss-of-function of NK-cell and cytotoxic T-lymphocytes being further worsened under the influence of the already developed hypercytokinemic state(62, 80).

Currently, it is believed that defects in NK-cell and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte granule-mediated cytotoxicity results in ineffective clearance of infectious agents and/or defective suppression of antigen presentation, which generates persistent antigen exposure and, thus, prolonged activation of T-lymphocytes and interaction with tissue macrophages(100). Although the exact pathophysiological mechanisms of sHLH is not completely understood, one study showed that HLH-MAS could develop under the influence of persistent activation of Toll-like receptor-9 (TLR-9), as it was shown in a murine model(101).

Hence, in HLH there is a prolonged and exaggerated T-lymphocyte and tissue macrophage interaction and activation, which determines an overwhelming systemic secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, defined as cytokine storm or cytokine release syndrome, characterized by dramatic serum elevations of such immune mediators, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-8, IL-12, IL-18 and M-CSF(101). There is also an uncontrolled proliferation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, a dramatic production of IFN-γ and hyperproliferation of histiocytes, with subsequent invasion of reticuloendothelial organs, such as liver, spleen, bone marrow and lymphnodes, a phenomenon which explains one of the most important clinical features in HLH: organomegaly, especially hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathies(102). By invading the bone marrow, hyperreactive histiocytes engulf hematopoietic cellular precursors, which generates hemophagocytosis and subsequent (pan-)cytopenia. These pathophysiological phenomena thus explain the name of this pathological condition.

While IFN-γ has been proved to induce macrophage hyperactivation and stimulate hemophagocytosis, TNF-α is thought to be a fundamental element in the development of hypofibrinogenemia and hypertriglyceridemia(102). Furthermore, there have been advances in the understanding of the immunosuppressive state in HLH; studies suggest that certain down-regulation of genes which are involved in the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity, with the participation of TLR expression in B- and T-lymphocytes, may be a causal factor of this particular pathological state. As such, individuals diagnosed with HLH may express a susceptibility to various infections, caused by the aforementioned immunodeficient state(104), which could result in the development of sepsis, septic shock and MODS.

2.3. Clinical features and diagnosis

The clinical manifestations of HLH are directly correlated with the systemic effects of the various proinflammatory cytokines which are strongly involved in the pathophysiology of this condition, but also with hyperactivation of tissue macrophages.

Patients with HLH express systemic and non-specific clinical manifestations, such as altered general state, with high grade fever associated with shivers, progressive cytopenias (anemia, leukopenia/lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia), liver dysfunction, generally expressed clinically through the presence of jaundice, coagulopathy, which may induce tissue ischemia and necrosis, but also variable neurological manifestations(105), such as seizures, altered mental state, brain stem symptoms and ataxia(106, 107, 108). According to studies, these neurological manifestations may be seen in 30 to 50% of patients with HLH. Furthermore, hepatosplenomegaly may be observed in patients with HLH, although this clinical finding is not specific and may not be present in all cases.

The diagnosis of HLH is frequently challenging, especially regarding the differential diagnosis of this hyperinflammatory condition, which should be performed with severe infections and rheumatological diseases. Noteworthy is that certain modified biological parameters should be taken into consideration, such as elevated serum levels of ferritin; a level >500 µg ferritin/L is considered to be supportive in the diagnosis of HLH(109), although this value is non-specific and may be present even in various febrile diseases. However, dramatic increased levels of serum ferritin, >10,000 µg/L, is considered to be specific and diagnostic of HLH, with 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity(110). Other markers serve as useful elements in the diagnosis of HLH as well, such as serum elevation of certain proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-10 and, especially, IL-6) and increased serum levels of soluble CD163 (sCD163), which represents an immunological marker of monocyte/macrophage activation(111, 112).

Table 4 shows the diagnostic criteria for HLH (HLH-2004 criteria).

Table 4.

HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria (adapted from (72)).

Table 4.

HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria (adapted from (72)).

| Diagnostic criteria for HLH – 5 out of 8 criteria required in the diagnosis |

|---|

| Cytopenia: affecting 2 or 3 lineages in peripheral blood: anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia:

|

| Fever: TO C ≥38,5O C |

Hypertriglyceridemia; fasting serum triglycerides ≥265 mg/dL

Hypofibrinogenemia; serum fibrinogen ≤150 mg/dL |

| Hyperferritinemia; serum ferritin ≥500 ng/mL |

| Splenomegaly or hepatosplenomegaly |

| Soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL2R, CD25) >2,400 U/mL |

| Evidence of hemophagocytosis on bone marrow, spleen, lymphnodes and/or liver biopsies |

It appears that the diagnosis of MAS-HLH associated with rheumatological diseases is more challenging, taking into consideration that there is a high rate of overlap between these immunopathological conditions and MAS(113). Furthermore, serum ferritin levels used in the diagnosis of HLH proved to be fundamental; serum ferritin levels >3000 ng/mL should raise high suspicion of MAS-HLH(73, 114).

1. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (cAPS)

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (cAPS) constitutes a severe and rare form of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), characterized by disseminated thrombotic vascular phenomena at the level of multiple tissues, gradually leading to MODS(115), and affecting <1% patients diagnosed with APS. Epidemiological data have shown that cAPS mainly affects women, in 72% of all cases, with a mean age of 39 years old(116).

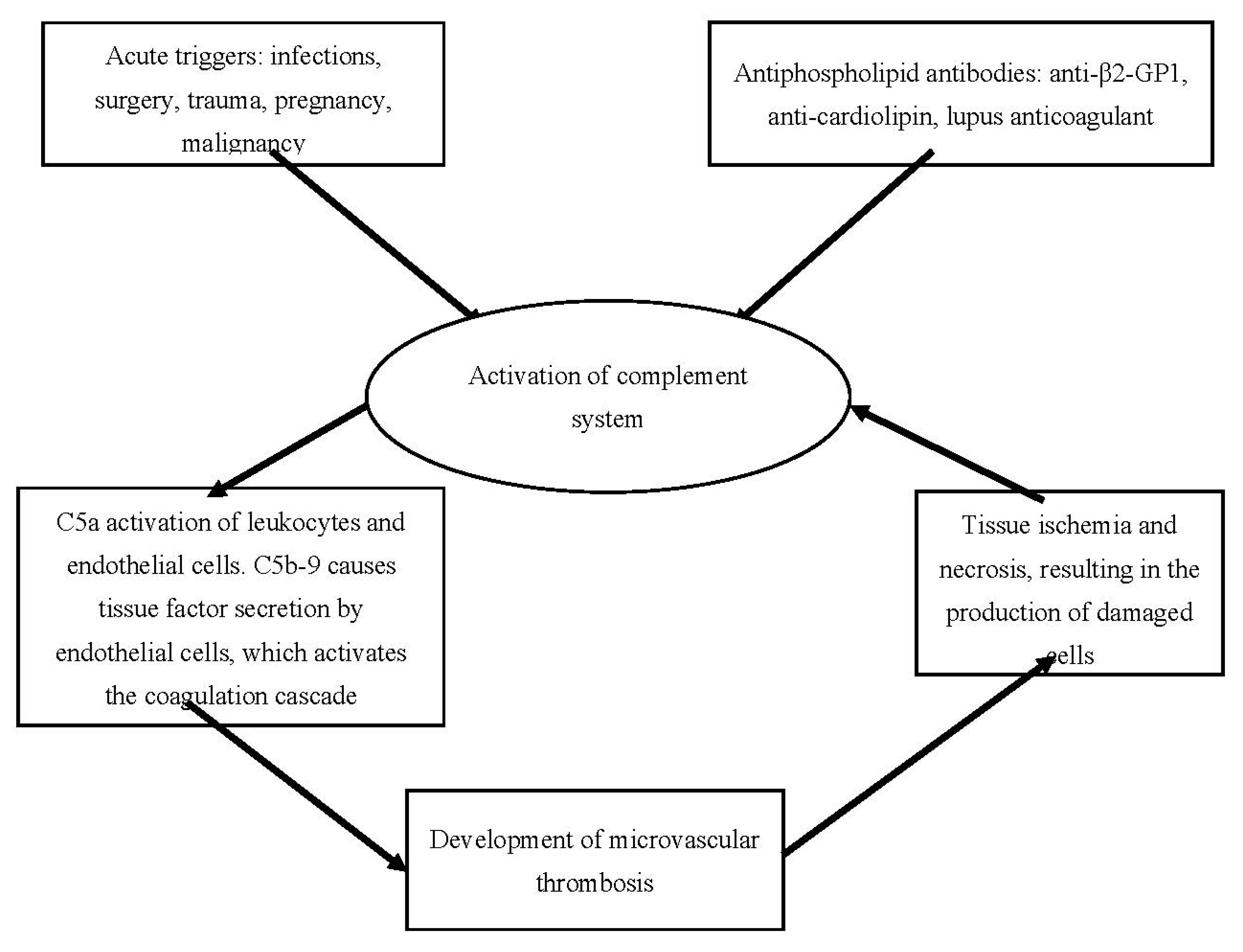

The etiology and general pathophysiological mechanisms of cAPS are represented in Fig. 2. below.

From a clinical perspective, patients with cAPS express almost simultaneous multiple organ involvement, most frequently within a week, having positive antiphospholipid antibodies, although the clinical features strongly depend on the type of affected organ and organ systems(116). According to multiple clinical observations, these include acute renal failure and renovascular hypertension, ischemic ulcers, livedo reticularis and/or gangrene, ischemic cerebrovascular events or stroke, ischemic hepatitis, pulmonary embolism or acute respiratory distress syndrome; myocardial infarction, determined by acute coronary thrombosis, may also be present. Furthermore, multiple modified biological parameters may be observed, such as thrombocytopenia, increased serum levels of D-dimers, hyperferritinemia, hemolytic anemia and increased serum creatinine levels – which is indicative of renal failure, in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Thrombotic microangiopathy, which is the main pathological finding in APS (and cAPS), is frequently observed on biopsies.

Table 5 describes the general diagnostic criteria for cAPS, which requires the differential diagnosis and exclusion of other causal entities involved in multiple microthromboses

(117). The pathological conditions considered in the differential diagnosis are disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), sepsis, various forms of systemic vasculitis and HELLP syndrome (

Hemolysis –

Elevated

Liver enzymes –

Low

Platelet count) in pregnant women

(117).

Table 5.

Diagnostic criteria for cAPS (adapted from (72)).

Table 5.

Diagnostic criteria for cAPS (adapted from (72)).

| Diagnostic criteria for cAPS – all 4 criteria required for the diagnosis |

|---|

| Multiple organ involvement (more than 3 organs, tissues, systems) |

| Synchronous clinical manifestations or clinical onset within a week |

| Pathological evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy |

| Positive antiphospholipid antibodies |

Regarding hyperferritinemia, this biological feature was observed in 71% of patients diagnosed with cAPS; approximately one third of all patients with cAPS exhibit dramatic increase in serum ferritin levels (>1000 ng/mL)(118). It should also be noted that several proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α are involved in the pathophysiological mechanism which leads to non-thrombotic phenomena, such as ARDS, most probably due to the functional and structural alteration of the alveolo-capillary membrane.

Figure 2.

Etiology and general pathophysiological mechanisms in cAPS (adapted from (119)).

Figure 2.

Etiology and general pathophysiological mechanisms in cAPS (adapted from (119)).

3. Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD)

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) constitutes a rare multisystemic autoinflammatory disorder, clinically characterized by high recurrent fever, evanescent skin rash, lymphadenopathies, polyarthralgia, occasional hepatosplenomegaly, sore throat and biologically by the existence of high-grade inflammation, with leukocytosis with neutrophilia and hyperferritinemia(120, 121). AOSD may potentially progress towards the development of MODS.

3.1. Etiology

The exact causes of AOSD are unknown, although studies have shown that there are two main categories of risk factors involved in the development of this pathological condition: genetic factors infectious agents.

Genetic factors. Numerous studies have described a strong association between AOSD and HLA alleles, such as HLA-Bw35, HLA-B17, HLA-B18, HLA-B35 and HLA-DR2, expressed in various ethnic groups(122, 123, 124, 125). Interestingly, polymorphisms in genes involved in the biosynthesis of IL-18, serum amyloid A1 and macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF) have also been described, these polymorphisms generating the high susceptibility of individuals with AOSD(126, 127, 128, 129).

Infectious agents. Clinical observations and multiple studies over the years have proved that various infections, especially viral infections, are potential risk factors and triggers in the development of AOSD, most probably due to the existence of similar clinical manifestations, such as high fever, sore throat and rash before the onset or relapse of disease(130, 131). Some of the viral entities which have been associated with the development of AOSD are rubella virus, measles morbillivirus, mumps virus, EBV, CMV, parvovirus B19, adenovirus, echovirus, human herpes virus-6, Influenza virus and coxsackievirus. It should be noted, however, that some other infectious agents have been described as potential triggers, such as Yersinia enterocolytica, Campylobacter jejuni, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Borrelia burgdorferi(132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137). Noteworthy is the fact that it appears that CMV infection is strongly associated with the initiation and amplification of the inflammatory response in AOSD(138).

3.2. Pathophysiology: AOSD-associated MAS, cytokine storm and the pathogenic role of ferritin

AOSD is currently considered a classic hyperferritinemic syndrome, characterized by the existence of cytokine storm, this pathophysiological phenomenon being involved in the activation and amplification of systemic inflammation(121, 130, 139). The major pathogenic role in AOSD is possessed by reticuloendothelial macrophages and neutrophils, along with NK-cells and T-lymphocytes, all of these immune cellular elements being involved in the hyperactivated inflammatory response(130).

The pathophysiology of AOSD is closely related to HLH (and MAS). In fact, AOSD appears to overlap with both (s)HLH and MAS, as all three pathological conditions share the same pathophysiological evolution or AOSD may complicate with MAS-HLH.

Individuals with AOSD generally express hyperactivation of tissue macrophages (hyperactivation of the reticulohistiocytic system or MAS), a pathogenic phenomenon biologically reflected in the elevated levels of various biomarkers, including MIF and IFN-γ(140, 141). It has been suggested that the continuous hyperactivation of histiocytes is a direct result of their persistent molecular interaction with either pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)(142, 143). The pathogenic role of several DAMPs have been well described in the pathophysiology of AOSD; these include high mobility group box-1, advanced glycation-end (AGE) products, S100 proteins, soluble CD163, MIF, as well as neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)(143), all of these elements being involved in the hyperactivation of macrophages through their molecular and functional interaction with TLR, leading to the activation of several intracellular signalling systems, including NLRP3 inflammasomes; NLRP3 inflammasomes, once activated, is involved in the upregulation of caspase-1, leading to the proteolytic cleavage of two fundamental cytokines: IL-1β and IL-18, which results in the production of their mature functional forms(142, 144, 145). The extracellular secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 further determines the immune cells to secrete large amounts of serum proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, TNF-α, but also IL-1β and IL-18 themselves(142, 144, 146). This uncontrolled systemic hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines has been proved to be deleterious to multiple tissues (for example, endothelial dysfunction and endothelial phenotype modification towards a proinflammatory and procoagulant functional state, generating a vicious circle) and organs, constituting a systemic hyperinflammatory state, which has been defined as cytokine storm or cytokine release syndrome, which is the definitive feature of MAS.

Regarding ferritin, this particular molecule is produced, as it was mentioned, by multiple cellular types, including macrophages, hepatocytes and liver histiocytes (Kupffer cells)(147), and may operate as a proinflammatory cytokine(62). From a pathogenic perspective, ferritin may activate an iron-independent intracellular molecular cascade, which determines the activation of a complex system, known as phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase – nuclear factor kappa-B (PI3K-NF-ҡB); once activated intracellularly, this system amplifies the expression of various proinflammatory molecular mediators, such as IL-1β, iNOS, RANTES, inhibitor of NF-ҡB and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 in hepatic stellate cells (Ito cells)(62). It should also be noted that ferritin itself is molecularly regulated by various cytokines, including IL-1β(60, 148). Although more studies should be performed, it is currently believed that ferritin possesses essential roles in the initiation and amplification of systemic inflammation in AOSD, operating even as an oxygen radical donor(149).

Other pathophysiological mechanisms in AOSD have been described as well, such as: neutrophil activation associated with increased NETs formation, NK-cells deficiency and T-lymphocytes imbalance(150)

3.3. Clinical features and diagnosis

Patients with AOSD generally express several frequently encountered clinical manifestations, such as high recurrent fever, arthritis and/or polyarthralgia (this may induce frequent confusions with rheumatoid arthritis, which explains the necessity of a thorough differential diagnosis), evanescent skin rash, but also sore throat, odynophagia, myalgia, myositis, lymphadenopathies and hepatosplenomegaly, while some patients may also exhibit other associated yet more severe manifestations: pericarditis, myocarditis, pleuritis and/or hepatitis(150). Occasionally, individuals with AOSD may express life-threatening systemic complications, such as pulmonary hypertension, fulminant hepatitis, heart failure, ARDS, DIC and thrombotic microangiopathy(121, 139, 151).

Among laboratory findings, CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are almost always constantly elevated(72). Very high serum levels of ferritin are closely related to the disease activity and are associated with recurrent flares, clinical and biological manifestation of MAS, as well as with poor prognosis(`152, 153, 154). It appears that dramatic elevations of serum ferritin higher than five times the upper limit of normal values, if combined with a decrease in the proportion in the glycosylated fraction of ferritin (<20%), increase the specificity of AOSD to 93%(121, 155, 156). Furthermore, significant leukocytosis, with >15,000 leukocytes/mm3, may be described, being associated with neutrophilic predominance(72). However, in contrast to autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and SLE, AOSD generally exhibits negative rheumatoid factor and negative anti-nuclear antibodies.

The most frequently used diagnostic criteria for AOSD are the

Yamaguchi criteria (

Table 6).

For the diagnosis of AOSD, it is necessary that at least five of the criteria should be met, with at least two of them coming from major criteria.

Serum proinflammatory cytokines levels, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α and IFN-γ are dramatically increased in AOSD and are generally associated with the activity of the disease(139, 157, 158). Clinical and biological observations have shown that, among these proinflammatory cytokines, IL-18 is considered to be an essential biomarker in the diagnosis of AOSD(159, 160). Studies have shown that increased levels of serum IL-18 are associated with hepatitis, steroid dependence and inflammatory pattern(161, 162), while increased serum levels of IL-1β have been associated with systemic pattern and increased serum levels of IL-6 are associated with the existence of arthritis(158, 163).

4. Septic shock

Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening multiple organ dysfunction induced by the host’s violent systemic immune response to various disseminated infections, according to the International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock(164). It is well-known that the immune reaction to different infectious causes the systemic hyperproduction of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, generating variable degrees of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS). Septic shock is currently considered, along with HLH and AOSD, a hyperferritinemic syndrome, although further investigations are required regarding the pathophysiological mechanisms in which increased serum levels of ferritin generates the hyperinflammatory state in septic patients.

Regarding sepsis-associated hyperferritinemia, sepsis and septic shock associated with dramatically increased serum levels of ferritin are related predominantly to infections with DNA viruses, parasites, intracellular bacteria, fungi, as well as to individuals undergoing blood transfusions and/or diagnosed with hemolysis(72). During the course of the infectious process, activated macrophages hyperproduce serum ferritin after being stimulated by IL-1β and TNF-α, NF-ҡB being the main intracellular signalling system involved(165). Intuitively, further immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation is expected, as serum ferritin levels above 4420 ng/ml generates the systemic increase of IL-6, IL-18, IFN-γ and sCD163, indicative of an exaggerated proinflammatory response(166), which most probably generates a vicious proinflammatory cycle, aggravating

Noteworthy is the fact that serum ferritin levels in septic pediatric patients, who are in need of mechanical intubation for more than 48 hours, were directly associated with the severity of the underlying disease(167).

5. Severe COVID-19

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a pathological condition first recognized during December 2019 and further investigated during 2020, has generated one of the most important epidemiological phenomena in the last century, its importance being determined by the disease’s high morbidity and mortality rate worldwide. There are currently multiple studies and clinical observations that have proven the pathophysiological relationship between the infection induced by SARS-CoV-2 and multiple organ dysfunction, which further proves that COVID-19 is not merely a pulmonary infectious disease, but rather a systemic infectious-inflammatory pathological entity, associated, in severe cases, with systemic hyperinflammatory immune response, including the development of hyperferritinemia. Currently, severe COVID-19 has been introduced into the category of hyperferritinemic syndromes, taking into consideration the various pathophysiological phenomena this disease shares with other pathological conditions which may be associated with MAS.

As studies over the past three years have suggested, the hallmark of severe COVID-19 is represented by a hyperinflammatory immune response characterized by dramatic serum elevations of IL-1β, IL-1RA and TNF-α, although higher serum levels of IL-2, IL-10 and TNF-α have been reported in critically-ill patients, treated in intensive care units (ICU). It is well known that critically ill patients exhibit neutrophilia, lymphopenia and very increased levels of IL-6(168), which suggests the existence of a CRS or MAS, similarly to sHLH or AOSD. Two main mechanisms have been described; the first pathogenic mechanism involves a delayed IFN response, mediated by multiple structural and non-structural proteins associated with SARS-CoV-2, this phenomenon further orchestrating immune reactions and interfering with T-lymphocytes, generating T-cell apoptosis. The second pathogenic mechanism is defined by heavy accumulation of monocyte-macrophages, but also neutrophils in the pulmonary parenchyma, following coronoviral infection, these immune cellular elements being important sources of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines(169).

Interestingly, one of the underrecognized biological features of severe COVID-19 is hyperferritinemia. Mehta et al. proposed that COVID-19 may be an important member of the hyperferritinemic syndromes, as CRS characterizes the severe forms of the disease, in similar manner to sHLH or AOSD(170). It seems that very increased serum levels of ferritin is an essential biological tool in the diagnosis of COVID-19 severity, but also suggesting worse prognosis, in which case hyperferritinemia is virally driven(171). Ferritin is most probably operating as a proinflammatory cytokine – whose secretion is induced by various proinflammatory cytokines – in severe COVID-19, in a similar or identical manner to AOSD, leading to a “MAS-like syndrome” in severe COVID-19.

There have been multiple studies which correlated the hyperferritinemic state with severe COVID-19. Several studies focused on autopsy findings on COVID-19 patients; macroscopic features in autopsies included pleurisy, pericarditis, lung consolidation and pulmonary edema(172), whilst microscopic findings described diffuse alveolar damage associated with heavy inflammatory infiltrates constituted mainly by monocyte-macrophages, with minimal lymphocyte infiltration, but with the presence of multinucleated giant cells(173, 174). It should be noted that similar pathological findings – pleurisy and pericarditis, have also been described in patients with AOSD and MAS(175, 176).

Currently, there are studies which describe common pathophysiological phenomena between severe COVID-19 and AOSD, as COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory state reminds of the hyperinflammatory state associated with AOSD(130). Therefore, due to the pathological similarities with this aforementioned autoinflammatory disease, a genetic predisposition to the development of hyperinflammatory states and hyperferritinemia in severe COVID-19 should not be omitted. Furthermore, according to a study by Fung S. Y. et al. regarding IL-1β, SARS-CoV-2 proved to have the pathogenic property to upregulate the intracellular activity of the inflammasome, which generates the hyperproduction of IL-1β, which is a pathophysiological feature also described in AOSD(177).

During the course of severe COVID-19, active ferritin extracellular secretion may occur, although the exact cellular source of serum ferritin in COVID-19 is not well described. Macrophages, as it was shown, are involved in the hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and might also be involved in the hyperproduction of serum ferritin(3). As it was described in the present review, ferritin biosynthesis may be induced by proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6(3). This aspect is noteworthy, as serum levels of IL-6 may be dramatically increased in severe COVID-19, this proinflammatory cytokine being used as an useful parameter associated with COVID-19 severity(178). As such, complex pathophysiological molecular mechanisms and associations might exist between serum ferritin and proinflammatory cytokines in the context of severe COVID-19. Further investigations should be performed regarding the pathophysiological nature of ferritin in COVID-19.

If ferritin operates as a pathogenic proinflammatory mediator in COVID-19, it seems that certain therapeutic strategies should be performed, such as plasma exchange, which could prove beneficial in severe infection with SARS-CoV-2, as this would decrease the serum levels of both ferritin and proinflammatory cytokines(179).

CONCLUSION

Although the spectrum of hyperferritinemic syndromes is currently composed of a relatively small number of rare disorders or diseases, it should be noted that hyperferritinemia, especially in the context of serum ferritin levels > 1000 ng/mL, should raise interest into the clinical and biological investigation of a hyperferritinemic syndrome. The clinician, especially the internist, rheumatologist, infectious disease physician and intensive-care physician, should be aware of the pathophysiological role of ferritin in various inflammatory diseases and clinically and biologically recognize a hyperferritinemic syndrome and its possible causes, through a thorough physical examination of the patient and paraclinical analysis of various biological parameters, such as complete blood count, ESR, CRP and ferritin. Eventhough the pathophysiological roles of ferritin in the context of various rheumatological and/or infectious diseases is yet to be completely clarified, clinical medicine should raise its interest into the diagnostic usefulness of this particular biological parameter, as it has been suggested by multiple studies that it possesses important pathogenic proinflammatory and/or immunosuppressive roles in various inflammatory diseases or syndromes, especially in severe or critically-ill patients.

Abbreviations

| AGE |

advanced glycation-end products |

| ALD |

alcoholic liver disease |

| AOSD |

adult-onset Still’s disease |

| ARDS |

acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| APS |

antiphospholipid syndrome |

| cAPS |

catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome |

| CARS |

compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome |

| CMV |

cytomegalovirus |

| COVID-19 |

coronavirus disease-2019 |

| CRP |

C reactive protein |

| CRS |

cytokine release syndrome |

| DAMPs |

damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DIC |

disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| EBV |

Epstein-Barr virus |

| ER |

endoplasmic reticulum |

| ESR |

erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| FTH |

heavy-chain ferritin, H-subunits of ferritin |

| FTL |

light-chain ferritin, L-subunits of ferritin |

| HELLP |

acronym for a pathophysiological triad: hemolysis - elevated liver enzymes - low platelet count (HELLP syndrome) |

| HFE |

hemochromatosis gene, human homeostatic iron regulator protein, High FE2+ |

| HIT |

heparin-induced thrombocytopenia |

| HUS |

hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| HLA |

human leukocyte antigen |

| HLH |

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis |

| ICU |

intensive care unit |

| IL |

interleukin |

| iNOS |

inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| MAPK |

mitogen-activated protein-kinase |

| M-CSF |

macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| MAS |

macrophage activation syndrome |

| MIF |

macrophage inhibitory factor |

| NAFLD |

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NETs |

neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NLRP |

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, Leucine-rich Repeat and Pyrin domain-containing |

| PAMPs |

pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PCS |

post-COVID syndrome |

| RANTES |

Regulated on Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed and Secreted |

| SIRS |

systemic inflammatory response syndrome |

| sJIA |

systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| SLE |

systemic lupus erythematosus |

| TIM |

T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin domain |

| TLR |

Toll-Like Receptor |

| TNF |

tumor necrosis factor |

| TTP |

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| VCAM |

vascular cell adhesion molecule |

References

- Cricthon, R.R.; Chaloteaux-Wauters, M. Iron transport and storage. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987, 164, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knovich, M.A.; Storey, J.A.; Coffman, L.G.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 2009, 23, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosário et al. The Hyperferritinemic Syndrome: macrophage activation syndrome, Still’s disease, septic shock and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Medicine 2013, 11, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.M.; Arosio, P. The ferritins: molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 1996, 1275, 161–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood 2002, 99, 3505–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandnes, M.; Ulvik, R.J.; Vorland, M.; Reikvam, H. Hyperferritinemia—A Clinical Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.J.; Frazer, D.M. Current understanding of iron homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106 (Suppl. 6), 1559S–1566S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Bencze, K.Z.; Stemmler, T.L.; Philpott, C.C. A Cytosolic Iron Chaperone That Delivers Iron to Ferritin. Science 2008, 320, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, K.H.; Hagedoorn, P.-L.; Hagen, W.R. Unity in the Biochemistry of the Iron-Storage Proteins Ferritin and Bacterioferritin. Chem. Rev. 2014, 115, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Domenico, I.; Vaughn, M.B.; Paradkar, P.N.; Lo, E.; Ward, D.M.; Kaplan, J. RETRACTED: Decoupling Ferritin Synthesis from Free Cytosolic Iron Results in Ferritin Secretion. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambod M, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Combined high serum ferritin and low iron saturation in hemodialysis patients: the role of inflammation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=167&contentid=ferritin_blood.

- ten Kate J, Drenth JP, Kahn MF, van Deursen C. Iron saturation of serum ferritin in patients with adult onset Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 2213–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Worwood, M. Serum ferritin. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1979, 10, 171–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, D.A.; Cook, J.D.; Finch, C.A. A Clinical Evaluation of Serum Ferritin as an Index of Iron Stores. New Engl. J. Med. 1974, 290, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.A.; Gutierrez, L.; Weiss, A.; Leichtmann-Bardoogo, Y.; Zhang, D.-L.; Crooks, D.R.; Sougrat, R.; Morgenstern, A.; Galy, B.; Hentze, M.W.; et al. Serum ferritin is derived primarily from macrophages through a nonclassical secretory pathway. Blood 2010, 116, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, D.R.; A Bacon, P.; Eastham, E.J.; Brigham, K. Synovial fluid ferritin in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1980, 281, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindic, C.J.; Collet-Cassart, D.; Cambiaso, C.L.; Masson, P.L.; Laterre, E.C. The clinical relevance of ferritin concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1981, 44, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, W.; Rabouille, C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, R.M.; Hegde, R.S. Toward a structural understanding of co-translational protein translocation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016, 41, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worwood, M. The diagnostic value of serum ferritin determinations for assessing iron status. . 1987, 20, 229–35. [Google Scholar]

- Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Iron and ferritin in inflammation and cancer. . 1994, 10, 119–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Jia, J.; Kumar, S.; Choi, S.W.; Gu, Y.; Mudd, M.; Dupont, N.; Jiang, S.; Peters, R.; Farzam, F.; et al. Dedicated SNARE s and specialized TRIM cargo receptors mediate secretory autophagy. EMBO J. 2016, 36, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. N., Eubanks, S. K., Schaffer, K. J., Zhou, C. Y., Linder, M. C. Secretion of ferritin by rat hepatoma and its regulation by inflammatory cytokines and iron. Blood 1997, 90, 4979–4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recalcati, S.; Invernizzi, P.; Arosio, P.; Cairo, G. New functions for an iron storage protein: The role of ferritin in immunity and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2008, 30, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W., Knovich, M. A., Coffman, L. G., Torti, F. M., Torti, S. V. Serum ferritin: past, present and future. Biochem Biophys Acta 2010, 1800, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Hevi, S.; Chuck, S.L. Regulated secretion of glycosylated human ferritin from hepatocytes. Blood 2004, 103, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fautrel, B.; Le Moël, G.; Saint-Marcoux, B.; Taupin, P.; Vignes, S.; Rozenberg, S.; Koeger, A.C.; Meyer, O.; Guillevin, L.; Piette, J.C.; et al. Diagnostic value of ferritin and glycosylated ferritin in adult onset Still's disease. .J Rheumatol 2001, 28, 322–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fautrel, B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008, 22, 773. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth, C.; Le Moel, G.; Lasne, Y.; Revenant, M.C.; Agneray, J.; Kahn, M.F.; Bourgeois, P. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol 1994, 21, 890–5. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, S.; Ota, T.; Eto, S. Biochemical analysis of ferritin subunits in sera from adult Still's disease patients. Rheumatol. Int. 1995, 15, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollner, R. C., Kern, P., Steininger, H. et al. Hyperferritinemia in Still syndrome in the adult and reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Med. Klin. 1997, 92, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambotte, O.; Cacoub, P.; Costedoat, N.; Le Moel, G.; Amoura, Z.; Piette, J.-C. High ferritin and low glycosylated ferritin may also be a marker of excessive macrophage activation. J. Rheumatol 2003, 30, 1027–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.-N.; Feng, C.-C.; Tian, L.-P.; Chen, X. [The early diagnosis and clinical analysis of 57 cases of acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2009, 48, 312–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ben m’rad, M., Leclerc-Mercier, S., Blanche, P. et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: clinical and biological disease patterns in 24 patients. Medicine 2009, 88, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambotte, O.; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Amoura, Z.; Piette, J.-C.; Cacoub, P. drug-induced hemophagocytosis. Am. J. Med. 2002, 112, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worwood, M.; Cragg, S.J.; Wagstaff, M.; Jacobs, A. Binding of Human Serum Ferritin to Concanavalin A. Clin. Sci. 1979, 56, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muylle, L.; Blockx, P.; Becquart, D. Binding of serum ferritin to concanavalin A in patients with malignancy. . 1986, 40, 225–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takakuwa, Y.; Miyazawa, K.; Yoshikawa, O.; Toyama, K. [The clinical significance of glycosylated ferritin in iron overloads and hematopoietic malignancies]. . 1994, 35, 744–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ferring-Appel, D.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. Cell-autonomous and systemic context-dependent functions of iron regulatory protein 2 in mammalian iron metabolism. Blood 2009, 113, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselius, L.J.; E Nelson, M.; Skikne, B.S. Increased release of ferritin and iron by iron-loaded alveolar macrophages in cigarette smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 150, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Priori, R.; Alessandri, C.; Astorri, E.; Perricone, C.; Blank, M.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Valesini, G. sCD163 in AOSD: a biomarker for macrophage activation related to hyperferritinemia. Immunol. Res. 2014, 60, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, A.; Corsi, B.; Levi, S.; Santambrogio, P.; Biasiotto, G.; Arosio, P. Analysis of the biologic functions of H- and L-ferritins in HeLa cells by transfection with siRNAs and cDNAs: evidence for a proliferative role of L-ferritin. Blood 2004, 103, 2377–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, D.; Powell, L.W.; Halliday, J.W.; Fargion, S.; Cappellini, M.D.; Fracanzani, A.L.; Levi, S.; Arosio, P. Functional roles of the ferritin receptors of human liver, hepatoma, lymphoid and erythroid cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1992, 47, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.T.; Li, L.; Chung, D.-H.; Allen, C.D.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M.; Cyster, J.G.; Chen, C.-Y.; Brodsky, F.M.; Niemi, E.C.; et al. TIM-2 is expressed on B cells and in liver and kidney and is a receptor for H-ferritin endocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Paragas, N.; Ned, R.M.; Qiu, A.; Viltard, M.; Leete, T.; Drexler, I.R.; Chen, X.; Sanna-Cherchi, S.; Mohammed, F.; et al. Scara5 Is a Ferritin Receptor Mediating Non-Transferrin Iron Delivery. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieracci, F. M., Barie, P. S. Iron and the risk of infection. Surg. Infect (Larchmt.) 2005, 6 (Suppl. 1), S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, K. G., Williams, P. H. Iron uptake mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letendre, E.D.; E Holbein, B. Mechanism of impaired iron release by the reticuloendothelial system during the hypoferremic phase of experimental Neisseria meningitidis infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 1984, 44, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazawal, S.; Black, R.E.; Kabole, I.; Dutta, A.; Dhingra, U.; Ramsan, M. Effect of Iron/Folic Acid Supplementation on the Outcome of Malaria Episodes Treated with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine. Malar. Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.; Dunn, D. Etiology of Hypoferremia in a Recently Sedentary Kalahari Village. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 48, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Hernández, X.; Licéaga, J.; McKay, I.C.; Brock, J.H. Induction of hypoferremia and modulation of macrophage iron metabolism by tumor necrosis factor. Lab. Invest. 1989, 61, 319–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corna, G.; Campana, L.; Pignatti, E.; Castiglioni, A.; Tagliafico, E.; Bosurgi, L.; Campanella, A.; Brunelli, S.; Manfredi, A.A.; Apostoli, P.; et al. Polarization dictates iron handling by inflammatory and alternatively activated macrophages. Haematologica 2010, 95, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recalcati, S.; Locati, M.; Marini, A.; Santambrogio, P.; Zaninotto, F.; De Pizzol, M.; Zammataro, L.; Girelli, D.; Cairo, G. Differential regulation of iron homeostasis during human macrophage polarized activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, M.; Nairz, M.; Schroll, A.; Schrettl, M.; Haas, H.; Weiss, G. Effects of the Aspergillus fumigatus siderophore systems on the regulation of macrophage immune effector pathways and iron homeostasis. Immunobiology 2008, 213, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leimberg, M.J.; Prus, E.; Konijn, A.M.; Fibach, E. Macrophages function as a ferritin iron source for cultured human erythroid precursors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 103, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijn, A. M., Carmel, N., Levy, R., Hershko, C. Ferritin synthesis in inflammation. II. Mechanisms of increased ferritin synthesis. Br. J. Haematol. 1981, 49, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, E. L., Larochelle, D. A., Beaumont, C., Torti, S. V., Torti, F. M. Role for NF-kappa B in the regulation of ferritin H by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 152285. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, C. G, Bubici, C., Zazzeroni, F et al. Ferritin heavy chain upregulation by NF-kappaB inhibits TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by supressing reactive oxigen species. Cell 2004, 119, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Miller, S.C.; Tsuji, Y.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Interleukin 1 induces ferritin heavy chain in human muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 169, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. T., Andriotakis, J. L., Lacroix, L., Durmowicz, G. P., Kassachau, K. D., Bridges, K. R. Translational enhancement of H-ferritin mRNA by interleukin-1 beta acts through 5’ leader sequences distinct from the iron responsive element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddell, R. G., Hoang-Le, D., Barwood, J. M. et al. Ferritin functions as a proinflammatory cytokine via iron-independent protein-kinase C zeta/nuclear factor kappaB-regulated signaling in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 2009, 49, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, P.; Di Benedetto, P.; Berardicurti, O.; Panzera, N.; Grazia, N.; Lizzi, A.R.; Cipriani, P.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Giacomelli, R. Pro-inflammatory properties of H-ferritin on human macrophages, ex vivo and in vitro observations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarjou, A.; Black, L.M.; McCullough, K.R.; Hull, T.D.; Esman, S.K.; Boddu, R.; Varambally, S.; Chandrashekar, D.S.; Feng, W.; Arosio, P.; et al. Ferritin Light Chain Confers Protection Against Sepsis-Induced Inflammation and Organ Injury. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brands, X., van Engelen, Tjiske S. R., de Vries, Floris M. C. et al. Association of Hyperferritinemia With Distinct Host Response Aberrations in Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. The Journal of Infectious Disease 2022, 225, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, K., Oseko, F., Morikawa, S. H- and L-rich ferritins suppress antibody production, but not proliferation, of human B lymphocytes in vitro. Blood 1994, 83, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, H.-W.L.; Stahlhut, M.W.; Lee, S.; London, W.T.; Hann, R.S. Effects of isoferritins on human granulocytes. Cancer 1989, 63, 2492–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Broxmeyer, H.; Bognacki, J.; Dorner, M.H.; de Sousa, M. Identification of leukemia-associated inhibitory activity as acidic isoferritins. A regulatory role for acidic isoferritins in the production of granulocytes and macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 1981, 153, 1426–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]