1. Introduction

A record number of studies have been conducted on myocardial revascularization in SCAD [

1], but despite this, the choice between a conservative and invasive strategy in a particular patient remains a complex and controversial issue. The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines containing sections on myocardial revascularization in SCAD (chronic coronary syndromes [CCS], in ESC terminology) published with an interval of one year [

2,

3], differ significantly. The recently completed large-scale randomized clinical trial (RCT) ISCHEMIA and the ongoing ISCHEMIA-EXTEND trial provide new evidence for treatment selection in SCAD that conflicts with the current guidelines. Moreover, the published results of ISCHEMIA have already become the subject of a new hot discussion. In this article, we analyze the appropriateness of myocardial revascularization to improve prognosis and symptoms in SCAD and compare the statements of the current Guidelines and the new research data.

2. Summary of guidelines on myocardial revascularization before ISCHEMIA

The most significant recommendations on which clinical decision-making in practice has been based in the last decade were the European Guidelines on myocardial revascularization [

2], the ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes [

3] and the American Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease [

4]. Revascularization is performed to alleviate the ischemic symptoms or to improve the prognosis.

The indications for revascularization available in the listed sources are summarized below (

Table 1 and text).

Classes of recommendations are specified according to the usual definition. Angiographically significant lesions (≥50% for the left main coronary artery and ≥70% for other lesions) are implied throughout the text. The prognostic benefit of revascularization is shown in most cases only for CABG; most clinical scenarios for revascularization to improve prognosis by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are Class IIb recommendations.

European revascularization Guidelines [

2] are very similar. There, the Class I and IIa indications for myocardial revascularization to improve prognosis are high-risk coronary lesions: left main coronary artery (LMCA) disease; proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (LAD); two or three vessel disease in patients with significantly depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) of <35%; stenosis of the last patent coronary artery. Also inducible ischemia of a large (>10% of the left ventricle [LV] area) during stress test is an indication for the coronary intervention. To improve symptoms, revascularization is recommended in the presence of hemodynamically significant coronary artery stenosis, if the patient has limiting angina or the angina equivalent (dyspnea), with an insufficient response to OMT while considering the patient’s preference. Revascularization of stenosis is warranted if it is >90% by angiography or if 50-90%, when 1) ischemia of >10% LV area is induced in this coronary territory at an imaging stress test, or 2) measurement of FFR / instantaneous wave-free ratio (iwFR) gives a result of ≤ 0.80 or ≤0.89, respectively.

However, the ESC Guidelines on CCS [

3] state in contrast that an invasive strategy may improve prognosis in any hemodynamically significant lesion. According to this document, revascularization may be considered in a patient who is asymptomatic (i.e., for prognostic purposes) when 1) ischemia is confirmed by a stress test and the area of inducible ischemia is >10% of the LV, or 2) when the stress test is negative or not done, in the presence of stenosis of any localization if hemodinamically significant (defined as above); revascularization should also be considered with EF <35% as a result of coronary artery disease. Also, revascularization may be indicated to improve symptoms in a patient with angina and confirmed myocardial ischemia.

Although these Guidelines for a long time used to be the basis of clinicial decision-making, they are controversial. Also, statements on the prognostic benefit of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in individuals with high-risk coronary lesions and reduced EF are based on observational data from the 1980s and 1990s, conducted before the era of modern optimal medical therapy (OMT) [

5]. The prognostic advantage of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) over OMT was, in fact, shown in the FAME 2 study only, where revascularization was performed after confirming the hemodynamic significance of stenosis by measuring the FFR [

6]. These data are the basis of the latest version of the European recommendations [

3]. Nevertheless, FAME 2 failed to show differences in the "hard" endpoints of cardiac death/acute myocardial infarction (AMI)/confirmed unstable angina. The only parameter in which the invasive strategy showed superiority was acute coronary syndrome not confirmed by ECG/biomarkers. The explanation for this is the increased alertness of patients in the ‘conservative’ group of the FAME2 study (and their attending physicians) regarding any suspicious symptoms in a situation where the presence of significant stenosis was proven by FFR, and revascularization, which in this case ‘should’ be performed, was not performed due to the conditions of the trial [

7]. On the other hand, in the extended (5-year) follow-up of the FAME 2 cohort [

8], the authors did show the advantage of PCI in terms of less urgent revascularization and spontaneous AMI. Obviously, if PCI of significant stenosis really prevents AMI, this conflicts with the existing idea of the predominant development of atherothrombosis at the site of an insignificant “vulnerable” atherosclerotic plaque [

9].

3. Myocardial revascularization: evidence from new studies

3.1. Myocardial revascularization in SCAD and prognosis

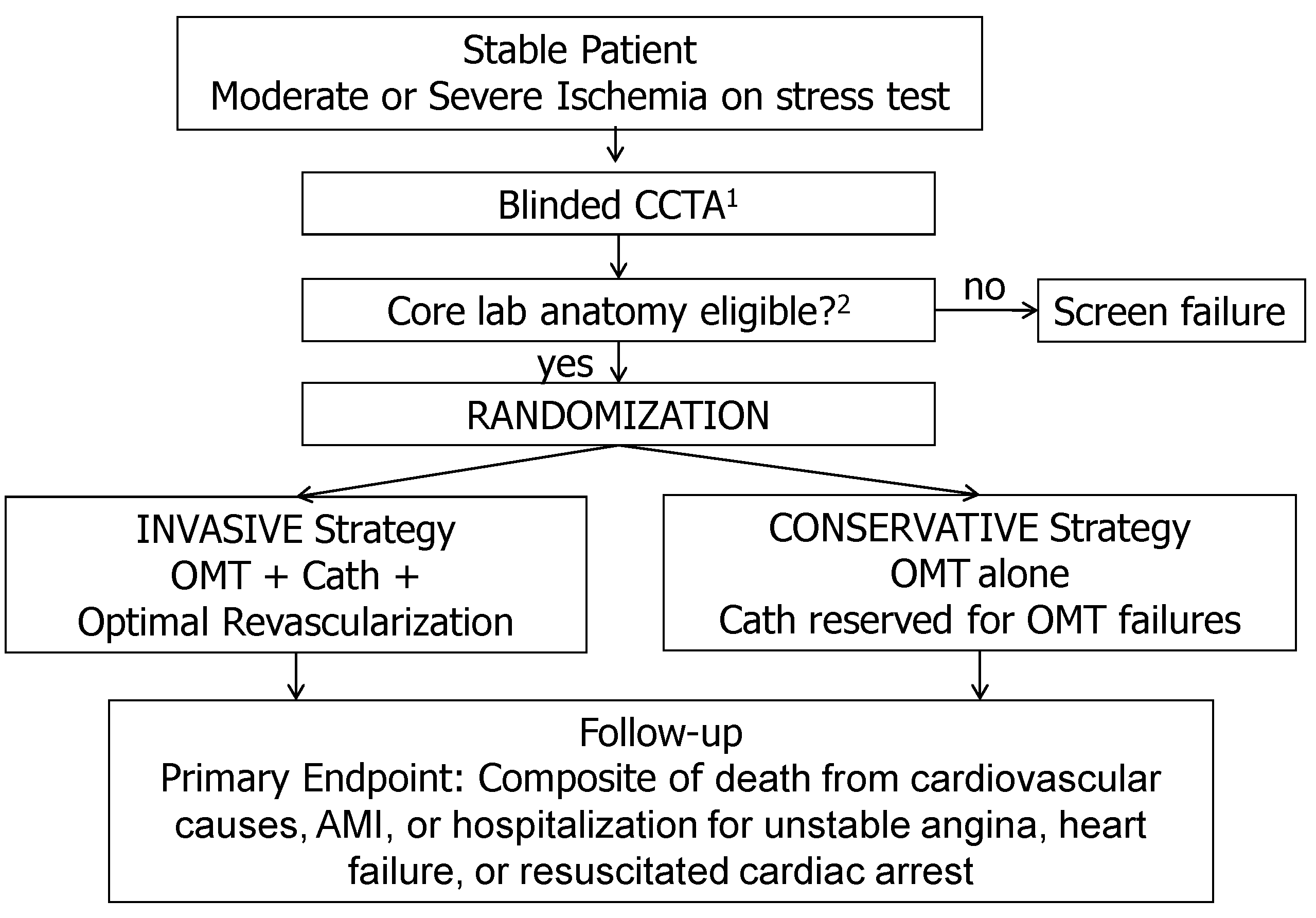

The ISCHEMIA study (NCT01471522) was the largest RCT (n=5179) comparing an invasive and conservative strategy in patients with SCAD receiving contemporary medical therapy and PCI /CABG performed by contemporary approaches [

10,

11]. The study enrolled patients with a positive stress test of moderate or high risk. In 75% of cases this was an imaging stress tests. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) was performed to confirm the presence of obstructive (>50%) coronary artery disease, with LMCA involvement being the exclusion criterion. CCTA data were analyzed by the central laboratory and were not disclosed to the attending physician. Other major exclusion criteria were: absence of significant coronary artery stenosis; coronary anatomy, not allowing PCI or CABG; EF <35% (mean EF of the enrolled patients was about 60%). Patients were randomized into groups of conservative or invasive therapy, the last to undergo invasive coronary angiography and revascularization (

Figure 1).

The type of revascularization was determined according to standard criteria, taking into account the SYNTAX score, surgical risk, comorbidity, physician’s and patient's preferences [

1,

3]. Despite favorable RCT conditions, at the end of 3+ years follow-up, only 41% of patients received true OMT (achievement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL cholesterol] <1.8 mmol/L, treatment with any statin, systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg, treatment with antithrombotic drug and no smoking), and the proportion of participants with a target level of LDL-C was 59%. As a method of revascularization, PCI using drug-eluting stents was performed in 74%, CABG - using predominantly mammary grafts - in 26% of participants.

The 7-item version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) was used to assess symptoms [

12,

13].

The most important result of the ISCHEMIA study was the absence of statistically significant difference between the invasive and conservative strategies in the cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events: adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the invasive strategy 0.93 (95% CI 0.80-1.08; p=0 .34). It should be noted that 2 years after the start of the follow-up, the event curves intersected, so that at the end of the observation there were more events in the conservative strategy group (

Table 2) [

11,

12].

The incidence of death from all causes in both groups was low: 145 (5.6%) in the invasive group and 144 (5.6%) in the conservative group (adjusted HR 1.05; 95% CI 0.83-1.32 ; p=0.67). There were more periprocedural AMI in the invasive group (adjusted HR 2.98; 95% CI 1.87-4.74; p<0.01), while less spontaneous AMI by 33% (adjusted HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53-0.87, p<0.01).

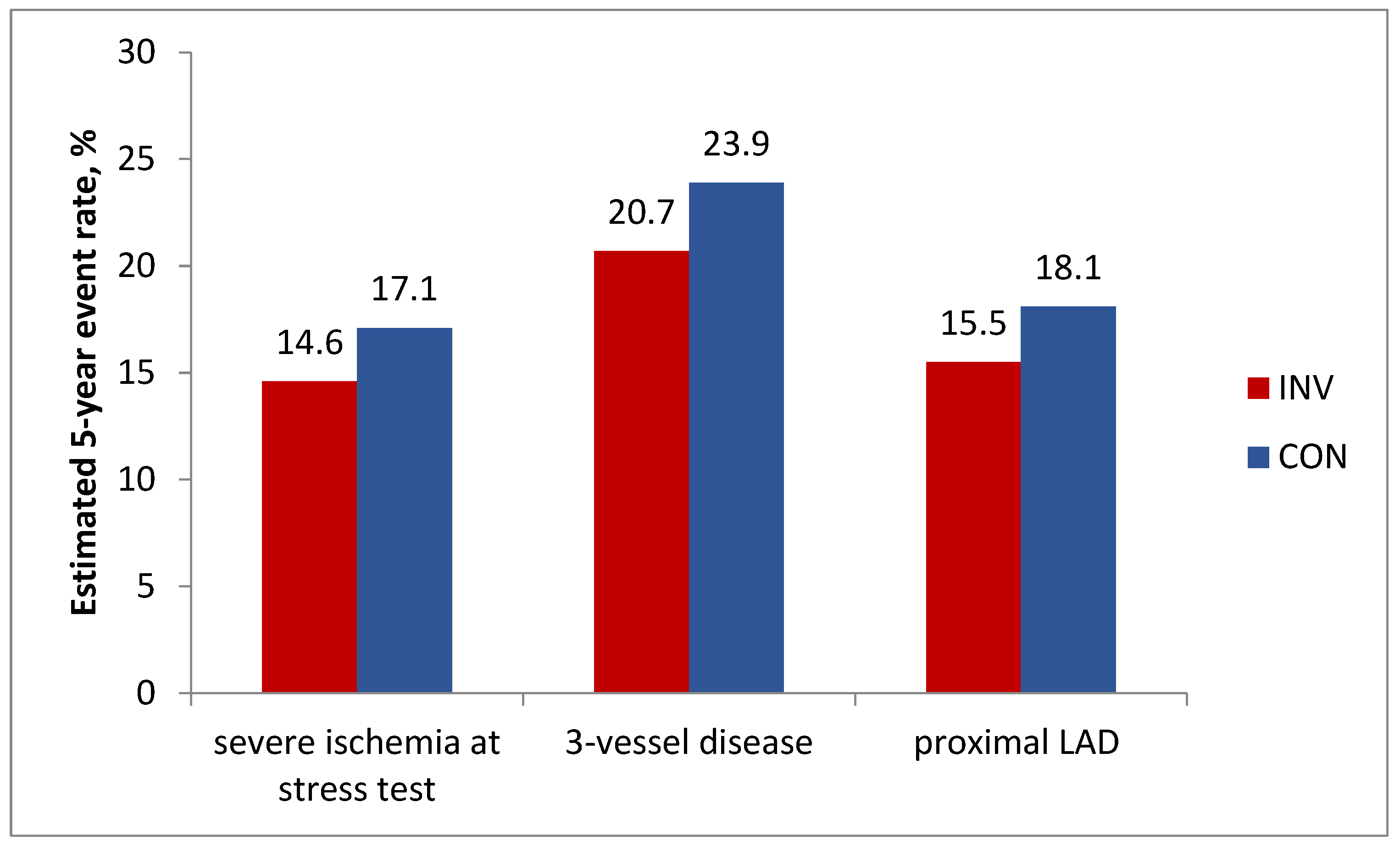

In addition, analyzes in prespecified important subgroups showed no benefit of an invasive strategy regarding the primary endpoint in patients with severe stress-induced ischemia, 3-vessel disease, or proximal LAD disease (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

ISCHEMIA, analysis in prespecified important subgroups: Estimated 5-year cumulative primary endpoint rate, % by treatment strategy. P>0.05 for all comparisons.

Figure 2.

ISCHEMIA, analysis in prespecified important subgroups: Estimated 5-year cumulative primary endpoint rate, % by treatment strategy. P>0.05 for all comparisons.

The differences in the incidence of events between the invasive and conservative groups for these subgroups of patients were, respectively -2.6% (95% CI -6.3 – 1.2); -3.2% (95% CI -9.5 – 3.2); -2.6% (95% CI -7.5 – 2.3); p>0.05 for all.

3.2. Analysis of the severity of ischemia during a stress test and the severity of coronary disease as predictors of the prognostic benefit of an invasive strategy

To further explore the effect of ischemia severity and CAD severity on the primary endpoint, separate post-hoc analyzes were performed. The first one showed that the 4-year rates of all-cause mortality, spontaneous AMI or the trial primary composite end point (cardiovascular death, hospitalization for heart failure, or hospitalization for unstable angina) were not statistically different between stress-induced ischemia subgroups [

14]. For example, in patients with severe ischemia at the stress test, all-cause mortality was 6.1 (95% CI, 4.7 to 7.8) in invasive group vs 5.6 (95% CI, 4.2 to 7.1) in conservative group; respectively, cardiovascular death was 3.7 (95% CI 2.6 to 5.0) vs 4.5 (95% CI, 3.3 to 6.0); spontaneous AMI occurred in 5.7 (95% CI, 4.4 to 7.3) vs 8.3 (95% CI, 6.8 to 10.0); all p values for interaction non significant.

In the second analysis of the 4-year cumulative event rates by CAD severity and treatment assignment (in which only 48% of randomized participants could be included because CCTA was not done in low glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and image quality was insufficient in some participants) the CAD–by –treatment strategy interaction P value for 4-year event rates was also >0.05 [

14]. In the subgroup of participants with modified Duke Prognostic Index score of 6 (ie, 3-vessel severe stenosis (≥70%) or 2-vessel severe stenosis with proximal LAD), the 4-year estimated rate of all-cause mortality in the invasive and conservative groups were equal at 7.7%. In the same subgroup, the 4-year estimated rate of cardiovascular death was 3.7 (95% CI, 1.9 to 6.4) in the invasive group vs 6.7 (95% CI, 3.9 to 10.5) in the conservative group. Finally, the 4-year estimated rate of spontaneous AMI was 5.4 (95% CI, 3.1 to 8.6) vs 10.2 (7.0 to 14.0) respectively; all p values for interaction non significant.

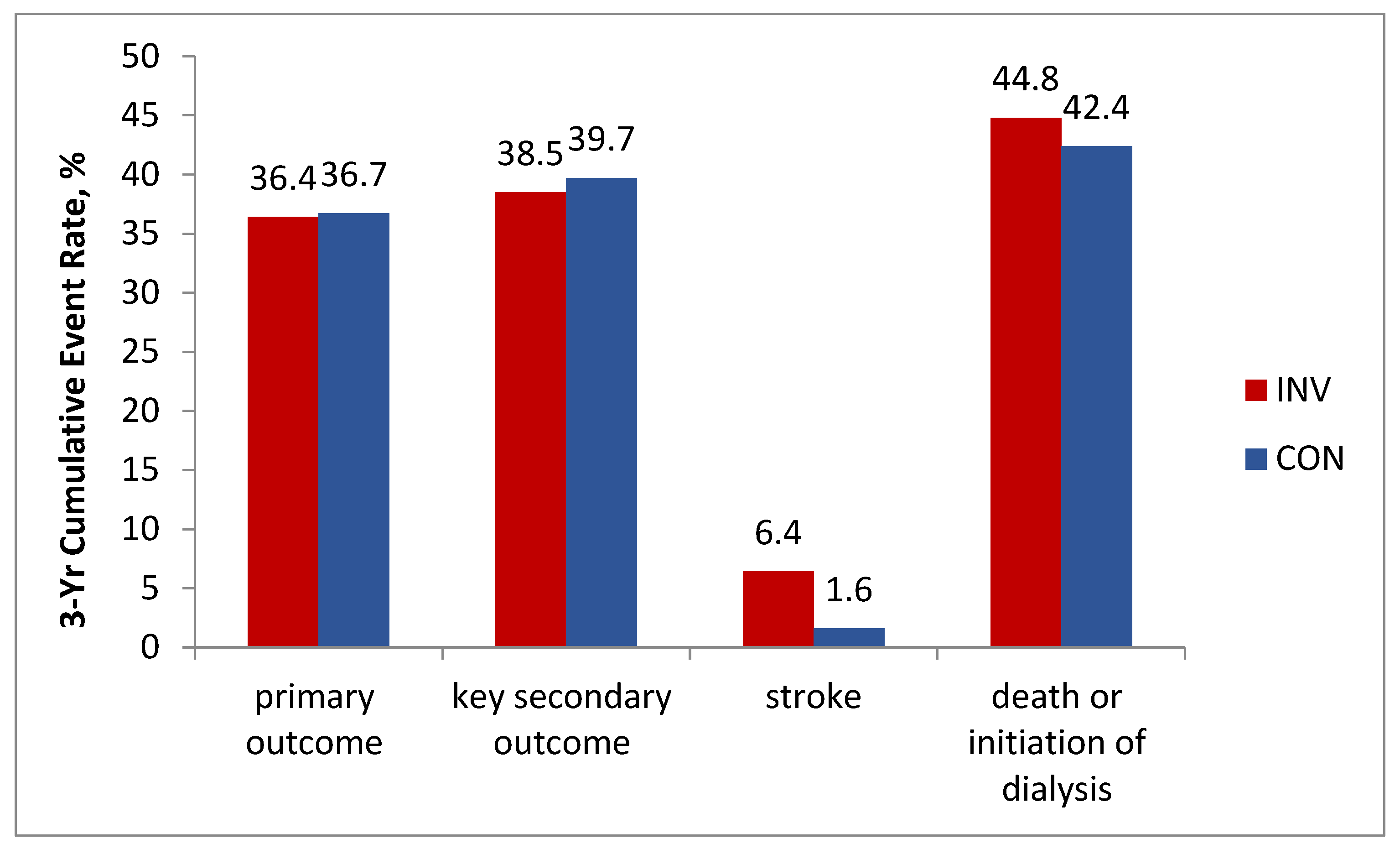

4. ISCHEMIA-CKD

Severe CKD is usually an exclusion criterion in studies of patients with SCAD. Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in patients with CKD [

15]. On the other hand while about 30% to 40% of all patients undergoing PCI have concomitant CKD, data on the optimal treatment strategies in this population remained scarce [

16]. ISCHEMIA-CKD substudy enrolled patients with advanced kidney disease (defined as an estimated eGFR of <30 ml per minute per 1.73 m

2 of body-surface area or being on dialysis) otherwise qualifying for the ISCHEMIA selection criteria [

17]. According to the ISCHEMIA-CKD results, at a median follow-up of 2.2 years, an estimated 3-year event rate of the primary outcome event rate was 36.4% in invasive vs. 36.7% in conservative group; adjusted HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.29; P = 0.95. Results for the key secondary outcome (composite of death, nonfatal AMI or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest) were also not in favor of the invasive strategy: 38.5% vs. 39.7%; adjusted HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.29. Moreover, the patients in the invasive group demonstrated a higher incidence of stroke (adjusted HR, 3.76; 95% CI, 1.52 to 9.32; P = 0.004) and a higher incidence of death or initiation of dialysis (adjusted HR, 1.48 ; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.11; P = 0.03) (

Figure 3).

Thus in SCAD patients with advanced CKD the invasive strategy did not prove beneficial and could be harmful.

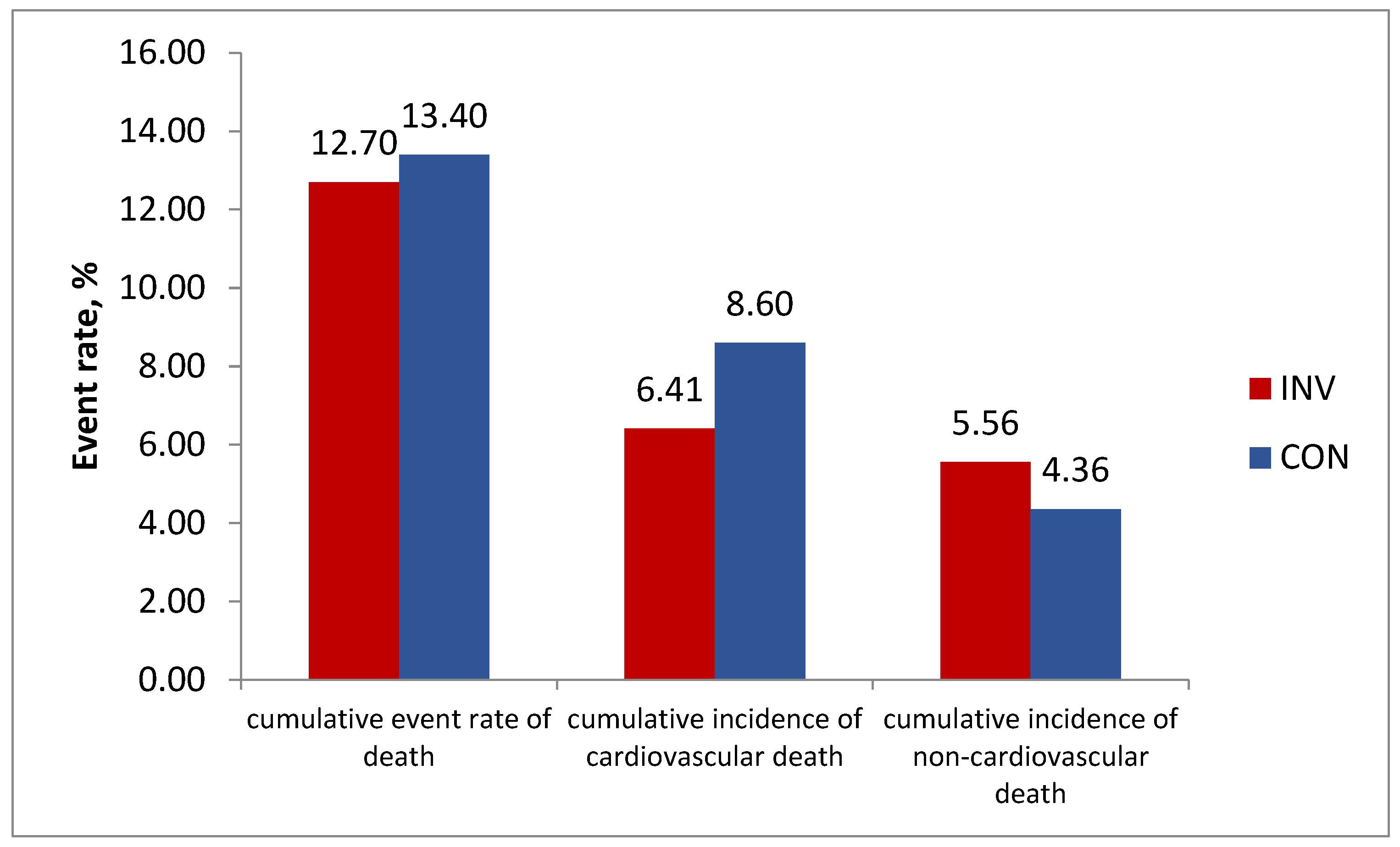

5. Interim results of ISCHEMIA-EXTEND

The primary endpoint rate crossover in the ISCHEMIA study which occurred in the middle of the follow-up, with a statistically insignificant trend towards the advantage of the invasive strategy, urged the study leadership to organize an ISCHEMIA-EXTEND trial (NCT04894877) [

18], resulting in an increase in the total follow-up duration to 7 years.

The data published recently show the lower long-term cardiovascular mortality at 7 years in the invasive vs conservative group (6.41% vs 8.60%, difference –2.19% (95%CI, –3.85% to –0.53%) and higher non-cardiovascular mortality (respectively, 5.56% vs 4.36%, difference 1.20% (95%CI, –0.32% to 2.72%). This resulted in equal total mortality rate in the both groups: respectively 12.70% vs 13.40% (difference –0.70% ( 95% CI, –2.95% to 1.56%) (

Figure 4).

The authors also found the absence of significant interaction on the total mortality between the presence or absence of multivessel CAD and the randomized initial strategy. Cumulative all-cause mortality rate for participants with multivessel disease (MVD) was not lower with the invasive versus conservative management strategy: adjusted HR 0.89 (95% CI, 0.67-1.19). However, the statistically significant benefit of invasive strategy could be demonstrated for cardiovascular mortality in patients with MVD, adjusted HR 0.68 (95%CI, 0.48-0.97), in contrast to the finding in the prespecified subgroups analysis of the main study. Meanwhile non-cardiovascular mortality tended to be higher in MVD patients (adjusted HR 1.52 (95%CI, 0.88-2.63). Unfortunately, no data were collected on nonfatal events after the initial median 3.2-year follow-up. Due to the trend to better cardiovascular outcome with the invasive strategy, predominantly in MVD, the ISCHEMIA-EXTEND group plan to continue to follow surviving participants into 2025 for a projected median of 10 years. As for the higher rate of noncardiovascular death in the invasive group, the authors note it was unexpected and remains unexplained. The previous analysis showed more malignancy deaths (2.0% vs 0.8%; HR 2.11 [1.23-3.60]) with the invasive strategy than with the conservative strategy [

19], though the mechanism of this remains unclear and not related to the radiation exposure of dual antiplatelet therapy [

18].

5.1. Myocardial revascularization and symptoms of ischemia in SCAD

Despite the lack of a convincing effect on prognosis, the effect of treatment strategy on symptoms has been shown [

12]. The subjective improvement in symptoms of patients after randomization was more pronounced in participants in the invasive strategy group, and the difference persisted throughout the entire follow-up period (thus, the average total SAQ scores compared with the conservative strategy group were 84.7±16.0 vs. 81.8±17 .0 after 3 months; 87.2±15.0 vs. 84.2±16.0 after 12 months; 88.6±14.0 vs. 86.3±16.0 after 36 months).

6. Discussion

The problem of treatment strategy selection in SCAD remains one of the major controversial issues in clinical practice. The current role of revascularization has been extensively explored in the ISCHEMIA study, the largest RCT to date in patients with SCAD, and continued in the ISCHEMIA-EXTEND study. The ISCHEMIA design had a number of important advantages:

- randomization occurred in the absence of information about the coronary angiography data, resulting in the inclusion of a significant number of patients with high-risk lesions

- moderately or strongly positive stress test was the inclusion criterion. As a result, ISCHEMIA patients were quite ‘ill’ as judged by the results of the stress test (in contrast to the COURAGE trial participants [

20]), while in such patients the invasive strategy, should theoretically have the greatest advantage over the conservative one [

3].

- only 2nd generation drug-eluting stents were used and FFR was assessed in borderline lesions. As a result, revascularization of physiologically significant lesions was performed in most cases, similar to the FAME 2 study, which showed the prognostic advantage of an invasive strategy with this approach [

8].

- as a method of revascularization, both PCI and CABG were used, the latter with the mammary grafts as a rule (PCI only in COURAGE and FAME 2).

- for the diagnosis of unstable angina during follow-up, objective confirmation was required, the absence of which is considered the reason for the debatable results of the FAME 2 study [

7].

As a result, high-risk patients were included both in terms of functional and anatomical criteria, and invasive treatment was carried out at the optimal modern level. At the same time, even by the end of the follow-up, OMT was not ideal with only 41% of patients receiving ’true’ OMT, and the target LDL-C value was more liberal than at present.

It was under these conditions that important results of the study were obtained:

An invasive strategy, compared with a conservative strategy, did not result in lower risk of the primary endpoint.

Low mortality was observed with both strategies including the conservative strategy, in the population of patients with severe coronary artery disease. It was 5.5% per 3.2 years of follow-up, i.e. about 1.7% / year - which is about half as much as calculated for patients of this risk level on the stress test [

4].

Invasive strategy showed no prognostic benefit in the prespecified important subgroups (strongly positive stress test; 3-vessel disease; proximal LAD disease). The advantage of an invasive strategy in the prevention of spontaneous AMI could be shown.

An advantage of an invasive strategy in reducing the symptoms of ischemia has been shown.

The main limitation of the ISCHEMIA study is the ‘crossover’ of the event curves for all major endpoints at 2 years after randomization, after which there was a trend towards an increase in the number of events in the conservative group. In addition, the analysis of outcomes in the most important ‘controversial’ subgroups (item 3 above) was secondary, and the analysis of outcomes separately for types of revascularization (PCI and CABG) has not yet been published. Finally, patients with lesions of the LMCA and EF <35%, as well as those with end-stage CKD, were not included in the study. At the same time, according to the analysis of the American Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), among patients with SCAD undergoing PCI, 18.5% have a decreased EF, left main disease or CKD stage 5 [

21]. It should be noted, however, that the question of the appropriateness of revascularization to improve prognosis in patients with severe CKD was answered (negatively) in the ISCHEMIA-CKD sub-study.

The ISCHEMIA results are consistent with other new studies and meta-analyses. In particular, prolonged (for 15 years) follow-up of COURAGE participants showed no reduction in mortality after PCI in 3-vessel coronary artery disease - it was 50% and 53% for medical treatment and PCI, respectively [

22]. Similarly, in patients with a high-risk stress test, at 15 years these rates were 44% and 50%, respectively (all differences non-significant).

In a large meta-analysis (14 RCTs with a total of 14,877 participants, mean follow-up 4.5 yr), revascularization (PCI or CABG) did not reduce the risk of death compared to conservative therapy alone (HR 0.99 [95% CI 0.90–1.09]) [

23]. Revascularization reduced the risk of spontaneous MI (HR 0.76 [95% CI 0.67–0.85]) but increased the incidence of periprocedural MI (HR 2.48 [95% CI 1.86–3.31]). Finally, revascularization increased the likelihood of freedom from angina by 10% (HR 1.10 [95% CI 1.05–1.15]).

An additional follow-up of ISCHEMIA participants (ISCHEMIA-EXTEND) up to 7 years confirmed the conclusion of the main study that there was no benefit of the invasive strategy in terms of overall mortality. This resulted from the opposite effects of a statistically significant decrease in cardiovascular mortality found in the invasive group (probably as a result of a decrease in the frequency of spontaneous AMI observed in the early period of follow-up) with a parallel unexpected increase in non-cardiac, apparently oncological, mortality. The significance of these data has yet to be assessed.

Table 3.

Indications for revascularization in patients with SCAD: European Guidelines versus ISCHEMIA data.

Table 3.

Indications for revascularization in patients with SCAD: European Guidelines versus ISCHEMIA data.

| Current European Guidelines |

New research |

| For prognosis |

| LMCA disease |

? |

| Proximal LAD involvement |

Х |

| 2- or 3- vessel disease |

Х |

| Large area of inducible ischemia (> 10% of the left ventricle) |

Х |

| EF < 35% |

? |

| For ischemic symptoms |

| Hemodynamically significant coronary artery stenosis in the presence of limiting angina or angina equivalent, with insufficient response to OMT |

✓ |

Based on the results of ISCHEMIA, the American Cardiology Societies issued the new Clinical Guidelines [

16], where only 3-vessel disease with reduced EF, as well as LMCAdisease - i.e. subgroups of patients that are almost not represented in ISCHEMIA - are left as Class I / IIa indications for revascularization in SCAD.

At the same time, revascularization by CABG in patients with 3-vessel disease and preserved EF received a Class IIb recommendation. In this regard, the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons issued their statements disagreeing with this conclusion. As an argument they indicate that this conclusion in the Guidelines is based on a subgroup analysis of the RCT, which itself is not randomized. Moreover, a separate analysis of the predictive value of revascularization depending on its type has not been published at the time of publication of the Guidelines [

24,

25]. It could be added that the finding of lower cardiovascular mortality with invasive strategy in patients with MVD in ISCHEMIA-EXTEND is an argument for the invasive strategy, though its effect on non-cardiovascular mortality in these patient group was not separately described.

7. Conclusion

The ISCHEMIA study generally demonstrated no prognostic benefit of a primary invasive strategy for individuals with SCAD and a moderate-to-high-risk stress test on current OMT for the cumulative cardiovascular endpoint. No advantage of revascularization regarding all-cause mortality was confirmed in the ISCHEMIA-EXTEND 7-year interim analysis. Also, revascularization was of no benefit in SCAD patients with advanced CKD.

These findings conflicted with the current European guidelines, and given the size of the study and the high quality of the data, a revision of the recommendations seemed inevitable. However, the new ACC/AHA guidelines for revascularization based on the results of ISCHEMIA were not supported by the cardiac surgery communities regarding the appropriateness of surgical treatment of multivessel lesions. Indeed, conclusions about the insufficient prognostic effect of revascularization in patients with high-risk coronary anatomy are based on secondary analysis. In this regard, conduct of RCT with a direct comparison of invasive and conservative strategies in this category of patients looks justified and substantiated by the results obtained in ISCHEMIA. The appropriateness of invasive approach in patients with MVD should be specifically addressed. The same applies to patients with reduced EF and LMCA lesions, which were not represented in ISCHEMIA. However, at this point it can be concluded that a conservative strategy may be the primary choice for the majority of patients with SCAD who meet the ISCHEMIA eligibility criteria and do not have limiting symptoms.

Funding

Sub-grant: grant U01HL105907 from the U. S. Department of Health Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) dated July 22, 2011, to conduct a multi-site, multi-national clinical investigation entitled ‘International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches’.

References

- Members, T.F.; Windecker, S.; Kolh, P.; Alfonso, F.; Collet, J.; Cremer, J.; Falk, V.; Filippatos, G.; Hamm, C.W.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur. Hear. J. 2014, 35, 2541–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, F.J.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Ahlsson, A.; Alfonso, F.; Banning, A.P.; Benedetto, U.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.P.; Falk, V.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 87–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuuti, J.; Wijns, W.; Saraste, A.; Capodanno, D.; Barbato, E.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Prescott, E.; Storey, R.F.; Deaton, C.; Cuisset, T.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 407–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fihn, S.D.; Gardin, J.M.; Abrams, J.; Berra, K.; Blankenship, J.C.; Dallas, A.P.; Douglas, P.S.; Foody, J.M.; Gerber, T.C.; Hinderliter, A.L.; et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, e44–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bershteyn, L.L.; Zbyshevskaya, E.V.; Katamadze, N.O.; Kuzmina-Krutetskaya, A.M.; Volkov, A.V.; Andreeva, A.E.; Gumerova, V.E.; Bitakova, F.I.; Sayganov, S.A.; Hospital”, S.H. .P. ISCHEMIA – the Largest Ever R andomized Study in Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Baseline Characteristics of Enrolled Patients in One Russian Site. Kardiologiia 2017, 17, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiopoulos, K.; Boden, W.E.; Hartigan, P.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Hambrecht, R.; Hueb, W.; Hardison, R.M.; Abbott, J.D.; Brown, D.L. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Outcomes in Patients With Stable Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Ischemia. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, C.A.; Nijjer, S.S.; Cole, G.D.; Al-Lamee, R.; Francis, D.P. ‘Faith Healing’ and ‘Subtraction Anxiety’ in Unblinded Trials of Procedures. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e004665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xaplanteris, P.; Fournier, S.; Pijls, N.H.; Fearon, W.F.; Barbato, E.; Tonino, P.A.; Engstrøm, T.; Kääb, S.; Dambrink, J.-H.; Rioufol, G.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes with PCI Guided by Fractional Flow Reserve. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, W.C. Angiographic assessment of the culprit coronary artery lesion before acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990, 66, G44–G47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; O’brien, S.M.; Alexander, K.P.; Senior, R.; Boden, W.E.; Stone, G.W.; Goodman, S.G.; Lopes, R.D.; et al. Baseline Characteristics and Risk Profiles of Participants in the ISCHEMIA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, D.J.; Hochman, J.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; O’Brien, S.M.; Boden, W.E.; Chaitman, B.R.; Senior, R.; López-Sendón, J.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spertus, J.A.; Jones, P.G.; Maron, D.J.; O’brien, S.M.; Reynolds, H.R.; Rosenberg, Y.; Stone, G.W.; Harrell, F.E.; Boden, W.E.; Weintraub, W.S.; et al. Health-Status Outcomes with Invasive or Conservative Care in Coronary Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.S.; Jones, P.G.; Arnold, S.A.; Spertus, J.A.; J, S.; J, G.; A, S.; J, S.; W, L.; D, K.; et al. Development and Validation of a Short Version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2014, 7, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, H.R.; Shaw, L.J.; Min, J.K.; Page, C.B.; Berman, D.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Picard, M.H.; Kwong, R.Y.; O’brien, S.M.; Huang, Z.; et al. Outcomes in the ISCHEMIA Trial Based on Coronary Artery Disease and Ischemia Severity. Circ. 2021, 144, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnak, M.J.; Amann, K.; Bangalore, S.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Craig, J.C.; Gill, J.S.; Hlatky, M.A.; Jardine, A.G.; Landmesser, U.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don, C.W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circ. 2022, 145, E4–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangalore, S.; Maron, D.J.; O’brien, S.M.; Fleg, J.L.; Kretov, E.I.; Briguori, C.; Kaul, U.; Reynolds, H.R.; Mazurek, T.; Sidhu, M.S.; et al. Management of Coronary Disease in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Anthopolos, R.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; Xu, Y.; O’brien, S.M.; Mavromichalis, S.; Chang, M.; Contreras, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; et al. Survival After Invasive or Conservative Management of Stable Coronary Disease. Circ. 2023, 147, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, M.S.; Alexander, K.P.; Huang, Z.; O'Brien, S.M.; Chaitman, B.R.; Stone, G.W.; Newman, J.D.; Boden, W.E.; Maggioni, A.P.; Steg, P.G.; et al. Causes of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death in the ISCHEMIA trial. Am. Hear. J. 2022, 248, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, W.E.; O'Rourke, R.A.; Teo, K.K.; Hartigan, P.M.; Maron, D.J.; Kostuk, W.J.; Knudtson, M.; Dada, M.; Casperson, P.; Harris, C.L.; et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://scai.confex.com/scai/2021/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/14413.

- Weintraub, W.S.; Hartigan, P.M.; Mancini, G.J.; Teo, K.K.; Maron, D.J.; Spertus, J.A.; Chaitman, B.R.; Shaw, L.J.; Berman, D.; Boden, W.E.; et al. Effect of Coronary Anatomy and Myocardial Ischemia on Long-Term Survival in Patients with Stable Ischemic Heart Disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangalore, S.; Maron, D.J.; Stone, G.W.; Hochman, J.S. Routine Revascularization Versus Initial Medical Therapy for Stable Ischemic Heart Disease. Circ. 2020, 142, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, P.; Beyersdorf, F.; Sadaba, R.; Milojevic, M. European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Statement regarding the 2021 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Coronary Artery Revascularization guidelines. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2022, 62, ezac060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabik, J.F.; Bakaeen, F.G.; Ruel, M.; Moon, M.R.; Malaisrie, S.C.; Calhoon, J.H.; Girardi, L.N.; Guyton, R. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons reasoning for not endorsing the 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Coronary Revascularization Guidelines. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 163, 1362–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).