1. Introduction

With the rapid development of information technology and the widespread application of the Internet, a large amount of Chinese address text has become ubiquitous in our daily lives. Address information plays a crucial role in these texts [

1,

2], encompassing various address components such as country, city, street, and building numbers. Accurate parsing and extraction of these address components are essential for natural language processing tasks and building geographic information systems [

3,

4].

Chinese address parsing is the process of breaking down Chinese address text into independent semantic components and identifying their types. It is an important task in the field of natural language processing [

5,

6,

7]. However, Chinese addresses have complex structures and semantic features, posing challenges to this task [

8]. One challenge is the polysemy and ambiguity of address components, where the same component may have different meanings in different contexts. For example, consider the address “公园道一号2期1号楼4楼东403户” (Building 1, Floor 4, Room 403, East, Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1). This address comprises multiple address components, including “公园道一号2期” (Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1) as the neighborhood, “1号楼” (Building 1) as the building number, “4楼” (Floor 4) as the floor number, and “东403户” (Room 403, East) as the room number. However, the address component “公园道一号” (Park Road No. 1) can easily be mistaken as a street number, while it actually represents the name of a community. This polysemy and ambiguity add to the difficulty of Chinese address parsing.

Furthermore, different task scenarios require different granularities of address component segmentation [

9], often involving customized address components. For instance, in some task scenarios, it is sufficient to recognize “公园道一号2期”(Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1) as a single part of the address without further subdivision.

Importantly, Chinese address parsing faces resource limitations in many application scenarios, lacking sufficient annotated data, unlabeled data, and limited computational resources. This poses significant challenges to applying large-scale language models. Due to data constraints or domain-specific limitations, available training data and resources are typically limited, making Chinese address parsing under low-resource[

10] conditions even more challenging.

With the enhanced capabilities of large-scale language models (LLMs), [

11], In-Context Learning (ICL) has emerged as a new paradigm in the field of natural language processing [

12,

13]. The ICL approach involves connecting queries or prompts with contextual demonstrations to create a comprehensive prompt, which is then inputted to a language model for prediction. Unlike supervised learning, ICL does not require updating model parameters but leverages pre-trained language models for inference.

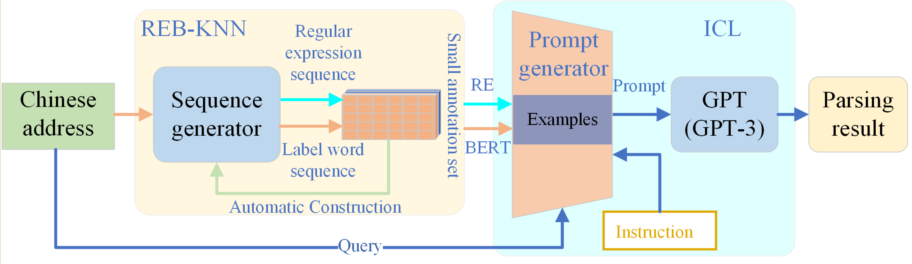

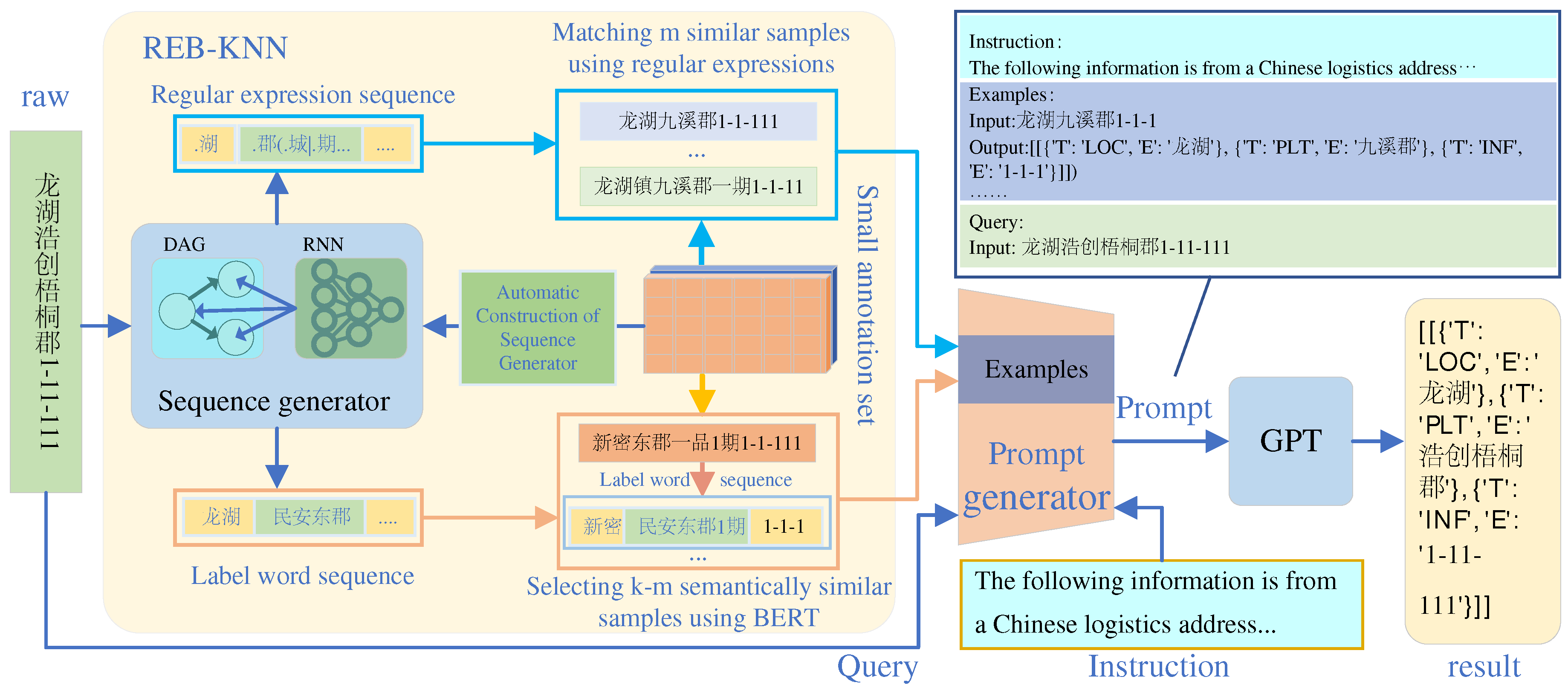

Thus, it is evident that ICL has inherent advantages in addressing the challenges of Chinese address parsing. It reduces dependence on external knowledge and annotated data, while also having lower computational resource requirements. Based on the advantages of ICL, we propose a low-resource Chinese address parsing method called CapICL. This method fully leverages the capabilities of in-context learning to address challenges under resource limitations. The overall architecture of The CapICL model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The CapICL model utilizes a sequence generator to convert the raw text into two key sequences: regular expression sequence and label word sequence. The regular expression sequence captures the boundary features and distribution patterns of address components, while the label word sequence unifies different types of address components, reducing unnecessary interference caused by variations. Based on these two sequences, we introduce the REB-KNN algorithm, which effectively selects samples by combining the advantages of regular expression matching and BERT-based semantic similarity calculation. Experimental results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of this integrated approach, enhancing the model’s ability to guide questions and adapt to tasks.

Our work makes the following significant contributions:

We propose CapICL, an innovative low-resource Chinese address parsing model, to address the challenges in Chinese address parsing. The key component of our model is the sequence generator, which is constructed using a small annotated dataset. By capturing the distribution patterns and boundary features of address types, the sequence generator effectively models the structure and semantics of addresses, mitigating interference from unnecessary variations.

We introduce an integrated approach that combines regular expression matching and BERT-based semantic similarity computation to enhance the performance of Chinese address parsing. The regular expression matching captures specific patterns inherent in address components, while the BERT-based semantic similarity computation measures the semantic relatedness between different address components. This comprehensive approach achieves significant improvements in address parsing accuracy, particularly in low-resource scenarios.

Compared to traditional methods of fine-tuning large-scale language models, our proposed CapICL model offers a higher cost-effectiveness. By leveraging the sequence generator to maximize the utilization of existing resources and knowledge, our approach eliminates the need for additional training or fine-tuning. This enables our model to achieve outstanding performance in Chinese address parsing, even with limited annotated data and computational resources.

Through these contributions, our research provides an innovative solution to address the challenges of Chinese address parsing, achieving significant performance improvements in low-resource environments. Our work not only holds great importance in the field of natural language processing but also demonstrates its positive impact on related fields such as geographical information systems.

The organization of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of related work, including few-shot learning, language model applications, and in-context learning.

Section 3 presents the detailed implementation of our innovative in-context learning-based Chinese address parsing model for low-resource scenarios.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and provides a detailed analysis of the results.

Section 5 expands on the discussion based on the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main contributions of this paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

Address parsing is a challenging task that involves extracting structured information from unstructured addresses. In order to address this task effectively, researchers have explored various techniques and methodologies. In this section, we discuss three areas of related work: Few-shot Learning, Language Models, and In-context Learning, highlighting their relevance to address parsing.

2.1. Few-shot Learning

Few-shot learning techniques [

14] have gained attention as potential solutions to the problem of limited labeled data. These approaches aim to improve model performance by leveraging a small amount of labeled data and other auxiliary information. In the context of address parsing, few-shot learning methods have been explored to enhance the generalization capabilities of models. Techniques such as pre-trained models [

15,

16], transfer learning, and generative models have been utilized to enable models to effectively parse addresses with limited labeled data. Additionally, meta-learning approaches [

17] have been employed to enable models to generalize to new address parsing tasks by learning adaptability across multiple tasks.

2.2. Language Models

Language models, such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer(GPT) [

14] and BERT [

15,

18], have revolutionized the field of natural language processing. These large-scale language models (LLMs) are trained on massive amounts of text data and have demonstrated remarkable success in various NLP tasks. In the context of address parsing, language models have been widely utilized to extract meaningful information from unstructured address text. By pre-training language models on large-scale corpora and fine-tuning them on address parsing tasks, models can effectively learn language representations and capture contextual information, improving the accuracy and robustness of address parsing systems.

2.3. In-Context Learning

In-context learning, also known as contextual learning, has been applied to improve the performance of models in few-shot learning tasks. This methodology utilizes contextual information to assist in model learning and has found applications in various NLP domains, including address parsing. The Instruction-Based Contextual Learning (ICL) approach [

14] provides an interpretable interface for interacting with large-scale language models (LLMs) and facilitates the integration of human knowledge into LLMs by modifying demonstrations and templates [

19,

20]. By leveraging ICL, address parsing models can benefit from the incorporation of human knowledge, leading to improved parsing accuracy.

Furthermore, in-context learning offers a zero-shot learning framework that reduces the computational cost of adapting models to new address parsing tasks. This enables the use of language models as a service, making them applicable to large-scale real-world address parsing scenarios [

21]. The performance of ICL is influenced by specific configurations, such as prompt templates, the selection of contextual examples, and the order of examples [

22,

23]. These configuration choices play a crucial role in achieving optimal address parsing performance within the in-context learning framework.

In summary, the related work in few-shot learning, language models, and in-context learning provides valuable insights and techniques that can be leveraged to enhance the performance of address parsing systems. By employing few-shot learning methods, language models, and incorporating in-context learning strategies, address parsing models can achieve improved accuracy and robustness in extracting structured information from unstructured addresses.

3. Methodology

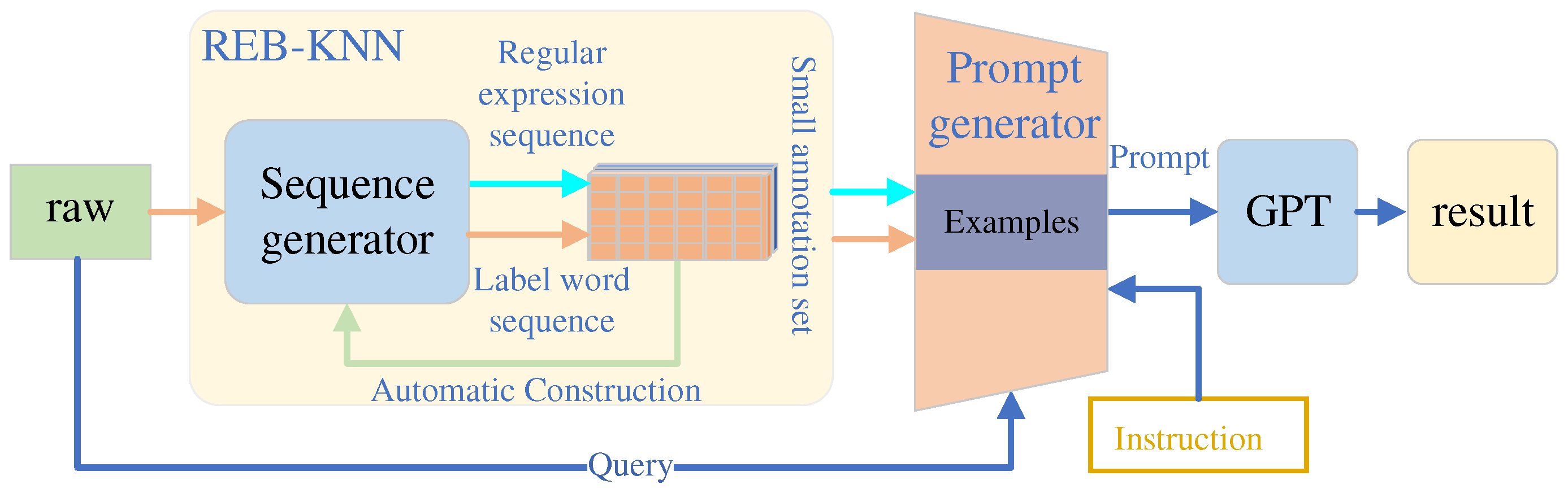

In this section, we present the methodology employed in our study to address the task of Chinese address parsing using the In-Context Learning (ICL) approach. Our method, named CapICL, aims to achieve accurate recognition of Chinese address components at various granularities, even under low-resource conditions. CapICL combines the power of the Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3(GPT-3) model with a sequence generator and the REB-KNN algorithm to enhance the precision and specificity of address parsing. We will provide a detailed explanation of each component and its role in the subsequent subsections.

The CapICL architecture, depicted in

Figure 2, comprises a sequence generator, the REB-KNN algorithm, and the GPT model for address parsing. The sequence generator is constructed using a small annotated dataset, capturing distribution patterns and boundary features of address types to model address structure and semantics, mitigating interference from unnecessary variations. It generates regular expression and label word sequences, providing a structured representation of the address components. The REB-KNN algorithm leverages regular expression matching and BERT-based semantic similarity computation to retrieve similar annotated samples. These selected samples are used to generate prompts, which are then inputted into the GPT model for address parsing.

3.1. Sequence Generator

The Sequence Generator is a crucial component of our CapICL model, responsible for producing structured representations of address components from the raw text. It captures the distribution patterns and boundary features of different address types, enabling the modeling of address structure and semantics while minimizing interference from unnecessary variations. By combining a set of regular expressions, a directed acyclic graph, and a binary classifier, the Sequence Generator automatically generates regular expression and label word sequences. Through training on a small annotated dataset, it learns the inherent characteristics and dependencies of address components, allowing for the transformation of the raw text into structured sequences.

Additionally, the sequence generator serves as a core component of the REB-KNN algorithm. Experimental results in

Section 4.4 demonstrate that directly computing the semantic similarity of raw text leads to lower quality prompts. To address this, our approach proposes using the sequence generator to select samples.

Moreover, the generation process involves producing two types of sequences: regular expression sequences and label word sequences. Previous studies by Ling et al. have highlighted the distinct boundary features and type distribution patterns of Chinese addresses, providing valuable insights for constructing a sequence generator based on a small annotated dataset [

24,

25].

3.1.1. Set of Regular Expressions

The Set of Regular Expressions (SORES) is a crucial component within the CapICL model for accurately identifying multiple fine-grained address components in complex addresses. As shown in Table 3, the address “石南路与翠竹街公园道一号2期*号楼**楼东*户” (Intersection of Shinan Road and Cuizhu Street, Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1, Unit *, East of the *th floor in Building *) contains three address components: “石南路与翠竹街”(Intersection of Shinan Road and Cuizhu Street) of type LOC(location information), “公园道一号2期” (Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1) of type COM(community or unit information), and “*号楼**楼东*户” (Unit *, East of the *th floor in Building *) of type INF(detailed information such as floor and room numbers). To protect user privacy, “*” is used to represent Arabic numerals.

Leveraging the expressive power of regular expressions in representing address components [

25], we create a regular expression set (RES) for each type of toponym, as illustrated in

Table 1. These RES collectively form the Set of Regular Expression Sets (SORES), encompassing all types of address components.

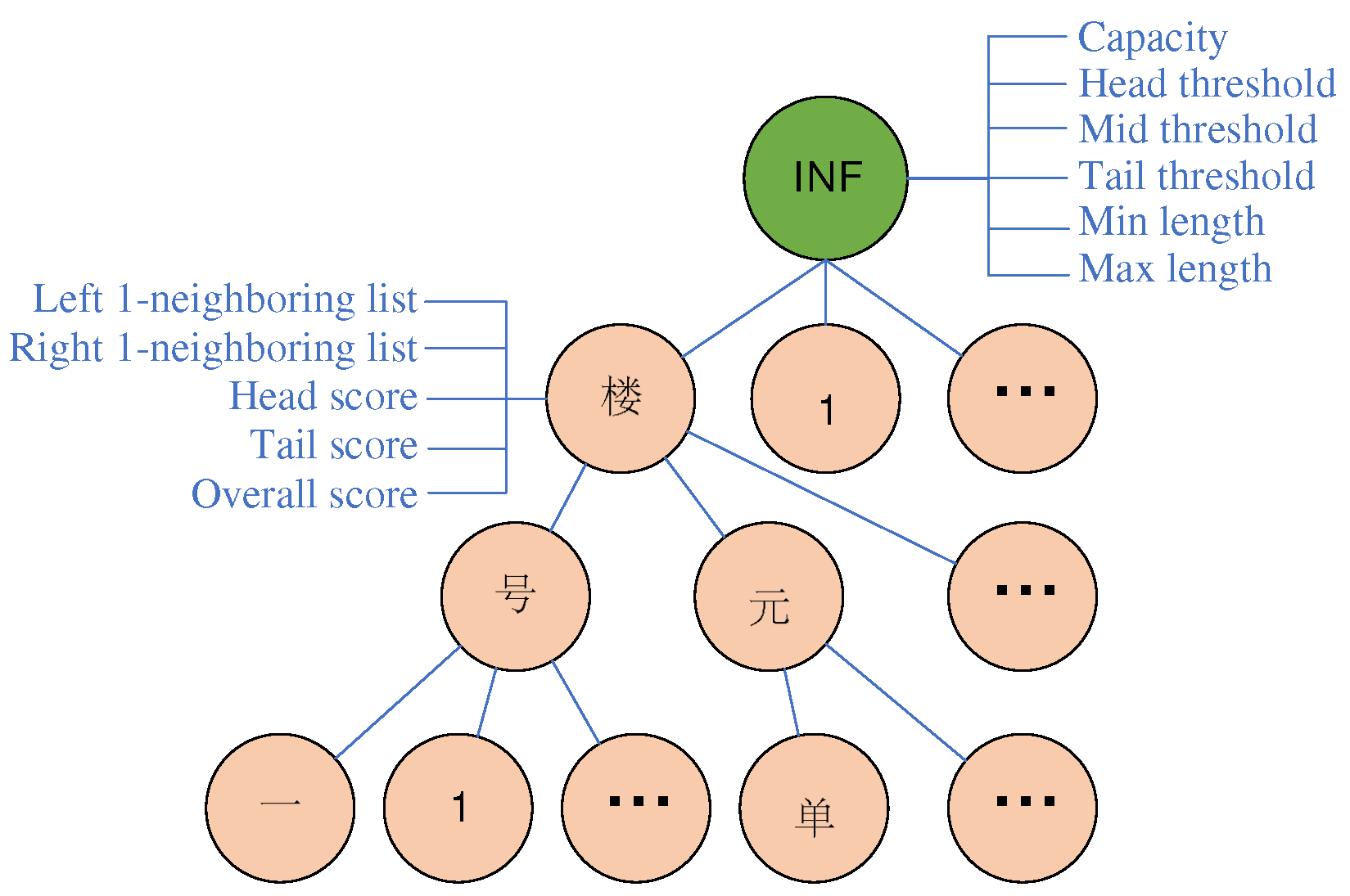

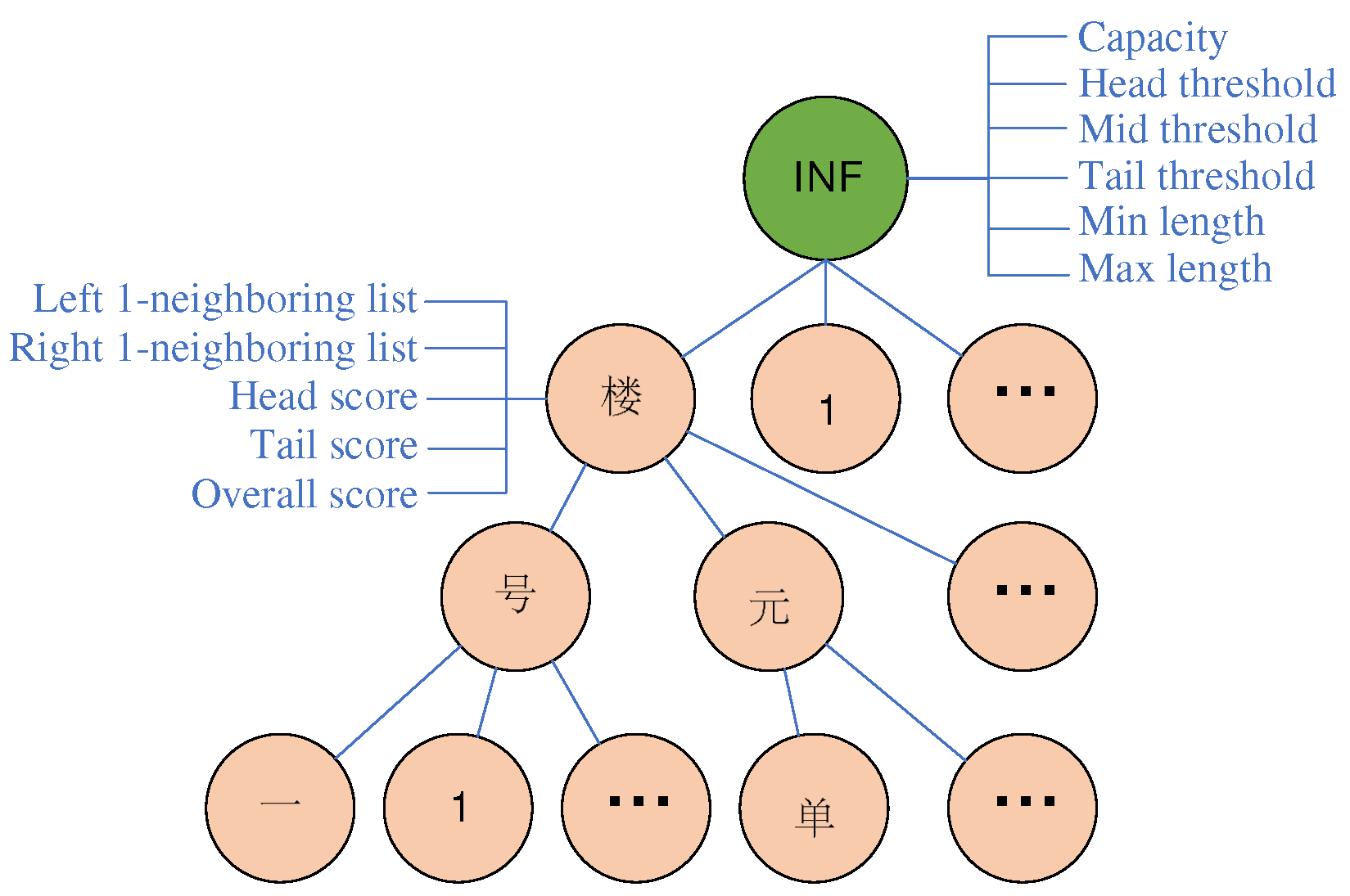

The scores (

) calculation and regular expression solving in

Table 1 are based on a trie, which is an efficient data structure for string retrieval and insertion. To leverage the distinctive characteristics of address components, we construct a trie by reversing the address segmentation. The trie’s structure is depicted in

Figure 3.

Specifically, the capacity serves as a crucial criterion for pruning, as it not only aids in capturing the significant boundary features of address components within the trie but also effectively controls the size of the set of regular expression sets (SORES).

Scoring Calculation. Introducing

S to represent the tokenized sequence of an address component

T, the score (

) of the regular expression generated by

T is calculated using equations

1 and

2:

Here,

O represents the overall score in the trie structure shown in

Figure 3. If

is not present in the trie,

, where

is a small value such as 0.001.

H and

T represent the head and tail scores in the trie, respectively.

denotes the number of tokens in the tokenized sequence, and

represents the number of characters in the

i-th token. The value of

is set to 0.3 to balance the contribution of the overall score in the

calculation.

Equations

1 and

2 accurately evaluate the priority of regular expressions in the regular expression set. Therefore, by performing matching in descending order, the best match can be achieved.

Solving Regular Expressions. If during the search process of

in the trie, it branches at the

N-th level (with the root node being the 0-th level) where the number of subtrees exceeds 1, we introduce

to represent the number of subtrees. For example, if

is “1号楼” (“Building 1” in English), in

Figure 3,

branches at the 2nd level (corresponding to the node “号”) where the node “号” has multiple subtrees. Assuming there are 3 subtrees, we have

. Specifically, if

does not exist in the trie, it is denoted as

. Equation

3 provides the method for solving the regular expression of

.

Here,

represents the maximum length of the current address component type,

concatenates all nodes at the

-th level using the symbol “|”, and

represents the last

N strings of

. The symbol

represents a threshold for the number of nodes in the current subtree when constructing regular expressions. If the number of nodes exceeds this threshold, the regular expression is constructed using the wildcard “.”; otherwise, the pattern “(x|y)” is used. In this paper, the value of

is dynamically determined based on the overall information of the trie.

By using Equation

3, the regular expressions for all label word sequences in

S can be determined. These regular expressions are then merged sequentially to obtain the regular expressions shown in

Table 1. Thus, by using the labeled set, SORES can be automatically generated.

From

Table 1, it can be observed that given the input text

and the address component type

, it is easy to obtain the corresponding address component associated with

through regular expression matching. Additionally, the corresponding score

can be obtained. Therefore, SORES provides support for matching all types of named entities and evaluating the matching performance.

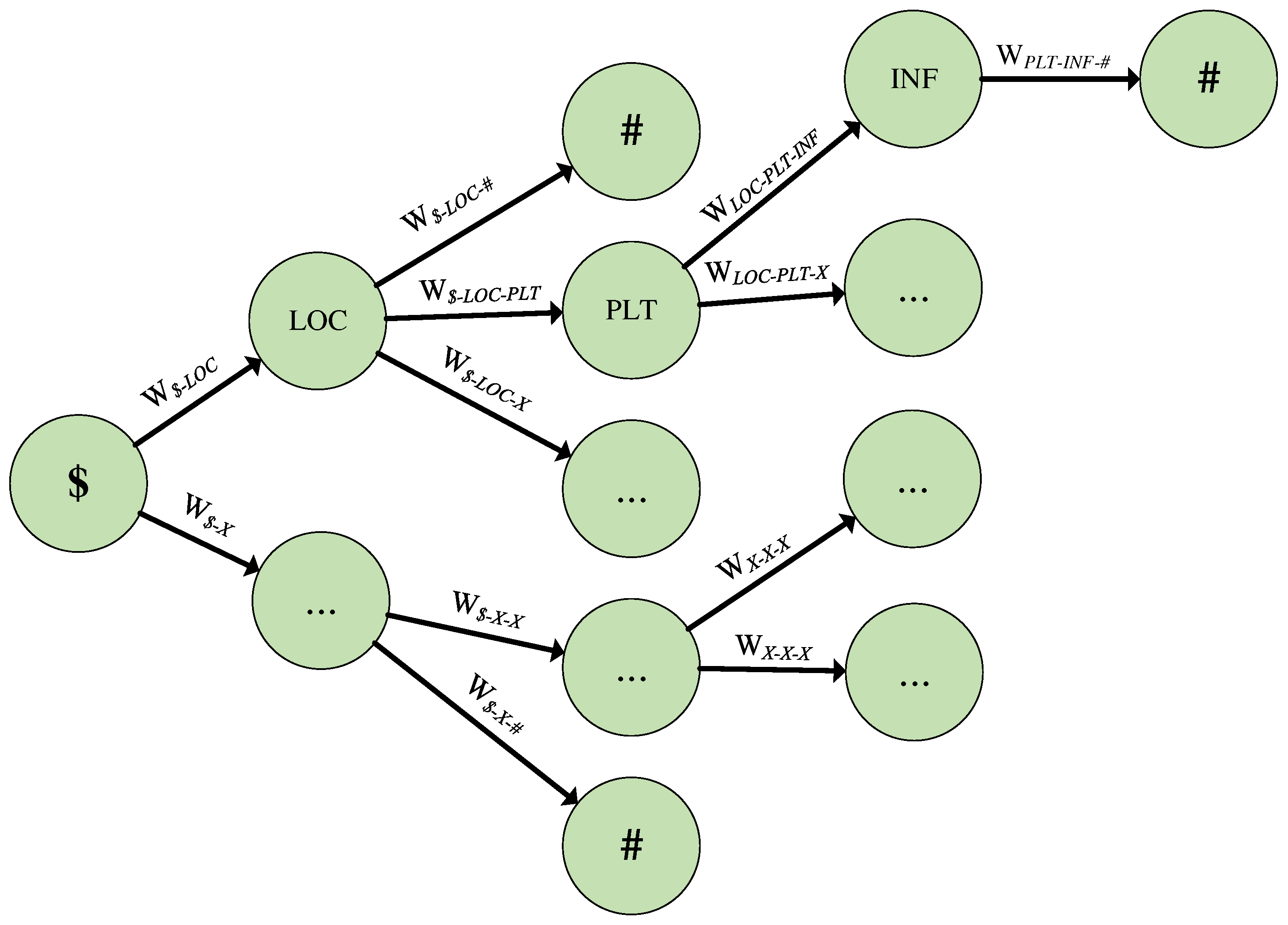

3.1.2. Directed Acyclic Graph

The process of segmenting named entities at arbitrary granularity using SORES involves an iterative process of matching the beginning of . Given a specific , the corresponding RES can be determined, and then the regular expressions in RES are sequentially matched against . The first successful match yields the corresponding address component. The process is repeated by removing that address component from until the segmentation is complete or no further segmentation is possible. Thus, determining the current is a key issue, and this section will discuss specific solutions.

The introduction of a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) is motivated by the need to represent and analyze the sequence of Chinese address component types in a structured manner [

26,

27]. The DAG, as shown in

Figure 4, captures the relationships and transition probabilities between different address component types. Each node in the graph represents a specific address component type, while the edges represent the likelihood of transitioning from one type to another. This approach leverages the significant distribution patterns observed in Chinese named entities [

24], allowing the construction of the directed graph using statistical methods [

28].

Using the directed graph in

Figure 4, we can determine the next address component type and its transition probability based on the previous type and the current type. However, it is important to note that the determination of the exact address component type may not always be unique, as indicated by the structure of the graph. Additionally, the transition probabilities are statistical measures of likelihood. Therefore, the use of the DAG provides a probabilistic framework for making decisions during the segmentation process, offering a single choice at each step. To address the challenge of ambiguity, the following discussion will explore the use of a binary classifier to evaluate and refine the current segmentation scheme.

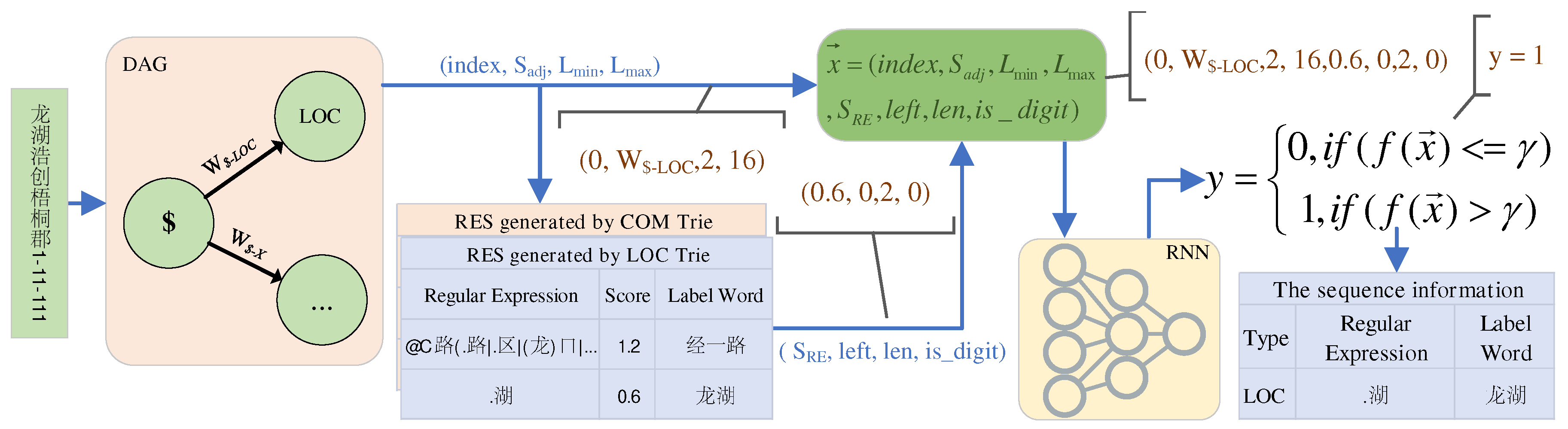

3.1.3. Binary Classifier

In the context of this study, the Binary Classifier refers to a recurrent neural network (RNN)-based model that plays a crucial role in evaluating the effectiveness of the current address component segmentation. It serves as a tool to assess the segmentation quality and make informed decisions during the iterative process of address component segmentation.

Through the DAG, we can choose the corresponding address component type (

) based on the current state. Although it cannot be uniquely determined, SORES can provide a series of information. This information can be used to evaluate the segmentation effect more accurately. To achieve this, we use a regression model implemented with a recurrent neural network (RNN) and introduce a threshold

to create a binary classifier. We use binary cross-entropy as the loss function to train the model, minimizing the difference between the predicted labels and the true labels. The computation formula for binary cross-entropy is given by Equation

4:

where

By providing input vectors and their corresponding output labels, the RNN model can be trained to learn the mapping relationship between the input sequences and the corresponding binary classification labels. In this way, we can evaluate the current segmentation effect based on the input vector. The next section will describe the training process in detail, and Algorithm 1 provides the relevant details.

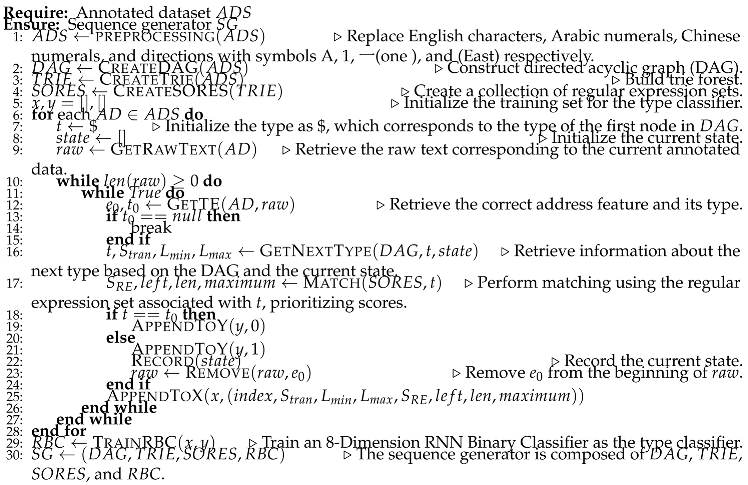

3.1.4. Automatic Construction of Sequence Generator

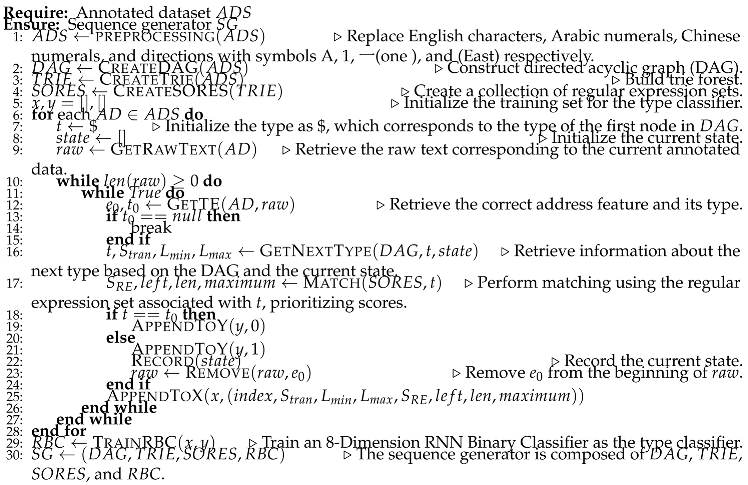

In conclusion, this section presents an algorithm for automatically constructing a sequence generator using a small annotated dataset, as shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: Automatic Construction of Sequence Generator |

|

The Algorithm 1 provides a specific implementation of automatically constructing a sequence generator using a small annotated dataset. It includes the step-by-step process of building the directed acyclic graph (DAG), trie, SORES, and binary classifier. Detailed instructions for implementing the binary classifier are provided. Next, we will explore the utilization of the sequence generator to generate regular expressions and label word sequences for the raw text.

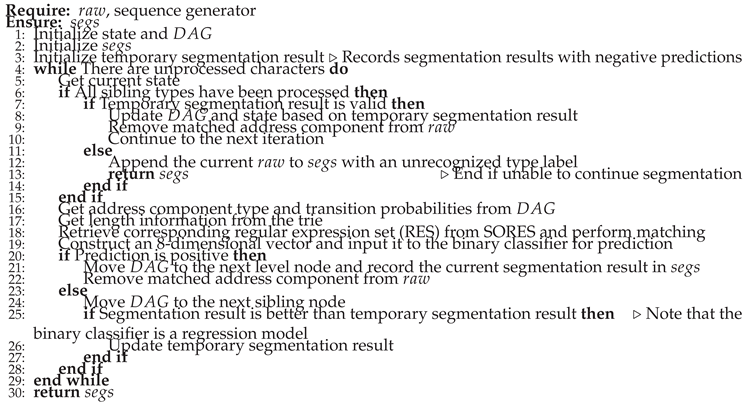

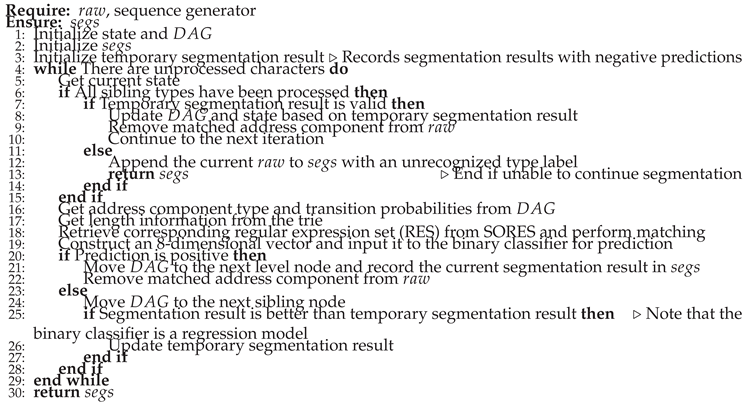

3.2. Sequence Generation

Sequence generation plays a crucial role in our approach. By leveraging a sequence generator, we can obtain structured representations that capture the inherent patterns and semantic information in the data. This step is crucial for enhancing the accuracy and effectiveness of the CapICL model. In this section, we delve into the details of the sequence generation process.

The sequence generator can be used to generate regular expression sequences and label word sequences for the raw text. Although these two sequences have different forms, both are results of arbitrary granularity segmentation of the raw text based on the types of geographical entities.

Figure 5 illustrates the specific process.

The above explanation provides a detailed description of a single segmentation process. Let

represent the segmentation result. The complete segmentation process is shown in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2: Segmentation Algorithm |

|

The segmentation result

is shown in

Table 2, which provides the arbitrary granularity segmentation result for the raw text. The symbols in the table have the same meanings as in

Table 1.

From

Table 2, the regular expression sequence and label word sequence can be obtained.

Generating the regular expression sequence. The regular expression sequence can be obtained by concatenating the regular expressions in

shown in

Table 2 using “.*?”.

Generating the label word sequence. In contrast to the regular expression sequence, we not only use the label words from , but also incorporate the type information. Specifically, we first concatenate each label word with its corresponding type information, and then concatenate them using spaces to form the label word sequence.

In this section, we have discussed the process of sequence generation in detail, which enables us to obtain two types of sequences corresponding to the original text. Sequence generation serves as a crucial step in constructing the prompt, laying a solid foundation for subsequent steps. Moving forward, we will explore how to utilize the REB-KNN algorithm to construct the prompt required for CapICL based on the generated sequences.

3.3. Prompt Generation

Building upon the two sequences generated in the previous section, we now delve into the process of prompt generation. In contextual learning, a well-crafted prompt plays a critical role [

15,

29], guiding the model in understanding and generating contextually relevant content. By designing prompts with careful consideration, we can effectively support the model’s context learning for specific tasks, enabling it to produce accurate and consistent outputs [

23]. Therefore, prompt generation serves as a crucial component of our model, influencing the subsequent steps’ accuracy and efficacy. In this section, we delve into the utilization of the REB-KNN algorithm for selecting samples that are similar to the raw text. Subsequently, as depicted in

Figure 2, we seamlessly integrate these selected samples, along with the instructional information and the query(raw), into the prompt template, resulting in the construction of high-quality prompts required for ICL.

3.3.1. KNN Demonstration Examples

When selecting similar samples, it is important to ensure the quality of the training set and the accuracy of the similarity measurement method. By appropriately selecting demonstration examples that are most similar to the input sample, we can provide effective references and guidance to the model, helping it generate content that is relevant to the task.

Regular Expression Matching. Use the generated regular expression sequence to match the labeled samples and select M similar samples to the raw text, where M is no more than K/2.

BERT Semantic Similarity Calculation. Although regular expressions are effective in matching desired samples, the regular expression method itself requires the data distribution to meet specific criteria. In order to enhance the precision and robustness of our model, we employ the BERT semantic similarity calculation method to select the remaining K-M samples. Specifically, when computing the semantic similarity between the raw input sample and each example in the small annotation set, we utilize the label word sequence instead of the original text. This approach involves leveraging BERT-based models, such as SentenceBERT [

30,

31], to evaluate the semantic similarity between the raw text and the corresponding label word sequence from the small annotation set. Subsequently, we choose the K-M samples with the highest similarity, as depicted in

Figure 2.

By incorporating the BERT semantic similarity calculation method alongside regular expressions, we improve the accuracy and robustness of our model’s sample selection process. This selection process plays a crucial role in guiding the model during context learning and content generation, leading to enhanced performance on specific tasks.

3.3.2. Prompt Template

The Prompt Template plays a pivotal role in CapICL by providing descriptive information about the task and the samples. It serves as a guiding framework for the model, facilitating the generation of accurate and contextually relevant content. The thoughtful design and effective utilization of the Prompt Template have been shown to significantly enhance the model’s performance and the quality of the generated results [

15,

29].

The Prompt Template consists of the following three components: Instruction, Examples, and Query. Additionally,

Figure 2 provides a clear illustration of the overall structure of the Prompt Template, visually representing its components and their relationship.

The Instruction component contains descriptive text that provides information about the samples. For instance, in the case of the Logistic dataset, the instruction can be formulated as follows: "The following information is derived from Chinese logistic addresses. The labels and their meanings are as follows: LOC denotes location information; COM represents community or unit information; INF indicates detailed information such as floor and room numbers, and so on."

The Examples component consists of a set of demonstration samples constructed in the previous section.

The Query component represents the raw text, which corresponds to the input sample requiring prediction.

By populating the instruction, Examples, and Query within the Prompt Template, you can generate the Prompt that aligns with the raw text. This Prompt is then provided as input to the GPT-3 model for prediction.

3.4. Model Prediction

In this work, we employ the In-Context Learning (ICL) method to parse Chinese addresses using a small amount of annotated data without the need for additional training. To achieve this, we pass the constructed prompt to the GPT-3 model for prediction, leveraging its powerful language generation capabilities to obtain predicted outputs that include the parsing results of address components [

14,

32,

33,

34].

However, it is worth noting that there may be slight differences between the format of the constructed samples and the final parsing results, as depicted in

Figure 2. This is because while the constructed samples utilize manually annotated address information as input, the generated content in the model’s predicted outputs may exhibit slight variations. Therefore, after obtaining the predicted outputs from the model, a simple post-processing and parsing step is performed to extract the final address parsing results.

Through these steps, we can effectively parse Chinese addresses and obtain accurate results, providing a crucial foundation for automated address processing and information extraction. In the following experimental section, we will further demonstrate the performance and effectiveness of our method and compare it with other approaches.

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

The core focus of this paper is fine-grained Chinese address parsing with custom label types in low-resource scenarios. Therefore, we selected two representative Chinese address component datasets: ChineseAddress [

5] and Logistic [

24,

25].

Table 3 describes the basic information of these two datasets.

In

Table 3, the LOC category in the Logistic dataset represents location information, COM represents community or unit information, and INF represents detailed information such as floor and room numbers. Compared to the Address dataset, the Logistic dataset has a wider range of labeled types and more flexible definitions. These two datasets can better capture the characteristics of different application scenarios in terms of address component types, providing solid data support for the experiments conducted in this paper.

Since this paper focuses on low-resource scenarios[

10], a random sampling approach is used to obtain labeled subsets from the training set. Similarly, the validation set and test set are compressed using random sampling. However, to ensure effectiveness, this paper utilizes a trained model to select the dataset from 10 randomly sampled test sets that is closest to the original test set, which serves as the final test set. For experimental convenience, the test set sizes for both datasets are set to 300, denoted as

and

respectively.

4.2. Main Experimental Results

In this section, we constructed a low-resource scenario by randomly sampling the training set from

Table 3. The specific results of the experiment are presented in

Table 4.

From

Table 4, it can be observed that in the low-resource scenario, The CapICL method achieves the best performance on both datasets, demonstrating higher precision and recall rates compared to other methods (except for recall rate on the Logistic dataset). Although this low-resource scenario was constructed through random sampling, the experiments in

Section 4.5 indicate the effectiveness of The CapICL method.

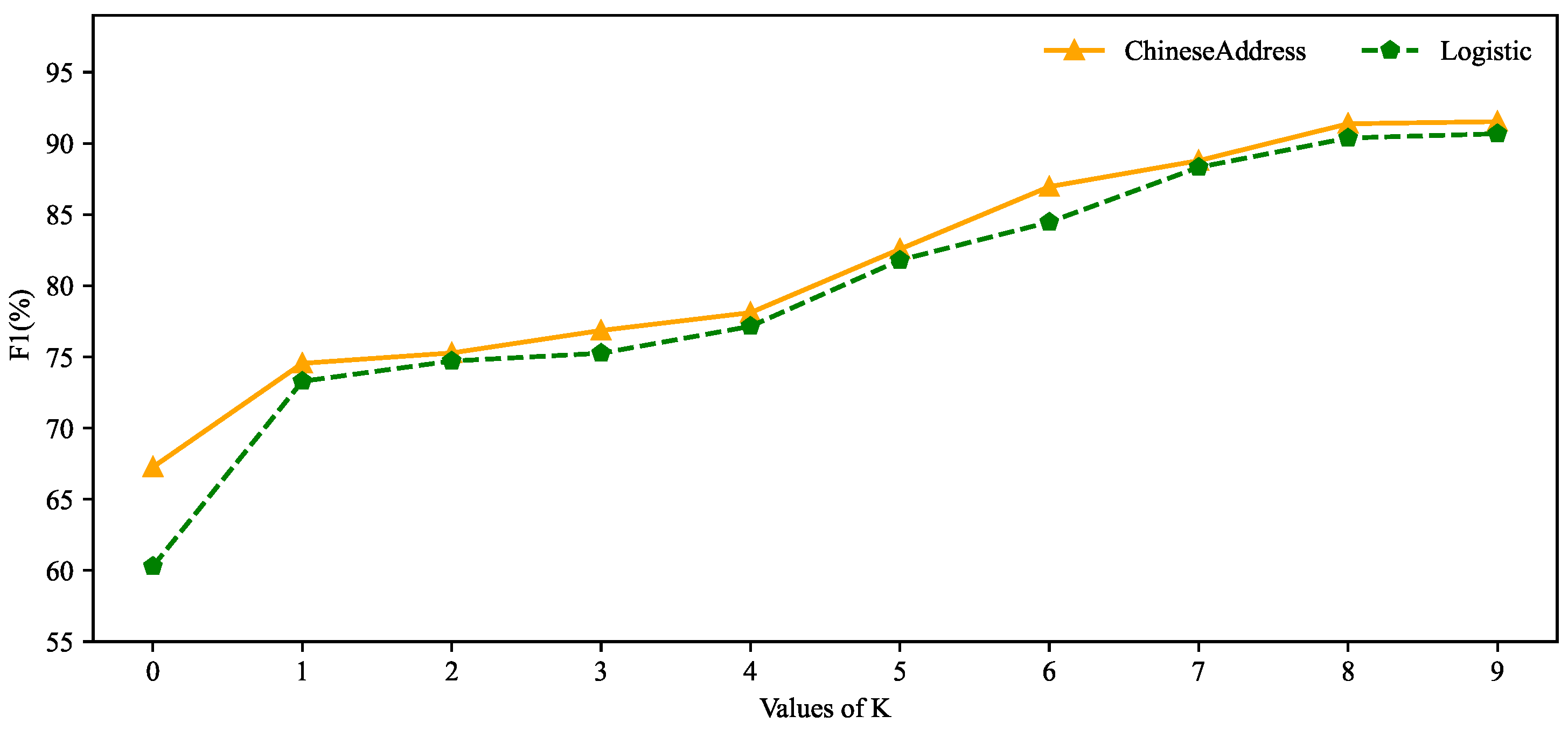

4.3. Impact of K on the Model

In practice,CapICL utilizes KNN for sample selection and contextual learning, where the value of K determines the number of samples. Therefore, the influence of K on the model should be significant. To investigate this in detail, this section conducts experiments to study the degree of impact of K on the model, and the results are shown in

Figure 6.

In

Figure 6, when K is set to 0, representing zero-shot recognition, the F1 score is only around 60%. However, when K is set to 1, representing one-shot recognition, the increase in F1 score is most significant, reaching close to 75% on both datasets. As K increases, the F1 score gradually improves. However, after reaching K=8, the improvement becomes less pronounced.

4.4. Ablation Study

In this section, an ablation study is conducted to validate the effectiveness of our proposed method. First, the regular expression matching module and BERT semantic similarity calculation module are removed by randomly selecting samples. Then, samples are selected only through regular expression matching to remove the BERT semantic similarity calculation module. Lastly, samples are selected only based on the semantic similarity of the raw text and the label word sequence to remove the regular expression matching module.

Table 5 presents the results of the ablation study, with the results being shown as the increment/decrement relative to the baseline (REB-KNN) in the first row. This demonstrates the role of different modules in the overall model.

By comparing the results in the ablation study table, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The effectiveness of REB-KNN in improving model performance is validated. When random sample selection is used, the F1 score decreases by nearly 30% on the Logistic dataset and nearly 20% on the ChineseAddress dataset.

The BERT semantic similarity selection module plays a crucial role in REB-KNN, especially the method based on the label word sequence. On the ChineseAddress dataset, FSB-KNN only exhibits a decrease of approximately 2

Although regular expression matching can improve the F1 score, its effect is limited as it may not yield valid matches in many cases. Relatively speaking, its impact is more significant on the Logistic dataset, where more samples can be matched.

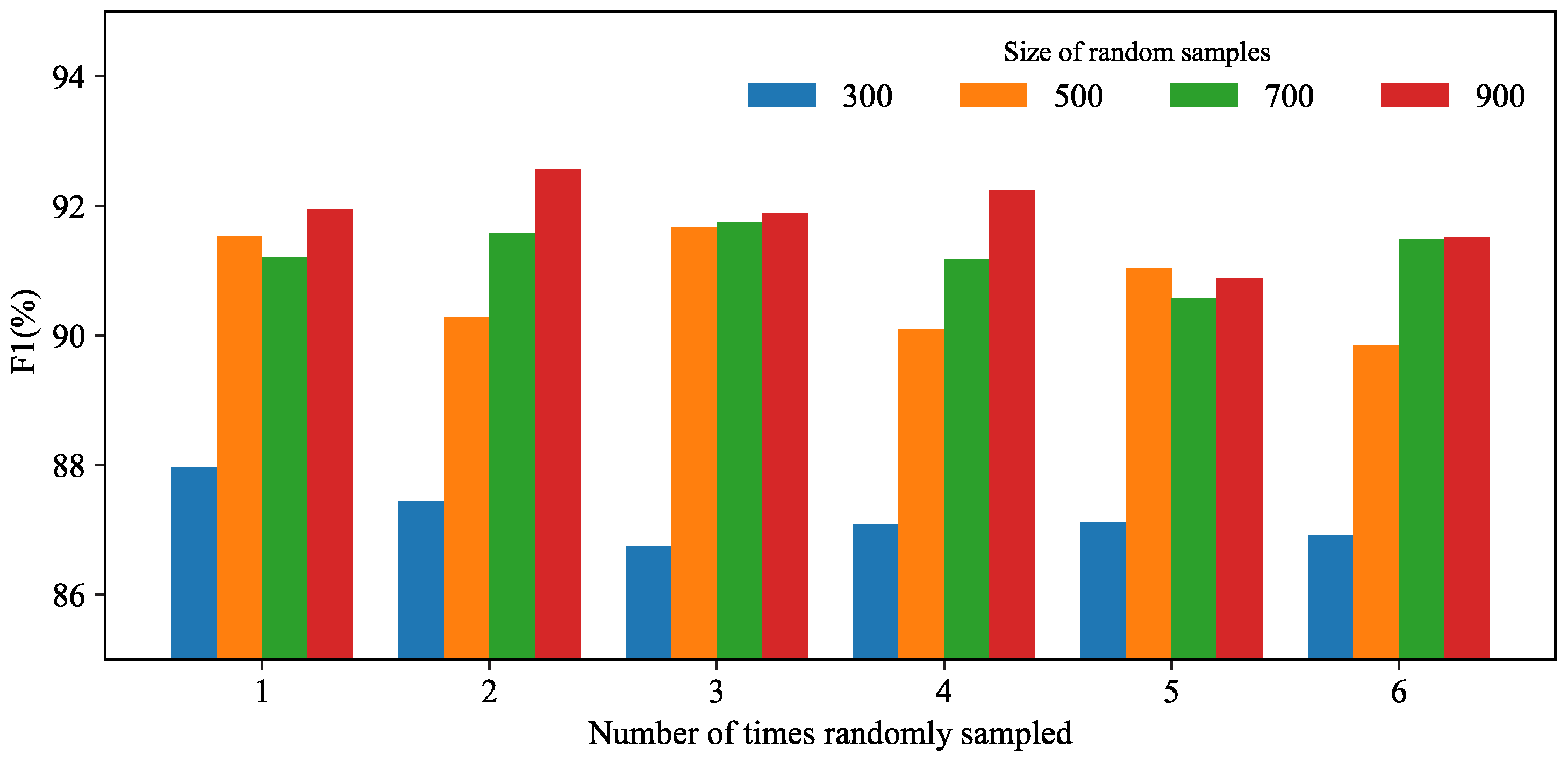

4.5. Stability Analysis

The previous experiments were based on the annotated dataset mentioned in

Table 4, which was obtained through random sampling. In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this section takes the ChineseAddress dataset as an example and randomly selects four different-sized random samples as annotated datasets. The value of K is set to 9 according to the experimental results in

Section 4.3.

Figure 7 shows the results of six repeated experiments.

From the graph, it can be observed that for annotated datasets of the same size, the performance difference of the model does not exceed 2%. Moreover, as the dataset size increases, the model performance also improves. The performance improvement is particularly evident from 300 to 500, while the improvement from 700 to 900 is not significant, indicating that the model’s performance stabilizes at this point. Therefore, it can be concluded that the proposed method exhibits good stability.

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the findings and implications of our proposed approach for Chinese address parsing in low-resource scenarios.

5.1. CapICL Effectiveness and K-Value Impact

The experimental results in

Table 4 support the superior performance of CapICL compared to other methods, demonstrating higher accuracy and recall rates (except for Logistic recall). These findings emphasize the effectiveness of our approach in low-resource scenarios. Furthermore, the experiments conducted in

Section 4.4 provide additional evidence of the effectiveness of CapICL.

Additionally,

Figure 6 reveals the significant impact of the K-value selection on the model’s performance. Notably, varying the K-value results in varying levels of performance improvement. Particularly, as the K-value increases, there is a noticeable enhancement in the model’s performance. This observation highlights the importance of selecting an appropriate K-value to optimize the results of CapICL.

Moreover, in the Stability Analysis experiment, it was observed that the instruction has a significant effect when K is 0, but its influence diminishes as K increases. This further highlights the importance of the REB-KNN algorithm.

Together, these results demonstrate the effectiveness of CapICL in achieving high-performance address parsing, while emphasizing the influence of K-value selection and the importance of the REB-KNN algorithm for optimal performance.

5.2. Role of REB-KNN Algorithm

The REB-KNN algorithm plays a pivotal role in our approach by utilizing a sequence generator to generate sequences of regular expressions and label word sequences. In particular, the generation of label word sequences greatly enhances the efficacy of sample selection compared to the raw text, especially when leveraging BERT semantic similarity for KNN-based sample selection. This further enhances the model’s performance.

In the experiments, we conducted a comparison between the REB-KNN algorithm and a baseline method that randomly selects samples. The results demonstrate that the baseline method experiences a significant decrease of approximately 30% in F1 score on the Logistic dataset and nearly 20% on the Address dataset. This confirms the substantial performance improvement achieved by the REB-KNN algorithm.

Furthermore, ablation experiments were performed to evaluate the contributions of different components in the REB-KNN algorithm. On the Address dataset, the FSB-KNN method exhibits only a slight decrease of approximately 2% compared to the baseline method. However, the RawB-KNN method shows a notable decrease of around 16%. This highlights the crucial role of the BERT similarity selection module, particularly in the generation of label word sequences. Although the differences on the Logistic dataset are less pronounced, the label word sequences still play a significant role.

Additionally, the ablation experiments on RE-KNN demonstrate the positive impact of regular expression sequences. While their effect is not as prominent as that of the label word sequences, they provide beneficial complementary information for sample selection. It is important to emphasize the role of regular expressions as one of the core components in the sequence generator during the generation of label word sequences.

In conclusion, the REB-KNN algorithm successfully tackles the challenges in low-resource scenarios and substantially improves the performance of the Chinese address parsing model. The integration of label word sequences and regular expression sequences in the REB-KNN algorithm plays a critical role and contributes to the success of our proposed CapICL method in low-resource Chinese address parsing tasks.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although our approach shows promising results, there are some limitations to be addressed. The effectiveness of regular expression matching is limited, as it often fails to capture all relevant samples. However, it has a relatively larger impact on the Logistic dataset. Future work could explore more advanced techniques to improve the performance in this regard.

Overall, our proposed approach demonstrates effectiveness in addressing the challenges of Chinese address parsing in low-resource scenarios. The findings and insights gained from our experiments shed light on the importance of the REB-KNN algorithm, the impact of K-value selection, and the integration of instruction and Examples in achieving high-performance address parsing. Future research can further explore enhancements to address the limitations and refine the approach for even better performance.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this study, we proposed a low-resource Chinese address parsing method based on the CapICL model. Our approach leverages the REB-KNN algorithm for sample selection and generation of label word sequences, resulting in substantial performance improvements. The experimental results demonstrated a significant increase in F1 score, with approximately 30% improvement on the Logistic dataset and approximately 20% improvement on the Address dataset compared to the ICL method that uses random sample selection. Ablation experiments confirmed the critical role of the BERT semantic similarity calculation and regular expression matching in the REB-KNN algorithm.

Our method effectively addresses the challenges of low-resource Chinese address parsing and achieves remarkable performance gains. The integration of the REB-KNN algorithm and the generation of label word sequences play a pivotal role in enhancing the model’s performance.

Future work should focus on further improving the sample selection and sequence generation methods. Additionally, exploring data augmentation techniques for improved generalization, optimizing the label word sequence generation for enhanced accuracy and efficiency, and investigating cross-domain and cross-lingual transfer learning approaches can contribute to the adaptability and robustness of our method. Furthermore, applying our approach to other tasks and domains, such as named entity recognition and relation extraction, would validate its generality and effectiveness.

Continued research in the field of low-resource Chinese address parsing is encouraged, as there are numerous unexplored directions and challenges. By addressing these challenges, we can expect further advancements in the field and improved results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Guangming Ling and Xiaofeng Mu; methodology, Aiping Xu; software, Guangming Ling and Xiaofeng Mu; validation, Guangming Ling and Chao Wang; resources, Guangming Ling and Chao Wang; data curation, Guangming Ling; writing—original draft preparation, Guangming Ling; writing—review and editing, Aiping Xu and Xiaofeng Mu; funding acquisition, Chao Wang.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFB2100603), the Key R&D Program of Hubei Province (No. 2022BAA048), the National Natural Science Foundation of China program (No. 41890822) and the Open Fund of National Engineering Research Centre for Geographic Information System, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China (No. 2022KFJJ07). The numerical calculations in this paper have been done on the super-computing system in the Supercomputing Centre of Wuhan University.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Joseph, K. NeuroTPR: A Neuro-net Toponym Recognition Model for Extracting Locations from Social Media Messages. Transactions in GIS 2020, 24, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Xie, Z.; Xu, D.; Ma, K.; Qiu, Q.; Pan, S.; Huang, B. Geographic Named Entity Recognition by Employing Natural Language Processing and an Improved BERT Model. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, K.; Yousaf, J. Context-Aware Automated Interpretation of Elaborate Natural Language Descriptions of Location through Learning from Empirical Data. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2018, 32, 1087–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berragan, C.; Singleton, A.; Calafiore, A.; Morley, J. Transformer Based Named Entity Recognition for Place Name Extraction from Unstructured Text. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2023, 37, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, W.; Xie, P.; Li, L. Neural Chinese Address Parsing. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 3421–3431. [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, M.; Pezanowski, S.; MacEachren, A.M.; Wallgrün, J.O. GeoTxt: A Scalable Geoparsing System for Unstructured Text Geolocation. Transactions in GIS. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hu, Y.; Resch, B.; Kersten, J. Geographic Information Extraction from Texts (GeoExT). Advances in Information Retrieval: 45th European Conference on Information Retrieval, ECIR 2023, Dublin, Ireland, April 2–6, 2023, Proceedings, Part III. Springer-Verlag, 2023, pp. 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Hongwei, Z.; Qingyun, D.U.; Zhangjian, C.; Chen, Z. A Chinese Address Parsing Method Using RoBERTa-BiLSTM-CRF. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2022, 47, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritta, M.; Pilehvar, M.T.; Collier, N. A Pragmatic Guide to Geoparsing Evaluation. Language Resources and Evaluation 2020, 54, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedderich, M.A.; Lange, L.; Adel, H.; Strötgen, J.; Klakow, D. A Survey on Recent Approaches for Natural Language Processing in Low-Resource Scenarios. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2545–2568. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; Schuh, P.; Shi, K.; Tsvyashchenko, S.; Maynez, J.; Rao, A.; Barnes, P.; Tay, Y.; Shazeer, N.; Prabhakaran, V.; Reif, E.; Du, N.; Hutchinson, B.; Pope, R.; Bradbury, J.; Austin, J.; Isard, M.; Gur-Ari, G.; Yin, P.; Duke, T.; Levskaya, A.; Ghemawat, S.; Dev, S.; Michalewski, H.; Garcia, X.; Misra, V.; Robinson, K.; Fedus, L.; Zhou, D.; Ippolito, D.; Luan, D.; Lim, H.; Zoph, B.; Spiridonov, A.; Sepassi, R.; Dohan, D.; Agrawal, S.; Omernick, M.; Dai, A.M.; Pillai, T.S.; Pellat, M.; Lewkowycz, A.; Moreira, E.; Child, R.; Polozov, O.; Lee, K.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Saeta, B.; Diaz, M.; Firat, O.; Catasta, M.; Wei, J.; Meier-Hellstern, K.; Eck, D.; Dean, J.; Petrov, S.; Fiedel, N. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways, 2022, [2204.02311]. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Kong, L. Self-Adaptive In-Context Learning: An Information Compression Perspective for In-Context Example Selection and Ordering, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2212.10375]. [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Lyu, X.; Holtzman, A.; Artetxe, M.; Lewis, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Rethinking the Role of Demonstrations: What makes In-context Learning Work? EMNLP, 2022.

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Agarwal, S.; Herbert-Voss, A.; Krueger, G.; Henighan, T.; Child, R.; Ramesh, A.; Ziegler, D.M.; Wu, J.; Winter, C.; Hesse, C.; Chen, M.; Sigler, E.; Litwin, M.; Gray, S.; Chess, B.; Clark, J.; Berner, C.; McCandlish, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I.; Amodei, D. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc., 2020, NIPS’20, pp. 1877–1901.

- Gao, T.; Fisch, A.; Chen, D. Making Pre-trained Language Models Better Few-shot Learners. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3816–3830. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L. Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition with Self-describing Networks. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 5711–5722. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhu, R.; Kuang, J.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; Gao, M.; Cao, X.; Wu, W. Meta-Learning Triplet Network with Adaptive Margins for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition, 2023.

- Zhou, B.; Zou, L.; Hu, Y.; Qiang, Y.; Goldberg, D. TopoBERT: Plug and Play Toponym Recognition Module Harnessing Fine-tuned BERT, 2023, [2301.13631]. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dolan, B.; Carin, L.; Chen, W. What Makes Good In-Context Examples for GPT-3? Proceedings of Deep Learning Inside Out (DeeLIO 2022): The 3rd Workshop on Knowledge Extraction and Integration for Deep Learning Architectures. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 100–114. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-Train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 195:1–195:35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Shao, Y.; Qian, H.; Huang, X.; Qiu, X. Black-Box Tuning for Language-Model-as-a-Service. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 20841–20855.

- Lu, Y.; Bartolo, M.; Moore, A.; Riedel, S.; Stenetorp, P. Fantastically Ordered Prompts and Where to Find Them: Overcoming Few-Shot Prompt Order Sensitivity. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 8086–8098. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wallace, E.; Feng, S.; Klein, D.; Singh, S. Calibrate Before Use: Improving Few-shot Performance of Language Models. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 12697–12706.

- LING, G.m.; XU, A.p.; WANG, W. Research of address information automatic annotation based on deep learning. ACTA ELECTONICA SINICA 2020, 48, 2081. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, G.; Xu, A.; Wang, C.; Wu, J. REBDT: A Regular Expression Boundary-Based Decision Tree Model for Chinese Logistics Address Segmentation. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 6856–6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, P.W.G.; Murray, E.J.; Arnold, K.F.; Berrie, L.; Fox, M.P.; Gadd, S.C.; Harrison, W.J.; Keeble, C.; Ranker, L.R.; Textor, J.; Tomova, G.D.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Ellison, G.T.H. Use of Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to Identify Confounders in Applied Health Research: Review and Recommendations. International Journal of Epidemiology 2021, 50, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Quan, X. Directed Acyclic Graph Network for Conversational Emotion Recognition. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1551–1560. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.D.; McCann, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Thomson, H.; Green, M.J.; Smith, D.J.; Lewsey, J.D. Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs (ESC-DAGs): A Novel and Systematic Method for Building Directed Acyclic Graphs. International Journal of Epidemiology 2020, 49, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. 2022.

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese BERT-Networks. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 3982–3992. [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Making Monolingual Sentence Embeddings Multilingual Using Knowledge Distillation. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 4512–4525. [CrossRef]

- Petroni, F.; Rocktäschel, T.; Riedel, S.; Lewis, P.; Bakhtin, A.; Wu, Y.; Miller, A. Language Models as Knowledge Bases? Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 2463–2473. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners 2019.

- Schick, T.; Schütze, H. It’s Not Just Size That Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot Learners. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2339–2352. [CrossRef]

- Tjong Kim Sang, E.F.; De Meulder, F. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition. Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Natural Language Learning at HLT-NAACL 2003 - Volume 4; Association for Computational Linguistics: USA, 2003; CONLL ′03, p. 142–147.

- Ma, K.; Tan, Y.; Xie, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, S. Chinese Toponym Recognition with Variant Neural Structures from Social Media Messages Based on BERT Methods. Journal of Geographical Systems 2022, 24, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W. Lexicon Enhanced Chinese Sequence Labeling Using BERT Adapter. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 5847–5858. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Model overview. The generator takes the raw text as input and generates a regular expression sequence and a label word sequence. Subsequently, the REB-KNN algorithm selects similar annotated sample based on this regular expression sequence and label word sequence. Then, the prompt generator constructs prompts corresponding to the selected sample. The generated prompts are fed into the Generative Pre-trained Transformer(GPT) model for prediction, and the address parsing result is extracted from the model’s output.

Figure 1.

Model overview. The generator takes the raw text as input and generates a regular expression sequence and a label word sequence. Subsequently, the REB-KNN algorithm selects similar annotated sample based on this regular expression sequence and label word sequence. Then, the prompt generator constructs prompts corresponding to the selected sample. The generated prompts are fed into the Generative Pre-trained Transformer(GPT) model for prediction, and the address parsing result is extracted from the model’s output.

Figure 2.

CapICL architecture. The sequence generator captures the distribution patterns and boundary features of address types in the raw text, generating regular expression and label word sequences. The REB-KNN algorithm performs regular expression matching and BERT-based semantic similarity computation on these two sequences, selecting annotated samples that are similar to the query (raw). The specific structure of the Prompt template is illustrated in the top right corner of the figure, while the instruction provides a brief description of the dataset.

Figure 2.

CapICL architecture. The sequence generator captures the distribution patterns and boundary features of address types in the raw text, generating regular expression and label word sequences. The REB-KNN algorithm performs regular expression matching and BERT-based semantic similarity computation on these two sequences, selecting annotated samples that are similar to the query (raw). The specific structure of the Prompt template is illustrated in the top right corner of the figure, while the instruction provides a brief description of the dataset.

Figure 3.

Trie data structure for representing INF (detailed information such as floor and room numbers) address components. The trie is constructed by reversing the address segmentation and captures the specific characteristics of the addressed entities. The root node provides overall information about the corresponding type, including the capacity (maximum number of sub-tree root nodes, e.g., “building”), the threshold (minimum score for selecting information when constructing regular expressions), and the maximum and minimum lengths defining the length range of entities for the current type. The sub-trees below the root node represent the segmented parts of the address, while all nodes follow the same structure, describing the features of the represented string (e.g., “building number”). Additionally, each node maintains a left/right 1-neighboring list, which contains the neighboring strings. The overall score represents the normalized frequency of the string occurrence in the dataset.

Figure 3.

Trie data structure for representing INF (detailed information such as floor and room numbers) address components. The trie is constructed by reversing the address segmentation and captures the specific characteristics of the addressed entities. The root node provides overall information about the corresponding type, including the capacity (maximum number of sub-tree root nodes, e.g., “building”), the threshold (minimum score for selecting information when constructing regular expressions), and the maximum and minimum lengths defining the length range of entities for the current type. The sub-trees below the root node represent the segmented parts of the address, while all nodes follow the same structure, describing the features of the represented string (e.g., “building number”). Additionally, each node maintains a left/right 1-neighboring list, which contains the neighboring strings. The overall score represents the normalized frequency of the string occurrence in the dataset.

Figure 4.

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representing Chinese address component types. Nodes represent types of address components, and edges indicate the transition probability between types. The weight W of an edge represents the likelihood of transitioning from the current node to the next. The subscript of W is formed by connecting types with “-”. If there is a previous node, it is included. The symbols $ and # represent the beginning and end of named entities, respectively.

Figure 4.

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representing Chinese address component types. Nodes represent types of address components, and edges indicate the transition probability between types. The weight W of an edge represents the likelihood of transitioning from the current node to the next. The subscript of W is formed by connecting types with “-”. If there is a previous node, it is included. The symbols $ and # represent the beginning and end of named entities, respectively.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the Arbitrary Granularity Segmentation Process for Raw Text. Firstly, the address component type and transition probabilities are obtained from the directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on the current state. At the same time, length information is retrieved from the trie. Next, the corresponding regular expression set (RES) is obtained from SORES and matched against the text. Then, an 8-dimensional vector is constructed by combining the type information, transition probabilities, length information, matched start and end positions, regular expression scores, match length, and numerical indicators. This vector is used as input to the binary classifier. By predicting the positive label, the validity of the segmentation is determined. Finally, the segmentation result is obtained.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the Arbitrary Granularity Segmentation Process for Raw Text. Firstly, the address component type and transition probabilities are obtained from the directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on the current state. At the same time, length information is retrieved from the trie. Next, the corresponding regular expression set (RES) is obtained from SORES and matched against the text. Then, an 8-dimensional vector is constructed by combining the type information, transition probabilities, length information, matched start and end positions, regular expression scores, match length, and numerical indicators. This vector is used as input to the binary classifier. By predicting the positive label, the validity of the segmentation is determined. Finally, the segmentation result is obtained.

Figure 6.

Impact of K on model performance. Other experimental settings remain the same as in

Table 4.

Figure 6.

Impact of K on model performance. Other experimental settings remain the same as in

Table 4.

Figure 7.

Comparison of model performance based on randomly sampled annotated datasets of different sizes. Each sample size is randomly sampled six times, and independent model evaluations are performed for each annotated dataset.

Figure 7.

Comparison of model performance based on randomly sampled annotated datasets of different sizes. Each sample size is randomly sampled six times, and independent model evaluations are performed for each annotated dataset.

Table 1.

Set of Regular Expressions. This table illustrates a set consisting of three regular expressions corresponding to the INF type of address components. The scores quantify the reliability of the regular expressions in describing address components belonging to the INF type. The regular expressions are arranged in descending order of their scores. It is important to note that we have uniformly processed Chinese numerals, English characters, Arabic numerals, and directions in the text, replacing them with “一” (one), “A”, “1” (one), and “东” (East), respectively. In SORES, they are simplified as “@C”, “@A”, “@$”, and “@#”, respectively.

Table 1.

Set of Regular Expressions. This table illustrates a set consisting of three regular expressions corresponding to the INF type of address components. The scores quantify the reliability of the regular expressions in describing address components belonging to the INF type. The regular expressions are arranged in descending order of their scores. It is important to note that we have uniformly processed Chinese numerals, English characters, Arabic numerals, and directions in the text, replacing them with “一” (one), “A”, “1” (one), and “东” (East), respectively. In SORES, they are simplified as “@C”, “@A”, “@$”, and “@#”, respectively.

| Regular Expression |

Score |

Label Word |

| @$号楼@$.(.-|@$|.楼|.区|(@$)@#|.户|.院)* |

3.84 |

1号楼1

(Room 1, Building 1) |

| @$-@$@#户(.-|@$|.楼|.区|(@$)@#|.户|.院)* |

3.81 |

1-1东户

(Unit 1, East Wing,

Building 1) |

| @$@C@$@C@$(.-|@$|.楼|.区|(@$)@#|.户|.院)* |

3.79 |

1一1一1

(Room 1, Unit 1,

Building 1) |

Table 2.

Arbitrary granularity segmentation result for the raw text. The label word represents the address components that best match the length rules corresponding to the regular expressions.

Table 2.

Arbitrary granularity segmentation result for the raw text. The label word represents the address components that best match the length rules corresponding to the regular expressions.

| Type |

Regular Expression |

Label Word |

| LOC |

.湖 |

龙湖

(dragon lake) |

| COM |

郡(.城|.期|(小|街|新)区|.园 |(尚)郡|.苑|.家)* |

民安东郡

(a community) |

| INF |

@$-@$-@$(.-|@$|.楼|.区|(@$)@-#|.户|.院)* |

1-1-1

(Room 1, Unit 1,

Building 1) |

Table 3.

Datasets. Both datasets are split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio. The Logistics dataset is from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFB2100603). To protect user privacy, Chinese characters are represented by “@” and numbers are represented by “*”.

Table 3.

Datasets. Both datasets are split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio. The Logistics dataset is from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFB2100603). To protect user privacy, Chinese characters are represented by “@” and numbers are represented by “*”.

| Name |

Training |

Validation |

Test |

Example |

Labels |

| Address1

|

8957 |

2985 |

2985 |

下城区上塘路9号浙江昆剧团8室(Room 8, Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe, No.9 Shangtang Rd, Xicheng District) |

country,prov,city,distri-

ct,devzone,town,com-

munity,road,subroad,

and 21 other types.[5] |

| Logistic |

1422 |

474 |

474 |

李@@~1*********8~~~石南路与翠竹街公园道一号2期*号楼**楼东*户(@@ Li~1*********8~~~Unit *, East of the *th floor in Building *, Phase 2 of Park Road No. 1, Intersection of Shinan Road and Cuizhu Street) |

LOC,COM,INF |

Table 4.

Results of Chinese address parsing in a low-resource scenario. For this experiment, 560 and 300 data samples were randomly extracted from the ChineseAddress and Logistic datasets, respectively, and used as both the annotated set and the training set for the first five methods.

and

were used as the test sets for all methods. The value of K for REB-KNN was set to 9. The evaluation metrics were assessed based on exact matching [

35], including Precision (P), Recall (R), and their harmonic mean F1 (F).

Table 4.

Results of Chinese address parsing in a low-resource scenario. For this experiment, 560 and 300 data samples were randomly extracted from the ChineseAddress and Logistic datasets, respectively, and used as both the annotated set and the training set for the first five methods.

and

were used as the test sets for all methods. The value of K for REB-KNN was set to 9. The evaluation metrics were assessed based on exact matching [

35], including Precision (P), Recall (R), and their harmonic mean F1 (F).

|

Dataset |

| Method |

ChineseAddress |

Logistic |

| |

P |

R |

F |

P |

R |

F |

| APLT [5] |

89.14 |

87.71 |

88.42 |

88.37 |

88.89 |

88.63 |

| BERT-Softmax |

86.58 |

85.83 |

86.20 |

87.96 |

88.37 |

88.17 |

| BERT-CRF |

86.02 |

85.87 |

85.94 |

88.04 |

90.10 |

89.06 |

| BERT-LSTM-CRF [36] |

86.13 |

86.01 |

86.07 |

88.50 |

87.41 |

87.95 |

| LEBERT-CRF [37] |

86.54 |

86.08 |

86.31 |

87.66 |

89.49 |

88.57 |

| CapICL |

93.39 |

89.74 |

91.53 |

91.90 |

89.49 |

90.68 |

Table 5.

Results of the ablation study. The first row represents the results of the REB-KNN-based CapICL, and the experimental settings and results of all other methods are the same as in

Table 4. The subsequent rows show the variation in results for different ablation scenarios, with the values being the increment/decrement relative to the baseline (first row), indicated by up/down arrows. Rand-KNN represents random sample selection, RE-KNN represents sample selection using regular expression matching only, RawB-KNN represents sample selection based on the semantic similarity of the raw text using BERT, and FSB-KNN represents sample selection based on the semantic similarity of the label word sequence using BERT.

Table 5.

Results of the ablation study. The first row represents the results of the REB-KNN-based CapICL, and the experimental settings and results of all other methods are the same as in

Table 4. The subsequent rows show the variation in results for different ablation scenarios, with the values being the increment/decrement relative to the baseline (first row), indicated by up/down arrows. Rand-KNN represents random sample selection, RE-KNN represents sample selection using regular expression matching only, RawB-KNN represents sample selection based on the semantic similarity of the raw text using BERT, and FSB-KNN represents sample selection based on the semantic similarity of the label word sequence using BERT.

|

Dataset |

| Ablation Method |

ChineseAddress |

Logistic |

| |

P |

R |

F |

P |

R |

F |

|

Baseline (REB-KNN) |

93.39 |

89.74 |

91.53 |

91.90 |

89.49 |

90.68 |

| Rand-KNN w/o RE |

17.39

|

21.88

|

19.83

|

19.17

|

32.35

|

26.68

|

| RE-KNN w/o B |

21.69

|

27.44

|

24.86

|

22.20

|

25.31

|

23.85

|

| RawB-KNN w/o RE |

13.77

|

19.25

|

16.75

|

14.04

|

19.96

|

17.22

|

| FSB-KNN w/o RE |

2.01

|

2.85

|

2.45

|

8.11

|

12.33

|

10.34

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).