Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Vibrational spectroscopic approaches in phytochrome research

2.1. IR spectroscopic techniques

2.2. Raman spectroscopic techniques

2.3. Spectra interpretation

3. Photoinduced reaction mechanism and chromophore structural changes

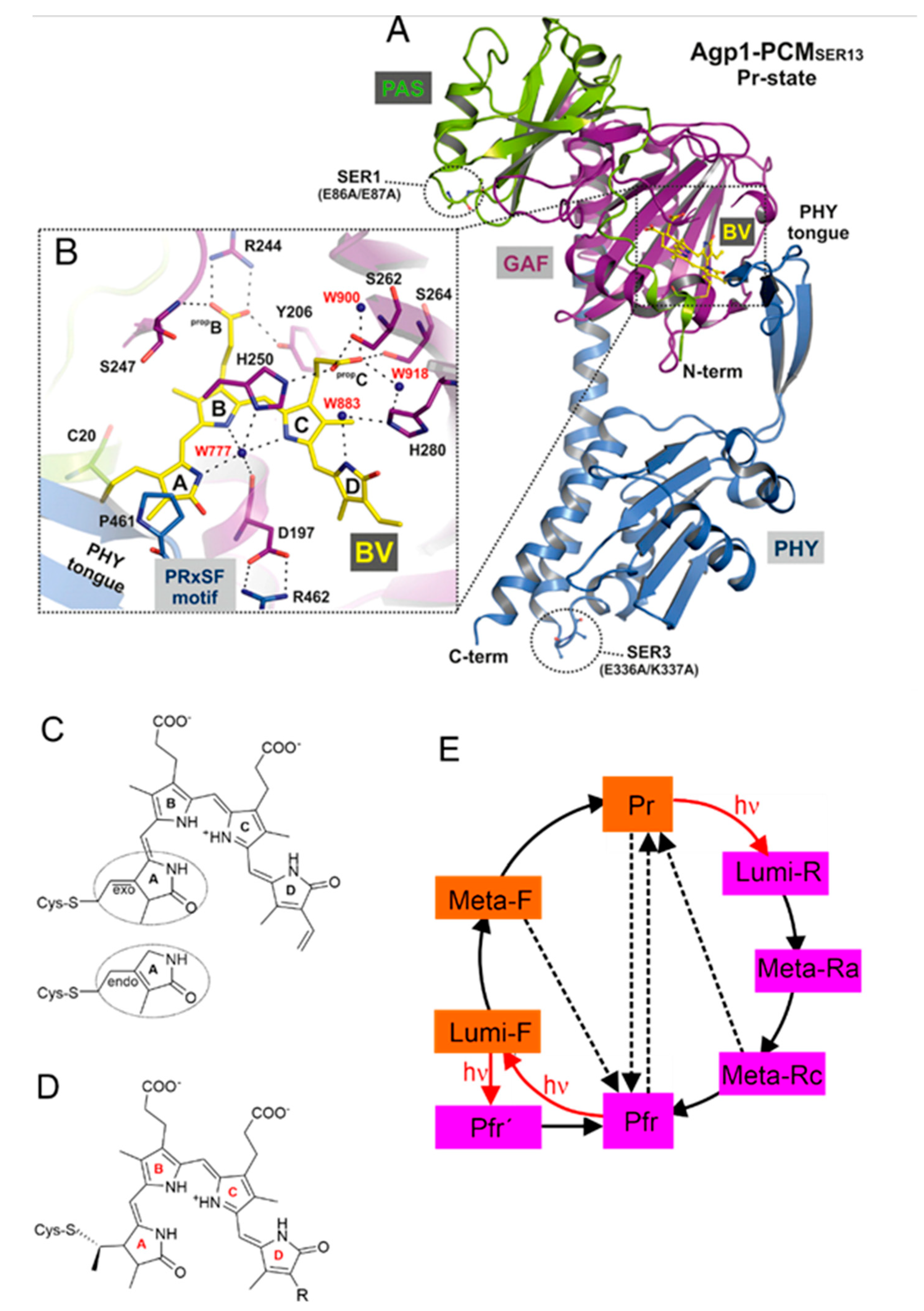

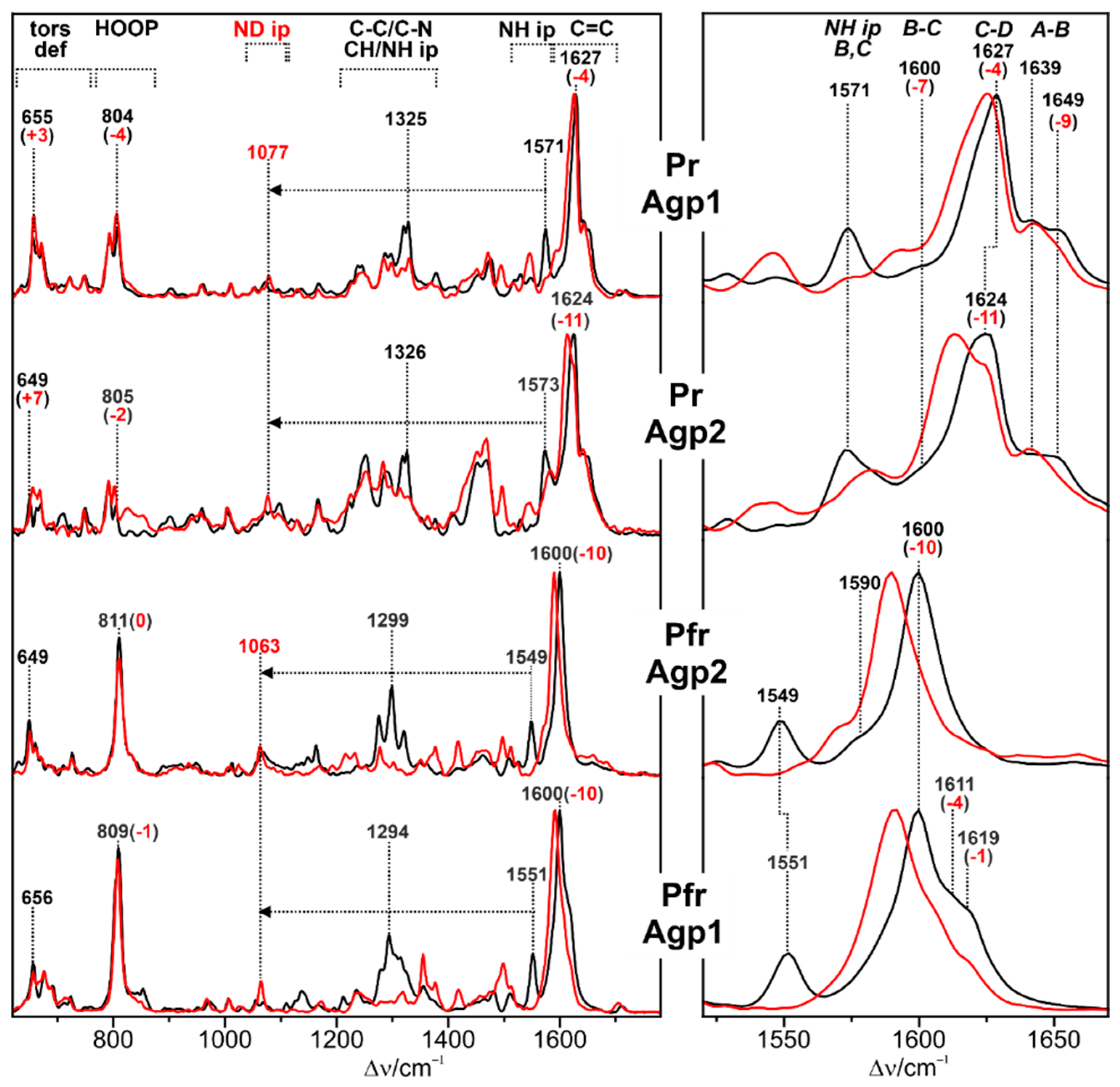

3.1. Parent states

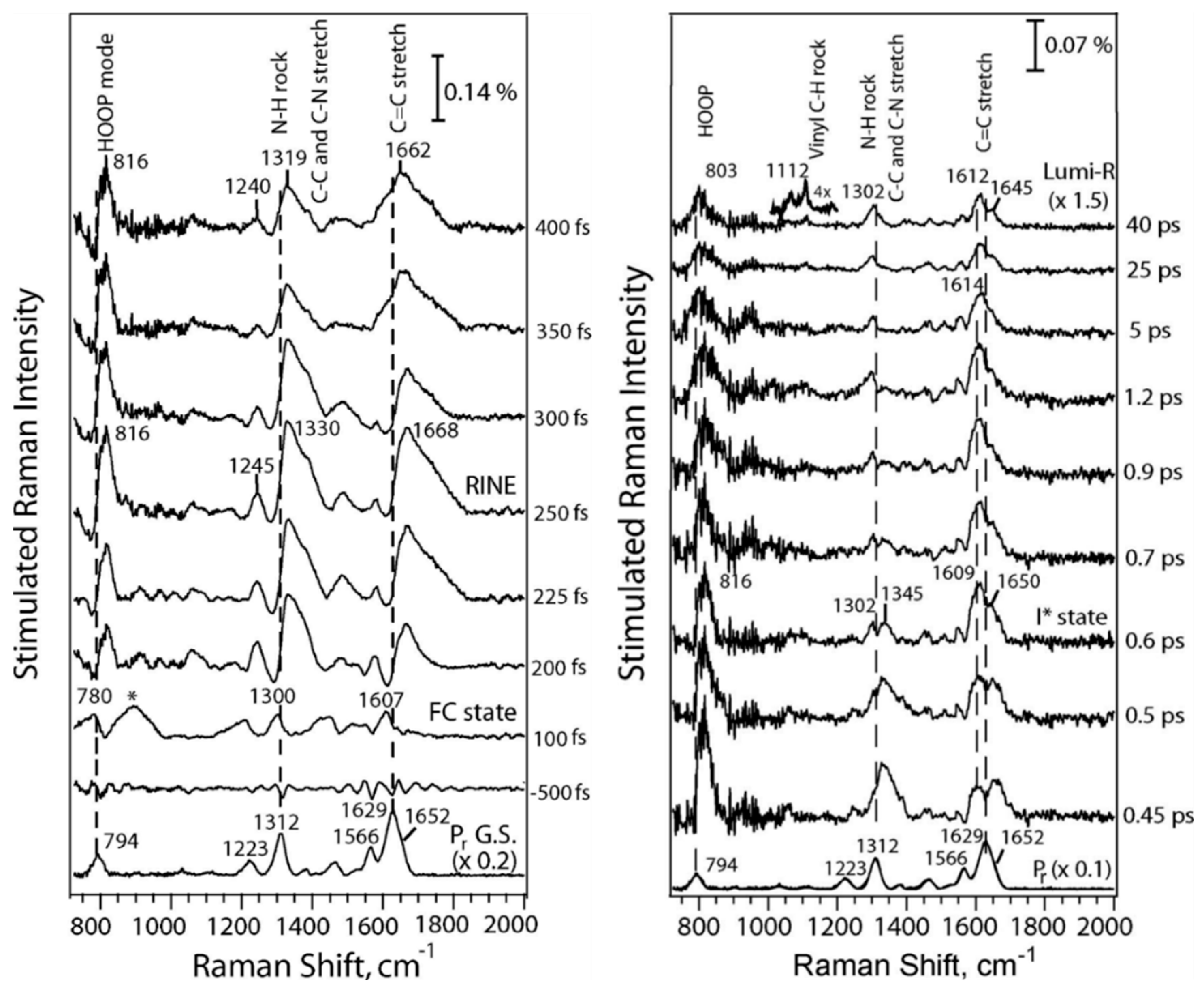

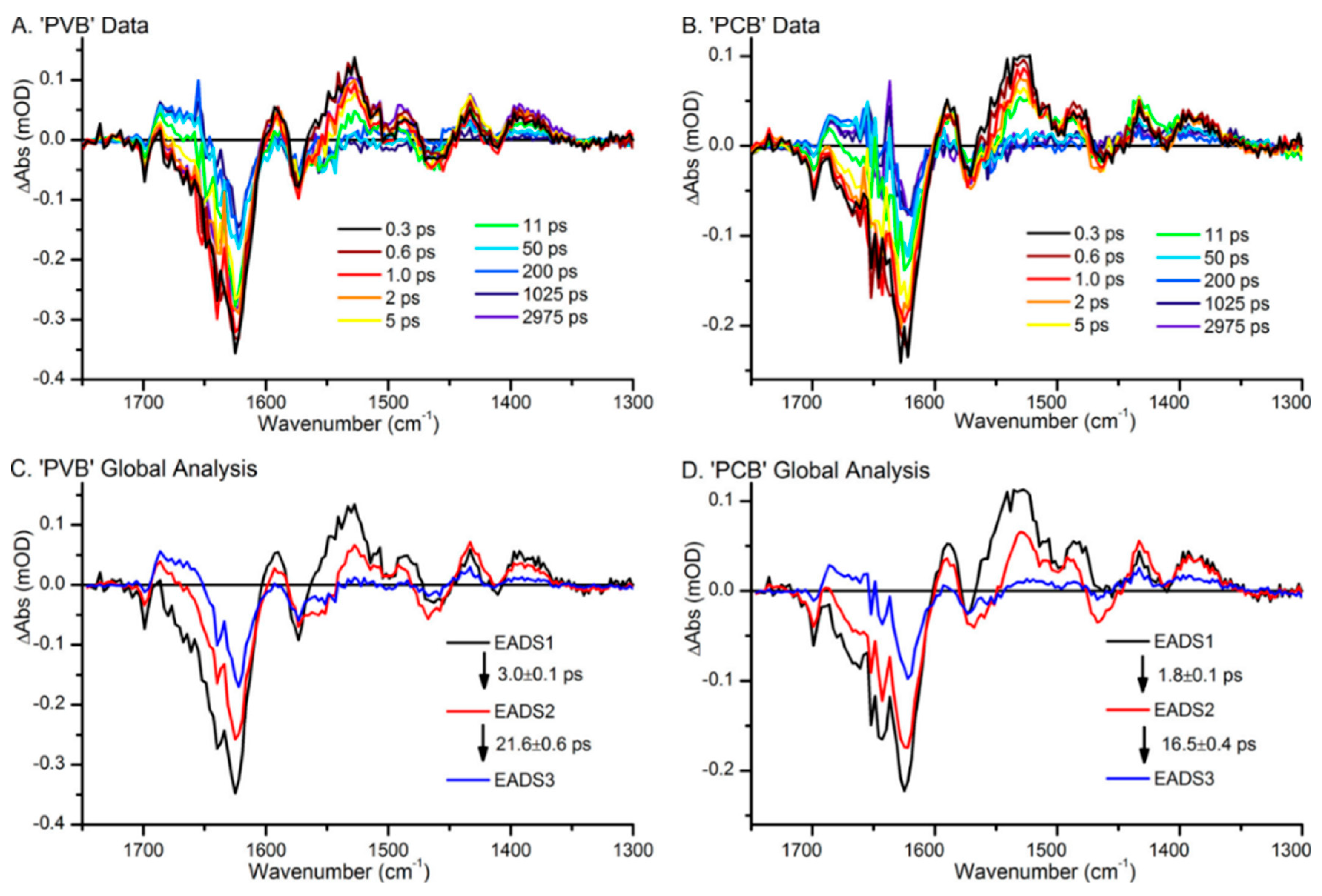

3.2. First events of the photoconversion

3.3. Late events of the photoconversion

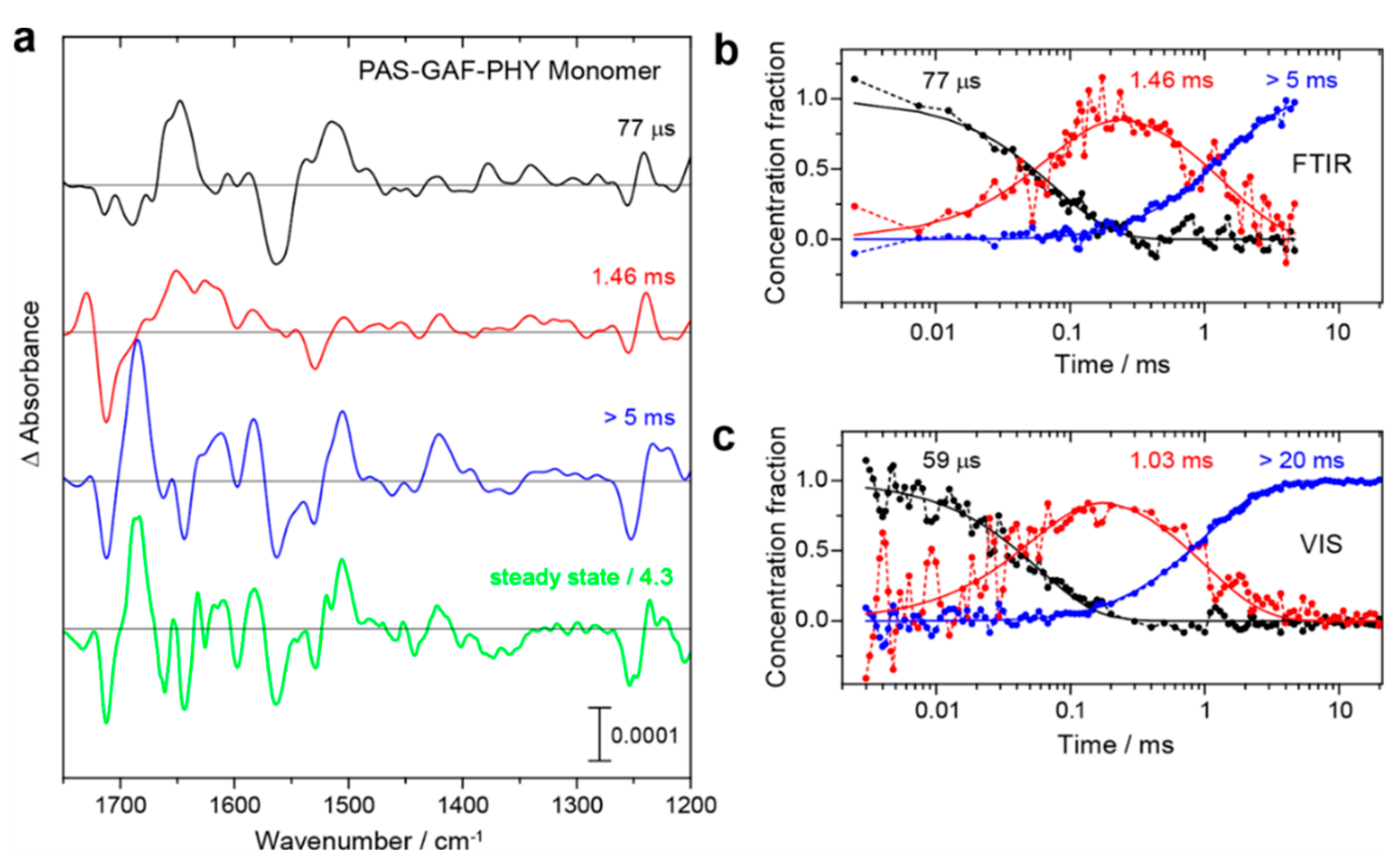

3.4. Thermal back reactions

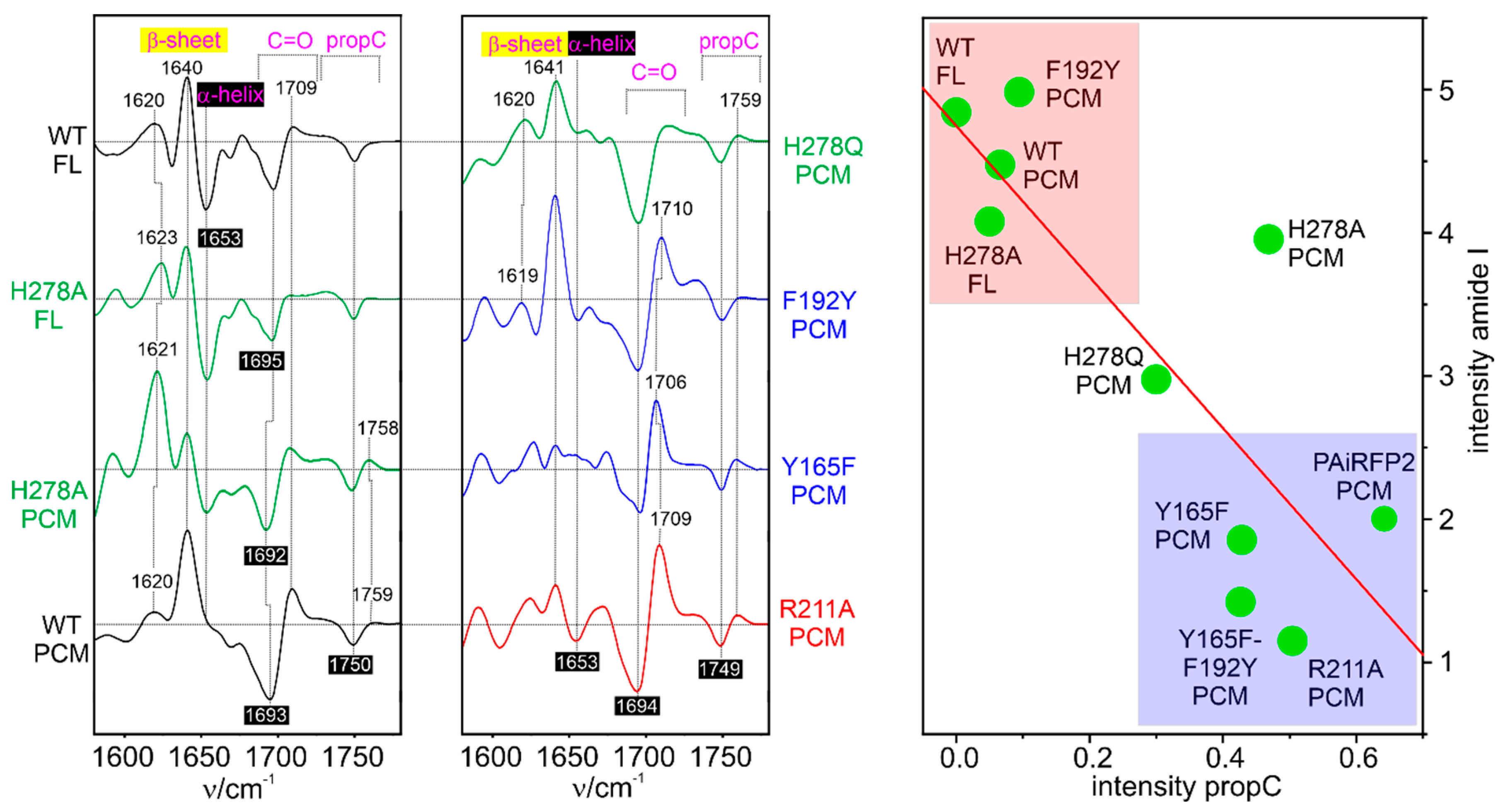

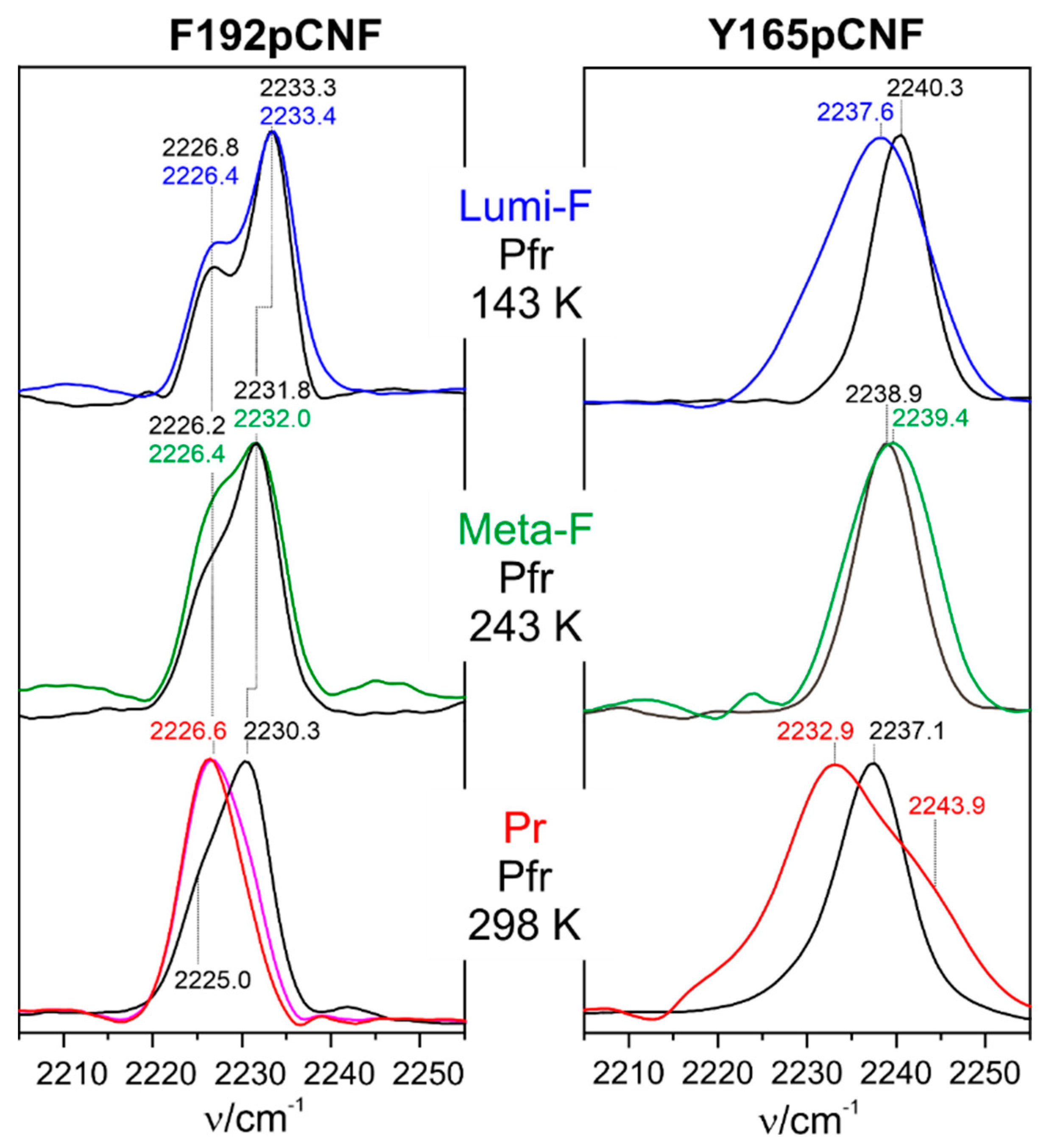

4. Coupling of chromophore and protein structural changes

4.1. Proton transfer and tongue restructuring

4.2. Electric field effects

4.3. Protein-protein interactions

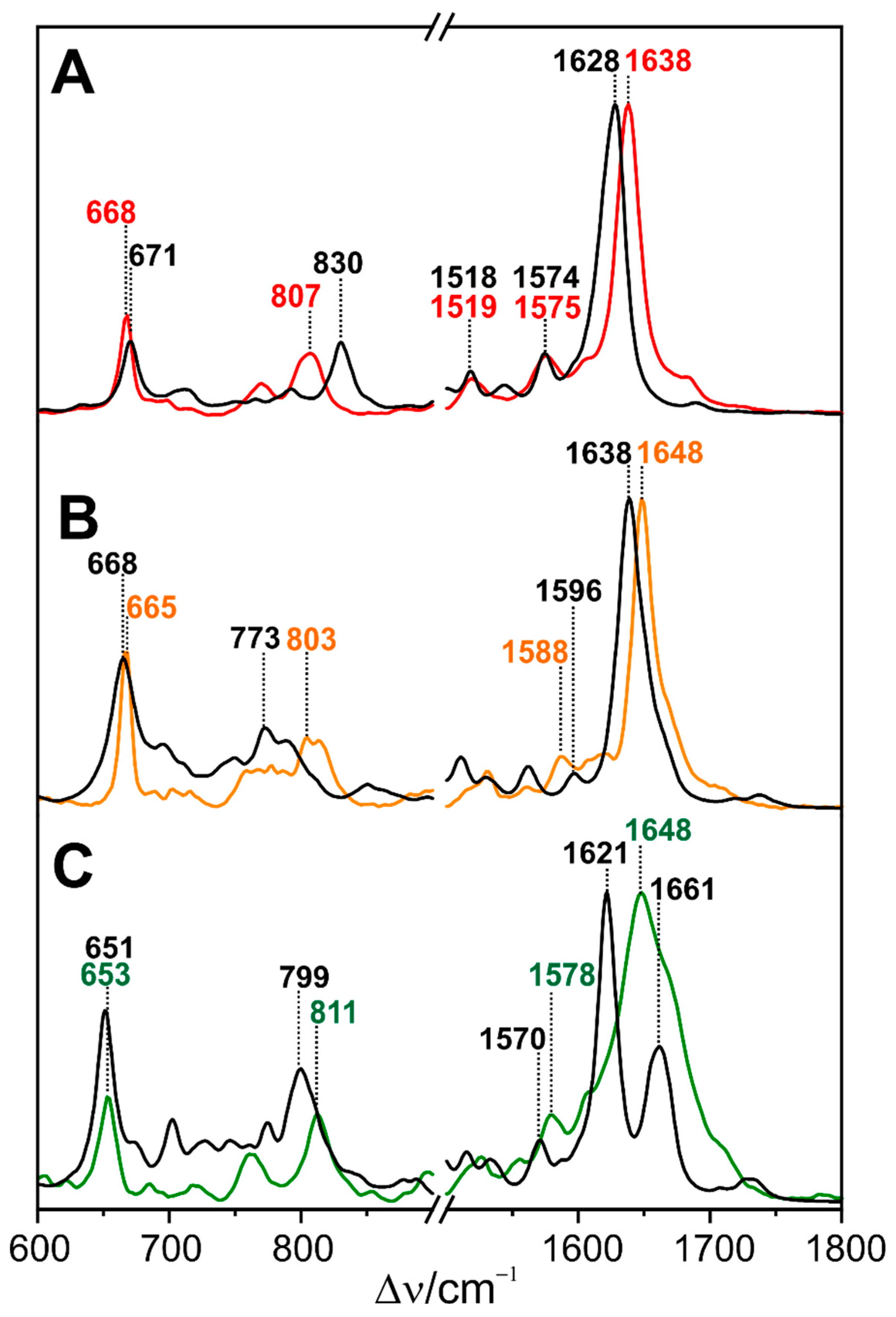

5. Cyanobacteriochromes

6. Fluorescing phytochromes

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borthwick, H.A. Phytochrome Action and Its Time Displays. Am. Nat. 1964, 98, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, W.R.; Rice, H. V. Phytochrome: Chemical and Physical Properties and Mechanism of Action. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1972, 23, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Su, Y.-S.; Lagarias, J.C. Phytochrome Structure and Signaling Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Phytochrome Signaling: Time to Tighten up the Loose Ends. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karniol, B.; Vierstra, R.D. The Pair of Bacteriophytochromes from Agrobacterium Tumefaciens Are Histidine Kinases with Opposing Photobiological Properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2807–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, M.; Ishizuka, T. Cyanobacteriochromes: A New Superfamily of Tetrapyrrole-Binding Photoreceptors in Cyanobacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Moreno, M. V.; Martin, S.S.; Lagarias, J.C. Protein–Chromophore Interactions Controlling Photoisomerization in Red/Green Cyanobacteriochromes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 21, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fushimi, K.; Narikawa, R. Cyanobacteriochromes: Photoreceptors Covering the Entire UV-to-Visible Spectrum. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 57, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, S.; Scheerer, P.; Zubow, K.; Michael, N.; Inomata, K.; Lamparter, T.; Krauß, N. The Crystal Structures of the N-Terminal Photosensory Core Module of Agrobacterium Phytochrome Agp1 as Parallel and Anti-Parallel Dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 20674–20691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Lamparter, T.; Mittmann, F.; Hartmann, E.; Gärtner, W.; Wilde, A.; Börner, T. A Prokaryotic Phytochrome. Nature 1997, 386, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneip, C.; Mozley, D.; Hildebrandt, P.; Gärtner, W.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K. Effect of Chromophore Exchange on the Resonance Raman Spectra of Recombinant Phytochromes. FEBS Lett. 1997, 414, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysik, J.; Lang, C.; Gartner, W.; Rohmer, T.; Essen, L.-O.; Hughes, J. Light-Induced Chromophore Activity and Signal Transduction in Phytochromes Observed by 13C and 15N Magic-Angle Spinning NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 15229–15234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.R.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Forest, K.T.; Vierstra, R.D. A Light-Sensing Knot Revealed by the Structure of the Chromophore-Binding Domain of Phytochrome. Nature 2005, 438, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Stojkovic, E.A.; Kuk, J.; Moffat, K. Crystal Structure of the Chromophore Binding Domain of an Unusual Bacteriophytochrome, RpBphP3, Reveals Residues That Modulate Photoconversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 12571–12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.R.; Zhang, J.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Vierstra, R.D.; Forest, K.T. High Resolution Structure of Deinococcus Bacteriophytochrome Yields New Insights into Phytochrome Architecture and Evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12298–12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Kuk, J.; Moffat, K. Crystal Structure of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Bacteriophytochrome: Photoconversion and Signal Transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 14715–14720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essen, L.-O.; Mailliet, J.; Hughes, J. The Structure of a Complete Phytochrome Sensory Module in the Pr Ground State. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 14709–14714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; von Stetten, D.; Kaminski, S.; Escobar, F. V.; Michael, N.; Daminelli-Widany, G.; Hildebrandt, P. Elucidating Photoinduced Structural Changes in Phytochromes by the Combined Application of Resonance Raman Spectroscopy and Theoretical Methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 99, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, F.; Hildebrandt, P. Vibrational Spectroscopy in Life Science; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Edlung, P.; Takala, H.; Claesson, E.; Henry, L.; Dods, R.; Jehtivuori, H.; Panman, M.; Pande, K.; White, T.; Nakane, T.; et al. The Room Temperature Crystal Structure of a Bacterial Phytochrome Determined by Serial Femtosecond Crystallography. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Hildebrandt, P. Probing Structure and Reaction Dynamics of Proteins Using Time-Resolved Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3577–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockburger, M.; Klusmann, W.; Gattermann, H.; Massig, G.; Peters, R. Photochemical Cycle of Bacteriorhodopsin Studied by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 1979, 18, 4886–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braiman, M.; Mathies, R. Resonance Raman Evidence for an All-Trans to 13-Cis Isomerization in the Proton-Pumping Cycle of Bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry 1980, 19, 5421–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebert, F.; Mäntele, W.; Kreutz, W. Evidence for the Protonation of Two Internal Carboxylic Groups during the Photocycle of Bacteriorhodopsin. Investigation of Kinetic Infrared Spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1982, 141, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, K.; Dollinger, G.; Eisenstein, L.; Singh, A.K.; Zimányi, L. Fourier Transform Infrared Difference Spectroscopy of Bacteriorhodopsin and Its Photoproducts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1982, 79, 4972–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterhelt, D.; Stoeckenius, W. Rhodopsin-like Protein from the Purple Membrane of Halobacterium Halobium. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 233, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sühnel, J.; Hermann, G.; Dornberger, U.; Fritzsche, H. Computer Analysis of Phytochrome Sequences and Reevaluation of the Phytochrome Secondary Structure by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1997, 1340, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerstendorf, H.; Lamparter, T.; Hughes, J.; Gärtner, W.; Siebert, F. The Photoreactions of Recombinant Phytochrome from the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis: A Low-Temperature UV–Vis and FT-IR Spectroscopic Study. Photochem. Photobiol. 2000, 71, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, J.; Morita, E.H.; Hayashi, H.; Furuya, M.; Tasumi, M. Infrared Studies of the Phototransformation of Phytochrome. Chem. Lett. 1990, 1925–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerstendorf, H.; Mummert, E.; Schäfer, E.; Scheer, H.; Siebert, F. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy of Phytochrome: Difference Spectra of the Intermediates of the Photoreactions. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 10793–10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhmann, W.; Becker, A.; Taran, C.; Siebert, F. Time-Resolved FT-IR Absorption Spectroscopy Using a Step-Scan Interferometer. Appl. Spectrosc. 1991, 45, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwert, K. Molecular Reaction Mechanisms of Proteins as Monitored by Time-Resolved FTIR Spectroscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1993, 3, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, E.; Puskar, L.; Bartl, F.J.; Aziz, E.F.; Hegemann, P.; Schade, U. Time-Resolved Infrared Spectroscopic Techniques as Applied to Channelrhodopsin. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarski, P.; Ritter, E.; Hofmann, K.-P.; Hildebrandt, P.; von Stetten, D.; Scheerer, P.; Michael, N.; Lamparter, T.; Bartl, F. Light-Induced Activation of Bacterial Phytochrome Agp1 Monitored by Static and Time-Resolved FTIR Spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottke, T.; Xie, A.; Larsen, D.S.; Hoff, W.D. Photoreceptors Take Charge: Emerging Principles for Light Sensing. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauck, A.F.E.; Hardman, S.J.O.; Kutta, R.J.; Greetham, G.M.; Heyes, D.J.; Scrutton, N.S. The Photoinitiated Reaction Pathway of Full-Length Cyanobacteriochrome Tlr0924 Monitored over 12 Orders of Magnitude. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17747–17757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S.J.O.; Heyes, D.J.; Sazanovich, I. V.; Scrutton, N.S. Photocycle of Cyanobacteriochrome TePixJ. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2909–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thor, J.J.; Ronayne, K.L.; Towrie, M. Formation of the Early Photoproduct Lumi-R of Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1 Observed by Ultrafast Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Groß, R.; Michael, N.; Lamparter, T.; Diller, R. Sub-Picosecond Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy of Phytochrome Agp1 from Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. ChemPhysChem 2007, 8, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, K.C.; Stojković, E.A.; Rupenyan, A.B.; Van Stokkum, I.H.M.; Salumbides, M.; Groot, M.L.; Moffat, K.; Kennis, J.T.M. Primary Reactions of Bacteriophytochrome Observed with Ultrafast Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3778–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Linke, M.; Von Haimberger, T.; Hahn, J.; Matute, R.; González, L.; Schmieder, P.; Heyne, K. Real-Time Tracking of Phytochrome’s Orientational Changes during Pr Photoisomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1408–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübel, J.; Chenchiliyan, M.; Ooi, S.A.; Gustavsson, E.; Isaksson, L.; Kuznetsova, V.; Ihalainen, J.A.; Westenhoff, S.; Maj, M. Transient IR Spectroscopy Identifies Key Interactions and Unravels New Intermediates in the Photocycle of a Bacterial Phytochrome. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 9195–9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Stensitzki, T.; Sauthof, L.; Schmidt, A.; Piwowarski, P.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Michael, N.; Nguyen, A.D.; Szczepek, M.; Brünig, F.N.; et al. Ultrafast Proton-Coupled Isomerization in the Phototransformation of Phytochrome. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kübel, J.; Westenhoff, S.; Maj, M. Giving Voice to the Weak: Application of Active Noise Reduction in Transient Infrared Spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 783, 139059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Michael, N.; Hamm, P. Vibrational Couplings between Protein and Cofactor in Bacterial Phytochrome Agp1 Revealed by 2D-IR Spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strekas, T.C.; Spiro, T.G. Hemoglobin: Resonance Raman Spectra. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1972, 263, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, S.P.A.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathies, R.A. Resonance Raman Spectra of the Pr-Form of Phytochrome. Photochem. Photobiol. 1988, 48, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodor, S.P.A.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathies, R.A. Resonance Raman Analysis of the Pr and Pfr Forms of Phytochrome. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 11141–11146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, P.; Lindemann, P.; Heibel, G.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K.; Hoffmann, A.; Schrader, B. Fourier Transform Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Phytochrome. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 7957–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneip, C.; Hildebrandt, P.; Schlamann, W.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Mark, F.; Schaffner, K. Protonation State and Structural Changes of the Tetrapyrrole Chromophore during the Pr → Pfr Phototransformation of Phytochrome: A Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Study. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 15185–15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucki, B.; von Stetten, D.; Seibeck, S.; Lamparter, T.; Michael, N.; Mroginski, M.A.; Otto, H.; Murgida, D.H.; Heyn, M.P.; Hildebrandt, P. Light-Induced Proton Release of Phytochrome Is Coupled to the Transient Deprotonation of the Tetrapyrrole Chromophore. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34358–34364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraskov, A.; Nguyen, A.D.; Goerling, J.; Buhrke, D.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Fernandez Lopez, M.; Michael, N.; Sauthof, L.; Schmidt, A.; Piwowarski, P.; et al. Intramolecular Proton Transfer Controls Protein Structural Changes in Phytochrome. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, F.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathias, R.A. Resonance Raman Analysis of Chromophore Structure in the Lumi-R Photoproduct of Phytochrome. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 15997–16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokutomi, S.; Mizutani, Y.; Anni, H.; Kitagawa, T. Resonance Raman Spectra of Large Pea Phytochrome at Ambient Temperature. Difference in Chromophore Protonation between Red- and Far Red-Absorbing Forms. FEBS Lett. 1990, 269, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, Y.; Kitagawa, T.; Tokutomi, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Horitsu, K. Resonance Raman Study on Intact Pea Phytochrome and Its Model Compounds: Evidence for Proton Migration during the Phototransformation. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 10693–10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, Y.; Tokutomi, S.; Kitagawa, T. Resonance Raman Spectra of the Intermediates in Phototransformation of Large Phytochrome: Deprotonation of the Chromophore in the Bleached Intermediate. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Jäger, W.; Prenzel, C.J.; Brehm, G.; Sai, P.S.M.; Scheer, H.; Lottspeich, F. Photophysics of Phycoerythrocyanins from the Cyanobacterium Westiellopsis Prolifica Studied by Time-Resolved Fluorescence and Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Spectroscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1994, 26, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, T.M.; Kim, J.; Chumanov, G.D. Application of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy to Biological Systems. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1991, 22, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgida, D.H.; Hildebrandt, P. Disentangling Interfacial Redox Processes of Proteins by SERR Spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, G.; Müller, E.; Werncke, W.; Pfeiffer, M.; Kim, M.-B.; Lau, A. A Resonance CARS Study of Phytochrome in Its Red Absorbing Form. Biochem. und Physiol. der Pflanz. 1990, 186, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrens, D.L.; Holt, R.E.; Rospendowski, B.N.; Song, P.S.; Cotton, T.M. Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering Spectroscopy Applied to Phytochrome and Its Model Compounds. 2. Phytochrome and Phycocyanin Chromophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 9162–9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rospendowski, B.N.; Farrens, D.L.; Cotton, T.M.; Song, P.S. Surface Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering (SERRS) as a Probe of the Structural Differences between the Pr and Pfr Forms of Phytochrome. FEBS Lett. 1989, 258, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontiera, R.R.; Mathies, R.A. Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. Laser Photon. Rev. 2010, 5, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, J.; Frontiera, R.R.; Taylor, K.C.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathies, R.A. Ultrafast Excited-State Isomerization in Phytochrome Revealed by Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 1784–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillane, K.M.; Dasgupta, J.; Mathies, R.A. Conformational Homogeneity and Excited-State Isomerization Dynamics of the Bilin Chromophore in Phytochrome Cph1 from Resonance Raman Intensities. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T. Investigation of Higher Order Structures of Proteins by Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Progr. Biophys. Molec. Biol. 1992, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama, A.; Nakazawa, M.; Manabe, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Harada, I. Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectra of Phytochrome : A Comparison of the Environments of Tryptophan Side Chains between Red Light-Absorbing and Far-Red Light-Absorbing Forms. Photochem. Photobiol. 1993, 57, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, Y.; Kaminaka, S.; Kitagawa, T.; Tokutomi, S. Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectra of Pea Intact, Large, and Small Phytochromes: Differences in Molecular Topography of the Red- and Far-Red-Absorbing Forms. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 6916–6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stetten, D.; Günther, M.; Scheerer, P.; Murgida, D.H.; Mroginski, M.A.; Krauß, N.; Lamparter, T.; Zhang, J.; Anstrom, D.M.; Vierstra, R.D.; et al. Chromophore Heterogeneity and Photoconversion in Phytochrome Crystals and Solution Studied by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4753–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; von Stetten, D.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Strauss, H.M.; Kaminski, S.; Scheerer, P.; Günther, M.; Murgida, D.H.; Schmieder, P.; Bongards, C.; et al. Chromophore Structure of Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1 in the Pr State: Reconciling Structural and Spectroscopic Data by QM/MM Calculations. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 4153–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Sauthof, L.; Szczepek, M.; Lopez, M.F.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Qureshi, B.M.; Michael, N.; Buhrke, D.; Stevens, T.; Kwiatkowski, D.; et al. Structural Snapshot of a Bacterial Phytochrome in Its Functional Intermediate State. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerstendorf, H.; Benda, C.; Gärtner, W.; Storf, M.; Scheer, H.; Siebert, F. FTIR Studies of Phytochrome Photoreactions Reveal the C=O Bands of the Chromophore: Consequences for Its Protonation States, Conformation, and Protein Interaction. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 14952–14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Thor, J.J.; Fisher, N.; Rich, P.R. Assignments of the Pfr - Pr FTIR Difference Spectrum of Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1 Using15N And13C Isotopically Labeled Phycocyanobilin Chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 20597–20604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; Piwowarski, P.; Salewski, J.; Michael, N.; Fernandez Lopez, M.; Rupp, A.; Qureshi, M.B.; Scheerer, P.; Bartl, F.; Frankenberg-Dinkel, N.; et al. A Protonation-Coupled Feedback Mechanism Controls the Signalling Process in Bathy Phytochromes. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüdiger, W.; Thümmler, F.; Cmiel, E.; Schneider, S. Chromophore Structure of the Physiologically Active Form (Pfr) of Phytochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1983, 80, 6244–6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, T.; Ozaki, Y. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Metalloporphyrins. Met. Complexes with Tetrapyrrole Ligands I 2006, 71–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Czernuszewicz, R.S.; Kincaid, J.R.; Su, Y.O.; Spiro, T.G. Consistent Porphyrin Force Field. 1. Normal-Mode Analysis for Nickel Porphine and Nickel Tetraphenylporphine from Resonance Raman and Infrared Spectra and Isotope Shifts. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; Czernuszewicz, R.S.; Kincaid, J.R.; Stein, P.; Spiro, T.G. Consistent Porphyrin Force Field. 2. Nickel Octaethylporphyrin Skeletal and Substituent Mode Assignments from 15N, Meso-D4, and Methylene-D16 Raman and Infrared Isotope Shifts. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulies, L.; Stockburger, M. Spectroscopic Studies on Model Compounds of the Phytochrome Chromophore. Protonation and Deprotonation of Biliverdin Dimethyl Ester. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 743–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Németh, K.; Magdé, I.; Müller, M.; Robben, U.; Della Védova, C.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mark, F. Calculation of the Vibrational Spectra of Linear Tetrapyrroles. 2. Resonance Raman Spectra of Hexamethylpyrromethene Monomers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 10885–10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneip, C.; Parbel, A.; Foerstendorf, H.; Scheer, H.; Siebert, F.; Hildebrandt, P. Fourier Transform Near-Infrared Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Alpha-Subunit of Phycoerythrocyanin and Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Mastigocladus Laminosus. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1998, 29, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, F.; Murphy, J.T.; Haas, J.A.; McDowell, M.T.; Van Der Hoef, I.; Lugtenburg, J.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathies, R.A. Probing the Photoreaction Mechanism of Phytochrome through Analysis of Resonance Raman Vibrational Spectra of Recombinant Analogues. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Kneip, C.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mark, F. Excited State Geometry Calculations and the Resonance Raman Spectrum of Hexamethylpyrromethene. J. Mol. Struct. 2003, 661–662, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Németh, K.; Bauschlicher, T.; Klotzbücher, W.; Goddard, R.; Heinemann, O.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mark, F. Calculation of Vibrational Spectra of Linear Tetrapyrroles. 3. Hydrogen-Bonded Hexamethylpyrromethene Dimers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Murgida, D.H.; Hildebrandt, P. Calculation of Vibrational Spectra of Linear Tetrapyrroles. 4. Methine Bridge C-H Out-of-Plane Modes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 10564–10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, P.; Siebert, F.; Schwinté, P.; Gärtner, W.; Murgida, D.H.; Mroginski, M.A.; Sharda, S.; von Stetten, D. The Chromophore Structures of the Pr States in Plant and Bacterial Phytochromes. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 2410–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; von Stetten, D.; Günther-Lütkens, M.; Keidel, A.; Michael, N.; Lamparter, T.; Essen, L.-O.; Hughes, J.; Gärtner, W.; von Stetten, D.; et al. Conformational Heterogeneity of the Pfr Chromophore in Plant and Cyanobacterial Phytochromes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2015, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulies, L.; Toporowicz, M. Resonance Raman Study of Model Compounds of the Phytochrome Chromophore. 2. Biliverdin Dimethyl Ester. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 7331–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.E.; Farrens, D.L.; Song, P.S.; Cotton, T.M. Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering Spectroscopy Applied to Phytochrome and Its Model Compounds. 2. Phytochrome and Phycocyanin Chromophorest. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 9156–9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatzki, J.; Fischer, R.; Scheer, H.; Siebert, F. Fourier-Transform Raman Spectroscopy Applied to Photobiological Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 5903–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, K.; Matysik, J.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mark, F. Vibrational Analysis of Biliverdin Dimethyl Ester. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 11887–11900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, J.; Hildebrandt, P.; Smit, K.; Korkin, A.; Mark, F.; Gärtner, W.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K.; Schrader, B. Vibrational Analysis of Biliverdin IXα Dimethyl Ester Conformers. J. Mol. Struct. 1995, 348, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, J.; Hildebrandt, P.; Smit, K.; Mark, F.; Gärtner, W.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K.; Schrader, B. Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Isomers of Biliverdin Dimethyl Ester. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1997, 15, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipp, B.; Kneip, K.; Matysik, J.; Gärtner, W.; Hildebrandt, P.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K. Regioselective Deuteration and Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Characterization of Biliverdin and Phycocyanobilin. Chem. - A Eur. J. 1997, 3, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdó, I.; Németh, K.; Mark, F.; Hildebrandt, P.; Schaffner, K. Calculation of Vibrational Spectra of Linear Tetrapyrroles. 1. Global Sets of Scaling Factors for Force Fields Derived by Ab Initio and Density Functional Theory Methods. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Murgida, D.H.; Von Stetten, D.; Kneip, C.; Mark, F.; Hildebrandt, P. Determination of the Chromophore Structures in the Photoinduced Reaction Cycle of Phytochrome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16734–16735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Murgida, D.H.; Hildebrandt, P. The Chromophore Structural Changes during the Photocycle of Phytochrome: A Combined Resonance Raman and Quantum Chemical Approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneip, C.; Hildebrandt, P.; Németh, K.; Mark, F.; Schaffner, K. Interpretation of the Resonance Raman Spectra of Linear Tetrapyrroles Based on DFT Calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 311, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, M.; Tavan, P.; Hutter, J.; Parrinello, M. A Hybrid Method for Solutes in Complex Solvents: Density Functional Theory Combined with Empirical Force Fields. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 10452–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Karplus, M. Molecular Properties from Combined QM/MM Methods. I. Analytical Second Derivative and Vibrational Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 1133–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, H.M.; Thiel, W. QM/MM Methods for Biological Systems. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 268, 173–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Mark, F.; Thiel, W.; Hildebrandt, P. Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Calculation of the Raman Spectra of the Phycocyanobilin Chromophore in α-C-Phycocyanin. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Kaminski, S.; Hildebrandt, P. Raman Spectra of the Phycoviolobilin Cofactor in Phycoerythrocyanin Calculated by QM/MM Methods. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salewski, J.; Escobar, F.V.; Kaminski, S.; Von Stetten, D.; Keidel, A.; Rippers, Y.; Michael, N.; Scheerer, P.; Piwowarski, P.; Bartl, F.; et al. Structure of the Biliverdin Cofactor in the Pfr State of Bathy and Prototypical Phytochromes. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16800–16814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takiden, A.; Velazquez-Escobar, F.; Dragelj, J.; Woelke, A.L.; Knapp, E.-W.; Piwowarski, P.; Bartl, F.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mroginski, M.A. Structural and Vibrational Characterization of the Chromophore Binding Site of Bacterial Phytochrome Agp1. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroginski, M.A.; Kaminski, S.; Von Stetten, D.; Ringsdorf, S.; Gärtner, W.; Essen, L.O.; Hildebrandt, P. Structure of the Chromophore Binding Pocket in the Pr State of Plant Phytochrome PhyA. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilfeld, P.; Rüdiger, W. Absorption Spectra of Phytochrome Intermediates. Zeitschrift fur Naturforsch. - Sect. C J. Biosci. 1985, 40, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, A.R.; Wendler, J.; Ruzsicska, B.P.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K. Picosecond Time-Resolved and Stationary Fluorescence of Oat Phytochrome Highly Enriched in the Native 124 KDa Protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1984, 791, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.F.; Dahl, M.; Escobar, F.V.; Bonomi, H.R.; Kraskov, A.; Michael, N.; Mroginski, M.A.; Scheerer, P.; Hildebrandt, P. Photoinduced Reaction Mechanisms in Prototypical and Bathy Phytochromes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 11967–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez Escobar, F.; Buhrke, D.; Michael, N.; Sauthof, L.; Wilkening, S.; Tavraz, N.N.; Salewski, J.; Frankenberg-Dinkel, N.; Mroginski, M.A.; Scheerer, P.; et al. Common Structural Elements in the Chromophore Binding Pocket of the Pfr State of Bathy Phytochromes. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, L.H.; Goldbaum, F.A.; Fernández López, M.; Rinaldi, J.; Velázquez-Escobar, F.; Bonomi, H.R.; Klinke, S.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mroginski, M.A.; Vojnov, A.A.; et al. Structure of the Full-Length Bacteriophytochrome from the Plant Pathogen Xanthomonas Campestris Provides Clues to Its Long-Range Signaling Mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3702–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zienicke, B.; Molina, I.; Glenz, R.; Singer, P.; Ehmer, D.; Escobar, F.V.; Hildebrandt, P.; Diller, R.; Lamparter, T. Unusual Spectral Properties of Bacteriophytochrome Agp2 Result from a Deprotonation of the Chromophore in the Red-Absorbing Form Pr. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 31738–31751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillane, K.M.; Dasgupta, J.; Lagarias, J.C.; Mathies, R.A. Homogeneity of Phytochrome Cph1 Vibronic Absorption Revealed by Resonance Raman Intensity Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13946–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; Hildebrandt, T.; Utesch, T.; Schmitt, F.J.; Seuffert, I.; Michael, N.; Schulz, C.; Mroginski, M.A.; Friedrich, T.; Hildebrandt, P. Structural Parameters Controlling the Fluorescence Properties of Phytochromes. Biochemistry 2013, 53, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenchiliyan, M.; Kübel, J.; Ooi, S.A.; Salvadori, G.; Mennucci, B.; Westenhoff, S.; Maj, M. Ground-State Heterogeneity and Vibrational Energy Redistribution in Bacterial Phytochrome Observed with Femtosecond 2D IR Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 085103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; Lang, C.; Takiden, A.; Schneider, C.; Balke, J.; Hughes, J.; Alexiev, U.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mroginski, M.A. Protonation-Dependent Structural Heterogeneity in the Chromophore Binding Site of Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Stetten, D.; Seibeck, S.; Michael, N.; Scheerer, P.; Mroginski, M.A.; Murgida, D.H.; Krauss, N.; Heyn, M.P.; Hildebrandt, P.; Borucki, B.; et al. Highly Conserved Residues Asp-197 and His-250 in Agp1 Phytochrome Control the Proton Affinity of the Chromophore and Pfr Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.R.; Zhang, J.; von Stetten, D.; Günther, M.; Murgida, D.H.; Mroginski, M.A.; Walker, J.M.; Forest, K.T.; Hildebrandt, P.; Vierstra, R.D. Mutational Analysis of Deinococcus Radiodurans Bacteriophytochrome Reveals Key Amino Acids Necessary for the Photochromicity and Proton Exchange Cycle of Phytochromes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 12212–12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Sauthof, L.; Wilkening, S.; Herder, N.; Tavraz, N.N.; Willoweit, M.; Keidel, A.; Utesch, T.; Mroginski, M.A.; et al. The Role of Local and Remote Amino Acid Substitutions for Optimizing Fluorescence in Bacteriophytochromes: A Case Study on IRFP. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Tavraz, N.N.; Shcherbakova, D.M.; Sauthof, L.; Moldenhauer, M.; Vélazquez Escobar, F.; Verkhusha, V. V.; Hildebrandt, P.; Friedrich, T. Chromophore Binding to Two Cysteines Increases Quantum Yield of Near-Infrared Fluorescent Proteins. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraskov, A.; Buhrke, D.; Scheerer, P.; Shaef, I.; Sanchez, J.C.; Carrillo, M.; Noda, M.; Feliz, D.; Stojković, E.A.; Hildebrandt, P. On the Role of the Conserved Histidine at the Chromophore Isomerization Site in Phytochromes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 13696–13709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraskov, A.; Von Sass, J.; Nguyen, A.D.; Hoang, T.O.; Buhrke, D.; Katz, S.; Michael, N.; Kozuch, J.; Zebger, I.; Siebert, F.; et al. Local Electric Field Changes during the Photoconversion of the Bathy Phytochrome Agp2. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 2967–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remberg, A.; Lindner, I.; Lamparter, T.; Hughes, J.; Kneip, C.; Hildebrandt, P.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Gärtner, W.; Schaffner, K. Raman Spectroscopic and Light-Induced Kinetic Characterization of a Recombinant Phytochrome of the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 13389–13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, S.; Guan, K.; Shenkutie, S.; Feiler, C.; Weiss, M.; Kraskov, A.; Buhrke, D.; Hildebrandt, P.; Hughes, J. Structural Insights into Photoactivation and Signalling in Plant Phytochromes. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlamann, W.; Kneip, C.; Schaffner, K.; Braslavsky, S. .; Hildebrandt, P. Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Tryptic 39-KDa Fragment of Phytochrome. FEBS Lett. 2002, 482, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez Escobar, F.; Buhrke, D.; Fernandez Lopez, M.; Shenkutie, S.M.; von Horsten, S.; Essen, L.O.; Hughes, J.; Hildebrandt, P. Structural Communication between the Chromophore-Binding Pocket and the N-Terminal Extension in Plant Phytochrome PhyB. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinté, P.; Foerstendorf, H.; Hussain, Z.; Gärtner, W.; Mroginski, M.A.; Hildebrandt, P.; Siebert, F. FTIR Study of the Photoinduced Processes of Plant Phytochrome Phya Using Isotope-Labeled Bilins and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamparter, T.; Krauß, N.; Scheerer, P. Phytochromes from Agrobacterium Fabrum. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucki, B.; Seibeck, S.; Heyn, M.P.; Lamparter, T. Characterization of the Covalent and Noncovalent Adducts of Agp1 Phytochrome Assembled with Biliverdin and Phycocyanobilin by Circular Dichroism and Flash Photolysis. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 6305–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Lopez, M.; Nguyen, A.D.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; González, R.; Michael, N.; Nogacz, Ż.; Piwowarski, P.; Bartl, F.; Siebert, F.; Heise, I.; et al. Role of the Propionic Side Chains for the Photoconversion of Bacterial Phytochromes. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3504–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stetten, D.; Günther, M.; Frankenberg-Dinkel, N.; Brandt, S.; Hildebrandt, P. The Fungal Phytochrome FphA from Aspergillus Nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 34605–34614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sineshchekov, V.A. Photobiophysics and Photobiochemistry of the Heterogeneous Phytochrome System. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1228, 125–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savikhin, S.; Struve, W.S.; Wells, T.; Song, P.S. Ultrafast Pump-Probe Spectroscopy of Native Etiolated Oat Phytochrome. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 7512–7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandori, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Tokutomi, S. Primary Process of Phytochrome: Initial Step of Photomorphogenesis in Green Plants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10958–10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, J.; Hildebrandt, P.; Schlamann, W.; Braslavsky, S.E.; Schaffner, K. Fourier-Transform Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Intermediates of the Phytochrome Photocycle. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 10497–10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; Kneip, C.; Michael, N.; Hildebrandt, T.; Tavraz, N.; Gärtner, W.; Hughes, J.; Friedrich, T.; Scheerer, P.; Mroginski, M.A.; et al. The Lumi-R Intermediates of Prototypical Phytochromes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 4044–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wilderen, L.J.G.W.; Clark, I.P.; Towrie, M.; Van Thor, J.J. Mid-Infrared Picosecond Pump-Dump-Probe and Pump-Repump-Probe Experiments to Resolve a Ground-State Intermediate in Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 16354–16364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, M.; Yang, Y.; Zienicke, B.; Hammam, M.A.S.; Von Haimberger, T.; Zacarias, A.; Inomata, K.; Lamparter, T.; Heyne, K. Electronic Transitions and Heterogeneity of the Bacteriophytochrome Pr Absorption Band: An Angle Balanced Polarization Resolved Femtosecond VIS Pump-IR Probe Study. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 1756–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenngren, N.; Edlund, P.; Takala, H.; Stucki-Buchli, B.; Rumfeldt, J.; Peshev, I.; Häkkänen, H.; Westenhoff, S.; Ihalainen, J.A. Coordination of the Biliverdin D-Ring in Bacteriophytochromes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 18216–18225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Groß, R.; Wolf, M.M.N.; Diller, R.; Michael, N.; Lamparter, T. Subpicosecond Midinfrared Spectroscopy of the Pfr Reaction of Phytochrome Agp1 from Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Stensitzki, T.; Lang, C.; Hughes, J.; Mroginski, M.A.; Heyne, K. Ultrafast Protein Response in the Pfr State of Cph1 Phytochrome. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Heyne, K.; Mathies, R.A.; Dasgupta, J. Non-Bonded Interactions Drive the Sub-Picosecond Bilin Photoisomerization in the Pfr State of Phytochrome Cph1. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensitzki, T.; Yang, Y.; Wölke, A.L.; Knapp, E.W.; Hughes, J.; Mroginski, M.A.; Heyne, K. Influence of Heterogeneity on the Ultrafast Photoisomerization Dynamics of Pfr in Cph1 Phytochrome. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinté, P.; Mroginski, M.-A.; Siebert, F.; Hildebrandt, P.; Sharda, S.; Gärtner, W. The Photoreactions of Recombinant Phytochrome CphA from the Cyanobacterium Calothrix PCC7601: A Low-Temperature UV-Vis and FTIR Study. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 85, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takala, H.; Björling, A.; Berntsson, O.; Lehtivuori, H.; Niebling, S.; Hoernke, M.; Kosheleva, I.; Henning, R.; Menzel, A.; Ihalainen, J.A.; et al. Signal Amplification and Transduction in Phytochrome Photosensors. Nature 2014, 509, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, E.A.; Toh, K.C.; Alexandre, M.T.A.; Baclayon, M.; Moffat, K.; Kennis, J.T.M. FTIR Spectroscopy Revealing Light-Dependent Refolding of the Conserved Tongue Region of Bacteriophytochrome. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2512–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihalainen, J.A.; Gustavsson, E.; Schroeder, L.; Donnini, S.; Lehtivuori, H.; Isaksson, L.; Thöing, C.; Modi, V.; Berntsson, O.; Stucki-Buchli, B.; et al. Chromophore-Protein Interplay during the Phytochrome Photocycle Revealed by Step-Scan FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12396–12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, J.C.; Rapoport, H. Chromopeptides from Phytochrome. The Structure and Linkage of the PR Form of the Phytochrome Chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4821–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Kuhlmann, U.; Michael, N.; Hildebrandt, P. The Photoconversion of Phytochrome Includes an Unproductive Shunt Reaction Pathway. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga, G.; Lopez, M.F.; Fischer, P.; Piwowarski, P.; Nogacz, Ż.; Kraskov, A.; Buhrke, D.; Escobar, F.V.; Michael, N.; Siebert, F.; et al. Light-and Temperature-Dependent Dynamics of Chromophore and Protein Structural Changes in Bathy Phytochrome Agp2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 18197–18205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, J.J. Van; Borucki, B.; Crielaard, W.; Otto, H.; Lamparter, T.; Hughes, J.; Hellingwerf, K.J.; Heyn, M.P. Light-Induced Proton Release and Proton Uptake Reactions in the Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1. 2001, 11460–11471. [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.D.; Boxer, S.G. Measuring Electric Fields and Noncovalent Interactions Using the Vibrational Stark Effect. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-May, P.; Garcia, M.E. Electric Field-Driven Disruption of a Native β-Sheet Protein Conformation and Generation of a Helix-Structure. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suydam, I.T.; Boxer, S.G. Vibrational Stark Effects Calibrate the Sensitivity of Vibrational Probes for Electric Fields in Proteins. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 12050–12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.D.; Bagchi, S.; Boxer, S.G. Measuring Electrostatic Fields in Both Hydrogen-Bonding and Non-Hydrogen-Bonding Environments Using Carbonyl Vibrational Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11181–11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farfarman, A.T.; Sigala, P.A.; Herschlag, D.; Boxer, S.G. Decomposition of Vibrational Shifts of Nitriles into Electrostatic and Hydrogen Bonding Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12811–12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fafarman, A.T.; Webb, L.J.; Chuang, J.I.; Boxer, S.G. Site-Specific Conversion of Cysteine Thiols into Thiocyanate Creates an IR Probe for Electric Fields in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13356–13357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.D.; Young, T.S.; Jahnz, M.; Ahmad, I.; Spraggon, G.; Schultz, P.G. An Evolved Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthetase with Atypical Polysubstrate Specificity. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1894–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biava, H.; Schreiber, T.; Katz, S.; Völler, J.S.; Stolarski, M.; Schulz, C.; Michael, N.; Budisa, N.; Kozuch, J.; Utesch, T.; et al. Long-Range Modulations of Electric Fields in Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 8330–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurttila, M.; Stucki-Buchli, B.; Rumfeldt, J.; Schroeder, L.; Häkkänen, H.; Liukkonen, A.; Takala, H.; Kottke, T.; Ihalainen, J.A. Site-by-Site Tracking of Signal Transduction in an Azidophenylalanine-Labeled Bacteriophytochrome with Step-Scan FTIR Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 5615–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, L.N.; Pitzer, M.E.; Ankomah, P.O.; Boxer, S.G.; Fenlon, E.E. Vibrational Stark Effect Probes for Nucleic Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 11611–11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourinchas, G.; Heintz, U.; Winkler, A. Asymmetric Activation Mechanism of a Homodimeric Red Light-Regulated Photoreceptor. Elife 2018, 7, e34815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrke, D.; Gourinchas, G.; Müller, M.; Michael, N.; Hildebrandt, P.; Winkler, A. Distinct Chromophore–Protein Environments Enable Asymmetric Activation of a Bacteriophytochrome-Activated Diguanylate Cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulijasz, A.T.; Cornilescu, G.; von Stetten, D.; Kaminski, S.; Mroginski, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Bhaya, D.; Hildebrandt, P.; Vierstra, R.D. Characterization of Two Thermostable Cyanobacterial Phytochromes Reveals Global Movements in the Chromophore-Binding Domain during Photoconversion. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 21251–21266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiontke, S.; Anders, K.; Hildebrandt, P.; Mailliet, J.; Sineshchekov, V.A.; Essen, L.-O.; Hughes, J.; von Stetten, D. Spectroscopic and Photochemical Characterization of the Red-Light Sensitive Photosensory Module of Cph2 from Synechocystis PCC 6803. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010, 87, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain-Hartung, M.; Rockwell, N.C.; Lagarias, J.C. Natural Diversity Provides a Broad Spectrum of Cyanobacteriochrome-Based Diguanylate Cyclases. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Martin, S.S.; Lagarias, J.C. Red/Green Cyanobacteriochromes: Sensors of Color and Power. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 9667–9677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narikawa, R.; Ishizuka, T.; Muraki, N.; Shiba, T.; Kurisu, G.; Ikeuchi, M. Structures of Cyanobacteriochromes from Phototaxis Regulators AnPixJ and TePixJ Reveal General and Specific Photoconversion Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez Escobar, F.; Utesch, T.; Narikawa, R.; Ikeuchi, M.; Mroginski, M.A.; Gärtner, W.; Hildebrandt, P. Photoconversion Mechanism of the Second GAF Domain of Cyanobacteriochrome AnPixJ and the Cofactor Structure of Its Green-Absorbing State. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 4871–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Velazquez Escobar, F.; Xu, X.L.; Narikawa, R.; Ikeuchi, M.; Siebert, F.; Gärtner, W.; Matysik, J.; Hildebrandt, P. A Red/Green Cyanobacteriochrome Sustains Its Color Despite a Change in the Bilin Chromophorés Protonation State. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5839–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B. Model Systems for Understanding Absorption Tuning by Opsin Proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Martin, S.S.; Gulevich, A.G.; Lagarias, J.C. Conserved Phenylalanine Residues Are Required for Blue-Shifting of Cyanobacteriochrome Photoproducts. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3118–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Martin, S.S.; Lim, S.; Lagarias, J.C.; Ames, J.B. Characterization of Red/Green Cyanobacteriochrome NpR6012g4 by Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: A Protonated Bilin Ring System in Both Photostates. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2581–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Port, A.; Wiebeler, C.; Zhao, K.H.; Schapiro, I.; Gärtner, W. Structural Elements Regulating the Photochromicity in a Cyanobacteriochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 2432–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrke, D.; Battocchio, G.; Wilkening, S.; Blain-Hartung, M.; Baumann, T.; Schmitt, F.J.; Friedrich, T.; Mroginski, M.A.; Hildebrandt, P. Red, Orange, Green: Light- And Temperature-Dependent Color Tuning in a Cyanobacteriochrome. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrke, D.; Oppelt, K.T.; Heckmeier, P.J.; Fernández-Terán, R.; Hamm, P. Nanosecond Protein Dynamics in a Red/Green Cyanobacteriochrome Revealed by Transient IR Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 245101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulijasz, A.T.; Cornilescu, G.; von Stetten, D.; Cornilescu, C.; Escobar, F.V.; Zhang, J.; Stankey, R.J.; Rivera, M.; Hildebrandt, P.; Vierstra, R.D. Cyanochromes Are Blue/Green Light Photoreversible Photoreceptors Defined by a Stable Double Cysteine Linkage to a Phycoviolobilin-Type Chromophore. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29757–29772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgie, E.S.; Walker, J.M.; Phillips, G.N.; Vierstra, R.D. A Photo-Labile Thioether Linkage to Phycoviolobilin Provides the Foundation for the Blue/Green Photocycles in DXCF-Cyanobacteriochromes. Structure 2013, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kikukawa, T.; Miyoshi, R.; Kajimoto, K.; Yonekawa, C.; Fujisawa, T.; Unno, M.; Eki, T.; Hirose, Y. Protochromic Absorption Changes in the Two-Cysteine Photocycle of a Blue/Orange Cyanobacteriochrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18909–18922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoegawa, S.; Miyoshi, R.; Watanabe, K.; Hirose, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Ikeuchi, M.; Unno, M. Identification of the Deprotonated Pyrrole Nitrogen of the Bilin-Based Photoreceptor by Raman Spectroscopy with an Advanced Computational Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 3242–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, Y.; Miyoshi, R.; Kamo, T.; Fujisawa, T.; Nagae, T.; Mishima, M.; Eki, T.; Hirose, Y.; Unno, M. Raman Spectroscopy of an Atypical C15- E, Syn Bilin Chromophore in Cyanobacteriochrome RcaE. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Royant, A.; Lin, M.Z.; Aguilera, T.A.; Lev-Ram, V.; Steinbach, P.A.; Tsien, R.Y. Mammalian Expression of Infrared Fluorescent Proteins Engineered from a Bacterial Phytochrome. Science (80-. ). 2009, 324, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonov, G.S.; Piatkevich, K.D.; Ting, L.M.; Zhang, J.; Kim, K.; Verkhusha, V. V. Bright and Stable Near-Infrared Fluorescent Protein for in Vivo Imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).