Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

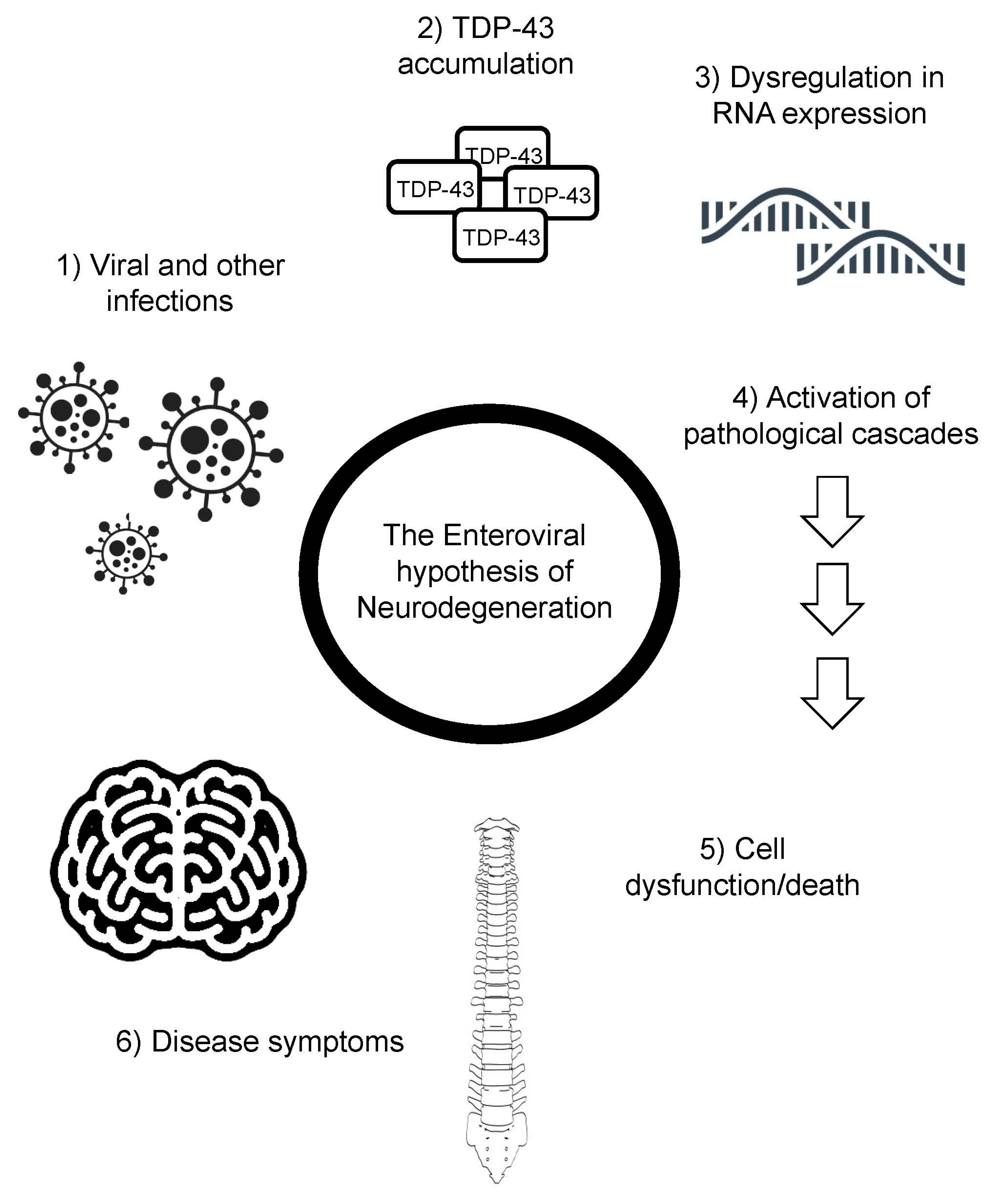

Introduction

TDP-43 hyperphosphorylation in ALS

Part I: Enteroviruses in the etiology of motor neuron disease

Part IV: Unresolved questions

Part V: Concluding remarks: A call to Arms:

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arthur, K.C.; Calvo, A.; Price, T.R.; Geiger, J.T.; Chiò, A.; Traynor, B.J. Projected increase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from 2015 to 2040. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue YC, Feuer R, Cashman N, Luo H. Enteroviral Infection: The Forgotten Link to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis? Front Mol Neurosci [Internet]. Frontiers Media SA; 2018 [cited 2023 Apr 25];11. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5857577/.

- Vandenberghe, N.; Leveque, N.; Corcia, P.; Brunaud-Danel, V.; Salort-Campana, E.; Besson, G.; Tranchant, C.; Clavelou, P.; Beaulieux, F.; Ecochard, R.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid detection of enterovirus genome in ALS: A study of 242 patients and 354 controls. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 2010 11, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks DN, Relman DA. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch’s postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. Clin Microbiol Rev; 1996 [cited 2023 Apr 17];9:18–33. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8665474/.

- Sreedharan, J.; Blair, I.P.; Tripathi, V.B.; Hu, X.; Vance, C.; Rogelj, B.; Ackerley, S.; Durnall, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Buratti, E.; et al. TDP-43 Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2008, 319, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Truax, A.C.; Micsenyi, M.C.; Chou, T.T.; Bruce, J.; Schuck, T.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2006, 314, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Sanelli, T.; Dib, S.; Sheps, D.; Findlater, J.; Bilbao, J.; Keith, J.; Zinman, L.; Rogaeva, E.; Robertson, J. RNA targets of TDP-43 identified by UV-CLIP are deregulated in ALS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2011, 47, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, et al. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci [Internet]. Nat Neurosci; 2011 [cited 2023 Apr 17];14:452–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21358640/.

- Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci [Internet]. Nat Neurosci; 2011 [cited 2023 Apr 17];14:459–68. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21358643/.

- Liu, E.A.; Mori, E.; Hamasaki, F.; Lieberman, A.P. TDP-43 proteinopathy occurs independently of autophagic substrate accumulation and underlies nuclear defects in Niemann-Pick C disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2021, 47, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, A.; Zampieri, S.; Canterini, S.; Newell, K.L.; Stuani, C.; Murrell, J.R.; Ghetti, B.; Fiorenza, M.T.; Bembi, B.; Buratti, E. Altered localization and functionality of TAR DNA Binding Protein 43 (TDP-43) in niemann- pick disease type C. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.H.; Wu, F.; Harrich, D.; García-Martínez, L.F.; Gaynor, R.B. Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 3584–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rodríguez, R.; Pérez-Yanes, S.; Montelongo, R.; Lorenzo-Salazar, J.M.; Estévez-Herrera, J.; García-Luis, J.; Íñigo-Campos, A.; Rubio-Rodríguez, L.A.; Muñoz-Barrera, A.; Trujillo-González, R.; et al. Transactive Response DNA-Binding Protein (TARDBP/TDP-43) Regulates Cell Permissivity to HIV-1 Infection by Acting on HDAC6. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, L.; Chatterjee, N.; Borges-Monroy, R.; Hearn, S.; Liao, W.-W.; Morrill, K.; Prazak, L.; Rozhkov, N.; Theodorou, D.; Hammell, M.; et al. Retrotransposon activation contributes to neurodegeneration in a Drosophila TDP-43 model of ALS. PLOS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, P.; Sidle, K.C.L.; Hardy, J. Review: Prion-like mechanisms of transactive response DNA binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2015, 41, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang WC, Lee MH, Chen TC, Huang JR. Interactions between the Intrinsically Disordered Regions of hnRNP-A2 and TDP-43 Accelerate TDP-43′s Conformational Transition. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2020 [cited 2023 Apr 22];21:1–11. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7460674/.

- Monette, A.; Mouland, A.J. Zinc and Copper Ions Differentially Regulate Prion-Like Phase Separation Dynamics of Pan-Virus Nucleocapsid Biomolecular Condensates. Viruses 2020, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.F.; Shorter, J. RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in health and disease. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitler, A.D.; Shorter, J. RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in ALS and FTLD-U. Prion 2011, 5, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Ding X, Akram N, Xue S, Luo SZ. Fused in Sarcoma: Properties, Self-Assembly and Correlation with Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, Vol 24, Page 1622 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 17];24:1622. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/24/8/1622/htm.

- Bellmann J, Monette A, Tripathy V, Sójka A, Abo-Rady M, Janosh A, et al. Viral Infections Exacerbate FUS-ALS Phenotypes in iPSC-Derived Spinal Neurons in a Virus Species-Specific Manner. Front Cell Neurosci. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2019;13:480.

- Watts JC, Prusiner SB. β-Amyloid Prions and the Pathobiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2018 [cited 2023 Apr 25];8. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5554751/.

- Bible, J.M.; Pantelidis, P.; Chan, P.K.S.; Tong, C.Y.W. Genetic evolution of enterovirus 71: epidemiological and pathological implications. Rev. Med Virol. 2007, 17, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds P, Gorbalenya AE, Harvala H, Hovi T, Knowles NJ, Lindberg AM, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses. Arch Virol [Internet]. Arch Virol; 2020 [cited 2023 Apr 17];165:793–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31980941/.

- Kitamura, N.; Semler, B.L.; Rothberg, P.G.; Larsen, G.R.; Adler, C.J.; Dorner, A.J.; Emini, E.A.; Hanecak, R.; Lee, J.J.; van der Werf, S.; et al. Primary structure, gene organization and polypeptide expression of poliovirus RNA. Nature 1981, 291, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells AI, Coyne CB. Enteroviruses: A Gut-Wrenching Game of Entry, Detection, and Evasion. Viruses [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 19];11. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6563291/.

- Sejvar JJ, Lopez AS, Cortese MM, Leshem E, Pastula DM, Miller L, et al. Acute Flaccid Myelitis in the United States, August-December 2014: Results of Nationwide Surveillance. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. Clin Infect Dis; 2016 [cited 2023 Apr 19];63:737–45. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27318332/. 20 December.

- Messacar, K.; Asturias, E.J.; Hixon, A.M.; Van Leer-Buter, C.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Tyler, K.L.; Abzug, M.J.; Dominguez, S.R. Enterovirus D68 and acute flaccid myelitis—Evaluating the evidence for causality. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e239–e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodall, C.J.; Riding, M.H.; I Graham, D.; Clements, G.B. Sequences specific for enterovirus detected in spinal cord from patients with motor neurone disease. BMJ 1994, 308, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, K.K.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Chan, Y.F.; Bible, J.M.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Tong, C.Y.W.; Takebe, Y.; Pybus, O.G. Evolutionary Genetics of Human Enterovirus 71: Origin, Population Dynamics, Natural Selection, and Seasonal Periodicity of the VP1 Gene. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3339–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn PC. An overview of the evolution of enterovirus 71 and its clinical and public health significance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. No longer published by Elsevier; 2002;26:91–107.

- Domingo E. Molecular basis of genetic variation of viruses: error-prone replication. Virus as Populations [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020 [cited 2023 Apr 22];35. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7153327/.

- Bharat, T.A.; Noda, T.; Riches, J.D.; Kraehling, V.; Kolesnikova, L.; Becker, S.; Kawaoka, Y.; Briggs, J.A. Structural dissection of Ebola virus and its assembly determinants using cryo-electron tomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4275–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

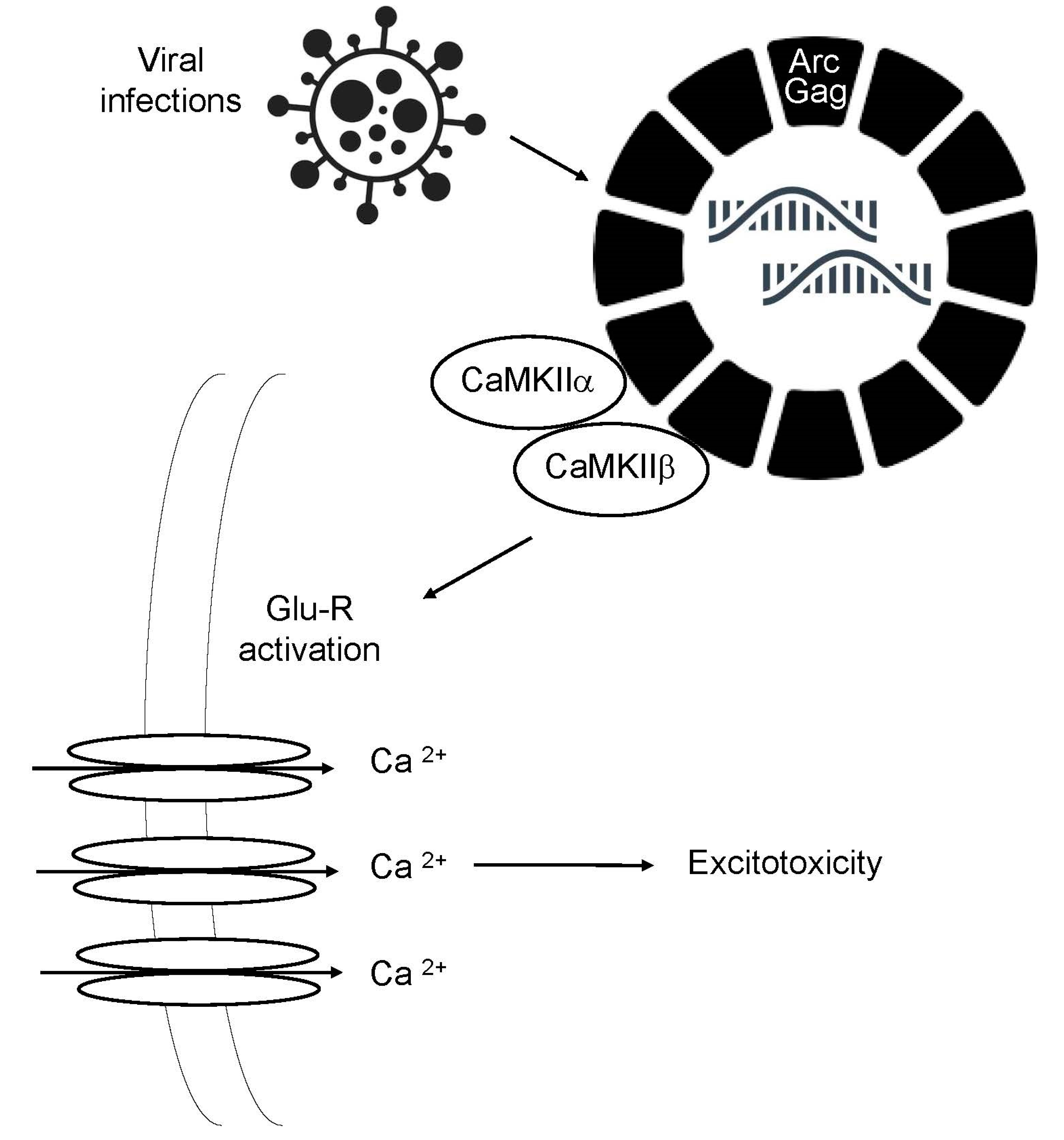

- Pastuzyn, E.D.; Day, C.E.; Kearns, R.B.; Kyrke-Smith, M.; Taibi, A.V.; McCormick, J.; Yoder, N.; Belnap, D.M.; Erlendsson, S.; Morado, D.R.; et al. The Neuronal Gene Arc Encodes a Repurposed Retrotransposon Gag Protein that Mediates Intercellular RNA Transfer. Cell 2018, 172, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantak, M.P.; Einstein, J.; Kearns, R.B.; Shepherd, J.D. Intercellular Communication in the Nervous System Goes Viral. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Wang, P.; Qin, C.-F.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, G.-C.; Yang, J.; Sun, X.; Wu, W.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Human Enterovirus Nonstructural Protein 2CATPase Functions as Both an RNA Helicase and ATP-Independent RNA Chaperone. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung HW, Foo G, VanDongen A. Arc Regulates Transcription of Genes for Plasticity, Excitability and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 17];10. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9405677/.

- Wu, J.; Petralia, R.S.; Kurushima, H.; Patel, H.; Jung, M.-Y.; Volk, L.; Chowdhury, S.; Shepherd, J.D.; Dehoff, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Arc/Arg3.1 Regulates an Endosomal Pathway Essential for Activity-Dependent β-Amyloid Generation. Cell 2011, 147, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chuang, Y.-A.; Na, Y.; Ye, Z.; Yang, L.; Lin, R.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J.; Qiu, J.; Savonenko, A.; et al. Arc Oligomerization Is Regulated by CaMKII Phosphorylation of the GAG Domain: An Essential Mechanism for Plasticity and Memory Formation. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haolong, C.; Du, N.; Hongchao, T.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Hua, Z.; Wenliang, Z.; Lei, S.; Po, T. Enterovirus 71 VP1 Activates Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II and Results in the Rearrangement of Vimentin in Human Astrocyte Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lovell, S.; Tiew, K.-C.; Mandadapu, S.R.; Alliston, K.R.; Battaile, K.P.; Groutas, W.C.; Chang, K.-O. Broad-Spectrum Antivirals against 3C or 3C-Like Proteases of Picornaviruses, Noroviruses, and Coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11754–11762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahic Z, Buratti E, Cappelli S. Reviewing the Potential Links between Viral Infections and TDP-43 Proteinopathies. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 17];24. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9867397/.

- Fung, G.; Shi, J.; Deng, H.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Hong, A.; Zhang, J.; Jia, W.; Luo, H. Cytoplasmic translocation, aggregation, and cleavage of TDP-43 by enteroviral proteases modulate viral pathogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 2087–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathinayake PS, Hsu ACY, Wark PAB. Innate Immunity and Immune Evasion by Enterovirus 71. Viruses [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2015 [cited 2023 Apr 22];7:6613. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4690884/.

- Yang J, Li Y, Wang S, Li H, Zhang L, Zhang H, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease induces neurotoxic TDP-43 cleavage and aggregates. Signal Transduct Target Ther [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 22];8. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9998009/.

- Gumna, J.; Purzycka, K.J.; Ahn, H.W.; Garfinkel, D.J.; Pachulska-Wieczorek, K. Retroviral-like determinants and functions required for dimerization of Ty1 retrotransposon RNA. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.A.; Freed, E.O.; Li, G.; Theys, K.; Verheyen, J.; Pineda-Peña, A.-C.; Khouri, R.; Piampongsant, S.; Eusébio, M.; Ramon, J.; et al. HIV Type 1 Gag as a Target for Antiviral Therapy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2012, 28, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Rein, A. In Vitro Assembly Properties of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag Protein Lacking the p6 Domain. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 2270–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Z.; Jayappa, K.D.; Wang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Yao, X. Contribution of Host Nucleoporin 62 in HIV-1 Integrase Chromatin Association and Viral DNA Integration. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10544–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingemann, M.; McCarty, T.; Liu, X.; Buchholz, U.J.; Surman, S.; Martin, S.E.; Collins, P.L.; Munir, S. The alpha-1 subunit of the Na+,K+-ATPase (ATP1A1) is required for macropinocytic entry of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in human respiratory epithelial cells. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, C.; Wang, S.J.H.; Yoo, S.H.; Harden, N. Adducin at the Neuromuscular Junction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Hanging on for Dear Life. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo G, Barowski J, Ravits J, Siddique T, Lingrel JB, Robertson J, et al. An α2-Na/K ATPase/α-adducin complex in astrocytes triggers non–cell autonomous neurodegeneration. Nature Neuroscience 2014 17:12 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2014 [cited 2023 Apr 17];17:1710–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.3853.

- Mann, C.N.; Devi, S.S.; Kersting, C.T.; Bleem, A.V.; Karch, C.M.; Holtzman, D.M.; Gallardo, G. Astrocytic α2-Na + /K + ATPase inhibition suppresses astrocyte reactivity and reduces neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabm4107–eabm4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.F.; Kurian, D.; Agarwal, S.; Toovey, L.; Hunt, L.; Kirby, L.; Pinheiro, T.J.T.; Banner, S.J.; Gill, A.C. Na+/K+-ATPase Is Present in Scrapie-Associated Fibrils, Modulates PrP Misfolding In Vitro and Links PrP Function and Dysfunction. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e26813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo G, Barowski J, Ravits J, Siddique T, Lingrel JB, Robertson J, et al. An α2-Na/K ATPase/α-adducin complex in astrocytes triggers non–cell autonomous neurodegeneration. Nature Neuroscience 2014 17:12 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2014 [cited 2023 Apr 25];17:1710–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.3853.

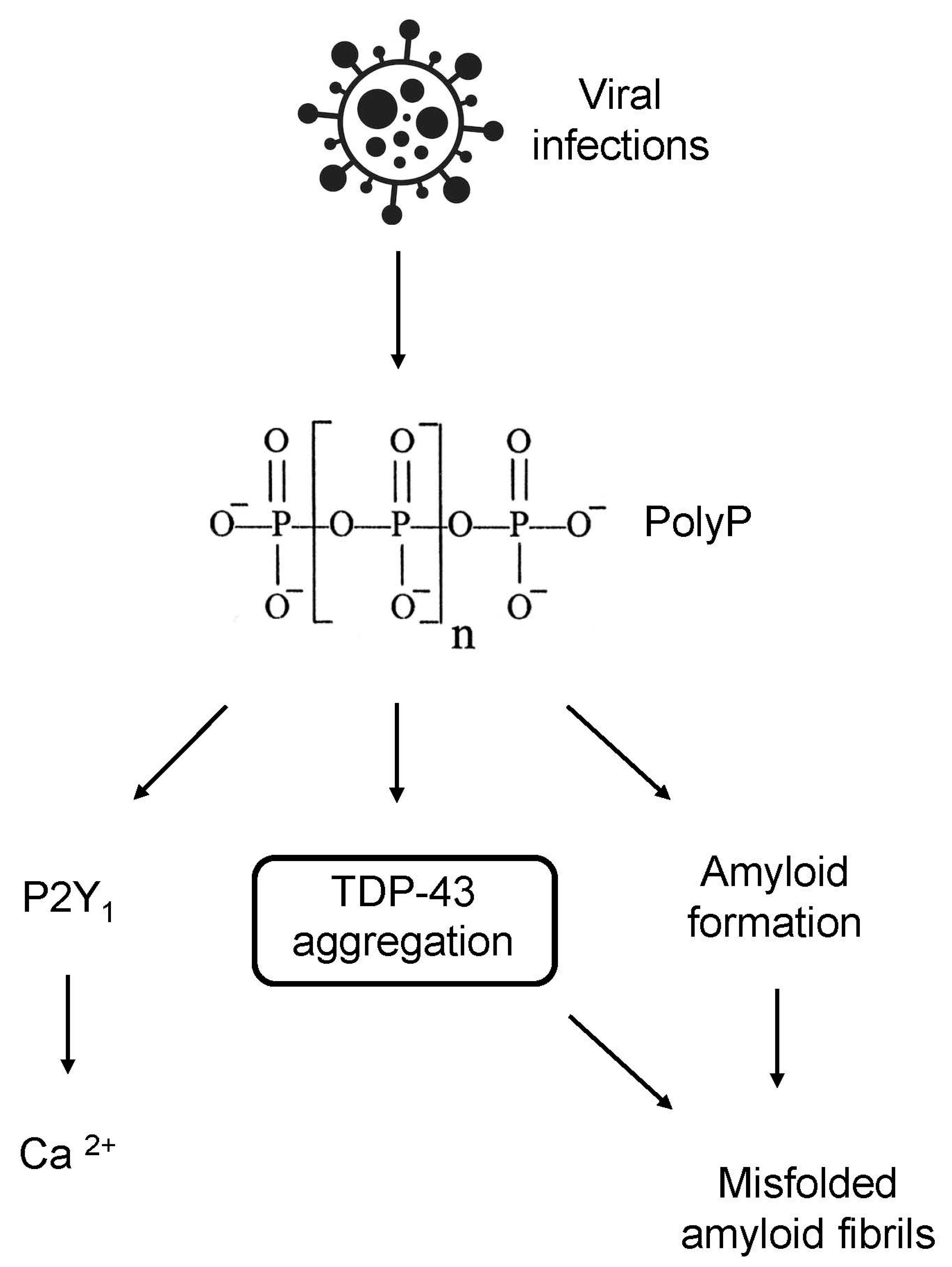

- Li, L.; Rao, N.N.; Kornberg, A. Inorganic polyphosphate essential for lytic growth of phages P1 and fd. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 1794–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempart J, Jakob U. Role of Polyphosphate in Amyloidogenic Processes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 19];11. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6496346/.

- Johnson, R.S.; Strausbauch, M.; McCloud, C. An NTP-driven mechanism for the nucleotide addition cycle of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase during transcription. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0273746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiolino, M.; O'Neill, N.; Lariccia, V.; Amoroso, S.; Sylantyev, S.; Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Inorganic Polyphosphate Regulates AMPA and NMDA Receptors and Protects Against Glutamate Excitotoxicity via Activation of P2Y Receptors. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 6038–6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysanthopoulou A, Kambas K, Stakos D, Mitroulis I, Mitsios A, Vidali V, et al. Interferon lambda1/IL-29 and inorganic polyphosphate are novel regulators of neutrophil-driven thromboinflammation. J Pathol [Internet]. J Pathol; 2017 [cited 2023 Apr 25];243:111–22. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28678391/.

- Odessky L, Rosenblatt P, Sands IJ, Schiff I, Dubin FM, Spielsinger D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid inorganic phosphorus in acute poliomyelitis; study of one hundred four patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry [Internet]. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry; 1955 [cited 2023 Apr 17];73:255–66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14349427/.

- Arredondo, C.; Cefaliello, C.; Dyrda, A.; Jury, N.; Martinez, P.; Díaz, I.; Amaro, A.; Tran, H.; Morales, D.; Pertusa, M.; et al. Excessive release of inorganic polyphosphate by ALS/FTD astrocytes causes non-cell-autonomous toxicity to motoneurons. Neuron 2022, 110, 1656–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, S.P.; Lempart, J.; Merens, H.E.; Murphy, J.; Huettemann, P.; Jakob, U.; Rhoades, E. Polyphosphate Initiates Tau Aggregation through Intra- and Intermolecular Scaffolding. Biophys. J. 2019, 117, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.S.; Boutej, H.; Soucy, G.; Bareil, C.; Kumar, S.; Picher-Martel, V.; Dupré, N.; Kriz, J.; Julien, J.-P. Transmission of ALS pathogenesis by the cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britson, K.A.; Ling, J.P.; Braunstein, K.E.; Montagne, J.M.; Kastenschmidt, J.M.; Wilson, A.; Ikenaga, C.; Tsao, W.; Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Russell, K.A.; et al. Loss of TDP-43 function and rimmed vacuoles persist after T cell depletion in a xenograft model of sporadic inclusion body myositis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabi9196–eabi9196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, A.; Kastner, S.; Chatzikonstantinou, E.; Pitzer, C.; Plaas, C.; Kirsch, F.; Wafzig, O.; Krã¼Ger, C.; Spoelgen, R.; De Aguilar, J.-L.G.; et al. Gene expression changes in spinal motoneurons of the SOD1G93A transgenic model for ALS after treatment with G-CSF. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.P.; Hall, B.; Castelli, L.M.; Francis, L.; Woof, R.; Siskos, A.P.; Kouloura, E.; Gray, E.; Thompson, A.G.; Talbot, K.; et al. Astrocyte adenosine deaminase loss increases motor neuron toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2019, 142, 586–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briese, T.; Kapoor, A.; Mishra, N.; Jain, K.; Kumar, A.; Jabado, O.J.; Lipkin, W.I. Virome Capture Sequencing Enables Sensitive Viral Diagnosis and Comprehensive Virome Analysis. mBio 2015, 6, e01491–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).