1. Introduction

Neuromuscular disorders (NMD), with a muscle weakness manifestation, are grouped under lower motor neuron syndrome (LMN). Disorders in the clinics classically depend on the level affected - motor neuron (neuronopathies), nerve root/plexus (radiculo-plexus neuropathies), individual peripheral nerves (focal/multi-focal/diffuse polyneuropathies), neuromuscular junction (NMJ disorders), and muscle (myopathies). This present review starts with a clinical approach in NMD, and thenceforth, focus on myopathies and those that are treatable.

2.1. A. Clues in NMD History Taking

Like other neurologic disciplines, some special aspects of history taking need to be remembered. The onset of which symptoms is crucial (e.g. acute onset, symmetry of limb weakness), as are the appearance of new symptoms over time, including the precipitating factors or which activities have been curtailed thereafter. A chronic progressive course or one which is diurnal and fatigue-related, and exercise intolerance are important considerations. Past or co-morbid illnesses, with a detailed medication list, as are personal and baseline functioning, should be elicited. A caveat is that patients may have been suffering from NMD for a long time that their disabilities induce negative or difficult attitudes toward the disease. Deriving 3-generation family history of NMD, carved in a genogram is ideal, so as to ascertain autosomal dominance, yet not to waylay consanguinity in reference to autosomal recessive inheritance and certainly, the x-linked disorders. Challenges in family history ascertainment include: early loss of family members, single child, adoption, intra-familial variations and disease formes frustes that may occur.

2.2. B. Clues in NMD General Examination

The co-existence of cardiomyopathies and arrhythmias point to inherited myopathies such as dystrophinopathies, limb-girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMD), myotonic dystrophies and Andersen–Tawil syndrome. Metabolic glycogen and lipid storage myopathies may present with hepatosplenomegaly. Inherited neuropathies may present with skeletal deformities like pes cavus and kyphoscoliosis. Deafness, retinitis pigmentosa and short stature allude to mitochondriopathies. Joint laxity with or without contracture indicate collagenopathies like Ullrich disease. Skin Rashes and ‘mechanic’s hands’ point to immune-mediated disorders, like Dermatomyositis, while skin pigmentation points to POEMS (Polyneuropathy, Organomegaly, Endocrinopathy/edema, M-proteinemia and Skin changes), adrenal failure or B12 deficiency. Palm and sole hyperkeratosis are noted in toxic neuropathies, (e.g., arsenic toxicity, and their nails show Mee’s lines). Autonomic neuropathy is considered in cases with hair loss of distal limbs, as are cold feet and hands.

2.3. C. Clues in NMD Neurologic Examination

Clinical clues include asking the patient to stand erect and walk normally to observe for ataxia (e.g. sensory ataxia in Romberg’s test), to walk on heels and toes (for distal-dominant weakness), to rise from a chair or ground, and lift arms overhead (for proximal-dominant weakness); Weakness of the knees results in hyperextension of the knee, the genu recurvatum and high steppage gait points to foot drop (whether symmetric or asymmetric); Exaggerated lordosis and protuberant abdomen point to truncal muscle weakness and waddle to gluteal weakness. Scapular Winging from atrophy can be elicited by asking patient to outstretch both upper limbs and rest palms on a wall. Facial weakness (unilateral/bifacial, by way of drooping/lagging in facial expression and mimic movements), jaw bite and deviation, tongue at rest (for atrophy and fasciculations) and protrusion (for deviation). Specific eye movement impairment (ptosis/weak eye movements [EOM]), including eye closure observed in sleep) are helpful clues. There is clinical benefit observing for muscle hypertrophy (best seen in gastrocnemius, hip, shoulder and elbow movers), for preferential muscle group/myotomal atrophy, and for abnormal movements like fasciculations (brief scattered twitches at irregular intervals; usually seen in chest, shoulder, upper back, proximal limbs and tongue), myokymia (muscle quivering, undulating and slower contraction of muscle strips), and rippling muscles (provoked by mechanical stimuli and stretch). Neck muscle weakness (especially in flexion), be useful test, as will the classic manual muscle examination hinged on specific proximal and distal joint movers. Deep tendon Reflexes/DTRs, using a reflex hammer, be important not only for reflex symmetry but also to weed out upper motor neuron [UMN] signs. In addition to grip myotonia, a reflex hammer is also used to elicit percussion myotonia by tapping the thenar eminence and find delayed relaxation. Basic sensory examination will assist in eliminating neuropathic disorders.

Table 1 presents an algorithm that can serve as a guide in the localization of the lesion when confronted with a patient with muscle weakness. Foremost clinical approach is to ensure that weakness is not attributable to central or associated long tracts (i.e., with UMN signs) like spasticity; or with bradykinesia and rigidity (i.e., in Parkinsonism); or with cerebellar ataxia. Despite astute observations and work-up, if the clinical manifestations cannot be accounted to the aforementioned levels, then the case could be a functional neurological disorder (FND).

The

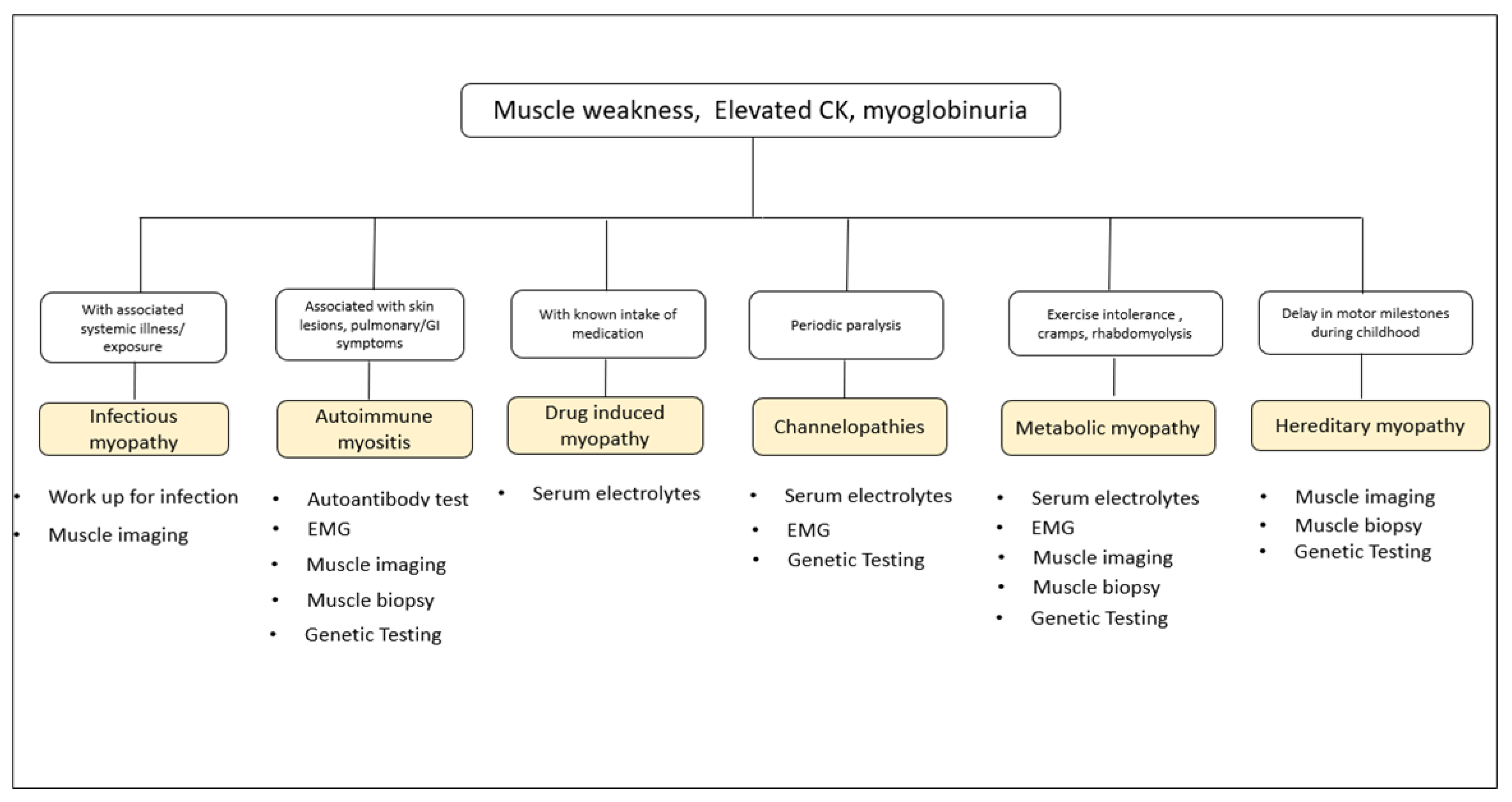

Myopathies characteristically present with symmetric, proximal-dominant skeletal muscle weakness, sometimes accompanied by fatigue and pain. However, there are distal myopathies which are of genetic causes. The acquired and acute myopathies are given importance because treatment is readily available however, some inherited myopathies can be treated as well. These treatable myopathies can be grouped by etiology into infectious myopathies, granulomatous myopathies, autoimmune myopathies, metabolic myopathies, skeletal channel myopathies, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Total creatine kinase (CK) elevation beyond 1000U/L is a good biomarker for myopathies, but may not necessarily be high in a chronic state or in some disorders. Although a myopathic electrodiagnosis may be established by showing electromyographic (EMG) brief, low amplitude polyphasic potentials, early recruitment and whether or not coupled with irritative potentials, this diagnostic test specificity is low. Nowadays, muscle imaging by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful tools in sorting myopathies. An algorithmic classification of treatable myopathies and recommended diagnostic work up is made in

Figure 1. Not to be missed treatable myopathies are periodic paralysis, rhabdomyolysis and those that occur in the intensive care.

2. Infectious Myositis

Myositis is characterized as inflammation of the muscle, and though the muscle is relatively resistant to infection, there are still a wide array of organisms that may cause disease including viruses, parasites, bacteria and fungi [

1]. The clinical course may be varied from acute, subacute or chronic and may be accompanied by other systemic manifestations like fever, rash and thrombosis. Aside from viral myositis, hematogenous spread and direct invasion like trauma, surgery, exposure to contaminated soil play important roles. Immunosuppression also increases susceptibility to some bacteria and fungal organisms. Focal muscle involvement is evident from these infections however may still spread to other areas if microbial load is overwhelming. For viral myositis, generalized muscle weakness and fatigue is more common and since the covid 19 pandemic there have been reports of acute and post-infectious muscle involvement [

2]. The diagnosis of myositis depends not only on the clinical picture and perhaps imaging but confirmation by serologic tests and cultures are vital. This should be the case because therapy is dependent on the underlying pathogen.

A. Viruses are a common cause of infectious myositis. The mechanisms involve direct cytopathic effect, formation of immune complexes, and immune dysregulation. Muscle damage on the other hand is mainly due to direct myotoxic effects. Due to the trophic property to immature muscle cells, the disease is more common in children. Viral myositis can lead to manifestations of myalgia, symmetric weakness, and may also be associated with rhabdomyolysis. Viral etiology is suspected when muscle weakness develops after an antecedent gastrointestinal or respiratory infection.

Viral myositis is mostly caused by influenza A, influenza B, Coxsackievirus, Epstein-Barr virus and presents with myalgia, fatigue and rhabdomyolysis. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been reports on myositis related to SARS-Cov-2 infection. Factors that may contribute to the weakness and fatigue includes prolonged hospitalization, malnutrition, disuse and hypoxemia [

1]. Direct muscle invasion with activation of an adaptive immune response with angiotensin-converting enzyme ACE2 receptor mediated viral entry induces myositis in COVID-19 patients [

3]. According to recent literature [

4], rhabdomyolysis has been reported in both adult and pediatric individuals infected with COVID 19. The pathogenesis involves myotoxic cytokines. Myositis from covid-19 vaccination has been reported as well. Muscle weakness and fatigue are also seen in 50-60% of patients six months after the initial infection [

3]. CK elevation with muscle weakness is present. Patients who are admitted to the intensive care unit with severe COVID-19 infection showed a 30% decrease in cross-sectional area of the rectus femoris, with a decreased thickness of the quadriceps muscle after 10 days. Physical therapy should be done to prevent further atrophy of muscles [

4]. Anti-Covid19 viral therapy (e.g. Ritonavir and Nirmatrelvir, in addition to previous Remdisivir and Molnupiravir) and vaccines are available to combat and prevent the illness, respectively. Keen management attention to respiratory (mainly), cardiac and neurologic complications should figure into the therapeutic regimen.

The endemic chronic retroviral infections like Human T-Lymphotrophic Virus, Type 1 (HTLV-1) have been reported to lead to myositis. From muscle biopsy specimens, HTLV-1 in CD4+ cells have been found but not in macrophages. This finding suggests that most of the HTLV-1-containing CD4+ cells are not macrophages but lymphocytes [

5].

Medications tried in HTLV-1 infections (myositis included) lack systematic studies and are an array of steroids, Interferon, Danazol, high dose Vitamin C, Azathioprine and anti-virals employed in Human Immunedeficiency Virus (HIV) infection (e.g. Lamivudine and Zidovudine [the latter drug causes mitochondrial toxicity leading to myopathy too]). HIV itself can take the form of myopathy, infiltrative lesions and rhabdomyolysis. HIV associated myositis has a good prognosis especially upon prompt recognition and treatment initiation.

B. Bacterial infections of the muscle are mostly caused by direct invasion from trauma spreading hematogenously. The most common cause of pyomyositis is due to Staphylococcus aureus infection [

6]. Presenting signs and symptoms include focal pain and tenderness of the affected muscle, fever and even abscess formation and if left untreated may lead to osteomyelitis, endocarditis and sepsis. It is also important to note that common findings in soft tissue infections like lymphadenitis and focal erythema are not seen in cases of pyomyositis. Most pyomyositis cases involve a single group of muscles however in 10-20% there is diffuse muscle involvement. Different S. aureus strains can secrete several exotoxins and those that cause toxic shock syndrome are due to T-cell activation and massive cytokine activation. Infections due to Group A B-hemolytic streptococcus are less common but more severe and may cause necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. It is an opportunistic organism common amongst diabetics and immunocompromised individuals. An early key finding is an increased amount of pain disproportionate to the observed lesion [

7]. Polymicrobial infections is also common in the setting of vascular insufficiency and penetrating wounds. Gram stain and aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be done immediately for directed antibiotic therapy. Penicillins, Cephalosporins, and Vancomycin with the addition of Gentamicin and Clindamycin should be started even without culture results. Where necessary, surgical drainage of pus should be performed alongside IV antibiotics.

C. Parasitic myositis should be suspected in patients with muscle aches, history of travel to endemic areas, and ingestion of undercooked meat. The most common cause of which include Taenia solium, Trichinella species and Toxoplasma gondii but other parasites may also encyst in the skeletal muscle tissue. Parasitic invasion of the muscle causes weakness, swelling and myalgia. A finding of eosinophilia and elevated CK, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are usual. Biopsy of an affected muscle, usually a swollen deltoid or gastrocnemius, will confirm the diagnosis but serologic tests are also available. Taenia solium or pork tapeworm is acquired from ingesting T. solium eggs from undercooked pork and may not only cause gastroenteritis but dissemination of larvae via the bloodstream may infect other organs including the muscle leading to Cysticercosis. It is also known to cause Neurocysticercosis once it reaches the central nervous system and is one of the most common causes of adult-onset seizures. It is said that there is muscle involvement in 75% of Neurocysticercosis patients. The lesions appear as small rounded calcifications in the muscle of the arm or thigh. Stool examination will reveal tapeworm eggs and confirmation can be made by serologic tests such as ELISA. Trichinella larvae on the other hand may cause chronic infections in the muscle. Trichinosis also occurs with ingestion of encysted larvae from undercooked boar, pork or dog meat. Muscle damage from this condition result from the parasite making a capsule inside the muscle, thereby eliciting a process of repeated regeneration, degeneration and necrosis. Serologic tests are done with anti-trichinella IgG antibodies. Protozoal Toxoplasmosis from T. gondii cysts can be ingested from food contaminated with oocysts from cat feces and may infect the muscles. Immunosuppressed persons are more vulnerable to this infection with low CD4 counts. IgG antibodies to T. gondii should also be requested. Treatment of the muscle involvement include specific medications (e.g. Praziquantel, Albendazole, Mebendazole for helminthic and Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine, Atovaquone for Protozoal infections), and where necessary, alongside surgical removal of the lesion may be done.

D. Fungal myositis is most often associated with immunocompromised patients. A single muscle or group of muscles are affected because of an abscess formation. The clinical presentation is similar to bacterial myopathies. A definitive diagnosis requires a histopathological examination, serology and culture. Management includes surgical debridement and systemic antifungal agents. Candida is the most common fungus that causes myositis. Risk factors include use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, immunosuppressive drugs, and severe neutropenia that manifests with diffuse muscle tenderness accompanied by rash and fever. On histologic examination, budding yeast and pseudohyphae can be seen. Cryptococcus myositis is uncommon and is found in diabetic and immunocompromised patients presenting with a disseminated cryptococcal disease. Histologic examination by using mucicarmine or Alcian blue stains would reveal typical intracytoplasmic yeasts with a mucopolysaccharide capsule [

6]. Histoplasmosis rarely causes myositis after inhalation of dimoprhic fungi post-dissemination to the lungs. Histologic examination will show ovoid yeast cells, which can be detected using Gomori-methenamine or Grocot silver stains. Coccidioidomycosis is also a rare cause of myositis and manifestations include rash, arthropathy, and severe myositis. Diagnostic examination with histopathology reveal spherules filled with endospores. Therapeutic anti-fungal regimens include Amphotericin B and Triazoles (Fluconazole, Itraconazole, Voriconazole, Ravuconazole) in parenteral and/or oral forms. The Echinocandins may be used such as Caspofungin, Micafungin, as are the Antimetabolites like Flucytosine.

3. Autoimmune myositis

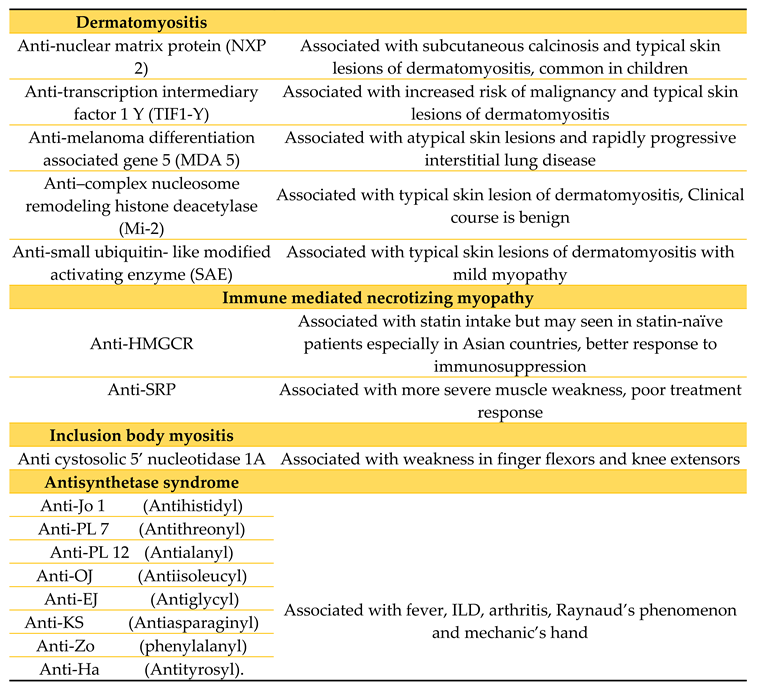

Autoimmune myositis is probably considered the largest and the most heterogenous group of treatable myopathies. Recent classification relies not only upon clinical and pathological data but also use of immunologic markers. To date, this group of myopathies are subdivided into either dermatomyositis, inclusion body myositis, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy and antisynthetase syndrome (see

Table 2). The clinical picture of proximal muscle weakness such as climbing up stairs or raising both arms associated with dermatologic and pulmonary manifestations are not unusual. However, in inclusion body myositis, distal muscles are more affected, asymmetric at that. Although important pathologic information is obtained from muscle biopsy, testing for autoantibodies (i.e. myositis-specific and myositis-associated antibodies) has come into play to differentiate some of these diseases.

A. Dermatomyositis may be seen in children or adults and is characterized by a subacute insidious proximal muscle weakness and cutaneous manifestations such as periorbital edema, heliotrope rash, Gottron’s sign, V-sign and Shawl sign. Recent clinicopathologic subtypes include Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) wherein classic dermatomyositis skin lesion is present but without muscle involvement, Dermatomyositis sine dermatitis wherein there is clinical and pathologic evidence of dermatomyositis however without any skin lesions and Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) in those less than 18 years of age [

9]. It is believed that myxovirus resistance protein (MxA), on immunohistochemical stain, is a highly specific and sensitive marker for dermatomyositis. MRI of the muscle will show fascial edema [

10]. Perifascicular atrophy is shown on muscle biopsy as the key histopathological feature of dermatomyositis. While this feature is highly specific, the sensitivity remains low at roughly 25-50% [

11]. The cellular infiltrate is perivascular, typically consisting of macrophages, B cells, CD4 cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Total CK levels are commonly elevated, and patients may also have various circulating antibodies, each with their own implications. Anti-Mi2, anti-SAE, anti-MDA5, anti-TIF1, and anti-NXP2 are likely specific for dermatomyositis [

12]. The prognosis of patients with dermatomyositis is overall good, with the literature claiming a 70%-93% survival rate at 5 years. However, the rate decreases in the presence of poor prognostic features [

10].

B. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) is a type of myositis included in the newest classification schemes for the inflammatory myopathies. It is often distinguished by the following features: relatively severe proximal weakness, myofiber necrosis with minimal inflammatory cell infiltrate on muscle biopsy, and infrequent extra-muscular involvement. IMNM is a diverse group in itself, and comprised of Anti-SRP myopathy, anti-HMGCR myopathy, and autoantibody-negative IMNM. According to a study [

13], there is an increase in the incidence of IMNM associated with statin use. In the study, most of the patients with IMNM seen in 2012-2014 were treated with statins and all but one had anti-HMGCR antibodies, which corroborates the likely role of statins in the pathogenesis. The age at which it is prevalent typically ranges from 30 to 70 yeras, but the pediatric population is not an exception. The pathogenesis of IMNM is likely related to an immune response possibly triggered by drug therapy (statins), viral infections, or cancer. The pathophysiological mechanisms are still unclear, but a specific genetic background has been identified (HLA-DRB1*11:01 allele in adult patients with anti-HMGCR autoantibodies) and autoantibody production is a major feature of the disease, particularly anti-SRP and anti-HMGCR [

14]. The main presentation of IMNM is subacute severe symmetrical proximal myopathy with a markedly elevated CK level. Clinically, this would manifest as slowly progressive proximal muscle weakness leading to difficulty in moving from a sitting position, climbing stairs, or lifting objects. There is also possible involvement of the neck flexor, pharyngeal, and respiratory muscles. Other manifestations include fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia and dyspnea. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) and cardiac involvement have also been reported (especially in those with anti-SRP antibody). Treatment is aimed at the underlying cause, such as statin withdrawal, or co-morbid malignancy. There is good response to multiple-agent, long-term immunosuppressive therapies starting at high dose corticosteroids. It is said that IMNM is the most severe idiopathic inflammatory myopathy when it comes to muscle damage, and frequent relapses, to chronicity could be expected [

15].

C. Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is a slowly progressive muscle disease affecting older patients aged 45-50 years old and above and is more common in men. It presents with asymmetric muscle weakness affecting the distal muscles more than the proximal ones. The knee extensors and long finger flexors are usually involved. Atrophy of the muscles is also present early on in the disease. Rimmed vacuoles are usually seen in muscle biopsy specimens however this finding is not specific for this disease but along with TDP-43, p62 and valosin containing protein (VCP) positivity, indicates ongoing degeneration. There is usually lymphocytic infiltration surrounding non-necrotic muscle fibers. IBM may also present with facial weakness and dysphagia may occasionally occur. IBM is considered to be an autoimmune and degenerative disease. The HLA locus is said to be the strongest risk alleles in the development of IBM. Its locus contains genes that encode MHC class I and II. The presence of endomysial infiltration with plasma cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes as well as MHC I expressing fibers indicate an autoimmune mechanism. A highly diagnostic biomarker for this myopathy is when antibodies that are targeting cN-1A or cytosolic 5’-nucleotidase 1A are detected in the blood [

9,

11]. Genetics investigations are well on their way to better understand the disease pathomechanism and possible new potential therapies. Some studies show that mitochondrial aging in muscle is faster in those with sporadic IBM, and this is due to the large mtDNA deletions and duplications in patients compared to controls. A study found that TOMM40 or very long poly-T repeat allele of the mitochondrial protein translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 intronic polymorphism had a disease onset much later in life [

16].

D. Antisynthetase syndrome (ASS) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory myopathy mainly distinguished by myositis, generally symmetrical arthritis and ILD in association with serum autoantibodies to aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases (anti-ARS). It is associated with highly variable features, including arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, heliotropic rash, distal esophageal dysmotility and mechanic's hands. ASS is more frequent in females, with a female to male ratio approximately 7:3 and a mean age of 48±15 years at disease onset. It has a prevalence estimate of 1/25,000-33,000 worldwide, provided by the premise that about a quarter of all idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients may have ASS [

17]. Currently, it is thought that the pathogenesis starts with a genetic predisposition, then with the lung involvement triggered by environmental factors as tobacco exposure, airborne contaminants, and infections [

18]. The non-specific tissue damage activates the innate immune system that leads to the release of immunogenic neo-antigens. There would be activation of the adaptive immune system with the production of anti-ARS antibodies, and the spread of the immune response to targeted tissues such as the muscle, joint, skin. Clinically, the hallmarks of ASS are myositis, arthritis and ILD. At the start of the disease, respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, dysphagia) are found in 40-60% of patients, which may be acute or progressive. Some patients develop clinically overt myositis while others have hypomyopathic or even amyopathic forms. At onset, 20-70% of patients have muscle weakness of the proximal and axial muscles, and many have myalgia and muscle stiffness, similar to the milder presentations of other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. ASS is a chronic disease which requires long-term treatment, with a guarded prognosis [

19].

Clinical experience taught us that the mainstays of treatment in autoimmune myositis include corticosteroids (e.g., intravenous pulse Methylprednisolone, oral Prednisone in sequence, alongside bone and peptic ulcer protection), Methotrexate and steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents (e.g., Azathioprine, Mycophenolate, etc). In view of adverse events (including steroid-induced myopathy and “disfiguring” Cushing’s effect) in long term use needed, oral Prednisolone may be taken together with Azathioprine for at least three months, thenceforth, the former be slowly tapered for about three months prior to discontinuation. The steroid sparing drug shall be deemed to be the maintenance drug thereafter. There could be patients requiring steroids and in such a situation, it could be administered every other day together with the daily steroid-sparing agent. Rituximab and newer targeted therapies (e.g. Abatacept, Sifalimumab, Janus kinase inhibitors, Apremilast, and KZR-616 [

20]) have been tried as well.

In some settings intravenous/subcutaneous gamma globulin, may also be applied. Purportedly a neurodegenerative condition too, IBM resists immunosuppressive therapy, though a number of regimens have been tried. Exercise and physical therapy will be a complementary care. The red flag in the management of autoimmune myositis is the co-morbid malignancy, perhaps even as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Astute clinical assessment is required and screening for a malignancy from elsewhere (e.g. positron emission tomography-computerized scan [PET-CTscan]) may be key for early detection and management. In the absence of a malignancy elsewhere, a surveillance stance be the way for at least 5 years.

4. Granulomatous Myositis

Granulomatous myositis, a rare disease, affects the skeletal muscle wherein there is presence of a non-caseating granulomatous inflammation that can be unknown in nature or can also be associated with inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis. The disease was found to be predominant among the female population and during the fifth decade of life. Patients with granulomatous myositis can present with dysphagia and muscular weakness, which is often proximal bilaterally and symmetrically [

21]. The diagnostic test to confirm granulomatous myositis is a muscle biopsy which demonstrates a granuloma with infiltrating epithelioid histiocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells in the skeletal muscle fibers [

22]. Imaging studies such as MRI, CT, ultrasound, and PET-CT scan have been beneficial in aiding the diagnosis of granulomatous myositis and in choosing a satisfactory skeletal muscle tissue.

A. Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in affected organs. Organ involvement includes the lungs, skin, liver, eyes, bone, joints and muscles, wherein involvement of the musculoskeletal system is less common. The involvement of the skeletal muscles, when present, are usually with features of other organ involvement upon diagnosis. Cranial and peripheral nerve involvement in a focal or multi-focal presentation may occur alone or co-exist with myopathy, thus, posing a diagnostic challenge. Muscle involvement is more common in women. Acute myopathy is seen more in younger patients (<40 years), while chronic myopathy is found more in older patients (ages 50-70). The pathogenesis of Sarcoidosis is not well understood, but it is characterized by the accumulation of T lymphocytes, mononuclear phagocytes, and noncaseating granulomas [

23].

Sarcoidosis usually has moot symptoms, but patients with symptoms have a more acute disease and are associated with fever, myalgia, polyarthralgia and erythema nodosum. Chest imaging is important as this may show nodules [

23]. Three clinical patterns of symptomatic myopathy have been described, which are chronic myopathy, acute myositis, and nodular myopathy. Chronic myopathy is the most common form of sarcoid myopathy. It is insidious in onset of progressive symmetric proximal muscle weakness. This can lead to muscle atrophy, contractures and pseudohypertrophy. Acute myositis is more common among younger age (<40 yeast) and female patients. The manifestations include diffuse muscle swelling and pain in proximal muscles bilaterally (leading to contracture in a few), hardening and hypertrophy, mimicking acute polymyositis. The least common pattern is nodular myopathy which present with single or multiple, bilateral, tender nodules, found in the lower limbs usually. Nodules vary in size and are palpable and painful, not associated with muscle weakness or limitation of movement. Other symptoms may involve the diaphragm, extraocular muscles and the cardiac muscles [

23].

Diagnosis of sarcoid myopathy include elevated total CK (more commonly present in acute forms of myopathy), myopathic EMG, and Ultrasound and MRI findings, especially in nodular myopathy. Muscle biopsy show evidence of noncaseating granulomatous infiltration and high CD4:CD8 T lymphocyte ratio.

Asymptomatic muscle disease does not require pharmacologic therapy. Treatment of sarcoid myopathy involves the use of glucocorticoids (Prednisone), Hydroxychloroquine, and immunosuppressive agents (Methotrexate, Azathioprine or Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors). Glucocorticoids are tapered over one year, and immunosuppressive medication are continued for two to three years. Prognosis depends on the early management of the myopathies, however, these are not expected to be fatal. A chronic myopathy may lead to long term functional decline due to muscle atrophy [

23].

5. Metabolic Myopathies

Metabolic myopathies are a distinct group of disorders affecting different pathways of cellular energy metabolism caused by deficiency in a transport protein or an enzyme. Glycogen, glucose and free fatty acids are important for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in cells. Pyruvate, a glycogen metabolism product, enters into the mitochondria. The Carnitine transporter system allows long-chain fatty acid to enter mitochondria while short- and medium-chain fatty acids have free access. The Carnitine transporter system involves acylcarnitine translocase and carnitine palmitoyl transferases I and II. After entering into the mitochondria, all these substrates are metabolized to acetyl coenzyme A, which is an important substrate for ATP production through Krebs cycle. The defect in any of these biochemical pathways results in low ATP within the muscle resulting in weakness, muscle cramps especially during exercise, myalgia, exercise intolerance and rhabdomyolysis.

Many enzymes in the glycolytic and glycogenolytic pathway have then been associated with metabolic myopathies. Similarly, fatty acid oxidation defects affect free fatty acid transport or beta oxidation. Most patients have myopathic symptoms, but some of them, may have predominant central nervous system manifestations like in glutaric aciduria type II. The mitochondriopathies refer to metabolic genetic defects that affect the electron transport chain and lead to exercise intolerance with or without rhabdomyolysis or fixed weakness. The challenge in diagnosing these disorders is due to common clinical manifestation such as exercise intolerance and myoglobinuria but distinct features should be recognized. Intolerance at the start of the exercise indicates a problem in glycogen metabolism while a defect in fatty acid oxidation affects patients after prolonged exercise.

Defects in glycogen metabolism can be variable. The most common of which is represented by McArdle disease (Glycogen storage type V), an autosomal recessive disorder, wherein there is myophosphorylase deficiency. Patients with this disease experience muscle cramps, fatigue, contractures and myoglobinuria. Not only do they not tolerate static or isometric muscle contractions but they do not tolerate dynamic exercise as well. One pathognomonic sign of McArdle disease is the “second wind” phenomenon where there is marked improvement in exercise tolerance about 10 minutes into an exertional activity involving large muscle groups like running. There is decrease in exertional tachycardia from a heart rate of 140 beats per minute to 120 beats per minute. This is due to the lack of glycogen stores in McArdle disease that the body uses free fatty acids, which produces ATP at a slower rate, compared to glycogen, as the main source of energy. Intake of sugar improves the symptoms. Avoidance of activities that can trigger symptoms and a high carbohydrate diet is recommended [

24]. Another important glycogen storage disease is Pompe’s disease (Glycogen storage type IIa) wherein there is an accumulation of glycogen in the lysosomes due to a deficiency in alpha-glucosidase enzyme. This is also inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and is caused by a biallelic mutation in the acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) gene, also called acid maltase deficiency. This disorder predominantly affects the skeletal and cardiac muscles. In the infantile form, there is hypotonia presenting as a floppy baby, cardiomegaly and respiratory failure. In the adult form there is fixed muscle weakness and respiratory failure. Muscle biopsy in patients with accumulation of glycogen which correlates with the severity of clinical symptoms [

25]. Enzyme replacement therapy improves outcomes in patients. Alglucosidase alfa sold under the name Myozyme was FDA approved in 2014 and is given intravenously. It helps with absorption and digestion of glycogen and is an analog of alpha glucosidase. In August 2021, avalglucosidase alda was first approved in the United States for the treatment of late-onset Pompe disease [

26].

The most common lipid storage disease is carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT II) deficiency. Long chain fatty acids require transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane mediated by CPT I and II as well as acylcarnitine translocase, while short and medium chain fatty acids can freely cross into the mitochondria. This is also inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Symptoms usually begin at late childhood to adulthood. Patients would experience frequent episodes of myalgias, muscle stiffness, weakness and myoglobinuria. Symptoms are usually brought about by prolonged fasting or exercise and infection. Patients are asymptomatic between attacks. Since fatty acids are the main source of energy for muscle at rest and during periods of prolonged activities, patients manifest their symptoms at the end of rigorous exercise. Symptoms may also be provoked by stressors like fasting, infections, fever and exposure to cold. A high carbohydrate diet improves exercise endurance.

For the work-up of metabolic myopathies, the serum total CK may show modest elevations and is usually higher in those with high risk of rhabdomyolysis. In those with phosphofructokinase deficiency, complete blood count and reticulocyte count may show signs of hemolytic anemia. A needle EMG may show myotonic discharges in acid maltase deficiency. Generally, needle EMG may reveal short-duration, low-amplitude motor unit action potentials. However, EMG readings may be normal in many metabolic myopathies.

A detailed description of metabolic myopathies with therapeutic approaches is found in an accompanying article in this present special issue compilation [

27].

6. Muscle Channelopathies

Skeletal muscle channel myopathies are a group of rare and diverse conditions that involve mutations in the genes responsible for ion channels that enable proper functioning. Some of which would include

SCN4A (Sodium channels),

CLCN1 (Chloride channels),

KCNJ2 and

KCNJ18 (Potassium channels), as well as

CACNA1S (Calcium channels) [

28]. These myopathies can be divided into periodic paralyses and the nondystrophic myotonias. The periodic paralyses include Andersen-Tawil syndrome, hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis, and hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. Myotonia congenita, sodium channel myotonia, and paramyotonia congenita are the non-dystrophic myotonias. It is important to ask about early life history because symptoms can appear as early as during the first and second decade. Symptoms may sometimes develop later in life or during pregnancy [

29]. Since these ion channels are responsible for muscle membrane excitability, these myopathies are typically characterized by paroxysmal symptoms ranging from exaggerated muscle contraction or over-excitability to muscle weakness or inexcitability. Moreover, due to the overlapping clinical manifestations of these myopathies, there has been difficulty in ascertaining which genes are responsible, and in effect, which treatments would be most effective.

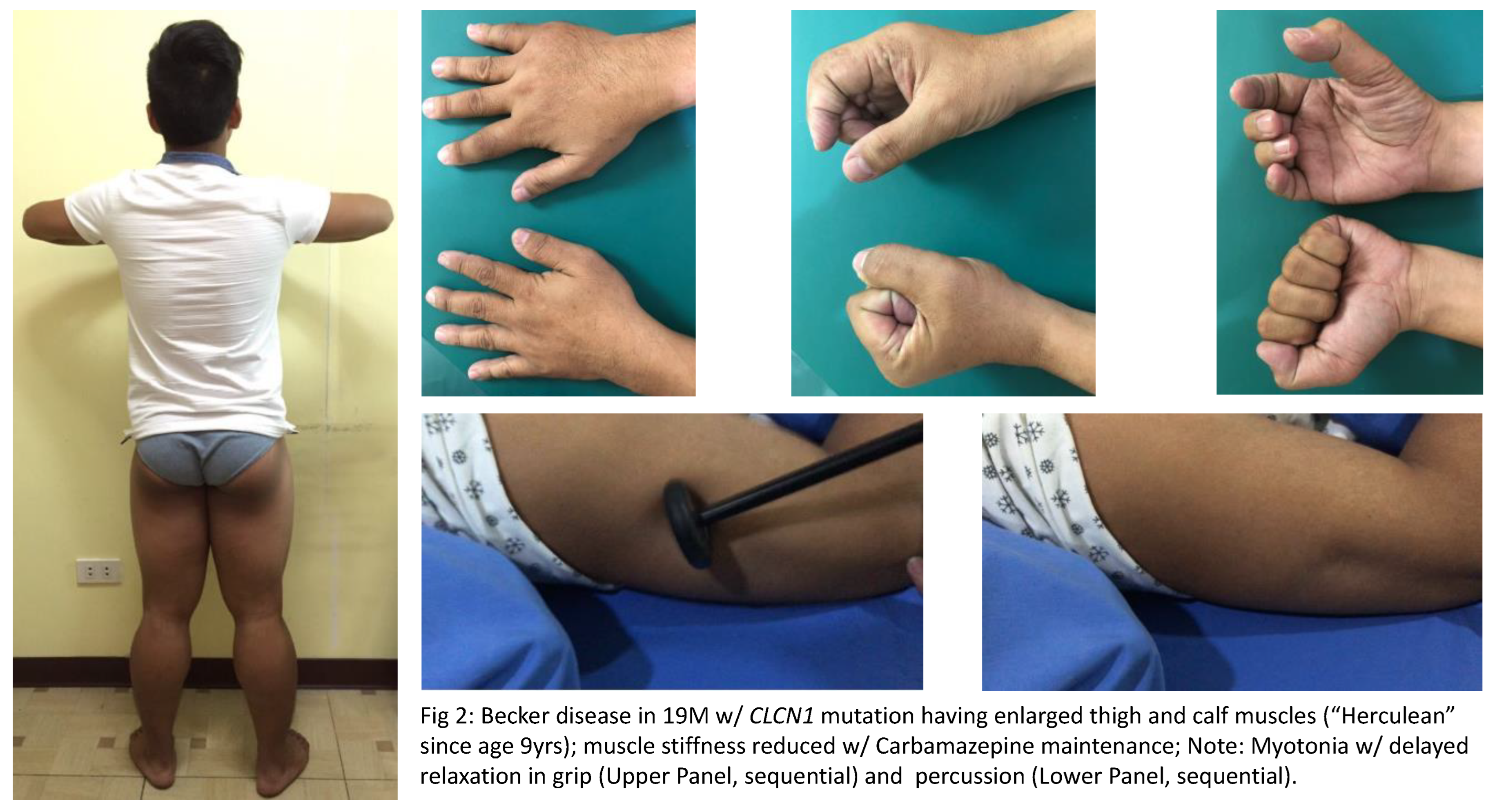

A. Nondystrophic Myotonias or NDMs are characterized by hyperexcitable conditions wherein there may either be a gain-of-function mutation in the

SCN4A gene or loss-of-function mutation in the

CLCN1 gene (see illustrative case in Figure 2). Generally associated with grip, percussion, temperature aggravated and electrical myotonias (waxing-waning, “dive bomber sound” due to delayed muscle relaxation), these disorders encompass Myotonia congenita (“Herculean” muscles; Autosomal dominant [Thomsens] and recessive [Becker] Chloride channelopathies), Sodium channel myotonias (includes Congenital myopathy) and Paramyotonia congenita (worsens with exercise and cold temperature; Eulenberg disease). Clinically, these are seen as muscle stiffness after voluntary contraction or percussion. With a prevalence of only <1:100,000 people, these disorders usually occur within the first two decades of life, and in the absence of progressive muscle wasting. These may be inherited either in an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive manner. At this point in time, sources have reiterated that there are no FDA approved treatments, and that only certain symptomatic management strategies are available such as addressing triggers, as well as maintaining non-sedentary behavior. Symptomatic treatments to reduce muscle stiffness in NDM include Carbamazepine, Phenytoin, Mexilitine, Dantrolene, Quinine, Acetazolamide, Trimeprazine and Retigabine [

30].

NDM should not be mistaken for another myotonic disorder in muscle (also with grip, percussion and electrical myotonias) accompanied by multi-organ disorders (baldness, cataracts, cardiac disease and insulin resistance, among others), called Myotonic Dystrophies (Types 1 [distal dominant weakness plus facial and ocular muscle weakness] and 2 [proximal dominant weakness], with DMPK and CNBP mutations, respectively). The Pseudomyotonias (grip myotonia but not with the typical percussion myotonia and electrical myotonia) are seen in a nerve terminal hyperexcitability disorder, Isaac’s disease/Neuromyotonia. The latter is a VGKC channelopathy associated with myokymias hyporeflexia, hyper-sweating and disabling muscle stiffness. Immune therapies will be choice treatment for VGKC channelopathies, whether paraneoplastic and/or associated with dementia (Morvan syndrome).

B. Primary Periodic Paralyses, on the other hand, are a set of disorders that involve sodium, potassium, and calcium channel gene mutations. These disorders occur due to aberrant depolarization leading to inactivated sodium channels, which primarily result in reduced muscle membrane excitability. Thus, the clinical presentations be that of episodic generalized (mainly) or focal weakness. These are autosomal dominant in nature and would include hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, and Anderson-Tawil Syndrome. Cases may be diagnosed through a history of flaccid paralysis accompanied by changes in serum potassium levels. Unlike that of NDM, literature [

28,

29,

30] has supported the notion of the use of Dichlorphenamide, and Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors/Acetazolamide as treatment for this periodic paralyses.

C. Secondary periodic paralysis result from potassium wasting (following high carbohydrate meal/heavy exercise, diuretic use, renal/adrenal disorders, licorice diet, among others) and from thyrotoxicosis. Cranial muscles are usually spared and most will present in the morning with quadriparesis. One may consider application of electrophysiologic short and prolonged exercise test for differentiation, a procedure that also aids in sorting channelopathies. Prudent correction of the electrolyte and hormone abnormalities be the key treatments. However, as these are secondary clinical phenomena, the main target organ disorders (e.g. kidney, adrenal, thyroid glands) should be accordingly managed.

7. Drug-induced Myopathies

Drug-induced myopathy is an acute or subacute onset of muscle weakness, myalgia, CK elevation and myoglobinuria after intake of certain medications at therapeutic doses. Discontinuation of the offending medication resolves the myopathy. There are a lot of drugs that can cause myopathies, and includes hydroxychoroquine, amiodarone, among others. These myotoxic substances may either affect muscle organelles such as myofibrillar proteins, may induce systemic effects like malabsorption or electrolyte imbalances and may induce an inflammatory response [

31]. One of the most common causes of drug-induced myopathy is from Statin use. It is a cholesterol lowering drug that inhibits hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase. Statins are most commonly prescribed to patients with dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, hypertension and coronary artery disease. Skeletal muscle adverse effects are said to occur in 5-10% of patients. Statin-Associated Muscle Symptoms (SAMS) may present with muscle tenderness, cramps, weakness and an elevated CK level of up to 10 times the upper limit of the normal level and sometimes rhabdomyolysis. It is said that statins affect the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of type II fibers. Since type II fibers contains 30% less fat than type I fibers, it is more prone to damage caused by reduced cholesterol that is available for membrane production or biosynthesis. Statins also cause an immunologic reaction by changing regulatory expression of T cells and B cells, leading to the production of autoantibodies. The highest incidence of statin-induced myopathy is with simvastatin while rosuvastatin and fluvastatin have the lowest. Symptoms are usually reversible after statin withdrawal [

32].

Another cause of myopathy is from intake of colchicine in patients with gout. Those with renal insufficiency and are taking nephrotoxic drugs like Cyclosporine are more prone to this adverse effect. Patients experience proximal muscle weakness, elevated CK level, areflexia and sometimes sensory symptoms. It is said that colchicine can interfere with the growth of microtubules and that long-term use can cause vacuolar myopathy with accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and lysosomes and axonal neuropathy. Symptoms resolve after 4 to 6 weeks of discontinuing the medication.

Steroid-induced myopathic weakness, typically presenting with bilateral quadriceps weakness, is another adverse effect that patients experience especially during chronic administration of Prednisone or Dexamethasone. It is said that it is generally mild and may spare the neck flexor muscles, however, it may aggravate any pre-existing weaknesses especially in cancer patients. The CK level and EMG in these patients are normal which is why it is not considered a true myopathy. On muscle biopsy there is only atrophy of type II fibers [

31]. Lowering the dose may reverse the myopathic weakness.

A clinical syndrome marked by myalgia, eosinophilia and scleroderma-like skin manifestations have been associated with L-tryptophan use. The syndrome mimics eosinophilic fasciomyositis (Shulman’s syndrome), the latter being responsive to immunosuppressive therapy.

There should be awareness too that cancer treatment with Immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g. Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, etc.) may elicit immune-mediated myopathy (and even myasthenia), and muscle biopsies may show necrosis and mitochondrial abnormalities.

8. Intensive Care (ICU) Acquired Weakness

The clinical definition of Intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW) is a noted weakness in critically ill patients and where the only etiologically plausible cause is the critical illness itself, and upon which weakness may persist long after discharge from ICU. Sepsis syndrome/or shock, multiple organ failure, metabolic variables like hyperglycemia, and duration of mechanical ventilation (MV) are among the risk factors for ICUAW. Attributable to weakness are impaired muscle contractility, muscle wasting, neuropathy, and pathways related to ubiquitin proteasome system and dysregulated autophagy which are associated with muscle protein degradation. Moreover, a preferential loss of myosin, is a distinct feature [

33].

By nosology, ICUAW include critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP), critical illness myopathy (CIM), and an overlap syndrome, critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM). Versus CIP, the diagnostic criteria for CIM include: Presence of Critical illness; Limb weakness or difficulty weaning from MV (non-neuromuscular causes excluded); Compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) less than 80% lower limit of normal in at least two nerves without conduction block; CMAP duration increased on nerve or direct muscle stimulation; Sensory nerve action potentials are greater than 80% of lower limb of normal; Needle EMG shows myopathic potentials with early or normal recruitment in awake/collaborative patients; Absence of abnormal response to repetitive nerve stimulation; and Muscle biopsy with evidence of myopathy (e.g. myosin loss or muscle necrosis). Current management strategies include: Achievement of euglycemia (Intensive insulin therapy has been shown to have a protective effect); Early mobilization (has positive functional outcomes); Functional electrical stimulation (robust studies still desired); and Nutritional intervention (promote muscle protein synthesis in relation to immobility) [

34].

9. Rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis is an urgent care acute myopathy with high morbidity and mortality, if not attended to. The causes include direct muscle trauma, status epilepticus, initiation/high dose use of medications (e.g. statins, anticonvulsants, anti-psychotic agents), toxins, infections (e.g. Weil’s disease), muscle ischemia, metabolic/electrolyte disorders, exertion or prolonged bed rest, genetic disorders and temperature-induced states (e.g. neuroleptic malignant syndrome [NMS] and malignant hyperthermia [MH]). The triad of rhabdomyolysis constitute myalgia, weakness and myoglobinuria. An elevated total CK level is considered the sensitive test for muscle injury–induced rhabdomyolysis.

Foremost treatment aim in suspected rhabdomyolysis is care to avoid acute kidney injury. Fluid management is crucial in preventing prerenal azotemia, given the risk of muscle compartment fluid accumulation and the complication of hypovolemia. Thus, 1.5 L/h rate of aggressive hydration is suggested, while cognizant of cardiac overload. As an option, consider a 500 mL/h saline solution to be alternated every hour with 500 mL/h of 5% glucose solution with 50 mmol of sodium bicarbonate for each subsequent 2-3 L of solution. Also important in management is urine alkalization for renal protection against the nephrotoxicity from myoglobinuria and hyperuricosuria. Therefore, one should achieve a urinary output goal of 200 mL/h, urine pH >6.5, and plasma pH <7.5. The other management strategies include reversal of inappropriate arteriolar vasodilation through arteriolar restoration of contractility in injured muscles (i.e. mainly correction of acidosis and hyperkalemia). Likewise, mobilizing intramuscular edema will protect integrity of muscles and decompress muscle compartments [

35]. In a center retrospective study of surgical anesthesia among cases with dystrophinopathy, they found no cases of rhabdomyolysis upon application of total intravenous anesthesia and no evidence for or against volatile anesthetic usage in this patient population. It is to be emphasized that no anesthetic agent is risk free. Non-triggering anesthetics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, propofol, ketamine, and fasting have resulted to rhabdomyolysis in certain cases, including use of succinylcholine for muscle relaxation [

36].

10. Inherited Myopathies

Certain inherited myopathies are currently undergoing various phase treatment trials, mainly genetic or through inflammatory approaches. DMD and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) are the most frequent and best studied early-onset muscular dystrophy. DMD is a severe, progressive, inherited neuromuscular disease involving mutations in the

dystrophin gene [

37]. It is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner, making it a disease that is very rare in females. It affects 1 in 3500 to 5000 live male births [

38]. Becker muscular dystrophy is caused by DMD gene mutation but still allows residual expression of dystrophin protein. Symptoms are milder compared to DMD patients. Dystrophin, being an integral part of the structural unit of the muscle, causes impairment in the myofibers’ structure and contractility, calcium dysregulation, and oxidative stress when lost, which ultimately leads to myocyte necrosis [

39,

40]. Dystrophin also increases the stability of the plasma membrane in myofibers. Due to the muscle-wasting nature of this disease, muscle weakness has been a primary manifestation, commonly affecting the proximal muscles, especially that of the lower extremities. This weakness becomes more generalized as the disease progresses. Developmental milestones may be achieved normally during the first few years of life, however, there also might be a delay in attaining these milestones, as well as delay in growth rate, and impairment in muscle tone during infancy. Most patients would typically note difficulties in ambulation, running, climbing the stairs, and frequent falling during the first 2-3 years of life, although late onset manifestations may occur (ie., in the third or fourth decade of life). A classic and early feature of DMD is pseudohypertrophy of the calves and wasting of the thigh muscles. Other manifestations include waddling gait, frequent fracture secondary to falls, joint contractures, aspiration and hypernasality secondary to pharyngeal muscle weakness, urine and stool incontinence due to weakness of the sphincter muscles, and heart failure due to cardiac involvement.

Training exercises may be beneficial in DMD but again the evidence remains uncertain. This needs further research to know whether these training exercises promote functioning and improve health-related quality of life [

40]. There is also no concrete evidence regarding the use of assistive devices but there are some studies in orthopedic assistive devices that can help the patient with DMD. However, genetic counselling be important as will respiratory and nutritional care. While several potential medications or drugs are now being studied, prolonged use of oral steroids (with bone protection) have been there in use, and alluded to, in regional expert consensus [

41]. Gene therapy, involving the insertion of a dystrophin gene through a vector, has proven effective in animals but not humans. Ataluren, which is under a clinical study, is a molecule that binds with ribosomes and may allow the insertion of an amino acid in the premature termination codon, and producing a dystrophin that is smaller but functional [

42].

The most common complications of this disease include those of decreased muscle function, spinal deformities, cardiovascular and respiratory compromise, and affected bone health. Therefore, it is important to note that a multidisciplinary approach must be undertaken to optimize the living conditions of patients suffering from this condition. Much importance must be given to identifying and targeting possible aspects that may be improved through either medical, technological, or engineering interventions [

43]. Studies have shown that although DMD is a progressive disease, life expectancy rates have improved with advances in technology and medical treatment [

44].

Exon skipping therapy is now used for these patients. These are antisense oligonucleotides that are approved for DMD patients. Viltolarsen, Golodirsen and Eteplirsen and Casimersen exon skipping drugs that can be given intravenously once a week. Exon skipping drugs restores the reading frame to allow DMD patients to make BMD-like residual dystrophin protein. It offers the possibility to restore the levels of residual functional dystrophin and can slow disease progression however it cannot restore muscle that was already lost. Renal function should be monitored in these patients because of the nephrotoxic side effect of antisense oligonucleotides.

For certain inherited myopathies to date, virus vector-based gene therapies have been in the offing. A more novel targeted genome editing through viral vectors to deliver a gene-editing system (e.g. CRISPR technology) have been explored to replace mutations in genes with correct nucleotides. Interestingly, Sialylation increasing therapies with ManNAc have been tried in Distal myopathy from

GNE mutation [

45].

11. Conclusion

Therapies abound as these are targeted in specific myopathies such as Infectious (based on pathogen), Granulomatous and Autoimmune Myopathies. Included in treatable myopathies are certain metabolic myopathies, rhabdomyolysis, periodic paralysis, critical illness myopathy and drug-induced myopathies. Symptomatic therapies are applied in channelopathies of muscle and dystrophinopathies can be potentially treated nowadays. Alongside rehabilitation practices and exercise in moderation are complementary regimen. Exon skipping therapy which offers functional restoration of residual dystrophin are now used for DMD patients.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”, please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding, any errors may affect your future funding.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflict of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Crum-Cianflone, N.F. Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008, 21, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.N.; Eggelbusch, M.; Naddaf, E.; Gerrits, K.H.L.; van der Schaaf, M. , van den Borst, B. ; Wiersinga, W.J.; van Vugt, M.; Weijs, P.J.M.; Murray, A.J.; Wüst, R.C.I. Skeletal Muscle Alterations in Patients with Acute Covid-19 and Post-acute Sequelae of Covid-19. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month Consequences of COVID-19 in Patients Discharged from hospital: A Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saud, A.; Naveen, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Gupta, L. COVID-19 and Myositis: What We Know So Far. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021, 23, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, I.; Hashimoto, K.; Matsuoka, E.; Rosales, R.L.; Nakagama, M.; Arimura, K.; Izumo, S.; Osame, M. The Main HTLV-1-harboring Cells in the Muscles of Viral Carriers with Polymyositis are not Macrophages but CD4 Lymphocytes. Acta Neuropathol. 1996, 92, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayathri, N.; Bevinahalli, N.N. Infective Myositis. Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, e12950:1–e12950:16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberger, R.; Gupta, V. Streptococcus Group A. Available online: http://statpearls.com/point-of-care/29529 (accessed on 06 February 2023).

- El-Beshbishi, S.N.; Ahmed, N.N.; Mostafa, S.H.; El-Ganainy, G.A. Parasitic Infections and Myositis. Parasitol Res. 2012, 110, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanboon, J.; Nishino, I. Classification of Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies: Pathology Perspectives. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019, 32, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakas, M.C. Inflammatory Muscle Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 1734–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva-O’Callaghan, A.; Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Trallero-Araguás, E.; Milisenda, J.C.; Grau-Junyent, J.M.; Mammen, A.L. Classification and Management of Adult Inflammatory Myopathies. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWane, M.; Waldman, R.; Lu, J. Dermatomyositis Part I: Clinical Features and Pathogenesis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Mann, H.; Pleštilová, L.; Zámečník, J.; Betteridge, Z.; McHugh, N.; et al. Increasing Incidence of Immune-mediated Necrotizing Myopathy: Single-centre Experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015, 54, 2010–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Casal-Dominguez, M.; Mammen, A.L. Immune-mediated Necrotizing Myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allenbach, Y.; Benveniste, O.; Stenzel, W.; Boyer, O. Immune-mediated Necrotizing Myopathy: Clinical Features and Pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020, 16, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, Q.; Bettencourt, C.; Machado, P.M.; Fox, Z.; Brady, S.; Healy, E.; Parton, M.; Holton, J.L.; Hilton-Jones, D.; Shieh, P.B.; et al. Muscle Study Group and the International IBM Genetics Consortium(#). The Effects of an Intronic Polymorphism in TOMM40 and APOE Genotypes in Sporadic Inclusion Body Myositis. Neurobiol Aging 2015, 4, 1766:e1–1766:e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinc, A.H.; Makowska, J.S. Antisynthetase Syndrome - Much More Than Just a Myopathy. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021, 51, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfraji, N.; Mazahir, U.; Chaudhri, M.; Miskoff, J. Anti-synthetase Syndrome: A Rare and Challenging Diagnosis for Bilateral Ground-glass Opacities—A Case Report with Literature Review. BMC Pulm Med 2021, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, L.J.; Curran, J.J.; Strek, M.E. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Antisynthetase Syndrome. Clin Pulm Med 2016, 23, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadam-Kia, S.; Oddis, C.V. Current and New Targets for Treating Myositis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022, 65, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-González, S. , Grau, J. M. Diagnosis and Classification of Granulomatous Myositis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Meegada, S.; Akbar, H.; Siddamreddy, S.; Casement, D.; Verma, R. Granulomatous Myositis Associated with Extremely Elevated Anti-striated Muscle Antibodies in the Absence of Myasthenia Gravis. Cureus 2020, 12, e6986:1–e6981:11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, A.; Kremer, J.M. Immunopathology, Musculoskeletal Features and Treatment of Sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1993, 5, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Z.E.; Ashraf, M. McArdle Disease. Available online: http://statpearls.com/point-of-cre/24796 (accessed on 05 Feb 2023).

- Kohler, L.; Puertollano, R.; Raben, N. Pompe Disease: From Basic Science to Therapy. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. ; Avalglucosidase, A: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtizberea, J.A.; Severa, G.; Malfatti, E. Metabolic Myopathies in the Era of Next-Generation Sequencing. Genes 2023, 14, 954 doiorg/103390/genes14050954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.; Trivedi, J.R. Skeletal Muscle Channelopathies. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, E.; Holmes, S.; Fialho, D. Skeletal Muscle Channelopathies: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management. Pract. Neurol. 2021, 21, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stunnenberg, B.C.; LoRusso, S.; Arnold, W.D.; Barohn, R.J.; Cannon, S.C.; Fontaine, B.; Griggs, R.C.; Hanna, M.G.; Matthews, E.; Meola, G.; et al. Guidelines on Clinical Presentation and Management of Nondystrophic Myotonias. Muscle Nerve 2020, 62, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakas, M.C. Toxic and Drug Induced Myopathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009, 80, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardo, S.; Musumeci, O.; Velardo, D.; Toscano, A. Statins Neuromuscular Adverse Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, H.; Saumur, T.M.; Herridge, M.S.; Dos Santos, C.C.; Mathur, S.; Batt, J.; Gilbert, P.M. Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: Not Just Another Muscle Atrophying Condition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Rathbone, A.; Melanson, M.; Trier, J.; Ritsma, E.R.; Allen, M.D. Pathophysiology and Management of Critical Illness Polyneuropathy and Myopathy. J Appl Physiol. 2021, 130, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, P.A.; Helmstetter, J.A.; Kaye, A.M.; Kaye, A.D. Rhabdomyolysis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Ochsner J. 2015, 15, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Segura, L.G.; Lorenz, J.D.; Weingarten, T.N.; Scavonetto, F.; Bojanic, K.; Selcen, D.; Sprung, J. Anesthesia and Duchenne or Becker Muscular Dystrophy: Review of 117 Anesthetic Exposures. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013, 23, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, D.; Goemans, N.; Takeda, S.; Mercuri, E.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eser G, Topaloğlu H. Current Outline of Exon Skipping Trials in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Genes 2022, 13, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, S.; Sultana, J.; Fontana, A.; Salvo, F.; Messina, S.; Trifiro, G. Global Epidemiology of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, S.; Toussaint, M.; Vollsæter, M.; Tvedt, M.N.; Røksund, O.D.; Reychler, G.; Lund, H. , Andersen, T. Exercise Training in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Rehabil Med 2022, 53, 985:1–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F.; Nakamura, H.; Yonemoto, N.; Komaki, H.; Rosales, R.L.; Kornberg, A.J.; Bretag, A.H.; Dejthevaporn, C.; Goh, K.J.; Jong, Y.J.; et al. Clinical Practice with Steroid Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: An Expert Survey in Asia and Oceania. Brain Dev 2020, 42, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beytía, M.L.; Vry, J.; Kirschner, J. Drug Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Available Evidence and Perspectives. Acta Myol. 2012, 31, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bushby, K.; Bourke, J.; Bullock, R.; Eagle, M.; Gibson, M.; Quinby, J. The Multidisciplinary Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Curr. Paediatr. 2005, 15, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomfield, J.; Hill, M.; Guglieri, M.; Crowther, M.; Abrams, K. Life Expectancy in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Reproduced Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Neurol 2021, 97, e2304–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, N.; Malicdan, MC.; Huizing, M. GNE Myopathy: Etiology, Diagnosis and Therapeutic challenges. NeuroTherapeutics 2018, 15: 900-914.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).