1. Introduction

Companies focused on long-term success should not only pay attention to finance-related objectives but also allocate part of their investment to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs that generate progress and social benefits (del Brio and Lizarzaburu, 2018, 2020). Specifically, companies need to engage in sustainable development within the communities in which they operate, maintaining not only high standards in the quality of the products or services they provide, but also having a good reputation and image of a responsible organization (Porter, 1980,1985). Not surprisingly, CSR started to gain attention as the communities in which companies operate noticed that the latter plays a relevant role in terms of social impact (Galbreath, 2010).

Gunningham et al. (2009) detail the bridge from CSR to social impact in the context of the oil industry. These companies' business is based on managing a country's natural resources to produce goods and services (Ghanbarpour and Gustafsson 2022). However, the industrial process of such products, namely natural gas, and oil, usually causes unintended consequences like pollution, which ultimately affect local communities. Previous research widely documents a negative social and environmental impact of the oil industry activity. As an example, it can be mentioned the global warming caused by oil production and use, the deterioration in air and water quality around oil refineries, or the "curse of resources” which affects countries with abundant oil resources (Henry et al., 2016; Jaworska, 2018).

Due to the increasing concern about these negative externalities, stock markets are paying more attention to the so-called ESG investments (i.e., socially responsible investing) (Escrig-Olmedo et al., 2017; Garcia et al., 2017; Rajesh, 2020; Yin et al., 2020). Besides, oil companies are more interested in obtaining a license to operate in a third country by showing high standards of CSR (Johansen and Nielsen, 2011; Høvring et al., 2018). This issue is especially relevant in the context of emerging markets, whose economies are based on exporting natural resources to advanced economies. The Peruvian oil industry, a very wealthy and profitable one, is not an exception (Whellams, 2007). Thus, it becomes relevant to study the relationship between CSR and social impact in such a context.

However, there is not a consensus in explaining the positive role of CSR and its relationship with social impact. On the one hand, Henry et al. (2016) and Jaworska (2018) express concern regarding the sincerity of the oil industry's commitment to CSR; criticizing the fact that CSR is nothing more than a facade to allow the industry to continue doing business as usual (García-Gomez., et al. 2022). More recent investigations of Social impact have proven how Social impact extends CSR with specific corporate benefits. CSR and Social impact share the intentions to be part of the community for the lifestyles of the project and to share benefits (Collins and Kumral, 2020; Thomson and Boutilier, 2011; Prno, 2012). When embedded in the broader context of CSR, the external drivers in the direction of adopting a Social impact approach can be associated with company reputation, stakeholder expectations, and legislation (Lozano and Von Haartman, 2018; Lozano, 2015). Rather than treating CSR as a public relations strategy, oil companies should integrate it into their business operations, minimizing its negative externality and investing more substantially in alternative renewable energy (Kitsios et al., 2020; Ike et al., 2019). Its intention is to boom or establishes CSR values such as responsibility and credibility for industry and stakeholders (Collins and Kumral, 2020; Nelsen, 2006). There is not a clear understanding of the relationship between these two terms. Therefore, the objective of this research is to determine how the relationship between CSR and Social Impact.

1.1. About the industry

In the last 20 years, Peru has witnessed important changes in the national and international hydrocarbon industry. The liquid hydrocarbons subsector, in particular, contributed significantly to the development of the country since the beginning of the Republic. The recognition of the relevance of this industry and its important role in the Peruvian economy motivate the preparation of this book, where a review of the historical evolution of the liquid hydrocarbons industry and a balance of the economic and regulatory aspects that characterize the subsector.

Liquid hydrocarbons will have around 75% participation in the Peruvian energy matrix by 2025 compared to the 65% they represented in 2017. The hydrocarbons sector represents about 3% of Peru's GDP and in the last 12 years, the accumulated added value generated by the sector was the US

$ 58.315 million. Likewise, the accumulated investment in the hydrocarbon sector between 2000 and 2018 totaled US

$ 16,040 million according to the former Deputy Minister of Energy during the presentation of the study “Contributions of the hydrocarbon sector to the national and regional economy in Peru” (Minería y Energía, 2020). See

Table 1 and

Table 2:

Raw materials are considered to be oil and natural gas, which are listed without problems on the world market, in a standardized way and their price is properly determined by supply and demand. Oil is essential to many industries and important for the maintenance of industrial civilization in its current configuration, making it a critical concern for many nations and accounting for a large percentage of global energy consumption (Dunkle and Winniford, 2020; Jafarinejad, 2016).

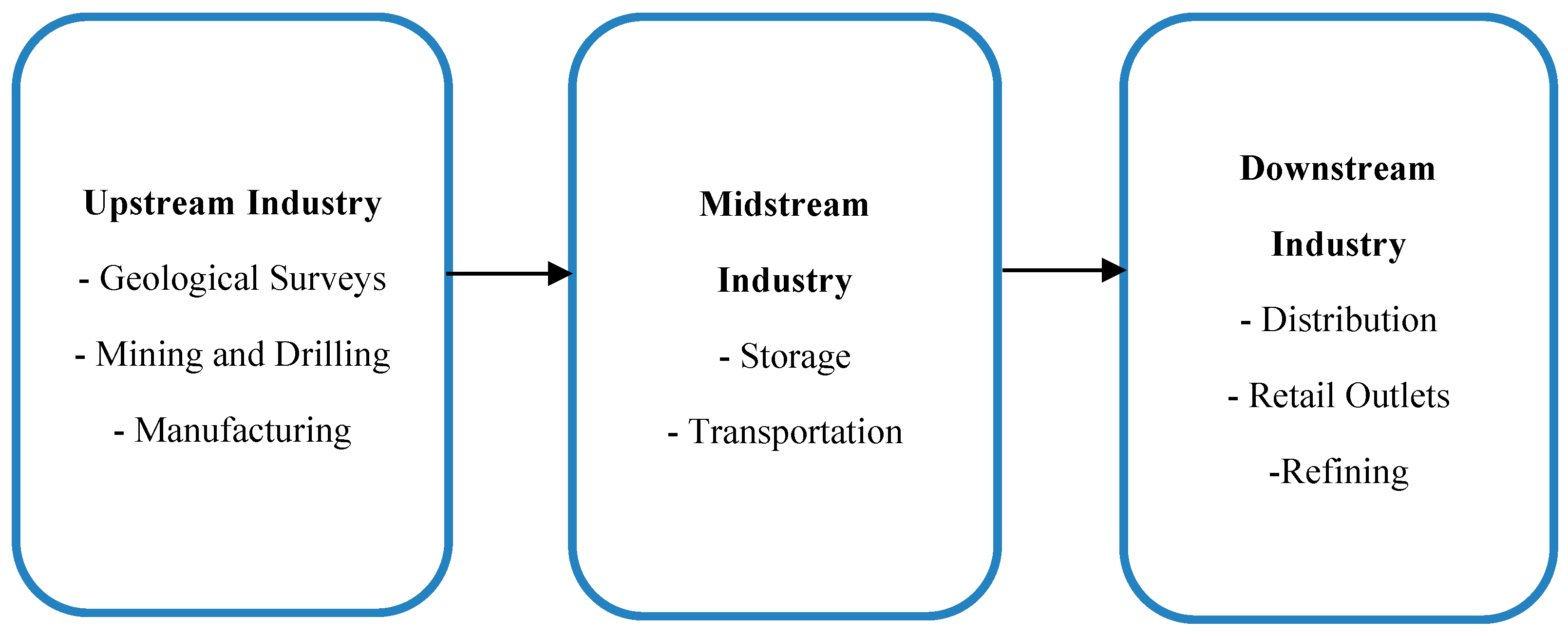

In this way, it is possible to add the petroleum industry is a high capital (asset) intensive industry, where the supply chain, waste generation, and carbon emissions can be classified into upstream, midstream, and downstream (Zhang and Yousaf, 2020). In addition, From the production/operations management perspective, the petroleum industry has several unique characteristics that distinguish it from other industries (Liu et al., 2019): Suppliers, raw materials, reverse production system, high transportation cost, production process, sources profitability and information sharing. As previously commented, this industry is usually divided into three major components: upstream, midstream, and downstream (Al-Janabi, 2020). Upstream usually includes exploration, development, and production of crude oil and natural gas (Hassani et al., 2020). The Midstream segment, as its name implies, encompasses facilities and processes that sit between upstream and downstream segments (Owuso and Poi, 2019).

Figure 1.

Oil Industry Phases. Source: Own elaboration

Figure 1.

Oil Industry Phases. Source: Own elaboration

According to Hsu and Robinson (2019) and Owuso and Poi (2019), both the upstream and downstream operations in the petroleum industry can generate a large number of oily wastes. The upstream operation includes the processes of extracting, transporting, and storing crude oil (Hassani et al., 2020), while the downstream and midstream operation refer to crude oil refining processes. The oily waste generated in the petroleum industry can be categorized as either simple oil or sludge depending on the ratio of water and solids within the oily matrix. Simple waste oil generally contains less water than sludge that is highly viscous and contains a high percentage of solids. Stable water-in-oil (W/O) emulsion is a typical physical form of petroleum sludge waste. In the upstream operation, the related oily sludge sources include slop oil at oil wells, crude oil tank bottom sediments, and drilling mud residues (Zhang and Yousaf, 2020).

2. Materials and Methods

A framework is developed to understand how the relationship between CSR and social impact works. This framework is based on the reviewed literature.

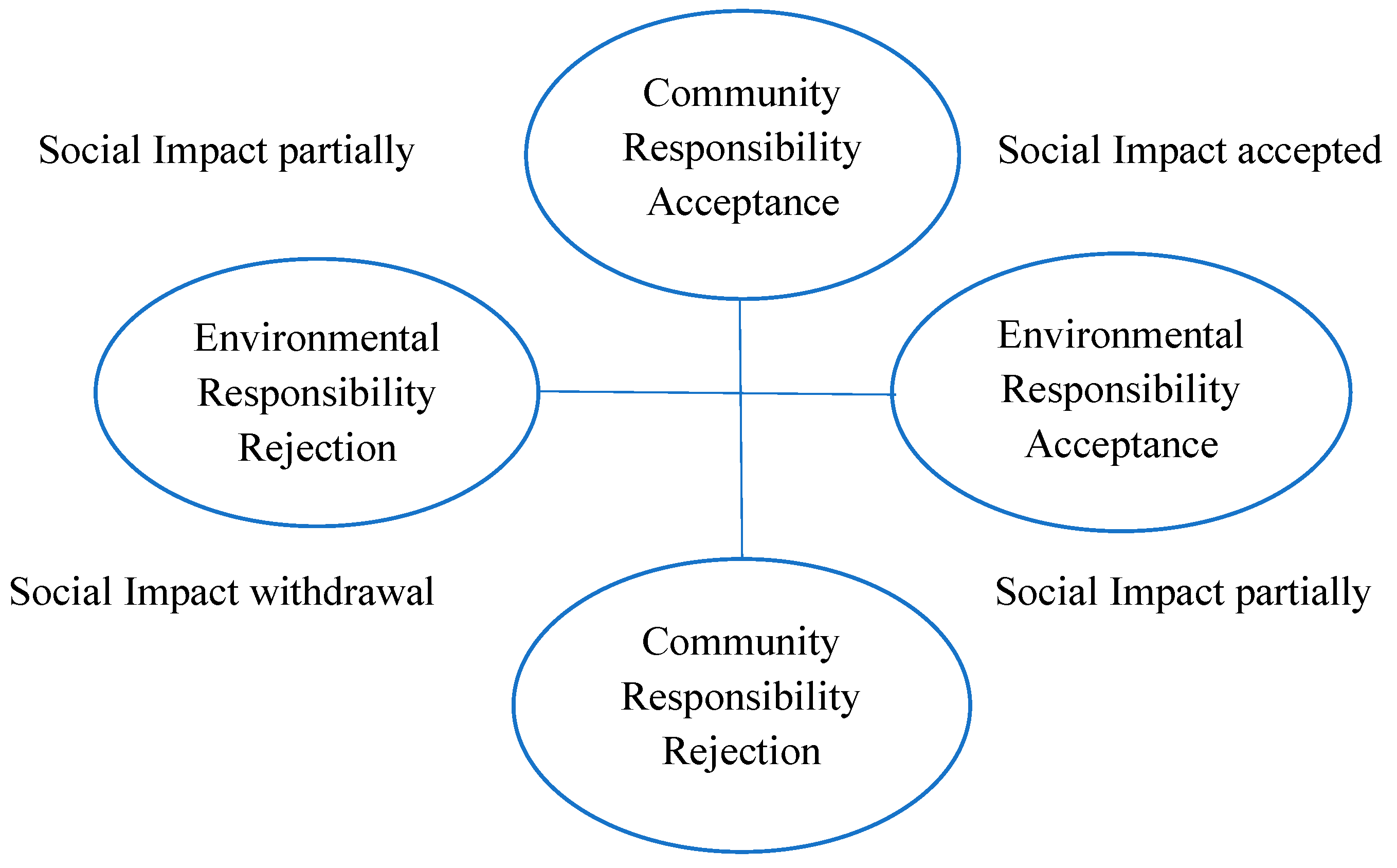

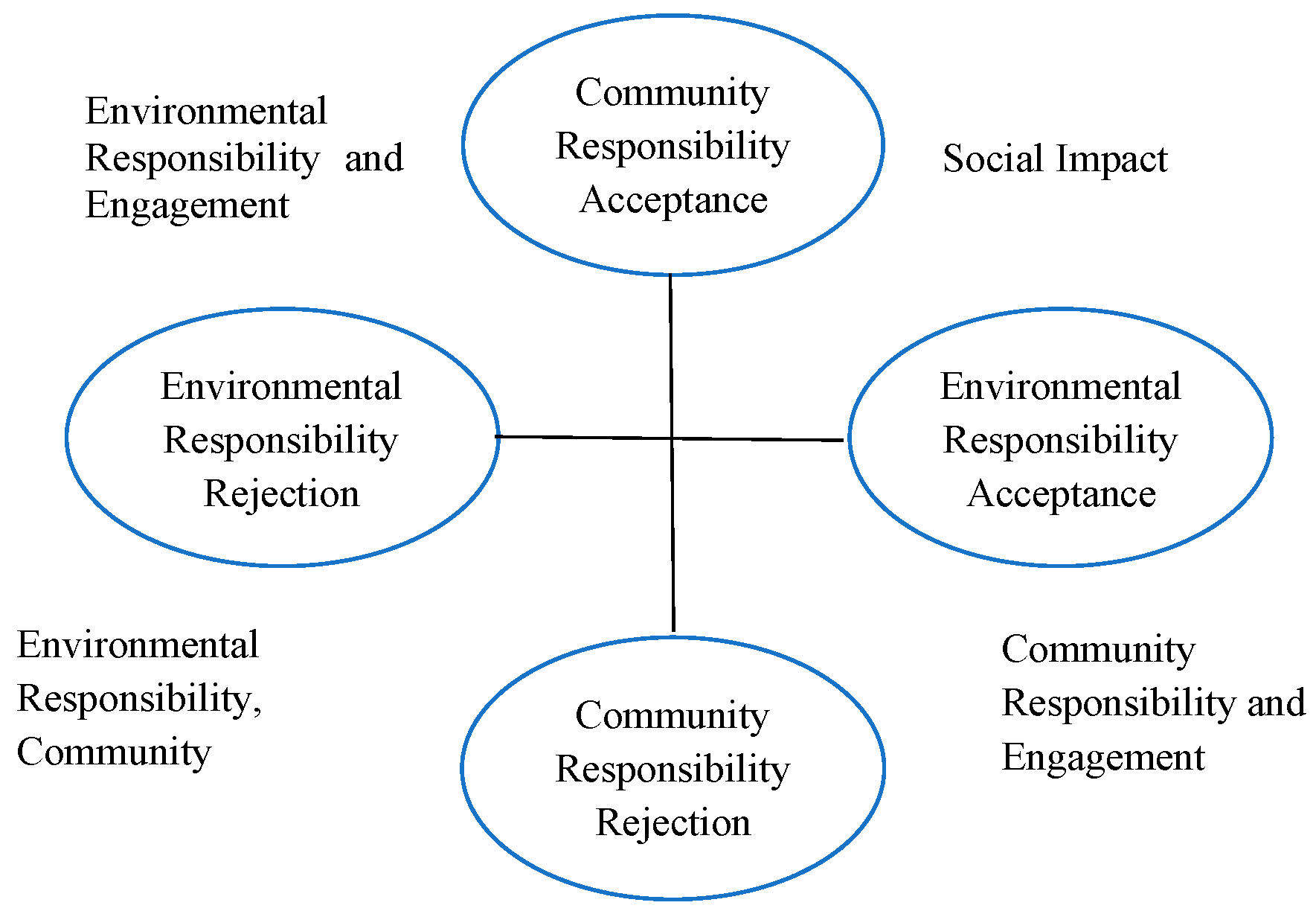

Figure 2 shows the social and environmental project.

The framework presented in

Figure 2 explores the relationship between environmental concerns and social concerns in an oil project. The x-axis represents varying intensities of environmental concerns from environmental rejection to environmental acceptance to get Social Impact. The y-axis represents different intensities of social-economic concerns from social rejection to social acceptance to earning Social Impact.

The framework depicts four quadrants that represent Social Impact states. For community responsibility acceptance and environmental responsibility acceptance, Social Impact is granted or accepted. For community responsibility acceptance and environmental responsibility rejection, Social Impact is partially accepted. For environmental responsibility rejection and community responsibility rejection, Social Impact is withdrawn. Finally, for community responsibility rejection and environmental responsibility acceptance, Social Impact is partially accepted (Saenz and Ostos, 2020).

2.1. Methods

Research for this paper was conducted using a comparative case study approach (Dubois and Gadde, 2002; Yin, 2017) involving methods mainly consistent with secondary data (reports, videos regarding interviews of the main stakeholders involved, news, official records from the national government, company´s website) qualitative data gathering activities (Patton, 2002). In this case, the main triangulation was in the documents relative to the case (number of documents 20, official reports from government, websites, news, etc.) and the records on public video of interviews with stakeholders (eighteen: six for each case study) who participated directly or indirectly in the projects such as representatives of the government, civil society, and mining industry (Saenz, 2020, 2021).

The case investigation is about oil organizations operating in Peru. The two cases were selected to provide opinions on the results of the Social Impact on hydrocarbon operations in Peru. The following criteria were used to select the instances: first, the provision of secondary records. Second, instances of comparison where the social impact is successful and the other where it fails, knowing how the context influences the strategies of the agency, from techniques that do not suit the agency to techniques that control to get out of social conflict.

Data analysis

For data analysis, secondary information was collected from recent news on the case of conflicts of selected hydrocarbon companies of Repsol and Petroperú at the national level. The main reason for this selection is because these two companies are in the top 5 biggest companies in the industry, PetroPerú sold 4.6 billion USD and Repsol 1.1 billion USD. This information provided great support to the main report of analysts Llerena and Coello (2019), who established a comparison between the strengths and weaknesses that both companies presented when applying the Social Impact and the management of their stakeholders in the situation in which they were presented.

Case studies

In this section, each case study is introduced and described, and the determinants of the company’s strategy (Del Brío & Lizarzaburu, 2018) and the concerns of the community are briefly assessed.

Two representative cases of very recent Social Impact conflicts by oil companies Petroleos del Perú (Petroperú S.A.) and Repsol Exploración Perú S.A that occurred in Peru in 2016 have been taken. One of those shows an alleged expropriation of land not agreed and the other reflects socio-environmental problems that affected both the ecosystem and the population and communities of the area.

About the companies

Repsol is one of the main energy operators in Peru, where it has rights to four oil blocks, three of them in the production stage. It operates Block 57, which started the production of natural gas and associated liquids in March 2014 and is part of the Camisea Consortium in charge of blocks 88 and 56, as well as Block 103 in the exploration stage.

On the other hand, Petroperú S.A is a company owned by the Peruvian State and under private law dedicated to the transportation, refining, distribution, and marketing of fuels and other petroleum products. The most important state company in Peru. They have positioned themselves as the pioneer, leader, and emblematic company of the country.

The first case is the so-called “five basins”, originated in Loreto by the federations of native communities in an area affected by contamination associated with oil exploitation in lots 8 and 192. This conflict began in August 2016 and it has not been clarified. Recent oil spills in the Nor Peruano Pipeline (ONP) in the Loreto region and the environmental impact associated with oil activity in lots 8 and 192 of the last forty years generated great social unrest. These batches represented 20% of the production of crude oil between January and September 2019. On September 1, 2016, the organizations Aconakku, Fepiaurc, Feconat, Oriap, and Fedinapa indigenous peoples called for an indefinite strike (Ávila, 2016). Two strong positions are defending their interests over responsibility for the facts.

Petroperú (s.f.) through a statement indicated that the cause of the spill was due to "a cut in the infrastructure carried out by third parties". The truth is that this is only one of a long list of spills caused by the state company, damaging not only ecosystems but also indigenous people. On the other hand, Humberto Iñapi, apu of the Kukama community, totally rejected what was said by PETROPERÚ, mentioning that there was no intervention by the community members of San Pedro, as it would be illogical for them to harm themselves.

They demanded the paralysis of Station 1 of the ONP during the protest and went to the Saramuro and Saramurillo oil base, in lot 8. The indigenous federations required the following:

Change the pipeline.

Review the contract of Pluspetrol Norte S.A.

Urgently remedy lots 192 and 8.

Approve or create an environmental monitoring law.

Compensate indigenous peoples affected by oil pollution.

Set up a Truth Commission.

Do not criminalize protest.

Table 3.

Summary of case 1.

Table 3.

Summary of case 1.

| Item |

Description |

| Location |

Loreto, Andras and Pastaza Districts: |

| - Uranus |

| - Parinari |

| - Nauta Tigres |

| - Trompeteros |

| Start Date |

August 2016 |

| Primary Actors |

Kukama-Kukamiria Native Communities Association (Aconakku) |

| Federation of indigenous Achuar and Urarine peoples of Rio Corrientes (Fepiauro) |

| Inter-ethnic organization of Alto Pastaza (Oriap) |

| Indigenous Federation of Alto Pastaza (Fedinapa) |

| Indigenous Association for the Development and Conservation os Samiria (Aidecos) |

| Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM) |

| Secondary Actors |

Petroperú S.A. |

| PlusPetrol Norte S.A. |

| Culture Ministry (MINCUL) |

| Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Sanitation (MVCS) |

| Ministry of Education (MINEDU) |

| Ministry of Health (MINSA) |

| Tertiary Actors |

Secretary for Social Management and Dialogue of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (SGSD-PCM) |

| Dialogue and Sustainability of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (ONDS-PCM) |

The conflict in lot 57 originated from a disagreement between the operating company Repsol Exploración Perú SA Sucursal del Perú and the community of Nuevo Mundo over the construction of a compression plant not contemplated in the lease agreement of neighboring lands with the community. The duration of the conflict was five months and it was resolved with a rental contract (Repsol, 2018). According to statements to the press by the community leader, during the period 2005-2016, the water sources were contaminated. After the construction of the plant without consulting the community, the protest and strike began on November 3, 2016.

In an interview with Mongabay Latam, Diego Saavedra, specialist of the NGO Law, Environment and Natural Resources (DAR) indicates that for example, in this case, Repsol has decided to build a gas compression plant and has not consulted the surrounding community that it is New World. It has only requested permission from the Ministry of Energy and Mines and that's it. A tool that the same State has given to extractive companies to modify their projects without the need for consultation or public hearing is what is known as the Technical Sustaining Instrument (ITS), which was promulgated with several decrees that deteriorate oversight environmental in Peru. All of them make up the ‘Paquetazo Ambiental’.

The population of the Nuevo Mundo native community, of the Matsigenka indigenous people, demanded the company Repsol Exploración Perú SA to initiate a negotiation process in which the formulation of land rental contracts is discussed, where it is intended to build a plant of compression as part of the hydrocarbon project that is developed in Block 57. But that is not all. Prior consultation is just one of several complaints that the community has made over the years. “And so, they have been happening (other) environmental impacts such as the problem of water to the town from 2010 to the present; oil spill in the Huitricaya river; and another spill that occurred on May 26, 2014, in the community of Nuevo Mundo", is cited in a document of the native community of Nuevo Mundo.

Table 4.

Summary of the Case 2.

Table 4.

Summary of the Case 2.

| Item |

Description |

| Location |

Nuevo Mundo native community - Megantoni and Echarate district - La Convención province - Cuzco Region |

| Start Date |

October 2016 |

| Finish Date |

February 2017 |

| Primary Actors |

Nuevo Mundo native community |

| Repsol Exploración Perú S.A. |

| Secondary Actors |

Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM) |

| Ministry of Education (MINEDU) |

| Tertiary Actors |

Ombudsman (DP) |

| Dialogue and Sustainability of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (ONDS-PCM) |

| General Office of Social Management of the Ministry of Energy and Mines (OGGS-MINEM) |

3. Results

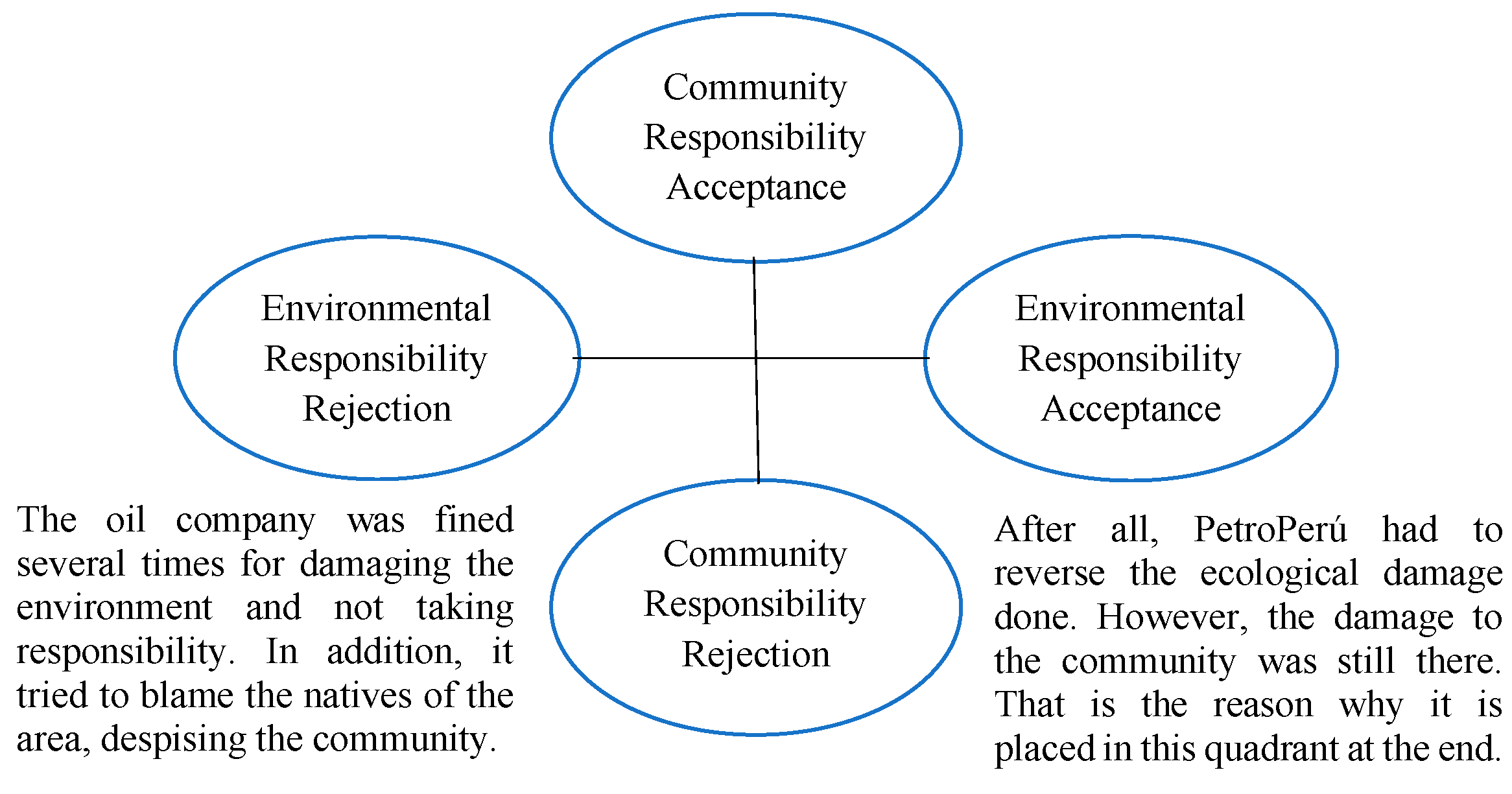

PetroPerú receives a fine of 83 million soles for the oil spill in the Amazon. According to the resolution of the environmental inspection body, the oil company did not carry out maintenance actions on the Norperuano Pipeline. The fine that has now been imposed on PetroPerú - which is equivalent to 20,780.53 UIT (Tax Unit) - presents additional arguments. The document indicates that the state oil company did not take immediate actions to control and minimize the negative impacts caused by the spill that occurred in January 2016 in Chiriaco. The fine was also applied for the actual damage caused to health and flora and fauna, as well as for not taking immediate action to control and minimize the negative impacts caused by the spill. In the beginning, PetroPerú claimed it was an act of sabotage by the communities; however, a report presented to Congress denied that allegation.

This report exhibited the serious health problem within the communities affected by the 2016 spill. At that time, it was reported that the company hired indigenous people to collect the oil without any protection measures and many of those who participated in this dangerous activity were minors (most of those people were exposed to oil with no protection). In

Figure 3, it is shown the case using the framework explained before:

On November 3rd, 2016, the population of the native community of Nuevo Mundo, in the province of La Convention, Cusco region, protested around the gas extraction station of the Repsol company for the construction of a compression plant that would facilitate obtaining the natural resource in the Camisea deposits. The community points out that this plant has not been consulted with the inhabitants, even though it is located meters away from the town. The natives comment that there was no Prior Consultation, despite being indigenous law. Prior consultation is only the tip of the iceberg of the set of complaints made by the community. All the accusations were collected in a memorial addressed to senior public officials.

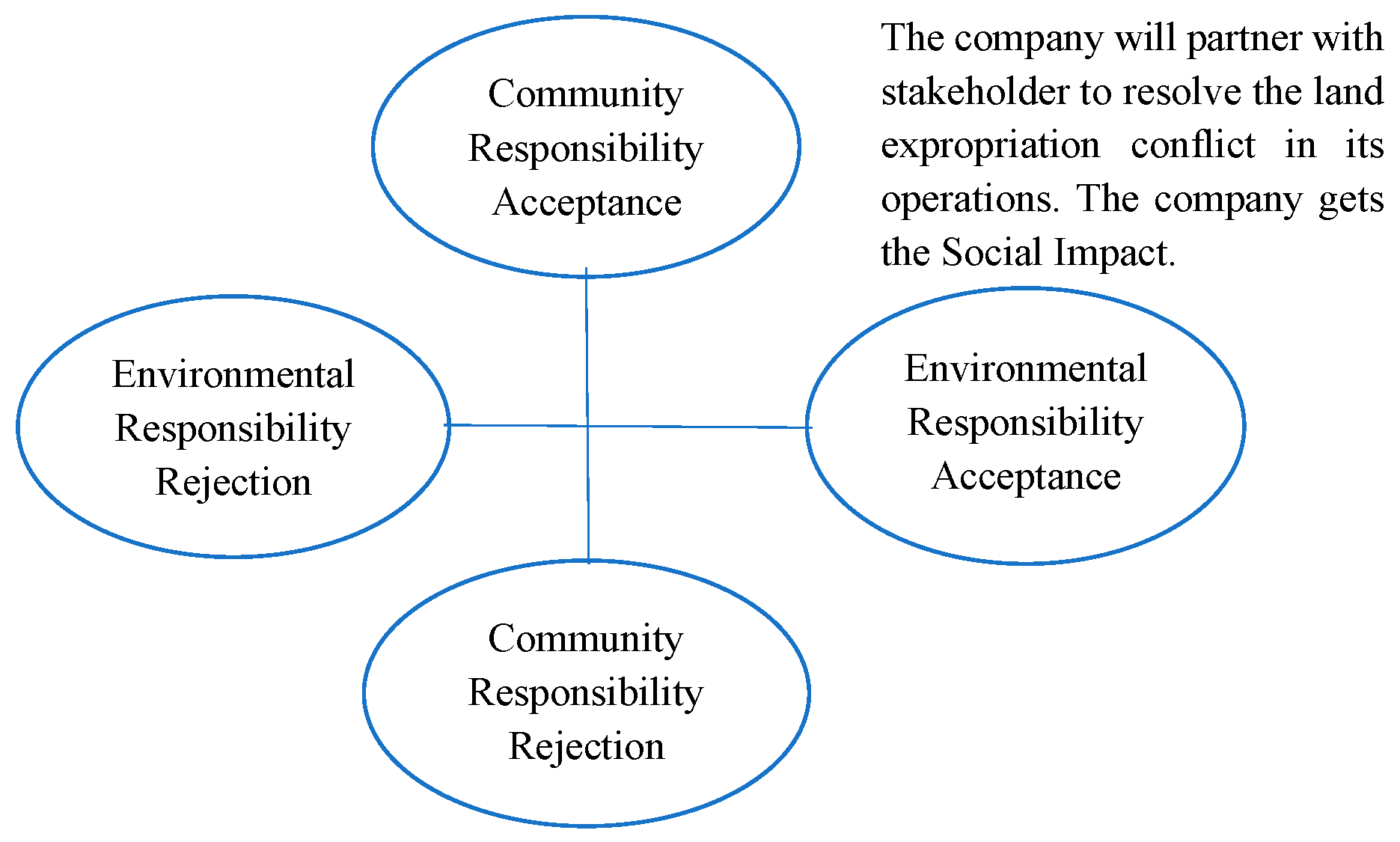

According to statements to the press by the community leader, during the period 2005-2016, the water sources were contaminated. After the construction of the plant without consulting the community, the protests and strikes of November 3 were generated. Some reports reported that similar situations occur in several cases; First, prior consultation is not carried out and several companies only hold a public hearing to inform, but do not consider the decision of the communities. In February 2017, Repsol launched the Sustainable Coexistence Project. The company and the Community of Nuevo Mundo, after an initial controversy and through a process of transparent and participatory dialogue, reached an agreement. The General Assembly of the Nuevo Mundo Community endorsed this agreement, before the completion of the activities necessary for the development of the Sagari field and the Compression Plant. The agreement included aspects of interest concerning local development projects, land use compensation, and the hiring of local labor.

The operational challenges of the project have very ambitious goals that allow reducing the impact and maximizing the opportunities.

Strengthen the social management system, improving processes based on a greater knowledge of the context.

Generate measurable benefits and promote multi-stakeholder collaboration in social investment projects.

Contribute to the empowerment of the Community's environmental monitoring and supervision teams, promoting the exchange of reliable information.

Develop capacities for negotiation under fair conditions and of mutual interest in the communities.

The company’s strategy was to participate in a dialogue table to determine an alternative to reduce environmental impacts and improve social benefits for the communities to earn Social Impact. The following

Figure 4 shows this analysis.

This initiative has a win-win relationship where both parties win. Where through negotiations, acceptance of responsibilities, and dialogue, the conflict was resolved with a social impact. See

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

The two empirical cases study a process where there were social conflicts at the early stage, and then the company presented a solution to get Social Impact. However, the source of the social conflicts varied in each case study from social concerns (Case 1: Petroperú), to environmental concerns (Case 2: Repsol). We can observe a clear example when a company assumes responsibility for the facts compared to another that decides to absorb and accuse third parties of criminal acts without the presentation of conclusive evidence. However, it should also be noted that the complexity of the Repsol case was less than that of Petroperú since the former did not represent any environmental conflict, just a problem of specification in the rental of the land. In the first case, Petroperú, the state company that operates the pipeline, said at that time and on other occasions that the spill was again linked to an act of vandalism. The community was not convinced by this version and did not allow the cleaning work to begin until the representatives of the prosecution inspected it in the presence of their leaders. CSR strategies can be represented in

Figure 6.

In the second case, the community members took more direct protest measures (taking the camp) on one occasion, the dialogue was only suspended in one of the five months that the conflict lasted (December 2016), and the need for the issuance of any regulations or the active and constant intervention of government authorities.

For many years, the emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) included in company strategies has been a subject of study. CSR participation in these strategies plays such roles as a marketing element, providing legitimacy and positive impressions, improving the company's reputation, and generating competitive advantage (Lopez, 2016).

To sum up these study cases, it was shown based on the 4-quadrant model, that is highly important to be placed on the top right, because for several reasons: the community will let you get in again, exploit again, work freedom, etc. And CSR is a fundamental tool here. It works as a way to calm the community and let them know that the oil company is by their side: hiring them, making an investment in local cities, building schools, etc. Furthermore, the corporate image will end up less damaged. Repsol did a good job, despite the different circumstances (remember that no community is homogenous). On the other hand, Petroperú tried to demonstrate to society that it was not guilty, without using CSR as a tool for getting closer to the community. And as was expected, the result was not so good and its image was depleted.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this research is to determine how is the relationship between CSR and Social Impact, and the findings show that there are different states of this relationship (Lock and Seele, 2015). According to Suopajärvi and Kantola (2020) and Dunbar et al. (2020) oil companies should focus on community responsibility, environmental responsibility, and stakeholder engagement to get Social Impact, otherwise, if they fail in one or both responsibilities, Social Impact is partially accepted or withdrawn. Let's remember what happened in the case study of Petroperú and Repsol.

This research results essentially in the Peruvian context because the local territory has a privileged location that offers a myriad of possibilities for any kind of investment (including that Peru is an investment-grade country) (E&Y, 2018). Promote the oil industry is of utmost importance because this industry had been growing near to 5% per year in the first 15 years of this century; however, in the last 5 years Oil production has an average of -3.25% as of September 2020 (BCRP, 2020). The oil industry is currently contributing 1.5% to the Peruvian GDP, in 2018 was 3.6% and in that year, it gave USD 37.7 billion to the fiscal income. So, Peru is losing participation in Latam Region (also compared with Pacific Alliance). This is making that the Oil industry investment in CSR will also be reduced; being more affecting the local communities. On this side, this paper looks to foster lawmakers to create more and better laws to foment the Oil & Gas industry.

Low and Siegel (2019) consider that CSR has seven core subjects (the environment, consumers, labor practices, governance, community, human rights, and fair operating practice) and the stakeholders' engagement as a fundamental part of social responsibility; however, Social Impact shows that community responsibility, environmental responsibility, and engagement are the most important key topics to be considered for a mining company (Peng et al., 2020; Frederiksen, 2019; Camargo et al., 2019).

Communities are not homogeneous (Mikusiński and Niedziałkowski, 2020). They are made up of many different groups, with different concerns and expectations (Conde and Le Billon, 2017). So, CSR areas in oil companies should study each community and not as a whole. This means oil companies need to work collaboratively with stakeholders to identify concerns and give them solutions (Lin et al., 2019). Engagement and dialogue are means to find solutions through community responsibility and environmental responsibility strategies just like in the mining industry (Dalla Porta, 2019).

This study also has several limitations. It focuses on the relationship between CSR strategies to get Social Impact. In addition, the article is largely descriptive, and empirical research is limited to case examples taken from the Peruvian experience and shows why it is important to pay attention to the oil industry. I suggest that future research studies this relationship in other industries such as mining, energy, etc. Additionally, empirical studies could delve deeper into whether the company’s strategy depends on how the community is organized.

References

- Ali, S.S.; Kaur, R. Effectiveness of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in implementation of social sustainability in warehousing of developing countries: A hybrid approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Moggi, S.; Caputo, F.; Rosato, P. Social media as stakeholder engagement tool: CSR communication failure in the oil and gas sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, Y. T. (2020). An Overview of Corrosion in Oil and Gas Industry: Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream Sectors. Corrosion Inhibitors in the Oil and Gas Industry, 1-39.

- BCRP (November, 2020) Producción Hidrocarburos (var%12 meses). Retrieved from https://estadisticas.bcrp.gob. 0188.

- Camargo, H.E.; Azman, A.S.; Peterson, J.S. Engineered Noise Controls for Miner Safety and Environmental Responsibility. In Advances in Productive, Safe and Responsible Coal Mining; Hirschi, J., Ed.; 2018; pp. 215–244.

- Conexion Esan (). Project stakeholders: their impact on the organization https://www.esan.edu. 7 February 2020.

- Conde, M. , & Le Billon, P. (2017). Why do some communities resist mining projects while others do not? The Extractive Industries and Society, 4(3), 681-697. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Porta, M. P. (2019). The Coercion/Dialogue Paradox in Mining Conflicts in Argentina and Peru (Doctoral dissertation, The New School).

- Del Brío, J. .; Bolaños, E.L. CSR Actions in Companies and Perception of Their Reputation by Managers: Analysis in the Rural Area of an Emerging Country in the Banking Sector. Sustainability 2018, 10, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Brío, J.; Bolaños, E.L. Effects of CSR and CR on Business Confidence in an Emerging Country. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defensoría del pueblo () La Defensoría del Pueblo registró 212 conflictos sociales, la mayoría por problemas socioambientales. Recovered from: https://www.defensoria.gob. 21 November.

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, M. N. , & Winniford, W L. ( 2020). Environmental Impact of Emissions Originating from the Petroleum Industry. Analytical Techniques in the Oil and Gas Industry for Environmental Monitoring. 347–378. [CrossRef]

- Earnst & Young (2018). Peru’s Oil & Gas Investment Guide 2019/2020. Retrieved from https://www.perupetro.com.pe/wps/wcm/connect/corporativo/b8b712bd-d2cd-4136-805d-d3593cf2da9a/EY+Peru%27s+Oil+and+Gas+Business+and+Investment+Guide+2019-2020.pdf? 2020.

- Escrig, E. , Rivera, J., Muñoz, M. & Fernández, M. (2017). Integrating multiple ESG investors' preferences into sustainable investment: A fuzzy multicriteria methodological approach. Journal of cleaner production, 162, 1334-1345. [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility: the Role of Formal Strategic Planning and Firm Culture. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches Garcíia, A.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, C.D.; Demir, E.; Díez-Esteban, J.M.; Bolaños, E.L. Corruption, national culture and corporate investment: European evidence. Eur. J. Finance 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarpour, T.; Gustafsson, A. How do corporate social responsibility (CSR) and innovativeness increase financial gains? A customer perspective analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 140, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.J. Profits and Principles: Four Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethic- 2002, 35, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Smid, H. Reconsidering the relevance of social license pressure and government regulation for environmental performance of European SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, D.; Kagan, R.A.; Gunningham, N. When Social Norms and Pressures Are Not Enough: Environmental Performance in the Trucking Industry. Law Soc. Rev. 2009, 43, 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, S.S.; Daraee, M.; Sobat, Z. Advanced development in upstream of petroleum industry using nanotechnology. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.A.; Nysten-Haarala, S.; Tulaeva, S.; Tysiachniouk, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Oil Industry in the Russian Arctic: Global Norms and Neo-Paternalism. Eur. Stud. 2016, 68, 1340–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. S. , & Robinson, P. R. (2019). Midstream Transportation, Storage, and Processing. In Petroleum Science and Technology (pp. 385-394). Springer, Cham.

- Ike, M.; Donovan, J.D.; Topple, C.; Masli, E.K. A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability from a management viewpoint: Evidence from Japanese manufacturing multinational enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinejad, S. (2016) Control and treatment of sulfur compounds especially sulfur oxides (SOx) emissions from the petroleum industry: A review. Chemistry International.

- Jaworska, S. Change But no Climate Change: Discourses of Climate Change in Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in the Oil Industry. J. Bus. Commun. 2018, 55, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Does It Really Pay to Be Green? An Empirical Study of Firm Environmental and Financial Performance: An Empirical Study of Firm Environmental and Financial Performance. J. Ind. Ecol. 2001, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirat, M. Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas industry in Qatar perceptions and practices. Public Relations Rev. 2015, 41, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M.; Talias, M.A. Corporate Sustainability Strategies and Decision Support Methods: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; McKenna, B.; Ho, C.M.; Shen, G.Q. Stakeholders’ influence strategies on social responsibility implementation in construction projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-X.; Wu, M.; Jia, F.-R.; Yue, Q.; Wang, H.-M. Material flow analysis and spatial pattern analysis of petroleum products consumption and petroleum-related CO2 emissions in China during 1995–2017. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 209, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena, M.; Coello, F. (2019). Conflictos sociales en la industria de hidrocarburos del Perú: análisis de dos casos representativos. Documento de Trabajo N o 46, Gerencia de Políticas y Análisis Económico – Osinergmin, Perú.

- Lock, I.; Seele, P. Analyzing Sector-Specific CSR Reporting: Social and Environmental Disclosure to Investors in the Chemicals and Banking and Insurance Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 22, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J. , Ortega I. & Ortiz I. (2017). Strategies of corporate social responsibility in Latin America: a content analysis in the extractive industry. AD-minister N, Medellin-Colombia.

- López, M. () Perú: cinco claves para entender el conflicto entre la comunidad de Nuevo Mundo y Repsol en Camisea. Recovered from: https://es.mongabay. 10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Low, M. P. , & Siegel, D. (2019). A bibliometric analysis of employee-centered corporate social responsibility research in the 2000s. Social Responsibility Journal.

- Lozano, R. (2015). A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability drivers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 32-44. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. , & von Haartman, R. (2018). Reinforcing the holistic perspective of sustainability: analysis of the importance of sustainability drivers in organizations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(4), 508-522.

- Meesters, M.E.; Behagel, J.H. The Social Licence to Operate: Ambiguities and the neutralization of harm in Mongolia. Resour. Policy 2017, 53, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikusiński, G. , & Niedziałkowski, K. (2020). Perceived importance of ecosystem services in the Białowieża Forest for local communities–Does proximity matter? Land Use Policy, 97, 104667.

- Minería y Energía (, 2020). Los Hidrocarburos en el Perú: Su impacto en la economía nacional y regional. Retrieved from https://mineriaenergia. 2 September.

- Nataly Aya, Pastrana, & Krishnamurthy, Sriramesh. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Perceptions and practices among SMEs in Colombia.

- Nelsen, J.L. (2006). Social license to operate. Int. J. Mining Reclam. Environ. 20, 161e162. [CrossRef]

- Owuso, S. M., Poi. The Effect of Risk Mitigation Strategy on Sales Performance of Petroleum Marketing Firms in the Downstream Sector of the Petroleum Industry in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Business Management 2019, 5(3), 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative social work, 1(3), 261-283. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Lacey, J.; Moffat, K. Petroperú (s.f.) Remediación ambiental del Oleoducto Norperuano (ONP). Recovered from: https://www.petroperu.com.pe/socio-ambiental/principal/gestion-ambiental/remediacion-ambiental-del-oleoducto-norperuano-onp-preguntas-frecuentes/ Resour. Policy 41, 83e90. Resour. Policy 2014, 41, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Tang, P.; Yang, S.; Fu, S. How should mining firms invest in the multidimensions of corporate social responsibility? Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2020, 65, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 247, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repsol () Proyecto convivencia sostenible. Recovered from: https://www.repsol.com/es/sostenibilidad/casos-de-exito/proyecto-convivencia-sostenible/index. 19 July.

- Cesar, S.; Jhony, O. Corporate Social Responsibility supports the construction of a strong social capital in the mining context: Evidence from Peru. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and the social licence to operate: A case study in Peru. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C. Keeping up with the flow: Using multiple water strategies to earn social license to operate in the Peruvian mining industry. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, C.; Biffignandi, S.; Bianchi, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Through Twitter: From Topic Model Analysis to Indexes Measuring Communication Characteristics. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 1217–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suopajärvi, L. , & Kantola, A. (2020). The social impact management plan as a tool for local planning: Case study: Mining in Northern Finland. Land Use Policy, 93, 104046. [CrossRef]

- Warhurst, A. (2001). Corporate citizenship and corporate social investment: drivers of tri-sector partnership. J. Corp. Citizsh.1,57–73.

- Whellams, M. (2007). The role of CSR in development: A case study involving the mining industry in South America.

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications.

- Yin, W.; Zhu, Z.; Kirkulak-Uludag, B.; Zhu, Y. The determinants of green credit and its impact on the performance of Chinese banks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 286, 124991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yousaf, H.A.U. Green supply chain coordination considering government intervention, green investment, and customer green preferences in the petroleum industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 246, 118984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).