Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Water resources and the Sustainable Development Goals

1.2. Remote sensing for monitoring water resources

2. Materials and Methods

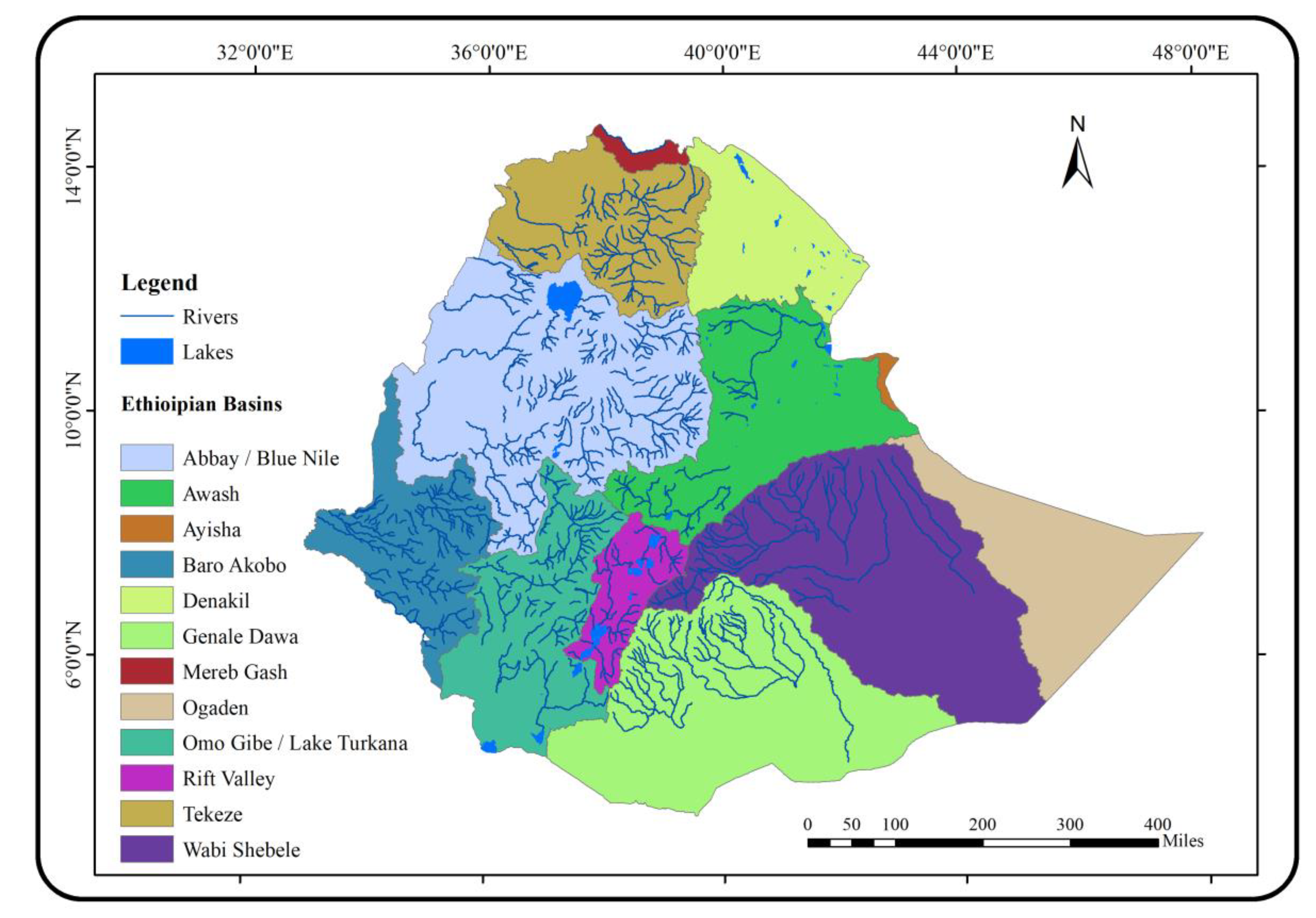

2.1. Description of the study area

2.2. Surface water extraction

3. Results

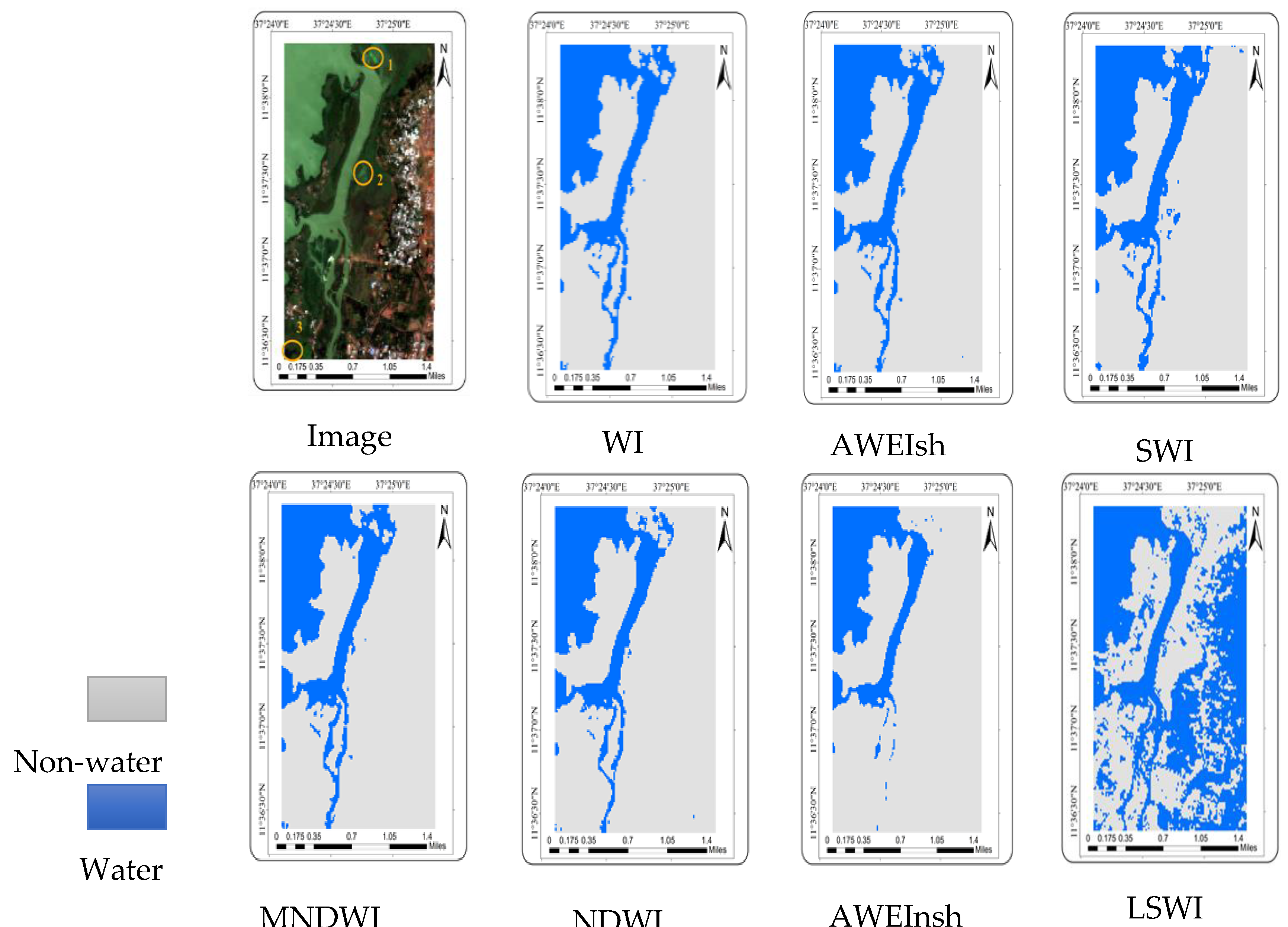

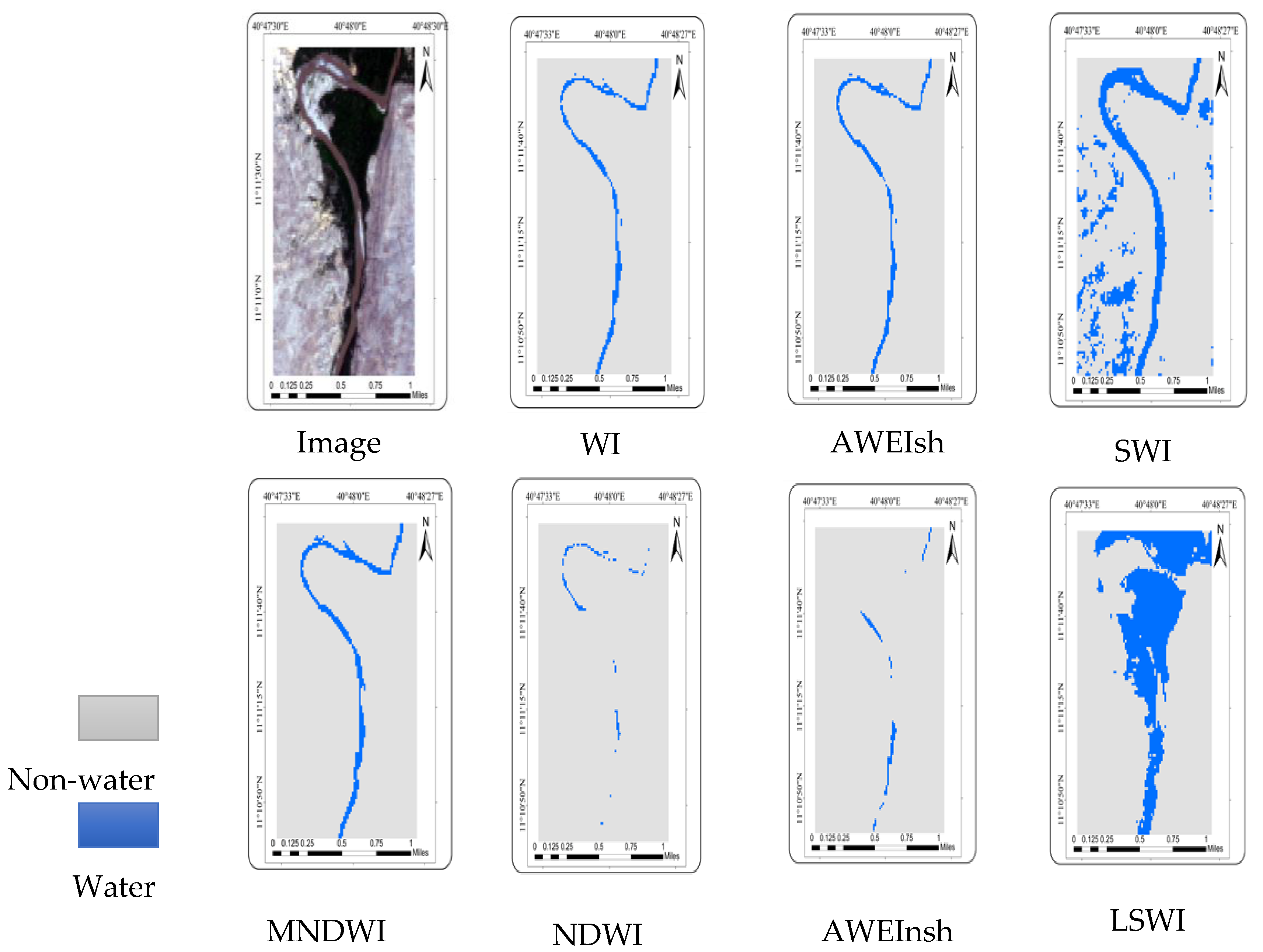

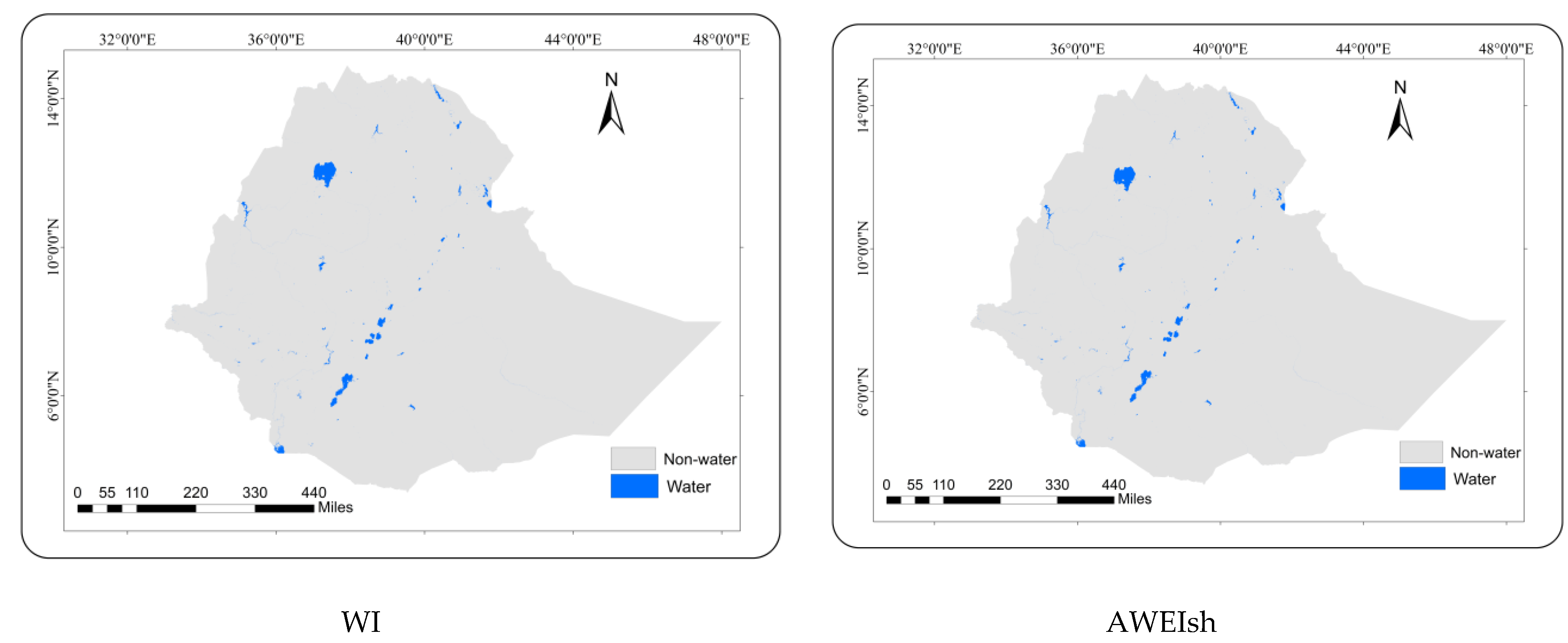

3.1. Visual assessment of water indices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Pekel, J. F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A. S. High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes. Nature, 2016, 540, 418–422. [CrossRef]

- Vandas, S.; Winter, T.C.; Battaglin, W,A. Water and the Environment. American Geosciences Institute Environmental Awareness, 2002, 20-23.

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A. H.; Gessner, M. O.; Kawabata, Z. I.; Knowler, D. J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R. J.; Prieur-Richard, A. H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M. L. J.; et al. Freshwater Biodiversity: Importance, Threats, Status and Conservation Challenges. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 2006, 163–182. [CrossRef]

- Zedler, J. B.; Kercher, S. Wetland Resources: Status, Trends, Ecosystem Services, and Restorability. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2005, 39–74. [CrossRef]

- Brauman, K. A. Hydrologic Ecosystem Services: Linking Ecohydrologic Processes to Human Well-Being in Water Research and Watershed Management. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 2015, 2, 345–358. [CrossRef]

- Chahine, M. T. The Hydrological Cycle and Its Influence on Climate. Nature, 1992, 359, 373-380.

- Tranvik, L. J.; Downing, J. A.; Cotner, J. B.; Loiselle, S. A.; Striegl, R. G.; Ballatore, T. J.; Dillon, P.; Finlay, K.; Fortino, K.; Knoll, L. B.; et al. Lakes and Reservoirs as Regulators of Carbon Cycling and Climate. Limnology and Oceanography, 2009, 54, 2298–2314. [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C. J.; Green, P.; Salisbury, J.; Lammers, R. B. Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth. Science, 2000, 289, 284-288. [CrossRef]

- Collen, B.; Whitton, F.; Dyer, E. E.; Baillie, J. E. M.; Cumberlidge, N.; Darwall, W. R. T.; Pollock, C.; Richman, N. I.; Soulsby, A. M.; Böhm, M. Global Patterns of Freshwater Species Diversity, Threat and Endemism. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2014, 23, 40–51. [CrossRef]

- Morss, R. E.; Wilhelmi, O. v.; Downton, M. W.; Gruntfest, E. Flood Risk, Uncertainty, and Scientific Information for Decision Making: Lessons from an Interdisciplinary Project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 2005, 86, 1593–1601. [CrossRef]

- Giardino, C.; Bresciani, M.; Villa, P.; Martinelli, A. Application of Remote Sensing in Water Resource Management: The Case Study of Lake Trasimeno, Italy. Water Resources Management, 2010, 24, 3885–3899. [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D. Sustainable Development Goals for People and Planet. Nature, 2013, 495, 1-3.

- CBD. Convention on Biological Diversity for Aichi Biodiversity Targets, 2010. http://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/.

- Dickens, C.; Rebelo, L. M.; Nhamo, L. Guidelines and indicators for Target 6.6 of the SDGs: Change in the extent of water-related ecosystems over time. Report by the International Water Management Institute. CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land, and Ecosystems (WLE), 2017, 4-10.

- Berhanu, B.; Seleshi, Y.; Melesse, A. M. Surface Water and Groundwater Resources of Ethiopia: Potentials and Challenges of Water Resources Development. Nile River Basin: Ecohydrological Challenges, Climate Change and Hydropolitics, Springer International Publishing, 2014, 97–117. [CrossRef]

- Dile, Y. T.; Tekleab, S.; Kaba, E. A.; Gebrehiwot, S. G.; Worqlul, A. W.; Bayabil, H. K.; Yimam, Y. T.; Tilahun, S. A.; Daggupati, P.; Karlberg, L.; et al. Advances in Water Resources Research in the Upper Blue Nile Basin and the Way Forward: A Review. Journal of Hydrology, 2018, 407–423. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Flood, N.; Danaher, T. Comparing Landsat Water Index Methods for Automated Water Classification in Eastern Australia. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 175, 167–182. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.; Lewis, A.; Roberts, D.; Ring, S.; Melrose, R.; Sixsmith, J.; Lymburner, L.; McIntyre, A.; Tan, P.; Curnow, S.; et al. Water Observations from Space: Mapping Surface Water from 25 Years of Landsat Imagery across Australia. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 174, 341–352. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2017, 202, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ni, Y.; Pang, Z.; Li, X.; Ju, H.; He, G.; Lv, J.; Yang, K.; Fu, J.; Qin, X. An Effective Water Body Extraction Method with New Water Index for Sentinel-2 Imagery. Water, 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J. H.; Won, J. S.; Duck Min, K. Waterline Extraction from Landsat TM Data in a Tidal Flat A Case Study in Gomso Bay, Korea. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2002, 83, 442–456.

- McFeeters, S. K. The Use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the Delineation of Open Water Features. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 1996, 17 (7), 1425–1432. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI) to Enhance Open Water Features in Remotely Sensed Imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Boles, S.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, D.; Liu, M. Waterline Extraction from Landsat TM Data in a Tidal Flat A Case Study in Gomso Bay, Korea. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2002, 83 442–456.

- Feyisa, G. L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S. R. Automated Water Extraction Index: A New Technique for Surface Water Mapping Using Landsat Imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2014, 140, 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhang, L.; Wylie, B. Analysis of Dynamic Thresholds for the Normalized Difference Water Index. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, 2009, 75, 1307–1317. [CrossRef]

- Sentinel. Sentinel-2 MSI User Guide. https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/web/sentinel/user-guides/sentinel-2-msi, Accessed 4 December 2022.

- Lillesand, T. M.; Kiefer, R. R. W.; Chipman, J. W. Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation. 6th ed. New York: Wiley, 2008.29. Sisay, A. Remote Sensing Based Water Surface Extraction and Change Detection in the Central Rift Valley Region of Ethiopia. In Int. J. of Sustainable Water and Environmental Systems, 2017, 9,1, 01-07.

- Liu, H.; Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, W.; Yin, X. A Comparison of Different Water Indices and Band Downscaling Methods for Water Bodies Mapping from Sentinel-2 Imagery at 10-M Resolution. Water, 2022, 14, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Driscol, J.; Sarigai, S.; Wu, Q.; Lippitt, CD.; Morgan, M. Towards Synoptic Water Monitoring Systems: A Review of AI Methods for Automating Water Body Detection and Water Quality Monitoring Using Remote Sensing. Sensors, 2022, 22, 6, 1-48. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/6/2416.

- Li, J.; Ma, R.; Cao, Z.; Xue, K.; Xiong, J.; Hu, M.; Feng, X.. Satellite detection of surface water extent: A review of methodology. Water, 2022, 14, 7, 1-18. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/7/1148.

| Index | Index name | Source | Equation |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index | McFeeters (1996) | |

| MNDWI | Modified Normalized Difference Water Index | Xu (2006) | |

| AWEInsh | Automated Water Extraction Index non shadow | Feyisa et al. (2014) | (4*(Green-SWIR1))-(0.25*NIR+(2.75*SWIR2)) |

| AWEIsh | Automated Water Extraction Index shadow | Feyisa et al. (2014) | (Blue+2.5*Green-1.5*(NIR+SWIR1)-0.25*SWIR2) |

| WI | Water Index | Fischer et al. (2015) | (1.7204+171*Green+3*Red-70*NIR-45*SWIR1-71*SWIR2) |

| SWI | Sentinel Water Index | Jiang et al. (2021) | |

| LSWI | Land Surface Water Index | Xiao et al. (2002) |

| Producer acc | Producer acc | User acc | User acc | Overall acc | Kappa coeff | |

| Water | Non-water | Water | Non-water | |||

| NDWI | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| MNDWI | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| AWEInsh | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| AWEIsh | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| WI | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| SWI | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| LSWI | 0.3 | 0.91 | 0.37 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).