1. Introduction

The use and importance of video conferencing systems are rapidly increasing in industry and academia due to the preference for a remote environment. Security vulnerabilities in video conferencing systems have been exposed as their usage has increased. Hence, end-to-end encryption (E2EE) stands out as one of the most pressing needs for enhancing security in video conferencing systems. E2EE ensures that when two entities communicate, the contents of the message remain concealed from anyone except the intended recipient, preserving their confidentiality [

1].

In order to address security vulnerabilities, video conferencing systems are currently implementing E2EE security measures. Zoom, a popular video conferencing system in recent times, currently offers two phases of E2EE security and has plans to gradually implement it across four phases. Additionally, they consistently share E2EE security updates through whitepapers on their website [

2].

Discussions on security services for video conferencing systems are actively progressing in the international standardization process for various technologies.

A representative example is the Secure Frame (SFrame), which is currently undergoing standardization. SFrame is a group communication protocol that applies E2EE security to a web real-time communication (WebRTC) protocol that enables real-time communication. It provides E2EE security by applying a double encryption method to prevent the exposure of message information to a selective forwarding unit (SFU), an intermediate communication [

3]. This group communication protocol has gained attention for significantly reducing communication overhead, a problem with E2EE. SFrame is currently applied and used in video conferencing systems such as Google Duo and Cisco Webex [

4].

In this study, the E2EE-related protocols of Zoom and SFrame were investigated. Also, a detailed comparison between the two systems was conducted. The discussion focuses on the E2EE protocols in a video conferencing system based on the Government Public Key Infrastructure (GPKI), which are known for robust reliability compared to authentication mechanisms used in the private sector. In particular, we propose a specific protocol that uses the key encapsulation mechanism (KEM) of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) for exchange user keys in GPKI-based video conferencing system. The proposed protocol does not expose the key to central server because it securely shares the key through PQC KEM when user entering a video conference. This protocol effectively fulfills authenticity, confidentiality, and integrity which are the E2EE security requirements [

5].

In section 2, the research trends and security requirements regarding E2EE security are explored, and include an investigation into the security vulnerabilities of Zoom. In section 3, an analysis is conducted on the key management system presented in Zoom’s E2EE whitepaper.

Section 4 describes the structure related to the E2EE function of SFrame and the E2EE security key management system, messaging layer security (MLS).

Section 5 discusses the E2EE protocol in the government user authentication mechanism and the GPKI-based authentication system. We propose a protocol that applies PQC KEM to the user key exchange process, and based on this, we construct a next-generation video conferencing system with an E2EE security function. Finally,

Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Research Trends

2.1. E2EE-related Research

Since non-face-to-face environments are becoming more prevalent, there is an increase in usage of online video conferencing systems. As a result, the importance of security technology for protecting the privacy of entities is receiving attention. However, a problem may occur in which privacy information of entity is exposed to a central server when video conferencing information is transmitted. A concept that has emerged to improve for this problem is E2EE, that is, an encryption technology for protecting the privacy of entities. If E2EE technology is applied to encrypt using a key that shared only by entities who are communication parties, entities privacy is protected because messages cannot be verified except entities.

On the other hand, there are several practical barriers to the actual application and deployment of E2EE technology. The most significant obstacle is when the communicating party does not utilize a reliable Certification Authority (CA)'s Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) during the secret key generation process and instead relies on an unreliable third party as a server. This compromises the privacy of the entities as the third party gains access to the secret key information, rendering the E2EE security function ineffective. Apart from the security issues arising from the perspective of E2EE, the following obstacles should also be taken into consideration [

1].

Despite these obstacles, E2EE security needs to be applied for the secure of the entity’s video conferencing system. Furthermore, entities need to check if system has applied E2EE security.

As a representative protocol with E2EE security, the Signal Protocol applied to various message applications is a cryptographic protocol that provides E2EE security for word, voice, and video encryption. This protocol has five features, Immediate Decryption, Long-lived Sessions, Usability, Forward Secrecy, Post-Compromise Security [

1].

The communication parties of the Signal Protocol receive messages immediately and decryption without loss or delay is possible. To this end, the Signal Protocol has a feature that maintains the session between communication parties until they reinstall an application or change the device. In addition, the protocol has usability because it does not use its own password or PKI by CA. Forward secrecy refers to the feature that even if a user in the group is attacked and the group secret key is exposed, the attacker cannot decrypt the message before the attack. Contrary to Forward Secrecy, Post-Compromise Security refers to the feature that an attacker cannot decrypt messages after a user has been attacked. Therefore, Post-Compromise Security is also referred to as Future Secrecy.

E2EE security requirements, including Forward Secrecy and Post-Compromise Security features, are defined according to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standardization document [

5]. In this document, the requirements for E2EE security are devided into necessary and optional features, as summarized in

Table 1.

E2EE must satisfy the following three requirements: authenticity, confidentiality, and integrity. There are additional features that enhance E2EE security and contribute to its effectiveness. There are seven conditions, including forward secrecy and post-compromise security, provided by the Signal Protocol.

Cisco Webex video conference application provides E2EE security. They securely exchange the shared meeting key based on MLS and encrypt meeting content using SFrame. They claim the security model of Webex. Also, a video conference data exchanged securely that encryption to use of specific ciphersuites. They have described their strategy in the whitepaper [

6].

On the other hand, Cisco Webex has presented a roadmap to implement Zero Trust-based E2EE. The roadmap consists of two phases: Phase 1 and Phase 2. In Phase 1, they plan to deploy a E2EE using standard based cryptography with SFrame and MLS. Phase 2 involves adding a method to verify end-to-end verified identity based on the automatic certificate management environment (ACME) protocol, which is a certificate authority structure [

7]. ACME supports extensions for various identifiers in different PKI contexts. Additionally, ACME can automate certain aspects of certificate management, even if some non-automated processes are still required [

8].

2.2. Vulnerable case of Video Conferencing System Security

Various video conferencing systems are being launched worldwide. Notable video conferencing systems include Zoom, Cisco Webex, Facebook, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet. Among them, the average number of Zoom users in 2020 increased by over 40 times compared to 2019 [

9].

However, as the number of Zoom users rapidly increased and began to attract attention, the number of attackers threatening security also increased. Zoom has been subject to several attacks by attackers; particularly, Zoom membership privacy has been leaked to the dark web and Zoom Bombing/Zoom Trolling, which disrupts meetings, such as hacking the screen, has become common.

In addition to intentional attacks, Zoom has experienced various security vulnerability issues. Zoom was also aware of it, and took measures such as upgrading the encryption algorithm to AES-256-GCM or adding a 2-Factor Authentication method to solve it [

9]. Although Zoom has addressed most of the vulnerabilities, E2EE function has only been partially addressed. Currently, the E2EE security features provided by Zoom have only been implemented up to phase 2 out of a total of 4.

3. Analyzing Zoom’s E2EE Capabilities

Zoom plans to provide E2EE security by subdividing it into four phases. According to Zoom’s E2EE whitepaper [

2], E2EE security features have been specified in up to two phases. Zoom’s E2EE security plan is as follows:

Phase 1: Client Key Management

Phase 2: Identity Check

Phase 3: Transparency Tree

Phase 4: Real-Time Security

Phase 1 of Zoom’s E2EE involves Client Key Management. Client Key Management is a system designed to securely distribute the meeting key () among the entities (clients) participating in a meeting, enabling them to encrypt and decrypt meeting data. E2EE Phase 2 is an Identity Check. In Phase 1, the identity status of each client was based on the displayed screen name during the meeting, while in Phase 2, the client's identity status was traced using Sigchain. By reviewing the record of the client's identity status during the meeting, it became possible to prevent attacks from suspicious devices.

Zoom’s E2EE phases 3 and 4 have not been applied and are planned for application in the future. Phase 3 introduces the transparency tree, which expands the authentication assurance to enable all clients in the conference to verify devices and keys. Phase 4 involves real-time security, which strengthens meeting security through additional signatures and enables client Sigchain verification without passing through the Zoom Server.

In

Section 3, we analyze Client Key Management, which is the first step in E2EE security. The details and plans for the remaining phases of Zoom’s E2EE security are included in Zoom’s E2EE whitepaper [

2].

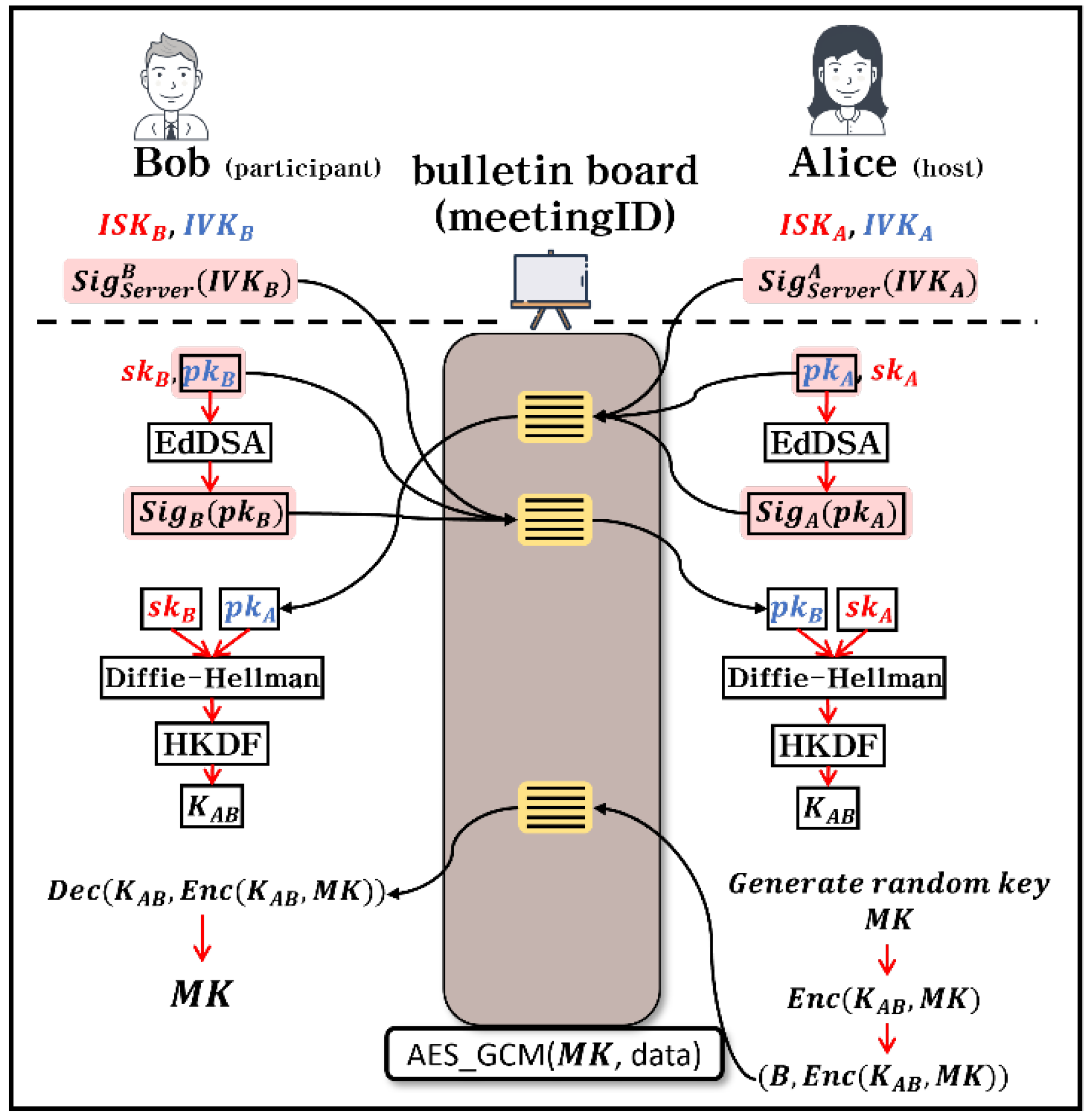

3.1. E2EE Phase 1: Client Key Management

A Zoom meeting typically comprises a host, who initiates and manages the meeting, and participants who join the meeting. First, assume that Alice (host) and Bob (participant) explain the Client Key Management system of Zoom. Additionally, it is assumed that both entities possess a long-time signing key (

) and a long-time verification key (

). Based on the above conditions, the process of Zoom’s Client Key Management system is illustrated in

Figure 1. [

2].

We describe progress of the

Figure 1. to Algorithm 1.:

When each client log-in to Zoom, the Zoom server generates a signature () for each client’s verification key (). (Algorithm 1., Line 1)

Each client generates a temporary encryption key pair, public key, and secret key (). Each client generates a signature () with EdDSA, after that uploads the public key (), signature (), and signature for the verification key () to the bulletin board. (Algorithm 1., Line 2 - 6)

To generate a symmetric key () for the encryption/decryption of the meeting key (), the host (Alice) performs the Diffie-Hellman between the public key () of the verified participant (Bob) and its own private key (). Subsequently, these keys are used as inputs to the HKDF function. The participant (Bob) uses own private key () and the host’s public key () to generate a symmetric key () in a similar manner. (Algorithm 1., Line 8, 12)

The host generates a 32-byte shared meeting key () that is used to encrypt and decrypt the meeting data using AES-GCM. The meeting key is generated using a cryptographically secure random number generator (RNG). The host then encrypts it with the symmetric key (), uploads it to the bulletin board, decrypts the ciphertext with the symmetric key (), and obtains the meeting key (). (Algorithm 1., Line 9, 10, 13)

|

Algorithm 1. E2EE Key Exchange Process of Zoom. |

: Alice(host),: Bob(client),: public key,: secret key,: verification key, : signing key,: shared meeting key,: signature for public key,

: symmetric key for enc/dec,

: signature of the server for verification key |

| 1: For user , do Zoom server ▷, signs in, |

| 2: procedure (Zoom’s E2EE Key Exchange) |

| 3: For user , do ▷ |

| 4: (,)KeyGen

|

| 5: EdDSA() |

| 6: bulletin board{,,} |

| 7: For user do

|

| 8: HKDF(Diffie-Hellman(, )) |

| 9: Secure RNG

|

| 10: bulletin boardEnc(,) |

| 11: For user do

|

| 12: HKDF(Diffie-Hellman(, )) |

| 13: Dec(, Enc(,)) |

| 14: end procedure

|

Otherwise, if a new participant Charlie joins to Key Management System as mentioned above, which includes Alice and Bob, the following steps are additionally performed. It is assumed that Charlie possesses a long-time signing key () and a long-time verification key ().

Zoom server generates a signature () for Charlie’s verification key (). After that, Charlie generates a temporary encryption key pair (), and a signature () with EdDSA. Then Charlie uploads the public key (), signature (), and signature for the verification key () to the bulletin board.

To generate symmetric key (), Alice performs the Diffie-Hellman between the public key () and its own private key (). Charlie uses own private key () and the Alice’s public key () to generate the symmetric key () similarly.

Alice generates a new 32-byte shared meeting key (). Then Alice encrypts it with each symmetric key (,), uploads it to the bulletin board. After that, Bob and Charlie can decrypt the ciphertext with each symmetric key (,), and obtains the meeting key ().

4. Analysis of SFrame

In Chapter 4, the group communication protocol SFrame and Key Management System MLS, which are in the process of standardization for video conferencing systems, are analyzed. Subsequently, the E2EE-related Zoom and SFrame protocols were investigated to compare and analyze the two systems. SFrame applies the E2EE mechanism to the WebRTC protocol, enabling real-time communication [

3].

The SFrame protocol employs double encryption to media, such as video or audio, ensuring secure transmission with E2EE. As a result, the SFU central server, which relays end-to-end media traffic, cannot access the plaintext message information but only the necessary metadata for communication routing. Moreover, SFrame encrypts the entire media frame during transmission rather than encrypting individual media packet separately. In other words, SFrame uses an initialization vector (

) and an authentication tag for each frame for encryption. This method has gained significant attention as it reduces communication overhead, which is a well-known challenge in E2EE [

3].

4.1. Structure of SFrame

The double encryption method applied by SFrame is as follows [

3]:

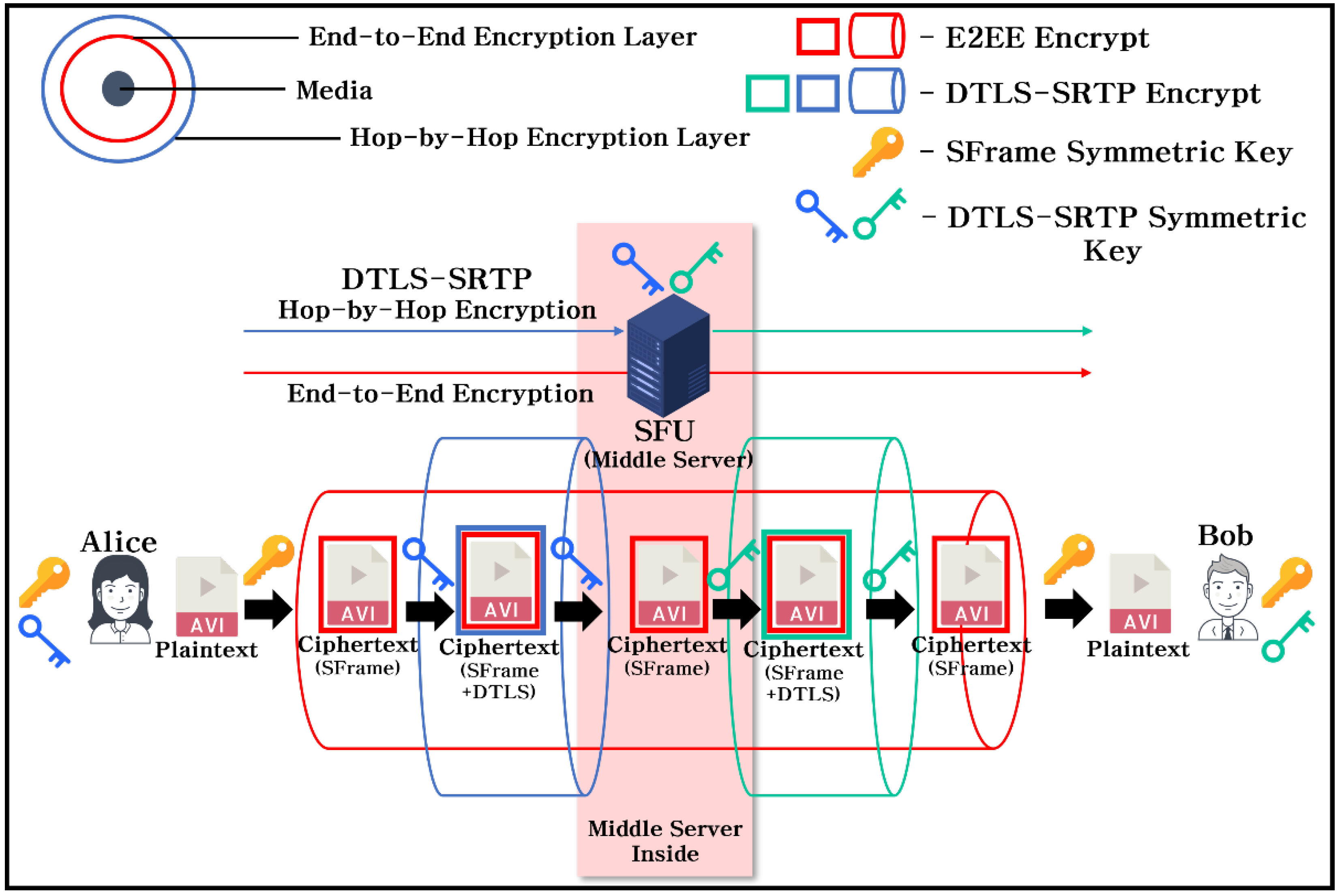

Figure 2. illustrates the process by which the communication parties, Alice and Bob, securely transmit media using the SFrame protocol with double encryption. First, the two entities share a group symmetric key schedule through a Key Management System with E2EE security in advance.

Alice retrieves the SFrame symmetric key from the pre shared key schedule and utilizes it to encrypt the media. Next, the encrypted media are packetized before being transmitted to the SFU. Alice encrypts the packetized media with the DTLS-SRTP symmetric key and transmits it to the SFU. The SFU decrypts the media packet using the pre-shared DTLS-SRTP symmetric key with Alice, and then re-encrypts the decrypted media with Bob’s DTLS-SRTP symmetric key before delivering it. Finally, Bob can decrypt the ciphertext sequentially with DTLS-SRTP key and SFrame symmetric key. Consequently, the plaintext of the media is not exposed to SFU. The SFU checks only the media metadata and routes the media packets received from Alice to Bob.

The symmetric key used for double encryption in the encryption/decryption process of the SFrame protocol is the same, and a Key Management System for the E2EE function is essential for symmetric key sharing. Theandinformation related to theare assigned to the entities of the group belonging to the Key Management System. Therefore, each entity obtains theinformation used for decryption by checking theof the transmitted media header. For SFrame encryption,is used as an input to the HKDF function to derive the SFrame symmetric key andvalue. Subsequently, ais generated by XORwith, and thevalue is used for encryption/decryption.

4.2. SFrame’s Key Management System

The SFrame protocol was proposed to separate the use of the key from the encryption algorithm. Using this design, any Key Management System with E2EE security can be applied to SFrame, for example, E2EE security protocols such as Signal Protocol, Olm Protocol, MLS, etc. Currently, the IETF draft document on SFrame recommends the use of MLS as the Key Management System [

3].

4.2.1. MLS Protocol

The MLS protocol is a Key Management System in the process of standardization by the IETF. MLS has been standardized since 2018, and recently, an RFC standard was proposed [

10].

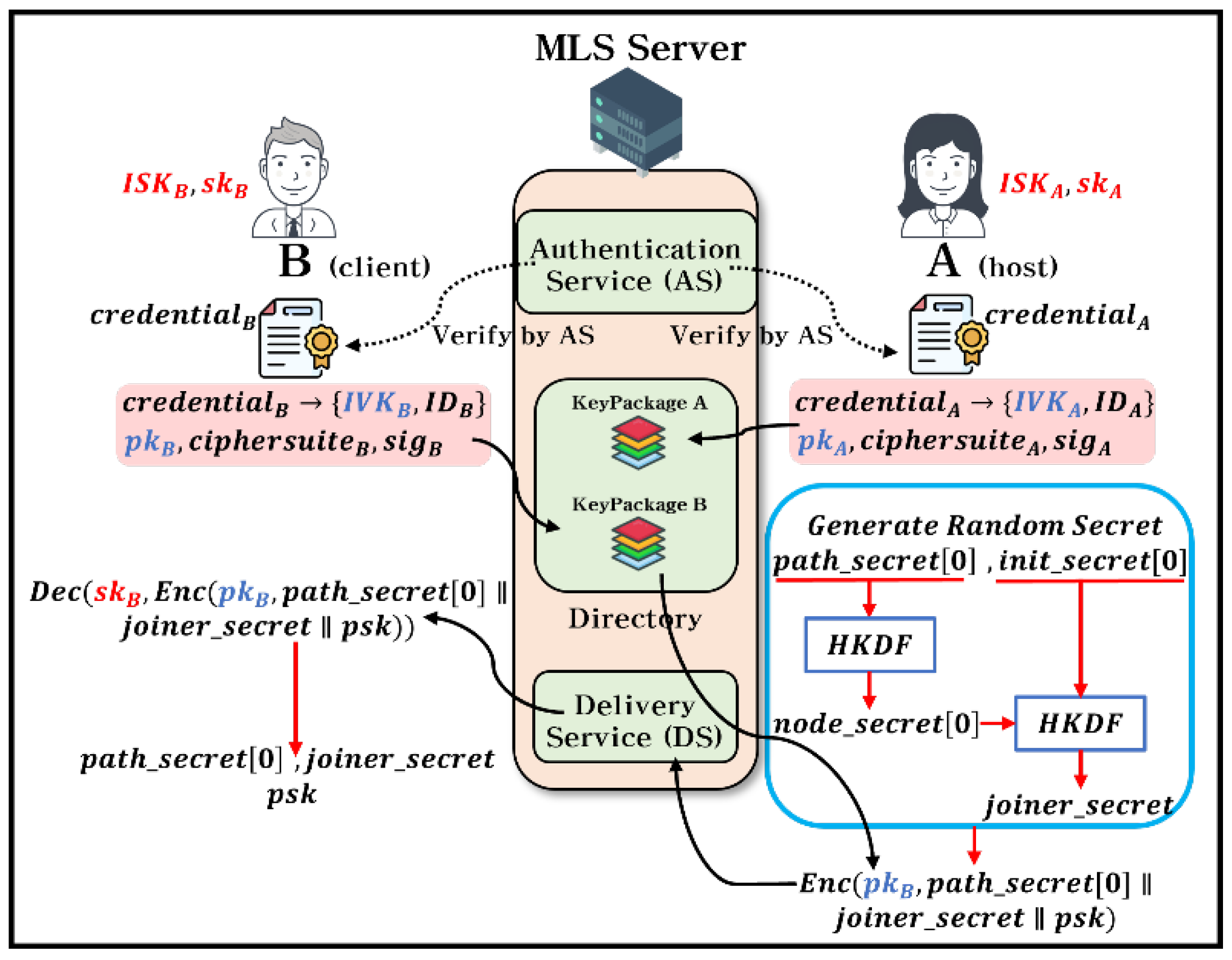

Figure 3. shows the initial group creation process for the MLS Key Management System. To describe this process, the Ratchet Tree, the key schedule of the MLS, and Secret Tree structures have to be explained; however, this paper describes the process of adding members without explaining the tree structure.

We describe progress of the

Figure 3. to Algorithm 2.:

Assume that a host creates a group, a client joins a group. They join the group presents their credentials for authentication and undergoes verification by the authentication service (AS) of the MLS server. The host and client upload a key package containing their ID, signature, and public key to the directory. (Algorithm 2., Line 2 - 4)

Next, the host generatesandby a cryptographically secure RNG, uses them as inputs to HKDF, and creates that necessary for make MLS key schedule. The host encrypts,, andwith the client’s public key () and transmits them. (Algorithm 2., Line 5 - 8)

The client decrypts the received ciphertext with own private key () to obtain thevalue. The client creates the same key schedule as the host, using the acquiredand. (Algorithm 2., Line 9 - 10)

|

Algorithm 2. E2EE Key Exchange Process of MLS Protocol. |

: host,: client,: public key,: secret key,: credential,

: verification key,: signing key,: identity,,: parameters to generate key schedule,: pre shared key

: Authentication Service |

| 1: procedure (MLS’s E2EE Key Exchange Process) |

| 2: For user , do ▷ |

| 3: ▷ |

| 4: DirectoryKeyPackage() ▷KeyPackage() |

| 5: For user do

|

| 6: Secure RNG

|

| 7: HKDF() |

| 8: DirectoryEnc(,) |

| 9: For user do

|

10: ,,

Dec(, Enc(,)) |

| 11: end procedure

|

4.3. Comparison between Zoom and SFrame

In this section, we compare the E2EE-related protocols of Zoom analyzed in

Section 3 and SFrame in

Section 4. The analysis of these two systems are presented in

Table 2.

To compare the E2EE-related protocols of the two systems, it was assumed that SFrame utilized the MLS protocol as its Key Management System. Conversely, SFrame is a video conferencing system in the standardization, it has the flexibility to support various ciphersuites. Zoom provides detailed information about ciphersuites in their whitepaper.

The Diffie-Hellman method, which is commonly used in the key agreement process of Zoom and SFrame, is a one-to-one method for both protocols. Zoom uses Curve25519 Diffie-Hellman to generate a symmetric key (

) for encryption/decryption and uses the Ed25519 EdDSA signature algorithm. In the case of SFrame, the elliptic curve method Diffie-Hellman KEM function of HPKE (RFC 9180) was used to share Ratchet Tree information among group members [

11]. The SFrame signature algorithm can be applied to both EdDSA and ECDSA.

Both systems encrypt and decrypt information regarding the shared key. Zoom exchanges the meeting key () by encrypting/decrypting with a symmetric key (), whereas SFrame shares,, andusing the asymmetric key encrypt/decrypt method.

As mentioned in

Section 2,

Table 1 lists the necessary features for E2EE security, such as authentication, confidentiality, and integrity. Both Zoom and SFrame fulfill all these features for E2EE security.

Finally, Zoom currently implements E2EE security up to Phase 2, and specification for a Phase 3 transparency tree is not implemented. In contrast, SFrame uses an asynchronous Ratchet Tree method, which enables users within a group to verify each other’s authentication in real-time. Therefore, SFrame can be considered to incorporate Phase 3, which corresponds to the structure of Zoom’s E2EE security plan.

5. Next-Generation Video Conferencing System

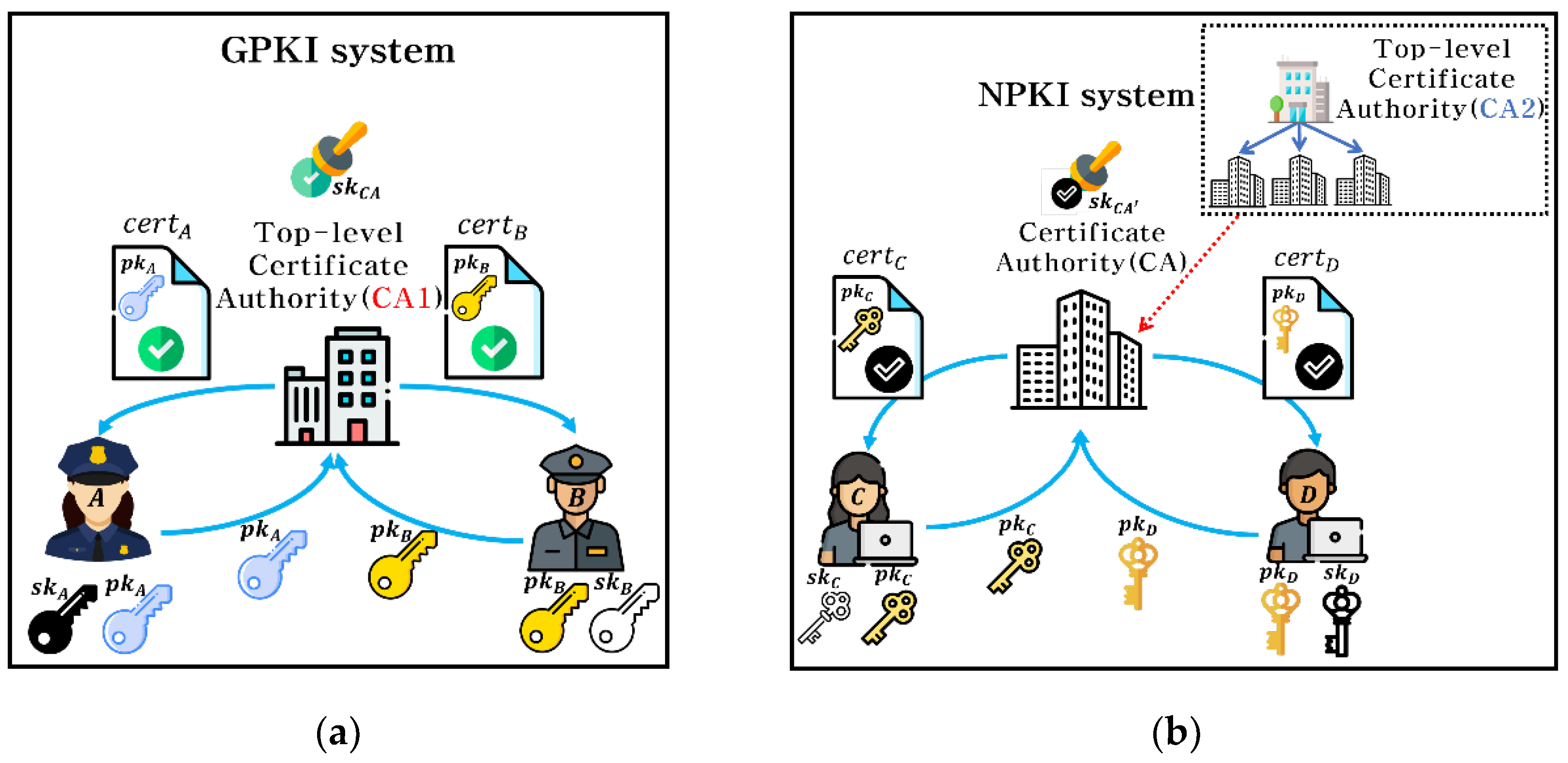

5.1. GPKI-based System

There are two issues with the operation method of public key cryptography: no user authentication and expiration date for the public key. In order to use a public key passed on to someone else, it is required to have a trusted institution who can manage the list of public keys. The GPKI is an example of such an infrastructure that provides the necessary mechanisms for managing and distributing public keys securely. The GPKI, also known as an administrative electronic signature, utilizes GPKI certificates issued by certification authorities. These certificates serve as electronic information that verifies and provides evidence of the authenticity of signatures. Electronic information is issued to administrative, auxiliary, and assistant agencies, public infrastructure, banks, or users [

12].

Figure 4. depicts GPKI-based and National Public Key Infrastructure (NPKI)-based certification scheme. First, the GPKI system use a Top-level certification authority (CA1) to manage a list of public keys for public service worker (

A,

B). The CA1 issues a certificate (

certI)) containing a signature for the public key (

) that signs with its private key (

). Second, NPKI system use another Top-level certification authority (CA2) that managing multiple CA. These multiple CA maintain public keys for civilian (

C,

D). Also, these CA issue a certificate (

) for civilian. These two systems mutually recognize authentication systems each other and collaborate to manage a certificate trust list. As CA1, CA2, and CA are a trusted authority, users can trust the public key contained in the certificate issued by a trusted authority.

5.2. End-to-End PQC encryption protocol applicable to GPKI-based video conferencing systems

GPKI-based video conferencing systems employ user authentication mechanisms that differ from those used in the private sector. Unlike Zoom’s login and signature method and authentication through SFrame’s credentials, GPKI-based video conferencing systems require a login with a certificate issued by a government agency. Consequently, if all meeting participants are affiliated with a government agency and possess GPKI-based certificates, there are no obstacles to their participation. Meanwhile, ordinary people who participate in meetings do not have GPKI certificates; therefore, another authentication method is required. Access through a provided link or a one-time password authentication method may be a possible method for authenticating the private sector.

We propose the application of PQC KEM to the user key exchange process of the E2EE protocol in a GPKI-based video conferencing system. Previously, in Zoom’s E2EE security Phase 1, Client Key Management and meeting data could be encrypted or decrypted if a 32-bytewas shared securely. In the proposed next-generation video conferencing system, the session key () shared through KEM plays the same role as the 32-bytein Zoom.

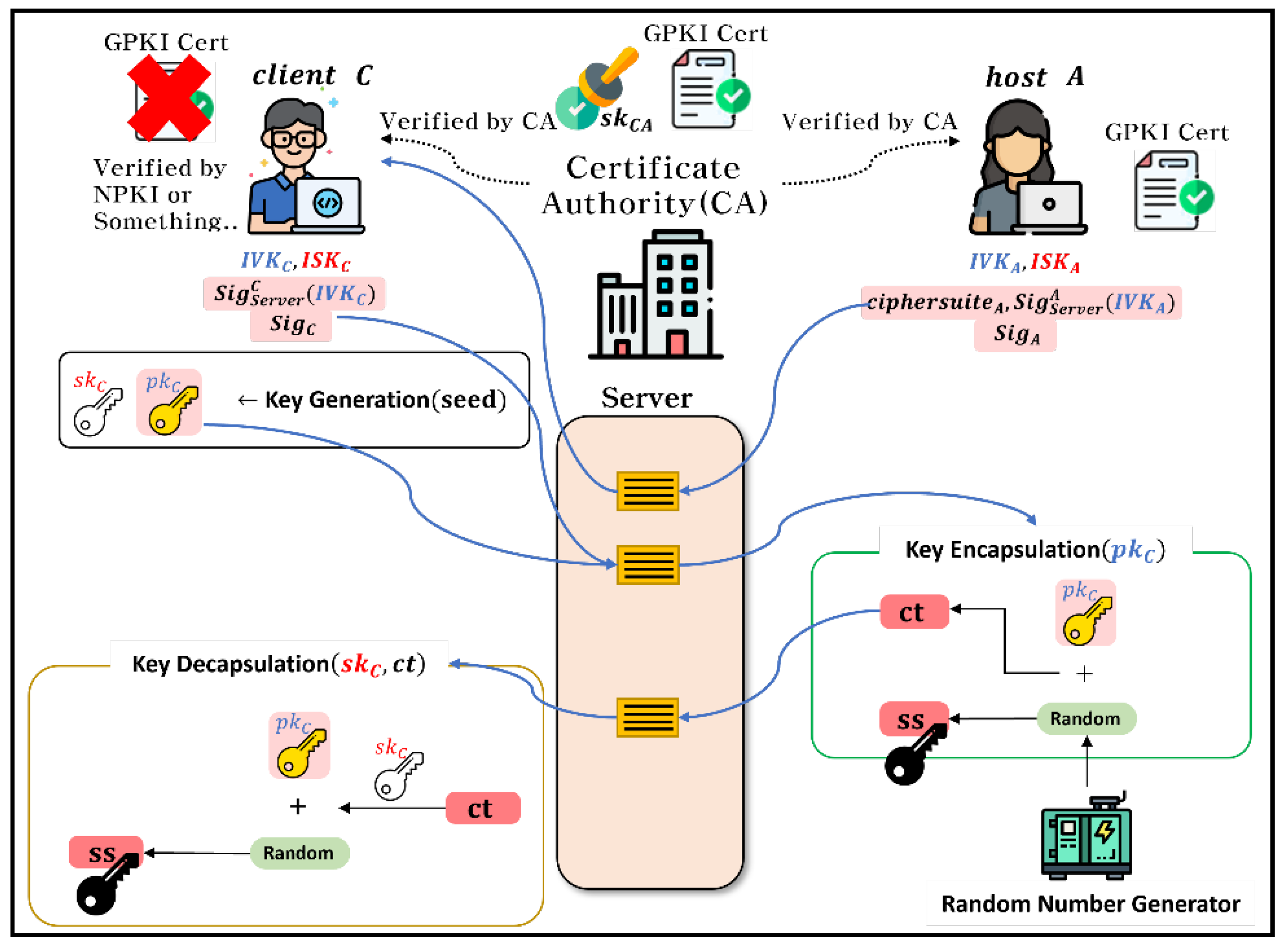

Figure 5. is the application of the PQC KEM to the GPKI-based video conferencing system. We describe progress of the

Figure 5. to Algorithm 3.:

First, it is assumed that both the host (

A), who owns the GPKI, and the general client (

C) are normally authenticated. The host uploads ciphersuite (

), server’s signature for verification key (

), and own signature (

). Subsequently, the client generates a public key (

) and a private key (

) using the host’s ciphersuite. The client then uploads its public key (

), server’s signature for the verification key (

), and own signature (

). Next, the host creates a session key (

) using a random source extracted from a cryptographically secure RNG. The host encrypts the session key (

) with the client’s public key (

), and uploads it. The client decrypts the ciphertext with the secret key (

) to obtain the session key (

). Finally, the host and client can securely encrypt/decrypt with session key (

) and share conference data.

|

Algorithm 3. E2EE Key Exchange Process with KEM applied to Next-generation Video Conferencing System. |

|

: host,: client,: public key,: secret key,: verification key,: signing key,: signature of the server for verification key,: signature for public key,: random source,: shared session key,: ciphertext |

| 1: procedure (Next-generation video conferencing system’s E2EE Key Exchange Process) |

| 2: For user , do ▷ |

| 3: |

| 4: For user do

|

| 5: Server{,,} |

| 6: For user do

|

| 7: (,)KeyGen

|

| 8: Server{,,} |

| 9: For user do

|

| 10: Secure RNG

|

| 11: Server(,) |

| 12: For user do

|

| 13: (,) |

| 14: end procedure

|

The next-generation video conferencing system depicted in

Figure 5., which utilized the PQC KEM, addresses the integrity requirement by leveraging authentication and signing provided by the GPKI. Moreover, this system satisfies the confidentiality requirements through public key encryption. Hence, the PQC encryption protocol employed in the GPKI-based video conferencing system fulfills the E2EE security features outlined in

Table 1.

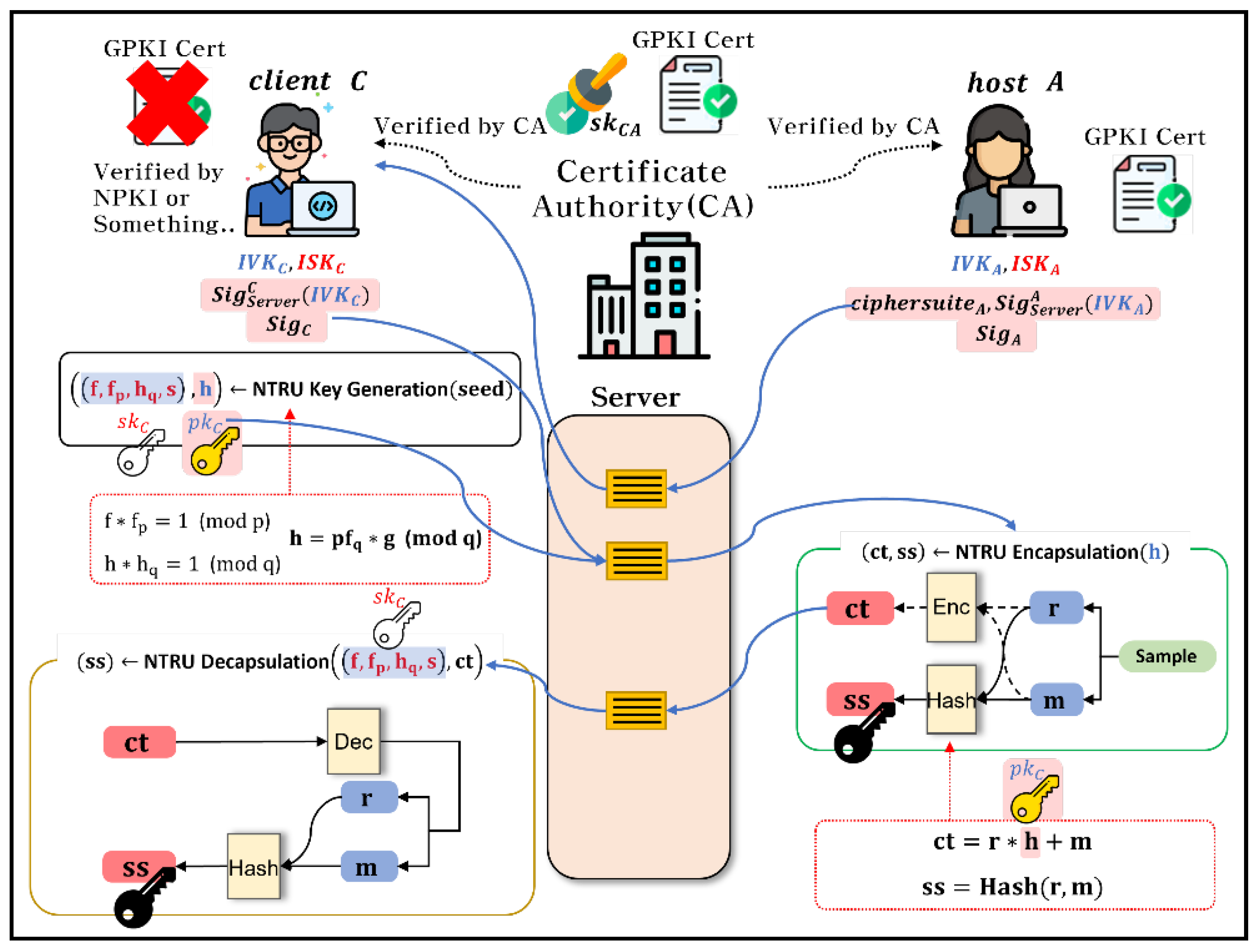

Figure 6. illustrates an example of applying NTRU KEM, one of the 3rd round candidates for the NIST PQC standardization contest, into a GPKI-based video conferencing system. When using a ciphersuite of NTRU KEM with a security level 1, such as ‘ntruhps2048509’, the size of the shared session key (

ss) is 32-byte, which is the same size of the

in Zoom [

13].

First, the host (A) uploads the server’s signature for the verification key and ciphersuite. The client (C) generates a private key (,,,) and a public key () using the NTRU algorithm, and uploads the public key () and signature. Second, the host extracts a random value (,) using a cryptographically secure RNG, and encrypts it with public key (). During this procedure, the host creates a 32-byte session key () with a random value (,). Third, the client decrypts the ciphertext with his own private key (,,,), and gets (,). Finally, it generates a 32-byte session key () with (,) in the same way as the host. Consequently, the host and client both have the 32-byte shared symmetric session key () without exposing the key to the central server.

The NTRU KEM was used as the PQC scheme in

Figure 6., but other PQC schemes could also be applied to the proposed PQC encryption protocol. As a possible option, since CRYSTALS-KYBER has been selected as the PQC KEM standard after the 3rd round of NIST PQC standardization competition [

14], applying this KEM to the proposed GPKI-based video conferencing system’s E2EE PQC protocol could contribute to improve the security of the next-generation video conferencing system.

6. Conclusions

We examine and compare two representative video conferencing systems, Zoom and SFrame, focusing on their E2EE capabilities. Both systems were found to meet the necessary features of E2EE; however, there was a difference between Zoom, which uses a symmetric key method, and SFrame, which uses an asymmetric key method for encrypting and decrypting shared keys.

To improve the security of E2EE protocols in GPKI-based video conferencing systems that are not in the private sector, we propose the application of PQC KEM during the key exchange process. This mechanism satisfies integrity through signing with GPKI-based authentication and confidentiality through encryption, resulting in E2EE security. Moreover, we expect this mechanism to securely share session keys even in the face of the escalating threat posed by quantum computers. Therefore, the security of video conferencing systems can be improved.

The proposed PQC protocol for E2EE in a GPKI-based video conferencing system appears to serve as valuable reference material for enhancing the On-Nara video conferencing system based on the Korea GPKI. However, as there is currently no established Korean standard for PQC, the application of a specific PQC KEM algorithm may necessitate future modifications for its usage in video conferencing systems. Therefore, the application of a specific PQC algorithm to the proposed protocol is left for future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P. and Y.Y.; Methodology, Y.P.; Validation, Y.Y., J.K., H.Y., J.R. and Y.C.; Formal analysis, Y.P. and Y.Y.; Investigation, Y.P., H.Y., J.R. and Y.C.; Resources, Y.P. and Y.Y.; Data curation, Y.P. and Y.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.P.; Writing—Review & Editing, Y.P. and Y.Y.; Visualization, H.Y., J.R. and Y.C.; Supervision, Y.Y. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No.2021-0-00046, Development of next-generation cryptosystem to improve security and usability of the national information system).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Menezes, A.; Stebila, D. End-to-End security: When do we have it?. IEEE Security & Privacy. 2021, 19, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Blum, J.; Booth, S.; Chen, B.; Gal, O.; Krohn, M.; Len, J.; Lyons, K.; Marcedone, A.; Maxim, M.; Mou, M.E.; et al. E2E Encryption for Zoom meetings v3.2. 2021. Available online: https://css.csail.mit.edu/6.858/2023/readings/zoom_e2e_v3_2.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Omara, E.; Uberti, J.; Murillo, S.G.; Barnes, R.; Fablet, Y. Secure Frame (SFrame): draft-ietf-sframe-enc-00. 2022. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-sframe-enc/00/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Isobe, T.; Ito, R.; Minematsu, K. Security Analysis of SFrame. ESORICS 2021, Darmstadt, Germany, 4–8 October 2021; pp. 127–146.

- Knodel, M.; Celi, S.; Baker, F.; Kolkman, O.; Grover, G. Definition of End-to-end Encryption: draft-knodel-e2ee-definition-07. 2022. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-knodel-e2ee-definition/07/ (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Cisco Webex Meetings Security White Paper. 2022. Available online: https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/collateral/conferencing/webex-meeting-center/white-paper-c11-737588.html (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Securing Webex Meetings with Zero Trust Security. 2021. Available online: https://community.cisco.com/kxiwq67737/attachments/kxiwq67737/webex-announcements/355/1/Zero%20Trust%20Security%20for%20Webex%20Meetings%20-%20Walk%20Through%20Wednesday.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Barnes, R.; Andrews, J.H.; McCarney, D.; Kasten, J. Automatic Certificate Management Environment (ACME): RFC 8555. 2020. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc8555/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Kim, K.; Choi, Y. Comparing Zoom’s security analysis and security update results. Journal of Korea Society of Digital Industry and Information Management. 2020, 16, 55–65.

- Barnes, R.; Beurdouche, B.; Robert, R.; Millican, J.; Omara, E.; Cohn-Gordon, K. The messaging layer security (MLS) protocol: draft-ietf-mls-protocol-16. 2022. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-mls-protocol/16/ (accessed on 08 December 2022).

- Barnes, R.; Bhargavan, K.; Lipp, B.; Wood, C. Hybrid public key encryption: RFC 9180. 2022. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9180/ (accessed on 04 December 2022).

- Introduction of administrative electronic signature certificate. Available online: https://www.gpki.go.kr/jsp/certInfo/certIntro/eSignature/searchEsignature.jsp (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Chen, C.; Danba, O.; Hoffstein, J.; Hulsing, A.; Rijneveld, J.; Schanck, J.M.; Schwabe, P.; Whyte, W.; Zhang, Z. NTRU: Algorithm specifications and supporting documentation. 2019. Available online: https://ntru.org/f/ntru-20190330.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Alagic, G.; Apon, D.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Liu Y.K.; Miller, C.; Moody, D.; et al. Status report on the third round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography standardization process. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2022/NIST.IR.8413-upd1.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).