1. Introduction

Sugars are a vital source of energy and essential nutrients for living organisms. However, modifications to the lysine and arginine residues of proteins

in vivo, which result in the formation of crosslinks, may significantly change the steric structures of proteins, thereby affecting their activities and physical properties. This process is known as glycation or the Maillard reaction and is divided into two stages: an early-stage reaction that produces Amadori transfer products and a late-stage reaction that results in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) through oxidation, dehydration, and condensation [

1]. AGEs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as diabetes [

2], liver disease [

3,

4], atherosclerosis [

5], Alzheimer’s disease [

6], and aging [

7].

AGEs are generated

in vivo not only from glucose, but also from, for example, metabolic intermediates of glucose, degradation products, and Maillard reaction intermediates [

8,

9,

10]. Among AGEs, those derived from glyceraldehyde (GA), a trisaccharide intermediate in fructose and glucose metabolism (toxic AGEs: TAGE), are highly cytotoxic [

11] and have been associated with diabetic complications [

12], insulin resistance [

13], heart disease [

14], Alzheimer’s disease [

6], hypertension [

15], nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [

3,

16], and cancer [

17,

18]. The late-stage Maillard reaction is irreversible and once TAGE are formed, there are no known enzymes that specifically remove the sites modified by glycation. The mechanisms by which intracellularly formed TAGE impair cells have not yet been elucidated in detail. Glycation modifications have been suggested to compromise cellular homeostasis by inducing the loss of function of various biomolecules or by forming toxic aggregates, which inactivate other normal essential proteins [

19,

20,

21,

22].

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and autophagy pathway are intracellular systems that remove defective proteins and aggregates. These two pathways are not independent of each other, they function cooperatively [

3,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Recent studies suggested that AGEs are closely associated with autophagy [

27]. Their effects on autophagy are complex, with some studies indicating that they inhibit autophagy [

28,

29] and others suggesting that they induce autophagy [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, the coordinated role of the two intracellular degradation mechanisms in the AGE clearance process remains unclear. Although AGEs are formed and accumulate in proteins with a long turnover due to a decrease in the activities of intracellular protein quality control mechanisms with aging, the mechanisms underlying intracellular TAGE degradation and removal have yet to be clarified. A more detailed understanding of these mechanisms is critical for the development of effective therapeutic strategies that mitigate the detrimental effects of TAGE accumulation.

In the present study, we identified d270KD, a mutant lacking the regulatory region of constitutively inactive checkpoint kinase-1 (CHK1), which is rapidly degraded upon a GA stimulation with the formation of high-molecular-weight complexes (typical features indicative of TAGE conversion). d270KD, which is rapidly degraded with TAGE formation, may serve as a useful model of TAGE formation in future research on the molecular mechanisms that act on the clearance of TAGE formed in cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies

The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-mouse IgG2a-magnetic beads (M076-11), anti-DYKDDDDK (Flag)-tag-magnetic beads (M185-11), anti-V5-tag-magnetic beads (M16711), anti-normal rabbit IgG (PM035) for immunoprecipitation, and anti-HA-tag (M132-3) and anti-α-tubulin-HRP for Western blotting from Medical & Biological Laboratories. (MBL, Nagoya, Japan); anti-phospho-SQSTM1/p62 (Ser403) (#39786), anti-SQSTM1/p62 (#5114), and anti-Huwe1 (#5695) from Cell Signaling Technologies (CST, Beverley, MA); anti-V5-HRP (R961-25) from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA); anti-Flag-HRP (015-22391) from Wako Pure Chemicals, (Osaka, Japan); anti-ubiquitin (#AUB01) from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO). An anti-TAGE antibody was prepared as previously reported [

34].

2.2. Cell culture

COS-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM+GlutaMax medium; Gibco BRL, Gland Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (both from Gibco BRL) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. HeLa cells (a gift from Dr. Sumiyo Akazawa, Kanazawa Medical University, Japan) were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM alpha+GlutaMax medium; Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured when they reached 70–80% confluence. In experiments where GA (Nacalai Tesque, Tokyo, Japan) was applied to cells, GA or phosphate buffer was added at the concentrations indicated. In the aminoguanidine (AG)-induced suppression experiment, AG at the indicated concentrations was added to cells 2 h prior to the treatment with GA. Regarding the proteasome inhibitor treatment, cells were treated with 10 µM MG-132 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) or DMSO (Nacalai Tesque) for 6 h.

2.3. Generation of expression plasmid constructs

Flag-tagged CHK1 expression constructs, including the wild-type (WT) form and its kinase-dead mutant form (KDmut), were previously described [

35]. Briefly, cDNA encoding full-length rat Chk1 was amplified from rat cardiac myocyte cDNA using a forward primer containing the Flag-tag sequence at the 5' end and then subcloned into the pcDNA4/HisMax vector. Xpress- and 6×His tag sequences at the N terminus were removed from the vector by PCR using the KOD-plus-mutagenesis kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Deletion at the C terminus and point mutations in Flag-Chk1 expression vectors were created by PCR using the KOD-plus-mutagenesis kit. To generate the d270KD-EGFP-V5 expression construct, full-length EGFP cDNA was amplified by PCR using the pEGFP-C1 vector (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The open-reading frame of EGFP with the V5-tag and 6×His-tag sequences at the C terminus was then amplified using the vector as a template by PCR using PrimeSTAR Max DNA polymerase, subcloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the TOPO

® cloning procedure, and then transformed into the mammalian expression vector pDEST30 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by LR clonase II enzyme. Fragments containing the N-terminal region of Chk1 (amino acids 1-270) in pFlag-Chk1Wt and its KDmut vectors were cloned in the vector in-frame with the gene that encodes the EGFP-V5/6×His-tag at the 3' end using the In-Fusion

® HD PCR cloning kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). HA-Ubiquitin was a gift from Edward Yeh (Addgene plasmid #18712). All constructs were sequenced to ensure proper ligation in the frame and Taq polymerase fidelity using the ABI PRISM TM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, USA).

2.4. Transfection

Regarding transient plasmid DNA transfection, cells were seeded on 35-, 60-, 100-mm, or 6-well tissue culture plates, cultured in complete growth medium, and then transfected using FuGENE® 4K (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The transfection of siRNA was performed using RNAiMax Transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The final siRNA concentration was 5 nM. Silencer Select siRNA (Ambion, Valencia, California) targeting Huwe1 (siRNA ID: s19596 and s19597), SQSTM1 (siRNA ID: s16962), or scrambled siRNA (Silencer Select Negative Control #1, catalogue #4390843) was used.

2.5. Western blot

Transfected COS-7 and HeLa cells were lysed in lysis buffer (CelLytic™M cell lysis reagent; Sigma-Aldrich) containing proteinase inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (both from Nacalai Tesque). After cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, protein concentrations in the supernatants were measured using the Qubit protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To detect TAGE or high-molecular-weight complexes, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS), centrifuged, and separated into their supernatant (soluble fraction) and pellet (insoluble fraction). After the addition of SDS sample buffer to each fraction, the RIPA-insoluble fraction was sonicated. All samples were boiled at 95 °C for 5 min, separated on 5-12 or 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels, and analyzed by Western blotting. Target proteins were visualized by Chemi-Lumi One L, Super (Nacalai Tesque) or Immobilon Forte Western HRP Substrate (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

2.6. In vitro TAGE modification assay

The in vitro TAGE modification of the d270KD protein was performed with some modifications to previous methods. Briefly, HeLa cells transfected with Flag-tag fused d270KD (Flag-d270KD) were lysed in CelLytic™M cell lysis reagent containing proteinase inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors. After cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, total cellular proteins were incubated with anti-Flag antibody-immobilized magnetic beads at 4 °C overnight, and the resulting immunoprecipitates were washed three times with lysis reagent. After the elution of Flag-d270KD with 40 µl of Flag peptide (2 mg/ml), 200 µl of PBS was added. Eluted samples, including Flag-d270KD were then ultrafiltrated and concentrated with Amicon Ultra 0.5 (10K) (Millipore) to remove the FLAG peptide. This purified Flag-d270KD recombinant protein (2.5 µg) was incubated in 50 µl of PBS for 20 h with or without the addition of 4 mM GA. After the addition of SDS sample buffer to these reaction mixtures, they were boiled at 95 °C for 5 minutes.

2.7. In vivo ubiquitination assay

In in vivo ubiquitylation assays, the d270KD-EGFP expression vector d270KD-EGFP was transfected with COS-7 cells (100-mm plates) for 48 h. Cells were treated with 10 µM MG132 and then harvested after 8 h. Cell pellets were resuspended in denaturing buffer (1.5% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, and 5 mM DTT) followed by boiling at 10 min, and were then diluted 10-fold with CelLytic™M cell lysis reagent containing proteinase inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors. After cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, extracted proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody-immobilized magnetic beads and subjected to the assay described above. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies or anti-V5 antibodies.

2.8. Luciferase assay

The gene encoding luciferase was amplified by PCR using the pGL4.54 vector (Promega) as a template with the forward primer (5'-ACAAACACACTTAACATGGAAGATGCCAAAAAC-3') and reverse primer (5'-GTAACAGGCCTTCTACACGGGCGATCTTGCCGCCC-3'). The pFlag-d270KD plasmid vector was amplified by PCR using the forward primer (5'-TA GAAGGGCCTGTACCTAGGATCCAGT-3') and reverse primer (5'-GTTAAGTGGTTTGTTATACCATCTA-3') for amplification by PCR to form a linear strand. The luciferase gene was then inserted downstream of the d270KD gene using the InFusion HD cloning kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The accuracy of the gene insertion site was confirmed by a sequence analysis. Twenty-four hours after the transfection of the d270KD fusion luciferase expression vector (d270KD-Luc) into cells cultured in 6-well plates, the Firefly luciferase reporter assay was performed using the Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Three independent assays were performed under each condition.

2.9. Fluorescence imaging analysis

COS-7 cells were grown in six-well plates containing collagen-coated glass coverslips (diameter of 12 mm, Iwaki) and transfected with the d270KD-EGFP expression vector at 60% confluence using FuGENE® 4K as described above. After an incubation for 24 h in complete medium, cells were treated with or without GA (2 mM) for the indicated time and fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. Fixed cells were washed three times for 5 min each with PBS and then mounted with Prolong gold antifade reagent/DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All fluorescence images were obtained using a digital high-definition microscope system (BZ-9000, Keyence, Osaka, Japan) with the following filter sets: OP-66834, Ex360/40 Em460/50; OP-66836, Ex470/40 Em535/50; OP-66838, Ex560/40 Em630/60.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All numerical results are reported as the mean ± SEM of at least three measurements. Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test with GraphPad Prism software (Version 5.0, GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered to be significant at p <0.01 and were denoted by an asterisk in the graphs.

4. Discussion

Under hyperglycemic conditions, glucose, fructose, and its metabolic intermediates bind non-enzymatically to intracellular proteins to produce AGEs. Among these AGEs, GA-derived AGEs, known as TAGE, are highly cytotoxic and have been implicated in various pathological conditions, such as diabetic complications, insulin resistance, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, hypertension, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, obesity, and cancer [

7,

41,

42,

43]. TAGE predominantly form intracellularly as a result of glycation reactions between GA and intracellular proteins, resulting in a wide range of TAGE molecules with different sizes and properties. The mechanisms by which TAGE exert their cytotoxic effects have not yet been elucidated in detail; however, previous studies suggested that TAGE toxicity was attributed to oxidative stress damage [

36], the loss of protein functions due to glycation modifications [

44], and the aggregation and accumulation of TAGE [

20].

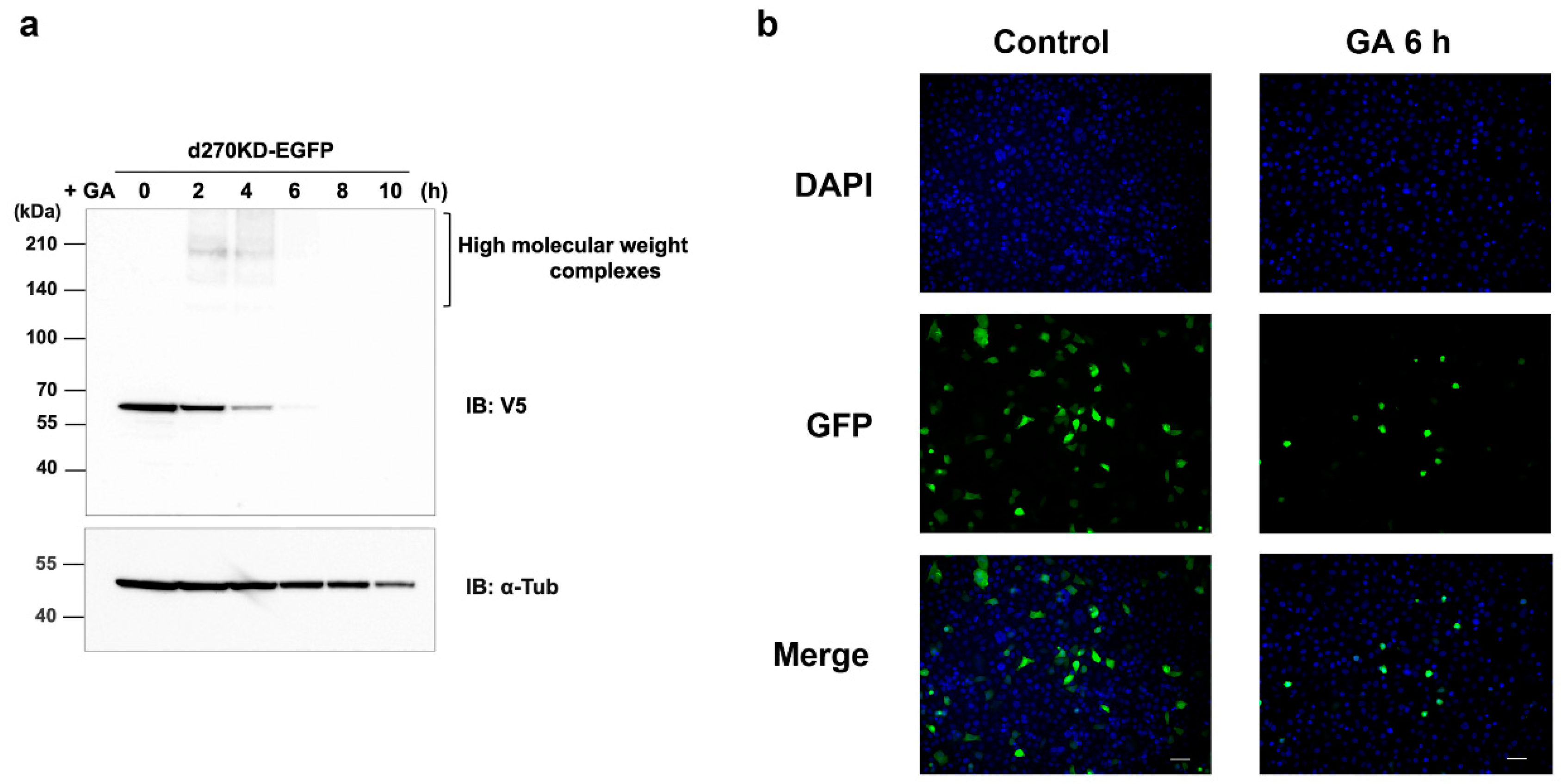

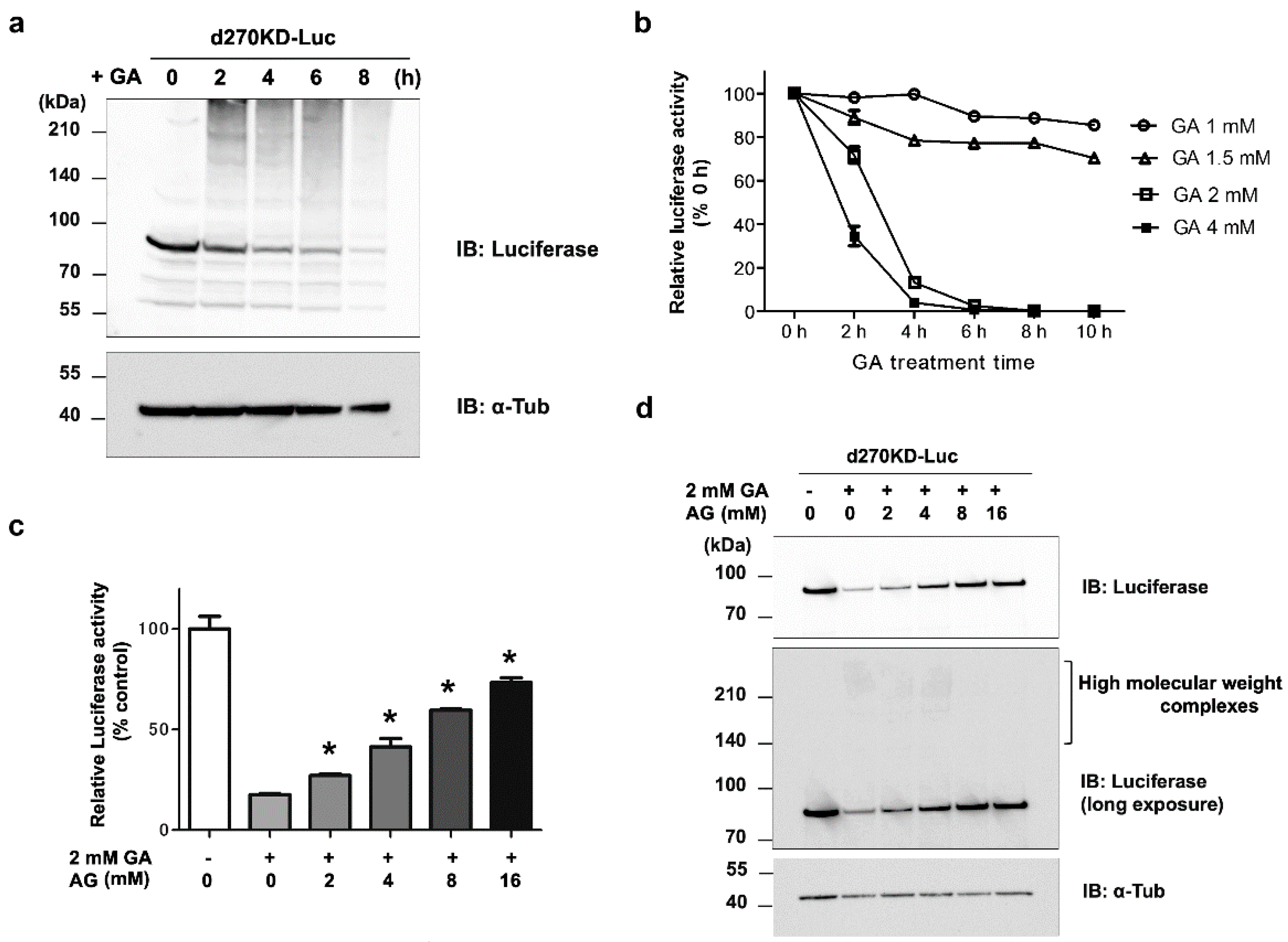

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show the rapid degradation (less than 2 h) of a protein in an experimental model in which intracellular AGEs were formed by the administration of glycating agents, such as GA and methylglyoxal (MGO) to cells. Even when d270KD was fused with relatively stable proteins, such as EGFP or luciferase, the GA-responsive rapid degradation property was retained (

Figure 3 and

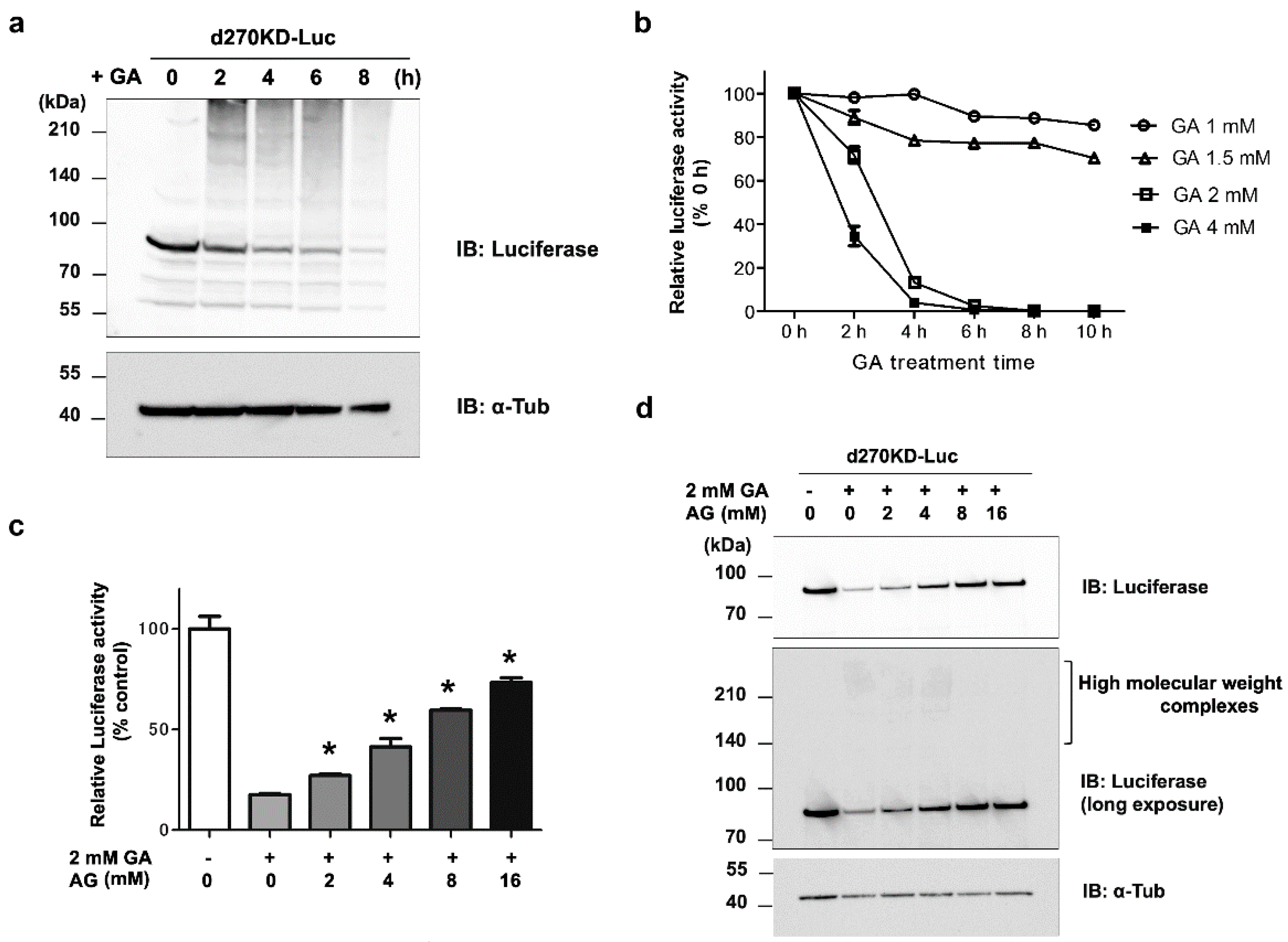

Figure 4), indicating that d270KD functions as a degradation element induced by glycated substances. Furthermore, a reporter assay using luciferase activity in d270KD-Luc-transfected cells allowed the degradation process to be monitored without a Western blot analysis, and GA-induced reductions in luciferase activity were attenuated by inhibitors of AGE formation in a concentration-dependent manner (

Figure 4c). Therefore, this reporter assay using d270KD-Luc-transfected cells may be a useful tool for the rapid screening of natural compounds that inhibit the formation of AGE.

The etiology of TAGE toxicity is attributed to the functional impairment of the proteins themselves as a result of TAGE modifications. Previous studies demonstrated that chaperone molecules, such as Hsc70 [

22], and a mediator of apoptosis, caspase-3 formed high-molecular-weight complexes that led to a loss of activity due to TAGE modifications [

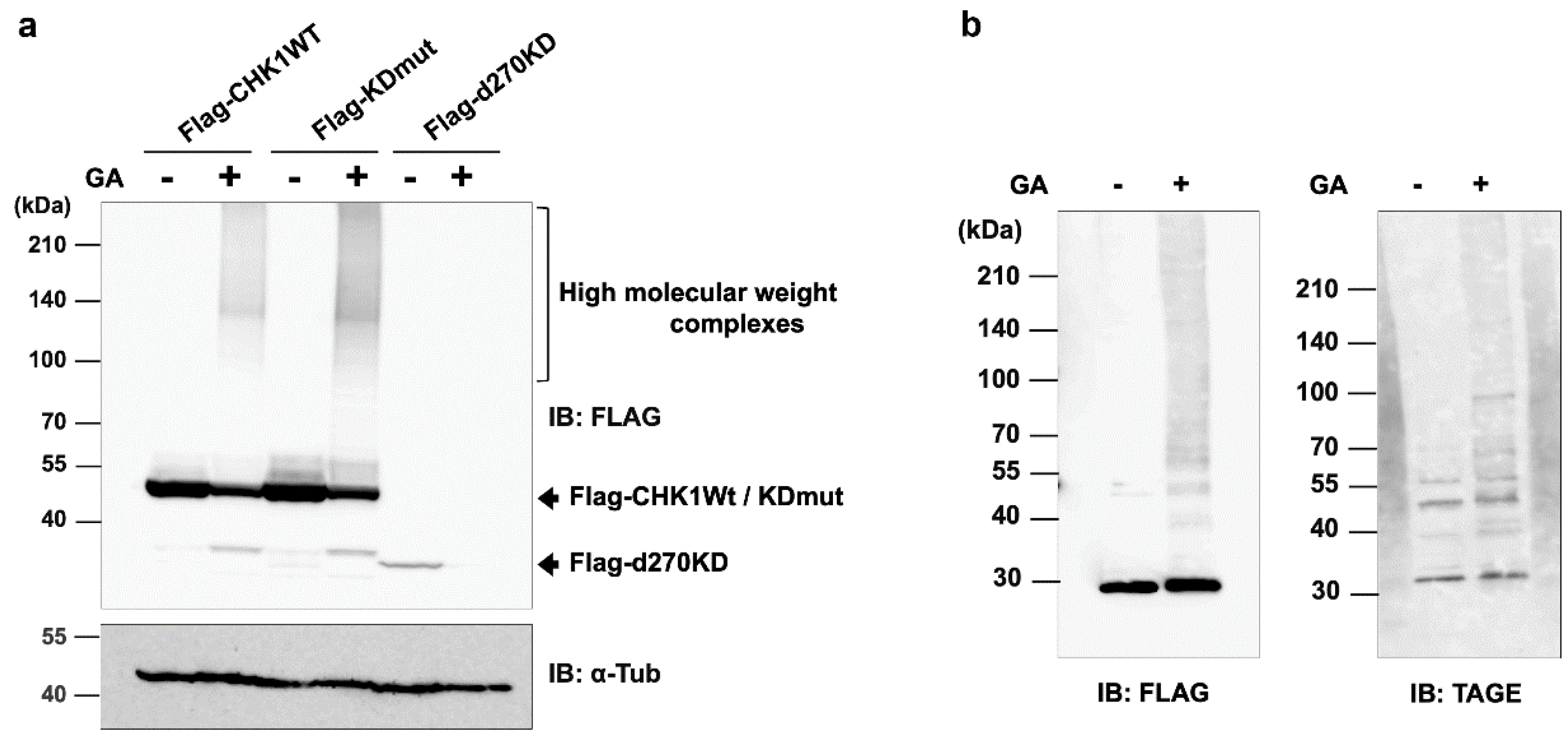

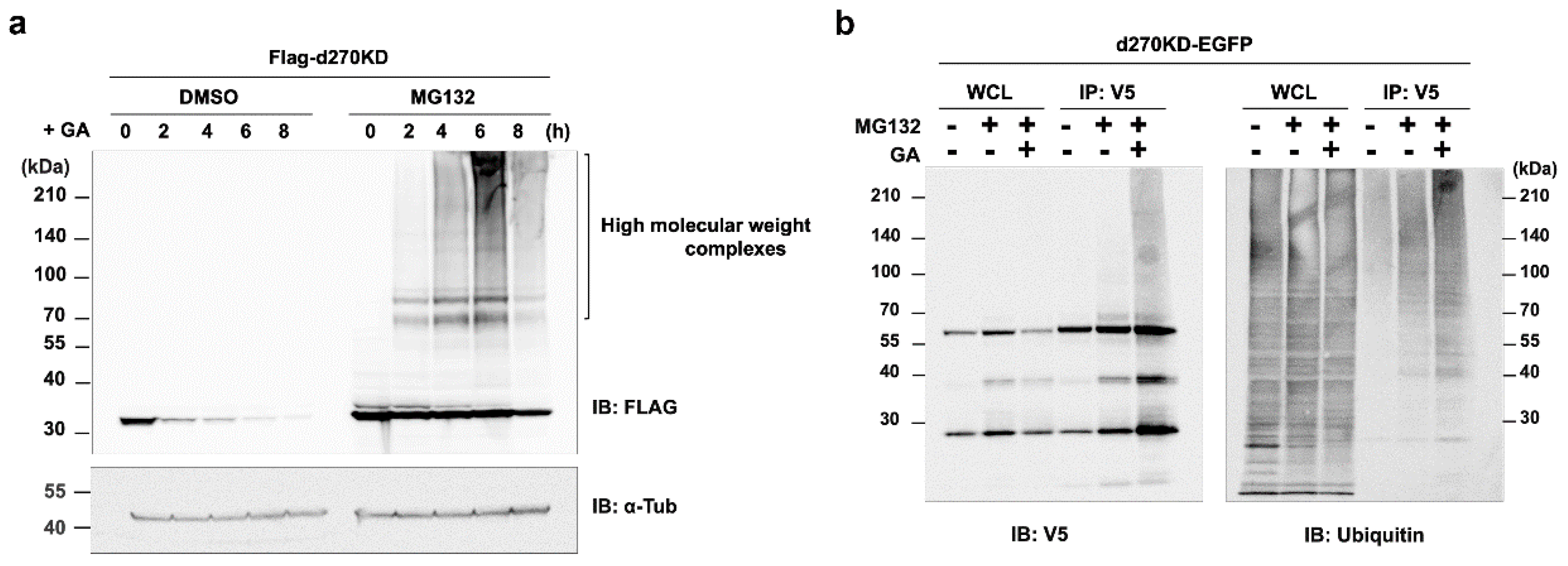

16]. In the present study, we observed the similar formation and accumulation of high-molecular-weight complexes in CHK1 after the GA stimulation, as shown in

Figure 1. CHK1 is a well-known key player in the cellular stress response to DNA damage and the normal progression of the cell cycle under non-stress conditions [

37]. Therefore, CHK1 may be a target of TAGE modifications, and its functional impairment may be responsible for the induction of TAGE-mediated cell death. A previous study reported that Mule/HUWE1, a HECT-type ubiquitin E3 ligase, ubiquitinated CHK1 and played a critical role in regulating the basal level of CHK1 [

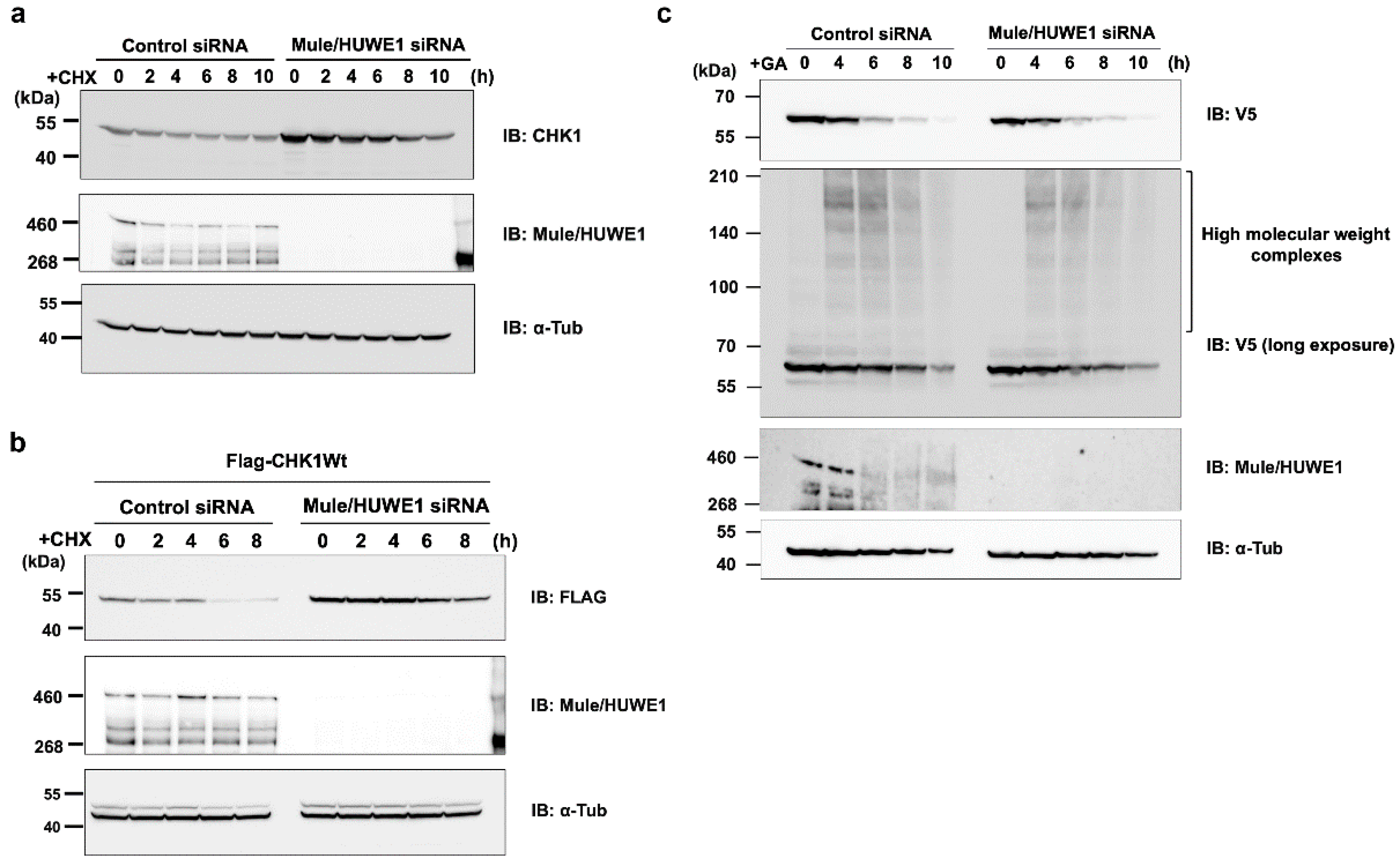

38]. In our HeLa cell model, we noted a decrease in endogenously and transiently expressed CHK1 turnover after the elimination of Mule, as shown in

Figure 6a and 6b. However, the knockdown of Mule did not affect the degradation of d270KD in response to the GA stimulation or suppress the formation of high-molecular-weight complexes, as shown in

Figure 6c. These results suggest that the degradation mechanism of d270KD, which is dependent on glycation modifications, involves a distinct pathway from the steady-state degradation mechanism of CHK1.

An important result from our Western blot analysis is that Mule was also affected by GA-induced glycation, as shown in

Figure 6c (Control siRNA). Specifically, the GA stimulation for 6 h resulted in a conspicuous smear of the putative monomer form of Mule. However, it remains unclear whether the decrease in single bands was a consequence of TAGE-modified Mule degradation induced by the GA stimulation or the formation of high-molecular-weight complexes. This uncertainty is attributed to the technical challenges associated with analyzing the behavior of TAGE-modified Mule over time because the transfer efficiency of high-molecular-weight proteins to a PVDF membrane is very low in a conventional Western blot analysis. The loss of function of ubiquitin ligases due to TAGE modifications may lead to the accumulation of proteins that need to be degraded, further exacerbating non-enzymatic glycation reactions and disrupting protein homeostasis. Therefore, a more comprehensive and detailed analysis of the effects of GA-induced glycation on ubiquitin ligases is warranted in the future.

Another possible cause of cellular damage due to TAGE is proteopathy, a broad term that refers to the crosslinking of glycated proteins between molecules over time, resulting in the formation of larger high-molecular-weight complexes that gradually aggregate and accumulate, disrupting normal protein function [

19]. The proper folding of intracellular proteins is crucial for their biological functions, while aberrantly folded proteins may accumulate and aggregate in cells, leading to cellular stress. In response to this stress, cells activate mechanisms to monitor protein folding, such as the unfolded protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum [

45], which induces autophagy, an intracellular degradation mechanism that recycles damaged proteins and protects cells. Non-enzymatic glycation modifications to intracellular proteins may lead to structural mutations and the formation of abnormal proteins, which may be recognized as aberrant by intracellular protein quality control mechanisms.

Extracellular AGEs have also been shown to activate intracellular autophagy pathways, which often have a cytoprotective role [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Intracellularly formed AGEs were previously found to induce autophagy [

27]. For example, in a model in which cells were treated with MGO, a glycating substance, to accumulate intracellular AGEs (MG-H1), autophagy was induced through a pathway that involved p62. Importantly, while the loss of p62 promotes the accumulation of AGEs, p62 itself appears to be affected by MGO-induced glycation over time, forming high-molecular-weight complexes and losing its function. In other words, the autophagy-lysosome pathway (and possibly the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway) remains functional in the early stages of intracellular AGE formation, allowing for the proper clearance of AGEs. However, as glycation reactions continue, degradation pathways and other potential protective factors gradually transform into AGEs, resulting in a dysfunction in the AGE clearance pathway. This late stage of AGE formation may eventually induce apoptosis or passive, unprogrammed cell death by necrosis in affected cells [

16]. To the best of our knowledge, the induction of autophagy in the early stages of TAGE formation in cells has not yet been demonstrated.

We previously reported that the stimulation of a human pancreatic beta cell line (1.4E7 cells) with GA resulted in prominent cell death, accompanied by decreases in the autophagosome markers, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3-I) and LC3-II as well as p62 [

28]. These findings were observed after a prolonged stimulation (24 h) with 2 mM GA, at which stage cell death was already induced. Therefore, important factors involved in various vital functions were modified by TAGE, aggregated, and accumulated, suggesting that the TAGE degradation pathway was already disrupted in the late stage. To confirm the existence of an endogenous degradation and removal mechanism for TAGE, a detailed analysis of the behavior of degradation-related factors from the initial stage of a glycation stimulation is needed.

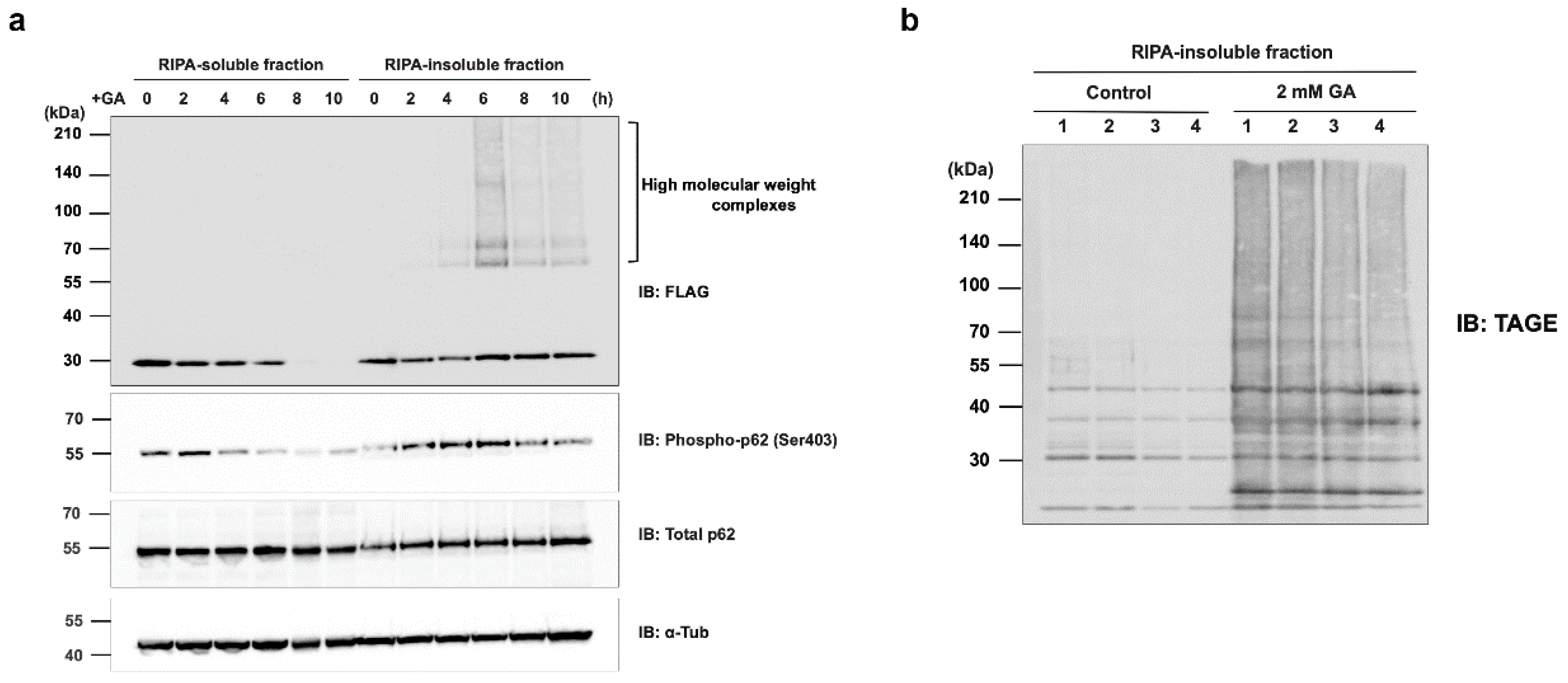

In the present study, we investigated the behavior of p62, a known selective autophagy receptor, over 10 h, starting 2 h after a stimulation with 2 mM GA. The results obtained revealed a slight change in total endogenous p62 levels (

Figure 7a). Since autophagy is responsible for the degradation of p62 when degrading its substrates, the accumulation of p62 is often observed when autophagy is impaired [

27]. However, total p62 levels remained unchanged after 10 h of the stimulation with 2 mM GA; therefore, the complete failure of autophagy had not yet occurred. p62 plays a key role in substrate degradation by recruiting ubiquitinated cargo to autophagosomes. The phosphorylation of the 403rd serine (Ser403) in the UBA domain of p62 by casein kinase-2 or TANK-binding kinase 1 increased its binding affinity to the ubiquitin chain, thereby facilitating selective autophagy [

39,

40].

Interestingly, after the GA stimulation for 2 h, a gradual decrease in the phosphorylated form of p62 Ser403 was observed in the RIPA-soluble fraction, in contrast to an increase over time in the RIPA-insoluble fraction (

Figure 7a). Most of the d270KD high-molecular-weight complexes formed by the GA stimulation were present in the RIPA-insoluble fraction, and the level of d270KD high-molecular-weight complexes in this fraction peaked at approximately 6 h of the GA stimulation, followed by a gradual decrease (

Figure 7a). Furthermore, the RIPA-insoluble fraction of cells that did not express d270KD but were stimulated with GA for 6 h also showed the abundant localization of high-molecular-weight complexes that were positive for TAGE antibodies (

Figure 7b). This result suggests that intracellular proteins modified with TAGE by GA form aggregates that have acquired resistance to detergents, such as SDS, and are more likely to become insoluble intracellularly. Furthermore, the binding of phosphorylated p62 to ubiquitinated TAGE may have been increased in the insoluble fraction, suggesting that the degradation system by selective autophagy was still partially functional during the initial stage of the GA stimulation, despite the formation of TAGE-modified aggregates.

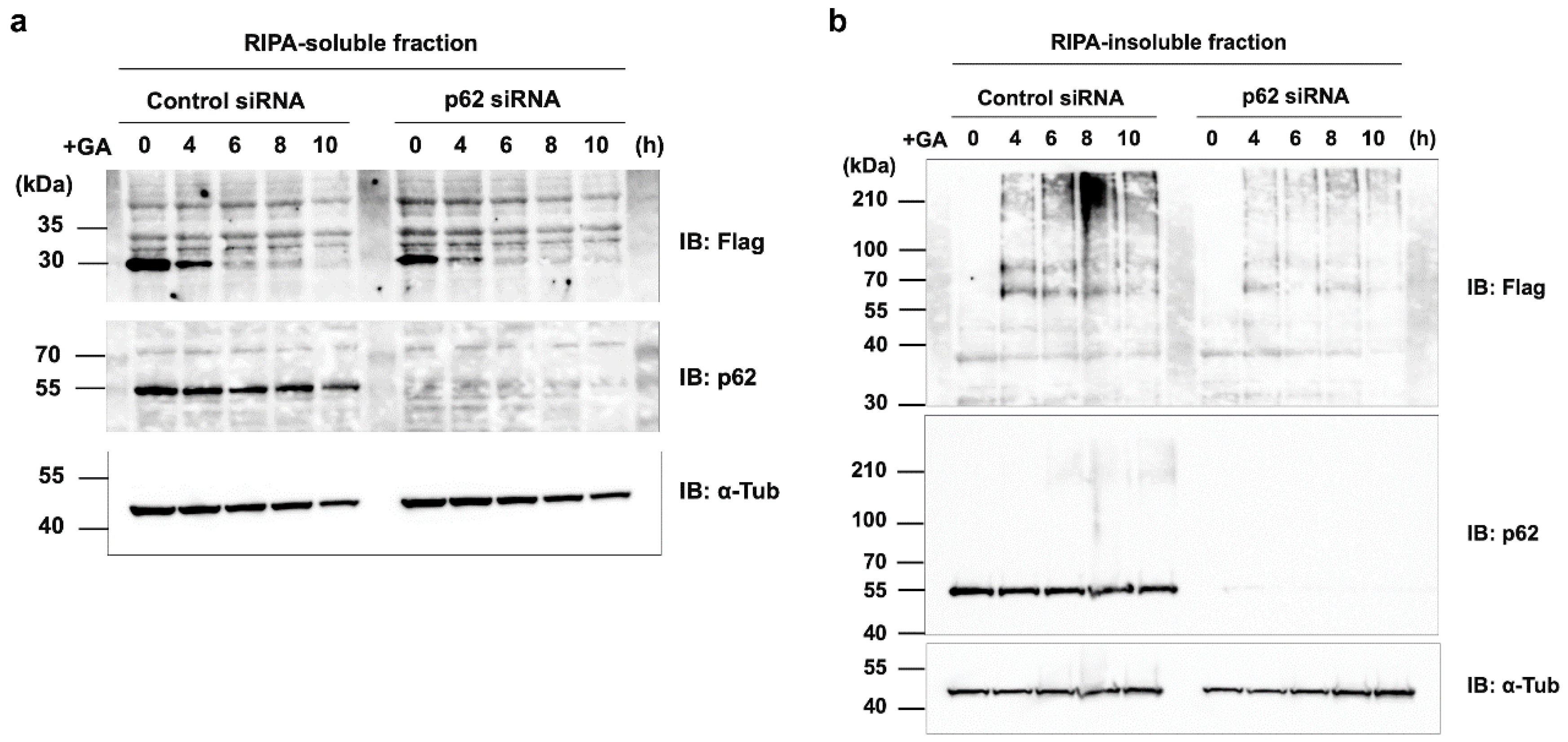

Overall, the present results highlight the importance of analyzing the behavior of degradation-related factors, such as p62, from the initial stage of a glycation stimulation to elucidate endogenous TAGE degradation and removal mechanisms. Further research is needed to clarify the complex interplay between TAGE formation, autophagy, and cellular responses to proteopathy, which will provide a more detailed understanding of the pathogenesis of TAGE-related cellular damage. Since proteasome inhibitors completely suppressed the GA-stimulated rapid degradation of d270KD (

Figure 5a), the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway may also work in conjunction with the autophagy pathway during the early stages of TAGE formation to maintain intracellular protein homeostasis, which is disrupted by glycation modifications. The knockdown of p62 did not affect the degradation of d270KD by GA, but modestly reduced the formation of high-molecular-weight complexes derived from d270KD in the insoluble fraction. Therefore, p62 may play a partial role in the formation of TAGE aggregates in the insoluble fraction. One hypothesis is that p62 may be involved in sequestering randomly formed TAGE throughout the cell by aggregating them, thereby preventing interference with the function of normal proteins and potentially protecting the cell. A more detailed analysis is needed on the subcellular localization of ubiquitinated and insoluble TAGE aggregates.

In conclusion, the present study provides novel insights into the intracellular degradation mechanism of TAGE and proposes potential therapeutic strategies to prevent or mitigate TAGE-related diseases. Further research in this area will contribute to the development of effective interventions for diseases associated with protein aggregation and the accumulation of AGEs, including diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular diseases.

Figure 1.

Effects of the GA treatment on TAGE formation in wild-type CHK1 and its constitutively inactive mutants. (a) Various CHK1 expression vectors with different molecular sizes and enzymatic activities, including wild-type CHK1 (Flag-Chk1WT), a constitutive kinase-dead mutant (Flag-KDmut), and its C-terminal deletion mutant (Flag-d270KD), were transfected into HeLa cells. Cells were stimulated with 4 mM GA for 20 h. Cytoplasmic proteins were extracted and TAGE modifications were analyzed by Western blotting. (b) In vitro TAGE modifications to the d270KD recombinant protein. A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells and cell lysates were extracted 24 h later. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Flag antibody to purify the Flag-d270KD recombinant protein, which was then reacted with 4 mM GA in vitro for 20 h. TAGE modifications to the d270KD recombinant protein were analyzed by Western blotting.

Figure 1.

Effects of the GA treatment on TAGE formation in wild-type CHK1 and its constitutively inactive mutants. (a) Various CHK1 expression vectors with different molecular sizes and enzymatic activities, including wild-type CHK1 (Flag-Chk1WT), a constitutive kinase-dead mutant (Flag-KDmut), and its C-terminal deletion mutant (Flag-d270KD), were transfected into HeLa cells. Cells were stimulated with 4 mM GA for 20 h. Cytoplasmic proteins were extracted and TAGE modifications were analyzed by Western blotting. (b) In vitro TAGE modifications to the d270KD recombinant protein. A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells and cell lysates were extracted 24 h later. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Flag antibody to purify the Flag-d270KD recombinant protein, which was then reacted with 4 mM GA in vitro for 20 h. TAGE modifications to the d270KD recombinant protein were analyzed by Western blotting.

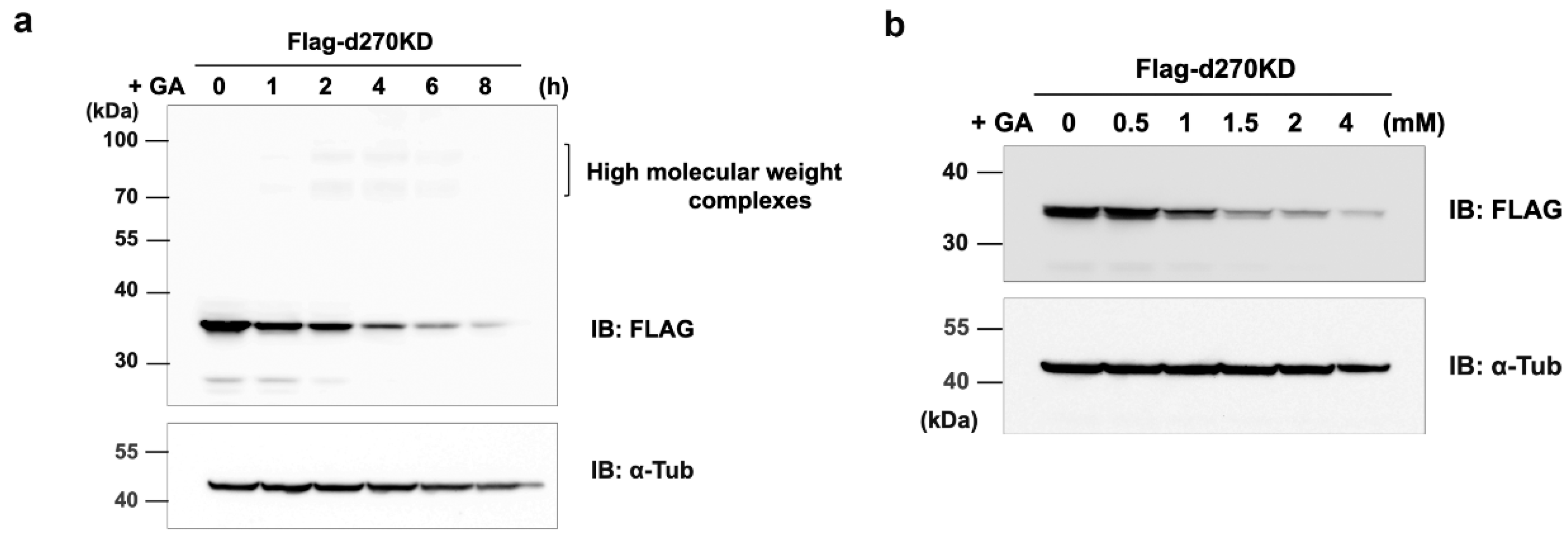

Figure 2.

GA-stimulated rapid degradation of the intracellular d270KD protein. (a) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells, and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times after 2 mM GA was applied to the cells 24 h later. Lysates were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (b) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells and cells were stimulated 24 h later with the indicated concentration of GA for 6 h. A Western blot analysis was performed on lysates collected from these cells as described above.

Figure 2.

GA-stimulated rapid degradation of the intracellular d270KD protein. (a) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells, and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times after 2 mM GA was applied to the cells 24 h later. Lysates were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (b) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells and cells were stimulated 24 h later with the indicated concentration of GA for 6 h. A Western blot analysis was performed on lysates collected from these cells as described above.

Figure 3.

GA-stimulated rapid intracellular degradation of d270KD fusion proteins to EGFP. (a) The expression vector of d270KD fusion EGFP (d270KD-EGFP) was transfected into COS-7 cells and stimulated with 4 mM GA 48 h later. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated times and subjected to a Western blot analysis. (b) COS-7 cells were transfected with the d270KD-EGFP expression vector for 24 h, stimulated with phosphate buffer (control) or 4 mM GA for 6 h, and then fixed. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 3.

GA-stimulated rapid intracellular degradation of d270KD fusion proteins to EGFP. (a) The expression vector of d270KD fusion EGFP (d270KD-EGFP) was transfected into COS-7 cells and stimulated with 4 mM GA 48 h later. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated times and subjected to a Western blot analysis. (b) COS-7 cells were transfected with the d270KD-EGFP expression vector for 24 h, stimulated with phosphate buffer (control) or 4 mM GA for 6 h, and then fixed. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Rapid proteolysis of d270KD-fused luciferase and its reduced activity upon a GA stimulation. (a) A d270KD fusion luciferase expression vector (d270KD-Luc) was transfected into HeLa cells and stimulated with 4 mM GA after 24 h. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated times and subjected to a Western blot analysis. (b) As in (a), d270KD-Luc was transfected into HeLa cells for 24 h and stimulated with GA at the indicated concentrations. Cell lysates collected at each indicated time were subjected to the luciferase assay. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with d270KD-Luc for 24 h and then pretreated with phosphate buffer or aminoguanidine (AG) at the indicated concentrations for 2 h. Cells were then stimulated with phosphate buffer or 2 mM GA for 6 h and lysed. Cell lysates were collected and luciferase activity was measured and expressed as 100 for the control. Each value was obtained from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *p <0.01 versus 2 mM GA alone. (d) Cell lysates treated similarly to the experiment in (c) were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the antibodies indicated.

Figure 4.

Rapid proteolysis of d270KD-fused luciferase and its reduced activity upon a GA stimulation. (a) A d270KD fusion luciferase expression vector (d270KD-Luc) was transfected into HeLa cells and stimulated with 4 mM GA after 24 h. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated times and subjected to a Western blot analysis. (b) As in (a), d270KD-Luc was transfected into HeLa cells for 24 h and stimulated with GA at the indicated concentrations. Cell lysates collected at each indicated time were subjected to the luciferase assay. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with d270KD-Luc for 24 h and then pretreated with phosphate buffer or aminoguanidine (AG) at the indicated concentrations for 2 h. Cells were then stimulated with phosphate buffer or 2 mM GA for 6 h and lysed. Cell lysates were collected and luciferase activity was measured and expressed as 100 for the control. Each value was obtained from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *p <0.01 versus 2 mM GA alone. (d) Cell lysates treated similarly to the experiment in (c) were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the antibodies indicated.

Figure 5.

Involvement of the proteasome pathway in the rapid degradation of d270KD by GA. (a) HeLa cells were transfected with the Flag-d270KD expression vector and cells were incubated 24 h later with 5 mM of a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) or DMSO (control) for 4 h. Cells were treated with 4 mM GA and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times for a Western blot analysis. (b) The GA stimulation increased the ubiquitination of d270KD-fused EGFP. The expression vector for the d270KD fusion EGFP (d270KD-EGFP) expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells for 48 h and cells were then treated with DMSO (control) or 5 µM MG132 for 3 h. Cells were collected after the stimulation with phosphate buffer or 4 mM GA for 3 h. Cell lysates were extracted under denaturing conditions, diluted in lysis buffer, and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-V5 antibody. Whole cell lysates (WCL) and IP samples were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Figure 5.

Involvement of the proteasome pathway in the rapid degradation of d270KD by GA. (a) HeLa cells were transfected with the Flag-d270KD expression vector and cells were incubated 24 h later with 5 mM of a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) or DMSO (control) for 4 h. Cells were treated with 4 mM GA and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times for a Western blot analysis. (b) The GA stimulation increased the ubiquitination of d270KD-fused EGFP. The expression vector for the d270KD fusion EGFP (d270KD-EGFP) expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells for 48 h and cells were then treated with DMSO (control) or 5 µM MG132 for 3 h. Cells were collected after the stimulation with phosphate buffer or 4 mM GA for 3 h. Cell lysates were extracted under denaturing conditions, diluted in lysis buffer, and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-V5 antibody. Whole cell lysates (WCL) and IP samples were subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Figure 6.

Effects of the elimination of Mule/HUWE1 E3 ubiquitin ligase on the rapid degradation of d270KD stimulated by GA (a) HeLa cells were transfected with scrambled control siRNA (control) or Mule/HUWE1 siRNA, treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 20 μg/mL) 48 h later, and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times. The resulting cell lysates were subjected to a Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (b, c) Scrambled control siRNA or Mule/HUWE1 siRNA was transfected into HeLa cells as in (a), and cells were transfected 24 h later with a full-length CHK1 expression vector fused with a Flag tag (b) or GFP-d270KD expression vector (c). Cells were treated 24 h later with cycloheximide (CHX; 20 μg/mL) (b) or 2 mM GA (c) for the indicated times, and cell lysates were collected for a Western blot analysis.

Figure 6.

Effects of the elimination of Mule/HUWE1 E3 ubiquitin ligase on the rapid degradation of d270KD stimulated by GA (a) HeLa cells were transfected with scrambled control siRNA (control) or Mule/HUWE1 siRNA, treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 20 μg/mL) 48 h later, and cell lysates were collected at the indicated times. The resulting cell lysates were subjected to a Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (b, c) Scrambled control siRNA or Mule/HUWE1 siRNA was transfected into HeLa cells as in (a), and cells were transfected 24 h later with a full-length CHK1 expression vector fused with a Flag tag (b) or GFP-d270KD expression vector (c). Cells were treated 24 h later with cycloheximide (CHX; 20 μg/mL) (b) or 2 mM GA (c) for the indicated times, and cell lysates were collected for a Western blot analysis.

Figure 7.

All high-molecular-weight complexes of d270KD formed by a GA stimulation accumulate in the insoluble fraction of RIPA. (a) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells, and cells were stimulated 24 h later with 2 mM GA and collected at the indicated times. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and separated into a supernatant (RIPA-soluble fraction) and pellet (RIPA-insoluble fraction) by centrifugation. After the addition of SDS sample buffer to each fraction, samples from both fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using the antibodies indicated. (b) HeLa cells were treated with phosphate buffer (control) or 2 mM GA. After 8 h, cells were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer. Each cell lysate was separated into RIPA-soluble/-insoluble fractions in the same manner as in (a). Samples of both fractions were prepared by four independent experiments and subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Figure 7.

All high-molecular-weight complexes of d270KD formed by a GA stimulation accumulate in the insoluble fraction of RIPA. (a) A Flag-d270KD expression vector was transfected into HeLa cells, and cells were stimulated 24 h later with 2 mM GA and collected at the indicated times. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and separated into a supernatant (RIPA-soluble fraction) and pellet (RIPA-insoluble fraction) by centrifugation. After the addition of SDS sample buffer to each fraction, samples from both fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using the antibodies indicated. (b) HeLa cells were treated with phosphate buffer (control) or 2 mM GA. After 8 h, cells were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer. Each cell lysate was separated into RIPA-soluble/-insoluble fractions in the same manner as in (a). Samples of both fractions were prepared by four independent experiments and subjected to a Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Figure 8.

Effects of the p62/SQSTM1 knockdown on the rapid GA-stimulated degradation of d270KD. HeLa cells were transfected with scrambled control siRNA or p62/SQSTM1 siRNA and transfected 24 h later with a Flag-d270KD expression vector. Cells were stimulated 24 h later with 2 mM GA for the indicated times. RIPA buffer was added to cells and cell lysates were separated into RIPA-soluble (a) and RIPA-insoluble (b) fractions by centrifugation. Each fraction was analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

Figure 8.

Effects of the p62/SQSTM1 knockdown on the rapid GA-stimulated degradation of d270KD. HeLa cells were transfected with scrambled control siRNA or p62/SQSTM1 siRNA and transfected 24 h later with a Flag-d270KD expression vector. Cells were stimulated 24 h later with 2 mM GA for the indicated times. RIPA buffer was added to cells and cell lysates were separated into RIPA-soluble (a) and RIPA-insoluble (b) fractions by centrifugation. Each fraction was analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies.