Submitted:

20 May 2023

Posted:

22 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and protocol

2.2. Body Size and BP Measurement

2.3. Assessment of 10-year risk of CV disease

2.4. Coronary calcium score (CAC)

2.5. Individuals with CAC score =0 and CAC score >100.

2.5.1. Vascular Examination

2.5.2. Statistical Analysis

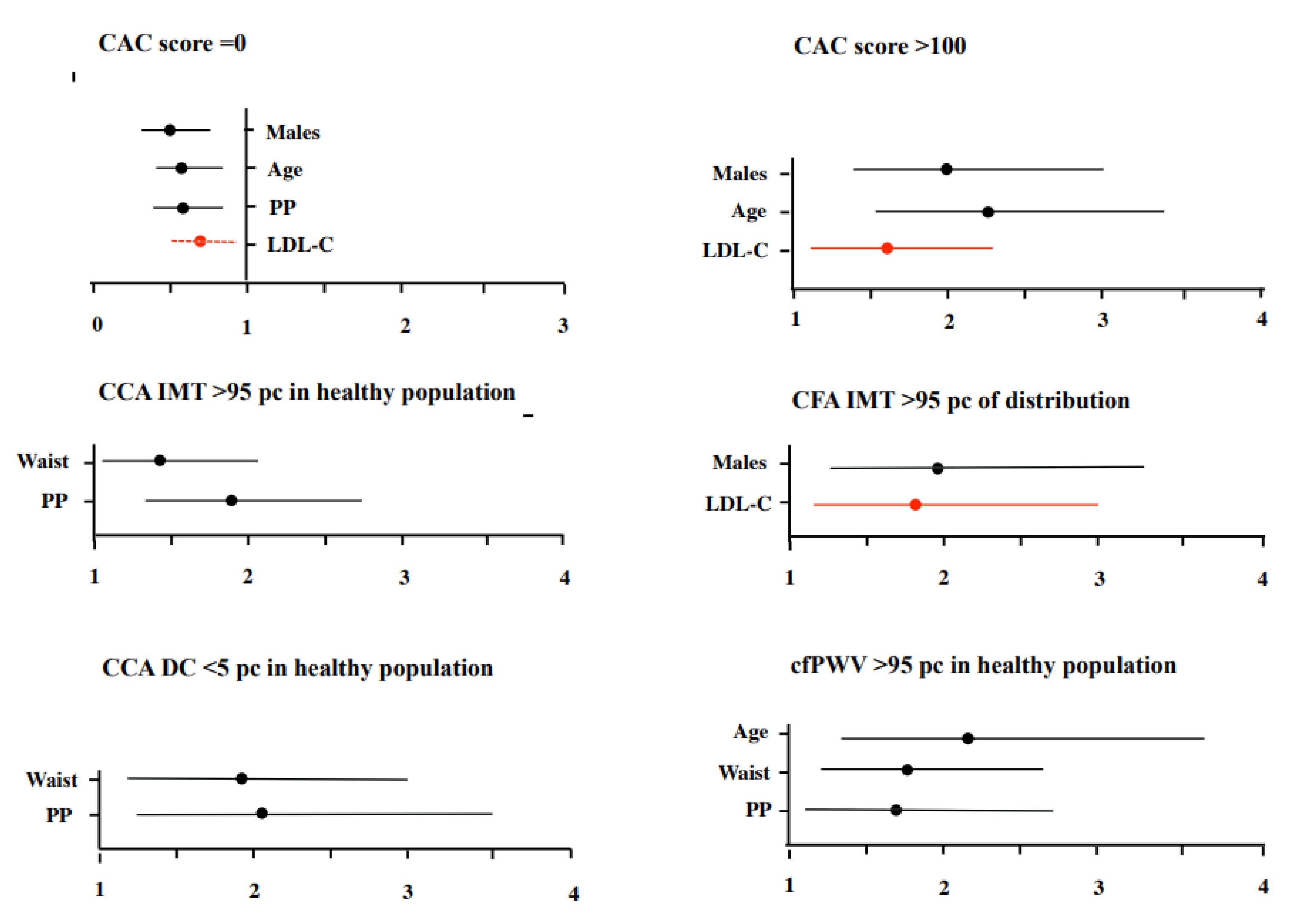

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Birgelen, C.; Hartmann, M.; Mintz, G.S.; Baumgart, D.; Schmermund, A.; Erbel, R. Relation between progression and regression of atherosclerotic left main coronary artery disease and serum cholesterol levels as assessed with serial long-term (> or =12 months) follow-up intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 2003, 108, 2757–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, S.E.; Nicholls, S.J.; Sipahi, I.; Libby, P.; Raichlen, J.S.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Davignon, J.; Erbel, R.; Fruchart, J.C.; Tardif, J.C.; Schoenhagen, P.; Crowe; Cain, V.; Wolski, K.; Goormastic, M.; Tuzcu, E.M.; ASTEROID Investigators. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Sipahi, I.; Grasso, A.W.; Schoenhagen, P.; Hu, T.; Wolski, K.; Crowe, T.; Desai, M.Y.; Hazen, S.L.; Kapadia, S.R.; Nissen, S.E. Statins, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and regression of coronary atherosclerosis. JAMA 2007, 297, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; Graham, I.M.; Halliday, A.; Landmesser, U.; Mihaylova, B.; Pedersen, T.R; Riccardi, G.; Richter, D.J.; Sabatine, M.S.; Taskinen, M.R.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Wiklund, O.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.M.; Choi, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, G.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.Y.; Son, J.S.; Yun, J.M.; Park, S.M. Effect of change in total cholesterol levels on cardiovascular disease among young adults. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7, e008819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; Michos, E.D.; Miedema, M.D.; Muñoz, D.; Smith, S.C. Jr.; Virani, S.S.; Williams, K.A. Sr.; Yeboah, J.; Ziaeian, B. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140, e596–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Shaw, L.J.; Shapiro, M.D.; Blankstein, R.; Hoffmann, U.; Cury, R.C.; Abbara, S.M; Brady, T.J.; Budoff, M.J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Nasir, K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009, 2, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Kioeng-Shioe, M.S.; Rijlaarsdam-Hermsen, D.; van Domburg, R.T.; Hadamitzky, M.; Lima, J.A.C.; Hoeks, S.E.; Deckers, J.W. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium score in symptomatic individuals: A meta-analysis of 34,000 subjects. Int J Cardiol 2020, 299, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.; Granåsen, G.; Wiklund, U.; Schmermund, A.; Guerci, A.; Erbel, R.; Raggi, P. High dose and long-term statin therapy accelerate coronary artery calcification. Int J Cardiol 2015, 184, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykun, I.; Lehmann, N.; Kälsch, H.; Möhlenkamp, S.; Moebus, S.; Budde, T.; Seibel, R.; Grönemeyer, D.; Jöckel, K.H.; Erbel, R.; Mahabadi, A.A. Statin medication enhances progression of coronary artery calcification: The Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 2123–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovanni, G.; Nicholls, S.J. Intensive lipid lowering agents and coronary atherosclerosis: Insights from intravascular imaging. Am J Prev Cardiol 2022, 11, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.P.; Einstein, A.J.; Berrington de González, A. Coronary artery calcification screening: estimated radiation dose and cancer risk. Arch Intern Med 2009, 169, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, J.R., 3rd; Raichlen, J.S.; Riley, W.A.; Evans, G.W.; Palmer, M.K.; O'Leary, D.H.; Grobbee, D.E.; Bots, M.L.; METEOR Study Group. Effect of rosuvastatin on progression of carotid intima-media thickness in low-risk individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis: the METEOR Trial. JAMA 2007, 297, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daida, H.; Nohara, R.; Hata, M.; Kaku, K.; Kawamori, R.; Kishimoto, J.; Kurabayashi, M.; Masuda, I.; Sakuma, I.; Yamazaki, T.; Yokoi, H.; Yoshida, M.; Justification for Atherosclerosis Regression Treatment (JART) Investigators. Can intensive lipid-lowering therapy improve the carotid intima-media thickness in Japanese subjects under primary prevention for cardiovascular disease?: The JART and JART extension subanalysis. J Atheroscler Thromb 2014, 21, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilde, T.J.; van den Berkmortel, F.W.; Wollersheim, H.; van Langen, H. Kastelein, J.J.; Stalenhoef, A.F. The effect of cholesterol lowering on carotid and femoral artery wall stiffness and thickness in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Eur J Clin Invest 2000, 30, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upala, S.; Wirunsawanya, K.; Jaruvongvanich, V.; Sanguankeo, A. Effects of statin therapy on arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Int J Cardiol 2017, 227, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koushki, K.; Shahbaz, S.K.; Mashayekhi, K.; Sadeghi, M.; Zayeri, Z.D.; Taba, M.Y.; Banach, M.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Anti-inflammatory action of statins in cardiovascular disease: the role of inflammasome and toll-like receptor pathways. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021, 60, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davignon, J.; Jacob, R.F.; Mason, R.P. The antioxidant effects of statins. Coron Artery Dis 2004, 15, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.K.; Laufs, U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2005, 45, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellosta, S.; Arnaboldi, L.; Gerosa, L.; Canavesi, M.; Parente, R.; Baetta, R.; Paoletti, R.; Corsini, A. Statins effect on smooth muscle cell proliferation. Semin Vasc Med 2004, 4, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzullo, P.; Kerry, S.M.; Barbato, A.; Versiero, M.; D'Elia, L.; Cappuccio, F.P. Do statins reduce blood pressure?: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension 2007, 49, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, C.; Xaplanteris, P.; Aboyans, V.; Brodmann, M.; Cífková, R.; Cosentino, F.; De Carlo, M.; Gallino, A.; Landmesser, U.; Laurent, S.; Lekakis, J.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Naka, K.K.; Protogerou, A.D.; Rizzoni, D.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Van Bortel, L.; Weber, T.; Yamashina, A.; Zimlichman, R.; Boutouyrie, P.; Cockcroft, J.; O'Rourke, M.; Park, J.B.; Schillaci, G.; Sillesen, H.; Townsend, R.R. The role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary prevention. A position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripheral circulation: Endorsed by the Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology (ARTERY) Society. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasan, R.S. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: molecular basis and practical considerations. Circulation 2006, 113, 2335–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redón, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Böhm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; Galderisi, M.; Grobbee, D.E.; Jaarsma, T.; Kirchhof, P.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Laurent, S.; Manolis, A.J.; Nilsson, P.M.; Ruilope, L.M.; Schmieder, R.E.; Sirnes, P.A.; Sleight, P.; Viigimaa, M.; Waeber, B.; Zannad, F.; Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013, 31, 1281–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino, R.B. Sr; Vasan, R.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Cobain, M.; Massaro, J.M.; Kannel, W.B. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agatston, A.S.; Janowitz, W.R; Hildner, F.J.; Zusmer, N.R.; Viamonte, M. Jr.; Detrano, R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990, 15, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, L.; Bossuyt, J.; Ferreira, I.; van Bortel, L.M.; Reesink, K.D.; Segers, P.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. Reference Values for Arterial Measurements Collaboration. Reference values for local arterial stiffness. Part A: carotid artery. J Hypertens 2015, 33, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, L.; Ferreira, I.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Boutouyrie, P.; Laurent, S. Reference Values for Arterial Measurements Collaboration. Reference intervals for common carotid intima-media thickness measured with echotracking: relation with risk factors. Eur Heart J 2013, 34, 2368–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bortel, L.M.; Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Cruickshank, J.K.; De Backer, T.; Filipovsky, J.; Huybrechts, S.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.; Protogerou, A.D.; Schillaci, G.; Segers, P.; Vermeersch, S.; Weber, T.; Artery Society; European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Vascular Structure and Function; European Network for Noninvasive Investigation of Large Arteries. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens 2012, 30, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, M.P.; Cunha, R.S.; Molina, M.D.C.B.; Chór, D.; Griep, R.H.; Duncan, B.B.; Schmidt, M.I.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Barreto, S.M.; Lotufo, P.A.; Bensenor, I.M.; Pereira, A.C.; Mill, J.G. Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in a healthy adult sample: The ELSA-Brasil study. Int J Cardiol 2018, 251, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demer, L.L. Cholesterol in vascular and valvular calcification. Circulation 2001, 104, 1881–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhami, F.; Morrow, A.D.; Balucan, J.; Leitinger, N.; Watson, A.D.; Tintut, Y.; Berliner, J.A; Demer, L.L. Lipid oxidation products have opposite effects on calcifying vascular cell and bone cell differentiation: a possible explanation for the paradox of arterial calcification in osteoporotic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997, 17, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shioi, A.; Ikari, Y. Plaque calcification during atherosclerosis progression and regression. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018, 25, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, R.; Ju, J.; Lin, Q.; Xu, H. Coronary artery calcification under statin therapy and its effect on cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 600497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakova, M.; Morizzo, C.; Guarino, D.; Federico, G.; Miccoli, M.; Giannattasio, C.; Palombo, C. The impact of age and risk factors on carotid and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens 2015, 33, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiesa, S.T.; Charakida, M.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Dangardt, F.; Wade, K.H.; Rapala, A.; Bhowruth, D.J.; Nguyen, H.C.; Muthurangu, V.; Shroff, R.; Davey Smith, G.; Lawlor, D.A.; Sattar, N.; Timpson, N.J.; Hughes, A.D.; Deanfield, J.E. Determinants of intima-media thickness in the young: The ALSPAC Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021, 14, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakova, M.; Palombo, C.; Paterni, M.; Anderwald, C.H.; Konrad, T.; Colgan, M.P.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Dekker, J.; Relationship between Insulin Sensitivity Cardiovascular risk Investigators. Body composition and common carotid artery remodeling in a healthy population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93, 3325–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, L.E. Blood pressure-lowering effects of statins: who benefits? J Hypertens 2009, 27, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briasoulis, A.; Agarwal, V.; Valachis, A.; Messerli, F.H. Antihypertensive effects of statins: a meta-analysis of prospective controlled studies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2013, 15, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steene-Johannessen, J.; Kolle, E.; Reseland, J.E.; Anderssen, S.A.; Andersen, L.B. Waist circumference is related to low-grade inflammation in youth. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010, 5, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, D.; Jones, J.; Barona, J.; Calle, M.C.; Kim, J.E.; LaPia, B.; Volek, J.S.; McIntosh, M.; Kalynych, C.; Najm, W.; Lerman, R.H.; Fernandez, M.L. Waist circumference is positively correlated with markers of inflammation and negatively with adiponectin in women with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res 2011, 3, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gariepy, J.; Salomon, J.; Denarié, N.; Laskri, F.; Mégnien, J.L.; Levenson, J.; Simon, A. Sex and topographic differences in associations between large-artery wall thickness and coronary risk profile in a French working cohort: the AXA Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998, 18, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gariepy, J.; Simon, A.; Massonneau, M.; Linhart, A.; Levenson, J. Wall thickening of carotid and femoral arteries in male subjects with isolated hypercholesterolemia. PCVMETRA Group. Prevention Cardio-Vasculaire en Medecine du Travail. Atherosclerosis 1995, 113, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sauvage Nolting, P.R.; de Groot, E.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Buirma, R.J.; Trip, M.D.; Kastelein, J.J. Regression of carotid and femoral artery intima-media thickness in familial hypercholesterolemia: treatment with simvastatin. Arch Intern Med 2003, 163, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean±SD, Median[IR], n(%) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Male:Female | 119(46):141(54) | |

| Age (years) | 63±6 | 50-74 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9±3.9 | 17.3-51.7 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95±11 | 67-147 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 136±14 | 105-180 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 61±13 | 30-95 |

| Total cholesterol (mmo/L) | 5.45±0.78 | 3.28-6.88 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmo/L) | 3.42±0.6 | 1.66-4.85 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmo/L) | 1.58±0.37 | 0.89-2.64 |

| Triglycerides (mmo/L) | 0.89[0.75] | 0.23-3.89 |

| Fasting glucose (mmo/L) | 5.36±0.49 | 4.44-6.77 |

| Current smoking (yes) | 43(17) | |

| Hypertension (yes) | 113(43) | |

| Hypertensive treatment (yes) | 38(15) |

| Mean±SD, n(%) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| CAC score =0 | 174(67) | |

| CAC score >100 | 36(14) | |

| CCA IMT (microns) | 731±135 | 459-1202 |

| CCA IMT >95th percentile | 45(17) | |

| CCA DC (10-3kPa-1) | 14.2±4.5 | 4.31-30.2 |

| CCA DC <5th percentile | 15(6) | |

| CFA IMT (microns) | 736±202 | 340-1671 |

| CFA IMT >95th percentile | 25(10) | |

| cfPWV (m/s) (n=182) | 9.4±2.4 | 4.1-23.6 |

| cfPWV >95th percentile (n=182) | 27(15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).