Submitted:

17 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

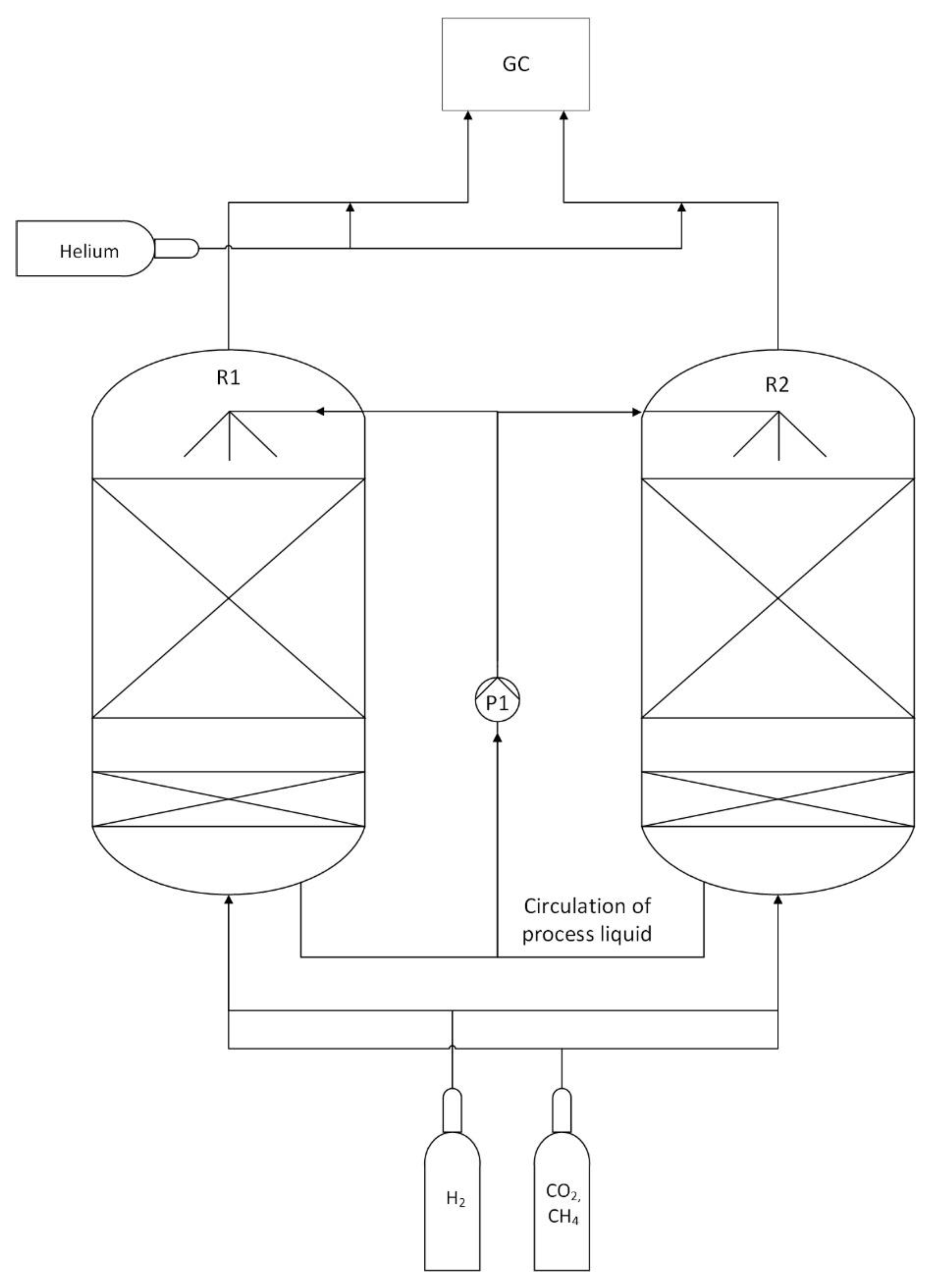

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Design of Experiment

2.3. Analytical

2.4. Calculations

- Methane formation rate (MFR);

- Gas hourly space velocity (GHSV);

- Retention time (RT);

- and the conversion rates of H2 and CO2.

3. Results and discussion

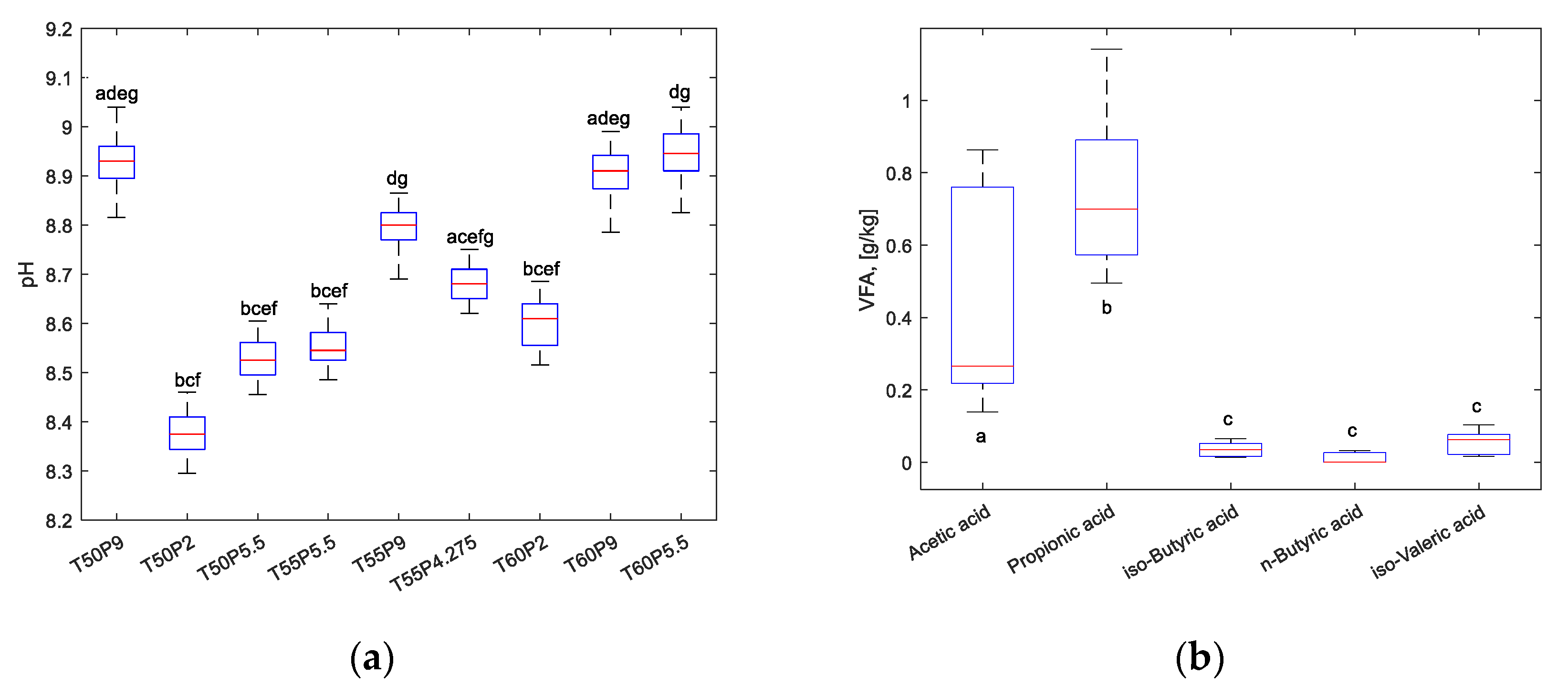

3.1. Operation and performance parameters

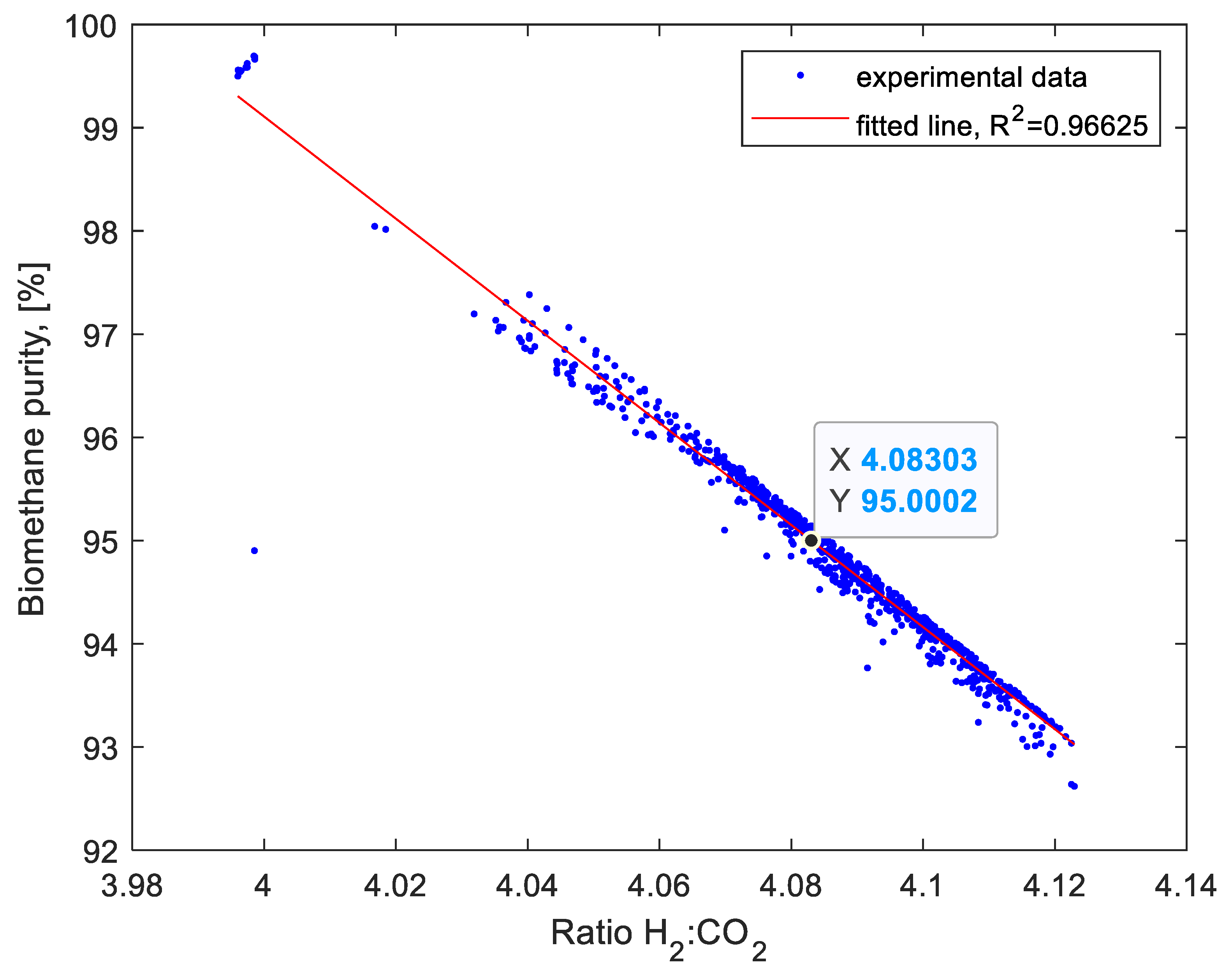

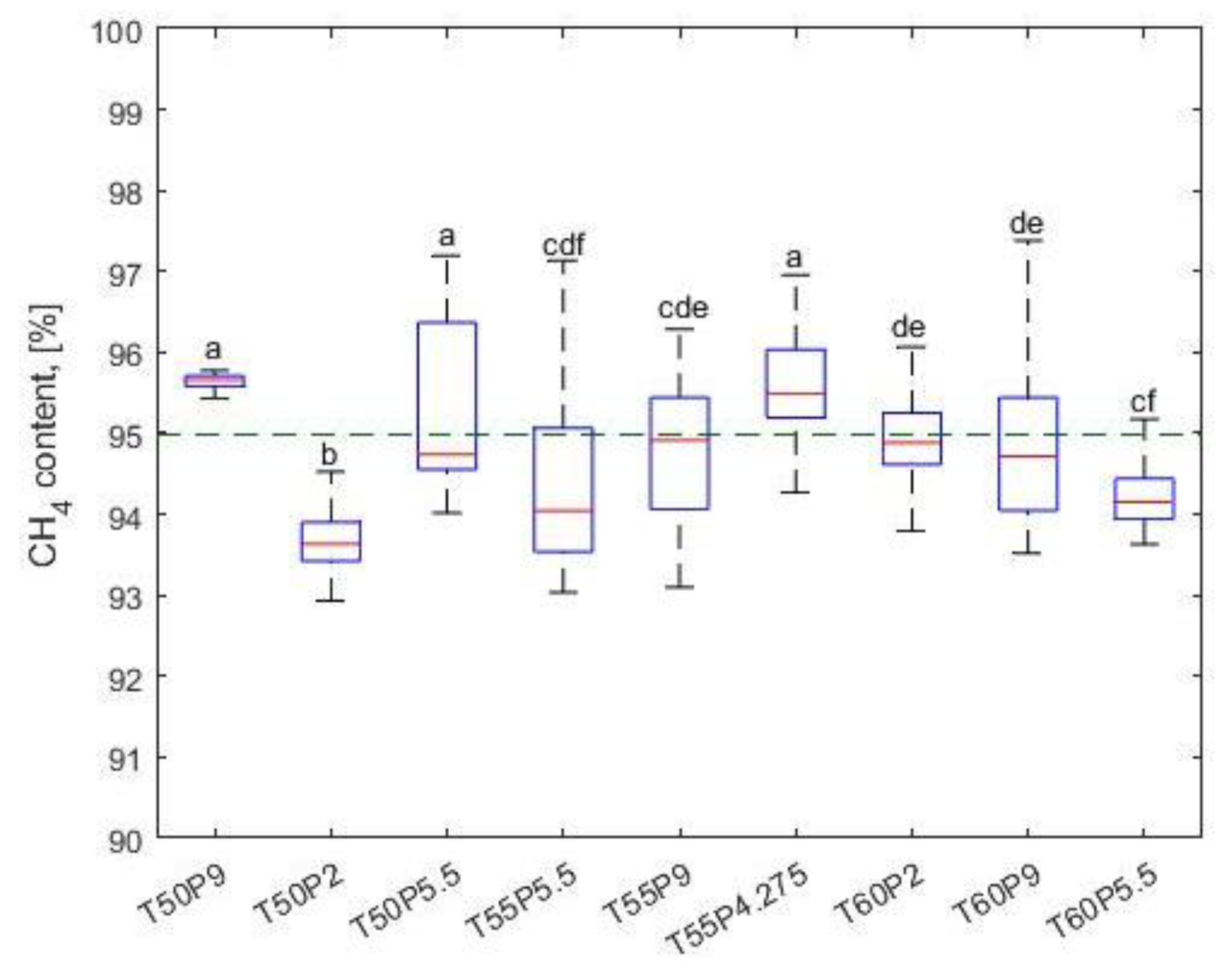

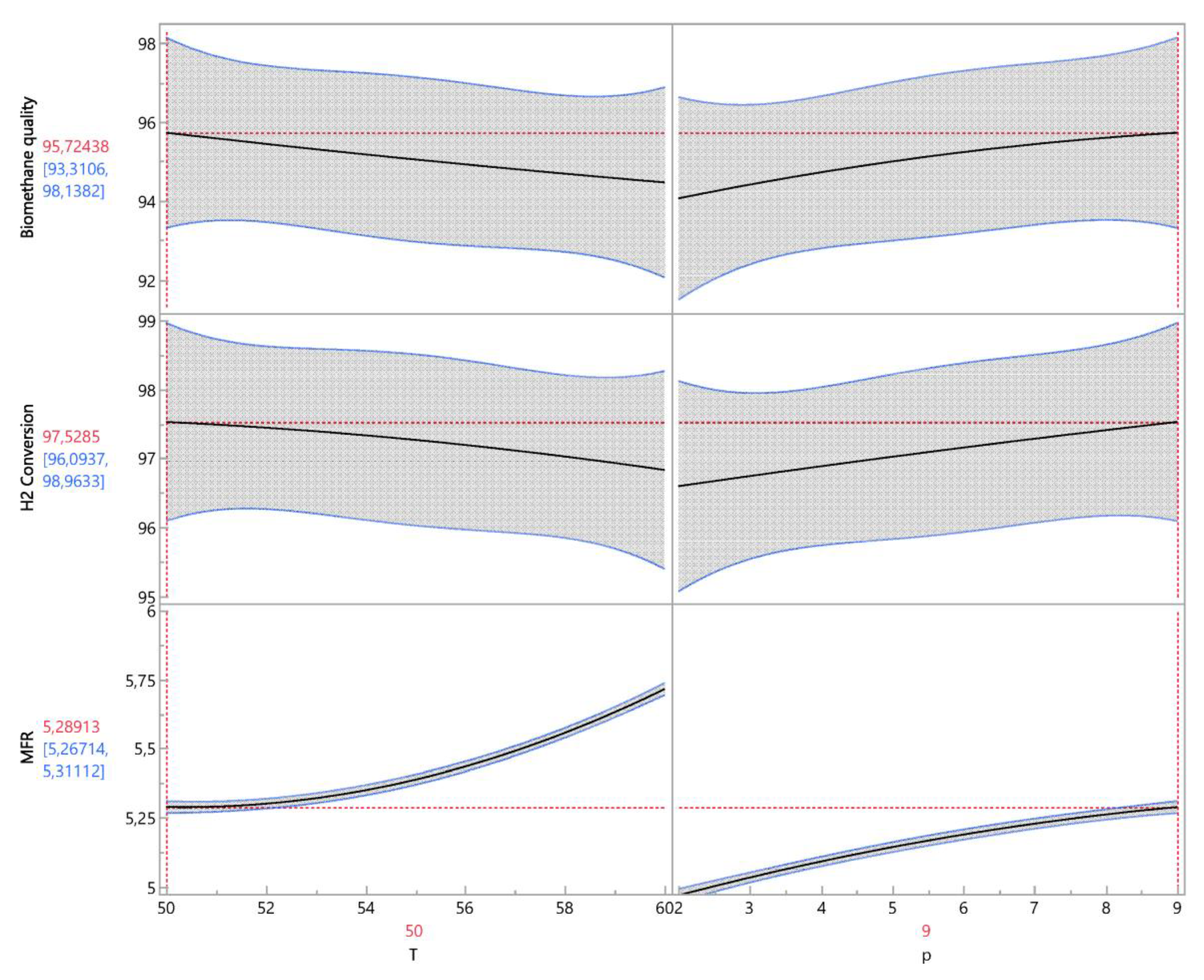

3.2. Optimizing operating parameters

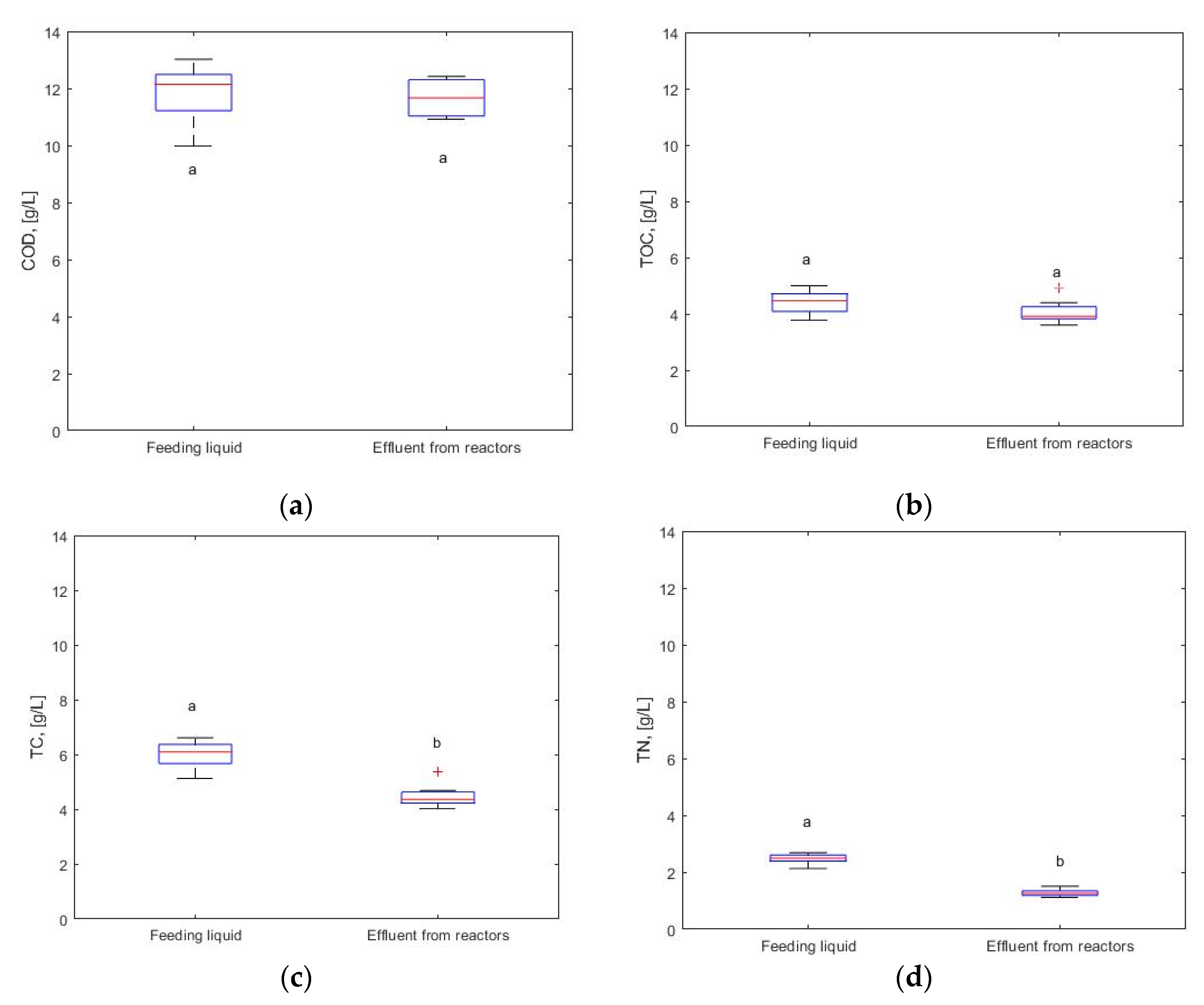

3.3. Analysis of the process liquid

5. Conclusions and outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wellinger, A.; Murphy, J.; Baxter, D. The biogas handbook: Science, production and applications/edited by Arthur Wellinger, Jerry Murphy and David Baxter; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Oxford, 2013; ISBN 9780857097415. [Google Scholar]

- Miltner, M.; Makaruk, A.; Harasek, M. Review on available biogas upgrading technologies and innovations towards advanced solutions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 161, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkmans, L. Implementation of bioenergy in Germany. 2021, 2021.

- Germand Technical and Scientific Associarion for Gas and Water. Germand Technical and Scientific Associarion for Gas and Water. Technical Rule - Standard: Gas Quality, A.; Economic and Publishing Company Gas and Water: Bonn, 2021 (G 260). Available online: https://shop.wvgw.de/G-260-Technical-Rule-09-2021/511831 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Angelidaki, I.; Xie, L.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Oechsner, H.; Lemmer, A.; Munoz, R.; Kougias, P.G. Chapter 33 - Biogas Upgrading: Current and Emerging Technologies: Biofuels: Alternative Feedstocks and Conversion Processes for the Production of Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels, Second edition; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-12-816856-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, T.; Lindner, J.; Bär, K.; Mörs, F.; Graf, F.; Lemmer, A. Influence of operating pressure on the biological hydrogen methanation in trickle-bed reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, A.; Ullrich, T. Effect of Different Operating Temperatures on the Biological Hydrogen Methanation in Trickle Bed Reactors. Energies 2018, 11, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, T.; Lemmer, A. Performance enhancement of biological methanation with trickle bed reactors by liquid flow modulation. GCB Bioenergy 2018, 11, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strübing, D.; Huber, B.; Lebuhn, M.; Drewes, J.E.; Koch, K. High performance biological methanation in a thermophilic anaerobic trickle bed reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhardt, M.; Koschack, T.; Busch, G. Biocatalytic methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide in an anaerobic three-phase system. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, P.P.; Lindner, J.; Oechsner, H.; Lemmer, A. Effects of target pH-value on organic acids and methane production in two-stage anaerobic digestion of vegetable waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmanis, D.; O'Shea, R.; Wall, D.M.; Murphy, J.D. Biological hydrogen methanation systems - an overview of design and efficiency. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 604–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrell, K.F.; Kalmokoff, M.L. Nutritional requirements of the methanogenic archaebacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 1988, 34, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerholm, M.; Isaksson, S.; Karlsson Lindsjö, O.; Schnürer, A. Microbial community adaptability to altered temperature conditions determines the potential for process optimisation in biogas production. Applied Energy 2018, 226, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chang, S. Dissecting methanogenesis for temperature-phased anaerobic digestion: Impact of temperature on community structure, correlation, and fate of methanogens. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.; Goos, P. I-Optimal Versus D-Optimal Split-Plot Response Surface Designs. Journal of Quality Technology 2012, 44, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, M.; Lefebvre, J.; Mörs, F.; McDaniel Koch, A.; Graf, F.; Bajohr, S.; Reimert, R.; Kolb, T. Renewable Power-to-Gas: A technological and economic review. Renewable Energy 2016, 85, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froment, Gilbert F. and Kenneth B. Bischoff. Chemical Reactor Analysis and Design. 1979.

- Thema, M.; Weidlich, T.; Hörl, M.; Bellack, A.; Mörs, F.; Hackl, F.; Kohlmayer, M.; Gleich, J.; Stabenau, C.; Trabold, T.; et al. Biological CO2-Methanation: An Approach to Standardization. Energies 2019, 12, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposob, M.; Wahid, R.; Fischer, K. Ex-situ biological CO2 methanation using trickle bed reactor: review and recent advances. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2021, 20, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Angelidaki, I. Integrated biogas upgrading and hydrogen utilization in an anaerobic reactor containing enriched hydrogenotrophic methanogenic culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 2729–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Xu, F.; Ge, X.; Li, Y. Biological treatment of organic materials for energy and nutrients production—Anaerobic digestion and composting; Elsevier: 2019; pp 121–181, ISBN 9780128177105.

| Run ID | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [bar] |

|---|---|---|

| T50P9 | 50 | 9 |

| T50P2 | 50 | 2 |

| T50P5.5 | 50 | 5.5 |

| T55P5.5 | 55 | 5.5 |

| T55P9 | 55 | 9 |

| T55P4.275 | 55 | 4.275 |

| T60P2 | 60 | 2 |

| T60P9 | 60 | 9 |

| T60P5.5 | 60 | 5.5 |

| Parameters | T50P9 | T50P2 | T50P5.5 | T55P5.5 | T55P9 | T55P4.275 | T60P2 | T60P9 | T60P5.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | 49.801 ± 0.284 | 50.065 ± 0.231 | 50.145 ± 0.201 | 54.983 ± 0.250 | 54.879 ± 0.264 | 54.952 ± 0.253 | 59.742 ± 0.297 | 59.990 ± 0.0 | 59.99 ± 0.0 |

| Pressure [bar] | 9.012 ± 0.018 | 2.061 ± 0.016 | 5.512 ± 0.013 | 5.480 ± 0.022 | 8.998 ± 0.018 | 4.288 ± 0.016 | 2.028 ± 0.011 | 9.046 ± 0.018 | 5.535 ± 0.013 |

| pH | 8.921 ± 0.128 | 8.458 ± 0.101 | 8.689 ± 0.131 | 8.745 ± 0.106 | 8.837 ± 0.082 | 8.762 ± 0.111 | 8.673 ± 0.106 | 9.013 ± 0.088 | 8.949 ± 0.138 |

| Flow rate H2 [L/h] | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 | 11.250 |

| Flow rate CO2 [L/h] | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.81 |

| Flow rate CH4 [L/h] | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.44 |

| MFR [m3/(m3·d)] | 6.376 ± 0.369 | 5.545 ± 0.224 | 5.687 ± 0.266 | 5.701 ± 0.186 | 5.755 ± 0.337 | 5.794 ± 0.363 | 6.076 ± 0.229 | 5.906 ± 0.241 | 6.001 ± 0.386 |

| CH4total1 [%] | 95.614 ± 0.151 | 93.675 ± 0.452 | 95.614 ± 1.632 | 94.386 ± 1.137 | 94.784 ± 0.781 | 95.626 ± 0.563 | 95.015 ± 0.714 | 94.929 ± 0.992 | 94.214 ± 0.360 |

| CH4conv2 [%] | 48.102 ± 1.017 | 46.574 ± 0.996 | 47.425 ± 1.543 | 47.584 ± 1.670 | 48.483 ± 1.657 | 47.285 ± 0.834 | 47.203 ± 1.201 | 50.000 ± 1.443 | 48.873 ± 0.965 |

| H2:CO2 | 4.072 ± 0.003 | 4.106 ± 0.009 | 4.068 ± 0.031 | 4.095 ± 0.024 | 4.089 ± 0.015 | 4.070 ± 0.013 | 4.083 ± 0.014 | 4.087 ± 0.0719 | 4.100 ± 0.007 |

| H2conv [%] | 97.535 ± 0.166 | 96.394 ± 0.274 | 97.288 ± 0.579 | 96.790 ± 0.827 | 97.042 ± 0.525 | 97.608 ± 0.382 | 97.127 ± 0.354 | 97.115 ± 0.679 | 96.616 ± 0.264 |

| CO2conv [%] | 99.767 ± 0.026 | 99.600 ± 0.137 | 99.569 ± 0.164 | 99.820 ± 0.085 | 99.884 ± 0.033 | 99.784 ± 0.081 | 99.811 ± 0.037 | 99.942 ± 0.008 | 99.895 ± 0.021 |

| RT [h] | 5.579 | 1.240 | 3.409 | 3.357 | 5.494 | 2.610 | 1.203 | 5.411 | 3.307 |

| GHSV [1/h] | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).