1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic may have been accompanied by an increase in interpersonal violence, harmful use of alcohol and other drugs (AOD), and mental health problems (1, 2). However, reports on the prevalence or incidence of violence, AOD, and mental health conditions have been based on separate studies conducted at the start of the pandemic or found in data obtained earlier, suggesting unclear directionality on relationships between these harmful effects. Clarity on the relationship between involvement in interpersonal and intimate violence, AOD, and suffering from mental health problems in youth will make it possible to design effective, efficient public health policies and preventive intervention strategies during health emergencies.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO; 3) identified higher rates of Years Lived with Disability (YLD) due to interpersonal and intimate violence in America between 2000 and 2019. It observed a rate of 59.8 YLDs per 100,000 population, 79.8 in women and 41.2 in men in 2019. According to The World Drug Report of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC; 4), there was a 26% increase in the prevalence of drugs used between 2010 and 2020, based on previous and initial data during the pandemic. Layman et al. (5), however, found that AOD trends seemed to vary in each country due to the pandemic between 2020 and 2022. Regarding mental health issues, the World Health Organization (WHO; 1) reported a 25% increase in depression and anxiety, while Bourmistrova et al. (6) observed a prevalence of 20.39% for depression, 18.85% for anxiety, and 18.99% for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, after one or more months of being severely ill from COVID-19, based on a systematic review of 2019-2021 papers.

In Mexico, data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, (INEGI, 7) identified a four-point increase in total lifetime violence against women between 2016 and 2021 (from 66.1% to 70.10%). In their Mental Health and Substance Abuse Observer System (NCA-MHSAMOS), the National Committee on Addictions (8) noted that, during the pandemic, 2.6% of Mexicans reported experiencing an increase in interpersonal violence, with 19.80%, 18.7%, and 3.1% increasing their use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs, respectively. It also concluded that these increases are due to anxiety (15.9%) or stress conditions (17.7%). Reports suggest rising trends or a high prevalence of violence, AOD, and mental health illness. Systematic reviews have suggested relationship directionalities that could be considered to improve public mental health policies and cost-effective preventions and treatment interventions (9).

Interpersonal and intimate violence consists of these behaviors within a relationship, causing physical, sexual, or psychological harm and including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors (10; 11; 12; 2). According to Johnson (13), Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (14), Weathers, Blake et al. (15), and Scott-Storey et al. (16), interpersonal and intimate violence definitions include victimizing and perpetrating physical assault (such as being attacked, hitting, slapping, kicking, beating up, threatening, isolating, or intimately abusing), assault with a weapon (such as being shot, stabbed, threatened or threatening with a knife, gun, or bomb), sexual assault (being raped or raping, attempting rape, or performing any type of sexual act through force or threat of harm), and any other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experience. Victimizing or perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence therefore includes everything from the least severe form of violence, through sexual or psychological abuse, to severe mixed violence, both inside and outside the home, exhibiting traits of victimization, or the perpetration of abuse.

Research has focused on victimizing intimate abuse against women as the most prominent form of interpersonal violence during the COVID-19 pandemic (11; 16). White et al. (9) systematically reviewed 2012-2020 research and reported higher lifetime intimate violence prevalence rates among women over sixteen than during the previous year. Nearly four out of every ten women reported experiencing intimate violence during their lifetime, and one in four had done so in the previous year. They concluded that women in the community had the highest prevalence of victimization through physical, psychological, and sexual violence in the previous year compared to clinical groups. Kourti et al. (11) recently reported that the pandemic had caused an increase in domestic violence cases, particularly during the first week of lockdown in 2020.

Glowacz et al. (17) also studied the types of intimate violence associated with participants´ sex or age during the first year of the pandemic. They reported that the prevalence of victimizing physical assault was higher in men (12.30%), whereas the prevalence of victimizing psychological violence was higher in adult women (35.20%). Scott-Storey and collaborators (16) conclude that it is more important to address forms of violence than the different prevalence between the sexes. They suggest that forms of violence are the result of perceived violence in men and women. They note that essential differences in how men perceive victimizing intimate violence appear to be more related to emotional and sexual forms than to physical abuse received when, for example, retaliation or marital conflicts involve children as witnesses in conflicts. Glowacz et al. (17) have also posited that younger adults involved in a relationship were more likely to experience or perpetrate physical and psychological violence during lockdown. The authors also showed that younger adults involved in relationships reported anxiety and depression symptoms associated with violence.

Studies on the prevalence of substance use and mental health among youth populations during the first year of the pandemic have observed an increase in alcohol, cannabis, nonprescription medical drugs, and nicotine use (18) and high rates of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among 12 to 18-year-old participants (19). One in five adolescents, regardless of sex, engaged in regular (i.e., once a week or more) use of at least one psychoactive substance, while 52% of adolescents met the clinical criterion for depression, 39% for anxiety, and 46% for PTSD during 2020 (19).

The direction of the association between violence, AOD, and mental health symptoms has been suggested by pre-pandemic data and studies addressing one or two variables in 2020. Brabete and collaborators (20) reported that AOD use, and mental health symptoms are consequences of victimizing intimate violence. Machisa and Shamu (21) pointed out that one in two women who experienced victimizing intimate physical or sexual violence had consumed alcohol and that one in four had binge-drunk during the previous year. Victimizing intimate violence has also been associated with an increased likelihood of using marijuana, stimulants, and other psychoactive substance (20). Craig et al. (19), Glowacz et al. (17), and White et al. (9) also stated that youth experiencing violence at home suffered depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms, before or during the first year of the pandemic. Harmful AOD use and mental health symptoms have therefore been associated with victimizing intimate violence among young men and women, pre-first pandemic year.

Drug use has also been studied as a predictor of interpersonal and intimate violence and mental health conditions based on pre-pandemic data. AOD use could predict being a victim or perpetrating intimate violence (22; 23). Dos-Santos and collaborators (24) reported that a history of AOD use was associated with being a victim of psychological, physical, and intimate partner sexual violence. Barchi et al. (25) reported that young women were 10.98 times more likely to experience victimizing physical intimate violence and 4.6 times more likely to experience psychological violence when both partners drink alcohol. In regard to perpetrating violence, Zhong et al. (26) reported a higher odds ratio of violence among those with AOD disorders, based on a systematic 1990-2019 review. The authors observed that individuals with a diagnosed AOD disorder have a 4-to-10-fold higher risk of perpetrating interpersonal violence compared with general populations without a drug use disorder. Cannabis, hallucinogens, stimulants, opioids, and sedatives were associated with a high risk of violence. It seems, however, that interpersonal violence rather than intimate partner violence was the result of AOD use. The magnitude of perpetrated interpersonal violence appears to vary depending on the type of drug used. Being a victim or perpetrating intimate violence has been attributed to drug use, resulting in poor mental health (27).

Several pre-pandemic reviews have also suggested that socio-demographic conditions make youth more vulnerable to violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health conditions. Being a woman of a certain age or having a certain degree of educational attainment appears to increase the number of episodes of these conditions (28; 29; 30). Dos-Santos et al. (24) noted that less than eight years of education was associated with victimizing psychological, physical, and sexual intimate violence.

The association between forms of violence, AOD use, and mental health symptoms has been described with several populations in different directions considering pre-first-year pandemic data. The focus on victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health symptoms during the second year of the pandemic is essential since such conditions can become worst and more significant during emergencies. It is needed to describe their association and design effective public policies and preventive interventions. Several factors, such as being a victim or a perpetrator, the directionality of the associations, and social determinants (such as sex and educational attainment), could shed light on the role of each factor in these links. Validation of the concepts within a predictive model is also essential every time it is necessary to understand a pandemic (31; 32; 16).

The Structural Equation Model (SEM) through confirmed factor analysis (CFA) with its chi-square and fit indices, is the recommended tool for assessing the validity of relationships between variables (33; 34; 35). The indices of a model with a good fit must be under 0.08 for the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), under 0.06 for the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and over 0.90 for the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI), from the chi-square test of the SEM. Evaluating relationships with a statistically advanced strategy could shed light on the association between violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health symptoms among Mexican youth, making it possible to design cost-effective community policies during emergency situations based on empirical data.

The present study uses a valid path model to describe the association between victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, harmful AOD, and mental health conditions in Mexican youth during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our hypothesis is that victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence are associated with harmful AOD use and mental health symptoms, mediated by age and education demographics. This study explores whether victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence predicts harmful psychoactive substance use (Ha1), depression (Ha2), anxiety (Ha3), and PTSD symptoms (Ha4), with differences between sex and scholarship, in the context of the pandemic. In addition, it explores whether harmful AOD affects the perpetration of interpersonal and intimate violence (Ha5), depression (Ha6), anxiety (Ha7), and PTSD symptomatology (Ha8).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

We surveyed 7,420 young Mexicans with a mean age of 20 (

SD=1.90,

range=18-24), 5,106 (68.80%) of whom were women and 2,314 (31.20%) men. A total of 1,689 (22.80%) had reported completing senior high school while 5,731 (77.20%) had obtained university degrees (the age averages and standard deviations were the same for both educational attainment levels). The distribution of the total sample by comparison variables is shown in

Table 1.

Participants agreed to answer the survey in keeping with the privacy policies established in the General Protection of Personal Information in the Possession of Regulated Entities Act (36). Data were asymmetrically encrypted. The database was held in the official university domain, with security locks to protect the information and guarantee its management in keeping with the subjects’ informed consent.

Regarding informed consent, researchers told participants that data confidentiality would be maintained by calculating general averages. Participants were told that findings would be used for epidemiological research and that they could refuse to comply with data requests and drop out at any point in the study. Although incentives were not offered, immediate feedback was provided in the form of psychoeducational tools (such as infographics, videos, and Moodle ® courses on COVID-19, self-care, relaxation techniques, problem-solving, and socioemotional management skills). Phone numbers were provided to obtain remote psychological care from the Health Ministry and public university services. Finally, the benefits of accessing the platforms or requesting help for dealing with mental health conditions were described. A data section, in which participants could give their phone numbers or emails so they could be contacted, was included to enable them to request remote psychological care. The protocol was approved with the code FPSI/422/CEIP/157/2020 by the Institutional Review Board of the Psychology Faculty Ethics Committee on Applied Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

2.2. Instruments

A web-based application (32; see https://www.misalud.unam.mx) included two dichotomic answer-questions on sex and educational attainment (man-woman; high school or university degree) and five psychological tests.

The Life Events Checklist 5

th Edition (LEC-5; 15; 37) included fourteen selected yes/no dichotomic response items on violence from the Posttraumatic Checklist (PCL-5, A criterion; 38). Four items asked about victimizing interpersonal violence, four about victimizing intimate violence, four about perpetrating interpersonal violence, and two about perpetrating intimate violence, in the previous six months (see

Appendix A]. Each prompt included the origin of the violence (such as

physical assault [… being attacked, hit, slapped, kicked, beaten up]), and the origin of the intimate violence (such as

was this physical abuse inflicted by a family member or your partner?). If subjects checked a violent event, they were asked to select the one that had bothered them most at the time and to answer the questions in part B of the PCL-5 (see below).

The WHO Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) determines harmful use for ten groups of AOD: tobacco (cigarettes, chewing tobacco, cigars), alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, spirits), cannabis (marijuana, pot, grass, hash), cocaine (coke, crack), amphetamine-type stimulants (speed, meth, ecstasy), inhalants (nitrous, glue, petrol, paint, thinner), sedatives or sleeping pills (diazepam, alprazolam, flunitrazepam, midazolam), hallucinogens (LSD, acid, mushrooms, trips, ketamine), opioids (heroin, morphine, methadone, buprenorphine, codeine), and other drugs (39). ASSIST consists of eight questions screening for harmful AOD use including: 1) lifetime use; 2) use in the past three months; 3) having a strong desire to use the drug in question; 4) health, social, legal, or financial problems; 5) failing to do what is expected because of the use of the drug in question; 6) other expressions of concern about the use of the drug in question; 7) attempts to reduce use of the drug in question; and 8) injecting any drug (non-medical use only). The first item has dichotomous options: yes [1] or no [0]. Items two to five have a five-option response: never; once or twice; monthly; weekly; and daily or almost daily. The value of each response option varies from 0, 2, 3, 4, 6 for item two; 0, 3, 4, 5, 6 for item three; 0, 4, 5, 6, 7 for item four, to 0, 5, 6, 7, 8 for item five. Items six to eight have a three-option response: no, never [0]; yes, it happened in the past three months [6]; or yes, but not in the past three months [3]. The score for harmful use of each substance is calculated by adding the answers to questions two to seven. Neither question five on tobacco nor questions one or eight for all substances is used to calculate the score (see

Appendix A). Subjects reporting injecting drugs are referred to specialized emergency care. ASSIST has proved to have good validity and reliability coefficients. Reliability values fluctuated between 0.80 for the alcohol dimension and 0.91 for stimulants (40). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) found a good test factor structure (

[1,583] = 50,863.65,

p<0.001, an

RMSEA = 0.040, an

SRMR = 0.032, a

CFI = 0.920 and a

TLI = 0.913).

The Major-Depressive-Episode (MDE) checklist consists of eleven five-option-response items (38; such as

Do you feel worthless or not good enough? see

Appendix A). The response options involved how often participants had experienced symptoms in the past twelve months: always [1], nearly always [2], sometimes [3], rarely [4], or never [5]. We considered several steps to calculate the total score: part 1, part 2, part 3, and criterion A and B guidelines. The criteria for Part 1 were met when items one and two (

Sadness or depressed mood? and

Discouraged because of how things are going in your life?) were answered with options 1 or 2. The criteria for Part 2 were met when five or more items were answered with options 1 or 2 from items 2 to 10 plus part 1. The criteria for Part 3 were met when question 3 (

Loss of interest or pleasure?) was recorded with response options 1 or 2. Criterion A was met when part 1 and part 2 or 3 were completed. Criterion B was met when question 11 (

Symptoms causing impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning?) was recorded with response options 1, 2, or 3. Finally, an MDE was identified when criteria A and B were met (38). The MDE has good validity and reliability coefficients (41). The α = 0.92 and Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) found a good checklist factor structure (

[32] = 2,643.99,

p<0.001, an

RMSEA = 0.067, an

SRMR = 0.023, a

CFI = 0.975, and a

TLI = 0.965).

The Generalized Anxiety (GA) scale consists of five eleven-option-response items (adapted from Goldberg and collaborators [42]; such as

I have felt nervous or on edge; see

Appendix A). Response options ranged from zero (total absence of symptom) to ten (full presence of symptoms) for whether participants had felt anxious in the past two weeks. We therefore screened for GA by adding the score and dividing it by five. In keeping with the Goldberg et al. (42) study, an average of 60% was considered to have met the criterion for GA. The GA has shown good validity and reliability coefficients (41). The α = 0.94 and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) found a good scale factor structure (

[5] = 350.57,

p<0.001, an

RMSEA = 0.061, an

SRMR = 0.007, an

CFI = 0.996, and a

TLI = 0.992).

The PCL-5 consists of twenty five-option-response items to assess posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 43; 44). Responses ranged from not at all [0], slightly [1], moderately [2], quite a lot [3], to extremely [4] bothersome symptoms in the past month. We used the four-factor structure (38; 44): reexperiencing, with five items (criterion B; such as

repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience?), avoidance, with two items (criterion C; such as

avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience?), negative alterations in cognition and mood (NACM) with seven items (criterion D; such as

Having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world [for example, having thoughts such as I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no-one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous]), and hyperarousal with six items (criterion E; such as

having difficulty concentrating; see

Appendix A). The PCL-5 included the less/more-than-a-month-response for

how long have the symptoms been bothering you? Blevins et al., (44) reported that the four-factor structure was a model with a good fit (

[164] = 558.18,

p<.001, a

CFI = 0.91, a

TLI = 0.89, an

RMSEA = 0.07, and an

SRMR = 0.05; alpha = 0.94), whose optimal score of 31 (out of a total of 80) yielded a sensitivity of 0.77, a specificity of 0.96, an efficiency of 0.93 and a quality of efficiency of 0.73. In addition, the PTSD criterion was considered when a subject selected a 2-response option or more for at least one of the B-items, one of the C-items, two of the D-items, and two of the E-items, and symptoms had been bothering them for over a month. PTSD has shown additional good validity and reliability coefficients (41). The α = 0.96 and Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) found a good checklist factor structure (

[161] = 5,648.34,

p<0.001, an

RMSEA = 0.077, an

SRMR = 0.040, a

CFI = 0.9375, and a

TLI = 0.924).

2.3. Procedure

Participants were invited to enroll in the web-based application between September 1, 2021, and August 31, 2022. The link was available through the Mexican Health Ministry Website (announced on the radio, television, and Internet). Instructions included the following:

The risk of suffering from COVID-19 is an unprecedented social condition that affects us all. The current COVID-19 pandemic is a situation in which we must understand our feelings. We must find out how to deal with them and where to find evidence-based care when required. We therefore invite you to answer the following questionnaire. You will receive feedback on your answers and counseling to help you cope with the emotions, thoughts, and behaviors caused by the current health contingency. Your participation is voluntary, and all the information you provide will be treated confidentially. Your information management will follow Mexican privacy policies for personal data treatment.

2.4. Data Analysis

The statistical procedure involved several analytical steps. We first examined the dimensionality of the LEC-5, ASSIST, MDE, GA, and PCL-5 scales to provide their construct validity evidence for the total sample. We used the CFA from maximum likelihood for continuous variable data and CFA from the diagonally weighted least squares for categorical variables as estimation methods (31; 34). The overall fit of the models was evaluated using the chi-square goodness of fit test. Since the chi-square goodness of fit test is oversensitive to large sample sizes, more emphasis was given to fit indices such as the CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. The SRMR index was not considered for categorical data as Li (34) recommended. Models with CFI and TLI values greater than 0.90 and RMSEA and SRMR values of less than 0.08 and 0.06 were regarded as indicators of good data fit (33; 34; 35). We also obtained a Cronbach´s Alpha test for all scales to determine the reliability of the dimensions.

We obtained the scores for each scale and classified subjects who met the violence (LEC-5), AOD (ASSIST), depression (MDE), anxiety (GA), and PTSD (PCL-5) criteria for risk. We calculated groups for poly drug use (more than one harmful AOD use) and comorbidity (more than one group of mental health symptoms). In other words, we obtained the average scores of the scales, and classified participants into At-Risk or Not-at-Risk groups for each dimension. We performed chi-square tests on participants’ distribution, by groups of risk from violence (victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence, perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence), harmful AOD use, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms, and by sex or educational attainment of the sample.

We calculated the corresponding relative risks (odds ratios), with their respective 95% confidence intervals, for victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence over harmful AOD use, and harmful AOD use over victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence for the total sample. We also calculated the corresponding relative risks, with the respective 95% confidence intervals, for harmful AOD use and victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence scales over mental health symptoms for the total sample.

Finally, several tested structural models of the association directionality from victimizing and perpetrating and interpersonal and intimate violence to harmful AOD use and mental health symptoms were run based on the odds ratio results. We represented the predictive models between variables, evaluating them with a chi-square test and their fit indices through the SEM with a mixture of continuous and categorical variables, for the whole sample (34), and by sex and educational attainment sub-samples. All analyses were conducted using Lavaan 0.6-11 in the integrated development environment RSTUDIO® 2022.02.0 from the R Core Team (45) of the Foundation for Statistical Computing. We also used SPSS ® 25.0 (IBM Corp.; 46).

3. Results

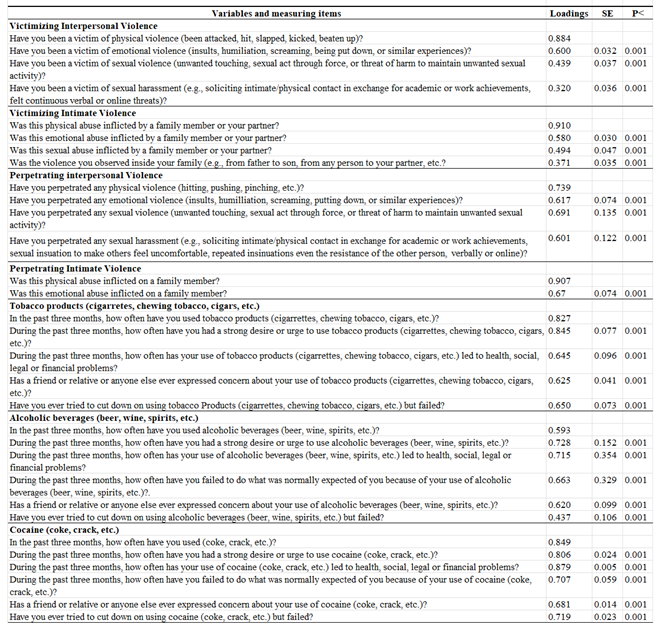

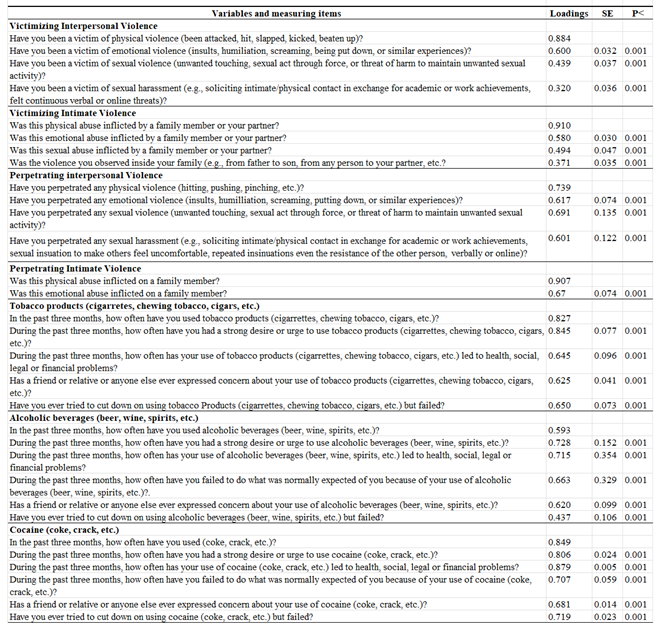

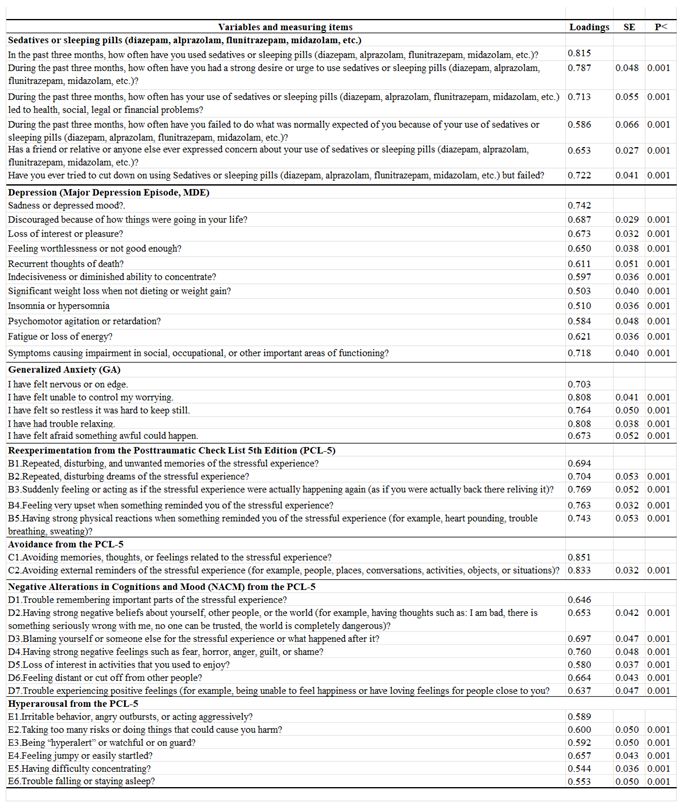

3.1. Confirmatory Factorial Analyses and Cronbach´s Alpha

Results from the factor models of the LEC-5, ASSIST, MDE, GA, and PCL-5 scales are shown in

Table 2. Data fitting was adequate, with

CFIs and

TLIs > 0.90,

RMSEAs < 0.08, and

SRMRs < 0.06. As noted, the categorical CFA indicated a good fit for the four LEC-5 scales: victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, and the ASSIST-Once in Lifetime AOD Use scale. The CFAs also obtained a good fit for the ASSIST, MDE, GA, and PCL-5 continuum variables -Re-experimentation, Avoidance, NACM, and Hyperactivation. The reliability range of the scales went from 0.60 for the Once in Lifetime Drug Use scale to 0.96 for the Opioid scale from ASSIST.

3.2. Violence, Harmful AOD Use, Depression, Anxiety, and PTSD in the Total Sample and by Sex and Educational Attainment

The distribution of youths at risk for violence, harmful AOD use, depression, generalized anxiety, and PTSD symptom criteria in the total sample and by sex and educational attainment are shown in

Table 3. In the overall sample and a

ccording to the cutoff score in the corresponding scales, 25.00% of participants were at-risk for victimizing interpersonal violence, 25.26% for victimizing intimate violence, 23.48% for perpetrating interpersonal violence, and 15.38% for perpetrating intimate violence. In harmful AOD use, 25.90% of participants were at risk for tobacco use, 20.20% were at risk for alcohol use, and 12.50% were at risk for cannabis use. Moreover, 18.93% of the total sample were at risk for several drugs use (poly use), while 44.46% of participants were at-risk for depression, 47.90% for anxiety, and 29.47% for PTSD symptoms. 36.56% of the total sample reported at least two mental health problem (comorbidity).

The percentages of men, women, high school, and university graduates who reported victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health criteria are also shown in

Table 3. Note that the proportions of women at risk for victimizing and perpetrating intimate violence were significantly higher than those of men (p<0.05). The proportion of men at risk for AOD use was significantly higher than that of women (p<0.05), except for sedative use, where women scored higher than men (p<0.05). The proportion of women at risk across mental health conditions was significantly higher than that of men (p<0.05).

There were no significant differences between the proportion of high-school participants at risk for any type of violence and those with university degrees (p<0.05). However, for harmful AOD use, participants who had only completed high school were significantly more at risk for tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and stimulant use than those who had completed university (p<0.05). The proportion of high school participants at risk for depression, PTSD, and comorbidity was significantly higher than that of participants with university degrees (p<0.05).

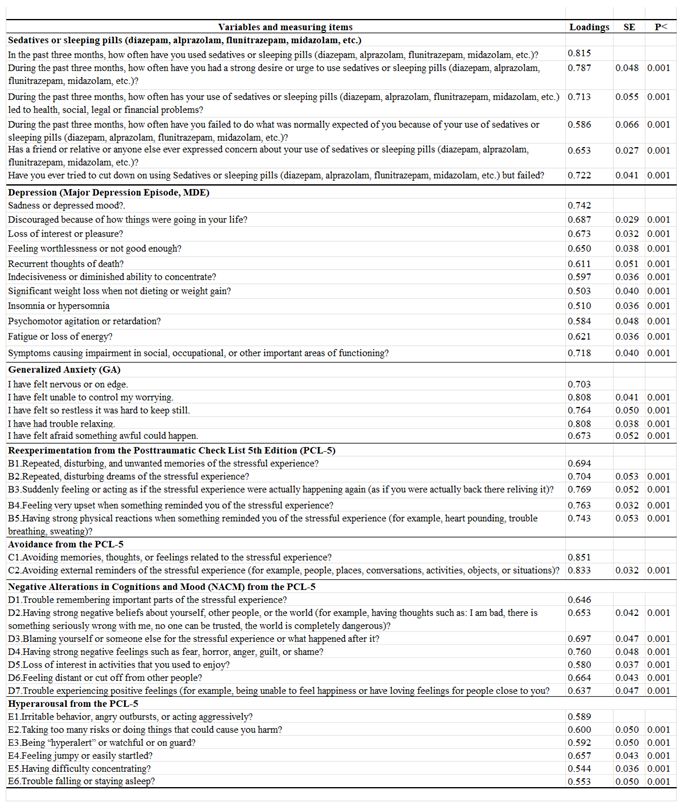

3.3. Relative Risks between Violence, Harmful AOD Use, and Mental Health Symptoms

The significant relative risks, with their respective 95% confidence intervals from the odds ratio analysis, are shown in

Figure 1. V

ictimizing interpersonal and intimate violence predicting harmful AOD use is represented in the upper panel in the left graph in the Figure. Participants who had been victims of interpersonal and intimate violence showed increases in harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, sedatives, hallucinogens, and other drugs (1.353 to 3.153-fold increases).

Victimizing intimate violence alone increased stimulant risk 1.972-fold and poly-use 1.417-fold.

Relative harmful AOD use and victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence risk of perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence are shown in the lower left graph panel of

Figure 1.

Risky use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, stimulants, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, other drugs, and polydrug use increase perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence (between 1.456 and 5.233-fold). Victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence resulted in 4.674-fold and 5.539-fold increases in perpetrating interpersonal violence. Victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence also resulted in 5.512-fold and 6.011-fold increases of perpetrating intimate violence.

Significant relative risks, with their respective 95% confidence intervals, for harmful AOD use and v

ictimizing interpersonal and intimate violence over mental health symptoms are shown in the right graph in

Figure 1. Harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, sedatives, and polydrug increased depression, anxiety, PTSD, and comorbidity (with 1.448 to 4.436-fold-increases). Harmful hallucinogen use predicted depression, anxiety, and comorbidity (with 1.662 to 2.313-fold increases). Harmful use of other drugs predicted depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms (with 1.818 to 3.500-fold increases). Harmful use of cocaine and stimulants also predicted depression and anxiety symptoms (with 1.971 to 3.978-fold increases).

Victimizing intimate violence predicted depression, anxiety, PTSD symptoms, and comorbidity (with 1.632 to 3.099-fold increases), while victimizing interpersonal violence also predicted depression and anxiety symptoms (with 1.707 to 2.401-fold increases).

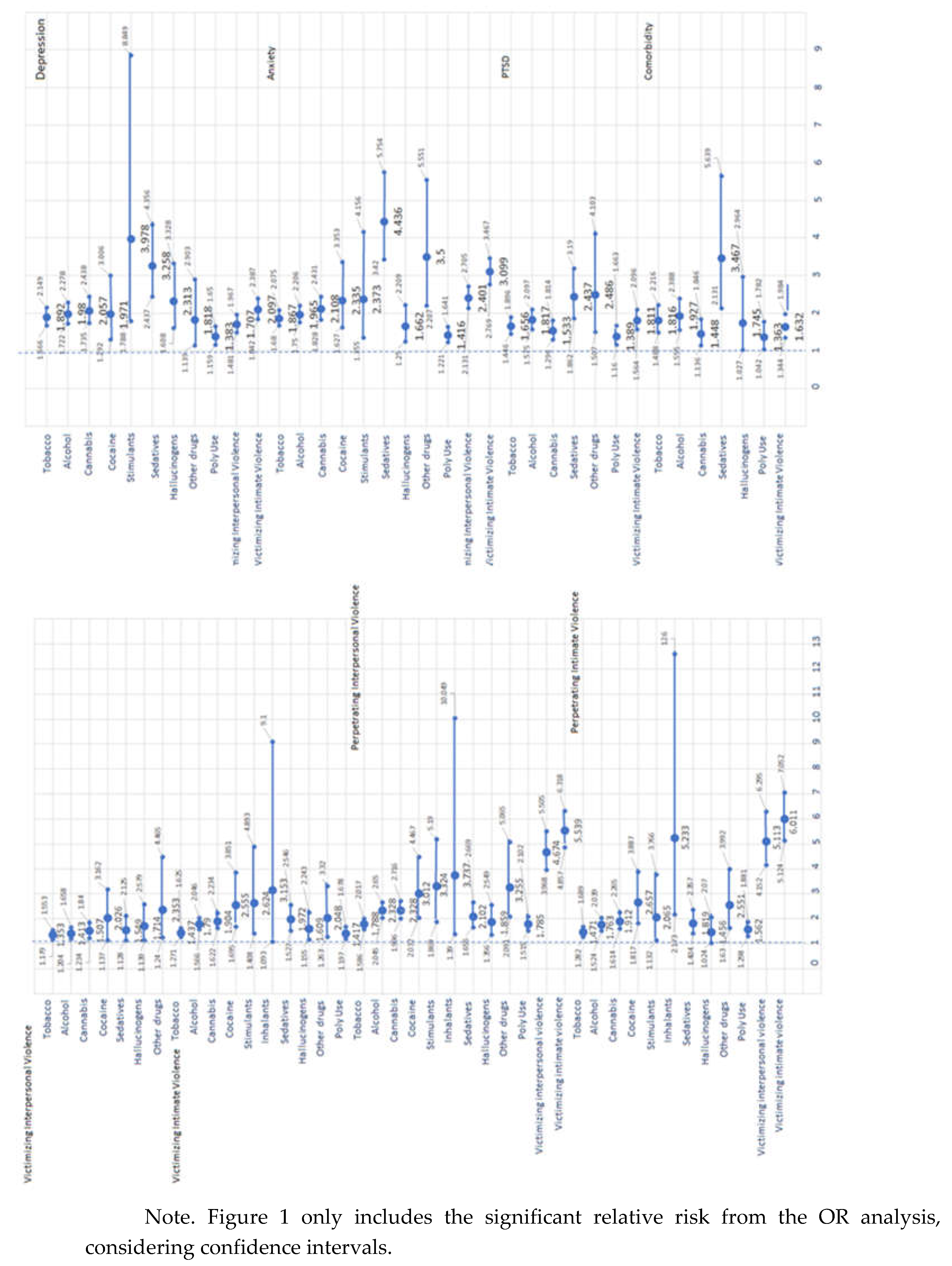

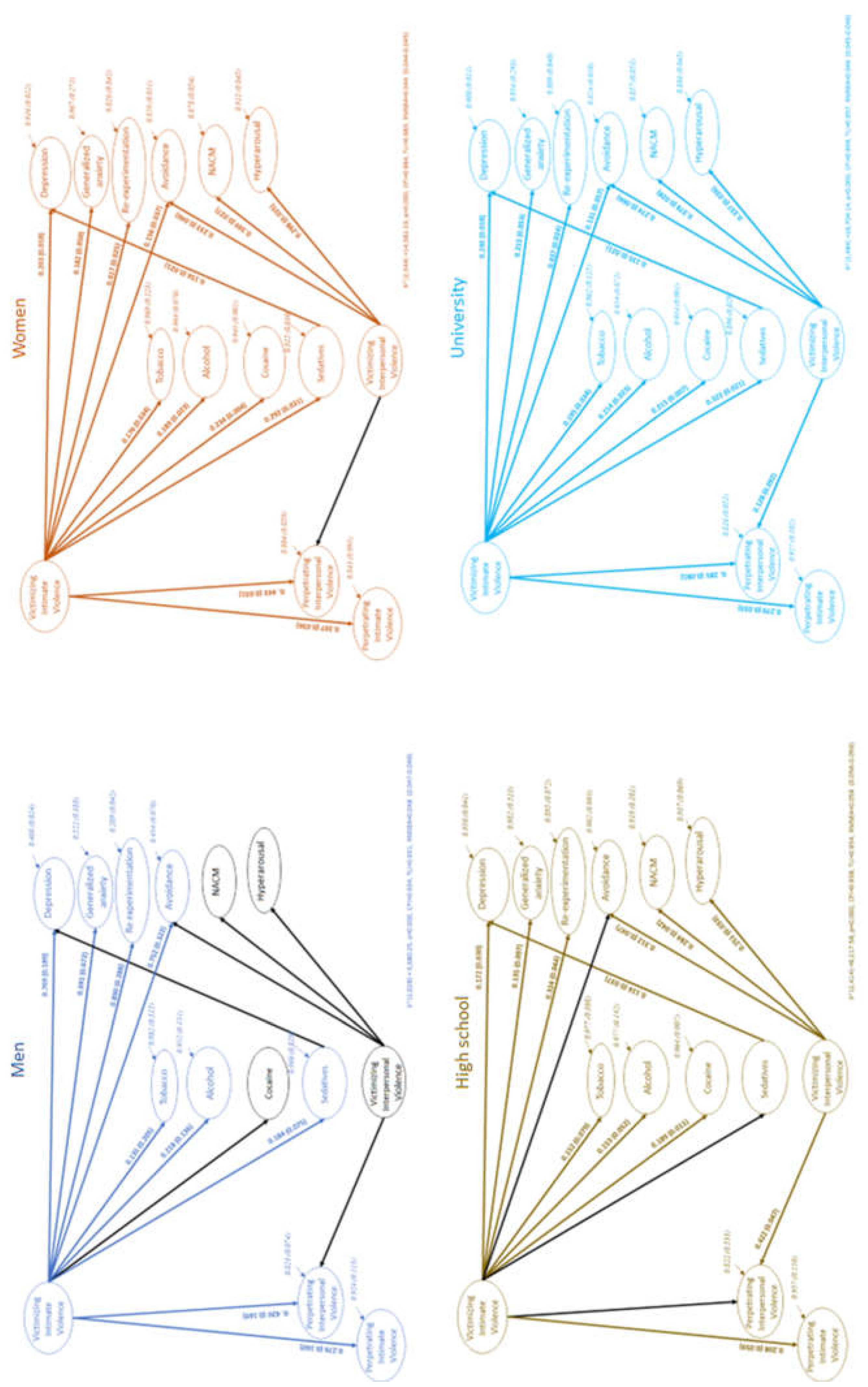

3.4. Structural Equation Modeling

The best restricted model tested after odds ratios is shown in

Figure 2. The final model included paths from victimizing intimate violence to harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, sedatives (b

Tob = 0.190, b

Alc = 0.201, b

Coc = 0.204, and b

Sed = 0.294, respectively), depression, anxiety, re-experimentation, avoidance (b

MDE = 0.233, b

GA = 0.200, b

Rex = 0.422, and b

Avo = 0.140, respectively), and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence (b

PIntPV= 0.204, b

PIntV = 0.390, respectively). The model includes a path between harmful sedative use over depression (b

MDE = 0.133), and victimizing interpersonal violence over avoidance, NACM, hyperarousal, and perpetrating interpersonal violence (b

Avo = 0.242, b

NACM = 0.358, b

Hyp = 0.319, and b

PIntPV = 0.208, respectively). Victimizing intimate violence indirectly affects depression via risky use of sedatives (combined b

Sed,MDE = 0.427). The model provided a good fit with the data from 204 iterations with 276 parameters (

X² [2,484] = 14,941.17,

p<.001). It resulted in a

CFI = 0.968, a

TLI = 0.966, and an

RMSEA = 0.037 [0.037 – 0.038]), using a mixture of continuous and categorical observed variables from the total sample. All path coefficients were significant at p < 0.01 or less.

Appendix A shows factor loadings for the observed variables for each scale of the SEM included in

Figure 2. In all cases, factor loadings were greater than 0.300.

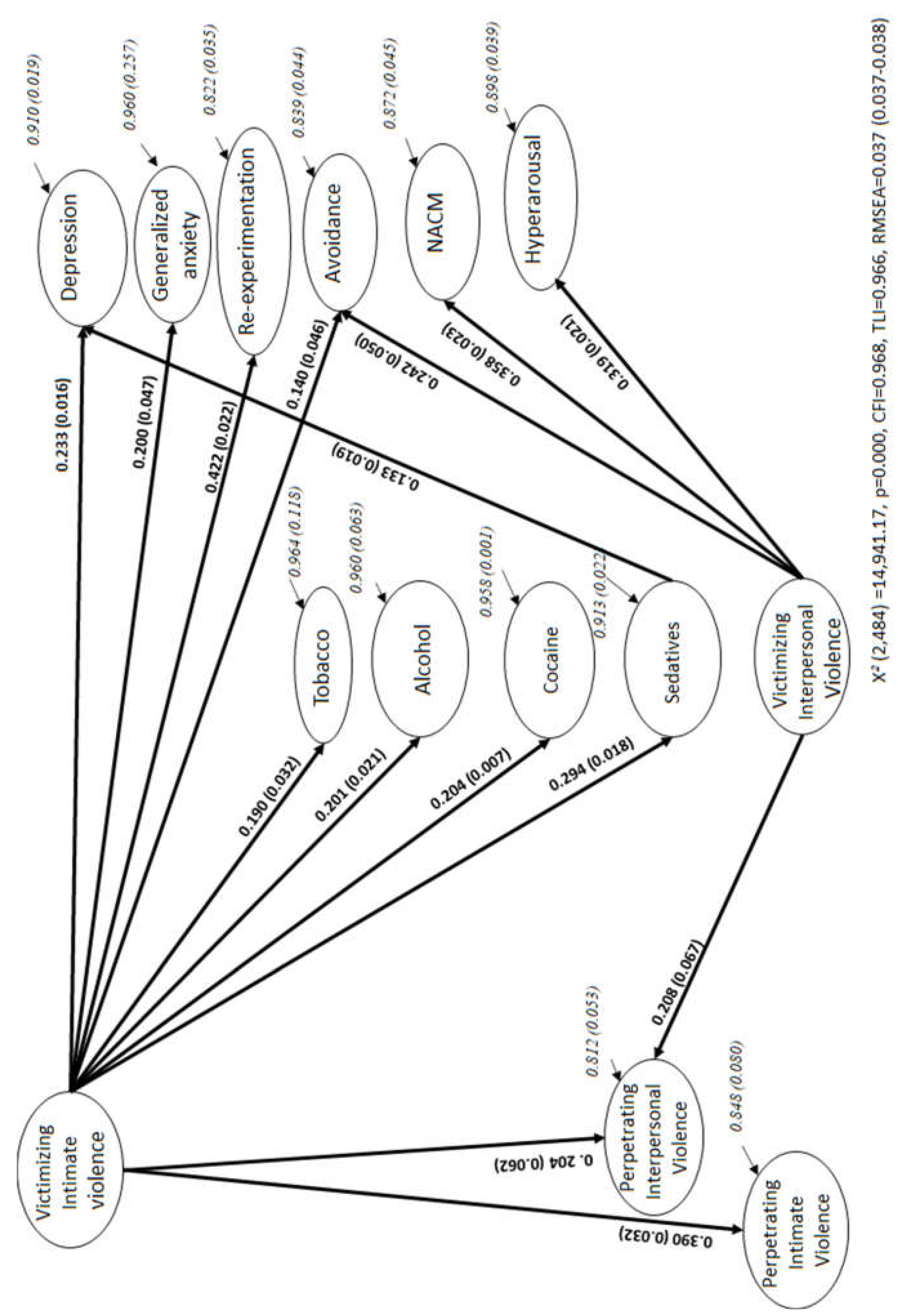

SEMs by sex and educational attainment samples are shown in

Figure 3. Violence scales had to be restricted to obtain models with a good fit. The men´s model has considered emotional and sexual abuse items for victimizing intimate violence and physical, emotional, and sexual items for perpetrating interpersonal violence. The women´s model has included physical, emotional, and sexual abuse items for victimizing interpersonal violence and physical, emotional, and sexual items for perpetrating interpersonal violence. The high school sample´s model includes physical, emotional, and sexual items for victimizing intimate violence.

The men´s model resulted in a robust predictive path between victimizing intimate violence and harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, and sedatives, but not of cocaine. Men´s SEM showed a strong predictive pattern of victimizing intimate violence for depression, anxiety, re-experimentation, and avoidance symptoms, as well as for perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence. The men´s model did not confirm victimizing interpersonal violence as a predictor of avoidance, NACM, or hyperarousal or for perpetrating interpersonal violence. Sedative use did not modulate the prediction of violence for depression either. The Women´s SEM has confirmed the global SEM pattern, except for victimizing interpersonal violence as a predictor of perpetrating interpersonal violence.

Finally, the high-school participants´ path model has confirmed victimizing intimate violence as a predictor of harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, and cocaine, depression, anxiety, re-experimentation symptoms, and perpetrating intimate violence. However, this path did not predict avoidance, or sedatives, or perpetrating interpersonal violence. Harmful sedative use has separately predicted depression symptoms. High-school students´ SEM indicates that victimizing interpersonal violence predicts avoidance, NACM, hyperarousal, and perpetrating interpersonal violence. University students´ SEM replicates all global SEM predictions.

4. Discussion

The present study analyzes the relationship between victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, harmful AOD, and mental health conditions of Mexican youth mediated by sex and education demographics during the second year of the pandemic. The study has validated measurements and models comparing levels of violence, AOD use, depression, anxiety, and PTSD severity during the context of the pandemic. Findings were compared with pre-pandemic and first year of the pandemic prevalence and directionality. Associations between variables have also been identified for the entire Mexican youth sample, and by sex and educational attainment.

Findings suggest a good structure of violence, harmful AOD use, depression, anxiety, and PTSD measurements. SEM has proved to be an effective strategy for validating the path between the study variables and the odds ratio analysis, the standard type of assessment in these kinds of studies. The valid structure of our variables replicates the conceptualizations of Weathers, Litz et al. (43), Scott-Storey et al. (16), Tiburcio et al. (47), Morales, Robles, Bosch et al. (41), Goldberg et al. (42), and Blevins et al. (44). The valid structure of the assessment has been used as an essential practice as recommended by Elhai and Palmieri (31) and Scott-Storey et al. (16) during emergencies.

A valid structure of victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence in the Mexican youth population comprises behaviors involving physical assault, psychological abuse, sexual assault, and any other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experiences while victimizing or perpetrating interpersonal or intimate violence, both inside and outside the home. Study participants reported violent behaviors conceptualized by the WHO (2), Oram et al. (12), Alexander and Johnson (10), Kourti et al. (11), Scott-Storey et al. (16), and Weathers, Litz et al. (37), providing further information on the second year of the pandemic.

The valid assessment of harmful AOD use has also been considered in the WHO definition (2010). Harmful AOD use refers to substances used in the past three months, leading to health, social, legal, and financial problems, failing to do what is expected of one and failing to reduce drug use. Friends and relatives have also expressed concern about the person´s use under this conceptualization. Depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms have been evaluated in accordance with the criteria of the APA (38), Goldberg et al. (42), and Blevins et al. (44).

One in four Mexican participants reported interpersonal or intimate violence in the past six months during the second year of the pandemic. These 2021-2022 rates were higher than what White et al. (9) reported between 2012 - 2020, below what Glowacz et al. (17) reported in 2020, and supporting Kourti et al., (11)´s proposal that intimate violence increased throughout the first year of the pandemic. Our findings also identified perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence during the second year of the pandemic: 23.48% of Mexican youth reported perpetrating interpersonal violence, while 15.38% reported perpetrating intimate abuse. The Mexican community has therefore reported high levels of violence as White et al. (9) detailed when comparing their results with clinical groups. Glowacz et al. (17) have also proposed that younger participants involved in a relationship, like the Mexican youth in the study, were more likely to experience and perpetrate physical and psychological violence during lockdown.

Young Mexican men and women also reported victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal violence. However, more women than men reported suffering and perpetrating intimate violence, partially contrasting with Glowacz et al.´s (17) report that more men than women suffer from physical intimate violence, but supporting Glowacz et al. (17)´s conclusion that more women suffer from psychological intimate violence. The fact that similar proportions of men and women suffered and perpetrated interpersonal violence and that different proportions by gender suffered and perpetrated intimate violence supports the pre-pandemic findings of Scott-Storey et al. (16). They reported that it is possible to observe symmetric violence between the sexes, together with asymmetries related to the forms of intimate violence. Scott-Storey et al. (16) stated that fewer men might asymmetrically report victimizing intimate violence, but that they are used to perceiving it in a context where emotional and sexual abuse happen inside families. Our study suggests that men´s victimizing intimate violence contains emotional and sexual forms of violence, asymmetrically by gender. Violence was asymmetric between the sexes for victimizing and perpetrating intimate violence, but symmetric between the sexes for victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal violence. Moreover, victimizing intimate violence was asymmetric between the sexes since it is exclusively referred to as emotional and sexual violence for men. Findings represent violence between and within sexes for our sample during the second year of the pandemic. Forms of violence were symmetric by educational attainment in the study in 2021-2022.

Mexican youth reporting violence also mentioned harmful AOD use, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology in 2021 and 2022. A total of 25.90% reported harmful tobacco use, 20.20% reported harmful alcohol use, and 18.93% reported using more than two psychoactive substances. This coincides with Craig et al´s (19) pre-pandemic findings that one in five adolescents engaged in regular drug use. Our findings of harmful use of AOD appeared to be below global prevalence based on the only epidemiologic study in Mexico by NCA- MHSAMOS (8) of a 2020 sample. Note, however, that the Mexicans in our study reported harmful use of AOD rather than prevalence. Harmful use means that people require long-term treatment due to their use of AOD. In this context, 12.50% of young people were harmfully using cannabis, 1.80% cocaine, and 4.80% sedatives. The need for long-term treatment was evident in 2021 and 2022. The study has also found more men abusing tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or several drugs than women (29.50%, 24.20%, 15.80%, 2.70%, and 22.69% versus 24.20%, 18.60%, 11.00%, 1.50%, and 17.23%, respectively). More women, however, were abusing sedatives than men (5.40% versus 3.50%, respectively). Findings also indicated that those who had only completed high school abused tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine more than participants with a university degree (29.50%, 22.00%, 14.20%, and 2.80% versus 24.80%, 19.60%, 12.00%, and 1.60%, respectively). Findings suggest symmetrical abuse of sedatives and poly-drug use by educational attainment in 2021-2022.

Rates of mental health problems among Mexican youth were also high during the second year of the pandemic: depression (44.46%), generalized anxiety (47.90%), and PTSD (29.47%). Our proportions were slightly below what Craig and collaborators (19) found with adolescents in 2020, but above what Bourmistrova et al. (6) suggested as consequences: mental health symptoms after recovery from illness. Our study also indicated that 36.56% suffered from comorbid mental health symptoms in 2021 and 2022 and observed asymmetries between sex and educational attainment. More women reported depression, anxiety, PTSD, and comorbid symptoms than men (47.61%, 50.40%, 31.77%, and 39.27% versus 34.51%, 42.30%, 24.42%, and 30.60% respectively). More Mexican youths who had only completed high school also reported depression, PTSD, and comorbid symptoms than participants with a university degree (47.01%, 33.51%, and 40.56% versus 43.71%, 28.28%, and 35.39%, respectively).

The study´s hypothesis also focused on the relationship between violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health illness. The odds ratios have suggested how these conditions were related in 2021 and 2022. Victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence increased harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, and sedative use (1.353 to 3.153 folds), above folds proposed pre-pandemic by Brabete et al. (20), and Machisa and Shamu (21). Victimizing interpersonal violence led to a 1.707 to 2.401-fold increase in depression and anxiety symptoms in Mexican youths – like the odds ratios reported by Craig et al. (19) in 2020 and by White et al. (9) pre-pandemic. Victimizing intimate violence also predicted depression, anxiety, PTSD, and comorbid symptomatology (causing 1.632 to 3.099-fold increases) in 2021 and 2022.

The odds ratios also suggested that harmful AOD use predicted perpetrating intimate violence together with mental health conditions. All types of harmful use of AOD increased the perpetration of both interpersonal and intimate violence 1.456 to 5.233-fold as Glowacz et al. (17), Brabete et al. (20) and Caldentey et al. (22) suggested before and in the first year of the pandemic. The risk of perpetrating violence seemed to vary according to the drug used, as Zhong et al. (26) found in the pre-pandemic era. Odds ratios also suggest that using drugs and victimizing intimate violence have been associated with poor mental health, as Bosch et al. (27) and Brabete et al. (20) suggested before the pandemic. Harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, sedatives, and poly drugs increased depression, anxiety, PTSD, and comorbidity 1.448 to 4.436-fold in the second year of the pandemic. Harmful cocaine and stimulant use increased depression and anxiety 1.971 to 3.978-fold. Harmful use of hallucinogens predicted depression, anxiety, and comorbidity (with 1.662 to 2.313-fold-increases). Harmful use of other drugs predicted depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms (with 1.818 to 3.500-fold increases). Finally, the odds ratio also suggests that victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence resulted in a 4.674 to 6.011-fold increase in perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence.

The odds ratio clearly suggested an association between violence, harmful AOD use, and mental health conditions. The global predictive model was therefore based on the resulting odds ratio. The SEM analysis suggested that victimizing intimate violence has exclusively predicted harmful use of tobacco-alcohol-cocaine-and-sedatives (Ha1), depression (Ha2), generalized anxiety (Ha3), and re-experimentation and avoidance symptomatology -from the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder- (PTSD; Ha4) with our Mexican youth sample in 2021 and 2022. Victimizing intimate violence related to drug use and mental health conditions supports the association described by Brabete et al. (20), Machisa and Shamu (21), Craig et al. (19), Glowacz et al. (17), and White et al. (9) both pre-pandemic and in 2020.

Victimizing interpersonal violence did not predict mental health symptoms in our youth sample - as Craig et al. (19) and White et al. (9) suggested pre-pandemic and in 2020. Harmful AOD use did not predict perpetrating interpersonal or intimate violence (Ho5), anxiety (Ho7), or PTSD symptoms (Ho8) -as suggested by the odds ratio, and Glowacz et al. (17), Brabete et al. (20), and Caldentey et al. (22) reported pre-pandemic and in the first year of the emergency. The model did, however, suggest a predictive path between harmful use of sedatives and depression (Ha6). The use of sedatives seemed to mediate victimizing intimate violence and depression in young Mexicans in 2021 and 2022, supporting the findings of Bosch et al. (27) and Brabete et al. (20) before and in 2020.

The global SEM also notes that victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence predicted perpetrating interpersonal violence, and that victimizing intimate violence predicted perpetrating intimate abuse by Mexican youth during the second year of the pandemic. Both victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence have been reported, not just victimizing intimate abuse as White et al. (9) noted pre-pandemic.

The study suggested asymmetric path models associated with sex and education. Victimizing intimate violence was identified as the main predictor of harmful use of AOD, depression, anxiety, re-experimentation, avoidance, and perpetrating violence in the women´s model -as Biswas (28), Hernandez (29) and Gubi et al. (30) suggested pre-pandemic. Victimizing interpersonal violence only predicted more severe PTSD symptomatology -such as negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal plus avoidance. Both victimizing interpersonal and intimate violence were independent paths for the young women´s sample, representing normal and complex PTSD symptomatology related to each form of violence (48).

The study indicates a dense men´s path solely based on victimizing intimate violence. Victimizing intimate violence strongly predicted harmful tobacco-alcohol-sedatives use, depression, anxiety, re-experimentation, and avoidance – normal PTSD symptoms (48). Victimizing intimate violence also predicted perpetrating intimate violence by young men. Glowacz et al. (17) and Scott- Storey et al. (16) have both suggested asymmetries in violence models based on a person´s sex. Our study suggests a particular role of victimizing intimate violence in men´s model relationships.

The high-school predictive model is split into three paths. Victimizing intimate violence predicted harmful use of tobacco-alcohol-cocaine, depression, anxiety, re-experimentation, and perpetrating intimate violence. Victimizing interpersonal violence predicted avoidance, negative alterations in cognition-mood, hyperarousal, complex PTSD, and perpetrating interpersonal violence. The last pattern indicates that harmful use of sedatives predicts depression symptoms in a high school sample. Hernandez (29), Gubi et al. (30), and Dos-Santos et al. (24) suggested that educational attainment predicted violence based on pre- and pandemic first-year findings, but our study presents single paths associated with forms of violence and sedative use. Mexican young people with university degrees were extensively represented in the global violence-AOD-mental-health predictive model.

The present study examines the association between victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence, harmful AOD use, and the mental health conditions of Mexican youth, mediated by sex and education demographics, in 2021 and 2022. A valid measurement of variables has suggested that Mexican youth reported higher levels of violence than those reported before the pandemic. Harmful AOD use rates were similar to pre-pandemic levels; whereas mental health symptomatology was lower than that reported in 2020 research. The path model with a good fit has also suggested that victimizing intimate violence predicted harmful drug use and perpetrating intimate violence. Both victimizing intimate and interpersonal violence have predicted mental health symptomatology and perpetrating interpersonal abuse. Mexican young people were asymmetrically distributed by gender for victimizing and perpetrating intimate violence, but symmetrically distributed for victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal abuse. Forms of victimizing intimate violence by sex were asymmetrically observed by sex due to men´s reports of emotional and sexual abuse. A strong path of victimizing intimate violence following drug use, mental health symptomatology, and perpetrating violence was observed for men. There were two patterns of violence for women -one linked to victimizing intimate violence, predicting drug use, mental health symptoms, and perpetrating violence, and another for victimizing interpersonal violence predicting severe PTSD symptomatology. Young people who had only completed high school showed three predictive patterns -one for victimizing intimate violence, another for victimizing interpersonal violence and yet another for harmful sedative use. Young people with a university degree resulted in a broad model with all the patterns interacting as they do in the global predictive model.

The global comprehensive and associative models of the study have helped describe violence, drug use, and mental health relationships, laying the groundwork for future research on the mechanisms underlying predictive patterns. Explaining these mechanisms could help to design more cost-effective preventive programs and public policies and suggest how to cope with mental health conditions during emergencies in the community context. The Mexican government could design strategies to prevent young people from experiencing interpersonal and intimate violence, preventing harmful AOD use, and mental health issues.

5. Conclusions

The present study analyzed the relationships between violence, harmful drug use, and mental health conditions in Mexican youth, including social determinants such as sex and academic achievement during the second year of the pandemic (2021-2022). Young Mexicans suffered from intimate violence, perpetrated it, harmfully used AOD, and presented mental health symptomatology. The levels of interpersonal and intimate violence were above those reported in other studies before and during the first year of the pandemic. The study widely described victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence. Findings suggested asymmetric victimizing and perpetrating intimate violence, and symmetric victimizing and perpetrating interpersonal abuse between sex. Symmetries were observed in all forms of violence between young people by academic achievement.

AOD use was reported in the pre-pandemic period, but this study found high proportions of multiple use of harmful drugs in 2021 and 2022. More young men were harmfully using drugs, except for sedatives, for which women were at a higher risk. More young people who had completed high school harmfully use tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and stimulants than those with university degrees. Mental health symptoms were below those reported during the first pandemic wave in 2020, but above those cited as sequels of COVID-19. There were asymmetries in depression, anxiety, and PTSD between gender -which affected women more than men- and in depression, anxiety, and comorbidity between educational attainment levels – which were more prevalent in those who had only completed high school than in those who had completed university degrees.

The proportion of young people suffering or perpetrating violence, using AOD, and having mental health problems can be explained by conditions during the pandemic. Glowacz et al. (17) and Kourti et al. (11) have suggested that lockdown or losses during the pandemic could explain these circumstances. Future research, however, could address how sociodemographic settings related to the pandemic, such as social distance, loss of loved ones, losing jobs, etc., were related to violence, drug use, and mental health illness in the second year of the pandemic. Meanwhile, validating the structure of the variables laid the groundwork for path analysis and the proposals for future research. Describing the directionality of the variable´s links could contribute to future research and prevent certain conditions in future pandemics.

Predictive models have indicated that being a victim of intimate violence predicted harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and sedatives, depression, generalized anxiety, re-experimentation, avoidance, and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence. Being a victim of interpersonal violence also resulted in severe PTSD symptoms such as avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal signs. Harmful sedative use also predicted depression. Harmful drug use, however, did not predict perpetrating interpersonal, intimate violence, anxiety, or PTSD symptoms in Mexican youth during the second year of the pandemic.

One hypothesis about the complexity of PTSD is related to forms of violence. Keely et al., (48) have suggested that complex PTSD can be described as pervasive problems with affect regulation (NACM), persistent beliefs about oneself as diminished (succumbing to adverse circumstances), persistent difficulties in sustaining relationships (feeling close to others), and disturbances causing significantly impaired functioning. These severe symptoms were reported by Mexican youth when they experienced interpersonal violence rather than intimate abuse. Victimizing intimate violence were related to normal PTSD symptoms in addition to depression, anxiety, and drug use -as a possible means of coping. Future longitudinal research could analyze complex PTSD related to forms of violence. It is essential, however, to study this relationship in a context where coping skills could help stop the progression of acute stress symptoms to complex PTSD.

In the path model, harmful sedative use mediated victimizing intimate violence and depression, whereas harmful drug use did not predict perpetrating interpersonal or intimate violence. Thus, another hypothesis concerns the role of drug use as a self-medication mechanism. Future longitudinal research could determine whether the use of tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and sedatives is a coping mechanism to numb feelings related to violence or to avoid thinking about experiencing violence. Findings also suggest that being a victim of interpersonal and intimate violence resulted in perpetrating interpersonal and intimate abuse. Additional research should confirm whether a violence-escalating mechanism may occur once young people have been interpersonally or intimately victimized (16).

Findings also indicated asymmetric predictive models between sex and educational attainment levels. Men have reported intimate violence -both emotional and sexual- closely linked to harmful use of tobacco, alcohol, sedatives, depression, anxiety, normal PTSD symptoms-re-experimentation and avoidance, and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence. Women have reported the same victimizing intimate violence path, which also includes physical abuse, harmful cocaine use and the mediating role of sedatives with depression. The women´s model also included the victimizing, interpersonal violence path associated with the symptomatology linked to complex PTSD reported by Keeley et al. (48).

Scott-Storey and collaborators (16) have already proposed that asymmetries in victimizing intimate violence by sex may result from differences in the perception of violence by sex in a context of social inequities, and normalized violation of human rights (49). Both men and women suffer intimate violence. However, forms of violence and their consequences may differ by sex due to the patriarchal culture and the role of power and control in societies. Although men disclose the forms of violence suffered, they seem to view emotional and sexual abuse as more dangerous than physical violence. Women can endure several forms of violence for long periods of time, suffering greater consequences (49). Men and women, however, seem to cope with victimizing intimate violence through AOD use (50). Future longitudinal research should therefore address forms of violence, gender interaction, and the consequences of perceived abuse, by sex and culture in several low-income countries where human rights are routinely violated.

Three separate paths characterized the high school youth model. One involves victimizing intimate violence, another involves victimizing interpersonal violence, and yet another involves sedative use predicting depression. Findings also constitute a baseline to explore the hypothesis of the mechanisms behind these paths. Hernandez (29), Gubi et al. (30), and Dos-Santos et al. (24) suggest that lower educational attainment predicts violence, while Craig et al. (19) have reported that the age of onset of drug use is lower in adolescents with lower educational attainment. However, the mechanisms in the paths of the model for participants with lower educational attainment could be addressed in future longitudinal studies.

Participants in this study may be too young to show that drug use predicts the perpetration of violence as Ismayilova (51) has reported with a sample of older participants. The association between drug use and perpetrating interpersonal and intimate violence may be linked to being older, several life conditions, being a caregiver, having lower educational attainment, or experiencing certain socioeconomic conditions. Future research could explore these conditions that could explain the associations between AOD use and violence perpetrated as Islam et al. (52) have proposed.

Findings, meanwhile, underscored the importance of preventing intimate violence as part of public health approaches to prevent harmful drug use and mental health conditions. Early interventions can provide care for both victims and perpetrators and halt the escalation and installation of more severe interpersonal and intimate violence. The conclusions also point to the importance of examining the role of unequal gender roles, social determiners, and drug use as a mechanism for coping with violence and mental health symptoms.

It is essential for first responders and healthcare providers to provide knowledge on mechanisms to reduce violence, drug use and mental health problems. Interpersonal and intimate violence will continue if information on the importance of changing gender norms, roles, and attitudes that perpetuate abuse is not provided. Health care providers must offer timely, coordinated services to tackle violence, substance use, and mental illness. Public policies should provide programs to reduce gender inequities, increase community empowerment, and promote justice and human rights.

6. Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study. Despite the use of advanced statistical analysis such as the SEM, which is extremely reliable, the association between violence, drug use and mental health conditions should be explored through longitudinal studies. Longitudinal studies contribute to confirming and understanding the mechanisms underlying the effects of intimate violence, substance dependence, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptom development.

Findings should also be considered in the context of screening. This means that, although measures of variables were validated, our strategy does not constitute a diagnosis of mental health or substance use disorders. Screening at the community level over-estimates symptoms and reports (42). Future studies should evaluate the consistency between screening and diagnosis, including the sensitivity and specificity of psychometric tools to empirically confirm the proposed model.

Moreover, subsequent research should consider verifying the processes that explain how social determinants are related to our model, such as family size, family interaction, lockdown, and the physical illness of caregivers during a health emergency. Moreover, future studies should identify biased sources from the items as Morales, Robles, Bosch et al. (41) have already reported between sex and educational attainment to increase the accuracy of the comparisons.

Finally, future studies should consider improving the representativeness of the Mexican youth sample because participants in the current study voluntarily chose to participate. This would contribute to improving the design of practical, effective preventive measures and interventions in Mexico.

Author Contributions

SMC, GB, and RB contributed to the conceptualization, writing and data analysis. All authors contributed to the data analysis review, discussion, and data interpretation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We thank the University for the support from the DGAPA-IV300121 and PASPA 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies involving human subjects were reviewed and approved with the code FPSI/422/CEIP/157/2020 by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The subjects provided their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries should be sent to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Factor loadings, standard errors (SE) and p value (P) for observed variables for each SEM variable

References

- World Health Organization (2022). Mental health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic´s impact. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1.

- World Health Organization (2023). Intimate partner violence. https://apps.who.int/violence-info/intimate-partner-violence.

- Pan American Health Organization (2020. Burden of Non-fatal Interpersonal Violence: trends over time. https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/burden-other-forms-interpersonal-violence.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2022) World Drug Report 2022. https://www.unodc.org/res/wdr2022/MS/World_Drug_Report_2022_Exsum_and_Policy_implications_Spanish.pdf.

- Layman, H. M., Thorisdottir, I. E., Halldorsdottir, T., Sigfusdottir, I. D., Allegrante, J. P., & Kristjansson, A. L. (2022). Substance use among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24, 307-324. [CrossRef]

- Bourmistrova, N. W., Solomon, T., Braude, P., Strawbridge, R., & Carter, B. (2022). Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 118-125. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (2021). Violencia contra las mujeres en México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/tablerosestadisticos/vcmm/.

- National Committee on Addictions (2021). Mental Health, and Substance Abuse Observer System. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/648021/INFORME_PAIS_2021.pdf.

- White, S. J., Sin, J., Sweeny, A., Salisbury, T., Wahlich, C., Montesinos, G. C. M., Gillard, S., Brett, E., Alwright, L., Iqbal, N., Khan, A., Perot, C., Marks, J., & Mantovani, N. (2023). Global prevalence and mental health outcomes of intimate partner violence among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E. F., & Johnson, M. D. (2023). On categorizing intimate partner violence: A systematic review of exploratory clustering and classification studies. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T. N., & Tsitsika, A. (2023). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(2). 719-745. [CrossRef]

- Oram, S., Fisher, H. L., Minnis, H. Seedat, S., Walby, S., Hegarty, K. Rouf, K., Angénieux, C. Callard, F., Chandra, P. S., Fazel, S., Garcia-Moreno, C., Handerson, M., Howarth, E., MacMillan, H. L., Murray, L. K., Othman, S., Robotham, D., Rondon, M. B., Sweeny, A., Taggart, D., & Howard, L.M. (2022). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on intimate partner violence and mental health: Advancing mental health services, research, and policy. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(6), 487-524. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. P. (2008). A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Northeastern University Press.

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A., & Stuart, G. L. (1994). Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 476-497. /: https.

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC.5)-Standard. [Measurement instrument]. https://vdocuments.net/life-events-checklist-for-dsm-5-lec-5.html?page=1. /.

- Scott-Storey, K., O´Donnell, S., Ford-Gilboe, M., Varcoe, C., Wachen, N., Malcolm, J., & Vincent, C. (2023). What about the men? A critical review of men´s experiences of intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 858-872. [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, F., Dziewa, A., & Schmits, E. (2022). Intimate partner violence and mental health during lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health, 19, 2535. [CrossRef]

- Mellos, E., & Paparrogopoulos, T. (2022). Substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: What is really happening? Psychiatriki, 33, 17-20. [CrossRef]

- Craig, S. G., Ames, M. E., Bondi, B. C., & Pepler, D. J. (2023). Canadian adolescents´ mental health and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with COVID-19 stressors. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 55(1), 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Brabete, A. C., Greaves, L., Wolfson, L., Stinson, J., Allen, S., & Poole, N. (2020). Substance use (SU) among women in the context of the corollary pandemics of COVID-19 and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Vancouver, B.C. Centre of Excellence for Women´s Health. https://covid19mentalhealthresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/GREAVES_CMH-KS-final-report-2020-11-23.pdf. /.

- Machisa, M., & Shamu, S. (2018). Mental ill health and factors associated with men´s use of intimate partner violence in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health, 18, 376-376. [CrossRef]

- Caldentey, C., Tirado-Muñoz, J., Ferrer, T., Fonseca-Casals, F., Rossi, P., Mestre-Pintó, J. I., & Torrens-Melich, M. (2017). Intimate partner violence among female drug users admitted to the general hospital: Screening and prevalence. Adicciones, 29(3), 172-179. [CrossRef]

- Low, S., Tiberio, S. S., Shortt, J. W., Capaldi, D. M., & Eddy, J. M. (2017). Associations of couples´ intimate partner violence in young adulthood and substance use: A dyadic approach. Psyhcology of Violence, 7(1), 120-127. [CrossRef]

- Dos-Santos, I.B., Costa-Leite, F. M., Costa-Amorim, M. H., Ambrosio-Maciel, P. M., & Gigante, D. P. (2020). Violence against women in life: Study among primary care users. Ciencia & Saude Colectiva, 25(5), 1935-1946. [CrossRef]

- Barchi, F., Winter, S., Dougherty, D. & Ramaphane, P. (2018). Intimate partner violence against women in Northwestern Botswana: The maun women´s Study. Violence Against Women, 24(16), 1909-1927. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S., Yu, R., & Fazel, S. (2020). Drug use disorders and violence: Associations with individual drug categories. Epidemiologic Reviews, 42. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J., Weaver, T. L., Arnold, L. D., & Clark, E. M. (2017). The impact of intimate partner violence on women´s physical health: Findings from the Missouri behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(22), 3402-3419. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, C.S. (2017). Spousal violence against working women in India. Journal of Family Violence, 32(1), 55-67.

- Hernández, W. (2018). Violence with femicide risk: Its effects on women and their children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11-12), 886260518815133. [CrossRef]

- Gubi, D., Nansubuga, E., & Wandera, S. O. (2020). Correlates of intimate partner violence among married women in Uganda: A cross-sectional survey. BMD Public Health, 20(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D., & Palmieri, P. A. (2011). The factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: A literature update, critique of methodology, and agenda for future research. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 849-854. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Chainé, S., Robles, G. R., López, M. A., Bosch, M. A., Beristain, A. A. G., Treviño, S. C. C. L., Palafox, P. G., Lira, C. I. A., Barragan, T. L., & Rangel, G. M. G. (2022). Screening tool for mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: Psychometrics and associations with sex, grieving, contagion, and seeking psychological care. Frontiers in Psychology, 13:882573. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Sage Publications.

- Li, Ch. (2021). Statistical estimation of structural equation models with a mixture of continuous and categorical observed variables. Behavior Research Methods, 53:2191-2213. [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 380-392). Guilford Press.

- General Protection of Personal Information in Possession of Obligated Parties Act, of January 26, 2017 (DOF 26-01-2017). http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGPDPPSO.pdf. 26 January.

- Weathers, F.W., Litz, B.T., Keane, T. m., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013a). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) – LEC-5 and extended criterion A [Measurement instrument]. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_criterionA_form.PDF.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- World Health Organization (2010). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test: Manual for use in primary care. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2.

- Morales-Chainé, S., Robles-García, R., Barragán-Torres, L., & Treviño, S. C. C. L. (2022). Remote screening for alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement by sex, age, lockdown condition, and psychological care-seeking in the primary care setting during the COVID-19 pandemic in México. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Chainé, S., Robles, G. R., Bosch, M. A., & Treviño, S. C. C. L. (2022). Depressive, anxious, and Post-Traumatic Stress symptoms related to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, by sex, COVID-19 status, and interventions-seeking conditions among the general population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19 (19). 12559. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Chainé, S., Robles, G. R., Bosch, M. A., & Treviño, S. C. C. L. (2022). Depressive, anxious, and Post-Traumatic Stress symptoms related to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, by sex, COVID-19 status, and interventions-seeking conditions among the general population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19 (19). 12559. [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W., Litz, B.T., Keane, T. m., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013b). The PTSD CheckList for DSM-5 (PCL-5)-Standard. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.PDF.

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489-498. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org.

- IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp.

- Tiburcio, S. M., Rosete-Mohedano, G., Natera, R. G., Martínez, V. N. A., Carreño, G. S., & Pérez, C. D. (2016). Validez y confiabilidad de la prueba de detección de consumo de alcohol, tabaco y sustancias (ASSIST) en estudiantes universitarios. Adicciones, 28(1), 19-27.

- Keeley, J. W., Reed, G. M., Roberts, M. C., Evans, S. C., Robles, R., Matsumoto, C., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Perkonigg, A., Rousseau, C., Gureje, O., Lovell, A. M., Sharan, P., & Maercker, A. (2016). Disorders specifically associated with stress: A case-controlled field study for ICD-11 mental and behavioural disorders. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16, 109-127. [CrossRef]

- Boreham, M., Marlow, S., & Gilchrist, G. (2019). ´That warm feeling that [alcohol] gave me was what I interpreted love would feel like´ Lived experience of excessive alcohol use and care proceeding by mothers in the family justice system in the UK. Addictive Behaviors, 92, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Barbero, B., López-Pereira, P., Barrio, G., & Vives-Cases, C. (2018). Intimate partner violence against young women: Prevalence and associated factors in Europe. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(7), 611-616. [CrossRef]

- Ismayilova, L. (2015). Spousal violence in 5 transitional countries: A population-based multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), e12-e22. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. J., Mazerolle, P., Broidy, L. & Baird, K. (2021). Exploring the prevalence and correlates associated with intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1-2), 663-690. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).