Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is an increasing challenge to public health with far-reaching implications. The concept of Vaccine hesitancy is used to refer to delay, indecisiveness or refusal to take in vaccines (despite the availability of vaccine) to prevent or combat disease or infection (Anakpo & Mishi, 2022; Coorper, van Rooyen, & Wiysonge, 2021; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020; and MacDonald, 2015). Increasing vaccine intake is important pathway for achieving herd immunity for public safety (Annas & Zamri-Saad, 2021). According to Chevallier, Hacquin and Mercier (2021), the proportion of the population that need to take vaccine in order to reach herd immunity ranges from 75 to 90% (depending on factors such as the basic reproduction number, vaccine-induced immunity duration, and whether vaccines prevent transmission). Although vaccine hesitancy has existed among a small percentage of the population for centuries (Pandolfi et al. 2018), its negative effects have become more pronounced than previously during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mylan and Hardman, 2021), and it is regarded as one of the most serious threats to global health and the economy at large (Robinson, Jones, and Daly 2020). This raises two important thought-provoking questions; first, what determines one’s decision to be vaccinated; second, what is the implication on economic recovery if herd immunity is not chieved due to high level of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy?

Past and present studies identified key determinants of vaccine hesitancy and underscore that vaccine hesitancy is a complex and often context-specific phenomenon that varies across time and place, and vaccines can be influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience, needle phobia, or a lack of understanding about how vaccines work (Benoit and Mauldin, 202; Roberts, Bohler-Muller, and Struwig, 2021). Additionally, structural factors such as health inequalities, socio-economic disadvantages, systemic racism, and barriers to access are major contributors to vaccine scepticism and low uptake (Mylan and Hardman, 2021; Razai, Osama, McKechnie, & Majeed 2021; MacDonald, 2015; Larson, Jarrett, Eckersberger, Smith, & Paterson, 2014). Dubé and MacDonald (2022) documented that non-vaccine related factors that influence individual’s decision to be vaccinated may vary from one location to another, and that contextualization is important precursor and feedback for tailored vaccination programmes.

Furthermore, vaccination hesitancy has implications for economic recovery. Returning to some normalcy and recovery of economies is dependent on the success of measures such as vaccination. Even though vaccine coverage is steadily increasing across the country, the virus remains a threat. Vaccination uptake has implications for business, so the economy can fully open without repercussions, allowing people to freely move and conduct their daily activities, which is critical for business recovery. There is a dearth of literature focusing on the implications of vaccine hesitancy on economic recovery especially in South Africa where vaccine hesitancy is astronomically high with dare impact impacts on the economy. The purpose of this study is therefore to identify the factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and implications for economic recovery.

Methods

The empirical data from this analysis was drawn from the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality. In 2019, the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality was comprised of 375 000 households, and when using Raosoft

1 sample calculation, a minimum of 400 respondents across Gqeberha, Kariega and Despatch are considered representative. The survey was designed and administered in these three regions of the Bay to ensure representation and to consider other demographics such as population groups, age, and gender. The composition of the households by population group consists of 62.9 per cent, which is ascribed to the African population group. The Coloured population group had a total composition of 19.6 per cent (ranking second), the White population group had a total composition of 16.2 per cent of the total households, and the smallest population group by households is the Asian population group, with only 1.3 per cent in 2019. A convenience sampling technique was employed, and those who were available and willing to respond to the questionnaire participated. The survey was designed and tested and covered a set of questions on four main areas: (1) socioeconomic characteristics, (2) sources of information and contextual influence, (3) individual and group influence, and (4) questions related to the vaccine or vaccination. Questions on these areas help elicit facts on major drivers of willingness to be vaccinated which guides a vaccination action plan to increase vaccine intake.

The second part on the implications on the economy recovery given the updated/new preferences among individuals and groups of people, was approached in two steps. The first was to establish the economic (business, job, and cost) and public health consequences of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy. This was achieved through a deduction process from the incidence of vaccine hesitancy and how hesitancy influences the behaviour of individuals.

Results and Discussion

Univariate analysis was done to describe the socio-demographic and other variables of interest such as COVID-19 and other vaccines hesitancy questions. Questions such as general information regarding accepting vaccines when recommended by a health care worker, beliefs on whether there are any better solutions/treatments other than COVID-19 vaccine, their perception on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, whether the government should make COVID-19 compulsory, their trust in government, the role of health care workers, their experience with COVID-19 vaccine, and informational needs about the vaccine.

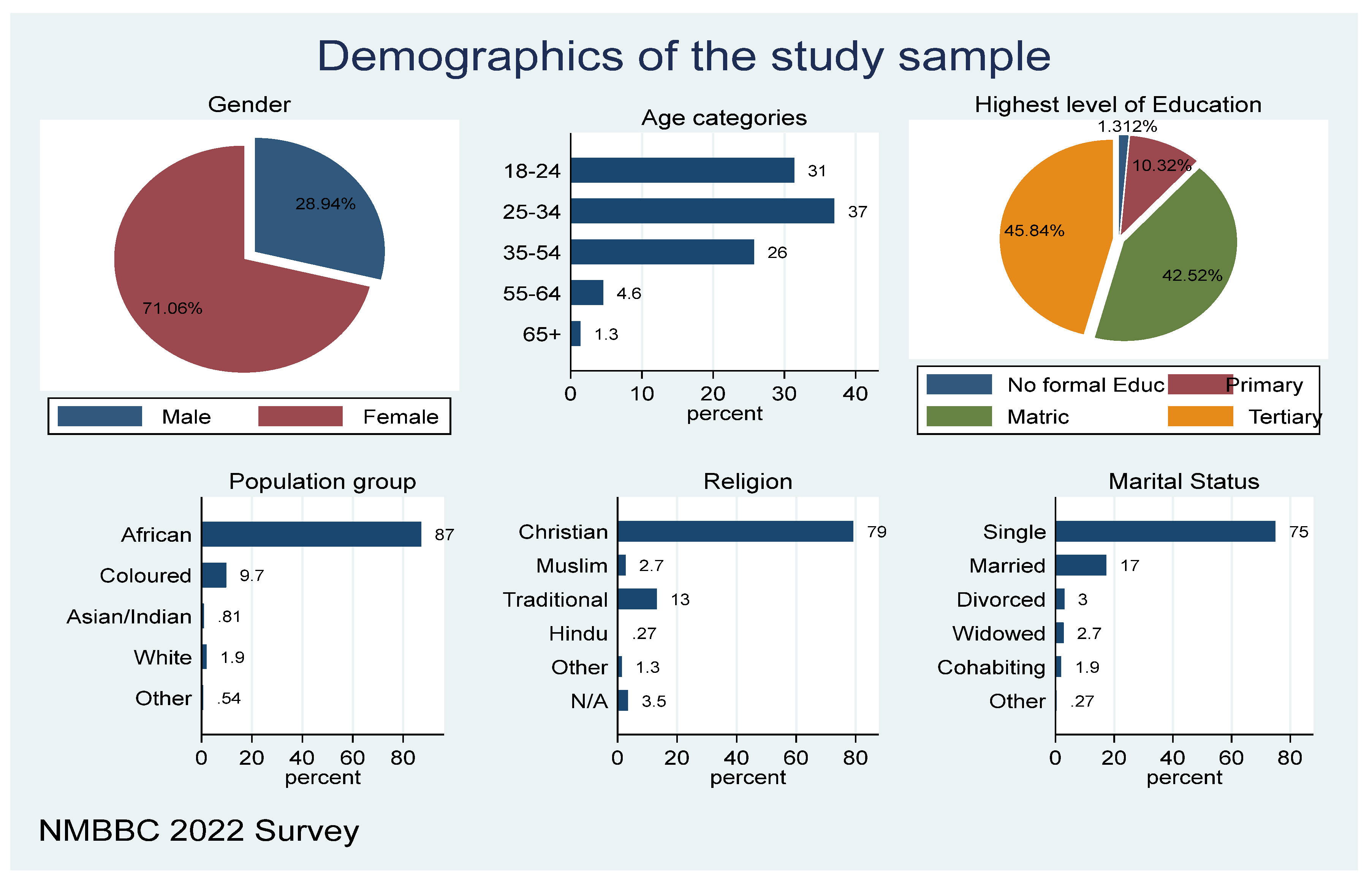

Figure 1 below shows the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants. The figure shows that out of the total sample population that was involved in the study, about 28.94 per cent of the study participants were males, and 71.06 per cent were females. The majority of the respondents were in the age group between 25 -34 years (37%), followed by 18-24 years (31%), 35-54 years (26%) and the lower groups of 55-64 years and 65+ years were 4.6 per cent and 1.3 per cent respectively. Concerning education, most of the respondents have tertiary education and matric, representing 45.84 per cent and 42.52 per cent respectively, while 10.32 per cent responded to having primary education, and a small number (1.3%) had no education. The majority, 75 per cent of the study, reported that they were single with 17 per cent being married, and a few being divorced, windowed, and/or cohabiting. Most of the respondents reported that they belong to the Christian religion (79%), and very few belong to other religious groups. In terms of representation of ethnic groups, about 87 per cent of the participants reported that they are Africans, few were coloured, Asian/Indian, and White.

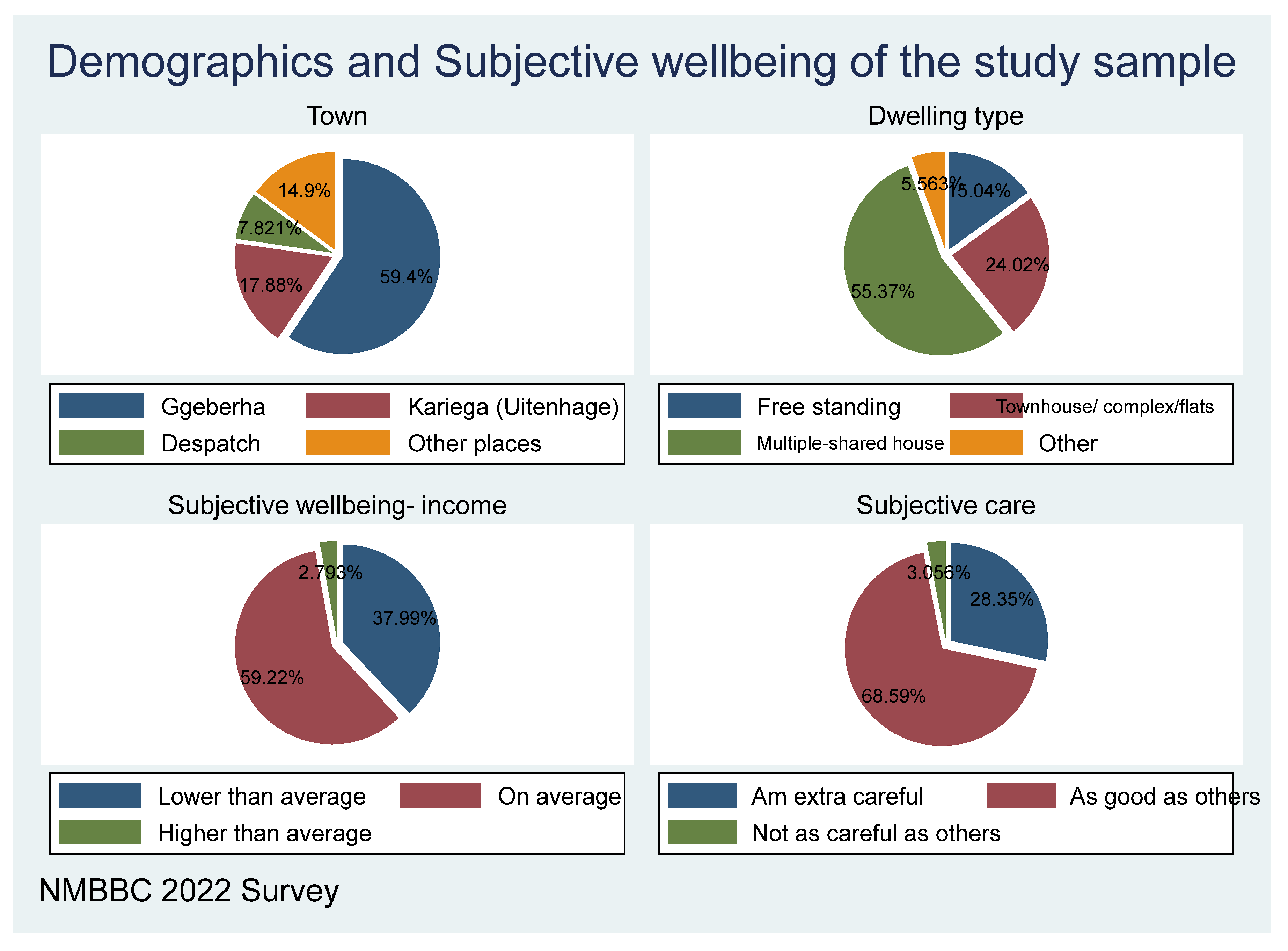

Figure 2 shows that most of the respondents are based in Gqeberha (59.4%), followed by Kariega (17.88%), and a few from Despatch and other places. The socio-economic status of the respondents was primarily from households whose incomes are on average. The average income means same as income of most households, less than average means less than income of most households and above means over income of most households. Therefore, the results show that 59.22% of households have average income, followed by 37.99 per cent whose income is lower than the average, and very few are above average household income

. Regarding the subjective care characteristics, respondents show that 68.59 per cent responded that they are as careful and responsible as others, while 28.35 per cent responded that they are extra-careful, and very few people said they are not careful.

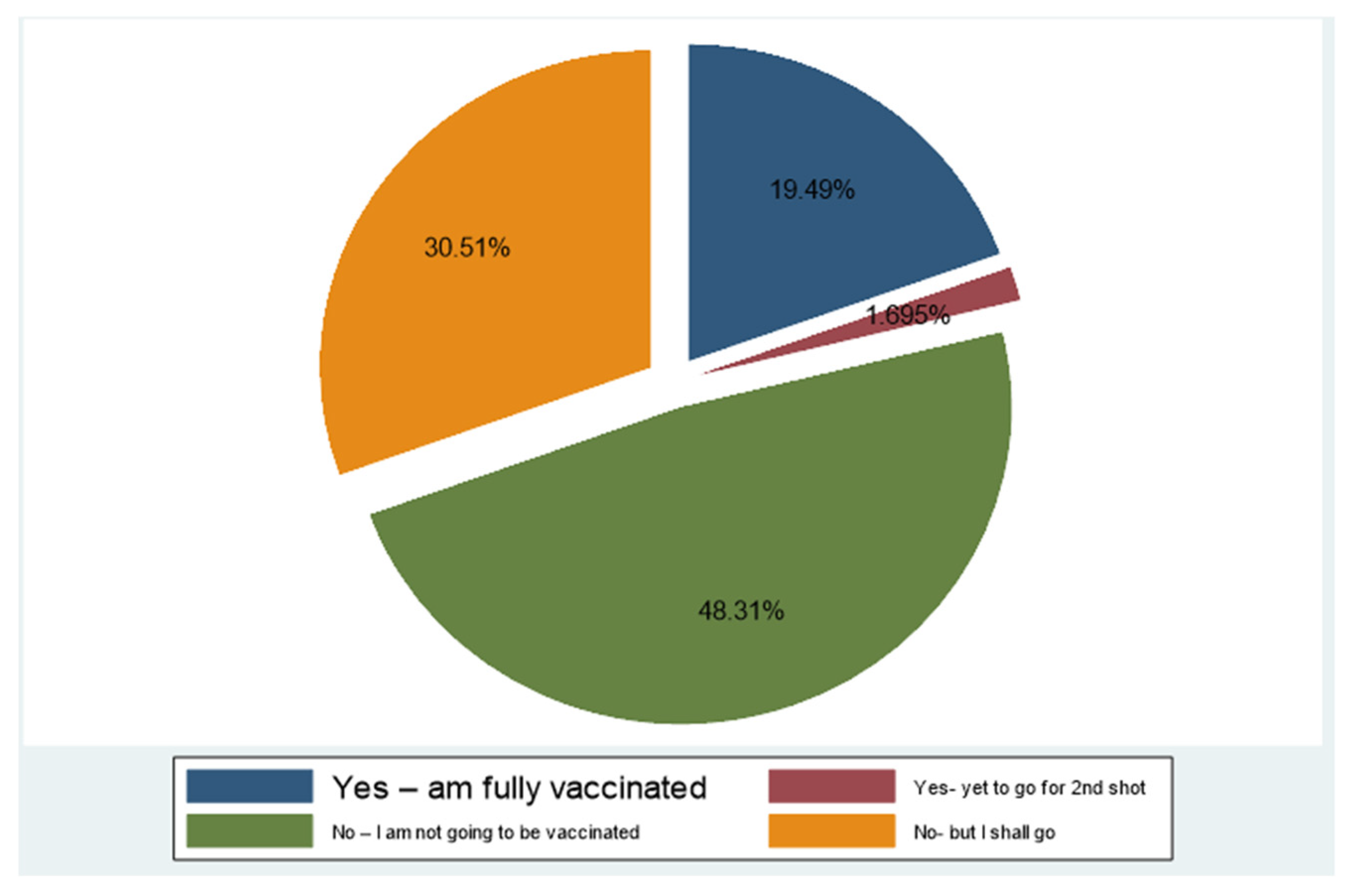

When asked if they are vaccinated, most of the participants (48.3%) responded that they are not vaccinated, and that they are not planning to get vaccinated, while 30.51 per cent are still not vaccinated but planning to get vaccinated, but delaying it. This shows the high level of vaccine hesitancy (78.8%) among the respondents. Only 19.49 per cent reported that they were fully vaccinated, and 1.69 per cent reported receiving only one vaccination.

Causes of Hesitancy

The previous sections confirmed the existence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitance within Nelson Mandela Bay. Of interest then, is what are the possible drivers of such behaviours. The authors started by inquiring whether one had ever refused any other vaccination (other than the COVID-19 vaccine). A surprising majority (58.41% of the sample) had not refused any other vaccines in the past, yet, as depicted, the majority are not willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

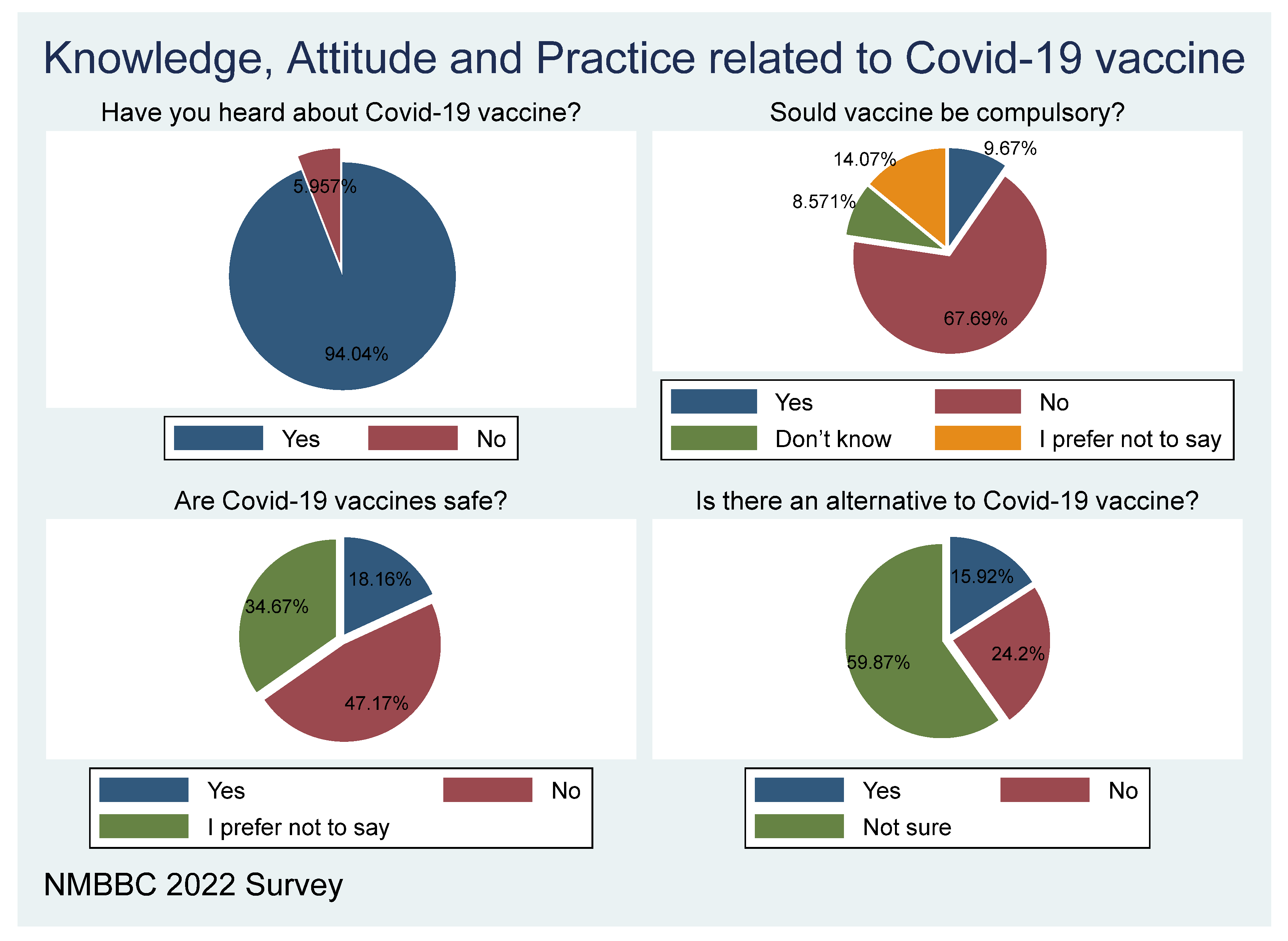

Figure 4 above shows that 93.82 per cent of the participants have heard about the COVID-19 vaccine, while only 6.18 per cent responded “No”, which means that they haven’t heard about the vaccine. In one question, where respondents were asked whether the government should make vaccines compulsory, bearing in mind that not all those who disagree are unvaccinated, most of the participants, representing 69.7 per cent were against it, while the participants that were in favour were 10. 21 per cent, and the others who responded preferred not to respond, and those who did not know were 12.01 per cent and 8.10 per cent respectively. This means that more people are against vaccine enforcement (compulsory vaccination), a sign of high hesitance toward the vaccine! The variable was recorded for further analysis including the vaccine hesitance ratio.

The beliefs or perceptions around the safety of the vaccine show that 47.44 per cent of respondents do not believe that vaccines are safe for them, and 33.95 per cent prefer not to respond, while 18.6 per cent believe vaccines are safe for them. This shows that there is a greater sense of not trusting the safety of the vaccine among the respondents.

The majority of respondents do not believe that vaccine is the best solution for Covid-19; this is shown by 24.2 per cent who believe there is another solution than vaccination, while 59.87 per cent of the sample who responded are not sure, and only 15.92 per cent (less than 1 in every 5) believe that vaccine is the best solution for COVID-19. This shows high hesitancy on COVID-19 if the not sure and yes respondents are combined.

Table 1.

Reasons for refusing any vaccination in the past.

Table 1.

Reasons for refusing any vaccination in the past.

| |

Freq. |

Percent of responses |

Percent of cases |

| I never refused a vaccine recommended by a healthcare worker |

198 |

32.57 |

58.41 |

| Did not think it was needed |

61 |

10.03 |

17.99 |

| Did not have enough information on the vaccine |

80 |

13.16 |

23.6 |

| Did not think the vaccine was effective |

58 |

9.54 |

17.11 |

| Did not think the vaccine was safe |

74 |

12.17 |

21.83 |

| I was concerned about side effects |

93 |

15.3 |

27.43 |

| I had a bad experience with a previous vaccination |

23 |

3.78 |

6.78 |

| Did not know where to get the vaccination |

6 |

0.99 |

1.77 |

| Other logistic problems |

15 |

2.47 |

4.42 |

Different strategies have been used to decrease COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, including information packages disseminated via various platforms, and role models (popular personalities), among others. When asked: Do you find the information conveyed by popular personalities (local and international) helpful? The results are displayed in

Figure 5, which shows that 34.98 per cent of the information conveyed by popular personalities is somewhat helpful, with 16.22 per cent who believe that they are very helpful, and 25.95 per cent not sure. Overall, however, the majority (cumulatively 70.50%) agree that it is at least somewhat helpful.

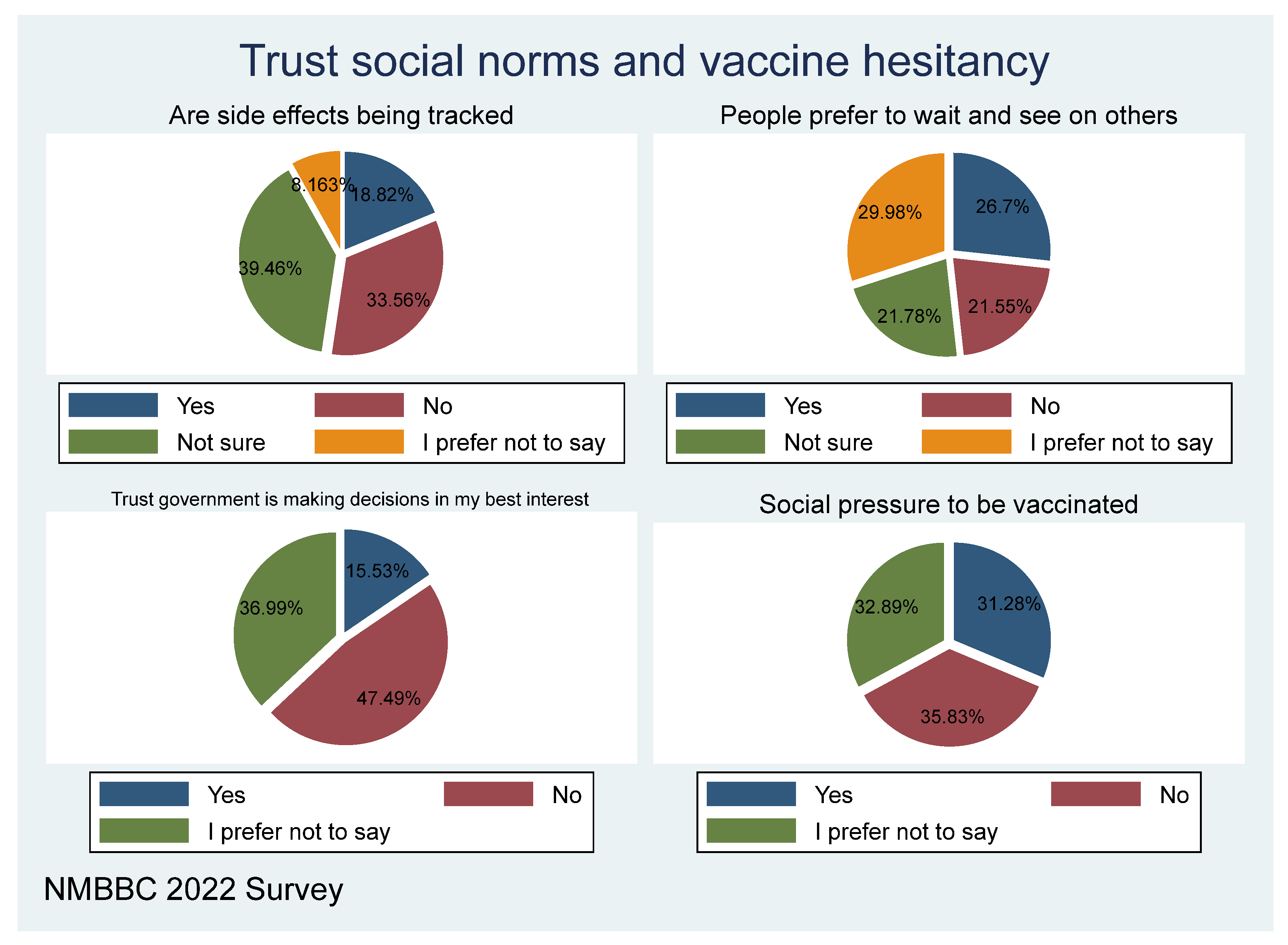

Management of the pandemic needs to win the trust of the population for buy-in on its effects to address it. Only 18.44 per cent believe that side effects of the vaccine are being appropriately tracked, with 34.51 per cent responding no. The majority of 45.72 per cent of respondents highlighted that they don’t trust the government. A third of the sample consider that, in general, individuals follow a wait and see approach—this is common when available information is inadequate and/or not trusted. This is like experimenting with fellow members of the community, a kind of approach where, “if nothing happens to others, then I will follow a suit”. Approximately, 37.1 per cent believe that those vaccinated are mostly due to social pressure.

Based on the data sample, almost 97 per cent of respondents have heard about the COVID-19 vaccine, while only 3 per cent claim to have no knowledge about the vaccine. Hearing about the vaccine is dependent on how such information is disseminated, and the strategies used to implement the vaccine rollout. The internet and social media platforms have been leveraged in distributing COVID-19 vaccine information nationwide.

The results (

Table 2) of the model (logistics model) show that generally, the youth age group believe that there is a better alternative treatment for COVID-19 compared with older people, which means there is higher hesitancy amongst the youth group. Females believe that there is no better alternative treatment for COVID-19 compared with males, therefore there is less hesitancy amongst females compared with males. The religious factor shows that Christians are more likely to believe that the are other better alternative treatment for COVID-19 compared with other religious groups, which means that Christians are more hesitant in taking the vaccine. Higher educated respondents believe that there is no better alternative treatment compared with non-tertiary respondents, which shows that among tertiary respondents there is less hesitancy in taking the vaccine. High-income earners believe that there is a better alternative treatment compared with low-income earners, which show high hesitancy among the high-income group.

Having adequate information regarding COVID-19 shows that respondents are less vaccine hesitant by believing that there is no better alternative treatment compared with having less information, and this suggests that adequate information reduces high hesitancy among the respondents. Respondents show that being satisfied with the information provided by health care workers increases the likelihood of believing that there is no better alternative for COVID-19 treatment (hence reduces hesitancy) compared with not being satisfied, which increases the likelihood of hesitancy. Trust in government increases the likelihood of believing that there is no better alternative treatment for COVID (hence reducing vaccine hesitancy) compared with a lack of trust in the government. Being socially pressured to get vaccinated increases the high rate of hesitancy and the belief that there is alternative treatment compared with not being pressured by social networks. Having information about which vaccine to take reduces the belief that there is an alternative treatment for COVID-19, compared with not knowing which vaccine to take, and this reduces vaccine hesitancy.

The socio-demographic factors such as sex, education, employment, income, having children at home, and the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 were all significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy. Some literature has highlighted that females are less likely to be vaccinated, which contributes to vaccination hesitancy (Al-Mohaithef & Padhi, 2020; Anakpo & Mishi, 2022; Callaghan et al., 2020; Earnshaw et al., 2020). Similarly, women may be more hesitant than men to receive COVID-19 vaccines (Katoto et al. 2021, Coorper et al. 2021) though are more susceptible to the virus (Komanisi, Anakpo, & Syden, 2022). Callaghan et al. (2021), reported that women have greater vaccine hesitancy than men. Women often bear most of the responsibility for family healthcare, so it may be that women are generally more aware of and concerned about the negative side effects of vaccinations (Callaghan et al. 2021).

In addition. There are mixed results for age on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, with studies showing both greater hesitancy for young people in some studies, and no effect of age in others (Robertson et al. 2021, Allington, McAndrew, Moxham-Hall, Duffy 2021). As people with low socioeconomic status have been disproportionately impacted, this may explain, in part, the link between vaccine hesitancy, distrust, low monthly income, and ethnic disparity (Katoto et al. 2021). Low levels of educational attainment have been generally associated with greater vaccine hesitancy (Makarovs and Achterberg, 2017). More educated people have greater scepticism of the scientific mechanisms of the medicine and its efficacy and safety, while less educated people may decline vaccination due to a lack of information.

Influences have been reported to emerge from lack of knowledge, personal perception of the vaccine, or influences of the social/peer environment. Paul, Steptoe, & Fancourt, (2021) reported that low knowledge about COVID-19 also increases vaccination hesitancy. Pivetti, Di Battista, Paleari, & Hakoköngäs, (2021) found that conspiracy beliefs negatively predicted general attitudes toward vaccines. According to Amit, Pepito, Sumpaico-Tanchanco, and Dayrit (2021), individuals’ perceptions and attitudes play a significant role in the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19, or not. The authors also documented that individual barriers to vaccination include a lack of knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about science, vaccines, the health system, and the government. According to Amit et al. (2021), these perceptions are shaped by (mis)information exposure amplified by social media, community, and the health system. Depending on how one feels about vaccines, one’s social network may have a positive or negative impact on vaccination uptake.

As a result, interpersonal barriers, such as networks and social capital, influence health beliefs, and decisions. Other studies have found that negative interactions with the healthcare system may lead to vaccine hesitancy (Marzo, et al. 2022; Katoto et al. 2021). Others delayed getting vaccinated because they wanted to see how vaccines worked on other people and pointed out potential side effects (Coorper, et al. 2021). As a result of the preceding statement, vaccines are regarded as dangerous and lethal (Amit et al. 2021). The authors further revealed that to reduce the detrimental consequences of conspiracy beliefs, exposure to anti-conspiracy arguments, both before and after exposure to conspiracy theories, can restore the vaccination intention (Jolley and Douglas 2017; Lyons, Merola, & Reifler, 2019).

Participants believed that this vaccine used the same virus to ‘immunize’ an individual’s system, which could have unintended consequences. Other participants cited that this specific brand was not recognised by other countries, and therefore wanted and waited for other vaccines (Amit et al. 2021). Meanwhile, others refused to receive vaccines due to beliefs about their safety and effectiveness (Amit et al. 2021). Another reason for COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy is a lack of trust due to the belief that the vaccine moved too quickly through clinical trials, and there is a widespread belief that vaccination is extremely risky, resulting in serious health consequences (Anakpo & Mishi, 2022; Roberts et al., 2021). Similarly, according to Khubchandani et al., (2021), participants in America believed that socio-political factors and pressures could lead to a rushed approval of the COVID-19 vaccine without assurances of safety and efficacy. Campo-Arias & Pedrozo-Pupo (2021) and Neumann-Böhme et al. (2020) found, in their separate studies, that the psychological factors that affect COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy include trust in the vaccine and fear of side effects.

Factors explaining vaccine hesitance—[hesitancy based on belief of alternative ways] The results (

Table 3) of the study show that generally youth find, or believe, that the COVID-19 vaccine is not safe compared to older people, which means that they are more hesitant. Females are likely to believe that vaccine is safe compared to males, and this means that females are less hesitant than males. Religion factor shows that Christians are more likely to find or believe the vaccine is not safe compared with other religious groups, and this means that they are more hesitant. Respondents who are at the tertiary level are more likely to believe the vaccine is not safe compared with respondents who are non-tertiary, and this means that educated people are more hesitant. High-income earners are more likely to believe that vaccine is not safe for them compared to lower-income earners, which means that high-income groups are likely to be hesitant to be vaccinated.

The role of healthcare workers in providing the relevant information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine increases the likelihood of respondents believing that the vaccine is safe compared with those who were not satisfied with the information provided by health care workers; this means that they are likely to be less hesitant

The respondents have highlighted that those who trust government are likely to believe that the vaccine is not safe for them compared with those who don’t trust the government. Those that are pressured by their social network believe that vaccine is not safe compared with the respondents that are not pressured by social network. Those who know which vaccine to choose from are more likely not to believe that vaccine is safe, compared to those who do not know which vaccine to choose. On the other hand, there are influences arising due to historic, sociocultural, environmental, health system/institutional, economic, or political factors. Amit et al. (2021) also stated that political issues play a role in vaccination hesitancy. In their study on vaccine hesitancy in South Africa, Coorper et al. (2021) stated that political factors will play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination. Political discontent or disillusionment may play a role; people who had positive attitudes toward the government in general and its handling of COVID-19, were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccination. The structural barriers are vaccine procurement, supply, and logistics, as well as media and policy issues. Katoto et al. (2021) discovered that among respondents, government distrust was associated with vaccine hesitancy. Political affiliation perceived the risk of contracting COVID-19 also as a significant predictor of vaccine hesitancy (Katoto et al. 2021; Guidry et al.2021).

The findings of Barello et al. (2020) suggest that vaccination attitudes are influenced not only by students’ level of health knowledge, but also by other motivational and psychological factors, such as a sense of individual responsibility for population health and a common sense about the value of civic life and social solidarity, as demonstrated by other studies on the COVID-19 pandemic and previous emergencies. Not only the general public, but also those pursuing a career as a health professional, appear to be struggling to keep up with a growing body of evidence, increasingly complex information, and conflicting feelings about vaccines. Therefore, public health information campaigns should also be supported by other actions aimed at raising students’ consciousness regarding the crucial role of individuals’ engagement in safeguarding their own and others’ health through vaccination. Other reasons for COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy due to the time frame between vaccine development, production and availability was too short, politics surrounding the vaccine development process, misinformation from social media, previous COVID-19 infection or health conditions, health experts, and pharmaceutical companies (Anakpo & Mishi, 2022; Biswas et al. 2021; Katoto et al. 2021). Wiysonge et al. (2022) also found from their empirical evidence on vaccination hesitancy in South Africa, that individuals’ vaccination attitudes and practices are often the result of a continuing engagement that is based on evolving personal and societal circumstances, which may alter over time. The authors added that as COVID-19 vaccination expands internationally, scientists and policymakers must examine the extent and drivers of vaccine hesitancy in each environment to design specialized and focused methods to combat it.

Implications on Economic Recovery

Behaviour of individuals has implications for the rest of the economy, as is the case of vaccination. Due to the inherent risk of the pandemic, and one that an individual cannot easily identify where the risk lies, risk aversion becomes the dominant strategy. A risk-averse individual does their best to avoid a risk environment/decision/situation, while a risk taker has no restraint. Given the much-publicised effects of COVID-19 in terms of sickness, hospitalisation, and death, any option to avoid infection is likely to be appreciated by risk-averse individuals. Therefore, the vaccinated are likely to be risk averse; they prefer the safer option of the benefit that comes with vaccination (no matter how small it is) than experiencing the worst. Although one could argue that taking the vaccine is the riskier decision given the myths and misinformation, the limited cases of hospitalisation and death of the vaccinated is enough to warrant vaccination as a safer decision for a risk-averse individual.

Taking that the unvaccinated are risk averse, it is sufficient to say they have limited restraint in traveling and going out as per prior COVID-19 period; on the other hand, the vaccinated, the more risk averse, are likely to be fearful to go out, given the knowledge that there are some who are unvaccinated. By intuition, one gets vaccinated because they believe the pandemic is real, not fiction; therefore, the risk of going out is higher. When movement is restrained, it affects businesses that rely on the movement of people such as sit-in restaurants, the tourism sector, transport sector, among many others (including the informal sector).

Furthermore, vaccination hesitation may negatively affect economic recovery through international trade constraints. The outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic has defined and shaped international and travel laws, rules, and policy in two phases; the first was the complete closure of borders following the outbreak of the pandemic, thus disrupting business activities, livelihood, international trade (Anakpo & Mishi, 2021; Jafta, Anakpo & Syden, 2022; Anakpo, Nqwayibana & Mishi, 2023; Anakpo, Hlungwane and Mishi, 2023) and productivity (Anakpo, Nqwayibana, & Mishi, 2023). The second phase was the opening of international borders (for instance airport) to those who have taken the COVID-19 vaccine following its development and availability. Thus, vaccine hesitancy will compromise international trade, travel, and business activities, posing potential thread to economic recovery especially in low and middle-income countries.

Additionally, economic recovery may also be affected through unemployment of the unvaccinated. As part of preventive measures, some companies have made vaccination a mandatory exercise for all employees. Consequently, employees who fail to take the vaccine are given automatic exit from the company and this may lead to unemployment and low productivity and low economic recovery.

Vaccination hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries is more likely to foster development of new variants that could overcome current vaccines which may cause another economic downturn.

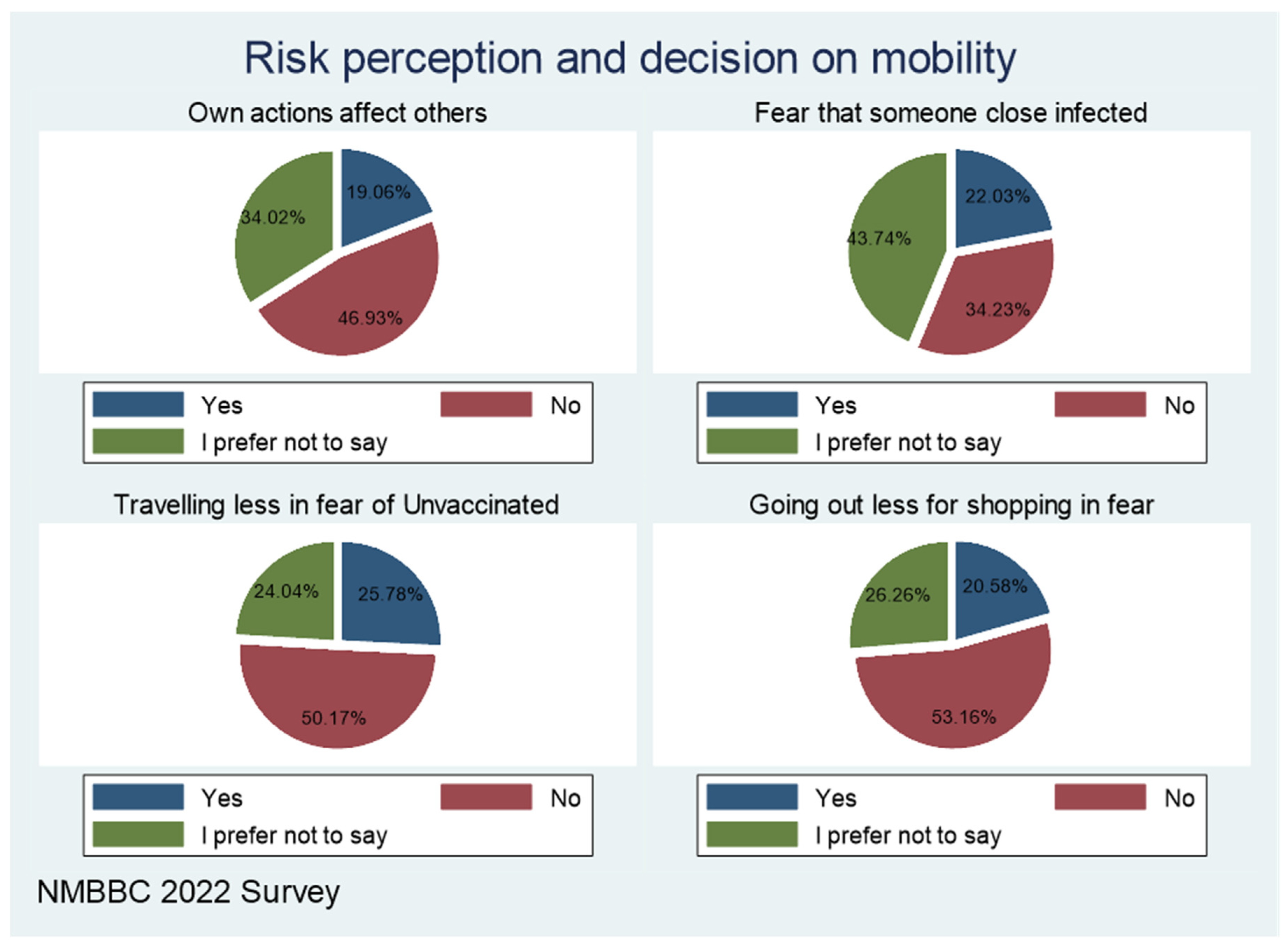

The chart in

Figure 6 shows how risk perception does affect mobility. The majority (nearly 50%) of the respondents do not believe their actions affect others. This implies, that when one decides not to vaccinate, they do not think it has implications for others.

Only 22 per cent fear that someone closer to them such as workmates, schoolmates, and family can infect them with COVID-19. At the peak of COVID-19, many people were interested in attending gatherings; it may well have been justified by this thinking that someone a person they know is unlikely to infect me. About 20-25 per cent are traveling less for fear of being exposed by those not vaccinated.

If vaccine hesitancy, which this study confirms exists, negatively affects businesses, this means recovery is going to take longer than projected, with repercussions on household income and overall wellbeing. Strategies need to be developed on how to improve vaccine uptake, and as argued above, it starts with understanding the social structure and the trusted sources of information. That trust is the greatest asset of many individuals and communities and relies on it in deciding. This is backed by social network theory, where the information held by the most central person (nucleus of the network), easily diffuses, and is more positively received than information shared by strangers or any less trusted sources (peripheral elements).

As mentioned in the background, many governments and authorities have taken the effort to study behaviour of individuals by setting up behavioural insight units. These track the mood of the populace, how individuals are likely and responding to policy changes, and various calls to action. That helps with a higher uptake, support and effectiveness of policy or any interventions. The Western Cape Provincial government have established such a unit which spearheaded behavioural change when the water crisis day zero was imminent—their efforts were successful. Many programmes are ongoing being guided by such behavioural insights. The business chamber can play a role in establishing such, for the benefit of the business and general community. The insights are required towards guiding recovery efforts.

Conclusions

Hesitancy to COVID-19 vaccination is a major threat to public health with far reaching implication. This study uses empirical data in the context of South Africa to examine factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and implications on economic recovery. Findings reveal key socio-demographic and institutional drivers of COVD-9 vaccine hesitancy, which include Age (the younger are more hesitant than the older generation), Inadequate information received about the vaccine (those who perceive they have adequate information are vaccinated), trust issues in government institutions, conspiracy beliefs, vaccine-related factors, and perceived side effect associated with the vaccine. Additionally, an individual’s decision to remain hesitant to COVID-19 vaccination has implications on businesses and the economy by limiting movement and trade, increasing unemployment and resurgence of new variants. The decision to vaccinate is mainly affected by family members than information received on other platforms or any other person. Public movement through community and family members for communication strategies will help promote vaccine intake. These strategies should effectively address community concerns with side effects and potential health risks by disseminating information and increasing the population’s knowledge of the vaccine, in addition to its risk factors, effectiveness, and side effects. Other reliable institutions on vaccine information include health workers and mass media (TV and Radio). Other action plans such as information dissemination, convenience vaccination centres, consistence communications and targeted campaign strategies are recommended for improving vaccine intakes and positive economic recovery.

Author Contributions

All authors contribute to the various sections of the research.

Funding

This project was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)‘s COVID-19-fund. Through a financial allocation to GIZ’s Natural Resources Stewardship Programme (NatuReS), a special project was designed together with the Nelson Mandela Bay Business Chamber (NMBBC) as a response to address the spread of the virus and its adverse impacts on economic and social development in the Nelson Mandela Bay area.

Acknowledgments

This paper would not have been possible without support of the following institutions; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, GIZ, NatuReS, Nelson Mandela Bay Business Chamber and Nelson Mandela University. Special acknowledgement goes to the following individuals for their invaluable contributions; Mr Prince Matonsi, Mr Renzo Driussi and Mr Siyabonga Mchunu, Ms Khanyisa Nomda.

Ethics

The project received ethical clearance from the Nelson Mandela University, reference number: H22-BES-ECO-031. The views contained herein do not necessarily represent the views of the funder and funding partners, or that of Nelson Mandela University.

References

- Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B. (2021). Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine. 2021;:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M., & Padhi, B. K. (2020). Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare, 13, 1657–1663. [CrossRef]

- Amit A.M.L, Pepito V.C.F, Sumpaico-Tanchanco L, Dayrit M.M. (2022) COVID-19 vaccine brand hesitancy and other challenges to vaccination in the Philippines. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(1): e0000165. [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G., Nqwayibana, Z., & Mishi, S. (2023). The Impact of Work-from-Home on Employee Performance and Productivity: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(5), 4529. [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G.; Hlungwane, F.; Mishi, S (2023). The Impact of COVID-19 And Related Policy Measures on The Livelihood Strategies in Rural South Africa. Afr. Agenda.

- Anakpo, G & Mishi S. (2022). Hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccines: Rapid systematic review of the measurement, predictors, and preventive strategies, Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G., Nqwayibana, Z., & Mishi, S. (2023). The Impact of Work-from-Home on Employee Performance and Productivity: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(5), 4529. [CrossRef]

- Annas, S., & Zamri-Saad, M. (2021). Intranasal vaccination strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic from a veterinary medicine perspective. Animals, 11(7), 1876. [CrossRef]

- Barello, S., Nania, T., Dellafiore, F., Graffigna, G. and Caruso, R., 2020. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. European journal of epidemiology, 35(8), pp.781-783. [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.L. and Mauldin, R.F. (2021). The “anti-vax” movement: a quantitative report on vaccine beliefs and knowledge across social media. BMC Public Health 21, 2106 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.R.; Alzubaidi, M.S.; Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Shah, Z. (2021). A Scoping Review to Find Out Worldwide COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Underlying Determinants. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Bono, S.A.; Faria de Moura Villela, E.; Siau, C.S.; Chen, W.S.; Pengpid, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Sessou, P.; Ditekemena, J.D.; Amodan, B.O.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; (2021). Factors Affecting COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: An International Survey among Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 515. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Noel T., Buttenheim, Alison M., Clinton, Chelsea V., et al.. “Incentives for COVID-19 vaccination.” The Lancet Regional Health—Americas, 8, (2022) Elsevier: . [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, T. Moghtaderi A, Lueck J, Hotez P, Strych U, Dor A et al.(2021). Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Social Science & Medicine. 2021; 272:113638. [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A., & Pedrozo-Pupo, J. C. (2022). Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines in Colombian university students: Frequency and associated variables. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 92(6). doi:10.23750/abm.v92i6.11533.

- Chadwick, A., Kaiser, J., Vaccari, C., Freeman, D., Lambe, S., Loe, B. S., Vanderslott, S, Lewandowsky, S., Conroy, M., Ross, A.R.N, Pollard,A.J., Waite, F., Larkin,M., Rosebrock, L., Jenner, L., McShane, H., Alberto Giubilini,A., Petit, A. and Yu, L. M. (2021). Online Social Endorsement and Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United Kingdom. Social Media + Society, 7(2), 205630512110088. [CrossRef]

- Chevallier C, Hacquin AS, Mercier H. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: shortening the last mile. Trends Cogn Sci. 25 (5):331–33. [CrossRef]

- Coorper, S., van Rooyen, H., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: how can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Review of Vaccines, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, J., Lockyer, B., Moss, R.H., Endacott, C., Kelly, B., Bridges, S., Crossley, K.L., Bryant, M., Sheldon, T.A., Wright, J. and Pickett, K.E., (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in an ethnically diverse community: descriptive findings from the Born in Bradford study. Wellcome Open Research, 6, p.23.

- Dubé, E., & MacDonald, N. E. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 1-2.

- Earnshaw, V. A., Eaton, L. A., Kalichman, S. C., Brousseau, N. M., Hill, E. C., & Fox, A. B. (2020). COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Translational behavioral medicine, 10(4), 850-856. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K. A., Bloomstone, S. J., Walder, J., Crawford, S., Fouayzi, H., & Mazor, K. M. (2020). Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Annals of internal medicine, 173(12), 964–973. [CrossRef]

- Gqoboka, H., Anakpo, G., & Mishi, S. (2022). Challenges Facing ICT Use during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises in South Africa. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 12(9), 1395-1401. DOI:10.4236/ajibm.2022.129077.

- Guidry, J.P.D.; Laestadius, L.I.; Vraga, E.K.; Miller, C.A.; Perrin, P.B.; Burton, C.W.; Ryan, M.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Carlyle, K.E. (2021). Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine with and without Emergency Use Authorization. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Hayawi, K., Shahriar, S., Serhani, M.A., Alashwal, H. and Masud, M.M., (2021). Vaccine versus Variants (3Vs): are the COVID-19 vaccines effective against the variants? A systematic review. Vaccines, 9(11), p.1305. [CrossRef]

- Jafta, K., Anakpo, G., & Syden, M. (2022). Income and poverty implications of Covid-19 pandemic and coping strategies: the case of South Africa. Africagrowth Agenda, 19(3), 4-7.

- Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(8), 459-469. [CrossRef]

- Katoto, P.D.M.C.; Parker, S.;Coulson, N.; Pillay, N.; Coorper, S.;Jaca, A.; Mavundza, E.; Houston, G.;Groenewald, C.; Essack, Z.; et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in South African Local Communities: The VaxScenes Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 353. [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, J., Sharma, S., Price, J. H., Wiblishauser, M. J., Sharma, M., & Webb, F. J. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. Journal of Community Health, 46(2), 270–277. [CrossRef]

- Komanisi, E., Anakpo, G., & Syden, M. (2022). Vulnerability to COVID-19 impacts in South Africa: analysis of the socio-economic characteristics. Africagrowth Agenda, 19(2), 10-12.

- Largent EA, Miller FG. Problems With Paying People to Be Vaccinated Against COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(6):534–535. [CrossRef]

- Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. M. D., & Paterson, P. (2014). Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine, 32(19), 2150–2159. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B., Merola, V., & Reifler, J. (2019). Not Just Asking Questions: Effects of Implicit and Explicit Conspiracy Information About Vaccines and Genetic Modification. Health Communication, 34(14), 1741-1750. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N. E., & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. [CrossRef]

- Makarovs K, and Achterberg P. (2017). Contextualizing educational differences in “vaccination uptake”: A thirty nation survey. Social Science & Medicine. 2017; 188:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Sami, W.; Alam, M.Z.; Acharya, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Songwathana, K.; Pham, N.T.; Respati, T.; Faller, E.M.; Baldonado, A.M.; (2022). Hesitancy in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake and Its Associated Factors among the General Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study in Six Southeast Asian Countries. Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 4. [CrossRef]

- Mylan S, and Hardman C. COVID-19, cults, and the anti-vax movement. Lancet. 2021 Mar 27;397(10280):1181. [CrossRef]

- Ndugga N, Hill L, Artiga S, and Parker N. (2021). Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity [Internet]. KFF. 2021. Available from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issuebrief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/ [Accessed on 23 March 2022].

- Neumann-Böhme, S., Varghese, N.E., Sabat, I., Barros, P.P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., Schreyögg, J. and Stargardt, T., (2020). Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics, 21(7), pp.977-982. [CrossRef]

- Orosz, G., Krekó, P., Paskuj, B., Tóth-Király, I., Böthe, B. and Roland-Lévy, C. (2016) ‘Changing conspiracy beliefs through rationality and ridiculing’, Frontiers in Psychology, 7(279): 1525. [CrossRef]

- Pandolfi F, Franza L, Todi L, Carusi V, Centrone M, Buonomo A, Chini R, Newton EE, Schiavino D, Nucera E. The Importance of Complying with Vaccination Protocols in Developed Countries: “Anti-Vax” Hysteria and the Spread of Severe Preventable Diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25(42):6070-6081. [CrossRef]

- Paul, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health—Europe, 1, 100012. [CrossRef]

- Pivetti, M., Di Battista, S., Paleari, F. G., & Hakoköngäs, E. (2021). Conspiracy beliefs and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccinations: A conceptual replication study in Finland. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Razai, M. S., Osama, T., McKechnie, D. G. J., & Majeed, A. (2021). Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ, n513. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B., N. Bohler-Muller, and J. Struwig, South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) (Round 17) Brief report. Summary findings: Attitudes towards vaccination. 2021 March 12 [cited 2021 Mar 17], South Africa: Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division, Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC).

- Robertson E, Reeve K, Niedzwiedz C, Moore J, Blake M, Green M et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2021; 94:41–50. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E., Jones, A., and Daly, M. (2020) International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. [CrossRef]

- Runciman, C., Alexander, K., Bekker, M., Bohler-Muller,N., Roberts, B., & Mchunu N., (2021) SA survey sheds some light on what lies behind coronavirus vaccine hesitancy, in Daily Maverick [Internet]. 2021 January 27 [cited 2021 Mar 17].

- 08 February.

- Savulescu, J., Pugh, J. & Wilkinson, D. Balancing incentives and disincentives for vaccination in a pandemic. Nat Med 27, 1500–1503 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Thirumurthy H, Milkman KL, Volpp KG, Buttenheim AM, Pope DG (2022) Association between statewide financial incentive programs and COVID-19 vaccination rates. PLoS ONE 17(3): e0263425. [CrossRef]

- Wiysonge, C. S., Ndwandwe, D., Ryan, J., Jaca, A., Batouré, O., Anya, B. P. M., & Coorper, S. (2022). Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: could lessons from the past help in divining the future?. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 18(1), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- World Bank (2015). World development report: mind, society and behavior. World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Behavioural considerations for acceptance and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines: WHO Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and Sciences for Health, Meeting Report, 15 October 2020. 2020.

- Wong CA, Pilkington W, Doherty IA, et al. Guaranteed Financial Incentives for COVID-19 Vaccination: A Pilot Program in North Carolina. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(1):78–80. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Raosoft a software that primarily calculates or generates the sample size of a research or survey (Raosoft Inc, 2004) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).