1. Introduction

Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc. (Rosaceae), as a famous traditional Chinese flower, has a very broad market prospect because of its elegant flower color, beautiful flower shape, and tranquil fragrance [

1]. It has been widely used in many festivals and horticultural expositions. However, since

P. mume generally blossoms in late winter and early spring, it cannot meet the viewing needs of other specific periods. Therefore, adjusting the

P. mume blossom to the target flowering period can not only meet the needs of the market and the public, but also has important significance for promoting the development of the flower industry.

At present, the commonly used methods for flowering regulation include temperature regulation, light treatment, external application of plant growth regulators and appropriate cultivation measures [

2], and temperature is one of the leading factors for regulating the flowering stage of woody plants.

P. mume, like most deciduous fruit trees, is very sensitive to temperature, so the regulation of its flowering period needs to be based on the study of chilling requirement (CR). CR refers to the effective hours of low-temperature demand for deciduous fruit trees to break natural dormancy. Generally, the accumulation of chilling capacity is considered to be the most effective factor for plants to break dormancy [

3]. Only when a certain low-temperature is accumulated can natural dormancy be successfully completed. The successful completion of this process is an important stage that must be experienced in the next growth and development cycle [

4]. If the chilling cannot be required, natural dormancy cannot be completed normally, even if the external conditions are suitable, it will inevitably cause growth and development disorders, flower bud (FB) cannot germinate at the right time, or germinate irregularly, and even cause deformity or severe abortion of flower organs [

5]. By mastering the CRs of cultivars, we can more accurately control the flowering period. At present, the most widely used estimation models for calculating the low-temperature accumulation of plants are: 7.2°C model, Utah model, and dynamic model. Among them, the 7.2°C model was proposed by Weinberger in the United States and is the simplest of many models [

6,

7]; The Utah model is the most widely used, which considers the effect of low-temperatures on the accumulation and the offsetting effect of high temperatures on low-temperatures [

8]. The dynamic model considers both the positive effects of chilling and the negative effects of high temperature on plant dormancy. However, this model has a disadvantage in that the method for estimating chilling demand is more suitable for tropical and subtropical regions [

9]. Another downside of the dynamic model is that the calculation method is relatively complicated and has not yet been widely adopted [

10,

11,

12].

As early as 1999, Ou Xikun used the “trial and error method” to conduct a computerized model study on the low-temperature demand of Taiwan’s fruit

P. mume cultivars, and evaluated the CRs of six local

P. mume cultivars in Taiwan [

13]. Zhuang Weibing et al. (2010) used the 7.2°C model, the 0-7.2°C model and the Utah model to study the CRs of 75

P. mume cultivars in Nanjing [

14]. The results showed that the CRs of the selected cultivars ranged from 183 CU ~1090 CU, and pointed out that the Utah model is more suitable for the statistics of CRs of

P. mume cultivars. Yang Yahui (2013) used the Utah model to make statistics on the CRs of ‘Meiren’, ‘Meifan’, and ‘Yanhong xingzhi’, and found that the CRs were 425 CU, 471 CU, and 466 CU, respectively [

15]. Zhihong Gao (2012) evaluated the chilling and heating requirements of six Japanese apricot species using three models, and established the correlation between CRs, heating requirements and flowering dates [

16]. However, different species and different cultivars of the same species also have different CRs due to their own characteristics and external environments. Therefore, exploring the CRs of different cultivars is of great significance for cultivation technology of

P. mume.

During the process of the plant undergoing low-temperature to release dormancy, a series of physiological changes occur in the FBs to resist low-temperature invasion, which enables the plants to improve their resistance to external environmental changes, control FB dormancy, and provide a basis for the recovery of growth and development [

17]. When the natural environment changes, the substances of osmotic adjustment in the FBs cooperate with each other to adjust the cell osmotic pressure and maintain the cell membrane structure [

18]. The formation of antioxidant system in plants will also maintain the metabolic balance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to prevent excessive accumulation of free radicals during dormancy and cause poisoning to plants. Therefore, the antioxidant enzyme system is closely related to the release of dormancy. In addition, plant endogenous hormones play a very important role in the process of inducing, maintaining and relieving FB dormancy, and abscisic acid (ABA) participates in regulating the initiation and maintenance of dormancy [

19]. Gibberellins such as GA

3 may play a role in the dormancy release [

20]. In addition, a large number of studies have shown that the flowering of deciduous woody plants is not only affected by a single type of hormone, but also by the mutual promotion and mutual antagonism of hormones.

At present, the research on the CR and physiological mechanism of woody plants mainly focuses on ornamental peaches, pears, crabapple, peonies and other plants, and there are few related studies on P. mume. In this research, four early-flowering P. mume cultivars were used as experimental materials, which were widely planted in Henan Region, China. The Utah model was used to count the minimum CR of each cultivar, and to explore the physiological changes in FBs during artificial low-temperature release dormancy. The research aims to provide a theoretical basis for the regulation of P. mume blossom flowering period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The experiment was carried out in the World Wintersweet Garden (34°09′N, 114°06′E) in Yanling, Henan, China from September to December 2021. Eight-year-old P. mume ‘Gulihong’, ‘Nanjing gongfen’, ‘Zaoyudie’, ‘Zaohualve’ grafted potted seedlings of four early-flowering cultivars were chosen. There are 30 plants of each variety, a total of 120 plants. The test seedlings are robust, compact, free of diseases and insect pests, branches are evenly distributed, buds are plump and full, and uniform in size, with a ground diameter of about 2.5 cm to 4.1 cm and a plant height of about 80 cm. The temperature controller of the cold storage is the XMK-7 type produced by Zhejiang Yuyao Mingxing Refrigeration Parts Factory, and the temperature accuracy is 0.1°C.

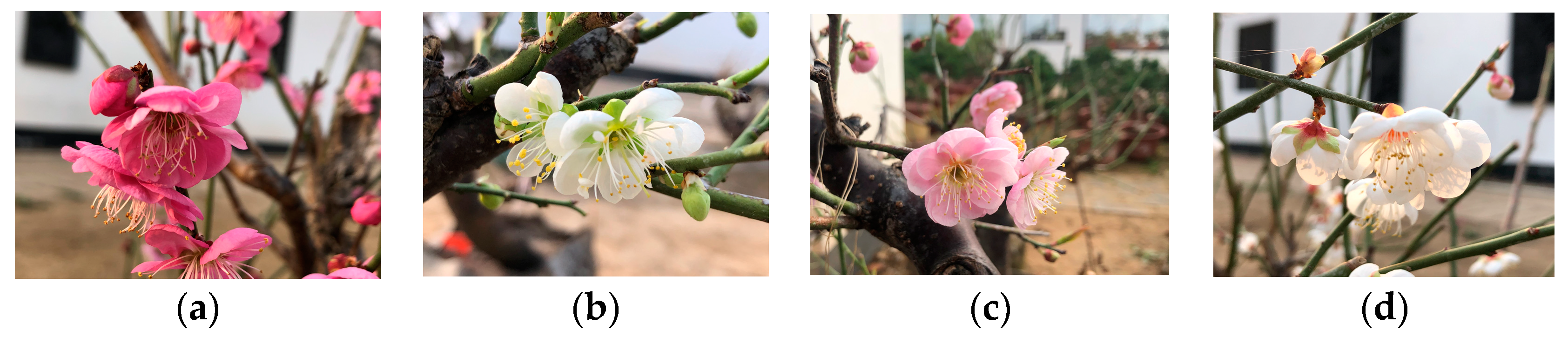

Figure 1.

The Prunus mume cultivars selected for the experiment. Among them, (a) P. mume ‘Gulihong’, it belongs to Cinnabar Purple Form, with green branchlets, reddish-brown skin of old branches, red inner skin, and deep red flowers. (b) P. mume ‘Zaohualve’, it belongs to Green Calyx Form, its calyx is green, the petals are saucer-shaped, and the flower color is white. (c) P. mume ‘Nanjing gongfen’, it belongs to the Pink Double Form, with slanted branches and pink flowers. (d) P. mume ‘Zaoyudie’, it belongs to Alboplena Form. The buds are milky yellow with red spots. The front side of the flowers is yellow and white. They all belong to the Upright Mei Group, Prunus mume var. typica.

Figure 1.

The Prunus mume cultivars selected for the experiment. Among them, (a) P. mume ‘Gulihong’, it belongs to Cinnabar Purple Form, with green branchlets, reddish-brown skin of old branches, red inner skin, and deep red flowers. (b) P. mume ‘Zaohualve’, it belongs to Green Calyx Form, its calyx is green, the petals are saucer-shaped, and the flower color is white. (c) P. mume ‘Nanjing gongfen’, it belongs to the Pink Double Form, with slanted branches and pink flowers. (d) P. mume ‘Zaoyudie’, it belongs to Alboplena Form. The buds are milky yellow with red spots. The front side of the flowers is yellow and white. They all belong to the Upright Mei Group, Prunus mume var. typica.

2.2. Experimental Method

2.2.1. Method for Measuring Chilling Requirements

After observing the internal differentiation of FBs in each cultivar is basically completed through the microscope, the experimental materials were placed in a 6°C constant temperature cold storage on September 6th for artificial low-temperature treatment, so that the dormant buds entered a deep dormancy state. 2000Lx lighting intensity and 8/16 hours (light/dark) lighting conditions were used to simulate the average light intensity of this latitude in autumn, and water was regularly sprayed on the ground to control the relative air humidity of the experimental environment to 80%. In order to get more accurate CRs of different cultivars, three pots of each cultivar were taken out from the cold storage every two days from September 17th to 27th, plants were moved moving out cold storage six times in total. After into the greenhouse, routine management such as regular watering and fertilization was carried out. For each cultivar, three pots of control plants were placed at natural environment and provided routine cultivation management. In the experiment, the hourly temperature was recorded by the temperature and humidity recorder, combined with the meteorological data provided by the China Meteorological Data Network. After 30 days of cultivation from the day of sampling, the FB germination rates of different cultivars were counted, and the signs of relieving dormancy were quantified.

There were three pots for each cultivar, and three repeated experiments were set up. Choose three trunks on each pot of each cultivar, and each trunk contains about three flower branches (about 270 FBs). The germination was based on the cracking and germination (red dew) at the top of the FBs. After 30 days of cultivation from the day of sampling, the FB germination rates of different cultivars were observed and recorded every day to quantify the signs of relieving dormancy. The test refers to the statistical method of Wang Lirong (1992) [

21]. The date when the branch germination rate reaches 10% is the date of entering natural dormancy. When the germination rate of the FB gradually rises and stabilizes to 50% or above, the corresponding sampling date is regarded as the end of natural dormancy of FBs; when the FB germination rate is between 60% and 70%, the average value of the accumulated low-temperature during this sampling period and the previous sampling period is taken as the CR of the cultivar; and if the germination rate exceeds 70%, the cumulative low-temperature in the previous sampling period is directly used as the CR of the cultivar. The date of release from dormancy and the amount of CRs of different cultivars were determined by observing the average germination rate of FBs under low-temperature treatment. The experiment used the Utah model to calculate the CRs of four

P. mume cultivars, and the unit is chill unit (CU). Its calculation formula is as follows:

Among them, Utaht represents the cumulative value of cold temperature units at the end of dormancy, Tu represents the effective low-temperature per hour, and 𝑇 represents the recorded temperature per hour.

2.2.2. Method for Measuring Physiological Indicators in FB Dormancy Period

The above-mentioned four cultivars were used in the experiment, and nine pots of each cultivar were used. Robust growth, well-developed, healthy and free from insect pests and mechanical damage in the middle and upper parts of the crown periphery were selected to determine the growth indicators and physiological indicators of FBs.

The FBs of the middle and upper part of the annual shoots were picked one day before the low-temperature induction treatment (0 d) and every eight days after the start of the treatment. Each time the FBs were collected, the FBs were wrapped in tin foil and stored in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at -80°C Stored in an ultra-low temperature refrigerator for use in physiological index determination. Weigh 0.5 g of fresh plant samples each time, and determine the soluble sugar (SS) content (anthrone colorimetric method, accurate to 0.01 mg·g-1), starch (ST) content (anthrone colorimetric method, accurate to 0.01 mg·g-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD) content (nitroblue tetrazolium photochemical reduction method, accurate to 0.01 U·g-1·min-1), peroxidase (POD) content (guaiacol method, accurate to 0.01 U·g-1·min-1) , catalase (CAT) content (potassium permanganate titration method, accurate to 0.01 U·g-1·min-1), abscisic acid (ABA) content (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ELISA, accurate to 0.01 ng·g-1), Gibberellin (GA

3) content (ELISA, accurate to 0.01 ng·g-1), the methodology refers to Li H [

22]and Gao J [

23] Experimental guidance. The determination of each physiological and biochemical index was repeated 3 times per period.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Office 2019 for data processing, Origin Pro 2022 was used for drawing, and SPSS 26 software was used for principal component analysis and significance analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Chilling Requirement for Dormancy Breaking

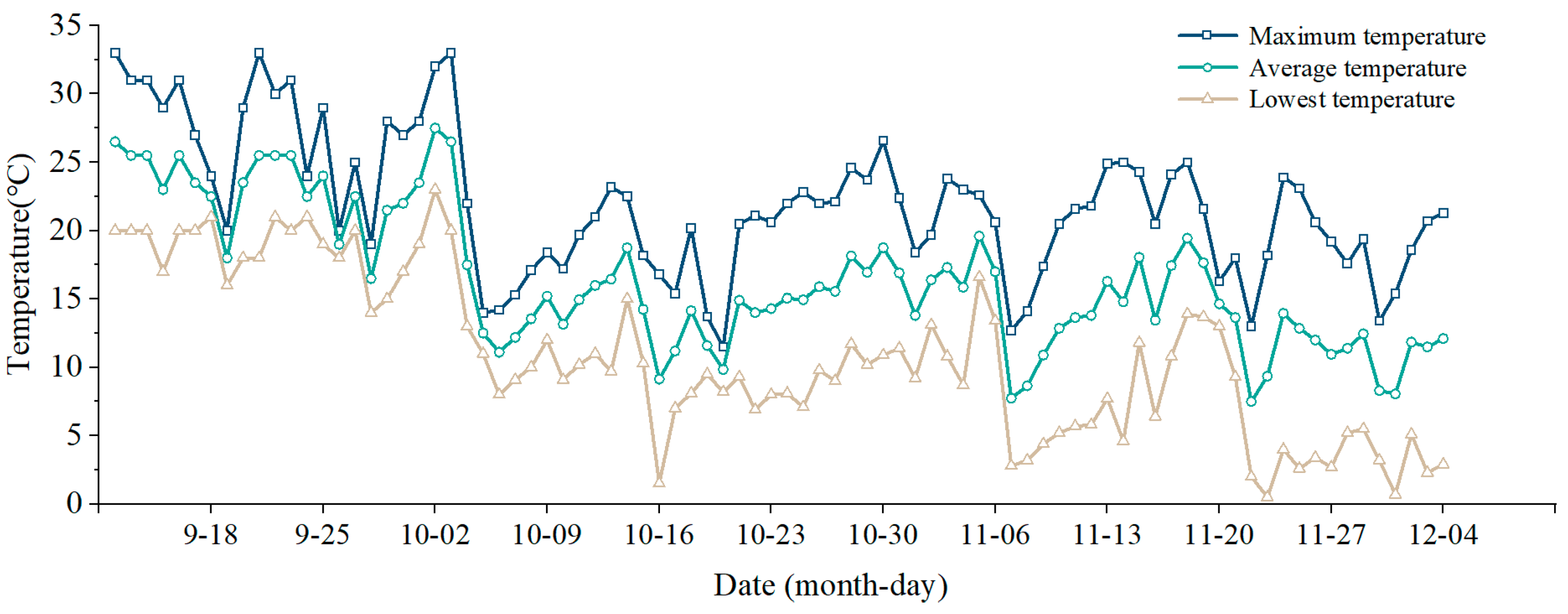

The temperature statistics during the experiment are shown in

Figure 2. The temperature statistics for the experiment were recorded from September 12th, 2021, and concluded when all cultivars had reached their full flowering stage. Analysis of the daily maximum temperature, minimum high temperature, and hourly temperature indicated significant fluctuations. The average temperature during this period was 16.4℃, with a relative humidity range of 30.2% to 89.3% and an average humidity of 58.2%. Notably, on October 3rd, the temperature peaked at 33.4℃, which was the maximum value within this period, followed by a fluctuating downward trend in temperature.

According to the sampling date corresponding to the FB germination rate, ≥ 50% is the end of dormancy, the FB germination rate under the same low-temperature accumulation is obtained through experiments, as shown in

Table 1. At the end of September, the FB germination rates of all cultivars have reached more than 60%, and the release time of FB dormancy of the four cultivars is relatively close, most of them are concentrated in the middle and late September; it shows that ‘Zaohualve’ passed the dormancy period the earliest, on the 15th day after entering the cold storage (September 21th), and ‘Gulihong’ had the latest dormancy release time (September 24th). However, none of the FBs of the control groups germinated during the entire course of the experiment.

Under the condition of artificial low-temperature treatment at 6°C, the results among cultivars have certain differences. According to the Utah model, the low-temperature accumulation of ‘Gulihong’ was the largest at 408 CU, and the low-temperature accumulation of ‘Zaohualve’ was the smallest at 348 CU, followed by ‘Nanjing gongfen’ and ‘Zaoyudie’, which are 396 CU and 372 CU, respectively.

Our results showed that FB germination rate was directly proportional to chilling accumulation and there was a positive correlation between refrigeration requirement and dormancy release date. However, without any artificial low-temperature treatment, the plants were still in a dormant state. This indicated that CR play an important role in the flowering process of P. mume.

3.2. Determination of Physiological Indicators during Low-Temperature Storage and Dormancy

3.2.1. Changes of SS and ST Contents in FBs during Low-Temperature Release Dormancy

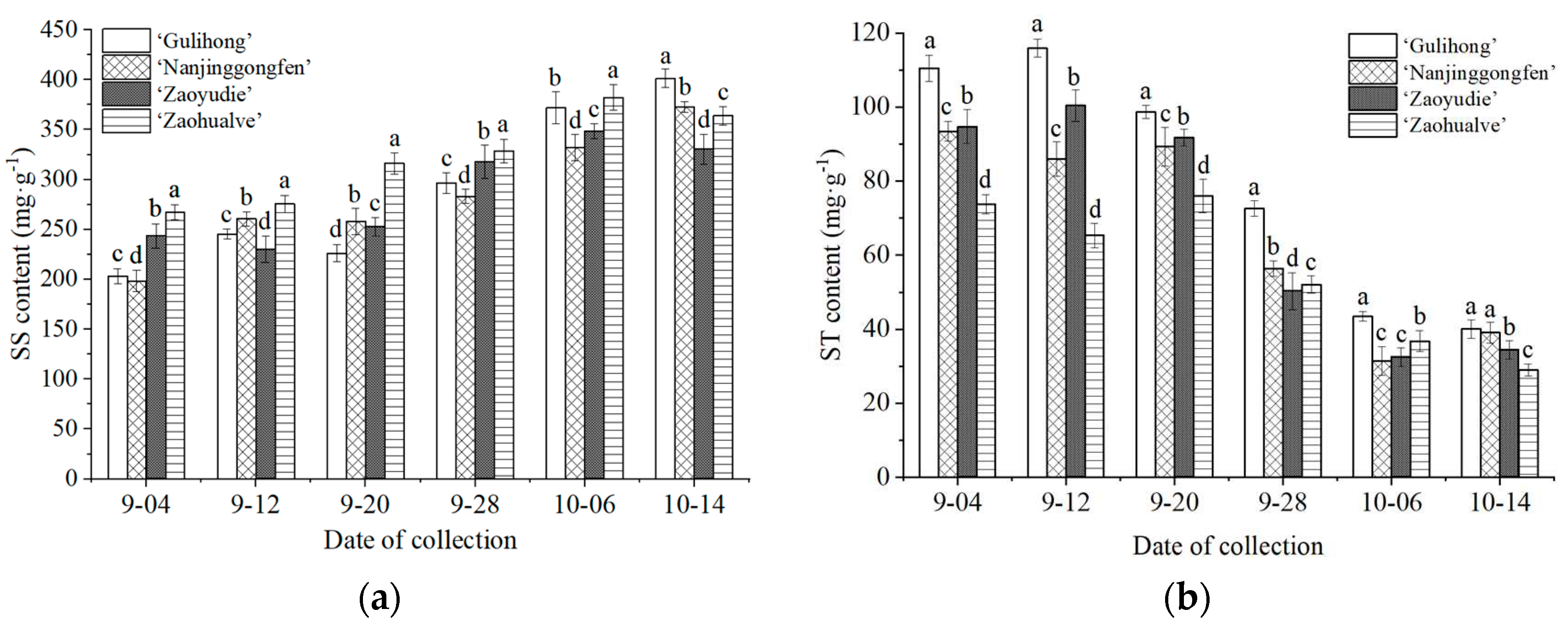

The changes of SS and ST contents in FBs of different cultivars during dormancy can be seen from

Figure 3. Compared to the control group that did not receive artificial low-temperature treatment, the contents of SS and ST in the FBs of different cultivars exhibited significant and regular changes when stored at 6°C. However, the trend of content change in FBs of different cultivars is slightly different. The SS content of the four cultivars showed a fluctuating upward trend with the increase of the chilling amount, while the ST content basically showed an opposite trend. In addition, before FB dormancy breaking, the SS content of ‘Zaohualve’, which has the least CR was higher. When the dormancy was completely released, the SS content of ‘Gulihong’, which required a higher amount of chilling gradually increased, was significantly higher than other cultivars. The ST content of ‘Gulihong’ was significantly higher than that of other cultivars at all stages.

The result indicated that the low-temperature treatment caused the stress response of the FBs, which resulted in changes in the substance content of the buds and promoted dormancy release. This also explains why the FBs in the control group, which did not receive low-temperature treatment, failed to germinate. In addition, FBs can gradually accumulate SS during dormancy to provide the energy needed during dormancy, and at the same time transform into ST to support germination and flowering during late dormancy. Cultivars with lower CR and early FB germination responded to low-temperature faster, and higher SS content was beneficial to release dormancy.

3.2.2. Effects of Low-Temperature on the Antioxidant Enzyme System in FBs during the Release of Dormancy

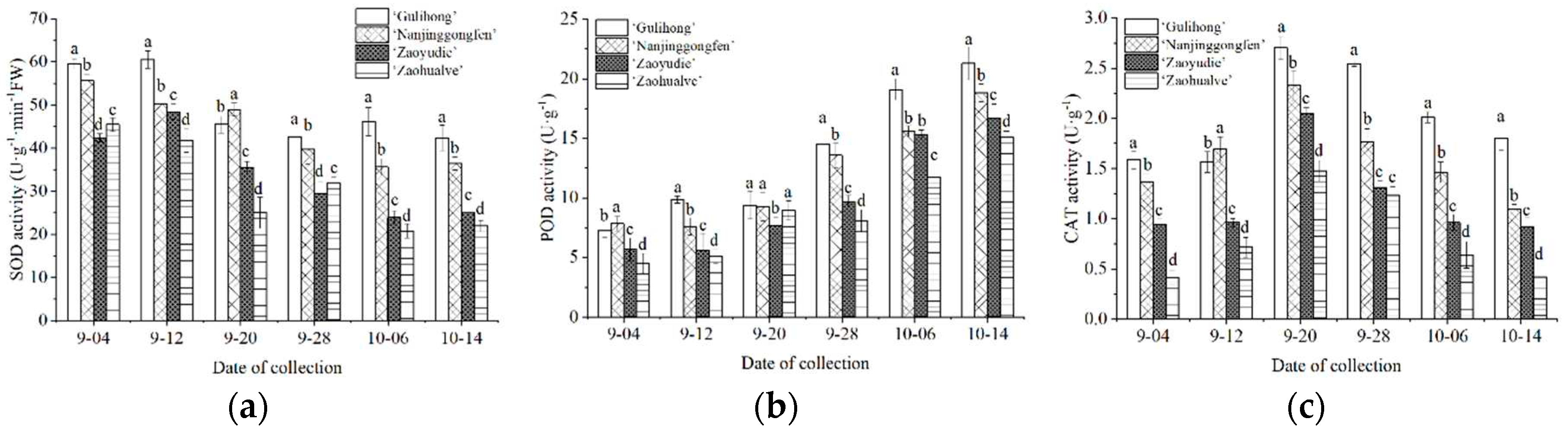

It can be seen from

Figure 4 that the activities of various antioxidant enzymes in FBs of different cultivars changed during dormancy. The trends of dynamic changes of enzyme activities in FB dormancy period, of each variety, are similar during the period of low-temperature release dormancy. The SOD activity was higher at the initial stage of low-temperature storage, and then gradually decreased and maintained at a low level. With the accumulation of cold, the POD activity showed an upward trend. The activity of CAT in the FB of each cultivar generally showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing during low-temperature storage. In addition, in the process of artificial low-temperature breaking dormancy, the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the FBs of ‘Gulihong’, which requires a higher amount of chilling is higher than that of other cultivars, and the antioxidant enzymes activity of ‘Zaohualve’ is the lowest.

The results indicated that, in contrast to the control group which did not generate active oxygen stress response, the enzyme activities of FBs from different cultivars showed variations during the process of artificial low-temperature treatment for dormancy release. The cultivars with higher CR demonstrated a stronger ability to scavenge free radicals and avoid the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in FBs.

3.2.3. The Effect of Low-Temperature on the Content Changes of Endogenous Hormones in FBs during the Release of Dormancy

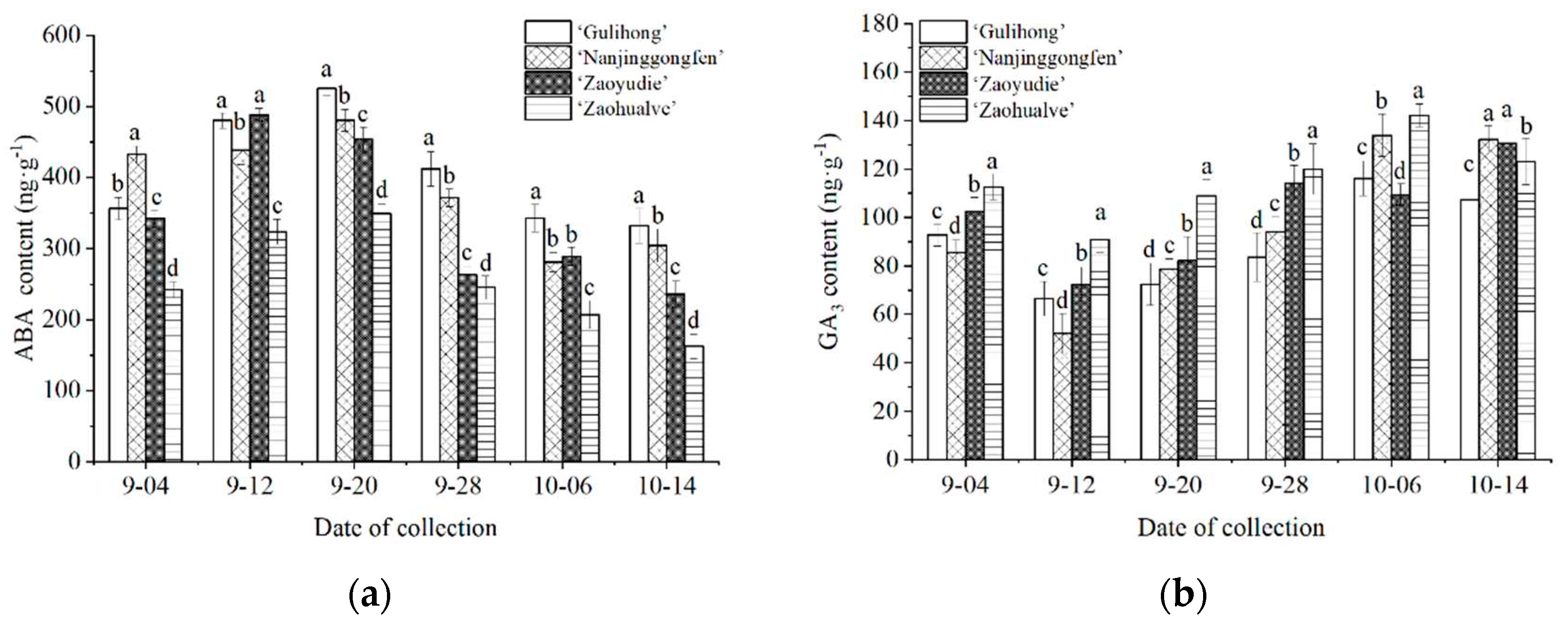

The changes of ABA and GA

3 content in FBs of different cultivars during the period of dormancy can be seen from

Figure 5. The content of GA

3 in the FBs of each cultivar was high before entering the cold storage, and after the initial low-temperature stress, the overall content showed a downward trend; while, the ABA content gradually increased; when the dormancy was gradually released, the GA

3 content gradually increased, and the ABA content decreased. In addition, during the process of breaking dormancy at low-temperature, the GA

3 content of cultivars with lower CRs were significantly higher than others. The ABA content in FBs of ‘Gulihong’ with higher CR was higher than that of other cultivars with lower CR.

Based on the experimental results, it can be concluded that low-temperature caused changes in endogenous hormone levels during dormancy. In contrast, FBs in the control group that were not subjected to low-temperature treatment did not experience any stress response, which resulted in the failure of the FBs to germinate. During the process of artificially inducing low temperatures to break dormancy, FBs of cultivars that require less CR showed lower levels of ABA content compared to other cultivars. This lower level of ABA content promoted the production of GA3, which facilitated earlier germination of FBs and ultimately resulted in earlier flowering.

4. Discussion

4.1. Chilling Requirement

Low-temperature is an important environmental factor that induces the initiation and release of dormancy in plant buds. Parkes (2020) has produced a collection of CRs for eight apple cultivars (

Malus domestica) in chill units during the autumn and winter of 2014 and 2015. The results showed that the range of CRs measured for Utah models was 976 ± 40.3 to 1307 ± 86.6 CU [

24]. Li et al. (2019) based on the Utah model and the 7.2°C model, determined that the CRs of

Chimonanthus praecox (L.) Link (Calycanthaceae) cultivars ‘Suxin’ and ‘Qingkou’ were 558 CU and 570 CU, respectively, under natural conditions [

25].

P. mume cultivars ‘Nanko’ and ‘Ellching’, from temperate Japan and subtropical Taiwan, require 500 and 300 chilling hours, respectively, to break FB dormancy [

26]. In this research, through the artificial low-temperature treatment, the CR of these cultivars were obtained. Among them, ‘Gulihong’ had the highest CR of 408 CU; while ‘Zaohualve’ had the lowest CR of 348 CU. Through these data, we can infer that there are obvious differences in the CRs and dormancy states of different

P. mume. The CR of each cultivar was different from ‘Mei Fan’ [

15], ‘Li Mei’ [

27] and others. It can be seen that different species and different cultivars of the same species have different CRs. It is determined, which to a certain extent will affect whether the plant blooms normally or not, and the time of the flowering period. Moreover, the germination rate of each cultivar gradually increased with the increase of low-temperature treatment time, and the dormant state of FBs was effectively released after a certain period of treatment. However, without artificial low-temperature treatment, none of the FBs of the control groups germinated all the time. In this research, compared with the natural flowering period of

P. mume blossoms from February to April, the flowering period of each cultivar was advanced to mid-November under artificial intervention. Therefore, CR is the main factor of the dormancy release. Mastering the amount of CR can effectively control the flowering period.

4.2. Carbohydrates

During bud dormancy release, reserve carbohydrates play a critical role as they serve as the primary source of carbon and energy [

28]. Moreover, SS and ST are known to function as signaling molecules in plant development regulation [

29,

30]. In order to resist the invasion of low-temperature, a large amount of carbohydrates are stored in plants to provide the basic substances required for dormancy consumption and sprouting growth [

31]. This research found that, although the SS content in nectarine FBs in the early stage of dormancy was low, it showed a rising trend throughout the dormancy process, and it rose sharply in the late stage of dormancy; the change of ST content began to increase slowly in the early stage. After the accumulation reached its peak, it began to decline in the late dormancy period. The conclusion of this research is consistent with previous research results on Peach [

32] and Peonia [

33], which can further explain that the effect of low-temperature would increase starch hydrolysis and consequently sugar contents. The degradation of starch during natural dormancy is the reason for the increase of soluble sugar content, and the degradation of starch is related to the release of dormancy. Furthermore, prior to the dormancy breaking, it was observed that the SS content of the cultivars requiring less CR was higher. This can be attributed to the fact that these cultivars respond more quickly to low-temperatures due to their lower CR. Moreover, a higher SS content is beneficial for the release of dormancy.

4.3. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

In the process of relieving the dormancy period, the activities of antioxidant enzymes will change. Plants will generate a higher level of oxidative stress at low-temperature, which will lead to an increase in the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cells, thereby damaging the biological macromolecular structures such as plant cell DNA, membrane lipids, and proteins. In order to protect cells from damage caused by oxidative stress, the activities of antioxidant enzymes in the plant ROS metabolic pathway are activated to counteract the effects of ROS [

33]. Hernández (2021) studied the antioxidant metabolism during bud dormancy release in a low chill peach variety. They found that the presence of H

2O

2-sensitive antioxidant enzymes in the floral buds could trigger the oxidative signaling leading to dormancy release [

35]. The results of this research showed that the activity of SOD in FBs of each cultivar gradually decreased with the accumulation of cold; the trend of POD activity was opposite to that of SOD activity, and the trend of CAT activity first increased and then decreased. Furthermore, the study also revealed that during the artificial low-temperature dormancy breaking process, the enzyme activity of ‘Gulihong’ was notably higher than that of the other cultivars. This suggests that cultivars with a higher CR have a stronger ability to scavenge free radicals and prevent the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in their FBs. Moreover, our results agree with a recent work in high-chill peach variety [

35], It can be seen that different plant species have different changes in antioxidant enzyme activity during the dormancy period, which is different from the genome and metabolic pathways among tree species, which may lead to their different responses to environmental stress and oxidative stress during dormancy. Factors such as different environmental pressures, light and temperature may also affect the regulation of enzyme activity, resulting in different enzyme activity changes in FBs of different plants [

36]. Therefore, more studies are needed to understand the enzyme activity changes in FBs of different tree species during dormancy to further understand the molecular mechanism of plant dormancy.

4.4. Endogenous Hormone

Endogenous hormones also play an important role in the process of inducing and maintaining FB dormancy in plants [

17]. ABA is a type of plant hormone that has been widely recognized as a powerful growth inhibitor. While GA

3 is known to act as an antagonist to ABA, which in turn promotes the process of germination [

37]. Two core hormones regulate bud dormancy status antagonistically [

38]. In

P. mume, the ABA/GA ratio was reported to steadily decline during the dormancy release process [

39,

40]. In this research, during the low-temperature release period, the ABA content increased and reached the peak before the release of dormancy, and its content showed a downward trend with the passage of time and the accumulation of cold. The change of GA

3 content was the opposite. After 32 days of low-temperature storage, its content reached the maximum and remained at a relatively high level on the whole, indicating that GA

3 is the main hormone-like factor that promotes the release of dormancy. It is important for FB germination and dormancy induction. It has a certain promoting effect. In addition, in the process of breaking dormancy at artificial low-temperature, ‘Gulihong’ with higher CRs had higher ABA content and lower GA

3; while the cultivars with lower CRs were the opposite. The result agrees with the conclusions of Wen [

39]. It can be seen that cultivar with lower CR has lower ABA concentrations and higher GA

3 concentrations, which showed early bud burst. High CRs and the late germination of FBs may be related to high ABA content and low IAA content.

5. Conclusions

The research results have important significance for P. mume cultivation. In this research, based on the method of artificial low-temperature to relieve dormancy, under the condition of artificially controlling the low-temperature of 6°C, The CRs of ‘Gulihong’, ‘Nanjing gongfen’, ‘Zaoyudie’ and ‘Zaohualve’ were 408CU, 396CU, 372CU and 348CU, respectively. This research has wide application value in horticulture and agriculture. In horticulture, based on the way of artificial low-temperature to relieve dormancy in this study, mastering the amount of chilling requirement by different cultivars can determine when to take chilling measures according to the specific viewing time, which provides a reference for accurately controlling the flower supply time of major festivals and major horticultural expositions. In agriculture, this study achieves the goal of early flowering of P. mume, which will help to increase yield and promote the development of P. mume industry.

In addition, the research found that the process of relieving dormancy at low-temperature is closely related to the content of osmotic regulators, antioxidant enzyme systems, and endogenous hormones in FBs. The content of different cultivars that require chilling is also different. We can use the change of its content as an indicator to judge the dormant process. By measuring the growth and physiological indicators, this study can further explore the physiological mechanism of FBs during the period of low-temperature release dormancy, as well as the internal relationship between the amount of chilling requirement, the time of FB germination and the physiological changes in the FB, and provide a theory for the forcing cultivation technology of P. mume.

In the future, the dormancy mechanism of P. mume with different CRs can be further analyzed from the molecular levels such as transcriptome and metabolome, so as to provide a more scientific basis for P. mume cultivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Q and M.K.; methodology, Z.Y.; software, Z.Y.; validation, Z.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Y.; investigation, Z.Y.; resources, L.Q and M.K.; data curation, Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, L.Q and M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, L.Q and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program (2020YFD1000500) sub-project “Integration and Demonstration of Light, Simple and Efficient Cultivation Technology for Prunus mume” (2020YFD100050201).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hao R, Du D, Wang T, et al. A comparative analysis of characteristic floral scent compounds in Prunus mume and related species[J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2014, 78(10): 1640-1647.

- Bergstrand K J I. Methods for growth regulation of greenhouse produced ornamental pot-and bedding plants–a current review[J]. Folia Horticulturae, 2017, 29(1): 63-74.

- Faust, M., Erez, A., Rowland, L. J., Wang, S. Y., Norman, H. A. Bud dormancy in perennial fruit trees: physiological basis for dormancy induction, mainte-nance, and release. HortScience, 1997, 32(4), 623-629. [CrossRef]

- Angevine M W, Chabot B F. Seed germination syndromes in higher plants[M]//Topics in plant population biology. Palgrave, Lon-don, 1979: 188-206.

- Moe R. Factors affecting flower abortion and malformation in roses[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 1971, 24(2): 291-300.

- Darbyshire R, Webb L, Goodwin I, et al. Winter chilling trends for deciduous fruit trees in Australia[J]. Agricultural and forest meteorology, 2011, 151(8): 1074-1085.

- Weinberger J H. Chilling requirements of peach cultivars[C]//Proceedings. American Society for Horticultural Science. 1950, 56: 122-28.

- Richardson E A, Seeley S D, Walker D R, et al. Pheno-climatography of spring peach bud development [J]. HortScience, 1975, 10(3): 236-237.

- Fishman S, Erez A, Couvillon G A. The temperature dependence of dormancy breaking in plants: computer simulation of pro-cesses studied under controlled temperatures[J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1987, 126(3): 309-321.

- Erez A. Bud dormancy; phenomenon, problems and solutions in the tropics and subtropics[J]. Temperate fruit crops in warm cli-mates, 2000: 17-48.

- Erez A, Couvillon G A. Characterization of the influence of moderate temperatures on rest completion in peach[J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 1987, 112(4): 677-680.

- Erez A, Couvillon G A, Hendershott C H. The effect of cycle length on chilling negation by high temperatures in dormant peach leaf buds [J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 1979, 104(4): 573-576.

- Ou S. Chilling requirement of local mume trees in Taiwan [J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University. 1999(02): 73-77.

- Zhuang W, Zhang Z, Shi T, Wang P, Shao J, Luo, X, Gao Z. Advance on chilling requirement and its chilling models in deciduous fruit crops [J]. Journal of Fruit Science,2012,29(3):447-453.

- Yang Y, Li Q. Chilling requirement of Prunus mume cultivars.[J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University. 2013, 35(S1): 47-51.

- Gao Z, Zhuang W, Wang L, et al. Evaluation of chilling and heat requirements in Japanese apricot with three models[J]. HortScience, 2012, 47(12): 1826-1831.

- Cooke J E K, Eriksson M E, Junttila O. The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms[J]. Plant, cell & environment, 2012, 35(10): 1707-1728.

- Sagisaka S, Araki T. Amino acid pools in perennial plants at the wintering stage and at the beginning of growth[J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 1983, 24(3): 479-494.

- Karssen C M, Brinkhorst-Van der Swan D L C, Breekland A E, et al. Induction of dormancy during seed development by endoge-nous abscisic acid: studies on abscisic acid deficient genotypes of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh[J]. Planta, 1983, 157(2): 158-165.

- Lang A. The effect of gibberellin upon flower formation[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1957, 43(8): 709-717.

- Wang L, Hu N. Chilling requirement of Peach cultivars. [J]. Journal of Fruit Science. 1992(01): 39-42.

- Li H. Modern Plant Physiology - 3rd Edition. Publisher: Higher Education Press, China, 2012.

- Gao J. Plant Physiology guide (paperback). Publisher: Higher Education Press, China, 2006.

- Parkes H, Darbyshire R, White N. Chilling requirements of apple cultivars grown in mild Australian winter conditions[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2020, 260: 108858.

- Li Z, Liu N, Zhang W, et al. Integrated transcriptome and proteome analysis provides insight into chilling-induced dormancy breaking in Chimonanthus praecox[J]. Horticulture Research, 2020, 7.

- Yamane H, Kashiwa Y, Kakehi E, et al. Differential expression of dehydrin in flower buds of two Japanese apricot cultivars re-quiring different chilling requirements for bud break[J]. Tree physiology, 2006, 26(12): 1559-1563.

- Wang, X.Y., H.L. He, G.S. Liang, and C.X. Zhao. Study on the dormancy of mume cultivars in southern subtropical area of Chi-na[J]. Journal of Fruit Science, 2007.

- Chao W S, Serpe M D. Changes in the expression of carbohydrate metabolism genes during three phases of bud dormancy in leafy spurge[J]. Plant molecular biology, 2010, 73: 227-239.

- Saddhe A A, Manuka R, Penna S. Plant sugars: Homeostasis and transport under abiotic stress in plants[J]. Physiologia plantarum, 2021, 171(4): 739-755.

- Gibson S I. Control of plant development and gene expression by sugar signaling[J]. Current opinion in plant biology, 2005, 8(1): 93-102.

- Bonhomme M, Rageau R, Lacointe A, et al. Influences of cold deprivation during dormancy on carbohydrate contents of vegetative and floral primordia and nearby structures of peach buds (Prunus persica L. Batch)[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2005, 105(2): 223-240. [CrossRef]

- Hernández J A, Díaz-Vivancos P, Acosta-Motos J R, et al. Interplay among antioxidant system, hormone profile and carbohydrate metabolism during bud dormancy breaking in a high-chill peach variety[J]. Antioxidants, 2021, 10(4): 560.

- Walton E F, Boldingh H L, McLaren G F, et al. The dynamics of starch and sugar utilisation in cut peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) stems during storage and vase life[J]. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2010, 58(2): 142-146. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad P, Sarwat M, Sharma S. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants and signaling in plants[J]. Journal of Plant Biology, 2008, 51: 167-173.

- Hernández J A, Díaz-Vivancos P, Martínez-Sánchez G, et al. Physiological and biochemical characterization of bud dormancy: Evolution of carbohydrate and antioxidant metabolisms and hormonal profile in a low chill peach variety[J]. Scientia Horticul-turae, 2021, 281: 109957.

- Źróbek-Sokolnik A. Temperature stress and responses of plants[J]. Environmental adaptations and stress tolerance of plants in the era of climate change, 2012: 113-134.

- Gubler F, Millar A A, Jacobsen J V. Dormancy release, ABA and pre-harvest sprouting[J]. Current opinion in plant biology, 2005, 8(2): 183-187.

- Schrader J, Moyle R, Bhalerao R, et al. Cambial meristem dormancy in trees involves extensive remodelling of the transcriptome[J]. The Plant Journal, 2004, 40(2): 173-187.

- Wen L H, Zhong W J, Huo X M, et al. Expression analysis of ABA-and GA-related genes during four stages of bud dormancy in Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc) [J]. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 2016, 91(4): 362-369.

- Zhang Z, Zhuo X, Zhao K, et al. Transcriptome profiles reveal the crucial roles of hormone and sugar in the bud dormancy of Prunus mume [J]. Scientific reports, 2018, 8(1): 1-15.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).