INTRODUCTION

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is a heart disease with a genetic basis, defined by the progressive replacement of the ventricular myocardium with fibroadipose tissue, which can act as a substrate for arrhythmias, sudden death (SD), or even give rise to heart failure (HF). Estimates place the prevalence of ACM among the general population at 1:3.000-5.000 inhabitants. It generally presents between the ages of 20 and 40 years, and usually manifests in the form of palpitations, syncope or presyncope, with SD often the first manifestation of the disease, particularly in the case of young patients1,2.

Despite classically having been described as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), frequent biventricular or predominant left ventricle involvement have led to adoption of the term ACM3. Both the biventricular and the predominant left ventricular forms can be difficult to differentiate from dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) 3,4.

Complex molecular mechanisms exist in the physiopathology of ACM that differ according to the genotype5, 6. Classically, ACM has been considered a disease of autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance and variable clinical expressivity depending on age, caused by mutation in the genes that encode desmosomal proteins 7,8. There are five genes that encode these proteins and are involved in the pathogenesis of ACM: plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmocollin-2 (DSC2) and junction plakoglobin (JUP). The literature also describes certain, much less frequent, forms with autosomal recessive transmission, which are usually syndromic 9. Approximately 40-60% of cases with a definitive ACM diagnosis show at least one genetic variant that could explain the disease 10, for the most part in a desmosomal gene, although in a low percentage of cases it is possible to identify causal variants in non-desmosomal genes (DES, PLN, TMEM43, LMNA, TTN, SCN5A, CTNNA3, CDH2, TJP1, ANK2, TP63)11. Recent years have seen numerous cases of ACM described as oligogenic, or even mulitifactorial, with genomic and atmospheric factors playing a role in pathogenesis10,11.

The clinical diagnosis of ACM is not an easy task, given that it shares characteristics with many other diseases such as DCM, myocarditis, sarcoidosis and some variations of normality such as athletic heart syndrome12. Genetic diagnosis is also complex, due to the high predominance of variants that are missense-type or of uncertain significance in desmosomal genes, particularly in PKP213, which means that interpretation of the genetic study must be undertaken in conjunction with clinical data and a familial study to establish the presence or not of cosegregation. Thus, the 2010 revised diagnostic criteria for ACM included genetic criteria14.

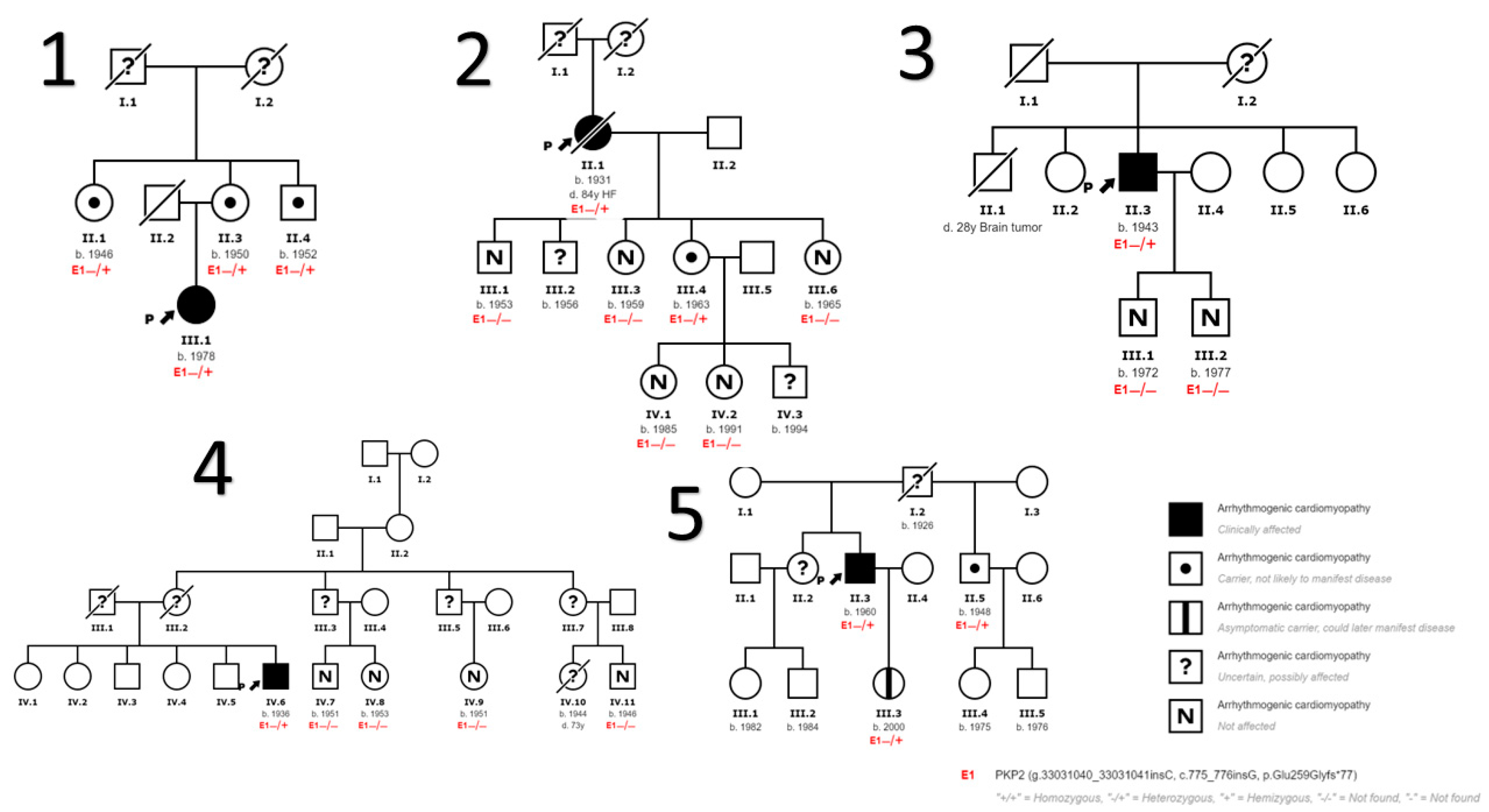

The aim of our study is to describe the clinical, genetic, and epidemiological characteristics of eight initially non-interrelated families who have a diagnosis of ACM associated with the NM_004572.3:c.775_776insG; p. (Glu259Glyfs*77) variant in the PKP2 gene. This variant has not previously been described, and we can confirm its pathogenicity, establishing a founder effect in our region in Malaga (Andalusia, Spain) that allows us to evaluate the genotype-phenotype correlation and describe the clinical and risk characteristics of both index cases and family members in follow-up at our HF and Familial Cardiomyopathies Unit.

METHODS

Study design and population

This is a descriptive observational study that included 8 families with a diagnosis of ACM related with the genetic variant NM_004572.3:c.775_776insG; p. (Glu259Glyfs*77) in gene PKP2 who underwent follow-up at our HF and Familial Cardiomyopathies Unit. We evaluated 8 probands, or index cases, who had undergone genetic testing as part of the habitual study of their heart disease. We also included 39 family members of these index cases, performing cascade testing. We broadened the initial evaluation to include further tests in cases of suspicion or indications of disease. The informed consent of each subject was obtained, and the study protocol met the ethical criteria of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

The definitive diagnosis of ACM followed the 2010 modified Task Force criteria14. We compiled personal and family histories, demographic and clinical characteristics, additional tests at the time of diagnosis, and arrhythmic events both at diagnosis and during follow-up.

Genetic analysis

The study of the index cases of each family was performed by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) using a library that included 121 genes related to ACM and DCM as a part of the habitual clinical evaluation. The genes included in this test were selected based on clinical criteria, taking into account their association with a given phenotype (among them, we highlight ACTA1, BAG3, BRAF, DES, DMD, DSC2, DSG2, DSP, EMD, FHOD3, FLNC, GLA, JUP, KCNJ2, LMNA, MYBPC3, MYH6, MYH7, PKP2, PLN, RBM20, RYR2, SCN5A, TMEM43, TTN, TTR). In addition, the method is combined with the Sanger technique for those regions with suboptimal coverage and/or quality levels, which are re-sequenced using this technique. By this method it is possible to identify point substitutions and small insertions/deletions of up to 20 nucleotides with a sensitivity and specificity of the method higher than 99%.

For the study of the PKP2 variant in family members, we used the Sanger method, sequencing only the variant under study. We obtained the blood samples used for the genetic testing after receiving signed informed consent from each subject. The pathogenicity of the genetic variants was classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics15.

Clinical evaluation and follow-up

For all index cases identified, we exhaustively researched the family history, and prepared a family tree covering at least 3 generations, which allowed us to carry out the cascade familial screening of all accessible family members. All subjects received a clinical evaluation that included a personal and family history, a physical examination, a 12-lead ECG, and a transthoracic echocardiogram. The 24-hour Holter monitoring and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) were only undertaken for the index cases and for family members who were affected or had suspected incipient disease, provided no contraindications existed for the study (claustrophobia or wearers of impantable cardiac desfibrilator -ICD- or other devices). The clinical information was retrospectively recorded for patients who had a previous diagnosis, and prospectively for new cases or evaluated family members.

Thus, we identified, treated and established follow-up for all carrier subjects of the NM_004572.3:c.775_776insG; p. (Glu259Glyfs*77) variant, in accordance with the latest evidence available for ACM and DCM16,17.

During follow-up, we collected information on arrhythmic events, including sustained ventricular tachycardia (SVT) and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), appropriate ICD therapies (with anti-tachycardia therapy or shock) and aborted SD. We also considered the development of heart failure (HF), the need for heart transplant, and death.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS (version 22) to analyse the data. Quantitative variables are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation or as a median and interquartile range according to whether they followed a normal distribution or not. Categorical variables are expressed as an absolute value and a percentage. For comparison of continuous variables, we used Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for normal or non-normal distribution respectively. Categorical variables are compared by means of contingency tables and the x2 test or Fisher's exact test. Two-tailed values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the sample

Of the 47 subjects studied, 8 were index cases or probands (17% of the sample) who met the diagnostic criteria for ACM and were carriers of the NM_004572.3:c.775_776insG; p. (Glu259Glyfs*77) variant in gene PKP2. The 39 family members evaluated underwent a targeted genetic study for the variant, and 16 (34%) were found to be carriers, 3 of whom (6.4%) were also affected by heart disease: one subject with incipient involvement, whose study it was not possible to complete due to exitus for gastric cancer; another patient with a phenotype overlapped with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and with a complex genotype, who was additionally a carrier of pathogenic variants in sarcomeric genes; and another patient with incipient DCM.

Most of the subjects evaluated were women (26 patients: 55.3%), with a mean age on diagnosis of 48.9 ± 18.6 years. The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 64% [60-65] and the follow-up period was 39 [24-59] months.

Table 1A describes the baseline characteristics of the sample, and table 1B illustrates the main clinical characteristics of the subjects who are carriers of the genetic variants and were diagnosed of ACM (11 subjects, 17.2% of the sample). Among this group, in most cases, presentation of the disease was for arrhythmic events: 4 (36.3%) patients with VT, 1 (9.1%) with aborted SD and another (9.1%) for palpitations caused by high-density ventricular ectopic beats. In addition, 3 (27.2%) of the diagnoses were made for symptoms of HF and another 2 (18.2%) on conducting the familial studies. Right ventricular involvement was the most common (4 patients, 36.3%), alongside biventricular involvement (4 patients, 36.3%), and only 3 patients (27.2%) had exclusive left involvement. None of the subject with right involvement had a right ventricular dysfunction that was greater than mild, and right involvement was considered for segmental hypokinesia.

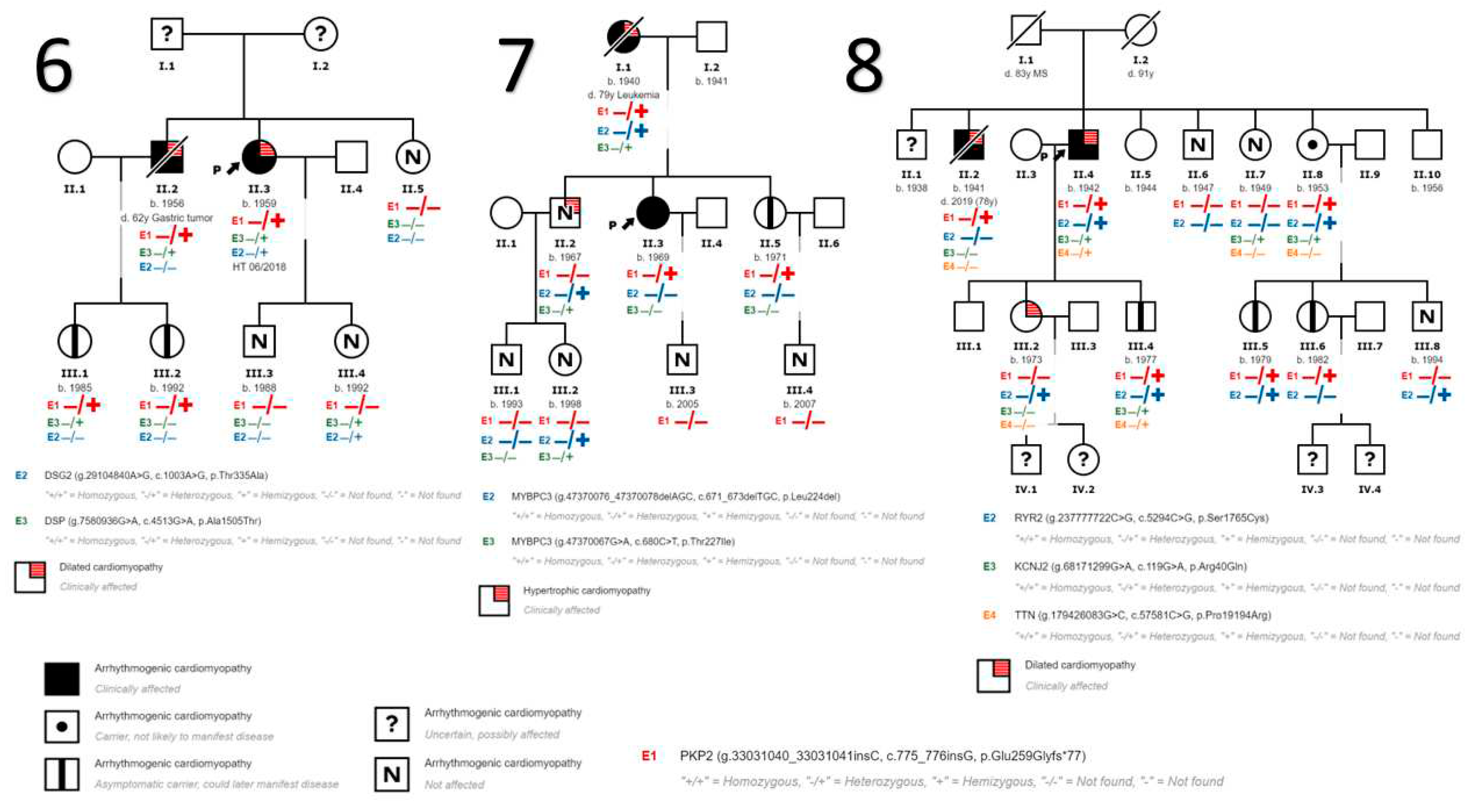

We also detected variants in genes other than PKP2 in 9 patients. In the first 5 families (

Figure 1) no other variants in other genes have been identified. In family 6 (

Figure 2) we identified a variant in DSG2 gene that has been described to be associated with the development of ACM in homozygosis or compound heterozygosis, being highly probable that it contributes to the development of ACM in the presence of another pathogenic variant as is our case in PKP2 and more specifically in the index case of this family. In addition, we found another variant in DSP gene considered to be of uncertain pathogenicity, and a more extensive cosegregation study is necessary. In family 7 (

Figure 2) 2 variants in the gene that encodes myosin binding protein C3 (MYBPC3) have been found to be associated with the development of HCM, unrelated to DCM and/or ACM. In this family, the HCM phenotype is only evident in patients carrying these variants in MYBPC3. In Family 8 (

Figure 2) we have found variants of unknown pathogenicity in the inward-rectifier potassium channel gene (KCNJ2) and titin gene (TTN); and another variant in the ryanodine receptor 2 gene (RYR2) which, although also considered of unknown pathogenicity, could contribute to the ventricular arrhythmia phenotype in the presence of other disease-causing variants such as the PKP2 variant.

Table 2 describes the genetic and clinical characteristics of the subjects diagnosed with ACM.

It should be highlighted that of the 47 patients studied, only 10 (21.3%) underwent CMRI, and only one person had positive late gadolinium enhancement. In most cases, the reason that CMRI was not possible was claustrophobia.

Follow-up

During the mean follow-up period of 48 [27-59] months for the patients who were carriers of the described genetic variant, 5 patients (20.9%) suffered arrhythmic events, 4 (16.7%) as SVT and 1 (4.2%) as NSVT. Only 2 patients (8.3%) underwent an ablation procedure for VT; and 8 patients (33.3%) had an ICD implant, 4 (16.7%) as primary prevention and the other 4 (16.7%) as secondary prevention (2 subjects with right-involvement and the other two with biventricular involvement). Regarding ICD therapies, 2 patients (8.3%) received appropriate therapies for SVT during follow-up.

The onset of HF occurred in 6 patients (25%), one of whom eventually required a heart transplant with a good subsequent progression.

We did not find any statistically significant differences between the sexes regarding events during follow-up (

Table 1B). Neither were there any differences for LVEF between the sexes (63% [40-65] among men and 64% [60-65] in women, p= 0.68), although we did find a statistical significance for age on diagnosis, which was lower for women (48.4 ± 17.3 years, p 0.03).

During follow-up, 4 patients died, one of them due to HF and three others not directly related to ACM: in 2 cases it was due to oncological processes (gastric cancer and leukaemia) and the third was multifactorial in an elderly patient.

DISCUSSION

PKP2 encodes plakophilin-2, the protein that localizes to desmosomes and nuclei, and is involved in regulation of cellular signalling and in cell-cell junctions through intermediate filaments in the cytoskeleton. It is expressed in various tissues, including the myocardium, and high levels of this protein are detected in the RV. The intention of this study is to describe our carrier population of the NM_004572.3:c.775_776insG; p. (Glu259Glyfs*77) variant in PKP2, which has been identified among 8 families of our geographical area in Malaga (Andalusia, Spain) who were initially non-interrelated but for whom we can establish a founder effect. This variant has not previously been described or reported in the databases used as population control (Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes Project, ExAC, etc.). It is also a radical variant provoking truncation in the protein, which causes functional deficit and/or premature degradation. Radical variants (nonsense, frameshift and splicing) are considered clearly pathogenic15 as they cause a premature stop codon and are most frequently associated with the pathogenesis of ACM, although deletions and duplications have also been identified as the cause of the phenotype.

Pathogenic variants in PKP2 are one of the most frequent causes of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, and research suggests that such variants are responsible for between 30-50% of all ACM cases, although there is disparity between the different studies, probably due to geographical distribution 18, 19. Some series have found mutations of this gene in up to 70% of patients with a family history, above all in the Netherlands 18 with proportions that are higher than other registries for other parts of the world20.

As in our sample, the incidence of desmosomal mutations described in the different published series varies between 30% to 60%10,21,22. The work of Ruiz-Salas et al.23 indicates a higher incidence, most likely due to the selection of the sample, all of whom had received a definitive diagnosis of ACM. Likewise, the Medeiros-Domingo et al.24 paper detected a higher percentage of mutation in desmosomal genes among patients with definitive RVACM compared to borderline or possible RVACM, who additionally had other variants in genes associated with ACM, the supposition was that this could consist of overlapped ACM and DCM or phenocopies.

Our research reports a previously undescribed genetic variant that also has a founder effect in our geographical area. The description of new mutations in ACM registries is not always specified, and as many as 25%-70% of all of the pathogenic variants reported in the main series have not been previously described25,26,. As we have already mentioned, there is wide geographic variability in the distribution of PKP2 mutations18 with multiple founder mutations described in areas such as the Netherlandsc27. These data support the suspicion that the genetic spectrum of ACM may have singularities in each geographical zone and that large-scale registries and studies are necessary to establish the genotype-phenotype relationship.

Our series seems to suggest incomplete penetrance, with most of the affected carriers over the age of 55 years. Although this variant is sufficient to cause presentation of the disease, our cases with a phenotype at an earlier age are usually women or cases in which a second impact exists, such as the presence of another pathogenic genetic variant or participation in sports activities. Thus, our data concur with others described in the literature, with a variable expressivity of the disease among patients with PKP2 mutations, with some very severe forms and others that are milder within the same family, with incomplete penetrance, depending on age, but differing in terms of sex, as these earlier and more severe cases have normally been described in males28.

In most cases of ACM associated with PKP2 mutations, right involvement predominates, and predominantly left forms, or those diagnosed as DCM, are rarer, although some reports suggest that the possibility of left involvement may be as high as 60% of carriers of pathogenic mutations in PKP229. The previously cited Ruiz-Salas et al. study 23 found an association between PKP2 mutations and cases of exclusively right ventricle involvement, whereas mutations in DSP correlated with predominantly left ventricle involvement. Different series, such as that of Bhonsale et al.30, have also observed the same results; likewise our series found the most frequent ventricular involvement to be either right or biventricular (16.7% in both cases).

The phenotype of these patients is characterised by presentation with ventricular arrhythmia, generally from youth31, and several studies report an association between the presence of these mutations with a higher likelihood of arrhythmic events and presentation of the disease at an earlier age in comparison to patients with a negative genetic study, as occurred in the den Haan et al. series 24,25, which detected more VT events and an earlier age of diagnosis for carrier patients (73% versus 44%, and 33 versus 41 years). In our research, we found a high rate of arrhythmic events as the form of presentation (25.1%) and in follow-up (20.9%), in addition to appropriate ICD therapies and the need for ablation for VT (8.3% respectively), taking into account that this is a very select group, as occurred in the Ruiz-Salas et al. series 22, where the most frequent presentation of the disease was with arrhythmic events; 86% of the sample presented an arrhythmic episode throughout their lives. However, Bhonsale et al.29, who published the largest series of RVACM genetic mutation carrier patients, did not find a worse arrhythmic profile or worse prognosis than for non-carriers, which could be attributable to the different profile of their sample with only 60% definitive RVACM. Among our series, the high rate of HF during follow-up (25%) is notable, despite the fact that this phenotype has more frequently been described in cases of ACM with mutations in genes DSG2 and DSP, with predominantly left involvement30.

One of the challenges currently facing cardiology remains the prognosis and risk stratification for sudden death in ACM 16, as there is a considerable lack of coherence between the factors associated with a greater risk of SD and/or ventricular arrhythmias in the studies and series of published cases. What has been generally reported is a lower incidence of ventricular arrhythmia among family members diagnosed during the familial screening in comparison with the index cases, as also occurs in our series, although recent studies appear to cast doubt on this 32

Our research also seeks to highlight the importance of genetics in the study of cardiomyopathies and in particular of ACM, since not only does it allow us to confirm diagnosis, and indeed is one of the diagnostic criteria of the Task Force14, but also to perform a familial screening for early detection of the disease and to establish recommendations for physical activities and work, thus avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests or follow-up among patients with negative genetic testing results. In many cases, it also represents a guide for prognosis, with higher or lower risk of arrhythmias or of HF in some of the genetic mutations identified, as we have already indicated 30. Nevertheless, we should not forget that genetic testing requires suitable interpretation in conjunction with clinical data by specialist personnel, since recent awareness of hereditary diseases and the new sequencing technology available mean that genetic testing is increasingly requested and consequently the number of described variants associated with ACM is higher.

Limitations

This is a descriptive single-centre study, with a small number of patients and no control group, which does not allow extrapolation of the data to all patients who are carriers of PKP2 variants. Moreover, as most of the data used are retrospective, confounders exist that may affect the results.

Another limitation has been that some family members rejected a clinical or genetic study; and for the cases that underwent the study, the request for imaging tests indicated "familial screening for ACM" which may have introduced bias.

In our study, we also refer to penetrance, but many of the subjects diagnosed were asymptomatic and diagnosis was by means of familial screening.

WHAT IS KNOWN?

-ACM is a heart disease defined by the progressive replacement of the right ventricle myocardium with fibroadipose tissue, and may cause arrhythmias, sudden death, and heart failure. Currently, 40–60% of patients have at least one genetic mutation related with the disease.

WHAT IS NEW?

-This study presents a PKP2 variant not previously described or present in the control population and establishes a probable founder effect in our region.

-This variant has incomplete penetrance and a highly variable phenotypic expressivity, is strongly influenced by age, sex, and the presence of other genetic or environmental factors such as sport, characteristics that the majority of desmosomal gene mutations share.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study describes the p.Glu259Glyfs*77 variant in PKP2 gene, previously undescribed and not present among the control groups, which we identified in 8 families of our geographical area in Malaga (Andalusia, Spain) who were initially non-interrelated, and for whom we were able to establish a founder effect in our region. This allowed us to evaluate the genotype-phenotype correlation and describe the clinical and risk characteristics of both the index cases and the family members under follow-up in our HF and ICD Unit.

This variation is a pathogenic mutation associated with ACM; it has incomplete penetrance until advanced ages, and with some male sex-dependent tendency; phenotypic expressivity is extremely variable and heavily influenced by the presence of other genetic or environmental factors, characteristics shared by most mutations in desmosomal genes.

Author Contributions

A. Robles-Mezcua and A Ruíz-Salas have collected and analyzed the data as well as drafted the document. C. Medina-Palomo, M. Robles-Mezcua and A. Díaz Expósito have contributed to the collection and analysis of data. MV. Ortega-Jiménez, JR. Gimeno-Blanes, Jiménez-Navarro M and JM García_Pinilla have reviewed the data collected and its analysis and revised the drafting of the final document.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACM: arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

ARVD: arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia

CMRI: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy

DSC2: desmocollin-2

DSG2: desmoglein-2

DSP: desmoplakin

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

HF: heart failure

ICD: implantable cardiac desfibrilator

JUP: junction plakoglobin

KCNJ2: inward-rectifier potassium

LVEF: Left Ventricular Eyeccion Fraction

MYBPC3: myosin binding protein C3

NGS: next-generation sequencing

NSVT: non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

PKP2: plakophilin-2

RYR2: ryanodine receptor 2

SD: sudden death

SVT: sustained ventricular tachycardia

TTN: titin

References

- 1. Basso C, Corrado D, Thiene G. Cardiovascular causes of sudden death in young individuals including athletes. Cardiol Rev. [CrossRef]

- 2. Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Guiraudon G, et al. Right ventricular dysplasia: A report of 24 adult cases. Circulation. [CrossRef]

- 3. López-Moreno E, Jiménez-Jáimez J, Macías-Ruiz R, Sánchez-Millán PJ, Álvarez-López M, Tercedor-Sánchez L. Clinical Profile of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Involvement. Rev Española Cardiol (English Ed. [CrossRef]

- 4. Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Prasad SK, et al. Left-Dominant Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. An Under-Recognized Clinical Entity. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2187. [CrossRef]

- 5. Austin KM, Trembley MA, Chandler SF, et al. Molecular mechanisms of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol. [CrossRef]

- 6. Corrado D, Basso C, Judge DP. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. [CrossRef]

- 7. Quarta G, Elliott PM. Diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Rev Esp Cardiol. [CrossRef]

- 8. Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, et al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies. Europace, 1109. [CrossRef]

- 9. Protonotarios N, Tsatsopoulou A. Naxos disease and Carvajal syndrome: Cardiocutaneous disorders that highlight the pathogenesis and broaden the spectrum of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Pathol. [CrossRef]

- 10. James CA, Syrris P, Van Tintelen JP, Calkins H. The role of genetics in cardiovascular disease: Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J, 1393. [CrossRef]

- 11. James CA, Jongbloed JDH, Hershberger RE, et al. International Evidence Based Reappraisal of Genes Associated With Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy Using the Clinical Genome Resource Framework. Circ Genomic Precis Med, 0032. [CrossRef]

- 12. Corrado D, Van Tintelen PJ, McKenna WJ, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: Evaluation of the current diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis. Eur Heart J, 1414. [CrossRef]

- 13. Kapplinger JD, Landstrom AP, Salisbury BA, et al. Distinguishing arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia- associated mutations from background genetic noise. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2317. [CrossRef]

- 14. Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Eur Heart J. [CrossRef]

- 15. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. [CrossRef]

- 16. Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Hear Rhythm. [CrossRef]

- 17. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J, 2129. [CrossRef]

- 18. Jacob KA, Noorman M, Cox MGPJ, Groeneweg JA, Hauer RNW, van der Heyden MAG. Geographical distribution of plakophilin-2 mutation prevalence in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Netherlands Hear J. [CrossRef]

- 19. Groeneweg JA, Bhonsale A, James CA, et al. Clinical Presentation, Long-Term Follow-Up, and Outcomes of 1001 Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Patients and Family Members. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. G. , van der Zwaag, P. A., van der Werf, C., van der Smagt, J. J., Noorman, M., Bhuiyan, Z. A., Wiesfeld, A. C., Volders, P. G., van Langen, I. M., Atsma, D. E., Dooijes, D., van den Wijngaard, A., Houweling, A. C., Jongbloed, J. D., Jordaens, L., RNW. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: Pathogenic desmosome mutations in index-patients predict outcome of family screening: Dutch arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy genotype-phenotype follow-up study. Circulation, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 21. van Lint FHM, Murray B, Tichnell C, et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy-Associated Desmosomal Variants Are Rarely De Novo. Circ Genomic Precis Med, 0024. [CrossRef]

- 22. Alcalde M, Campuzano O, Sarquella-Brugada G, et al. Clinical interpretation of genetic variants in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol. [CrossRef]

- 23. Ruiz Salas A, Peña Hernández J, Medina Palomo C, et al. Usefulness of Genetic Study by Next-generation Sequencing in High-risk Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Rev Española Cardiol (English Ed, 1018. [CrossRef]

- 24. Christensen AH, Benn M, Bundgaard H, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Wide spectrum of desmosomal mutations in Danish patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet. [CrossRef]

- 25. Den Haan AD, Tan BY, Zikusoka MN, et al. Comprehensive desmosome mutation analysis in North Americans with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. [CrossRef]

- 26. Fressart V, Duthoit G, Donal E, et al. Desmosomal gene analysis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: Spectrum of mutations and clinical impact in practice. Europace. [CrossRef]

- 27. Van Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation, 1650. [CrossRef]

- 28. Dalal D, James C, Devanagondi R, et al. Penetrance of Mutations in Plakophilin-2 Among Families With Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1424. [CrossRef]

- 29. D, Dalal; LH, Molin; J, Piccini; C, Tichnell; C, James; C, Bomma; K, Prakasa; JA T, FI, Marcus; PJ S, DA, Bluemke; T A, SD, Russell; H C, DP J. Clinical features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in plakophilin-2. Circulation, 1641. [CrossRef]

- 30. A, Bhonsale; JA, Groeneweg; CA J, D, Dooijes; C T, JD, Jongbloed; B M, et al. Impact of genotype on clinical course in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated mutation carriers. Eur Heart J. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J. , Wang, J., Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Fan, X., Sun, K., He, D. S., Marcus, F. I., Zhang, S., Hui, R., & Song L. Correlation of ventricular arrhythmias with genotype in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. [CrossRef]

- 32. Chivulescu M, Lie OH, Popescu BA, et al. High penetrance and similar disease progression in probands and in family members with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J, 1401. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).