Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Alley, W.M. The Palmer drought severity index: limitations and assumptions. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1984, 23, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Driscoll, A.; Heft-Neal, S.; Xue, J.; Burney, J.; Wara, M. The changing risk and burden of wildfire in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2011048118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamud, B.D.; Millington, J.D.; Perry, G.L. Characterizing wildfire regimes in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 4694–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ice, G.G.; Neary, D.G.; Adams, P.W. Effects of wildfire on soils and watershed processes. Journal of Forestry 2004, 102, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Yu, P.; Abramson, M.J.; Johnston, F.H.; Samet, J.M.; Bell, M.L.; Haines, A.; Ebi, K.L.; Li, S.; Guo, Y. Wildfires, global climate change, and human health. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steelman, T.A.; Burke, C.A. Is wildfire policy in the United States sustainable? Journal of Forestry 2007, 105, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolden, C.A. We’re not doing enough prescribed fire in the Western United States to mitigate wildfire risk. Fire 2019, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, E.D.; Keane, R.E.; Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D. Objectives and considerations for wildland fuel treatment in forested ecosystems of the interior western United States. Forest Ecology and Management 2008, 256, 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.C.; Charnley, S.; Pixley, J.T. Polycentric systems for wildfire governance in the Western United States. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Raffuse, S.M.; Brauer, M.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.; Johnston, F.H.; Henderson, S.B. Predicting the minimum height of forest fire smoke within the atmosphere using machine learning and data from the CALIPSO satellite. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 206, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, P.; Morais, A.D.J.R. A data mining approach to predict forest fires using meteorological data. 2007.

- Omernik, J.M. Ecoregions of the conterminous United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 1987, 77, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, R.C.; Fusco, E.; Bradley, B.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Balch, J. Human-related ignitions increase the number of large wildfires across US ecoregions. Fire 2018, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidenshink, J.; Schwind, B.; Brewer, K.; Zhu, Z.L.; Quayle, B.; Howard, S. A project for monitoring trends in burn severity. Fire Ecology 2007, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.C. Spatial wildfire occurrence data for the United States, 1992-2015 [FPA_FOD_20170508]. 2017.

- Alley, W.M. The Palmer drought severity index: limitations and assumptions. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1984, 23, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Wildfires and global change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2021, 19, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestemon, J.P.; Prestemon, J.P. Wildfire ignitions: a review of the science and recommendations for empirical modeling; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2013; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Westerling, A.L.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Cayan, D.R.; Swetnam, T.W. Warming and earlier spring increase western US forest wildfire activity. Science 2006, 313, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, M.; Liu, K. Deep neural networks for global wildfire susceptibility modelling. Ecological Indicators 2021, 127, 107735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, Z., Kumar, J., & Hoffman, F. (2018, November). Wildfire mapping in Interior Alaska using deep neural networks on imbalanced datasets. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW) (pp. 770-778). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Van Le, H., Hoang, D.A., Tran, C.T., Nguyen, P.Q., Hoang, N.D., Amiri, M., ... & Bui, D.T. (2021). A new approach of deep neural computing for spatial prediction of wildfire danger at tropical climate areas. Ecological Informatics, 63, 101300. [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I. Wildfires in grasslands and shrublands: A review of impacts on vegetation, soil, hydrology, and geomorphology. Water 2019, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.M.; Song, W.G.; Ma, J.; Satoh, K. Artificial neural network approach for modeling the impact of population density and weather parameters on forest fire risk. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Romme, W.H. Landscape dynamics in crown fire ecosystems. Landscape ecology 1994, 9, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Dataset | Variables | Source | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate | PRISM | Precipitation, Temperature, Vapor Pressure Deficit (min, max) | https://prism.oregonstate.edu/ | 4000 m gridded, Monthly |

| GRIDMET | PDSI, PET | https://www.climatologylab.org/gridmet.html | 4000 m gridded, 5-day (PDSI), 1-day (PET) | |

| Land Cover | National Land Cover Database (NLCD), 2016 | Open Water, Developed, Barren, Forests, Shrub/Scrub, Hay/Pasture, Cultivated Crops, Wetlands | https://www.mrlc.gov/ | 30 m gridded |

| MODIS | MOD13A3 Version 6 | NDVI, EVI | https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13a3v006/ | 1000 m gridded, Monthly |

| Topography | USGS DEM | Elevation (m) | https://earthworks.stanford.edu/catalog/stanford-zz186ss2071 | 100 m gridded |

| Ecoregion Boundaries | US EPA Ecoregions | Level I and Level IV Ecoregions | https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions | Shapefile |

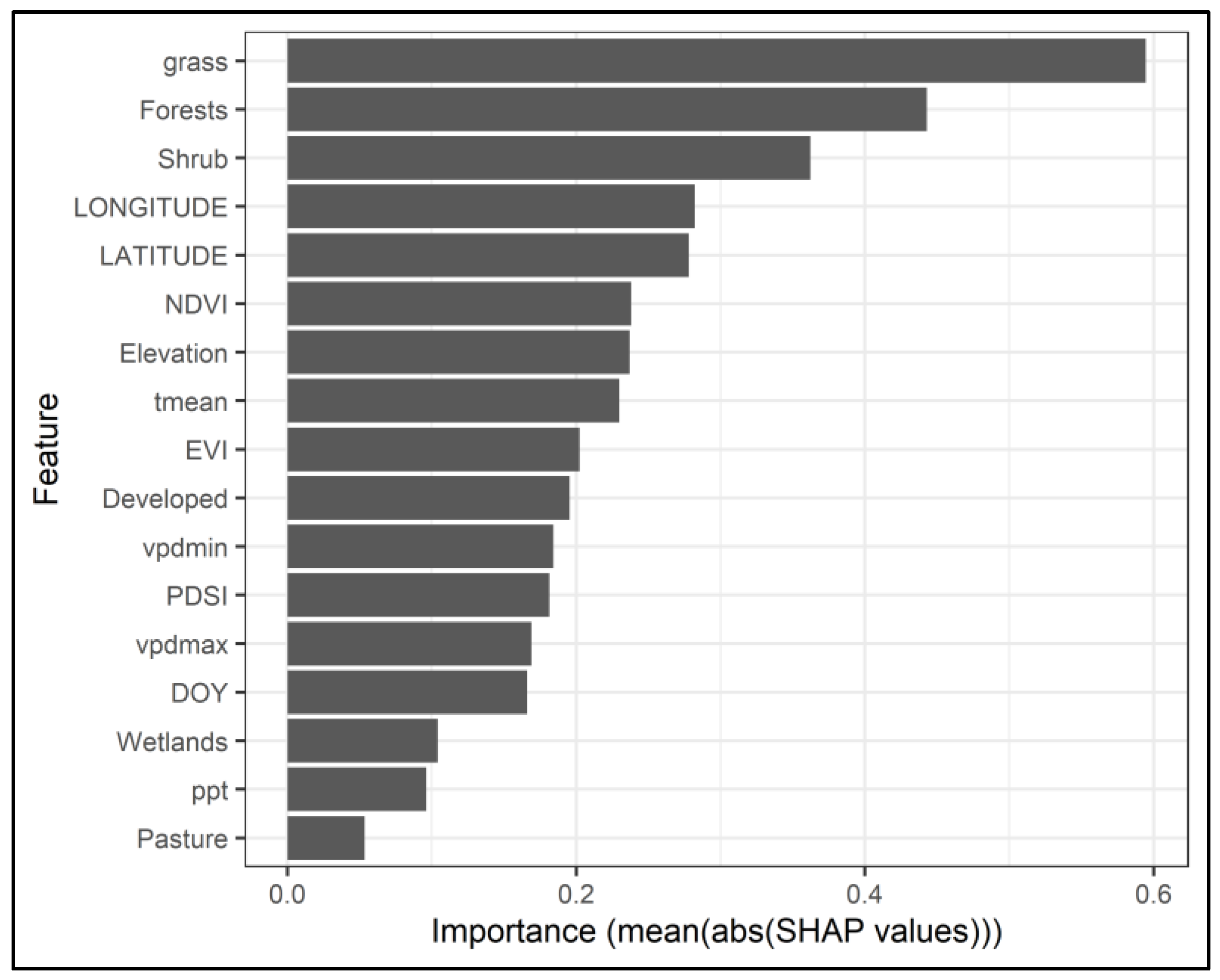

| Feature | Description | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| LATITUDE | Latitude coordinates of wildfire occurrence (decimal degrees) | 25.2 | 49 |

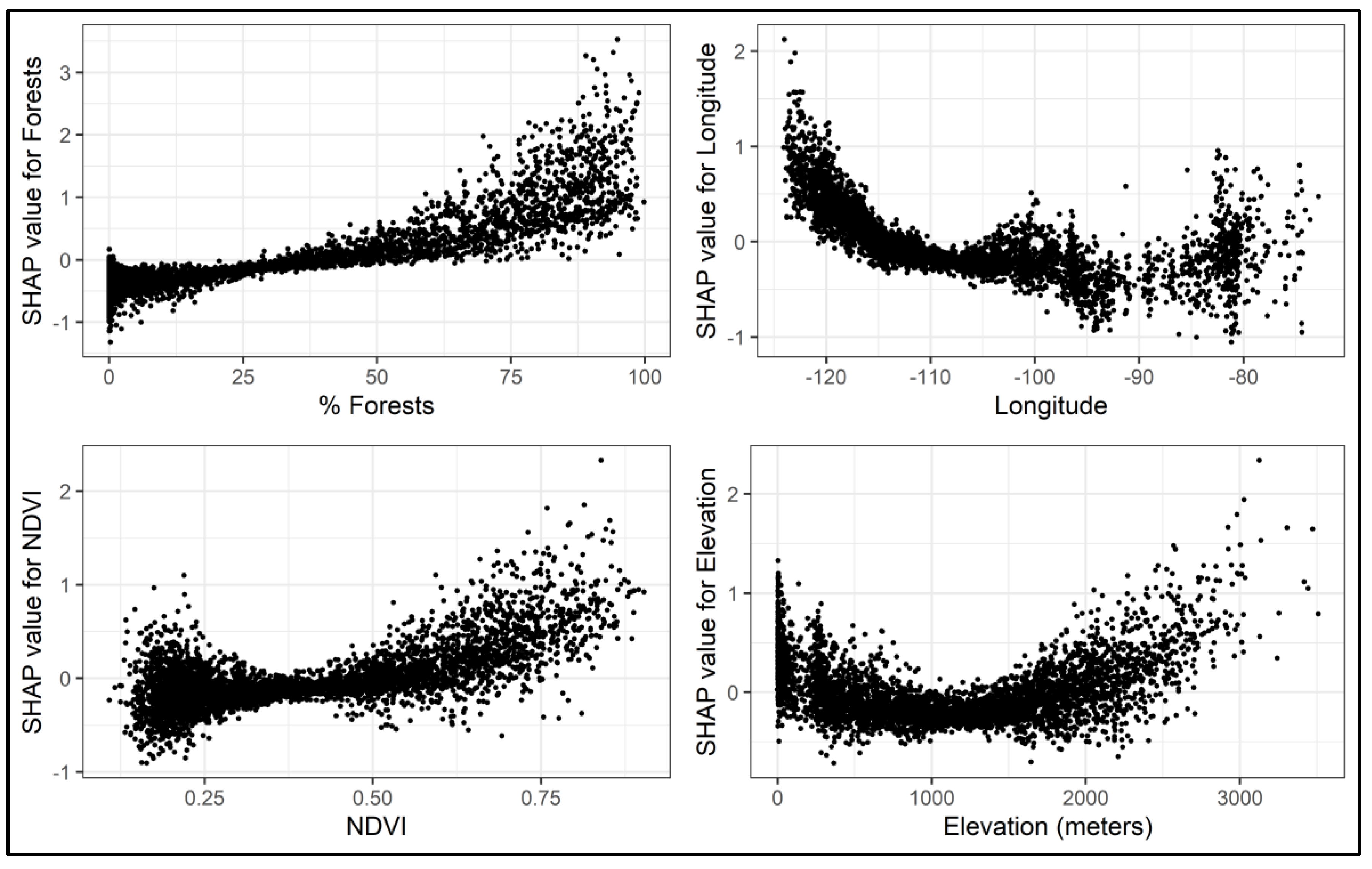

| LONGITUDE | Longitude coordinates of wildfire occurrence (decimal degrees) | -124.1 | -72.8 |

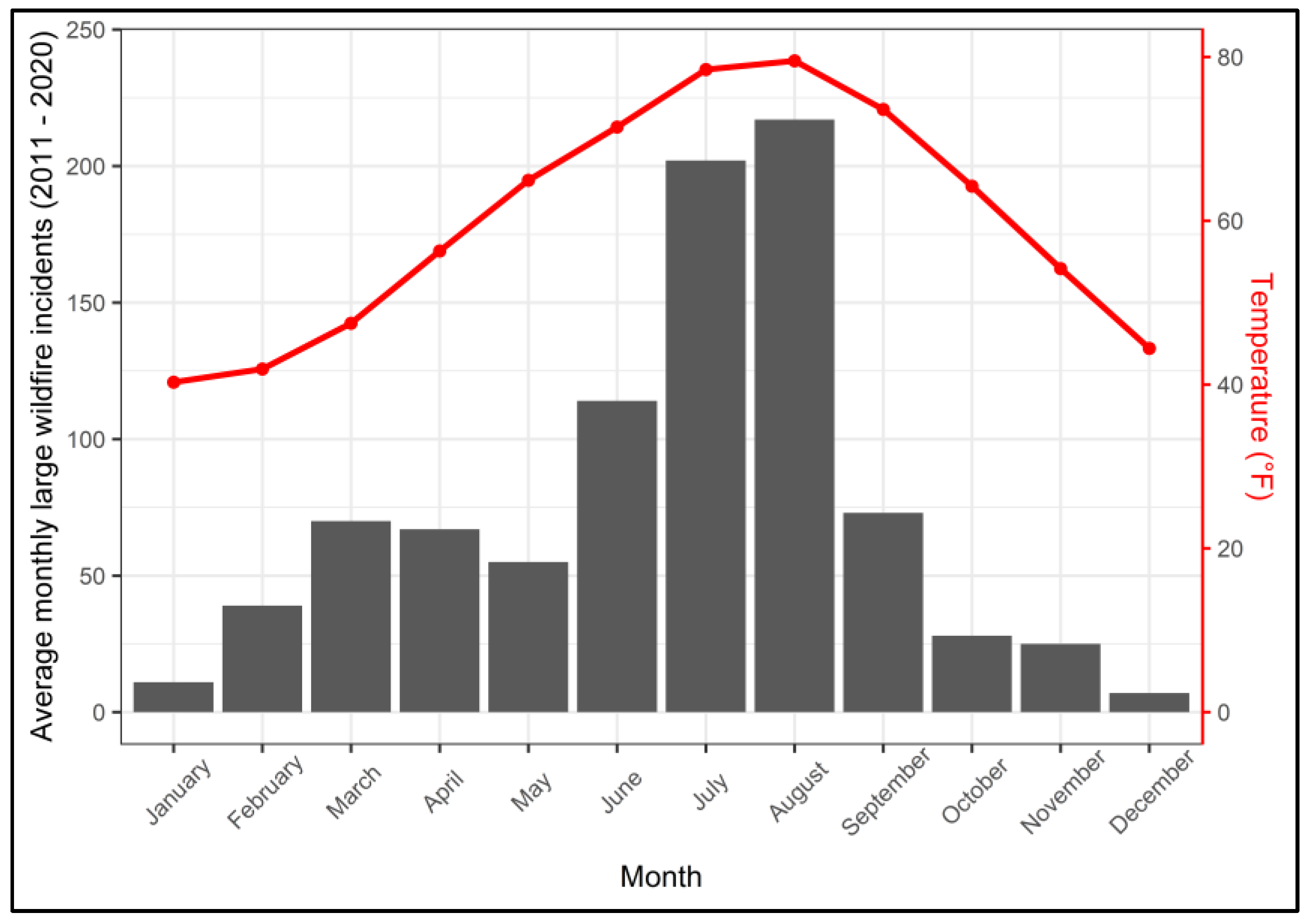

| DOY | Wildfire ignition day of year | 1 | 365 |

| ppt | Total monthly precipitation for month of wildfire ignition | 0 | 1063.2 |

| tmean | Average monthly temperature for month of wildfire ignition | -5.3 | 36.8 |

| vpdmax | Maximum vapor pressure deficit for month of wildfire ignition | 2.7 | 81.8 |

| vpdmin | Minimum vapor pressure deficit for month of wildfire ignition | 0 | 35.3 |

| PDSI | Palmer Drought Severtiy Index during ignition date | -8.1 | 7.6 |

| Developed | % NLCD developed around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 64.2 |

| Forests | % NLCD forests around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 99.8 |

| Shrub | % NLCD shrub/scrub around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 100 |

| grass | % NLCD grasslands/herbaceous around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 100 |

| Pasture | % NLCD hay/pasture around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 74 |

| Wetlands | % NLCD wetlands around 4-kilometer buffer of wildfire ignition | 0 | 100 |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index for month of wildfire occurrence | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| EVI | Enhance Vegetation Index for month of wildfire occurrence | 0 | 0.7 |

| Elevation | Elevation of wildfire occurrence | -2 | 3507 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).