1. Introduction

Uncontrolled cellular proliferation in the body is a hallmark of the disease known as cancer (Chu & Mehrzad, 2023). Prostate cancer (PCa) is the type of tumour that affects the prostate gland, a tiny walnut-shaped organ found just below the bladder in males (Ha et al., 2021). It is among men's most commonly diagnosed cancers, and it remains the reason for cancer-related deaths globally (Ellinger et al., 2022). The frequency of PCa has risen over the past few years, with an estimated incidence rate increase of 1 in every 52 males between 50 to 59 years developing the disease in their lifetime (Rawla, 2019; Nevedomskaya & Baumgart, 2018). Age increases the risk of PCa, with men over fifty being diagnosed with the majority of cases. In 2020, there were well over 1.4 million new cases of PCa globally (Wang et al., 2022). Men from North America, Europe, the Caribbean, and Latin America, have high incidence rates but low mortality compared to those from Africa and Asia, which have shown lower incidence and higher PCa mortality rates (Osadchuk & Osadchuk, 2022). A lot of factors could be responsible for the disparities in the incidence and mortality of PCa according to geographic and racial distribution (Badal et al., 2020). There have been reported varying incidence rates of PCa widely across different populations and regions, with higher incidence rates and low mortality being observed in Western countries compared to Asian and African populations (Wang et al., 2022). These disparities could be due to the environment, variations in genetic factors and improved access to health care, increased awareness of the disease and early diagnosis (Badal et al., 2020). More thorough research is required to comprehend the natural history and genuine frequency of PCa in Nigeria and Africa as a whole.

One proactive method for looking for indications of PCa early is the well-known Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test. Over the years PSA test has been used to diagnose PCa although not very reliable because it is not specific. PSA levels can rise as a result of prostate cancer. However, many non-cancerous illnesses can also raise PSA levels. Therefore, it cannot offer accurate diagnostic data regarding the prostate's health. A digital rectal exam is an additional screening procedure that is frequently performed in conjunction to a PSA test. PCa may be indicated by high PSA levels, but many other conditions, such as an enlarging or inflamed prostate, can also cause elevated PSA levels. As a result, research has concentrated on finding precise and more trustworthy biomarkers for PCa early detection. Technological advancements have made new and inventive techniques for detecting and treating PCa possible. The advancement of complex imaging methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has increased the precision of diagnosis and enabled earlier disease detection (Hu et al., 2023). It is crucial to remember that the prevalence of PCa is predicted to rise as a result of both population aging and economic growth. Three known risk factors for PCa are getting older, being black, and possessing a family history of the condition.

The complex process of cancer progression is influenced by numerous genetic and molecular abnormalities; people with tumors have been shown to have more genetic mutations (Zhao et al., 2022). PCa, among other types of cancer, develops and progresses in part due to the nuclear transcription factor, the androgen receptor (AR) (He et al., 2018). Genes supporting cell survival and growth are activated when AR binds to unique regions on the DNA androgen response elements (AREs) (Manzar et al., 2023). In PCa, AR is expressed more frequently, and its activity is critical for the survival and growth of the cells. Several studies have indicated that inhibiting AR could successfully stop prostate cancer cells from growing (Fernandez-Perez et al., 2023). PCa patients frequently receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which lowers the levels of androgens like testosterone that bind to and activate AR (Davis, 2022). However, many PCa cells eventually become resistant to ADT, and eventually lead to castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). This is often associated with increased AR activity (Crawford et al., 2018). Recent research has focused on developing new strategies that target AR in PCa, including the development of AR antagonists that can bind to AR thus inhibiting AR activity and signaling pathways (Crawford et al., 2018). Additionally, studies show that AR interact with other signaling pathways, like PI3K/Akt pathway, and targeting these interactions may also be a promising strategy for treating PCa. In this report, we summarized the current understanding of AR in the susceptibility, diagnosis and treatment of PCa thus highlighting potential therapeutic strategies for targeting AR in PCa.

1.1. Brief History of Androgen Receptor (AR)

The testis and adrenal glands produce androgens, a group of steroid hormones that have a role in puberty's secondary sexual characteristics as well as the development of the male sex in a healthy foetus (Weidemann & Hanke, 2002). Androgens are a type of steroid hormone that is derived from cholesterol with a 19-carbon structure. Moreover, androgens are the precursors for the production of female sex hormones, called estrogens, which are formed from androgens through various enzymatic processes such as hydroxylation, elimination, and aromatization, with the help of an enzyme called aromatase. Androgens serve a crucial part in the survival and growth of organs of the male reproductive system, including the prostate, through the regulation of gene expression levels. They do this largely through AR, which is a transcription factor that is ligand-dependent (Levine, Garabedian & Kirshenbaum, 2014). The earliest proof of androgen receptors came from research on the effects of androgens on the reproductive system conducted in the 1930s and 1940s. Researchers began investigating the androgens' mode of action in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1958, a group at the University of Illinois under the direction of Paul Zamboni discovered that androgens encourage the development of the prostate gland in rats. As a result, it was postulated that androgens exert their effects via interacting with certain cell receptors. Androgen receptors were first identified from rat prostate tissue in 1968 by a team at the University of Chicago under the direction of Elwood Jensen. The receptors were discovered to be androgen-specific and to have a strong affinity for testosterone (Mendelsohn & Karas, 2005). This finding opened the door for more investigation and offered compelling evidence for the existence of AR.

The AR is found in a variety of target tissues, and its activity and levels change by the initiation of certain cellular processes (e.g., malignant transformation, sexual development) (Chang et al., 1995). Three researchers independently identified and characterised the AR in the late 1960s: Ian Mainwaring, Nicholas Bruchovsky, and Shutsung Liao (Mainwaring, 1969). Through a chemical screen, the first anti-androgen, cyproterone, was unintentionally found. Cyproterone acetate (CPA), which displayed improved anti-androgenic activity, was created by adding an acetate group later on (Neumann, 1994). The need for non-steroidal anti-androgens was sparked by the limits of CPA, particularly its link to a severe sexual dysfunction that is comparable to surgical castration (Davies & Zoubeidi, 2021).

1.2. AR Family Members

Three receptors make up the AR family: the androgen receptor (AR), the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and the progesterone receptor (PR). These receptors, which are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, control how genes are expressed in response to the binding of hormones (Willems et al., 2011). A transcription factor known as androgen receptor (AR) controls how genes are expressed in response to androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). It is vital for the development, differentiation, and function of the prostate gland, muscular mass, and bone density in males. Additionally, AR controls the growth of hair, the adrenal gland, and female reproductive tissues. As reported by Chang et al. (1995), AR is also implicated in the onset and spread of prostate cancer (PCa). Huggins and Hodges initially established that prostate cancer responds to androgen deprivation, and it has been evident ever since that PCa is dependent on AR activation for survival and growth (Davey & Grossmann, 2016). The activities of AR are essential for PCa development. The primary method of treating metastatic PCa is to stop the activation of the AR's ligand through androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which inhibits the synthesis of androgens or uses anti-androgens to compete with androgen binding to AR (Senapati, Kumari & Heemers, 2020).

The Progesterone Receptor (PR) can activate and inhibit the transcription of its target genes and is activated by the hormone progesterone. The PR molecule has domains for ligand binding, DNA binding, and transcription activation. In the reproductive system of females which includes the ovaries, uterus, and mammary glands, PR is necessary for ovulation, implantation of the fertilised egg, and the upkeep of pregnancy (Wetendorf & DeMayo, 2012). In the ovary, PR is only expressed in the granulosa cells of preovulatory follicles (Akison & Robker, 2012). Furthermore, PR determines immune function, bone density, mammary gland development, and the onset and progression of breast and ovarian cancer. Breast cancer can be classified as either estrogen-receptor-positive (ER+), progesterone-receptor-positive (PR+), or ER+/PR+. Mammary gland growth is directly linked to the actions of progesterone and oestrogen on breast tissue.

The actions of glucocorticoids in cells are mediated by the gene transcription factor glucocorticoid receptor (GR) that is stimulated by the hormone cortisol. In addition to the oestrogen receptor (ER), PR, AR, and the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), which lacks a known ligand, it is a member of the nuclear receptor (NR) family of intracellular receptors (Timmermans, Souffriau & Libert, 2019). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body's stress response system, is controlled by the GR, which is also important in controlling inflammation, immunological response, and glucose metabolism. Additionally, GR contributes to the onset and progression of numerous illnesses, such as autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and asthma (Nicolaides, Chrousos & Kino, 2000). The AR, GR, and, PR play a role in many physiological processes, including bone density, immunological function, sexual differentiation, and reproductive function. Several diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disorders, have been tied to the onset as well as the progression of deregulation of these receptors.

1.3. AR Expression

The testes, prostate, and other male accessory organs are the main sites of AR expression in healthy males. Here, they mediate the effects of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) on gene expression and cellular function (Aurilio et al., 2020). The fact that androgens have significant impacts on several organ systems is not surprising given that the AR is expressed in a number of reproductive organs. Many male and female sexual, behavioural, and somatic functions that are essential to long-term health are regulated in part by this. Male androgen shortage often results from decreased testosterone synthesis as a result of organic hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis disease that causes decreased AR activation. Except for the uncommon illness of androgen resistance, this condition often reflects a lack of the ligand rather than an AR-related pathology. A multi-system condition called androgen deficiency is diagnosed clinically based on indicators, symptoms, and biochemically verified by demonstrating abnormally low blood testosterone levels (Davey & Grossmann, 2016). Zhu and Kyprianou examined an active area of study on the capacity of AR to interact with important growth factor signalling occasions in the control of cell cycle, PCa cell differentiation, and apoptosis. Prostate cancer's pathophysiology has been linked to the epidermal growth factor and its membrane receptor, epidermal growth factor-1 receptor (Davey & Grossmann, 2016).

In females, the expression of AR is more constrained and predominantly localised to the ovaries, adrenal glands, and a few other organs, where it regulates the production and metabolism of androgen. Breast cancer also exhibits androgen receptor (AR) expression. Later, several studies verified this expression-based subgroup (Vidula et al., 2019). Cancer patients may experience deregulated AR expression, which helps the condition advance. For instance, the over-expression and mutation of ARs in prostate cancer typically result in enhanced androgen sensitivity and the emergence of resistance to androgen-deprivation treatment. Similarly to this, higher AR expression and signalling have been linked to tumour development and metastasis in breast cancer (Senapati, Kumari & Heemers, 2020). The description of the androgen-regulated gene expression programme in normal and malignant prostate cancer cells has been an interest of significant investigation in recent years. High throughput gene expression analysis advancements have made this possible (Lonergan & Tindall, 2011).

1.4. AR Structure

Androgens exert their effects through the ligand-binding to its cognate receptor, the Androgen receptor (AR). AR is a member of the nuclear hormone and steroid receptors superfamily, including glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, progesterone, oestrogens, and vitamin D (Jamroze, Chatta & Tang, 2021). Steroid receptors, like the AR, have fundamentally three functional domains: an NH2-terminal domain (NTD) that contains the transcriptional activation function 1 (AF-1), a central DNA-binding domain (DBD) linked to hinge region, and a COOH-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD), which is linked to the DBD by a hinge region and contains the transcriptional activation function 2 (AF-2) (Jamroze, Chatta & Tang, 2021). The AR gene is situated on Xq11-12 and creates a protein that weighs 110 kDa and has 920 amino acids (Messner et al., 2020). The AR gene consists of eight exons, with exon 1 encoding the NTD, exons 2-3 encoding the DBD, exon 4 encoding the HR, and exons 5-8 encoding the LBD as shown in (see

Figure 2). This ligand-dependent transcription factor regulates gene expression that carry out growth and differentiation of the prostate gland (Crona & Whang, 2017). Family members differ in the amino-terminal domain and the hinge region that joins the core DBD to the C-terminal ligand-binding domain (Jamroze, Chatta & Tang, 2021; Shaffer et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Androgen receptor gene and protein (Crona & Whang, 2017).

Figure 1.

Androgen receptor gene and protein (Crona & Whang, 2017).

1.4.1. The NH2-terminal domain

About half of the receptor's 919 amino acid core sequence is taken up by the NTD, which ranges from amino acids 1 to 559 (Alemany, 2022). The AR-NTD differs most from other members of the steroid receptor family in terms of amino acid variability, sharing less than 15% of its amino acid sequence with those of the other steroid receptor-NTDs. It produces the AF-1, which has the Tau1 and Tau5 transcriptional activation units (Tau). When the AR-LBD is removed, the Tau5 area (amino acids 360–528) exhibits constitutive transcription of the AR-NTD without the need for ligands, whereas the Tau1 region (amino acids 141-338) is necessary for ligand-dependent transactivation of the AR (Messner et al., 2020). Tau-5 is a signal-dependent transactivation site, in contrast to Tau-1, and is activated by signaling events arising from the protein kinase C-related kinase (PRK-1). Other steroid receptor-NTDs do not have the three distinct homo-polymeric amino acid repeats found in the AR-NTD. There are three types of repeats: poly-glutamine (poly-Q), poly-proline (poly-P), and poly-glycine (poly-G). The poly-P tract is about 9 residues in length and begins at amino acid 327. The poly-glycine tract is 24 residues long and begins at amino acid 449. The poly-Q tract, found at around amino acid 59, has a usual range of between 17–29 residues. Although the particular relevance of these three repetitions is unknown, the poly-Q tract has been the subject of intense study to understand its involvement in AR activity. It has been shown that the length of the poly-Q tract and AR transcriptional activity are inversely correlated. The AR-poly-Q tract's length may also affect how directly AR interacts with its co-regulatory proteins, which control AR-mediated transcription. Shortening the poly-Q tract of AR to 17 amino acids or less, as was described earlier, has been linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer. The AR-NTD is appealing for AR-specific protein interactions due to its distinctive sequences and characteristics, which may be crucial for guiding AR-specific responses. Finding novel protein partners that can interact with the AR-NTD could help to clarify the process though which cells respond to androgenic ligands in an AR-specific manner. In the reverse yeast two-hybrid system (RTA), our group has discovered a number of novel AR-NTD interacting proteins by using the N-terminus of AR as bait. An example of these protein is the TATA binding protein Associated Factor 1 (TAF1).

1.4.2. The Central DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the hinge region

The DBD and the hinge region (HR) of the AR are respectively comprised of amino acids 560-623 and 624-676. These areas perform a variety of tasks, such as dimerization of active AR molecules, nuclear localization of activated receptors, and binding to DNA at consensus sequences in the enhancer part of regulated AR genes (Shaffer, McDonnell & Gewirth, 2005). Moreover, the DBD of AR interacts with potential transcriptional co-regulators as well as proteins that make up the basic transcriptional apparatus. It is important for the dimerization of AR and the binding of dimerized AR to certain DNA patterns. The cysteine residues in this domain, which promote the development of two zinc finger motifs, contribute to these DBD activities (Messner et al., 2020). Two conserved zinc finger motifs in the DBD of the AR and other steroid receptors interact with DNA regulatory regions. These DNA sequences in the promoters of androgen-regulated genes are referred to as androgen response elements (ARE) for AR. Inverted palindromic sequences with two half-sites and a 3-nucleotide spacer (5'-GGA/TACAnnnTGTTCT-3') make up the ARE. Whereas the second zinc finger of the DBD stabilizes receptor-DNA connections, the first NH2-terminal zinc finger of the DBD is in charge of detecting ARE sequences and selectively binding to AREs in the main groove of DNA. The AR-second DBD's zinc finger may have an impact on how well the receptor binds to AR-specific ARE. Nuclear localization sequence (NLS) (amino acids 613-633) found in the hinge region of the AR directs the activated receptor to the nucleus (Brtko, 2021; Ban et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Depiction of the interaction of AR dimer bound to an ARE (Shaffer et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Depiction of the interaction of AR dimer bound to an ARE (Shaffer et al., 2004).

1.4.3. The Ligand Binding Domain

The ligand binding domain (LBD) of AR is a region within the AR protein that is responsible for binding to androgens, which are hormones that play a key role in the development and maintenance of male characteristics (El Kharraz et al., 2021). The LBD is located at the C-terminus of the AR protein and is composed of several structural elements, including 12 alpha-helices and several beta-strands. The LBD of AR, which consists of amino acids 616-919, includes a hydrophobic pocket that accepts androgenic ligands such as DHT and testosterone. The LBD is well conserved among different species such as human, rat, and mouse, with degrees of homology ranging from 20-55% with LBDs of other members of the steroid receptor family. When an androgen hormone binds to the LBD of the AR, it causes a conformational change in the receptor, which allows it to translocate to the nucleus of the cell and bind to androgen response elements (AREs) on DNA. This binding leads to the activation of target genes involved in the regulation of a wide range of physiological processes, including male sexual development, muscle growth, and bone density. The AR-LBD is particularly critical for prostate cancer because it is the main target of current androgen deprivation therapies. Despite the availability of potent androgen antagonists in clinics, the AR-LBD gene can be mutated to cause the improper activation of AR by non-androgenic substances, leading to ligand-binding promiscuity. Over 30% of prostate cancers possess AR mutations, and several AR variants have been discovered that lack receptor specificity in the absence of traditional ligands. The majority of mutations in the AR affects the ligand binding pocket and are found in three primary regions of the LBD, specifically amino acids 670-678, 710-730, and 874-910 (Shaffer et al., 2004). The most frequently observed variants in tumors are T877A, T877S, and H874Y. The T877A mutation is particularly well-known as it is found in the LNCaP human PCa cell line, as well as cases of advanced prostate cancer. Overall, these mutations make the receptor more sensitive to adrenal androgens or other steroid hormones compared to the wild type AR. This may be due to the recruitment of various co-activators, which enable the AR to bind other steroid ligands, and allow antagonists to act as agonists to activate the AR in an androgen-depleted environment (Crona & Whang, 2017).

The mutations at Gln-670, Ile-672, and Leu-830 increase AR transcriptional activity, meaning that they enhance the ability of the AR to activate the expression of genes that promote prostate cell growth and survival (Estébanez-Perpiñá et al., 2007). These mutations are often found in advanced prostate cancers that have become resistant to hormone therapy. On the other hand, mutations at Arg-840 and Asn-727 decrease the ability of the co-activator protein SRC-2 to bind to and activate the AR. SRC-2 is a co-activator that helps to enhance AR activity by facilitating its interaction with other proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mutations that impair SRC-2 binding can reduce AR activity and potentially slow the growth of prostate cancer cells. Many substances that may fit into the BF-3 pocket and decrease androgen receptor activation have been discovered.

2. Signal Transduction

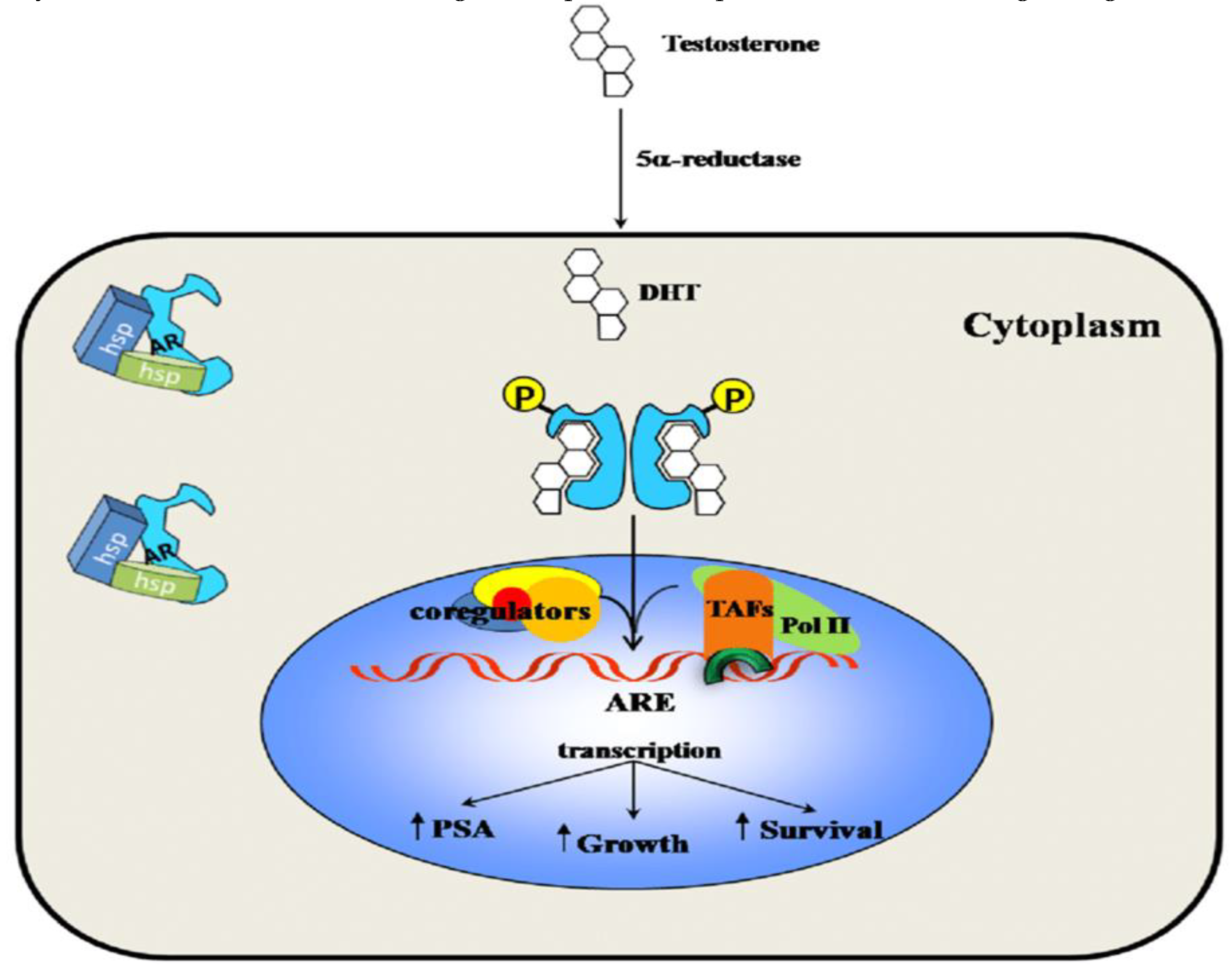

The AR signalling pathway is a multi-step process with numerous regulatory components. The ligand-free AR is cytoplasmic in location, bound by a number of cochaperones such as HSP70, HSC70 and HSP90, which keep the protein in a ligand-binding conformation and prevent it from degradation. When androgens bind to the AR, the receptor undergoes a structural shift that causes it to transport itself to the nucleus. AR changes conformation when activated and promotes NTD/LBD interactions and the binding to AR coregulators, for the best transcriptional response (Westaby et al., 2022). The AR subsequently attaches to motor and transport proteins, such as dynein and importin-α/-β, which recognize the nuclear localization signal of the AR and facilitate the AR complex's translocation to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, the AR dimerizes with another AR molecule and binds to specific regions of DNA known as androgen response elements (AREs), which are located in the promoters of androgen-responsive genes. The binding of the AR to AREs initiates a cascade of events that result in the transcription of androgen-responsive genes. This process is regulated by several co-regulators, including co-activators and co-repressors, which can modulate the activity of the AR by either enhancing or inhibiting its transcriptional activity. AR signaling is activated by binding of androgens, such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, to the receptor. This triggers a cascade of events leading to the regulation of target gene expression and subsequent cellular responses (Jacob et al., 2021; Feng & He, 2019; Aurilio et al., 2020). However, AR signaling is also subject to crosstalk with other signaling pathways, which can modulate its activity and contribute to PCa progression especially observed in CRPC phenotypes and androgen-independent PCa cases (Jacob et al., 2021). Also, Genes involved in preventing apoptosis and promoting cellular proliferation are subject to transcriptional activity modulation by the AR (Jacob et al., 2021).

Non-genomic routes that entail the activation of several intracellular signalling cascades, such as the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, exist in addition to the traditional AR signalling pathway. Non-genomic mechanisms that promote cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis can also contribute to the formation and progression of PCa. Additional post-translational changes that can modify the activity, location, and stability of AR can also have an impact on its signalling, including phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination. PCa eventually develops and spreads as a result of an imbalance in AR signalling that encourages cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis. Therefore, targeting AR signaling has emerged as a promising strategy for the treatment of PCa.

2.1. AR Ligand—Androgens

The AR is the mechanism through which the actions of androgens, a class of steroid hormones, are carried out. They include testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androstenedione, among others. Testosterone and DHT are the two most significant androgens involved with prostate cancer. Each androgen, which functions via the androgen receptor (AR), has a distinct function during the development of male sexual differentiation. Androgens are synthesized from cholesterol in the human body. There are multiple sequential processes involved in turning cholesterol into testosterone. The steroidogenic acute regulatory protein facilitates the first stage, which includes the migration of cholesterol from the outside to the inner mitochondrial membrane. The P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme then causes the side-chain cleavage of cholesterol. This conversion, which results in the creation of pregnenolone, is a rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of testosterone. Several enzymes, such as 17-hydroxylase, 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, are needed for subsequent processes (

Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Androgen biosynthesis (McEwan & Brinkmann, 2021).

Figure 3.

Androgen biosynthesis (McEwan & Brinkmann, 2021).

In males, the testes' Leydig cells serve as the body's main source of androgens like testosterone (Gurung, Yetiskul & Jialal, 2021). These cells respond to the pituitary gland's luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulates them to produce and secrete testosterone. In males, the production of androgens is not solely attributed to the testes. The adrenal cortex, a component of the adrenal gland situated above the kidneys, also plays a role in synthesizing androgens. The adrenal cortex produces a precursor hormone called dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which may be transform to testosterone in peripheral tissues such as testes (Gurung, Yetiskul & Jialal, 2021). The hypothalamic/pituitary/gonadal axis then directs androgens to diffusely penetrate the cytoplasm of target organs like the prostate and skin via the bloodstream. Hydrophobic molecules, which are not soluble in water, include androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). They attach to particular transport proteins, such as sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin, in order to move through the bloodstream (Alemany, 2022). The majority of circulating androgens (approximately 98%) are bound to these transport proteins, leaving only a small percentage (approximately 2%) in the free, unbound state. This bound fraction of androgens is reversible and can be released from the protein binding sites as needed to exert their biological effects in target tissues. The binding of androgens to transport proteins is an important mechanism for regulating their distribution and availability in the body, and alterations in the levels of these transport proteins can have significant effects on androgen bioactivity.

Androgens, which include testosterone and 5-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), are responsible for the growth, differentiation, and maintenance of prostatic tissues and the development of male sexual organs and secondary sex characteristics (Carpenter et al., 2021). However, the effects of testosterone and DHT are not the same in all androgen-sensitive tissues. The androgen receptor interacts differently with each androgen, with DHT binding to the receptor with higher affinity than testosterone (Alemany, 2022). For example, the prostate gland, scrotum, urethra, and penis are all androgen-sensitive tissues that respond to DHT, not testosterone. DHT has a higher affinity for the androgen receptor than testosterone and is a more potent androgen, which explains why it is the active ligand in these tissues (Feng & He, 2019). Nevertheless, testosterone can achieve high local concentrations through diffusion from neighboring testis during sexual differentiation to make up for its lower androgenic potency. The testosterone signal is amplified by conversion to DHT in locations that are further away, such as the urogenital sinus and urogenital tubercle. In addition the role it plays in the formation of male reproductive organs, testosterone and DHT also have many other physiological functions in males, including the regulation of secondary sexual characteristics, such as body hair growth, muscle mass, and voice deepening, as well as the maintenance of bone density and the production of sperm (Molina, 2013).

3. Prostate Cancer Susceptibility and AR

While lifestyle and environmental factors play a role in its development, genetics also plays a significant role in PCa susceptibility (Mbemi et al., 2020). Genetics plays key role in the development of PCa and has potential implications for its prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Age, ethnic background, and family history are the three main factors that increase the chance of developing prostate cancer (Oladoyinbo et al., 2020). Current epidemiological studies indicate that the development of PCa is strongly associated with hereditary variables, making it one of the most prevalent heritable malignancies. When compared to families without a history of PCa, those with heritable ties to men who have been diagnosed with the disease have a greater likelihood of getting PCa. The estimated percentage of hereditary factors contributing to PCa is approximately 5-15% (Vietri et al., 2021). The genes involved in homologous recombination (HR) (BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, ATM, PALB2) and mismatch repair (MMR, PMS2, MSH6, MLH1) are now the ones most consistently associated to prostate cancer risk. These genes' mutations have been found to be often linked to an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. Research have verified their link to a higher incidence of PC alongside other genes such as HOXB13, BRP1, and NSB1 although recommended for further research. HOXB13 mutation is related to high risk of PCa in a more recent study (Vietri et al., 2021). Other genetic abnormalities, including as mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, have also been linked in studies to a higher risk of PCa. An increased risk of PCa has been linked to mutations in this gene (Foley et al., 2023). These genes are commonly associated with breast and ovarian cancer, but have also been linked to an increased risk of PCa. Other genes, such as the RNASEL gene and the MSR1 gene, have also been implicated in PCa development (Johnson et al., 2021).

The well-known androgen receptor (AR) gene, which regulates the activity of hormones that promote prostate cell growth is at the center of prostate cancer progression. The AR protein is made according to instructions from the AR gene. Androgens are hormones that are essential for the best possible development of male sex both before and during puberty (Rey, 2021). Androgens are hormones that are essential for the best possible development of male sex both before and during puberty. Studies have shown that genetic variations in the AR gene are associated with an increased risk of PCa. These variations can alter the function of AR and lead to an increased sensitivity to androgens, which can promote the development of PCa. Studies of polymorphisms in androgen-related genes have shown that the variation in the androgen receptor impacts the risk of PCa (Song et al., 2023). A polymorphism sequence of CAG repeats encoding polyglutamine can be found in the first exon of AR, which codes for the N-terminal domain important for trans-activational regulation. There are a variety of racial or ethnic group discrepancies as a result of the mean repeat number of CAGs in whites being longer than in African-Americans (Hsing et al., 2000). Longer CAG repeats are linked to androgen insensitivity syndrome, while shorter CAG repeats are correlated with enhanced AR transcriptional activity. Men with shorter CAG repeats had a slightly higher chance of developing prostate cancer, according to epidemiological studies on prostate cancer and CAG repeat length in the AR gene. The understanding of the genetic basis of PCa has led to the development of genetic testing for individuals at high risk for the disease (Allemailem et al., 2021). This testing can help identify individuals who may have an inherited risk for prostate cancer, and enable them to take steps to reduce their risk, such as increased screening and lifestyle modifications.

4. Role of Androgen Receptor in PCa

AR is a crucial player in the progression and development of PCa (Shaffer et al., 2004). In healthy prostate tissue, AR signalling is tightly regulated, and androgens stimulate the growth and differentiation of prostate epithelial cells. However, in PCa, AR signaling becomes dysregulated, and the cancer cells become more reliant on androgen signalling for their growth and survival. This is why ADT, which reduces the levels of androgens in the body, is often used to treat PCa. AR is expressed in prostate cells, and androgen binds to it, triggering a series of biological reactions that contribute to cell survival, growth, and proliferation (Zhang et al., 2022). The biochemical activity of androgen is started by testosterone or DHT attaching to its specific receptor, the AR, activating it (

Figure 4).

When unattached from its ligand, AR is found in the cytoplasm as a component of an inactive complex that also contains the heat shock proteins HSP90, HSP40, and HSP70 (Ratajczak, Lubkowski & Lubkowska, 2022). These proteins play a crucial function in maintaining an accessible AR shape and preventing premature AR degradation. The AR undergoes a conformational change when it binds to a particular ligand, creating a more compact and stable form of the receptor. When AR is activated, it separates from heat shock proteins and moves to the nucleus, engaging in homodimer interactions with DNA androgen response elements (Messner et al., 2020). A second dimerization interface is needed to bind to an AR response element since AR employs the DBD to bind to ARE elements. The protein-protein and protein-DNA connections that allow for this unexpected structure are preserved, and some AR-specific dimerization contacts are responsible for the AR specificity of AR response elements. In order to control the gene-specific expression that affects the development and survival of target cells, the active DNA-bound AR can entice co-regulator proteins and fundamental transcriptional machinery (Takayama, 2018).

4.1. Prostate Cancer Progression

The AR is a critical driver of PCa progression, and its role in the development of metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) is well established. Here is a brief overview of how AR drives PCa to the metastatic castration-resistant phenotype: Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a common treatment for advanced PCa. ADT works by reducing levels of the male hormones, which are the primary fuel for PCa growth. However, despite initial response to ADT, prostate cancer cells eventually develop mechanisms to bypass the need for androgens and continue to grow in the absence of these hormones. This is known as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). In CRPC, the AR signaling pathway becomes hyperactive and plays a critical role in driving prostate cancer progression. This hyperactivation of the AR can happen in a number of ways, such as: Amplification or overexpression of the AR gene, Mutation of the AR gene, Ligand-independent activation of the AR (i.e., activation of the receptor in the absence of androgens). The hyperactive AR signaling pathway drives several key aspects of mCRPC, including: Increased cell proliferation and survival, Resistance to apoptosis (programmed cell death), Increased cell migration and invasion, leading to metastasis, Increased expression of genes associated with stemness, which may contribute to the development of treatment resistance.

PCa depends on androgens for growth, and early-stage disease can be managed with radical prostatectomy or radiation ablation of the prostate gland (Fujita & Nonomura, 2019). However, once cancer cells have spread outside of the prostate capsule, the disease is much more difficult to treat. When surgery is no longer an option, androgen withdrawal is usually used to treat prostate cancer patients with advanced disease, which affects about one-third of patients. By eliminating hormones through androgen ablation therapy, the effects of androgens that stimulate growth can be prevented, resulting in cancer cell apoptosis and ultimately tumor regression. However, this approach is not a complete cure, and the average overall survival time is less than 2-3 years. Bypassing the requirement for androgenic growth signals, PCa cells eventually develop castration resistance, which causes uncontrolled growth and elevated PSA levels, even when there are small amounts of androgen. This phenomenon's mechanisms are intricate and still not fully understood. As androgens are crucial for maintaining prostate cells, a key issue is how prostate cells continue to survive after androgen deprivation therapy. Recent discoveries by several researchers suggest that AR is essential for the growth of androgen-resistant PCa. Nuclear AR is expressed at increased levels in more than 80% of regionally progressed castration-resistant prostate tumours, and bone metastases frequently have greater AR levels than the source tumours do. The bulk of the time, improper activation of AR in some way contributes to the recurrence and progression of prostate malignancies. Studies have repeatedly shown that, in a variety of experimental forms of androgen-resistant PCa, the AR gene is the only one that is consistently up-regulated throughout tumour growth (Student et al., 2020). The molecular mechanisms by which progression shifts from androgen dependence to castration-resistant state can be divided into two pathways: those that bypass the AR and those that operate through the receptor. These pathways are not mutually exclusive and often coexist in castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Figure 5.

Androgen-dependent vs. castration-resistant PCa progression (Tortorella et al., 2023).

Figure 5.

Androgen-dependent vs. castration-resistant PCa progression (Tortorella et al., 2023).

PCa cells depend on the androgen-AR signalling pathway for their survival and proliferation throughout progression. However, cancer cells use both the primary and alternate pathways to sustain their growth and survival as they develop into a castration-resistant phenotype. Although AR is involved in the primary pathway, the unfettered pathway avoids it (Tortorella et al., 2023). Castration resistance can be reached through either one of two pathways: one that avoids AR or one that uses the receptor. Apoptotic genes like PTEN and Bcl-2 are downregulated in the first pathway, increasing cell survival. In the second pathway, PCa cells are able to survive via AR due to dysregulated cytokines or growth factors, anomalies in receptor amplitude or genetics, autocrine generation of active androgens, and changes in co-activator expression In the second pathway, unregulated growth factors or cytokines, abnormalities in receptor amplitude or genetics, autocrine synthesis of active androgens, altered co-activator expression, and expression of alternatively spliced AR variants all contribute to PCa cells' survival via AR. These processes result in an AR being stimulated in a way that is binding site-reduced or independent. Targeting the AR signaling pathway has become a cornerstone of treatment for mCRPC.

4.2. Crosstalk between AR and other signalling pathways

The AR's control over transcription regulates various genes important in cell differentiation survival, and proliferation. However, the AR signaling pathway is not independent and often interacts with other signaling pathways, which can modulate its actions and participation in the development of PCa. Several signaling pathways have been implicated in crosstalk with AR signaling, including the PI3K/AKT pathway, Wnt/β-catenin pathway, MAPK/ERK pathway, Hedgehog pathway, and Notch pathway. Activation of these pathways can promote or inhibit AR signaling, depending on the context and cellular environment. Once active, AR regulates a number of regulatory elements to change the metabolism of PCa cells. Importantly, the AR-driven metabolic program depends on activation of the mTOR signaling pathway (Gonthier, Poluri & Audet-Walsh, 2019). An enzyme called phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) is essential for cellular processes like cell division, growth, and proliferation. However, PI3K is frequently altered in cancer. Due of the reciprocal feedback loops that AR and PI3K signaling use, Qi et al. discovered that the suppression of both can be synergistic. Inhibiting AR in conjunction with PI3K or mTOR pathway led to a rise in cell cycle arrestand apoptosis in CRPC cells, which in turn reduced cell proliferation (Michmerhuizen et al., 2020). The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, the GR pathway, and alternative proteins can all be used to activate alternative signaling pathways, restore downstream signaling, and provide resistance to AR-targeted drugs in PCa (Jacob et al., 2021).

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway plays a crucial role in regulating the cell cycle. PI3K converts PIP2 into PIP3, which activates AKT kinase and downstream pathways, including mTOR, that control cell growth, division, and survival. PTEN acts as a negative regulator by removing a phosphate from PIP3 to create PIP2. Inactivation of PTEN through mutations or loss causes hyperactivity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which is common in PCa. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and AR signaling cross-regulate each other through mutual feedback, so inhibiting one pathway stimulates the other. Combining treatments that block both pathways may be an effective strategy for prostate cancer treatment (Pisano et al., 2021).Crosstalk between AR and CDK/pRb promotes cell cycle progression and this has been found to be a very promising therapeutic strategy in PCa especially with combined inhibition of AR and CDK4/6. AR controls the G1-S phase transition of the cell cycle. Thus, boosting CDK activity and causing phosphorylation to cause the inactivation of pRb (Michmerhuizen et al., 2020). Studies have shown that β-catenin interacts directly with AR in yeast and mammalian two-hybrid tests. The interaction sites were found in the LBD of AR and the armadillo repeats in β-catenin (Khurana & Sikka, 2019). β-catenin was identified as an AR interacting protein from a library of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal cells. β-catenin co-localized with AR in the nucleus only in the presence of DHT, and AR antagonists were unable to move β-catenin. The co-translocation was independent of the GSK3, p42/44 ERK/MAPK, and PI3K pathways. The regulatory functions of TIF2 and NTD were altered when β-catenin interacted with LBD. The absence of E-cadherin can increase cellular levels of β-catenin in PCa cells, promoting AR activity during tumor growth, resulting in a more aggressive tumor form (Khurana & Sikka, 2019).

The activation of a number of signaling molecules and pathways, including but not limited to PI3K, IL-6/STAT3, SRC, WNT/-catenin, and MAPK, always follows genomic changes in PCa. These signals support PCa growth, create genotype-phenotype connection, and help receive inputs from the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, active signals cause epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer stem cell (CSC)-like characteristics/stemness, and neuroendocrine differentiation (NED), which alter PC behavior (Tong, 2021). In gene editing mouse models, Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation in the prostate has oncogenic roles in maintaining CRPC proliferation, encouraging EMT and NED, and converting stem cell-like properties to PC cells (Yeh et al., 2019). It has been demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin and AR signaling interact. In order to activate AR signaling and advance CRPC, β-catenin forms complexes with and enhances AR. Additionally, β-catenin increases CRPC by acting as a coactivator with mutant AR (W741C and T877A). AR is recruited to the promoter regions of Myc, cyclin D1, and PSA by Wnt/β-catenin. On the other hand, AR overexpression boosts Wnt/β-catenin signaling's transcriptional activity. Whether in LNCaP cells that express AR or PC3 cells that do not, AR has the ability to induce β-catenin translocation into the nucleus. SOX9 transcriptional factor activation may be used to achieve Wnt/β-catenin-AR feedback signaling (Tong, 2021). AR controls the G1-S phase transition of the cell cycle, boosting CDK activity and causing phosphorylation to cause the inactivation of pRb. Combining AR with CDK4/6 inhibition has also been demonstrated to be a therapeutic approach in prostate cancer due to the interaction of AR with CDK/pRb in encouraging cell cycle progression (Michmerhuizen et al., 2020).

4.3. Targeting AR in Prostate cancer

The physiology of healthy PCa cells depends on AR signaling, but they overexpress it, which in turn promotes unrestrained proliferation (Crawford et al., 2018). ADT, also known as surgical or medical castration, has been the cornerstone of intervention for advanced form of this cancer for the past 80 years (Severson et al., 2022). A crucial therapeutic approach for PCa involves focusing on the androgen receptor signaling pathway. ADT is a popular remedy for advanced PCa because it prevents androgen production or action. Although ADT is effective in treating a lot of advanced PCa, resistance to the drug eventually develops in most sick people, causing the disease to proceed to the circumcision PCa phenotype (CRPC), which is always fatal (Nevedomskaya, Baumgart & Haendler, 2018). In the past, it was believed that resistance to ADT was unrelated to the AR axis, but in the past 20 years, it has been evident that, even after castration, AR signaling is still essential for tumor growth. Abiraterone, enzalutamide, darolutamide, and apalutamide are a few examples of novel hormonal drugs with increased anticancer activity that have been developed as a result of this discovery (Negri et al., 2023). This includes LHRH analogs, which have already been reviewed and are almost entirely provided through injection. Relugolix, an orally accessible, nonpeptide LHRH antagonist, has recently been created. It competitively binds to and blocks the anterior pituitary gland's LHRH receptor. Relugolix reduces LH secretion and release as well as LHRH binding to the LHRH receptor, which lowers the release of testosterone from Leydig cells of the testes.

Recent research has focused on developing new strategies to target AR in PCa (Westaby et al., 2022). These include the development of AR antagonists that can bind to AR and inhibit AR activity, and interference with AR signal transduction. More recently, novel AR-targeted therapies, such as second-generation anti-androgens and androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs), have been developed that target the AR directly or it’s downstream signaling pathways. These therapies are being actively researched in clinical trials because they have shown promise in improving outcomes for patients with advanced PCa.

4.4. Emerging Therapies Targeting AR

Prostate cancers need various forms of treatment since they might behave in various ways. Indeed, ADT has served as the primary form of therapy for advanced PCa for many years (Westaby et al., 2022). Androgens are male hormones, such as testosterone, which can stimulate the growth of PCa cells. ADT can aid in slowing the development and reduce burden of PCa by lowering the amount of androgens in the cells (Tortorella et al., 2023). The ADT comes in a variety of forms, however the most used method is the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) sympathomimetic or adversaries that can inhibit yield of testosterone by the testicles. Another approach is to use medications called anti-androgens, which block the effects of androgens on PCa cells. Depending on the stage and severity of the PCa, ADT may be used alone or in conjunction with other therapies like radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Despite the fact that ADT can be helpful in symptom improvement and slowing the spread of PCa, all patients eventually develop deadly metastatic CRPC (Tortorella et al., 2023). As a result, second-generation hormonal treatments have substantially improved the prognosis for those with advanced PCa. Precision medicine is the subject of recent research. Every patient will receive treatment that is specifically tailored to their needs from the outset. Precision medicine must cover a lot of ground because there are so many different forms of prostate cancer. It's critical to keep in mind that not everyone benefits equally from developing medicines. Also, some of these medicines are still awaiting FDA approval. There are several emerging therapies for PCa (Alabi, Liu & Stoyanova, 2022), including: Immunotherapy: A form of therapy called immunotherapy aids the immune system's recognition and destruction of cancerous cells. Several immunotherapy drugs, such as checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cells, and cancer vaccines, are being developed and tested in clinical trials. Targeted therapies are drugs that specifically target cancer cells based on their genetic mutations or other specific characteristics. For PCa, several targeted therapies are being developed, including drugs that target the androgen receptor pathway and drugs that target specific enzymes and proteins involved in prostate cancer growth. Radiopharmaceuticals: Drugs called radiopharmaceuticals can be used to target and eliminate cancer cells because they include a radioactive materials. Several radiopharmaceuticals, such as radium-223 and lutetium-177, are being developed and tested for prostate cancer. In order to treat or prevent disease, gene therapy have been use used which involves introducing or changing genes into a person's cells. For prostate cancer, several gene therapies are being developed, including therapies that target the androgen receptor pathway and therapies that use viruses to deliver therapeutic genes to cancer cells. Nanoparticles are tiny particles that can be used to deliver drugs directly to cancer cells. Several nanoparticle-based therapies, such as liposomes and polymer nanoparticles, are being developed and tested for prostate cancer. It's crucial to keep in mind that many of these treatments remain in the phase of development and research and might not be widely accessible over many years. We would look at some of these emerging therapies based on those related AR.

4.4.1. Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT)

The ADT lowers androgens, such as testosterone, which bind to and activate AR (Fujita & Nonomura, 2019). However, many of cancerous cells eventually are immune to ADT, and the formation of CRPC is often implicated with increased AR activity. ADT can substantially lower the number of available androgens in men with PCa, which in turn lowers AR's transcriptional activity (Ban et al., 2021). AR itself experiences numerous changes as the course of treatment progresses in response to these changes. Prostate cancer that is resistant to treatment and no longer relies on androgens for growth and survival is known as castration-resistant prostate cancer. By using androgen ablation therapy, CRPC is targeted. There are five different types of probable development mechanisms for CRPC. AR mutations, higher concentrations of co-activators, or enhanced synthesis of the potent androgen dihydrotestosterone all increase sensitivity to low levels of androgen in the blood in the hypersensitive pathway. The AR and androgen continue to be essential for the growth of tumors that use this mechanism. All of these ultimately lead to androgen-independent AR activation, which is the fundamental reason for anti-androgen therapy resistance. AR can be stimulated regardless of the existence of other hormones and medications, such as enzalutamide, bicalutamide, flutamide, and progesterone, and sustain its transcription activity to promote PCa carcinogenesis. The gene amplification and some acquire genetic abnormalities can cause this. The existing treatments for advanced prostate cancer comprise inhibitors of androgen synthesis that suppress the production of testosterone and/or DHT, as well as inhibitors of AR that prevent the binding of ligands at the LBD (El Kharraz et al., 2021). Nevertheless, LBD-specific therapies may become ineffective due to AR genetic variations and discrepancies. Because they both play crucial part in its gene transcription action and show reduced susceptibility to AR alternative splicing than the LBD, the DBD and NTD have therefore emerged as new targets for inhibition (Severson et al., 2022). By inhibiting DBD and NTD, it may be possible to enhance men’s longevity, living conditions, and acquired resistance to current therapies will all be improved.

4.4.2. Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibitors (ARSIs)

Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors are quite a type of medication utilized for treating PCa. Because AR signaling promotes tumor growth, medicines known as AR signaling inhibitors (ARSIs), which work to block AR signaling, have long been used in clinical settings. The majority of individuals treated with ARSIs develop a castration-resistant (CRPC) phenotype, which is unfortunate because the therapeutic efficacy of ARSIs is transient (Jamroze, Chatta & Tang, 2021). These drugs work by blocking the activity of androgen receptors, which are proteins found in prostate cells that bind to androgens and stimulate the growth and spread of prostate cancer. These drugs can be used alone or in combination with other treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, to treat prostate cancer. They can also be used to manage the symptoms of advanced prostate cancer. There are several types of androgen receptor signaling inhibitors, including: Anti-androgens: These drugs impair androgen from forming complex to its receptors, preventing the cancer cells from receiving the signal to grow and divide. Examples include bicalutamide, flutamide, and nilutamide. GnRH agonists: These drugs reduce the production of androgens by the testes by inhibiting the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. This causes reduction in testosterone levels in the body, which can slow the growth of PCa. Examples include leuprolide and goserelin. CYP17 inhibitors: These drugs block an enzyme called CYP17, which is involved in the production of androgens in the adrenal gland and in the PCa cells themselves. Examples include abiraterone acetate. Androgen receptor antagonists: These drugs block the activity of androgen receptors directly, preventing them from stimulating the growth of PCa cells.

The biotransformation of androgens in the body is the foundation that drives the creation of medications for PCa (Takayama, 2018). Androgens are synthesized from cholesterol, which is converted into pregnenolone and then into various hormones, including DHEA, androstenedione, and testosterone (Zhang et al., 2022). Enzymes involved in androgen synthesis include CYP11A1, 3β-HSD, and CYP17A1. DHEA biogenesis from cholesterol is crucial in the treatment of PCa individuals who may have rising androgen levels and overactive AR because DHEA is a crucial forerunner in androgen biosynthetic pathways in the prostate. Abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide are drugs recommended by the NCCN for PCa treatment and act on the androgen axis by targeting androgen metabolism pathways and synthesis (Zhang et al., 2022). These medications, renowned as ARSI, are used to block pathways, restore DHEA levels in the body, and impede AR signaling.

The enzyme-selective Abiraterone is a CYP17A1 irrevocable blocker that has received FDA approval that efficiently prevents androgen synthesis in the adrenal gland, testis, and PCa. When Abiraterone is administered with prednisone to reduce adverse reactions caused by the inhibition of corticosterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone. According to medical findings, those with metastatic CRPC who take abiraterone and prednisone together have longer overall survival times and disease-free survival times. However, alterations in androgen synthesis and metabolic pathways eventually lead to the development of rebellion to abiraterone. The de novo synthesis of androgens is activated by CYP17A1 increased expression and mutation, which also raises DHEA levels in tumors. Abiraterone rebellion is brought on by the abnormal expression of 3-HSDs and AKR1C3, which boost the "backdoor pathway" and "alternative pathway" of androgen formation, respectively, while reducing the metabolic activity of the active form of androgens by the glucuronidation pathway. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), pregnenolone, and other hormones upstream of P450c17 build up as a result of abiraterone's inhibitory activity of enzyme activity, which encourages the improvement of the "backdoor pathway" of androgen synthesis and also activates mutated AR. Furthermore, the development of truncated androgen receptor variants (such as AR-V7), as well as the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ErbB2 pathways, also contribute to the resistance of abiraterone.

Apalutamide is a new generation AR inhibitor approved for nmCRPC with improved CNS safety compared to enzalutamide. Its mechanism involves inhibiting AR nuclear translocation and binding to AREs. Apalutamide resistance is caused by AR mutations, splicing variants, and PI3K pathway activation. Darolutamide, an AR inhibitor that is oral and non-steroidal, inhibits AR function and cell growth in PCa without crossing the BBB, resulting in fewer CNS side effects. Studies on darolutamide resistance are limited, but there is evidence of cross-resistance with other AR inhibitors and significant inhibition of AR-mutated variants. Enzalutamide is an FDA-approved second-generation androgen receptor antagonist used to treat CRPC and non-metastatic CRPC. The drug works by preventing the nuclear translocation of stimulated AR, which prevents it from being localized to AREs, and inducing apoptosis and inhibiting CRPC cell proliferation. Despite its effectiveness, patients may develop resistance to enzalutamide. Enzalutamide resistance may be due to various mechanisms, such as changes in AR structure or quantity, over-activation of GR, activation of the Wnt pathway and Warburg effect, autophagy inhibition, and microRNA-mediated gene expression activation, leading to neuroendocrine trans-differentiation of CRPC cells. Most of these AR-targeted treatments concentrate on the LBD. AF-1, which is necessary for AR transcriptional activity, is present in the NTD could be prospective target. The first androgen receptor amino-terminal domain inhibitor is EPI-001 (Crona & Whang, 2017). EPI-001 is an AR antagonist that was developed by Marianne Sadar and Raymond Andersen with the goal of creating new antiandrogens for the treatment of CRPC. It is a group of stereoisomers and analogues that inhibits protein-protein interactions required for AR transcriptional activity by binding covalently to the AR's NTD. This is in contrast to other antiandrogens that compete for androgen binding and activation by binding to the C-terminal containing the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of the androgen receptor (AR). EPI-001 type compounds may be helpful in the management of advanced PCa that is resistant to traditional anti-androgens like enzalutamide due to their distinct mode of action.

4.4.3. Combinational Therapies

There is a proven substantial correlation between the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and AR signaling in PCa (Tortorella et al., 2023). Combination therapy targeting these pathways has shown promising results in preclinical and clinical studies. One potential combination therapy for PCa is the use of AR inhibitors such as enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate, in combination with PI3K inhibitors such as buparlisib or idelalisib. The combination of these drugs has been shown to have a synergistic effect in preclinical studies, resulting in decreased proliferation of cancer cells and increased apoptosis.

Table 1 lists some of these dual-targeting combination therapies. In a preclinical study, researchers found that combining an AKT inhibitor and an anti-androgen resulted in prolonged stabilization of the disease in a CRPC model (Thomas et al., 2013). The AKT inhibitor AZD5363 showed anticancer activity and induced apoptosis in PCa cell lines expressing AR. However, after about 30 days of treatment, increasing PSA levels signaled AZD5363 resistance. It was discovered that AZD5363 enhanced AR transcriptional activity and AR-dependent gene expression, such as PSA and NKX3.1 (Toren et al., 2015). Combining AZD5363 with the antiandrogen bicalutamide prevented these side effects and prolonged the inhibition of tumor growth and stabilized PSA in CRPC in vivo (Thomas et al., 2013).

The concomitant inhibition of uncontrolled cell growth together with the induction of death were also observed in vitro (Toren et al., 2015). Another approach is to target both AR and PI3K pathways with a single drug. For example, a novel drug called AZD5363 has been developed that inhibits both PI3K and AKT, a downstream effector of PI3K, as well as AR signaling. This drug has shown promising results in preclinical studies, and is currently being evaluated in clinical trials. It is important to note that combination therapy targeting AR and PI3K pathways may also have increased toxicity compared to single agent therapy. Thus, careful patient selection and monitoring are essential to ensure the safety and efficacy of these treatments. Overall, combinational therapies for prostate cancer offer a promising approach to improving patient outcomes. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal combination of therapies and identify biomarkers that can predict treatment response and guide personalized treatment strategies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, AR is important in the onset and advancement of PCa, and targeting it has proven to be an effective strategy for treating the disease. Combining multiple diagnostic strategies, such as measuring AR and PSA levels, may improve prostate cancer detection accuracy. More study is necessary to fully comprehend the intricate mechanisms of AR in PCa and to create new early detection diagnostic strategies. Resistance to androgen deprivation therapy is also a major challenge, and new strategies are required to target AR in advanced stages of PCa. Further research should be conducted to identify additional genetic variations that may impact AR activity and contribute to prostate cancer susceptibility, also to develop new therapies that can target the AR signaling pathway and over-come resistance to existing anti-androgen therapies. Combination pharmaceuticals are currently being used to treat PCa as they have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in clinical trials. However, more investigation is necessary to confirm the long term protection and effectiveness of these combinations, uncover biomarkers that can predict therapy response, and optimise drug dosages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.O.O. and S.Z.; Literature search, E.C.A. and C.C.E.; validation, E.C.A., C.C.E., and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, O.O.O.; supervision, O.O.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contribution to the work and as well approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that no conflict of interest exist.

Abbreviations

| ADT |

Androgen deprivation therapy |

| Akt |

Akt serine/threonine kinase |

| AR |

Androgen receptor |

| ARSIs |

Androgen signalling inhibitors |

| CRPC |

Castration resistant prostate cancer |

| DHT |

Dihydrotestosterone |

| HSP |

Heat shock protein |

| PI3K |

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| mCRPC |

Metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer |

| mTOR |

Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| SHBG |

Sex hormone binding globulin |

References

- Aaron, L., Franco, O.E. & Hayward, S.W. (2016) Review of Prostate Anatomy and Embryology and the Etiology of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Urologic Clinics of North America. 43 (3), 279–288. [CrossRef]

- Alabi, B.R. , Liu, S. & Stoyanova, T. (2022) Current and emerging therapies for neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 108255.

- Alemany, M. (2022) The Roles of Androgens in Humans: Biology, Metabolic Regulation and Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (19), 11952. [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S. , Almatroudi, A., Alrumaihi, F., Makki Almansour, N., Aldakheel, F.M., Rather, R.A., Afroze, D. & Rah, B. (2021) Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in prostate cancer: its implications in diagnostics and therapeutics. American Journal of Translational Research. 13 (4), 3868–3889.

- Baca, S.C. , Singler, C., Zacharia, S., Seo, J.-H., Morova, T., et al. (2022) Genetic determinants of chromatin reveal prostate cancer risk mediated by context-dependent gene regulation. Nature Genetics. 54 (9), 1364–1375. [CrossRef]

- Badal, S. , Aiken, W., Morrison, B., Valentine, H., Bryan, S., Gachii, A. & Ragin, C. (2020) Disparities in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates: Solvable or not? The Prostate. 80 (1), 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Ban, F. , Leblanc, E., Cavga, A.D., Huang, C.-C.F., Flory, M.R., Zhang, F., Chang, M.E.K., Morin, H., Lallous, N., Singh, K., Gleave, M.E., Mohammed, H., Rennie, P.S., Lack, N.A. & Cherkasov, A. (2021) Development of an Androgen Receptor Inhibitor Targeting the N-Terminal Domain of Androgen Receptor for Treatment of Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancers. 13 (14), 3488. [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, R. , Garisto, J., Bove, P., Mottrie, A. & Rocco, B. (2021) Perioperative Outcomes Between Single-Port and “Multi-Port” Robotic Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Where do we stand? Urology. 155, 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Bosland, M.C. , Nettey, O.S., Phillips, A.A., Anunobi, C.C., Akinloye, O., Ekanem, I.A., Bassey, I.E., Mehta, V., Macias, V., Kwast, T.H. & Murphy, A.B. (2021) Prevalence of prostate cancer at autopsy in Nigeria—A preliminary report. The Prostate. 81 (9), 553–559. [CrossRef]

- Brtko, J. (2021) Thyroid hormone and thyroid hormone nuclear receptors: History and present state of art. Endocrine Regulations. 55 (2), 103–119.

- Bryant, C.M., Henderson, R.H., Nichols, R.C., Mendenhall, W.M., Hoppe, B.S., et al. (2021) Consensus Statement on Proton Therapy for Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Particle Therapy. 8 (2), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Budipitojo, T. , Mahesty, S.R.N., Padeta, I. & Khasanah, L.M. (2020) Reproductive Glands of the Sunda Porcupine (Hystrix Javanica).

- Carpenter, V. , Saleh, T., Min Lee, S., Murray, G., Reed, J., Souers, A., Faber, A.C., Harada, H. & Gewirtz, D.A. (2021) Androgen-deprivation induced senescence in prostate cancer cells is permissive for the development of castration-resistance but susceptible to senolytic therapy. Biochemical Pharmacology. 193, 114765. [CrossRef]

- CDC (2023) What Is Prostate Cancer? | CDC. 2023. Prostate Cancer. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/what-is-prostate-cancer.htm [Accessed: 13 February 2023].

- Chu, J.J. & Mehrzad, R. (2023) The biology of cancer. In: The Link Between Obesity and Cancer. Elsevier. pp. 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Conteduca, V., Gurioli, G., Brighi, N., Lolli, C., Schepisi, G., Casadei, C., Burgio, S.L., Gargiulo, S., Ravaglia, G. & Rossi, L. (2019) Plasma androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Cancers. 11 (11), 1719.

- Crawford, E.D. , Schellhammer, P.F., McLeod, D.G., Moul, J.W., Higano, C.S., Shore, N., Denis, L., Iversen, P., Eisenberger, M.A. & Labrie, F. (2018) Androgen receptor targeted treatments of prostate cancer: 35 years of progress with antiandrogens. The Journal of urology. 200 (5), 956–966.

- Crona, D. & Whang, Y. (2017) Androgen Receptor-Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms Involved in Prostate Cancer Therapy Resistance. Cancers. 9 (12), 67. [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.D. (2022) Triplet therapy for prostate cancer. The Lancet. 399 (10336), 1670–1671. [CrossRef]

- El Kharraz, S., Dubois, V., Royen, M.E., Houtsmuller, A.B., Pavlova, E., et al. (2021) The androgen receptor depends on ligand-binding domain dimerization for transcriptional activation. EMBO reports. 22 (12). [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, J. , Alajati, A., Kubatka, P., Giordano, F.A., Ritter, M., Costigliola, V. & Golubnitschaja, O. (2022) Prostate cancer treatment costs increase more rapidly than for any other cancer—how to reverse the trend? EPMA Journal. 13 (1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, É. , Ould Madi Berthélémy, P., Cottard, F., Angel, C.Z., Schreyer, E., Ye, T., Morlet, B., Negroni, L., Kieffer, B. & Céraline, J. (2022) Androgen receptor-mediated transcriptional repression targets cell plasticity in prostate cancer. Molecular Oncology. 16 (13), 2518–2536. [CrossRef]

- Estébanez-Perpiñá, E., Arnold, L.A., Nguyen, P., Rodrigues, E.D., Mar, E., Bateman, R., Pallai, P., Shokat, K.M., Baxter, J.D., Guy, R.K., Webb, P. & Fletterick, R.J. (2007) A surface on the androgen receptor that allosterically regulates coactivator binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (41), 16074–16079. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q. & He, B. (2019) Androgen receptor signaling in the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 9, 858.

- Fernandez-Perez, M.P. , Perez-Navarro, E., Alonso-Gordoa, T., Conteduca, V., Font, A., et al. (2023) A correlative biomarker study and integrative prognostic model in chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with enzalutamide. The Prostate. 83 (4), 376–384. [CrossRef]

- Foley, G.R. , Marthick, J.R., Ostrander, E.A., Stanford, J.L., Dickinson, J.L. & FitzGerald, L.M. (2023) Association of a novel BRCA2 mutation with prostate cancer risk further supports germline genetic testing. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 180, 155–157. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K. & Nonomura, N. (2019) Role of Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer: A Review. The World Journal of Men’s Health. 37 (3), 288. [CrossRef]

- Gurung, P. , Yetiskul, E. & Jialal, I. (2021) Physiology, male reproductive system. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. p.

- Ha, H., Kwon, H., Lim, T., Jang, J., Park, S.-K. & Byun, Y. (2021) Inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen in the diagnosis and therapy of metastatic prostate cancer – a review of patent literature. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 31 (6), 525–547. [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, D.J. (2000) Androgen Physiology, Pharmacology, Use and Misuse. In: K.R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, M.R. Blackman, A. Boyce, G. Chrousos, et al. (eds.). Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA), MDText.com, Inc. p. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279000/.

- He, Y., Hooker, E., Yu, E.-J., Wu, H., Cunha, G.R. & Sun, Z. (2018) An Indispensable Role of Androgen Receptor in Wnt Responsive Cells During Prostate Development, Maturation, and Regeneration. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio). 36 (6), 891–902. [CrossRef]

- Hsing, A.W. , Gao, Y.-T., Wu, G., Wang, X., Deng, J., Chen, Y.-L., Sesterhenn, I.A., Mostofi, F.K., Benichou, J. & Chang, C. (2000) Polymorphic CAG and GGN repeat lengths in the androgen receptor gene and prostate cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in China. Cancer research. 60 (18), 5111–5116.

- Hu, L. , Fu, C., Song, X., Grimm, R., von Busch, H., et al. (2023) Automated deep-learning system in the assessment of MRI-visible prostate cancer: comparison of advanced zoomed diffusion-weighted imaging and conventional technique. Cancer Imaging: The Official Publication of the International Cancer Imaging Society. 23 (1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Jamroze, A., Chatta, G. & Tang, D.G. (2021) Androgen receptor (AR) heterogeneity in prostate cancer and therapy resistance. Cancer Letters. 518, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R., Woods-Burnham, L., Hooker Jr, S.E., Batai, K. & Kittles, R.A. (2021) Genetic contributions to prostate cancer disparities in men of West African descent. Frontiers in oncology. 11, 770500.

- Mahmoud, M.M. , Abdel Hamid, F.F., Abdelgawad, I., Ismail, A., Malash, I. & Ibrahim, D.M. (2023) Diagnostic Efficacy of PSMA and PSCA mRNAs Combined to PSA in Prostate Cancer Patients. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 24 (1), 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Manzar, N., Ganguly, P., Khan, U.K. & Ateeq, B. (2023) Transcription networks rewire gene repertoire to coordinate cellular reprograming in prostate cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 89, 76–91. [CrossRef]

- Mbemi, A. , Khanna, S., Njiki, S., Yedjou, C.G. & Tchounwou, P.B. (2020) Impact of Gene–Environment Interactions on Cancer Development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (21), 8089. [CrossRef]

- Messner, E.A. , Steele, T.M., Tsamouri, M.M., Hejazi, N., Gao, A.C., Mudryj, M. & Ghosh, P.M. (2020) The Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer: Effect of Structure, Ligands and Spliced Variants on Therapy. Biomedicines. 8 (10), 422. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, D.T., Lee, R.J., Stott, S.L., Ting, D.T., Wittner, B.S., Ulman, M., Smas, M.E., Lord, J.B., Brannigan, B.W., Trautwein, J., Bander, N.H., Wu, C.-L., Sequist, L.V., Smith, M.R., Ramaswamy, S., Toner, M., Maheswaran, S. & Haber, D.A. (2012) Androgen Receptor Signaling in Circulating Tumor Cells as a Marker of Hormonally Responsive Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2 (11), 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Mohler, J.L. , Antonarakis, E.S., Armstrong, A.J., D’Amico, A.V., Davis, B.J., et al. (2019) Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 17 (5), 479–505. [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.E. (2013) Chapter 8. Male Reproductive System. In: Endocrine Physiology. 4th edition. New York, NY, The McGraw-Hill Companies. p. accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=57307916.

- Narayanan, R. (2020) Therapeutic targeting of the androgen receptor (AR) and AR variants in prostate cancer. Asian Journal of Urology. 7 (3), 271–283. [CrossRef]

- Negri, A. , Marozzi, M., Trisciuoglio, D., Rotili, D., Mai, A. & Rizzi, F. (2023) Simultaneous administration of EZH2 and BET inhibitors inhibits proliferation and clonogenic ability of metastatic prostate cancer cells. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 38 (1), 2163242. [CrossRef]

- Nevedomskaya, E., Baumgart, S.J. & Haendler, B. (2018) Recent Advances in Prostate Cancer Treatment and Drug Discovery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (5), 1359. [CrossRef]

- Oladoyinbo, C.A. , Akinbule, O.O., Bolajoko, O.O., Aheto, J.M., Faruk, M., Bassey, I.E., Odedina, F., Ogunlana, O.O., Ogunsanya, M., Suleiman, A.M., Obialor, S. & Gali, R. (2020) Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer in West African Men: The Prostate Cancer Transatlantic Consortium (CaPTC) Cohort Study. Cancer Health Disparities. 4. https://www.companyofscientists.com.

- Osadchuk, L.V. & Osadchuk, A.V. (2022) Role of CAG and GGC Polymorphism of the Androgen Receptor Gene in Male Fertility. Russian Journal of Genetics. 58 (3), 247–264. 3). [CrossRef]

- Peyman, T. (2010) (PDF) Androgen Receptor Modulation by non-Androgenic Factors and the Basal Transcription Factor TAF1. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260403239_Androgen_Receptor_Modulation_by_non-Androgenic_Factors_and_the_Basal_Transcription_Factor_TAF1 [Accessed: 13 February 2023].

- Pungsrinont, T. , Kallenbach, J. & Baniahmad, A. (2021) Role of PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway as a Pro-Survival Signaling and Resistance-Mediating Mechanism to Therapy of Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (20), 11088. [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, W., Lubkowski, M. & Lubkowska, A. (2022) Heat Shock Proteins in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (2), 897. [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P. (2019). Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World journal of oncology. 10 (2), 63–89. [CrossRef]

- Rey, R.A. (2021) The role of androgen signaling in male sexual development at puberty. Endocrinology. 162 (2).

- Rosellini, M. , Santoni, M., Mollica, V., Rizzo, A., Cimadamore, A., Scarpelli, M., Storti, N., Battelli, N., Montironi, R. & Massari, F. (2021) Treating Prostate Cancer by Antibody-Drug Conjugates. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (4), 1551. [CrossRef]

- Severson, T. , Qiu, X., Alshalalfa, M., Sjöström, M., Quigley, D., Bergman, A., Long, H., Feng, F., Freedman, M.L., Zwart, W. & Pomerantz, M.M. (2022) Androgen receptor reprogramming demarcates prognostic, context-dependent gene sets in primary and metastatic prostate cancer. Clinical Epigenetics. 14 (1), 60. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, P.L., Jivan, A., Dollins, D.E., Claessens, F. & Gewirth, D.T. (2004) Structural basis of androgen receptor binding to selective androgen response elements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (14), 4758–4763. [CrossRef]