1. Introduction

Bone infections, such as osteomyelitis, remain a major clinical challenge in the field of bone surgery due to their serious rate of mortality and morbidity [

1]. The most common causative species of surgical site infections and medical device-associated infections are the opportunistic Gram-positive staphylococci (≃75% of cases), particularly

Staphylococcus aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis [

2,

3]. In terms of pathogenesis, osteomyelitis is complex and varied, with bacteria reaching the bone in two ways: (i) endogenously via blood or originating from another nearby or distant source of infection (hematogenous osteomyelitis); and (ii) exogenously through direct inoculation or contamination of an open trauma or post-surgical procedures [

4].

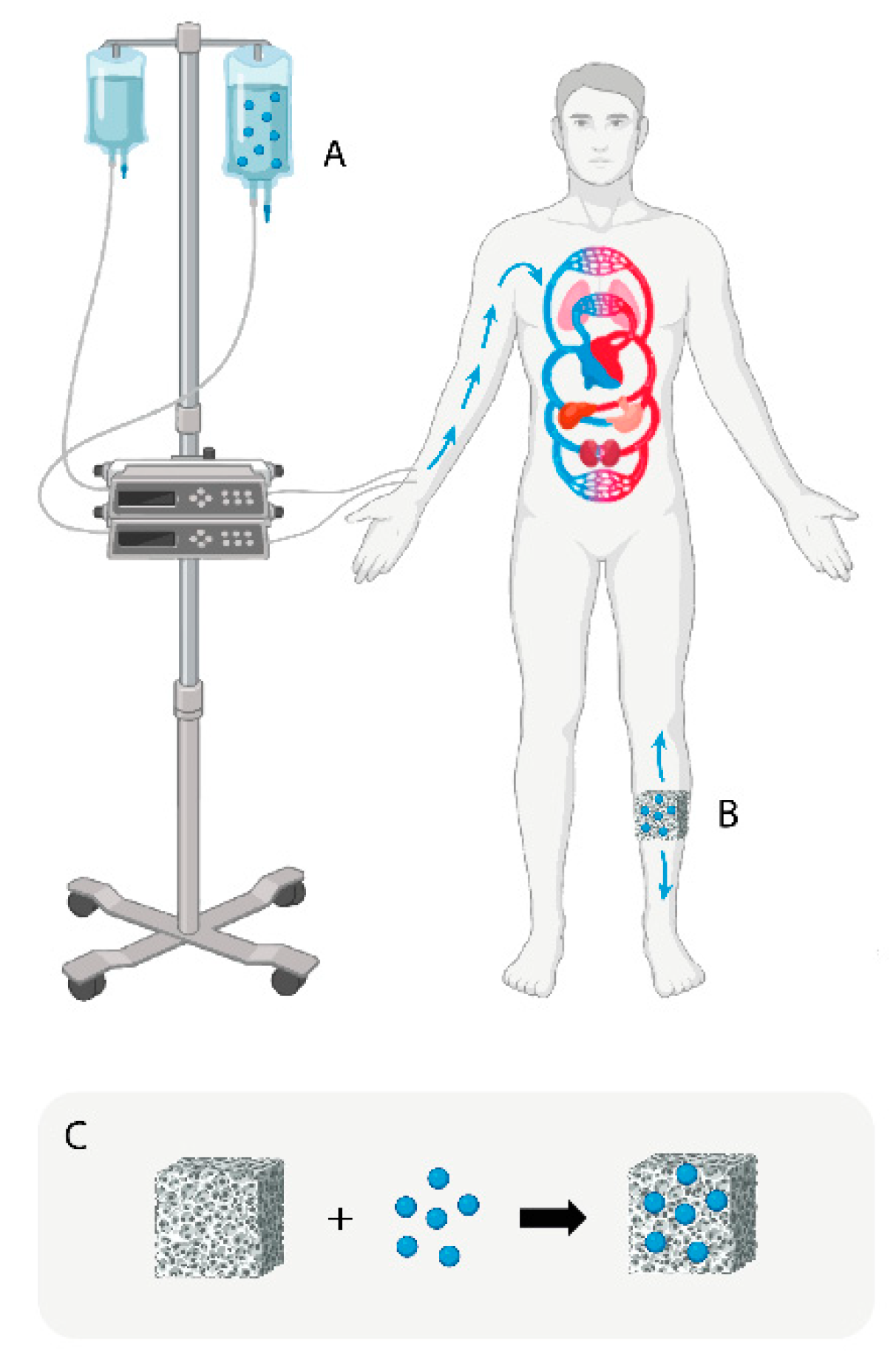

The traditional treatment for chronic osteomyelitis includes extensive debridement of the infected bone, filling of the dead space, and systemic (intravenous) and local administration of antibiotics over long periods of time [

5,

6] (

Figure 1A). In more specific cases such as infections associated with the implantation of prosthetic materials (hip, knee, and shoulder prosthesis) or osteosynthesis materials for fracture stabilization (plates, screws, pins, etc.), the treatment requires as a first step the removal of the implant and at the same time maintaining intravenous and local antibiotherapy until normalization of biochemical parameters and performing osteoarticular reconstruction surgery as required by the case [

5].

Another strategy for the local treatment of chronic bone infections has been based on the administration of antibiotics by means of implantation of drug delivery systems (DDSs) at the site of infection (

Figure 1B). One of the most used DDSs for the treatment of osteomyelitis have been antibiotic-loaded poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) beads [

7,

8]. PMMA, also referred as (acrylic) bone cement, is a non-resorbable biomaterial that works by slowly releasing antibiotics (generally gentamicin and vancomycin) over time, which can help to eradicate the bacteria causing the infection [

9,

10]. Despite having been used for decades in clinical practice, PMMA beads are far from being an ideal antibiotic carrier. The non-degradability of this biomaterial requires a second surgery to remove the beads 2 or 3 weeks after implantation [

11].

Vancomycin (Van) is the most commonly used antibiotic in treatment of infections in arthroplasty surgery and chronic osteomyelitis of any etiology [

10]. This glycopeptide antibiotic acts primarily as a cell wall synthesis inhibitor in susceptible organisms. It binds rapidly and irreversibly to the cell wall of susceptible bacteria, inhibiting the synthesis of peptidoglycan, which forms the structure of the cell wall [

12,

13].

Polycaprolactone (PCL) is a synthetic polymer that has been commonly used in 3D-printing applications as a scaffolding component for bone and cartilage reconstruction [

14,

15,

16]. Among its main advantages, we find its biocompatibility, biodegradability, good mechanical properties, and its low melting temperature (≃60 °C), which makes it more versatile than other synthetic polymers used for 3D-printing applications [

17]. However, the 3D-printing temperatures used to fabricate well-defined scaffolds with controlled architecture are around 120-160°C, which makes it impossible to combine them with cells, growth factors, or other bioactive molecules during the printing process [

18,

19]. On the other hand, PCL lacks natural motifs that provide specific binding sites for cells that facilitate tissue integration [

20]. Because of this, different strategies have been developed to overcome PCL native hydrophobicity, such as surface modification by NaOH treatment, or by its combination with other synthetic or naturally derived materials (hydrogels) to create hybrid scaffolds with enhanced properties [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Synthetic and naturally-derived hydrogels have been widely used for different biomedical applications due to their ability to encapsulate cells, drugs, growth factors, or other bioactive molecules [

25,

26]. Naturally-derived hydrogels include principally collagen, chitosan, alginate, silk fibroin, hyaluronic acid, and hydrogels derived from decellularized tissues [

27].

Chitosan (CS) is a naturally-derived semicrystalline polymer that is obtained by partial deacetylation of chitin under alkaline conditions [

28]. It is one of the most widely used materials to prepare hydrogels due to its excellent biocompatibility, nontoxicity, and biodegradability [

29,

30]. However, CS hydrogels present several challenges on their unstable structures with large-sized pores, weak formability, and low mechanical strength under physiological conditions, limiting their further utilization [

31,

32]. For this reason, they have been combined with curable polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and polylactic acid (PLA), which provide the scaffolds basic mechanical support [

33,

34].

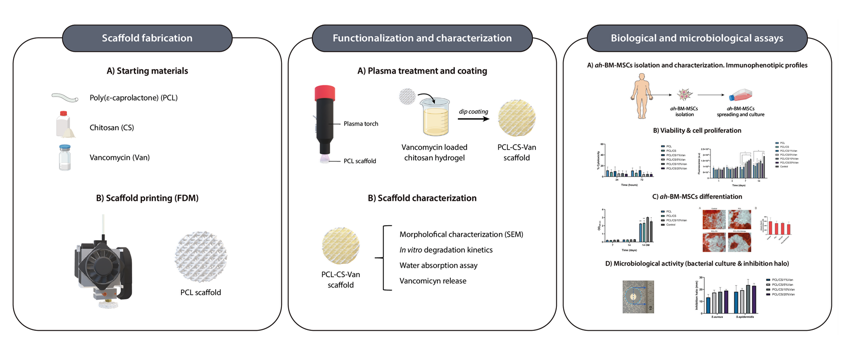

The fabrication of hybrid materials that combine natural and synthetic polymers is a promising approach to creating new scaffolds that combine the intrinsic advantages of both materials and meet several requirements, such as biological activity, mechanical strength, ease of fabrication, and controlled degradation [

35]. In this work, we focus on the fabrication of a novel hybrid 3D-printed scaffold based on PCL and a CS hydrogel loaded with different vancomycin concentrations (1, 5, 10, and 20%) as a drug delivery system to evaluate its antimicrobial efficacy against

S. aureus and

S. epidermidis. In addition, we propose a novel method for improving the adhesion of hydrophobic polymers (PCL) to hydrogels using two different cold plasma treatments. The obtained scaffolds combine the natural biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antibacterial properties of CS with the excellent mechanical properties of PCL. The morphological properties of the scaffolds were characterized by optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), showing that the CS/Van hydrogel successfully coated the PCL matrix homogeneously after the plasma treatment. The antibacterial efficacy of the scaffolds was tested against

Staphylococcus aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis, and vancomycin release was studied at different time periods by means of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPCL). Finally, we evaluated the possible systemic adverse effects of scaffolds at the cellular level by analyzing the viability, proliferation, and differentiation of a population of adult human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (

ah-BM-MCS).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL) 3D-printing filament (molecular weight: 50000 g/mol) was purchased from 3D4makers (Haarlem, The Netherlands). Chitosan (#448869, 75-85% deacetylated, low molecular weight), acetic acid, and NaOH were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA) and used as received. Vancomycin hydrochloride was purchased from Lab. Reig Jofre S.A. (Barcelona, Spain).

Staphylococcus epidermidis (CECT 231) and Staphylococcus aureus (CECT 239) strains were provided by the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT) (Paterna, Valencia, Spain). Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA), and buffered peptone water were purchased from Scharlau (Barcelona, Spain).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fabrication of porous polycaprolactone/chitosan scaffolds loaded with vancomycin

2.2.1.1. Design and fabrication of 3D-printed PCL scaffolds with controlled porosity using the Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) method

The scaffolds were designed with the software REGEMAT 3D Designer v1.4.4 and manufactured using a REGEMAT 3D Bio V1

® bioprinter (REG4Life, REGEMAT 3D, Granada, Spain) equipped with a glass bed and a thermoplastic extruder with a 0,4 mm diameter nozzle. The scaffolds were designed with the following parameters:

scaffold size 1.50 x 20 x 20 mm (height, width, length),

pore size 200 µm,

layer height 0,25 mm,

perimeters 0,

solid bottom/top layers 0,

infill pattern triangular; and manufactured using a medical-grade PCL filament printed at 160ºC with an infill speed of 11 mm/s. As described in a previous work, an 8-mm biopsy punch was used to prepare defined and reproducible scaffolds to enhance the reproducibility of the experiments and reduce the variability between the samples, obtaining disks-shaped scaffolds of 8 x 1.50 mm (diameter, height) (

Figure 2A) [

18]. In addition, non-porous (solid) PCL scaffolds of 12 x 12 x 1.50 mm (width, length, height) were printed in order to avoid porosity interfering with some of the experiment results (

Figure 2B). Porous disk-shaped scaffolds were characterized and used for all biological and microbiological experiments and solid scaffolds were only used to evaluate the effect of cold plasma treatment on the adhesion of CS/Van hydrogel to the PCL matrix (

Wettability assay), as it was noticed that porosity interfered in the experiment results.

2.2.1.2. Vancomycin-loaded chitosan hydrogels preparation

The chitosan hydrogels were prepared by dissolving low molecular weight chitosan at a concentration of 4% (w/v) in demineralized water containing 1.5% (v/v) acetic acid. The solutions were mechanically stirred for 24 h (250 rpm) and vancomycin was added to the chitosan hydrogels in a content of 1, 5, 10, and 20% (w/w of chitosan). After 24 h, the solutions were centrifuged (3000 rpm, 1 h) to remove air bubbles.

2.2.1.3. Hybrid scaffolds preparation

The 3D-printed PCL scaffolds were dip-coated in the chitosan hydrogel and left to dry overnight. Then, the scaffolds were neutralized in a 1 M NaOH solution for 2 hours and rinsed three times with distilled water to remove residual acids. The whole process was performed in a laminar flow cabinet to avoid sample contamination.

Preliminary tests showed that the chitosan coating remained firmly adhered to the porous PCL scaffolds, as it was trapped between the 3D-printed strands. However, that was not the case for solid PCL scaffolds, which repelled the chitosan coating as seen in

Figure 3C. This could be due to the fact that PCL is a hydrophobic polymer, which makes it difficult to adhere to hydrogels with more than 90% water content.

Plasma treatments have been recently used to lower the hydrophobicity of polymer surfaces by forming Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [

36]. These newly formed reactive species generate hydrophilic groups (hydroxyl or carboxylic) on the polymer surface that can interact with the hydrogels [

37]. Even if the plasma treatment was not necessary for porous scaffolds, two different plasma technologies were tested on the surface of solid PCL scaffolds: (i) a cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet developed in GREMI-CNRS consisting of a Plasma Gun which is a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma, helium feeded and powered by microsecond voltage pulse [

38] (

Figure 3A), and (ii) a home-made torch with a piezoelectric plasma generator (CeraPlas

®) developed by TDK Electronics GmbH & Co [

39] (

Figure 3B). This technology is based on a piezo ceramic component and a driving circuit that allows generating cold atmospheric plasma. After being exposed for 30 s to plasma treatments with 5 mm gap, the PCL scaffolds were dip-coated in the chitosan hydrogels and left to dry overnight. As can be seen in

Figure 3D, the CS hydrogel was not repelled by the scaffold, showing a homogeneous distribution.

In order to determine the amount of chitosan adhered to the scaffolds, the weight of the PCL scaffolds was compared to the weight of PCL/CS/Van scaffolds after the coating process. After weighing the scaffolds (n=10) in an analytical balance, an increment from 33,34 ± 0,34 mg (native PCL) to 41,16 ± 1,01 mg (PCL/CS/Van scaffolds) was observed. No significant differences were obtained between the weight of PCL/CS scaffolds at different vancomycin concentrations (data not shown).

2.3. Characterization of the 3D printed scaffolds

2.3.1. Morphological characterization of the 3D-printed scaffolds

The morphological characterization of the 3D-printed scaffolds was carried out by means of a digital camera coupled to a stereomicroscope. The surface morphology of the scaffolds was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; model JEOL-6100, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Prior to visualization, the scaffolds were mounted on aluminum stubs with conductive paint and were sputter-coated with platinum (10 mA, 120 s). SEM micrographs were obtained at magnifications of x20 and x45 under an accelerating voltage of 15-20 kV and a working distance of 4-5 mm.

2.3.2. Wettability assay

Static water contact angle (WCA) measurements were performed on a drop shape analyzer (DSA100S KRÜSS GmbH) to assess the effect of cold plasma treatment on PCL hydrophobicity. The water droplet volume was set to 1 µL and the deposit speed at 2,67 µL/s. Briefly, solid PCL scaffolds (n = 3) were treated with a cold atmospheric plasma jet (Plasma 1) and with a home-made torch with a piezoelectric plasma generator (Plasma 2) (

Figure 3). Three untreated scaffolds were used as control. Each measurement was performed in triplicate in three different scaffolds for better statistical significance.

2.3.3. In vitro degradation kinetics

The scaffold degradation was assessed

in vitro by measuring the weight loss of the scaffolds at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. Briefly, PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were weighed (W

0, initial weight) and subsequently immersed in eppendorf tubes containing 1 mL of complete growth medium (DMEM). Then, the scaffolds were incubated at 37°C, in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere and 95% of relative humidity. At different time periods, the scaffolds were recovered from medium, sightly wiped with filter paper, and re-weighed (W

d, final weight). The weight loss (WL) was calculated by applying the following equation:

where W

0 and W

d indicate the weight of the scaffold before and after the scheduled immersion time, respectively.

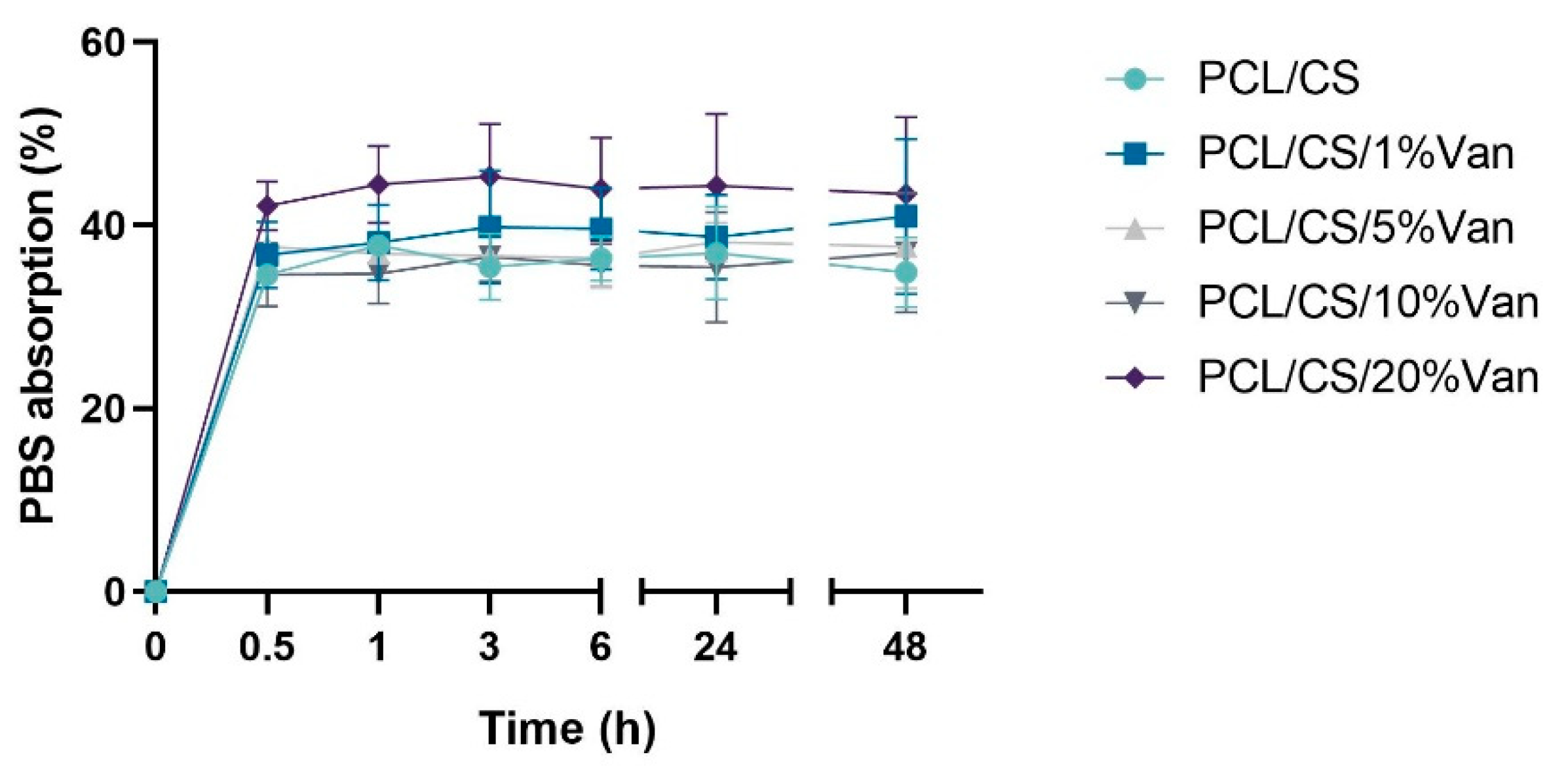

2.3.4. Water absorption assay

The swelling behavior of PCL/CS/Van scaffolds was tested in PBS solutions of pH 7.4. Three PCL/CS/Van scaffolds of known weight were put into stainless steel baskets in order to prevent scaffolds from floating. At different time points (0.5, 1, 3, 6, 24, 48 h), the scaffolds were collected and sightly wiped with filter paper before being weighted. Water absorption was calculated using the following equation:

where

if the weight of the scaffolds at time

t, and

is the initial weight of the dry scaffolds.

2.3.5. Vancomycin release quantification

Vancomycin-loaded chitosan scaffolds were immersed into 1,5 mL eppendorf tubes containing 1 mL Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) medium at 37°C in darkness. At predetermined time points (1h, 3h, 6h, 24h, 48h, 72h, 7d, and 14d), the medium was collected, and fresh PBS was refilled accordingly. The vancomycin concentration was measured by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent 1200 series, Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) with diode array (DAD) and fluorescence (FLD) detector, equipped with a Vydac 218TP C18 column (250x4.6 mm, 5 μm, Avantor®, Pennsylvania, USA). The analysis was performed under isocratic conditions (0.8 mL/min) with 89% ammonium phosphate 0.5 M and 11% acetonitrile as mobile phase. Prior to the measurements, a calibration curve of vancomycin in PBS was determined by measuring absorbance values of stock solutions of vancomycin from 100 to 0,5 μg/mL at 282 nm (linear range 12.4 to 0.5 μg/mL; R2 > 0.998).

2.4. Evaluation of antimicrobial properties

2.4.1. Bacterial culture

Strains of S. epidermidis and S. aureus were activated in TSB medium and incubated under aerobic conditions at 35 °C for 24 h. The bacteria cultures were preserved in TSA medium at 4 °C for more than 3 months. The working culture was daily prepared, transferring one colony from TSA to 10 mL of TSB, and incubated for 24 h at 35 °C.

2.4.2. Agar diffusion method

To evaluate the ‘‘release-killing’’ properties of the vancomycin-loaded chitosan coating, inhibition zone experiments were carried out. First, a suspension of 5.0 log10 colony forming units/mL (CFU/mL) was prepared for each microorganism (S. epidermidis and S. aureus) in TSB (2X). After that, aliquots of 100 µL of the bacterial suspension were added to well plates 6.0 mm in diameter containing TSA agar were prepared.

After drying for several minutes, the samples were placed in contact with the PCL/Chitosan/Van scaffolds and incubated overnight at 37°C. The inhibition halos were determined by means of a ruler at 24 h and 48 h. All tests were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Biological assays

2.5.1. Isolation, purification, characterization, and culture of adult human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (ah-BM-MSCs)

Multipotent a

h-BM-MSCs were isolated from bone marrow as previously described (additional information related to the applied methodology, cell isolation, culture, and expansion of

ah-BM-MSCs can be found in previous publications [

40,

41]). Briefly, bone marrow was collected from the iliac crest of three volunteer patients by direct puncture. Then, bone marrow aspirate was transferred into transfer bags containing heparin. The mononuclear cell fraction was obtained using Ficoll density gradient media and a cell-washing closed automated SEPAX

TM S-100 System (Biosafe, Eysines, Switzerland). After estimating the viability with trypan blue staining (#T8154; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), cells were plated out at a density of 3.75×10

5 ml in 75 cm

2 culture flasks (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) with 10 mL of basal culture growth medium (GM). The growth medium used was Dulbecco´s Minimum Essential Media (DMEM) (#31885-023, Gibco, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands), complemented with 10% (

v/v) inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (#F7524, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), and routine antibiotics such as Penicillin and streptomycin (100 U mL

-1 penicillin and 100 μg mL

-1 streptomycin) (#P4333, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) before incubating cells under standard conditions of normoxia (21% O

2), at 37°C and 5% CO

2. a

h-BM-MSCs in passages 3-5 were used for

in vitro experiments.

All biological experiments were in full compliance with the established regulations and the experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of UCAM-Universidad Católica de Murcia (Authorized nº CE051904) UCAM Ethics Committee (CE nº 052114/05.28.2222).

2.5.2. Immunophenotypic Profiles of ah-BM-MSC Cultures

Flow cytometry was used to characterize the isolated

ah-BM-MSCs (Beckman Dickinson & Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA; Software Navios) for mesenchymal (CD90, CD73, 105) and hematopoietic (CD34, CD45) markers as previously described [

40,

42,

43]. Before performing the

in vitro assays, single-cell suspensions obtained by culture trypsinization were labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: CD73-PE, CD90-APC, CD105-FITC, CD34-APC, and CD45-FITC (Human MSC Phenotyping Cocktail, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) in order to verify the purity of

ah-BM-MSCs populations (data not shown).

2.5.3. Cell seeding methods

For cell viability, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation assays, ah-BM-MSCs were seeded at the bottom of 24 WP at a density of 10x103 cells cm-2, and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were placed in 0,4 μm pore culture well inserts (Falcon®) to be in indirect contact with the culture. Cells seeded onto tissue culture-treated polystyrene wells (TCPS; Sigma-Aldrich, Corning, NY, USA) (without materials) were taken as positive control. The culture media was changed three times a week for all the experiments performed.

2.5.4. Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays

2.5.4.1. In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The cell viability of

ah-BM-MSCs was evaluated using LDH cytotoxicity detection kit (#11644793001, Roche Diagnostics, Roche. Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) after placing PCL/CS/Van scaffolds in indirect contact with cells for 24 and 72h. Before performing the assay, it is important to determine the optimal cell concentration for the cell line used, as different cell types may contain different amounts of LDH. In general, we choose the concentration at which the difference between the low and high control is at a maximum. For our culture of a

h-BM-MSCs, the optimal cell concentration to be used for the subsequent experiment was found to be 3 x 10

4 cells/well for 24 WP (

Figure 4).

24h after seeding ah-BM-MSCs on 24 WP, the culture medium was replaced by fresh assay medium containing 1% FBS to remove LDH activity released from the cells during the incubation step. Then, the PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were placed in indirect contact with cells using 0.4 μm pore culture well inserts and the LDH activity was assessed at 24 and 72h. Cells growing on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) plates without PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were used as low control (spontaneous LDH release) and cells cultured with assay medium containing 1% Triton X-100 solution were used as high control (maximum LDH release). At different time points, 100 μL aliquots of each well were transferred to an optically clear flat-bottomed 96-well plate followed by the addition of 100 μL of the reaction mixture. After 30 min incubation at RT, the absorbance was read directly in a Spectramax iD3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) at 490 nm.

2.5.4.2. Cellular metabolic activity assay

The cellular metabolic activity of ah-BM-MSCs grown in the presence of PCL/CS scaffolds loaded with different vancomycin concentrations was evaluated using the AlamarBlue® assay (#DAL1100, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on days 1, 3, 7, 14 after seeding. Cells growing onto TCPS (without PCL/CS/Van scaffolds) were used as control. Briefly, at different time periods, the inserts containing PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were temporarily removed (prior to the incubation step), and fresh medium (1 mL) containing 10% (v/v) AlamarBlue® reagent was added to each well. Then, the plate was incubated in darkness (wrapped with aluminum foil) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere with 95% of relative humidity for 4 h. Finally, 150 μL aliquots of each well were transferred to a black-walled 96-well plate and fluorescence was measured in a Spectramax iD3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 590 nm, respectively.

2.5.5. Osteoblastic Differentiation Assays

2.5.5.1. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity

The ALP activity of ah-BM-MSCs was assessed at 7 and 14 days after seeding the cells in indirect contact with PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds using an Alkaline Phosphatase Detection Kit (#SCR004, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). At each time period, cells were detached and an aliquot of 1,5 × 104 cells (per sample) was treated following the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction affords a yellow-colored by-product that is proportional to the amount of ALP present within the reaction. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm in a Spectramax iD3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA).

2.5.5.2. In vitro mineralization assay

The in vitro mineralization was evaluated using an Osteogenesis Assay Kit (#ECM815; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) 21 days after seeding ah-BM-MSCs in the presence (indirect contact) of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds. Briefly, the ah-BM-MSCs were fixed with 10% formaldehyde, stained with Alizarin Red Stain Solution, and visualized using an optical microscope (Axio Vert.A1, ZEISS, Germany) coupled to a digital camera (Axiocam 305 color, ZEISS, Germany). Then, the samples were treated following the manufacturer’s instructions to quantify matrix mineralization and the optical density (OD) was measured in a Spectramax iD3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) at 405 nm.

2.6. Statistic

All data were represented as mean ± SD, n=3. The statistical significance was determined by a two-way ANOVA using GraphPrism 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA) for Windows. Comparison between groups was evaluated with the t-test, being the significance level p < 0,05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of the 3D-printed scaffolds

3.1.1. Morphological characterization of the 3D printed scaffolds

Microstructural examination of the scaffolds morphology by SEM imaging showed differences in the scaffolds surface depending on the vancomycin concentration loaded.

Figure 5 (A1, B1) shows a micrograph of the native PCL constructs before being coated with the chitosan hydrogel. The scaffolds show a parallel distribution of the printed strands in each printed layer, and the triangular printing pattern results in scaffolds with interconnected porosity with an approximate pore size of 200 µm and an overall porosity of 59%, as calculated in a previous publication [

18]. As can be seen in

Figure 5 (A2, B2), the chitosan coating causes a discrete thickening of the 3D-printed strands as well as at the points of contact between the strands as a result of the thin coating layer provided by CS. However, this finding intensifies progressively and proportionally when the chitosan hydrogel is loaded with increasing vancomycin concentrations (A3-A6, B3-B6). The latter is observed in the micrographs corresponding to PCL/CS/20%Van scaffolds, in which almost the entire surface of the PCL scaffold was covered, making it difficult to distinguish its pores (

Figure 5 - A6, B6).

The functional characteristics of the construct developed in this study agree with the premises established by different authors for the design and fabrication of 3D scaffolds to be used for tissue engineering applications [

44,

45]. In fact, we have taken into account that an ideal construct or scaffold, in general, should have sufficient porosity to accommodate both differentiated and undifferentiated cells of different lineages. In addition, it has been combined with a natural-derived polymer (chitosan) capable of acting as a carrier or DDS for the controlled release of drugs or biomolecules. Likewise, these reticular pore systems should have open and interconnected porosity to facilitate the diffusion of nutrients, metabolites, and cells from the external environment to the inner parts of the scaffold [

20].

3.1.2. Wettability assay

The wettability of solid 3D-printed PCL scaffolds was evaluated by measuring the static water contact angle of 1 µL water droplets before and after the plasma treatments. As shown in

Figure 6, the static WCA of the untreated PCL scaffolds was 79,93 ± 2,36°, demonstrating hydrophobic behavior without any surface modification. However, for plasma-activated scaffolds, we observed water contact angles of 55,40 ± 3,16° and 59,62 ± 4,22° for Plasma 1 and Plasma 2, respectively, showing a decrease of around 20° which attests to a decrease in the surface hydrophobicity.

A change in WCA is a clear indicator of a polymer surface chemistry modification [

46]. The results obtained are in total accordance with the ones obtained by Carette

et al. who studied the effects of atmospheric plasma on the surface of a polylactic acid (PLA) scaffold in order to improve the adhesion of a 1% chitosan solution, obtaining a decrease of about 30° in WCA (from 85° to 55°) after plasma-activation [

36].

3.1.2. In vitro degradation kinetics

The

in vitro degradation assay carried out with PCL/CS/Van scaffolds did not result in any changes in the scaffold weights (W

0 = W

d) after 28 days of immersion in culture medium at 37°C, in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere and 95% of relative humidity. It is well known that CS, as well as other polysaccharides, is degraded in the body by depolymerization, oxidation, and hydrolysis (enzymatic or nonenzymatic) [

47]. Lim

et al. studied the degradation of CS porous beads with different degrees of acetylation (DA 10-50%) in different enzyme solutions (lysozyme, NAGase, and a mixture of both) [

48]. As main findings, they obtained that: (i) CS beads did not degrade in the NAGase solution, (ii) CS beads with high DA degraded faster than the ones with low DA in the lysozyme and the enzymatic mixture solutions, and (iii) CS beads with DA values around 30 to 50% were rapidly degraded into monomers in the enzymatic mixture in less than 30 to 60 days.

3.1.3. Water absorption assay

The water absorption of the chitosan coating of PCL/CS and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds was tested in PBS solutions. As can be seen in

Figure 7, the total weight of the scaffolds increased between 34,61 ± 1,13% (PCL/CS) and 42,14 ± 1,46% (PCL/CS/20%Van) after 30 minutes of immersion in PBS, and remained more or less stable for at least for 48 hours. The minimum absorption values were shown by the PCL/CS scaffolds (34,61 ± 1,13%), while the maximum ones were reached by the PCL/CS/20%Van scaffolds 45,32 ± 8,41%. The latter can be justified by the results obtained in the scaffolds characterization section (SEM imaging), which showed that increasing concentrations of vancomycin caused a thickening of the 3D-printed strands, having more chitosan surface to absorb PBS.

3.1.4. Vancomycin release quantification

The vancomycin release from the PCL/CS scaffolds loaded with 1, 5, 10, and 20% vancomycin followed a first-order release kinetics (

Figure 8). A fast vancomycin release was observed during the first hour, followed by a slower release during the next hours for all the scaffolds studied. As can be seen in the graph, vancomycin release stabilized after 24 h and seemed to reach a plateau. This release profile could be explained by the presence of two different drug fractions: (i) drug weakly bound or deposited on the CS hydrogel surface, and (ii) drug included in the CS network by chemical interactions. It is worth noting that the scaffolds loaded with 10% and 20% Van had similar drug release profiles, indicating that probably the solubility limit of the drug in PBS is between both concentrations. In this sense, the fact of loading the CS hydrogel with a higher Van dose would only result in a longer release.

These kinetics profiles are in total accordance with the results obtained by López-Iglesias

et al., who studied vancomycin release from porous chitosan aerogels obtaining similar drug-release profiles [

49]. On the other hand, Kausar

et al. developed chitosan films loaded with vancomycin (10 and 20% with respect to dry polymer mass), obtaining 100% dissolution of free-vancomycin in 7h with more than 50% of drug dissolved within the first hour [

50].

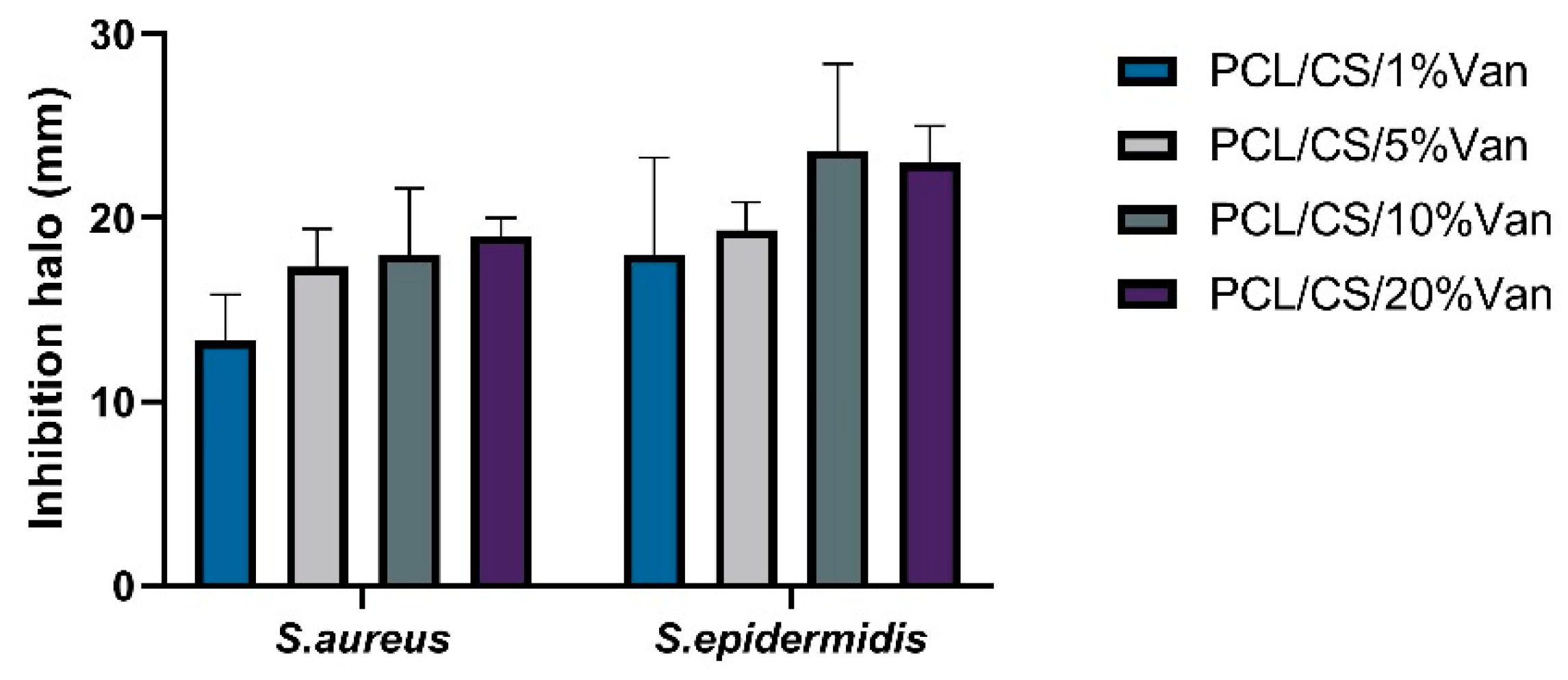

3.2. Evaluation of antimicrobial properties

PCL/Chitosan scaffolds loaded with different vancomycin concentrations have been shown to exhibit antimicrobial activity against both

S. epidermidis and

S. aureus. This is because in all cases the minimum inhibitory concentration for vancomycin was exceeded (2 μg/mL for

S. aureus and 2–4 μg/mL for

S. epidermidis) [

51,

52]. The inhibition halos were measured at 24 and 48 h, with no significant differences being observed between them. This may be due to the fact that between 6 and 24 h no more vancomycin is released (

Figure 9).

As seen in

Figure 9, in all cases a halo of inhibition is shown. In the case of

S. aureus, the highest inhibition halo is for PCL/CS/20%Van, but there are no significant differences with the PCL/CS/10%Van and PCL/CS/5%Van scaffolds. This is because the vancomycin concentration in the medium is similar to each other, 9.5 mg/mL and 8.82 mg/mL (

Figure 9), respectively. In the case of

S. epidermidis, the highest inhibition halo is obtained for the PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds. If the PCL/CS/10%Van and PCL/CS/20%Van scaffolds are compared, there are no significant differences between them because the concentration of vancomycin in the medium is similar (

Figure 9).

If we compare the inhibition halos of

S. epidermidis and

S. aureus, it is observed that although both bacteria are gram-positive, vancomycin is more effective against

S. epidermidis. No antimicrobial effect of PCL/CS was observed, this may be due to the low solubility and the limited amount of positive charges of the polysaccharide at the pH (7.4 ± 0.1) of the culture medium [

53,

54].

3.3. Biological assays

3.3.1. Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays

3.3.1.1. In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity was assessed by LDH activity assay after placing the PCL/CS/Van scaffolds in indirect contact with

ah-BM-MSCs for 24 and 72h (

Figure 10). The results of LDH release demonstrated that none of the tested scaffolds were found to be cytotoxic. However, the maximum LDH release values were achieved by PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/1%Van scaffolds, showing cytotoxicity values of 11,4 ± 6,4%, 8,3 ± 4,5%, and 10,0 ± 8,0% at 24h, and 11,1 ± 4,9%, 6,9 ± 5,0%, and 11,7 ± 6,4% at 72h, respectively, with respect to low and high control. On another hand, PCL/CS scaffolds loaded with 5, 10 and 20% vancomycin, reached cytotoxicity values of 5,7 ± 5,5%, 6,1 ± 4,7%, and 4,9 ± 5,5% at 24h, and 4,4 ± 3,4%, 4,8 ± 4,0%, and 4,7 ± 2,9% at 72h, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed between the tested samples.

Both polymers used in this study (PCL and CS) have been widely used as scaffolds for tissue engineering applications due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ease of modification [

55,

56]. Cytocompatibility of chitosan has already been studied showing that it does not have an acute cytotoxic effect [

57]. Our findings are in line with previous publications that demonstrate the good biocompatibility of PCL and CS-based structures [

33,

58].

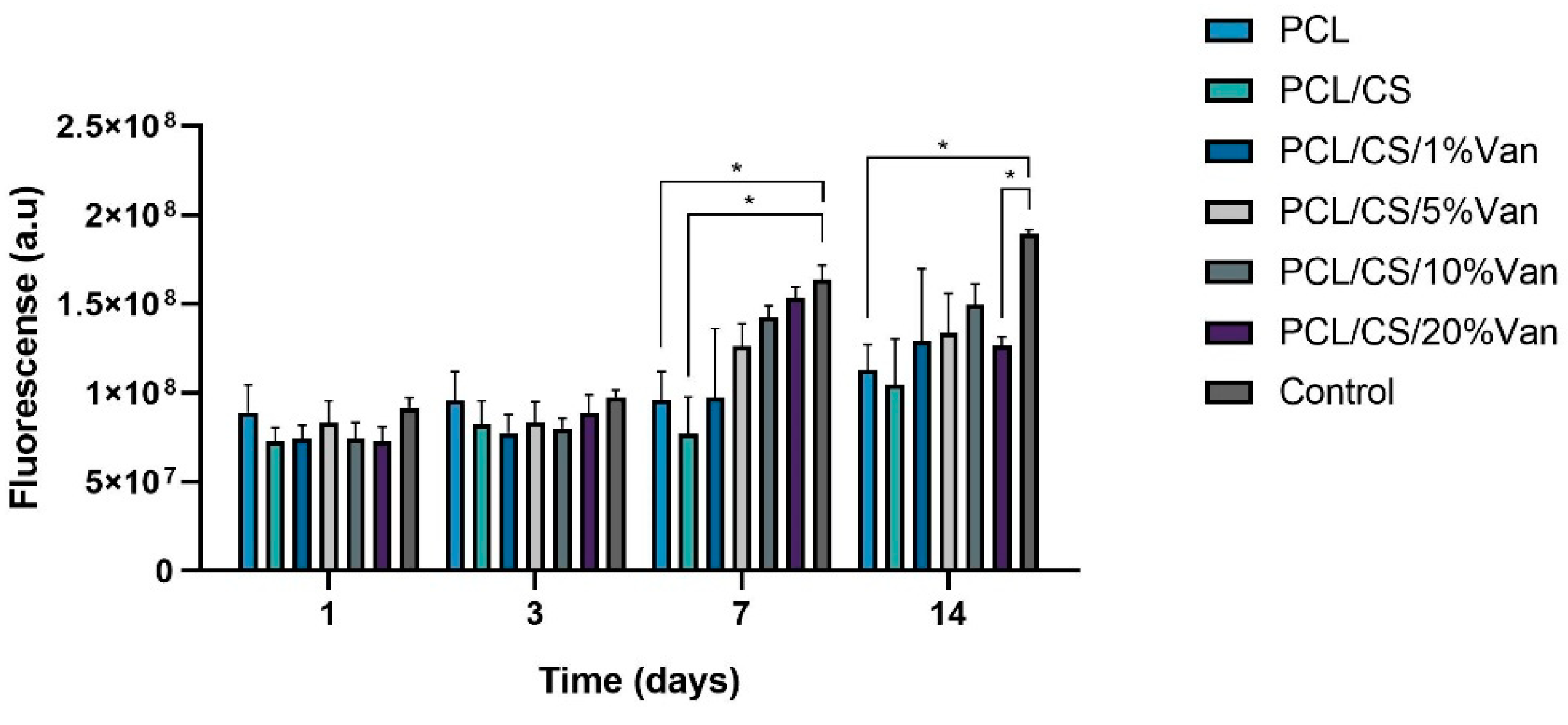

3.3.1.2. Cellular metabolic activity assay

The cellular metabolic activity of

ah-BM-MSCs growing in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds was evaluated using the AlamarBlue

® assay on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 after seeding (

Figure 11). As can be seen in the graph, the metabolic activity of

ah-BM-MSCs increased gradually from days 1 to 14 for all the scaffolds studied except for PCL/CS/20%Van, in which a slight decrease was observed after day 7. No significant differences were observed in early periods (days 1 and 3), where all the scaffolds showed a similar proliferation rate. On the other hand, significant differences were noted between PCL, PCL/CS scaffolds, and the control on day 7, and between PCL, PCL/CS/20%Van, and the control on day 14. It is worth noting that the PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds showed the higher metabolic activity with respect to the scaffolds studied.

3.3.2. Osteoblastic Differentiation Assays

The osteogenic differentiation was assessed on PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds, as it provided the best results in the cytotoxicity and proliferation assays, as well as in the microbiological assays, showing a similar bactericidal effect to the scaffold loaded with 20% vancomycin.

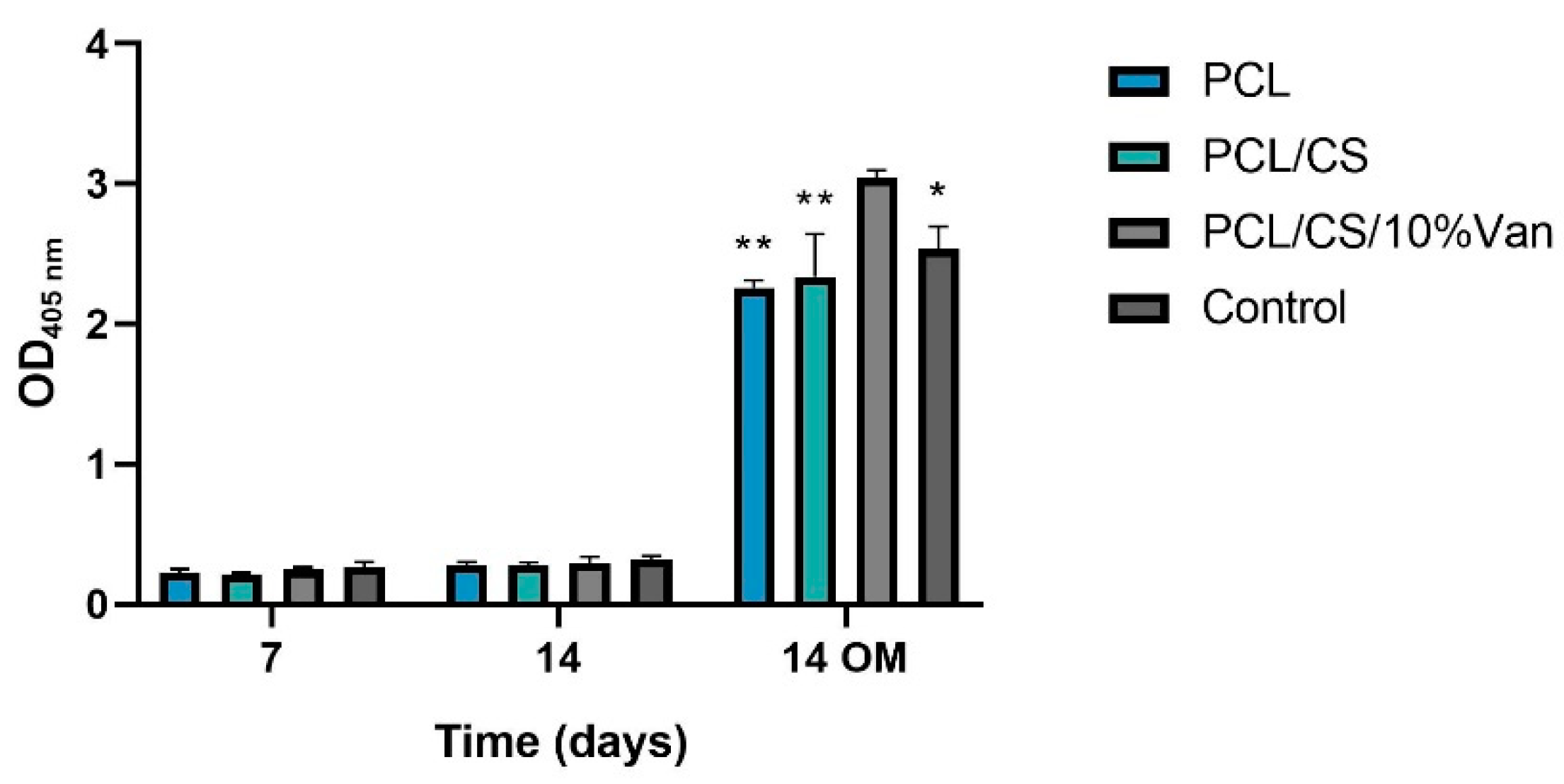

3.3.2.1. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity

The Alkaline Phosphatase activity of

ah-BM-MSCs cultured in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds is shown in

Figure 12. From days 7 to 14 using growth medium (GM), no significant differences in ALP activity were observed between the different time periods or within the scaffolds studied. On the other hand, when using osteogenic medium (OM) the ALP activity significantly increased at 14 days reaching the maximum values in the presence of PCL/CS/10%Van. In fact, significant differences were observed between the scaffold loaded with 10% vancomycin and the other experimental groups, indicating that PCL/CS/10%Van seems to increase the ALP activity of the cultured cells.

However, the PCL/CS scaffold did not show an increase in the ALP activity, so this finding cannot be attributed to the presence of the chitosan coating. Other authors have followed novel strategies to increase the osteogenic activity of chitosan, consisting of its combination with hydroxyapatite (HA) via the fabrication of carboxymethyl chitosan-HA nanofibers [

59] or HA/resveratrol/chitosan composite microspheres [

60]. This kind of HA composites can provide necessary calcium sources that can consequently induce cell differentiation, deposition of extracellular matrix, and mineralization [

61].

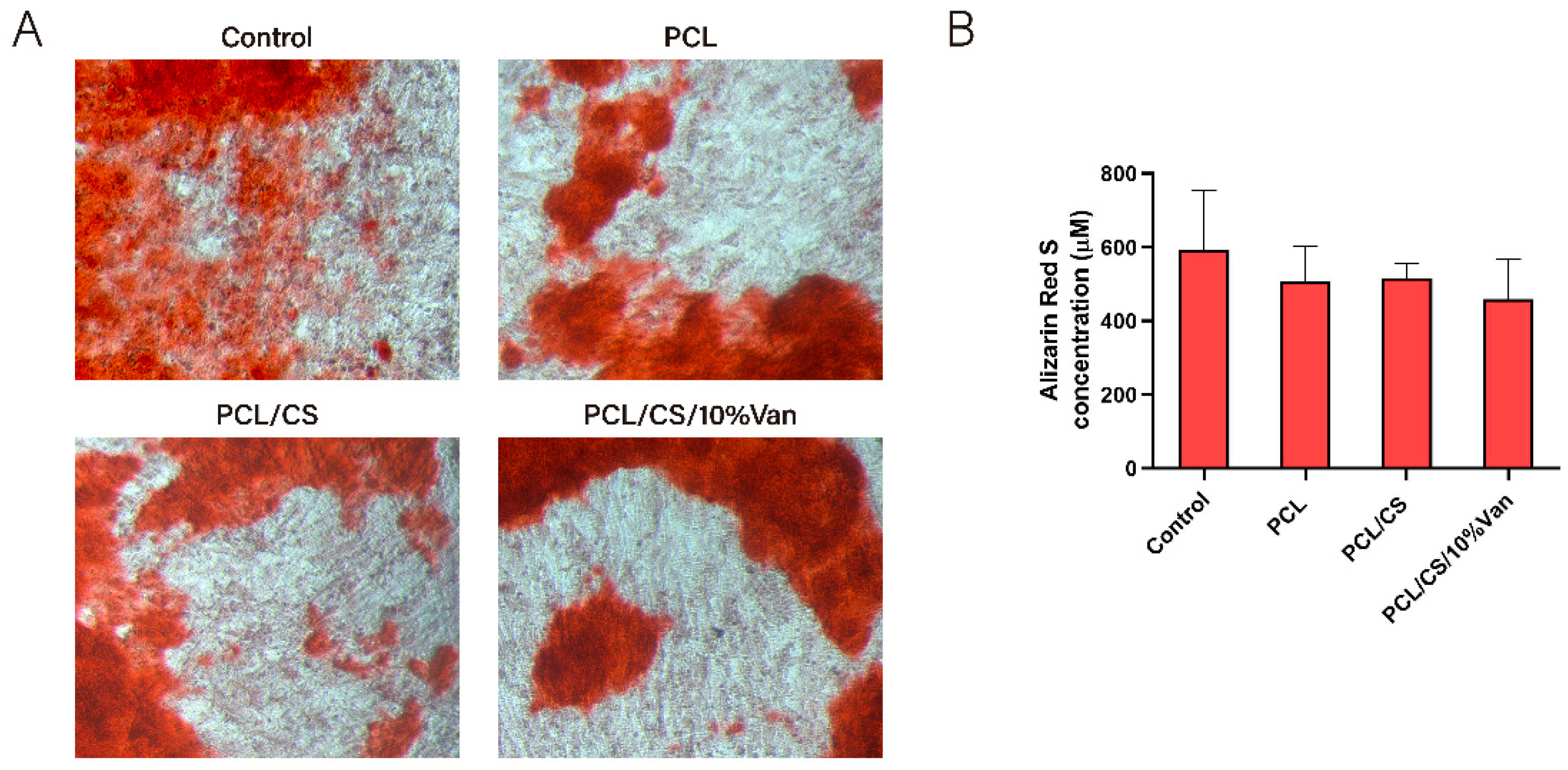

3.3.2.2. In vitro mineralization assay

The osteogenic differentiation of

ah-BM-MSCs was determined by quantifying the presence of calcium deposits after placing the PCL/CS/Van scaffolds in indirect contact with

ah-BM-MSCs for 21 days. As shown in

Figure 13A, no major visual differences were observed between the samples, although the control appears to have a slightly higher reddish coloration. The quantitative examination (

Figure 13B) showed that the Alizarin Red S concentration was higher in the control than in the cells exposed to the scaffolds, even if no significant differences were observed between the samples. This could be due to a cellular adaptation phase to varying environmental changes caused by the presence of the scaffolds, which could have slightly delayed or affected mineralization.

As demonstrated by both osteoblastic differentiation assays, the PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds did not affect ah-BM-MCSs differentiation capacity, indicating that both the scaffold components and the vancomycin dose used did not cause adverse effects or alterations at the cellular level.

4. Conclusions

Biocompatible 3D-printed hybrid PCL/CS/Van scaffolds have been developed as drug delivery systems with antimicrobial efficacy against S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Two cold plasma treatments are presented as novel methods to improve the adhesion of hydrophobic polymers to hydrogels, resulting in a decrease of PCL water contact angle of 20°. Vancomycin release was measured by means of HPLC, exceeding the minimum inhibitory concentration for both microorganisms in all the scaffolds studied (1, 5, 10, and 20%Van). In vitro assays demonstrated that PCL/CS/Van scaffolds were found to be biocompatible and bioactive as demonstrated by no cytotoxicity or functional alteration of ah-BM-MCS. In conclusion, the developed DDS could be useful to achieve a sustained, controlled, and effective local release of vancomycin against S. aureus and S. epidermidis, considered as the main causes of bone infections, but further preclinical studies in vivo using animal models are needed to confirm this results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L.-G. and L.M.-O.; methodology, I.L.-G., A.B.H-H., M.B., J.A.-G. and L.M.-O.; software, I.L.-G., M.B. and D.A.-C.; investigation and validation, I.L.-G., M.I.R.-L., M.B., J.A.-G. and L.M.-O.; formal analysis, I.L.-G, A.B.H-H. and L.M.-O.; data curation, I.L.-G., D.A.-C., M.I.R.-L. and L.M.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L.-G., D.A.-C., M.I.R.-L., M.B. and L.M.-O.; writing—review and editing, I.L.-G., A.B.H-H., D.A.-C., M.I.R.-L., J.A.-G. and L.M.-O.; visualization, I.L.-G., and L.M.-O.; supervision, L.M.-O.; project administration, I.L.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of UCAM-Universidad Católica de Murcia (Authorized No CE051904) UCAM ethics committee (CE nº 052114).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study have been disclosed in the main text.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to thank the Centre Régional d’Innovation et de Transfert de Technologie - Matériaux Innovation (CRITT-MI) for the support in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wassif, R.K.; Elkayal, M.; Shamma, R.N.; Elkheshen, S.A. Recent advances in the local antibiotics delivery systems for management of osteomyelitis. Drug Deliv 2021, 28, 2392-2414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2021.1998246. [CrossRef]

- Walter, G.; Kemmerer, M.; Kappler, C.; Hoffmann, R. Treatment algorithms for chronic osteomyelitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012, 109, 257-264. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0257. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, N.; Ryan, E.J.; Widaa, A.; Sexton, G.; Fennell, J.; O'Rourke, S.; Cahill, K.C.; Kearney, C.J.; O'Brien, F.J.; Kerrigan, S.W. Staphylococcal Osteomyelitis: Disease Progression, Treatment Challenges, and Future Directions. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018, 31. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00084-17. [CrossRef]

- Seebach, E.; Kubatzky, K.F. Chronic Implant-Related Bone Infections-Can Immune Modulation be a Therapeutic Strategy? Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01724. [CrossRef]

- Masters, E.A.; Trombetta, R.P.; de Mesy Bentley, K.L.; Boyce, B.F.; Gill, A.L.; Gill, S.R.; Nishitani, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Morita, Y.; Ito, H.; et al. Evolving concepts in bone infection: redefining "biofilm", "acute vs. chronic osteomyelitis", "the immune proteome" and "local antibiotic therapy". Bone Res 2019, 7, 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-019-0061-z. [CrossRef]

- Pincher, B.; Fenton, C.; Jeyapalan, R.; Barlow, G.; Sharma, H.K. A systematic review of the single-stage treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. J Orthop Surg Res 2019, 14, 393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1388-2. [CrossRef]

- Walenkamp, G.H.; Vree, T.B.; van Rens, T.J. Gentamicin-PMMA beads. Pharmacokinetic and nephrotoxicological study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986, 171-183.

- Walenkamp, G.H.; Kleijn, L.L.; de Leeuw, M. Osteomyelitis treated with gentamicin-PMMA beads: 100 patients followed for 1-12 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1998, 69, 518-522. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453679808997790. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.H.; Bhat, S.N.; H, M. Outcome analysis of antibiotic-loaded poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) beads in musculoskeletal infections. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2021, 16, 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.10.015. [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, T.A.G.; Arts, J.J.; Geurts, J.A.P. Antibiotic-Loaded Polymethylmethacrylate Beads and Spacers in Treatment of Orthopedic Infections and the Role of Biofilm Formation. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01626. [CrossRef]

- Makarov, C.; Cohen, V.; Raz-Pasteur, A.; Gotman, I. In vitro elution of vancomycin from biodegradable osteoconductive calcium phosphate-polycaprolactone composite beads for treatment of osteomyelitis. Eur J Pharm Sci 2014, 62, 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2014.05.008. [CrossRef]

- Gallarate, M.; Chirio, D.; Chindamo, G.; Peira, E.; Sapino, S. Osteomyelitis: Focus on Conventional Treatments and Innovative Drug Delivery Systems. Curr Drug Deliv 2021, 18, 532-545. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567201817666200915093224. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.P. Vancomycin. Mayo Clin Proc 1991, 66, 1165-1170. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65799-1. [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H.Y.; Kade, J.C.; Jeiranikhameneh, A.; Ruberu, K.; Mukherjee, P.; Yue, Z.; Wallace, G.G. 3D hybrid printing platform for auricular cartilage reconstruction. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2020, 6, 035003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2057-1976/ab54a7. [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, E.; Rindone, A.; Dorafshar, A.; Grayson, W.L. Comparison of 3D-Printed Poly-varepsilon-Caprolactone Scaffolds Functionalized with Tricalcium Phosphate, Hydroxyapatite, Bio-Oss, or Decellularized Bone Matrix<sup/>. Tissue Eng Part A 2017, 23, 503-514. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEA.2016.0418. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Wang, S.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jiang, W.B.; Huang, A.B.; Qi, Y.S.; Ding, J.X.; Chen, X.S.; Jiang, D.; Yu, J.K. 3D-Printed Poly(epsilon-caprolactone) Scaffold Augmented With Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Total Meniscal Substitution: A 12- and 24-Week Animal Study in a Rabbit Model. Am J Sports Med 2017, 45, 1497-1511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517691513. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.; Asawa, S.; Birru, B.; Baadhe, R.; Rao, S. PCL-Based Composite Scaffold Matrices for Tissue Engineering Applications. Mol Biotechnol 2018, 60, 506-532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-018-0084-5. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, I.; Zamora-Ledezma, C.; Sanchez-Lorencio, M.I.; Tristante Barrenechea, E.; Gabaldon-Hernandez, J.A.; Meseguer-Olmo, L. Modifications in Gene Expression in the Process of Osteoblastic Differentiation of Multipotent Bone Marrow-Derived Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Induced by a Novel Osteoinductive Porous Medical-Grade 3D-Printed Poly(epsilon-caprolactone)/beta-tricalcium Phosphate Composite. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222011216. [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; De Somer, F.; Van de Velde, S.; Degrieck, J.; Cardon, L. Methods for Improved Flexural Mechanical Properties of 3D-Plotted PCL-Based Scaffolds for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering. Strojniški vestnik – Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2013, 59, 669-676. https://doi.org/10.5545/sv-jme.2013.1003. [CrossRef]

- Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J. Essentials of 3D Biofabrication and Translation; 2015.

- Yeo, A.; Wong, W.J.; Khoo, H.H.; Teoh, S.H. Surface modification of PCL-TCP scaffolds improve interfacial mechanical interlock and enhance early bone formation: an in vitro and in vivo characterization. J Biomed Mater Res A 2010, 92, 311-321. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.32366. [CrossRef]

- Mirtaghi, S.M.; Hassannia, H.; Mahdavi, M.; Hosseini-Khah, Z.; Mellati, A.; Enderami, S.E. A novel hybrid polymer of PCL/fish gelatin nanofibrous scaffold improves proliferation and differentiation of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal cells into islet-like cells. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 1491-1503. https://doi.org/10.1111/aor.14257. [CrossRef]

- Merk, M.; Chirikian, O.; Adlhart, C. 3D PCL/Gelatin/Genipin Nanofiber Sponge as Scaffold for Regenerative Medicine. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14082006. [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.H.; Kim, M.S.; Cho, Y.B.; Jang, Y.S.; Kim, G.H. Mastoid obliteration using 3D PCL scaffold in combination with alginate and rhBMP-2. Int J Biol Macromol 2013, 62, 614-622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.10.011. [CrossRef]

- Do, N.H.N.; Truong, Q.T.; Le, P.K.; Ha, A.C. Recent developments in chitosan hydrogels carrying natural bioactive compounds. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 294, 119726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119726. [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.A.; Palomino-Durand, C.; Elsafi Mabrouk, M.; Marquaille, P.; Odier, C.; Norvez, S.; Pauthe, E.; Corte, L. Rational formulation design of injectable thermosensitive chitosan-based hydrogels for cell encapsulation and delivery. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 277, 118836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118836. [CrossRef]

- Catoira, M.C.; Fusaro, L.; Di Francesco, D.; Ramella, M.; Boccafoschi, F. Overview of natural hydrogels for regenerative medicine applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2019, 30, 115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-019-6318-7. [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, H.; Moradi, S.; Hudson, S.M.; Tonelli, A.E. Chitosan based hydrogels and their applications for drug delivery in wound dressings: A review. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 199, 445-460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.114. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, K.; Millet, Y.; Ricordi, C.; Stabler, C.L. Tissue engineering and biomaterials in regenerative medicine. Cell Transplant 2008, 17, 241-243. https://doi.org/10.3727/096368908784153931. [CrossRef]

- Domalik-Pyzik, P.; Chłopek, J.; Pielichowska, K. Chitosan-Based Hydrogels: Preparation, Properties, and Applications. In Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels; Polymers and Polymeric Composites: A Reference Series; 2018; pp. 1-29.

- Seo, J.W.; Shin, S.R.; Lee, M.Y.; Cha, J.M.; Min, K.H.; Lee, S.C.; Shin, S.Y.; Bae, H. Injectable hydrogel derived from chitosan with tunable mechanical properties via hybrid-crosslinking system. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 251, 117036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117036. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2012, 64, 18-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.010. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Fu, L.; Liao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Ning, C.; Gao, C.; Zhang, D.; Sui, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Chitosan hydrogel/3D-printed poly(epsilon-caprolactone) hybrid scaffold containing synovial mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage regeneration based on tetrahedral framework nucleic acid recruitment. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121131. [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.A.; Virgilio, N.; Rouabhia, M.; Mighri, F. Development and Characterization of Functional Polylactic Acid/Chitosan Porous Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14235079. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Johnson, B.N.; Jia, X. Three-dimensional (3D) printed scaffold and material selection for bone repair. Acta Biomater 2019, 84, 16-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.039. [CrossRef]

- Carette, X.; Mincheva, R.; Herbin, M.; Noirfalise, X.; Nguyen, T.C.; Leclere, P.; Godfroid, T.; Kerdjoudj, H.; Jolois, O.; Boudhifa, M.; et al. Atmospheric plasma: a simple way of improving the interface between natural polysaccharides and polyesters. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 1056. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1056/1/012005. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yan, P.; Shao, T. Comparison between helium and argon plasma jets on improving the hydrophilic property of PMMA surface. Applied Surface Science 2016, 367, 401-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.199. [CrossRef]

- Robert, E.; Barbosa, E.; Dozias, S.; Vandamme, M.; Cachoncinlle, C.; Viladrosa, R.; Pouvesle, J.M. Experimental Study of a Compact Nanosecond Plasma Gun. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2009, NA-NA. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.200900078. [CrossRef]

- A. EPCOS, « CeraPlas® HF Series », Piezoelectric Based Plasma Gener. Data Sheet. 2018.

- De Aza, P.N.; Garcia-Bernal, D.; Cragnolini, F.; Velasquez, P.; Meseguer-Olmo, L. The effects of Ca2SiO4-Ca3(PO4)2 ceramics on adult human mesenchymal stem cell viability, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and function. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2013, 33, 4009-4020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.043. [CrossRef]

- Rabadan-Ros, R.; Revilla-Nuin, B.; Mazón, P.; Aznar-Cervantes, S.; Ros-Tarraga, P.; De Aza, P.N.; Meseguer-Olmo, L. Impact of a Porous Si-Ca-P Monophasic Ceramic on Variation of Osteogenesis-Related Gene Expression of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Applied Sciences 2018, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8010046. [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14653240600855905. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, E.M.; Le Blanc, K.; Dominici, M.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Deans, R.J.; Krause, D.S.; Keating, A.; International Society for Cellular, T. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2005, 7, 393-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/14653240500319234. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, P.X. Polymeric scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng 2004, 32, 477-486. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:abme.0000017544.36001.8e. [CrossRef]

- Raeisdasteh Hokmabad, V.; Davaran, S.; Ramazani, A.; Salehi, R. Design and fabrication of porous biodegradable scaffolds: a strategy for tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2017, 28, 1797-1825. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2017.1354674. [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, R.E.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Adhesion between biodegradable polymers and hydroxyapatite: Relevance to synthetic bone-like materials and tissue engineering scaffolds. Acta Biomater 2008, 4, 1288-1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.006. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.A. Controlling chitosan degradation properties in vitro and in vivo. In Chitosan Based Biomaterials Volume 1; 2017; pp. 159-182.

- Lim, S.M.; Song, D.K.; Oh, S.H.; Lee-Yoon, D.S.; Bae, E.H.; Lee, J.H. In vitro and in vivo degradation behavior of acetylated chitosan porous beads. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2008, 19, 453-466. https://doi.org/10.1163/156856208783719482. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Iglesias, C.; Barros, J.; Ardao, I.; Monteiro, F.J.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Gomez-Amoza, J.L.; Garcia-Gonzalez, C.A. Vancomycin-loaded chitosan aerogel particles for chronic wound applications. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 204, 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.012. [CrossRef]

- Kausar, R.; Khan, A.U.; Jamil, B.; Shahzad, Y.; Ul-Haq, I. Development and pharmacological evaluation of vancomycin loaded chitosan films. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 256, 117565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117565. [CrossRef]

- Hadder, B.; Dexter, F.; Robinson, A.D.M.; Loftus, R.W. Molecular characterisation and epidemiology of transmission of intraoperative Staphylococcus aureus isolates stratified by vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Infect Prev Pract 2022, 4, 100249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2022.100249. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, P.B.; Massinhani, F.H.; Netto Dos Santos, K.R.; Chamon, R.C.; Silva, R.B.; Lopes Correa, F.E.; Barata Oliveira, C.; Oliveira, A.G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates with reduced vancomycin susceptibility from bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Med Microbiol 2020, 69, 41-45. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001117. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Lin, H.T.; Wu, G.J.; Tsai, G.J. pH Effects on solubility, zeta potential, and correlation between antibacterial activity and molecular weight of chitosan. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 134, 74-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.07.072. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, C.A.; Barros, J.; Rey-Rico, A.; Redondo, P.; Gomez-Amoza, J.L.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Monteiro, F.J. Antimicrobial Properties and Osteogenicity of Vancomycin-Loaded Synthetic Scaffolds Obtained by Supercritical Foaming. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 3349-3360. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b17375. [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, A.; Kumar, A.; Priyadharshini, A.; Oggu, G.S.; Bhatnagar, I.; Srivastava, A.; Chandra, P. Chitosan: An undisputed bio-fabrication material for tissue engineering and bio-sensing applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 110, 110-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Backes, E.H.; Harb, S.V.; Beatrice, C.A.G.; Shimomura, K.M.B.; Passador, F.R.; Costa, L.C.; Pessan, L.A. Polycaprolactone usage in additive manufacturing strategies for tissue engineering applications: A review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2022, 110, 1479-1503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34997. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.O.G.; Leite, L.L.R.; de Lima, I.S.; Barreto, H.M.; Nunes, L.C.C.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Osajima, J.A.; da Silva Filho, E.C. Chitosan Hydrogel in combination with Nerolidol for healing wounds. Carbohydr Polym 2016, 152, 409-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.037. [CrossRef]

- Tardajos, M.G.; Cama, G.; Dash, M.; Misseeuw, L.; Gheysens, T.; Gorzelanny, C.; Coenye, T.; Dubruel, P. Chitosan functionalized poly-epsilon-caprolactone electrospun fibers and 3D printed scaffolds as antibacterial materials for tissue engineering applications. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 191, 127-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.02.060. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Zou, Q.; Du, C. Biomimetic mineralization of carboxymethyl chitosan nanofibers with improved osteogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 195, 225-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.090. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Zheng, M.; Han, Y.; Lu, D.; Lu, S.; Gui, L. Synergistic anti-inflammatory and osteogenic n-HA/resveratrol/chitosan composite microspheres for osteoporotic bone regeneration. Bioact Mater 2021, 6, 1255-1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.10.018. [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Zou, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, B.; Li, Y. Fabrication and cell viability of injectable n-HA/chitosan composite microspheres for bone tissue engineering. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 85735-85744. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra06594e. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of current antibiotic treatment strategies used to control bone infections (blue spheres: antibiotics, A: intravenous route, B: local drug delivery system (DDS), C: fabrication of a scaffold loaded with antibiotics).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of current antibiotic treatment strategies used to control bone infections (blue spheres: antibiotics, A: intravenous route, B: local drug delivery system (DDS), C: fabrication of a scaffold loaded with antibiotics).

Figure 2.

Micrographs of (A) porous and (B) solid PCL scaffolds printed with REGEMAT 3D Bio V1® bioprinter.

Figure 2.

Micrographs of (A) porous and (B) solid PCL scaffolds printed with REGEMAT 3D Bio V1® bioprinter.

Figure 3.

Plasma treatments performed to the PCL scaffolds. (A) Cold atmospheric plasma jet, (B) Home-made torch with a piezoelectric plasma generator. Optical microscopy images of (C) Solid PCL scaffold (untreated) coated with the CS hydrogel, (D) Solid PCL scaffold coated with the CS hydrogel after being exposed to cold plasma for 30 seconds.

Figure 3.

Plasma treatments performed to the PCL scaffolds. (A) Cold atmospheric plasma jet, (B) Home-made torch with a piezoelectric plasma generator. Optical microscopy images of (C) Solid PCL scaffold (untreated) coated with the CS hydrogel, (D) Solid PCL scaffold coated with the CS hydrogel after being exposed to cold plasma for 30 seconds.

Figure 4.

Determination of the optimal target cell concentration for ah-BM-MSCs. ah-BM-MSCs were titrated in 24-WP at a density of 100, 1000, 5000, 10000, 20000, 30000, 40000, 50000, 75000, and 100000 cells/well. Culture medium was added for the determination of the spontaneous LDH activity (samples) and culture medium containing 1% Triton X-100 was added to determine the maximum LDH release (positive control).

Figure 4.

Determination of the optimal target cell concentration for ah-BM-MSCs. ah-BM-MSCs were titrated in 24-WP at a density of 100, 1000, 5000, 10000, 20000, 30000, 40000, 50000, 75000, and 100000 cells/well. Culture medium was added for the determination of the spontaneous LDH activity (samples) and culture medium containing 1% Triton X-100 was added to determine the maximum LDH release (positive control).

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of the (1) PCL, (2) PCL/CS, and (3, 4, 5, 6) PCL/CS/Van scaffolds loaded with 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% w/t vancomycin, respectively, at different magnifications: (A1-A6) 22X, scale bar 2 mm; (B1-B6) 40X, scale bar 1 mm; (C3) scale bar 200 µm; (C5) scale bar 700 µm.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of the (1) PCL, (2) PCL/CS, and (3, 4, 5, 6) PCL/CS/Van scaffolds loaded with 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% w/t vancomycin, respectively, at different magnifications: (A1-A6) 22X, scale bar 2 mm; (B1-B6) 40X, scale bar 1 mm; (C3) scale bar 200 µm; (C5) scale bar 700 µm.

Figure 6.

(A) Water contact angle on 3D-printed solid (non-porous) PCL scaffolds before and after the plasma treatments. (Plasma 1: Cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet, Plasma 2: Home-made torch with piezoelectric plasma generator). Water droplets with a volume of 1 µL deposited on (B) non-treated PCL scaffolds, and (C) PCL scaffolds treated with Plasma 1. Data represent mean ± SD. * Significant differences with the water contact angle of non-treated PCL scaffold.

Figure 6.

(A) Water contact angle on 3D-printed solid (non-porous) PCL scaffolds before and after the plasma treatments. (Plasma 1: Cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet, Plasma 2: Home-made torch with piezoelectric plasma generator). Water droplets with a volume of 1 µL deposited on (B) non-treated PCL scaffolds, and (C) PCL scaffolds treated with Plasma 1. Data represent mean ± SD. * Significant differences with the water contact angle of non-treated PCL scaffold.

Figure 7.

Water absorption as a function of time of PCL/CS and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds (1, 5, 10, and 20%) in contact with PBS medium (pH = 7.4).

Figure 7.

Water absorption as a function of time of PCL/CS and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds (1, 5, 10, and 20%) in contact with PBS medium (pH = 7.4).

Figure 8.

In vitro cumulative drug release profiles of PCL/CS scaffolds loaded with 1, 5, 10, and 20% vancomycin for 14 days (336 h).

Figure 8.

In vitro cumulative drug release profiles of PCL/CS scaffolds loaded with 1, 5, 10, and 20% vancomycin for 14 days (336 h).

Figure 9.

Inhibition halos (mm) produced by PCL/CS/Van scaffolds loaded with 1, 5, 10, and 20% w/t vancomycin for S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Data represent mean ± SD. No significant differences were found between the scaffolds for both microorganisms studied.

Figure 9.

Inhibition halos (mm) produced by PCL/CS/Van scaffolds loaded with 1, 5, 10, and 20% w/t vancomycin for S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Data represent mean ± SD. No significant differences were found between the scaffolds for both microorganisms studied.

Figure 10.

Cytotoxicity results using the LDH assay after placing PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds in indirect contact with ah-BM-MSCs for 24 and 72 h. The mean cytotoxicity percentage was calculated and normalized with respect to spontaneous LDH release (Low control) and maximum LDH release (High control). Bars represent standard deviations of the mean. No significant differences were observed between the tested samples.

Figure 10.

Cytotoxicity results using the LDH assay after placing PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/Van scaffolds in indirect contact with ah-BM-MSCs for 24 and 72 h. The mean cytotoxicity percentage was calculated and normalized with respect to spontaneous LDH release (Low control) and maximum LDH release (High control). Bars represent standard deviations of the mean. No significant differences were observed between the tested samples.

Figure 11.

Cellular metabolic activity of ah-BM-MSCs using the AlamarBlue® assay at different time periods. The metabolic activity of cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) was used as positive control. Bars represent standard deviations of the mean. * Significant differences between the bracketed groups at the same time period.

Figure 11.

Cellular metabolic activity of ah-BM-MSCs using the AlamarBlue® assay at different time periods. The metabolic activity of cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) was used as positive control. Bars represent standard deviations of the mean. * Significant differences between the bracketed groups at the same time period.

Figure 12.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of ah-BM-MSCs after being cultured for 7 and 14 days in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds using growth medium (GM) and osteogenic medium (OM). Cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) were taken as positive control. Results are shown as a function of optical density (OD405 nm) units. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences were found between PCL/CS/10%Van and the other samples at 14 days with OM; * p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.0001.

Figure 12.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of ah-BM-MSCs after being cultured for 7 and 14 days in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds using growth medium (GM) and osteogenic medium (OM). Cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) were taken as positive control. Results are shown as a function of optical density (OD405 nm) units. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences were found between PCL/CS/10%Van and the other samples at 14 days with OM; * p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.0001.

Figure 13.

Alizarin Red Staining of ah-BM-MSCs after being cultured for 21 days in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds. (A) Alizarin Red Staining showing mineralization (original magnification x10), (B) Quantitative determination of Alizarin Red Staining. Cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) were taken as positive control. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD. No significant differences were observed between the groups.

Figure 13.

Alizarin Red Staining of ah-BM-MSCs after being cultured for 21 days in the presence of PCL, PCL/CS, and PCL/CS/10%Van scaffolds. (A) Alizarin Red Staining showing mineralization (original magnification x10), (B) Quantitative determination of Alizarin Red Staining. Cells seeded on plastic (TCPs) were taken as positive control. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD. No significant differences were observed between the groups.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).