Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Search strategy

Eligibility criteria

- Study population: Patients, with no restrictions towards specific diagnose.

- Concept/Phenomena of interest: Intervention/exposure: A structured exercise-based rehabilitation intervention, incidental or intentional interaction with nature. Studies combining an exercise-based rehabilitation with other interventions were included.

- No publication date restriction was applied

Selecting evidence

Critical appraisal

Extracting evidence

Analysis and presentation of results

Results

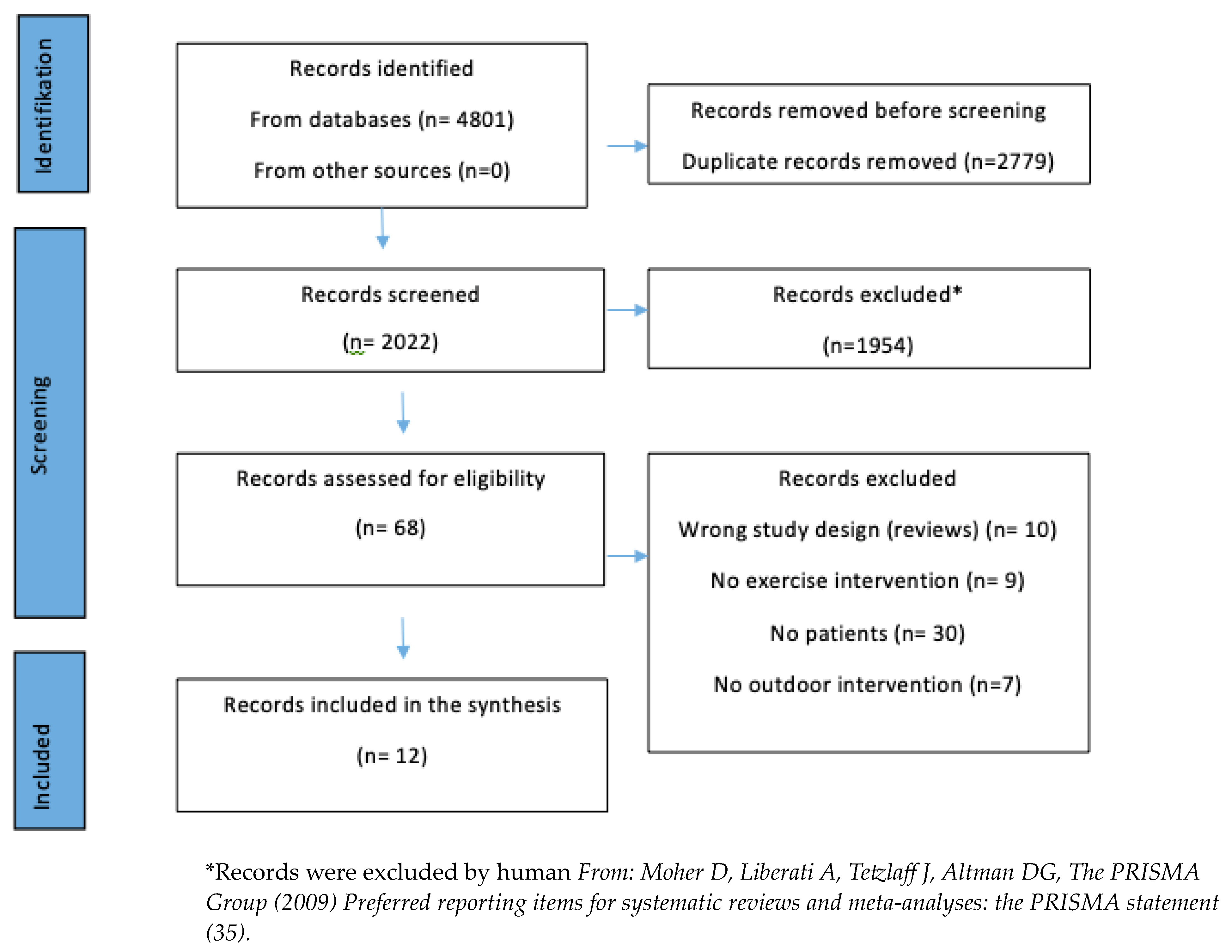

Identification of potential articles

Identification of potential articles

Characteristics of included articles

Characteristics of included patients

Characteristics of interventions

The rationales in the included studies

Characteristics of Outcomes

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Disclosure/Declaration of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Characteristics | ||||

| 1. Study | First author et al. | |||

| Country | ||||

| Year | ||||

| Publication type | ||||

| Design of study | ||||

| Recruitment method | ||||

| 2. Participants | Participants | |||

| Number of patients | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Disabilities/diagnosis and number, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, type, frequency and severity of comorbidities | ||||

| 3. Intervention | TIDieR- checklist (33) | Additional considerations for integration of natural environment and/or -components within the interventions | ||

| BRIEF NAME Provide the name or a phrase that describes the intervention |

Should include the word “outdoor” (or a term that very clearly indicates that an intervention is being delivered outside in nature – e.g. nature, natural environment, nature based, greenspace, bluespace) it indicates that aspects of nature integration has been considered and may be a weighty feature of the intervention. | |||

| WHY Describe any rationale, theory, or goal of the elements essential to the intervention |

Provide the rationale, theory or goal for using an outdoor setting for the intervention. Is an outdoor setting used to expand access, improve motivation, retention or to enhance effect/outcome for participants? Is outdoor delivery an evidence-based option for the intervention? Is the goal to validate use of a traditional intervention delivered in an outdoor setting? Or have they developed a specific intervention tailored to be conducted in a nature/outdoor setting? | |||

| WHAT Describe any physical or informational materials used in the intervention, including those provided to participants or used in intervention delivery or in the training of intervention providers. Provide information on where the materials can be accessed (e.g. online appendix, URL). Procedures: Describe each of the procedures, activities, and/or processes used in the intervention, including any enabling or supporting activities. |

Which nature elements (e.g. materials and equipment) are used physically or metaphorically? Is the nature actively and deliberately used as a tool (physical or symbolic) in the exercises? What (if any) additional documentation, instruction and/or equipment was provided (lend or given) to participants? |

|||

| Were the procedures for this intervention originally developed for conventional indoor or outdoor delivery? What, if anything, was done to adapt procedures from indoor delivery? Any considerations of flexibility in relation to the natural environment? Describe each of the nature integrative activities and the aimed responses of the nature integrative means. Describe the processes/progressions motivated by means and responses. |

||||

| WHO PROVIDED For each category of intervention provider (e.g. psychologist, nursing assistant), describe their expertise, background, and any specific training given. |

Who delivered/facilitated the outdoor intervention? Was there any training that went into the delivery of the intervention? Who was authorised/approved to deliver it and how did they achieve authorisation approval (e.g. training, certification process)? | |||

| HOW Describe the modes of delivery (e.g. face-to-face or by some other mechanism, such as internet or telephone) of the intervention and whether it was provided individually or in a group. |

Indicate whether the intervention was delivered solely outdoors or in a hybrid (indoors + outdoors) format. Synchronous versus asynchronous, individual or group, unidirectional or bidirectional (could the participant/attendee ask questions, respond, interact and, if so, how – voice, chat, etc.?) How are the operations/activities/exercises facilitated? |

|||

| WHERE Describe the type(s) of location(s) where the intervention occurred, including any necessary infrastructure or relevant features. |

Which nature surrounding does the outdoor intervention include (e.g. open spaces, shelter, hills, hedge) Were there any specific features considered or highlighted regarding the location? Which components in the outdoor setting are incorporated in the intervention? (e.g. terrain, spaciousness, means of shelter, hedges. Type of outdoor environment, open field, enclosed forest, flat or undulating terrain, exposed/public area, rural location? In what geographic climate and season did the intervention take place? |

|||

| WHEN and HOW MUCH Describe the number of times the intervention was delivered and over what period of time including the number of sessions, their schedule, and their duration, intensity, or dose. |

Provide the planned intervention dosing (visits, frequency, duration, etc.) for the trial (expected treatment to meet optimal fidelity) and then also the number of actual visits received. Provide duration and frequency of sessions. | |||

| TAILORING If the intervention was planned to be personalised, titrated or adapted, then describe what, why, when, and how. |

Describe the flexibility of the intervention to allow for any changes in or tailoring of the outdoor intervention for individual patients or specific groups. | |||

| MODIFICATIONS If the intervention was modified during the course of the study, describe the changes (what, why, when, and how). |

If it was planned to be executed outdoors and then had to be switched to indoors, provide the timing, reasons, and rationale for the change. If any modification motivated or caused by the natural environment |

|||

|

HOW WELL Planned: If intervention adherence or fidelity was assessed, describe how and by whom; and if any strategies were used to maintain or improve fidelity, describe them. Actual: If intervention adherence or fidelity was assessed, describe the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned. |

Identify any specific strategies used to improve adherence to the outdoor intervention. Was there a plan to monitor and track fidelity of the intervention? Did the outdoor intervention influence actual treatment adherence? Was the fidelity of the outdoor intervention reported? |

|||

| 4. Outcome | Description of the outcome* | |||

| Time points assessed | ||||

| Adverse events** | ||||

| Serious adverse events*** | ||||

References

- Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;2016(1):Cd001800. [CrossRef]

- Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ, Troosters T. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;12(12):Cd005305. [CrossRef]

- Giné-Garriga M, Roqué-Fíguls M, Coll-Planas L, Sitjà-Rabert M, Salvà A. Physical exercise interventions for improving performance-based measures of physical function in community-dwelling, frail older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2014;95(4):753-69.e3. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2015;25 Suppl 3:1-72. [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter UK, Corazon SS, Sidenius U, Nyed PK, Larsen HB, Fjorback LO. Efficacy of nature-based therapy for individuals with stress-related illnesses: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(1):404-11. [CrossRef]

- Louise Sofia M, Dorthe Varning P, Claus Vinther N, Charlotte H. “It Was Definitely an Eye-Opener to Me”—People with Disabilities’ and Health Professionals’ Perceptions on Combining Traditional Indoor Rehabilitation Practice with an Urban Green Rehabilitation Context. 2021.

- Passantino A, Dalla Vecchia LA, Corrà U, Scalvini S, Pistono M, Bussotti M, et al. The Future of Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients With Heart Failure. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2021;8:709898. [CrossRef]

- Hinde S, Bojke L, Coventry P. The Cost Effectiveness of Ecotherapy as a Healthcare Intervention, Separating the Wood from the Trees. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(21). [CrossRef]

- Smith G, Cirach M, Swart W, Dėdelė A, Gidlow C, Elise van K, et al. Characterisation of the natural environment: quantitative indicators across Europe. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2017;16. [CrossRef]

- Pálsdóttir AM, Persson D, Persson B, Grahn P. The journey of recovery and empowerment embraced by nature - clients' perspectives on nature-based rehabilitation in relation to the role of the natural environment. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014;11(7):7094-115. [CrossRef]

- Iyendo TO, Uwajeh PC, Ikenna ES. The therapeutic impacts of environmental design interventions on wellness in clinical settings: A narrative review. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2016;24:174-88. [CrossRef]

- Pálsdóttir AM, Stigsdotter UK, Persson D, Thorpert P, Grahn P. The qualities of natural environments that support the rehabilitation process of individuals with stress-related mental disorder in nature-based rehabilitation. Urban forestry & urban greening. 2018;29:312-21. [CrossRef]

- Ballew MT, Omoto AM. Absorption: How Nature Experiences Promote Awe and Other Positive Emotions. Ecopsychology. 2018;10(1):26-35. [CrossRef]

- Lacharité-Lemieux M, Brunelle J-P, Dionne IJ. Adherence to exercise and affective responses: comparison between outdoor and indoor training. Menopause (New York, NY). 2015;22(7):731-40. [CrossRef]

- Trøstrup CH, Christiansen AB, Stølen KS, Nielsen PK, Stelter R. The effect of nature exposure on the mental health of patients: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1695-703. [CrossRef]

- Coventry PA, Brown JE, Pervin J, Brabyn S, Pateman R, Breedvelt J, et al. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM - population health. 2021;16:100934. [CrossRef]

- Pryor Anita HN, Parpenter C. Outdoor Therapy: Benefits, Mechanisms and Principles for Activating Health, Wellbeing, and Healing in Nature. Outdoor Environmental Eduaction in Higher Education: Springer 2021. p. 123-43.

- Keniger LE, Gaston KJ, Irvine KN, Fuller RA. What are the benefits of interacting with nature? International journal of environmental research and public health. 2013;10(3):913-35. [CrossRef]

- Del Din S, Galna B, Lord S, Nieuwboer A, Bekkers EMJ, Pelosin E, et al. Falls Risk in Relation to Activity Exposure in High-Risk Older Adults. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2020;75(6):1198-205. [CrossRef]

- Litleskare S, Fröhlich F, Flaten OE, Haile A, Kjøs Johnsen S, Calogiuri G. Taking real steps in virtual nature: a randomized blinded trial. Virtual reality. 2022;26(4):1777-93. [CrossRef]

- Wooller JJ, Rogerson M, Barton J, Micklewright D, Gladwell V. Can Simulated Green Exercise Improve Recovery From Acute Mental Stress? Frontiers in psychology. 2018;9:2167.

- Chaudhury P, Banerjee D. "Recovering With Nature": A Review of Ecotherapy and Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in public health. 2020;8:604440. [CrossRef]

- Vibholm AP, Christensen JR, Pallesen H. Occupational therapists and physiotherapists experiences of using nature-based rehabilitation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022:1-11.

- Vujcic M, Tomicevic-Dubljevic J, Grbic M, Lecic-Tosevski D, Vukovic O, Toskovic O. Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environmental research. 2017;158:385-92. [CrossRef]

- Sus Sola C, Ulrik S, Dorthe Varning P, Marie Christoffersen G, Ulrika KS. Psycho-Physiological Stress Recovery in Outdoor Nature-Based Interventions : A Systematic Review of the Past Eight Years of Research. 2019.

- Grahn P, Pálsdóttir AM, Ottosson J, Jonsdottir IH. Longer Nature-Based Rehabilitation May Contribute to a Faster Return to Work in Patients with Reactions to Severe Stress and/or Depression. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2017;14(11):1310. [CrossRef]

- Sudimac S, Sale V, Kühn S. How nature nurtures: Amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Molecular psychiatry. 2022;27(11):4446-52. [CrossRef]

- Alfredsson, LL. - Åpne dørene for fysioterapeutiske tiltak utendørs! : Fysioterapeuten; 2023 [Available from: https://www.fysioterapeuten.no/fysioterapeut-fysioterapeuten-fysioterapeuter/apne-dorene-for-fysioterapeutiske-tiltak-utendors/147998.

- Stanhope J, Maric F, Rothmore P, Weinstein P. Physiotherapy and ecosystem services: improving the health of our patients, the population, and the environment. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023;39(2):227-40. [CrossRef]

- Henriette B, Ulrik S, Line Planck K, Sus Sola C, Christina Bjørk P, Dorthe Varning P, et al. Economic Evaluation of Nature-Based Therapy Interventions—A Scoping Review. 2022.

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI evidence implementation. 2021;19(1):3-10. [CrossRef]

- Hinde S, Spackman E. Bidirectional citation searching to completion: an exploration of literature searching methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(1):5-11. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj. 2014;348:g1687. [CrossRef]

- Saleh AA, Ratajeski MA, Bertolet M. Grey Literature Searching for Health Sciences Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Study of Time Spent and Resources Utilized. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2014;9(3):28-50. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Fruehauf AM, Niedermeier M, Elliott LR, Ledochowski L, Marksteiner J, Kopp M. Acute effects of outdoor physical activity on affect and psychological well-being in depressed patients – a preliminary study. Mental health and physical activity. 2016;10:4-9. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs K, Wilkie L, Jarman J, Barker-Smith A, Kemp AH, Fisher Z. Riding the wave into wellbeing: A qualitative evaluation of surf therapy for individuals living with acquired brain injury. PloS one. 2022;17(4):e0266388-e. [CrossRef]

- Huber D, Grafetstatter C, Prossegger J, Pichler C, Woll E, Fischer M, et al. Green exercise and mg-ca-SO4 thermal balneotherapy for the treatment of non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019;20(1):221-. [CrossRef]

- Kang B, Kim T, Kim MJ, Lee KH, Choi S, Lee DH, et al. Relief of Chronic Posterior Neck Pain Depending on the Type of Forest Therapy: Comparison of the Therapeutic Effect of Forest Bathing Alone Versus Forest Bathing With Exercise. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2015;39(6):957-63. [CrossRef]

- López-Pousa S, Bassets Pagès G, Monserrat-Vila S, de Gracia Blanco M, Hidalgo Colomé J, Garre-Olmo J. Sense of Well-Being in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Aerobic Exercise Program in a Mature Forest—A Pilot Study. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. 2015;2015:614783-9. [CrossRef]

- Miller JM, Sadak KT, Shahriar AA, Wilson NJ, Hampton M, Bhattacharya M, et al. Cancer survivors exercise at higher intensity in outdoor settings: The GECCOS trial. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2021;68(5):e28850-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Noushad S, Ansari B, Ahmed S. Effect of nature-based physical activity on post-traumatic growth among healthcare providers with post-traumatic stress. Stress and health. 2022;38(4):813-26. [CrossRef]

- Serrat M, Almirall M, Musté M, Sanabria-Mazo JP, Feliu-Soler A, Méndez-Ulrich JL, et al. Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Treatment for Fibromyalgia Based on Pain Neuroscience Education, Exercise Therapy, Psychological Support, and Nature Exposure (NAT-FM): A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020;9(10):3348. [CrossRef]

- Song C, Ikei H, Kobayashi M, Miura T, Taue M, Kagawa T, et al. Effect of forest walking on autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: a pilot study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2015;12(3):2687-99. [CrossRef]

- van den Berg AE, Beute F. Walk it off! The effectiveness of walk and talk coaching in nature for individuals with burnout- and stress-related complaints. Journal of environmental psychology. 2021;76:101641.

- Wen Y, Lian L, Xun Z, Jiaying M, Shuyi C, Wanwen H, et al. Effect of a Rehabilitation Garden on Rehabilitation Efficacy in Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Pakistan journal of zoology. 2020;52(6). [CrossRef]

- Liu-Ambrose, T. Supporting Aging Through Green Exercise. In: Columbia UoB, editor. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT050363042022.

- Bergenheim A, Ahlborg G, Jr., Bernhardsson S. Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients' Experiences. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(13). [CrossRef]

- Manferdelli G, La Torre A, Codella R. Outdoor physical activity bears multiple benefits to health and society. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. 2019;59(5):868-79. [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter UK, Palsdottir AM, Burls A, Chermaz A, Ferrini F, Grahn P. Nature-Based Therapeutic Interventions. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2011. p. 309-42.

- Nisbet E, Zelenski JM, Murphy SA. The Nature Relatedness Scale. Environment and Behavior. 2009;41(5):715-40.

- Mayer FS FC, more S. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2004;24(4). [CrossRef]

- Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012;2(2):1143-211. [CrossRef]

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet (London, England). 2012;380(9838):219-29. [CrossRef]

- Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, Dalal H, Dean SG, Jolly K, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017;6(6):Cd007130. [CrossRef]

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. International journal of nursing studies. 2013;50(5):587-92.

- Shanahan DF, Astell-Burt T, Barber EA, Brymer E, Cox DTC, Dean J, et al. Nature-Based Interventions for Improving Health and Wellbeing: The Purpose, the People and the Outcomes. Sports (Basel, Switzerland). 2019;7(6). [CrossRef]

|

Citation details, country of origin (where study was conducted) Publication type Study design Inclusion criteria Recruitment method Participants (number, gender, age, comorbidities etc.) Intervention (incl. nature exposure and control conditions if any) Duration of the interventions Outcomes (quantitatively or qualitatively assessed) |

| Study | Intervention –incidental or intentional interaction with nature | Participants |

Dosage/ frequency |

Study design | Primary outcome | |

|

Frühauf et al. Austria, 2015 (36) |

Nordic walking | Incidental Interaction |

Mild to moderate depression (n=22) | 60 -min sessions | A within-subjects experimental study | Feeling Scale Felt Arousal Scale Pre and post treatment. |

|

Gibbs et al. United Kingdom, 2022 (37) |

Surfing activities | Intentional Interaction | Acquired Brain Injury (n=18) | 1 two-hour session per week in 5 weeks | A qualitative evaluation design | Semi-structured interviews The interviews were conducted after the intervention. |

|

Huber et al. Austria, 2019 (38) |

Hiking in the mountains | Intentional interaction | Low back pain (n=80) | 5 hours hiking 5 days in a row | A randomised controlled clinical trial with three arms | The Back Performance Scale, The Spine-Check Score MediMouse Pre and post treatment + 4 months follow-up |

|

Kang et al. South Korea, 2015 (39) |

Forest bathing with neck-exercise | Incidental interaction |

Posterior neck pain (n=64) | Forest bathing + 4 hours stretch and exercise. 5 days in a row | Comparative Intervention study | Neck disability index and visual analogue scale pain. On the first day and last day of the experiment |

|

Liu-Ambrose Canada, 2022 (47) |

Outdoor walk or jog | Incidental interaction |

Mild cognitive impairment (n=68) | 3 times per week for 12 weeks | Randomised controlled trial | Motor function Pre and post treatment + 3 months follow-up |

| López-Pousa et al. Spain, 2015 (40) | 1.25 kilometre walks | Intentional interaction | Fibromyalgia (n= 34) | 1.25 kilometre walks between 5 and 6 pm for 6 days | A randomised single-blind clinical trial of two groups | Blood pressure, heart rate Pre and post each walk |

|

Miller et al. USA, 2021 (41) |

Outdoor walking | Incidental interaction |

Adolescent and young adult survivors of any cancer (n=19) | Outdoor walking 30-50 min, 4 times in total. |

A randomised cross-over group pilot trial | Physical activity measured by ActiGraph Baseline, 2 weeks after the first two exercise sessions, and 2 weeks after the last two exercise sessions. |

|

Noushad et al. Pakistan, 2019 (42) |

Walk | Intentional interaction | Post-traumatic stress disorder (n=262) | 50-min walk session. 5 times per week (total 12 weeks; 3 months) |

Randomised control trial | Traumatic Stress Scale Baseline and 3month follow-up |

|

Serrat et al. Spain, 2020 (43) |

Nordic walking | Intentional interaction | Fibromyalgia (n=169) | 12 weeks. Once a week. 2 hours duration | A Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial | The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire Baseline, 6 weeks (half-way)and Post-treatment |

|

Song et al. Japan, 2015 (44) |

Forest walk | Intentional interaction | Hypertension (n=20) | One walk each place, about 17 minutes, for two consecutive days | A within-subject experimental intervention Pilot Study | Heart rate variability and heart rate 1-min intervals measures over the entire 17-min course |

|

van den Berg et al. the Netherlands, 2021 (45) |

Walk and talk | Intentional interaction | Burnout/stress (n=40) | Four individually guided walks of 1.5 hours | A mixed method quasi-experimental design with a control group | The emotional exhaustion and distance scales of the Utrecht Burnout Scale. Before first walk, after second walk, and after therapy. |

|

Wen et al. China, 2020 (46) |

Outdoor-assisted walking training | Incidental interaction |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (N=60) | 15 min twice a day for four weeks | A randomised controlled trial | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second Pre and post treatment |

| Acute effects of outdoor physical activity on affect and psychological well-being in depressed patients. A preliminary study | |

|

Frühauf et al. Austria, 2015 (36) |

Peer-review A within-subjects experimental study (A preliminary study) |

| Mild to moderate depression (n=22) 8 patients dropped out due to acute sickness (4), early release (2), incomplete questionnaires (1), or different disease pattern (1) and were therefore excluded from the data analyses. 14 included in the analysis. 6 male, 8 female. 32.7 ± 10.8 years Recruited during treatment in a mental health centre | |

|

Riding the wave into wellbeing: A qualitative evaluation of surf therapy for individuals living with acquired brain injury | |

|

Gibbs et al. United Kingdom, 2022 (37) |

Peer-review A qualitative evaluation design gathering details accounting for service users experiences of the surfability intervention |

| Acquired Brain Injury. 18 included 15 participated in the interviews. Age: Mean = 42.4; Standard Deviation 12.88; Age range (29–69 years); Median = 38. Male = 10; Female = 5 (Type: Traumatic Brain Injury n = 8; Mild Acquired Brain Injury n = 1; Pontine Cavernoma Bleed to the brain n = 1; Subarachnoid Haemorrhage n = 1; Multiple Sclerosis n = 1) Time Since Injury: Mean = 2 years and 9 months; Standard deviation = 3.07; Range = 6 months– 12 years; Median = 2 years Employment Status: Employed n = 3; Employed but on sickness leave; n = 2; Medically retired n = 3; Unemployed n = 7. As part of their ongoing treatment and rehabilitation, patients were invited to attend one of three Surfability interventions | |

| Green exercise and mg-ca-SO4 thermal balneotherapy for the treatment of non- specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial | |

|

Huber et al Austria, 2019 (38) |

Peer-review A randomized controlled clinical trial with three arms |

| Low back pain (LBP) patients (n=80) 19 to 65 years old. 35 men, 45 women The participants were recruited all over Austria through communication via the Wasser Tirol web page, advertisements in newspapers, and by physicians. | |

| Relief of Chronic Posterior Neck Pain Depending on the Type of Forest Therapy: Comparison of the Therapeutic Effect of Forest Bathing Alone Versus Forest Bathing With Exercise | |

|

Kang et al. South Korea, 2015 (39) |

Peer-review Comparative Intervention study |

| Posterior neck pain (more than VAS 4, lasted for more than 3 months) (n=64) Age: Forest bathing with exercises: 54.8±9.78. Forest bathing: 50.0±14.93 11 male, 53 female Visitors at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Hanyang University Medical Center in May 2013 whom met certain inclusion criteria were recruited through a notice in the hospital, by phone, or by email | |

| Supporting Aging Through Green Exercise | |

|

Liu-Ambrose Canada, 2022 (47) |

Online register of planned trial Randomized controlled trial |

| Mild cognitive impairment (n=68) 65-80 years Recruitment method not described. | |

| Sense of Well-Being in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Aerobic Exercise Program in a Mature Forest—A Pilot Study | |

|

López-Pousa et al Spain, 2015 (40) |

Peer-review A randomized single-blind clinical trial of two groups |

| Fibromyalgia (n= 34 (4 dropouts)) Age: 62.3 years (SD = 7.7) 20-70 years old. All participants were women People with fibromyalgia, belonging to the Garrotxa Association of Chronic Fatigue and Fibromyalgia were invited to participate | |

| Cancer survivors exercise at higher intensity in outdoor settings: The GECCOS trial | |

|

Miller et al. USA, 2021 (41) |

Peer-review A randomized cross-over group pilot trial |

| Adolescent and young adult survivors of any cancer (n=19) Age: 19.7 (13.3-27.6). 9 male, 10 female. Participants recruited from the University of Minnesota Childhood Cancer Survivor Program Research Database and from survivors receiving follow-up care at the University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital and Masonic Cancer Center Clinic. Eligible survivors were invited through mailings, emails, and phone calls | |

| Effect of nature-based physical activity on post-traumatic growth among healthcare providers with post-traumatic stress | |

|

Noushad et al. Pakistan, 2019 (42) |

Peer-reviewed Randomized control trial |

| Patients with a traumatic event in the last 12 months (n=262) Age: Walking group: 33.14 +/-9.45 (SD). Sitting group: 32.41 +/- 9.84 (SD) Male: 129 (58 Walking, 71 sitting) Female: 133 (73 walking, 60 sitting) Participants were recruited from five tertiary health care facilities based in Karachi, Pakistan. Participants were invited to the study through advertisements on the notice board of each centre | |

| Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Treatment for Fibromyalgia Based on Pain Neuroscience Education, Exercise Therapy, Psychological Support, and Nature Exposure (NAT-FM): A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial | |

|

Serrat et al. Spain, 2020 (43) |

Peer-review A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial |

| Fibromyalgia (n=169) Age: TAU + NAT-FM-group: 54.12 (8.62), TAU: 53.15 (9.06) Sex: TAU + NAT-FM- group: 1 male, 81 female , TAU-group: 85 female Patients visited consecutively by the physical therapist of the Central Sensitivity Syndromes Unit (CSSU) at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) were recruited from November to December 2020 | |

| Effect of Forest Walking on Autonomic Nervous System Activity in Middle-Aged Hypertensive Individuals: A Pilot Study | |

|

Song et al. Japan, 2015 (44) |

Peer-review A within-subject experimental intervention Pilot Study |

| Hypertension (n=20) (5 had a high-normal blood pressure (systolic 130–139 mmHg or diastolic 85–89 mmHg, 10 had hypertension stage 1 (systolic 140–159 mmHg or diastolic 90–99 mmHg, 5 had hypertension stage 2 (systolic 160–179 mmHg or diastolic 100–109 mmHg) Mean age, 58.0 ± 10.6 years; Male 20, female: 0 Recruitment method not mentioned | |

| Walk it off! The effectiveness of walk and talk coaching in nature for individuals with burnout- and stress-related complaints | |

|

van den Berg et al. the Netherlands, 2021 (45) |

Peer-review A mixed method quasi-experimental design with a control group |

| Burnout/stress (n=40) Age: Intervention group 42.05 (SD 1.85), control group: 44.00 (SD 2.55). 9 male, 31 female Participants who registered for a walk and talk coaching program called ‘discover your talent’ were invited to participate in the study | |

| Effect of a Rehabilitation Garden on Rehabilitation Efficacy in Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | |

|

Wen et al. China, 2020 (46) |

Peer-review A randomized controlled trial |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (N=60) Age: Intervention 63.74±3.24, Control: 64.10±3.56, Male 29, female 31 (Intervention 14/16, control: 15/15) Recruitment method not described | |

| Study | Intervention | Comparison |

|---|---|---|

|

Frühauf et al. Austria, 2015 (36) |

Walking outdoors using the Nordic walking technique 60-min sessions. One for each condition All conditions (60 min each) were carried out as a group. Provided face to face by physiotherapists |

Sitting indoor or cycle on a cycle ergometer |

|

Gibbs et al. United Kingdom, 2022 (37) |

Surfing activities Face to face In groups of no more than 5 participants Groups were led by three qualified surf instructors, two staff therapists plus volunteers One two-hour sessions per week in five weeks |

No comparison |

|

Huber et al Austria, 2019 (38) |

Hiking tours in the mountains Face to face in groups about 10 physiotherapeutic executed the treatments From Sunday to Friday: a daily 5 hours guided hiking tours from 6.92 to 15.20 and a total of 60.93 kilometres, via various elevations gains in terrain above sea level |

Same as intervention group plus balneotherapy or balneotherapy alone. The baths in a tub lasted 20 min every afternoon Face to face in groups about 10 physiotherapeutic executed the treatments From Sunday to Friday: a daily 5 hours guided hiking tours from 6.92 to 15.20 and a total of 60.93 kilometres, via various elevations gains in terrain above sea level |

|

Kang et al. South Korea, 2015 (39) |

Forest bathing with neck-exercise (FBE) 2 + 2 hours a day The FBE programme: 10-minute warm-up, 30 minutes of main exercise and a 10-minute cool down. Subjects rest for 10 minutes and then repeat the exercise programme, so the total exercise time is 2 hours. The warm-up exercise: light stretching; the cervical and shoulder regions and the whole body were included. The main exercise: intensity gradually increased. Stretching exercises focusing on the cervical and shoulder regions. Although the cool down exercise is composed of only stretching, the intensity is higher than that of the main exercise This exercise program was developed and organized by a committee composed of four physicians specializing in rehabilitation medicine, and three physical therapists after a literature review Five days in a row |

Forest bathing alone 2 times 2 hours a day in the same forest as the intervention group |

|

Liu-Ambrose Canada, 2022 (47) |

Outdoor walk or jog on forest trails at pre-determined route in trails of an urban forest (Pacific Spirit Park) Each session will consist of 10 min of warm-up, 40 min of aerobic exercise, and 10 min of cool-down. For both OP and IP, aerobic exercise will be progressive and of moderate intensity Group-based training face-to-face by instructors with a relevant background and first aid certification. Both OP and IP training groups will have a participant to instructor ratio of 3:1 A 12-week, 3x/week program |

60 minutes indoor walking on a treadmill at the Exercise Prescription Suite of the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility (CHHM) |

| López-Pousa et al Spain, 2015 (40) |

1.25 kilometre walks in young forest The walks were performed through flat areas in these woods Delivered face-to-face accompanied by two nurses The walks were conducted in the evenings between 5 and 6 pm during six days |

1.25 kilometre walks in mature forest The walks were performed through flat areas in these woods Delivered face-to-face accompanied by two nurses The walks were conducted in the evenings between 5 and 6 pm during six days |

|

Miller et al. USA, 2021 (41) |

Outdoor walking compared to indoor walking for 30-50 min for each session Four group exercise sessions two indoor sessions and two outdoor sessions Face-to-face in groups session included an introduction prior to the exercise. Participants were encouraged to socialize during the exercise and at a meal provided after each exercise session Two young adult survivors were hired as peer leaders for the group exercise sessions |

Indoors walking for 30-50 min for each session All indoor exercise sessions were completed in the tunnels and skyways at the University of Minnesota Face-to-face in groups session included an introduction prior to the exercise. Participants were encouraged to socialize during the exercise and at a meal provided after each exercise session Two young adult survivors were hired as peer leaders for the group exercise sessions |

|

Noushad et al. Pakistan, 2019 (42) |

A walk-in nature Stretching exercise sessions 10 min, followed by a 50-min walk: 5 km walk following a route with a track map at a moderate pace No personal guidance 5 times per week (total 12 weeks; 3 months). Compared to 3 months of 60 min nature-based sitting |

Sit-in nature for 50 minutes No personal guidance 5 times per week (total 12 weeks; 3 months) |

|

Serrat et al. Spain, 2020 (43) |

The active group received exercise therapy (Nordic walking), pain neuroscience education, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness training, and nature exposure. All elements carried out in nature Provided face-to-face delivery in groups by a physiotherapist, a psychologist, and a sports technician 12 weeks. Once a week. 2 hours duration |

Exercise therapy (Nordic walking), pain neuroscience education, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness training, and nature exposure. All elements carried out indoors Provided face-to-face delivery in groups by a physiotherapist, a psychologist, and a sports technician 12 weeks. Once a week. 2 hours duration |

|

Song et al. Japan, 2015 (44) |

Forest walk After resting for 10 min, the participants were instructed to walk a predetermined course Face-to-face in groups. Two experimenters guided the participants along the course, at almost the same speed One walk each place, about 17 minutes, on two consecutive days |

City walk Face–to-face in groups. Two experimenters guided the participants along the course, at almost the same speed One walk each place, about 17 minutes, on two consecutive days |

|

van den Berg et al. the Netherlands, 2021 (45) |

Walk and talk coaching trajectory consisting of four individually guided walks supplemented with individual assignments. Intervention: four individually guided walks, of 1.5 hours followed by a coach. Coaches had no specific training for nature-based coaching The programme lasts between 12 and 18 weeks (1 walk per 3–4 weeks) |

No intervention |

|

Wen et al. China, 2020 (46) |

Outdoor-assisted walking training The training distance was 500 m per training, walking training barefooted on a cobblestone path with an uneven surface, outdoor stair training and horizontal bar training, including horizontal ladder movements, pull-ups, overhanging chest-expanding, and left-lifting (according to their abilities). The training time was 15 min, and the exercise was performed twice daily Face-to-face in groups under the guidance of therapists at the Fifth People’s Hospital of Foshan, Foshan, China 15 min twice a day for four weeks |

Indoor function training for pulmonary rehabilitation including: aerobic exercise i.e. indoor cycling ergometry (medium speed, rest for 1 min after every 4 min of exercise, 15 min/day); breathing exercises, namely abdominal breathing exercise, pursed lip breathing, chest breathing exercise, and relaxation shoulder strap exercise repeated 10 times with each exercise; and (iii) cough training and resistance breath training for 15 min/day Face-to-face in groups under the guidance of therapists at the Fifth People’s Hospital of Foshan, Foshan, China 15 min twice a day for four weeks |

| Study | Intervention | Rationale for nature intervention | Considerations or arguments for the inclusion of nature elements |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Frühauf et al. Austria, 2015 (36) |

Walking outdoors using the Nordic walking technique Mild to moderate depression (n=22) The evidence shows that physical activity (PA) might be an effective treatment for depression and PA has been recommended as part of the latest guidelines on depression from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Can (PA) immediately improve affect and/or help an individual to feel more energetic |

Active exposure to natural environments elicits more positive effects on mental well-being and mood enhancing effects after PA in an outdoor environment than in an indoor setting is greater | Walking outdoor along a path outside the hospital area through a green, natural environment |

|

Gibbs et al. United Kingdom, 2022 (37) |

Surfing activities Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) (n=18) Holistic neurorehabilitation considering the dynamic relationship between a person and the person’s environment, and respecting the reciprocal relationships that exist between psychological, social, cognitive, and physical domains of well-being following injury The aim of this study is to characterise the experiences of a surfing intervention in individuals living with the residual effects of brain injury, and to reflect on potential mechanisms through which reported improvements in well-being may function in a conceptual model |

The Attention Restoration Theory emphasises the restorative effects of spending time in nature on attention and concentration which may be particularly useful for people with ABI Exposure to unthreatening natural environments help to reduce physiological arousal following stress and increase resilience, in line with stress reduction theory. The potential for nature to facilitate resilience may be particularly important in the context of brain injury populations. Nature can meaningfully reduce psychological and physiological markers of stress and replace them with feelings of refreshment and vigour Contact with nature has also been shown to improve cognitive functioning and facilitate the experience of psychological flow and there is now a growing body of evidence for the wellbeing benefits associated with engagement in water-based activities |

Surfability UK is located at Caswell Bay on the Gower Peninsula of South Wales The intervention ran during the latter months of each year (July-October 2018-2020) in accordance with the optimum sea temperature and seasonal weather conditions |

|

Huber et al Austria, 2019 (38) |

Hiking tours in the mountains. Low back pain (LBP) patients (n=80) Physical activity has proven effect in pain, muscle strength, and quality of life in patients with LBP |

Restorative effects of spending time in nature on attention and concentration and pain relief Current evidence on green exercise refers to three main areas: regulation of immunological and physiological (stress) responses, improvement of psychological states, and facilitation of health-promoting behaviour Despite limited available data, there is encouraging evidence that balneo or spa-therapy may be effective in the treatment of LBP |

The village of Grins (Tyrol, Austria, 47°08′30.1′′N 10° 30′55.2′′E) is chosen for the mountain tracks and climbs, air, and sight |

|

Kang et al. South Korea, 2015 (39) |

Forest bathing with neck-exercise Posterior neck pain (n=64) It has been shown that stretching and strengthening exercises are helpful for relieving posterior neck pain |

Forest bathing was reported to have a positive impact on blood pressure and salivary cortisol level in elderly patients with hypertension, and therapeutic effects in patients with psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and stress. Forest bathing may ameliorate chronic posterior neck pain and showed significantly reduced pain in a forest bathing group compared with a group going about daily life in a city | A forest -no further description |

|

Liu-Ambrose Canada, 2022 (47) |

Outdoor walk or jog on forest trails Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (n=68) Aerobic exercise is an evidence-based approach to mitigate cognitive decline in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) |

Spending time in nature has a positive effect on cognition and stress reduction | Forest trails at pre-determined route in trails of an urban forest (Pacific Spirit Park) |

| López-Pousa et al Spain, 2015 (40) |

1.25 kilometre walks in young forest or mature forest Fibromyalgia (FM) (n= 34) Some physiological studies support the hypothesis that walking has positive effects on pain, quality of life, and depression |

Studies support the hypothesis that walking in the woods supports the central nervous system, autonomic nervous system, and endocrine system, increasing the immune response, affecting hypertension, and positively influencing non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients People with FM performing moderate exercise in therapeutic forests exhibit a significant improvement in their clinical symptoms when compared with the same type of exercise in younger forests |

The two forests are located in the Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park, specifically between Olot and the beech forest in Jordà (Northeast of Girona, Spain) A young forest presents only first age classes species. Usually, it is a forest with a homogeneous dense or very dense structure and impenetrable undergrowth A mature forest: the absence of timber exploitation during at least the last 4 or 5 decades has allowed reaching a more advanced and complex structure, with a wider range of age groups, including old trees with a large diameter (usually over 100 years). The closure of the crowns of the trees causes little undergrowth. This composition allows a wide biodiversity and an ecosystem that includes many more types of lichens, fungi, mosses, invertebrates, and their predators, that is, all the flora and fauna in the natural evolution of a forest |

|

Miller et al. USA, 2021 (41) |

Outdoor walking compared to indoor walking for 30-50 min for each session Adolescent and young adult survivors of any cancer (n=19) Survivors of childhood cancer report even less physical activity than sibling controls. Yet, regular exercise is protective against many chronic diseases and is associated with a lower risk of mortality, psychological burden, and cognitive impairment in survivors. |

As a way to improve intervention effectiveness, interest has grown around the health and motivation benefits of performing physical activity outdoors: termed “Green Exercise". In the general population, Green Exercise has been associated with increased intention to exercise and mental health benefits: decreases in tension or depression and increases in energy and self-esteem | All outdoor exercise sessions were completed at a large park in Minneapolis. No further description |

|

Noushad et al. Pakistan, 2019 (42) |

A walk-in nature compared to sit-in nature Patients with a traumatic event in the last 12 months (n=262) Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is believed to improve individual physical health and benefit immune, nervous, and other systems. PTG usually involves the development of personal functioning and well-being that surpasses pre-trauma levels. Physical activity has become a realistic and safe therapy for trauma patients to improve psychological and somatic quality of life |

Mankind has utilised nature to cure or to deal with stress. Several studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between nature and healing from PTS. It has been suggested that the exposure to nature accounted for the reduction in cognitive fatigue and stress levels, increased focus, decline in adverse effects, decreased sympathetic nervous system activity, restored neurotrophins, reduced inflammation, etc., thus counted therapeutic to the trauma associated pathology. |

The safari park covers 148 acres (0.60 km2); it has a zoo geared with woodland, mountain viewing, safari tracks, and two natural lakes The experiment took place in winters and spring with an average temperature between 22° and 25°C |

|

Serrat et al. Spain, 2020 (43) |

The active group received exercise therapy (Nordic walking), pain neuroscience education, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness training and nature exposure Fibromyalgia (FM) (n=169) Education, mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy have shown good effect in FM patients with FM. |

Reason: Therapeutic programmes based on activities in nature have shown promise for improving mental health. Likewise, it has been proposed that practice in a natural context could increase adherence to therapies based on the practice of physical activity. Components as hiking, Nordic walking and Shinrin Yoku are for outside | The geographical areas were Sant Genís Forest and Les Escletxes del Papiol, Barcelona, Spain The therapists are not educated in integrating nature in the interventions |

|

Song et al. Japan, 2015 (44) |

Forest walk compared to city walk Hypertension (n=20) Studies have demonstrated that walking is beneficial for hypertension |

A forest environment can have positive physiological and psychological effects. When compared with an urban environment, viewing forest scenery or walking in forests can decrease cerebral blood flow in the prefrontal cortex, reduce blood pressure and pulse rate, increase parasympathetic nerve activity, suppress sympathetic nerve activity, and decrease salivary cortisol concentrations of stress hormones. As interest in improving health and QOL has increased, more attention has been focused on the role of nature in promoting human health and well-being. In particular, a great deal of attention is focused on the therapeutic effects of the forest environment or “forest therapy”. Forest therapy uses the medically proven effects of walking in a forest and observing the environment to promote feelings of relaxation and improve both physical and mental health. | The forest walk was located in Agematsu town of Nagano Prefecture situated in central Japan. A forest including many Japanese cypress trees. The walking course in the forest area was mostly flat, except for a small slope An urban area in Ina City of Nagano Prefecture was selected as the control site. The urban walking area was flat The weather was sunny on the days of experiments. In the forest area, the average temperature was 21.4° ± 1.2°C with an average humidity of 82.3 ± 4.8%, whereas in the urban area, the average temperature was 28.1° ± 1.1°C with an average humidity of 61.9 ± 4.5% |

|

van den Berg et al. the Netherlands, 2021 (45) |

Walk and talk coaching trajectory consists of guided walks supplemented with individual assignments compared to no intervention Burnout/stress (n=40) During walk and talk coaching, clients are engaging in walking as a moderate physical activity. Physical activity - as opposed to sedentary behaviour - has been found positively related to mental health on its own. |

Natural environments can mitigate the detrimental effects of stress on mental health Exposure to natural environments has pronounced benefits for healthy individuals, but even more so for those suffering from mental health issues. |

At the country estate “Amelisweerd” in the Netherlands The nature estate serves both as a natural background for the programme and as a metaphor and source of inspiration for discussing problems and challenges. For example, the coach may point at a tree that has fallen on the path and ask what the client would do if she or he would encounter such a situation in his or her life. Or use changes that come with the season, such as falling leaves, as a starting point for discussing how the client copes with the passing of time and getting older |

|

Wen et al. China, 2020 (46) |

Outdoor-assisted walking training versus indoor function training for pulmonary rehabilitation Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)(N=60) Pulmonary rehabilitation, stabilizing clinical symptoms and preventing disease progression is considered as one of the important treatments for patients with stage II and higher COPD |

A multidisciplinary combination of garden science, clinical medicine, and engineering, outdoor rehabilitation provides an adjuvant therapy | No further description |

|

Frühauf et al. Austria, 2015 (36) |

Acute effects of outdoor physical activity on affect and psychological well-being in depressed patients. A preliminary study |

| Feeling Scale (FS) measuring affective valence. The FS is a single-item rating scale with anchors at zero (“Neutral”) and at all odd integers, ranging from “Very good” (+5) to “Very bad” (-5) Felt Arousal Scale (FAS) measuring Perceived activation. A single-item rating scale ranges from 1 (“low arousal”) to 6 (“high arousal”) Mood Survey Scale (MSS) assesses mood states with 8 subscales (activation, elation, calmness, contemplativeness, excitation, anger, fatigue, depression) and consists of a total of 40 items answered in 5-point Likert-type scales Measurement points: pre-treatment and post treatment | |

|

Gibbs et al. United Kingdom, 2022 (37) |

Riding the wave into wellbeing: A qualitative evaluation of surf therapy for individuals living with acquired brain injury |

| Semi structured interviews were conducted face-to-face in a hospital setting in 12 patients and three were conducted via telephone by one of two Assistant Psychologists The interviews were conducted after the intervention | |

|

Huber et al Austria, 2019 (38) |

Green exercise and mg-ca-SO4 thermal balneotherapy for the treatment of non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial |

| The functional spinal mobility was measured by parts of the Back Performance Scale, assessment of mobility-related activities in patients with back pain (maximum possible value per test: 3 points). Trunk rotation measurement measured sitting on a treatment bed with a digital goniometer Questionnaires: Oswestry Low Back Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36, modified Visual Analogue Scale, World Health Organization Well-Being Index In a pain diary, the use of pain medication was documented during the whole study period. Furthermore, the days of incapacity to work and the number of medical consultations due to cLBP in the last months were assessed. These three parameters were collected two times (day 0 and day 120) Measurement points: at the beginning and end of the one-week intervention, as well as 4 months after the intervention. Pain diary during the whole study period (4 months) | |

|

Kang et al. South Korea, 2015 (39) |

Relief of Chronic Posterior Neck Pain Depending on the Type of Forest Therapy: Comparison of the Therapeutic Effect of Forest Bathing Alone Versus Forest Bathing With Exercise |

| VAS on that day, VAS over the previous week, neck disability index (NDI), EuroQol 5D-3L VAS (EQ VAS) and index (EQ index), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), the number of trigger points in the posterior neck region (TRPs), and C-ROM Measurement points: on the first day of the experiment and on the last day of the experiment. All tests were performed by the same physicians | |

|

Liu-Ambrose Canada, 2022 (47) |

Supporting Aging Through Green Exercise |

| Motor function, emotional well-being, health-related behaviours, and quality of life Measurement points: at baseline and at trial completion. Follow-up measurement of questionnaire-based outcomes will occur via email or phone at 3 months following trial completion. Participants will also subjectively monitor workout intensity using the 20-point Borg's Rating of Perceived Exertion | |

| López-Pousa et al Spain, 2015 (40) | Sense of Well-Being in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Aerobic Exercise Program in a Mature Forest—A Pilot Study |

| Blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and temperature of the participants were determined at the beginning and end of each walk. The Spanish version of the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR), Spanish version of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), questionnaire on the symptomatic progression of fibromyalgia during the last 15 days at the end of the trial, specifying the days of generalized discomfort, the days of intense pain, the presence of insomnia, and the number of days during which they experienced well-being. A questionnaire including a self-assessment of the study benefits composed of 9 items with a 0 (negative)–10 Measures relating to environmental conditions of the forests, such as temperature (in degrees Celsius), luminosity (in lux), noise (in decibels), and atmospheric pressure (in hectopascals) were recorded thirty minutes prior to each session Blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and temperature of the participants were determined at the beginning and end of each walk. (FIQR) and (STAI) were administered on the first and last day of intervention | |

|

Miller et al. USA, 2021 (41) |

Cancer survivors exercise at higher intensity in outdoor settings: The GECCOS trial |

| Physical activity (PA) was measured using Actigraph GT3x accelerometers worn on the hip for 7 days at baseline, 2 weeks after the first two exercise sessions, and 2 weeks after the last two exercise sessions and during each exercise session The Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise (PNSE) is an 18-item validated survey that assesses the Self-Determination Theory constructs of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The behaviour regulation in exercise questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2) is a 19-item validated survey that assesses the Self-Determination Theory construct of exercise motivation. The fatigue scale-adolescent (FSA) is a 13-item validated survey to assess fatigue in patients and survivors of cancer Measurement points: PA, motivation, and fatigue were measured three times throughout the study: before the first two sessions, after the first two sessions, and after the second two sessions | |

|

Noushad et al. Pakistan, 2019 (42) |

Effect of nature-based physical activity on post-traumatic growth among healthcare providers with post-traumatic stress |

| Physiological measures (body mass index [BMI], heart rate [HR], diastolic and systolic blood pressure [SBP]), and biochemical measures (C-Reactive Protein (CRP), BDNF, IL-6, cortisol, and heart rate variability (HRV)). Traumatic Stress Scale (TSS) measures exposure to any trauma Post Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) a 21-item survey, including factors of new possibilities, relating to others, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life Measurement points: baseline and 3 month follow-up | |

|

Serrat et al. Spain, 2020 (43) |

Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Treatment for Fibromyalgia Based on Pain Neuroscience Education, Exercise Therapy, Psychological Support, and Nature Exposure (NAT-FM): A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial |

| Primary outcome: The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire revised (FIQR) Secondary outcome: The visual analogue scale (VAS) (both pain and fatigue), the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), the physical functioning component of the 36-item short form survey (SF-36), the positive affect and negative affect schedule (PANAS), the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) and the perceived stress scale (PSS-4) Process variables: The Tampa scale for kinesiophobia (TSK), the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS), the personal perceived competence scale (PPCS) and the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ) Measurement points: baseline, 6 weeks (half-way) and post treatment | |

|

Song et al. Japan, 2015 (44) |

Effect of Forest Walking on Autonomic Nervous System Activity in Middle-Aged Hypertensive Individuals: A Pilot Study |

| HRV and heart rate. In this study, two broad HRV spectral components were calculated: low frequency (LF; 0.04–0.15 Hz) and high frequency (HF; 0.15–0.40 Hz). The Profile of Mood State (POMS) RV and heart rate data were collected at 1-min intervals and then averaged over the entire 17-min course | |

|

van den Berg et al. the Netherlands, 2021 (45) |

Walk it off! The effectiveness of walk and talk coaching in nature for individuals with burnout- and stress-related complaints |

| Burnout: The emotional exhaustion and distance scales of the Utrechts Burnout Scale. Bore-out: The Dutch Boredom Scale measures boredom at work and consists of 6 items. Mental health problems: The Dutch version of the four dimensional symptom questionnaire. Concentration and social functioning: Two subscales from the Dutch questionnaire functioning when exhausted were added to measure concentration and attention. Pleasure at work: A single item question measured pleasure at work. Work engagement: The positive counterpart of burnout is engagement with work. State hope: The Adult State Hope Scale. State self-esteem: Self-esteem was measured with the State Self- Esteem Scale Mindfulness: The short (14-item) Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory. Satisfaction with life: The Cantril ladder measures satisfaction with life subjective Health: A single-item question from the SF-36 scale Measurement points: before the first walk (at baseline), after the second walk (after approximately 8–10 weeks), and after the therapy | |

|

Wen et al. China, 2020 (46) |

Effect of a Rehabilitation Garden on Rehabilitation Efficacy in Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| Exercise capacity, lung function, symptoms, psychological state, and the Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise (BODE) comprehensive index of the patients before and after the treatment were assessed. After treatment, the intra-group 6-minute walk test (6MWT), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC), the Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and the Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise (BODE) index Measurement points: before and after treatment | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).