2. Case presentation

A 34-year-old man presented with loss of consciousness and admitted to our hospital. His initial blood pressure was 124/65 mmHg. He had no family history and past history, but drank 3 bottles of alcohol per day. On neurological examination, his consciousness was stupor, and he showed an avoidance response to the pain stimulus. Another neurologic deficit was not observed.

Initial blood test results were total billirubin 9.09 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 4.75 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 2293 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 304 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 64 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 276 U/L, ammonia 432 ug/dL, protein 4.8 g/dL, albumin 1.9 g/dL, amylase 730 U/L, lipase 73 U/L, blood urea nitrogen 15 mg/dL, creatinine 1.04 mg/dL, prothrombin time 62.7 sec and electrolyte levels were normal. International normalized ratio was 3.18. In addition, cerebrospinal fluid tests with immunoglobulin G index and aquaporin-4 antibody results were within the reference ranges. Moderate to severe ascities were observed in abdominal computed tomography. Initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not observe abnormal lesion. We diagnosed liver cirrhosis which is classfied as Child-Pugh class C. Because lateralizing and localizing sign were not observed, it was also considered that metabolic encephalopathy due to liver failure.

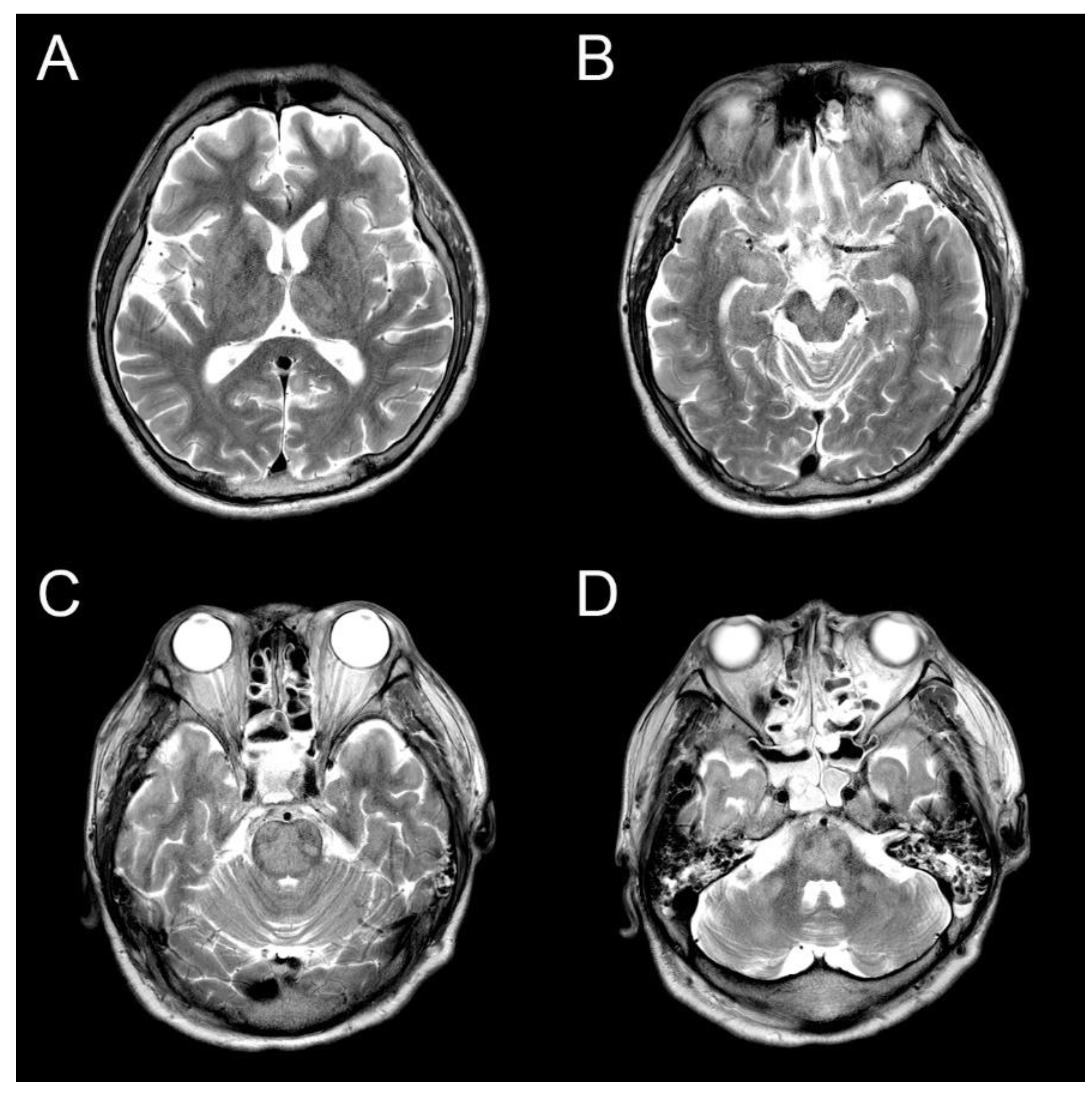

The ammonia level was initially controlled with lactulose enema, and the level was normal range on the third day of hospitalization. However, there was still no change in consciousness state. Also, progressive spastic quadriparesis and ophthalmoplegia was observed. Electroencephalography (EEG) results were continuous slow and generalized, and follow up brain MRI on the 14th day showed high signal intensity at bilateral caudate nucleus, putamen, thalami, midbrain, central pons and bilateral middle cerebellar peduncle on T2-weighted MRI (

Figure 1). The lesion with no mass effect showed hypointense on T1-weighted MRI. Contrast enhancement is not seen in lesions. These were all new findings compared to prior brain MRI during the same admission. During these periods, electrolyte levels including sodium level maintained in normal range. It was diagnosed that the ODS was secondary to rapid correction of hyperammonemia and hyperbilirubinemia without changes in serum sodium level. Consciousness was still stupor and hyperbilirubinemia was shown during conservative manegement. The guardians did not agree to additional hemodyalysis and the transplantation of the liver. Eventually, he died on the 76th day of hospitalization due to severe metabolic acidosis.

3. Discussion and Review of Literature

The current case shows a patients with ODS that occurred at bilateral caudate nucleus, putamen, thalami, midbrain, central pons and bilateral middle cerebellar peduncle due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia and hyperbilirubinemia without changes in serum sodium level.

ODS is rare and reported within 1% of patients admitted to a neurology department and 0.06% of all admissions to general medical department. ODS in adult is more common than it is in children. ODS has a similar prevalance in both males and females. In general, ODS may present with a wide range of symptoms, including progressive spastic quadriparesis, pseudobulbar palsy, pseudobulbar affect, dysarthria, dysphagia, ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, nystagmus, and cranial nerve palsies. Before presenting the symptoms of ODS, patients may have neurological symptoms of encephalopathy. These symptoms usually correct following initial correction of electrolytes. Brain MRI is the recommended diagnostic modality to evaluate ODS including CPM and EPM. Furthermore, sequential brain MRI is recommended to perform over a period of weeks to months to reveal the progression or regression of the demylinating lesion depending on clinical symptoms. ODS is caused by rapid sodium correction of more than 12 mEq/L per day. Rapid correction of hyponatremia results in a rapid change in osmotic gradient, causing moisture in the cell to escape into the extracellular space, and damages to the vascular endothelium cells and glial cells that make up the blood brain barrier. Through the damaged blood-brain barrier, cytokines, lymphocytes, complement, and vasoactive amines, which are inflammatory mediators, flow into the central nervous system, resulting in inflammatory demyelination, which is defined as ODS including CPM and EPM. However, in this case, the blood sodium level was normal range and did not fluctuate during the treatment period [

4,

5].

To estimate the rarity of case, lethal speed for correction of hyperammonemia, threshold for a lethal level of hyperbilirubinemia, the cases reported in the scientific literature were reviewed. We performed a review of all reported ODS cases from 1960 to 2023 based upon a search of English language literature using Pubmed and Google Scholar databases. The literature search criteria were ODS, CPM, EPM, correction of ammonia, hyperammonemia, and hyperbilirubinemia. Very few cases of ODS, CPM and EPM were reported in patients with rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia, which is summarized in

Table 1. In children, most cases of hyperammonemia were caused by genetic abnormalities including OTCD, but most cases in adults were caused by chronic alcoholism. Most of ODS reports on MRI is seen as T2 hyperintensity in the central pons, with sparing of the ventrolateral pons, tegmentum, and corticospinal tracts. Contrast enhancement is usually not seen. Pontine lesions are usually symmetrical and extrapontine lesions are usually bilateral and most commonly observed in cerebellar peduncles, globus pallidus, thalamus, lateral geniculate body, putamen, external and extreme capsule, splenium of corpus callosum, and supratentorial white matter. Rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia developed ODS that

both CPM and EPM occur simutaneously. Only one CPM case report due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia was identified. In general, EPM was even rarer CPM. Although,

the presence of CPM rather than EPM is directly linked to poor prognosis including locked-in syndrome, coma or death, these extensive lesion including bilateral caudate nucleus, putamen, thalami, midbrain, central pons and bilateral middle cerebellar peduncle might be associated with poor prognosis of ODS due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia.

The literature has been suggested that speed for correction of ammonia lower than 77.8 μmol /L/day showed non-lethal progenosis. Previous studies have compared the directly calculated changes in osmolarity due to changes in ammonia concentration over a 24-hour period with the safe range of osmolarity change rates due to changes in serum sodium concentration. The resulting osmolarity change rates directly caused by ammonia correction (previous cases: -0.459, -0.220, lower than -0.376 mOsm/L/day and our case: -0.077mOsm/L/day) were found to be very small in absolute value compared to the safe range of osmolarity change rates due to sodium.

Therefore, previous studied suggested

any other factor rather than osmolarity change rates directly caused by ammonia as the sole cause of ODS existed. The literature has been suggested that ammonia level higher than 204 μmol /L/day showed lethal progenosis. Cells have defense mechanisms to cope with changes in volume caused by alterations in osmolarity. In patients with hyperammonemia, glutamate plays a role in reducing intracellular ammonia by decreasing intracellular space and increasing extracellular space in the brain. Glutamate is an important osmolyte that is mainly released from cells when cell volume needs to be reduced, thereby contributing to the reduction of intracellular osmolarity. In patients with hyperammonemia, the mechanism described above can reduce the intracellular/extracellular concentration difference of glutamate, which may contribute to the disturbance of cell volume regulatory mechanisms [

9,

10].

Also, The literature review showed that only one case report with bilirubin level of 22.88 μmol /L showed non-lethal progenosis. Younger aged patients with ODS and CPM due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia had better prognosis. A poor prognosis has been observed in most adult patients with ODS and CPM due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia. Previous reports that severe hyponatremia (less than 115 mEq/L), associated hypokalemia, or low Glasgow Coma Scale score (less than 10) at presentation or ODS following liver transplant are reported to be poor prognostic factors in ODS. Also, the anatomic location and size of the demyelinating lesion are usually not associated with outcome [

6]. However, for our case report and literature review, ODS and CPM due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia observed to have poor prognosis. In present case and literature review, No effective treatment has been defined for ODS due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia. Current management consists of general supportive care.

Although it is rare, ODS may occur in the presence of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia without rapid correction of sodium level. Hyperammonemia is most commonly associated with liver disease including chronic alcoholism and urea cycle disorders. Ammonia has a small molecular weight (17.03 g/mol) and potent of neurotoxin and does not directly affect osmotic pressure. However, it upregulates aquaporin-4 of astrocytes and penetrate the blood–brain barrier resulting in edema of astrocytes. Sudden correction of ammonia may lead to aquaporin-4 dysfunction similar to chronic neuro inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica, leading to demyelinating lesions due to osmotic stress. Furthermore, hyperammonemia cause a multitude of neurotoxic effects such as cerebral edema, brain herniation and ultimately death. However, no significant correlation has yet been made between CPM and hyperammonemia [

14,

15]. In this case, rapid ammonia correction without fluctuation of sodium level was performed on the 3rd day of admission, and extensive lesion including bilateral caudate nucleus, putamen, thalami, midbrain, central pons, and both middle cerebellar peduncle were newly observed in follow up brain MRI on the 14th day. Although lesions affecting the basal ganglia, caudate nucleus, thalamus, cerebellum, and subcortical white matter are frequently observed in hyperammonemic encephalopathy, mainly insula, cigulate gyrus, and extensive cortical lesions are observed in hyperammonemic encephalopathy [

16,

17]. In regard to the treatment of hyperammonemia, lactulose, rifaximin and hemodialysis are common modalities used to lower ammonia levels, as were used in our patient. Also, alternate forms of treatment are available. For patients specifically with urea cycle disorders, nitrogen scavengers such as sodium benzoate, sodium phenylacetate, and arginine are administered for excretion of ammonia. Preventing toxicity to the brain by means of rapid removal of ammonia is the standard of care for patients presenting with urea cycle cycle disorders. However, for our case and literature review, physicians should be aware that ODS can occur when rapid correction of hyperammonemia is present in patients with liver failure.

Hyperbilirubinemia can also cause ODS. In the early stage of hyperbilirubinemia, secretion of interleukin or vascular endothelial growth factor from microvascular endothelial cells is suppressed. However, when hyperbilirubinemia persists for a long time, the production and secretion of cytokines and nitric oxide are promoted in vascular endothelial cells. As a result, hyperbilirubinemia weakens the blood-brain barrier by causing damage to vascular endothelial cells, then leading to ODS including CPM and EPM [

7,

18]. Previous report showed that high-dose methylprednisolone was initiated in an attempt to improve the integrity of the BBB by blocking inflammatory mediators. However, there was no clinical improvement. Furthermore, previous report have demonstrated that plasma exchange improves clinical outcomes in patients with ODS due to hyperbilirubinemia. However, the family of our patient did not want to treat plasma exchange.

In this case, continuous hyperbilirubinemia was observed during the treatment period, a new lesion suggesting ODS that was not observed in previous MRI. Although serum sodium level was continuously normal range and hyperammonemia was only found in the early stages of treatment, ODS caused by continuous hyperbilirubinemia could be suspected after identifying progressive spastic quadriparesis and ophthalmoplegia.

Although the change of sodium level is not significant, ODS can occur in patients with liver failure due to rapid correction of hyperammoniaemia or severe hyperbilirubinemia. Therefore, physicians pay attension to prevent occurrence of ODS during the treatment of patients with liver failure. As this was a single case report and literature review, cross-sectional retrospective observational studies are needed to accumulate further knowledge for ODS due to rapid correction of hyperammonemia or hyperbilirubinemia.