Submitted:

08 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Catalyst

2.2. Material

2.3. Pyrolysis Experiments

2.4. Analysis Methods

3. Results and Discussion

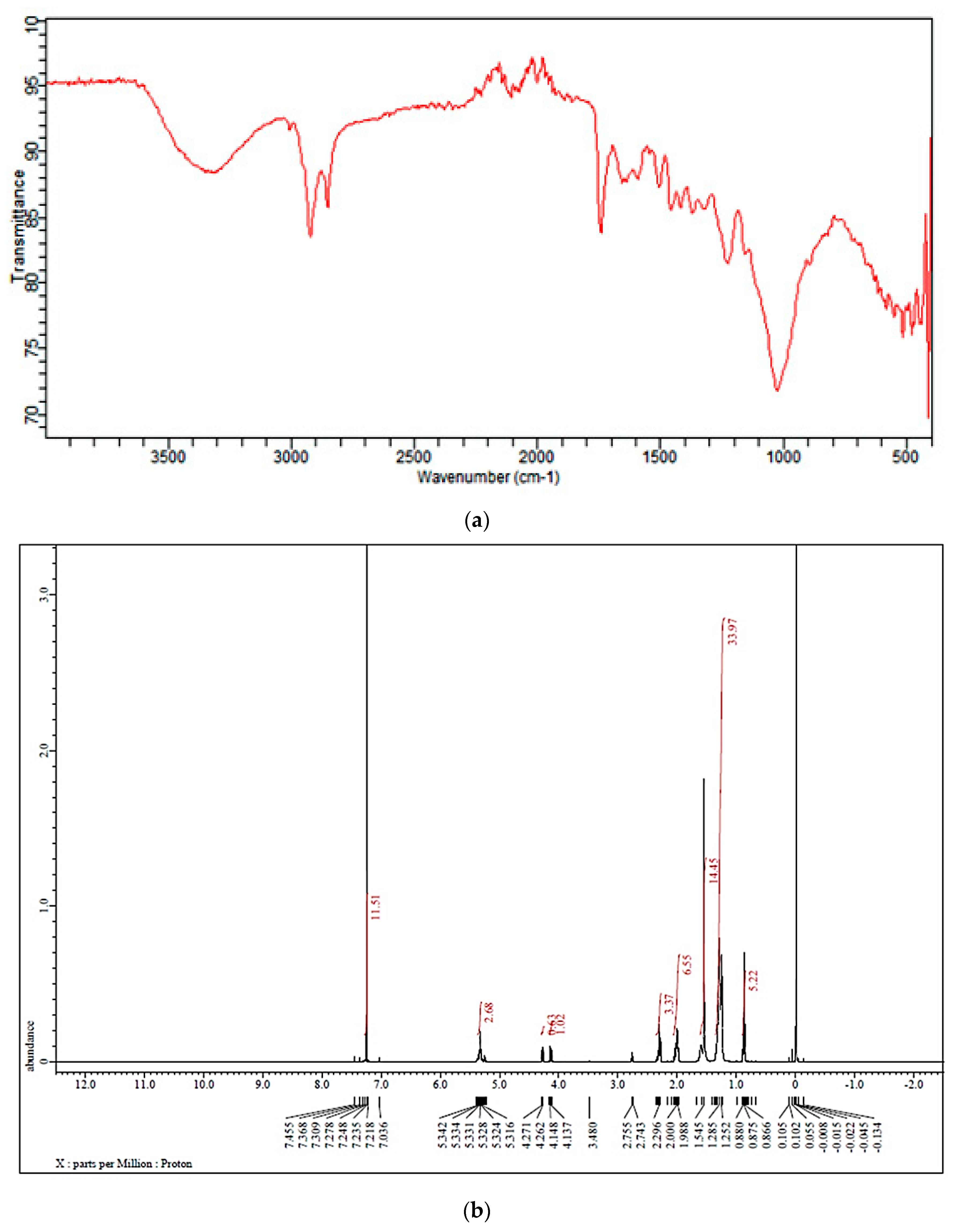

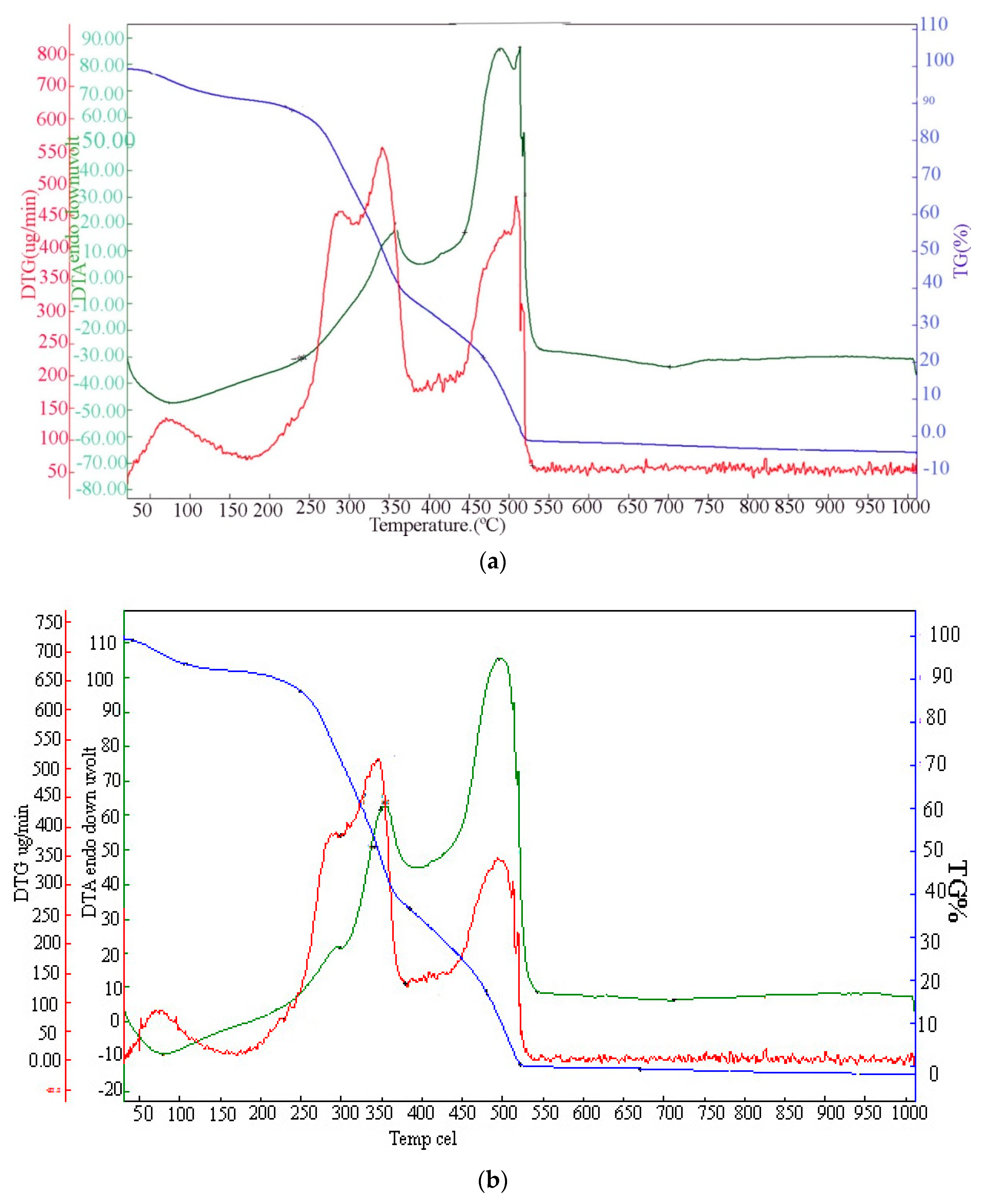

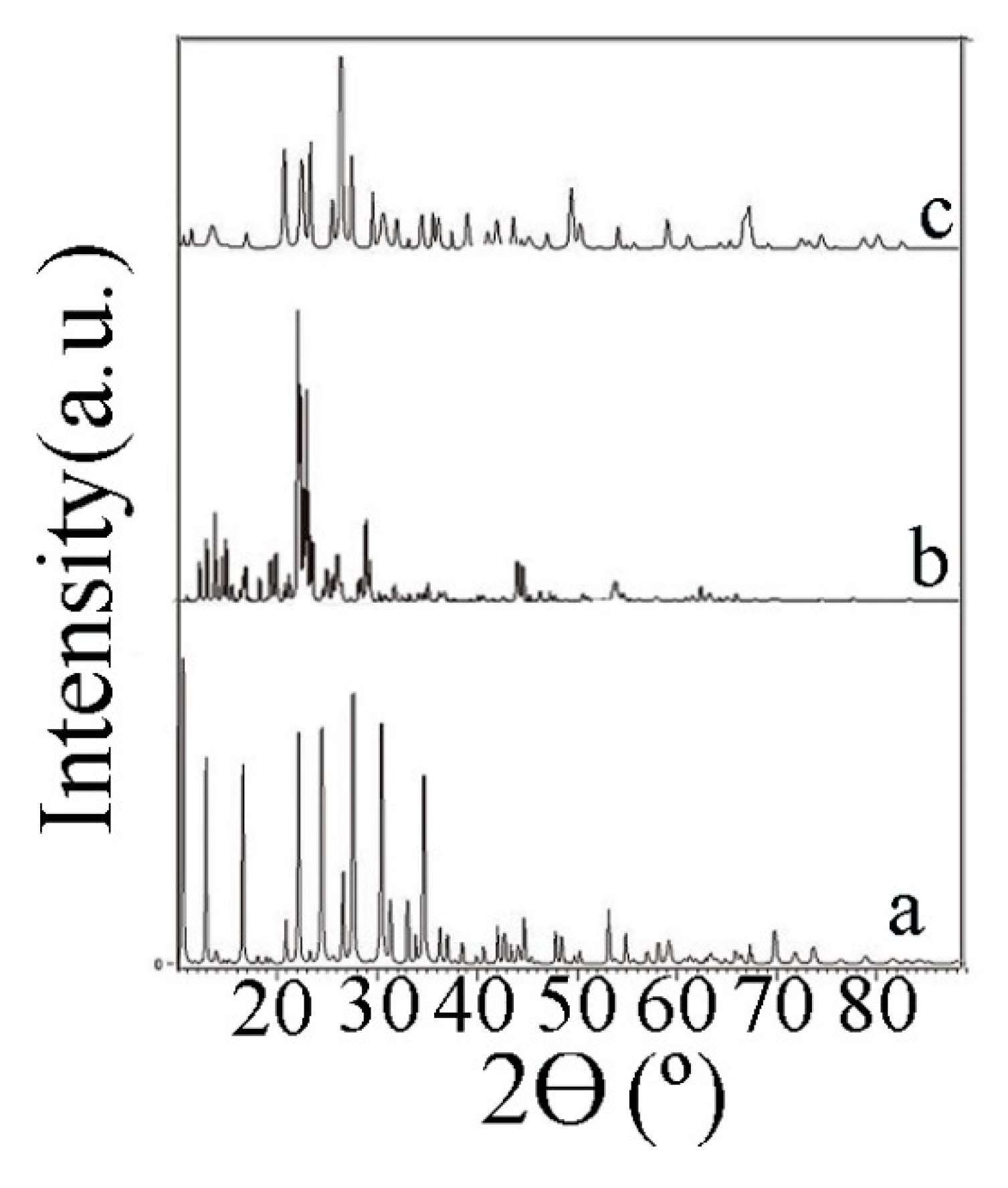

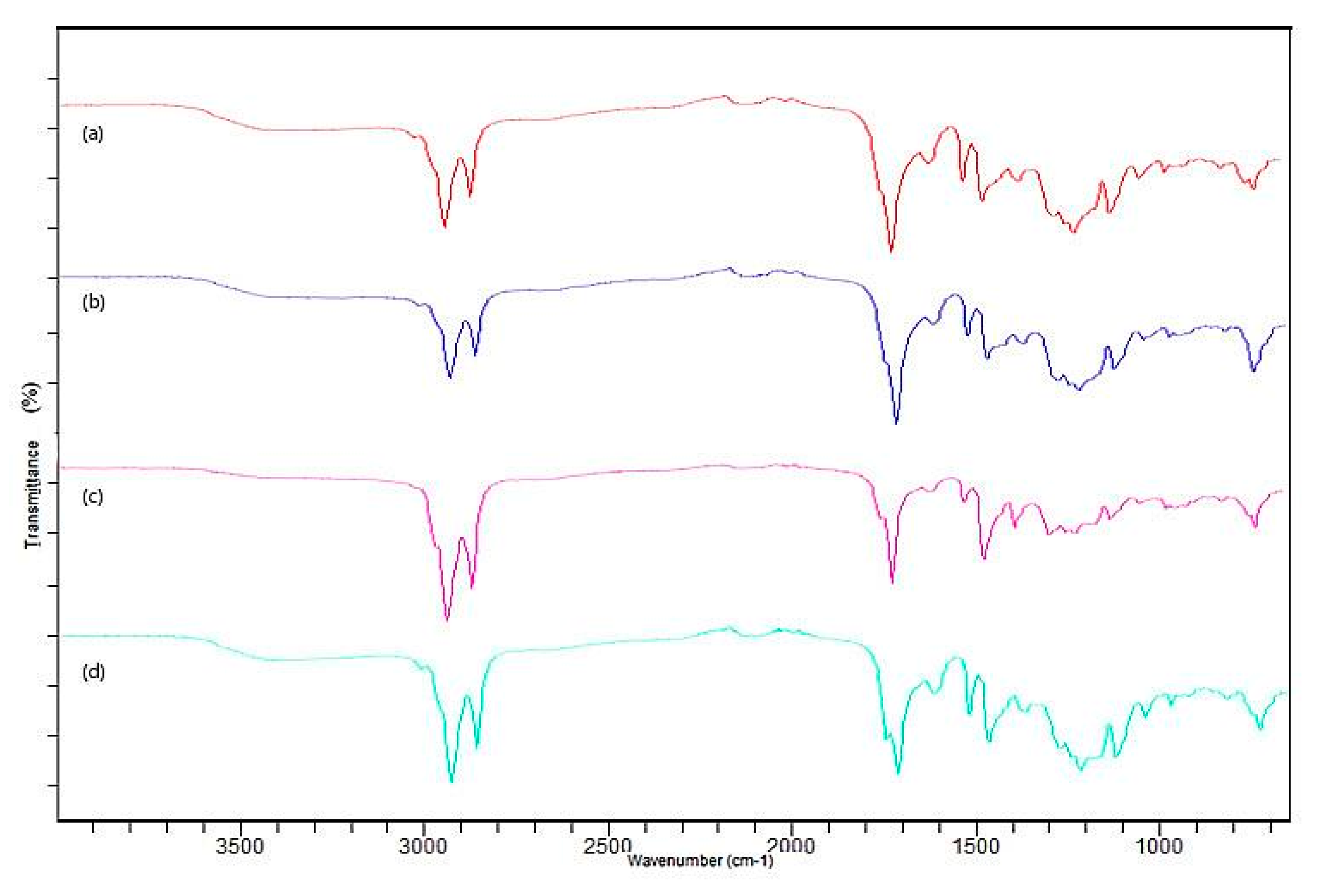

3.1. Characterization of the Biomass Sample and Catalysts

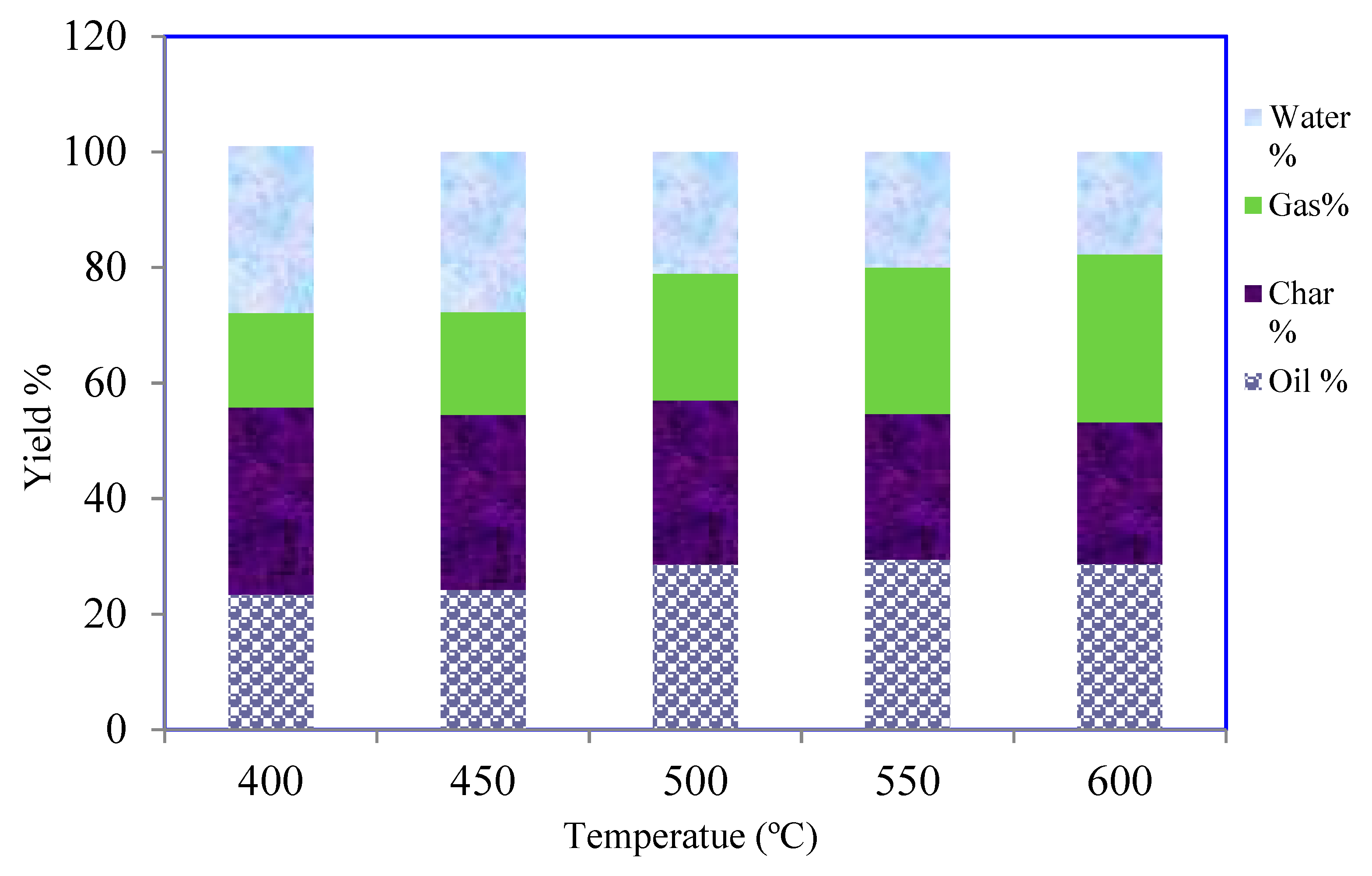

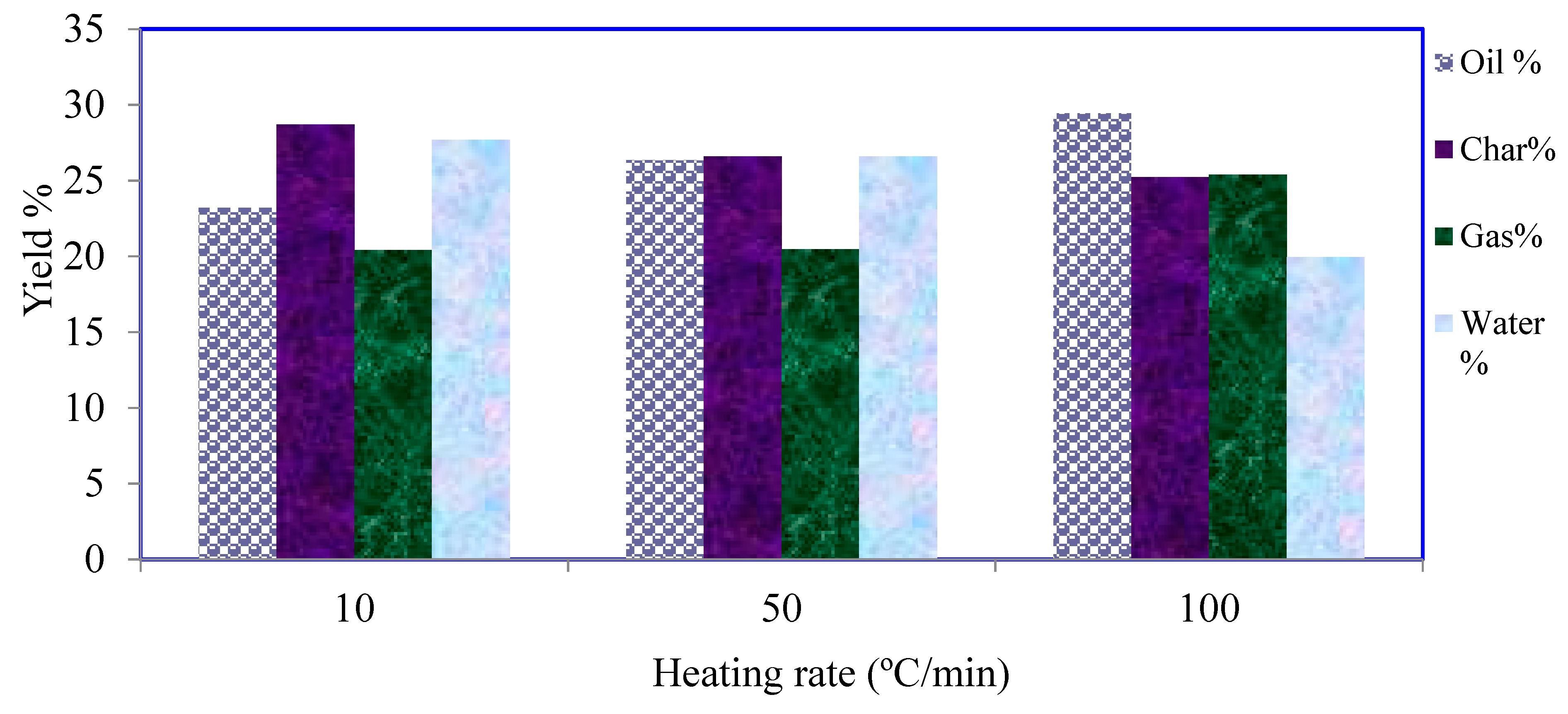

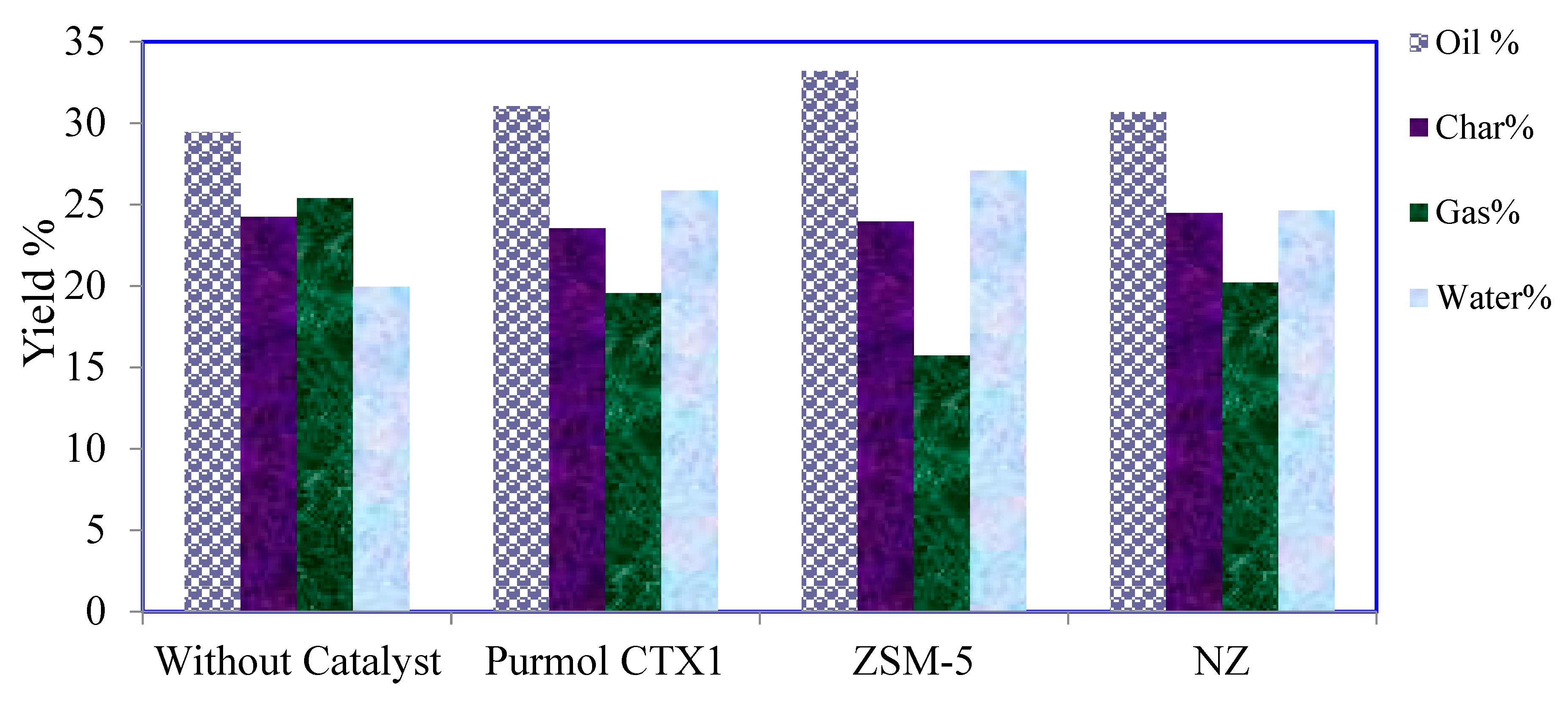

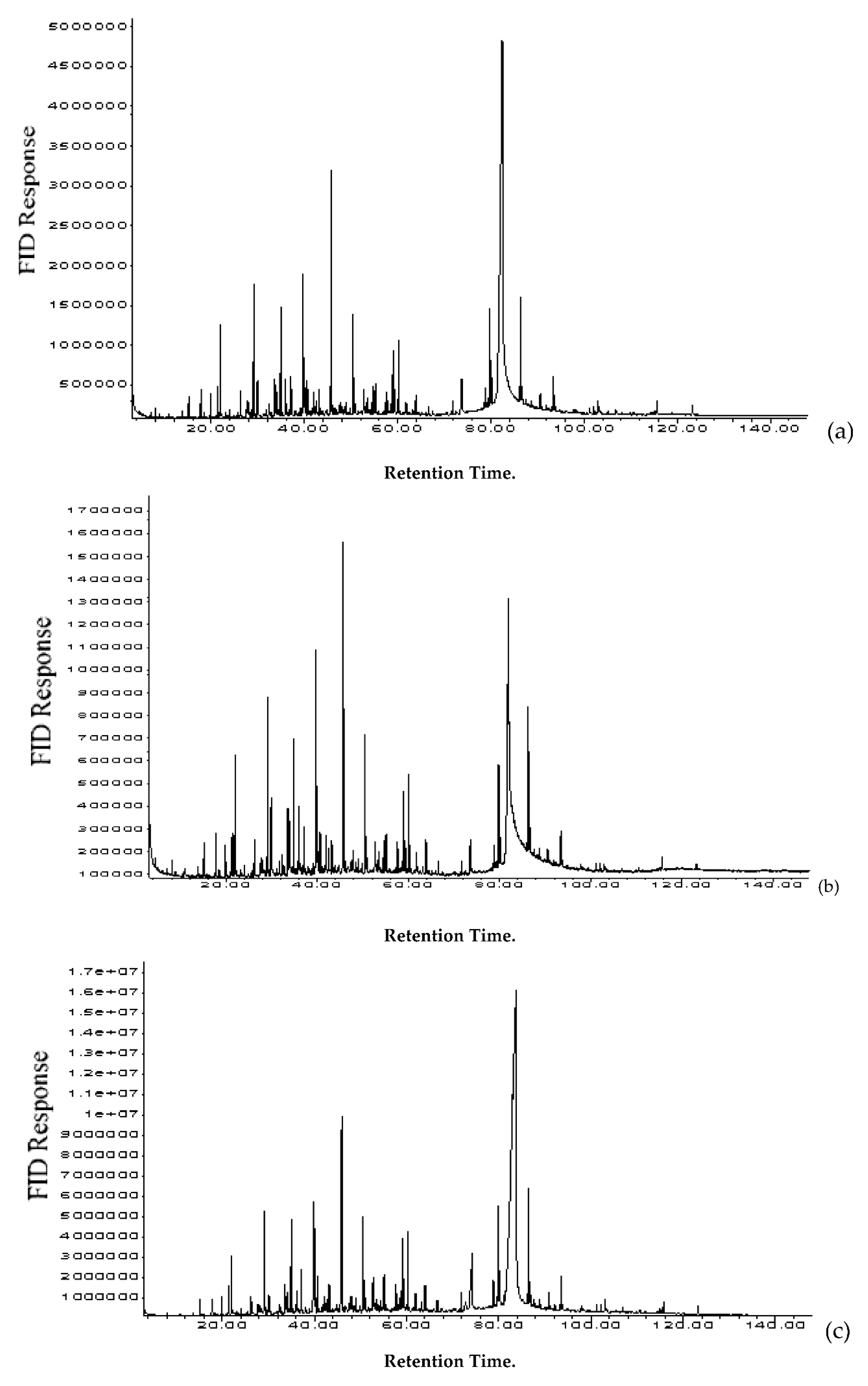

3.2. Pyrolysis Yields

4. Conclusions

References

- Kabir, G.; Hameed, B.H. Recent progress on catalytic pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass to high grade bio-oil and bio-chemicals. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 945–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich-Messina, L.I.; Bonelli, P.R.; Cukierman, A.L. In-situ catalytic pyrolysis of peanut shells using modified natural zeolite. Fuel Processing Technol. 2017, 159, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, P.R.; Ouedraogo, A.S.; Soloiu, V.; Quirino, R. Recent advances on catalysts for improving hydrocarbon compounds in bio-oil of biomass catalytic pyrolysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020, 121, 109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md. Maksudur, R.; Ronghou, L.; Junmeng, C. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass over zeolites for high quality bio-oil – A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 180, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dada, T.D.; Sheehan, M.; Murugavelh, S.; Antunes, E. A review on catalytic pyrolysis for high-quality bio-oil production from biomass. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023, 13, 2595–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, B.; Veses, A.; Callen, M.; Sharon, M.; Garcia, T.; Ramirez-Pérez, J. Porosity–acidity interplay in hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolites for pyrolysis oil valorization to aromatics. Chem.Sus.Chem. 2015, 8, 3283–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pütün, E.; Uzun, B.B.; Pütün, A.E. Fixed-bed catalytic pyrolysis of cotton-seed cake: Effects of pyrolysis temperature, natural zeolite content and sweeping gas flow rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadima, A. ; Muraza, O In situ fast pyrolysis of biomass with zeolite catalysts for bioaromatics/gasoline production: A review. Energy Convers Manag. 2015, 105, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, P.S.; Shafaghat, H.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Production of green aromatics and olefins by catalytic cracking of oxygenate compounds derived from biomass pyrolysis: A review. Appl Catal A Gen. 2014, 469, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarli, I.C.; Stefanidis, S.D.; Kalogiannis, K.G.; Lappas, A.A. Utilisation of poultry industry wastes for liquid biofuel production via thermal and catalytic fast pyrolysis. Waste Manag Res. 2019, 37, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mante, O.D.; Agblevor, F.A.; Oyama, S.T.; McClung, R. Catalytic pyrolysis with ZSM-5 based additive as co-catalyst to Y-zeolite in two reactor configurations. Fuel 2014, 117, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lei, H.; Ren, S.; Bu, Q.; Liang, J.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lee, G.S.J.; Chen, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Aromatics and phenols from catalytic pyrolysis of Douglas fir pellets in microwave with ZSM-5 as a catalyst. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2012, 98, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.R.; Uemura, Y.; Yusup, S.; Sugiura, Y.; Nishiyama, N. In situ catalytic fast pyrolysis of paddy husk pyrolysis vapors over MCM-22 and ITQ-2 zeolites. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2015, 114, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütün, E.; Uzun, B.B.; Pütün, A.E. Rapid pyrolysis of olive residue. 2. Effect of catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors in a two-stage fixed-bed reactor. Energ. Fuels 2009, 2248–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Website http://www.fao.org/home/en/.

- Angın, D. Utilization of activated carbon produced from fruit juice industry solid waste for the adsorption of Yellow 18 from aqueous solutions. Bioresource Technol. 2014, 168, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, P.; Priya-Susan, V.; Ravichandran, P.; Seshadri, S. Production and Characterization of Activated Carbon from Banana Empty Fruit Bunch and Delonix regia Fruit Pod. J. Sustain. Energy Environ. 2012, 3, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbay-Şahin, R.Z.; Ozbay, N. Perspective on catalytic biomass pyrolysis bio-oils: Essential role of synergistic effect of metal species co-substitution in perovskite type catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2021, 151, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, N.; Apaydın-Varol, E.; Uzun, B.B.; Pütün, A.E. Characterization of bio-oil obtained from fruit pulp pyrolysis. Energy 2008, 33, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, E.; Özbay, N.; Yargıç, A.Ş.; Şahin, R. Production and characterization of chars from cherry pulp via pyrolysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, E.; Özbay, N. Evaluation of Bio-Oils Produced From Pomegranate Pulp Catalytic Pyrolysis. Chapter 3.11. Exergetic Energetic Environ. Dimens. 2018, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, F.; Pütün, A.E.; Pütün, E. Fixed bed pyrolysis of Euphorbia rigida with different catalysts. Energy Convers. Manage. 2005, 46, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, N.; Yargıç, A.Ş.; Yarbay-Şahin, R.Z. Tailoring Cu/Al2O3 catalysts for the catalytic pyrolysis of tomato waste. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 91, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probstein, R.F.; Hicks, R.E. Synthetic Fuels; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1982; 284p. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, F.; Işıkdağ, A.M. Evaluation of the Role of the Pyrolysis Temperature in Straw Biomass Samples and Characterization of the Oils by GC/MS Energ. & Fuels 2008, 22, 1936–1943.

- Toro-Trochez, J.L.; De Haro Del Río, D.A.; Sandoval-Rangel, L.; Bustos-Martínez, D.; García-Mateos, F.J.; Ruiz-Rosas, R.; Rodríguez-Mirasol, J.; Cordero, T.; Carrilo- Pedraza, E.S. ; Catalytic fast pyrolysis of soybean hulls: Focus on the products. J. Anal.Appl. Pyrol. 2022, 163, 105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol-Apaydın, E.; Erülken, Y. A study on the porosity development for biomass based carbonaceous materials. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem.E. 2015, 54, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.B.; Sarıoğlu, N. Rapid and catalytic pyrolysis of corn stalks. Fuel Process Technol. 2009, 90, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saynik, P.B.; Moholkar, V. S. Investigations in influence of different pretreatments on A. donax pyrolysis: Trends in product yield, distribution & chemical composition. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2021, 158, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Jeon, J.K.; Lee, I.G.; Ryu, C.; Suh, D.J.; Park, Y.K. Catalytic conversion of particle board over microporous catalysts. Renew. Energ. 2013, 54, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, C. Inverse Gas Chromatographic Determination of the Surface Properties of ZSM-5 Zeolite. Nevsehir Journal of Science and Technology 2019, 8, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Encinar, J.E.; Gonzales, J.F.; Gonzales, J. Fixed-bed pyrolysis of Cynara cardunculus L. Product yields and compositions. Fuel Process. Technol. 2000, 68, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, F.; Işıkdağ, M.A. Influence of temperature and alumina catalyst on pyrolysis of corncob. Fuel 2009, 88, 1991–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.B.; Pütün, A.E.; Pütün, E. Composition of products obtained via fast pyrolysis of olive-oil residue: Effect of pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2007, 7, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, E.; Uzun, B.B.; Pütün, A.E.; Pütün, E. The effect of pyrolysis atmosphere on bio-oil yields and structure Int. J. Green Energy 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütün, E. Catalytic pyrolysis of biomass: Effects of pyrolysis temperature, sweeping gas flow rate and MgO catalyst. Energy 2010, 35, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.B.; Varol-Apaydın, E.; Ates¸, F.; Özbay, N.; Pütün, A.E. Synthetic fuel production from tea waste: Characterisation of bio-oil and bio-char. Fuel 2010, 89, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pareek, V.; Zhang, D. Biomass pyrolysis—A review of modelling, process parameters and catalytic studies. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2015, 50, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, F.; Tophanecioğlu, S.; Pütün, A.E. The Evaluation of Mesoporous Materials as Catalyst in Fast Pyrolysis of Wheat Straw. Int. J. Green Energy. 2015, 12, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisano, S.; Urbani, F.; Mondello, N.; Chiodo, V. Catalytic pyrolysis of Mediterranean sea plant for bio-oil production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2017, 42, 28082–28092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J.; Saidina- Amin, N. A review on operating parameters for optimum liquid oil yield in biomass pyrolysis. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2012, 16, 5101–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, A.A.; Kalogiannis, K.G.; Iliopoulou, E.F.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Stefanidis, S.D. Catalytic pyrolysis of biomass for transportation fuels. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Energy Environ 2012, 1, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soongprasit, K.; Sricharoenchaikul, V.; Atong, D. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of Millettia (Pongamia) pinnata waste using zeolite Y. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2017, 124, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Huang, H.; Xiao, G. Comparison of non-catalytic and catalytic fast pyrolysis of corncob in a fluidized bed reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaujia, P.K.; Sharma, Y.K.; Garg, M.O.; Tripathi, D.; Singh, R. Review of analytical strategies in the production and upgrading of bio-oils derived from lignocellulosic biomass. J.Ana. Appl. Pyrol. 2014, 105, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, K.; Kosa, M.; Williams, A.; Mayor, R.; Realff, M.; Muzzy, J.; Ragauskas, A. 31P-NMR analysis of bio-oils obtained from the pyrolysis of biomass. Biofuels 2010, 1, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.A.; Strahan, G.D.; Boateng, A.A. Characterization of various fast-pyrolysis bio-oils by NMR spectroscopy. Energ. Fuel 2009, 23, 2707–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarolo, N.S.; Silva, R.V.S.; Vanini, G.; Casilli, A.; Ximenes, V.L.; Mendes, F.L.; de Rezende Pinho, A.; Romao, W.; de Castro, E.V.R.; Kaiser, C.R.; et al. Characterization of thermal and catalytic pyrolysis bio-oils by high-resolution techniques: 1H NMR, GC × GC-TOFMS and FT-ICR MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2016, 117, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnisa, F.; Arami-Niya, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Sahu, J.N. Characterization of bio-oil and bio-char from pyrolysis of palm oil wastes. BioEnerg.Res. 2013, 6, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeih, K.L.; Baron, M.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J. Recent trends and developments in pyrolysis–gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr A. 2008, 1186, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütün, E.; Ateş, F.; Pütün, A.E. Catalytic pyrolysis of biomass in inert and steam atmospheres. Fuel 2008, 87, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattiya, A.; Titiloye, J.O.; Bridgwater, A.V. Fast pyrolysis of cassava rhizome in thepresence of catalysts. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2008, 81, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samolada, M.C.; Papafotica, A.; Vasalos, I.A. Catalyst evaluation for catalytic biomass pyrolysis. Energ Fuels 2000, 14, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Production of hydrocarbons by catalytic upgrading of a fast pyrolysis bio-oil: Part I: Conversion over various catalysts. Fuel Process Technol 1995, 45, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Production of hydrocarbons by catalytic upgrading of a fast pyrolysis bio-oil: Part II: Comparative catalyst performance and reaction pathways. Fuel Process Technol. 1995, 45, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| wt. % | wt. % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisturec | 8.87 | Ca | 43.50 |

| Ashb | 0.91 | Ha | 5.24 |

| Volatile matterb | 83.84 | Na | 0.73 |

| Fixed carbonb | 6.38 | Oa | 50.53 |

| Hemicellulosec | 44.58 | H/C | 1.45 |

| Ligninb | 31.97 | O/C | 0.87 |

| Oilc | 7.17 | ||

| Excractivesb | 18.30 | HHV(MJ/kg) | 13.16 |

| Plum seed | Max degradation temperature T1 (˚C) | Max degradation rate (%/min) | Max degradation temperature T2 (˚C) | Max degradation rate (%/min) | Total mass loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | 340 | -7.04 | 508 | -4.71 | 95.199 |

| Air | 345 | -10.29 | 495 | -7.15 | 97.994 |

| Component | NZ(%) | ZSM-5(%) | Purmol CTX-1(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Si | 35.82 | 88.59 | 20.86 |

| Al | 6.76 | 0.76 | 19.68 |

| K | 3.76 | - | 0.06 |

| Ca | 2.76 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| Fe | 0.95 | 1.01 | 0.03 |

| Na | 0.09 | 1.27 | 13.07 |

| Component | Without catalyst (%) |

ZSM-5 (%) |

natural Zeolite (%) |

Purmol CTX-1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (wt.%) | 59.32 | 74.75 | 79.76 | 74.78 |

| H (wt.%) | 7.52 | 10.89 | 11.29 | 11.02 |

| N (wt.%) | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.84 |

| O (wt.%) | 32.98 | 14.04 | 8.45 | 13.36 |

| H/C | 1.52 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.77 |

| O/C | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.079 | 0.13 |

| Empirical formula | CH1.3N0.0026O0.42 | CH1.65N0..0037O0.14 | CH1.42N0.0023O0.079 | CH1.32N0..096O0.13 |

| Higher heating value ( MJ/kg) | 24.97 | 38.47 | 41.75 | 38.79 |

| Bio-oil | Pentane Non-solubles (%) | Pentane Solubles (%) | Aliphatics (%) | Aromatics(%) | Polars(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without catalyst | 76.45 | 23.55 | 15.19 | 27.77 | 57.04 |

| Natural zeolite | 56.12 | 43.88 | 24.28 | 34.42 | 41.30 |

| Purmol CTX-1 | 59.27 | 40.73 | 18.00 | 33.06 | 48.94 |

| ZSM-5 | 55.69 | 44.31 | 21.21 | 45.45 | 33.34 |

| Hydrogen type | Hydrogen in Bio-oil (Percentage of Total) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical shift (ppm) | Without catalyst | ZSM-5 | Purmol CTX-1 | NZ | |

| CH3 γ or furter from aromatic ring and paraffinic CH3 | 1.0-0.5 | 20.10 | 16.40 | 11.90 | 15.97 |

| CH3; CH2 and CH β to araomatic ring | 1.5-1.0 | 18.55 | 20.10 | 19.76 | 19.63 |

| CH2 and CH attached to naphthenes | 2.0-1.5 | 10.15 | 11.80 | 10.20 | 5.33 |

| CH3; CH2 and CH α to araomatic or aceytlenic | 3.0-2.0 | 19.20 | 24.30 | 25.83 | 12.99 |

| Total aliphatics | 3.0-0.5 | 68 | 72.60 | 67.69 | 53.67 |

| Hydrokyl. ring-joining methylene. methine or methoxy | 4.0-3.0 | 7.80 | 6.60 | 5.53 | 6.34 |

| Phenols. non-conjugated olefins | 6.0-4.0 | 10.90 | 6.30 | 9.92 | 4.76 |

| Aromatics. conjugated olefins | 9.0-6.0 | 13.20 | 14.50 | 16.86 | 35.23 |

| Compound | Area % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without catalyst | NZ | Purmol CTX-1 | ZSM-5 | |

| 1-Tetradecene | 0.97 | - | 0.24 | |

| Tetradecane | - | 0.10 | - | 0.08 |

| 1,13-Tetradecadiene | 1.20 | - | 0.16 | |

| trans-7-pentadecene | - | - | - | 0.30 |

| 1-Pentadecene | - | 0.71 | 1.10 | 0.36 |

| Dodecane | - | 1.49 | 2.41 | 1.04 |

| n-Nonylcyclohexane | 0.79 | 1.08 | 0.64 | |

| Bicycloheptane, 7-pentyl | - | - | - | 0.40 |

| Cyclododecene | - | 5.34 | 5.19 | 1.52 |

| 3-Hexadecene | - | 1.11 | 1.40 | 0.69 |

| 8-Hexadecene | - | - | - | 1.04 |

| Hexadecane | - | 1.41 | 1.43 | 1.45 |

| methylcyclododecane | - | 1.02 | - | 0.72 |

| Cycloundecene, 1-methy | - | - | - | 0.30 |

| Cyclohexane, 2-propenyl- | - | - | 0.74 | 0.38 |

| Cyclohexane, | - | 0.30 | - | 1.03 |

| 6,8-Heptadecadiene | - | 1.25 | ||

| 8-Heptadecene | 0.96 | 6.89 | 10.69 | 3.01 |

| Heptadecane | 1.91 | 2.25 | 2.21 | 0.99 |

| 1-Heptadecene | - | - | - | 0.39 |

| 6,9-Heptadecadiene | - | - | 1.03 | 2.46 |

| 1,6-Tridecadiene | - | - | - | 0.71 |

| 1-8-10-Tridecatriene | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 1,9-Tetradecadiene | 0.60 | 0.84 | 1.10 | 0.69 |

| 3-Octadecene | - | - | 1.10 | 0.48 |

| 9-Octadecene | - | - | 0.66 | |

| 1-Octadecene | - | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.39 |

| Octadecane | 0.76 | - | 0.41 | 0.24 |

| 1-Hexadecyne | - | 0.39 | ||

| Cyclotetradecane | - | 0.58 | 0.70 | |

| 1-Nonadecene | 3.03 | 0.96 | 1.33 | 0.92 |

| Nonadecane | 0.85 | 1.3 | 0.48 | 0.29 |

| 1-Hexadecene | - | 0.25 | 2.04 | 0.34 |

| Eicosane | 2.23 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.32 |

| 1-Docosene | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.67 | |

| Docosane | 0.42 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 1.28 |

| 11-Tricosene | - | 0.76 | ||

| Tricosane | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.65 | |

| 17-Pentatriacontene | 0.08 | 0.27 | ||

| Tetracosane | 2.28 | 1.04 | 1.56 | 0.48 |

| Pentacosane | 1.26 | 1.04 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| 13-Methyl -14-nonacosene | - | - | - | 0.20 |

| Spiro[4.5]decane | - | - | - | 0.93 |

| Heneicosane | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.48 |

| Octacosane | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||

| Nonacosane | 2.04 | 1.42 | 0.57 | |

| Heptacosane | 1.06 | 0.60 | 0.16 | |

| Heptane, 2,4-dimethyl- | 0.05 | - | ||

| Propylidencyclohexane | 0.52 | 0.59 | - | |

| cis,cis-1,6-Dimethylspiro[4.5]decane | 0.31 | - | - | |

| Heptadec-8-ene | 5.50 | 4.55 | - | - |

| Cyclopropane, 1-methyl-2-pentyl | 0.92 | 1.27 | - | - |

| 9-Octadecyne | - | 1.46 | - | - |

| 3-Methyl- 4,6-hexadecadiene | - | 0.35 | - | - |

| 2,6,6,10-Tetramethyl-undecane | - | 0.86 | - | - |

| 9-Tricosene | - | 0.48 | 0.24 | - |

| Hexacosane | - | 0.86 | - | - |

| n-Pentacos-3-ene | - | 0.65 | - | - |

| 3,11-dımethyl-nonacosane | - | 0.15 | - | - |

| Octane | - | - | 0.05 | - |

| Cyclohexene, 1-methyl | - | - | 0.03 | - |

| Hexane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl- | - | - | 0.06 | - |

| 2-Tetradecene | - | - | 0.60 | - |

| Cyclopentane, nonyl- | - | - | 0.52 | - |

| 7-Methyl-1,6-octadiene | - | - | 0.25 | - |

| 5-Undecyne | - | - | 0.18 | - |

| Bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane, 7-butyl | - | - | 0.14 | - |

| 1-hexene | - | - | 0.70 | - |

| 3-Heptadecene, | - | - | 1.04 | - |

| 1-Heptene, 2-isohexyl-6-methyl | - | - | 1.16 | - |

| bıcyclo[3.1.1]heptane, 2,6,6-trıme thyl | - | - | 1.16 | - |

| Cyclohexadecane | - | - | 0.58 | - |

| 1-Hexacosene | - | - | 0.06 | - |

| Tricosane | - | - | 0.05 | - |

| Heneicosane, 3-methyl- | - | - | 0.07 | - |

| Cyclopentane, 1,2-dibutyl | 0.29 | - | - | - |

| 1-Pentadecyne | 0.45 | - | - | - |

| 9-Tricosene, (Z) | 0.73 | - | - | - |

| 10-Heneicosene | 0.44 | - | - | - |

| Cyclotetracosane | 0.80 | - | - | - |

| 11-Hexacosyne | 0.22 | - | - | - |

| 13-Hexacosyne | 2.17 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).