1. Introduction

Onchocerciasis is one of the neglected tropical diseases caused by the parasite Onchocerca Volvulus, a filarial nematode [2] . The disease is transmitted from one person to another by repeated bites of black flies. The disease is endemic in Sub-saharan Africa. Many researchers have worked on many ways to reduce the spread of the disease. For instance, Remme et al. [11] used skin snip survey in West Africa to investigate the impact of controlling black flies by larviciding. Plaisier et al. [10] used micro simulation model to determine the period required for combining annual ivermectin treatment and vector control in the onchocerciasis Control Programme in West Africa. Alley et al. [1] used a computer simulation model to study prevention of onchocerciasis by using macrofilaricide which kills the adult worms. Asha Hassan & Nyimvua Shaban [3] investigated the effects of four control strategies on the spread of the disease.

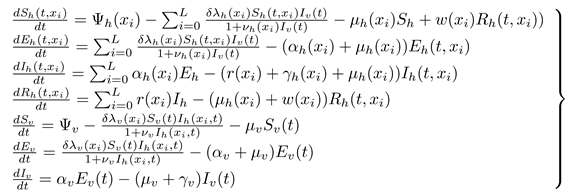

In this paper, we consider onchocerciasis transmission dynamics with nonlinear incidence functions. The human population is sub-divided into four compartments and the vector population is sub-divided into three compartments. We show local asymptotic behaviour in disease-free and endemic equilibria and also the bifurcation analysis examined. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the description of the model and theorems on positivity of solutions are given in section 2 while section 3 is devoted to the proof local stability theorems and the bifurcation analysis of the model is done in section 4.

2. Model Description

Two interacting populations are considered; the humans and the black-flies populations. The human population is partitioned into four compartments: the susceptible human compartment;

,, the exposed compartment;

, the infectious human compartment;

and the recovered human compartment;

. The black-fly population is partitioned into three compartments: susceptible vector;

, the exposed vector compartment;

and the infective vector compartment. The total human and vector populations at any given time, t, are respectively given by;

and

. We assume that the transmission of onchocerciaisis in susceptible hosts is only through contact with infectious vector. We also assume that susceptible vector becomes infectious as a result of contact with infectious hosts during blood meal. The population under study is assumed to be large enough to be modelled deterministically. The following system of non-linear ordinary differential equations, with non-negative initial conditions, describes the dynamics of onchocerciaisis epidemics.

subject to the following initial conditions:

| Symbols |

Definitionss |

|

Number of susceptible humans at time t and discrete age

|

|

Number of exposed humans at time t and discrete age

|

|

Number of infectious humans at time t and discrete age

|

|

Number of recovered humans at time t and discrete age

|

|

Number of susceptible black-flies at time t

|

|

Number of exposed black-flies at time t

|

|

Number of infectious black-flies at time t

|

|

Recruitment term of the susceptible humans at discrete age

|

|

Recruitment term of the susceptible vectors |

|

Biting rate of the vector |

|

Probability that a bite by an infectious vector results

in transmission of disease to human at discrete age

|

|

Probability that a bite results in transmission

of parasite to a susceptible vector |

|

Per capita death rate of humans at discrete age

|

|

Per capita death rate of vector |

|

Disease-induced death rate of humans at discrete age

|

|

Disease-induced death rate of vectors |

|

Per capita rate of progression of humans from the

exposed state to the infectious state at discrete age

|

|

Per capita rate of progression of vectors from the

exposed state to the infectious state |

|

Per capita recovery rate for humans from the infectious state

to the recovered state due to treatment at discrete age

|

|

Per capita transition rate of recovered humans

to the susceptible state at discrete age

|

|

Humans disease-inhibiting factor at discrete age

|

|

Vectors disease-inhibiting factor |

Model assumptions

The formulation of the compartmental model is based on the following assumptions:

- 1.

That all humans are born susceptible. That is, humans are liable to contract the disease.

- 2.

That the susceptible humans, when infected, becomes exposed humans who are not yet infectious.

- 3.

That the exposed humans progress to become infectious only.

- 4.

That the infectious humans may either die naturally or as a result of the disease, and if not, they become recovered humans due to treatment.

- 5.

That the recovered humans become susceptible again.

- 6.

All black-flies are born susceptible.

- 7.

That the susceptible black-flies, when infected, becomes exposed black-flies who are not yet infectious.

- 8.

That the exposed black-flies progress to become infectious only.

- 9.

That the infectious black-flies remain infectious for life. That is, there is no recovered class for black-fly population.

2.1. Existence and Positivity of Solutions

In this section, we analyse the general properties of the system (2.1) with positive initial conditions. It describes the population dynamics both in human and black-fly populations. The system is biologically relevant in the set given by

Here, the following results are provided which guarantee that the model governed by system (2.1) is mathematically well-posed in a feasible region

defined by:

Theorem 1: There exists a domain in which the solution set is contained and bounded.

Proof If the total human population size is given by

, and the total size of black-fly population is

. From model (2.1), we have that

and

It follows from (2.3) and (2.4) that

and

Taking the as gives and . This shows that all solutions of the humans population only are confined in the solution set and all solutions of the black-fly population are confined in . It also suffices to say that is positively invariant as whenever and if , Therefore the solution set for the model (2.1) exists and is given by □

It remains to show that the solutions of system (2.1) are nonnegative in for any time since the variables represent human and black-fly populations.

Theorem 2: The solutions, , , , , , , , of model (2.1) with nonnegative initial conditions in , remain nonnegative in for all .

Proof: Given that the initial conditions,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, are non-negative and from (2.1),

so that

Integrating (2.5), we have

which implies that for all

and for all

, we have

Hence,

for any arbitrary

. Also, we have

so that

Integrating (2.6), we have for all

and for all

, that

Hence,

for any arbitrary

Also we have

so that

Hence,

for any arbitrary

. Also from (2.1), we have

and we have

Integrating (2.8), we have, for all

and

, that

Hence,

for any arbitrary

. In a similar manner, we have

so that

Integrating (2.9), we have

Also we have

which on integration gives

And finally, we have

so that

This completes the proof □

3. Existence and stability of the equilibrium points

3.1. Disease-free equilibrium

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) points are steady state solutions that depict the absence of infection in both the human host and black-fly vector populations, i.e, onchocerciasis does not exist in the population. Thus, the disease-free equilibrium point,

, for the model (2.1) implies that

,

,

,

and putting these into (2.1), we have

and

. Consequently we obtain

as

A key notion in the analysis of infectious disease models is the basic reproduction number

, an epidemiological threshold that determines whether disease dies out or persists in the population.The basic reproduction number

of the system (2.1) is computed using the next generation matrix method and is given by

where

and

. The basic reproduction number

, determines whether onchocerciasis dies out or persists in the population. Therefore,

describes the number of humans that one infectious black-fly infects over its expected infectious period in a completely susceptible humans population, while

is the number of blac-flies infected by one infectious human during the period of infectiousness in a completely susceptible black-fly population.

3.2. Local Stability of the Disease-free Equilibrium Point

Using the basic reproduction number obtained for the model (2.1), we analyse the stability of the equilibrium point in the following result.

Theorem 3:The disease-free equilibrium point, , is locally asymptotically stable if , and unstable if .

Proof: The Jacobian matrix of the system (2.1) evaluated at the disease-free equilibrium point

, is obtained as

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

We need to show that all the eigenvalues of

are negative. As the first and fifth columns form the two negative eigenvalues,

and

, the other five eigenvalues can be obtained from the sub-matrix,

, formed by excluding the first and fifth rows and columns of

. Hence

In the same way, the third column of

contains only the diagonal term which forms a negative eigenvalue,

. The remaining four eigenvalues are obtained from the sub-matrix

given by

Thus, the eigenvalues of the matrix

are the roots of the characteristic equation of the form

If we let

,

,

, and

, then (3.2) becomes

where

Expressing

in terms of reproduction number

, we have

We can see from (3.4) that

,

,

,

, since all

are positive. Moreover, if

, it follows from (3.5) that

. Thus, using the Routh-Hurwitz criterion, we have

Similarly we have

and

where

Therefore, all the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix have negative real parts when and the disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable. However, when , we see that and there is one eigenvalue with positive real part and therefore the disease-free equilibrium point is unstable □

3.3. Endemic Equilibrium Point

We shall show that the formulated model (2.1) has an endemic equilibrium point, . The endemic equilibrium point is a positive steady state solution where the disease persists in the population.

Theorem 4: The model (2.1) has a unique endemic equilibrium whenever .

Proof: Let

be a nontrivial equilibrium of the model (2.1). That is, all components of

are positive. Then the onchocerciasis model (2.1) at steady-state becomes

From the last three equations, we have

and

Substituting (3.14) and (3.15) into (3.13) yields

From (3.8) and (3.9), we have

and

If we put (3.16) and (3,17) in (3.7) in terms of

, we have

Finally, using (3.16), (3.18) and (3.19) in (3.7), we have

where

If in (3.20), then . From this, one sees that model (2.1) has no positive solution when . However, with , a unique endemic equilibrium exists when . This completes the proof. □

Remark 1:It is important to have a remark that positive solution exists for the model (2.1) in a case where and . This implies that the disease-free equilibrium co-exists with the endemic equilibrium state when is slightly less than unity resulting into a phenomenon of subcritical (backward) bifurcation.

4. Bifurcation Analysis

The mathematical examination of changes in the qualitative behaviour of a dynamical system as its parameter passes through a critical value called a bifurcation point is referred to as bifurcation analysis.

Theorem 5(Castillo-Chavez and Song (2004):

Consider the following general system of ordinary differential equations with a parameter

:

where 0 is an equilibrium point of the system (that is,

for all

) and we have the following assumptions:

- 1.

is the linearization matrix of the system (4.1) around the equilibrium 0 with evaluated at 0. Zero is a simple eigenvalue of A and other eigenvalues of A have negative real parts;

- 2.

Matrix A has a nonnegative right eigenvector and a left eigenvector corresponding to the zero eigenvalue.

Let

be the

component of

f and

The local dynamics of the system around 0 is totally determined by the signs of m and n.

- (i)

, . When with , 0 is locally asymptotically stable and there exists a positive unstable equilibrium; when , 0 is unstable and there exists a negative, locally asymptotically stable equilibrium;

- (ii)

, . When with , 0 is unstable; when 1, 0 is locally asymptotically stable, and there exists a positive unstable equilibrium;

- (iii)

, . When with , 0 is unstable, and there exists a locally asymptotically stable negative equilibrium; when , 0 is stable, and a positive unstable equilibrium appears;

- (iv)

, . When changes from negative to positive, 0 changes its stability from stable to unstable. Correspondingly a negative unstable equilibrium becomes positive and locally asymptotically stable. In particular, if and , then there exists a backward bifurcation.

To demonstrate the possibility of the co-existence of the equilibria of model (2.1) at

but near

, the Center Manifold Theory described by Castillo-Chavez and Song (2004). Let the onchocerciasis model (2.1) be written in the vector form

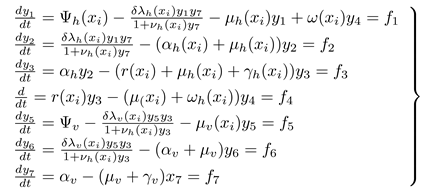

where

and

so that so that

;

;

;

;

;

; and

: Then model (2.1) becomes

Let

be a bifurcation parameter such that

when

. Then

The linearization matrix

of the model (2.1), evaluated at the disease-free equilibrium

and the bifurcation parameter

, is given

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

The eigenvalues of

can be obtained by solving the characteristic equation

where

is a polynomial of degree four. Consequently,

has a zero eigenvalue which is simple and other eigenvalues are real and negative. Let the right eigenvector corresponding to this zero eigenvalue be denoted by

so that

. Then we have

From (4.2), the components of the right eigenvector

are given by

and

Further,

has a left eigenvector,

, associated with the zero eigenvalue, which can be obtained from

as follows:

We see from (4.1) that all the second-order partial derivatives at

and

are zero except the following:

If we let the bifurcation coefficients m and n of Theorem be

and

respectively, it then follows from the above partial derivatives that

Substituting the appropriate right eigenvector (4.3), the left eigenvector (4.6) and the second-order partial derivatives obtained earlier into

yields

The signs of and are important in determining the direction of bifurcation at (Castillo-Chavez and Song, 2004). One sees that and and by item(iv) of Theorem 5, the model (2.1) is capable of exhibiting a backward bifurcation phenomenon. Thus, we have the following result:

Theorem 6: The onchocerciasis model given by (2.1) undergoes a phenomenon of backward bifurcation at and .

References

- W. S. Alley, B.A.B. Boatin, N.J.D.N. Nagelkerke, Macrofilaricides and onchocerciasis control, mathematical modelling of the prospects for elimination. BMC Public Health 1(1) (2001), p. 12.

- U. Amazigo, M. Noma, J. Bump, B. Bentin, B. Liese, L. Yameogo, H. Zouré, and A. Seketeli, Onchocerciasis Disease and Mortality in Sub Saharan Africa, Chapter 15, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2006.

- Asha Hassan & Nyimvua Shaban (2020) Onchocerciasis dynamics: modelling the effects of treatment, education and vector control, Journal of Biological Dynamics, 14:1, 245-268. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Chavez, C. and Song, B. 2004. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 1.2: 361-404.

- Eric M Poolman and Alison P Galvani. Modeling targeted ivermectin treatment for controlling river blindness. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 75(5):921–927, 2006.

- Jimmy P Mopecha and Horst R Thieme. Competitive Dynamics in a Model for Onchocerciasis with Cross-Immunity. Canadian Applied Mathematics Quarterly, 11(4):339–376, 2003.

- María-Gloria Basáñez and Michel Boussinesq. Population biology of human onchocerciasis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 354(1384):809–826, 1999.

- María-Gloria Basáñez and Jorge Ricárdez-Esquinca. Models for the population biology and control of human onchocerciasis. Trends in Parasitology, 17(9):430–438, 2001.

- Murray, J. D. 2002. Mathematical biology I., an introduction. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin.

- A.P. Plaisier, E.S. Alley, G.J. van Oortmarssen, B.A. Boatin, and J.D.F Habbema, Required duration of combined annual ivermectin treatment and vector control program in west africa, Bull. World Health Organ. 75(3) (1997), pp. 237.

- J. Remme, G. De Sole, and G.J. van Oortmarssen, The predicted and observed decline in onchocerciasis infection during 14 years of successful control of black flies in West Africa, Bull. World Health Organ.68(3) (1990), pp. 331–339.

- Shaib Ismail Omade, Adeyemi Tajudeen Omotunde, and Akinyemi Seye Gbenga. Mathematical Modeling of River Blindness Disease with Demography Using Euler Method. Mathematical Theory and Modeling, 5(5):75–85, 2015.

- World Health Organization, African programme for onchocerciasis control: Meeting of national onchocerciasis task forces, September 2012, Weekly Epidemiol. Record 87(49–50) (2012), pp. 494–502.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).