Submitted:

05 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

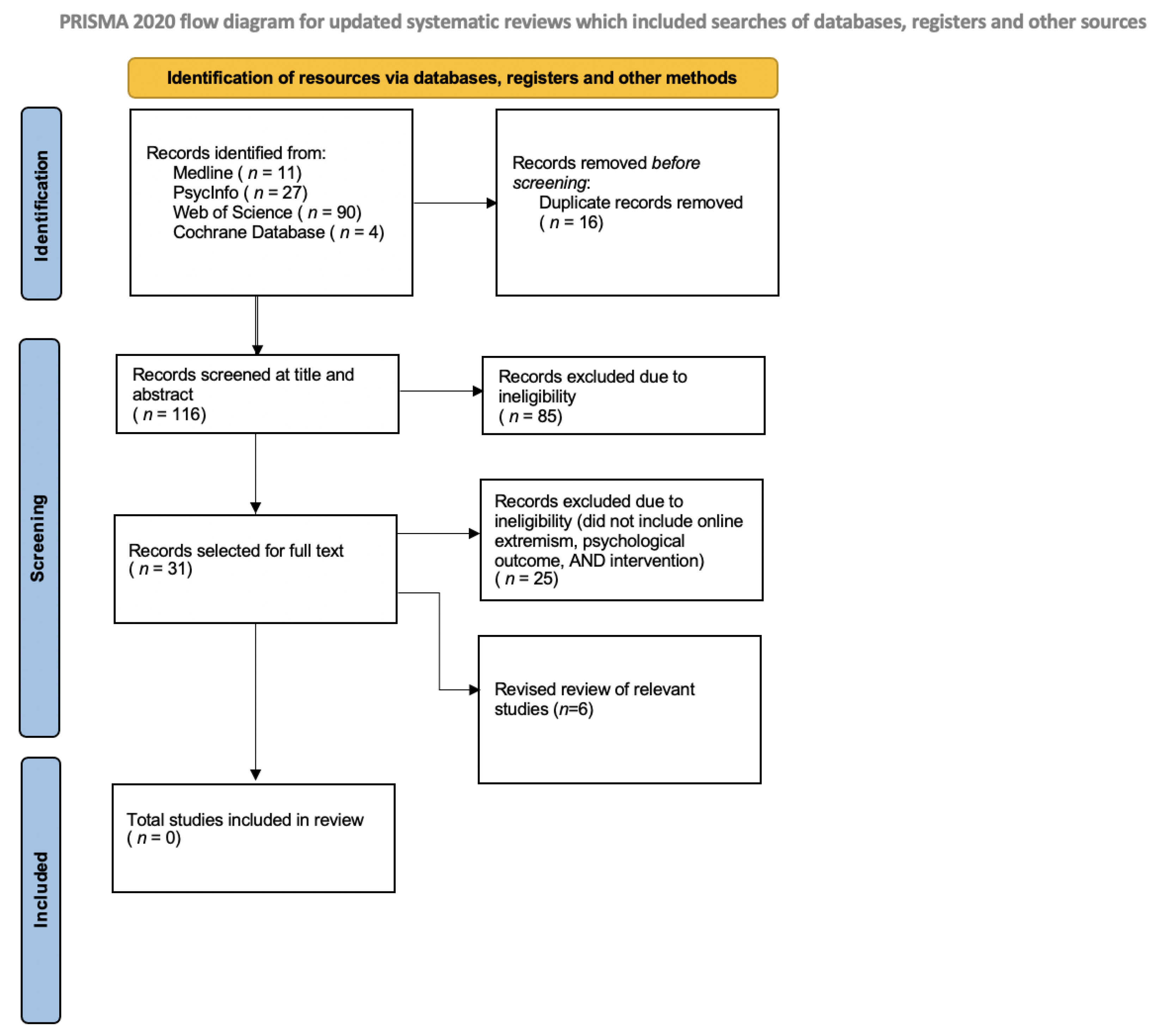

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome (PICO)

3. Results

3.1. Data Extraction and Analysis

3.2. Range of online content

3.3. Who accesses online content

3.4. Online radicalisation and correlates

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential biases and errors in the review process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The DRIVE project, Determining multi-levelled causes and testing intervention designs to reduce radicalisation, extremism, and political violence in northwestern Europe through social inclusion, grant agreement No. 959200. It expresses exclusively the authors' views, not necessarily those of all the DRIVE project Consortium members, and neither the European Commission nor the Research Executive Agency is responsible for any of the information it contains. |

References

- Gill, P.; Clemmow, C.; Hetzel, F.; Rottweiler, B.; Salman, N.; Van Der Vegt, I.; Corner, E. Systematic review of mental health problems and violent extremism. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 2021, 32, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pathé, M. T.; Haworth, D. J.; Goodwin, T. A.; Holman, A. G.; Amos, S. J.; Winterbourne, P.; Day, L. Establishing a joint agency response to the threat of lone-actor grievance-fuelled violence. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 2018, 29, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Augestad Knudsen, R. Measuring radicalisation: Risk assessment conceptualisations and practice in England and Wales. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 2020, 12, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K. Flash, the emperor and policies without evidence: counter-terrorism measures destined for failure and societally divisive. BJPsych bulletin, 2016, 40, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, D. Mandating doctors to attend counter-terrorism workshops is medically unethical. BJPsych Bulletin, 2016, 40, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurlow, J.; Wilson, S.; James, D.V. Protesting loudly about Prevent is popular but is it informed and sensible? BJPsych Bulletin 2016, 40, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, D. Family counselling, de-radicalization and counter-terrorism: The Danish and German programs in context. In Countering violent extremism: Developing an evidence-base for policy and practice; 2015; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- NIHR Conceptual framework for Public Mental Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.publicmentalhealth.co.uk (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- NHS Guidance for mental health services in exercising duties to safeguard people from the risk of radicalisation. 2017. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/prevent-mental-health-guidance.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Bello, W.F. Counterrevolution: The global rise of the far right. Fernwood Publishing. 2019.

- Moskalenko, S.; González JF, G.; Kates, N.; Morton, J. Incel ideology, radicalization and mental health: A survey study. The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare, 2022, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.; Clancy, B.; Furl, K. Far-Right Online Radicalization: A Review of the Literature. The Bulletin of Technology & Public Life 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nilan, P. Young people and the far right. Springer Nature. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, V. Down the TikTok Rabbit Hole: Testing the TikTok Algorithm’s Contribution to Right Wing Extremist Radicalization. Doctoral dissertation, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, J.; Hanna, M. J. User data privacy: Facebook, Cambridge Analytica, and privacy protection. Computer, 2018, 51, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, M.; Bohlmeijer, E. T.; Smit, F.; Westerhof, G. J. Mental health promotion as a new goal in public mental health care: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention enhancing psychological flexibility. American journal of public health 2010, 100, 2372–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd-McMillan, E.; DeMarinis, V. Learning Passport: Curriculum Framework. IC-ADAPT SEL high level programme design 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Systematic reviews, 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Research methodes and reporting. Bmj, 2009, 8, 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.; Ranganathan, P. Study designs: Part 4–interventional studies. Perspectives in clinical research, 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Demner-Fushman, D. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. In AMIA annual symposium proceedings; American Medical Informatics Association, 2006; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, J.B.; Rieger, D.; Rutkowski, O.; Ernst, J. Counter-messages as prevention or promotion of extremism?! The potential role of YouTube: recommendation algorithms. Journal of communication, 2018, 68, 780–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusnalasari, Z.D.; Algristian, H.; Alfath, T.P.; Arumsari, A.D.; Inayati, I. Students vulnerability and literacy analysis terrorism ideology prevention. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing, 2018; Volume 1028, p. 012089. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzar, D.; Laurent, G. The importance of interdisciplinarity to deal with the complexity of the radicalization of a young person. Annales Medico-Psychologiques 2019, 177, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.; Brickman, S.; Goldberg, Z.; Pat-Horenczyk, R. Preventing future terrorism: Intervening on youth radicalization. An International Perspective on Disasters and Children's Mental Health 2019, 391–418. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M.C. The wicked interplay of hate rhetoric, politics and the internet: what can health promotion do to counter right-wing extremism? Health Promotion International, 2020, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.B.; Caspari, C.; Wulf, T.; Bloch, C.; Rieger, D. Two sides of the same coin? The persuasiveness of one-sided vs. two-sided narratives in the context of radicalization prevention. SCM Studies in Communication and Media, 2021, 10, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Discrimination and health inequities. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 2014, 44, 643–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, & World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report; World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The spirit level. Why equality is better for everyone; Penguin: London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.E. Threat of Islamic radicalization to the homeland. Testimony before the US Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs; United States Senate: Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. 59th Session, A/59/565. 2004. Available online: http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/instree/report.pdf.

- Braddock, K.; Dillard, J.P. Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Communication Monographs, 2016, 83, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication & Society, 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé, E.; Jain, P.; Chung, A.H. Reinforcement or reactance? Examining the effect of an explicit persuasive appeal following an entertainment-education narrative. Journal of Communication, 2013, 62, 1010–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication & Society, 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. C.; Brock, T. C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2000, 79, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Meta-analysis comparing the persuasiveness of one-sided and two-sided messages. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 1991, 55, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Lumsdaine, A.A.; Sheffield, F.D. Experiments on mass communication. In Studies in social psychology in World War II; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1948; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A.L.; Piff, P.K. Finding uncommon ground: Extremist online forum engagement predicts integrative complexity. PLoSONE 2021, 16, e0245651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.; Whittaker, J. Playing for Hate? Extremism, terrorism, and videogames. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 2020, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Zhou, G. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Applied Psychology: Health and Well 2020, 12, 1019–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.Y.; Hew, T.S.; Ooi, K.B.; Lee, V.H.; Hew, J.J. A hybrid SEM-neural network analysis of social media addiction. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 133, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutgun-Ünal, A.; Deniz, L. Development of the social media addiction scale. AJIT-e: Bilişim Teknolojileri Online Dergisi, 2015, 6, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. B.; Juanatas, I. C.; Juanatas, R. A. TikTok as a Knowledge Source for Programming Learners: a New Form of Nanolearning? 2022 10th International Conference on Information and Education Technology (ICIET); IEEE, 2022; pp. 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrez, Ö.; DeMarinis, V.; Pettersson, J.; Shakra, M. Integration: Policies, Practices, and Experiences, Sweden Country Report. Working papers Global Migration: Consequences and Responses; EU Horizon 2020 Country Report for RESPOND project; Uppsala University, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Extremism Keywords | Online Keywords | Intervention Keywords | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medline via OVID | (“Radical Islam*” OR “Islamic Extrem*” OR Radicali* OR “Homegrown Terror*” OR “Homegrown Threat*” OR “Violent Extrem*” OR Jihad* OR Indoctrinat* OR Terrori* OR “White Supremacis*” OR Neo-Nazi OR “Right-wing Extrem*” OR “Left-wing Extrem*” OR “Religious Extrem*” OR Fundamentalis* OR Anti-Semitis* OR Nativis* OR Islamophob* OR Eco-terror* OR “Al Qaida-inspired” OR “ISIS-inspired” OR Anti-Capitalis*).ti,ab. OR terrorism/ | (“CYBERSPACE” OR “TELECOMMUNICATION systems” OR “INFORMATION technology “ OR “INTERNET” OR “VIRTUAL communit*” OR “ELECTRONIC discussion group*” OR “social media” OR “social networking” OR online OR bebo OR facebook OR nstagram OR linkedin OR meetup OR pinterest OR reddit OR snapchat OR tumblr OR xing OR twitter OR yelp OR youtube OR TikTok OR gab OR odysee OR telegram OR clubhouse OR BeReal OR Twitter OR WhatsApp OR WeChat OR “Sina Weibo” OR 4Chan).ti,ab. OR internet/ OR social media/ OR online social networking/ | (“Public mental health” OR “care in the community” OR “mental health service*” OR “educational service*” OR “social service*” OR “public service partnership*” OR “primary care referral” OR “referral pathways” OR “clinical program*” OR “health promotion” OR prevention).ti,ab. OR community mental health services/ OR health promotion/ | 11 | |

| PsycInfo via Ebscohost | TI (“Radical Islam*” OR “Islamic Extrem*” OR Radicali* OR “Homegrown Terror*” OR “Homegrown Threat*” OR “Violent Extrem*” OR Jihad* OR Indoctrinat* OR Terrori* OR “White Supremacis*” OR Neo-Nazi OR “Right-wing Extrem*” OR “Left-wing Extrem*” OR “Religious Extrem*” OR Fundamentalis* OR Anti-Semitis* OR Nativis* OR Islamophob* OR Eco-terror* OR “Al Qaida-inspired” OR “ISIS-inspired” OR Anti-Capitalis*) OR AB (“Radical Islam*” OR “Islamic Extrem*” OR Radicali* OR “Homegrown Terror*” OR “Homegrown Threat*” OR “Violent Extrem*” OR Jihad* OR Indoctrinat* OR Terrori* OR “White Supremacis*” OR Neo-Nazi OR “Right-wing Extrem*” OR “Left-wing Extrem*” OR “Religious Extrem*” OR Fundamentalis* OR Anti-Semitis* OR Nativis* OR Islamophob* OR Eco-terror* OR “Al Qaida-inspired” OR “ISIS-inspired” OR Anti-Capitalis*) OR (DE “Terrorism”) OR (DE “Extremism”) | TI (“CYBERSPACE” OR “TELECOMMUNICATION systems” OR “INFORMATION technology “ OR “INTERNET” OR “VIRTUAL communit*” OR “ELECTRONIC discussion group*” OR “social media” OR “social networking” OR online OR bebo OR facebook OR nstagram OR linkedin OR meetup OR pinterest OR reddit OR snapchat OR tumblr OR xing OR twitter OR yelp OR youtube OR TikTok OR gab OR odysee OR telegram OR clubhouse OR BeReal OR Twitter OR WhatsApp OR WeChat OR “Sina Weibo” OR 4Chan) OR AB (“CYBERSPACE” OR “TELECOMMUNICATION systems” OR “INFORMATION technology “ OR “INTERNET” OR “VIRTUAL communit*” OR “ELECTRONIC discussion group*” OR “social media” OR “social networking” OR online OR bebo OR facebook OR nstagram OR linkedin OR meetup OR pinterest OR reddit OR snapchat OR tumblr OR xing OR twitter OR yelp OR youtube OR TikTok OR gab OR odysee OR telegram OR clubhouse OR BeReal OR Twitter OR WhatsApp OR WeChat OR “Sina Weibo” OR 4Chan) OR (DE “Internet”) OR (DE “Social Media”) OR (DE “Online Social Networks”) | TI (“Public mental health” OR “care in the community” OR “mental health service*” OR “educational service*” OR “social service*” OR “public service partnership*” OR “primary care referral” OR “referral pathways” OR “clinical program*” OR “health promotion” OR prevention) OR AB (“Public mental health” OR “care in the community” OR “mental health service*” OR “educational service*” OR “social service*” OR “public service partnership*” OR “primary care referral” OR “referral pathways” OR “clinical program*” OR “health promotion” OR prevention) OR DE “Public Mental Health” OR DE “Mental Health Services” OR DE “Social Services” OR DE “Health Promotion” AND DE “Prevention” OR DE “Preventive Health Services” OR DE “Preventive Mental Health Services” | 27 | |

| Web of Science (Core Collection) | TS=(“Radical Islam*” OR “Islamic Extrem*” OR Radicali* OR “Homegrown Terror*” OR “Homegrown Threat*” OR “Violent Extrem*” OR Jihad* OR Indoctrinat* OR Terrori* OR “White Supremacis*” OR Neo-Nazi OR “Right-wing Extrem*” OR “Left-wing Extrem*” OR “Religious Extrem*” OR Fundamentalis* OR Anti-Semitis* OR Nativis* OR Islamophob* OR Eco-terror* OR “Al Qaida-inspired” OR “ISIS-inspired” OR Anti-Capitalis*) | TS=(“CYBERSPACE” OR “TELECOMMUNICATION systems” OR “INFORMATION technology “ OR “INTERNET” OR “VIRTUAL communit*” OR “ELECTRONIC discussion group*” OR “social media” OR “social networking” OR online OR bebo OR facebook OR nstagram OR linkedin OR meetup OR pinterest OR reddit OR snapchat OR tumblr OR xing OR twitter OR yelp OR youtube OR TikTok OR gab OR odysee OR telegram OR clubhouse OR BeReal OR Twitter OR WhatsApp OR WeChat OR “Sina Weibo” OR 4Chan) | TS=(“Public mental health” OR “care in the community” OR “mental health service*” OR “educational service*” OR “social service*” OR “public service partnership*” OR “primary care referral” OR “referral pathways” OR “clinical program*” OR “health promotion” OR prevention) | 90 | |

| Cochrane Library | Radical*, Extrem*, Terrorism, Neo Nazi, terror*, homegrown, jihad, ,indoctrin* supremacis*, right wing, left wing, religious, fundamentalis*anti-semeti*, nativis*, Islam*, Al-Qaida, ISIS, Anti-capitalis* | 4 | |||

| Total | 132 |

| Name | Country/ Milieu | Type of article | Summary | Central aim | Central finding/ argument | Reason for relevance/ reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmitt et al., 2018 | Germany/ Islamist, USA/ Far- right | Information network analysis | An online network analysis of the links between online extremist content and counter extremist messages given that the quantity of extremist messages vastly outnumbers counter messages, both use similar keywords, and automated algorithms may bundle the two types of messages together: counter messages closely or even directly link to extremist content. | Authors used online network analyses to explore what might hinder a successful intervention addressing online radicalisation. | Extremist messages were only two clicks away from counter messaging. The authors suggest that the algorithm filtering and gatekeeping functions directing content and users toward one another, including user amplification through sharing and ‘likes’, as well as the overwhelmingly larger volume of online extremist compared to counter extremist content, together pose almost insurmountable challenges to online interventions targeting extremist content. | Article addressed online extremist content, its relationship with user behaviour and attitudinal shift, and analyses of interventions used. Excluded due to not featuring an intervention but a network analysis of online counter messages. Public mental health approaches might utilise online counter messages as part of an intervention, but no intervention was tested in this article. Rather, several obstacles to counter messaging efficacy were identified. |

| Rusnalasari et al., 2018 | Indonesia/ Islamist | Cross sectional analysis | An analysis of the relationships amongst literacy and belief in and practice of the Indonesian national ideology of Pancasila and literacy in extremist ideological language, with the view of demonstrating that belief and literacy correlate with less vulnerability to online radicalising content: belief and literacy were negatively correlated with vulnerability. | Authors explored if a national ideology warranted testing as an intervention to reduce vulnerability to (or offer protection against) online radicalisation. | National ideology did not seem to reduce vulnerability to or offer protection against online radicalisation. | Article addressed online extremist content, its relationship with language outcomes in the cognitive domain, and theorised the type of intervention that may be useful within education settings. Excluded due to not identifying or testing a specific intervention. |

| Bouzar & Laurent, 2019 | France/ Islamist | Single case study analysis | A qualitative interdisciplinary analysis of the radicalisation of and disengagement intervention with ‘Hamza’, a 15 year old French citizen who attempted several times to leave the country to prepare an attack on France: analysis concludes that Hamza's life course and related trauma experiences led to radicalisation through the interaction of 3 cumulative processes, emotional, relational and cognitive-ideological. | Authors retrospectively identified the conditions necessary to enable a successful intervention, including the first steps of the intervention. | Argued for the efficacy of a multi-disciplinary intervention that analyses an individual’s life trajectory (rather than only one or two time points) informed by two first steps: i) thematic analyses of semi-structured interviews with parents and the radicalised individual; ii) when permission is granted, and access is legal, thematic analyses of mobile phone and computer records revealing the frequency, content, and patterns of engagement between the individual and the extremist recruiters. | Article addressed online extremist content, its relationship with several psychological domains including affect related trauma and outlined the outcome of an intervention. Excluded as specifics of the intervention were not identified. |

| Siegel et al., 2019 | Global/ Several | Narrative review (book chapter) | A book chapter reviewing pathways to and risk factors for radicalisation, theoretical explanations as to why youth may become radicalised, and recommended intervention approaches and examples in six overlapping arenas (family, school, prison, community, internet, government): review concludes that trauma-informed approaches across the six interacting systems are required. | Authors offered a chapter-length overview on reducing terrorism and preventing radicalisation in six overlapping arenas: family, school, prison, community, internet, and government (the latter referring to diverse services at the international, national, and local levels, depending on country and region, e.g., resource provision to schools, prisoner aftercare, public-private partnerships, financial support services, internet monitoring, law enforcement). | Identified five arenas overlapping with the digital arena in which interventions should be located (family, school, prison, community, government) and argued that two needed approaches are largely absent: trauma informed and resilience promotion. | Article addressed online extremist content, its relationship to trauma, and theoretical areas where interventions may take place. Excluded as example specific interventions were only mentioned and none were tested. |

| Tremblay, 2020 | Global/ Extreme right wing, Far-right | Narrative review (editorial) | An editorial focussing on the alt-right movement, using the terrorist attacks in Christchurch in 2019 as an example: the attack was "A sign of our digital era and social-mediatized gaze", having been live streamed on Facebook and widely shared across the virtual community. The development of inclusive habitats, governance, systems and processes were identified as significant goals for health promotion to foster "peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear, racism, violation and other violence". | Author provided a very brief high-level analysis focusing on the intersectionality of discrimination and oppression with radicalisation in the digital, political, and social spheres. | Argued for multi-sector partnerships with public mental health promotion approaches to reduce discrimination, oppression, and radicalisation in the digital, political, and social spheres. | Article addressed online extremist content, and areas within public mental health promotion where interventions may take place. Excluded as no specific interventions mentioned or tested. |

| Schmitt et al., 2021 | Germany/ Anti-refugee | Between Subjects design | A study examining the effects of a counterposing intervention with two different narrative structures, one-sided (counter only) or two-sided (extremist and counter) using the persuasion technique of narrative involvement operationalised as two different types of protagonists (approachable or distant/ neutral). The narrative focused on a controversial topic (how to deal with the number of refugees in Germany) and the effect of each narrative structure on attitude change was measured: participants who read the two-sided narrative showed less reactance; the smaller the reactance, the more they felt involved in the narrative, which in turn led to more positive attitudes towards refugees; variations in protagonist failed to show an effect. | Drawing on findings from the earlier Schmitt et al. (2018) article and theoretical concepts around one sided counter narratives, two sided counter narratives, and narrative involvement, this intervention measured: manipulations, attitude change, freedom threat, and narrative involvement. | Less reactance from a two-sided versus one-sided narrative, that is, from a narrative that included an extremist as well as a counter message. Less reactance was accompanied by increasing narrative involvement (measured as transportation into the narrative and identification with the main character) and self-reported positive attitudinal change toward refugees. | Article addressed online extremist content, its relationship with user behaviour and attitudinal shift, and analyses of the psychological mechanisms involved in mediating the effects of different narrative structures. Excluded as not an intervention but a study that could inform an intervention design using counter messaging. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).