Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

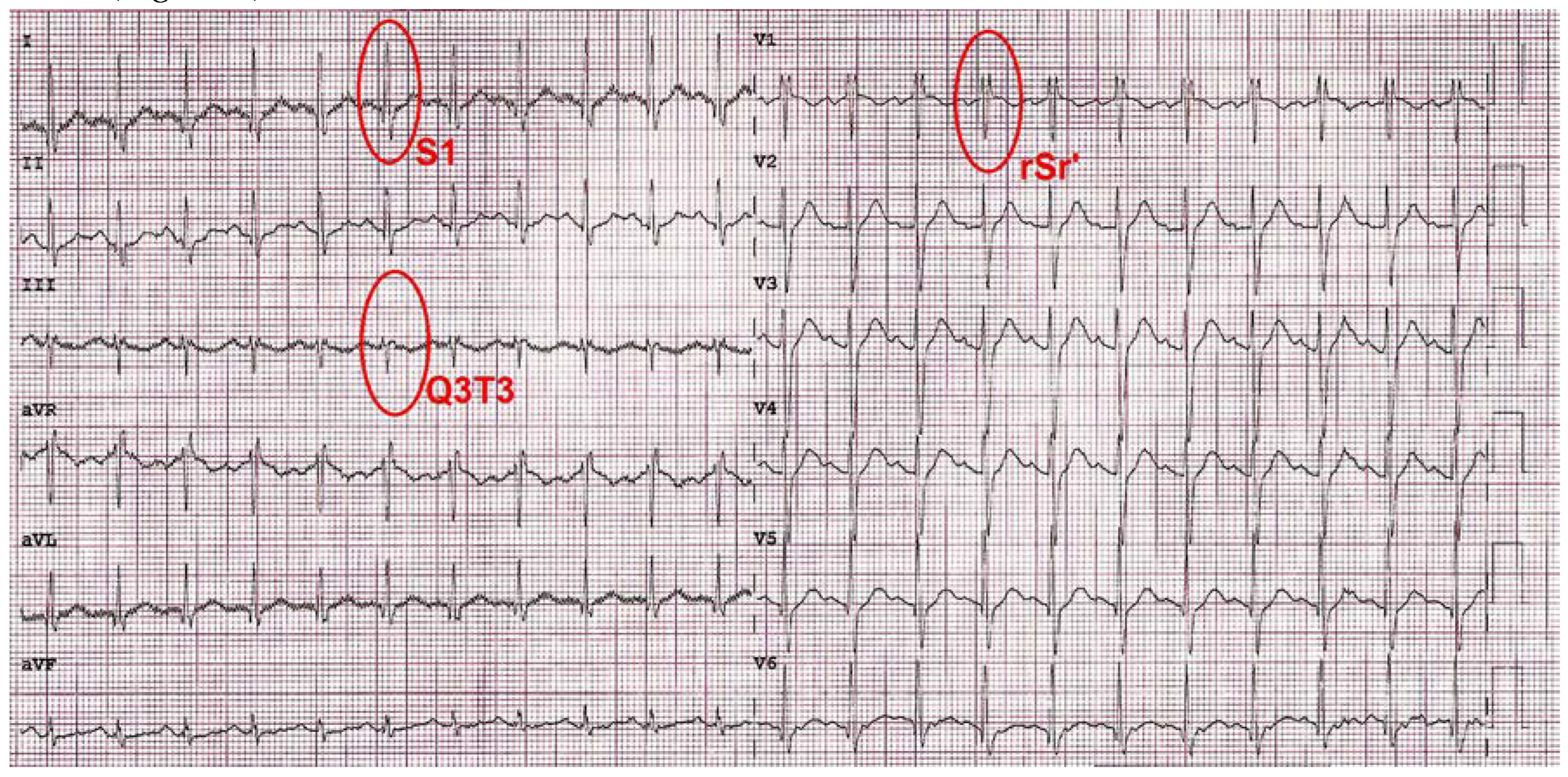

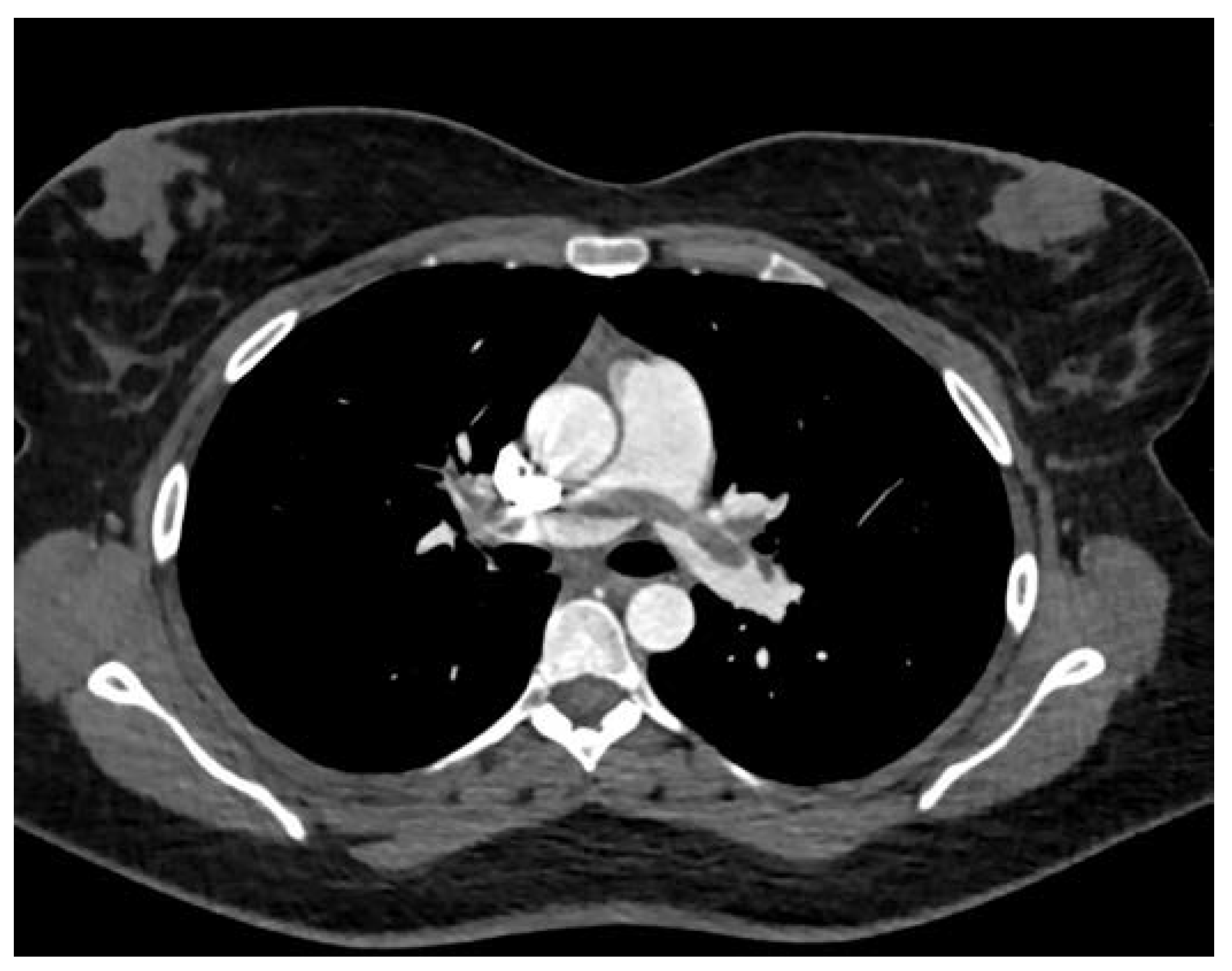

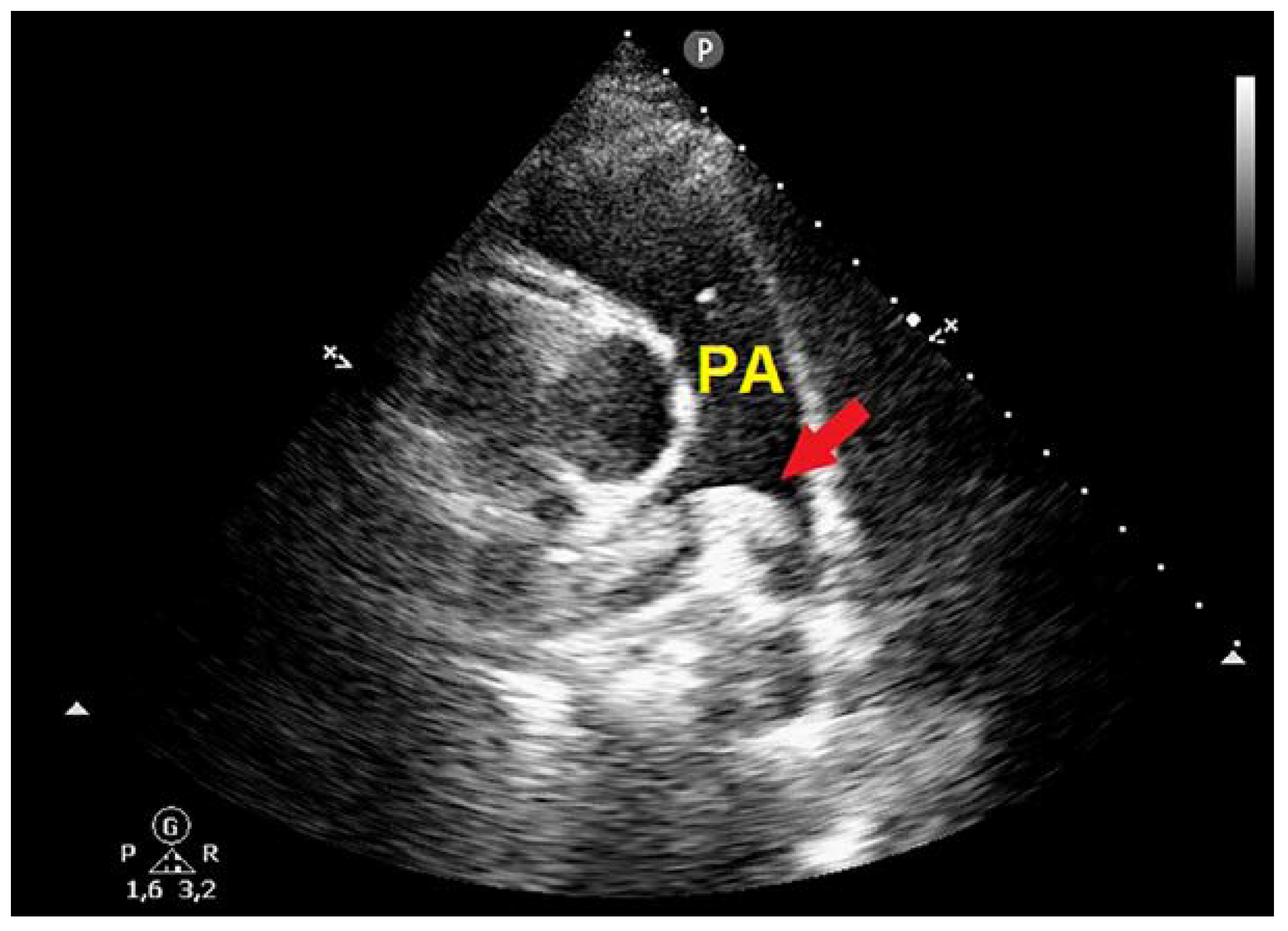

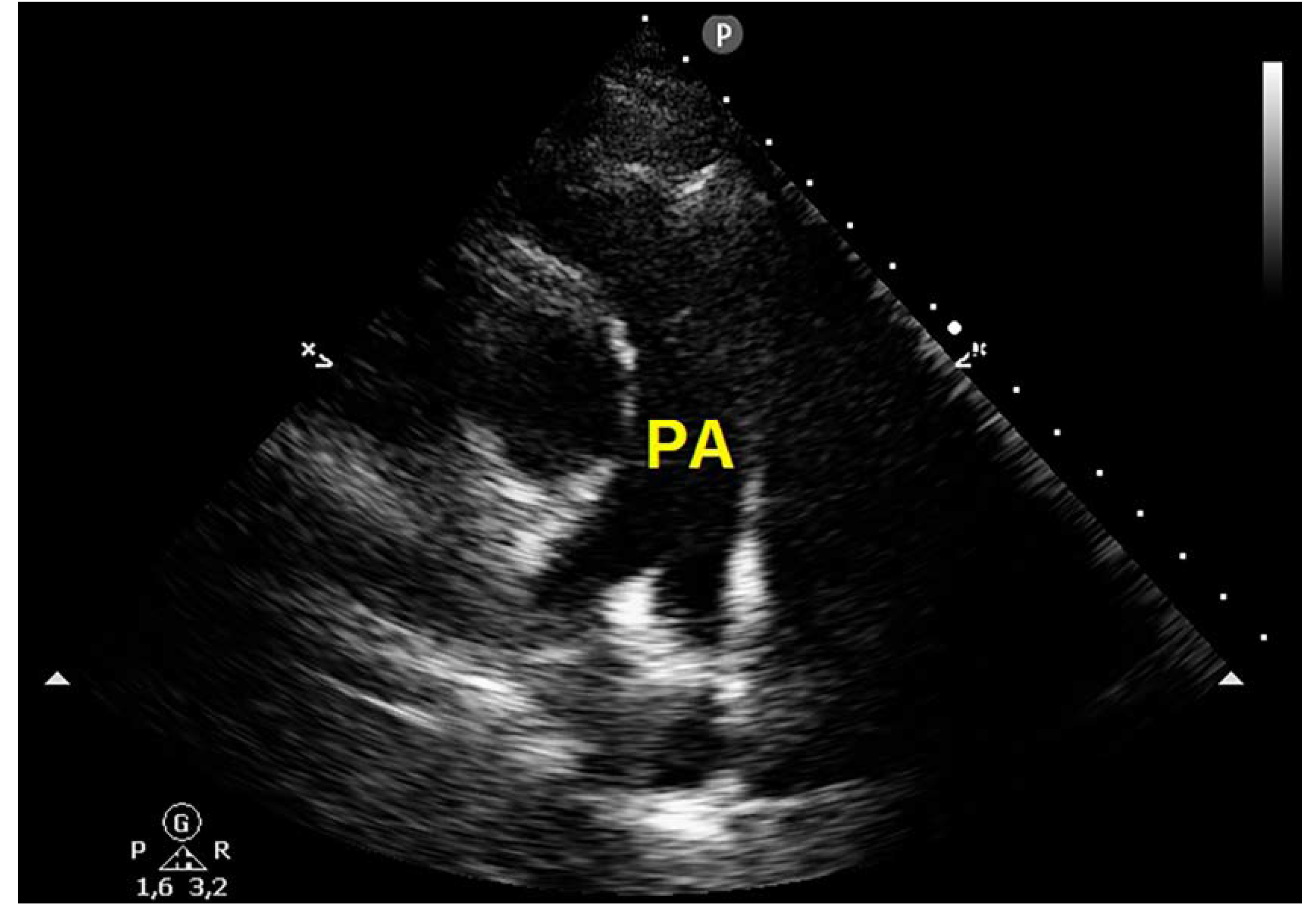

Case Presentation

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; Dimarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D'Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: Implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 1666–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauvel, C.; Weizman, O.; Trimaille, A.; Mika, D.; Pommier, T.; Pace, N.; Douair, A.; Barbin, E.; Fraix, A.; Bouchot, O.; et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: A French multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 3058–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, J.; Tacquard, C.; Severac, F.; Leonard-Lorant, I.; Ohana, M.; Delabranche, X.; Merdji, H.; Clere-Jehl, R.; Schenck, M.; Fagot Gandet, F.; et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middeldorp, S.; Coppens, M.; van Haaps, T.F.; Foppen, M.; Vlaar, A.P.; Muller, M.C.A.; Bouman, C.C.S.; Beenen, L.F.M.; Kootte, R.S.; Heijmans, J.; et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poissy, J.; Goutay, J.; Caplan, M.; Parmentier, E.; Duburcq, T.; Lassalle, F.; Jeanpierre, E.; Rauch, A.; Labreuche, J.; Susen, S.; et al. Pulmonary Embolism in Patients With COVID-19: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation 2020, 142, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, M.M.; Vicente Reparaz, M.L.A.; Ruiz, J.I.; Acuna, M.A.; Casali, C.E.; Aizpurua, M.F.; Mahuad, C.V.; Eciolaza, S.; Ventura, A.; Garate, G.M. Mild COVID-19 Illness as a Risk Factor for Venous Thromboembolism. Cureus 2021, 13, e18236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pace, D.; Ariotti, S.; Persampieri, S.; Patti, G.; Lupi, A. Unexpected Pulmonary Embolism Late After Recovery from Mild COVID-19? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 2021, 8, 002854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.W.; Roberts, J.C.; Weaver, C.N.; Anderson, J.S.; Wong, M.L. Patients with Mild COVID-19 Symptoms and Coincident Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Series. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2020, 4, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanwongse, K.; Shabarek, N. Bilateral Popliteal Vein Thrombosis, Acute Pulmonary Embolism and Mild COVID-19. Cureus 2020, 12, e11213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, D.F.; Diella, L.; Fabrizio, C.; Sulpasso, R.; Bottalico, I.F.; Calamo, A.; Santoro, C.R.; Brindicci, G.; Bruno, G.; Mastroianni, A.; et al. Peculiar clinical presentation of COVID-19 and predictors of mortality in the elderly: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 105, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitruk-Ware, R. Hormonal contraception and thrombosis. Fertil Steril 2016, 106, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Ojima, T. The epidemiological characteristics of thromboembolism related to oral contraceptives in Japan: Results of a national survey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2021, 47, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegeman, B.H.; de Bastos, M.; Rosendaal, F.R.; van Hylckama Vlieg, A.; Helmerhorst, F.M.; Stijnen, T.; Dekkers, O.M. Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013, 347, f5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorini, N.B.; Garagoli, F.; Bustamante, R.C.; Pizarro, R. Acute pulmonary embolism in a patient with mild COVID-19 symptoms: A case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2021, 5, ytaa563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela-Vallejo, L.; Corredor-Orlandelli, D.; Alzate-Ricaurte, S.; Hernandez-Santamaria, V.; Aguirre-Ruiz, J.F.; Pena-Pena, A. Hormonal Contraception and Massive Pulmonary Embolism in a COVID-19 Ambulatory Patient: A Case Report. Clin Pract 2021, 11, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G.; Becattini, C.; Bueno, H.; Geersing, G.J.; Harjola, V.P.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Jennings, C.S.; Jimenez, D.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 543–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Zimba, O.; Gasparyan, A.Y. Thrombosis in Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) through the prism of Virchow's triad. Clin Rheumatol 2020, 39, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorog, D.A.; Storey, R.F.; Gurbel, P.A.; Tantry, U.S.; Berger, J.S.; Chan, M.Y.; Duerschmied, D.; Smyth, S.S.; Parker, W.A.E.; Ajjan, R.A.; et al. Current and novel biomarkers of thrombotic risk in COVID-19: A Consensus Statement from the International COVID-19 Thrombosis Biomarkers Colloquium. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022, 19, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, I.; Ferrazzi, E.; Ciavarella, A.; Erra, R.; Iurlaro, E.; Ossola, M.; Lombardi, A.; Blasi, F.; Mosca, F.; Peyvandi, F. Pulmonary embolism in a young pregnant woman with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020, 191, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinathan, G.; Sathar, J. Haematological manifestations, mechanisms of thrombosis and anti-coagulation in COVID-19 disease: A review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020, 56, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manne, B.K.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.A.; Portier, I.; Rowley, J.W.; Stubben, C.; Petrey, A.C.; Tolley, N.D.; Guo, L.; Cody, M.; et al. Platelet gene expression and function in patients with COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Elalamy, I.; Kastritis, E.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Politou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Gerotziafas, G.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol 2020, 95, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muresan, A.V.; Halmaciu, I.; Arbanasi, E.M.; Kaller, R.; Arbanasi, E.M.; Budisca, O.A.; Melinte, R.M.; Vunvulea, V.; Filep, R.C.; Marginean, L.; et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index, Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score, and Inflammatory Biomarkers as Predictors of Deep Vein Thrombosis, Acute Pulmonary Embolism, and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albini, A.; Di Guardo, G.; Noonan, D.M.; Lombardo, M. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE-2, is expressed on many different cell types: Implications for ACE-inhibitor- and angiotensin II receptor blocker-based cardiovascular therapies. Intern Emerg Med 2020, 15, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albini, A.; Calabrone, L.; Carlini, V.; Benedetto, N.; Lombardo, M.; Bruno, A.; Noonan, D.M. Preliminary Evidence for IL-10-Induced ACE2 mRNA Expression in Lung-Derived and Endothelial Cells: Implications for SARS-Cov-2 ARDS Pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 718136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulicek, P.; Ivanova, E.; Kostal, M.; Sadilek, P.; Beranek, M.; Zak, P.; Hirmerova, J. Analysis of Risk Factors of Stroke and Venous Thromboembolism in Females With Oral Contraceptives Use. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2018, 24, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.I.; Buchsbaum, R.J. COVID-19 and Hypercoagulability: Potential Impact on Management with Oral Contraceptives, Estrogen Therapy and Pregnancy. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J.; Corbett, J.; Forni, L.; Hooper, L.; Hughes, F.; Minto, G.; Moss, C.; Price, S.; Whyte, G.; Woodcock, T.; et al. A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: Definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Ann Med 2019, 51, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, L.F.; Kroft, L.J.M.; van der Wal, L.I.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Eikenboom, J.; de Jonge, E.; Huisman, M.V.; Klok, F.A. Clinical and computed tomography characteristics of COVID-19 associated acute pulmonary embolism: A different phenotype of thrombotic disease? Thromb Res 2020, 193, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mathew, S.; Pappachan, J.M. Acute cor pulmonale from saddle pulmonary embolism in a patient with previous COVID-19: Should we prolong prophylactic anticoagulation? Int J Infect Dis 2020, 97, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zetter, M.A.; Guerra, E.C.; Hernandez, V.S.; Mahata, S.K.; Eiden, L.E. ACE2 in the second act of COVID-19 syndrome: Peptide dysregulation and possible correction with oestrogen. J Neuroendocrinol 2021, 33, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sun, X.; J, L.V.; Kon, N.D.; Ferrario, C.M.; Groban, L. Estrogen receptors are linked to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM-17), and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) expression in the human atrium: Insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res 2021, 44, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzig, K.E.; Canepa-Escaro, F.; Schiliro, M.; Berdnikovs, S.; Prakash, Y.S.; Chiarella, S.E. Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2020, 318, L1280–L1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnacci, A. Hormonal contraception: Venous and arterial disease. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2017, 22, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalan, R.; Boehm, B.O. The implications of COVID-19 infection on the endothelium: A metabolic vascular perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021, 37, e3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.E.; Umapathi, T.; Chua, K.; Chia, Y.W.; Wong, S.W.; Tan, G.W.L.; Chandrasekar, S.; Lum, Y.H.; Vasoo, S.; Dalan, R. Delayed catastrophic thrombotic events in young and asymptomatic post COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Value of D-dimer levels for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: An analysis of 32 cases with computed tomography pulmonary angiography. Exp Ther Med 2018, 16, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Fogarty, H.; Dyer, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Bannan, C.; Nadarajan, P.; Bergin, C.; O'Farrelly, C.; Conlon, N.; Bourke, N.M.; et al. Prolonged elevation of D-dimer levels in convalescent COVID-19 patients is independent of the acute phase response. J Thromb Haemost 2021, 19, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousefi, N.A. An oral combined contraceptive user with elevated D-dimer post COVID-19: A case report. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Meijenfeldt, F.A.; Havervall, S.; Adelmeijer, J.; Lundstrom, A.; Magnusson, M.; Mackman, N.; Thalin, C.; Lisman, T. Sustained prothrombotic changes in COVID-19 patients 4 months after hospital discharge. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, H.; Townsend, L.; Morrin, H.; Ahmad, A.; Comerford, C.; Karampini, E.; Englert, H.; Byrne, M.; Bergin, C.; O'Sullivan, J.M.; et al. Persistent endotheliopathy in the pathogenesis of long COVID syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2021, 19, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maria, E.; Latini, A.; Borgiani, P.; Novelli, G. Genetic variants of the human host influencing the coronavirus-associated phenotypes (SARS, MERS and COVID-19): Rapid systematic review and field synopsis. Hum Genomics 2020, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutch, C.; Thrombosis, C.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Grootenboers, M.; Braken, S.J.E.; Burggraaf, J.L.I.; van Bussel, B.C.T.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Ten Cate, H.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications and overall survival in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the second and first wave. Thromb Res 2021, 199, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caci, G.; Albini, A.; Malerba, M.; Noonan, D.M.; Pochetti, P.; Polosa, R. COVID-19 and Obesity: Dangerous Liaisons. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikdeli, B.; Madhavan, M.V.; Jimenez, D.; Chuich, T.; Dreyfus, I.; Driggin, E.; Nigoghossian, C.; Ageno, W.; Madjid, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-Up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 2950–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biochemical parameters | Hospital admission | Hospital discharge |

|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.5 | 12.8 |

| HCT (%) | 42 | 39 |

| WBC (x 109/L) | 12.3 | 6.9 |

| NLR | 7.8 | 1.5 |

| PLTs (x 109/L) | 198 | 281 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 2.9 | 0.2 |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 9546 | 1763 |

| Troponin I (ng/ml) | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| BNP (pg/ml) | 19 | 6 |

| PT (sec) | 11 | 12.5 |

| aPTT (sec) | 23.4 | 19.5 |

| INR | 1.0 | 1.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).