1. Introduction

The escalating quantity of electronic waste (e-waste) and its detrimental effects on both the environment and human health have rendered it a significant worldwide ecological issue. The implementation of recycling and appropriate disposal methods for electronic waste is imperative in promoting sustainable development [

1]. To address e-waste, several governments have passed laws requiring the recycling of electronic equipment and promoting environmentally responsible disposal [

2]. This includes encouraging electronic device reuse and recycling, requiring producers to properly dispose of their products, and motivating customers to responsibly dispose of their electronic trash. This also includes holding manufacturers accountable for product disposal. Repairing and upgrading gadgets, donating or selling them, and recycling them at licensed facilities can reduce e-waste [

3]. Electronic waste improperly handled and disposed of may expose the environment with toxic substances.

Conventional methods of incentivizing e-waste collection are frequently inadequate owing to insufficient incentives calculation technique and a lack of transparency [

4]. The advent of blockchain technology has presented novel opportunities for the implementation of incentivization mechanisms for the purpose of electronic waste (e-waste) collection [

5]. That is why this paper proposed and evaluate various incentivization schemes that utilize blockchain technology in the context of e-waste collection and assess their effectiveness The utilization of blockchain-based incentivization schemes for the collection of e-waste involves the application of blockchain technology, particularly smart contracts, to offer a decentralized and transparent approach to motivating individuals or organizations to gather their electronic waste. Numerous research studies have put forth incentivization plans based on blockchain technology for the purpose of e-waste collection [

5].

In comparison to conventional incentivization schemes, incentivization schemes based on blockchain technology present a number of benefits. To begin with, the utilization of blockchain technology offers transparency and security, thereby rendering fraudulent activities arduous to perpetuate [

6]. Furthermore, the decentralized characteristic of blockchain technology obviates the necessity for central governing bodies, thereby mitigating the potential for malfeasance and deceit [

7]. In addition, blockchain-based methodologies offer contemporaneous monitoring of e-waste retrieval and reprocessing, allowing governing bodies to evaluate the efficiency of the initiative and implement requisite modifications [

8]. The utilization of blockchain technology in incentivizing e-waste collection has demonstrated encouraging outcomes in enhancing e-waste recycling rates and mitigating the quantity of e-waste that is deposited in landfills [

9]. The blockchain technology's transparency and security render it a suitable option for incentivization schemes, while its ability to track in real-time allows authorities to assess the program's efficacy. Subsequent research work ought to prioritize the assessment of the enduring effects of blockchain-driven incentivization systems for electronic waste retrieval, as well as the identification of plausible hindrances to their adoption [

5].

One of the feasible attempt for collection of e-waste lies with the principle of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). This is a policy approach holds manufacturers responsible for the safe and legal disposal of their products once they have reached the end of their useful lives [

10]. The objective of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is to incentivize enterprises to manufacture environmentally sustainable, long-lasting, and reusable goods [

11]. An additional objective of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is to transfer the economic responsibility of managing waste from the government's budget to other entities. [

12]. In compliance with the regulations of an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) program, manufacturers are obligated to collect and appropriately dispose of products that have reached the end of their useful life. The item has the potential to undergo recycling, reutilization, or environmentally sound disposal [

13]. Under this plan, manufacturers will receive financial incentives to produce goods that have high rates of recyclability and reusability, and to integrate recycled materials into their products whenever feasible [

14]. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) initiatives can be implemented across various tiers of governance, ranging from the national to the regional and local levels [

15]. This initiative represents an important effort aimed at establishing a systematic and clearly defined methodology for the gathering of electronic waste. Although an incentive package has been disclosed for the collection of e-waste, regrettably, there is a lack of established techniques to determine the associated incentive for e-waste collection. Hence, the present study deems it imperative to establish a suitable methodology for generating incentives.

Considering this approach, the current research will be contributing in so many ways, but the most crucial contributions will lie to the following:

The current research makes a contribution towards the creation of a weighted scoring model that makes use of a vector space method. To be more specific, the representation of an incentive itself is a vector in an n-dimensional space, whereas the representation of each individual task that is connected with an incentive is a wide space within a vector space. In this case, the number of tasks or components is given by the letter n, and the set of tasks is indicated by the letters A, B, C, D, and E. The importance of the related variable in the task at hand is indicated by the magnitude of each component of the vector.

During the process of mapping, this research presents a method that proposes assigning obtained values to the various factors that have an effect on the collection of e-waste. Utilizing a numeric scale that is controlled by the central command and control facility for e-waste smart contracts is one way to accomplish the allocation.

In the course of the research, we developed and put into practice a smart contract for handling of electronic waste, often known as e-waste, making use of a proposed incentive structure. The system has been successfully deployed, and all of its components are fully functioning; it is now ready to begin operations in real-world environments (see Appendix 1).

Apart from this section, which expresses the background of the study,

Section 2 presents the research-related work.

Section 3 discusses the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the evaluation of the smart contract implementation,

Section 5 presents the principal findings and interpretation, and

Section 6 presents the conclusion of the paper.

2. Related Work

The escalating volume of electronic waste (e-waste) and its detrimental effects on human health and the environment have rendered it a significant ecological concern. Consequently, research in this domain has gained substantial significance within the research community. In the realm of e-waste management, it is imperative to establish sustainable research solutions for the purpose of managing electronic waste. The present paper provides a comprehensive review of the current literature on the management of electronic waste through the utilization of blockchain technology. Some of the crucial research in the area has been presented below:

McGrenary [

16] proposed a blockchain-based solution for e-waste in the form of satellite re-cycling consoles placed in public spaces, at which users could trade in obsolete electronics for cryptocurrency. Information entered into the consoles about individual products is recorded in the blockchain ledger, and the digital token's worth is pegged to the expected price of fixing or refurbishing those products. There is less need for recourse to legal mechanisms for dispute resolution because all parties, including the original manufacturer, have visibility into the products' financial and physical outcomes, and the immutability of the record ensures honest transactions in profit sharing. In a similar approach, Dua et al. [

5] propose a viable strategy for managing electronic waste through the utilization of blockchain technology within the framework of the fifth generation (5G) landscape. The study emphasized the importance of a fundamental concept in the creation of intelligent agreements that are linked to multiple stakeholders participating in the procedure. Therefore, the study recognizes that the integration of all the necessary activities within the smart contract is essential. Furthermore, Chaudhary et al. [

17] have proposed a range of blockchain-based applications that can be utilized in the waste management industry. These applications enable stakeholders involved in the e-waste chain to monitor and track the movement of e-waste in real-time, thereby highlighting instances of non-compliance with the established regulations for efficient e-waste treatment. Sambare et al. [

18] research demonstrates that the dynamic blockchain technology, such as Ethereum, possesses extensive applications across multiple sectors. However, its potential in waste management remains relatively unexplored. Therefore, the study highlights the various opportunities presented by blockchain technology in the effective management of diverse waste categories, including Solid Waste, Electronic Waste, Medical Waste, and Industrial Waste.

As more and more research is developed concerning the use of blockchain in e-waste management, a blockchain-based smart contract-based approach for e-waste management was proposed by Gupta and Bedi [

19]. It is believed that the implementation of smart contracts for e-waste management will enhance coordination among multiple stakeholders in the supply chain. The implementation of this measure would empower the governing body to oversee the management of electronic waste, including its collection and recycling. The utilisation of blockchain technology in logistics and supply networks was introduced by Pedrosa and Pau [

20]. The paper posited that blockchain technology could potentially address various challenges in supply chain management, including the establishment of a secure and authenticated logistic system, the management of trust issues, and the facilitation of information exchange within supply networks. The emergence of blockchain technology has shown promise as a potential solution for managing e-waste. Therefore, the implementation of incentivization schemes for e-waste collection is crucial to circumvent traditional incentivization schemes that rely solely on central authorities to administer rewards. Previous research endeavors aimed at formulating incentives have been conducted. Sahoo and Halder [

21] conducted a study proposing an e-waste management system that utilises smart contract and blockchain technology. The system is designed to encompass both forward and reverse supply chains. The proposed solution facilitates the comprehensive tracking of the complete life cycles of electronic products, starting from their production phase, through their disposal at e-waste centers, and culminating in their reprocessing into raw materials. The authors of the study have identified various challenges and limitations that are currently being encountered by block-chain-based proposals. These include inadequate coverage of the entire life cycle of e-wastes, scalability issues, and incentivization concerns. However, the study does not provide a detailed account of the incentivization techniques employed.

It is noteworthy to mention that the aforementioned literature [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] primarily centers on the management of e-waste. However, the implementation of a specific formal and consistent incentive flow methodology for practical purposes has not been extensively examined. This paper proposes a study on the potential application of blockchain technology for incentivization schemes in e-waste collection. The motivation for this research stems from the successful implementation of similar incentivization schemes in e-waste management, as demonstrated in previous studies [

21], and the subsequent works of [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The proposed techniques aim to enhance e-waste real-time tracking, which would enable authorities to monitor the long-term impact of blockchain-based incentivization schemes on e-waste collection.

3. Methodology

The present study employs the Design Science Research Methodology [

26,

27] as its applicable research methodology. The rationale for implementing this particular methodology is based on the observation that the current state of e-waste collection follows a sequential process that begins with the manufacturer and ends with the consumer. The task at hand pertains to the development and evaluation of the pipeline-process aimed at tackling a strategic e-waste collection initiative. The efficacy of the proposed solution is contingent upon the technique presented, given that the research problem has been identified and expounded upon in

Section 1.

3.1. Conceptual Design

The main technique under this current study lies incentivization scheme. The incentivization scheme proposed is founded on vector space approach and implemented in a blockchain smart contract platform that keeps track of the gathering and recording of electronic waste via smart contract. The smart contract incentivizes both individuals and businesses/agencies for their efforts to collect and organize electronic waste. The incentives are dispensed in the configuration of digital tokens, which are exchangeable for commodities or amenities, for this specific case, Ethereum was used.

The operational procedure of e-waste collection operates by having Individuals and businesses/agencies alike engaging in the retrieval of electronic waste, which can then be transported to designated facilities for proper disposal. The center or controlling unit is responsible for the collection of e- waste and carries out the process of verifying and weighing said waste. The issuance of incentives /tokens entails the registration of authenticated e-waste on a blockchain system, followed by the allocation of digital tokens to either individuals or enterprises. The number of tokens disbursed is contingent upon the weight of the electronic waste associated to the role of collections of the e-waste. The utilization of blockchain technology guarantees both transparency and security, thereby establishing a resilient safeguard against deceitful actions. The platform facilitates real-time monitoring of e-waste collection, thereby enabling authorities to assess the efficacy of the program.

3.1.1. Incentives Generation for the Incentivization Scheme

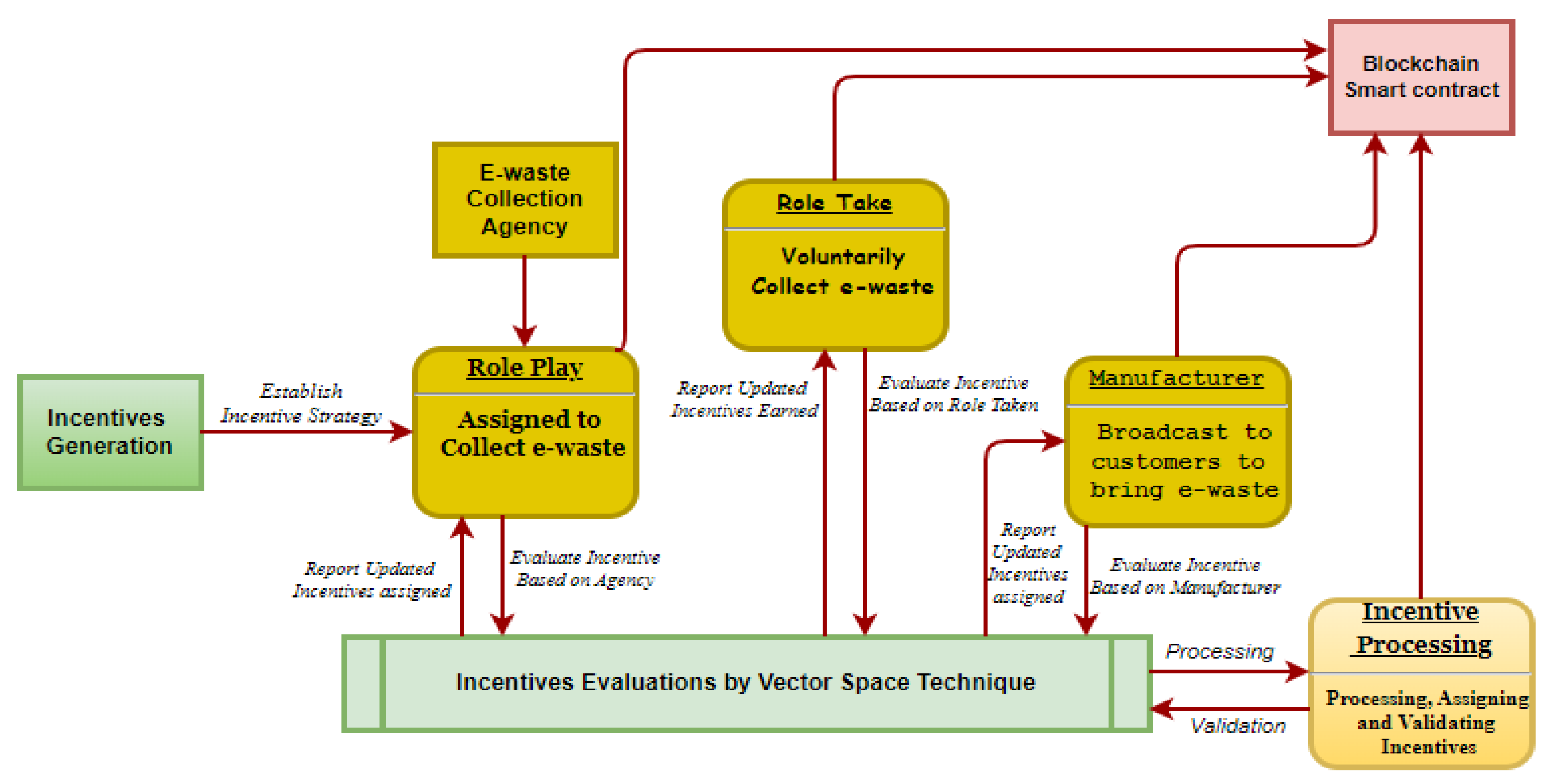

This study proposes an incentive-based approach that utilizes blockchain technology to precisely monitor the disposal of electronic products, with the aim of mitigating the environmental impact of e-waste. The crucial aspect of the model lies with Incentivization scheme for incentive generation. However, the general approach of incentives generation model (see

Figure 1.) dwells on “Role based “as the practical application of the tasks involve.

The major component of the concept lies with “E-waste collection agency”, “The e-device’s manufacturers Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy”, “The Role-based approach”, “The incentive generation” and “Incentive processing”. The e-waste collection agency, “The e-waste controlling incentive processing unit” and “the manufacturers of electronic device” are all responsible for defining and assigning tasks for the collection of e-waste. These are all independent bodies, but can coordinate to set out tasks for e-waste collection and assigning incentives.

The term "role-based" is defined operationally as the specific functions and responsibilities of individuals or agencies involved in the collection of e-waste, which can be expressed through either "role-playing" or "role-taking" or a combination of both. The management and monitoring of incentives related to the collection of e-waste can be facilitated through the implementation of keeping the records inspired by blockchain smart contract technology. A reliable tool is typically required for individuals or agencies to effectively gather and monitor e-waste records over an extended period of time. The implementation of blockchain technology has the potential to facilitate the perpetual documentation of this transactional activity, which is linked to incentivization.

The operational definition of “Role-taking” dwells on voluntary task of organizing and collecting electronic waste. This is motivated by the decision to undertake a particular role is contingent upon the unique requirements of the individual or the situational context in which it is being assumed. The present research also consider role taking for incentives as the voluntary engagement of an individual in the collection of e-waste. When contemplating incentives, it is crucial to consider the unique preferences and requirements of the individual tasked with performing the activity. The motivational factors of individuals may vary, with some being inclined towards financial incentives and others being more inclined towards recognition

Role-playing on the other hand is also operationally defined as a practice that pertains to the assignment of tasks to individuals or organizations involved in the organizing and collecting of electronic waste. The present study also considers "role played for incentives" as the act of an agency which can be supplier of retailers or independent agency assigning tasks related to the collection of e-waste, along with its corresponding incentives. Offering incentives for a particular role can aid in aligning individual and organizational objectives and foster a sense of accountability towards assigned tasks.

The allocation of tasks for incentivization, as posited by this research should also falls within the purview of electronic device manufacturers, who may consider implementing relevant policies in this regard. The effectiveness of incentives can also be influenced by the manner in which a task is allocated. Assigning tasks with well-defined expectations and objectives increases the likelihood of successful completion and positive response to incentives. It is crucial to guarantee that tasks are allocated in a just manner and that rewards are distributed impartially to prevent any feelings of bitterness or decrease in motivation.

The effectiveness of incentive strategies cannot be determined by a universal formula [

28]. However, a thorough analysis of the specific individual, task, and organisational variables involved can facilitate the identification of successful incentive approaches. That is why processing of incentives in each scenario will vary due to the distinct objectives of the respective tasks. The implementation of a Blockchain-based recording and monitoring system involves the assignment of specific roles and corresponding incentives for each task, which are associated with the concepts of role-playing and role-taking. Individuals who assume specific roles and engage in role-playing activities have the potential to effectively gather electronic waste materials and subsequently dispose of them in designated locations. The role of agencies involved in e-waste collection is defined and described as role-playing. Additionally, manufacturers have the ability to establish an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy framework, which designates the responsibility of managing electronic waste to the manufacturers of electronic devices.

The integration of the E-waste collection agency, the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy of e-device manufacturers, the Role-based approach, the incentive generation, and the incentive processing units collectively provide the necessary information to the blockchain. Each individual block within the blockchain will comprise of a set of "data" and its corresponding "hash". The sequence of events pertaining to the collection of e-waste can be compared across all associated tasks.

3.1.2. The Vector Space Incentivization.

A vector space is a mathematical structure that consists of a set of vectors and two operations, vector addition and scalar multiplication [

29]. Vectors are typically represented as ordered n-tuples of real numbers, where n is the number of dimensions or components in the vector [

30]. The operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication allow for the manipulation and combination of vectors, and form the basis for many mathematical concepts and applications [

31]. The concept of a vector space is a fundamental one in mathematics and has many applications in many fields, and that is why this study is adopting it for establishing Incentivization scheme. The properties of a vector space are governed by a set of axioms, which specify the behavior of vector addition and scalar multiplication [

32]. These axioms include closure under addition and scalar multiplication, distributivity of scalar multiplication over vector addition, and associativity of vector addition and scalar multiplication [

33]. Additionally, a vector space must contain a zero vector, which is the additive identity element, and each vector must have an additive inverse. Vector spaces can be finite-dimensional or infinite-dimensional, depending on the number of dimensions or components in the vectors [

34]. Finite-dimensional vector spaces are more familiar and easier to visualize, but infinite-dimensional vector spaces have important applications in analysis [

35]. The concept of a vector space provides a powerful and flexible framework for representing and manipulating vectors.

In this study, the vectors are conceptual assign to be “Incentives” and the space is the “Role-based in collection of e-waste”. The Incentivization of a vector space is defined by a set of axioms that describe the properties and structure of the space (“Role-based in collection of e-waste”). These axioms further specify the behavior of vector addition and scalar multiplication. Crucial to this is “Closure under vector addition” which dwells on the sum of any two vectors in the space. This further with other properties like “Associativity of vector addition” which describe various order in which vectors are added. Therefore, it suggests that each way of mapping incentive and role based does not affect the result.

Consider a case, where a, b, and c are involved, it would then be a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c and the result will not change. Similarly, a “Commutativity of vector addition takes the order in which vectors are added does not affect the result; a + b = b + a. The phenomenon also reflects to the existing of a zero vector where a vector in the space, denoted by 0, such that a + 0 = a for all vectors an in the space. Another dimension lies with existence of additive inverses where for every vector an in the space, there is a vector -a in the space such that a + (-a) = 0.

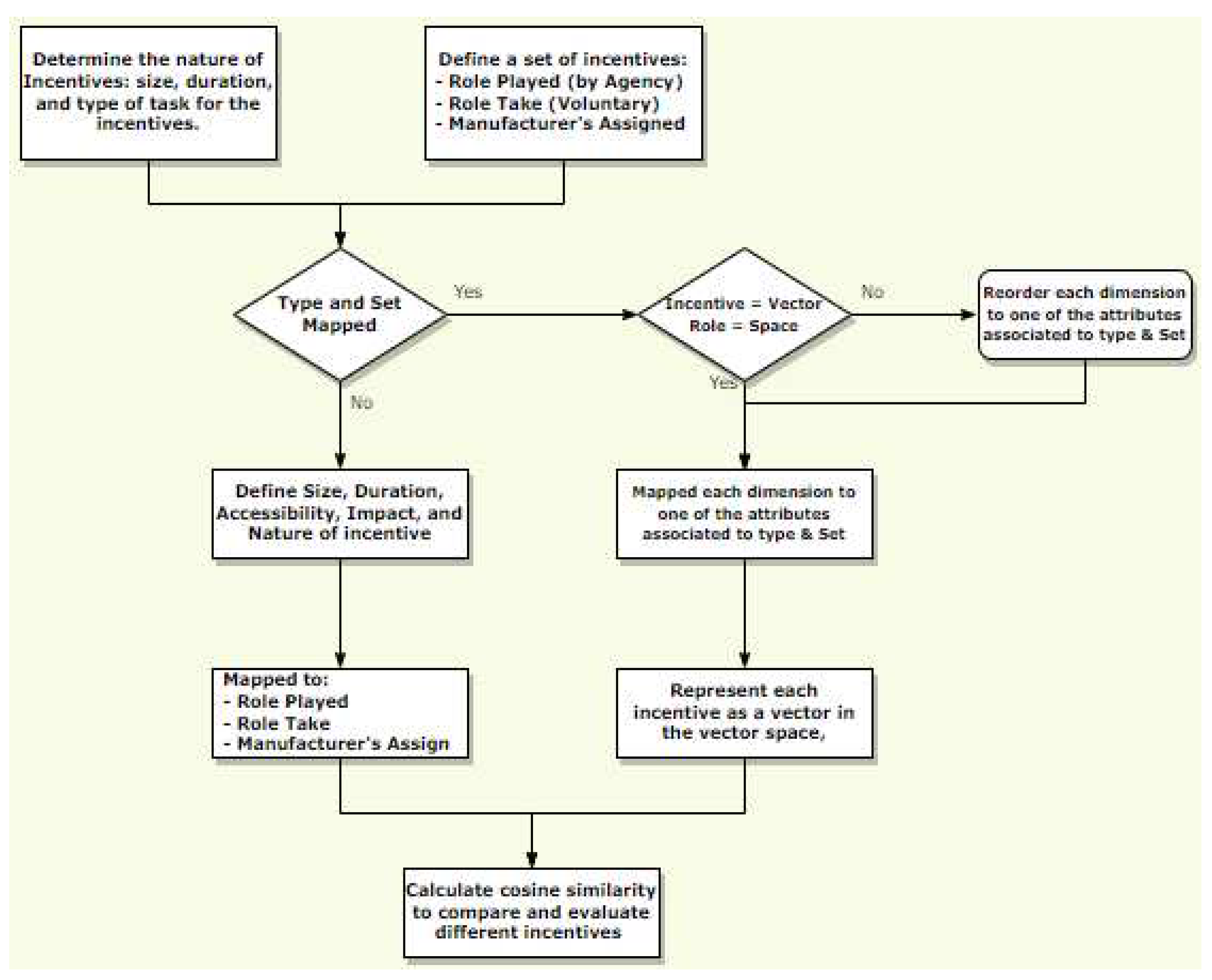

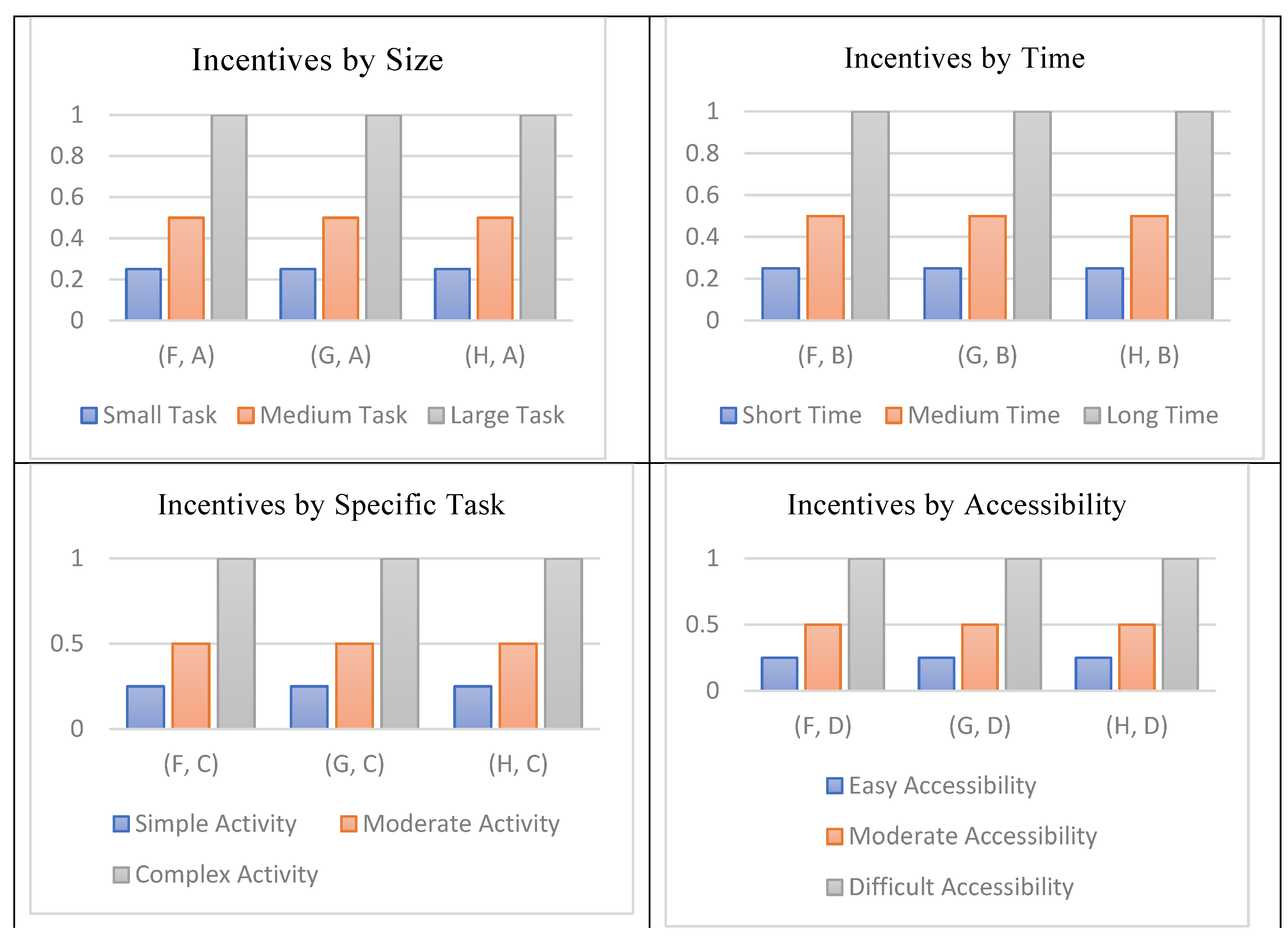

As was described above that the vector space model can be applied to incentives by representing different types of incentives as vectors in a high-dimensional space. Each dimension in the vector space represents a different attribute or characteristic of the incentives, such as the size, duration, or type and nature of the incentives (see

Figure 2).

The utilization of the vector space model in the context of incentives involves an examination of the characteristics and composition of the incentive structure. This research enables the identification of the nature of incentive and the corresponding set of incentive attribute. The incentives are characterized by tasks that are linked to size, duration, and specific activities. The set of incentives comprises three distinct categories, namely "incentives associated with role-played", "incentives associated with role-taking", and "incentives associated with assigned tasks". Hence, by delineating the characteristics of the incentives and the prescribed incentives, it is possible to conceptualize vectors of "Incentives" that are linked to the domain of "Role-based in the collection of e-waste".

Therefore, the concept of incentive based on "Size" refers to the quantitative value of the reward or benefit provided in relation to the magnitude of the tasks accomplished in the process of collecting e-waste. When dealing with substantial assignments, it can be advantageous to divide them into smaller, more feasible components and provide rewards for accomplishing each component. Maintaining high levels of motivation throughout the process can be beneficial in reducing the perceived magnitude of the overall task.

The incentive structure based on "Duration" pertains to the temporal aspect of e-waste task completion, determining the length of time during which the incentive will remain applicable. Offering time-based incentives for e-waste collection that are time-sensitive can be successful. A bonus or additional recognition could be given, for instance, if the assignment is completed within a specific amount of time.

The categorization of incentives based on "Type" denotes that the reward is contingent upon the completion of a particular category of tasks pertaining to the gathering of electronic waste. Incentives can also be tailored to specific activities within a task. For example, if a task involves a lot of exploration of areas that e-waste could be available most, and offering a per-coverage incentive could be motivating.

The concept of incentives as related to "Accessibility" pertains to the degree of ease with which the incentive can be accessed in relation to the entirety of tasks associated with the collection of electronic waste. Tasks that are easily accessible (e.g., can be completed remotely or from home) could be incentivized with flexible work arrangements or other perks.

The present study examines the impact of incentives on the performance of e-waste collection, as indicated by "Impact". This particular scenario facilitates the computation of incentive similarities, thereby enabling the comparison and assessment of diverse incentives. Incentivizing performance can help ensure that tasks are completed to a high standard. This could involve bonuses for achieving certain benchmarks or recognition for exceptional work.

Upon defining the attributes for each incentive, the subsequent step involves representing each incentive as a vector within the vector space. In this context, each dimension of the vector corresponds to one of the attributes. Each dimension in the vector corresponds to the degree or level of a particular attribute for the incentive.

The utilization of the aforementioned concept can be exemplified through the following scenario: Considering that an incentive is produced by the vector space:

[1000, 6, 1, 0.8, 0.5]

The aforementioned suggests that the initial dimension denotes the magnitude of the incentive, which is $1000. The second dimension pertains to the duration of the incentives, which spans over a period of 6 months. The third dimension signifies the category of incentive, which is either ICT and Telecommunications e-waste or Household/Industrial e-waste or both, represented by 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The fourth dimension represents the degree of accessibility of e-waste, which is 80%. Lastly, the fifth dimension denotes the anticipated effect of the incentive on performance, which is a 50% increase in the collection. Analogously, additional stimuli may be expressed as vectors in a comparable manner, and similarities between diverse incentives may be computed utilizing a similarity metric, such as cosine similarity. This approach facilitates organizational comparison and evaluation of various incentives, enabling the selection of those that are optimal for both individual and organizational objectives.

The application with regard to mapping the vector space can be specific if all the tasks involved in the concept are associated with the collection of e-waste, we can assign numeric values to each factor and calculate the output as follows:

A = 5 (collecting e-waste may require carrying heavy items, so the size of the task is relatively large)

B = 3 (depending on the location and amount of e-waste, the time required to complete the task may vary, but it's not very time-consuming)

C = 2 (specific activities may involve sorting and separating different types of e-waste)

D = 4 (accessibility may vary depending on the location of the e-waste and the means of transportation available)

E = 4 (performance can be measured by the quantity and quality of e-waste collected)

F = 2 (incentives can be given based on the size and quantity of e-waste collected)

G = 3 (individual preferences can be taken into account to some extent, such as assigning tasks to team members based on their physical abilities and interests)

H = 4 (assigning tasks based on accessibility and quantity of e-waste can result in better incentives)

We can then use the mapping M to create effective incentive strategies. For example:

Incentives can be given based on the size (A) and quantity (E) of e-waste collected (F, A and F, E).

Task assignments can be made based on accessibility (D) and quantity (E) of e-waste (H, D and H, E).

Individual preferences (G) can be taken into account when assigning specific activities (C) related to e-waste collection.

Incentives (F) can be given based on the overall performance (E) of the team in collecting e-waste.

The output will depend on the specific values assigned to each factor and the incentive strategies implemented. However, using the concept of vector space allow for effectively mapping incentives to task performance factors, we can motivate and reward individuals or teams for collecting e-waste efficiently and effectively.

3.2. The Smart Contract E-Waste Collection Formulations

Smart contracts are self-executing computer codes that conduct specified actions when specific conditions are satisfied in the real world [

36]. Smart contracts for e-Waste collection will increase coordination among the stakeholders involve. Blockchain and smart contracts make it easier to track the origin and volume of electronic waste collected, transported, and reused throughout the process [

5]. The justification of adopting smart contract lies with its ability to set up promises/agreement that are specified in digital form, as well as the protocols that the parties and stakeholders involved in collection of e-waste will be use to fulfill these promises. Smart contracts can also automate the workflow of collection of e-waste by initiating the subsequent step when specific criteria are fulfilled.

In general, the formulation of the smart the smart contract technique lies with initialization of the following:

The incentives characterized by tasks that are linked to: size, duration, and specific activities.

The set of incentives under three distinct categories, "incentives associated with role-played", "Incentives associated with role-taking", "Incentives associated with assigned tasks".

The delineating characteristics of the incentives

The prescribed incentives,

This are initiated under 3 different initial scenarios' for

Individual (voluntarily)

Agencies (set tasks)

Manufacturers (assigned tasks)

The circumstances associated with the flow of the incentivazation technique, requires a set of incentives to be defined and, grouped by the roles played, role-taking, and assigned task as adopted from the vector space technique be presented. From Algorithm 1 below: Let S be the set of incentives offered which are grouped by role played, role-taking, and assigned task. The research represents:

S = {x | x is an incentive, grouped by role played, role-taking, or assigned task}.

This can be further establish that the subsets of S can be based on the different categories where for incentives based on role played, it is defined as a subset of S:

S1 = {x | x is an incentive based on the role played}

This expressed the incentives in S1 that was established based on agencies defined tasks which were either exceeding agencies collection of e-waste targets, or not. Similarly, for incentives based on role-taking, it is defined a subset of S where:

S2 = {x | x is an incentive based on willingness to take tasks}

This established that incentives in S2 are those associated to anyone who is willing to participate voluntary in collecting of e-waste with additional responsibilities, based on consistently demonstrating a willingness to take on new challenges. Finally, for incentives based on assigned task, it can be defined as a subset of S where:

S3 = {x | x is an incentive based on specific tasks assigned by manufacturers}

This is typically in line with Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy, where an incentive in S3 might include a reflection of a complete tasks of collection of e-waste ahead of schedule or under budget, or recognition programs for performing the tasks consistently to deliver high-quality work on assigned tasks.

3.3. The Incentivization of the Smart Contract E-Waste Collection

Incentivization refers to the act of providing a reward for a particular behavior or performing a certain task. This can also be seen as an act of imposing a penalty for the failure to exhibit that behavior or to perform that task [

37]. In certain scenarios, incentives can serve as potent instruments for incentivizing individuals or organization to undertake specific actions. On occasion, incentives can have an adverse effect and lead to a reduction in motivation rather than a boost or an avenue to address this imbalance [

38].

This study establishes that utilization of the vector space model in the computation of incentive strategies for performing e-waste collection tasks, taking into account diverse factors such as task magnitude, duration, particular actions, availability, and achievement is crucial. The justification of this lies with the correlation between the variables associated with the weights for each incentive. Through the application of weightages to the distinct factors associated with each task, a comprehensive incentive score can be computed, thereby facilitating the identification of the optimal incentive approach for each task. This methodology has the potential to assist organizations in optimizing their incentive program and enhancing the overall performance of their teams.

The scenario presented pertains to the development of an incentive plan for e-waste collection duties, taking into account diverse factors associated with task performance and individual inclinations is presented in Algorithm 1. The vector space model is utilized to represent various factors associated with task, performance and incentives and to determine the significance of each incentive factor by assessing its impact on task completion.

The three distinct tasks that exhibit varying attributes pertaining to dimensions, duration, particular undertakings, availability, and efficacy was initialized in the “Ensure” section of Algorithm 1. The determination of the overall incentive strategy for each task can be achieved by computing the weightage assigned to each incentive factor from line 25 to 35. Line 1 to 24 set out all the component associated to assigning the weight. This presents potential benefits for entities or groups seeking to encourage the collection of e-waste and enhance its efficiency by considering various task attributes and personal inclinations.

|

Algorithm 1: Incentivization |

|

Require: S = {x | x is an incentive offered: grouped by role played, role-taking, or assigned task}

|

Ensure: S1 = {x | x is an incentive based on the role played}

S2 = {x | x is an incentive based on willingness to take tasks}

S3 = {x | x is an incentive based on the completion of specific tasks or projects} |

| 1 |

IncentiveSet { |

| 2 |

S1, S2, and S3, |

| 3 |

} // Define the types of incentives |

| 4 |

IncentiveClass { |

| 5 |

size, duration, specific_activities, incentive_type |

| 6 |

} // Define the characteristics of incentives |

| 7 |

// Map the set of incentives for each initial scenario |

| 8 |

IncentiveMap { |

| 9 |

Individual: [ |

| 10 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 11 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 12 |

... |

| 12 |

], |

| 14 |

Agencies: [ |

| 15 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 16 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 17 |

... |

| 18 |

], |

| 19 |

Manufacturers: [ |

| 20 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 21 |

{size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...}, |

| 22 |

... |

| 23 |

] |

| 24 |

} |

| 25 |

// Initialize the incentives |

| 26 |

function initializeIncentives() { |

| 27 |

for each scenario in IncentiveSet: |

| 28 |

for each incentive in scenario: |

| 29 |

// Define the prescribed incentives for each incentive |

| 30 |

prescribedIncentive = ... |

| 31 |

// Delineate the characteristics of the incentive |

| 32 |

incentive = {size: ..., duration: ..., specific_activities: ..., incentive_type: ...} |

| 33 |

end for |

| 34 |

end for |

| 35 |

} |

3.4. The Computing the Incentive Score of E-Waste Collection

Algorithm 2 presents the computation of the incentive scheme for e-waste collection using the vector space model. The initiation of the calculation establishes a sets and subsets pertaining to the task associated with the collection of electronic waste, specifically those related to task and incentives weight. This is followed by the creation of a mapping mechanism to establish connections between these tasks, and the computation of an incentive score for each task, by the assigned weightage for each incentive activities presented from line 4 to line 8 of Algorithm 2. The solution has the potential to be extended to expresses incentive score for each task involves establishing the activities within the tasks and subsequently computing the total incentive score map for each task.

The values assigned to A[i], B[i], C[i], D[i], and E[i] from line 11 to 20 of the Algorithm 2 correspond to the respective activity associated with tasks, which in turn represent the weightages allocated to each activity pertaining to incentives. The determination of these weightages is based on the correlation between the activities related to incentives (F, G, H) and the activities related to task performance (A, B, C, D, E) as presented from line 21 to line 31 of Algorithm 2.

The percentage of task i that has been accomplished is determined by the values of A[i], B[i], C[i], D[i], and E[i], as represented by the task completion percentage. The incentive scores for task i have been determined by assigning weightages to each activity associated with incentives. The aggregate incentive score for a given task i is determined by adding up the incentive scores associated with each factor that pertains to incentives.

Given a scenario where the sets and subsets for e-waste collection activities are defined as: Set S = {A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H}, Subset T = {A, B, C, D, E} (activities related to tasks)

Subset I = {F, G, H} (dimension of the incentives). Create a mapping M that links the dimension of the incentives in I to the activities related to tasks in T: M = {(f, t) | f ? I, t ? T}

Assign weightage to each incentive for a certain task: A = 20%, B = 30%, C = 10%, D = 10%, E = 30%. For each task, calculate the incentive score using the mapping and weightage: For each factor f ? I: Calculate the incentive score for this factor as t * weightage, where t is the value of the corresponding factor in T. Add up the incentive score for all factors f in I to get the total incentive score for the task.

|

Algorithm 2: Computing the incentive score |

|

Require:a set for each tasks {}

|

|

Ensure:weighted average assign a score {}

|

| 1 |

Task_completion_percentage[i] = A[i]*0.2 + B[i]*0.3 + C[i]*0.1 + D[i]*0.1 + E[i]*0.3 |

| 2 |

List ←K1 ={a|O<O<n} |

| 3 |

//Calculate the incentive score for each factor related to incentives:

|

| 4 |

Incentive_score_F_A[i] = F_weightage_A * A[i] |

| 5 |

Incentive_score_F_B[i] = F_weightage_B * B[i] |

| 6 |

Incentive_score_F_C[i] = F_weightage_C * C[i] |

| 7 |

Incentive_score_F_D[i] = F_weightage_D * D[i] |

| 8 |

Incentive_score_F_E[i] = F_weightage_E * E[i] |

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

//Calculate the total incentive score for each task:

|

| 11 |

Total_incentive_score[i] = Incentive_score_F_A[i] + Incentive_score_F_B[i] + Incentive_score_F_C[i] + Incentive_score_F_D[i] + Incentive_score_F_E[i] |

| 12 |

# Define sets and subsets for e-waste collection factors |

| 13 |

S = set(['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H']) |

| 14 |

T = set(['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E']) |

| 15 |

I = set(['F', 'G', 'H']) |

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

# Create a mapping that links factors in I to factors in T |

| 18 |

M = {('F', 'A'): 0.2, ('F', 'B'): 0.3, ('F', 'C'): 0.1, ('F', 'D'): 0.1, ('F', 'E'): 0.3, |

| 19 |

('G', 'A'): None, ('G', 'B'): None, ('G', 'C'): None, ('G', 'D'): None, ('G', 'E'): None, |

| 20 |

('H', 'A'): None, ('H', 'B'): None, ('H', 'C'): None, ('H', 'D'): None, ('H', 'E'): None} |

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

# Assign weightage to each incentive factor |

| 23 |

weightage = {'A': 0.2, 'B': 0.3, 'C': 0.1, 'D': 0.1, 'E': 0.3} |

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

# Define tasks with their corresponding factor values |

| 26 |

tasks = {'Task 1': {'A': 50, 'B': 60, 'C': 20, 'D': 10, 'E': 80}, |

| 27 |

'Task 2': {'A': 10, 'B': 20, 'C': 60, 'D': 20, 'E': 70}, |

| 28 |

'Task 3': {'A': 30, 'B': 40, 'C': 10, 'D': 60, 'E': 40}} |

| 29 |

} |

| 30 |

} |

| 31 |

} |

3.5. The Incentivization of the Smart Contract E-Waste Collection

The subsequent operation, which occurs after the formulation of the Incentivization strategies, is the implementation of the incentivization. This operation is tied to the actions that take place within the blockchain smart contract. A ledger records based on smart contract for all e-waste collection system-related transactions and operations for full auditability is proposed. The smart contracts blockchain technology allows for the development of an e-waste collection system that incentivizes both consumers (users) and businesses (agency) to dispose of their electronic waste in an eco-friendly manner. This study set out the operation by first establishing that:

Z = Set of all parties involved in Smart Contract E-Waste Collection.

M = Set of parties involved in managing the smart contract.

C = Set of parties involved in the collection of e-waste.

R = Set of parties involved tracking of products in the e-waste.

With the help of these sets, we are able to establish the following roles for the various parties engaged in the Smart Contract E-Waste Collection:

According to Equation 1, the set Z, which denotes all of the participants in the smart contract e-waste collection, is equivalent to the union of the sets M, C, and R. In light of this information, it can be deduced that each and every participant in the smart contract e-waste collection is either a member of the set M, the set C, or the set R. For that reason, the operations of M = {Smart Contract Controlling unit which can be hosted by Agencies for e-waste collections or the manufacturers of the e-devices who can also be the Smart Contract Auditor}: This set represents the parties responsible for creating, developing, and auditing the smart contract. Whereas, C = {E-Waste, E-Waste Collectors}: This set represents the parties responsible for the collection of e-waste. Their operation is presented in Algorithm 2 from line 25 to 47. R = {Set of parties involved tracking of products in the e-waste.}: This set represents the parties responsible for the monitoring of e-waste.

By defining these sets and their elements, we can clearly define the roles for the parties involved in Smart Contract E-Waste Collection using mathematical set theory.

|

Algorithm 3:Smart Contract E-Waste Collection |

|

Require:Z = Set of all parties involved in Smart Contract E-Waste Collection.

|

Ensure:M = Set of parties involved in managing the smart contract.

C = Set of parties involved in the collection of e-waste .

R = Set of parties involved tracking of products in the e-waste . |

| 1 |

Initialization |

| 2 |

// operation involving the roles for the parties involved |

| 3 |

enum Role {User, Agency, Manufacturer} |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

// operation involving the structure of the data |

| 6 |

struct E_Waste { |

| 7 |

address collector; |

| 8 |

uint weight; |

| 9 |

bool isCollected; |

| 10 |

} |

| 11 |

Create |

| 12 |

// operation involving mapping to store the E-Waste data |

| 13 |

mapping(address => E_Waste[]) public eWasteCollection; |

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

// Define the function for the user to submit their e-waste for collection |

| 16 |

function submitEWaste(uint weight) public { |

| 17 |

// Add the e-waste to the user's collection list |

| 18 |

eWasteCollection[msg.sender].push(E_Waste({ |

| 19 |

collector: msg.sender, |

| 20 |

weight: weight, |

| 21 |

isCollected: false |

| 22 |

})); |

| 23 |

} |

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

// Define the function for the agency to assign collectors for e-waste collection |

| 26 |

function assignCollector(address user, uint index, address collector) public { |

| 27 |

// Ensure that only agencies can call this function |

| 28 |

require(msg.sender == Role.Agency); |

| 29 |

// Get the user's e-waste at the specified index |

| 30 |

E_Waste storage eWaste = eWasteCollection[user][index]; |

| 31 |

// Ensure that the e-waste is not already collected |

| 32 |

require(!eWaste.isCollected); |

| 33 |

// Assign the specified collector to the e-waste |

| 34 |

eWaste.collector = collector; |

| 35 |

} |

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

// Define the function for the manufacturer to collect e-waste they produced |

| 38 |

function collectManufacturerEWaste() public { |

| 39 |

// Ensure that only manufacturers can call this function |

| 40 |

require(msg.sender == Role.Manufacturer); |

| 41 |

// Collect all e-waste produced by the manufacturer |

| 42 |

for (uint i = 0; i < eWasteCollection[msg.sender].length; i++) { |

| 43 |

E_Waste storage eWaste = eWasteCollection[msg.sender][i]; |

| 44 |

if (!eWaste.isCollected) { |

| 45 |

eWaste.collector = msg.sender; |

| 46 |

eWaste.isCollected = true; |

| 47 |

} } } |

4. The Smart Contract E-waste Collection Implementation and Deployment

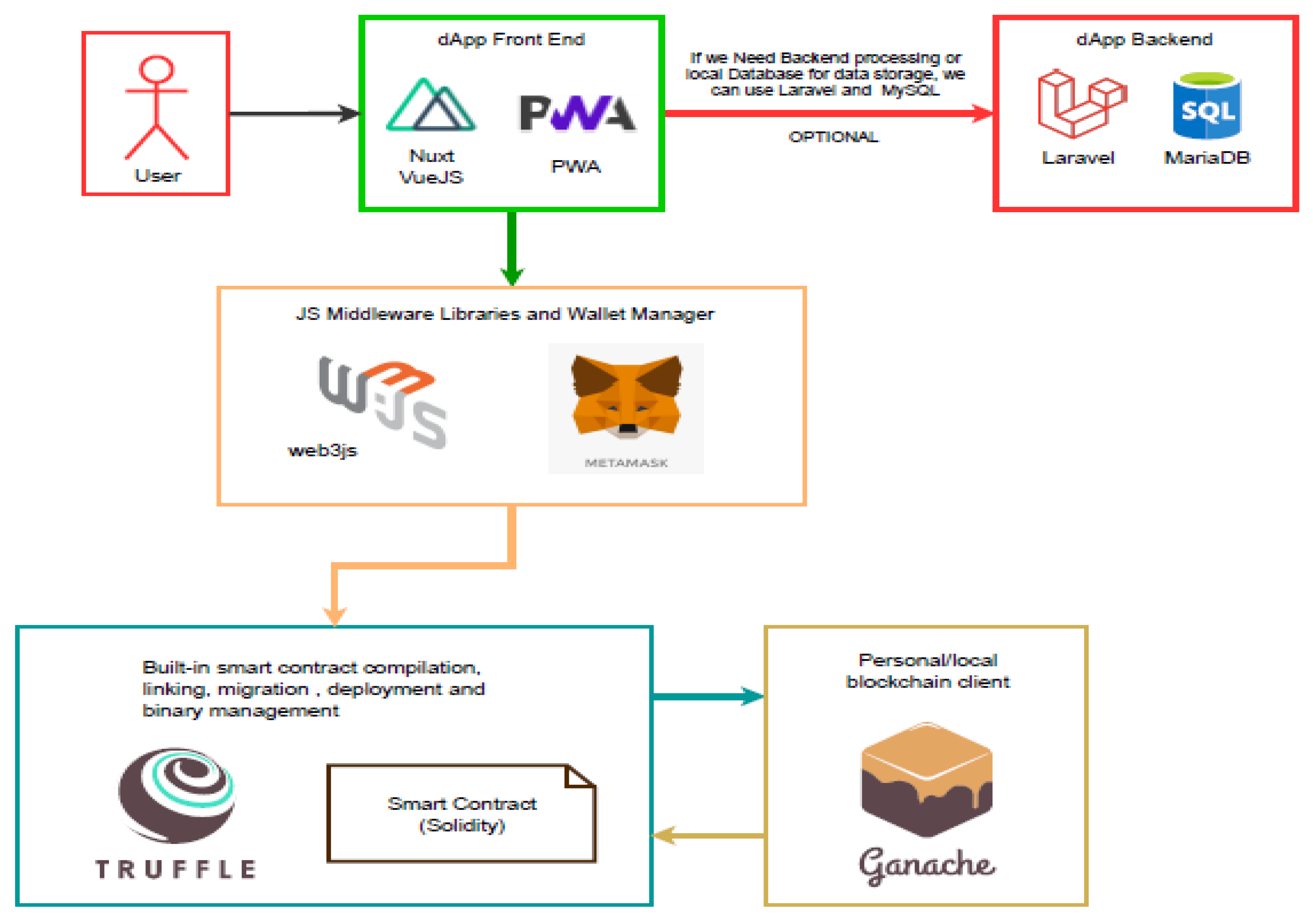

Smart Contracts are utilised for the purpose of e-waste collection through the deployment of autonomous computer programmes that execute predetermined functions in accordance with pre-established directives. For the execution, significant resources are necessary; however, the general flow process of the implementation is presented in

Figure 3. The first stage of the process depicted in the

Figure 3 consists of user being given the opportunity to register in order to supply their information, after which a block and an account will be generated for them. The user may fall under the category of Individuals who are interested in collecting e-waste, or may hold the position of Manufacturer or Supplier of the e-devices or retailers. Both of these roles are possible. Other types of applications include operating as a controlling centre for e-waste collection. Each of their responsibilities will be defined, and the addresses of their Ethereum wallets will be indexed to those roles. After that, the entirety of the processes will proceed according to the cycle shown in

Figure 3.

One of the crucial tool used in the development is Truffle. Truffle is an application framework for creating dapps on the Ethereum blockchain [

39]. ConsenSys developed it and introduced it to the public in 2015. Truffle offers a set of tools that streamline the creation of a working smart contract, from compilation to deployment to testing. The Solidity programming language is used to create smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain, and Truffle was built to be compatible with it [

40]. Smart contracts may be easily created, compiled, and deployed thanks to the integrated development environment. Additionally, automated tests for smart contracts can be written quickly and easily thanks to Truffle's integrated testing infrastructure. Truffle's many plugins and connectors make it simple to use with other tools and frameworks in the Ethereum ecosystem [

41], in addition to its basic functionality. It's compatible with a wide range of front-end frameworks including React and Angular, and widely used Ethereum client libraries like Ganache. Truffle is an excellent resource for Ethereum programmers since it provides both a user-friendly environment for coding and a set of potent tools that make it simpler to create decentralised applications (dapps) on the Ethereum network.

To those familiar with Ethereum and its associated smart contracts, a remix is a web-based IDE for developing, testing, and deploying these contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. Remix is a web-based open-source tool that offers a suite of tools to simplify the development and testing of smart contracts [

42]. Remix provides a simple environment in which to write Solidity code, the language used to generate smart contracts on the Ethereum network. In addition, it has a testing framework for automating the execution of unit tests and integration tests on smart contracts, as well as a compiler for compiling and debugging Solidity code. Remix also has a number of plugins and connections with other tools and services, such as MetaMask for handling Ethereum accounts and dealing with the blockchain, and the Swarm network for hosting and distributing decentralised applications (DApps). Remix has become an integral part of the Ethereum development ecosystem because it is a robust and adaptable tool for creating and deploying smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain.

For those working with Ethereum, Ganache provides a local blockchain environment that may be used to simulate how a network operates [

43]. Developers can test and deploy their smart contracts locally on this network without ever connecting to the main Ethereum network. In order to execute smart contracts on the Ethereum network, Ganache is constructed on top of the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). Whenever launch Ganache, it will generate an instance of a blockchain to operate locally. This blockchain has the same characteristics as the public Ethereum blockchain, but it is localised to your computer only. Creators of applications can use Ganache to set up user accounts, mine blocks, and release smart contracts. The blockchain's transaction logs, network utilisation, and contract events may all be viewed in real-time via the UI. The ability to simulate network conditions like latency and packet loss, as well as manipulating time and block numbers, are just a few of Ganache's many helpful capabilities for testing and debugging smart contracts. Overall, Ganache is a potent tool for Ethereum development, providing a secure and safe environment for developers to swiftly prototype and test new versions of smart contracts and applications.

MetaMask is a well-known cryptocurrency wallet that also functions as a browser extension [

44]. It gives users the ability to interact with decentralised applications (dapps) that run on the Ethereum blockchain. ConsenSys, a blockchain software business, was the one who initially developed it, and it was made available to the public in the year 2016. As a digital wallet, MetaMask enables users to safely store, manage, and trade Ethereum-based cryptocurrencies such as Ether (ETH) and ERC-20 tokens. Additionally, users can import and export their cryptocurrency holdings. Additionally, it enables users to engage with decentralised applications (dapps) and smart contracts by serving as a bridge between the user's browser and the Ethereum network. MetaMask is accessible as an add-on for the browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, Brave, and Microsoft Edge. Additionally, it may be downloaded as an app for mobile devices running iOS and Android. Users who have a MetaMask wallet can link it to a variety of decentralised applications (dapps) and decentralised exchanges (DEXs), allowing them to purchase, sell, and trade cryptocurrencies without having to exit their browser or app.

5. Evaluation of the Smart Contract Implementation

After the smart contract has been deployed, its Implementation consists of launching the program. The application is ready and now available.

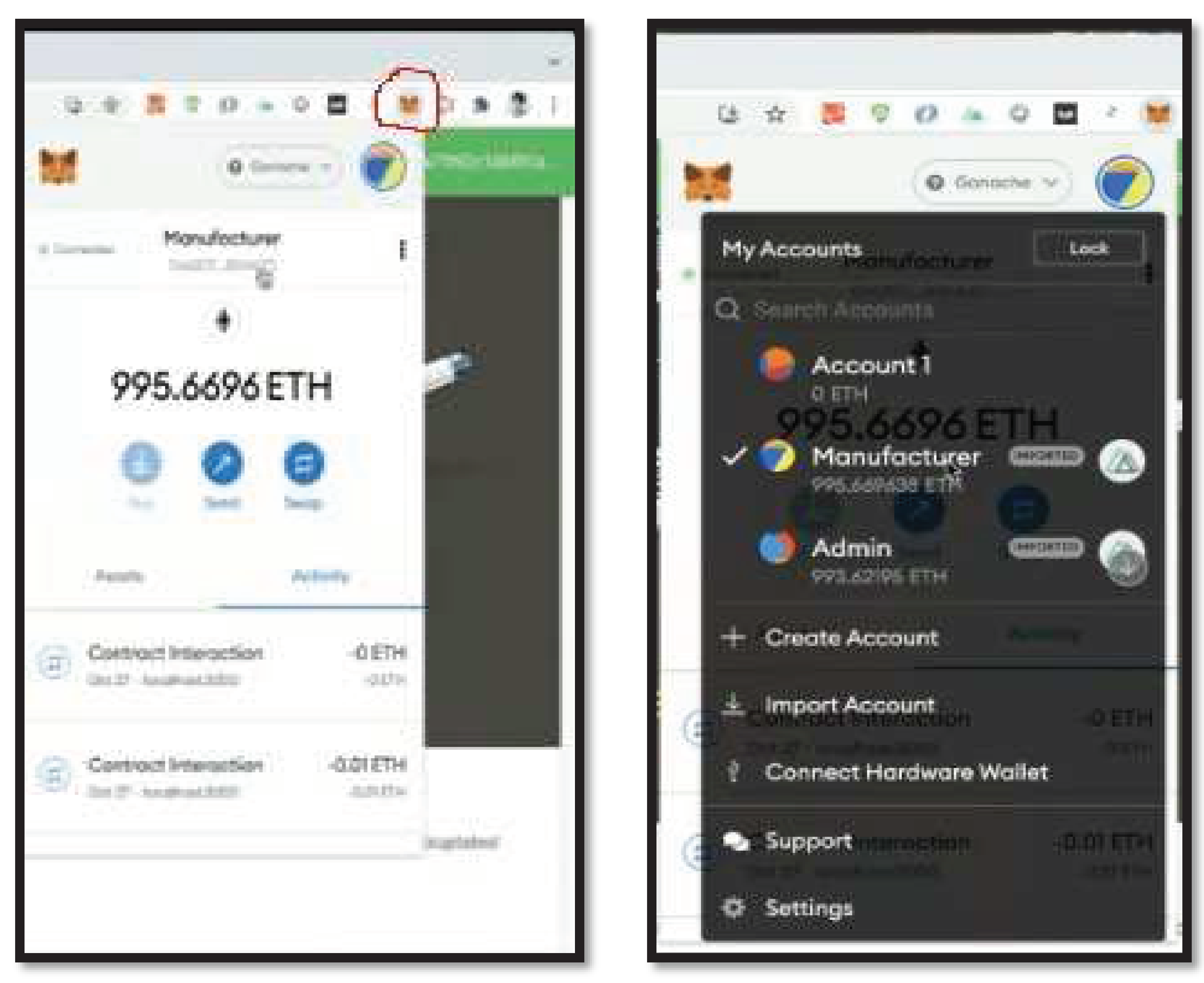

Figure 4 depicts the first lunch surface that employs both MetaMask and CORS to enable users to register for a particular account. The MetaMask wallet can connect to the Ethereum blockchain, and the CORS protocol defines the protocol used between a web browser and a server to determine if a cross-origin request is allowed. As shown in

Figure 4, the menu provides access to the numerous e-Waste programs currently in operation. The "Account Details for each account will be displayed once it has been launched, as depicted in

Figure 4's right-hand side. The smart contract can generate an entirely new account.

The data about electronic e-waste is collected from every manufacturer and then linked to the e-waste's details. The process of tracking the data that records transactions for the entire system begin, once as all e-waste details is added to the smart contract and registered. The Smart Contact platform allows its users to monitor system updates in real time. After a successful signup, a new account record will be created in the database using the user's metamask wallet address and the details supplied by the user. However, when a user tries to have a next log in to after initial creation of account, the dapp website, verify the user's identity using the wallet address obtained via MetaMask submitted during registration. Users without the Manufacturer role in the system are unable to access the "Registered e-waste" details, which is used to add new items to the block.

The imported key from the MetaMask will be used, the password will be provided, and the user will be prompted to confirm their option in the MetaMask dialogue box. Both of these actions will take place after the user has been prompted to do so. At the account belonging to the manufacturer, it will make it possible for the manufacturer to include fresh e-waste on the smart contract. After the processing has been finished, the information will be added to the manufacturer's account, and the manufacturer can then log in. Within the context of the smart contract, the electronic waste is referred to as a "Product". Products produced by the manufacturer, which are signified by the icon "my product," will display the product that has been registered with the site. Because the manufacturing company, is able to produce a diverse range of products, a list of those products may be found in their account. Through the usage of the e-waste collection system, they have the ability to make a request to trade the e-waste with another user. The wallet addresses of the user and the recipient, the time of the transfer, the product id, and the initial time of the contract are all required for this step. It is necessary for the contract to accept calls for the transfer. The user who initiates the contract is responsible for sending their Ethereum to the wallet associated with the contract. Once the product has been delivered to an e-waste facility, the initiator will receive their Ethereum back into their wallet. At the same time, it begins the steps that are designed to alert the recipient that the transfer has already begun.

When a company releases a brand-new product, it will be listed here under the "create new product" heading, indicated by the corresponding icon. When a user enters the wallet address supplied to them as the receiver of a transfer, they will be prompted to confirm whether or not they want to accept the funds. Invoking the smart contract's transfer Ownership function after gaining permission results in a new record being added to the track data structure, which documents the ownership transfer.

After the confirmation of the registration of a new manufacturer and the production of a wallet are both upcoming events. It follows with several processing flows. The crucial one lies with the chain of events that begins with a new manufacturer and continues through suppliers, retailers, and finally customers. In the transaction menu, the details of all the transaction involving the manufacturer and the supplier are presented. Accordingly, it involves "Product Transfers In", "Product Transfer Out", "Attempt Login Logs", "Your transfer Amount to E-waste" and the "My Incentive List" Finally, user will need to navigate to my product list, to choose a product, and then click on it to complete the transfer. While the address of the supplier was defined in the MetaMask, now that users want to turn over the ownership of the product to the supplier, the users need to get the address of the supplier.

Upon getting the address of the supplier, they will insert the address of the supplier, the initial locked amount, i.e that is the value of cryptocurrency locked in a smart contract and select the transaction type in this case is transfer from the manufacturer to the supplier. After that, begin the process of transferring ownership of the item from the manufacturer to the supplier, by clicking confirm to Initiate the transfer of the ownership from the Manufacturer to the Supplier then wait for the supplier to accept the transfer. The information necessary to understand the steps involved in the process of transferring ownership of an item from the manufacturer to the supplier after the transaction is been confirmed at this step.

It is necessary for the supplier to first accept the transfer before beginning the process of transferring the funds to the retailer. So at the supplier account. At the supplier login interface, since the supplier is already register, it can provide the login details. The supplier should provide the password and confirmed login into the account

The summary of the events at the Manufacturer Scenery

- i.

Display "My Product" menu and list of products

- ii.

Display "Create New Product" icon

- iii.

Display upcoming events: registration of a new manufacturer and production of a wallet

- iv.

Display the chain of events starting from a new manufacturer and ending with customers

- v.

Display the transaction menu with details of all transactions

- vi.

-

Transfer ownership from manufacturer to supplier:

- a.

Navigate to "My Product" list

- b.

Choose a product and click on it

- c.

Get the address of the supplier

- d.

Insert the supplier's address, initial locked amount, and select the transaction type as transfer from the manufacturer to the supplier

- e.

Click "Confirm" to initiate the transfer of ownership from the manufacturer to the supplier

- f.

Wait for the supplier to accept the transfer

- g.

Log the details of the transaction

The agencies that are involve in the collection of e-waste are referred to as "Suppliers" and "Retailers" in this current study. Under the guise of role-playing as described in section 3.1.2 and in

Figure 1, either "Suppliers" and "Retailers" can propose the task of collecting e-waste.

Table 1 present the summary of the event activities.

In the context of this research, "any individual" or "person" that is actively engage in collecting e-waste is refers to the customers who participate in e-waste collection. As presented in

Section 3.1.2 and

Figure 1, this falls under the category of “role taking”, that is someone that voluntarily collect e-waste. Their smart contract state is therefore summarised here, along with a summary of the events that have occurred.

Login with login details

Transfer the product to a customer or e-waste center:

- a.

-

If transferring to e-waste center:

- i.

Select "Customer to Waste Center"

- ii.

Proceed to login with admin login detail

- b.

-

If transferring to another customer:

- i.

Get the address of the customer

- ii.

Insert the customer's address

- iii.

Click "Confirm" to initiate the transfer of ownership from the customer to the other customer

- iv.

Verify the transaction details

From the smart contract's perspectives point, the Admin is the "controller" who is responsible for ensuring that all e-waste collecting activities are carried out as agreed upon. The administrator is responsible for the processing unit and the distribution of associated incentives. As such, the following is a summary of the events leading up to the present status of the Admin smart contract:

Login with admin login details

isplay the options available at the e-waste center:

- a.

-

Participants

- i.

All Participants in a Normal view

- ii.

All Participants in a Stacked view

- b.

All Registered Product in a Normal view

- c.

Detail of a Single Registered Product in a Normal view

- d.

Detail of a Single Tracked Product

- e.

Sending Reminder

- f.

Confirmed the Product that reached E-waste canter

- g.

-

Need Confirmation

- i.

Display products that need confirmation

- ii.

Confirm the product that reached the e-waste canter

- h.

Log the details of the transaction

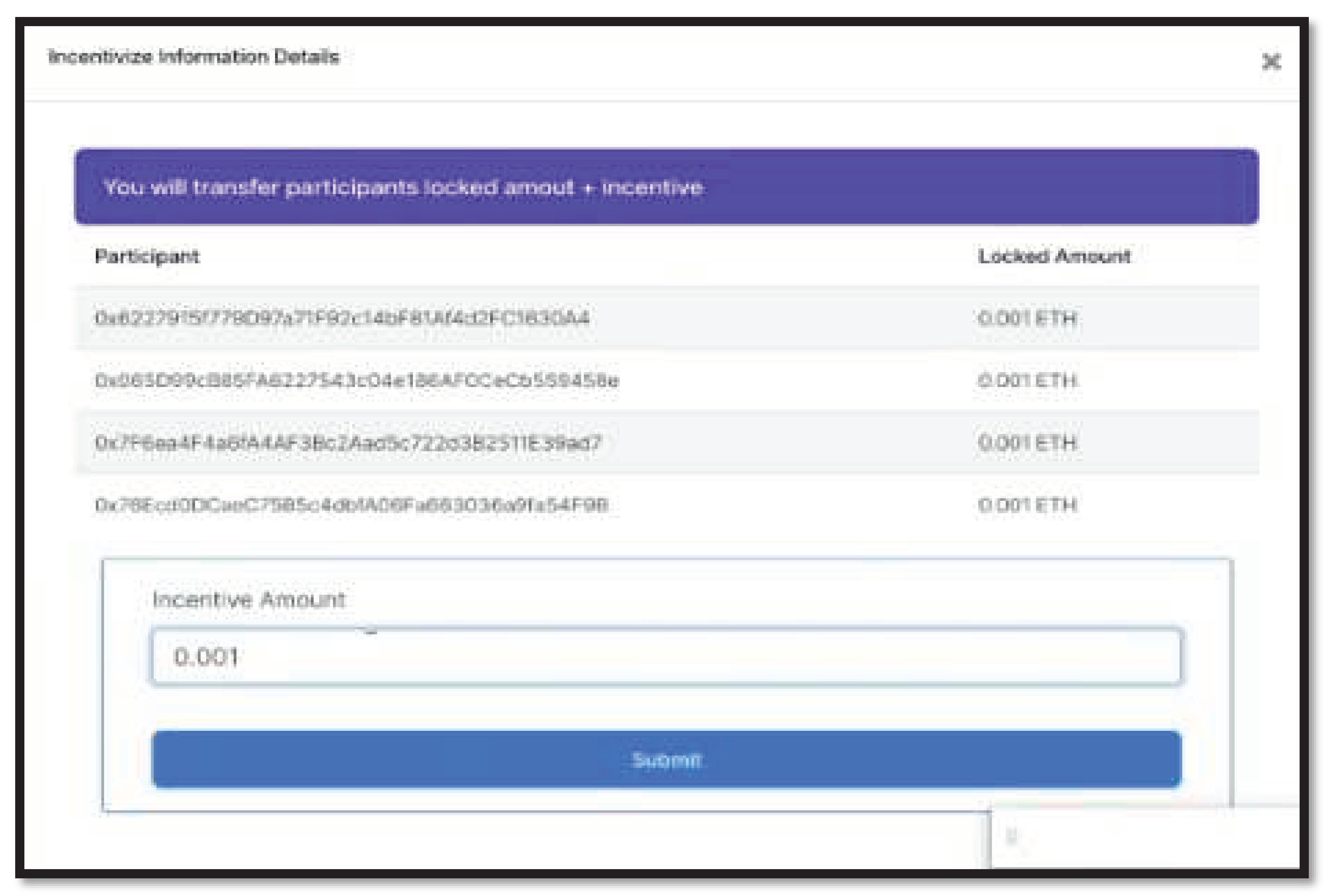

Upon arrival at the E-waste centre, a product undergoes a confirmation process, during which all transaction details are updated. Following this, the smart contract is triggered to initiate the acceptance process of the product at the E-waste centre. The next is the most important stage that involve assigning incentive associated with the tasks (see

Figure 5.

Associate incentives will be given out based on the Product that is ultimately validated at the E-waste centre (see

Figure 6). Until the item is delivered to the e-waste command centre, the incentive will not be activated. It is handed to everyone from the manufacturer to the agencies and individuals involved in the execution of the task. The incentivised function of the smart contract is invoked from within, resulting in the transfer of the appropriate amount of Ethereum to the wallets linked with the accounts of all those entities. All parties whose product transfers were hampered due to the Ethereum in the agreement are likewise released.

The smart contract can only be accessed through the unique admin account, which also served as the contract's creator. The administrator has access to all product records and can follow the product's ownership chain from its creator to the present day. The administrator can also discover the whereabouts of any out-of-date products that haven't been brought to the e-waste centre and provide that information to the current owner.

5. Principal Finding and Interpretation

In light of the growing environmental impact of Electronic waste (e-waste), there has been a surge in interest in the collection and monitoring of such waste. As a result, this study seeks to conduct an empirical investigation into the incentivization scheme for e-waste collection, utilising the Blockchain as a basis for analysis. The scheme's objective is to incentivize individuals and organisations to gather e-waste by providing tokens as a reward.

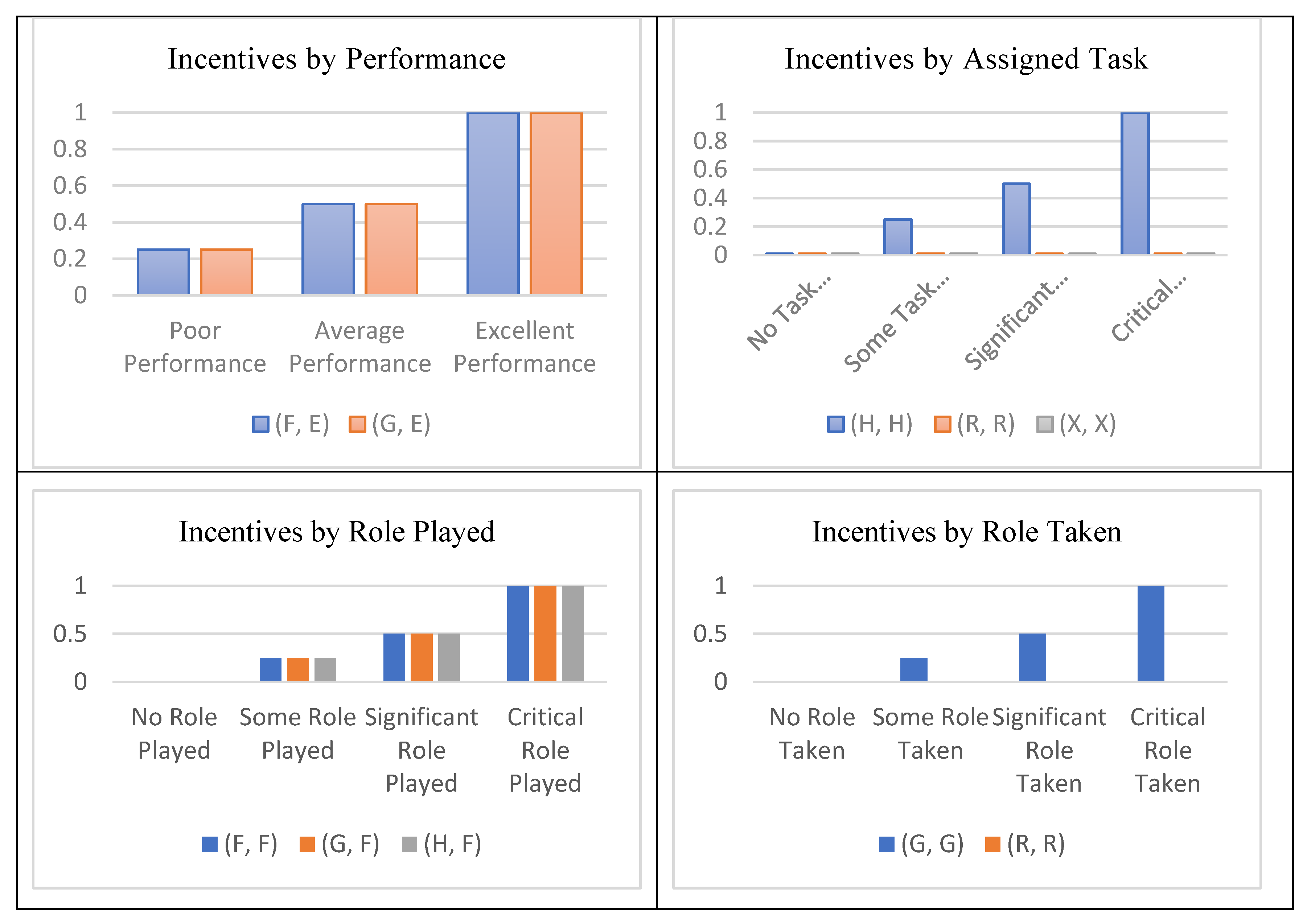

Figure 7 presents the potential results of incentives that may be taken into account for various scenarios. The allocation of numerical values in a particular scenario, wherein the factors influencing the concept to be incorporated in the smart contract, is contingent upon the specific context and objectives of the e-waste collection undertaking. The present study's implications pertain to a scenario wherein a group of ten individuals are assigned to gather electronic waste from a residential locality. The team shall receive a predetermined set of assignments to accomplish within a specified duration, and the achievement of each task shall be evaluated as a proportion. The system registration process is carried out by the e-waste smart contract controller/administrator. Subsequently, the procedure will be executed in the following manner:

A = Size of performing task: The size of each task can range from small (1%) to large (10%). We can assume an average task size of 5%, so A = 5. B = Time for performing task: Each task will have a specific time limit for completion. The time for a task can range from short (5 minutes) to long (1 hour). We can assume an average time of 30 minutes, so B = 5.

C = Specific activities of a task: The specific activities involved in each task can be categorized as easy (1%) or difficult (5%). We can assume an average difficulty of 3%, so C = 3.

D = Accessibility of the task: The accessibility of each task can range from easy (1%) to difficult (5%). We can assume an average accessibility of 2%, so D = 2. E = Performance of a task: The performance of each task can range from poor (50%) to excellent (100%). We can assume an average performance of 80%, so E = 80. F = Role played for incentives: The role played by each team member in the incentive program can be categorized as low (1%) or high (5%). We can assume an average role of 3%, so F = 3. G = Role taking for incentives: The role taken by each team member in the incentive program can range from low (1%) to high (5%). We can assume an average role of 2%, so G = 2. H = Assigning a task for incentives: The assignment of each task for better incentives can range from low (1%) to high (5%). We can assume an average assignment of 4%, so H = 4.

To create effective incentive strategies, we need to map the factors related to incentives (F, G, H) to factors related to task performance (A, B, C, D, E), based on the mapping M. This is the direct vector space implementation. Furthermore, we can use a weighted average to assign a score to each mapping, where the weight of each factor is based on its relative importance. For example, we can assign a weight of 30% to A, 20% to B, 20% to C, 15% to D, and 15% to E. Then, we can calculate the score for each mapping as follows:

The provided mappings can also offer a structure for computing the incentive rewards for task completion, taking into account various variables. The mapping (F, A) offers incentives that are contingent on the magnitude of the task, whereby a smaller task is associated with a 25% incentive, a moderate task is associated with a 50% incentive, and a substantial task is associated with a 100% incentive. The mapping (G, E) offers incentives that are contingent upon individual task performance preferences. Specifically, suboptimal performance is associated with a 25% incentive, average performance is associated with a 50% incentive and exceptional performance is associated with a 100% incentive.

The mappings have the potential to allocate tasks based on various factors such as magnitude, duration, particular undertakings, and convenience, and subsequently offer appropriate rewards. As an illustration, the allocation of a minor assignment that is readily accessible and comprises straightforward activities could potentially yield a 25% incentive, whereas a major assignment that is challenging to access and involves intricate activities could potentially yield a 100% incentive.

This follows the vector space technique proposed, the mappings offer a methodical strategy for providing incentives for tasks and considering various factors that could impact task execution and drive.

Based on Algorithm 2,

Table 2 provides a thorough list of the mapping factors, together with the values that have been allocated to them and an explanation of each mapping factor. The mapping demonstrates how each aspect pertaining to incentives (F, G, and H) can be linked to mapping factors pertaining to task performance (A, B, C, D, and E) in order to develop effective incentive systems.

Table 3 present the incentive calculation weight, and the resulting incentive value for each factor. The notation "N/A" denotes the absence of an incentive calculation formula for factors F, G, and H, as they do not exert a direct influence on task performance. The aggregate value of incentives is determined by adding up the individual incentives for each factor, resulting in a total of 105 in this instance. The tabular representation offers a lucid and succinct approach to illustrate the data and computations presented in the initial inquiry.

Similarly, assume that Assuming a task is executed with complete efficiency, whereby all facets of the task are executed flawlessly, a score of 10 will be awarded for each element. Conversely, if a task is not executed at all, a score of 0 will be granted for each element (see

Table 3). The allocation of values to the various factors in the mapping process can be achieved by utilizing the previously mentioned scale and is solely the responsibility of the e-waste smart contract controlling center.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the utilization of case-based scenarios and a weighting scale scheme to determine incentives for e-waste collection represents a potentially effective strategy for the management of e-waste. The findings of the study indicate that the incentive structure for e-waste collection is not uniform, but rather determined by a weighting scale that considers the various tasks and activities associated with the collection process. The aforementioned methodology could potentially offer a more intricate and adaptable means of motivating the gathering of electronic waste, as it has the capacity to account for the diverse levels of exertion and intricacy associated with distinct facets of the collection procedure. The method proposed for computing incentives for electronic waste collection, which involves tailoring the approach to individual cases and incorporating a system of task and activity weighting, holds significant importance for a number of reasons. The present study demonstrates that the aforementioned approach acknowledges the intricate and fluctuating nature of e-waste collection endeavors. The process of collecting electronic waste encompasses a variety of undertakings and operations, including but not limited to categorization, conveyance, and elimination, each of which presents distinct obstacles and prerequisites. The utilization of a case-based scenario methodology allows for the customization of incentive calculations to suit the particular conditions of the collection endeavor. This ensures that the incentives are equitable and precisely correspond to the exertion and resources demanded. Moreover, the utilization of a weighting scale system facilitates a more intricate computation of motivators. The utilization of fixed value incentives may result in an inaccurate representation of the worth of various tasks and activities, potentially resulting in unjust remuneration for individuals engaged in e-waste collection. Through the allocation of a weight or value to individual tasks, the calculation of incentives can be customized to the precise demands of each task, thereby guaranteeing equitable remuneration for those engaged in the collection of electronic waste. The present study applies this methodology in practical contexts, utilizing blockhain smart contracts and creating an app to establish unambiguous protocols and processes for distributing rewards according to case-specific circumstances and a system of weighted scales. The effective implementation of the new approach towards e-waste collection will necessitate adequate training and support for the individuals involved, to ensure their comprehension and proficiency in its application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The software program.

Author Contributions

Problem formulation, Adamu Abubakar; Literature review, Adamu Abubakar; soft-ware, Ala Abdulsalam Alarood; validation, Ala Abdulsalam Alarood Adamu Abubakar Abdulrahman Alzahrani; formal analysis, Faisal S. Alsubaei and Abdulrahman Alzahrani; investigation, Abdulrahman Alzahrani and Adamu Abubakar; resources, Ala Abdulsalam Alarood and Abdulrahman Alzahrani , and Faisal S. Alsubaei; data curation, Adamu Abubakar; writing—original draft preparation, Adamu Abubakar; writing—review and editing, Adamu Abubakar; visualization, Adamu Abubakar; supervision,Adamu Abubakar; project administration, Ala Abdulsalam Alarood and Abdulrahman Alzahrani , Faisal S. Alsubaei; funding acquisition, Adamu Abubakar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

A software application is currently accessible, and the underlying source code utilized in its creation is also available and can be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Liu K, Tan Q, Yu J, Wang M. A global perspective on e-waste recycling. Circular Economy. 2023, 2(1), 1-28:100028. [CrossRef]

- Borthakur A, Govind M. Emerging trends in consumers’ E-waste disposal behaviour and awareness: A worldwide overview with special focus on India. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2017 1;117:102-13. [CrossRef]

- Murthy V, Ramakrishna S. A review on global e-waste management: urban mining towards a sustainable future and circular economy. Sustainability. 2022 7;14(2):647. [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin M, Uddin MN, Chowdhury JI, Ahmed SF, Uddin MN, Mofijur M, Uddin MA. A review of the recent development, challenges, and opportunities of electronic waste (e-waste). International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2023, 20(4):4513-20.

- Dua A, Dutta A, Zaman N, Kumar N. Blockchain-based E-waste management in 5G smart communities. In IEEE INFOCOM 2020-IEEE conference on computer communications workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS) 2020 Jul 6 (pp. 195-200).

- Wei L, Wu J, Long C. A blockchain-based hybrid incentive model for crowdsensing. Electronics. 2020 24;9(2):215. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Li M, He Y, Li H, Xiao K, Wang C. A blockchain based privacy-preserving incentive mechanism in crowdsensing applications. IEEE Access. 2018 5;6:17545-56. [CrossRef]

- Gupta N, Bedi P. E-waste management using blockchain based smart contracts. In2018 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI) 2018 Sep 19 (pp. 915-921).

- Poongodi M, Hamdi M, Vijayakumar V, Rawal BS, Maode M. An effective electronic waste management solution based on blockchain smart contract in 5G communities. In2020 IEEE 3rd 5G World Forum (5GWF) 2020 Sep 10 (pp. 1-6).

- Leal Filho W, Saari U, Fedoruk M, Iital A, Moora H, Klöga M, Voronova V. An overview of the problems posed by plastic products and the role of extended producer responsibility in Europe. Journal of cleaner production. 2019 20; 214:550-8. [CrossRef]

- Shooshtarian S, Maqsood T, Wong PS, Khalfan M, Yang RJ. Extended producer responsibility in the Australian construction industry. Sustainability. 2021 11;13(2):620. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Qin Y, Zhu D, Zhang S. Upgrading waste electrical and electronic equipment recycling through extended producer responsibility: A case study. Circular Economy. 2023 1;2(1):100025. [CrossRef]

- Joltreau, E. Extended producer responsibility, packaging waste reduction and eco-design. Environmental and Resource Economics. 2022; 83(3):527-78. [CrossRef]

- Faibil D, Asante R, Agyemang M, Addaney M, Baah C. Extended producer responsibility in developing economies: Assessment of promoting factors through retail electronic firms for sustainable e-waste management. Waste Management & Research. 2023, 1:0734242X221105433. [CrossRef]

- Compagnoni, M. Is Extended Producer Responsibility living up to expectations? A systematic literature review focusing on electronic waste. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022 11:133101. [CrossRef]

- McGrenary, S. The E-waste problem and how Blockchain can solve it. FinTech Scotland, November. 2018 Nov;13.